Ivan IV on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (; – ), commonly known as Ivan the Terrible,; ; monastic name:

Ivan Vasilyevich was the first son of Vasili III by his second wife, Elena Glinskaya. Vasili's mother, Sophia Palaiologina, was a

Ivan Vasilyevich was the first son of Vasili III by his second wife, Elena Glinskaya. Vasili's mother, Sophia Palaiologina, was a

Ivan had Saint Basil's Cathedral constructed in Moscow to commemorate the seizure of

Ivan had Saint Basil's Cathedral constructed in Moscow to commemorate the seizure of

The 1560s brought to Russia hardships that led to a dramatic change in Ivan's policies. Russia was devastated by a combination of drought, famine, unsuccessful wars against the

The 1560s brought to Russia hardships that led to a dramatic change in Ivan's policies. Russia was devastated by a combination of drought, famine, unsuccessful wars against the

Casualty figures vary greatly from different sources. The First Pskov Chronicle estimates the number of victims at 60,000.According to the Third Novgorod Chronicle, the massacre lasted for five weeks. Almost every day, 500 or 600 people were killed or drowned. According to the Third Novgorod Chronicle, the massacre lasted for five weeks. The massacre of Novgorod consisted of men, women and children who were tied to sleighs and run into the freezing waters of the

Casualty figures vary greatly from different sources. The First Pskov Chronicle estimates the number of victims at 60,000.According to the Third Novgorod Chronicle, the massacre lasted for five weeks. Almost every day, 500 or 600 people were killed or drowned. According to the Third Novgorod Chronicle, the massacre lasted for five weeks. The massacre of Novgorod consisted of men, women and children who were tied to sleighs and run into the freezing waters of the

In 1547, Hans Schlitte, the agent of Ivan, recruited craftsmen in Germany for work in Russia. However, all of the craftsmen were arrested in

In 1547, Hans Schlitte, the agent of Ivan, recruited craftsmen in Germany for work in Russia. However, all of the craftsmen were arrested in

While Ivan was a child, armies of the

While Ivan was a child, armies of the  In campaigns in 1554 and 1556, Russian troops conquered the Astrakhan Khanate at the mouths of the Volga River, and the new

In campaigns in 1554 and 1556, Russian troops conquered the Astrakhan Khanate at the mouths of the Volga River, and the new

In 1558, Ivan launched the Livonian War in an attempt to gain access to the Baltic Sea and its major trade routes. The war ultimately proved unsuccessful and stretched on for 24 years, engaging the Kingdom of Sweden, the

In 1558, Ivan launched the Livonian War in an attempt to gain access to the Baltic Sea and its major trade routes. The war ultimately proved unsuccessful and stretched on for 24 years, engaging the Kingdom of Sweden, the

In the later years of Ivan's reign, the southern borders of Muscovy were disturbed by Crimean Tatars, mainly to capture slaves. (See also Slavery in the Ottoman Empire.) Khan Devlet I Giray of Crimea repeatedly raided the Moscow region. In 1571, the 40,000-strong Crimean and Turkish army launched a large-scale raid. The ongoing Livonian War left Moscow with a garrison of only 6,000 troops, which could not even delay the Tatar approach. Unresisted, Devlet devastated unprotected towns and villages around Moscow and caused the Fire of Moscow. Historians have estimated the number of casualties of the fire to be 10,000 to 80,000.

To buy peace from Devlet Giray, Ivan was forced to relinquish his claims on Astrakhan for the Crimean Khanate, but the proposed transfer was only a diplomatic maneuver and was never actually completed. The defeat angered Ivan. Between 1571 and 1572, preparations were made upon his orders. In addition to Zasechnaya cherta, innovative fortifications were set beyond the Oka River, which defined the border.

The following year, Devlet launched another raid on Moscow, now with a numerous horde, reinforced by Turkish janissaries equipped with firearms and cannons. The Russian army, led by Prince Mikhail Vorotynsky, was half the size but was experienced and supported by ''streltsy'', equipped with modern firearms and gulyay-gorods. In addition, it was no longer divided into two parts (the and ), unlike during the 1571 defeat. On 27 July, the horde broke through the defensive line along the Oka River and moved towards Moscow. The Russian troops did not have time to intercept it, but the regiment of Prince Khvorostinin vigorously attacked the Tatars from the rear. The Khan stopped only 30 km from Moscow and brought down his entire army back on the Russians, who managed to take up defense near the village of Molodi. After several days of heavy fighting, Mikhail Vorotynsky with the main part of the army flanked the Tatars and dealt a sudden blow on 2 August, and Khvorostinin made a

In the later years of Ivan's reign, the southern borders of Muscovy were disturbed by Crimean Tatars, mainly to capture slaves. (See also Slavery in the Ottoman Empire.) Khan Devlet I Giray of Crimea repeatedly raided the Moscow region. In 1571, the 40,000-strong Crimean and Turkish army launched a large-scale raid. The ongoing Livonian War left Moscow with a garrison of only 6,000 troops, which could not even delay the Tatar approach. Unresisted, Devlet devastated unprotected towns and villages around Moscow and caused the Fire of Moscow. Historians have estimated the number of casualties of the fire to be 10,000 to 80,000.

To buy peace from Devlet Giray, Ivan was forced to relinquish his claims on Astrakhan for the Crimean Khanate, but the proposed transfer was only a diplomatic maneuver and was never actually completed. The defeat angered Ivan. Between 1571 and 1572, preparations were made upon his orders. In addition to Zasechnaya cherta, innovative fortifications were set beyond the Oka River, which defined the border.

The following year, Devlet launched another raid on Moscow, now with a numerous horde, reinforced by Turkish janissaries equipped with firearms and cannons. The Russian army, led by Prince Mikhail Vorotynsky, was half the size but was experienced and supported by ''streltsy'', equipped with modern firearms and gulyay-gorods. In addition, it was no longer divided into two parts (the and ), unlike during the 1571 defeat. On 27 July, the horde broke through the defensive line along the Oka River and moved towards Moscow. The Russian troops did not have time to intercept it, but the regiment of Prince Khvorostinin vigorously attacked the Tatars from the rear. The Khan stopped only 30 km from Moscow and brought down his entire army back on the Russians, who managed to take up defense near the village of Molodi. After several days of heavy fighting, Mikhail Vorotynsky with the main part of the army flanked the Tatars and dealt a sudden blow on 2 August, and Khvorostinin made a

During Ivan's reign, Russia started a large-scale exploration and colonization of

During Ivan's reign, Russia started a large-scale exploration and colonization of

Ivan the Terrible had at least six (possibly eight) wives, although only four of them were recognised by the Church. Three of them were allegedly poisoned by his enemies or by rival aristocratic families who wanted to promote their daughters to be his brides. He also had nine children.

In 1580, his heir, Ivan Ivanovich, married Yelena Sheremeteva from the Sheremetev noble family, which was a rare instance of the daughter of a boyar marrying into the dynasty.

On , Ivan chastised Yelena for being unsuitably dressed, considering her advanced pregnancy, leading to an altercation with his son Ivan Ivanovich. Historians generally believe that Ivan killed his son in a fit of rage, with the argument ending after the elder Ivan fatally struck his son in the head with his pointed staff. Yelena also suffered a miscarriage within hours of the incident. The event is depicted in the famous painting by

Ivan the Terrible had at least six (possibly eight) wives, although only four of them were recognised by the Church. Three of them were allegedly poisoned by his enemies or by rival aristocratic families who wanted to promote their daughters to be his brides. He also had nine children.

In 1580, his heir, Ivan Ivanovich, married Yelena Sheremeteva from the Sheremetev noble family, which was a rare instance of the daughter of a boyar marrying into the dynasty.

On , Ivan chastised Yelena for being unsuitably dressed, considering her advanced pregnancy, leading to an altercation with his son Ivan Ivanovich. Historians generally believe that Ivan killed his son in a fit of rage, with the argument ending after the elder Ivan fatally struck his son in the head with his pointed staff. Yelena also suffered a miscarriage within hours of the incident. The event is depicted in the famous painting by

Ivan was a devoted follower of Orthodox Christianity but in his own specific manner. He placed the most emphasis on defending the divine right of the ruler to unlimited power under God. Some scholars explain the sadistic and brutal deeds of Ivan the Terrible with the religious concepts of the 16th century, which included drowning and roasting people alive or torturing victims with boiling or freezing water, corresponding to the torments of hell. That was consistent with Ivan's view of being God's representative on Earth with a sacred right and duty to punish. He may also have been inspired by the model of Archangel Michael with the idea of divine punishment.

Despite the absolute prohibition of the Church for even the fourth marriage, Ivan had seven wives. Even while his seventh wife was alive, he was negotiating to marry Mary Hastings, a distant relative of Queen Elizabeth I, Elizabeth of England. Polygamy was also prohibited by the Church. Still, Ivan planned to "put his wife away". Ivan freely interfered in church affairs by ousting Metropolitan Philip and ordering him to be killed and accusing of treason and deposing the second-oldest hierarch, Diocese of Novgorod, Novgorod Archbishop Pimen. Many monks were tortured to death during the Massacre of Novgorod.

In the conquered Khanates of Khazan and Astrakhan, Ivan was somewhat tolerant of Islam. This was largely to avoid a conflict with the Ottoman sultan over control of newly conquered Tatar regions. He considered these conquests to be a Christian victory. He was notable for his anti-Semitism. For example, after the capture of Polotsk, all unconverted Jews were ordered to be drowned, despite their role in the city's economy.

Ivan was a devoted follower of Orthodox Christianity but in his own specific manner. He placed the most emphasis on defending the divine right of the ruler to unlimited power under God. Some scholars explain the sadistic and brutal deeds of Ivan the Terrible with the religious concepts of the 16th century, which included drowning and roasting people alive or torturing victims with boiling or freezing water, corresponding to the torments of hell. That was consistent with Ivan's view of being God's representative on Earth with a sacred right and duty to punish. He may also have been inspired by the model of Archangel Michael with the idea of divine punishment.

Despite the absolute prohibition of the Church for even the fourth marriage, Ivan had seven wives. Even while his seventh wife was alive, he was negotiating to marry Mary Hastings, a distant relative of Queen Elizabeth I, Elizabeth of England. Polygamy was also prohibited by the Church. Still, Ivan planned to "put his wife away". Ivan freely interfered in church affairs by ousting Metropolitan Philip and ordering him to be killed and accusing of treason and deposing the second-oldest hierarch, Diocese of Novgorod, Novgorod Archbishop Pimen. Many monks were tortured to death during the Massacre of Novgorod.

In the conquered Khanates of Khazan and Astrakhan, Ivan was somewhat tolerant of Islam. This was largely to avoid a conflict with the Ottoman sultan over control of newly conquered Tatar regions. He considered these conquests to be a Christian victory. He was notable for his anti-Semitism. For example, after the capture of Polotsk, all unconverted Jews were ordered to be drowned, despite their role in the city's economy.

Little is known about Ivan's appearance, as virtually all existing portraits were made after his death and contain uncertain amounts of artist's impression. In 1567, the ambassador Daniel Prinz von Buchau said about Ivan that: "He is very tall. His body is full of strength and quite thick, his large eyes, which constantly run around, observe everything carefully. His beard is red with a slight shade of black, quite long and thick, but like most Russians, he shaves his hair with a razor".

According to :ru:Катырёв-Ростовский, Иван Михайлович, Ivan Katyryov-Rostovsky, the son-in-law of Michael I of Russia, Ivan had an unpleasant face with a long and crooked nose. He was tall and athletically built, with broad shoulders and a narrow waist.

In 1963, the graves of Ivan and his sons were excavated and examined by Soviet scientists. Chemical and structural analysis of his remains disproved earlier suggestions that Ivan suffered from syphilis or that he was poisoned by arsenic or strangled. At the time of his death, he was 178 cm tall (5 ft. 10 in.) and weighed 85–90 kg (187–198 lb.). His body was rather asymmetrical, had a large amount of osteophytes uncharacteristic of his age and contained excessive concentration of mercury. Researchers concluded that Ivan was athletically built in his youth but, in his last years, had developed various bone diseases and could barely move. They attributed the high mercury content in his body to his use of ointments to heal his joints.

Little is known about Ivan's appearance, as virtually all existing portraits were made after his death and contain uncertain amounts of artist's impression. In 1567, the ambassador Daniel Prinz von Buchau said about Ivan that: "He is very tall. His body is full of strength and quite thick, his large eyes, which constantly run around, observe everything carefully. His beard is red with a slight shade of black, quite long and thick, but like most Russians, he shaves his hair with a razor".

According to :ru:Катырёв-Ростовский, Иван Михайлович, Ivan Katyryov-Rostovsky, the son-in-law of Michael I of Russia, Ivan had an unpleasant face with a long and crooked nose. He was tall and athletically built, with broad shoulders and a narrow waist.

In 1963, the graves of Ivan and his sons were excavated and examined by Soviet scientists. Chemical and structural analysis of his remains disproved earlier suggestions that Ivan suffered from syphilis or that he was poisoned by arsenic or strangled. At the time of his death, he was 178 cm tall (5 ft. 10 in.) and weighed 85–90 kg (187–198 lb.). His body was rather asymmetrical, had a large amount of osteophytes uncharacteristic of his age and contained excessive concentration of mercury. Researchers concluded that Ivan was athletically built in his youth but, in his last years, had developed various bone diseases and could barely move. They attributed the high mercury content in his body to his use of ointments to heal his joints.

Ivan completely altered Russia's governmental structure, establishing the character of modern Russian political organisation. Ivan's creation of the ''oprichnina'', answerable only to him, afforded him personal protection and curtailed the traditional powers and rights of the Boyar, boyars. Henceforth, tsarist autocracy and despotism would lie at the heart of the Russian state. Ivan bypassed the ''mestnichestvo'' system and offered positions of power to his supporters among the minor gentry. The empire's local administration combined both locally and centrally appointed officials; the system proved durable and practical and sufficiently flexible to tolerate later modification.#Bogatyrev, Bogatyrev, p. 263.

Ivan's expedition against Poland failed at a military level, but it helped extend Russia's trade, political and cultural links with other European states. Peter the Great built on those connections in his bid to make Russia a major European power. At Ivan's death, the empire encompassed the Caspian to the southwest and Western Siberia to the east. His southern conquests ignited several conflicts with the expansionist Ottoman Empire, whose territories were thus confined to the Balkans and the Black Sea regions.

Ivan's management of Russia's economy proved disastrous, both in his lifetime and afterward. He had inherited a government in debt, and in an effort to raise more revenue for his expansionist wars, he instituted a series of taxes on the peasantry and urban population. Martin (2007) stated: "The reign of Ivan IV the Terrible was, in short, a disaster for Muscovy. (...) his subjects were impoverished, his economic resources depleted, his army weakened, and his realm militarily defeated. (...) By the time Ivan IV the Terrible died in 1584 , Muscovy (...) was on the brink of ruin".

Ivan completely altered Russia's governmental structure, establishing the character of modern Russian political organisation. Ivan's creation of the ''oprichnina'', answerable only to him, afforded him personal protection and curtailed the traditional powers and rights of the Boyar, boyars. Henceforth, tsarist autocracy and despotism would lie at the heart of the Russian state. Ivan bypassed the ''mestnichestvo'' system and offered positions of power to his supporters among the minor gentry. The empire's local administration combined both locally and centrally appointed officials; the system proved durable and practical and sufficiently flexible to tolerate later modification.#Bogatyrev, Bogatyrev, p. 263.

Ivan's expedition against Poland failed at a military level, but it helped extend Russia's trade, political and cultural links with other European states. Peter the Great built on those connections in his bid to make Russia a major European power. At Ivan's death, the empire encompassed the Caspian to the southwest and Western Siberia to the east. His southern conquests ignited several conflicts with the expansionist Ottoman Empire, whose territories were thus confined to the Balkans and the Black Sea regions.

Ivan's management of Russia's economy proved disastrous, both in his lifetime and afterward. He had inherited a government in debt, and in an effort to raise more revenue for his expansionist wars, he instituted a series of taxes on the peasantry and urban population. Martin (2007) stated: "The reign of Ivan IV the Terrible was, in short, a disaster for Muscovy. (...) his subjects were impoverished, his economic resources depleted, his army weakened, and his realm militarily defeated. (...) By the time Ivan IV the Terrible died in 1584 , Muscovy (...) was on the brink of ruin".

Ivan's notorious outbursts and autocratic whims helped characterise the position of tsar as one accountable to no earthly authority but only to God. Tsarist absolutism faced few serious challenges until the 19th century. The earliest and most influential account of his reign prior to 1917 was by the historian Nikolay Karamzin, who described Ivan as a 'tormentor' of his people, particularly from 1560, though even after that date Karamzin believed there was a mix of 'good' and 'evil' in his character. In 1922, the historian Robert Wipper wrote a biography that reassessed Ivan as a monarch "who loved the ordinary people" and praised his agrarian reforms.

In the 1920s, Mikhail Pokrovsky, who dominated the study of history in the Soviet Union, attributed the success of the ''oprichnina'' to their being on the side of the small state owners and townsfolk in a decades-long class struggle against the large landowners, and downgraded Ivan's role to that of the instrument of the emerging Russian bourgeoisie. But in February 1941, the poet Boris Pasternak observantly remarked in a letter to his cousin that "the new cult, openly proselytized, is Ivan the Terrible, the ''Oprichnina'', the brutality." Joseph Stalin, who had read Wipper's biography, had decided that Soviet historians should praise the role of strong leaders, such as Ivan, Alexander Nevsky and Peter the Great, who had strengthened and expanded Russia.

A consequence was that the writer Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy, Alexei Tolstoy began work on a stage version of Ivan's life, and Sergei Eisenstein began what was to be a three-part film tribute to Ivan. Both projects were personally supervised by Stalin, at a time when the Soviet Union was engaged in a war with Nazi Germany. He read the scripts of Tolstoy's play and the first of Eisenstein's films in tandem after the Battle of Kursk in 1943, praised Eisenstein's version but rejected Tolstoy's. It took Tolstoy until 1944 to write a version that satisfied Stalin. Eisenstein's success with ''Ivan the Terrible (1944 film), Ivan the Terrible Part 1'' was not repeated with the follow-up, ''The Boyar's Revolt'', which angered Stalin because it portrayed a man suffering pangs of conscience. Stalin told Eisenstein: "Ivan the Terrible was very cruel. You can show that he was cruel, but you have to show why it was essential to be cruel. One of Ivan the Terrible's mistakes was that he didn't finish off the five major families." The film was suppressed until 1958.

In post-Soviet Russia, there was a campaign to seek the granting of sainthood to Ivan IV, but the Russian Orthodox Church opposed the idea.

The first statue of Ivan the Terrible was officially open in Oryol, Russia, in 2016. Formally, the statue was unveiled in honor of the 450th anniversary of the founding of Oryol, a Russian city of about 310,000 that was established as a fortress to defend Moscow's southern borders. Informally, there was a big political subtext. The opposition thinks that Ivan the Terrible's rehabilitation echoes Stalin's era. The erection of the statue was widely covered in international media like ''The Guardian'', ''The Washington Post'', ''Politico'', and others. The Russian Orthodox Church officially supported the erection of the monument.

Ivan's notorious outbursts and autocratic whims helped characterise the position of tsar as one accountable to no earthly authority but only to God. Tsarist absolutism faced few serious challenges until the 19th century. The earliest and most influential account of his reign prior to 1917 was by the historian Nikolay Karamzin, who described Ivan as a 'tormentor' of his people, particularly from 1560, though even after that date Karamzin believed there was a mix of 'good' and 'evil' in his character. In 1922, the historian Robert Wipper wrote a biography that reassessed Ivan as a monarch "who loved the ordinary people" and praised his agrarian reforms.

In the 1920s, Mikhail Pokrovsky, who dominated the study of history in the Soviet Union, attributed the success of the ''oprichnina'' to their being on the side of the small state owners and townsfolk in a decades-long class struggle against the large landowners, and downgraded Ivan's role to that of the instrument of the emerging Russian bourgeoisie. But in February 1941, the poet Boris Pasternak observantly remarked in a letter to his cousin that "the new cult, openly proselytized, is Ivan the Terrible, the ''Oprichnina'', the brutality." Joseph Stalin, who had read Wipper's biography, had decided that Soviet historians should praise the role of strong leaders, such as Ivan, Alexander Nevsky and Peter the Great, who had strengthened and expanded Russia.

A consequence was that the writer Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy, Alexei Tolstoy began work on a stage version of Ivan's life, and Sergei Eisenstein began what was to be a three-part film tribute to Ivan. Both projects were personally supervised by Stalin, at a time when the Soviet Union was engaged in a war with Nazi Germany. He read the scripts of Tolstoy's play and the first of Eisenstein's films in tandem after the Battle of Kursk in 1943, praised Eisenstein's version but rejected Tolstoy's. It took Tolstoy until 1944 to write a version that satisfied Stalin. Eisenstein's success with ''Ivan the Terrible (1944 film), Ivan the Terrible Part 1'' was not repeated with the follow-up, ''The Boyar's Revolt'', which angered Stalin because it portrayed a man suffering pangs of conscience. Stalin told Eisenstein: "Ivan the Terrible was very cruel. You can show that he was cruel, but you have to show why it was essential to be cruel. One of Ivan the Terrible's mistakes was that he didn't finish off the five major families." The film was suppressed until 1958.

In post-Soviet Russia, there was a campaign to seek the granting of sainthood to Ivan IV, but the Russian Orthodox Church opposed the idea.

The first statue of Ivan the Terrible was officially open in Oryol, Russia, in 2016. Formally, the statue was unveiled in honor of the 450th anniversary of the founding of Oryol, a Russian city of about 310,000 that was established as a fortress to defend Moscow's southern borders. Informally, there was a big political subtext. The opposition thinks that Ivan the Terrible's rehabilitation echoes Stalin's era. The erection of the statue was widely covered in international media like ''The Guardian'', ''The Washington Post'', ''Politico'', and others. The Russian Orthodox Church officially supported the erection of the monument.

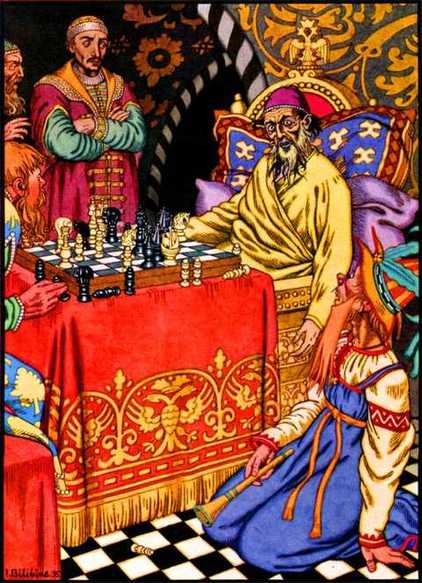

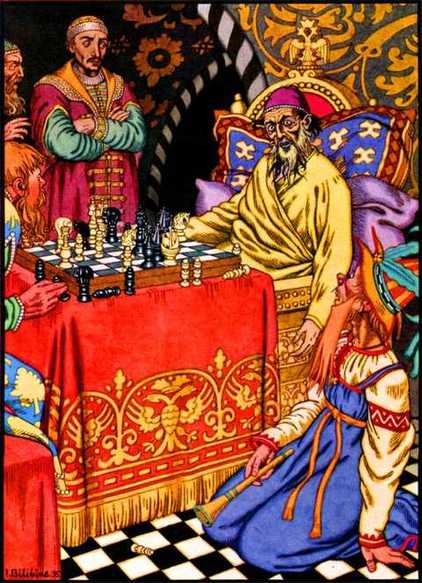

The throne of Ivan the Terrible

Ivan the Terrible with videos, images and translations from the Russian Archives and State Museums

* , versions of a poem by Felicia Hemans. , - , - {{Authority control Ivan the Terrible, 1530 births 1584 deaths 16th-century grand princes of Moscow Antisemitism in Russia Filicides Folk saints Child monarchs from Europe People of the Livonian War Daniilovichi family Tsars of Russia

Jonah

Jonah the son of Amittai or Jonas ( , ) is a Jewish prophet from Gath-hepher in the Northern Kingdom of Israel around the 8th century BCE according to the Hebrew Bible. He is the central figure of the Book of Jonah, one of the minor proph ...

. was Grand Prince of Moscow and all Russia from 1533 to 1547, and the first Tsar and Grand Prince of all Russia from 1547 until his death in 1584. Ivan's reign was characterised by Russia's transformation from a medieval state to a fledgling empire, but at an immense cost to its people and long-term economy.

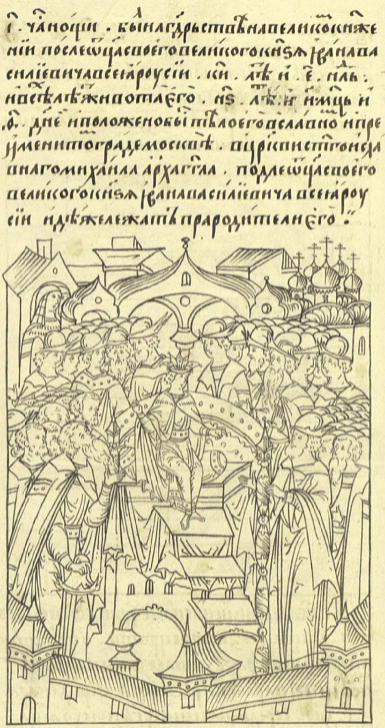

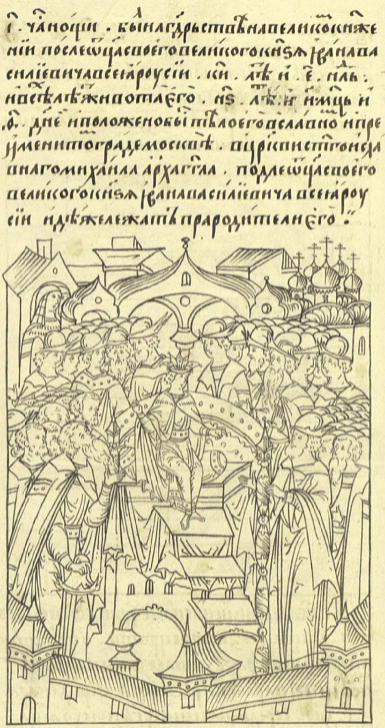

Ivan IV was the eldest son of Vasili III by his second wife Elena Glinskaya, and a grandson of Ivan III. He succeeded his father after his death, when he was three years old. A group of reformers united around the young Ivan, crowning him as tsar

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Euro ...

in 1547 at the age of 16. In the early years of his reign, Ivan ruled with the group of reformers known as the Chosen Council and established the ''Zemsky Sobor

The ''Zemsky Sobor'' ( rus, зе́мский собо́р, p=ˈzʲemskʲɪj sɐˈbor, t=assembly of the land) was a parliament of the Tsardom of Russia's estates of the realm active during the 16th and 17th centuries.

The assembly represented ...

'', a new assembly convened by the tsar. He also revised the legal code

A code of law, also called a law code or legal code, is a systematic collection of statutes. It is a type of legislation that purports to exhaustively cover a complete system of laws or a particular area of law as it existed at the time the co ...

and introduced reforms, including elements of local self-government, as well as establishing the first Russian standing army, the ''streltsy

The streltsy (, ; , ) were the units of Russian firearm infantry from the 16th century to the early 18th century and also a social stratum, from which personnel for streltsy troops were traditionally recruited. They are also collectively kno ...

''. Ivan conquered the khanates of Kazan

Kazan; , IPA: Help:IPA/Tatar, ɑzanis the largest city and capital city, capital of Tatarstan, Russia. The city lies at the confluence of the Volga and the Kazanka (river), Kazanka Rivers, covering an area of , with a population of over 1. ...

and Astrakhan

Astrakhan (, ) is the largest city and administrative centre of Astrakhan Oblast in southern Russia. The city lies on two banks of the Volga, in the upper part of the Volga Delta, on eleven islands of the Caspian Depression, from the Caspian Se ...

, and significantly expanded the territory of Russia.

After he had consolidated his power, Ivan rid himself of the advisers from the Chosen Council and, in an effort to establish a stronghold in the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

, he triggered the Livonian War

The Livonian War (1558–1583) concerned control of Terra Mariana, Old Livonia (in the territory of present-day Estonia and Latvia). The Tsardom of Russia faced a varying coalition of the Denmark–Norway, Dano-Norwegian Realm, the Kingdom ...

of 1558 to 1583, which ravaged Russia and resulted in failure to take control over Livonia

Livonia, known in earlier records as Livland, is a historical region on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. It is named after the Livonians, who lived on the shores of present-day Latvia.

By the end of the 13th century, the name was extende ...

and the loss of Ingria

Ingria (; ; ; ) is a historical region including, and adjacent to, what is now the city of Saint Petersburg in northwestern Russia. The region lies along the southeastern shore of the Gulf of Finland, bordered by Lake Ladoga on the Karelian ...

, but allowed him to establish greater autocratic control over the Russian nobility, which he violently purged using Russia's first political police, the '' oprichniki''. The later years of Ivan's reign were marked by the massacre of Novgorod by the ''oprichniki'' and the burning of Moscow by the Tatars

Tatars ( )Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary are a group of Turkic peoples across Eas ...

. Ivan also pursued cultural improvements, such as importing the first printing press to Russia, and began several processes that would continue for centuries, including deepening connections with other European states, particularly in the Collins English Dictionary are a group of Turkic peoples across Eas ...

England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, fighting wars

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of State (polity), states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or betwe ...

against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, and the conquest of Siberia.

Contemporary sources present disparate accounts of Ivan's complex personality. He was described as intelligent and devout, but also prone to paranoia, rage, and episodic outbreaks of mental instability that worsened with age. Historians generally believe that in a fit of anger, he murdered his eldest son and heir, Ivan Ivanovich; he might also have caused the miscarriage of the latter's unborn child. This left his younger son, the politically ineffectual Feodor Ivanovich, to inherit the throne, a man whose rule and subsequent childless death led to the end of the Rurik dynasty

The Rurik dynasty, also known as the Rurikid or Riurikid dynasty, as well as simply Rurikids or Riurikids, was a noble lineage allegedly founded by the Varangian prince Rurik, who, according to tradition, established himself at Novgorod in the ...

and the beginning of the Time of Troubles

The Time of Troubles (), also known as Smuta (), was a period of political crisis in Tsardom of Russia, Russia which began in 1598 with the death of Feodor I of Russia, Feodor I, the last of the Rurikids, House of Rurik, and ended in 1613 wit ...

.

Nickname

The English word ''terrible'' is usually used to translate the Russian word () in Ivan's epithet, but this is a somewhat archaic translation. The Russian word reflects the older English usage of ''terrible'' as in "inspiring fear or terror; dangerous; powerful" (i.e., similar to modern English ''terrifying'' or ''formidable''). It does not convey the more modern connotations of English ''terrible'' such as "defective" or "evil". According to Edward L. Keenan, Ivan the Terrible's image inpopular culture

Popular culture (also called pop culture or mass culture) is generally recognized by members of a society as a set of cultural practice, practices, beliefs, artistic output (also known as popular art

as a tyrant came from politicised Western travel literature of the f. pop art

F is the sixth letter of the Latin alphabet.

F may also refer to:

Science and technology Mathematics

* F or f, the number 15 (number), 15 in hexadecimal and higher positional systems

* ''p'F'q'', the hypergeometric function

* F-distributi ...

or mass art, sometimes contraste ...Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

era. Anti-Russian propaganda during the Livonian War

The Livonian War (1558–1583) concerned control of Terra Mariana, Old Livonia (in the territory of present-day Estonia and Latvia). The Tsardom of Russia faced a varying coalition of the Denmark–Norway, Dano-Norwegian Realm, the Kingdom ...

portrayed Ivan as a sadistic and oriental despot. Vladimir Dal

Vladimir Ivanovich Dal (, ; 22 November 1801 – 4 October 1872) was a Russians, Russian Lexicography, lexicographer, Multilingualism, speaker of many languages, Turkology, Turkologist, and founding member of the Russian Geographical Society. Du ...

defines specifically in archaic usage and as an epithet for tsars: "courageous, magnificent, magisterial and keeping enemies in fear, but people in obedience". Other translations have also been suggested by modern scholars, including ''formidable'', as well as ''awe-inspiring''.

Early life

Ivan Vasilyevich was the first son of Vasili III by his second wife, Elena Glinskaya. Vasili's mother, Sophia Palaiologina, was a

Ivan Vasilyevich was the first son of Vasili III by his second wife, Elena Glinskaya. Vasili's mother, Sophia Palaiologina, was a Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

princess of the Palaiologos family. She was a daughter of Thomas Palaiologos, the younger brother of the last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos

Constantine XI Dragases Palaiologos or Dragaš Palaeologus (; 8 February 140429 May 1453) was the last reigning List of Byzantine emperors, Byzantine emperor from 23 January 1449 until his death in battle at the fall of Constantinople on 29 M ...

(). Elena's mother

A mother is the female parent of a child. A woman may be considered a mother by virtue of having given birth, by raising a child who may or may not be her biological offspring, or by supplying her ovum for fertilisation in the case of ges ...

was a Serbian princess and her father's family, the Tatar Glinski clan (nobles based in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a sovereign state in northeastern Europe that existed from the 13th century, succeeding the Kingdom of Lithuania, to the late 18th century, when the territory was suppressed during the 1795 Partitions of Poland, ...

), claimed descent both from Orthodox Hungarian nobles and the Mongol ruler Mamai (1335–1380). Born on 25 August, he received the name Ivan in honor of St. John the Baptist

John the Baptist ( – ) was a Jewish preacher active in the area of the Jordan River in the early first century AD. He is also known as Saint John the Forerunner in Eastern Orthodoxy and Oriental Orthodoxy, John the Immerser in some Baptist ...

, the day of whose beheading falls on 29 August. In some texts of that era, it is also occasionally mentioned with the names Titus and Smaragd, in accordance with the tradition of polyonymy among the Rurikids. He was baptized in the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius by Abbot Joasaph (Skripitsyn) and two elders of the Joseph-Volokolamsk Monastery were elected as recipients—the monk Cassian Bossoy and the hegumen Daniel. Tradition says that in honor of the birth of Ivan, the Church of the Ascension was built in Kolomenskoye.

When Ivan was three years old, his father died from an abscess and inflammation on his leg that developed into blood poisoning. The closest contenders to the throne, except for the young Ivan, were the younger brothers of Vasily. Of the six sons of Ivan III, only two remained: Andrey

Andrey (Андрей) is a masculine given name predominantly used in Slavic languages, including Belarusian, Bulgarian, and Russian. The name is derived from the ancient Greek Andreas (Ἀνδρέας), meaning "man" or "warrior".

In Eastern ...

and Yuri. Ivan was proclaimed the grand prince at the request of his father. His mother Elena Glinskaya initially acted as regent, but died in 1538, when Ivan was eight years old; many believe that she was poisoned. The regency then alternated between several feuding boyar families that fought for control. According to his own letters, Ivan, along with his younger brother Yuri, often felt neglected and offended by the mighty boyars from the Shuisky and Belsky families. In a letter to Andrey Kurbsky, Ivan remembered, "My brother Iurii, of blessed memory, and me they brought up like vagrants and children of the poorest. What have I suffered for want of garments and food!" That account has been challenged by the historian Edward Keenan, who doubts the authenticity of the source in which the quotations are found.

On 16 January 1547, at the age of 16, Ivan was crowned at the Cathedral of the Dormition in the Moscow Kremlin. The metropolitan placed on Ivan the signs of royal dignity: the Cross of the Life-Giving Tree, barmas, and the cap of Monomakh; Ivan Vasilyevich was anointed with myrrh

Myrrh (; from an unidentified ancient Semitic language, see '' § Etymology'') is a gum-resin extracted from a few small, thorny tree species of the '' Commiphora'' genus, belonging to the Burseraceae family. Myrrh resin has been used ...

, and then the metropolitan blessed the tsar. He was the first Russian monarch to be crowned the tsar of all Russia, partly imitating his grandfather, Ivan III. Until then, the rulers of Moscow were crowned as grand princes, but Ivan III assumed the title of sovereign of all Russia and used the title of tsar

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Euro ...

in his correspondence with other monarchs. Two weeks after his coronation, Ivan married his first wife, Anastasia Romanovna, a member of the Romanov family, who became the first Russian tsaritsa.

By being crowned tsar, Ivan was sending a message to the world and to Russia that he was now the only supreme ruler of the country, and his will was not to be questioned. According to historian Janet Martin, the new title "symbolized an assumption of powers equivalent and parallel to those held by the former Byzantine caesar and the Tatar khan, both known in Russian sources as tsar. The political effect was to elevate Ivan's position". The new title not only secured the throne but also granted Ivan a new dimension of power that was intimately tied to religion. He was now a "divine" leader appointed to enact God's will, as "church texts described Old Testament kings as 'Tsars' and Christ as the Heavenly Tsar". The newly appointed title was then passed on from generation to generation, and "succeeding Muscovite rulers... benefited from the divine nature of the power of the Russian monarch... crystallized during Ivan's reign".

Like the Habsburgs and other monarchs in Europe, the first Russian tsars adopted mythological genealogies that connected them to Ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

. In '' The Tale of the Princes of Vladimir'', their lineage is traced to Rurik

Rurik (also spelled Rorik, Riurik or Ryurik; ; ; died 879) was a Varangians, Varangian chieftain of the Rus' people, Rus' who, according to tradition, was invited to reign in Veliky Novgorod, Novgorod in the year 862. The ''Primary Chronicle' ...

, the first prince of Novgorod

Veliky Novgorod ( ; , ; ), also known simply as Novgorod (), is the largest city and administrative centre of Novgorod Oblast, Russia. It is one of the oldest cities in Russia, being first mentioned in the 9th century. The city lies along the V ...

in northern Russia, while a certain Prus, an alleged brother of Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

who ruled what would become Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

, is mentioned as a direct ancestor of Rurik. Ivan IV often mentioned his apparent kinship with Augustus, claiming not to be a "Russe" and highlighting his "German" descent from Rurik. Such genealogies served to elevate the position of the Russian monarch in the eyes of his subjects and other European powers, who were also creating mythological ancestors for themselves.

Domestic policy

Despite calamities triggered by the Great Fire of 1547, the early part of Ivan's reign was one of peaceful reforms and modernization. Ivan revised the law code, creating the Sudebnik of 1550, founded astanding army

A standing army is a permanent, often professional, army. It is composed of full-time soldiers who may be either career soldiers or conscripts. It differs from army reserves, who are enrolled for the long term, but activated only during wars ...

(the ), established the (the first Russian parliament of feudal estates) and the council of the nobles (known as the Chosen Council) and confirmed the position of the Church with the Council of the Hundred Chapters (Stoglavy Synod), which unified the rituals and ecclesiastical regulations of the whole country. He introduced local self-government to rural regions, mainly in northeastern Russia, populated by the state peasantry.

In 1553 Ivan suffered a near-fatal illness and was thought not able to recover. While on his presumed deathbed Ivan had asked the boyars to swear an oath of allegiance to his eldest son, an infant at the time. Many boyars refused since they deemed the tsar's health too hopeless for him to survive. This angered Ivan and added to his distrust of the boyars. There followed brutal reprisals and assassinations, including those of Metropolitan Philip and Prince Alexander Gorbatyi-Shuisky.

Ivan ordered in 1553 the establishment of the Moscow Print Yard, and the first printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in whi ...

was introduced to Russia. Several religious books in Russian were printed during the 1550s and 1560s. The new technology provoked discontent among traditional scribes, which led to the Print Yard being burned in an arson attack. The first Russian printers, Ivan Fedorov and Pyotr Mstislavets, were forced to flee from Moscow to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a sovereign state in northeastern Europe that existed from the 13th century, succeeding the Kingdom of Lithuania, to the late 18th century, when the territory was suppressed during the 1795 Partitions of Poland, ...

. Nevertheless, the printing of books resumed from 1568 onwards, with Andronik Timofeevich Nevezha and his son Ivan now heading the Print Yard.

Ivan had Saint Basil's Cathedral constructed in Moscow to commemorate the seizure of

Ivan had Saint Basil's Cathedral constructed in Moscow to commemorate the seizure of Kazan

Kazan; , IPA: Help:IPA/Tatar, ɑzanis the largest city and capital city, capital of Tatarstan, Russia. The city lies at the confluence of the Volga and the Kazanka (river), Kazanka Rivers, covering an area of , with a population of over 1. ...

. There is a legend that he was so impressed with the structure that he had the architect, Postnik Yakovlev, blinded so that he could never design anything as beautiful again. However, in reality Postnik Yakovlev went on to design more churches for Ivan and the walls of the Kazan Kremlin in the early 1560s as well as the chapel over Saint Basil's grave, which was added to Saint Basil's Cathedral in 1588, several years after Ivan's death. Although more than one architect was associated with that name, it is believed that the principal architect is the same person.

Other events of the period include the introduction of the first laws restricting the mobility of the peasants, which would eventually lead to serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

and were instituted during the rule of the future Tsar Boris Godunov in 1597. This cites:

* Platon Vasilievich Pavlov, ''On the Historical Significance of the Reign of Boris Godunov'' (Rus.) (Moscow, 1850)

* Sergyei Mikhailivich Solovev, ''History of Russia'' (Rus.) (2nd ed., vols. vii–viii, St. Petersburg, 1897). (See also Serfdom in Russia.)

The combination of bad harvests, devastation brought by the '' oprichnina'' and Tatar raids, the prolonged war and overpopulation caused a severe social and economic crisis in the second half of Ivan's reign.

The 1560s brought to Russia hardships that led to a dramatic change in Ivan's policies. Russia was devastated by a combination of drought, famine, unsuccessful wars against the

The 1560s brought to Russia hardships that led to a dramatic change in Ivan's policies. Russia was devastated by a combination of drought, famine, unsuccessful wars against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

, Tatar invasions and the sea-trading blockade carried out by the Swedes, the Poles and the Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League was a Middle Ages, medieval commercial and defensive network of merchant guilds and market towns in Central Europe, Central and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Growing from a few Northern Germany, North German towns in the ...

. His first wife, Anastasia Romanovna, died in 1560, which was suspected to be a poisoning. The personal tragedy deeply hurt Ivan and is thought to have affected his personality, if not his mental health. At the same time one of Ivan's advisors, Prince Andrey Kurbsky, defected to the Lithuanians, took command of the Lithuanian troops and devastated the Russian region of Velikiye Luki

Velikiye Luki ( rus, Вели́кие Лу́ки, p=vʲɪˈlʲikʲɪjə ˈlukʲɪ; lit. ''great meanders''. Г. П. Смолицкая. "Топонимический словарь Центральной России". "Армада-� ...

. This series of treacherous acts made Ivan paranoically suspicious of nobility.

On 3 December 1564 Ivan left Moscow for Aleksandrova Sloboda, where he sent two letters in which he announced his abdication

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the Order of succession, succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of ...

because of the alleged embezzlement and treason of the aristocracy and the clergy. The boyar court was unable to rule in Ivan's absence and feared the wrath of the Muscovite citizens. A boyar envoy departed for Aleksandrova Sloboda to beg Ivan to return to the throne.Pavlov, Andrei and Perrie, Maureen (2003) ''Ivan the Terrible (Profiles in Power)''. Harlow, UK: Longman. pp. 112–113. . Ivan agreed to return on condition of being granted absolute power. He demanded the right to condemn and execute traitors and confiscate their estates without interference from the boyar council or church. Ivan decreed the creation of the .

The was a separate territory within the borders of Russia, mostly in the territory of the former Novgorod Republic in the north. Ivan held exclusive power over the territory. The Boyar Council ruled the ('land'), the second division of the state. Ivan also recruited a personal guard known as the , originally numbered 1,000. The were headed by Malyuta Skuratov. One known was the German adventurer Heinrich von Staden. The enjoyed social and economic privileges under the . They owed their allegiance and status to Ivan, not heredity or local bonds.

The first wave of persecutions targeted primarily the princely clans of Russia, notably the influential families of Suzdal. Ivan executed, exiled or forcibly tonsure

Tonsure () is the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a sign of religious devotion or humility. The term originates from the Latin word ' (meaning "clipping" or "shearing") and referred to a specific practice in ...

d prominent members of the boyar clans on questionable accusations of conspiracy. Among those who were executed were the Metropolitan Philip and the prominent warlord Alexander Gorbaty-Shuisky. In 1566 Ivan extended the to eight central districts. Of the 12,000 nobles, 570 became and the rest were expelled.

Under the new political system the were given large estates but, unlike the previous landlords, could not be held accountable for their actions. The men "took virtually all the peasants possessed, forcing them to pay 'in one year as much as heyused to pay in ten. This degree of oppression resulted in increasing cases of peasants fleeing, which in turn reduced overall production. The price of grain increased ten-fold.

Ivan was repentant after the death of his son and his actions with the ', and afterwards, he sent out lists compiling the deaths of his Christian victims killed by the system and asked monasteries to pray for every known one.

Sack of Novgorod

Conditions under the were worsened by the 1570 epidemic, a plague that killed 10,000 people in Novgorod and 600 to 1,000 daily in Moscow. During the grim conditions of the epidemic, a famine and the ongoing Livonian War, Ivan grew suspicious that noblemen of the wealthy city of Novgorod were planning to defect and to place the city under the control of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. A Novgorod citizen, Petr Volynets, warned the tsar about the alleged conspiracy, which modern historians believe not to have been real. In 1570 Ivan ordered the to raid the city. The burned and pillaged Novgorod and the surrounding villages and the city has never regained its former prominence. Casualty figures vary greatly from different sources. The First Pskov Chronicle estimates the number of victims at 60,000.According to the Third Novgorod Chronicle, the massacre lasted for five weeks. Almost every day, 500 or 600 people were killed or drowned. According to the Third Novgorod Chronicle, the massacre lasted for five weeks. The massacre of Novgorod consisted of men, women and children who were tied to sleighs and run into the freezing waters of the

Casualty figures vary greatly from different sources. The First Pskov Chronicle estimates the number of victims at 60,000.According to the Third Novgorod Chronicle, the massacre lasted for five weeks. Almost every day, 500 or 600 people were killed or drowned. According to the Third Novgorod Chronicle, the massacre lasted for five weeks. The massacre of Novgorod consisted of men, women and children who were tied to sleighs and run into the freezing waters of the Volkhov

Volkhov () is an industrial types of inhabited localities in Russia, town and the administrative center of Volkhovsky District in Leningrad Oblast, Russia, located on the river Volkhov (river), Volkhov east of Saint Petersburg, St. Petersbu ...

River, which Ivan ordered on the basis of unproved accusations of treason. He then tortured its inhabitants and killed thousands in a pogrom. The archbishop was also hunted to death. Almost every day, 500 or 600 people were killed, some by drowning, but the official death toll named 1,500 of Novgorod's "big" people (nobility) and mentioned only about the same number of "smaller" people. Many modern researchers estimate the number of victims to range from 2,000 to 3,000 since after the famine and epidemics of the 1560s the population of Novgorod most likely did not exceed 10,000–20,000. Many survivors were deported.

The did not live long after the sack of Novgorod. During the 1571–72 Russo-Crimean War the failed to prove themselves worthy against a regular army. In 1572, Ivan abolished the and disbanded his .

Appointment of Simeon Bekbulatovich

In September or October 1575, Ivan proclaimed Simeon Bekbulatovich, his statesman of Tatar origin, the new grand prince of all Russia. Simeon reigned as a figurehead leader for about a year. According to the English envoy Giles Fletcher the Elder, Simeon acted on Ivan's instructions to confiscate all of the lands that belonged to monasteries, and Ivan pretended to disagree with the decision. When the throne was returned to Ivan in September 1576 he returned some of the confiscated land and kept the rest.Foreign policy

Diplomacy and trade

In 1547, Hans Schlitte, the agent of Ivan, recruited craftsmen in Germany for work in Russia. However, all of the craftsmen were arrested in

In 1547, Hans Schlitte, the agent of Ivan, recruited craftsmen in Germany for work in Russia. However, all of the craftsmen were arrested in Lübeck

Lübeck (; or ; Latin: ), officially the Hanseatic League, Hanseatic City of Lübeck (), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 220,000 inhabitants, it is the second-largest city on the German Baltic Sea, Baltic coast and the second-larg ...

at the request of Poland and Livonia

Livonia, known in earlier records as Livland, is a historical region on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. It is named after the Livonians, who lived on the shores of present-day Latvia.

By the end of the 13th century, the name was extende ...

. The German merchant companies ignored the new port built by Ivan on the River Narva in 1550 and continued to deliver goods in the Baltic ports owned by Livonia. Russia remained isolated from sea trade.

Ivan established close ties with the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from the late 9th century, when it was unified from various Heptarchy, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland to f ...

. Russian–English relations can be traced to 1551, when the Muscovy Company

The Muscovy Company (also called the Russia Company or the Muscovy Trading Company; ) was an English trading company chartered in 1555. It was the first major Chartered company, chartered joint-stock company, the precursor of the type of business ...

was formed by Richard Chancellor

Richard Chancellor ( – ) was an English explorer and navigator; the first to penetrate to the White Sea and establish Anglo-Russian relations, relations with the Tsardom of Russia.

Life

Chancellor, a native of Bristol, was brought up in the ...

, Sebastian Cabot, Sir Hugh Willoughby and several London merchants. In 1553, Chancellor sailed to the White Sea

The White Sea (; Karelian language, Karelian and ; ) is a southern inlet of the Barents Sea located on the northwest coast of Russia. It is surrounded by Karelia to the west, the Kola Peninsula to the north, and the Kanin Peninsula to the nort ...

and continued overland to Moscow, where he visited Ivan's court. Ivan opened up the White Sea and the port of Arkhangelsk

Arkhangelsk (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It lies on both banks of the Northern Dvina near its mouth into the White Sea. The city spreads for over along the ...

to the company and granted it privilege of trading throughout his reign without paying the standard customs fees.

With the use of English merchants, Ivan engaged in a long correspondence with Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

. While the queen focused on commerce, Ivan was more interested in a military alliance. Ivan even proposed to her once, and during his troubled relations with the boyars, he even asked her for a guarantee to be granted asylum in England if his rule was jeopardised.Crankshaw, Edward, ''Russia and Britain'', Collins, ''The Nations and Britain'' series. Elizabeth agreed on the condition that he provide for himself during his potential stay.

Ivan corresponded with overseas Orthodox leaders. In response to a letter of Patriarch Joachim of Alexandria asking him for financial assistance for the Saint Catherine's Monastery

Saint Catherine's Monastery ( , ), officially the Sacred Autonomous Royal Monastery of Saint Catherine of the Holy and God-Trodden Mount Sinai, is a Christian monastery located in the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt. Located at the foot of Mount Sinai ...

, in the Sinai Peninsula

The Sinai Peninsula, or simply Sinai ( ; ; ; ), is a peninsula in Egypt, and the only part of the country located in Asia. It is between the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Red Sea to the south, and is a land bridge between Asia and Afri ...

, which had suffered by the Turks, Ivan sent in 1558 a delegation to Egypt Eyalet by Archdeacon Gennady, who, however, died in Constantinople before he could reach Egypt. From then on, the embassy was headed by Smolensk

Smolensk is a city and the administrative center of Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Dnieper River, west-southwest of Moscow.

First mentioned in 863, it is one of the oldest cities in Russia. It has been a regional capital for most of ...

merchant Vasily Poznyakov, whose delegation visited Alexandria, Cairo and Sinai; brought the patriarch a fur coat and an icon sent by Ivan and left an interesting account of his two-and-a-half years of travels.

Ivan was the first ruler to begin cooperating with the free cossacks on a large scale. Relations were handled through the Posolsky Prikaz diplomatic department; Moscow sent them money and weapons, while tolerating their freedoms, to draw them into an alliance against the Tatars. The first evidence of cooperation surfaces in 1549 when Ivan ordered the Don Cossacks to attack Crimea.

Conquest of Kazan and Astrakhan

While Ivan was a child, armies of the

While Ivan was a child, armies of the Kazan Khanate

The Khanate of Kazan was a Tatars, Tatar state that occupied the territory of the former Volga Bulgaria between 1438 and 1552. The khanate covered contemporary Tatarstan, Mari El, Chuvashia Republic, Chuvashia, Mordovia, and parts of Udmurti ...

repeatedly raided northeastern Russia. In the 1530s, the Crimean khan formed an offensive alliance with Safa Giray of Kazan, his relative. When Safa Giray invaded Russia in December 1540, the Russians used Qasim Tatars to contain him. After his advance was stalled near Murom, Safa Giray was forced to withdraw to his own borders.

The reverses undermined Safa Giray's authority in Kazan. A pro-Russian party, represented by Shahgali, gained enough popular support to make several attempts to take over the Kazan throne. In 1545, Ivan mounted an expedition to the River Volga to show his support for the pro-Russian party.

In 1551, the tsar sent his envoy to the Nogai Horde, and they promised to maintain neutrality during the impending war. The Ar begs and Udmurts submitted to Russian authority as well. In 1551, the wooden fort of Sviyazhsk

Sviyazhsk (; ) is a rural locality (a '' selo'') in the Republic of Tatarstan, Russia, located at the confluence of the Volga and Sviyaga Rivers. It is often referred to as an island since the 1955 construction of the Kuybyshev Reservoir downstr ...

was transported down the Volga from Uglich all the way to Kazan. It was used as the Russian place-of-arms during the decisive campaign of 1552.

On 16 June 1552, Ivan led a strong Russian army towards Kazan. The last siege of the Tatar capital commenced on 30 August. Under the supervision of Prince Alexander Gorbaty-Shuysky, the Russians used battering rams, a siege tower, undermining, and 150 cannons. The Russians also had the advantage of efficient military engineers. The city's water supply was blocked and the walls were breached. Kazan finally fell on 2 October, its fortifications were razed and much of the population massacred. Many Russian prisoners and slaves were released. Ivan celebrated his victory over Kazan by building several churches with oriental features, most famously Saint Basil's Cathedral on Red Square in Moscow. The fall of Kazan was only the beginning of a series of so-called " Cheremis wars". The attempts of the Moscow government to gain a foothold on the Middle Volga kept provoking uprisings of local peoples, which was suppressed only with great difficulty. In 1557, the First Cheremis War ended, and the Bashkirs

The Bashkirs ( , ) or Bashkorts (, ; , ) are a Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group indigenous to Russia. They are concentrated in Bashkortostan, a Republics of Russia, republic of the Russian Federation and in the broader historical region of B ...

accepted Ivan's authority.

In campaigns in 1554 and 1556, Russian troops conquered the Astrakhan Khanate at the mouths of the Volga River, and the new

In campaigns in 1554 and 1556, Russian troops conquered the Astrakhan Khanate at the mouths of the Volga River, and the new Astrakhan

Astrakhan (, ) is the largest city and administrative centre of Astrakhan Oblast in southern Russia. The city lies on two banks of the Volga, in the upper part of the Volga Delta, on eleven islands of the Caspian Depression, from the Caspian Se ...

fortress was built in 1558 by Ivan Vyrodkov to replace the old Tatar capital. The annexation of the Tatar khanates meant the conquest of vast territories, access to large markets and control of the entire length of the Volga River. According to Martin (2007), "the subjugation of the Muslim khanates transformed Muscovy into an empire and fundamentally altered the balance of power on the steppe."

After his conquest of Kazan, Ivan is said to have ordered the crescent, a symbol of Islam, to be placed underneath the Christian cross

The Christian cross, seen as representing the crucifixion of Jesus, is a religious symbol, symbol of Christianity. It is related to the crucifix, a cross that includes a ''corpus'' (a representation of Jesus' body, usually three-dimensional) a ...

on the domes of Orthodox Christian churches.

Russo-Turkish War

In 1568, Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, who was the real power in the administration of theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

under Sultan Selim, initiated the first encounter between the Ottoman Empire and its future northern rival. The results presaged the many disasters to come. A plan to unite the Volga and Don by a canal was detailed in Constantinople. In the summer of 1569, a large force under Kasim Pasha of 1,500 Janissaries, 2,000 Sipahi

The ''sipahi'' ( , ) were professional cavalrymen deployed by the Seljuk Turks and later by the Ottoman Empire. ''Sipahi'' units included the land grant–holding ('' timar'') provincial ''timarli sipahi'', which constituted most of the arm ...

s and a few thousand Azaps and Akıncıs were sent to lay siege to Astrakhan and to begin the canal works while an Ottoman fleet besieged Azov.

In early 1570, Ivan's ambassadors concluded a treaty at Constantinople that restored friendly relations between the sultan and the tsar. The envoys were directed to tell to the sultan: "My Tsar is not an enemy of the Moslem faith. His servant Sain Bulat rules the Khanate of Kassimov; Prince Kaibula in Yuriev, Ibak in Suroshsk, and the Nogai Princes in Romanov.”

Livonian War

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a sovereign state in northeastern Europe that existed from the 13th century, succeeding the Kingdom of Lithuania, to the late 18th century, when the territory was suppressed during the 1795 Partitions of Poland, ...

, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

and the Teutonic Knights

The Teutonic Order is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem was formed to aid Christians on their pilgrimages to t ...

of Livonia. The prolonged war had nearly destroyed the economy, and the ' had thoroughly disrupted the government. Meanwhile, the Union of Lublin

The Union of Lublin (; ) was signed on 1 July 1569 in Lublin, Poland, and created a single state, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, one of the largest countries in Europe at the time. It replaced the personal union of the Crown of the Kingd ...

had united the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a sovereign state in northeastern Europe that existed from the 13th century, succeeding the Kingdom of Lithuania, to the late 18th century, when the territory was suppressed during the 1795 Partitions of Poland, ...

and Kingdom of Poland

The Kingdom of Poland (; Latin: ''Regnum Poloniae'') was a monarchy in Central Europe during the Middle Ages, medieval period from 1025 until 1385.

Background

The West Slavs, West Slavic tribe of Polans (western), Polans who lived in what i ...

, and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth acquired an energetic leader, Stephen Báthory, who was supported by Russia's southern enemy, the Ottoman Empire. Ivan's realm was being squeezed by two of the time's great powers.

After rejecting peace proposals from his enemies, Ivan had found himself in a difficult position by 1579. The displaced refugees fleeing the war compounded the effects of the simultaneous drought, and the exacerbated war engendered epidemics causing much loss of life.

Báthory then launched a series of offensives against Muscovy in the campaign seasons of 1579–81 to try to cut the Kingdom of Livonia from Muscovy. During his first offensive in 1579, he retook Polotsk with 22,000 men. During the second, in 1580, he took Velikie Luki with a 29,000-strong force. Finally, he began the Siege of Pskov in 1581 with a 100,000-strong army. Narva

Narva is a municipality and city in Estonia. It is located in the Ida-Viru County, at the Extreme points of Estonia, eastern extreme point of Estonia, on the west bank of the Narva (river), Narva river which forms the Estonia–Russia border, E ...

, in Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Ru ...

, was reconquered by Sweden in 1581.

Unlike Sweden and Poland, Frederick II of Denmark

Frederick II (1 July 1534 – 4 April 1588) was King of Denmark-Norway, Denmark and Norway and Duke of Duchy of Schleswig, Schleswig and Duchy of Holstein, Holstein from 1559 until his death in 1588.

A member of the House of Oldenburg, Fre ...

had trouble continuing the fight against Muscovy. He came to an agreement with John III of Sweden in 1580 to transfer the Danish titles of Livonia to John III. Muscovy recognised Polish–Lithuanian control of Livonia only in 1582. After Magnus of Livonia, the brother of Frederick II and a former ally of Ivan, died in 1583, Poland invaded his territories in the Duchy of Courland, and Frederick II decided to sell his rights of inheritance. Except for the island of Saaremaa, Denmark had left Livonia by 1585.

Crimean raids

In the later years of Ivan's reign, the southern borders of Muscovy were disturbed by Crimean Tatars, mainly to capture slaves. (See also Slavery in the Ottoman Empire.) Khan Devlet I Giray of Crimea repeatedly raided the Moscow region. In 1571, the 40,000-strong Crimean and Turkish army launched a large-scale raid. The ongoing Livonian War left Moscow with a garrison of only 6,000 troops, which could not even delay the Tatar approach. Unresisted, Devlet devastated unprotected towns and villages around Moscow and caused the Fire of Moscow. Historians have estimated the number of casualties of the fire to be 10,000 to 80,000.

To buy peace from Devlet Giray, Ivan was forced to relinquish his claims on Astrakhan for the Crimean Khanate, but the proposed transfer was only a diplomatic maneuver and was never actually completed. The defeat angered Ivan. Between 1571 and 1572, preparations were made upon his orders. In addition to Zasechnaya cherta, innovative fortifications were set beyond the Oka River, which defined the border.

The following year, Devlet launched another raid on Moscow, now with a numerous horde, reinforced by Turkish janissaries equipped with firearms and cannons. The Russian army, led by Prince Mikhail Vorotynsky, was half the size but was experienced and supported by ''streltsy'', equipped with modern firearms and gulyay-gorods. In addition, it was no longer divided into two parts (the and ), unlike during the 1571 defeat. On 27 July, the horde broke through the defensive line along the Oka River and moved towards Moscow. The Russian troops did not have time to intercept it, but the regiment of Prince Khvorostinin vigorously attacked the Tatars from the rear. The Khan stopped only 30 km from Moscow and brought down his entire army back on the Russians, who managed to take up defense near the village of Molodi. After several days of heavy fighting, Mikhail Vorotynsky with the main part of the army flanked the Tatars and dealt a sudden blow on 2 August, and Khvorostinin made a

In the later years of Ivan's reign, the southern borders of Muscovy were disturbed by Crimean Tatars, mainly to capture slaves. (See also Slavery in the Ottoman Empire.) Khan Devlet I Giray of Crimea repeatedly raided the Moscow region. In 1571, the 40,000-strong Crimean and Turkish army launched a large-scale raid. The ongoing Livonian War left Moscow with a garrison of only 6,000 troops, which could not even delay the Tatar approach. Unresisted, Devlet devastated unprotected towns and villages around Moscow and caused the Fire of Moscow. Historians have estimated the number of casualties of the fire to be 10,000 to 80,000.

To buy peace from Devlet Giray, Ivan was forced to relinquish his claims on Astrakhan for the Crimean Khanate, but the proposed transfer was only a diplomatic maneuver and was never actually completed. The defeat angered Ivan. Between 1571 and 1572, preparations were made upon his orders. In addition to Zasechnaya cherta, innovative fortifications were set beyond the Oka River, which defined the border.

The following year, Devlet launched another raid on Moscow, now with a numerous horde, reinforced by Turkish janissaries equipped with firearms and cannons. The Russian army, led by Prince Mikhail Vorotynsky, was half the size but was experienced and supported by ''streltsy'', equipped with modern firearms and gulyay-gorods. In addition, it was no longer divided into two parts (the and ), unlike during the 1571 defeat. On 27 July, the horde broke through the defensive line along the Oka River and moved towards Moscow. The Russian troops did not have time to intercept it, but the regiment of Prince Khvorostinin vigorously attacked the Tatars from the rear. The Khan stopped only 30 km from Moscow and brought down his entire army back on the Russians, who managed to take up defense near the village of Molodi. After several days of heavy fighting, Mikhail Vorotynsky with the main part of the army flanked the Tatars and dealt a sudden blow on 2 August, and Khvorostinin made a sortie

A sortie (from the French word meaning ''exit'' or from Latin root ''surgere'' meaning to "rise up") is a deployment or dispatch of one military unit, be it an aircraft, ship, or troops, from a strongpoint. The term originated in siege warf ...

from the fortifications. The Tatars were completely defeated and fled. The next year, Ivan, who had sat out in distant Novgorod during the battle, killed Mikhail Vorotynsky.

Conquest of Siberia

During Ivan's reign, Russia started a large-scale exploration and colonization of

During Ivan's reign, Russia started a large-scale exploration and colonization of Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

. In 1555, shortly after the conquest of Kazan, the Siberian khan Yadegar and the Nogai Horde, under Khan Ismail, pledged their allegiance to Ivan in the hope that he would help them against their opponents. However, Yadegar failed to gather the full sum of tribute that he proposed to the tsar and so Ivan did nothing to save his inefficient vassal. In 1563, Yadegar was overthrown and killed by Khan Kuchum, who denied any tribute to Moscow.

In 1558, Ivan gave the Stroganov merchant family the patent for colonising "the abundant region along the Kama River", and, in 1574, lands over the Ural Mountains along the rivers Tura and Tobol. The family also received permission to build forts along the Ob River and the Irtysh River. Around 1577, the Stroganovs engaged the Cossack leader Yermak Timofeyevich to protect their lands from attacks of the Siberian Khan Kuchum.

In 1580, Yermak started his conquest of Siberia. With some 540 Cossacks

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic languages, East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borde ...

, he started to penetrate territories that were tributary to Kuchum. Yermak pressured and persuaded the various family-based tribes to change their loyalties and to become tributaries of Russia. Some agreed voluntarily because they were offered better terms than with Kuchum, but others were forced. He also established distant forts in the newly conquered lands. The campaign was successful, and the Cossacks managed to defeat the Siberian army in the Battle of Chuvash Cape

The Battle of Chuvash Cape (November 5 ulian calendar, O. S. October 26 1582) led to the victory of a Tsardom of Russia, Russian expedition under Yermak Timofeyevich and the fall of Khanate of Sibir and the end of Khan (title), Khan Kuchum' ...

, but Yermak still needed reinforcements. He sent an envoy to Ivan the Terrible with a message that proclaimed Yermak-conquered Siberia to be part of Russia to the dismay of the Stroganovs, who had planned to keep Siberia for themselves. Ivan agreed to reinforce the Cossacks with his streltsy, but the detachment sent to Siberia died of starvation without any benefit. The Cossacks were defeated by the local peoples, Yermak died and the survivors immediately left Siberia. Only in 1586, two years after the death of Ivan, would the Russians manage to gain a foothold in Siberia by founding the city of Tyumen

Tyumen ( ; rus, Тюмень, p=tʲʉˈmʲenʲ, a=Ru-Tyumen.ogg) is the administrative center and largest types of inhabited localities in Russia, city of Tyumen Oblast, Russia. It is situated just east of the Ural Mountains, along the Tura ( ...

.

Personal life

Marriages and children

Ivan the Terrible had at least six (possibly eight) wives, although only four of them were recognised by the Church. Three of them were allegedly poisoned by his enemies or by rival aristocratic families who wanted to promote their daughters to be his brides. He also had nine children.

In 1580, his heir, Ivan Ivanovich, married Yelena Sheremeteva from the Sheremetev noble family, which was a rare instance of the daughter of a boyar marrying into the dynasty.