Jack Sheppard (other) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Sheppard (4 March 1702 – 16 November 1724), nicknamed "Honest Jack", was a notorious English

Unable to support her family without her husband's income, Sheppard's mother sent him to Mr Garrett's School, a

Unable to support her family without her husband's income, Sheppard's mother sent him to Mr Garrett's School, a

By this time, Sheppard was a hero to a segment of the population, being a

By this time, Sheppard was a hero to a segment of the population, being a

Sheppard's final period of liberty lasted just two weeks. He disguised himself as a beggar and returned to the city. He broke into the Rawlins brothers'

Sheppard's final period of liberty lasted just two weeks. He disguised himself as a beggar and returned to the city. He broke into the Rawlins brothers'

There was a spectacular public reaction to Sheppard's deeds, which were cited favourably as an example in newspapers. Pamphlets, broadsheets, and ballads were all devoted to his amazing experiences, real and fictional, and his story was adapted for the stage almost immediately. ''Harlequin Sheppard'', a

There was a spectacular public reaction to Sheppard's deeds, which were cited favourably as an example in newspapers. Pamphlets, broadsheets, and ballads were all devoted to his amazing experiences, real and fictional, and his story was adapted for the stage almost immediately. ''Harlequin Sheppard'', a  Sheppard's tale was revived during the first half of the 19th century. A

Sheppard's tale was revived during the first half of the 19th century. A

''The History of the Remarkable Life of John Sheppard''

London: 1724. Retrieved 5 February 2007. * Howson, Gerald. ''Thief-Taker General: Jonathan Wild and the Emergence of Crime and Corruption as a Way of Life in Eighteenth-Century England.'' New Brunswick, NJ and Oxford, UK: 1970. * Linebaugh, Peter. ''The London Hanged: Crime and Civil Society in the Eighteenth Century.'' Verso, 2003, * Lynch, Jack (editor)

Retrieved 5 February 2007. * Mackay, Charles. ''Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds''. Wordsworth Editions, (1841) 1999 edition. . * Moore, Lucy. ''The Thieves' Opera.'' Viking, 1997, * Mullan, John, and Christopher Reid. ''Eighteenth-Century Popular Culture: A Selection''. Oxford University Press, 2000. . * Norton, Rictor. ''Early Eighteenth-Century Newspaper Reports: A Sourcebook''

Retrieved 5 February 2007. * Sugden, Philip. "John Sheppard" in Matthew, H.C.G. and Brian Harrison, eds. ''

Ordinary's Account of 4 September 1724

Reference (docket) t17240812-52. * Anon (often attributed to Defoe). ''A Narrative of All the Robberies, Escapes, Etc. of John Sheppard''. 1724. * Bleackley, Horace, ''Trial of Jack Sheppard''. Wm Gaunt & Sons, (1933) 1996 edition. . * G.E. ''Authentick Memoirs of the Life and Surprising Adventures of John Sheppard by Way of Familiar Letters from a Gentleman in Town.'' 1724. * Gatrell, V.A. ''The Hanging Tree: Execution and the English People 1770–1868''. Oxford University Press, 1996. . * Hibbert, Christopher. ''The Road to Tyburn: The story of Jack Sheppard and the Eighteenth-Century London Underworld''. New York: The World Publishing Company, 1957. (2001 Penguin reprint: ) * Linnane, Fergus. ''The Encyclopedia of London Crime''. Sutton Publishing, 2003. . * Meisel, Martin. (1983) ''Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-Century England''. Princeton. * Rawlings, Philip. ''Drunks, Whores, and Idle Apprentices: Criminal Biographies of the Eighteenth Century''. Routledge (UK), 1992. . * Rogers, Pat. ''Daniel Defoe: The Critical Heritage''. Routledge (UK), 1995. .

Jack Sheppard

from the

Project Gutenberg etext

of

''The Thief-Taker Hangings: How Daniel Defoe, Jonathan Wild, and Jack Sheppard Captivated London and Created the Celebrity Criminal'' by Aaron Skirboll

{{DEFAULTSORT:Sheppard, Jack 1702 births 1724 deaths 1723 crimes in Europe Crime in London British people executed for robbery English criminals English escapees Escapees from England and Wales detention Executed people from London Fugitives People from Spitalfields People executed at Tyburn People executed by England and Wales by hanging People executed by the Kingdom of Great Britain

thief

Theft (, cognate to ) is the act of taking another person's property or services without that person's permission or consent with the intent to deprive the rightful owner of it. The word ''theft'' is also used as a synonym or informal short ...

and prison escape

A prison escape (also referred to as a bust out, breakout, jailbreak, jail escape or prison break) is the act of an Prisoner, inmate leaving prison through unofficial or illegal ways. Normally, when this occurs, an effort is made on the part o ...

e of early 18th-century London.

Born into a poor family, he was apprentice

Apprenticeship is a system for training a potential new practitioners of a Tradesman, trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study. Apprenticeships may also enable practitioners to gain a license to practice in ...

d as a carpenter, but began committing theft and burglary in 1723 with little more than a year of his training to complete. He was arrested and imprisoned five times in 1724, but escaped four times from prison, making him notorious, though popular with the poorer classes. Ultimately, he was caught, convicted, and hanged

Hanging is killing a person by suspending them from the neck with a noose or ligature strangulation, ligature. Hanging has been a standard method of capital punishment since the Middle Ages, and has been the primary execution method in numerou ...

at Tyburn

Tyburn was a Manorialism, manor (estate) in London, Middlesex, England, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone. Tyburn took its name from the Tyburn Brook, a tributary of the River Westbourne. The name Tyburn, from Teo Bourne ...

, ending his brief criminal career after less than two years. The inability of the notorious "Thief-Taker General" Jonathan Wild

Jonathan Wild, also spelled Wilde (1682 or 1683 – 24 May 1725), was an English thief-taker and a major figure in London's criminal underworld, notable for operating on both sides of the law, posing as a public-spirited vigilante entitled th ...

to control Sheppard, and injuries suffered by Wild at the hands of Sheppard's colleague Joseph "Blueskin" Blake, resulted in Wild's demise as a criminal boss.

Sheppard was as renowned for his attempts to escape from prison as he was for his crimes. An autobiographical

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life, providing a personal narrative that reflects on the author's experiences, memories, and insights. This genre allows individuals to share thei ...

"Narrative", thought to have been ghostwritten by Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; 1660 – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, merchant and spy. He is most famous for his novel ''Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its number of translati ...

, was sold at his execution, quickly followed by popular plays. The character of Macheath

Captain Macheath is a fictional character who appears both in John Gay's ''The Beggar's Opera'' (1728), its sequel ''Polly'' (1777), and 150 years later in Bertolt Brecht's ''The Threepenny Opera'' (1928).

Origins

Macheath made his first appear ...

in John Gay

John Gay (30 June 1685 – 4 December 1732) was an English poet and dramatist and member of the Scriblerus Club. He is best remembered for ''The Beggar's Opera'' (1728), a ballad opera. The characters, including Captain Macheath and Polly Peach ...

's ''The Beggar's Opera

''The Beggar's Opera'' is a ballad opera in three acts written in 1728 by John Gay with music arranged by Johann Christoph Pepusch. It is one of the watershed plays in Augustan drama and is the only example of the once thriving genre of sati ...

'' (1728) was based on Sheppard, keeping him well known for more than 100 years. He returned to the public consciousness around 1840, when William Harrison Ainsworth

William Harrison Ainsworth (4 February 18053 January 1882) was an English historical novelist born at King Street in Manchester. He trained as a lawyer, but the legal profession held no attraction for him. While completing his legal studies in ...

wrote a novel entitled ''Jack Sheppard

John Sheppard (4 March 1702 – 16 November 1724), nicknamed "Honest Jack", was a notorious English thief and prison escapee of early 18th-century London.

Born into a poor family, he was apprenticed as a carpenter, but began committing thef ...

'', with illustrations by George Cruikshank

George Cruikshank or Cruickshank ( ; 27 September 1792 – 1 February 1878) was a British caricaturist and book illustrator, praised as the "modern William Hogarth, Hogarth" during his life. His book illustrations for his friend Charles Dicken ...

. The popularity of his tale, and the fear that others would be drawn to emulate his behaviour, caused the authorities to refuse to license

A license (American English) or licence (Commonwealth English) is an official permission or permit to do, use, or own something (as well as the document of that permission or permit).

A license is granted by a party (licensor) to another part ...

any plays in London with "Jack Sheppard" in the title for forty years.

Early life

Sheppard was born in White's Row, inLondon

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

's Spitalfields

Spitalfields () is an area in London, England and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in East London and situated in the East End of London, East End. Spitalfields is formed around Commercial Street, London, Commercial Stre ...

.Moore, p.31. He was baptised on 5 March, the day after he was born, at St Dunstan's, Stepney

St Dunstan's, Stepney, is an Anglican church located in Stepney High Street, Stepney, in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. The church is believed to have been founded, or re-founded, in AD 952 by St Dunstan, the patron saint of bell ringers, ...

, suggesting a fear of infant mortality

Infant mortality is the death of an infant before the infant's first birthday. The occurrence of infant mortality in a population can be described by the infant mortality rate (IMR), which is the number of deaths of infants under one year of age ...

by his parents, perhaps because the newborn was weak or sickly. His parents named him after an older brother, John, who had died before Sheppard's birth. In life, he was better known as "Gentleman Jack" or "Jack the Lad". He had a second brother, Thomas, and a younger sister, Mary. Their father, a carpenter

Carpentry is a skilled trade and a craft in which the primary work performed is the cutting, shaping and installation of building materials during the construction of buildings, ships, timber bridges, concrete formwork, etc. Carpenter ...

, died while Sheppard was young, and his sister died two years later.

Unable to support her family without her husband's income, Sheppard's mother sent him to Mr Garrett's School, a

Unable to support her family without her husband's income, Sheppard's mother sent him to Mr Garrett's School, a workhouse

In Britain and Ireland, a workhouse (, lit. "poor-house") was a total institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. In Scotland, they were usually known as Scottish poorhouse, poorh ...

near St Helen's Bishopsgate

St Helen's Bishopsgate is an Anglican church in London. It is located in Great St Helen's, off Bishopsgate.

It is the largest surviving parish church in the City of London. Several notable figures are buried there, and it contains more monuments ...

, when he was six years old. Sheppard was sent out as a parish apprentice to a cane-chair maker, taking a settlement of 20 shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currency, currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 1 ...

s, but his new master soon died. He was sent out to a second cane-chair maker, but Sheppard was treated badly.Moore, p.38. Finally, when Sheppard was 10 years old, he went to work as a shop-boy for William Kneebone, a wool draper

Draper was originally a term for a retailer or wholesaler of cloth that was mainly for clothing. A draper may additionally operate as a cloth merchant or a haberdasher.

History

Drapers were an important trade guild during the medieval period ...

with a shop on the Strand

Strand or The Strand may refer to:

Topography

*The flat area of land bordering a body of water, a:

** Beach

** Shoreline

* Strand swamp, a type of swamp habitat in Florida

Places Africa

* Strand, Western Cape, a seaside town in South Africa

* ...

.Moore, p.33. Sheppard's mother had been working for Kneebone since her husband's death. Kneebone taught Sheppard to read and write and apprentice

Apprenticeship is a system for training a potential new practitioners of a Tradesman, trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study. Apprenticeships may also enable practitioners to gain a license to practice in ...

d him to a carpenter, Owen Wood, in Wych Street

Wych Street was in London where King, Melbourne and Australia Houses now stand on Aldwych. It ran west from the church of St Clement Danes on the Strand, London, Strand to meet the southern end of Drury Lane. It was demolished by the London Coun ...

, off Drury Lane

Drury Lane is a street on the boundary between the Covent Garden and Holborn areas of London, running between Aldwych and High Holborn. The northern part is in the borough of London Borough of Camden, Camden and the southern part in the City o ...

in Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist sit ...

. Sheppard signed his seven-year indenture

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects an agreement between two parties. Although the term is most familiarly used to refer to a labor contract between an employer and a laborer with an indentured servant status, historically indentures we ...

on 2 April 1717.

By 1722, Sheppard was showing great promise as a carpenter. Aged 20, he was a small man, only and lightly built, but deceptively strong. He had a pale face with large, dark eyes, a wide mouth and a quick smile. Despite a slight stutter

Stuttering, also known as stammering, is a speech disorder characterized externally by involuntary repetitions and prolongations of sounds, syllables, words, or phrases as well as involuntary silent pauses called blocks in which the person who ...

, his wit made him popular in the taverns of Drury Lane.Moore, p.96. He served five unblemished years of his apprenticeship but then began to become involved with crime.

Joseph Hayne, a button-moulder who owned a shop nearby, also managed a tavern

A tavern is a type of business where people gather to drink alcoholic beverages and be served food such as different types of roast meats and cheese, and (mostly historically) where travelers would receive lodging. An inn is a tavern that ...

named the Black Lion off Drury Lane, which he encouraged the local apprentices to frequent.Moore, p.98. The Black Lion was visited by criminals such as Joseph "Blueskin" Blake, Sheppard's future partner in crime, and self-proclaimed "Thief-Taker General" Jonathan Wild

Jonathan Wild, also spelled Wilde (1682 or 1683 – 24 May 1725), was an English thief-taker and a major figure in London's criminal underworld, notable for operating on both sides of the law, posing as a public-spirited vigilante entitled th ...

, secretly the boss of a criminal gang which operated across London and later Sheppard's implacable enemy.

According to Sheppard's autobiography, he had been an innocent until going to Hayne's tavern, but there began a preference for strong drink and the affections of Elizabeth Lyon, a prostitute

Prostitution is a type of sex work that involves engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, non-pe ...

also known as Edgworth Bess (or Edgeworth Bess) from her place of birth at Edgeworth

Edgeworth may refer to:

People

* Edgeworth (surname)

Places

* Edgeworth, Gloucestershire, England

* Edgeworth, New South Wales, Australia

* Edgeworth, Pennsylvania, USA

* Edgworth, a village in Lancashire, England

* Edgeworth Island, Nunavut ...

in Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a Historic counties of England, former county in South East England, now mainly within Greater London. Its boundaries largely followed three rivers: the River Thames, Thames in the south, the River Lea, Le ...

. In his ''History'', Defoe records that Bess was "a main lodestone in attracting of him up to this Eminence of Guilt".Defoe, ''History''. Such, Sheppard claimed, was the source of his later ruin. Peter Linebaugh

Peter Linebaugh is an American Marxist historian who specializes in British history, Irish history, labor history, and the history of the colonial Atlantic. He is a member of the Midnight Notes Collective.

Early life

Linebaugh was born in 194 ...

offers a more politicised version: that Sheppard's sudden transformation was a liberation from the dull drudgery of indentured labour and that he progressed from pious servitude to self-confident rebellion and Levelling

Levelling or leveling (American English; see spelling differences) is a branch of surveying, the object of which is to establish or verify or measure the height of specified points relative to a datum. It is widely used in geodesy and cartogra ...

.

Criminal career

Sheppard began habitually drinking and whoring. Inevitably, his carpentry suffered, and he became disobedient to his master. With Lyon's encouragement, Sheppard began criminal activity in order to augment his legitimate wages. His first recorded theft was in Spring 1723, when he engaged in pettyshoplifting

Shoplifting (also known as shop theft, shop fraud, retail theft, or retail fraud) is the theft of goods from a retail establishment during business hours. The terms ''shoplifting'' and ''shoplifter'' are not usually defined in law, and genera ...

, stealing two silver spoons while on an errand for his master to the Rummer Tavern in Charing Cross

Charing Cross ( ) is a junction in Westminster, London, England, where six routes meet. Since the early 19th century, Charing Cross has been the notional "centre of London" and became the point from which distances from London are measured. ...

. Sheppard's misdeeds were undetected, and he progressed to larger crimes, often stealing goods from the houses where he was working. Finally, he quit the employ of his master on 2 August 1723, with less than two years of his apprenticeship left,Moore, p.99. although he continued to work as a journeyman

A journeyman is a worker, skilled in a given building trade or craft, who has successfully completed an official apprenticeship qualification. Journeymen are considered competent and authorized to work in that field as a fully qualified employee ...

carpenter. He was not suspected of the crimes, and progressed to burglary

Burglary, also called breaking and entering (B&E) or housebreaking, is a property crime involving the illegal entry into a building or other area without permission, typically with the intention of committing a further criminal offence. Usually ...

, in company with criminals in Jonathan Wild's gang.

He relocated to Fulham

Fulham () is an area of the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham in West London, England, southwest of Charing Cross. It lies in a loop on the north bank of the River Thames, bordering Hammersmith, Kensington and Chelsea, London, Chelsea ...

, living as husband and wife with Lyon at Parsons Green

Parsons Green is a mainly residential district in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham. The Parsons Green (The green), Green itself, which is roughly triangular, is bounded on two of its three sides by the New King's Road section of th ...

, before relocating to Piccadilly

Piccadilly () is a road in the City of Westminster, London, England, to the south of Mayfair, between Hyde Park Corner in the west and Piccadilly Circus in the east. It is part of the A4 road (England), A4 road that connects central London to ...

. When Lyon was arrested and imprisoned at St Giles's Roundhouse, the beadle

A beadle, sometimes spelled bedel, is an official who may usher, keep order, make reports, and assist in religious functions; or a minor official who carries out various civil, educational or ceremonial duties on the manor.

The term has pre- ...

, a Mr Brown, refused to let Sheppard visit, so he broke in and took her away.

Arrested and escaped twice

Sheppard was first arrested after a burglary he committed with his brother, Tom, and his mistress, Lyon, inClare Market

Clare Market is a historic area in central London located within the parish of St Clement Danes to the west of Lincoln's Inn Fields, between the Strand and Drury Lane, with Vere Street adjoining its western side. It was named after the food m ...

on 5 February 1724. Tom, also a carpenter, had already been convicted once for stealing tools from his master the previous autumn and burned in the hand. Tom was arrested again on 24 April 1724. Afraid that he would be hanged this time, Tom informed on Jack, and a warrant was issued for Jack's arrest.

Jonathan Wild was aware of Sheppard's thefts, as Sheppard had fenced some stolen goods through one of Wild's men, William Field. Wild asked another of his men, James Sykes (known as "Hell and Fury") to challenge Sheppard to a game of skittles at Redgate's public house near Seven Dials.Moore, p.100. Sykes betrayed Sheppard to a Mr Price, a constable

A constable is a person holding a particular office, most commonly in law enforcement. The office of constable can vary significantly in different jurisdictions. ''Constable'' is commonly the rank of an officer within a police service. Other peo ...

from the parish of St Giles

Saint Giles (, , , , ; 650 - 710), also known as Giles the Hermit, was a hermit or monk active in the lower Rhône most likely in the 7th century. Revered as a saint, his cult became widely diffused but his hagiography is mostly legendary. A ...

, to gather the usual £40 reward for giving information resulting in the conviction of a felon

A felony is traditionally considered a crime of high seriousness, whereas a misdemeanor is regarded as less serious. The term "felony" originated from English common law (from the French medieval word "''félonie''") to describe an offense that ...

. The magistrate, Justice Parry, had Sheppard imprisoned overnight on the top floor of St Giles's Roundhouse pending further questioning, but Sheppard escaped within three hours by breaking through the timber ceiling and lowering himself to the ground with a rope fashioned from bedclothes.Moore, p.104. Still wearing irons, Sheppard coolly joined the crowd that had been attracted by the sounds of his breaking out. He distracted their attention by pointing to the shadows on the roof and shouting that he could see the escapee, and then swiftly departed.

On 19 May 1724, Sheppard was arrested for a second time, caught in the act of picking a pocket in Leicester Fields (near present-day Leicester Square

Leicester Square ( ) is a pedestrianised town square, square in the West End of London, England, and is the centre of London's entertainment district. It was laid out in 1670 as Leicester Fields, which was named after the recently built Leice ...

). He was detained overnight in St Ann's Roundhouse in Soho

SoHo, short for "South of Houston Street, Houston Street", is a neighborhood in Lower Manhattan, New York City. Since the 1970s, the neighborhood has been the location of many artists' lofts and art galleries, art installations such as The Wall ...

and visited there the next day by Lyon; she was recognised as his wife and locked in a cell with him. They appeared before Justice Walters, who sent them to the New Prison

The New Prison was a prison located in the Clerkenwell area of central London between c.1617 and 1877. The New Prison was used to house prisoners committed for examination before the police magistrates, for trial at the sessions, for want of bai ...

in Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell ( ) is an area of central London, England.

Clerkenwell was an Civil Parish#Ancient parishes, ancient parish from the medieval period onwards, and now forms the south-western part of the London Borough of Islington. The St James's C ...

, but they escaped from their cell, known as the Newgate Ward, within a matter of days. By 25 May, Whitsun

Whitsun (also Whitsunday or Whit Sunday) is the name used in Britain, and other countries among Anglicans and Methodists, for the Christian holy day of Pentecost. It falls on the seventh Sunday after Easter and commemorates the descent of the H ...

Monday, Sheppard and Lyon had filed through their manacles; they removed a bar from the window and used their knotted bed-clothes to descend to ground level. Finding themselves in the yard of the neighbouring Bridewell

Bridewell Palace in London was built as a residence of King Henry VIII and was one of his homes early in his reign for eight years. Given to the City of London Corporation by his son King Edward VI in 1553 as Bridewell Hospital for use as a ...

, they clambered over the 22-foot

The foot (: feet) is an anatomical structure found in many vertebrates. It is the terminal portion of a limb which bears weight and allows locomotion. In many animals with feet, the foot is an organ at the terminal part of the leg made up o ...

-high (6.7 m) prison gate to freedom. This feat was widely publicised, not least because Sheppard was only a small man, and Lyon was a large, buxom woman.Moore, p.105.

Third arrest, trial, and third escape

Sheppard's thieving abilities were admired by Jonathan Wild. Wild demanded that Sheppard surrender his stolen goods for Wild to fence, and so take the greater profits, but Sheppard refused. He began to work with Joseph "Blueskin" Blake, and they burgled Sheppard's former master, William Kneebone, on Sunday 12 July 1724. Wild could not permit Sheppard to continue outside his control and began to seek Sheppard's arrest.Moore, p.110. Unfortunately for Sheppard, his fence, William Field, was one of Wild's men. After Sheppard had a brief foray with Blueskin ashighwaymen

A highwayman was a robber who stole from travellers. This type of thief usually travelled and robbed by horse as compared to a footpad who travelled and robbed on foot; mounted highwaymen were widely considered to be socially superior to foo ...

on the Hampstead Road on Sunday 19 July and Monday 20 July, Field informed on Sheppard to Wild. Wild believed Lyon would know Sheppard's whereabouts, so he plied her with drinks at a brandy shop near Temple Bar until she betrayed him. Sheppard was arrested a third time at Blueskin's mother's brandy shop in Rosemary Lane, east of the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

(later renamed Royal Mint Street), on 23 July by Wild's henchman, Quilt Arnold.Moore, p.111.

Sheppard was imprisoned in Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey, just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, the pr ...

pending his trial at the next Assize

The assizes (), or courts of assize, were periodic courts held around England and Wales until 1972, when together with the quarter sessions they were abolished by the Courts Act 1971 and replaced by a single permanent Crown Court. The assizes ex ...

of ''oyer and terminer

In English law, oyer and terminer (; a partial translation of the Anglo-French , which literally means 'to hear and to determine') was one of the commissions by which a judge of assize sat. Apart from its Law French name, the commission was also ...

''. He was prosecuted on three charges of theft at the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

, but was acquitted on the first two due to lack of evidence. Kneebone, Wild and Field gave evidence against him on the third charge, the burglary of Kneebone's house. He was convicted on 12 August, the case "being plainly prov'd", and sentenced to death. On Monday 31 August, the very day when the death warrant

An execution warrant (also called a death warrant or a black warrant) is a writ that authorizes the execution of a condemned person.

United States

In the United States, either a judicial or executive official designated by law issues an ...

arrived from the court in Windsor

Windsor may refer to:

Places

*Detroit–Windsor, Michigan-Ontario, USA-Canada, North America; a cross-border metropolitan region

Australia New South Wales

*Windsor, New South Wales

** Municipality of Windsor, a former local government area Queen ...

setting Friday 4 September as the date for his execution, Sheppard escaped. Having loosened an iron bar in a window used when talking to visitors, he was visited by Lyon and Poll Maggott, who distracted the guards while he removed the bar (security was lax compared to that of later years; the guard-to-prisoner ratio at Newgate in 1724 was 1:90, and wives could stay overnight). His slight build enabled him to climb through the resulting gap in the grille, and he was smuggled out of Newgate in women's clothing that his visitors had brought him.Moore, p.206. He took a coach to Blackfriars Stairs, a boat up the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, s ...

to the horse ferry in Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

, near the warehouse where he hid his stolen goods, and completed his escape.

Fourth arrest and final escape

By this time, Sheppard was a hero to a segment of the population, being a

By this time, Sheppard was a hero to a segment of the population, being a cockney

Cockney is a dialect of the English language, mainly spoken in London and its environs, particularly by Londoners with working-class and lower middle class roots. The term ''Cockney'' is also used as a demonym for a person from the East End, ...

, non-violent, handsome and seemingly able to escape punishment for his crimes at will. He spent a few days out of London, visiting a friend's family in Chipping Warden

Chipping Warden is a village and former civil parish, now in the parish of Chipping Warden and Edgcote, in the West Northamptonshire district, in the county of Northamptonshire, England, about northeast of the Oxfordshire town of Banbury.

T ...

in Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire ( ; abbreviated Northants.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It is bordered by Leicestershire, Rutland and Lincolnshire to the north, Cambridgeshire to the east, Bedfordshi ...

, but was soon back in town.Moore, p.207. He evaded capture by Wild and his men but was arrested again on 9 September by a posse from Newgate as he hid on Finchley Common

Finchley Common was an area of land in Middlesex, north of London, and until 1816, the boundary between the parishes of Finchley, Friern Barnet and Hornsey.

History

Its use as a common is quite late. Rights to the common were claimed by the ...

,Moore, p.208. and returned to the condemned cell at Newgate. His fame had increased with each escape, and he was visited in prison by various people. His plans to escape during September were thwarted twice when the guards found files and other tools in his cell, and he was transferred to a strong-room in Newgate known as the "Castle", put in leg irons

Legcuffs are physical restraints used on the ankles of a person to allow walking only with a restricted stride and to prevent running and effective physical resistance. Frequently used alternative terms are leg cuffs, (leg/ankle) shackles, foo ...

, and chained to two metal staples in the floor to prevent further escape attempts. After demonstrating to his gaolers that these measures were insufficient, by showing them how he could use a small nail to unlock the horse padlock at will, he was bound more tightly and handcuffed

''Handcuffed'' is a 1929 American silent mystery film directed by Duke Worne and starring Virginia Brown Faire, Wheeler Oakman and Dean Jagger.

Synopsis

Gerald Morely's father is ruined in a stock fraud and commits suicide. When shortly afterwa ...

. In his ''History'', Defoe reports that Sheppard made light of his predicament, joking that "I am the Sheppard, and all the Gaolers in the Town are my Flock, and I cannot stir into the Country, but they are all at my Heels ''Baughing'' after me".

Meanwhile, "Blueskin" Blake was arrested by Wild and his men on Friday 9 October, and Tom, Jack's brother, was transported

''Transported'' is an Australian convict melodrama film directed by W. J. Lincoln.

It is considered a lost film.

Plot

In England, Jessie Grey is about to marry Leonard Lincoln but the evil Harold Hawk tries to force her to marry him and she ...

for robbery on Saturday 10 October 1724.Moore, p.158. New court sessions began on Wednesday 14 October, and Blueskin was tried on Thursday 15 October, with Field and Wild again giving evidence. Their accounts were not consistent with the evidence that they gave at Sheppard's trial, but Blueskin was convicted anyway. Enraged, Blueskin attacked Wild in the courtroom, slashing his throat with a pocket-knife and causing an uproar.Moore, p.159. Wild was lucky to survive, and his control of his criminal gang was weakened while he recuperated.

Taking advantage of the disturbance, which spread to Newgate Prison next door and continued into the night, Sheppard escaped for the fourth time. He unlocked his handcuffs and removed the chains. Still encumbered by his leg irons, he attempted to climb up the chimney, but his path was blocked by an iron bar set into the brickwork. He removed the bar and used it to break through the ceiling into the "Red Room" above the "Castle", a room which had last been used some seven years before to confine aristocratic Jacobite prisoners after the Battle of Preston. Still wearing his leg irons as night began, he then broke through six barred doors into the prison chapel, then to the roof of Newgate, above the ground. He went back down to his cell to get a blanket, then back to the roof of the prison, and used the blanket to reach the roof of an adjacent house, owned by William Bird, a turner. He broke into Bird's house, and went down the stairs and out into the street at around midnight without disturbing the occupants. Escaping through the streets to the north and west, Sheppard hid in a cowshed in "Tottenham" (near modern Tottenham Court Road

Tottenham Court Road (occasionally abbreviated as TCR) is a major road in Central London, almost entirely within the London Borough of Camden.

The road runs from Euston Road in the north to St Giles Circus in the south; Tottenham Court Road tu ...

). Spotted by the barn's owner, Sheppard told him that he had escaped from Bridewell Prison, having been imprisoned there for failing to provide for a (nonexistent) bastard son. His leg irons remained in place for several days until he persuaded a passing shoemaker to accept the considerable sum of 20 shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currency, currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 1 ...

s to bring a blacksmith's tools and help him remove them, telling him the same tale.Moore, p.162. His manacles and leg irons were later recovered in the rooms of Kate Cook, one of Sheppard's mistresses. This escape astonished everyone. Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; 1660 – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, merchant and spy. He is most famous for his novel ''Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its number of translati ...

, working as a journalist

A journalist is a person who gathers information in the form of text, audio or pictures, processes it into a newsworthy form and disseminates it to the public. This is called journalism.

Roles

Journalists can work in broadcast, print, advertis ...

, wrote an account for John Applebee, ''The History of the Remarkable Life of John Sheppard''. In his ''History'', Defoe reports the belief in Newgate that the Devil came in person to assist Sheppard's escape.

Final capture

Sheppard's final period of liberty lasted just two weeks. He disguised himself as a beggar and returned to the city. He broke into the Rawlins brothers'

Sheppard's final period of liberty lasted just two weeks. He disguised himself as a beggar and returned to the city. He broke into the Rawlins brothers' pawnbroker

A pawnbroker is an individual that offers secured loans to people, with items of personal property used as Collateral (finance), collateral. A pawnbrokering business is called a pawnshop, and while many items can be pawned, pawnshops typic ...

's shop in Drury Lane on the night of 29 October 1724, taking a black silk suit, a silver sword, rings, watches, a wig, and other items.Moore, p.164. He dressed himself as a dandy gentleman and used the proceeds to spend a day and the ensuing evening on the tiles with two mistresses. He was arrested a final time in the early morning on 1 November, drunk, "in a handsome Suit of Black, with a Diamond Ring and a carnelian

Carnelian (also spelled cornelian) is a brownish-red mineral commonly used as a semiprecious stone. Similar to carnelian is sard, which is generally harder and darker; the difference is not rigidly defined, and the two names are often used int ...

ring on his Finger, and a fine Light Tye Peruke".

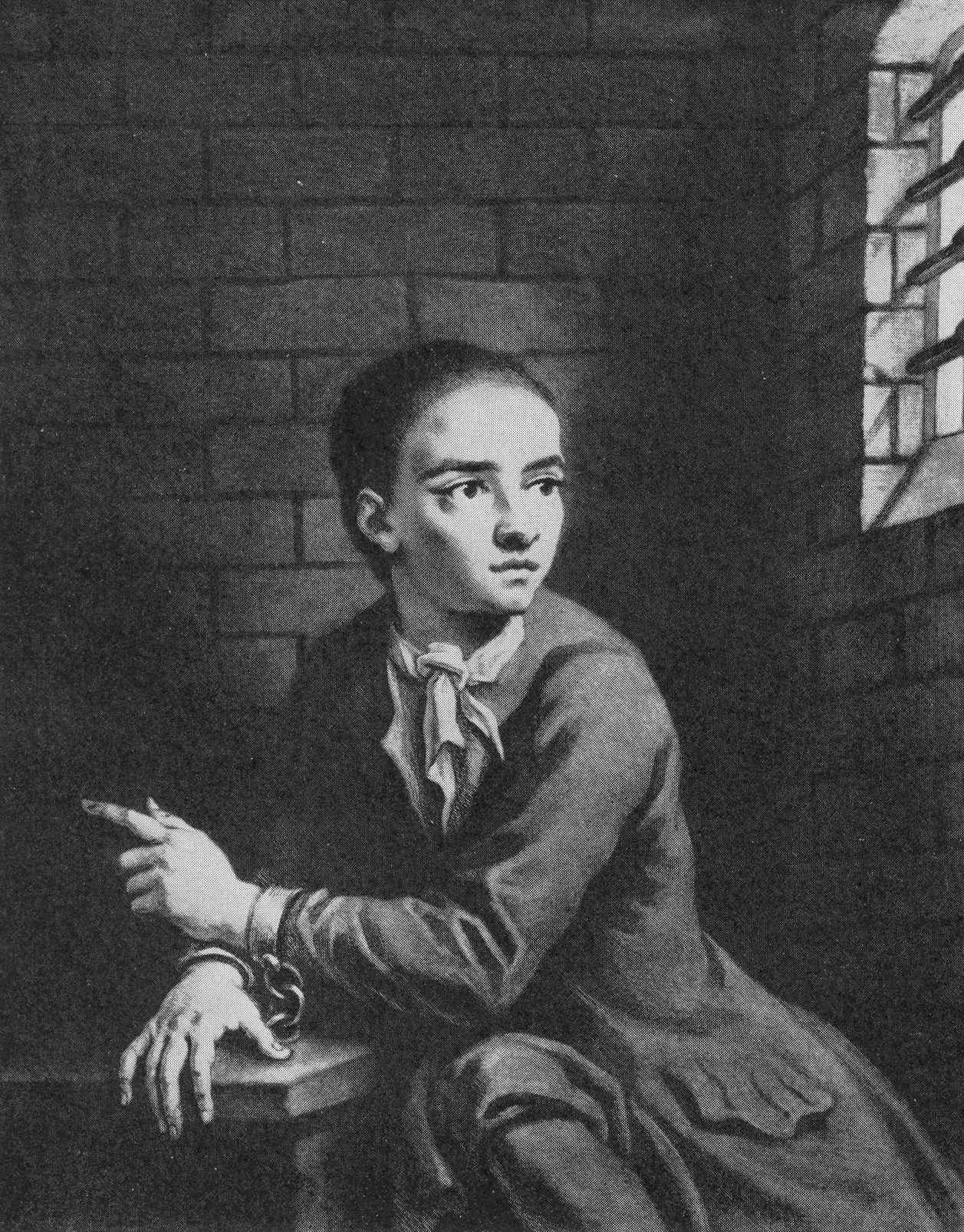

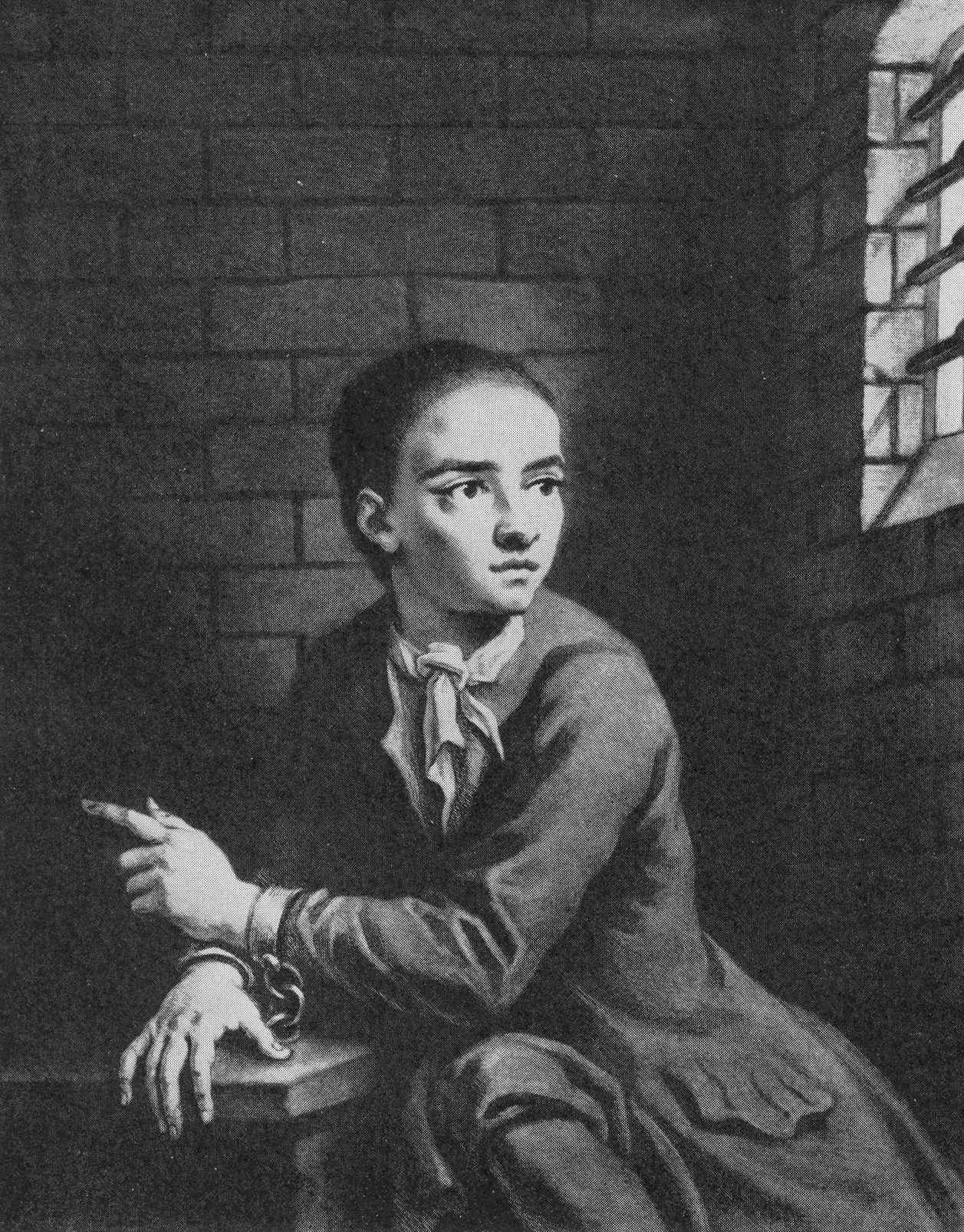

This time, Sheppard was placed in the Middle Stone Room, in the centre of Newgate next to the "Castle", where he could be observed at all times. He was also loaded with 300 pounds of iron weights. He was so celebrated that the gaolers charged high society visitors four shillings to see him, and the King's painter James Thornhill

Sir James Thornhill (25 July 1675 or 1676 – 4 May 1734) was an English painter of historical subjects working in the Italian baroque tradition. He was responsible for some large-scale schemes of murals, including the "Painted Hall" at the R ...

painted his portrait. Several prominent people sent a petition to King George I George I or 1 may refer to:

People

* Patriarch George I of Alexandria (fl. 621–631)

* George I of Constantinople (d. 686)

* George of Beltan (d. 790)

* George I of Abkhazia (ruled 872/3–878/9)

* George I of Georgia (d. 1027)

* Yuri Dolgoruk ...

, begging for his sentence of death to be commuted to transportation

Transport (in British English) or transportation (in American English) is the intentional Motion, movement of humans, animals, and cargo, goods from one location to another. Mode of transport, Modes of transport include aviation, air, land tr ...

. "The Concourse of People of tolerable Fashion to see him was exceeding Great, he was always Chearful and Pleasant to a Degree, as turning almost everything as was said onto a Jest and Banter." To a Reverend Wagstaffe who visited him, he said, according to Defoe, "One file's worth all the Bibles in the World".

Sheppard came before Mr Justice Powis in the Court of King's Bench

The Court of King's Bench, formally known as The Court of the King Before the King Himself, was a court of common law in the English legal system. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century from the '' curia regis'', the King's Bench initi ...

at Westminster Hall

Westminster Hall is a medieval great hall which is part of the Palace of Westminster in London, England. It was erected in 1097 for William II (William Rufus), at which point it was the largest hall in Europe. The building has had various functio ...

on 10 November. He was offered the chance to have his sentence reduced by informing on his associates, but he scorned the offer, and the death sentence was confirmed.Moore, p.168. The next day, Blueskin was hanged, and Sheppard was moved to the condemned cell.

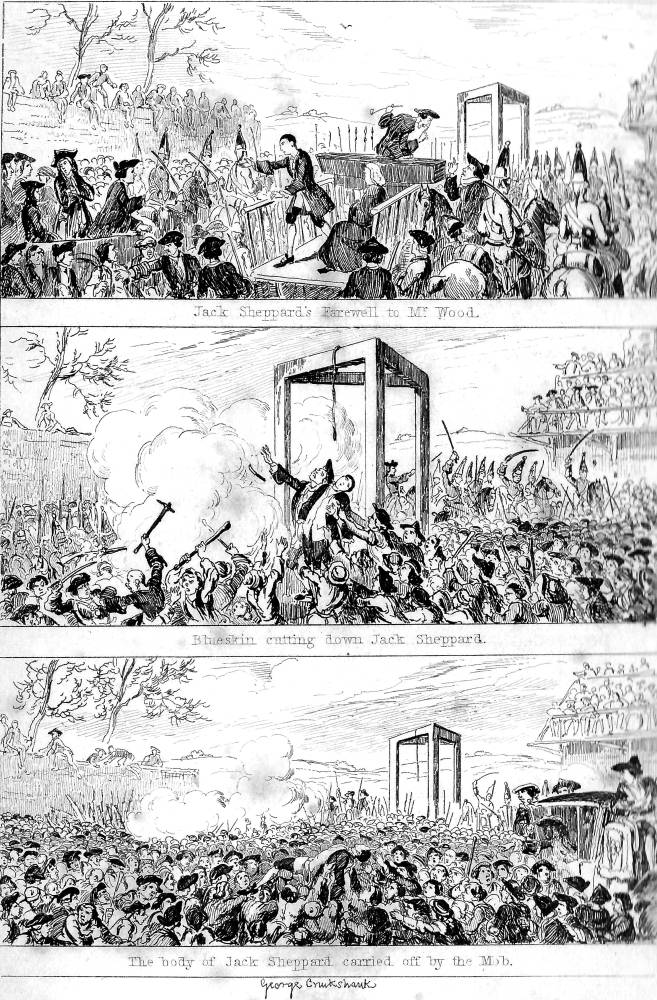

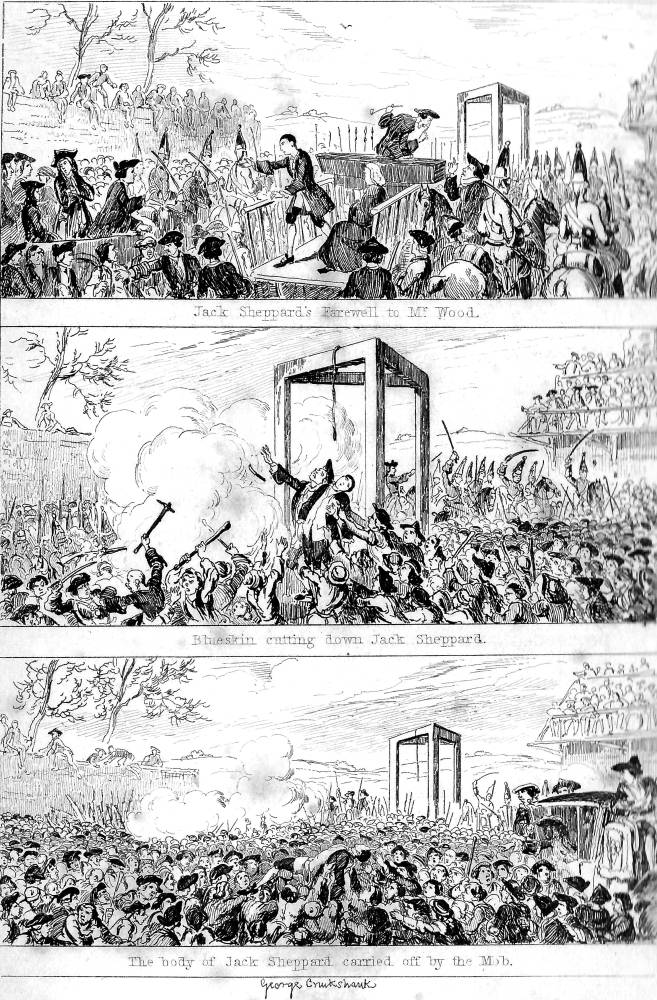

Execution

The next Monday, 16 November, Sheppard was taken to thegallows

A gallows (or less precisely scaffold) is a frame or elevated beam, typically wooden, from which objects can be suspended or "weighed". Gallows were thus widely used to suspend public weighing scales for large and heavy objects such as sa ...

at Tyburn

Tyburn was a Manorialism, manor (estate) in London, Middlesex, England, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone. Tyburn took its name from the Tyburn Brook, a tributary of the River Westbourne. The name Tyburn, from Teo Bourne ...

to be hanged

Hanging is killing a person by suspending them from the neck with a noose or ligature strangulation, ligature. Hanging has been a standard method of capital punishment since the Middle Ages, and has been the primary execution method in numerou ...

. He planned one more escape, but his pen-knife, intended to cut the ropes binding him on the way to the gallows, was found by a prison warder shortly before he left Newgate for the last time.Moore, p.219.

A joyous procession passed through the streets of London, with Sheppard's cart drawn along Holborn

Holborn ( or ), an area in central London, covers the south-eastern part of the London Borough of Camden and a part (St Andrew Holborn (parish), St Andrew Holborn Below the Bars) of the Wards of the City of London, Ward of Farringdon Without i ...

and Oxford Street

Oxford Street is a major road in the City of Westminster in the West End of London, running between Marble Arch and Tottenham Court Road via Oxford Circus. It marks the notional boundary between the areas of Fitzrovia and Marylebone to t ...

accompanied by a mounted City Marshal

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used for elevated of ...

and liveried Javelin Men. The occasion was as much as anything a celebration of Sheppard's life, attended by crowds of as many as 200,000 people (one third of London's population). The procession halted at the City of Oxford tavern on Oxford Street, where Sheppard drank a pint of sack

A sack usually refers to a rectangular-shaped bag.

Sack may also refer to:

Bags

* Flour sack

* Gunny sack

* Hacky sack, sport

* Money sack

* Paper sack

* Sleeping bag

* Stuff sack

* Knapsack

Other uses

* Bed, a slang term

* Sack (band), ...

.Moore, p.222. A carnival atmosphere pervaded Tyburn, where his "official" autobiography, published by Applebee and probably ghostwritten by Defoe, was on sale. Sheppard handed "a paper to someone as he mounted the scaffold", perhaps as a symbolic endorsement of the account in the "Narrative". His slight build had aided his previous prison escapes, but it caused him a slow death by strangulation

Strangling or strangulation is compression of the neck that may lead to unconsciousness or death by causing an increasingly hypoxic state in the brain by restricting the flow of oxygen through the trachea. Fatal strangulation typically occurs ...

from the hangman's noose

''Hangman's Noose'' (French: ''Le collier de chanvre'') is a 1940 French mystery film directed by Léon Mathot and starring Jacqueline Delubac, André Luguet and Annie Vernay.Oscherwitz & Higgins p.279 It is based on the 1932 novel ''Rope to Spar ...

. After hanging for the prescribed 15 minutes, his body was cut down. The crowd pressed forward to stop his body from being removed, fearing dissection

Dissection (from Latin ' "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause of ...

; their actions inadvertently prevented Sheppard's friends from implementing a plan to take his body to a doctor in an attempt to revive him. His badly mauled remains were recovered later and buried in the churchyard of St Martin-in-the-Fields

St Martin-in-the-Fields is a Church of England parish church at the north-east corner of Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, London. Dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours, there has been a church on the site since at least the medieval pe ...

that evening.Moore, p.225.

Legacy

There was a spectacular public reaction to Sheppard's deeds, which were cited favourably as an example in newspapers. Pamphlets, broadsheets, and ballads were all devoted to his amazing experiences, real and fictional, and his story was adapted for the stage almost immediately. ''Harlequin Sheppard'', a

There was a spectacular public reaction to Sheppard's deeds, which were cited favourably as an example in newspapers. Pamphlets, broadsheets, and ballads were all devoted to his amazing experiences, real and fictional, and his story was adapted for the stage almost immediately. ''Harlequin Sheppard'', a pantomime

Pantomime (; informally panto) is a type of musical comedy stage production designed for family entertainment, generally combining gender-crossing actors and topical humour with a story more or less based on a well-known fairy tale, fable or ...

by one John Thurmond

John Thurmond (died 1727) was a British stage actor. To distinguish him from his son, also an actor named John, he is sometimes called John Thurmond the Elder.

His earliest known stage performance was in 1695, when he played in ''Cyrus the Great' ...

(subtitled "A night scene in grotesque characters"), opened at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, commonly known as Drury Lane, is a West End theatre and listed building, Grade I listed building in Covent Garden, London, England. The building faces Catherine Street (earlier named Bridges or Brydges Street) an ...

, on Saturday 28 November, only two weeks after Sheppard's hanging. In a famous contemporary sermon, a London preacher drew on Sheppard's popular escapes as a way of holding his congregation's attention:

The account of his life remained well-known through the ''Newgate Calendar

''The Newgate Calendar'', subtitled ''The Malefactors' Bloody Register'', was a popular collection of moralising stories about sin, crime, and criminals who commit them in England in the 18th and 19th centuries. Originally a monthly bulletin of ...

'', and a three-act farce was published but never produced, but, mixed with songs, it became '' The Quaker's Opera'', later performed at Bartholomew Fair

The Bartholomew Fair was one of London's pre-eminent summer charter fairs. A charter for the fair was granted by King Henry I to fund the Priory of St Bartholomew in 1133. It took place each year on 24 August (St Bartholomew's Day) within the p ...

. An imagined dialogue between Jack Sheppard and Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

was published in the ''British Journal

The ''British Journal'' was an English newspaper published from 22 September 1722 until 13 January 1728. The paper was then published as the ''British Journal or The Censor'' from 20 January 1728 until 23 November 1730, and then as the ''Britis ...

'' on 4 December 1724, in which Sheppard favourably compares his virtues and exploits to those of Caesar.

Perhaps the most prominent play based on Sheppard's life is John Gay

John Gay (30 June 1685 – 4 December 1732) was an English poet and dramatist and member of the Scriblerus Club. He is best remembered for ''The Beggar's Opera'' (1728), a ballad opera. The characters, including Captain Macheath and Polly Peach ...

's ''The Beggar's Opera

''The Beggar's Opera'' is a ballad opera in three acts written in 1728 by John Gay with music arranged by Johann Christoph Pepusch. It is one of the watershed plays in Augustan drama and is the only example of the once thriving genre of sati ...

'' (1728). Sheppard was the inspiration for the character Captain Macheath

Captain Macheath is a fictional character who appears both in John Gay's '' The Beggar's Opera'' (1728), its sequel '' Polly'' (1777), and 150 years later in Bertolt Brecht's ''The Threepenny Opera'' (1928).

Origins

Macheath made his first appe ...

; his nemesis, Peachum, is based on Jonathan Wild.Moore, p. 227. The play was spectacularly popular, restoring the fortune that Gay had lost in the South Sea Bubble

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

, and was produced regularly for more than 100 years. An unperformed but published play ''The Prison-Breaker'' was turned into ''The Quaker's Opera'' (in imitation of ''The Beggar's Opera'') and performed at Bartholomew Fair

The Bartholomew Fair was one of London's pre-eminent summer charter fairs. A charter for the fair was granted by King Henry I to fund the Priory of St Bartholomew in 1133. It took place each year on 24 August (St Bartholomew's Day) within the p ...

in 1725 and 1728. Two centuries later ''The Beggar's Opera'' was the basis for ''The Threepenny Opera

''The Threepenny Opera'' ( ) is a 1928 German "play with music" by Bertolt Brecht, adapted from a translation by Elisabeth Hauptmann of John Gay's 18th-century English ballad opera, '' The Beggar's Opera'', and four ballads by François V ...

'' of Bertolt Brecht

Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht (10 February 1898 – 14 August 1956), known as Bertolt Brecht and Bert Brecht, was a German theatre practitioner, playwright, and poet. Coming of age during the Weimar Republic, he had his first successes as a p ...

and Kurt Weill

Kurt Julian Weill (; ; March 2, 1900April 3, 1950) was a German-born American composer active from the 1920s in his native country, and in his later years in the United States. He was a leading composer for the stage who was best known for hi ...

(1928).

Sheppard's tale may have been an inspiration for William Hogarth

William Hogarth (; 10 November 1697 – 26 October 1764) was an English painter, engraving, engraver, pictorial social satire, satirist, editorial cartoonist and occasional writer on art. His work ranges from Realism (visual arts), realistic p ...

's 1747 series of 12 engraving

Engraving is the practice of incising a design on a hard, usually flat surface by cutting grooves into it with a Burin (engraving), burin. The result may be a decorated object in itself, as when silver, gold, steel, or Glass engraving, glass ar ...

s, ''Industry and Idleness

''Industry and Idleness'' is the title of a series of 12 plot-linked engravings created by the English artist William Hogarth in 1747, intending to illustrate to working children the possible rewards of hard work and diligent application and t ...

'', which shows the parallel habituation of an apprentice, Tom Idle, to crime, resulting in his being hung, beside the fortunes of his fellow apprentice, Francis Goodchild, who marries his master's daughter and takes over his business, becoming wealthy as a result, eventually emulating Dick Whittington

Richard Whittington ( March 1423) of the parish of St Michael Paternoster Royal,Will of Richard Whittington: " I leave to my executors named below the entire tenement in which I live in the parish of St. Michael Paternoster Royal, Londo/ ...

to become Lord Mayor of London

The Lord Mayor of London is the Mayors in England, mayor of the City of London, England, and the Leader of the council, leader of the City of London Corporation. Within the City, the Lord Mayor is accorded Order of precedence, precedence over a ...

.Moore, p. 231.

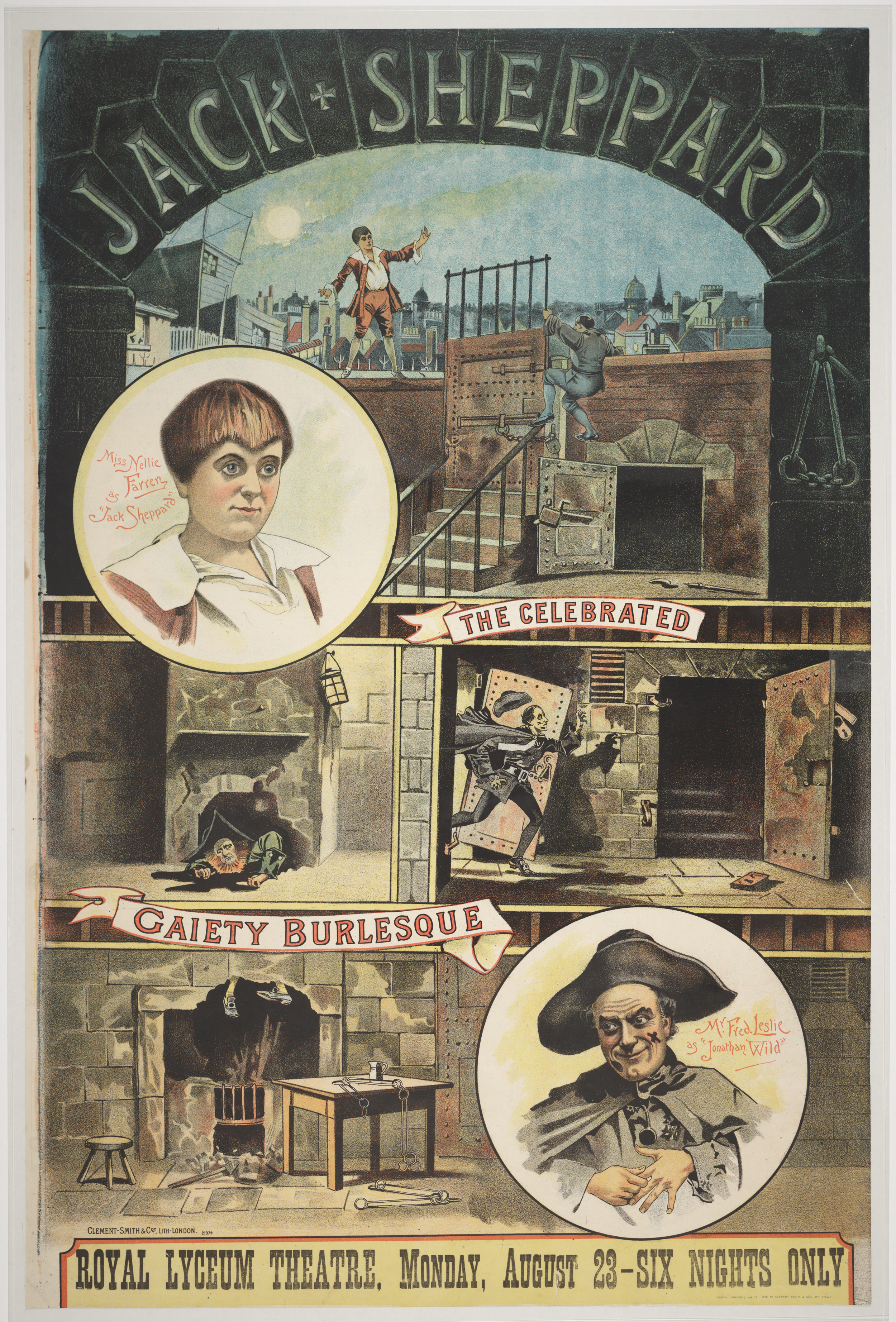

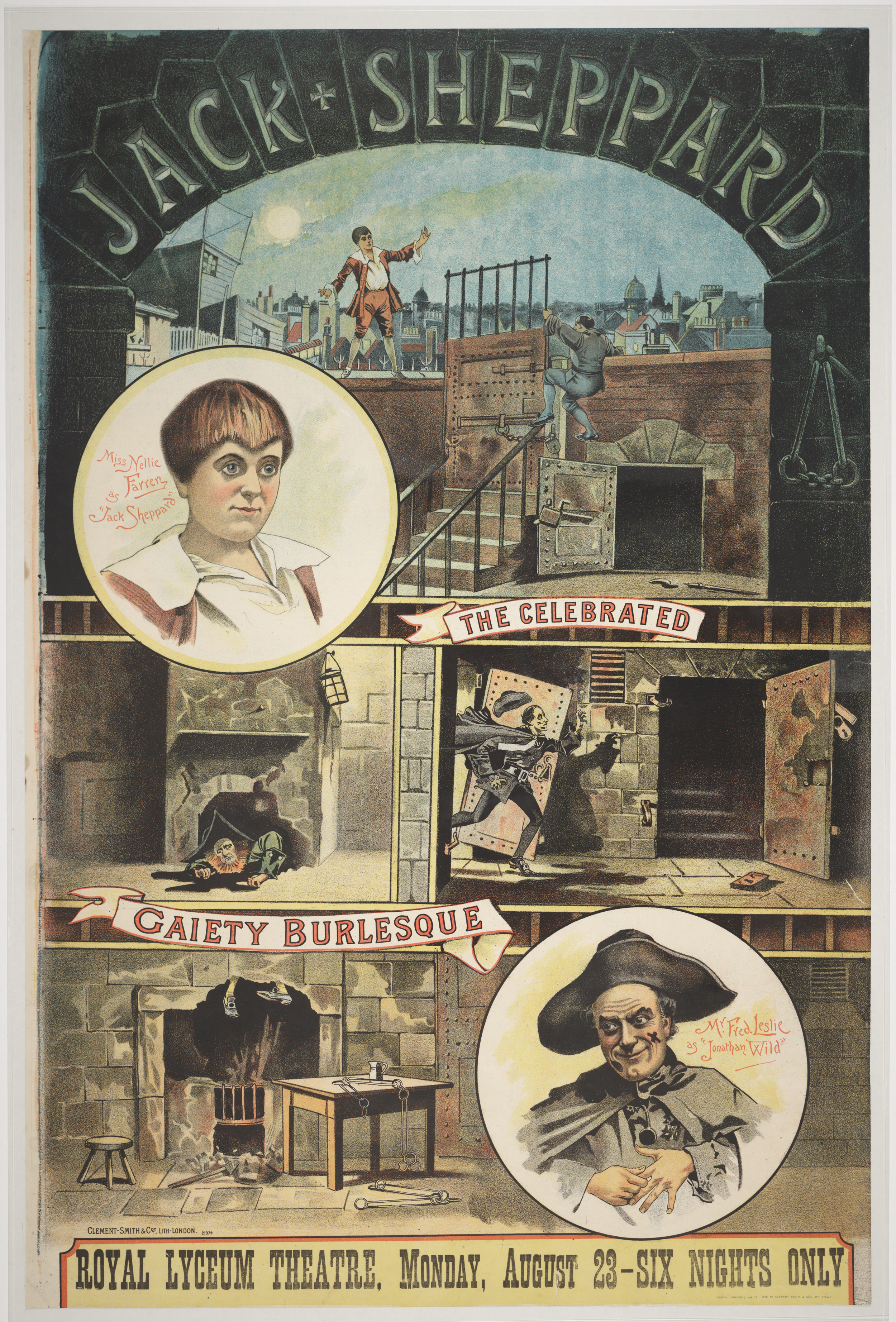

Sheppard's tale was revived during the first half of the 19th century. A

Sheppard's tale was revived during the first half of the 19th century. A melodrama

A melodrama is a Drama, dramatic work in which plot, typically sensationalized for a strong emotional appeal, takes precedence over detailed characterization. Melodrama is "an exaggerated version of drama". Melodramas typically concentrate on ...

, ''Jack Sheppard, The Housebreaker, or London in 1724'', by W. T. Moncrieff was published in 1825. More successful was William Harrison Ainsworth

William Harrison Ainsworth (4 February 18053 January 1882) was an English historical novelist born at King Street in Manchester. He trained as a lawyer, but the legal profession held no attraction for him. While completing his legal studies in ...

's third novel, entitled ''Jack Sheppard'', which was published originally in ''Bentley's Miscellany

''Bentley's Miscellany'' was an English literary magazine started by Richard Bentley. It was published between 1836 and 1868.

Contributors

Already a successful publisher of novels, Bentley began the journal in 1836 and invited Charles Dicken ...

'' from January 1839 with illustrations by George Cruikshank

George Cruikshank or Cruickshank ( ; 27 September 1792 – 1 February 1878) was a British caricaturist and book illustrator, praised as the "modern William Hogarth, Hogarth" during his life. His book illustrations for his friend Charles Dicken ...

, overlapping with the final episodes of Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

' ''Oliver Twist

''Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress'', is the second novel by English author Charles Dickens. It was originally published as a serial from 1837 to 1839 and as a three-volume book in 1838. The story follows the titular orphan, who, ...

''. An archetypal Newgate novel The Newgate novels (or Old Bailey novels) were novels published in England from the late 1820s until the 1840s that glamorised the lives of the criminals they portrayed. Most drew their inspiration from the '' Newgate Calendar'', a biography of famo ...

, it generally remains close to the facts of Sheppard's life, but portrays him as a daring hero. Like Hogarth's prints, the novel pairs the increasing involvement of the "idle" apprentice with crime with the fortunes of a typical melodramatic character, Thames Darrell, a foundling of aristocratic birth who defeats his evil uncle to recover his fortune. Cruikshank's images perfectly complemented Ainsworth's tale—William Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray ( ; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was an English novelist and illustrator. He is known for his satirical works, particularly his 1847–1848 novel '' Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portrait of British society, and t ...

wrote that "... Mr Cruickshank really created the tale, and that Mr Ainsworth, as it were, only put words to it." The novel quickly became very popular: it was published in book form later that year, before the serialised version was completed, and even outsold early editions of ''Oliver Twist''. Ainsworth's novel was adapted into a successful play by John Buckstone

John Baldwin Buckstone (14 September 1802 – 31 October 1879) was an English actor, playwright and comedian who wrote 150 plays, the first of which was produced in 1826.

He starred as a comic actor during much of his career for various periods ...

in October 1839 at the Adelphi Theatre

The Adelphi Theatre is a West End theatre, located on the Strand in the City of Westminster, central London. The present building is the fourth on the site. The theatre has specialised in comedy and musical theatre, and today it is a receiv ...

featuring (strangely enough) Mary Anne Keeley

Mary Anne Keeley, ''née'' Goward (22 November 1805 – 12 March 1899) was an English actress and actor-manager.

Life

Mary Ann Goward was born at Ipswich, her father was a brazier and tinman. Her sister Sarah Judith Goward was the mother of Lyd ...

; indeed, it seems likely that Cruikshank's illustrations were deliberately created in a form that were informed by, and would be easy to repeat as, tableaux on stage. It has been described as the "exemplary climax" of "the pictorial novel dramatized pictorially".

The story generated a type of cultural mania, embellished by pamphlets, prints, cartoons, plays and souvenirs, not repeated until George du Maurier

George Louis Palmella Busson du Maurier (6 March 1834 – 8 October 1896) was a Franco-British cartoonist and writer known for work in ''Punch (magazine), Punch'' and a Gothic fiction, Gothic novel ''Trilby (novel), Trilby'', featuring the char ...

's novel ''Trilby

A trilby is a narrow-brimmed type of hat. The trilby was once viewed as the rich man's favored hat; it is sometimes called the "brown trilby" in UK, BritainBernhard Roetzel, Roetzel, Bernhard (1999). ''Gentleman's Guide to Grooming and Style''. B ...

'' in 1895. By early 1840, a cant CANT may refer to:

*CANT, a solo project from Grizzly Bear bass guitarist and producer, Chris Taylor.

*Cantieri Aeronautici e Navali Triestini

CANT (''Cantieri Aeronautici e Navali Triestini'', the Trieste Shipbuilding and Naval Aeronautics; also ...

song from Buckstone's play "Nix My Dolly, Pals, Fake Away" was reported to be "deafening us in the streets". Public alarm at the possibility that young people would emulate Sheppard's behaviour caused the Lord Chamberlain

The Lord Chamberlain of the Household is the most senior officer of the Royal Households of the United Kingdom, Royal Household of the United Kingdom, supervising the departments which support and provide advice to the Monarchy of the United Ki ...

to ban, at least in London, the licensing

A license (American English) or licence ( Commonwealth English) is an official permission or permit to do, use, or own something (as well as the document of that permission or permit).

A license is granted by a party (licensor) to another par ...

of any plays with "Jack Sheppard" in the title for forty years. The fear may not have been entirely unfounded: Courvousier, the valet of Lord William Russell

Lord William Russell (20 August 1767 – 5 May 1840) was a member of the British aristocratic Russell family and longtime Member of Parliament. He did little to attract public attention after the end of his political career until, in 1840, he wa ...

, said in one of his several confessions that the book had inspired him to murder his master.Moore, p. 229. Frank and Jesse James

Jesse Woodson James (September 5, 1847April 3, 1882) was an American outlaw, Bank robbery, bank and Train robbery, train robber, guerrilla and leader of the James–Younger Gang. Raised in the "Little Dixie (Missouri), Little Dixie" area of M ...

wrote letters to the ''Kansas City Star'' signed "Jack Sheppard". Nevertheless, burlesques

A burlesque is a literary, dramatic or musical work intended to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works, or by ludicrous treatment of their subjects.

of the story were written after the ban was ended, including a popular Gaiety Theatre, London

The Gaiety Theatre was a West End theatre in London, located on Aldwych at the eastern end of the Strand, London, Strand. The theatre was first established as the Strand Musick Hall in 1864 on the former site of the Lyceum Theatre, London, Lyc ...

, piece called ''Little Jack Sheppard

''Little Jack Sheppard'' is a Victorian burlesque, burlesque melodrama written by Henry Pottinger Stephens and William Yardley (cricketer), William Yardley, with music by Meyer Lutz, with songs contributed by Florian Pascal,Florian Pascal was a p ...

'' (1886) by Henry Pottinger Stephens

Henry Pottinger Stephens (c. 1851 – 11 February 1903), was an English dramatist and journalist.

After beginning his career writing for newspapers, Stephens began writing Victorian burlesques in the 1870s in collaboration with F. C. Burnan ...

and William Yardley, which featured Nellie Farren

Ellen "Nellie" Farren (16 April 1848 – 28 April 1904"Death of Nellie Far ...

as Jack.Sugden

The Sheppard story has been revived three times as movies the 20th century: ''The Hairbreadth Escape of Jack Sheppard'' (1900), ''Jack Sheppard'' (1923), and ''Where's Jack?

''Where's Jack?'' (also known as ''Run, Rebel, Run'') is a 1969 British adventure film directed by James Clavell and starring Stanley Baker and Tommy Steele. It was written by Rafe Newhouse and David Newhouse and produced by Baker for his com ...

'' (1969), a British historical drama directed by James Clavell

James Clavell (born Charles Edmund Dumaresq Clavell; 10 October 1921 – 7 September 1994) was a British and American writer, screenwriter, director, and World War II veteran and prisoner of war. Clavell is best known for his ''Asian Saga'' nov ...

with Tommy Steele

Sir Thomas Hicks (born 17 December 1936), known professionally as Tommy Steele, is an English entertainer, regarded as Britain's first teen idol and rock and roll star.

After being discovered at the 2i's Coffee Bar in Soho, London, Steele recor ...

in the title role. Jake Arnott

Jake Arnott (born 11 March 1961) is a British novelist and dramatist, author of ''The Long Firm'' (1999) and six other novels.

Life

Arnott was born in Buckinghamshire, England. Having left Aylesbury Grammar School at the age of 17, he had va ...

features him in his 2017 novel ''The Fatal Tree''.

In 1971 British popular music group Chicory Tip

Chicory Tip are an English pop group, formed in 1967 in Maidstone, Kent.

The band originally comprised vocalist Peter Hewson (born 1 September 1945, in Gillingham); guitarist Richard "Rick" Foster (born 7 July 1946); bass guitarist Barry Mayg ...

paid tribute to Sheppard in "Don't Hang Jack", the B-side

The A-side and B-side are the two sides of phonograph record, vinyl records and Compact cassette, cassettes, and the terms have often been printed on the labels of two-sided music recordings. The A-side of a Single (music), single usually ...

to " I Love Onions". The song, apparently sung from the viewpoint of a witness in the courtroom

A courtroom is the enclosed space in which courts of law are held in front of a judge. A number of courtrooms, which may also be known as "courts", may be housed in a courthouse. In recent years, courtrooms have been equipped with audiovisual ...

, describes Jack's daring exploits as a thief, and futilely begs the judge to spare Sheppard because he was loved by the women of the town, and idolised by the lads who "made him their king".

In Jordy Rosenberg's 2018 novel ''Confessions of the Fox

''Confessions of the Fox'' is a novel by American writer and academic Jordy Rosenberg, first published in 2018. It re-imagines the lives of Jack Sheppard, eighteenth-century English thief and jail-breaker, and his lover Edgeworth Bess.

Plot

Th ...

'', the Sheppard story was recontextualised as a queer narrative: a 21st-century academic discovers a manuscript containing Sheppard's "confessions", which tell the story of his childhood and his love affair with Edgeworth Bess, and reveals that he was a transgender man.

The reasons for the lasting legacy of Sheppard's exploits in the popular imagination have been addressed by Peter Linebaugh, who suggests that Sheppard's legend was based on the prospect of excarceration, of escape from what Michel Foucault

Paul-Michel Foucault ( , ; ; 15 October 192625 June 1984) was a French History of ideas, historian of ideas and Philosophy, philosopher who was also an author, Literary criticism, literary critic, Activism, political activist, and teacher. Fo ...

in '' Folie et déraison'' termed the ''grand renfermement'' (''Great Confinement''), in which "unreasonable" members of the population were locked away and institutionalised.Linebaugh describes excarceration as "the growing propensity, skill and success of London working people in escaping from the newly created institutions that were designed to discipline people by closing them in." ''The London Hanged'', pp. 7–42. Linebaugh further says that the laws applied to Sheppard and similar working class criminals were a means of disciplining a potentially rebellious multitude into accepting increasingly harsh property laws. Another nineteenth-century opinion of the Jack Sheppard phenomenon was offered by Charles Mackay

Charles MacKay (born May 1950, Albuquerque, New Mexico) is an American arts administrator, known for leadership roles at the Santa Fe Opera, Opera Theatre of Saint Louis, and Spoleto Festival USA/ Festival of Two Worlds.

Early experience

MacKay i ...

in ''Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds

A memoir (; , ) is any nonfiction narrative writing based on the author's personal memories. The assertions made in the work are thus understood to be factual. While memoir has historically been defined as a subcategory of biography or autobio ...

'':

Notes

References

* Anon. ''The Bloody Register'' vol. II London, 1764. * Buckley, Matthew. "Sensations of Celebrity: Jack Sheppard and the Mass Audience", ''Victorian Studies'', Volume 44, Number 3, Spring 2002, pp. 423–463 * Defoe, Daniel''The History of the Remarkable Life of John Sheppard''

London: 1724. Retrieved 5 February 2007. * Howson, Gerald. ''Thief-Taker General: Jonathan Wild and the Emergence of Crime and Corruption as a Way of Life in Eighteenth-Century England.'' New Brunswick, NJ and Oxford, UK: 1970. * Linebaugh, Peter. ''The London Hanged: Crime and Civil Society in the Eighteenth Century.'' Verso, 2003, * Lynch, Jack (editor)

Retrieved 5 February 2007. * Mackay, Charles. ''Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds''. Wordsworth Editions, (1841) 1999 edition. . * Moore, Lucy. ''The Thieves' Opera.'' Viking, 1997, * Mullan, John, and Christopher Reid. ''Eighteenth-Century Popular Culture: A Selection''. Oxford University Press, 2000. . * Norton, Rictor. ''Early Eighteenth-Century Newspaper Reports: A Sourcebook''

Retrieved 5 February 2007. * Sugden, Philip. "John Sheppard" in Matthew, H.C.G. and Brian Harrison, eds. ''

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

''The'' is a grammatical Article (grammar), article in English language, English, denoting nouns that are already or about to be mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the ...

.'' vol. 50, 261–263. London: OUP

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the publishing house of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world. Its first book was printed in Oxford in 1478, with the Press officially granted the legal right to print books ...

, 2004.

Further reading

* ''Proceedings from the Old Bailey''Ordinary's Account of 4 September 1724

Reference (docket) t17240812-52. * Anon (often attributed to Defoe). ''A Narrative of All the Robberies, Escapes, Etc. of John Sheppard''. 1724. * Bleackley, Horace, ''Trial of Jack Sheppard''. Wm Gaunt & Sons, (1933) 1996 edition. . * G.E. ''Authentick Memoirs of the Life and Surprising Adventures of John Sheppard by Way of Familiar Letters from a Gentleman in Town.'' 1724. * Gatrell, V.A. ''The Hanging Tree: Execution and the English People 1770–1868''. Oxford University Press, 1996. . * Hibbert, Christopher. ''The Road to Tyburn: The story of Jack Sheppard and the Eighteenth-Century London Underworld''. New York: The World Publishing Company, 1957. (2001 Penguin reprint: ) * Linnane, Fergus. ''The Encyclopedia of London Crime''. Sutton Publishing, 2003. . * Meisel, Martin. (1983) ''Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-Century England''. Princeton. * Rawlings, Philip. ''Drunks, Whores, and Idle Apprentices: Criminal Biographies of the Eighteenth Century''. Routledge (UK), 1992. . * Rogers, Pat. ''Daniel Defoe: The Critical Heritage''. Routledge (UK), 1995. .

External links

Jack Sheppard

from the

Newgate Calendar

''The Newgate Calendar'', subtitled ''The Malefactors' Bloody Register'', was a popular collection of moralising stories about sin, crime, and criminals who commit them in England in the 18th and 19th centuries. Originally a monthly bulletin of ...

, including contemporary sermon. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

Project Gutenberg etext

of

William Harrison Ainsworth

William Harrison Ainsworth (4 February 18053 January 1882) was an English historical novelist born at King Street in Manchester. He trained as a lawyer, but the legal profession held no attraction for him. While completing his legal studies in ...

's novel.

''The Thief-Taker Hangings: How Daniel Defoe, Jonathan Wild, and Jack Sheppard Captivated London and Created the Celebrity Criminal'' by Aaron Skirboll

{{DEFAULTSORT:Sheppard, Jack 1702 births 1724 deaths 1723 crimes in Europe Crime in London British people executed for robbery English criminals English escapees Escapees from England and Wales detention Executed people from London Fugitives People from Spitalfields People executed at Tyburn People executed by England and Wales by hanging People executed by the Kingdom of Great Britain