J. W. Gibbs on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

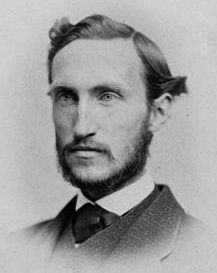

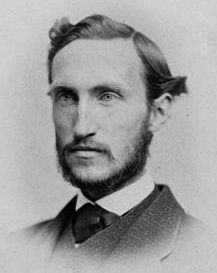

Josiah Willard Gibbs (; February 11, 1839 – April 28, 1903) was an American mechanical engineer and scientist who made fundamental theoretical contributions to

Gibbs was born in New Haven, Connecticut. He belonged to an old

Gibbs was born in New Haven, Connecticut. He belonged to an old

In 1863, Gibbs received the first Doctorate of Philosophy (PhD) in engineering granted in the US, for a thesis entitled "On the Form of the Teeth of Wheels in Spur Gearing", in which he used geometrical techniques to investigate the optimum design for

In 1863, Gibbs received the first Doctorate of Philosophy (PhD) in engineering granted in the US, for a thesis entitled "On the Form of the Teeth of Wheels in Spur Gearing", in which he used geometrical techniques to investigate the optimum design for

From 1880 to 1884, Gibbs worked on developing the

From 1880 to 1884, Gibbs worked on developing the  From 1882 to 1889, Gibbs wrote five papers on

From 1882 to 1889, Gibbs wrote five papers on

Gibbs never married, living all his life in his childhood home with his sister Julia and her husband Addison Van Name, who was the Yale librarian. Except for his customary summer vacations in the

Gibbs never married, living all his life in his childhood home with his sister Julia and her husband Addison Van Name, who was the Yale librarian. Except for his customary summer vacations in the

Gibbs's papers from the 1870s introduced the idea of expressing the internal energy ''U'' of a system in terms of the

Gibbs's papers from the 1870s introduced the idea of expressing the internal energy ''U'' of a system in terms of the

British scientists, including Maxwell, had relied on Hamilton's

British scientists, including Maxwell, had relied on Hamilton's

Though Gibbs's research on physical optics is less well known today than his other work, it made a significant contribution to classical

Though Gibbs's research on physical optics is less well known today than his other work, it made a significant contribution to classical

On the other hand, Gibbs did receive the major honors then possible for an academic scientist in the US. He was elected to the

On the other hand, Gibbs did receive the major honors then possible for an academic scientist in the US. He was elected to the

The first half of the 20th century saw the publication of two influential textbooks that soon came to be regarded as founding documents of

The first half of the 20th century saw the publication of two influential textbooks that soon came to be regarded as founding documents of  Gibbs's early papers on the use of graphical methods in thermodynamics reflect a powerfully original understanding of what mathematicians would later call "

Gibbs's early papers on the use of graphical methods in thermodynamics reflect a powerfully original understanding of what mathematicians would later call "

When the German physical chemist

When the German physical chemist  In 1945, Yale University created the J. Willard Gibbs Professorship in Theoretical Chemistry, held until 1973 by

In 1945, Yale University created the J. Willard Gibbs Professorship in Theoretical Chemistry, held until 1973 by

pp. 55–353

and ''The Collected Works of J. Willard Gibbs'' (1928), pp. 55–353. * E. B. Wilson, '' Vector Analysis, a text-book for the use of students of Mathematics and Physics, founded upon the Lectures of J. Willard Gibbs'', (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1929 901. * J. W. Gibbs, '' Elementary Principles in Statistical Mechanics, developed with especial reference to the rational foundation of thermodynamics'', (New York: Dover Publications, 1960

vol. I

an

vol. II

* '' The Collected Works of J. Willard Gibbs'', in two volumes, eds. W. R. Longley and R. G. Van Name, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1957 928. For scans of the 1928 printing, se

vol. I

an

vol. II

pp. xiii–xxviiii

(1906) and ''The Collected Works of J. Willard Gibbs'', vol. I, pp. xiii–xxviiii (1928). Also available her

* D. G. Caldi and G. D. Mostow (eds.), ''Proceedings of the Gibbs Symposium, Yale University, May 15–17, 1989'', (American Mathematical Society and American Institute of Physics, 1990). * W. H. Cropper, "The Greatest Simplicity: Willard Gibbs", in ''Great Physicists'', (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), pp. 106–123. * M. J. Crowe, ''A History of Vector Analysis: The Evolution of the Idea of a Vectorial System'', (New York: Dover, 1994 967. * J. G. Crowther, ''Famous American Men of Science'', (Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1969

vol I.

is currently available online. * P. Duhem

''Josiah-Willard Gibbs à propos de la publication de ses Mémoires scientifiques''

(Paris: A. Herman, 1908). * C. S. Hastings

"Josiah Willard Gibbs"

''Biographical Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences'', 6, 373–393 (1909). * M. J. Klein, "Gibbs, Josiah Willard", in ''Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography'', vol. 5, (Detroit: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2008), pp. 386–393. * M. Rukeyser, ''Willard Gibbs: American Genius'', (Woodbridge, CT: Ox Bow Press, 1988

"Reminiscences of Gibbs by a student and colleague"

''Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society'', 37, 401–416 (1931).

", in ''Selected Papers of Great American Scientists'', American Institute of Physics, (2003 976 *

"Gibbs"

by Muriel Rukeyser

Reflections on Gibbs: From Statistical Physics to the Amistad

by Leo Kadanoff, Prof.

National Academy of Sciences, Biography, Josiah Willard Gibbs

* Josiah Willard Gibbs Papers. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. {{DEFAULTSORT:Gibbs, Josiah Willard 1839 births 1903 deaths Thermodynamicists American mathematical analysts American physical chemists 19th-century American mathematicians 20th-century American mathematicians Foreign members of the Royal Society Yale School of Engineering & Applied Science alumni Heidelberg University alumni Yale University faculty Hopkins School alumni Scientists from New Haven, Connecticut Recipients of the Copley Medal Burials at Grove Street Cemetery American theoretical physicists American fluid dynamicists Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees Connecticut Republicans American philosophers of science Yale College alumni Statistical physicists Computational statisticians Members of the American Philosophical Society

physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

, chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

, and mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

. His work on the applications of thermodynamics

Thermodynamics is a branch of physics that deals with heat, Work (thermodynamics), work, and temperature, and their relation to energy, entropy, and the physical properties of matter and radiation. The behavior of these quantities is governed b ...

was instrumental in transforming physical chemistry

Physical chemistry is the study of macroscopic and microscopic phenomena in chemical systems in terms of the principles, practices, and concepts of physics such as motion, energy, force, time, thermodynamics, quantum chemistry, statistical mech ...

into a rigorous deductive science. Together with James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish physicist and mathematician who was responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism an ...

and Ludwig Boltzmann

Ludwig Eduard Boltzmann ( ; ; 20 February 1844 – 5 September 1906) was an Austrian mathematician and Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist. His greatest achievements were the development of statistical mechanics and the statistical ex ...

, he created statistical mechanics

In physics, statistical mechanics is a mathematical framework that applies statistical methods and probability theory to large assemblies of microscopic entities. Sometimes called statistical physics or statistical thermodynamics, its applicati ...

(a term that he coined), explaining the laws of thermodynamics

The laws of thermodynamics are a set of scientific laws which define a group of physical quantities, such as temperature, energy, and entropy, that characterize thermodynamic systems in thermodynamic equilibrium. The laws also use various param ...

as consequences of the statistical properties of ensembles of the possible states of a physical system composed of many particles. Gibbs also worked on the application of Maxwell's equations

Maxwell's equations, or Maxwell–Heaviside equations, are a set of coupled partial differential equations that, together with the Lorentz force law, form the foundation of classical electromagnetism, classical optics, Electrical network, electr ...

to problems in physical optics

In physics, physical optics, or wave optics, is the branch of optics that studies Interference (wave propagation), interference, diffraction, Polarization (waves), polarization, and other phenomena for which the ray approximation of geometric opti ...

. As a mathematician, he created modern vector calculus

Vector calculus or vector analysis is a branch of mathematics concerned with the differentiation and integration of vector fields, primarily in three-dimensional Euclidean space, \mathbb^3. The term ''vector calculus'' is sometimes used as a ...

(independently of the British scientist Oliver Heaviside

Oliver Heaviside ( ; 18 May 1850 – 3 February 1925) was an English mathematician and physicist who invented a new technique for solving differential equations (equivalent to the Laplace transform), independently developed vector calculus, an ...

, who carried out similar work during the same period) and described the Gibbs phenomenon in the theory of Fourier analysis.

In 1863, Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

awarded Gibbs the first American doctorate

A doctorate (from Latin ''doctor'', meaning "teacher") or doctoral degree is a postgraduate academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism '' licentia docendi'' ("licence to teach ...

in engineering

Engineering is the practice of using natural science, mathematics, and the engineering design process to Problem solving#Engineering, solve problems within technology, increase efficiency and productivity, and improve Systems engineering, s ...

. After a three-year sojourn in Europe, Gibbs spent the rest of his career at Yale, where he was a professor of mathematical physics

Mathematical physics is the development of mathematics, mathematical methods for application to problems in physics. The ''Journal of Mathematical Physics'' defines the field as "the application of mathematics to problems in physics and the de ...

from 1871 until his death in 1903. Working in relative isolation, he became the earliest theoretical scientist in the United States to earn an international reputation and was praised by Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

as "the greatest mind in American history". In 1901, Gibbs received what was then considered the highest honor awarded by the international scientific community, the Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is the most prestigious award of the Royal Society of the United Kingdom, conferred "for sustained, outstanding achievements in any field of science". The award alternates between the physical sciences or mathematics and the bio ...

of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

of London, "for his contributions to mathematical physics".

Commentators and biographers have remarked on the contrast between Gibbs's quiet, solitary life in turn of the century New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

and the great international impact of his ideas. Though his work was almost entirely theoretical, the practical value of Gibbs's contributions became evident with the development of industrial chemistry during the first half of the 20th century. According to Robert A. Millikan, in pure science, Gibbs "did for statistical mechanics and thermodynamics what Laplace

Pierre-Simon, Marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French polymath, a scholar whose work has been instrumental in the fields of physics, astronomy, mathematics, engineering, statistics, and philosophy. He summariz ...

did for celestial mechanics and Maxwell did for electrodynamics, namely, made his field a well-nigh finished theoretical structure".

Biography

Family background

Gibbs was born in New Haven, Connecticut. He belonged to an old

Gibbs was born in New Haven, Connecticut. He belonged to an old Yankee

The term ''Yankee'' and its contracted form ''Yank'' have several interrelated meanings, all referring to people from the United States. Their various meanings depend on the context, and may refer to New Englanders, the Northeastern United Stat ...

family that had produced distinguished American clergymen and academics since the 17th century. He was the fourth of five children and the only son of Josiah Willard Gibbs Sr., and his wife Mary Anna, ''née'' Van Cleve. On his father's side, he was descended from Samuel Willard, who served as acting President of Harvard College from 1701 to 1707. On his mother's side, one of his ancestors was the Rev. Jonathan Dickinson, the first president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial ...

). Gibbs's given name, which he shared with his father and several other members of his extended family, derived from his ancestor Josiah Willard, who had been Secretary of the Province of Massachusetts Bay

The Province of Massachusetts Bay was a colony in New England which became one of the thirteen original states of the United States. It was chartered on October 7, 1691, by William III and Mary II, the joint monarchs of the kingdoms of Eng ...

in the 18th century.Bumstead 1928 His paternal grandmother, Mercy (Prescott) Gibbs, was the sister of Rebecca Minot Prescott Sherman, the wife of American founding father Roger Sherman

Roger Sherman (April 19, 1721 – July 23, 1793) was an early American politician, lawyer, and a Founding Father of the United States. He is the only person to sign all four great state papers of the United States: the Continental Association, ...

; and he was the second cousin of Roger Sherman Baldwin

Roger Sherman Baldwin (January 4, 1793 – February 19, 1863) was an American politician who served as the 32nd Governor of Connecticut from 1844 to 1846 and a United States senator from 1847 to 1851. As a lawyer, his career was most notable ...

, see the Amistad case below.

The elder Gibbs was generally known to his family and colleagues as "Josiah", while the son was called "Willard". Josiah Gibbs was a linguist and theologian who served as professor of sacred literature at Yale Divinity School

Yale Divinity School (YDS) is one of the twelve graduate and professional schools of Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

Congregationalist theological education was the motivation at the founding of Yale, and the professional school has ...

from 1824 until his death in 1861. He is chiefly remembered today as the abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

who found an interpreter for the African passengers of the ship '' Amistad'', allowing them to testify during the trial that followed their rebellion against being sold as slaves.

Education

Willard Gibbs was educated at the Hopkins School and enteredYale College

Yale College is the undergraduate college of Yale University. Founded in 1701, it is the original school of the university. Although other Yale schools were founded as early as 1810, all of Yale was officially known as Yale College until 1887, ...

in 1854 at the age of 15. At Yale, Gibbs received prizes for excellence in mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

and Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, and he graduated in 1858, near the top of his class. He remained at Yale as a graduate student at the Sheffield Scientific School

Sheffield Scientific School was founded in 1847 as a school of Yale University, Yale College in New Haven, Connecticut, for instruction in science and engineering. Originally named the Yale Scientific School, it was renamed in 1861 in honor of Jos ...

. At age 19, soon after his graduation from college, Gibbs was inducted into the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences, a scholarly institution composed primarily of members of the Yale faculty.Rukeyser 1988, p. 104

Relatively few documents from the period survive and it is difficult to reconstruct the details of Gibbs's early career with precision.Wheeler 1998, pp. 23–24 In the opinion of biographers, Gibbs's principal mentor and champion, both at Yale and in the Connecticut Academy, was probably the astronomer and mathematician Hubert Anson Newton

Hubert Anson Newton FRS HFRSE (19 March 1830 – 12 August 1896), usually cited as H. A. Newton, was an American astronomer and mathematician, noted for his research on meteors.

Biography

Newton was born at Sherburne, New York, and graduated ...

, a leading authority on meteors, who remained Gibbs's lifelong friend and confidant. After the death of his father in 1861, Gibbs inherited enough money to make him financially independent.Rukeyser 1998, pp. 120, 142

Recurrent pulmonary trouble ailed the young Gibbs and his physicians were concerned that he might be susceptible to tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

, which had killed his mother. He also suffered from astigmatism

Astigmatism is a type of refractive error due to rotational asymmetry in the eye's refractive power. The lens and cornea of an eye without astigmatism are nearly spherical, with only a single radius of curvature, and any refractive errors ...

, whose treatment was then still largely unfamiliar to oculists, so that Gibbs had to diagnose himself and grind his own lenses.Wheeler 1998, pp. 29–31Rukeyser 1988, p. 143 Though in later years he used glasses

Glasses, also known as eyeglasses (American English), spectacles (Commonwealth English), or colloquially as specs, are vision eyewear with clear or tinted lenses mounted in a frame that holds them in front of a person's eyes, typically u ...

only for reading or other close work, Gibbs's delicate health and imperfect eyesight probably explain why he did not volunteer to fight in the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

of 1861–65.Wheeler 1998, p. 30 He was not conscripted and he remained at Yale for the duration of the war.Rukeyser 1998, p. 134

In 1863, Gibbs received the first Doctorate of Philosophy (PhD) in engineering granted in the US, for a thesis entitled "On the Form of the Teeth of Wheels in Spur Gearing", in which he used geometrical techniques to investigate the optimum design for

In 1863, Gibbs received the first Doctorate of Philosophy (PhD) in engineering granted in the US, for a thesis entitled "On the Form of the Teeth of Wheels in Spur Gearing", in which he used geometrical techniques to investigate the optimum design for gear

A gear or gearwheel is a rotating machine part typically used to transmit rotational motion and/or torque by means of a series of teeth that engage with compatible teeth of another gear or other part. The teeth can be integral saliences or ...

s.Wheeler 1998, p. 32 In 1861, Yale had become the first US university to offer a PhD degree and Gibbs's was only the fifth PhD granted in the US in any subject.

Career, 1863–1873

After graduation, Gibbs was appointed as tutor at the college for a term of three years. During the first two years, he taught Latin, and during the third year, he taught "natural philosophy" (i.e., physics). In 1866, he patented a design for arailway brake

A railway brake is a type of brake used on the cars of railway trains to enable deceleration, control acceleration (downhill) or to keep them immobile when parked. While the basic principle is similar to that on road vehicle usage, operationa ...

and read a paper before the Connecticut Academy, entitled "The Proper Magnitude of the Units of Length", in which he proposed a scheme for rationalizing the system of units of measurement used in mechanics.Wheeler 1998, appendix II.

After his term as tutor ended, Gibbs traveled to Europe with his sisters. They spent the winter of 1866–67 in Paris, where Gibbs attended lectures at the Sorbonne and the , given by such distinguished mathematical scientists as Joseph Liouville

Joseph Liouville ( ; ; 24 March 1809 – 8 September 1882) was a French mathematician and engineer.

Life and work

He was born in Saint-Omer in France on 24 March 1809. His parents were Claude-Joseph Liouville (an army officer) and Thérès ...

and Michel Chasles

Michel Floréal Chasles (; 15 November 1793 – 18 December 1880) was a French mathematician.

Biography

He was born at Épernon in France and studied at the École Polytechnique in Paris under Siméon Denis Poisson. In the War of the Sixth Coal ...

. Having undertaken a punishing regimen of study, Gibbs caught a serious cold and a doctor, fearing tuberculosis, advised him to rest on the Riviera, where he and his sisters spent several months and where he made a full recovery.

Moving to Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

, Gibbs attended the lectures taught by mathematicians Karl Weierstrass

Karl Theodor Wilhelm Weierstrass (; ; 31 October 1815 – 19 February 1897) was a German mathematician often cited as the " father of modern analysis". Despite leaving university without a degree, he studied mathematics and trained as a school t ...

and Leopold Kronecker

Leopold Kronecker (; 7 December 1823 – 29 December 1891) was a German mathematician who worked on number theory, abstract algebra and logic, and criticized Georg Cantor's work on set theory. Heinrich Weber quoted Kronecker

as having said, ...

, as well as by chemist Heinrich Gustav Magnus. In August 1867, Gibbs's sister Julia was married in Berlin to Addison Van Name, who had been Gibbs's classmate at Yale. The newly married couple returned to New Haven, leaving Gibbs and his sister Anna in Germany. In Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; ; ) is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, fifth-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, and with a population of about 163,000, of which roughly a quarter consists of studen ...

, Gibbs was exposed to the work of physicists Gustav Kirchhoff

Gustav Robert Kirchhoff (; 12 March 1824 – 17 October 1887) was a German chemist, mathematician, physicist, and spectroscopist who contributed to the fundamental understanding of electrical circuits, spectroscopy and the emission of black-body ...

and Hermann von Helmholtz

Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz (; ; 31 August 1821 – 8 September 1894; "von" since 1883) was a German physicist and physician who made significant contributions in several scientific fields, particularly hydrodynamic stability. The ...

, and chemist Robert Bunsen

Robert Wilhelm Eberhard Bunsen (;

30 March 1811

– 16 August 1899) was a German chemist. He investigated emission spectra of heated elements, and discovered caesium (in 1860) and rubidium (in 1861) with the physicist Gustav Kirchhoff. The Bu ...

. At the time, German academics were the leading authorities in the natural sciences, especially chemistry and thermodynamics

Thermodynamics is a branch of physics that deals with heat, Work (thermodynamics), work, and temperature, and their relation to energy, entropy, and the physical properties of matter and radiation. The behavior of these quantities is governed b ...

.

Gibbs returned to Yale in June 1869 and briefly taught French to engineering students. It was probably also around this time that he worked on a new design for a steam-engine governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

, his last significant investigation in mechanical engineering. In 1871, he was appointed Professor of Mathematical Physics at Yale, the first such professorship in the United States. Gibbs, who had independent means and had yet to publish anything, was assigned to teach graduate students exclusively and was hired without salary.Rukeyser 1988, pp. 181–182.

Career, 1873–1880

Gibbs published his first work in 1873. His papers on the geometric representation of thermodynamic quantities appeared in the ''Transactions of the Connecticut Academy''. These papers introduced the use of different type phase diagrams, which were his favorite aids to the imagination process when doing research, rather than the mechanical models, such as the ones thatMaxwell

Maxwell may refer to:

People

* Maxwell (surname), including a list of people and fictional characters with the name

** James Clerk Maxwell, mathematician and physicist

* Justice Maxwell (disambiguation)

* Maxwell baronets, in the Baronetage of N ...

used in constructing his electromagnetic theory, which might not completely represent their corresponding phenomena. Although the journal had few readers capable of understanding Gibbs's work, he shared reprints with correspondents in Europe and received an enthusiastic response from James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish physicist and mathematician who was responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism an ...

at Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

. Maxwell even made, with his own hands, a clay model illustrating Gibbs's construct. He then produced two plaster casts of his model and mailed one to Gibbs. That cast is on display at the Yale physics department.

Maxwell included a chapter on Gibbs's work in the next edition of his ''Theory of Heat'', published in 1875. He explained the usefulness of Gibbs's graphical methods in a lecture to the Chemical Society

The Chemical Society was a scientific society formed in 1841 (then named the Chemical Society of London) by 77 scientists as a result of increased interest in scientific matters. Chemist Robert Warington was the driving force behind its creation.

...

of London and even referred to it in the article on "Diagrams" that he wrote for the ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The is a general knowledge, general-knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It has been published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. since 1768, although the company has changed ownership seven times. The 2010 version of the 15th edition, ...

''. Prospects of collaboration between him and Gibbs were cut short by Maxwell's early death in 1879, aged 48. The joke later circulated in New Haven that "only one man lived who could understand Gibbs's papers. That was Maxwell, and now he is dead."

Gibbs then extended his thermodynamic analysis to multi-phase chemical systems (i.e., to systems composed of more than one form of matter) and considered a variety of concrete applications. He described that research in a monograph titled " On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances", published by the Connecticut Academy in two parts that appeared respectively in 1875 and 1878. That work, which covers about three hundred pages and contains exactly seven hundred numbered mathematical equations,Cropper 2001, p. 109. begins with a quotation from Rudolf Clausius

Rudolf Julius Emanuel Clausius (; 2 January 1822 – 24 August 1888) was a German physicist and mathematician and is considered one of the central founding fathers of the science of thermodynamics. By his restatement of Sadi Carnot's principle ...

that expresses what would later be called the first and second laws of thermodynamics

The laws of thermodynamics are a set of scientific laws which define a group of physical quantities, such as temperature, energy, and entropy, that characterize thermodynamic systems in thermodynamic equilibrium. The laws also use various param ...

: "The energy

Energy () is the physical quantity, quantitative physical property, property that is transferred to a physical body, body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of Work (thermodynamics), work and in the form of heat and l ...

of the world is constant. The entropy

Entropy is a scientific concept, most commonly associated with states of disorder, randomness, or uncertainty. The term and the concept are used in diverse fields, from classical thermodynamics, where it was first recognized, to the micros ...

of the world tends towards a maximum."

Gibbs's monograph rigorously and ingeniously applied his thermodynamic techniques to the interpretation of physico-chemical phenomena, explaining and relating what had previously been a mass of isolated facts and observations.Wheeler 1998, ch. V. The work has been described as "the '' Principia'' of thermodynamics" and as a work of "practically unlimited scope". It solidly laid the foundation for physical Chemistry. Wilhelm Ostwald, who translated Gibbs's monograph into German, referred to Gibbs as the "founder of chemical energetics". According to modern commentators,

Gibbs continued to work without pay until 1880, when the new Johns Hopkins University

The Johns Hopkins University (often abbreviated as Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Founded in 1876 based on the European research institution model, J ...

in Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the List of United States ...

offered him a position paying $3,000 per year. In response, Yale offered him an annual salary of $2,000, which he was content to accept.

In 1879, Gibbs derived the Gibbs–Appell equation of motion, rediscovered in 1900 by Paul Émile Appell

:''M. P. Appell is the same person: it stands for Monsieur Paul Appell''.

Paul Émile Appell (27 September 1855 in Strasbourg – 24 October 1930 in Paris) was a French mathematician and Rector of the University of Paris. Appell polynomials and ...

.

Career, 1880–1903

From 1880 to 1884, Gibbs worked on developing the

From 1880 to 1884, Gibbs worked on developing the exterior algebra

In mathematics, the exterior algebra or Grassmann algebra of a vector space V is an associative algebra that contains V, which has a product, called exterior product or wedge product and denoted with \wedge, such that v\wedge v=0 for every vector ...

of Hermann Grassmann

Hermann Günther Grassmann (, ; 15 April 1809 – 26 September 1877) was a German polymath known in his day as a linguist and now also as a mathematician. He was also a physicist, general scholar, and publisher. His mathematical work was littl ...

into a vector calculus

Vector calculus or vector analysis is a branch of mathematics concerned with the differentiation and integration of vector fields, primarily in three-dimensional Euclidean space, \mathbb^3. The term ''vector calculus'' is sometimes used as a ...

well-suited to the needs of physicists. With this object in mind, Gibbs distinguished between the dot and cross product

In mathematics, the cross product or vector product (occasionally directed area product, to emphasize its geometric significance) is a binary operation on two vectors in a three-dimensional oriented Euclidean vector space (named here E), and ...

s of two vectors and introduced the concept of dyadics. Similar work was carried out independently, and at around the same time, by the British mathematical physicist and engineer Oliver Heaviside

Oliver Heaviside ( ; 18 May 1850 – 3 February 1925) was an English mathematician and physicist who invented a new technique for solving differential equations (equivalent to the Laplace transform), independently developed vector calculus, an ...

. Gibbs sought to convince other physicists of the convenience of the vectorial approach over the quaternion

In mathematics, the quaternion number system extends the complex numbers. Quaternions were first described by the Irish mathematician William Rowan Hamilton in 1843 and applied to mechanics in three-dimensional space. The algebra of quater ...

ic calculus of William Rowan Hamilton

Sir William Rowan Hamilton (4 August 1805 – 2 September 1865) was an Irish astronomer, mathematician, and physicist who made numerous major contributions to abstract algebra, classical mechanics, and optics. His theoretical works and mathema ...

, which was then widely used by British scientists. This led him, in the early 1890s, to a controversy with Peter Guthrie Tait

Peter Guthrie Tait (28 April 18314 July 1901) was a Scottish Mathematical physics, mathematical physicist and early pioneer in thermodynamics. He is best known for the mathematical physics textbook ''Treatise on Natural Philosophy'', which he ...

and others in the pages of ''Nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

''.

Gibbs's lecture notes on vector calculus were privately printed in 1881 and 1884 for the use of his students, and were later adapted by Edwin Bidwell Wilson

Edwin Bidwell Wilson (April 25, 1879 – December 28, 1964) was an American mathematician, statistician, physicist and general polymath. He was the sole protégé of Yale University physicist Josiah Willard Gibbs and was mentor to MIT economist ...

into a textbook, ''Vector Analysis

Vector calculus or vector analysis is a branch of mathematics concerned with the differentiation and integration of vector fields, primarily in three-dimensional Euclidean space, \mathbb^3. The term ''vector calculus'' is sometimes used as a ...

'', published in 1901. That book helped to popularize the "del

Del, or nabla, is an operator used in mathematics (particularly in vector calculus) as a vector differential operator, usually represented by the nabla symbol ∇. When applied to a function defined on a one-dimensional domain, it denotes ...

" notation that is widely used today in electrodynamics

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge via electromagnetic fields. The electromagnetic force is one of the four fundamental forces of nature. It is the dominant force in the interacti ...

and fluid mechanics

Fluid mechanics is the branch of physics concerned with the mechanics of fluids (liquids, gases, and plasma (physics), plasmas) and the forces on them.

Originally applied to water (hydromechanics), it found applications in a wide range of discipl ...

. In other mathematical work, he re-discovered the "Gibbs phenomenon

In mathematics, the Gibbs phenomenon is the oscillatory behavior of the Fourier series of a piecewise continuously differentiable periodic function around a jump discontinuity. The Nth partial Fourier series of the function (formed by summing ...

" in the theory of Fourier series

A Fourier series () is an Series expansion, expansion of a periodic function into a sum of trigonometric functions. The Fourier series is an example of a trigonometric series. By expressing a function as a sum of sines and cosines, many problems ...

(which, unbeknownst to him and to later scholars, had been described fifty years before by an obscure English mathematician, Henry Wilbraham).

physical optics

In physics, physical optics, or wave optics, is the branch of optics that studies Interference (wave propagation), interference, diffraction, Polarization (waves), polarization, and other phenomena for which the ray approximation of geometric opti ...

, in which he investigated birefringence

Birefringence, also called double refraction, is the optical property of a material having a refractive index that depends on the polarization and propagation direction of light. These optically anisotropic materials are described as birefrin ...

and other optical phenomena and defended Maxwell's electromagnetic theory of light against the mechanical theories of Lord Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin (26 June 182417 December 1907), was a British mathematician, Mathematical physics, mathematical physicist and engineer. Born in Belfast, he was the Professor of Natural Philosophy (Glasgow), professor of Natur ...

and others. In his work on optics, just as much as in his work on thermodynamics, Gibbs deliberately avoided speculating about the microscopic structure of matter and purposefully confined his research problems to those that can be solved from broad general principles and experimentally confirmed facts. The methods that he used were highly original and the obtained results showed decisively the correctness of Maxwell's electromagnetic theory.

Gibbs coined the term ''statistical mechanics'' and introduced key concepts in the corresponding mathematical description of physical systems, including the notions of chemical potential

In thermodynamics, the chemical potential of a Chemical specie, species is the energy that can be absorbed or released due to a change of the particle number of the given species, e.g. in a chemical reaction or phase transition. The chemical potent ...

(1876), and statistical ensemble

In physics, specifically statistical mechanics, an ensemble (also statistical ensemble) is an idealization consisting of a large number of virtual copies (sometimes infinitely many) of a system, considered all at once, each of which represents a ...

(1902). Gibbs's derivation of the laws of thermodynamics from the statistical properties of systems consisting of many particles was presented in his highly influential textbook ''Elementary Principles in Statistical Mechanics'', published in 1902, a year before his death.

Gibbs's retiring personality and intense focus on his work limited his accessibility to students. His principal protégé was Edwin Bidwell Wilson, who nonetheless explained that "except in the classroom I saw very little of Gibbs. He had a way, toward the end of the afternoon, of taking a stroll about the streets between his study in the old Sloane Laboratory and his home—a little exercise between work and dinner—and one might occasionally come across him at that time."Wilson 1931 Gibbs did supervise the doctoral thesis on mathematical economics written by Irving Fisher

Irving Fisher (February 27, 1867 – April 29, 1947) was an American economist, statistician, inventor, eugenicist and progressive social campaigner. He was one of the earliest American neoclassical economists, though his later work on debt de ...

in 1891. After Gibbs's death, Fisher financed the publication of his ''Collected Works''. Another distinguished student was Lee De Forest #REDIRECT Lee de Forest

{{redirect category shell, {{R from move{{R from other capitalisation ...

, later a pioneer of radio technology.

Gibbs died in New Haven on April 28, 1903, at the age of 64, the victim of an acute intestinal obstruction. A funeral was conducted two days later at his home on 121 High Street, and his body was buried in the nearby Grove Street Cemetery

Grove Street Cemetery or Grove Street Burial Ground is a cemetery in New Haven, Connecticut, that is surrounded by the Yale University campus. It was organized in 1796 as the New Haven Burying Ground and incorporated in October 1797 to replace th ...

. In May, Yale organized a memorial meeting at the Sloane Laboratory. The eminent British physicist J. J. Thomson was in attendance and delivered a brief address.

Personal life and character

Gibbs never married, living all his life in his childhood home with his sister Julia and her husband Addison Van Name, who was the Yale librarian. Except for his customary summer vacations in the

Gibbs never married, living all his life in his childhood home with his sister Julia and her husband Addison Van Name, who was the Yale librarian. Except for his customary summer vacations in the Adirondacks

The Adirondack Mountains ( ) are a massif of mountains in Northeastern New York (state), New York which form a circular dome approximately wide and covering about . The region contains more than 100 peaks, including Mount Marcy, which is the hi ...

(at Keene Valley, New York

Keene is a town in central Essex County, New York, United States. It includes the hamlets of Keene, Keene Valley, and St. Huberts, with a total population of 1,144 as of the 2020 census

The town is part of the Adirondack Park, and includes ...

) and later at the White Mountains (in Intervale, New Hampshire),Seeger 1974, pp. 15–16. his sojourn in Europe in 1866–1869 was almost the only time that Gibbs spent outside New Haven. He joined Yale's College Church (a Congregational church

Congregationalism (also Congregational Churches or Congregationalist Churches) is a Reformed Christian (Calvinist) tradition of Protestant Christianity in which churches practice congregational government. Each congregation independently a ...

) at the end of his freshman year and remained a regular attendant for the rest of his life.Wheeler, 1998, p. 16. Gibbs generally voted for the Republican candidate in presidential elections but, like other "Mugwump

The Mugwumps were History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican political activists in the United States who were intensely opposed to political corruption. They were never formally organized. They famously Party switching, swit ...

s", his concern over the growing corruption associated with machine politics

In the politics of Representative democracy, representative democracies, a political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by the use of tangible incentives (such as money or political jobs) and that is characterized by a hi ...

led him to support Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

, a conservative Democrat, in the election of 1884. Little else is known of his religious or political views, which he mostly kept to himself.

Gibbs did not produce a substantial personal correspondence, and many of his letters were later lost or destroyed. Beyond the technical writings concerning his research, he published only two other pieces: a brief obituary for Rudolf Clausius

Rudolf Julius Emanuel Clausius (; 2 January 1822 – 24 August 1888) was a German physicist and mathematician and is considered one of the central founding fathers of the science of thermodynamics. By his restatement of Sadi Carnot's principle ...

, one of the founders of the mathematical theory of thermodynamics, and a longer biographical memoir of his mentor at Yale, H. A. Newton. In Edward Bidwell Wilson's view,

According to Lynde Wheeler, who had been Gibbs's student at Yale, in his later years Gibbs

He was a careful investor and financial manager, and at his death in 1903 his estate was valued at $100,000 (roughly $ today). For many years, he served as trustee, secretary, and treasurer of his alma mater, the Hopkins School.Wheeler, 1998, p. 144. US President Chester A. Arthur appointed him as one of the commissioners to the National Conference of Electricians, which convened in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

in September 1884, and Gibbs presided over one of its sessions. A keen and skilled horseman, Gibbs was seen habitually in New Haven driving his sister's carriage

A carriage is a two- or four-wheeled horse-drawn vehicle for passengers. In Europe they were a common mode of transport for the wealthy during the Roman Empire, and then again from around 1600 until they were replaced by the motor car around 1 ...

. In an obituary published in the '' American Journal of Science'', Gibbs's former student Henry A. Bumstead referred to Gibbs's personal character:

Major scientific contributions

Chemical and electrochemical thermodynamics

entropy

Entropy is a scientific concept, most commonly associated with states of disorder, randomness, or uncertainty. The term and the concept are used in diverse fields, from classical thermodynamics, where it was first recognized, to the micros ...

''S'', in addition to the usual state variable

A state variable is one of the set of Variable (mathematics), variables that are used to describe the mathematical "state" of a dynamical system. Intuitively, the state of a system describes enough about the system to determine its future behavi ...

s of volume ''V'', pressure ''p'', and temperature ''T''. He also introduced the concept of the chemical potential

In thermodynamics, the chemical potential of a Chemical specie, species is the energy that can be absorbed or released due to a change of the particle number of the given species, e.g. in a chemical reaction or phase transition. The chemical potent ...

of a given chemical species, defined to be the rate of the increase in ''U'' associated with the increase in the number ''N'' of molecules of that species (at constant entropy and volume). Thus, it was Gibbs who first combined the first and second laws of thermodynamics

The laws of thermodynamics are a set of scientific laws which define a group of physical quantities, such as temperature, energy, and entropy, that characterize thermodynamic systems in thermodynamic equilibrium. The laws also use various param ...

by expressing the infinitesimal change in the internal energy, d''U'', of a closed system

A closed system is a natural physical system that does not allow transfer of matter in or out of the system, althoughin the contexts of physics, chemistry, engineering, etc.the transfer of energy (e.g. as work or heat) is allowed.

Physics

In cl ...

in the form

:

where ''T'' is the absolute temperature

Thermodynamic temperature, also known as absolute temperature, is a physical quantity which measures temperature starting from absolute zero, the point at which particles have minimal thermal motion.

Thermodynamic temperature is typically expres ...

, ''p'' is the pressure, d''S'' is an infinitesimal change in entropy and d''V'' is an infinitesimal change of volume. The last term is the sum, over all the chemical species in a chemical reaction, of the chemical potential, ''μ''i, of the ''i''-th species, multiplied by the infinitesimal change in the number of moles, d''N''i of that species. By taking the Legendre transform of this expression, he defined the concepts of enthalpy

Enthalpy () is the sum of a thermodynamic system's internal energy and the product of its pressure and volume. It is a state function in thermodynamics used in many measurements in chemical, biological, and physical systems at a constant extern ...

''H'' and Gibbs free energy

In thermodynamics, the Gibbs free energy (or Gibbs energy as the recommended name; symbol is a thermodynamic potential that can be used to calculate the maximum amount of Work (thermodynamics), work, other than Work (thermodynamics)#Pressure–v ...

''G'':

:

This compares to the expression for Helmholtz free energy

In thermodynamics, the Helmholtz free energy (or Helmholtz energy) is a thermodynamic potential that measures the useful work obtainable from a closed thermodynamic system at a constant temperature ( isothermal). The change in the Helmholtz ene ...

''A'':

:

When the Gibbs free energy for a chemical reaction is negative, the reaction will proceed spontaneously. When a chemical system is at equilibrium, the change in Gibbs free energy is zero. An equilibrium constant

The equilibrium constant of a chemical reaction is the value of its reaction quotient at chemical equilibrium, a state approached by a dynamic chemical system after sufficient time has elapsed at which its composition has no measurable tendency ...

is simply related to the free energy change when the reactants are in their standard state

The standard state of a material (pure substance, mixture or solution) is a reference point used to calculate its properties under different conditions. A degree sign (°) or a superscript ⦵ symbol (⦵) is used to designate a thermodynamic q ...

s:

:

Chemical potential

In thermodynamics, the chemical potential of a Chemical specie, species is the energy that can be absorbed or released due to a change of the particle number of the given species, e.g. in a chemical reaction or phase transition. The chemical potent ...

is usually defined as partial molar Gibbs free energy:

:

Gibbs also obtained what later came to be known as the " Gibbs–Duhem equation".

In an electrochemical reaction

Electrochemistry is the branch of physical chemistry concerned with the relationship between electrical potential difference and identifiable chemical change. These reactions involve electrons moving via an electronically conducting phase (typica ...

characterized by an electromotive force

In electromagnetism and electronics, electromotive force (also electromotance, abbreviated emf, denoted \mathcal) is an energy transfer to an electric circuit per unit of electric charge, measured in volts. Devices called electrical ''transducer ...

ℰ and an amount of transferred charge ''Q'', Gibbs's starting equation becomes

:

The publication of the paper " On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances" (1874–1878) is now regarded as a landmark in the development of chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

. In it, Gibbs developed a rigorous mathematical theory for various transport phenomena

In engineering, physics, and chemistry, the study of transport phenomena concerns the exchange of mass, energy, charge, momentum and angular momentum between observed and studied systems. While it draws from fields as diverse as continuum mec ...

, including adsorption

Adsorption is the adhesion of atoms, ions or molecules from a gas, liquid or dissolved solid to a surface. This process creates a film of the ''adsorbate'' on the surface of the ''adsorbent''. This process differs from absorption, in which a ...

, electrochemistry

Electrochemistry is the branch of physical chemistry concerned with the relationship between Electric potential, electrical potential difference and identifiable chemical change. These reactions involve Electron, electrons moving via an electronic ...

, and the Marangoni effect

The Marangoni effect (also called the Gibbs–Marangoni effect) is the mass transfer along an Interface (chemistry), interface between two phases due to a gradient of the surface tension. In the case of temperature dependence, this phenomenon may ...

in fluid mixtures. He also formulated the phase rule

:

for the number ''F'' of variables that may be independently controlled in an equilibrium mixture of ''C'' components existing in ''P'' phases. The phase rule is very useful in diverse areas, such as metallurgy, mineralogy, and petrology. It can also be applied to various research problems in physical chemistry.

Statistical mechanics

Together withJames Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish physicist and mathematician who was responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism an ...

and Ludwig Boltzmann

Ludwig Eduard Boltzmann ( ; ; 20 February 1844 – 5 September 1906) was an Austrian mathematician and Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist. His greatest achievements were the development of statistical mechanics and the statistical ex ...

, Gibbs founded "statistical mechanics", a term that he coined to identify the branch of theoretical physics that accounts for the observed thermodynamic properties of systems in terms of the statistics of ensembles of all possible physical states of a system composed of many particles. He introduced the concept of " phase of a mechanical system". He used the concept to define the microcanonical, canonical, and grand canonical ensemble

In statistical mechanics, the grand canonical ensemble (also known as the macrocanonical ensemble) is the statistical ensemble that is used to represent the possible states of a mechanical system of particles that are in thermodynamic equilibri ...

s; all related to the Gibbs measure, thus obtaining a more general formulation of the statistical properties of many-particle systems than Maxwell and Boltzmann had achieved before him.

Gibbs generalized Boltzmann's statistical interpretation of entropy

Entropy is a scientific concept, most commonly associated with states of disorder, randomness, or uncertainty. The term and the concept are used in diverse fields, from classical thermodynamics, where it was first recognized, to the micros ...

by defining the entropy of an arbitrary ensemble as

:

where is the Boltzmann constant

The Boltzmann constant ( or ) is the proportionality factor that relates the average relative thermal energy of particles in a ideal gas, gas with the thermodynamic temperature of the gas. It occurs in the definitions of the kelvin (K) and the ...

, while the sum is over all possible microstates

A microstate or ministate is a sovereign state having a very small population or land area, usually both. However, the meanings of "state" and "very small" are not well-defined in international law. Some recent attempts to define microstates ...

, with the corresponding probability of the microstate (see Gibbs entropy formula

The concept entropy was first developed by German physicist Rudolf Clausius in the mid-nineteenth century as a thermodynamic property that predicts that certain spontaneous processes are irreversible or impossible. In statistical mechanics, entrop ...

). This same formula would later play a central role in Claude Shannon

Claude Elwood Shannon (April 30, 1916 – February 24, 2001) was an American mathematician, electrical engineer, computer scientist, cryptographer and inventor known as the "father of information theory" and the man who laid the foundations of th ...

's information theory

Information theory is the mathematical study of the quantification (science), quantification, Data storage, storage, and telecommunications, communication of information. The field was established and formalized by Claude Shannon in the 1940s, ...

and is therefore often seen as the basis of the modern information-theoretical interpretation of thermodynamics.

According to Henri Poincaré

Jules Henri Poincaré (, ; ; 29 April 185417 July 1912) was a French mathematician, Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist, engineer, and philosophy of science, philosopher of science. He is often described as a polymath, and in mathemati ...

, writing in 1904, even though Maxwell and Boltzmann had previously explained the irreversibility

In thermodynamics, an irreversible process is a process that cannot be undone. All complex natural processes are irreversible, although a phase transition at the coexistence temperature (e.g. melting of ice cubes in water) is well approximated a ...

of macroscopic physical processes in probabilistic terms, "the one who has seen it most clearly, in a book too little read because it is a little difficult to read, is Gibbs, in his ''Elementary Principles of Statistical Mechanics''". Gibbs's analysis of irreversibility, and his formulation of Boltzmann's H-theorem

In classical statistical mechanics, the ''H''-theorem, introduced by Ludwig Boltzmann in 1872, describes the tendency of the quantity ''H'' (defined below) to decrease in a nearly-ideal gas of molecules.L. Boltzmann,Weitere Studien über das Wär ...

and of the ergodic hypothesis, were major influences on the mathematical physics of the 20th century.

Gibbs was well aware that the application of the equipartition theorem

In classical physics, classical statistical mechanics, the equipartition theorem relates the temperature of a system to its average energy, energies. The equipartition theorem is also known as the law of equipartition, equipartition of energy, ...

to large systems of classical particles failed to explain the measurements of the specific heats of both solids and gases, and he argued that this was evidence of the danger of basing thermodynamics on "hypotheses about the constitution of matter". Gibbs's own framework for statistical mechanics, based on ensembles of macroscopically indistinguishable microstates

A microstate or ministate is a sovereign state having a very small population or land area, usually both. However, the meanings of "state" and "very small" are not well-defined in international law. Some recent attempts to define microstates ...

, could be carried over almost intact after the discovery that the microscopic laws of nature obey quantum rules, rather than the classical laws known to Gibbs and to his contemporaries. His resolution of the so-called "Gibbs paradox

In statistical mechanics, a semi-classical derivation of entropy that does not take into account the Identical particles, indistinguishability of particles yields an expression for entropy which is not extensive variable, extensive (is not proport ...

", about the entropy of the mixing of gases, is now often cited as a prefiguration of the indistinguishability of particles required by quantum physics.

Vector analysis

quaternion

In mathematics, the quaternion number system extends the complex numbers. Quaternions were first described by the Irish mathematician William Rowan Hamilton in 1843 and applied to mechanics in three-dimensional space. The algebra of quater ...

s in order to express the dynamics of physical quantities, like the electric and magnetic fields, having both a magnitude and a direction in three-dimensional space. Following W. K. Clifford in his '' Elements of Dynamic'' (1888), Gibbs noted that the product of quaternions could be separated into two parts: a one-dimensional (scalar) quantity and a three-dimensional vector

Vector most often refers to:

* Euclidean vector, a quantity with a magnitude and a direction

* Disease vector, an agent that carries and transmits an infectious pathogen into another living organism

Vector may also refer to:

Mathematics a ...

, so that the use of quaternions involved mathematical complications and redundancies that could be avoided in the interest of simplicity and to facilitate teaching. In his Yale classroom notes he defined two distinct types of products for a pair of vectors: a dot product

In mathematics, the dot product or scalar productThe term ''scalar product'' means literally "product with a Scalar (mathematics), scalar as a result". It is also used for other symmetric bilinear forms, for example in a pseudo-Euclidean space. N ...

(or scalar product) and a cross product

In mathematics, the cross product or vector product (occasionally directed area product, to emphasize its geometric significance) is a binary operation on two vectors in a three-dimensional oriented Euclidean vector space (named here E), and ...

(or vector product). He also introduced the now common notation for them. Through the 1901 textbook ''Vector Analysis

Vector calculus or vector analysis is a branch of mathematics concerned with the differentiation and integration of vector fields, primarily in three-dimensional Euclidean space, \mathbb^3. The term ''vector calculus'' is sometimes used as a ...

'' prepared by E. B. Wilson from Gibbs notes, he was largely responsible for the development of the vector calculus

Vector calculus or vector analysis is a branch of mathematics concerned with the differentiation and integration of vector fields, primarily in three-dimensional Euclidean space, \mathbb^3. The term ''vector calculus'' is sometimes used as a ...

techniques still used today in electrodynamics and fluid mechanics.

While he was working on vector analysis in the late 1870s, Gibbs discovered that his approach was similar to the one that Grassmann had taken in his "multiple algebra".Letter by Gibbs to Victor Schlegel

Victor Schlegel (4 March 1843 – 22 November 1905) was a German mathematician. He is remembered for promoting the geometric algebra of Hermann Grassmann and for a method of visualizing polytopes called Schlegel diagrams.

In the nineteenth ce ...

, quoted in Wheeler 1998, pp. 107–109 Gibbs then sought to publicize Grassmann's work, stressing that it was both more general and historically prior to Hamilton's quaternionic algebra. To establish priority of Grassmann's ideas, Gibbs convinced Grassmann's heirs to seek the publication in Germany of the essay "Theorie der Ebbe und Flut" on tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ...

s that Grassmann had submitted in 1840 to the faculty at the University of Berlin

The Humboldt University of Berlin (, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin, Germany.

The university was established by Frederick William III on the initiative of Wilhelm von Humbol ...

, in which he had first introduced the notion of what would later be called a vector space

In mathematics and physics, a vector space (also called a linear space) is a set (mathematics), set whose elements, often called vector (mathematics and physics), ''vectors'', can be added together and multiplied ("scaled") by numbers called sc ...

( linear space).Wheeler 1998, pp. 113–116

As Gibbs had advocated in the 1880s and 1890s, quaternions were eventually all but abandoned by physicists in favor of the vectorial approach developed by him and, independently, by Oliver Heaviside

Oliver Heaviside ( ; 18 May 1850 – 3 February 1925) was an English mathematician and physicist who invented a new technique for solving differential equations (equivalent to the Laplace transform), independently developed vector calculus, an ...

. Gibbs applied his vector methods to the determination of planetary and comet orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an ...

s. He also developed the concept of mutually reciprocal triads of vectors that later proved to be of importance in crystallography

Crystallography is the branch of science devoted to the study of molecular and crystalline structure and properties. The word ''crystallography'' is derived from the Ancient Greek word (; "clear ice, rock-crystal"), and (; "to write"). In J ...

.

Physical optics

Though Gibbs's research on physical optics is less well known today than his other work, it made a significant contribution to classical

Though Gibbs's research on physical optics is less well known today than his other work, it made a significant contribution to classical electromagnetism

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge via electromagnetic fields. The electromagnetic force is one of the four fundamental forces of nature. It is the dominant force in the interacti ...

by applying Maxwell's equations

Maxwell's equations, or Maxwell–Heaviside equations, are a set of coupled partial differential equations that, together with the Lorentz force law, form the foundation of classical electromagnetism, classical optics, Electrical network, electr ...

to the theory of optical processes such as birefringence

Birefringence, also called double refraction, is the optical property of a material having a refractive index that depends on the polarization and propagation direction of light. These optically anisotropic materials are described as birefrin ...

, dispersion, and optical activity

Optical rotation, also known as polarization rotation or circular birefringence, is the rotation of the orientation of the plane of polarization about the optical axis of linearly polarized light as it travels through certain materials. Circul ...

.Wheeler 1998, ch. VIII In that work, Gibbs showed that those processes could be accounted for by Maxwell's equations without any special assumptions about the microscopic structure of matter or about the nature of the medium in which electromagnetic waves were supposed to propagate (the so-called luminiferous ether). Gibbs also stressed that the absence of a longitudinal electromagnetic wave, which is needed to account for the observed properties of light

Light, visible light, or visible radiation is electromagnetic radiation that can be visual perception, perceived by the human eye. Visible light spans the visible spectrum and is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400– ...

, is automatically guaranteed by Maxwell's equations (by virtue of what is now called their " gauge invariance"), whereas in mechanical theories of light, such as Lord Kelvin's, it must be imposed as an ''ad hoc'' condition on the properties of the aether.

In his last paper on physical optics, Gibbs concluded that

Shortly afterwards, the electromagnetic nature of light was demonstrated by the experiments of Heinrich Hertz

Heinrich Rudolf Hertz (; ; 22 February 1857 – 1 January 1894) was a German physicist who first conclusively proved the existence of the electromagnetic waves predicted by James Clerk Maxwell's equations of electromagnetism.

Biography

Heinri ...

in Germany.

Scientific recognition

Gibbs worked at a time when there was little tradition of rigorous theoretical science in the United States. His research was not easily understandable to his students or his colleagues, and he made no effort to popularize his ideas or to simplify their exposition to make them more accessible. His seminal work on thermodynamics was published mostly in the ''Transactions of the Connecticut Academy'', a journal edited by his librarian brother-in-law, which was little read in the US and even less so in Europe. When Gibbs submitted his long paper on the equilibrium of heterogeneous substances to the academy, bothElias Loomis

Elias Loomis (August 7, 1811 – August 15, 1889) was an American mathematician. He served as a professor of mathematics and natural philosophy at Case Western Reserve University, Western Reserve College (now Case Western Reserve University), the ...

and H. A. Newton protested that they did not understand Gibbs's work at all, but they helped to raise the money needed to pay for the typesetting of the many mathematical symbols in the paper. Several Yale faculty members, as well as business and professional men in New Haven, contributed funds for that purpose.Rukeyser 1998, pp. 225–226

Even though it had been immediately embraced by Maxwell, Gibbs's graphical formulation of the laws of thermodynamics came into widespread use only in the mid 20th century, with the work of László Tisza and Herbert Callen

Herbert Bernard Callen (July 1, 1919 – May 22, 1993) was an American physicist specializing in thermodynamics and statistical mechanics. He is considered one of the founders of the modern theory of irreversible thermodynamics, and is the author ...

. According to James Gerald Crowther,

On the other hand, Gibbs did receive the major honors then possible for an academic scientist in the US. He was elected to the

On the other hand, Gibbs did receive the major honors then possible for an academic scientist in the US. He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, NGO, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the ...

in 1879 and received the 1880 Rumford Prize from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

for his work on chemical thermodynamics. In 1895, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

in 1895. He was also awarded honorary doctorates by Princeton University and Williams College

Williams College is a Private college, private liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Williamstown, Massachusetts, United States. It was established as a men's college in 1793 with funds from the estate of Ephraim ...

.

In Europe, Gibbs was inducted as honorary member of the London Mathematical Society

The London Mathematical Society (LMS) is one of the United Kingdom's Learned society, learned societies for mathematics (the others being the Royal Statistical Society (RSS), the Institute of Mathematics and its Applications (IMA), the Edinburgh ...

in 1892 and elected Foreign Member of the Royal Society in 1897. He was elected as corresponding member of the Prussian and French Academies of Science and received honorary doctorates from the universities of Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

, Erlangen

Erlangen (; , ) is a Middle Franconian city in Bavaria, Germany. It is the seat of the administrative district Erlangen-Höchstadt (former administrative district Erlangen), and with 119,810 inhabitants (as of 30 September 2024), it is the smalle ...

, and Christiania (now Oslo). The Royal Society further honored Gibbs in 1901 with the Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is the most prestigious award of the Royal Society of the United Kingdom, conferred "for sustained, outstanding achievements in any field of science". The award alternates between the physical sciences or mathematics and the bio ...

, then regarded as the highest international award in the natural sciences, noting that he had been "the first to apply the second law of thermodynamics to the exhaustive discussion of the relation between chemical, electrical and thermal energy and capacity for external work." Gibbs, who remained in New Haven, was represented at the award ceremony by Commander Richardson Clover, the US naval attaché in London.

In his autobiography, mathematician Gian-Carlo Rota

Gian-Carlo Rota (April 27, 1932 – April 18, 1999) was an Italian-American mathematician and philosopher. He spent most of his career at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he worked in combinatorics, functional analysis, proba ...

tells of casually browsing the mathematical stacks of Sterling Library and stumbling on a handwritten mailing list, attached to some of Gibbs's course notes, which listed over two hundred notable scientists of his day, including Poincaré, Boltzmann, David Hilbert

David Hilbert (; ; 23 January 1862 – 14 February 1943) was a German mathematician and philosopher of mathematics and one of the most influential mathematicians of his time.

Hilbert discovered and developed a broad range of fundamental idea ...

, and Ernst Mach

Ernst Waldfried Josef Wenzel Mach ( ; ; 18 February 1838 – 19 February 1916) was an Austrian physicist and philosopher, who contributed to the understanding of the physics of shock waves. The ratio of the speed of a flow or object to that of ...

. From this, Rota concluded that Gibbs's work was better known among the scientific elite of his day than the published material suggests. Lynde Wheeler reproduces that mailing list in an appendix to his biography of Gibbs.Wheeler 1998, appendix IV That Gibbs succeeded in interesting his European correspondents in his work is demonstrated by the fact that his monograph "On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances" was translated into German (then the leading language for chemistry) by Wilhelm Ostwald in 1892 and into French by Henri Louis Le Châtelier in 1899.

Influence

Gibbs's most immediate and obvious influence was on physical chemistry and statistical mechanics, two disciplines which he greatly helped to found. During Gibbs's lifetime, his phase rule was experimentally validated by Dutch chemist H. W. Bakhuis Roozeboom, who showed how to apply it in a variety of situations, thereby assuring it of widespread use. In industrial chemistry, Gibbs's thermodynamics found many applications during the early 20th century, from electrochemistry to the development of theHaber process

The Haber process, also called the Haber–Bosch process, is the main industrial procedure for the ammonia production, production of ammonia. It converts atmospheric nitrogen (N2) to ammonia (NH3) by a reaction with hydrogen (H2) using finely di ...

for the synthesis of ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic chemical compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the chemical formula, formula . A Binary compounds of hydrogen, stable binary hydride and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinctive pu ...

.

When Dutch physicist J. D. van der Waals received the 1910 Nobel Prize