The occupation of Greece by the

Axis Powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

() began in April 1941 after

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

invaded the

Kingdom of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece (, Romanization, romanized: ''Vasíleion tis Elládos'', pronounced ) was the Greece, Greek Nation state, nation-state established in 1832 and was the successor state to the First Hellenic Republic. It was internationally ...

in order to assist its ally,

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, in their

ongoing war that was initiated in October 1940, having encountered major strategical difficulties. Following

the conquest of

Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

, the entirety of Greece was occupied starting in June 1941. The occupation of the mainland lasted until Germany and its ally

Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

withdrew under

Allied pressure in early October 1944, with Crete and some other

Aegean Islands being surrendered to the Allies by German garrisons in May and June 1945, after the end of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

in Europe.

The term Katochi in Greek means ''to possess'' or ''to have control over goods''. It is used to refer to the occupation of Greece by Germany and the Axis Powers. This terminology reflects not only the military occupation but also the economic exploitation of Greece by Germany during that period. The use of "Katochi" underscores the notion of domination and control, highlighting how Greece was subjected to both military and financial subjugation under Axis occupation.

Overview

Fascist Italy had initially declared war and invaded Greece in October 1940, but had been pushed back by the

Hellenic Army

The Hellenic Army (, sometimes abbreviated as ΕΣ), formed in 1828, is the army, land force of Greece. The term Names of the Greeks, '' Hellenic'' is the endogenous synonym for ''Greek''. The Hellenic Army is the largest of the three branches ...

into neighbouring

Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

, which at the time was an

Italian protectorate. Nazi Germany intervened on its ally's behalf in southern Europe. While most of the Hellenic Army was located on the Albanian front lines to defend against Italian counter-attacks, a rapid German ''

Blitzkrieg

''Blitzkrieg'(Lightning/Flash Warfare)'' is a word used to describe a combined arms surprise attack, using a rapid, overwhelming force concentration that may consist of armored and motorized or mechanized infantry formations, together with ...

'' campaign took place from April to June 1941, resulting in Greece being defeated and occupied. The Greek government

went into exile, and an

Axis collaborationist government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

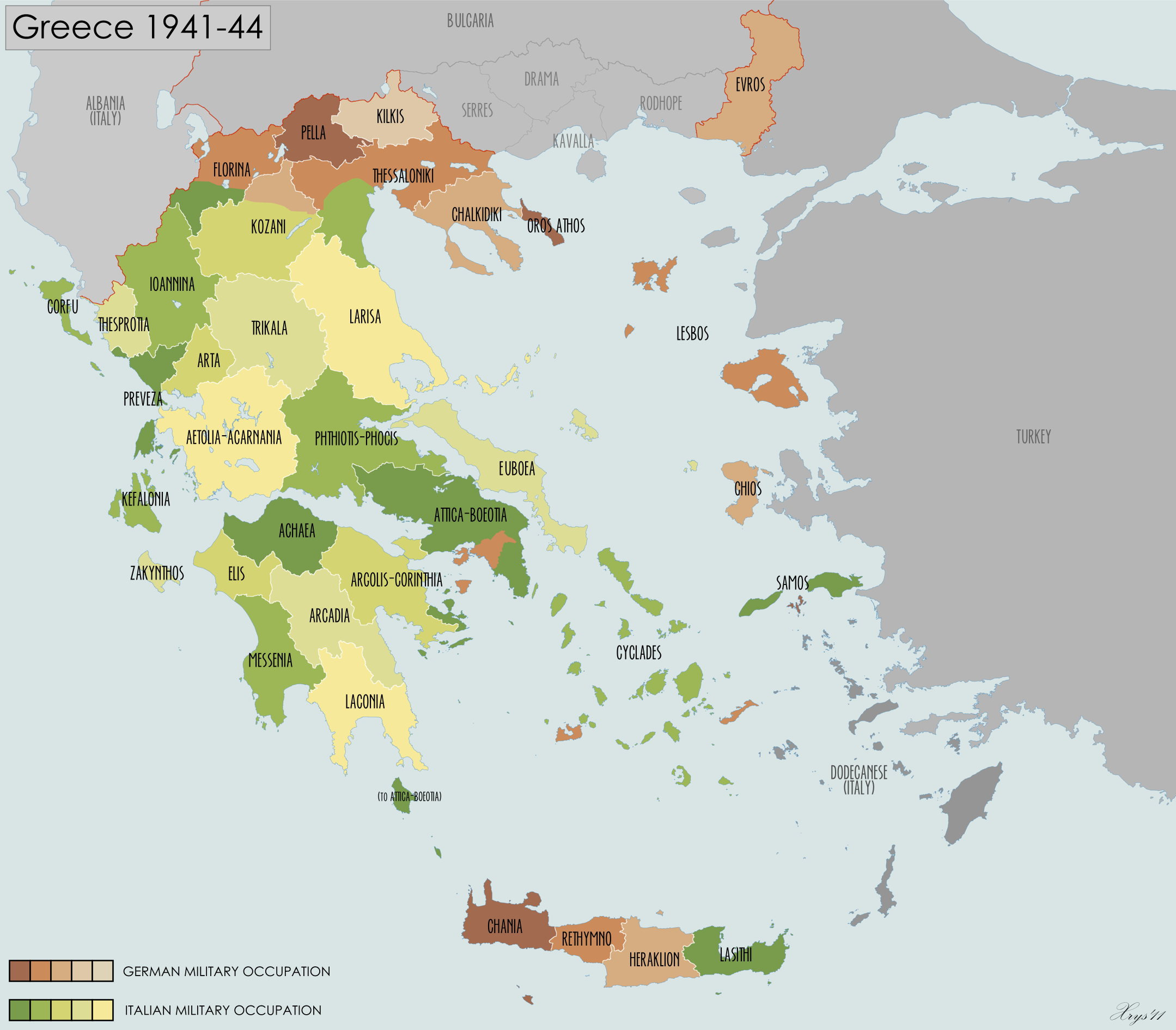

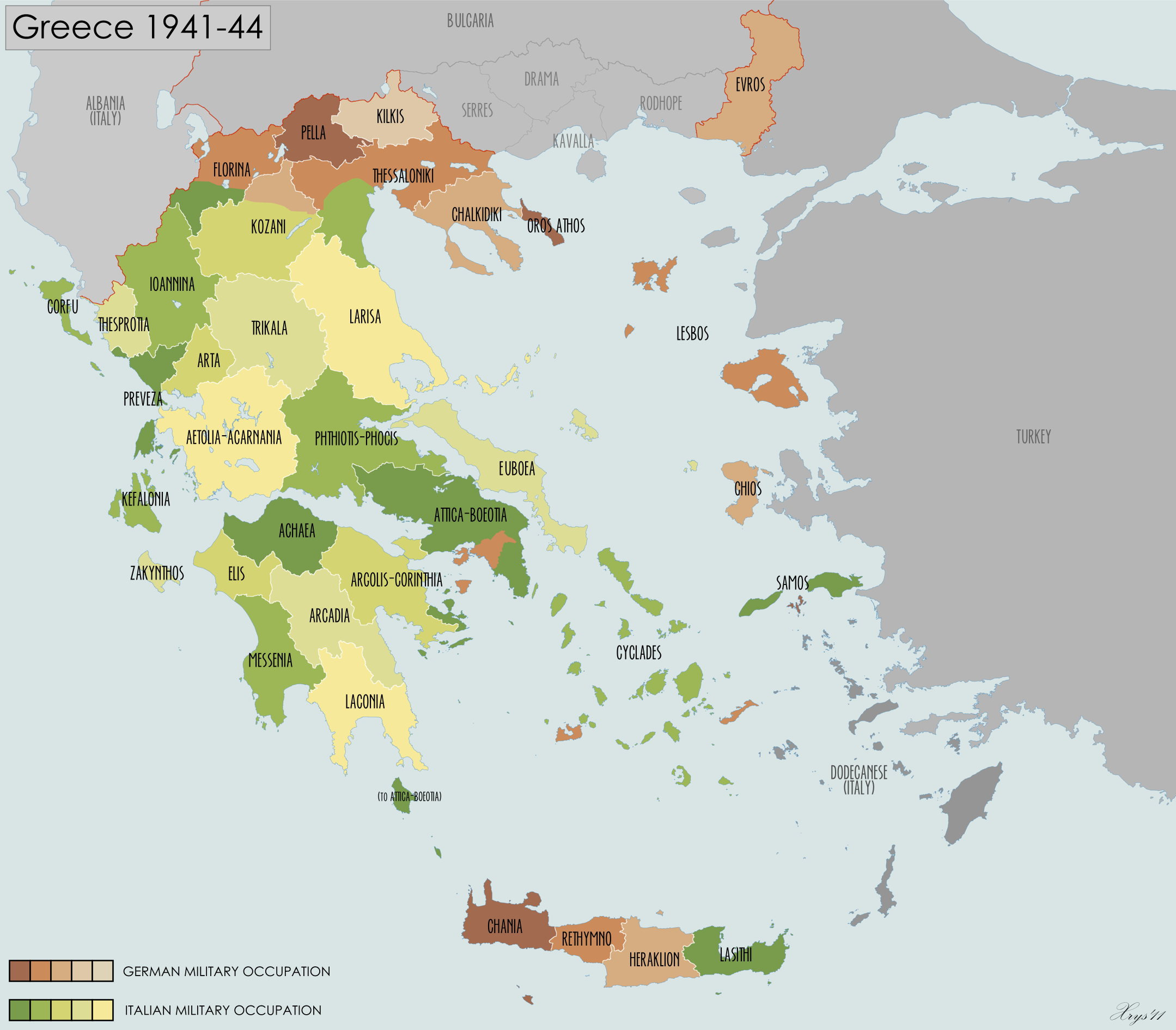

was established in its place. Greece's territory was divided into occupation zones run by the

Axis Powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

, with the Nazi Germans administering the most important regions of the country themselves, including

Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

,

Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

and strategic

Aegean Islands. Other regions of the country were run by Nazi Germany's partners, Italy and Bulgaria.

The occupation destroyed the Greek economy and brought immense hardships to the Greek civilian population. Most of Greece's economic capacity was destroyed, including 80% of industry, 28% of infrastructure (ports, roads and railways), 90% of its bridges, and 25% of its forests and other natural resources. Along with the loss of economic capacity, an estimated 7–11% of Greece's civilian population died as a result of the occupation. In Athens, 40,000 civilians died from

starvation

Starvation is a severe deficiency in caloric energy intake, below the level needed to maintain an organism's life. It is the most extreme form of malnutrition. In humans, prolonged starvation can cause permanent organ damage and eventually, de ...

a total of 300,000 in the whole of the country and tens of thousands more died from reprisals by Nazis and their collaborators.

[Mazower (2001), p. 155]

The Jewish population of Greece was nearly eradicated. Of its pre-war population of 75–77,000, around 11–12,000 survived, often by joining the resistance or being hidden. Most of those who died were deported to

Auschwitz

Auschwitz, or Oświęcim, was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It consisted of Auschw ...

, while those under Bulgarian occupation in Thrace were sent to

Treblinka

Treblinka () was the second-deadliest extermination camp to be built and operated by Nazi Germany in Occupation of Poland (1939–1945), occupied Poland during World War II. It was in a forest north-east of Warsaw, south of the Treblinka, ...

. The Italians did not deport Jews living in territory they controlled, but when the Germans took it over from them, Jews living there were also deported.

Greek Resistance groups were formed during this occupation. The most important of them was

ELAS

The Greek People's Liberation Army (, ''Ellinikós Laïkós Apeleftherotikós Stratós''; ELAS) was the military arm of the left-wing National Liberation Front (EAM) during the period of the Greek resistance until February 1945, when, followi ...

(''Ellinikós Laïkós Apeleftherotikós Stratós''Greek People's Liberation Army), which was the military arm of the

EAM (''Ethnikó Apeleftherotikó Métopo''National Liberation Front). Both groups were strongly associated with the

KKE (''Kommounistikó Kómma Elládas''Communist Party of Greece). They were commonly named ''antartes'' from the Greek

wikt:αντάρτης. Mark Mazower wrote that, the standing orders of the Wehrmacht in Greece was to use terror as a way to frighten the Greeks into not supporting the ''andartes'' (guerrillas).

This resistance group launched

guerrilla attacks against the occupying powers, fought against collaborationist

Security Battalions

The Security Battalions (, derisively known as ''Germanotsoliades'' (Γερμανοτσολιάδες, meaning "German tsoliás") or ''Tagmatasfalites'' (Ταγματασφαλίτες)) were Greek collaborationist paramilitary groups, formed d ...

, and set up espionage networks.

Throughout the war against the Soviet Union, German propaganda portrayed the war as a noble struggle to protect "European civilization" from "Bolshevism". Likewise, German officials portrayed the ''Reich'' as nobly occupying Greece to protect it from Communists and presented EAM as a demonic force. The ''andartes''of ELAS were portrayed in both the Wehrmacht and the SS as a "savages" and "criminals" who committed all sorts of crimes and who needed to be hunted down without mercy.

The British engaged in numerous intelligence deceptions designed to fool the Germans into thinking that the Allies would be landing in Greece in the near-future, and as such the German army forces were reinforced in Greece so as to stop the expected Allied landing in the Balkans. From the viewpoint of General

Alexander Löhr

Alexander Löhr (20 May 1885 – 26 February 1947) was an Austrian Air Force (1927–1938), Austrian Air Force commander during the 1930s and, after the Anschluss, annexation of Austria, he was a Luftwaffe commander. Löhr served in the Luftwaff ...

, the commander of one Nazi Army Group in Greece, Army Group E, the attacks of the ''andartes'', which forced his men to spread themselves out to hunt them down, were weakening his forces by leaving them exposed and spread out in the face of an expected Allied landing. However, the mountainous terrain of Greece ensured that there were only a limited number of roads and railroads bringing down supplies from Germany and the destruction of a single bridge by the ''andartes'' caused major supply problems for the German forces. The best known ''andarte'' operation of the war, namely the

blowing up of the Gorgopotamos viaduct on the night of 25 November 1942, had caused Nazi Germans serious logistical problems as it severed the main railroad linking Thessaloniki to Athens. This interfered with overall operations of Nazi Germany, since Athens and its port

Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; ; , Ancient: , Katharevousa: ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens city centre along the east coast of the Saronic Gulf in the Ath ...

was used as a point of transporting supplies.

By early 1944, due to foreign interference by both Britain and U.S.,

the resistance groups began to fight amongst themselves. At the end of occupation of the Greek mainland in October 1944, Greece was in a state of political polarization, which soon led to the

outbreak of civil war. The civil war gave opportunity to those who had prominently collaborated with Nazi Germany or other occupiers to reach positions of power and avoid sanctions because of

anti-communism

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism, communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global ...

, even eventually coming to power in post-war Greece after the Communist defeat.

The

Greek Resistance killed 21,087 Axis soldiers (17,536 Germans, 2,739 Italians, 1,532 Bulgarians) and captured 6,463 (2,102 Germans, 2,109 Italians, 2,252 Bulgarians), compared to the death of 20,650 Greek partisans and an unknown number captured.

BBC News

BBC News is an operational business division of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) responsible for the gathering and broadcasting of news and current affairs in the UK and around the world. The department is the world's largest broad ...

estimated Greece suffered at least 250,000 dead during the Axis occupation.

Fall of Greece

In the early morning hours of 28 October 1940, Italian ambassador

Emanuele Grazzi woke Greek premier

Ioannis Metaxas

Ioannis Metaxas (; 12 April 187129 January 1941) was a Greek military officer and politician who was dictator of Greece from 1936 until his death in 1941. He governed constitutionally for the first four months of his tenure, and thereafter as th ...

and presented him an

ultimatum

An ; ; : ultimata or ultimatums) is a demand whose fulfillment is requested in a specified period of time and which is backed up by a coercion, threat to be followed through in case of noncompliance (open loop). An ultimatum is generally the ...

. Metaxas rejected the ultimatum and Italian forces

invaded Greek territory from Italian-occupied

Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

less than three hours later. (The anniversary of Greece's refusal is now a

public holiday

A public holiday, national holiday, federal holiday, statutory holiday, bank holiday or legal holiday is a holiday generally established by law and is usually a non-working day during the year.

Types

Civic holiday

A ''civic holiday'', also k ...

in Greece.) Italian Prime Minister

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

launched the invasion partly to prove that Italians could match the military successes of the German Army and partly because Mussolini regarded southeastern Europe as lying within Italy's sphere of influence.

Against Mussolini's expectations, the

Hellenic Army

The Hellenic Army (, sometimes abbreviated as ΕΣ), formed in 1828, is the army, land force of Greece. The term Names of the Greeks, '' Hellenic'' is the endogenous synonym for ''Greek''. The Hellenic Army is the largest of the three branches ...

successfully exploited the mountainous terrain of

Epirus

Epirus () is a Region#Geographical regions, geographical and historical region, historical region in southeastern Europe, now shared between Greece and Albania. It lies between the Pindus Mountains and the Ionian Sea, stretching from the Bay ...

. Greek forces counterattacked and forced the Italians to retreat. By mid-December, the Greeks had occupied nearly one-quarter of Albania, before Italian reinforcements and the harsh winter stemmed the Greek advance. In March 1941, a

major Italian counterattack failed. 15 of the 21 Greek divisions were deployed against the Italians, leaving only six divisions to defend against the attack from German troops in the

Metaxas Line

The Metaxas Line (, ''Grammi Metaxa'') was a chain of fortifications constructed along the line of the Greco-Bulgarian border, designed to protect Greece in case of a Bulgarian invasion after the rearmament of Bulgaria. It was named after Ioa ...

near the border between Greece and Yugoslavia/Bulgaria in the first days of April. They were supported by

British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an international association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire

The B ...

troops sent from

Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

on the orders of

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

.

On 6 April 1941, Germany came to the aid of Italy and

invaded Greece through

Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

and

Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

, overwhelming Greek and British troops. On 20 April, after cessation of Greek resistance in the north, the

Bulgarian Army

The Bulgarian Army (), also called Bulgarian Armed Forces, is the military of Bulgaria. The commander-in-chief is the president of Bulgaria. The Ministry of Defense is responsible for political leadership, while overall military command is in ...

entered Greek

Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

without firing a shot, with the goal of regaining its

Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

outlet in Western Thrace and Eastern Macedonia. The Bulgarians occupied territory between the

Strymon River

The Struma or Strymonas (, ; , ) is a river in Bulgaria and Greece. Its Ancient Greek, ancient name was Strymon (, ). Its drainage area is , of which in Bulgaria, in Greece and the remaining in North Macedonia and Serbia. It takes its source fr ...

and a line of demarcation running through

Alexandroupoli

Alexandroupolis (, ) or Alexandroupoli (, ) is a city in Greece and the capital of the Evros (regional unit), Evros regional unit. It is the largest city in Greek Thrace and the region of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace, with a population of 71,75 ...

and

Svilengrad

Svilengrad (; ; ) is a town in Haskovo Province, south-central Bulgaria, situated at the tripoint of Bulgaria, Turkey, and Greece. It is the administrative centre of the homonymous Svilengrad Municipality.

Geography

Svilengrad is close to the ro ...

west of the

Evros River

Maritsa or Maritza ( ), also known as Evros ( ) and Meriç ( ), is a river that runs through the Balkans in Southeast Europe. With a length of , . The Greek capital

Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

fell on 27 April, and by 1 June, after the

capture of Crete, all of Greece was under Axis occupation. After the invasion, King

George II fled, first to Crete and then to Cairo. A Greek right-wing government ruled from Athens as a

puppet

A puppet is an object, often resembling a human, animal or Legendary creature, mythical figure, that is animated or manipulated by a person called a puppeteer. Puppetry is an ancient form of theatre which dates back to the 5th century BC in anci ...

of the occupying forces.

Triple occupation

Establishment of the occupation regime

Although the German army was instrumental in the conquest of Greece, this was an accident born of Italy's ill-fated invasion and the subsequent presence of British troops on Greek soil. Greece had not figured in

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

's pre-war plans as a target for German annexation: the country was poor, not adjacent to Germany, and did not host any German minorities. The Greeks themselves were seen by Nazi racial theory as neither valuable enough to be Germanized and assimilated, nor as sub-humans to be exterminated. Indeed, Hitler opposed the diversion of efforts towards western and southern Europe, and focused on the conquest and assimilation of Eastern Europe as the future German "

Lebensraum

(, ) is a German concept of expansionism and Völkisch movement, ''Völkisch'' nationalism, the philosophy and policies of which were common to German politics from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901, '' lso in:' beca ...

". Coupled with admiration for the Greek resistance to the Italian invasion, the result was that Hitler favoured postponing a final territorial settlement of Italy's claims on Greece to after the war. In the meantime, a local puppet government headed by Lt. General

Georgios Tsolakoglou

Georgios Tsolakoglou (; April 1886 – 22 May 1948) was a Greek army officer who headed the government of Greece from 1941 to 1942, in the early phase of the country's occupation by Axis powers during World War II.

An officer of the Hellenic Ar ...

would be installed as the most efficient way to run the country.

Eager to pull German troops out of the country in view of the imminent

invasion of the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along a ...

, and to shore up his relations with his most important Axis partner, Hitler agreed to leave most of the country to be occupied by the Italians. This was undertaken by the

Eleventh Army under

Carlo Geloso

Carlo Geloso (20 August 1879 – 23 July 1957) was an Italian general during the Second World War. In 1939, he assumed command of the Italian forces in Albania. In 1940, he served as commander of the 11th Army during the Greco-Italian War. He w ...

, with three army corps:

XXVI Army Corps in

Epirus

Epirus () is a Region#Geographical regions, geographical and historical region, historical region in southeastern Europe, now shared between Greece and Albania. It lies between the Pindus Mountains and the Ionian Sea, stretching from the Bay ...

and western Greece,

III Army Corps in

Thessaly

Thessaly ( ; ; ancient Aeolic Greek#Thessalian, Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic regions of Greece, geographic and modern administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient Thessaly, a ...

, and

VIII Army Corps in the

Peloponnese

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridg ...

. The northeastern parts of the country, eastern

Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

and most of

Western Thrace

Western Thrace or West Thrace (, '' ytikíThráki'' ), also known as Greek Thrace or Aegean Thrace, is a geographical and historical region of Greece, between the Nestos and Evros rivers in the northeast of the country; East Thrace, which lie ...

, were handed over to Bulgaria, and were de facto annexed into the Bulgarian state. However, a band of territory along the

Evros River

Maritsa or Maritza ( ), also known as Evros ( ) and Meriç ( ), is a river that runs through the Balkans in Southeast Europe. With a length of , , on Greece's border with Turkey, remained under control of the collaborationist Greek government to give the Turkish government a pretext for disregarding her obligations to assist Greece in case of a Bulgarian attack according to the 1934

Balkan Pact

The Balkan Pact, or Balkan Entente, was a treaty signed by Greece, Romania, Turkey and Yugoslavia on 9 February 1934 . Entry to this zone was forbidden to the Bulgarians, and the Germans maintained only a police and administrative staff there. The Germans also retained control of a patchwork of strategically important areas across the country. The region of

Central Macedonia

Central Macedonia ( ; , ) is one of the thirteen Regions of Greece, administrative regions of Greece, consisting the central part of the Geographic regions of Greece, geographical and historical region of Macedonia (Greece), Macedonia. With a ...

around Greece's second largest city,

Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

, was kept under German control both as a strategic outlet into the Aegean as well as a trump card between the competing claims of both Bulgarians and Italians on it. Along with the eastern Aegean islands of

Lemnos

Lemnos ( ) or Limnos ( ) is a Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within the Lemnos (regional unit), Lemnos regional unit, which is part of the North Aegean modern regions of Greece ...

,

Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of , with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, eighth largest ...

,

Agios Efstratios

Agios Efstratios or Saint Eustratius (), colloquially Ai Stratis (), anciently Halonnesus or Halonnesos (), is a small Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea about southwest of Lemnos and northwest of Lesbos. The municipality has an area of 43. ...

, and

Chios

Chios (; , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greece, Greek list of islands of Greece, island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea, and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, tenth largest island in the Medi ...

, became 'Salonica-Aegean Military Command' () under

Curt von Krenzki

Kurt is a male given name in Germanic languages, Germanic languages. ''Kurt'' or ''Curt'' originated as short forms of the Germanic Conrad (name), Konrad/Conrad, depending on geographical usage, with meanings including counselor or advisor. Like ...

. Further south, the 'South Greece Military Command' () under

Hellmuth Felmy

Hellmuth Felmy (28 May 1885 – 14 December 1965) was a German general and war criminal during World War II, commanding forces in occupied Greece and Yugoslavia. A high-ranking Luftwaffe officer, Felmy was tried and convicted in the 1948 Hostage ...

comprised isolated locations of

Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

and the

Attica

Attica (, ''Attikḗ'' (Ancient Greek) or , or ), or the Attic Peninsula, is a historical region that encompasses the entire Athens metropolitan area, which consists of the city of Athens, the capital city, capital of Greece and the core cit ...

region, such as the

Kalamaki Airfield, parts of the port of

Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; ; , Ancient: , Katharevousa: ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens city centre along the east coast of the Saronic Gulf in the Ath ...

, and the offshore islands of

Salamis,

Aegina

Aegina (; ; ) is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina (mythology), Aegina, the mother of the mythological hero Aeacus, who was born on the island and became its king.

...

, and

Fleves; the island of

Milos

Milos or Melos (; , ; ) is a volcanic Greek island in the Aegean Sea, just north of the Sea of Crete. It is the southwestern-most island of the Cyclades group.

The ''Venus de Milo'' (now in the Louvre), the ''Poseidon of Melos'' (now in the ...

as a mid-way stronghold to Crete; and most of Crete, except for the eastern

Lasithi Prefecture

Lasithi () is the easternmost regional unit on the island of Crete, to the east of Heraklion. Its capital is Agios Nikolaos, the other major towns being Ierapetra and Sitia. The mountains include the Dikti in the west and the Thrypti in the east. ...

, which was handed over to the Italians. Crete, quickly named "

Fortress Crete

Fortress Crete () was the term used during World War II by the German occupation forces to refer to the garrison and fortification of Crete.

Background

The Greek island of Crete was seized by the Axis after a fierce battle at the end of May 1 ...

", came to be regarded as a de facto separate command; upon the insistence of the

Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official military branch, branche ...

, it was regarded as a target for eventual annexation after the war. The islands of

Euboea

Euboea ( ; , ), also known by its modern spelling Evia ( ; , ), is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete, and the sixth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by ...

and

Skyros

Skyros (, ), in some historical contexts Romanization of Greek, Latinized Scyros (, ), is an island in Greece. It is the southernmost island of the Sporades, an archipelago in the Aegean Sea. Around the 2nd millennium BC, the island was known as ...

, originally allotted to the German zone, were handed over to Italian control in October 1941; southern Attica was likewise transferred to the Italians in September 1942.

From the outset, the so-called , 'preponderance') granted to Italy by Hitler proved an illusion. The Italian plenipotentiary in Greece, Count

Pellegrino Ghigi, shared control over the Greek puppet government with his German counterpart, Ambassador

Günther Altenburg, while the fragmented occupation regimes meant that different military commanders were responsible for different parts of the country. As the historian

Mark Mazower

Mark Mazower (; born 20 February 1958) is a British historian. His areas of expertise are Greece, the Balkans, and more generally, 20th-century Europe. He is Ira D. Wallach Professor of History at Columbia University in New York City.

Early ...

comments, "The stage was set for bureaucratic infighting of Byzantine complexity: Italians pitted against Germans, diplomats against generals, the Greeks trying to play one master off against the other". Relations between the Germans and Italians were not good and there were brawls between German and Italian soldiers; the Germans regarded the Italians as incompetent and frivolous, while the Italians considered the behaviour of their ostensible allies as barbarous. By contrast, the Italians had no such inhibitions, which created problems among

Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

and

SS officers. German officers often complained that the Italians were more interested in making love than in making war, and that the Italians lacked the "hardness" to wage a campaign against the Greek guerrillas because many Italian soldiers had Greek girlfriends. After the

Italian capitulation in September 1943, the Italian zone was taken over by the Germans, often by attacking the Italian garrisons. There was a failed attempt by the British to take advantage of the Italian surrender to reenter the Aegean Sea with the

Dodecanese Campaign

The Dodecanese campaign was the capture and occupation of the Dodecanese islands by German forces during World War II. Following the signing of the Armistice of Cassibile on 3 September 1943, Italy switched sides and joined the Allies. As a ...

.

German occupation zone

From 1942 onwards, the German occupation zone was ruled by the

duumvirate

Diarchy (from Greek , ''di-'', "double", and , ''-arkhía'', "ruled"),Occasionally spelled ''dyarchy'', as in the ''Encyclopaedia Britannica'' article on the colonial British institution duarchy, or duumvirate. is a form of government charact ...

of the plenipotentiary for South-Eastern Europe,

Hermann Neubacher

Hermann Neubacher (24 June 1893 – 1 July 1960) was an Austrian Nazi politician who held a number of diplomatic posts in the Third Reich. During the Second World War, he was appointed as the leading German foreign ministry official for Greece and ...

, and Field Marshal

Alexander Löhr

Alexander Löhr (20 May 1885 – 26 February 1947) was an Austrian Air Force (1927–1938), Austrian Air Force commander during the 1930s and, after the Anschluss, annexation of Austria, he was a Luftwaffe commander. Löhr served in the Luftwaff ...

. In September–October 1943,

Jürgen Stroop

Jürgen Stroop (born Josef Stroop, 26 September 1895 – 6 March 1952) was a German SS commander and perpetrator of the Holocaust during the Nazi era, who served as SS and Police Leader in occupied Poland and Greece from 1942-1943 (in Poland) an ...

, the newly appointed Higher SS Police Leader, tried to challenge the Neubacher-Löhr duumvirate and was swiftly fired after less than a month on the job.

Walter Schimana

Walter Schimana (12 March 1898 – 12 September 1948) was an Austrian Nazi and a general in the SS during the Nazi era. He was SS and Police Leader in the occupied Soviet Union in 1942 and Higher SS and Police Leader in occupied Greece from ...

replaced Stroop as the Higher SS Police Leader in Greece and established a better working relationship with the Neubacher-Löhr duumvirate.

Economic exploitation and the Great Famine

Residents of Greece suffered greatly during the occupation. With the country's economy having been reduced from six months of war, and economic exploitation by the occupying forces, raw materials and food were requisitioned, and the collaborationist government paid the costs of the occupation, which resulted in greater inflation. Because the outflows of raw materials and products from Greece towards Germany weren't offset by German payments, substantial imbalances accrued in the settlement accounts at the

National Bank of Greece

The National Bank of Greece (NBG; ) is a banking and financial services company with its headquarters in Athens, Greece. Founded in 1841 as the newly independent country's first financial institution, it has long been the largest Greek bank, a ...

. In October 1942 the trading company

DEGRIGES was founded; two months later, the Greek collaborationaist government agreed to treat the balance as a loan without interest that was to be repaid once the war was over. By the end of the war, this forced loan amounted to 476 million Reichsmarks (equivalent to billion euros).

Hitler's policy toward the economy of occupied Greece was termed ''Vergeltungsmassnahme'', or, roughly, "retaliation measures", the "retaliation" being for Greece having chosen the wrong side. Germany was additionally motivated by a desire to "pluck out the best fruit" to plunder before the Italians could get it. Groups of economic advisers, businessmen, engineers and factory managers came from Germany with the task of seizing anything they deemed of economic value, with involvement from both Germany's Economic Ministry and its Foreign Office involved in the operation. These groups saw themselves as in competition with the Italians to plunder the country, and also with each other. The primary purpose of the German requisitions, however, was finding as much food as possible to sustain the German army. The occupying powers' requisitions, disruption in agricultural production, hoarding by farmers and breakdown of the country's distribution networks from both infrastructure damage and change in government structure led to a severe shortage of food in the major urban centres in the winter of 1941–42. Some of this shortage is attributable to the

Allied blockade of Europe since Greece depended on wheat imports to cover about a third of its annual needs. These factors created the conditions for the "Great Famine" (Μεγάλος Λιμός) where in the greater

Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

–

Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; ; , Ancient: , Katharevousa: ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens city centre along the east coast of the Saronic Gulf in the Ath ...

area alone, some 40,000 people died of starvation, and by the end of the occupation "it was estimated that the total population of Greece

..was 300,000 less than it should have been because of famine or malnutrition".

Greece received some foreign aid to make up some of the shortfall, coming at first from neutral countries like

Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

and

Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

(see

SS ''Kurtuluş''), but most of the food ended up in the hands of government officials and black market traders, who used their connection to the authorities to "buy" the aid from them and then sell it on at inflated prices. The perception of suffering and pressure from the Kingdom of Greece's government in exile eventually led to the British partially lifting the blockade, and from the summer of 1942 Canadian wheat began to be distributed by the

International Red Cross

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is a aid agency, humanitarian organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, and is a three-time Nobel Prize laureate. The organization has played an instrumental role in the development of Law of ...

. Of the country's 7.3 million inhabitants in 1941, it is estimated that 2.5 million received this aid, of whom half lived in Athens, meaning that almost all people in the capital city received this aid. Although the food aid reduced the risk of starvation in the cities, little of it reached the countryside, which experienced its own period of famine in 1943–44. The rise of the armed Resistance resulted in major anti-partisan campaigns across the countryside by the Axis, which led to wholesale burning of villages, destruction of fields, and mass executions in retaliation for guerrilla attacks. As P. Voglis writes, the German sweeps "

urnedproducing areas into burned fields and pillaged villages, and the wealthy provincial towns into refugee settlements".

Italian occupation zone

Annexationist and separatist projects

After the German invasion, the Italian government put forward vague demands for annexations in northwestern Greece, as well as the

Ionian Islands

The Ionian Islands (Modern Greek: , ; Ancient Greek, Katharevousa: , ) are a archipelago, group of islands in the Ionian Sea, west of mainland Greece. They are traditionally called the Heptanese ("Seven Islands"; , ''Heptanēsa'' or , ''Heptanē ...

, but these were turned down by the Germans, as they would have been a hindrance to concluding an armistice and establishing a collaborationist government: any such concession would have terminated the puppet government's legitimacy. Likewise, Italian suggestions for an outright military occupation without a Greek administration were rejected. Hitler and the German Foreign Minister,

Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich-Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German Nazi politician and diplomat who served as Minister for Foreign Affairs (Germany), Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945. ...

, even cautioned the Italians of the dangers of annexing territories inhabited by large Greek populations, which might become hotbeds of resistance. Nevertheless, in the Ionian Islands the Greek civil authorities were replaced by Italians, presumptively in preparation for annexation after the war. Claiming the inheritance of the

Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice, officially the Most Serene Republic of Venice and traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and Maritime republics, maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 ...

, which had

ruled the islands for centuries, the senior Fascist Party official

Pietro Parini

Pietro is an Italian masculine given name. Notable people with the name include:

People

* Pietro I Candiano (c. 842–887), briefly the 16th Doge of Venice

* Pietro Tribuno (died 912), 17th Doge of Venice, from 887 to his death

* Pietro II Can ...

took steps to uncouple the islands from the rest of Greece: his decrees had the force of law, a new currency, the "

Ionian Drachma", was introduced in early 1942, and a policy of Italianization initiated in public education and the press. Similar steps were undertaken in the eastern Aegean island of

Samos

Samos (, also ; , ) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese archipelago, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the Mycale Strait. It is also a separate reg ...

. However, due to German insistence, no official annexation took place during the occupation.

Italian policy promised that the region of

Chameria

Chameria (; , ''Tsamouriá'') is a term used today mostly by Albanians to refer to parts of the coastal region of Epirus in southern Albania and Greece, traditionally associated with the Albanian ethnic subgroup of the Chams.Elsie, Robert and Be ...

(

Thesprotia

Thesprotia (; , ) is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the Epirus region. Its capital and largest town is Igoumenitsa. Thesprotia is named after the Thesprotians, an ancient Greek tribe that inhabited the region in antiquity.

His ...

) in northwestern Greece would be

awarded to Albania after the end of the war. Similarly to the Ionian Islands, a local administration (

Këshilla

Këshilla (literally meaning "Council" in Albanian; ) was an Albanian administration in Thesprotia, Greece, during the Axis occupation of Greece (1941-1944). It was set up during the Fascist Italian occupation with the aim of annexing the Greek reg ...

) was installed, and armed groups were formed by the local

Cham Albanian

Cham Albanians or Chams (; , ), are a sub-group of Albanians who originally resided in the western part of the region of Epirus in southwestern Albania and northwestern Greece, an area known among Albanians as Chameria. The Chams have their ow ...

community. For at least the beginning of the occupation, Muslim communities chose different political alignments according to the circumstances, alternating between collaboration, neutrality and, less frequently, resistance. Albanian and Greek communities allied with the strongest available patron and shifted their allegiances when a better one appeared. Many events were part of a cycle of revenge between local communities over land ownership, state policies, sectarian hostilities and personal vendettas. This cycle of revenge became nationalized during the war with different communities choosing different sides. Although the majority of Cham Albanian elites

collaborated with the Axis, some Chams joined a mixed EAM battalion at the end of the war, but never ended up making a significant contribution to the resistance against Germany.

(For local developments in 1944–1945: see

Expulsion of Cham Albanians

The expulsion of Cham Albanians from Greece was the forced migration and ethnic cleansing of thousands of Cham Albanians from settlements of Chameria in Thesprotia, Greece - after the Second World War to People's Socialist Republic of Albania ...

). After the war, a Special Court on Collaborators in

Ioannina

Ioannina ( ' ), often called Yannena ( ' ) within Greece, is the capital and largest city of the Ioannina (regional unit), Ioannina regional unit and of Epirus (region), Epirus, an Modern regions of Greece, administrative region in northwester ...

condemned 2,109

Cham

Cham or CHAM may refer to:

Ethnicities and languages

*Chams, people in Vietnam and Cambodia

**Cham language, the language of the Cham people

***Cham script

*** Cham (Unicode block), a block of Unicode characters of the Cham script

* Cham Albani ...

collaborators to death

in absentia

''In Absentia'' is the seventh studio album by British progressive rock band Porcupine Tree, first released on 24 September 2002. The album marked several changes for the band, with it being the first with new drummer Gavin Harrison and the f ...

.

[Examining policy responses to immigration in the light of interstate relations and foreign policy objectives: Greece and Albania]

. In King, Russell, & Stephanie Schwandner-Sievers (eds). ''The new Albanian migration''. Sussex Academic. p. 16. However, by the time of conviction, they had already relocated abroad.

Some of the

Vlach

Vlach ( ), also Wallachian and many other variants, is a term and exonym used from the Middle Ages until the Modern Era to designate speakers of Eastern Romance languages living in Southeast Europe—south of the Danube (the Balkan peninsula) ...

(

Aromanian) population in the

Pindus

The Pindus (also Pindos or Pindhos; ; ; ) is a mountain range located in Northern Greece and Southern Albania. It is roughly long, with a maximum elevation of (Smolikas, Mount Smolikas). Because it runs along the border of Thessaly and Epiru ...

mountains and Western Macedonia also collaborated with the Axis powers. Italian occupation forces were welcomed in some Aromanian villages as liberators, and Aromanians offered their services as guides or interpreters in exchange for favors. Under

Alcibiades Diamandi

Alcibiades Diamandi (13 August 1893 – 9 July 1948, sometimes spelled ''Diamanti'' or ''Diamantis''; ; ) was an Aromanian political figure of Greece and Axis collaborator, active during the First and Second world wars in connection with the I ...

, the pro-Italian

Principality of the Pindus was declared, and 2000 locals joined his ''Roman Legion'', while another band of Aromanian followers under

Nicolaos Matussis

Nicolaos Matussis, also spelled as Nicolae Matussi (; 1899–1991), was an Aromanian lawyer, politician and leader of the Roman Legion, a collaborationist, separatist Aromanian paramilitary unit active during World War II in central Greece.

Ea ...

carried out raids in service of Italy. While most local Aromanians remained loyal to the Greek nation, some collaborated with the Axis powers because of latent pro-Romanian feelings or anger toward the Greek government and its military. Diamandi's Legion collapsed in 1942 when Italian positions were taken over by Germany, and most of its leaders fled to Romania or Greek cities. Most active members were convicted as war criminals in absentia, but many convictions were forgotten over the course of the

Greek Civil War

The Greek Civil War () took place from 1946 to 1949. The conflict, which erupted shortly after the end of World War II, consisted of a Communism, Communist-led uprising against the established government of the Kingdom of Greece. The rebels decl ...

, in which many convicted Legion members actively fought for the government.

Oppression and reprisals

Compared to the other two occupation zones, the Italian regime was relatively safe for its Greek residents, with a relatively low number of executions and atrocities compared to the German and Bulgarian zones.

Unlike the Germans, the Italian military mostly protected Jews in their zone, and rejected the introduction of measures such as those established in the German occupation zone in Thessaloniki. The Germans were purportedly perturbed as the Italians not only protected Jews on their territory, but in parts of occupied France, Greece, the Balkans, and elsewhere. On 13 December 1942,

Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician and philologist who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief Propaganda in Nazi Germany, propagandist for the Nazi Party, and ...

, Hitler's propaganda minister, wrote in his diary, "The Italians are extremely lax in the treatment of the Jews. They protect the Italian Jews both in

Tunis

Tunis (, ') is the capital city, capital and largest city of Tunisia. The greater metropolitan area of Tunis, often referred to as "Grand Tunis", has about 2,700,000 inhabitants. , it is the third-largest city in the Maghreb region (after Casabl ...

and in occupied France and will not permit their being drafted for work or compelled to wear the Star of David. This shows once again that Fascism does not really dare to get down to fundamentals but is very superficial regarding problems of vital importance."

Mass reprisals did sometimes occur, such as the

Domenikon massacre in which 150 Greek civilians were killed. As they controlled most of the countryside, Italy was the first to face the rising resistance movement in 1942–43. By mid-1943, the resistance had managed to expel a few Italian garrisons from some mountainous areas, including several towns, creating liberated zones ("Free Greece"). After the

Italian armistice

The Armistice of Cassibile ( Italian: ''Armistizio di Cassibile'') was an armistice that was signed on 3 September 1943 by Italy and the Allies, marking the end of hostilities between Italy and the Allies during World War II. It was made public ...

in September 1943, the Italian zone was taken over by the Germans. As a result, German anti-partisan and anti-Semitic policies were extended to it.

Bulgarian occupation zone

The

Bulgarian Army

The Bulgarian Army (), also called Bulgarian Armed Forces, is the military of Bulgaria. The commander-in-chief is the president of Bulgaria. The Ministry of Defense is responsible for political leadership, while overall military command is in ...

entered Greece on 20 April 1941 on the heels of the

Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

without having fired a shot. The Bulgarian occupation zone included the northeastern corner of the Greek mainland and the islands of

Thasos

Thasos or Thassos (, ''Thásos'') is a Greek island in the North Aegean Sea. It is the northernmost major Greek island, and 12th largest by area.

The island has an area of 380 km2 and a population of about 13,000. It forms a separate regiona ...

and

Samothrace

Samothrace (also known as Samothraki; , ) is a Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea. It is a municipality within the Evros regional unit of Thrace. The island is long, in size and has a population of 2,596 (2021 census). Its main industries ...

, which corresponds to the present-day region of

East Macedonia and Thrace

Eastern Macedonia and Thrace ( ; , ) is one of the thirteen administrative regions of Greece. It consists of the northeastern parts of the country, comprising the eastern part of the region of Macedonia along with the region of Western Thr ...

, except for the

Evros prefecture

Evros () is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of East Macedonia and Thrace. Its name is derived from the river Evros, which appears to have been a Thracian hydronym. Evros is the northernmost regional unit. It borders T ...

at the Greek-Turkish border, which was retained by the Germans over Bulgarian protests because of its strategic value. Unlike Germany and Italy, Bulgaria officially annexed the occupied territories on 14 May 1941, which had long been a target of Bulgarian foreign policy.

[Mazower (2000), p. 276] East Macedonia and Thrace had been part of the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

until 1913, when it became part of Bulgaria following the

First Balkan War

The First Balkan War lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and involved actions of the Balkan League (the Kingdoms of Kingdom of Bulgaria, Bulgaria, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Greece, Greece and Kingdom of Montenegro, Montenegro) agai ...

until being annexed by Greece in two stages. Later in 1913, Greece annexed parts of Western Thrace after the

Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict that broke out when Kingdom of Bulgaria, Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia and Kingdom of Greece, Greece, on 1 ...

, and then in 1920 at the

San Remo conference

The San Remo conference was an international meeting of the post-World War I Allied Supreme Council as an outgrowth of the Paris Peace Conference, held at Castle Devachan in Sanremo, Italy, from 19 to 26 April 1920. The San Remo Resolution ...

, Greece formally received the remainder of present-day

Western Thrace

Western Thrace or West Thrace (, '' ytikíThráki'' ), also known as Greek Thrace or Aegean Thrace, is a geographical and historical region of Greece, between the Nestos and Evros rivers in the northeast of the country; East Thrace, which lie ...

province after its victory in

WWI

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting took place mainly in Europe and th ...

.

Throughout the Bulgarian occupation zone, Bulgaria had a policy of extermination, expulsion and

ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

,

aiming to forcibly

Bulgarize, expel or kill ethnic Greeks.

[Miller (1975), p. 127] This

Bulgarization

Bulgarisation (), also known as Bulgarianisation () is the spread of Bulgarian culture beyond the Bulgarian ethnic space. Historically, unsuccessful assimilation efforts in Bulgaria were primarily directed at Muslims, most notably Bulgarian Turks ...

campaign deported all Greek mayors, landowners, industrialists, school teachers, judges, lawyers, priests and

Hellenic Gendarmerie

The Hellenic Gendarmerie (, ''Elliniki Chorofylaki'') was the national gendarmerie and military police (until 1951) force of Greece.

History

19th century

The Greek Gendarmerie was established after the enthronement of Otto of Greece, King Ot ...

officers.

The usage of the Greek language was banned, and the names of towns and places were changed to traditional Bulgarian forms.

Gravestones bearing Greek inscriptions were defaced as a part of the effort.

The Bulgarian government tried to alter the ethnic composition of the region by aggressively expropriating land and houses from Greek people in favor of settlers from Bulgaria, and enacted

forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, or violence, including death or other forms of ...

and economic restrictions on Greek businesses, in an effort to influence them to migrate to the German- and Italian-occupied parts of Greece.

A licensing system banned the practice of trades and professions without permission, along with confiscation of estates of Greek landowners, which were given to Bulgarian peasants settlers from within the pre-war boundaries of Bulgaria.

As a reaction to these policies, there was a spontaneous and poorly organized attempt to expel the Bulgarians with an uprising

around Drama in late September 1941 primarily guided by the

Communist Party of Greece

The Communist Party of Greece (, ΚΚΕ; ''Kommounistikó Kómma Elládas'', KKE) is a Marxist–Leninist political party in Greece. It was founded in 1918 as the Socialist Workers' Party of Greece (SEKE) and adopted its current name in Novem ...

. This uprising was suppressed by the Bulgarian Army, followed by massive reprisals against Greek civilians.

By late 1942, more than 100,000 Greeks were expelled from the Bulgarian occupation zone.

Bulgarian colonists were encouraged to settle in East Macedonia and Thrace with credits and incentives from the central Bulgarian government, including confiscated land and houses.

The Bulgarian government's attempts to win the loyalty of the local Slavic language-speaking populations and recruit collaborators among them had some success, with the Bulgarian armed forces being greeted as liberators in some areas. However, the ethnic composition of the region meant that the most of its inhabitants actively resisted the occupying forces. East Macedonia and Thrace had an ethnically mixed population until the early 20th century, including Greeks, Turks, Slavic-speaking Christians (some of whom self-identified as Greeks, others as Bulgarians), Jews, and

Pomaks

Pomaks (; Macedonian: Помаци ; ) are Bulgarian-speaking Muslims inhabiting Bulgaria, northwestern Turkey, and northeastern Greece. The strong ethno-confessional minority in Bulgaria is recognized officially as Bulgarian Muslims by th ...

(a Muslim Slavic group). However, during the

interwar years

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

, the ethnic composition of the region's population had dramatically shifted, as Greek refugees from

Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

settled in Macedonia and Thrace following the

population exchange between Greece and Turkey

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey stemmed from the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations" signed at Lausanne, Switzerland, on 30 January 1923, by the governments of Greece and Turkey. It involv ...

. This left only a minority of local Slavic language speakers as the target of the Bulgarian government's recruitment and collaboration efforts.

Because of these occupation policies, there was armed resistance in the Bulgarian zone was that enjoyed widespread support from the civilians in the region;

[Μάρκος Βαφειάδης, Απομνημονεύματα, Β΄ Τόμος, σελίδες 64–65, 1984, Εκδόσεις Λιβάνη] Greek guerrillas engaged the Bulgarian military in many battles, even entering pre-war Bulgarian territory, raided villages and captured booty.

In 1943, previously united Greek factions began armed conflict between communist and right-wing groups with the aim of securing control of the region following the anticipated Bulgarian withdrawal.

There were a few instances of collaboration by the

Muslim minority in Western Thrace, who mainly resided in the

Komotini

Komotini (, , ), is a city in the Modern regions of Greece, region of East Macedonia and Thrace, northeastern Greece and its capital. It is also the capital of the Rhodope (regional unit), Rhodope. It was the administrative centre of the Rhodope- ...

and

Xanthi

Xanthi is a city in the region of Western Thrace, northeastern Greece. It is the capital of the Xanthi regional unit of the region of East Macedonia and Thrace.

Amphitheatrically built on the foot of Rhodope mountain chain, the city is divided ...

prefectures.

Bulgarian activities in German-occupied Macedonia

The Bulgarian government also attempted to extend its influence to central and west Macedonia. The German High Command approved the foundation of a Bulgarian military club in

Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

, and Bulgarian officers organized supplying of food and provisions for the Slavic-speaking population in these regions, aiming to recruit collaborators and gather intelligence on what was happening in the German- and Italian-occupied zones. In 1942, the Bulgarian club asked assistance from the High Command in organizing armed units among those populations, but the Germans were initially very suspicious. Taking advantages of Italian incompetence and the German need for releasing troops on other fronts, since 1943 Sofia had been seeking to extend its control over the rest of Macedonia. After the Italian collapse in 1943, the Germans allowed the Bulgarians to intervene in Greek Central Macedonia, over the area between the Strymon and Axios rivers. The situation also forced the Germans to take control of Western Macedonia with the occasional interventions of Bulgarian troops. At that time the Greek guerrilla forces, especially the left-wing

Greek People's Liberation Army

The Greek People's Liberation Army (, ''Ellinikós Laïkós Apeleftherotikós Stratós''; ELAS) was the military arm of the left-wing National Liberation Front (EAM) during the period of the Greek resistance until February 1945, when, followi ...

(ELAS) were gaining more and more strength in the area. As a result, armed collaborationist militias composed of

pro-Bulgarian

Bulgarians (, ) are a nation and South Slavic ethnic group native to Bulgaria and its neighbouring region, who share a common Bulgarian ancestry, culture, history and language. They form the majority of the population in Bulgaria, while in No ...

Slavic-speakers, known as

Ohrana

Ohrana (, "Protection"; ) were armed collaborationist detachments organized by the former Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) structures, composed of Bulgarians in Nazi-occupied Greek Macedonia during World War II and led by ...

, were formed in 1943 in the districts of

Pella

Pella () is an ancient city located in Central Macedonia, Greece. It served as the capital of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. Currently, it is located 1 km outside the modern town of Pella ...

,

Florina

Florina (, ''Flórina''; known also by some alternative names) is a town and municipality in the mountainous northwestern Macedonia, Greece. Its motto is, 'Where Greece begins'.

The town of Florina is the capital of the Florina regional uni ...

and

Kastoria

Kastoria (, ''Kastoriá'' ) is a city in northern Greece in the modern regions of Greece, region of Western Macedonia. It is the capital of Kastoria (regional unit), Kastoria regional unit, in the Geographic regions of Greece, geographic region ...

. The ELAS units joined EAM in 1944 before the end of the occupation.

Bulgarian withdrawal

The Soviet Union declared war on the Kingdom of Bulgaria in early September 1944. Bulgaria withdrew from the central parts of Greek Macedonia after the pro-Soviet coup in the country

on 9 September 1944. At that time it declared war on Germany, but the Bulgarian army remained in

Eastern Macedonia and Thrace

Eastern Macedonia and Thrace ( ; , ) is one of the thirteen Regions of Greece, administrative regions of Greece. It consists of the northeastern parts of the country, comprising the eastern part of the Geographic regions of Greece, region of ...

, where there were several limited attacks from withdrawing German troops in the middle of September. Bulgaria hoped to keep these territories after the war. The Soviet Union initially also believed it was possible to include at least Western Thrace in the post-war borders of Bulgaria and thereby to secure a strategic outlet to the Aegean Sea. But the United Kingdom, whose troops advanced towards Greece at the same time, stated that the withdrawal of Bulgarian troops from all occupied territories was a precondition for a ceasefire agreement with Bulgaria. As result on 10 October, the Bulgarian army and administration began evacuating and after two weeks withdrew from the area. Meanwhile, around 90,000 Bulgarians left the area, nearly half of them settlers and the rest locals. The administrative power was handed over by the already ruling

Bulgarian communist partisans to local subdivisions of ELAS.

In 1945 the former Bulgarian authorities, including those in Greece, were put on trial before "

People's Courts" in post-war Bulgaria for their actions during the war. In general thousands of people were sentenced to prison, while ca. 2,000 received death sentences.

Regional level policies

Many

Slavophones of Macedonia, in particular of Kastoria and Florina provinces, collaborated with Axis forces and came out openly for Bulgaria. These Slavophones considered themselves Bulgarian. In the first two years of occupation, a group of this community believed that the Axis would win the war, spelling the demise of Greek rule in the region and its annexation by Bulgaria.

The first non-communist resistance organization that emerged in the area had as main opponents members of the Aromanian- and Slav-speaking minorities, as well as the communists, rather than the Germans themselves.

Because of the strong presence of German troops and the general distrust of Slavophones by the Greeks, the communist organisations EAM and ELAS had difficulties in Florina and Kastoria.

The majority of the Slav-speakers in Macedonia after mid-1943 joined EAM and were allowed to retain their organization. In October 1944 they deserted and departed to Yugoslavia. In November 1945, after the end of the war, some of then tried to capture

Florina

Florina (, ''Flórina''; known also by some alternative names) is a town and municipality in the mountainous northwestern Macedonia, Greece. Its motto is, 'Where Greece begins'.

The town of Florina is the capital of the Florina regional uni ...

but were repulsed by the ELAS.

Nazi atrocities

Increasing attacks by partisans in the latter years of the occupation resulted in a number of executions and wholesale slaughter of civilians in reprisal. In total, the Germans executed some 21,000 Greeks, the Bulgarians executed some 40,000 and the Italians executed some 9,000. By June 1944, between them the Axis powers had "raided 1,339 towns, boroughs and villages, of which 879, or two-thirds, were completely wiped out, leaving more than a million people homeless" (P. Voglis) in the course of their anti-partisan sweeps, mostly in the areas of

Central Greece,

Western Macedonia

Western Macedonia (, ) is one of the thirteen Regions of Greece, administrative regions of Greece, consisting of the western part of Macedonia (Greece), Macedonia. Located in north-western Greece, it is divided into the regional units of Greece ...

and the Bulgarian occupation zone.

The most infamous examples in the German zone are those of the village of

Kommeno

Kommeno () is a village and a former community in the Arta regional unit, Epirus, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Nikolaos Skoufas, of which it is a municipal unit. The municipal unit has an area of ...

on 16 August 1943, where 317 inhabitants were executed by the

1. ''Gebirgs-Division'' and the village torched; the "

Holocaust of Viannos

The Viannos massacres () were a mass extermination campaign launched by German forces against the civilian residents of around 20 villages located in the areas of east Viannos and west Ierapetra provinces on the Greek island of Crete during Worl ...

" on 14–16 September 1943, in which over 500 civilians from several villages in the region of

Viannos

Viannos () is a municipality in the Heraklion regional unit, Crete, Greece. The municipality has an area of . Population 4,436 (2021). The seat of the municipality is in Ano Viannos.

In September 1943, German occupation forces inflicted heavy lo ...

and

Ierapetra

Ierapetra (; ancient name: ) is a Greece, Greek city and municipality located on the southeast coast of Crete.

History

The town of Ierapetra (in the local dialect: Γεράπετρο ''Gerapetro'') is located on the southeast coast of Crete, sit ...

in

Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

were executed by the

22. ''Luftlande Infanterie-Division''; the "

Massacre of Kalavryta

The Kalavryta massacre (), or the Holocaust of Kalavryta (), was the near-extermination of the male population and the total destruction of the town of Kalavryta, Axis-occupied Greece, by the 117th Jäger Division (Wehrmacht) during World War II, ...

" on 13 December 1943, in which

Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

troops of the

117th Jäger Division

117th Jäger Division was a German infantry division of World War II. The division was formed in April 1943 by the reorganization and redesignation of the 717th Infantry Division. The 717th Division had been formed in April 1941. It was transfe ...

carried out the extermination of the entire male population and the subsequent total destruction of the town; the "

Distomo massacre

The Distomo massacre (; or the ''Distomo-Massaker'') was a Nazi war crime which was perpetrated by members of the Waffen-SS in the village of Distomo, Greece, in 1944, during the German occupation of Greece during World War II.

Background

The ...

" on 10 June 1944, where units of the

Waffen-SS ''Polizei'' Division looted and burned the village of

Distomo :"Distomo" ''may also refer to a work by Federico García Lorca''

Distomo () is a town in western Boeotia, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Distomo-Arachova-Antikyra, of which it is the seat and a muni ...

in

Boeotia

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinisation of names, Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia (; modern Greek, modern: ; ancient Greek, ancient: ), is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the modern regions of Greece, region of Central Greece (adm ...

resulting in the deaths of 218 civilians; the 3 October 1943 "

Lingiades massacre" where the German army murdered in reprisal nearly 100 people in the village of Lingiades, 13 kilometres outside

Ioannina

Ioannina ( ' ), often called Yannena ( ' ) within Greece, is the capital and largest city of the Ioannina (regional unit), Ioannina regional unit and of Epirus (region), Epirus, an Modern regions of Greece, administrative region in northwester ...

; and the "

Holocaust of Kedros

The Holocaust of Kedros (), also known as the Holocaust of Amari (), was the mass murder of the civilian residents of nine villages located in the Amari Valley on the Greek island of Crete during its Axis occupation of Greece during World War II, ...

" on 22 August 1944 in Crete, where 164 civilians were executed and nine villages were dynamited after being looted. At the same time, in the course of the concerted anti-guerrilla campaign, hundreds of villages were systematically torched and almost 1,000,000 Greeks left homeless.

Two other notable acts of brutality were the massacres of Italian troops at the islands of

Cephalonia

Kefalonia or Cephalonia (), formerly also known as Kefallinia or Kephallonia (), is the largest of the Ionian Islands in western Greece and the 6th-largest island in Greece after Crete, Euboea, Lesbos, Rhodes and Chios. It is also a separate regio ...

and

Kos

Kos or Cos (; ) is a Greek island, which is part of the Dodecanese island chain in the southeastern Aegean Sea. Kos is the third largest island of the Dodecanese, after Rhodes and Karpathos; it has a population of 37,089 (2021 census), making ...

in September 1943, during the German takeover of the Italian occupation areas. In Cephalonia, the 12,000-strong Italian

33rd Infantry Division "Acqui" was attacked on 13 September by elements of the 1. ''Gebirgs-Division'' with support from

Stuka

The Junkers Ju 87, popularly known as the "Stuka", is a German dive bomber and ground-attack aircraft. Designed by Hermann Pohlmann, it first flew in 1935. The Ju 87 made its combat debut in 1937 with the Luftwaffe's Condor Legion during the ...

s, and forced to surrender on 21 September after suffering some 1,300 casualties. The next day, the Germans

began executing their prisoners and did not stop until more than 4,500 Italians had been shot. The 4,000 or so survivors were put aboard ships for the mainland, but some of them sank after hitting mines in the

Ionian Sea

The Ionian Sea (, ; or , ; , ) is an elongated bay of the Mediterranean Sea. It is connected to the Adriatic Sea to the north, and is bounded by Southern Italy, including Basilicata, Calabria, Sicily, and the Salento peninsula to the west, ...

, where another 3,000 were lost. The Cephalonia massacre serves as the background for the novel ''

Captain Corelli's Mandolin

''Captain Corelli's Mandolin'', released simultaneously in the United States as ''Corelli's Mandolin'', is a 1994 novel by the British writer Louis de Bernières, set on the Greek island of Cephalonia during the Italian and German occupation ...

''.

Collaboration

Government

The Third Reich had no long-term plans for Greece and Hitler had already decided that a domestic puppet regime would be the least expensive drain on German efforts and resources as the invasion of the Soviet Union was imminent. According to a report by Foreign Office delegate of the

12th Army, Felix Benzler, the formation of a puppet government wasn't an easy task "because it is very difficult to persuade qualified civilians to participate in any form". The most influential Greek personalities hardly wished to make their re-entry into public life at such a moment, while archbishop

Chrysanthos of Athens refused to swear such an Axis puppet.

[ Suspicious of the Greeks' capacity for causing problems, the Axis decided to withhold international recognition from the new regime, which remained without a Foreign Minister for its entire lifetime.][Mazower, 1993, p. 20]

General Georgios Tsolakoglou

Georgios Tsolakoglou (; April 1886 – 22 May 1948) was a Greek army officer who headed the government of Greece from 1941 to 1942, in the early phase of the country's occupation by Axis powers during World War II.

An officer of the Hellenic Ar ...

– who had signed the armistice treaty with the ''Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...