Jelling Style on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Viking art, also known commonly as Norse art, is a term widely accepted for the art of Scandinavian Norsemen and Viking settlements further afield—particularly in the British Isles and Iceland—during the Viking Age of the 8th-11th centuries. Viking art has many design elements in common with

The Vikings' regional origins lay in Scandinavia, the northernmost peninsula of continental Europe, while the term 'Viking' likely derived from their own term for coastal raiding—the activity by which many neighboring cultures became acquainted with the inhabitants of the region.

Viking raiders attacked wealthy targets on the north-western coasts of Europe from the late 8th until the mid-11th century CE. Pre-Christian traders and sea raiders, the Vikings first enter recorded history with their attack on the Christian monastic community on

The Vikings' regional origins lay in Scandinavia, the northernmost peninsula of continental Europe, while the term 'Viking' likely derived from their own term for coastal raiding—the activity by which many neighboring cultures became acquainted with the inhabitants of the region.

Viking raiders attacked wealthy targets on the north-western coasts of Europe from the late 8th until the mid-11th century CE. Pre-Christian traders and sea raiders, the Vikings first enter recorded history with their attack on the Christian monastic community on

Wood was undoubtedly the primary material of choice for Viking artists, being relatively easy to carve, inexpensive, and abundant in northern Europe. The importance of wood as an artistic medium is underscored by chance survivals of wood artistry at the very beginning and end of the Viking period, namely, the Oseberg ship-burial carvings of the early 9th century and the carved decoration of the

Wood was undoubtedly the primary material of choice for Viking artists, being relatively easy to carve, inexpensive, and abundant in northern Europe. The importance of wood as an artistic medium is underscored by chance survivals of wood artistry at the very beginning and end of the Viking period, namely, the Oseberg ship-burial carvings of the early 9th century and the carved decoration of the

Beyond the discontinuous artifactual records of wood and stone, the reconstructed history of Viking art to date relies most on the study of decoration of ornamental metalwork from a great variety of sources. Several types of archaeological context have succeeded in preserving metal objects for present study, while the durability of

Beyond the discontinuous artifactual records of wood and stone, the reconstructed history of Viking art to date relies most on the study of decoration of ornamental metalwork from a great variety of sources. Several types of archaeological context have succeeded in preserving metal objects for present study, while the durability of

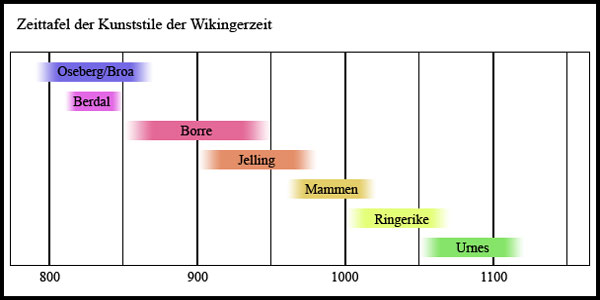

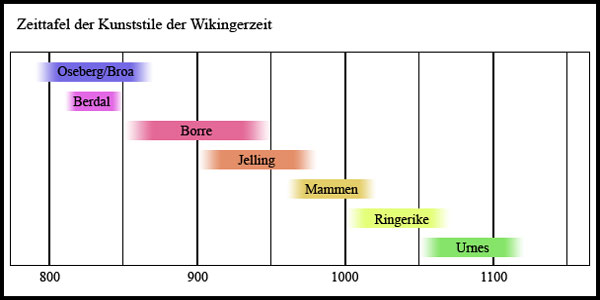

The art of the Viking Age is organized into a loose sequence of stylistic phases which, despite the significant overlap in style and chronology, may be defined and distinguished on account both of formal design elements and of recurring compositions and motifs:

* Oseberg Style

* Borre Style

* Jellinge Style

* Mammen Style

* Ringerike Style

* Urnes Style

Unsurprisingly, these stylistic phases appear in their purest form in Scandinavia itself; elsewhere in the Viking world, notable admixtures from external cultures and influences frequently appear. In the British Isles, for example, art historians identify distinct, 'Insular' versions of Scandinavian motifs, often directly alongside 'pure' Viking decoration.

The art of the Viking Age is organized into a loose sequence of stylistic phases which, despite the significant overlap in style and chronology, may be defined and distinguished on account both of formal design elements and of recurring compositions and motifs:

* Oseberg Style

* Borre Style

* Jellinge Style

* Mammen Style

* Ringerike Style

* Urnes Style

Unsurprisingly, these stylistic phases appear in their purest form in Scandinavia itself; elsewhere in the Viking world, notable admixtures from external cultures and influences frequently appear. In the British Isles, for example, art historians identify distinct, 'Insular' versions of Scandinavian motifs, often directly alongside 'pure' Viking decoration.

The Oseberg Style characterises the initial phase in what has been considered Viking art. The Oseberg Style takes its name from the Oseberg Ship grave, a well-preserved and highly decorated longship discovered in a large burial mound at the Oseberg farm near Tønsberg in Vestfold, Norway, which also contained a number of other richly decorated wooden objects.

A characteristic motif of the Oseberg Style is the so-called gripping beast. This motif is what clearly distinguishes the early Viking art from the styles that preceded it. The chief features of the gripping beast are the paws that grip the borders around it, neighbouring beasts or parts of its own body.

Currently located at the Viking Ship Museum, Bygdøy, and over 70 feet long, the Oseberg Ship held the remains of two women and many precious objects that were probably removed by robbers early before it was found. The Oseberg ship itself is decorated with a more traditional style of animal interlace that does not feature the gripping beast motif. However, five carved wooden animal-head posts were found in the ship, and the one known as the ''Carolingian animal-head post'' is decorated with gripping beasts, as are other grave goods from the ship. The Carolingian head represents a snarling beast, possibly a wolf, with surface ornamentation in the form of interwoven animals that twist and turn as they are gripping and snapping.

The Oseberg style is also characterized by traditions from the Vendel era, and it is nowadays not always accepted as an independent style.The article ''djurornamentik'' in '' Nationalencyklopedin'' (1991).

The Oseberg Style characterises the initial phase in what has been considered Viking art. The Oseberg Style takes its name from the Oseberg Ship grave, a well-preserved and highly decorated longship discovered in a large burial mound at the Oseberg farm near Tønsberg in Vestfold, Norway, which also contained a number of other richly decorated wooden objects.

A characteristic motif of the Oseberg Style is the so-called gripping beast. This motif is what clearly distinguishes the early Viking art from the styles that preceded it. The chief features of the gripping beast are the paws that grip the borders around it, neighbouring beasts or parts of its own body.

Currently located at the Viking Ship Museum, Bygdøy, and over 70 feet long, the Oseberg Ship held the remains of two women and many precious objects that were probably removed by robbers early before it was found. The Oseberg ship itself is decorated with a more traditional style of animal interlace that does not feature the gripping beast motif. However, five carved wooden animal-head posts were found in the ship, and the one known as the ''Carolingian animal-head post'' is decorated with gripping beasts, as are other grave goods from the ship. The Carolingian head represents a snarling beast, possibly a wolf, with surface ornamentation in the form of interwoven animals that twist and turn as they are gripping and snapping.

The Oseberg style is also characterized by traditions from the Vendel era, and it is nowadays not always accepted as an independent style.The article ''djurornamentik'' in '' Nationalencyklopedin'' (1991).

Image:Carolingian animal-head post.jpg, Detail of the Carolingian animal-head post from the Oseberg ship burial, showing the gripping beast motif.

Image:Osebergskipet-Detail.jpg, Detail from the Oseberg ship

Image:Oseberg bow detail.JPG, Oseberg bow detail

The Broa style, named after a bridle-mount found at Broa, Halla parish, Gotland, is sometimes included with the Oseberg style, and sometimes held as its own.

The Broa style, named after a bridle-mount found at Broa, Halla parish, Gotland, is sometimes included with the Oseberg style, and sometimes held as its own.

Image:Broa bridle (HST DIG56307).jpg, Photograph of the Broa bridle taken by Ola Myrin for the Swedish Historiska museet exhibit "The Viking World".

Image:Broa_bridle_(HST_DIG56310).jpg, Front of the bridle.

Image:Broa bridle (HST DIG56309).jpg, Right side relative to the horse.

Image:Broa bridle (HST DIG56308).jpg, Left side relative to the horse.

Image:Broa bridle (HST DIG49898).jpg, Detail of left side.

Image:Broa bridle (HST DIG56311).jpg, Detail of mounts hanging from the bit.

The Borre Style embraces a range of geometric interlace / knot patterns and zoomorphic (single animal) motifs, first recognised in a group of gilt-bronze

The Borre Style embraces a range of geometric interlace / knot patterns and zoomorphic (single animal) motifs, first recognised in a group of gilt-bronze

The Jellinge Style is a phase of Scandinavian

The Jellinge Style is a phase of Scandinavian

Image:Skaill-jelling.gif

Image:Varby-jelling.gif

Image:Decoratiepatroon van reliekenhoorn (Scandinavië, 10e eeuw), Schatkamer OLV-basiliek, Maastricht.JPG

The Mammen Style takes its name from its type object, an axe recovered from a wealthy male burial marked a mound (Bjerringhø) at Mammen, in Jutland, Denmark (on the basis of dendrochronology, the wood used in construction of the grave chamber was felled in winter 970–971). Richly decorated on both sides with inlaid silver designs, the iron axe was probably a ceremonial parade weapon that was the property of a man of princely status, his burial clothes bearing elaborate embroidery and trimmed with silk and fur.

The Mammen Style takes its name from its type object, an axe recovered from a wealthy male burial marked a mound (Bjerringhø) at Mammen, in Jutland, Denmark (on the basis of dendrochronology, the wood used in construction of the grave chamber was felled in winter 970–971). Richly decorated on both sides with inlaid silver designs, the iron axe was probably a ceremonial parade weapon that was the property of a man of princely status, his burial clothes bearing elaborate embroidery and trimmed with silk and fur.

On one face, the Mammen axe features a large bird with pelleted body, crest, circular eye, and upright head and beak with lappet. A large shell-spiral marks the bird's hip, from which point its thinly elongated wings emerge: the right wing interlaces with the bird's neck, while the left wing interlaces with its body and tail. The outer wing edge displays a semi-circular nick typical of Mammen Style design. The tail is rendered as a triple tendril, the particular treatment of which on the Mammen axe – with open, hook-like ends – forming a characteristic of the Mammen Style as a whole. Complicating the design is the bird's head-lappet, interlacing twice with neck and right wing, whilst also sprouting tendrils along the blade edge. At the top, near the haft, the Mammen axe features an interlaced knot on one side, a triangular human mask (with large nose, moustache and spiral beard) on the other; the latter would prove a favoured Mammen Style motif carried over from earlier styles.

On the other side, the Mammen axe bears a spreading foliate (leaf) design, emanating from spirals at the base with thin, 'pelleted' tendrils spreading and intertwining across the axe head towards the haft.

On one face, the Mammen axe features a large bird with pelleted body, crest, circular eye, and upright head and beak with lappet. A large shell-spiral marks the bird's hip, from which point its thinly elongated wings emerge: the right wing interlaces with the bird's neck, while the left wing interlaces with its body and tail. The outer wing edge displays a semi-circular nick typical of Mammen Style design. The tail is rendered as a triple tendril, the particular treatment of which on the Mammen axe – with open, hook-like ends – forming a characteristic of the Mammen Style as a whole. Complicating the design is the bird's head-lappet, interlacing twice with neck and right wing, whilst also sprouting tendrils along the blade edge. At the top, near the haft, the Mammen axe features an interlaced knot on one side, a triangular human mask (with large nose, moustache and spiral beard) on the other; the latter would prove a favoured Mammen Style motif carried over from earlier styles.

On the other side, the Mammen axe bears a spreading foliate (leaf) design, emanating from spirals at the base with thin, 'pelleted' tendrils spreading and intertwining across the axe head towards the haft.

The type object most commonly used to define Ringerike Style is a high

The type object most commonly used to define Ringerike Style is a high  With regard to metalwork, Ringerike Style is best seen in two copper-gilt weather-vanes, from Källunge, Gotland and from Söderala, Hälsingland (the Söderala vane), both in Sweden. The former displays one face two axially-constructed loops in the form of snakes, which in turn sprout symmetrically-placed tendrils. The snake heads, as well as the animal and snake on the reverse, find more florid treatment than on the Vang Stone: all have lip lappets, the snakes bear pigtails, while all animals have a pear-shaped eye with the point directed towards the snout – a diagnostic feature of Ringerike Style.

The Ringerike Style evolved out of the earlier Mammen Style. It received its name from a group of runestones with animal and plant motifs in the Ringerike district north of Oslo. The most common motifs are lions, birds, band-shaped animals and spirals.Moss (2014), p. 44 Some elements appear for the first time in Scandinavian art, such as different types of crosses, palmettes and pretzel-shaped nooses that tie together two motifs. Most of the motifs have counterparts in

With regard to metalwork, Ringerike Style is best seen in two copper-gilt weather-vanes, from Källunge, Gotland and from Söderala, Hälsingland (the Söderala vane), both in Sweden. The former displays one face two axially-constructed loops in the form of snakes, which in turn sprout symmetrically-placed tendrils. The snake heads, as well as the animal and snake on the reverse, find more florid treatment than on the Vang Stone: all have lip lappets, the snakes bear pigtails, while all animals have a pear-shaped eye with the point directed towards the snout – a diagnostic feature of Ringerike Style.

The Ringerike Style evolved out of the earlier Mammen Style. It received its name from a group of runestones with animal and plant motifs in the Ringerike district north of Oslo. The most common motifs are lions, birds, band-shaped animals and spirals.Moss (2014), p. 44 Some elements appear for the first time in Scandinavian art, such as different types of crosses, palmettes and pretzel-shaped nooses that tie together two motifs. Most of the motifs have counterparts in

File:Ringerike St Paul runetone.jpg, English Runic Inscription 2

Image:Heggen.gif, A weathervane

Image:Ög 111.jpg, The runestone Ög 111 with a cross in Ringerike style

Image:U 1016, Fjuckby.jpg, The runestone U 1016 at Fjuckby

File:Sö280 Strängnäs.jpg, Runestone Sö 280 at Strängnäs Cathedral

File:U 1146, Gillberga.JPG, Runestone U 1146 in Gillberga, Uppland

* Roesdahl, E. and Wilson, D.M. (eds) (1992). ''From Viking to Crusader: Scandinavia and Europe 800–1200'', Copenhagen and New York, 1992. xhibition catalogue * Williams, G., Pentz, P. and Wemhoff, M. (eds), ''Vikings: Life and Legend'', British Museum Press: London, 2014. xhibition catalogue * Wilson, D.M. & Klindt-Jensen, O. (1980). ''Viking Art'', second edition, George Allen and Unwin, 1980.

Academic.edu

* Krafft, S. (1956). ''Pictorial Weavings from the Viking Age'', Oslo: Dreyer, 1956. * Lang, J.T. (1984). "The hogback: a Viking colonial monument", ''Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History'' 3 (1984), pp. 85–176. * Lang, J.T. (1988). ''Viking Age Decorated Wood: A Study of its Ornament and Style'', Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1988. * Moss, Rachel. ''Medieval c. 400—c. 1600: Art and Architecture of Ireland''. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014. * Müller-Wille, M. and Larsson, L.O. (eds) (2001). ''Tiere – Menschen – Götter: Wikingerzeitliche Kunststile und ihre Neuzeitliche Rezeption'', Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Gottingen, 2001. * Myhre, B. (1992). "The Royal Cemetery at Borre, Vestfold: A Norwegian Centre in a European Periphery", in Carter, M. (ed.), ''The Age of Sutton Hoo. The Seventh Century in North-West Europe'', Woodbridge: Boydell, 1992. * Owen, O. (2001). "The strange beast that is the English Urnes Style", in Graham-Campbell, J. ''et al.'' (eds), ''Vikings and the Danelaw – Selected Papers from the Proceedings of the Thirteenth Viking Congress'', Oxford: Oxbow, 2001, pp. 203–22. * Paterson, C. (2002). "From Pendants to Brooches – The Exchange of Borre and Jelling Style Motifs across the North Sea", ''Hikuin'' 29 (2002), pp. 267–76. * Reynolds, A. and Webster, L. (eds) (2013), ''Early Medieval Art and Archaeology in the Northern World—Studies in Honour of James Graham-Campbell'', Brill: Leiden and Boston, 2013. * Richards, J.D. and Naylor, J. (2010). "The metal detector and the Viking Age in England", in Sheehan, J. and Corráin, D. Ó. (eds), ''The Viking Age. Ireland and the West. Proceedings of the Fifteenth Viking Congress'', Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2010, pp. 338–52. * Roesdahl, E. (1994). "Dendrochronology and Viking Studies in Denmark, with a Note on the Beginning of the Viking Age", in Abrosiani, B. and Clarke, H. (eds), ''Developments around the Baltic and the North Sea in the Viking Age'', Stockholm: Birka Project for Riksantikvarieämbetet and Statens Historiska Museer, 1994, pp. 106–16. * Roesdahl, E. (2010a). "Viking Art in European Churches (Cammin – Bamberg – Prague – León)", in Sheehan and Ó Corráin (eds) (2010), pp. 149–64. * Roesdahl, E. (2010b). "From Scandinavia to Spain: a Viking Age Reliquary in León and its Significance", in Sheehan, J. and Corráin, D. Ó. (eds), ''The Viking Age. Ireland and the West. Proceedings of the Fifteenth Viking Congress'', Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2010, pp. 353–60. * Salin, Bernhard (1904). ''Die altgermanische Thieronamentik'', Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand, 1904. * Sheehan, J. and Ó Corráin, D. (eds) (2010). ''The Viking Age: Ireland and the West. Proceedings of the XVth Viking Congress, Cork, 2005.'', Dublin and Portland: Four Courts Press, 2010. * Shetelig, H. (1920). ''Osebergfundet'', Volume III, Kristiania, 1920. * Wilson, D.M. (2001). "The Earliest Animal Styles of the Viking Age", in Müller-Wille and Larsson (eds) (2001), pp. 131–56. * Wilson, D.M. (2008a). "The Development of Viking Art", in Brink with Price (2008), pp. 323–38. * Wilson, D.M. (2008b). ''The Vikings in the Isle of Man'', Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2008.

British Museum: Explore / World Cultures: Vikings

* Sorabella, Jean

in ''Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History'', New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. Updated October 2002. *

Age of spirituality : late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century

' from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Examples of the Broa and Oseberg Style

Borrehaugene

* Jane Kershaw

Viking-Age Scandinavian art styles and their appearance in the British Isles – Part 1: Early Viking-Age art styles

– The Finds Research Group AD 700–1700, Datasheet 42, 2010. (Academia.edu registration required). * Jane Kershaw

Viking-Age Scandinavian art styles and their appearance in the British Isles Part 2: Late Viking-Age art styles

– The Finds Research Group AD 700–1700, Datasheet 43, 2011. (Academia.edu registration required). {{DEFAULTSORT:Viking Age art

Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

* Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Fo ...

, Germanic, the later Romanesque and Eastern European art, sharing many influences with each of these traditions.

Generally speaking, the current knowledge of Viking art relies heavily upon more durable objects of metal and stone; wood, bone, ivory and textiles

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not the ...

are more rarely preserved. The artistic record, therefore, as it has survived to the present day, remains significantly incomplete. Ongoing archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

excavation

Excavation may refer to:

* Excavation (archaeology)

* Excavation (medicine)

* ''Excavation'' (The Haxan Cloak album), 2013

* ''Excavation'' (Ben Monder album), 2000

* ''Excavation'' (novel), a 2000 novel by James Rollins

* '' Excavation: A Memo ...

and opportunistic finds, of course, may improve this situation in the future, as indeed they have in the recent past.

Viking art is usually divided into a sequence of roughly chronological styles, although outside Scandinavia itself local influences are often strong, and the development of styles can be less clear.

Historical context

The Vikings' regional origins lay in Scandinavia, the northernmost peninsula of continental Europe, while the term 'Viking' likely derived from their own term for coastal raiding—the activity by which many neighboring cultures became acquainted with the inhabitants of the region.

Viking raiders attacked wealthy targets on the north-western coasts of Europe from the late 8th until the mid-11th century CE. Pre-Christian traders and sea raiders, the Vikings first enter recorded history with their attack on the Christian monastic community on

The Vikings' regional origins lay in Scandinavia, the northernmost peninsula of continental Europe, while the term 'Viking' likely derived from their own term for coastal raiding—the activity by which many neighboring cultures became acquainted with the inhabitants of the region.

Viking raiders attacked wealthy targets on the north-western coasts of Europe from the late 8th until the mid-11th century CE. Pre-Christian traders and sea raiders, the Vikings first enter recorded history with their attack on the Christian monastic community on Lindisfarne

Lindisfarne, also called Holy Island, is a tidal island off the northeast coast of England, which constitutes the civil parish of Holy Island in Northumberland. Holy Island has a recorded history from the 6th century AD; it was an important ...

Island in 793.

The Vikings initially employed their longships to invade and attack European coasts, harbors and river settlements on a seasonal basis. Subsequently, Viking activities diversified to include trading voyages to the east, west, and south of their Scandinavian homelands, with repeated and regular voyages following river systems east into Russia and the Black and Caspian Sea regions, and west to the coastlines of the British Isles, Iceland and Greenland. Evidence exists for Vikings reaching Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

well before the later voyages of Christopher Columbus came to the New World.

Trading and merchant activities were accompanied by settlement and colonization in many of these territories.Kleiner, Gardner's Art Through The Ages: The Western Perspective, Volume I, 288.

By material

Wood and organic materials

Wood was undoubtedly the primary material of choice for Viking artists, being relatively easy to carve, inexpensive, and abundant in northern Europe. The importance of wood as an artistic medium is underscored by chance survivals of wood artistry at the very beginning and end of the Viking period, namely, the Oseberg ship-burial carvings of the early 9th century and the carved decoration of the

Wood was undoubtedly the primary material of choice for Viking artists, being relatively easy to carve, inexpensive, and abundant in northern Europe. The importance of wood as an artistic medium is underscored by chance survivals of wood artistry at the very beginning and end of the Viking period, namely, the Oseberg ship-burial carvings of the early 9th century and the carved decoration of the Urnes Stave Church

Urnes Stave Church ( no, Urnes stavkyrkje) is a 12th-century stave church at Ornes, along the Lustrafjorden in the municipality of Luster in Vestland county, Norway.

The church sits on the eastern side of the fjord, directly across the fjord f ...

from the 12th century. As summarised by James Graham-Campbell: "These remarkable survivals allow us to form at least an impression of what we are missing from original corpus of Viking art, although wooden fragments and small-scale carvings in other materials (such as antler, amber, and walrus ivory) provide further hints. The same is inevitably true of the textile arts, although weaving and embroidery were clearly well-developed crafts."

Stone

With the exception of the Gotlandic picture stones prevalent in Sweden early in the Viking period, stone carving was apparently not practiced elsewhere in Scandinavia until the mid-10th century and the creation of the royal monuments at Jelling in Denmark. Subsequently, and likely influenced by the spread of Christianity, the use of carved stone for permanent memorials became more prevalent.Metal

Beyond the discontinuous artifactual records of wood and stone, the reconstructed history of Viking art to date relies most on the study of decoration of ornamental metalwork from a great variety of sources. Several types of archaeological context have succeeded in preserving metal objects for present study, while the durability of

Beyond the discontinuous artifactual records of wood and stone, the reconstructed history of Viking art to date relies most on the study of decoration of ornamental metalwork from a great variety of sources. Several types of archaeological context have succeeded in preserving metal objects for present study, while the durability of precious metal

Precious metals are rare, naturally occurring metallic chemical elements of high economic value.

Chemically, the precious metals tend to be less reactive than most elements (see noble metal). They are usually ductile and have a high lustre. ...

s, in particular, has preserved much artistic expression and endeavor.

Jewelry was worn by both men and women, though of different types. Married women fastened their overdresses near the shoulder with matching pairs of large brooches. Modern scholars often call them "tortoise brooches" because of their domed shape. The shapes and styles of women's paired brooches varied regionally, but many used openwork. Women often strung metal chains or strings of beads between the brooches or suspended ornaments from the bottom of the brooches. Men wore rings on their fingers, arms and necks, and held their cloaks closed with penannular brooches, often with extravagantly long pins. Their weapons were often richly decorated on areas such as sword hilt

The hilt (rarely called a haft or shaft) of a knife, dagger, sword, or bayonet is its handle, consisting of a guard, grip and pommel. The guard may contain a crossguard or quillons. A tassel or sword knot may be attached to the guard or pommel. ...

s. The Vikings mostly used silver or bronze jewelry, the latter sometimes gilded

Gilding is a decorative technique for applying a very thin coating of gold over solid surfaces such as metal (most common), wood, porcelain, or stone. A gilded object is also described as "gilt". Where metal is gilded, the metal below was tradi ...

, but a small number of large and lavish pieces or sets in solid gold have been found, probably belonging to royalty or major figures.

Decorated metalwork of an everyday nature is frequently recovered from Viking period graves, on account of the widespread practice of making burials accompanied by grave goods. The deceased was dressed in their best clothing and jewelry, and was interred with weapons, tools, and household goods. Less common, but significant nonetheless, are finds of precious metal objects in the form of treasure hoard

A hoard or "wealth deposit" is an archaeological term for a collection of valuable objects or artifacts, sometimes purposely buried in the ground, in which case it is sometimes also known as a cache. This would usually be with the intention of ...

s, many apparently concealed for safe-keeping by owners later unable to recover their contents, although some may have been deposited as offerings to the gods.

Recently, given the increasing popularity and legality of metal-detecting, an increasing frequency of single, chance finds of metal objects and ornaments (most probably representing accidental losses) is creating a fast expanding corpus of new material for study.

Viking coins fit well into this latter category, but nonetheless form a separate category of Viking period artefact, their design and decoration largely independent of the developing styles characteristic of wider Viking artistic endeavor.

Other sources

A non-visual source of information for Viking art lies in skaldic verse, the complex form of oral poetry composed during the Viking Age and passed on until written down centuries later. Several verses speak of painted forms of decoration that have but rarely survived on wood and stone. The 9th-century skald poet Bragi Boddason, for example, cites four apparently unrelated scenes painted on a shield. One of these scenes depicted the god Thor's fishing expedition, which motif is also referenced in a 10th-century poem byÚlfr Uggason

Úlfr Uggason ( Modern Icelandic: ) was an Icelandic skald who lived in the last part of the tenth century.

The '' Laxdæla saga'' tells how he composed his ''Húsdrápa'' for a wedding. Geirmundr married Þuríðr, whose father, Óláfr pái ( ...

describing the paintings in a newly constructed hall in Iceland.

Origins and background

A continuous artistic tradition common to most of north-western Europe and developing from the 4th century CE formed the foundations on which Viking Age art and decoration were built: from that period onwards, the output of Scandinavian artists was broadly focused on varieties of convoluted animal ornamentation used to decorate a wide variety of objects. The art historianBernhard Salin

Carl Bernhard Salin (14January 1861, Örebro20October 1931, Stockholm), was a Swedish archaeologist, cultural historian and museum curator.

Bernhard Salin took the matriculation examination at the Public Grammar School in Nyköping 28May 1880 an ...

was the first to systematise Germanic animal ornament, dividing it into three styles (I, II, and III). The latter two were subsequently subdivided by Arwidsson into three further styles: Style C, flourishing during the 7th century and into the 8th century, before being largely replaced (especially in southern Scandinavia) by Style D. Styles C and D provided the inspiration for the initial expression of animal ornament within the Viking Age, Style E, commonly known as the Oseberg / Broa Style. Both Styles D and E developed within a broad Scandinavian context which, although in keeping with north-western European animal ornamentation generally, exhibited little influence from beyond Scandinavia .

Scholarship

Although preliminary formulations were made in the late 19th century, the history of Viking art first achieved maturity in the early 20th century with the detailed publication of the ornate wood carvings discovered in 1904 as part of the Oserberg ship-burial by the Norwegian archaeologistHaakon Shetelig

Haakon Shetelig (June 25, 1877 – July 22, 1955) was a Norwegian archaeologist, historian and museum director. He was a pioneer in archaeology known for his study of art from the Viking era in Norway. He is most frequently associated with ...

.

Importantly, it was the English archaeologist David M. Wilson, working with his Danish colleague Ole Klindt-Jensen to produce the 1966 survey work ''Viking Art'', who created foundations for the systematic characterization of the field still employed today, together with a developed chronological framework.

David Wilson continued to produce mostly English-language studies on Viking art in subsequent years, joined over recent decades by the Norwegian art-historian Signe Horn Fuglesang with her own series of important publications. Together these scholars have combined authority with accessibility to promote the increasing understanding of Viking art as a cultural expression.

Styles

The art of the Viking Age is organized into a loose sequence of stylistic phases which, despite the significant overlap in style and chronology, may be defined and distinguished on account both of formal design elements and of recurring compositions and motifs:

* Oseberg Style

* Borre Style

* Jellinge Style

* Mammen Style

* Ringerike Style

* Urnes Style

Unsurprisingly, these stylistic phases appear in their purest form in Scandinavia itself; elsewhere in the Viking world, notable admixtures from external cultures and influences frequently appear. In the British Isles, for example, art historians identify distinct, 'Insular' versions of Scandinavian motifs, often directly alongside 'pure' Viking decoration.

The art of the Viking Age is organized into a loose sequence of stylistic phases which, despite the significant overlap in style and chronology, may be defined and distinguished on account both of formal design elements and of recurring compositions and motifs:

* Oseberg Style

* Borre Style

* Jellinge Style

* Mammen Style

* Ringerike Style

* Urnes Style

Unsurprisingly, these stylistic phases appear in their purest form in Scandinavia itself; elsewhere in the Viking world, notable admixtures from external cultures and influences frequently appear. In the British Isles, for example, art historians identify distinct, 'Insular' versions of Scandinavian motifs, often directly alongside 'pure' Viking decoration.

Oseberg Style

Broa style

The Broa style, named after a bridle-mount found at Broa, Halla parish, Gotland, is sometimes included with the Oseberg style, and sometimes held as its own.

The Broa style, named after a bridle-mount found at Broa, Halla parish, Gotland, is sometimes included with the Oseberg style, and sometimes held as its own.

Borre Style

harness

A harness is a looped restraint or support. Specifically, it may refer to one of the following harness types:

* Bondage harness

* Child harness

* Climbing harness

* Dog harness

* Pet harness

* Five-point harness

* Horse harness

* Parrot harness

* ...

mounts recovered from a ship grave in Borre mound cemetery

Borre mound cemetery (Norwegian: ''Borrehaugene'' from the ''Old Norse'' words ''borró'' and ''haugr'' meaning mound) forms part of the Borre National Park at Horten in Vestfold og Telemark, Norway.

It is home to seven large and 21 smaller bu ...

near the village of Borre, Vestfold, Norway, and from which the name of the style derives. Borre Style prevailed in Scandinavia from the late 9th through to the late 10th century, a timeframe supported by dendrochronological data supplied from sites with characteristically Borre Style artifacts

The 'gripping beast' with a ribbon-shaped body continues as a characteristic of this and earlier styles. As with geometric patterning in this phase, the visual thrust of the Borre Style results from the filling of available space: ribbon animal plaits are tightly interlaced and animal bodies are arranged to create tight, closed compositions. As a result, any background is markedly absent – a characteristic of the Borre Style that contrasts strongly with the more open and fluid compositions that prevailed in the overlapping Jellinge Style.

A more particular diagnostic feature of Borre Style lies in a symmetrical, double-contoured 'ring-chain' (or 'ring-braid'), whose composition consists of interlaced circles separated by transverse bars and a lozenge overlay. The Borre ring-chain occasionally terminates with an animal head in high relief, as seen on strap fittings from Borre and Gokstad.

The ridges of designs in metalwork are often nicked to imitate the filigree wire employed in the finest pieces of craftsmanship.

Jellinge Style

The Jellinge Style is a phase of Scandinavian

The Jellinge Style is a phase of Scandinavian animal art

An animal painter is an artist who specialises in (or is known for their skill in) the portrayal of animals.

The ''OED'' dates the first express use of the term "animal painter" to the mid-18th century: by English physician, naturalist and wri ...

during the 10th century.The article ''jellingestil'' in '' Nationalencyklopedin'' (1993). The style is characterized by markedly stylized and often band-shaped bodies of animals. It was originally applied to a complex of objects in Jelling, Denmark, such as Gorm's Cup

Gorm's Cup, also known as the Jelling Cup, is a small silver cup buried with the Danish king Gorm the Old, .

Context

The cup was found in the huge double barrow in which the heathen king Gorm the Old, founder of the Danish monarchy (), and ...

and Harald Bluetooth's great runestone, but more recently the style is included in the Mammen style.

Mammen Style

The Mammen Style takes its name from its type object, an axe recovered from a wealthy male burial marked a mound (Bjerringhø) at Mammen, in Jutland, Denmark (on the basis of dendrochronology, the wood used in construction of the grave chamber was felled in winter 970–971). Richly decorated on both sides with inlaid silver designs, the iron axe was probably a ceremonial parade weapon that was the property of a man of princely status, his burial clothes bearing elaborate embroidery and trimmed with silk and fur.

The Mammen Style takes its name from its type object, an axe recovered from a wealthy male burial marked a mound (Bjerringhø) at Mammen, in Jutland, Denmark (on the basis of dendrochronology, the wood used in construction of the grave chamber was felled in winter 970–971). Richly decorated on both sides with inlaid silver designs, the iron axe was probably a ceremonial parade weapon that was the property of a man of princely status, his burial clothes bearing elaborate embroidery and trimmed with silk and fur.

On one face, the Mammen axe features a large bird with pelleted body, crest, circular eye, and upright head and beak with lappet. A large shell-spiral marks the bird's hip, from which point its thinly elongated wings emerge: the right wing interlaces with the bird's neck, while the left wing interlaces with its body and tail. The outer wing edge displays a semi-circular nick typical of Mammen Style design. The tail is rendered as a triple tendril, the particular treatment of which on the Mammen axe – with open, hook-like ends – forming a characteristic of the Mammen Style as a whole. Complicating the design is the bird's head-lappet, interlacing twice with neck and right wing, whilst also sprouting tendrils along the blade edge. At the top, near the haft, the Mammen axe features an interlaced knot on one side, a triangular human mask (with large nose, moustache and spiral beard) on the other; the latter would prove a favoured Mammen Style motif carried over from earlier styles.

On the other side, the Mammen axe bears a spreading foliate (leaf) design, emanating from spirals at the base with thin, 'pelleted' tendrils spreading and intertwining across the axe head towards the haft.

On one face, the Mammen axe features a large bird with pelleted body, crest, circular eye, and upright head and beak with lappet. A large shell-spiral marks the bird's hip, from which point its thinly elongated wings emerge: the right wing interlaces with the bird's neck, while the left wing interlaces with its body and tail. The outer wing edge displays a semi-circular nick typical of Mammen Style design. The tail is rendered as a triple tendril, the particular treatment of which on the Mammen axe – with open, hook-like ends – forming a characteristic of the Mammen Style as a whole. Complicating the design is the bird's head-lappet, interlacing twice with neck and right wing, whilst also sprouting tendrils along the blade edge. At the top, near the haft, the Mammen axe features an interlaced knot on one side, a triangular human mask (with large nose, moustache and spiral beard) on the other; the latter would prove a favoured Mammen Style motif carried over from earlier styles.

On the other side, the Mammen axe bears a spreading foliate (leaf) design, emanating from spirals at the base with thin, 'pelleted' tendrils spreading and intertwining across the axe head towards the haft.

Ringerike Style

The Ringerike Style receives its name from the Ringerike district north of Oslo, Norway, where the local reddish sandstone was widely employed for carving stones with designs of the style.Only one stone carved in this style, however, has been found in Ringerike itself, at Tanberg, cf. Fugelesang 1980:pl.38.carved stone

Stone carving is an activity where pieces of rough natural stone are shaped by the controlled removal of stone. Owing to the permanence of the material, stone work has survived which was created during our prehistory or past time.

Work carried ...

from Vang in Oppland. Apart from a runic memorial inscription on its right edge, the main field of the Vang Stone is filled with a balanced tendril ornament springing from two shell spirals at the base: the main stems cross twice to terminate in lobed tendrils. At the crossing, further tendrils spring from loops and pear-shaped motifs appear from the tendril centres on the upper loop. Although axial in conception, a basic asymmetry arises in the deposition of the tendrils. Surmounting the tendril pattern appears a large striding animal in double-contoured rendering with spiral hips and a lip lappet. Comparing the Vang Stone animal design with the related animal from the Mammen axe-head, the latter lacks the axiality seen in the Vang Stone and its tendrils are far less disciplined: the Mammen scroll is wavy, while the Vang scroll appears taut and evenly curved, these features marking a key difference between Mammen and Ringerike ornament. The inter-relationship between the two styles is obvious, however, when comparing the Vang Stone animal with that found on the Jelling Stone.

With regard to metalwork, Ringerike Style is best seen in two copper-gilt weather-vanes, from Källunge, Gotland and from Söderala, Hälsingland (the Söderala vane), both in Sweden. The former displays one face two axially-constructed loops in the form of snakes, which in turn sprout symmetrically-placed tendrils. The snake heads, as well as the animal and snake on the reverse, find more florid treatment than on the Vang Stone: all have lip lappets, the snakes bear pigtails, while all animals have a pear-shaped eye with the point directed towards the snout – a diagnostic feature of Ringerike Style.

The Ringerike Style evolved out of the earlier Mammen Style. It received its name from a group of runestones with animal and plant motifs in the Ringerike district north of Oslo. The most common motifs are lions, birds, band-shaped animals and spirals.Moss (2014), p. 44 Some elements appear for the first time in Scandinavian art, such as different types of crosses, palmettes and pretzel-shaped nooses that tie together two motifs. Most of the motifs have counterparts in

With regard to metalwork, Ringerike Style is best seen in two copper-gilt weather-vanes, from Källunge, Gotland and from Söderala, Hälsingland (the Söderala vane), both in Sweden. The former displays one face two axially-constructed loops in the form of snakes, which in turn sprout symmetrically-placed tendrils. The snake heads, as well as the animal and snake on the reverse, find more florid treatment than on the Vang Stone: all have lip lappets, the snakes bear pigtails, while all animals have a pear-shaped eye with the point directed towards the snout – a diagnostic feature of Ringerike Style.

The Ringerike Style evolved out of the earlier Mammen Style. It received its name from a group of runestones with animal and plant motifs in the Ringerike district north of Oslo. The most common motifs are lions, birds, band-shaped animals and spirals.Moss (2014), p. 44 Some elements appear for the first time in Scandinavian art, such as different types of crosses, palmettes and pretzel-shaped nooses that tie together two motifs. Most of the motifs have counterparts in Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

, Insular

Insular is an adjective used to describe:

* An island

* Someone who is isolated and parochial

Insular may also refer to:

Sub-national territories or regions

* Insular Chile

* Insular region of Colombia

* Insular Ecuador, administratively known ...

and Ottonian art.

Urnes Style

The Urnes Style was the last phase of Scandinaviananimal art

An animal painter is an artist who specialises in (or is known for their skill in) the portrayal of animals.

The ''OED'' dates the first express use of the term "animal painter" to the mid-18th century: by English physician, naturalist and wri ...

during the second half of the 11th century and in the early 12th century.The article ''urnesstil'' in '' Nationalencyklopedin'' (1996). The Urnes Style is named after the northern gate of the Urnes stave church

Urnes Stave Church ( no, Urnes stavkyrkje) is a 12th-century stave church at Ornes, along the Lustrafjorden in the municipality of Luster in Vestland county, Norway.

The church sits on the eastern side of the fjord, directly across the fjord f ...

in Norway, but most objects in the style are runestones in Uppland, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

, which is why some scholars prefer to call it the '' Runestone style''.

The style is characterized by slim and stylised animals that are interwoven into tight patterns. The animals heads are seen in profile, they have slender almond-shaped eyes and there are upwardly curled appendages on the noses and the necks.

Early Urnes Style

The early style has received a dating which is mainly based on runestone U 343, runestone U 344 and a silver bowl from c. 1050, which was found at Lilla Valla. The early version of this style on runestones comprises England Runestones referring to the Danegeld andCanute the Great

Cnut (; ang, Cnut cyning; non, Knútr inn ríki ; or , no, Knut den mektige, sv, Knut den Store. died 12 November 1035), also known as Cnut the Great and Canute, was King of England from 1016, King of Denmark from 1018, and King of Norway ...

and works by Åsmund Kåresson.Fuglesang, S.H. ''Swedish runestones of the eleventh century: ornament and dating'', Runeninschriften als Quellen interdisziplinärer Forschung (K.Düwel ed.). Göttingen 1998, pp. 197–218. p. 206

Mid-Urnes Style

The mid-Urnes Style has received a relatively firm dating based on its appearance on coins issued byHarald Hardrada

Harald Sigurdsson (; – 25 September 1066), also known as Harald III of Norway and given the epithet ''Hardrada'' (; modern no, Hardråde, roughly translated as "stern counsel" or "hard ruler") in the sagas, was King of Norway from 1046 t ...

(1047–1066) and by Olav Kyrre (1080–1090). Two wood carvings from Oslo have been dated to c. 1050–1100 and the Hørning plank is dated by dendrochronology

Dendrochronology (or tree-ring dating) is the scientific method of dating tree rings (also called growth rings) to the exact year they were formed. As well as dating them, this can give data for dendroclimatology, the study of climate and atmos ...

to c. 1060–1070. There is, however, evidence suggesting that the mid-Urnes style was developed before 1050 in the manner it is represented by the runemaster

A runemaster or runecarver is a specialist in making runestones.

Description

More than 100 names of runemasters are known from Viking Age Sweden with most of them from 11th-century eastern Svealand.The article ''Runristare'' in ''Nationalencyklo ...

s Fot and Balli.

Late Urnes Style

The mid-Urnes Style would stay popular side by side with the late Urnes style of therunemaster

A runemaster or runecarver is a specialist in making runestones.

Description

More than 100 names of runemasters are known from Viking Age Sweden with most of them from 11th-century eastern Svealand.The article ''Runristare'' in ''Nationalencyklo ...

Öpir. He is famous for a style in which the animals are extremely thin and make circular patterns in open compositions. This style was not unique to Öpir and Sweden, but it also appears on a plank from Bølstad and on a chair from Trondheim, Norway.

The Jarlabanke Runestones show traits both from this late style and from the mid-Urnes style of Fot and Balli, and it was the Fot-Balli type that would mix with the Romanesque style in the 12th century.Fuglesang, S.H. ''Swedish runestones of the eleventh century: ornament and dating'', Runeninschriften als Quellen interdisziplinärer Forschung (K.Düwel ed.). Göttingen 1998, pp. 197–218. p. 207

Urnes-Romanesque Style

The Urnes-Romanesque Style does not appear on runestones which suggests that the tradition of making runestones had died out when the mixed style made its appearance since it is well represented inGotland

Gotland (, ; ''Gutland'' in Gutnish), also historically spelled Gottland or Gothland (), is Sweden's largest island. It is also a province, county, municipality, and diocese. The province includes the islands of Fårö and Gotska Sandön to the ...

and on the Swedish mainland. The Urnes-Romanesque Style can be dated independently of style thanks to representations from Oslo in the period 1100–1175, dendrochronological dating of the Lisbjerg frontal in Denmark to 1135, as well as Irish reliquaries that are dated to the second half of the 12th century.Fuglesang, S.H. ''Swedish runestones of the eleventh century: ornament and dating'', Runeninschriften als Quellen interdisziplinärer Forschung (K.Düwel ed.). Göttingen 1998, pp. 197–218. p. 208

See also

* Migration Period art *Medieval art

The medieval art of the Western world covers a vast scope of time and place, over 1000 years of art in Europe, and at certain periods in Western Asia and Northern Africa. It includes major art movements and periods, national and regional art, gen ...

* Celtic art

* Anglo-Saxon art

Anglo-Saxon art covers art produced within the Anglo-Saxon period of English history, beginning with the Migration period style that the Anglo-Saxons brought with them from the continent in the 5th century, and ending in 1066 with the Norma ...

* Insular art

Insular art, also known as Hiberno-Saxon art, was produced in the post-Roman era of Great Britain and Ireland. The term derives from ''insula'', the Latin term for "island"; in this period Britain and Ireland shared a largely common style dif ...

* Picture stone

* Runestone styles

:''The term "runestone style" in the singular may refer to the Urnes style.''

The style or design of runestones varied during the Viking Age. The early runestones were simple in design, but towards the end of the runestone era they became increas ...

* Interlace

* Saint Manchan's Shrine, Urnes style adapted to Ringerike style.

Notes

References

Background

* Brink, S. with Price, N. (eds) (2008). ''The Viking World'', outledge Worlds Routledge: London and New York, 2008. * Graham-Campbell, J. (2001), ''The Viking World'', London, 2001.General Surveys

* Anker, P. (1970). ''The Art of Scandinavia'', Volume I, London and New York, 1970. * Fuglesang, S.H. (1996). "Viking Art", in Turner, J. (ed.), ''The Grove Dictionary of Art'', Volume 32, London and New York, 1996, pp. 514–27, 531–32. * Graham-Campbell, J. (1980). ''Viking Artefacts: A Select Catalogue'', British Museum Publications: London, 1980. * Graham-Campbell, James (2013). ''Viking Art'', Thames & Hudson, 2013. * Fred S. Kleiner, ''Gardner's Art Through The Ages: The Western Perspective'', Volume I. (Boston, Mass.: Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2009* Roesdahl, E. and Wilson, D.M. (eds) (1992). ''From Viking to Crusader: Scandinavia and Europe 800–1200'', Copenhagen and New York, 1992. xhibition catalogue * Williams, G., Pentz, P. and Wemhoff, M. (eds), ''Vikings: Life and Legend'', British Museum Press: London, 2014. xhibition catalogue * Wilson, D.M. & Klindt-Jensen, O. (1980). ''Viking Art'', second edition, George Allen and Unwin, 1980.

Specialist Studies

* Arwidsson, G. (1942a). ''Valsgärdestudien I. Vendelstile: Email und Glas im 7.-8. Jahrhundert'',cta Musei antiquitatum septentrionalium Regiae Universitatis Upsaliensis 2 CTA may refer to:

Legislation

*Children's Television Act, American legislation passed in 1990 that enforces a certain degree of educational television

*Counter-Terrorism Act 2008

*Criminal Tribes Act, British legislation in India passed in 1871 wh ...

Uppsala: Almqvist, 1942.

* Arwidsson, G. (1942b). ''Die Gräberfunde von Valsgärde I, Valsgärde 6'', cta Musei antiquitatum septentrionalium Regiae Universitatis Upsaliensis 1 Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1942.

* Bailey, R.N. (1980). ''Viking Age Sculpture in Northern England'', Collins Archaeology: London, 1980.

* Bonde, N. and Christensen, A.E. (1993). "Dendrochronological dating of the Viking Age ship burials at Oseberg, Gokstad and Tune, Norway", ''Antiquity'' 67 (1993), pp. 575–83.

* Bruun, Per (1997)."The Viking Ship," ''Journal of Coastal Research'', 4 (1997): 1282–89. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4298737

* Capelle, T. (1968). ''Der Metallschmuck von Haithabu: Studien zur wikingischen Metallkunst'', ie Ausgrabungen in Haithabu 5 Neumunster: K. Wachholtz, 1968.

* James Curle, "A Find of Viking Relics in the Hebrides," ''The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs'' 162 (1916): 241–43. https://www.jstor.org/stable/860122

* Fuglesang, S.H. (1980). ''Some Aspects of the Ringerike Style: A Phase of 11th Century Scandinavian Art'', ediaeval Scandinavia Supplements University Press of Southern Denmark: Odense, 1980.

* Fuglesang, S.H. (1981). "Stylistic Groups in Late Viking and Early Romanesque Art", ''Acta ad Archaeologiam et Artium Historiam Pertinentia'', eries altera in 8°I, 1981, pp. 79–125.

* Fuglesang, S.H. (1982). "Early Viking Art", ''Acta ad Archaeologiam et Artium Historiam Pertinentia'' eries altera in 8°II, 1982, pp. 125–73.

* Fuglesang, S.H. (1991). "The Axe-Head from Mammen and the Mammen Style", in Iversen (1991), pp. 83–108.

* Fuglesang, S.H. (1998). "Swedish Runestones of the Eleventh Century: Ornament and Dating", in Düwel, K. and Nowak, S. (eds), ''Runeninschriften als Quellen interdisziplinärer Forschung: Abhandlungen des vierten internationalen Symposiums über Runen und Runeninschriften in Gottingen vom 4.-9. August 1995'', Göttingen: Walter de Gruyter, 1998, pp. 197–218.

* Fuglesang, S.H. (2001). "Animal Ornament: the Late Viking Period", in Müller-Wille and Larsson (eds) (2001), pp. 157–94.

* Fuglesang, S.H. (2013). "Copying and Creativity in Early Viking Ornament", in Reynolds and Webster

Webster may refer to:

People

*Webster (surname), including a list of people with the surname

*Webster (given name), including a list of people with the given name

Places Canada

*Webster, Alberta

*Webster's Falls, Hamilton, Ontario

United State ...

(eds) (2013), pp. 825–41.

* Hedeager, L. (2003). "Beyond Mortality: Scandinavian Animal Styles AD 400–1200", in Downes, J. and Ritchie, A. (eds), ''Sea Change: Orkney and Northern Europe in the Later Iron Age AD 300–800'', Balgavies, 2003, pp. 127–36.

* Iversen, M. (ed.) (1991). ''Mammen: Grav, Kunst og Samfund i Vikingetid'', ysk Arkæologisk Selskabs Skrifter XXVIII Højbjerg, 1991.

* Kershaw, J. (2008). "The Distribution of the 'Winchester' Style in Late Saxon England: Metalwork Finds from the Danelaw", ''Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History 15 (2008), pp. 254–69Academic.edu

* Krafft, S. (1956). ''Pictorial Weavings from the Viking Age'', Oslo: Dreyer, 1956. * Lang, J.T. (1984). "The hogback: a Viking colonial monument", ''Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History'' 3 (1984), pp. 85–176. * Lang, J.T. (1988). ''Viking Age Decorated Wood: A Study of its Ornament and Style'', Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1988. * Moss, Rachel. ''Medieval c. 400—c. 1600: Art and Architecture of Ireland''. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014. * Müller-Wille, M. and Larsson, L.O. (eds) (2001). ''Tiere – Menschen – Götter: Wikingerzeitliche Kunststile und ihre Neuzeitliche Rezeption'', Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Gottingen, 2001. * Myhre, B. (1992). "The Royal Cemetery at Borre, Vestfold: A Norwegian Centre in a European Periphery", in Carter, M. (ed.), ''The Age of Sutton Hoo. The Seventh Century in North-West Europe'', Woodbridge: Boydell, 1992. * Owen, O. (2001). "The strange beast that is the English Urnes Style", in Graham-Campbell, J. ''et al.'' (eds), ''Vikings and the Danelaw – Selected Papers from the Proceedings of the Thirteenth Viking Congress'', Oxford: Oxbow, 2001, pp. 203–22. * Paterson, C. (2002). "From Pendants to Brooches – The Exchange of Borre and Jelling Style Motifs across the North Sea", ''Hikuin'' 29 (2002), pp. 267–76. * Reynolds, A. and Webster, L. (eds) (2013), ''Early Medieval Art and Archaeology in the Northern World—Studies in Honour of James Graham-Campbell'', Brill: Leiden and Boston, 2013. * Richards, J.D. and Naylor, J. (2010). "The metal detector and the Viking Age in England", in Sheehan, J. and Corráin, D. Ó. (eds), ''The Viking Age. Ireland and the West. Proceedings of the Fifteenth Viking Congress'', Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2010, pp. 338–52. * Roesdahl, E. (1994). "Dendrochronology and Viking Studies in Denmark, with a Note on the Beginning of the Viking Age", in Abrosiani, B. and Clarke, H. (eds), ''Developments around the Baltic and the North Sea in the Viking Age'', Stockholm: Birka Project for Riksantikvarieämbetet and Statens Historiska Museer, 1994, pp. 106–16. * Roesdahl, E. (2010a). "Viking Art in European Churches (Cammin – Bamberg – Prague – León)", in Sheehan and Ó Corráin (eds) (2010), pp. 149–64. * Roesdahl, E. (2010b). "From Scandinavia to Spain: a Viking Age Reliquary in León and its Significance", in Sheehan, J. and Corráin, D. Ó. (eds), ''The Viking Age. Ireland and the West. Proceedings of the Fifteenth Viking Congress'', Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2010, pp. 353–60. * Salin, Bernhard (1904). ''Die altgermanische Thieronamentik'', Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand, 1904. * Sheehan, J. and Ó Corráin, D. (eds) (2010). ''The Viking Age: Ireland and the West. Proceedings of the XVth Viking Congress, Cork, 2005.'', Dublin and Portland: Four Courts Press, 2010. * Shetelig, H. (1920). ''Osebergfundet'', Volume III, Kristiania, 1920. * Wilson, D.M. (2001). "The Earliest Animal Styles of the Viking Age", in Müller-Wille and Larsson (eds) (2001), pp. 131–56. * Wilson, D.M. (2008a). "The Development of Viking Art", in Brink with Price (2008), pp. 323–38. * Wilson, D.M. (2008b). ''The Vikings in the Isle of Man'', Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2008.

External links

British Museum: Explore / World Cultures: Vikings

* Sorabella, Jean

in ''Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History'', New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. Updated October 2002. *

Age of spirituality : late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century

' from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Examples of the Broa and Oseberg Style

Borrehaugene

* Jane Kershaw

Viking-Age Scandinavian art styles and their appearance in the British Isles – Part 1: Early Viking-Age art styles

– The Finds Research Group AD 700–1700, Datasheet 42, 2010. (Academia.edu registration required). * Jane Kershaw

Viking-Age Scandinavian art styles and their appearance in the British Isles Part 2: Late Viking-Age art styles

– The Finds Research Group AD 700–1700, Datasheet 43, 2011. (Academia.edu registration required). {{DEFAULTSORT:Viking Age art