Italy During World War II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The participation of Italy in the

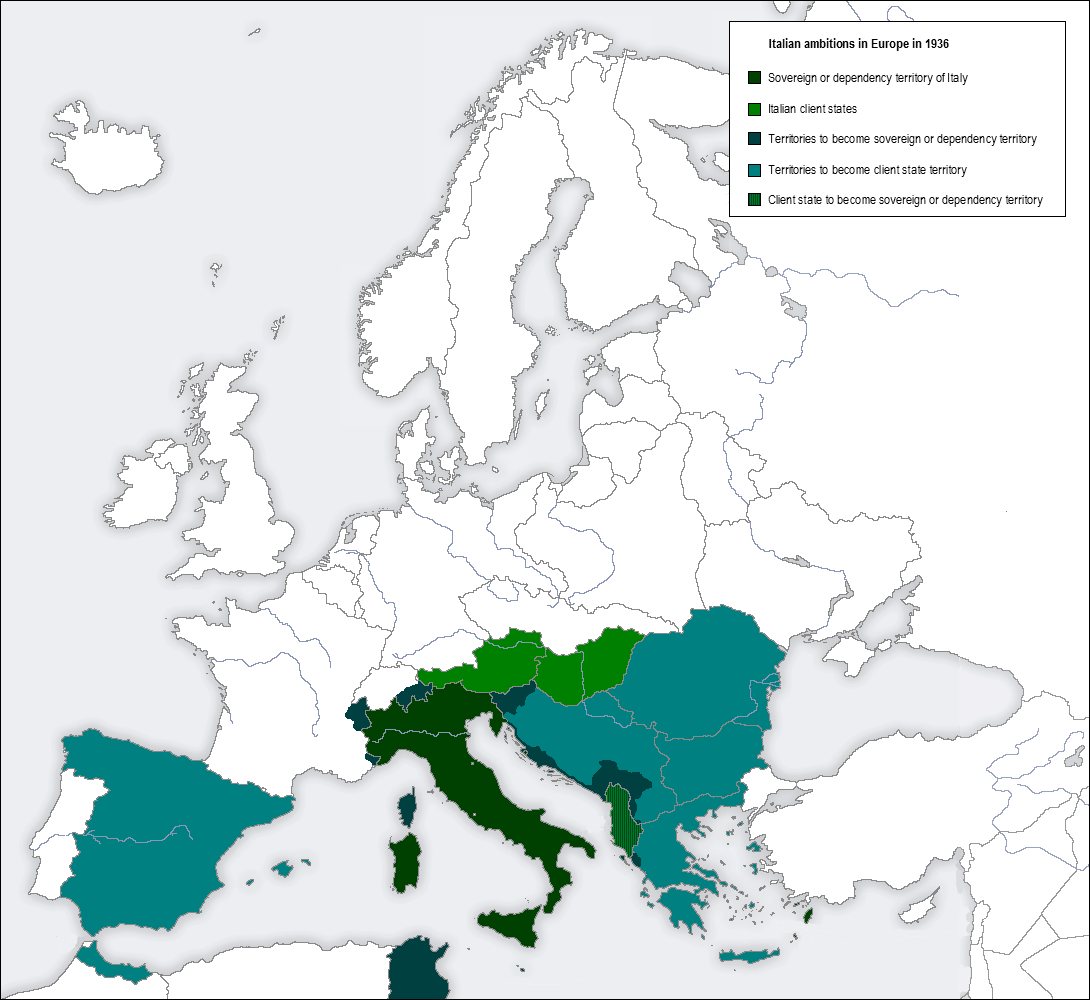

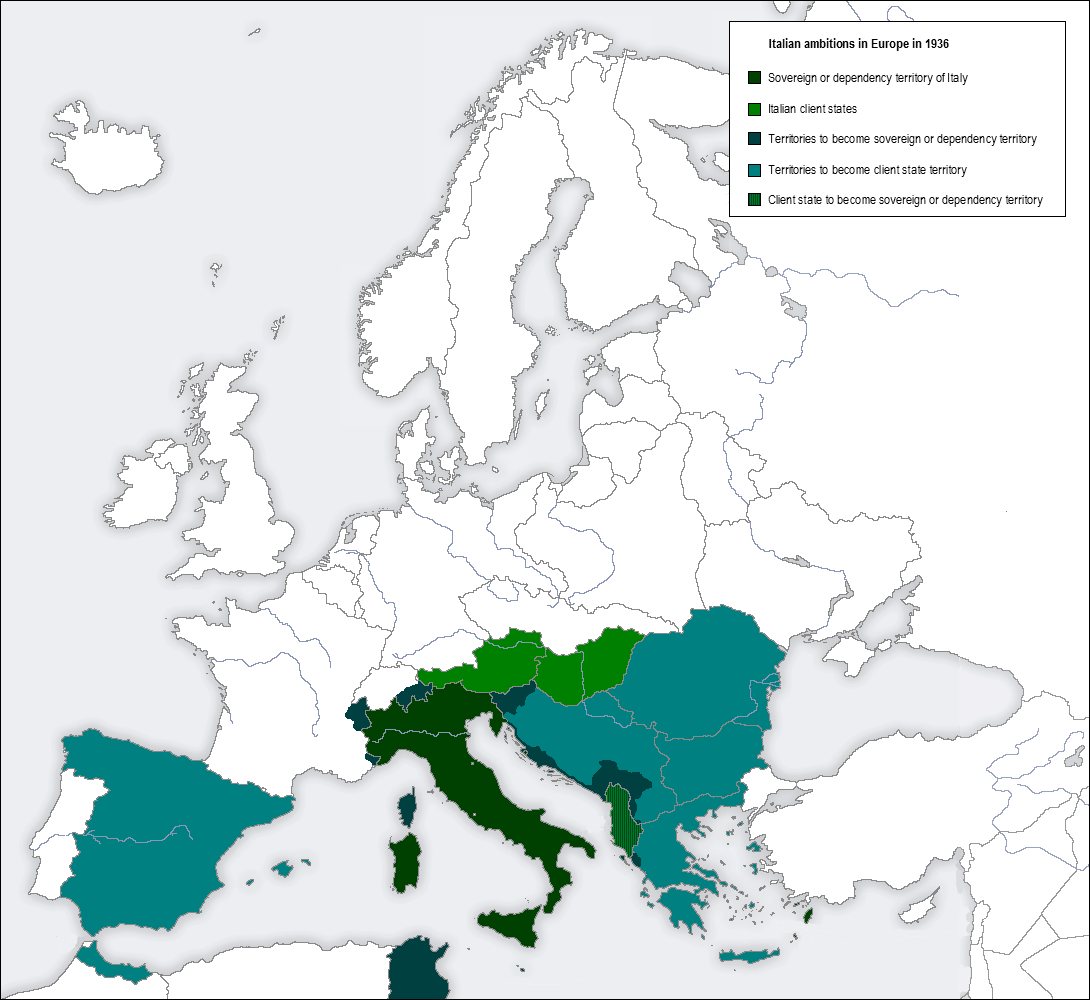

During the late 1920s, the Italian

During the late 1920s, the Italian

In September 1939, Britain imposed a selective blockade of Italy. Coal from Germany, which was shipped out of

In September 1939, Britain imposed a selective blockade of Italy. Coal from Germany, which was shipped out of

The Italian Royal Army (''

The Italian Royal Army (''

On 10 June 1940, as the French government fled to

On 10 June 1940, as the French government fled to

In June 1940, after initial success, the Italian offensive into southern France stalled at the fortified

In June 1940, after initial success, the Italian offensive into southern France stalled at the fortified

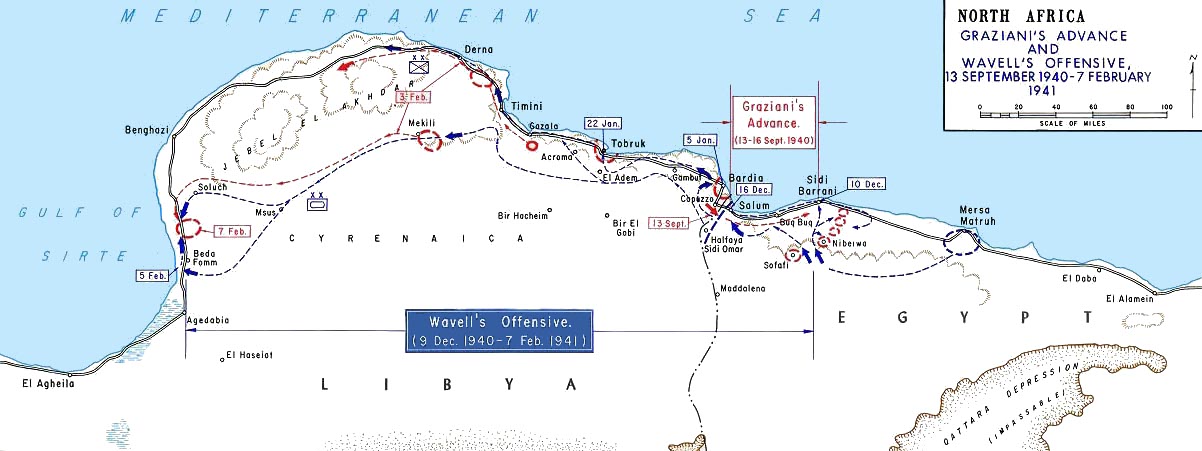

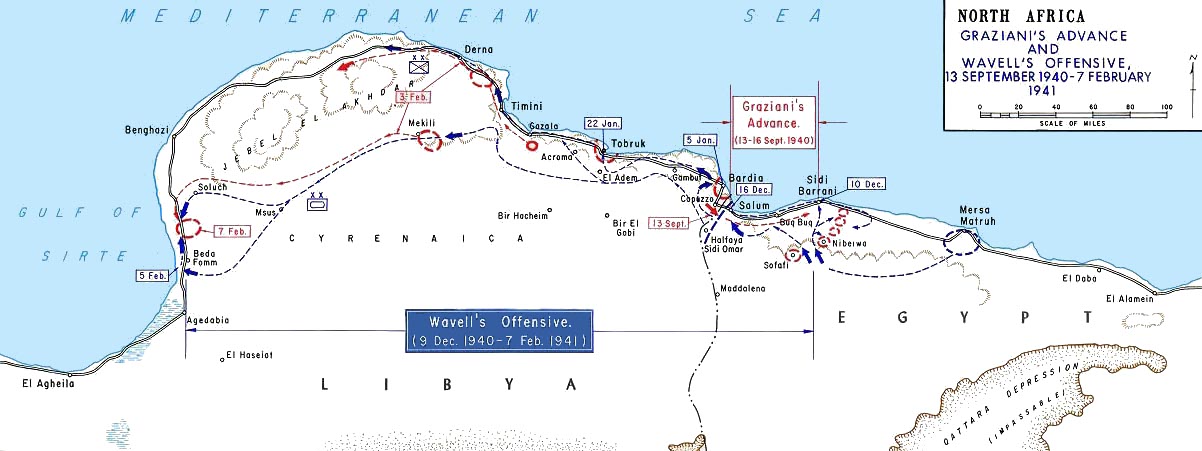

Within a week of Italy's declaration of war on 10 June 1940, the British

Within a week of Italy's declaration of war on 10 June 1940, the British  One officer of Graziani wrote: "We're trying to fight this... as though it were a colonial war... this is a European war... fought with European weapons against a European enemy. We take too little account of this in building our stone forts.... We are not fighting the Ethiopians now." (This was a reference to the

One officer of Graziani wrote: "We're trying to fight this... as though it were a colonial war... this is a European war... fought with European weapons against a European enemy. We take too little account of this in building our stone forts.... We are not fighting the Ethiopians now." (This was a reference to the

In addition to the well-known campaigns in the western desert during 1940, the Italians initiated operations in June 1940 from their

In addition to the well-known campaigns in the western desert during 1940, the Italians initiated operations in June 1940 from their  On 19 January 1941, the expected British counterattack arrived in the shape of the Indian 4th and Indian 5th Infantry Divisions, which made a thrust from Sudan. A supporting attack was made from Kenya by the

On 19 January 1941, the expected British counterattack arrived in the shape of the Indian 4th and Indian 5th Infantry Divisions, which made a thrust from Sudan. A supporting attack was made from Kenya by the

In early 1939, while the world was focused on

In early 1939, while the world was focused on

On 28 October 1940, Italy started the

On 28 October 1940, Italy started the

On 6 April 1941, the ''Wehrmacht'' invasions of both Yugoslavia (

On 6 April 1941, the ''Wehrmacht'' invasions of both Yugoslavia (

In 1940, the Italian Royal Navy (''Regia Marina'') could not match the overall strength of the British Royal Navy in the

In 1940, the Italian Royal Navy (''Regia Marina'') could not match the overall strength of the British Royal Navy in the

In July 1941, around 62,000 Italian troops of the

In July 1941, around 62,000 Italian troops of the

In addition, Italian 'cowardice' did not appear to be more prevalent than the level seen in any army, despite claims of wartime propaganda. Ian Walker wrote:

The vast majority of historians attribute Italian military shortcomings to strategy and equipment. Italian equipment was generally substandard relative to Allied or German armies. More crucially, they lacked suitable quantities of equipment of all kinds and their high command did not take necessary steps to plan for most eventualities. This was compounded by Mussolini's assigning unqualified political favourites to key positions. Mussolini also dramatically overestimated the ability of the Italian military at times, sending them into situations where failure was likely, such as the invasion of Greece.

Historians have long debated why Italy's military and Fascist regime proved ineffective at an activity — war — that was central to their identity. MacGregor Knox explains that this "was first and foremost a failure of Italy's military culture and military institutions." The explanation usually given is that Italy was unprepared for a global conflict as Fascist imperialism had diverted resources to wage wars in Libya, Ethiopia, Spain, and Albania during the 1930s: although successful, these campaigns drained resources that should have been destined to an effective re-armament. Donald Detwiler writes that "Italy's entrance into the war showed very early that her military strength was only a hollow shell. Italy's military failures against France, Greece, Yugoslavia, and in the African Theatres of war shook Italy's new prestige mightily." James Sadkovich surmises that Italian failures were caused by inferior equipment,

In addition, Italian 'cowardice' did not appear to be more prevalent than the level seen in any army, despite claims of wartime propaganda. Ian Walker wrote:

The vast majority of historians attribute Italian military shortcomings to strategy and equipment. Italian equipment was generally substandard relative to Allied or German armies. More crucially, they lacked suitable quantities of equipment of all kinds and their high command did not take necessary steps to plan for most eventualities. This was compounded by Mussolini's assigning unqualified political favourites to key positions. Mussolini also dramatically overestimated the ability of the Italian military at times, sending them into situations where failure was likely, such as the invasion of Greece.

Historians have long debated why Italy's military and Fascist regime proved ineffective at an activity — war — that was central to their identity. MacGregor Knox explains that this "was first and foremost a failure of Italy's military culture and military institutions." The explanation usually given is that Italy was unprepared for a global conflict as Fascist imperialism had diverted resources to wage wars in Libya, Ethiopia, Spain, and Albania during the 1930s: although successful, these campaigns drained resources that should have been destined to an effective re-armament. Donald Detwiler writes that "Italy's entrance into the war showed very early that her military strength was only a hollow shell. Italy's military failures against France, Greece, Yugoslavia, and in the African Theatres of war shook Italy's new prestige mightily." James Sadkovich surmises that Italian failures were caused by inferior equipment,

online

online

a guide to the Italian and English scholarship

ABC-CLIO Schools; Minorities and Women During World War II – "Italian Army"

by A. J. L. Waskey

"Comando Supremo: Italy at War"

Mussolini's War Statement – Declaration of War against USA, 11 December 1941

Armistice with Italy; 3 September 1943

text of the armistice agreement between the Allies and Italy {{DEFAULTSORT:Military History Of Italy During World War Ii *World War II, Military *

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

was characterized by a complex framework of ideology, politics, and diplomacy, while its military actions were often heavily influenced by external factors. Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

joined the war as one of the Axis Powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

in 1940 (as the French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France durin ...

surrendered) with a plan to concentrate Italian forces on a major offensive against the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

in Africa and the Middle East, known as the "parallel war", while expecting the collapse of British forces in the European theatre

The European theatre of World War II was one of the two main theatres of combat during World War II, taking place from September 1939 to May 1945. The Allied powers (including the United Kingdom, the United States, the Soviet Union and Franc ...

. The Italians bombed Mandatory Palestine, invaded Egypt and occupied British Somaliland with initial success. As the war carried on and German and Japanese actions in 1941 led to the entry of the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, respectively, into the war, the Italian plan of forcing Britain to agree to a negotiated peace settlement was foiled.MacGregor Knox. Mussolini unleashed, 1939–1941: Politics and Strategy in Fascist Italy's Last War. Edition of 1999. Cambridge, England, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999. pp. 122–123.

The Italian dictator Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

was aware that Fascist Italy was not ready for a long conflict, as its resources were reduced by successful but costly pre-war conflicts: the pacification of Libya

The Second Italo-Senussi War, also referred to as the pacification of Libya, was a conflict that occurred during the Italian colonization of Libya between Italian military forces (composed mainly by colonial troops from Libya, Eritrea, and S ...

(which was undergoing Italian settlement), intervention in Spain (where a friendly fascist regime had been installed), and the invasions of Ethiopia and Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

. However, imperial ambitions of the Fascist regime, which aspired to restore the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

(the ''Mare Nostrum

In the Roman Empire, () was a term that referred to the Mediterranean Sea. Meaning "Our Sea" in Latin, it denoted the body of water in the context of borders and policy; Ancient Rome, Rome remains the only state in history to have controlled th ...

'') resulted in Mussolini keeping Italy in the war, albeit as a country that was increasingly dependent upon German military support as in Greece and North Africa following the British counterattack

A counterattack is a tactic employed in response to an attack, with the term originating in "Military exercise, war games". The general objective is to negate or thwart the advantage gained by the enemy during attack, while the specific objecti ...

.

With the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia

The invasion of Yugoslavia, also known as the April War or Operation 25, was a Nazi Germany, German-led attack on the Kingdom of Yugoslavia by the Axis powers which began on 6 April 1941 during World War II. The order for the invasion was put fo ...

and the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

, Italy annexed Ljubljana

{{Infobox settlement

, name = Ljubljana

, official_name =

, settlement_type = Capital city

, image_skyline = {{multiple image

, border = infobox

, perrow = 1/2/2/1

, total_widt ...

, Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

and Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

. Puppet regimes were also established in Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

and Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, which were occupied by Italian forces. Following Vichy France

Vichy France (; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was a French rump state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II, established as a result of the French capitulation after the Battle of France, ...

's collapse and the Case Anton

Case Anton () was the military occupation of Vichy France carried out by Germany and Italy in November 1942. It marked the end of the Vichy regime as a nominally independent state and the disbanding of its army (the severely-limited '' Armisti ...

, Italy occupied the French territories of Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

and Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

. Italian forces had also achieved victories against insurgents in Yugoslavia and in Montenegro, and Italo-German forces had occupied parts of British-held Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

on their push to El-Alamein

El Alamein (, ) is a town in the northern Matrouh Governorate of Egypt. Located on the Mediterranean Sea, it lies west of Alexandria and northwest of Cairo. The town is located on the site of the ancient city Antiphrai which was built by the ...

after their victory at Gazala

Gazala, or ʿAyn al-Ġazāla ( ), is a small Libyan village near the coast in the northeastern portion of the country. It is located west of Tobruk.

History

In the late 1930s (during the Libya as Italian colony, Italian occupation of Libya), th ...

.

However, Italy's conquests were always heavily contested, both by various insurgencies (most prominently the Greek resistance and Yugoslav partisans

The Yugoslav Partisans,Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian language, Macedonian, and Slovene language, Slovene: , officially the National Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia sh-Latn-Cyrl, Narodnooslobodilačka vojska i partizanski odr ...

) and Allied military forces, which waged the Battle of the Mediterranean

The Battle of the Mediterranean was the name given to the naval campaign fought in the Mediterranean Sea during World War II, from 10 June 1940 to 2 May 1945.

For the most part, the campaign was fought between the Kingdom of Italy, Italian Reg ...

throughout and beyond Italy's participation. The country's imperial overstretch (opening multiple fronts in Africa, the Balkans, Eastern Europe, and the Mediterranean) ultimately resulted in its defeat in the war, as the Italian empire collapsed after decisive defeats in the Eastern European

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountains, and ...

and North African

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

campaigns. In July 1943, following the Allied invasion of Sicily

The Allied invasion of Sicily, also known as the Battle of Sicily and Operation Husky, was a major campaign of World War II in which the Allies of World War II, Allied forces invaded the island of Sicily in July 1943 and took it from the Axis p ...

, Mussolini was arrested by order of King Victor Emmanuel III

Victor Emmanuel III (; 11 November 1869 – 28 December 1947) was King of Italy from 29 July 1900 until his abdication on 9 May 1946. A member of the House of Savoy, he also reigned as Emperor of Ethiopia from 1936 to 1941 and King of the Albani ...

. Under Mussolini's successor Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino ( , ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regim ...

, Italy signed the Armistice of Cassibile

The Armistice of Cassibile ( Italian: ''Armistizio di Cassibile'') was an armistice that was signed on 3 September 1943 by Italy and the Allies, marking the end of hostilities between Italy and the Allies during World War II. It was made public ...

with the Allies on 3 September 1943. This was announced on 8 September 1943, with Germany invading and occupying much of Italy and its previously occupied and annexed territories. Mussolini would be rescued from captivity a week later by German forces.

On 13 October 1943, the Kingdom of Italy officially became a co-belligerent of the Allies and formally declared war on its former Axis partner Germany. The northern half of the country was occupied by the Germans with the cooperation of Italian fascists, who formed a collaborationist puppet state (soldiers

A soldier is a person who is a member of an army. A soldier can be a conscripted or volunteer enlisted person, a non-commissioned officer, a warrant officer, or an officer.

Etymology

The word ''soldier'' derives from the Middle English word ...

, police

The police are Law enforcement organization, a constituted body of Law enforcement officer, people empowered by a State (polity), state with the aim of Law enforcement, enforcing the law and protecting the Public order policing, public order ...

, and militia recruited for the Axis); the south was still controlled by monarchist forces, which fought for the Allied cause as the Italian Co-Belligerent Army

The Italian Co-belligerent Army (Italian: ''Esercito Cobelligerante Italiano''), or Army of the South (''Esercito del Sud''), were names applied to various of the now former Royal Italian Army during the period when it fought alongside the Alli ...

and Italian resistance movement

The Italian Resistance ( ), or simply ''La'' , consisted of all the Italian resistance groups who fought the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationists of the Italian Social Republic during the Second World War in Italy ...

partisans (many of them former Royal Italian Army soldiers) of disparate political ideologies operated all over Italy. Unlike Germany and Japan, no war crime

A war crime is a violation of the laws of war that gives rise to individual criminal responsibility for actions by combatants in action, such as intentionally killing civilians or intentionally killing prisoners of war, torture, taking hostage ...

s tribunals were held for Italian military and political leaders, though the Italian resistance summarily executed

In civil and military jurisprudence, summary execution is the putting to death of a person accused of a crime without the benefit of a free and fair trial. The term results from the legal concept of summary justice to punish a summary offense, a ...

some political members at the end of the war, including Mussolini on 28 April 1945.

Background

Imperial ambitions

During the late 1920s, the Italian

During the late 1920s, the Italian Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

spoke with increasing urgency about imperial expansion, arguing that Italy needed an outlet for its " surplus population" and that it would therefore be in the best interests of other countries to aid in this expansion. The immediate aspiration of the regime was political "hegemony in the Mediterranean–Danubian–Balkan region", more grandiosely Mussolini imagined the conquest "of an empire stretching from the Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea and separates Europe from Africa.

The two continents are separated by 7.7 nautical miles (14.2 kilometers, 8.9 miles) at its narrowest point. Fe ...

to the Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz ( ''Tangeh-ye Hormoz'' , ''Maḍīq Hurmuz'') is a strait between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. It provides the only sea passage from the Persian Gulf to the open ocean and is one of the world's most strategica ...

". Balkan and Mediterranean hegemony was predicated by ancient Roman

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

dominance in the same regions. There were designs for a protectorate over Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

and for the annexation of Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

, as well as economic and military control of Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

and Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

. The regime also sought to establish protective patron–client relationships with Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

, Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

, and Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

, which all lay on the outside edges of its European sphere of influence. Although it was not among his publicly proclaimed aims, Mussolini wished to challenge the supremacy of Britain and France in the Mediterranean Sea, which was considered strategically vital, since the Mediterranean was Italy's only conduit to the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

and Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

s.

In 1935, Italy initiated the Second Italo-Ethiopian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression waged by Fascist Italy, Italy against Ethiopian Empire, Ethiopia, which lasted from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethiopia it is oft ...

, "a nineteenth-century colonial campaign waged out of due time". The campaign gave rise to optimistic talk on raising a native Ethiopian army "to help conquer" Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan ( ') was a condominium (international law), condominium of the United Kingdom and Kingdom of Egypt, Egypt between 1899 and 1956, corresponding mostly to the territory of present-day South Sudan and Sudan. Legally, sovereig ...

. The war also marked a shift towards a more aggressive Italian foreign policy and also "exposed hevulnerabilities" of the British and French. This in turn created the opportunity Mussolini needed to begin to realize his imperial goals. In 1936, the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

broke out. From the beginning, Italy played an important role in the conflict. Their military contribution was so vast, that it played a decisive role in the victory of the rebel forces led by Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (born Francisco Paulino Hermenegildo Teódulo Franco Bahamonde; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general and dictator who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces i ...

. Mussolini had engaged in "a full-scale external war" due to the insinuation of future Spanish subservience to the Italian Empire, and as a way of placing the country on a war footing and creating "a warrior culture". The aftermath of the war in Ethiopia saw a reconciliation of German-Italian relations following years of a previously strained relationship, resulting in the signing of a treaty of mutual interest in October 1936. Mussolini referred to this treaty as the creation of a Berlin-Rome Axis, which Europe would revolve around. The treaty was the result of increasing dependence on German coal following League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

sanctions, similar policies between the two countries over the conflict in Spain, and German sympathy towards Italy following European backlash to the Ethiopian War. The aftermath of the treaty saw the increasing ties between Italy and Germany, and Mussolini falling under Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

's influence from which "he never escaped".

In October 1938, in the aftermath of the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement was reached in Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, the United Kingdom, the French Third Republic, French Republic, and the Kingdom of Italy. The agreement provided for the Occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–194 ...

, Italy demanded concessions from France. These included a free port

A free-trade zone (FTZ) is a class of special economic zone. It is a geographic area where goods may be imported, stored, handled, manufactured, or reconfigured and re-exported under specific customs regulation and generally not subject to ...

at Djibouti

Djibouti, officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by Somalia to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea in the north, and the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden to the east. The country has an area ...

, control of the Addis Ababa-Djibouti railroad

The Ethio-Djibouti Railway (, C.D.E.; ) is a metre gauge railway in the Horn of Africa that once connected Addis Ababa to the port city of Djibouti. The operating company was also known as the Ethio-Djibouti Railways. The railway was built in ...

, Italian participation in the management of Suez Canal Company

Suez (, , , ) is a seaport city with a population of about 800,000 in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez on the Red Sea, near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal. It is the capital and largest city of the ...

, some form of French-Italian condominium

A condominium (or condo for short) is an ownership regime in which a building (or group of buildings) is divided into multiple units that are either each separately owned, or owned in common with exclusive rights of occupation by individual own ...

over French Tunisia

The French protectorate of Tunisia (; '), officially the Regency of Tunis () and commonly referred to as simply French Tunisia, was established in 1881, during the French colonial empire era, and lasted until Tunisian independence in 1956.

Th ...

, and the preservation of Italian culture on Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

with no French assimilation of the people. The French refused the demands, believing the true Italian intention was the territorial acquisition of Nice

Nice ( ; ) is a city in and the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative city limits, with a population of nearly one millionForeign Minister

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and relations, diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral r ...

Galeazzo Ciano

Gian Galeazzo Ciano, 2nd Count of Cortellazzo and Buccari ( , ; 18 March 1903 – 11 January 1944), was an Italian diplomat and politician who served as Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Foreign Minister in the government of his father-in-law ...

addressed the Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourb ...

on the "natural aspirations of the Italian people" and was met with shouts of "Nice

Nice ( ; ) is a city in and the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative city limits, with a population of nearly one millionSavoy

Savoy (; ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps. Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south and west and to the Aosta Vall ...

! Tunisia! Djibouti! Malta!" Later that day, Mussolini addressed the Fascist Grand Council

The Grand Council of Fascism (, also translated "Fascist Grand Council") was the main body of Mussolini's Fascist regime in Italy, which held and applied great power to control the institutions of government. It was created as a body of the N ...

"on the subject of what he called the immediate goals of 'Fascist dynamism'." These were Albania; Tunisia; Corsica; the Ticino

Ticino ( ), sometimes Tessin (), officially the Republic and Canton of Ticino or less formally the Canton of Ticino, is one of the Canton of Switzerland, 26 cantons forming the Switzerland, Swiss Confederation. It is composed of eight districts ...

, a canton of Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

; and all "French territory east of the River Var", including Nice, but not Savoy.

Beginning in 1939 Mussolini often voiced his contention that Italy required uncontested access to the world's oceans and shipping lanes to ensure its national sovereignty. On 4 February 1939, Mussolini addressed the Grand Council in a closed session. He delivered a long speech on international affairs and the goals of his foreign policy, "which bears comparison with Hitler's notorious disposition, minuted by colonel Hossbach". He began by claiming that the freedom of a country is proportional to the strength of its navy. This was followed by "the familiar lament that Italy was a prisoner in the Mediterranean". He called Corsica, Tunisia, Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

, and Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

"the bars of this prison", and described Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

and Suez as the prison guards. To break British control, her bases on Cyprus, Gibraltar, Malta, and in Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

(controlling the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

) would have to be neutralized. On 31 March, Mussolini stated that "Italy will not truly be an independent nation so long as she has Corsica, Bizerta

Bizerte (, ) is the capital and largest city of Bizerte Governorate in northern Tunisia. It is the northernmost city in Africa, located north of the capital Tunis. It is also known as the last town to remain under French control after the re ...

, Malta as the bars of her Mediterranean prison and Gibraltar and Suez as the walls." Fascist foreign policy took for granted that the democracies—Britain and France—would someday need to be faced down. Through armed conquest Italian North Africa

Libya (; ) was a colony of Italy located in North Africa, in what is now modern Libya, between 1934 and 1943. It was formed from the unification of the colonies of Cyrenaica and Tripolitania, which had been Italian possessions since 1911.

Fro ...

and Italian East Africa

Italian East Africa (, A.O.I.) was a short-lived colonial possession of Fascist Italy from 1936 to 1941 in the Horn of Africa. It was established following the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, which led to the military occupation of the Ethiopian ...

—separated by the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan—would be linked, and the Mediterranean prison destroyed. Then, Italy would be able to march "either to the Indian Ocean through the Sudan and Abyssinia, or to the Atlantic by way of French North Africa".

As early as September 1938, the Italian military had drawn up plans to invade Albania. On 7 April, Italian forces landed in the country and within three days had occupied the majority of the country. Albania represented a territory Italy could acquire for "'living space' to ease its overpopulation" as well as the foothold needed to launch other expansionist conflicts in the Balkans. On 22 May 1939, Italy and Germany signed the Pact of Steel

The Pact of Steel (, ), formally known as the Pact of Friendship and Alliance between Germany and Italy (, ), was a military and political alliance between Germany and Italy, signed in 1939.

The pact was initially drafted as a tripartite milita ...

joining both countries in a military alliance. The pact was the culmination of German-Italian relations from 1936 and was not defensive in nature. Rather, the pact was designed for a "joint war against France and Britain", although the Italian hierarchy held the understanding that such a war would not take place for several years. However, despite the Italian impression, the pact made no reference to such a period of peace and the Germans proceeded with their plans to invade Poland.

Industrial strength

Mussolini's Under-Secretary for War Production, Carlo Favagrossa, had estimated that Italy could not possibly be prepared for major military operations until at least October 1942. This had been made clear during the Italo-German negotiations for the Pact of Steel, whereby it was stipulated that neither signatory was to make war without the other earlier than 1943. Although considered agreat power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

, the Italian industrial sector was relatively weak compared to other Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

an major powers. Italian industry did not equal more than 15% of that of France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

or of Britain in militarily critical areas such as automobile

A car, or an automobile, is a motor vehicle with wheels. Most definitions of cars state that they run primarily on roads, Car seat, seat one to eight people, have four wheels, and mainly transport private transport#Personal transport, peopl ...

production: the number of automobiles in Italy before the war was around 374,000, in comparison to around 2,500,000 in Britain and France. The lack of a stronger automotive industry made it difficult for Italy to mechanize its military. Italy still had a predominantly agricultural-based economy, with demographics more akin to a developing country

A developing country is a sovereign state with a less-developed industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to developed countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. There is also no clear agreeme ...

(high illiteracy, poverty, rapid population growth and a high proportion of adolescents) and a proportion of GNP derived from industry less than that of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

, Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

and Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

, in addition to the other great powers. In terms of strategic material

Strategic material is any sort of raw material that is important to an individual's or organization's strategic plan and supply chain management. Lack of supply of strategic materials may leave an organization or government vulnerable to disrup ...

s, in 1940, Italy produced 4.4 megatonne

The tonne ( or ; symbol: t) is a unit of mass equal to 1,000 kilograms. It is a non-SI unit accepted for use with SI. It is also referred to as a metric ton in the United States to distinguish it from the non-metric units of the s ...

s (Mt) of coal, 0.01 Mt of crude oil, 1.2 Mt of iron ore and 2.1 Mt of steel. By comparison, Great Britain produced 224.3 Mt of coal, 11.9 Mt of crude oil, 17.7 Mt of iron ore, and 13.0 Mt of steel and Germany produced 364.8 Mt of coal, 8.0 Mt of crude oil, 29.5 Mt of iron ore and 21.5 Mt of steel. Most raw material needs could be fulfilled only through importation, and no effort was made to stockpile key materials before the entry into war. Approximately one quarter of the ships of Italy's merchant fleet were in allied ports at the outbreak of hostilities, and, given no forewarning, were immediately impounded.

Economy

Between 1936 and 1939, Italy had supplied the SpanishNationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

forces, fighting under Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (born Francisco Paulino Hermenegildo Teódulo Franco Bahamonde; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general and dictator who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces i ...

during the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

, with large number of weapons and supplies practically free.Walker (2003), p. 17 In addition to weapons, the ''Corpo Truppe Volontarie

The Corps of Volunteer Troops () was a Fascist Italian expeditionary force of military volunteers, which was sent to Spain to support the Nationalist forces under General Francisco Franco against the Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil ...

'' ("Corps of Volunteer Troops") had also been dispatched to fight for Franco. The financial cost of the war was between 6 and 8.5 billion lire, approximately 14 to 20 per cent of the country's annual expenditure. Adding to these problems was Italy's extreme debt position. When Benito Mussolini took office, in 1921, the government debt was 93 billion lire, un-repayable in the short to medium term. Only two years later this debt had increased to 405 billion lire.

In September 1939, Britain imposed a selective blockade of Italy. Coal from Germany, which was shipped out of

In September 1939, Britain imposed a selective blockade of Italy. Coal from Germany, which was shipped out of Rotterdam

Rotterdam ( , ; ; ) is the second-largest List of cities in the Netherlands by province, city in the Netherlands after the national capital of Amsterdam. It is in the Provinces of the Netherlands, province of South Holland, part of the North S ...

, was declared contraband. The Germans promised to keep up shipments by train, over the Alps, and Britain offered to supply all of Italy's needs in exchange for Italian armaments. The Italians could not agree to the latter terms without shattering their alliance with Germany. On 2 February 1940, however, Mussolini approved a draft contract with the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

to provide 400 Caproni

Caproni, also known as ''Società de Agostini e Caproni'' and ''Società Caproni e Comitti'', was an Italian aircraft manufacturer. Its main base of operations was at Taliedo, near Linate Airport, on the outskirts of Milan.

Founded by Giova ...

aircraft, yet scrapped the deal on 8 February. British intelligence officer Francis Rodd believed that Mussolini was convinced to reverse policy by German pressure in the week of 2–8 February, a view shared by the British ambassador in Rome, Percy Loraine

Sir Percy Lyham Loraine, 12th Baronet, (5 November 1880 – 23 May 1961) was a British diplomat. He was British High Commissioner to Egypt from 1929 to 1933, British Ambassador to Turkey from 1933 to 1939 and British Ambassador to Italy from 1 ...

. On 1 March, the British announced that they would block all coal exports from Rotterdam to Italy. Italian coal was one of the most discussed issues in diplomatic circles in the spring of 1940. In April, Britain began strengthening the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between ...

to enforce the blockade. Despite French uncertainty, Britain rejected concessions to Italy so as not to "create an impression of weakness". Germany supplied Italy with about one million tons of coal a month beginning in the spring of 1940, an amount that exceeded even Mussolini's demand of August 1939 that Italy receive six million tons of coal for its first twelve months of war.

Military

The Italian Royal Army (''

The Italian Royal Army (''Regio Esercito

The Royal Italian Army () (RE) was the land force of the Kingdom of Italy, established with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy. During the 19th century Italy started to unify into one country, and in 1861 Manfredo Fanti signed a decree c ...

'') was comparatively depleted and weak at the beginning of the war. Italian tanks were of poor quality and radios few in number. The bulk of Italian artillery

Artillery consists of ranged weapons that launch Ammunition, munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, and l ...

dated to World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. The primary fighter of the Italian Royal Air Force (''Regia Aeronautica

The Royal Italian Air Force (''Regia Aeronautica Italiana'') (RAI) was the air force of the Kingdom of Italy. It was established as a service independent of the Regio Esercito, Royal Italian Army from 1923 until 1946. In 1946, the monarchy was ...

'') was the Fiat CR.42 Falco

The Fiat CR.42 ''Falco'' (Falcon, plural: ''Falchi'') is a single-seat sesquiplane fighter developed and produced by Italian aircraft manufacturer Fiat Aviazione. It served primarily in the Italian in the 1930s and during the Second World War. ...

, which, though an advanced biplane

A biplane is a fixed-wing aircraft with two main wings stacked one above the other. The first powered, controlled aeroplane to fly, the Wright Flyer, used a biplane wing arrangement, as did many aircraft in the early years of aviation. While ...

with excellent performance, was technically outclassed by monoplane

A monoplane is a fixed-wing aircraft configuration with a single mainplane, in contrast to a biplane or other types of multiplanes, which have multiple wings.

A monoplane has inherently the highest efficiency and lowest drag of any wing con ...

fighters of other nations. Of the Regia Aeronautica's approximately 1,760 aircraft, only 900 could be considered in any way combat-worthy. The Italian Royal Navy (''Regia Marina

The , ) (RM) or Royal Italian Navy was the navy of the Kingdom of Italy () from 1861 to 1946. In 1946, with the birth of the Italian Republic (''Repubblica Italiana''), the changed its name to '' Marina Militare'' ("Military Navy").

Origin ...

'') had several modern battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

s but no aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering carrier-based aircraft, shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the ...

s.Bierman & Smith (2002), pp. 13–14

Italian authorities were acutely aware of the need to modernize and were taking steps to meet the requirements of their own relatively advanced tactical principles.Sadkovich (1991) pp. 287–291 Almost 40% of the 1939 budget was allocated for military spending. Recognizing the Navy's need for close air support, the decision was made to build carriers. Three series of modern fighters, capable of meeting the best allied planes on equal terms, were in development, with a few hundred of each eventually being produced. The Carro Armato P40 tank, roughly equivalent to the M4 Sherman

The M4 Sherman, officially medium tank, M4, was the medium tank most widely used by the United States and Western Allies in World War II. The M4 Sherman proved to be reliable, relatively cheap to produce, and available in great numbers. I ...

and Panzer IV

The IV (Pz.Kpfw. IV), commonly known as the Panzer IV, is a German medium tank developed in the late 1930s and used extensively during the Second World War. Its ordnance inventory designation was Sd.Kfz. 161.

The Panzer IV was the most numer ...

medium tanks, was designed in 1940 (though no prototype was produced until 1942 and manufacture could not commence before the Armistice, owing in part to the lack of sufficiently powerful engines, which were themselves undergoing a development push; total Italian tank production for the war – about 3,500 – was less than the number of tanks used by Germany in its invasion of France). The Italians were pioneers in the use of self-propelled guns, both in close support and anti-tank roles. Their 75/46 fixed AA/AT gun, 75/32 gun, 90/53 AA/AT gun (an equally deadly but less famous peer of the German 88/55), 47/32 AT gun, and the 20 mm AA autocannon were effective, modern weapons. Also of note were the AB 41

The Autoblindo 40, 41 and 43 (abbreviated AB 40, 41 and 43) were Italian armoured cars produced by Fiat-Ansaldo and which saw service mainly during World War II. Most ''autoblinde'' were armed with a 20 mm Breda 35 autocannon and a coaxi ...

and the Camionetta AS 42 armoured cars, which were regarded as excellent vehicles of their type. None of these developments, however, precluded the fact that the bulk of equipment was obsolete and poor. The relatively weak economy, lack of suitable raw materials and consequent inability to produce sufficient quantities of armaments and supplies were thus the key material reasons for Italian military failure.

On paper, Italy had one of the world's largest armies, but the reality was dramatically different. According to the estimates of Bierman and Smith, the Italian regular army could field only about 200,000 troops at the war's beginning. Irrespective of the attempts to modernize, the majority of Italian army personnel were lightly armed infantry lacking sufficient motor transport. Not enough money was budgeted to train the men in the services, such that the bulk of personnel received much of their training at the front, too late to be of use.Walker (2003) p. 23 Air units had not been trained to operate with the naval fleet and the majority of ships had been built for fleet actions, rather than the convoy protection duties in which they were primarily employed during the war. In any event, a critical lack of fuel kept naval activities to a minimum.

Senior leadership was also a problem. Mussolini personally assumed control of all three individual military service ministries with the intention of influencing detailed planning. ''Comando Supremo

''Comando Supremo'' (Supreme Command) was the highest command echelon of the Italian Armed Forces between June 1941 and May 1945. Its predecessor, the ''Stato Maggiore Generale'' (General Staff), was a purely advisory body with no direct control ...

'' (the Italian High Command) consisted of only a small complement of staff that could do little more than inform the individual service commands of Mussolini's intentions, after which it was up to the individual service commands to develop proper plans and execution.Walker (2003) p. 20 The result was that there was no central direction for operations; the three military services tended to work independently, focusing only on their fields, with little inter-service cooperation. Pay discrepancies existed for personnel who were of equal rank, but from different units.

Outbreak of the Second World War

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

's invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

on 1 September 1939, marked the beginning of World War II. Despite being an Axis power

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Germany, Kingdom of Italy ...

, Italy remained non-belligerent

A non-belligerent is a person, a state, or other organization that does not fight in a given conflict. The term is often used to describe a country that does not take part militarily in a war.

A non-belligerent state differs from a neutral one ...

until June 1940.

Decision to intervene

Following the German conquest of Poland, Mussolini hesitated to enter the war. General SirArchibald Wavell

Field Marshal Archibald Percival Wavell, 1st Earl Wavell, (5 May 1883 – 24 May 1950) was a senior officer of the British Army. He served in the Second Boer War, the Bazar Valley Campaign and the First World War, during which he was wounded ...

, the head of Middle East Command

Middle East Command, later Middle East Land Forces, was a British Army Command established prior to the Second World War in Egypt. Its primary role was to command British land forces and co-ordinate with the relevant naval and air commands to ...

, correctly predicted that Mussolini's pride would ultimately cause him to enter the war. Wavell would compare Mussolini's situation to that of someone at the top of a diving board: "I think he must do something. If he cannot make a graceful dive, he will at least have to jump in somehow; he can hardly put on his dressing-gown and walk down the stairs again."

Initially, the entry into the war appeared to be political opportunism though there was some provocation. The French and British, for their part had caused Italy a long list of grievances since during WWI through the extraction of political and economic concessions and the blockading of imports. Aware of Italy's material and planning deficiencies leading up to World War II, and believing that Italy's entry into the war on the side of Germany was inevitable, the English blockaded German coal imports from 1 March 1940 in an attempt to bring Italian industry to a standstill.O'Hara (2009) p. 3 The British and the French then began amassing their naval fleets (to a twelve-to-two superiority in capital ships over the Regia Marina) both in preparation and provocation. They thought wrongly that Italy could be knocked out early, underestimating its determination. Prior to this, from 10 September 1939, the Italians made several attempts to intermediate peace. While Hitler was open to it, the French were not responsive and the British only invited the Italians to change sides. For Mussolini, the risks of staying out of the war were becoming greater than those for entering, which led to a lack of consistency in planning, with principal objectives and enemies being changed with little regard for the consequences. Mussolini was well aware of the military and material deficiencies but thought the war would be over soon and did not expect to do much fighting.

Italy enters the war: June 1940

On 10 June 1940, as the French government fled to

On 10 June 1940, as the French government fled to Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( ; ; Gascon language, Gascon ; ) is a city on the river Garonne in the Gironde Departments of France, department, southwestern France. A port city, it is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the Prefectures in F ...

during the German invasion, declaring Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

an open city

In war, an open city is a settlement which has announced it has abandoned all defensive efforts, generally in the event of the imminent capture of the city to avoid destruction. Once a city has declared itself open, the opposing military will ...

, Mussolini felt the conflict would soon end and declared war on Britain and France. As he said to the Army's Chief-of-Staff, Marshal Badoglio:

Mussolini had the immediate war aim of expanding the Italian colonies in North Africa by taking land from the British and French colonies.

About Mussolini's declaration of war in France, President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

of the United States said:

The Italian entry into the war opened up new fronts in North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

and the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

. After Italy entered the war, pressure from Nazi Germany led to the internment in the Campagna concentration camp

Campagna internment camp, located in Campagna, a town near Salerno, Italy, Salerno in Southern Italy, was an internment camp for Jews and foreigners established by Benito Mussolini in 1940.

The first internees were 430 men captured in differe ...

of some of Italy's Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

refugee

A refugee, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), is a person "forced to flee their own country and seek safety in another country. They are unable to return to their own country because of feared persecution as ...

s.

Invasion of France

In June 1940, after initial success, the Italian offensive into southern France stalled at the fortified

In June 1940, after initial success, the Italian offensive into southern France stalled at the fortified Alpine Line

The Alpine Line () or Little Maginot Line (French: ''Petite Ligne Maginot'') was the component of the Maginot Line that defended the southeastern portion of France. In contrast to the main line in the northeastern portion of France, the Alpine Line ...

. On 24 June 1940, France surrendered to Germany. Italy occupied a swath of French territory along the Franco-Italian border. During this operation, Italian casualties amounted to 1,247 men dead or missing and 2,631 wounded. A further 2,151 Italians were hospitalised due to frostbite

Frostbite is a skin injury that occurs when someone is exposed to extremely low temperatures, causing the freezing of the skin or other tissues, commonly affecting the fingers, toes, nose, ears, cheeks and chin areas. Most often, frostbite occ ...

.

Late in the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain () was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defended the United Kingdom (UK) against large-scale attacks by Nazi Germany's air force ...

, Italy contributed an expeditionary force, the Corpo Aereo Italiano

The ''Corpo Aereo Italiano'' (literally, "Italian Air Corps"), or CAI, was an Expeditionary warfare, expeditionary force from the Italian ''Regia Aeronautica'' (Italian Royal Air Force) that participated in the Battle of Britain and the Blitz in ...

, which took part in the Blitz

The Blitz (English: "flash") was a Nazi Germany, German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom, for eight months, from 7 September 1940 to 11 May 1941, during the Second World War.

Towards the end of the Battle of Britain in 1940, a co ...

from October 1940 until April 1941, at which time the last elements of the force were withdrawn.

In November 1942, the Italian Royal Army occupied south-eastern Vichy France

Vichy France (; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was a French rump state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II, established as a result of the French capitulation after the Battle of France, ...

and Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

as part of Case Anton

Case Anton () was the military occupation of Vichy France carried out by Germany and Italy in November 1942. It marked the end of the Vichy regime as a nominally independent state and the disbanding of its army (the severely-limited '' Armisti ...

. From December 1942, Italian military government of French departments east of the Rhône River

The Rhône ( , ; Occitan: ''Ròse''; Arpitan: ''Rôno'') is a major river in France and Switzerland, rising in the Alps and flowing west and south through Lake Geneva and Southeastern France before discharging into the Mediterranean Sea (Gulf ...

was established, and continued until September 1943, when Italy quit the war. This had the effect of providing a '' de facto'' temporary haven for French Jews fleeing the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

. In January 1943 the Italians refused to cooperate with the Nazis in rounding up Jews living in the occupied zone of France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

under their control and in March prevented the Nazis from deporting Jews in their zone. German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich-Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German Nazi politician and diplomat who served as Minister for Foreign Affairs (Germany), Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945. ...

complained to Mussolini that "Italian military circles... lack a proper understanding of the Jewish question."

The Italian Navy

The Italian Navy (; abbreviated as MM) is one of the four branches of Italian Armed Forces and was formed in 1946 from what remained of the ''Regia Marina'' (Royal Navy) after World War II. , the Italian Navy had a strength of 30,923 active per ...

established a submarine base at Bordeaux, code named BETASOM

BETASOM (an Italian language acronym of ''Bordeaux Sommergibile'' or ''Sommergibili'') was a submarine base established at Bordeaux, France by the '' Regia Marina'' during the Second World War. From this base, Italian submarines participated in t ...

, and thirty-two Italian submarines participated in the Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allies of World War II, ...

. Plans to attack the harbour of New York City with CA class midget submarines in 1943 were disrupted when the submarine converted to carry out the attack, the , was sunk in May 1943. The armistice put a stop to further planning.

North Africa

Invasion of Egypt

Within a week of Italy's declaration of war on 10 June 1940, the British

Within a week of Italy's declaration of war on 10 June 1940, the British 11th Hussars

The 11th Hussars (Prince Albert's Own) was a cavalry regiment of the British Army established in 1715. It saw service for three centuries including the First World War and Second World War but then amalgamated with the 10th Royal Hussars (Pri ...

had seized Fort Capuzzo

Fort Capuzzo () was a fort in the colony of Italian Libya, near the Libya–Egypt border, next to the Italian Frontier Wire. The () ran south from Bardia to Fort Capuzzo, inland, west of Sollum, then east across the Egyptian frontier to the ...

in Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

. In an ambush east of Bardia

Bardia, also El Burdi or Bardiyah ( or ) is a Mediterranean seaport in the Butnan District of eastern Libya, located near the border with Egypt. It is also occasionally called ''Bórdi Slemán''.

The name Bardia is deeply rooted in the ancient ...

, the British captured the Italian 10th Army Engineer-in-Chief, General Lastucci. On 28 June Marshal Italo Balbo

Italo Balbo (6 June 1896 – 28 June 1940) was an Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Italian fascist politician and Blackshirts' leader who served as Italy's Marshal of the Air Force, Governor-General of Italian Libya and Commander-in-Chief of Italian ...

, the Governor-General of Libya, was killed by friendly fire

In military terminology, friendly fire or fratricide is an attack by belligerent or neutral forces on friendly troops while attempting to attack enemy or hostile targets. Examples include misidentifying the target as hostile, cross-fire while ...

while landing in Tobruk

Tobruk ( ; ; ) is a port city on Libya's eastern Mediterranean coast, near the border with Egypt. It is the capital of the Butnan District (formerly Tobruk District) and has a population of 120,000 (2011 est.)."Tobruk" (history), ''Encyclop� ...

. Mussolini ordered Balbo's replacement, General Rodolfo Graziani

Rodolfo Graziani, 1st Marquis of Neghelli ( , ; 11 August 1882 – 11 January 1955), was an Italian military officer in the Kingdom of Italy's Royal Italian Army, Royal Army, primarily noted for his campaigns in Africa before and during World Wa ...

, to launch an attack into Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

immediately. Graziani complained to Mussolini that his forces were not properly equipped for such an operation, and that an attack into Egypt could not possibly succeed; nevertheless, Mussolini ordered him to proceed. On 13 September, elements of the 10th Army retook Fort Capuzzo and crossed the border into Egypt. Lightly opposed, they advanced about to Sidi Barrani

Sidi Barrani ( ) is a town in Egypt, near the Mediterranean Sea, about east of the Egypt–Libya border, and around from Tobruk, Libya.

Named after Sidi es-Saadi el Barrani, a Senussi sheikh who was a head of its Zawiya, the village ...

, where they stopped and began entrenching themselves in a series of fortified camps.

At this time, the British had only 36,000 troops available (out of about 100,000 under Middle Eastern command) to defend Egypt, against 236,000 Italian troops. The Italians, however, were not concentrated in one location. They were divided between the 5th army in the west and the 10th army in the east and thus spread out from the Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

n border in western Libya to Sidi Barrani in Egypt. At Sidi Barrani, Graziani, unaware of the British lack of numerical strength, planned to build fortifications and stock them with provisions, ammunition

Ammunition, also known as ammo, is the material fired, scattered, dropped, or detonated from any weapon or weapon system. The term includes both expendable weapons (e.g., bombs, missiles, grenades, land mines), and the component parts of oth ...

, and fuel

A fuel is any material that can be made to react with other substances so that it releases energy as thermal energy or to be used for work (physics), work. The concept was originally applied solely to those materials capable of releasing chem ...

, establish a water pipeline, and extend the via Balbia to that location, which was where the road to Alexandria began.Bauer (2000), p. 95 This task was being obstructed by British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

attacks on Italian supply ships in the Mediterranean. At this stage Italian losses remained minimal, but the efficiency of the British Royal Navy would improve as the war went on. Mussolini was fiercely disappointed with Graziani's sluggishness. However, according to Bauer he had only himself to blame, as he had withheld the trucks, armaments, and supplies that Graziani had deemed necessary for success. Wavell was hoping to see the Italians overextend themselves before his intended counter at Marsa Matruh.

One officer of Graziani wrote: "We're trying to fight this... as though it were a colonial war... this is a European war... fought with European weapons against a European enemy. We take too little account of this in building our stone forts.... We are not fighting the Ethiopians now." (This was a reference to the

One officer of Graziani wrote: "We're trying to fight this... as though it were a colonial war... this is a European war... fought with European weapons against a European enemy. We take too little account of this in building our stone forts.... We are not fighting the Ethiopians now." (This was a reference to the Second Italo-Abyssinian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression waged by Italy against Ethiopia, which lasted from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethiopia it is often referred to simply as the Ita ...

where Italian forces had fought against a poorly equipped opponent.) Balbo had said "Our light tanks, already old and armed only with machine guns, are completely out-classed. The machine guns of the British armoured cars pepper them with bullets which easily pierce their armour."

Italian forces around Sidi Barrani had severe weaknesses in their deployment. Their five main fortifications were placed too far apart to allow mutual support against an attacking force, and the areas between were weakly patrolled. The absence of motorised transport did not allow for rapid reorganisation, if needed. The rocky terrain had prevented an anti-tank ditch from being dug and there were too few mines and 47 mm anti-tank guns to repel an armoured advance.Bauer (2000), p. 113 By the summer of 1941, the Italians in North Africa had regrouped, retrained and rearmed into a much more effective fighting force, one that proved to be much harder for the British to overcome in encounters from 1941 to 1943.

''Afrika Korps'' intervention and final defeat

"''The German soldier has impressed the world, the Italian Bersagliere has impressed the German soldier''", praise towards Italian soldiers attributed to Erwin Rommel on a plaque at the Italian War Memorial at El Alamein On 8 December 1940, the British launched Operation Compass. Planned as an extended raid, it resulted in a force of British, Indian, and Australian troops cutting off the Italian 10th Army. Pressing the British advantage home, GeneralRichard O'Connor

General (United Kingdom), General Sir Richard Nugent O'Connor, (21 August 1889 – 17 June 1981) was a senior British Army Officer (armed forces), officer who fought in both the First World War, First and Second World Wars, and commanded the ...

succeeded in reaching El Agheila

El Agheila ( ) is a coastal city at the southern end of the Gulf of Sidra and Mediterranean Sea in far western Cyrenaica, Libya. In 1988 it was placed in Ajdabiya District; remaining there until 1995. It was removed from Ajdabiya District in 1995 ...

, deep in Libya (an advance of ) and taking some 130,000 prisoners. The Allies nearly destroyed the 10th Army, and seemed on the point of sweeping the Italians out of Libya altogether. Winston Churchill, however, directed the advance be stopped, initially because of supply problems and because of a new Italian offensive that had gained ground in Albania, and ordered troops dispatched to defend Greece. Weeks later the first troops of the German ''Afrika Korps

The German Africa Corps (, ; DAK), commonly known as Afrika Korps, was the German expeditionary force in Africa during the North African campaign of World War II. First sent as a holding force to shore up the Italian defense of its Africa ...