The Johns Hopkins University (often abbreviated as Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a

private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* "In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorded ...

research university

A research university or a research-intensive university is a university that is committed to research as a central part of its mission. They are "the key sites of Knowledge production modes, knowledge production", along with "intergenerational ...

in

Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

, Maryland, United States. Founded in 1876 based on the European research institution model, Johns Hopkins is considered to be the first research university in the U.S.

The university was named for its first benefactor, the American entrepreneur and

Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

philanthropist

Johns Hopkins

Johns Hopkins (May 19, 1795 – December 24, 1873) was an American merchant, investor, and philanthropist. Born on a plantation, he left his home to start a career at the age of 17, and settled in Baltimore, Maryland, where he remained for mos ...

.

Hopkins's $7 million bequest (equivalent to $ in ) to establish the university was the largest

philanthropic

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives for the public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private good, focusing on material ...

gift in U.S. history up to that time.

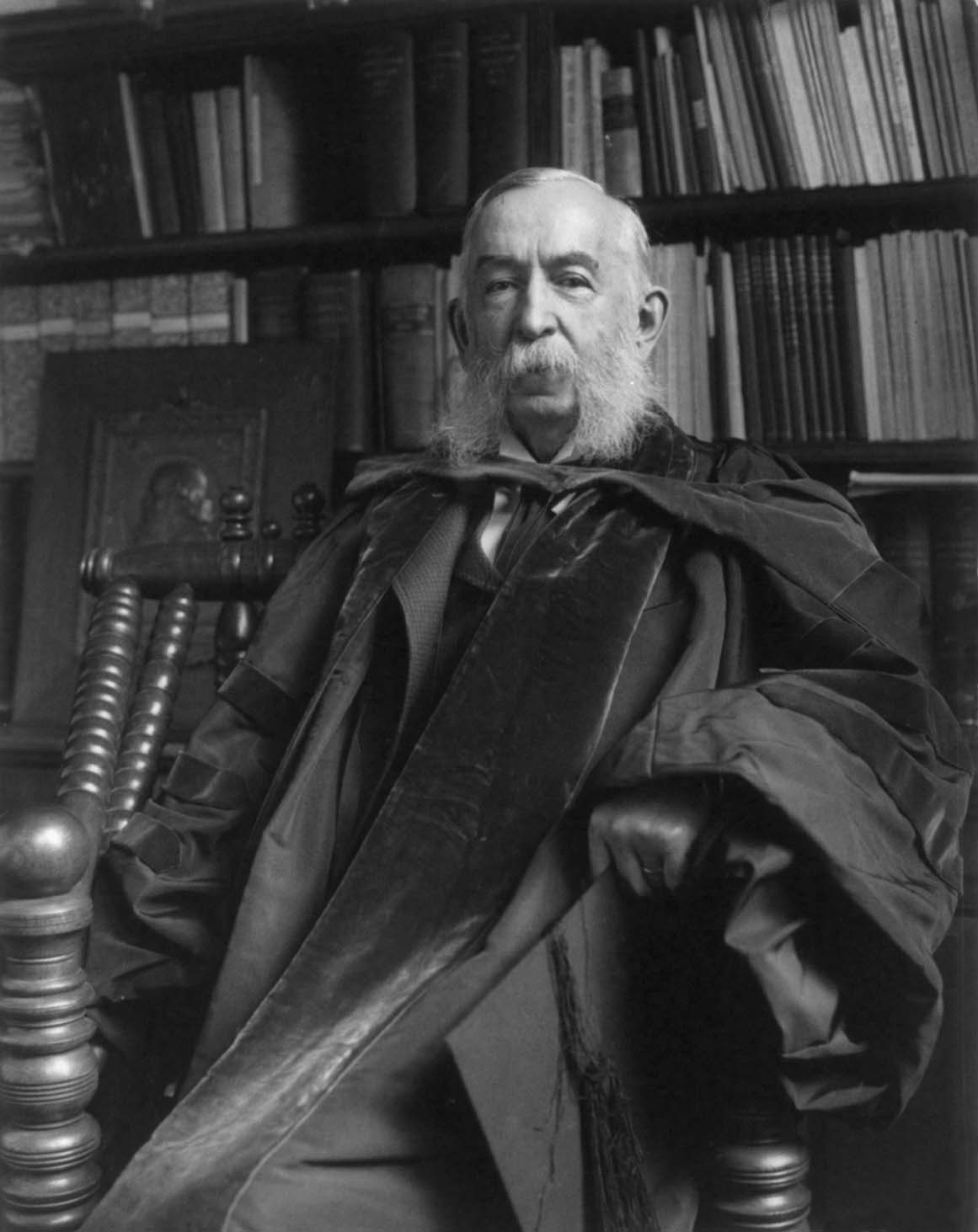

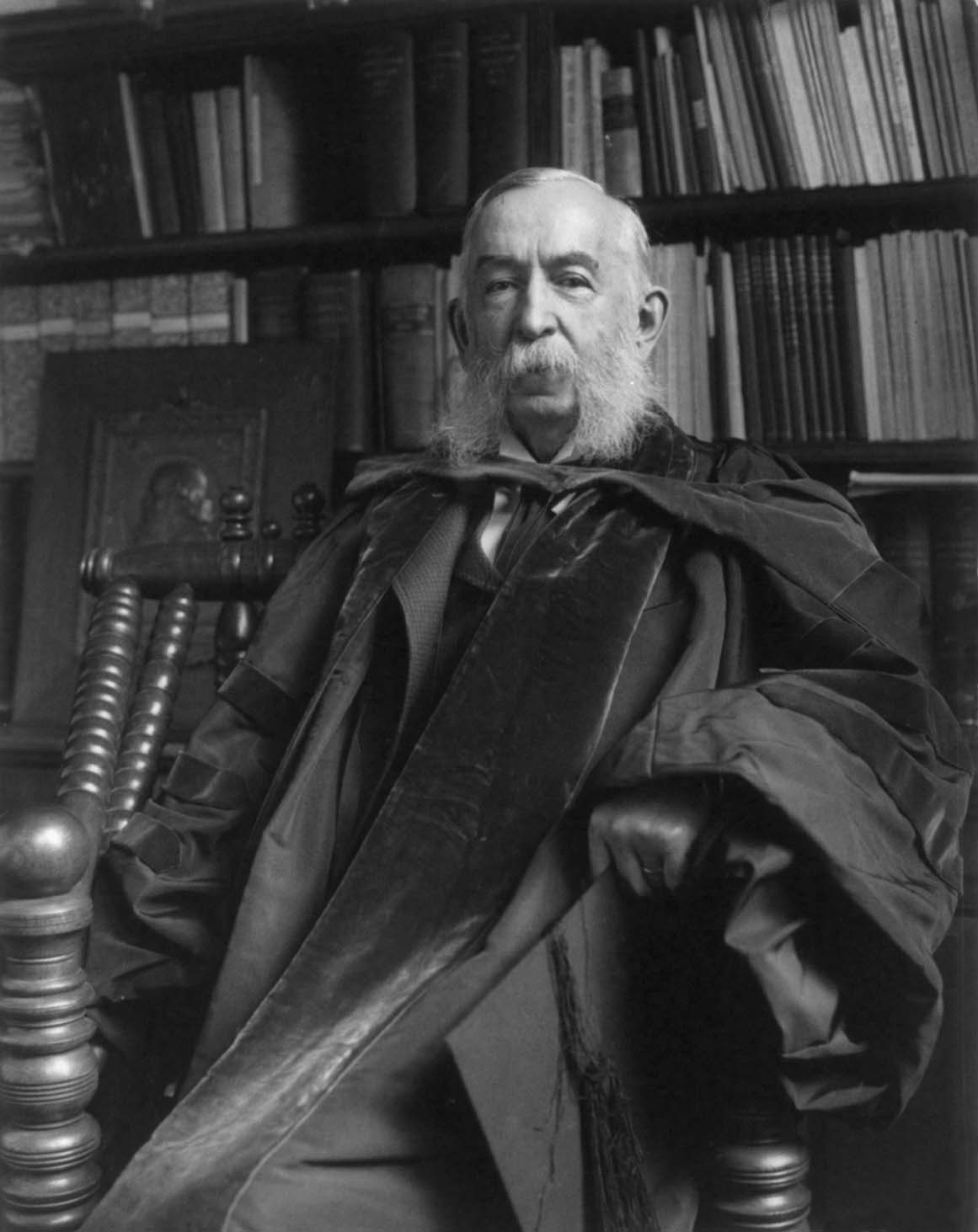

Daniel Coit Gilman

Daniel Coit Gilman (; July 6, 1831 – October 13, 1908) was an American educator and academic. Gilman was instrumental in founding the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale College, and subsequently served as the second president of the University ...

, who was inaugurated as

Johns Hopkins's first president on February 22, 1876,

led the university to revolutionize higher education in the U.S. by integrating teaching and research.

In 1900, Johns Hopkins became a founding member of the

Association of American Universities

The Association of American Universities (AAU) is an organization of predominantly American research universities devoted to maintaining a strong system of academic research and education. Founded in 1900, it consists of 69 public and private ...

. The university has led all

U.S. universities in annual research and development expenditures for over four consecutive decades.

The

School of Medicine

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, professional school, or forms a part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, ...

, established in 1893, has achieved international recognition for its pioneering biomedical research and is widely considered to be a top U.S. medical school.

The university consists of ten academic divisions mostly divided among four campuses in Baltimore, with some graduate campuses in

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

,

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, and

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

The university's two undergraduate divisions, the

Zanvyl Krieger School of Arts and Sciences

The Krieger School of Arts and Sciences is the college of arts and sciences at the Johns Hopkins University, a private university in Baltimore, Maryland.

The school is based on the university's Homewood campus and, together with the Whiting Sc ...

and the

Whiting School of Engineering

The Whiting School of Engineering is the engineering school of the Johns Hopkins University, a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland.

History

The engineering department at Johns Hopkins was originally created in 1913 as an educatio ...

, are located on the

Homewood campus

The Homewood Campus is the main academic and administrative center of the Johns Hopkins University. It is located at 3400 North Charles Street in Baltimore, Maryland. It houses the two major undergraduate schools: the Zanvyl Krieger School of Art ...

adjacent to Baltimore's

Charles Village

Charles Village is a neighborhood located in the north-central area of Baltimore, Maryland, USA. It is a diverse, eclectic, international, largely middle-class area with many single-family homes that is in proximity to many of Baltimore's cultu ...

neighborhood.

The

School of Medicine

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, professional school, or forms a part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, ...

,

School of Nursing

Nurse education consists of the theoretical and practical training provided to nurses with the purpose to prepare them for their duties as nursing care professionals. This education is provided to student nurses by experienced nurses and other me ...

, and

Bloomberg School of Public Health

The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health is the public health graduate school of Johns Hopkins University, a private research university primarily based in Baltimore, Maryland.

It was founded as the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene ...

are located on the medical campus in East Baltimore, alongside the

Johns Hopkins Hospital

Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) is the teaching hospital and biomedical research facility of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1889, Johns Hopkins Hospital and its school of medicine are considered to be the foundin ...

.

The university also consists of the

Peabody Institute

The Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University is a Private university, private music and dance music school, conservatory and College-preparatory school, preparatory school in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1857, it became affiliat ...

in Baltimore's

Mount Vernon

Mount Vernon is the former residence and plantation of George Washington, a Founding Father, commander of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War, and the first president of the United States, and his wife, Martha. An American landmar ...

neighborhood,

Applied Physics Laboratory

The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (or simply Applied Physics Laboratory, or APL) is a not-for-profit university-affiliated research center (UARC) in Howard County, Maryland. It is affiliated with Johns Hopkins University ...

in

Howard County,

School of Advanced International Studies

The School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) is a graduate school of Johns Hopkins University based in Washington, D.C. The school also maintains campuses in Bologna, Italy and Nanjing, China.

The school is devoted to the study of int ...

,

School of Education

In the United States and Canada, a school of education (or college of education; ed school) is a division within a university that is devoted to scholarship in the field of education, which is an interdisciplinary branch of the social sciences e ...

, and

Carey Business School

The Johns Hopkins Carey Business School is the graduate business school of Johns Hopkins University, a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. It was established in 2007 and offers full-time and part-time programs leading to the M ...

.

Founded in 1883, the

Blue Jays men's lacrosse team, which is an affiliate member in the

Big Ten Conference

The Big Ten Conference (stylized B1G, formerly the Western Conference and the Big Nine Conference, among others) is a collegiate List of NCAA conferences, athletic conference in the United States. Founded as the Intercollegiate Conference of Fa ...

, has won 44 national titles.

The university's other sports teams compete in

Division III In sport, the Third Division, also called Division 3, Division Three, or Division III, is often the third-highest division of a league, and will often have promotion and relegation with divisions above and below.

Association football

*Belgian Third ...

of the

NCAA

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) is a nonprofit organization that regulates College athletics in the United States, student athletics among about 1,100 schools in the United States, and Simon Fraser University, 1 in Canada. ...

, where they are members of the

Centennial Conference

The Centennial Conference is an intercollegiate athletic conference which competes in the NCAA's Division III. Chartered member teams are located in Maryland and Pennsylvania; associate members are also located in New York and Virginia.

Ele ...

.

History

Philanthropic beginnings and foundation

On his death in 1873,

Johns Hopkins

Johns Hopkins (May 19, 1795 – December 24, 1873) was an American merchant, investor, and philanthropist. Born on a plantation, he left his home to start a career at the age of 17, and settled in Baltimore, Maryland, where he remained for mos ...

, a

Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

entrepreneur and childless bachelor, bequeathed $7 million (equivalent to $ in ) to fund a hospital and university in

Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

.

At the time, this donation, generated primarily from the

Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the oldest railroads in North America, oldest railroad in the United States and the first steam engine, steam-operated common carrier. Construction of the line began in 1828, and it operated as B&O from 1830 ...

,

was the largest philanthropic gift in the history of the United States,

and endowment was then the largest in America.

Until 2020, Hopkins was assumed to be a fervent

abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

, until research done by the school into his

United States Census

The United States census (plural censuses or census) is a census that is legally mandated by the Constitution of the United States. It takes place every ten years. The first census after the American Revolution was taken in 1790 United States ce ...

records revealed he claimed to own at least five household slaves in the 1840 and 1850 decennial censuses.

The first name of philanthropist Johns Hopkins comes from the surname of his great-grandmother, Margaret Johns, who married Gerard Hopkins.

They named their son Johns Hopkins, who named his own son Samuel Hopkins. Samuel named one of his sons for his father, and that son became the university's benefactor.

Milton Eisenhower, a former university president, once spoke at a convention in

Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, second-most populous city in Pennsylvania (after Philadelphia) and the List of Un ...

where the

master of ceremonies introduced him as "President of ''John'' Hopkins". Eisenhower retorted that he was "glad to be here in ''Pitt''burgh".

The original board opted for an entirely novel university model dedicated to the discovery of knowledge at an advanced level, extending that of contemporary Germany.

[ Building on the ]Humboldtian model of higher education

The Humboldtian model of higher education (German: ''Humboldtsches Bildungsideal'') or just Humboldt's ideal is a concept of higher education, academic education that emerged in the early 19th century whose core idea is a Holism, holistic combina ...

, the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

education model of Wilhelm von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Christian Karl Ferdinand von Humboldt (22 June 1767 – 8 April 1835) was a German philosopher, linguist, government functionary, diplomat, and founder of the Humboldt University of Berlin. In 1949, the university was named aft ...

, it became dedicated to research. It was especially Heidelberg University

Heidelberg University, officially the Ruprecht Karl University of Heidelberg (; ), is a public research university in Heidelberg, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. Founded in 1386 on instruction of Pope Urban VI, Heidelberg is Germany's oldest unive ...

and its long academic research history on which the new institution tried to model itself.

19th century

The trustees worked alongside four notable university presidents,

The trustees worked alongside four notable university presidents, Charles William Eliot

Charles William Eliot (March 20, 1834 – August 22, 1926) was an American academic who was president of Harvard University from 1869 to 1909, the longest term of any Harvard president. A member of the prominent Eliot family (America), Eliot fam ...

of Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

, Andrew D. White of Cornell University

Cornell University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university based in Ithaca, New York, United States. The university was co-founded by American philanthropist Ezra Cornell and historian and educator Andrew Dickson W ...

, Noah Porter

Noah Thomas Porter III (December 14, 1811 – March 4, 1892)''Obituary Record of Graduates of Yale University'', Yale University, 1891-2, New Haven, pp. 82-83. was an American Congregational minister, academic, philosopher, author, lexicographer ...

of Yale College

Yale College is the undergraduate college of Yale University. Founded in 1701, it is the original school of the university. Although other Yale schools were founded as early as 1810, all of Yale was officially known as Yale College until 1887, ...

, and James B. Angell of University of Michigan

The University of Michigan (U-M, U of M, or Michigan) is a public university, public research university in Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest institution of higher education in the state. The University of Mi ...

. They each supported Daniel Coit Gilman

Daniel Coit Gilman (; July 6, 1831 – October 13, 1908) was an American educator and academic. Gilman was instrumental in founding the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale College, and subsequently served as the second president of the University ...

to lead the new university and he became the university's first president.Yale

Yale University is a private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, and one of the nine colonial colleges ch ...

-educated scholar, had been serving as president of the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

prior to this appointment.Daniel Coit Gilman

Daniel Coit Gilman (; July 6, 1831 – October 13, 1908) was an American educator and academic. Gilman was instrumental in founding the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale College, and subsequently served as the second president of the University ...

visited University of Freiburg

The University of Freiburg (colloquially ), officially the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg (), is a public university, public research university located in Freiburg im Breisgau, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. The university was founded in 1 ...

and other German universities.

Gilman launched what many at the time considered an audacious and unprecedented academic experiment to merge teaching and research. He dismissed the idea that the two were mutually exclusive: "The best teachers are usually those who are free, competent and willing to make original researches in the library and the laboratory," he stated. To implement his plan, Gilman recruited internationally known researchers including the mathematician James Joseph Sylvester

James Joseph Sylvester (3 September 1814 – 15 March 1897) was an English mathematician. He made fundamental contributions to matrix theory, invariant theory, number theory, partition theory, and combinatorics. He played a leadership ...

; the biologist H. Newell Martin

Henry Newell Martin, FRS (1 July 1848 – 27 October 1896) was a British physiologist and vivisection activist.

Biography

He was born in Newry, County Down, the son of Henry Martin, a Congregational minister. He was educated at University Co ...

; the physicist Henry Augustus Rowland

Henry Augustus Rowland (November 27, 1848 – April 16, 1901) was an American physicist and Johns Hopkins educator. Between 1899 and 1901 he served as the first president of the American Physical Society. He is remembered for the high qualit ...

, the first president of the American Physical Society

The American Physical Society (APS) is a not-for-profit membership organization of professionals in physics and related disciplines, comprising nearly fifty divisions, sections, and other units. Its mission is the advancement and diffusion of ...

, the classical scholars

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek and Roman literature and their original languages, ...

Basil Gildersleeve

Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve (October 23, 1831January 9, 1924) was an American classical scholar. An author of numerous works, and founding editor of the ''American Journal of Philology'', he has been credited with contributions to the syntax of Gr ...

, and Charles D. Morris;Ira Remsen

Ira Remsen (February 10, 1846 – March 4, 1927) was an American chemist who introduced organic chemistry research and education in the United States along the lines of German universities where he received his early training. He was the first pr ...

, who became the second president of the university in 1901.

Gilman focused on the expansion of graduate education and support of faculty research. The new university fused advanced scholarship with such professional schools as medicine and engineering. Hopkins became the national trendsetter in doctoral

A doctorate (from Latin ''doctor'', meaning "teacher") or doctoral degree is a postgraduate academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism '' licentia docendi'' ("licence to teach ...

programs and the host for numerous scholarly journals and associations. The Johns Hopkins University Press

Johns Hopkins University Press (also referred to as JHU Press or JHUP) is the publishing division of Johns Hopkins University. It was founded in 1878 and is the oldest continuously running university press in the United States. The press publi ...

, founded in 1878, is the oldest American university press

A university press is an academic publishing house specializing in monographs and scholarly journals. They are often an integral component of a large research university. They publish work that has been reviewed by scholars in the field. They pro ...

in continuous operation.

With the completion of Johns Hopkins Hospital

Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) is the teaching hospital and biomedical research facility of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1889, Johns Hopkins Hospital and its school of medicine are considered to be the foundin ...

in 1889 and the medical school

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, professional school, or forms a part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, ...

in 1893, the university's research-focused mode of instruction soon began attracting world-renowned faculty members who would become major figures in the emerging field of academic medicine, including William Osler

Sir William Osler, 1st Baronet, (; July 12, 1849 – December 29, 1919) was a Canadian physician and one of the "Big Four" founding professors of Johns Hopkins Hospital. Osler created the first Residency (medicine), residency program for speci ...

, William Halsted

William Stewart Halsted, M.D. (September 23, 1852 – September 7, 1922) was an American surgeon who emphasized strict aseptic technique during surgical procedures, was an early champion of newly discovered anesthetics, and introduced sever ...

, Howard Kelly, and William Welch William Welch may refer to:

* William C. Welch (born 1977), American professional wrestler for the CZW

* William Welch (cricketer, born 1907) (1907–1983), Australian cricketer

* William Welch (cricketer, born 1911) (1911–1940), Australian cricke ...

. During this period the university further made history by becoming the first medical school to admit women on an equal basis with men and to require a Bachelor's degree

A bachelor's degree (from Medieval Latin ''baccalaureus'') or baccalaureate (from Modern Latin ''baccalaureatus'') is an undergraduate degree awarded by colleges and universities upon completion of a course of study lasting three to six years ...

, based on the efforts of Mary E. Garrett, who had endowed the school at Gilman's request. The school of medicine

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, professional school, or forms a part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, ...

was America's first coeducational, graduate-level medical school, and became a prototype for academic medicine that emphasized bedside learning, research projects, and laboratory training.

In his will and in his instructions to the trustees of the university and the hospital, Hopkins requested that both institutions be built upon the vast grounds of his Baltimore estate, Clifton. When Gilman assumed the presidency, he decided that it would be best to use the university's endowment for recruiting faculty and students, deciding to, as it has been paraphrased, "build men, not buildings." In his will Hopkins stipulated that none of his endowment should be used for construction; only interest on the principal could be used for this purpose. Unfortunately, stocks in The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the oldest railroads in North America, oldest railroad in the United States and the first steam engine, steam-operated common carrier. Construction of the line began in 1828, and it operated as B&O from 1830 ...

, which would have generated most of the interest, became virtually worthless soon after Hopkins's death. The university's first home was thus in Downtown Baltimore, delaying plans to site the university in Clifton.

20th century

In the early 20th century, the university outgrew its buildings and the trustees began to search for a new home. Developing Clifton for the university was too costly, and of the estate had to be sold to the city as public park. A solution was achieved by a team of prominent locals who acquired the estate in north Baltimore known as the Homewood Estate. On February 22, 1902, this land was formally transferred to the university. The flagship building, Gilman Hall, was completed in 1915. The School of Engineering

Engineering education is the activity of teaching knowledge and principles to the professional development, professional practice of engineering. It includes an initial education (Diploma in Engineering, Dip.Eng.)and Bachelor of Engineering, ( ...

relocated in Fall of 1914 and the Zanvyl Krieger School of Arts and Sciences

The Krieger School of Arts and Sciences is the college of arts and sciences at the Johns Hopkins University, a private university in Baltimore, Maryland.

The school is based on the university's Homewood campus and, together with the Whiting Sc ...

followed in 1916. These decades saw the ceding of lands by the university for the public Wyman Park and Wyman Park Dell and the Baltimore Museum of Art

The Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) in Baltimore, Maryland, is an art museum that was founded in 1914. The BMA's collection of 95,000 objects encompasses more than 1,000 works by Henri Matisse anchored by the Cone Collection of modern art, ...

, coalescing in the contemporary area of .Carrollton, Maryland

Carrollton is a locality in eastern Carroll County, Maryland, United States.

It is not to be confused with Carrollton Manor in Frederick County, from which Charles Carroll of Carrollton, a prominent signer of the Declaration of Independence, ...

, a planter and signer of the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

, to his son Charles Carroll Jr. The original structure, the 1801 Homewood House

The Homewood Museum is a historical museum located on the Johns Hopkins University campus in Baltimore, Maryland. It was listed as a National Historic Landmark in 1971, noted as a family home of Maryland's Carroll family. It, along with Evergree ...

, still stands and serves as an on-campus museum.Collegiate Gothic

Collegiate Gothic is an architectural style subgenre of Gothic Revival architecture, popular in the late-19th and early-20th centuries for college and high school buildings in the United States and Canada, and to a certain extent Europ ...

style of other historic American universities.continuing education

Continuing education is the education undertaken after initial education for either personal or professional reasons. The term is used mainly in the United States and Canada.

Recognized forms of post-secondary learning activities within the d ...

programs and in 1916 it founded the nation's first school of public health.

Since the 1910s, Johns Hopkins University has famously been a "fertile cradle" to Arthur Lovejoy

Arthur Oncken Lovejoy (October 10, 1873 – December 30, 1962) was an American philosopher and intellectual historian, who founded the discipline known as the history of ideas with his book ''The Great Chain of Being'' (1936), on the topic ...

's history of ideas

Intellectual history (also the history of ideas) is the study of the history of human thought and of intellectuals, people who conceptualize, discuss, write about, and concern themselves with ideas. The investigative premise of intellectual hist ...

.School of Advanced International Studies

The School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) is a graduate school of Johns Hopkins University based in Washington, D.C. The school also maintains campuses in Bologna, Italy and Nanjing, China.

The school is devoted to the study of int ...

in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, and the Peabody Institute

The Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University is a Private university, private music and dance music school, conservatory and College-preparatory school, preparatory school in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1857, it became affiliat ...

in Baltimore were incorporated into the university.

21st century

The early decades of the 21st century saw expansion across the university's institutions in both physical and population sizes. Notably, a planned 88-acre expansion to the medical campus began in 2013.Homewood campus

The Homewood Campus is the main academic and administrative center of the Johns Hopkins University. It is located at 3400 North Charles Street in Baltimore, Maryland. It houses the two major undergraduate schools: the Zanvyl Krieger School of Art ...

has included a new biomedical engineering

Biomedical engineering (BME) or medical engineering is the application of engineering principles and design concepts to medicine and biology for healthcare applications (e.g., diagnostic or therapeutic purposes). BME also integrates the logica ...

building in the Johns Hopkins University Department of Biomedical Engineering, a new library, a new biology wing, an extensive renovation of the flagship Gilman Hall, and the reconstruction of the main university entrance.Johns Hopkins School of Education

The Johns Hopkins School of Education is the school of education of Johns Hopkins University, a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Established as a separate school in 2007, its origins can be traced back to the 190 ...

and the Carey Business School

The Johns Hopkins Carey Business School is the graduate business school of Johns Hopkins University, a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. It was established in 2007 and offers full-time and part-time programs leading to the M ...

. On November 18, 2018, it was announced that

On November 18, 2018, it was announced that Michael Bloomberg

Michael Rubens Bloomberg (born February 14, 1942) is an American businessman and politician. He is the majority owner and co-founder of Bloomberg L.P., and was its CEO from 1981 to 2001 and again from 2014 to 2023. He served as the 108th mayo ...

would make a donation to his alma mater of $1.8 billion, marking the largest private donation in modern history to an institution of higher education

Tertiary education (higher education, or post-secondary education) is the educational level following the completion of secondary education.

The World Bank defines tertiary education as including universities, colleges, and vocational schools ...

and bringing Bloomberg's total contribution to the school in excess of $3.3 billion. Bloomberg's $1.8 billion gift allows the school to practice need-blind admission

Need-blind admission in the United States refers to a College admissions in the United States, college admission policy that does not take into account an applicant's financial status when deciding whether to accept them. This approach typically re ...

and meet the full financial need of admitted students.

In January 2019, the university announced an agreement to purchase the Newseum

The Newseum (April 18, 1997–March 3, 2002 and April 11, 2008–December 31, 2019) was an American museum located first in Rosslyn, Virginia, and later at 555 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, in Washington, D.C., dedicated to news and journalism that ...

, located at 555 Pennsylvania Ave. NW, in the heart of Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, with plans to locate all of its Washington, D.C.–based graduate programs there. In an interview with ''The Atlantic

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher based in Washington, D.C. It features articles on politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 185 ...

'', the president of Johns Hopkins stated that, "the purchase is an opportunity to position the university, literally, to better contribute its expertise to national- and international-policy discussions."

In late 2019, the university's Coronavirus Research Center began tracking worldwide cases of the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic (also known as the coronavirus pandemic and COVID pandemic), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), began with an disease outbreak, outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, in December ...

by compiling data from hundreds of sources around the world.

Establishment of the Johns Hopkins Police Department

In February 2019, Johns Hopkins University requested permission from the Maryland General Assembly to create a private police force to patrol in and around the three Baltimore campuses, a move that was immediately opposed by several neighboring communities,Catherine Pugh

Catherine Elizabeth Pugh (born March 10, 1950) is an American former politician who served as the 51st mayor of Baltimore, Maryland's largest city, from 2016 to 2019. She resigned from office amid a scandal that eventually led to criminal charge ...

's re-election campaign, shortly after which a bill to institute a Johns Hopkins private police force was introduced into the Maryland General Assembly at "request fBaltimore City Administration." On April 8, 2019, the Homewood Faculty Assembly unanimously passed a resolution requesting that the administration refrain from taking any further steps "toward the establishment of a private police force" until it could provide responses to several questions concerning accountability and oversight of the proposed police department, fears of Black faculty that the police department would target people of color, and alleged corruption involving Mayor Pugh.Ronald J. Daniels

Ronald Joel Daniels (born 1959) is a Canadian jurist, currently serving as the 14th president of the Johns Hopkins University since 2009. He served as provost at the University of Pennsylvania from 2005 to 2009.

Education

Daniels received a B ...

.George Floyd

George Perry Floyd Jr. (October 14, 1973 – May 25, 2020) was an African-American man who was murdered by a white police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota, during an arrest made after a store clerk suspected Floyd had used a counterfeit tw ...

and the subsequent protests, a group of Hopkins faculty along with 2,500 Hopkins staff, students, and community members signed a petition calling on president Daniels to reconsider the planned police department. The office of public safety issued a statement on June 10 saying "the JHPD does not yet exist. We committed to establishing this department through a slow, careful and fully open process. No other steps are planned at this time, and we will be in close communication with the city and our university community before any further steps are taken". Two days later, president Daniels announced the decision to "pause for at least the next two years the implementation of the JHPD." Despite this announcement, the next summer Johns Hopkins announced the appointment of Dr. Branville Bard Jr. to the newly created position of vice president for public safety.

The Community Safety and Strengthening Act requires the university to establish a civilian accountability board as well as a Memorandum Of Understanding (MOU) with the Baltimore Police Department. A draft MOU was made public on September 19, 2022 in advance of three scheduled town halls and a 30-day period to solicit feedback from the community. A message posted the same day as the draft MOU said that the document "will be modified to reflect what we hear and learn from our community." However, community members remained skeptical that the university is operating in good faith. A September 2022 article from Inside Higher Ed portrays the sentiment from the community, quoting a Johns Hopkins physician and professor who said "Hopkins engineers very closed and stage-managed town halls and does not execute any changes based on these town halls." The Baltimore Sun reported that the Coalition Against Policing by Hopkins planned to continue to obstruct the formation of JHPD, but that it must resort to "shutting down more university events," referring to the 2019 Garland Hall sit-in. The group proceeded to shut down the first town hall. According to reporting by the Baltimore Sun, the event "was moved to an online-only format after a crowd of chanting protesters took over the meeting stage." The MOU finalized on December 2, 2022, grants the JHPD primary jurisdiction over areas "owned, leased, or operated by, or under the control of" JHU as well as adjacent public property. Despite continued protest from university faculty calling for more oversight and clearly defined jurisdictional boundaries in accordance with the law, officer recruitment and training began in spring of 2024, with officers starting active duty in the summer of 2024.

Civil rights

African-Americans

Hopkins was a prominent abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

who supported Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. After his death, reports said his conviction was a decisive factor in enrolling Hopkins's first African-American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa. ...

student, Kelly Miller, a graduate student in physics, astronomy and mathematics.[MDhistoryonline.net](_blank)

Medicine in Maryland 1752–1920 As time passed, the university adopted a "separate but equal" stance more like other Baltimore institutions.Vivien Thomas

Vivien Theodore Thomas (August 29, 1910 – November 26, 1985) was an American laboratory supervisor who, in the 1940s, played a major role in developing a procedure now called the Blalock–Thomas–Taussig shunt used to treat blue baby syndr ...

was instrumental in developing and conducting the first successful blue baby operation in 1944. Despite such cases, racial diversity did not become commonplace at Johns Hopkins institutions until the 1960s and 1970s.

Women

Hopkins's most well-known battle for women's rights was the one led by daughters of trustees of the university; Mary E. Garrett, M. Carey Thomas, Mamie Gwinn, Elizabeth King, and Julia Rogers.nursing school

Nursing is a health care profession that "integrates the art and science of caring and focuses on the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and human functioning; prevention of illness and injury; facilitation of healing; and alle ...

opened in 1889 and accepted women and men as students. Other graduate schools were later opened to women by president Ira Remsen

Ira Remsen (February 10, 1846 – March 4, 1927) was an American chemist who introduced organic chemistry research and education in the United States along the lines of German universities where he received his early training. He was the first pr ...

in 1907. Christine Ladd-Franklin

Christine Ladd-Franklin (December 1, 1847 – March 5, 1930) was an American psychologist, logician, and mathematician.

Early life and education

Christine Ladd, sometimes known by the nickname "Kitty", was born on December 1, 1847, in Winds ...

was the first woman to earn a PhD at Hopkins, in mathematics in 1882. The trustees denied her the degree for decades and refused to change the policy about admitting women. In 1893, Florence Bascomb became the university's first female PhD.[ The decision to admit women at undergraduate level was not considered until the late 1960s and was eventually adopted in October 1969. As of 2009–2010, the undergraduate population was 47% female and 53% male.]

Freedom of speech

On September 5, 2013, cryptographer and Johns Hopkins university professor Matthew Green posted a blog entitled, "On the NSA", in which he contributed to the ongoing debate regarding the role of NIST

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is an agency of the United States Department of Commerce whose mission is to promote American innovation and industrial competitiveness. NIST's activities are organized into physical s ...

and NSA

The National Security Agency (NSA) is an intelligence agency of the United States Department of Defense, under the authority of the director of national intelligence (DNI). The NSA is responsible for global monitoring, collection, and proces ...

in formulating U.S. cryptography

Cryptography, or cryptology (from "hidden, secret"; and ''graphein'', "to write", or ''-logy, -logia'', "study", respectively), is the practice and study of techniques for secure communication in the presence of Adversary (cryptography), ...

standards. On September 9, 2013, Green received a take-down request for the "On the NSA" blog from interim Dean Andrew Douglas from the Johns Hopkins University Whiting School of Engineering

The Whiting School of Engineering is the engineering school of the Johns Hopkins University, a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland.

History

The engineering department at Johns Hopkins was originally created in 1913 as an educatio ...

.The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'', ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', and ProPublica.org

ProPublica (), legally Pro Publica, Inc., is a nonprofit investigative journalism organization based in New York City. ProPublica's investigations are conducted by its staff of full-time reporters, and the resulting stories are distributed to new ...

. Douglas subsequently issued a personal on-line apology to Green.

Campuses and divisions

Homewood

For its first two decades of existence, university was based in Downtown Baltimore. In the early 20th century, the trustees acquired the Homewood estate of Charles Carroll, son of Charles Carroll of Carollton, a signer of the

For its first two decades of existence, university was based in Downtown Baltimore. In the early 20th century, the trustees acquired the Homewood estate of Charles Carroll, son of Charles Carroll of Carollton, a signer of the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

. Carroll's Homewood House

The Homewood Museum is a historical museum located on the Johns Hopkins University campus in Baltimore, Maryland. It was listed as a National Historic Landmark in 1971, noted as a family home of Maryland's Carroll family. It, along with Evergree ...

is considered one of the finest examples of Federal architecture

Federal-style architecture is the name for the classical architecture built in the United States following the American Revolution between 1780 and 1830, and particularly from 1785 to 1815, which was influenced heavily by the works of And ...

, which most of the university's buildings are modeled after. Most undergraduate programs are on the Homewood Campus.

* Whiting School of Engineering

The Whiting School of Engineering is the engineering school of the Johns Hopkins University, a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland.

History

The engineering department at Johns Hopkins was originally created in 1913 as an educatio ...

: The Whiting School contains 14 undergraduate and graduate engineering programs and 12 additional areas of study.Zanvyl Krieger School of Arts and Sciences

The Krieger School of Arts and Sciences is the college of arts and sciences at the Johns Hopkins University, a private university in Baltimore, Maryland.

The school is based on the university's Homewood campus and, together with the Whiting Sc ...

: The Krieger School offers more than 60 undergraduate majors and minors and more than 40 graduate programs.School of Education

In the United States and Canada, a school of education (or college of education; ed school) is a division within a university that is devoted to scholarship in the field of education, which is an interdisciplinary branch of the social sciences e ...

has a building at the southern edge of the Homewood Campus, adjacent to Wyman Park Dell.

East Baltimore

Collectively known as Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions (JHMI) campus, the East Baltimore facility occupies several city blocks spreading from the Johns Hopkins Hospital

Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) is the teaching hospital and biomedical research facility of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1889, Johns Hopkins Hospital and its school of medicine are considered to be the foundin ...

trademark dome.

* Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health is the public health graduate school of Johns Hopkins University, a private university, private research university primarily based in Baltimore, Maryland.

It was founded as the Johns Hopkins ...

: The Bloomberg School was founded in 1916 and is the world's oldest and largest school of public health. It has consistently been ranked first in its field by '' U.S. News & World Report''.

* School of Medicine

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, professional school, or forms a part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, ...

: The School of Medicine is widely regarded as one of the best medical schools and biomedical research

Medical research (or biomedical research), also known as health research, refers to the process of using scientific methods with the aim to produce knowledge about human diseases, the prevention and treatment of illness, and the promotion of ...

institutes in the world.

* School of Nursing

Nurse education consists of the theoretical and practical training provided to nurses with the purpose to prepare them for their duties as nursing care professionals. This education is provided to student nurses by experienced nurses and other me ...

: The School of Nursing is one of America's oldest and pre-eminent schools for nursing education. It has consistently ranked first in the nation.

Mount Vernon

* Peabody Institute

The Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University is a Private university, private music and dance music school, conservatory and College-preparatory school, preparatory school in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1857, it became affiliat ...

: founded in 1857, is the oldest continuously active music conservatory in the United States; it became a division of Johns Hopkins in 1977. The Conservatory retains its own student body and grants degrees in musicology and performance, though all Hopkins and Peabody students may take courses at both institutions.

Harbor East

* Carey Business School

The Johns Hopkins Carey Business School is the graduate business school of Johns Hopkins University, a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. It was established in 2007 and offers full-time and part-time programs leading to the M ...

: The Carey Business School was established in 2007, incorporating divisions of the former School of Professional Studies in Business and Education. It was originally located on Charles Street, but relocated to the Legg Mason building in Harbor East in 2011.

Washington, D.C.

In 2019, Hopkins announced its purchase of the former Newseum

The Newseum (April 18, 1997–March 3, 2002 and April 11, 2008–December 31, 2019) was an American museum located first in Rosslyn, Virginia, and later at 555 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, in Washington, D.C., dedicated to news and journalism that ...

building located at 555 Pennsylvania Avenue

Pennsylvania Avenue is a primarily diagonal street in Washington, D.C. that connects the United States Capitol with the White House and then crosses northwest Washington, D.C. to Georgetown (Washington, D.C.), Georgetown. Traveling through So ...

, three blocks from the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called the Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the Seat of government, seat of the United States Congress, the United States Congress, legislative branch of the Federal government of the United States, federal g ...

, to house its Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

programs and centers. In 2023, the building was officially reopened as the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg Center, a 435,000-square-foot education facility that would house several divisions of the university.School of Advanced International Studies

The School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) is a graduate school of Johns Hopkins University based in Washington, D.C. The school also maintains campuses in Bologna, Italy and Nanjing, China.

The school is devoted to the study of int ...

(SAIS) is located in the Bloomberg Center in Washington D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, near the National Gallery of Art

The National Gallery of Art is an art museum in Washington, D.C., United States, located on the National Mall, between 3rd and 9th Streets, at Constitution Avenue NW. Open to the public and free of charge, the museum was privately established in ...

on Pennsylvania Avenue

Pennsylvania Avenue is a primarily diagonal street in Washington, D.C. that connects the United States Capitol with the White House and then crosses northwest Washington, D.C. to Georgetown (Washington, D.C.), Georgetown. Traveling through So ...

. In a 2024 survey, 65 percent of respondents ranked SAIS as a top 5 master's degree

A master's degree (from Latin ) is a postgraduate academic degree awarded by universities or colleges upon completion of a course of study demonstrating mastery or a high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional prac ...

program in international relations

International relations (IR, and also referred to as international studies, international politics, or international affairs) is an academic discipline. In a broader sense, the study of IR, in addition to multilateral relations, concerns al ...

, placing the program as the second-best in the nation.Krieger School of Arts and Sciences

The Krieger School of Arts and Sciences is the college of arts and sciences at the Johns Hopkins University, a private university in Baltimore, Maryland.

The school is based on the university's Homewood campus and, together with the Whiting Sc ...

, and Peabody Institute

The Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University is a Private university, private music and dance music school, conservatory and College-preparatory school, preparatory school in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1857, it became affiliat ...

.Newseum

The Newseum (April 18, 1997–March 3, 2002 and April 11, 2008–December 31, 2019) was an American museum located first in Rosslyn, Virginia, and later at 555 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, in Washington, D.C., dedicated to news and journalism that ...

)

Laurel, Maryland

The Applied Physics Laboratory

The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (or simply Applied Physics Laboratory, or APL) is a not-for-profit university-affiliated research center (UARC) in Howard County, Maryland. It is affiliated with Johns Hopkins University ...

(APL), in Laurel, Maryland

Laurel is a city in Maryland, United States, located midway between Washington, D.C., and Baltimore on the banks of the Patuxent River, in northern Prince George's County. Its population was 30,060 at the 2020 census. Founded as a mill town i ...

, specializes in research for the U.S. Department of Defense

The United States Department of Defense (DoD, USDOD, or DOD) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government charged with coordinating and supervising the six U.S. armed services: the Army, Navy, Marines, Air Force, Space Force, t ...

, NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

, and other government and civilian research agencies. Among other projects, it has designed, built, and flown spacecraft for NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

to the asteroid Eros, and the planets Mercury and Pluto. It has developed more than 100 biomedical devices, many in collaboration with the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

campus for the School of Arts and Sciences, APL also is the primary campus for master's degrees in a variety of STEM fields.

Other campuses

Domestic

* Columbia, Maryland

Columbia is a planned community in Howard County, Maryland, United States, consisting of 10 self-contained villages. With a population of 104,681 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the second-most-populous community in Maryland ...

: branches of the Carey Business School

The Johns Hopkins Carey Business School is the graduate business school of Johns Hopkins University, a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. It was established in 2007 and offers full-time and part-time programs leading to the M ...

Montgomery County, Maryland

Montgomery County is the most populous County (United States), county in the U.S. state of Maryland. As of the 2020 United States census, the county's population was 1,062,061, increasing by 9.3% from 2010. The county seat is Rockville, Maryland ...

, a campus for part-time programs in biosciences, engineering, business, and education

International

* Hopkins–Nanjing Center

The Hopkins–Nanjing Center (HNC; zh, s=中美中心, p=), formally the Johns Hopkins University–Nanjing University Center for Chinese and American Studies ( zh, s=南京大学—约翰斯·霍普金斯大学中美文化研究中心, p=, c=, t ...

* SAIS Europe

The SAIS Europe, located in Bologna, Italy, is the European campus of the School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) under Johns Hopkins University. SAIS Europe's degree programs emphasize international economics, international relations, Eu ...

- European campus of the School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), located in Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

, Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

Organization

The Johns Hopkins entity is structured as two corporations, the university and The Johns Hopkins Health System, formed in 1986. The president is JHU's chief executive officer and the university is organized into nine academic divisions.[

JHU's bylaws specify a board of trustees of between 18 and 65 voting members. Trustees serve six-year terms subject to a two-term limit. The alumni select 12 trustees. Four recent alumni serve 4-year terms, one per year, typically from the graduating class. The bylaws prohibit students, faculty or administrative staff from serving on the board, except the president as an ex-officio trustee.]

Academics

The full-time, four-year undergraduate program is "most selective" with low transfer-in and a high graduate co-existence.Association of American Universities

The Association of American Universities (AAU) is an organization of predominantly American research universities devoted to maintaining a strong system of academic research and education. Founded in 1900, it consists of 69 public and private ...

(AAU); it is also a member of the Consortium on Financing Higher Education

Formed in the mid-1970s, the Consortium on Financing Higher Education (COFHE) is an unincorporated, voluntary, institutionally-supported organization of 32 highly selective, private liberal arts colleges and universities, all of which are committe ...

(COFHE) and the Universities Research Association

The Universities Research Association (URA) is a non-profit association of more than 90 research universities, primarily but not exclusively in the United States. It has members also in Japan, Italy, and the United Kingdom. It was founded in 1965 ...

(URA).

Rankings

As of 2024–25, Johns Hopkins University was ranked the 6th best university in the nation (tied) and 13th best globally by '' U.S. News & World Report''.

Undergraduate admissions

The university's undergraduate programs are highly selective: in 2021, the Office of Admissions accepted about 4.9% of its 33,236 Regular Decision applicants and about 6.4% of its total 38,725 applicants. In 2022, 99% of admitted students graduated in the top 10% of their high school class.need-blind admission

Need-blind admission in the United States refers to a College admissions in the United States, college admission policy that does not take into account an applicant's financial status when deciding whether to accept them. This approach typically re ...

and meets the full financial need of all admitted students.

Libraries

The Johns Hopkins University Library system houses more than 3.6 million volumes

The Johns Hopkins University Library system houses more than 3.6 million volumesHomewood campus

The Homewood Campus is the main academic and administrative center of the Johns Hopkins University. It is located at 3400 North Charles Street in Baltimore, Maryland. It houses the two major undergraduate schools: the Zanvyl Krieger School of Art ...

), the Brody Learning Commons, the Hutzler Reading Room ("The Hut") in Gilman Hall, the John Work Garrett Library at Evergreen House

Evergreen Museum & Library is a historic house museum and research library in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. It is located between the campuses of the Notre Dame of Maryland University and Loyola University Maryland. It is operated by Johns ...

, and the George Peabody Library

The George Peabody Library is a library connected to the Johns Hopkins University, focused on research into the 19th century. It was formerly the Library of the Peabody Institute of music in the City of Baltimore, and is located on the Peabody c ...

at the Peabody Institute

The Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University is a Private university, private music and dance music school, conservatory and College-preparatory school, preparatory school in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1857, it became affiliat ...

campus.

The main library, constructed in the 1960s, was named for Milton S. Eisenhower, former president of the university and brother of former U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

. The university's stacks had previously been housed in Gilman Hall and departmental libraries.

Johns Hopkins University Press

The Johns Hopkins University Press is the publishing division of the Johns Hopkins University. It was founded in 1878 and holds the distinction of being the oldest continuously running university press

A university press is an academic publishing house specializing in monographs and scholarly journals. They are often an integral component of a large research university. They publish work that has been reviewed by scholars in the field. They pro ...

in the United States.

Center for Talented Youth

The Johns Hopkins University also offers the Center for Talented Youth

The Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth (CTY) is a gifted education program for school-age children founded in 1979 by psychologist Julian Stanley at Johns Hopkins University. It was established as a research study into how academically ad ...

program, a nonprofit organization dedicated to identifying and developing the talents of the most promising K-12 grade students worldwide. As part of the Johns Hopkins University, the "Center for Talented Youth" or CTY helps fulfill the university's mission of preparing students to make significant future contributions to the world. The Johns Hopkins Digital Media Center (DMC) is a multimedia lab space as well as an equipment, technology and knowledge resource for students interested in exploring creative uses of emerging media and use of technology.

Degrees offered

Johns Hopkins offers a number of degrees in various undergraduate majors leading to the BA and BS and various majors leading to the MA, MS and PhD for graduate students. Because Hopkins offers both undergraduate and graduate areas of study, many disciplines have multiple degrees available. Biomedical engineering

Biomedical engineering (BME) or medical engineering is the application of engineering principles and design concepts to medicine and biology for healthcare applications (e.g., diagnostic or therapeutic purposes). BME also integrates the logica ...

, perhaps one of Hopkins's best-known programs, offers bachelor's, master's, and doctoral degrees.

Research

The opportunity to participate in important research is one of the distinguishing characteristics of Hopkins's undergraduate education. About 80 percent of undergraduates perform independent research, often alongside top researchers.

The opportunity to participate in important research is one of the distinguishing characteristics of Hopkins's undergraduate education. About 80 percent of undergraduates perform independent research, often alongside top researchers.Institute of Medicine

The National Academy of Medicine (NAM), known as the Institute of Medicine (IoM) until 2015, is an American nonprofit, non-governmental organization. The National Academy of Medicine is a part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineerin ...

, forty-three Howard Hughes Medical Institute

The Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) is an American non-profit medical research organization headquartered in Chevy Chase, Maryland with additional facilities in Ashburn, Virginia. It was founded in 1953 by Howard Hughes, an American busin ...

Investigators, seventeen members of the National Academy of Engineering

The National Academy of Engineering (NAE) is an American Nonprofit organization, nonprofit, NGO, non-governmental organization. It is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), along with the National Academ ...

, and sixty-two members of the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, NGO, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the ...

. As of March 2025, 34 Nobel Prize winners have been affiliated with the university as alumni, faculty members or researchers, with the most recent winners being Gregg Semenza and William G. Kaelin.Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

and the Max Planck Society

The Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science (; abbreviated MPG) is a formally independent non-governmental and non-profit association of German research institutes. Founded in 1911 as the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, it was renamed to the M ...

in the number of ''total'' citations published in Thomson Reuters-indexed journals over 22 fields in America.National Aeronautics and Space Administration

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the United States's civil space program, aeronautics research and space research. Established in 1958, it su ...

(NASA), making it the leading recipient of NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

research and development

Research and development (R&D or R+D), known in some countries as OKB, experiment and design, is the set of innovative activities undertaken by corporations or governments in developing new services or products. R&D constitutes the first stage ...

funding.National Science Foundation

The U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) is an Independent agencies of the United States government#Examples of independent agencies, independent agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government that su ...

(NSF) ranking.Bloomberg Distinguished Professorships

Bloomberg Distinguished Professorships were established as part of a $350 million investment by Michael Bloomberg, Hopkins class of 1964, to Johns Hopkins University in 2013. Fifty faculty members, ten from Johns Hopkins University and forty recru ...

program was established by a $250 million gift from Michael Bloomberg

Michael Rubens Bloomberg (born February 14, 1942) is an American businessman and politician. He is the majority owner and co-founder of Bloomberg L.P., and was its CEO from 1981 to 2001 and again from 2014 to 2023. He served as the 108th mayo ...

. This program enables the university to recruit fifty researchers from around the world to joint appointments throughout the nine divisions and research centers. Each professor must be a leader in interdisciplinary

Interdisciplinarity or interdisciplinary studies involves the combination of multiple academic disciplines into one activity (e.g., a research project). It draws knowledge from several fields such as sociology, anthropology, psychology, economi ...

research and be active in undergraduate education

Undergraduate education is education conducted after secondary education and before postgraduate education, usually in a college or university. It typically includes all postsecondary programs up to the level of a bachelor's degree. For example, ...

.[Anderson, Nick]

" Bloomberg pledges $350 million to Johns Hopkins University "

, ''The Washington Post'', Washington, D.C., January 23, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2015. Directed by Vice Provost for Research Denis Wirtz

Denis Wirtz is the vice provost for research and Theophilus Halley Smoot Professor of Engineering Science at Johns Hopkins University. He is an expert in the Molecular mechanics, molecular and Biophysics, biophysical mechanisms of cell migration, ...

, there are currently thirty two Bloomberg Distinguished Professors at the university, including three Nobel Laureates

The Nobel Prizes (, ) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make outstanding contributions in th ...

, eight fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is a United States–based international nonprofit with the stated mission of promoting cooperation among scientists, defending scientific freedom, encouraging scientific responsib ...

, ten members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

, and thirteen members of the National Academies.

Research centers and institutes

Divisional

* School of Medicine

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, professional school, or forms a part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, ...

(28)School of Nursing

Nurse education consists of the theoretical and practical training provided to nurses with the purpose to prepare them for their duties as nursing care professionals. This education is provided to student nurses by experienced nurses and other me ...

(2)School of Advanced International Studies

The School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) is a graduate school of Johns Hopkins University based in Washington, D.C. The school also maintains campuses in Bologna, Italy and Nanjing, China.

The school is devoted to the study of int ...

(17)School of Engineering

Engineering education is the activity of teaching knowledge and principles to the professional development, professional practice of engineering. It includes an initial education (Diploma in Engineering, Dip.Eng.)and Bachelor of Engineering, ( ...

(16)School of Education

In the United States and Canada, a school of education (or college of education; ed school) is a division within a university that is devoted to scholarship in the field of education, which is an interdisciplinary branch of the social sciences e ...

(3)School of Business

A business school is a higher education institution or professional school that teaches courses leading to degrees in business administration or management. A business school may also be referred to as school of management, management school, s ...

* Applied Physics Laboratory

The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (or simply Applied Physics Laboratory, or APL) is a not-for-profit university-affiliated research center (UARC) in Howard County, Maryland. It is affiliated with Johns Hopkins University ...

Others

* Berman Institute of Bioethics

* Center for a Livable Future

* Center for Talented Youth

The Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth (CTY) is a gifted education program for school-age children founded in 1979 by psychologist Julian Stanley at Johns Hopkins University. It was established as a research study into how academically ad ...

* Graduate Program in Public Management

* Johns Hopkins Institute for Policy Studies

Johns may refer to:

Places

* Johns, Mississippi, an unincorporated community

* Johns, Oklahoma, United States, a community

* Johns Creek (Chattahoochee River), Georgia, United States

* Johns Island (disambiguation), islands in Canada and the Unit ...

* Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise

* Space Telescope Science Institute

The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) is the science operations center for the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), science operations and mission operations center for the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), and science operations center for the ...

Student life

Charles Village

Charles Village is a neighborhood located in the north-central area of Baltimore, Maryland, USA. It is a diverse, eclectic, international, largely middle-class area with many single-family homes that is in proximity to many of Baltimore's cultu ...

, the region of North Baltimore surrounding the university, has undergone several restoration projects, and the university has gradually bought the property around the school for additional student housing and dormitories. ''The Charles Village Project'', completed in 2008, brought new commercial spaces to the neighborhood. The project included Charles (now Scott-Bates) Commons, a new, modern residence hall that includes popular retail franchises.Goucher College

Goucher College ( ') is a Private university, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Towson, Maryland, United States. Founded in 1885 as a Nonsectarian, nonsecterian Women's colleges in the United States, ...

, and Towson University

Towson University (TU or Towson) is a public university in Towson, Maryland, United States. Founded in 1866 as Maryland's first training school for teachers, Towson University is a part of the University System of Maryland. Since its foundin ...

, as well as the nearby neighborhoods of Hampden Hampden may refer to:

Places Oceania

* Hampden, New Zealand

** Hampden (New Zealand electorate)

** Murchison, New Zealand, known as Hampden until 1882

* Hampden, Queensland

* Hampden, South Australia

* County of Hampden, Victoria, Australia

* Shir ...

, the Inner Harbor

The Inner Harbor is a historic seaport, tourist attraction, and landmark in Baltimore, Maryland. It was described by the Urban Land Institute in 2009 as "the model for post-industrial waterfront redevelopment around the world". The Inner Harbo ...

, Fells Point

Fell's Point is a historic waterfront neighborhood in southeastern Baltimore, Maryland, established around 1763 along the north shore of the Baltimore Harbor and the Northwest Branch of the Patapsco River. Located 1.5 miles east of Baltimore's d ...

, and Mount Vernon

Mount Vernon is the former residence and plantation of George Washington, a Founding Father, commander of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War, and the first president of the United States, and his wife, Martha. An American landmar ...

.

Students and alumni are active on and off campus. Johns Hopkins has been home to several secret societies

A secret society is an organization about which the activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence a ...