Jalal Al-e-Ahmad on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

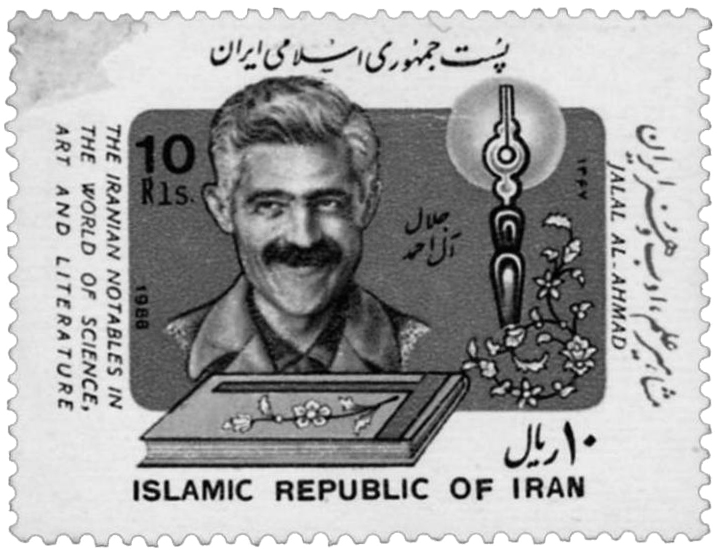

Seyyed Jalāl Āl-e-Ahmad (; December 2, 1923September 9, 1969) was a prominent

Al-e-Ahmad used a

Al-e-Ahmad used a

, ''Tehran Times'', November 20, 2011. In some years there is no top winner, other notables receive up to 25 gold coins. Categories include "Novel", "Short story", "Literary criticism" and "History and documentations"."5000 works compete in 4th Jalal Al-e Ahmad Award"

, Iran Radio Culture, IRIB World Service, August 17, 2011. The award was confirmed by the Supreme Cultural Revolution Council in 2005, the first award was presented in 2008.

Al-i Ahmad, Jalal

A biography by

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

ian novelist, short-story writer, translator, philosopher, socio-political critic, sociologist, as well as an anthropologist

An anthropologist is a scientist engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropologists study aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms, values ...

who was "one of the earliest and most prominent of contemporary Iranian ethnographers

Ethnography is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. It explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject of the study. Ethnography is also a type of social research that involves examining ...

". He popularized the term '' gharbzadegi'' – variously translated in English as "westernstruck", "westoxification", and "Occident

The Occident is a term for the West, traditionally comprising anything that belongs to the Western world. It is the antonym of the term ''Orient'', referring to the Eastern world. In English, it has largely fallen into disuse. The term occidental ...

osis" – producing a holistic ideological critique of the West "which combined strong themes of Frantz Fanon

Frantz Omar Fanon (, ; ; 20 July 1925 – 6 December 1961) was a French West Indian psychiatrist, political philosopher, and Marxist from the French colony of Martinique (today a French department). His works have become influential in the ...

and Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

".

Personal life

Jalal was born inTehran

Tehran (; , ''Tehrân'') is the capital and largest city of Iran. It is the capital of Tehran province, and the administrative center for Tehran County and its Central District (Tehran County), Central District. With a population of around 9. ...

, into a religious family – his father was a cleric – "originally from the village of Aurazan in the Taliqan district bordering Mazandaran

Mazandaran Province (; ) is one of the 31 provinces of Iran. Its capital is the city of Sari, Iran, Sari. Located along the southern coast of the Caspian Sea and in the adjacent Central Alborz mountain range and Hyrcanian forests, it is border ...

in northern Iran

Northern Iran (), is a geographical term that refers to a relatively large and fertile area, consisting of the southern border of the Caspian Sea and the Alborz mountains.

It includes the provinces of Gilan, Mazandaran, and Golestan (ancie ...

, and in due time Jalal was to travel there, exerting himself actively for the welfare of the villagers and devoting to them the first of his anthropological

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behaviour, wh ...

monograph

A monograph is generally a long-form work on one (usually scholarly) subject, or one aspect of a subject, typically created by a single author or artist (or, sometimes, by two or more authors). Traditionally it is in written form and published a ...

s". He was a cousin of Mahmoud Taleghani. After elementary school Al-e-Ahmad was sent to earn a living in the Tehran bazaar, but also attended Marvi Madreseh for a religious education, and without his father's permission, night classes at the Dar ul-Fonun. He went to Seminary of Najaf

Najaf is the capital city of the Najaf Governorate in central Iraq, about 160 km (99 mi) south of Baghdad. Its estimated population in 2024 is about 1.41 million people. It is widely considered amongst the holiest cities of Shia Islam an ...

in 1944 but returned home very quickly. He became "acquainted with the speech and words of Ahmad Kasravi" and was unable to commit to the clerical career his father and brother had hoped he would take, describing it as "a snare in the shape of a cloak and an aba." He describes his family as a religious family in the autobiographical sketch that published after his death in 1967.

In 1946 he earned an M.A. in Persian literature

Persian literature comprises oral compositions and written texts in the Persian language and is one of the world's oldest literatures. It spans over two-and-a-half millennia. Its sources have been within Greater Iran including present-day ...

from Tehran Teachers College and became a teacher, at the same time making a sharp break with his religious family that left him "completely on his own resources." He pursued academic studies further and enrolled in a doctoral program of Persian literature

Persian literature comprises oral compositions and written texts in the Persian language and is one of the world's oldest literatures. It spans over two-and-a-half millennia. Its sources have been within Greater Iran including present-day ...

at Tehran University

The University of Tehran (UT) or Tehran University (, ) is a public collegiate university in Iran, and the oldest and most prominent Iranian university located in Tehran. Based on its historical, socio-cultural, and political pedigree, as well as ...

but quit before he had defended his dissertation in 1951. In 1950, he married Simin Daneshvar, a well-known Persian novelist

A novelist is an author or writer of novels, though often novelists also write in other genres of both fiction and non-fiction. Some novelists are professional novelists, thus make a living wage, living writing novels and other fiction, while other ...

. Jalal and Simin were infertile, a topic that was reflected in some of Jalal's works.

He died in Asalem, a rural region in the north of Iran, inside a cottage which was built almost entirely by himself. He was buried in Firouzabadi mosque

A mosque ( ), also called a masjid ( ), is a place of worship for Muslims. The term usually refers to a covered building, but can be any place where Salah, Islamic prayers are performed; such as an outdoor courtyard.

Originally, mosques were si ...

in Ray, Iran

Shahre Ray, Shahr-e Ray, Shahre Rey, or Shahr-e Rey (, ) or simply Ray or Rey (), is the capital of Ray County, Iran, Rey County in Tehran Province, Iran. Formerly a distinct city, it has now been absorbed into the metropolitan area of Greater T ...

. According to rumors he was poisoned by SAVAK which was vehemently contradicted by his wife who confirmed the official cause of death, pulmonary embolism due to alcohol and nicotine abuse.

In 2010, the Tehran Cultural Heritage, Tourism, and Handicrafts Department bought the house in which both Jalal Al-e Ahmad and his brother Shams were born and lived.

Political life

Gharbzadegi: "Westoxification"

Al-e-Ahmad is perhaps most famous for using the term Gharbzadegi, originally coined by Ahmad Fardid and variously translated in English as weststruckness, westoxification and occidentosis - in a book by the same name ''Occidentosis: A Plague from the West'', self-published by Al-e Ahmad in Iran in 1962. In the book Al-e-Ahmad developed a "stingingcritique

Critique is a method of disciplined, systematic study of a written or oral discourse. Although critique is frequently understood as fault finding and negative judgment, Rodolphe Gasché (2007''The honor of thinking: critique, theory, philosophy ...

of Western technology and by implication of Western `civilization` itself". He argued that the decline of traditional Iranian industries such as carpet weaving was the beginning of Western "economic and existential

Existentialism is a family of philosophical views and inquiry that explore the human individual's struggle to lead an authentic life despite the apparent absurdity or incomprehensibility of existence. In examining meaning, purpose, and value ...

victories over the East."Brumberg, ''Reinventing Khomeini: The Struggle for Reform in Iran'', University of Chicago Press, 2001, p.65 His criticism of Western technology and mechanization was influenced, through Ahmad Fardid, by Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (; 26 September 1889 – 26 May 1976) was a German philosopher known for contributions to phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. His work covers a range of topics including metaphysics, art, and language.

In April ...

, and he also considered Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was a French philosopher, playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and literary criticism, literary critic, considered a leading figure in 20th ...

as another seminal philosophical influence. There was also Ernst Jünger

Ernst Jünger (; 29 March 1895 – 17 February 1998) was a German author, highly decorated soldier, philosopher, and entomology, entomologist who became publicly known for his World War I memoir ''Storm of Steel''.

The son of a successful busin ...

, to whom Jalal ascribes a major part in the genealogy

Genealogy () is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages. Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kin ...

of his famous book, and he goes on to say "Junger and I were both exploring more or less the same subject, but from two viewpoints. We were addressing the same question, but in two languages." Throughout the twelve chapters of the essay, Al-e Ahmad defines gharbzadegi as a contagious disease, lists its initial symptoms and details its etiology

Etiology (; alternatively spelled aetiology or ætiology) is the study of causation or origination. The word is derived from the Greek word ''()'', meaning "giving a reason for" (). More completely, etiology is the study of the causes, origins ...

, diagnoses local patients, offers a prognosis for patients in other localities, and consults with other specialists to suggest a rather hazy antidote.

His message was embraced by the Ayatollah Khomeini, who wrote in 1971 that "The poisonous culture ofand became part of the ideology of the 1979imperialism Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of Power (international relations), power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power (diplomatic power and cultura ...spenetrating to the depths of towns and villages throughout the Muslim world, displacing the culture of theQur'an The Quran, also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation directly from God ('' Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which consist of individual verses ('). Besides ..., recruiting our youth en masse to the service of foreigners and imperialists..."

Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution (, ), also known as the 1979 Revolution, or the Islamic Revolution of 1979 (, ) was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynasty in 1979. The revolution led to the replacement of the Impe ...

, which emphasized nationalization

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English)

is the process of transforming privately owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization contrasts with p ...

of industry, independence in all areas of life from both the Soviet and the Western world, and "self-sufficiency" in economics. He was also one of the main influences of Ahmadinejad.

Discourse of authenticity

Ali Mirsepasi believes that Al-e Ahmad is concerned with the discourse of authenticity along with Shariati. According to Mirsepasi, Jalal extended his critiques of thehegemonic

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one state over other states, either regional or global.

In Ancient Greece (ca. 8th BC – AD 6th c.), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' ...

power of the West. The critique is centered on the concept of westoxication. Al-e Ahmad attacks secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin , or or ), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. The origins of secularity can be traced to the Bible itself. The concept was fleshed out through Christian hi ...

intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and Human self-reflection, reflection about the nature of reality, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative problems. Coming from the wor ...

s with the concept

A concept is an abstract idea that serves as a foundation for more concrete principles, thoughts, and beliefs.

Concepts play an important role in all aspects of cognition. As such, concepts are studied within such disciplines as linguistics, ...

. He believes that the intellectuals could not construct effectively an authentically Iranian modernity

Modernity, a topic in the humanities and social sciences, is both a historical period (the modern era) and the ensemble of particular Society, socio-Culture, cultural Norm (social), norms, attitudes and practices that arose in the wake of the ...

. On this occasion, he posed the concept of “return” to an Islamic culture which is authentic at the same time. Al-e Ahmad believed that to avoid the homogenizing and alienating forces of modernity, it is necessary to return to the roots of Islamic culture. In fact, Al Ahmad wanted to reimagine modernity with Iranian-Islamic tradition.

Political activism

Al-e-Ahmad joined the communist Tudeh Party along with his mentor Khalil Maleki shortly after World War II. They "were too independent for the party" and resigned in protest over the lack of democracy and the "nakedly pro-Soviet" support for Soviet demands for oil concession and occupation of IranianAzerbaijan

Azerbaijan, officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, is a Boundaries between the continents, transcontinental and landlocked country at the boundary of West Asia and Eastern Europe. It is a part of the South Caucasus region and is bounded by ...

. They formed an alternative party the Socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

Society of the Iranian Masses in January 1948 but disbanded it a few days later when Radio Moscow attacked it, unwilling to publicly oppose "what they considered the world's most progressive nations." Nonetheless, the dissent of Al-e-Ahmad and Maleki marked "the end of the near hegemony of the party over intellectual life."

He later helped found the pro- Mossadegh Tudeh Party, one of the component parties of the National Front, and then in 1952 a new party called the Third Force. Following the 1953 Iranian coup d'état

The 1953 Iranian coup d'état, known in Iran as the 28 Mordad coup d'état (), was the overthrow of Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh on 19 August 1953. Led by the Iranian army and supported by the United States and the United Kingdom, the co ...

Al-e-Ahmad was imprisoned for several years and "so completely lost faith in party politics" that he signed a letter of repentance published in an Iranian newspaper declaring that he had "resigned from the Third Force, and completely abandoned politics." However, he remained a part of the Third Force political group, attending its meetings, and continuing to follow the political mentorship of Khalil Maleki until their deaths in 1969. In 1963, visited Israel for two weeks, and in his account of his trip stated that the fusion of the religious and the secular he discerned in Israel afforded a potential model for the state of Iran. Despite his relationship with the secular Third Force group, Al-e-Ahmad became more sympathetic to the need for religious leadership in the transformation of Iranian politics, especially after the rise of Ayatollah Khomeini in 1963.

Literary life

colloquial

Colloquialism (also called ''colloquial language'', ''colloquial speech'', ''everyday language'', or ''general parlance'') is the linguistic style used for casual and informal communication. It is the most common form of speech in conversation amo ...

style in prose

Prose is language that follows the natural flow or rhythm of speech, ordinary grammatical structures, or, in writing, typical conventions and formatting. Thus, prose ranges from informal speaking to formal academic writing. Prose differs most n ...

. In this sense, he is a follower of avant-garde

In the arts and literature, the term ''avant-garde'' ( meaning or ) identifies an experimental genre or work of art, and the artist who created it, which usually is aesthetically innovative, whilst initially being ideologically unacceptable ...

Persian novelists like Mohammad-Ali Jamalzadeh. Since the subjects of his works (novels, essays, travelogues, and ethnographic

Ethnography is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. It explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject of the study. Ethnography is also a type of social research that involves examining ...

monograph

A monograph is generally a long-form work on one (usually scholarly) subject, or one aspect of a subject, typically created by a single author or artist (or, sometimes, by two or more authors). Traditionally it is in written form and published a ...

s) are usually cultural, social, and political issues, symbol

A symbol is a mark, Sign (semiotics), sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, physical object, object, or wikt:relationship, relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by cr ...

ic representations and sarcastic expressions are regular patterns in his books. A distinct characteristic of his writings is his honest examination of subjects, regardless of possible reactions from political, social, or religious powers.

On the invitation of Richard Nelson Frye

Richard Nelson Frye (January 10, 1920 – March 27, 2014) was an American scholar of Iranian studies, Iranian and Central Asian studies, and Aga Khan Professor Emeritus of Iranian Studies at Harvard University. His professional areas of inte ...

, Al-e-Ahmad spent a summer at Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

, as part of a Distinguished Visiting Fellowship program established by Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (May 27, 1923 – November 29, 2023) was an American diplomat and political scientist who served as the 56th United States secretary of state from 1973 to 1977 and the 7th National Security Advisor (United States), natio ...

for supporting promising Iranian intellectuals.

Al-e-Ahmad rigorously supported Nima Yushij (father of modern Persian poetry

Persian literature comprises oral compositions and written texts in the Persian language and is one of the world's oldest literatures. It spans over two-and-a-half millennia. Its sources have been within Greater Iran including present-day ...

) and had an important role in the acceptance of Nima's revolutionary style.

In "a short but prolific career", his writings "came to fill over thirty-five volumes."

Novels and novellas

*''The School Principal'' *''By the Pen'' *''The Tale of Beehives'' *''The Cursing of the Land'' *''A Stone upon a Grave'' Many of his novels, including the first two in the list above, have been translated into English.Short stories

* "Thesetar

A setar (, ) (lit: "Three String (music), Strings") is a stringed instrument, a type of lute used in Persian traditional music, played solo or accompanying voice. It is a member of the tanbur family of long-necked lutes with a range of more than ...

"

* "Of our suffering"

* "Someone else's child"

* "Pink nail-polish"

* "The Chinese flower pot"

* "The postman"

* "The treasure"

* "The Pilgrimage"

* "Sin"

Critical essays

*"Seven essays" *"Hurried investigations" *"Plagued by the West" ('' Gharbzadegi'')Monographs

Jalal traveled to far-off, usually poor, regions of Iran and tried to document their life, culture, and problems. Some of these monographs are: *"Owrazan" *" Tat people of Block-e-Zahra" *" Kharg Island, the unique pearl of thePersian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

"

Travelogues

*''A Straw inMecca

Mecca, officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, is the capital of Mecca Province in the Hejaz region of western Saudi Arabia; it is the Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow valley above ...

''

*''A Journey to Russia''

*''A Journey to Europe''

*''A Journey to the Land of Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

'' ("The land of Azrael")

*''A Journey to America''

Translations

*''The Gambler'' byFyodor Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist and journalist. He is regarded as one of the greatest novelists in both Russian literature, Russian and world literature, and many of his works are consider ...

*''L'Etranger'' by Albert Camus

Albert Camus ( ; ; 7 November 1913 – 4 January 1960) was a French philosopher, author, dramatist, journalist, world federalist, and political activist. He was the recipient of the 1957 Nobel Prize in Literature at the age of 44, the s ...

*''Les mains sales'' by Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was a French philosopher, playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and literary criticism, literary critic, considered a leading figure in 20th ...

*''Return from the U.S.S.R.'' by André Gide

André Paul Guillaume Gide (; 22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951) was a French writer and author whose writings spanned a wide variety of styles and topics. He was awarded the 1947 Nobel Prize in Literature. Gide's career ranged from his begi ...

*''Rhinoceros'' by Eugène Ionesco

Eugène Ionesco (; ; born Eugen Ionescu, ; 26 November 1909 – 28 March 1994) was a Romanian-French playwright who wrote mostly in French, and was one of the foremost figures of the French avant-garde theatre#Avant-garde, French avant-garde th ...

Jalal Al-e Ahmad Literary Award

The Jalal Al-e Ahmad Literary Award is an Iranianliterary award

A literary award or literary prize is an award presented in recognition of a particularly lauded Literature, literary piece or body of work. It is normally presented to an author. Organizations

Most literary awards come with a corresponding award c ...

presented yearly since 2008. Every year, an award is given to the best Iranian authors on the birthday of the renowned Persian writer Jalal Al-e Ahmad. The top winner receives 110 Bahar Azadi gold coins (about $33,000), making it Iran's most lucrative literary award." “War Road” author not surprised over lucrative Jalal award", ''Tehran Times'', November 20, 2011. In some years there is no top winner, other notables receive up to 25 gold coins. Categories include "Novel", "Short story", "Literary criticism" and "History and documentations"."5000 works compete in 4th Jalal Al-e Ahmad Award"

, Iran Radio Culture, IRIB World Service, August 17, 2011. The award was confirmed by the Supreme Cultural Revolution Council in 2005, the first award was presented in 2008.

See also

* Gholam-Hossein Sā'edi * Ahmad Fardid * Jalal Al-e Ahmad Literary AwardsReferences

External links

Al-i Ahmad, Jalal

A biography by

Iraj Bashiri

Iraj Bashiri (; born July 31, 1940) is professor of history at the University of Minnesota, United States, and one of the leading scholars in the fields of Central Asian studies and Iranian studies. Fluent in English, Persian language, Persian, ...

, University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota Twin Cities (historically known as University of Minnesota) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in the Minneapolis–Saint Paul, Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint ...

.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Al-E-Ahmad, Jalal

1923 births

1969 deaths

Al-e Ahmad, Jalal

Al-e Ahmad, Jalal

Al-e Ahmad, Jalal

Al-e Ahmad, Jalal

Al-e Ahmad, Jalal

Al-e Ahmad, Jalal

20th-century Iranian novelists

20th-century Iranian short story writers

Toilers Party of the Iranian Nation politicians

Tudeh Party of Iran members

Third Force (Iran) politicians

League of Iranian Socialists politicians

20th-century Iranian male writers

Iranian Writers Association members

20th-century anthropologists

20th-century Iranian philosophers

Muslim socialists

Iranian socialists