Italian literature is written in the

Italian language

Italian (, , or , ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European language family. It evolved from the colloquial Latin of the Roman Empire. Italian is the least divergent language from Latin, together with Sardinian language, Sardinian. It is ...

, particularly within

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

. It may also refer to literature written by

Italians

Italians (, ) are a European peoples, European ethnic group native to the Italian geographical region. Italians share a common Italian culture, culture, History of Italy, history, Cultural heritage, ancestry and Italian language, language. ...

or in

other languages spoken in Italy, often languages that are closely related to

modern Italian, including

regional varieties and vernacular dialects.

Italian literature began in the 12th century, when in different regions of the

peninsula

A peninsula is a landform that extends from a mainland and is only connected to land on one side. Peninsulas exist on each continent. The largest peninsula in the world is the Arabian Peninsula.

Etymology

The word ''peninsula'' derives , . T ...

the Italian vernacular started to be used in a literary manner. The ''

Ritmo laurenziano'' is the first extant document of Italian literature. In 1230, the

Sicilian School became notable for being the first style in standard Italian.

Renaissance humanism developed during the 14th and the beginning of the 15th centuries.

Lorenzo de' Medici

Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici (), known as Lorenzo the Magnificent (; 1 January 1449 – 9 April 1492), was an Italian statesman, the ''de facto'' ruler of the Florentine Republic, and the most powerful patron of Renaissance culture in Italy. Lore ...

is regarded as the standard bearer of the influence of

Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

on the Renaissance in the

Italian states. The development of the

drama

Drama is the specific Mode (literature), mode of fiction Mimesis, represented in performance: a Play (theatre), play, opera, mime, ballet, etc., performed in a theatre, or on Radio drama, radio or television.Elam (1980, 98). Considered as a g ...

in the 15th century was very great. In the 16th century, the fundamental characteristic of the era following the end of the Renaissance was that it perfected the Italian character of its language.

Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli (3 May 1469 – 21 June 1527) was a Florentine diplomat, author, philosopher, and historian who lived during the Italian Renaissance. He is best known for his political treatise '' The Prince'' (), writte ...

and

Francesco Guicciardini were the chief originators of the science of history.

Pietro Bembo

Pietro Bembo, (; 20 May 1470 – 18 January 1547) was a Venetian scholar, poet, and literary theory, literary theorist who also was a member of the Knights Hospitaller and a cardinal of the Catholic Church. As an intellectual of the Italian Re ...

was an influential figure in the development of the

Italian language

Italian (, , or , ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European language family. It evolved from the colloquial Latin of the Roman Empire. Italian is the least divergent language from Latin, together with Sardinian language, Sardinian. It is ...

. In 1690, the

Academy of Arcadia was instituted with the goal of "restoring" literature by imitating the simplicity of the ancient shepherds with

sonnet

A sonnet is a fixed poetic form with a structure traditionally consisting of fourteen lines adhering to a set Rhyme scheme, rhyming scheme. The term derives from the Italian word ''sonetto'' (, from the Latin word ''sonus'', ). Originating in ...

s,

madrigals, ''

canzonette'', and

blank verse

Blank verse is poetry written with regular metre (poetry), metrical but rhyme, unrhymed lines, usually in iambic pentameter. It has been described as "probably the most common and influential form that English poetry has taken since the 16th cen ...

s.

In the 18th century, the political condition of the Italian states began to improve, and philosophers disseminated their writings and ideas throughout Europe during the

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

. The leading figure of the 18th century Italian literary revival was

Giuseppe Parini. The philosophical, political, and socially progressive ideas behind the

French Revolution of 1789 gave a special direction to Italian literature in the second half of the 18th century, inaugurated with the publication of ''

Dei delitti e delle pene'' by

Cesare Beccaria. Love of liberty and desire for equality created a literature aimed at national objects. Patriotism and classicism were the two principles that inspired the literature that began with the Italian dramatist and poet

Vittorio Alfieri. The

Romantic movement

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

had as its organ the ''Conciliatore'', established in 1818 at Milan. The main instigator of the reform was the Italian poet and novelist

Alessandro Manzoni

Alessandro Francesco Tommaso Antonio Manzoni (, , ; 7 March 1785 – 22 May 1873) was an Italian poet, novelist and philosopher.

He is famous for the novel ''The Betrothed (Manzoni novel), The Betrothed'' (orig. ) (1827), generally ranked among ...

. The great Italian poet of the age was

Giacomo Leopardi. The literary movement that preceded and was contemporary with the

political revolutions of 1848 may be said to be represented by four writers:

Giuseppe Giusti,

Francesco Domenico Guerrazzi,

Vincenzo Gioberti, and

Cesare Balbo.

After the ''

Risorgimento'', political literature became less important. The first part of this period is characterized by two divergent trends of literature that both opposed Romanticism: the ''

Scapigliatura

''Scapigliatura'' () is the name of an artistic movement that developed in Italy after the Risorgimento period (1815–71). The movement included poets, writers, musicians, painters and sculptors. The term Scapigliatura is the Italian equivalent ...

'' and ''

Verismo''. Important early 20th century Italian writers include

Giovanni Pascoli,

Italo Svevo,

Gabriele D'Annunzio,

Umberto Saba,

Giuseppe Ungaretti,

Eugenio Montale, and

Luigi Pirandello.

Neorealism was developed by

Alberto Moravia

Alberto Pincherle (; 28 November 1907 – 26 September 1990), known by his pseudonym Alberto Moravia ( , ), was an Italian novelist and journalist. His novels explored matters of modern sexuality, social alienation and existentialism. Moravia i ...

.

Pier Paolo Pasolini became notable for being one of the most controversial authors in the history of Italy.

Umberto Eco became internationally successful with the Medieval detective story ''

Il nome della rosa'' (1980). The Nobel Prize in Literature has been awarded to Italian language authors six times (as of 2019) with winners including

Giosuè Carducci,

Grazia Deledda,

Luigi Pirandello,

Salvatore Quasimodo,

Eugenio Montale, and

Dario Fo.

Early medieval Latin literature

As the

Western Roman Empire

In modern historiography, the Western Roman Empire was the western provinces of the Roman Empire, collectively, during any period in which they were administered separately from the eastern provinces by a separate, independent imperial court. ...

declined, the Latin tradition was kept alive by writers such as

Cassiodorus

Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (c. 485 – c. 585), commonly known as Cassiodorus (), was a Christian Roman statesman, a renowned scholar and writer who served in the administration of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths. ''Senato ...

,

Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known simply as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480–524 AD), was a Roman Roman Senate, senator, Roman consul, consul, ''magister officiorum'', polymath, historian, and philosopher of the Early Middl ...

, and

Symmachus. The liberal arts flourished at

Ravenna

Ravenna ( ; , also ; ) is the capital city of the Province of Ravenna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. It was the capital city of the Western Roman Empire during the 5th century until its Fall of Rome, collapse in 476, after which ...

under

Theodoric

Theodoric is a Germanic given name. First attested as a Gothic name in the 5th century, it became widespread in the Germanic-speaking world, not least due to its most famous bearer, Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths.

Overview

The name w ...

, and the Gothic kings surrounded themselves with masters of

rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

and of

grammar

In linguistics, grammar is the set of rules for how a natural language is structured, as demonstrated by its speakers or writers. Grammar rules may concern the use of clauses, phrases, and words. The term may also refer to the study of such rul ...

. Some lay schools remained in Italy, and noted scholars included

Magnus Felix Ennodius,

Arator,

Venantius Fortunatus,

Felix the Grammarian,

Peter of Pisa,

Paulinus of Aquileia, and many others.

The later establishment of the medieval universities of

Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

,

Padua

Padua ( ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Veneto, northern Italy, and the capital of the province of Padua. The city lies on the banks of the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice and southeast of Vicenza, and has a population of 20 ...

,

Vicenza

Vicenza ( , ; or , archaically ) is a city in northeastern Italy. It is in the Veneto region, at the northern base of the Monte Berico, where it straddles the Bacchiglione, River Bacchiglione. Vicenza is approximately west of Venice and e ...

,

Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

,

Salerno,

Modena

Modena (, ; ; ; ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) on the south side of the Po Valley, in the Province of Modena, in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy. It has 184,739 inhabitants as of 2025.

A town, and seat of an archbis ...

and

Parma

Parma (; ) is a city in the northern Italian region of Emilia-Romagna known for its architecture, Giuseppe Verdi, music, art, prosciutto (ham), Parmesan, cheese and surrounding countryside. With a population of 198,986 inhabitants as of 2025, ...

helped to spread culture and prepared the ground in which the new

vernacular literature

Vernacular literature is literature written in the vernacular—the speech of the "common people".

In the European tradition, this effectively means literature not written in Latin or Koine Greek. In this context, vernacular literature appeared ...

developed.

Classical traditions did not disappear, and affection for the memory of Rome, a preoccupation with politics, and a preference for practice over theory combined to influence the development of Italian literature.

High medieval literature

Trovatori

The earliest vernacular literary tradition in Italy was in

Occitan, spoken in parts of northwest Italy. A tradition of vernacular

lyric poetry arose in

Poitou

Poitou ( , , ; ; Poitevin: ''Poetou'') was a province of west-central France whose capital city was Poitiers. Both Poitou and Poitiers are named after the Pictones Gallic tribe.

Geography

The main historical cities are Poitiers (historical ...

in the early 12th century and spread south and east, eventually reaching Italy by the end of the 12th century. The first

troubadours

A troubadour (, ; ) was a composer and performer of Old Occitan lyric poetry during the High Middle Ages (1100–1350). Since the word ''troubadour'' is etymologically masculine, a female equivalent is usually called a ''trobairitz''.

The tro ...

(''trovatori'' in Italian), as these Occitan lyric poets were called, to practise in Italy were from elsewhere, but the high aristocracy of the northern Italy was ready to patronise them. It was not long before native Italians adopted Occitan as a vehicle for poetic expression.

Among the early patrons of foreign troubadours were especially the

House of Este, the

Da Romano,

House of Savoy

The House of Savoy (, ) is a royal house (formally a dynasty) of Franco-Italian origin that was established in 1003 in the historical region of Savoy, which was originally part of the Kingdom of Burgundy and now lies mostly within southeastern F ...

, and the

Malaspina.

Azzo VI of Este entertained the troubadours

Aimeric de Belenoi,

Aimeric de Peguilhan,

Albertet de Sestaro, and

Peire Raimon de Tolosa from

Occitania and

Rambertino Buvalelli from

Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

, one of the earliest Italian troubadours. Azzo VI's daughter,

Beatrice, was an object of the early poets "

courtly love". Azzo's son,

Azzo VII, hosted

Elias Cairel and

Arnaut Catalan. Rambertino was named ''

podestà'' of

Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

in 1218 and it was probably during his three-year tenure there that he introduced Occitan lyric poetry to the city, which later developed a flourishing Occitan literary culture.

The

margraves of Montferrat—

Boniface I,

William VI, and

Boniface II—were patrons of Occitan poetry. Among the Genoese troubadours were

Lanfranc Cigala,

Calega Panzan,

Jacme Grils, and

Bonifaci Calvo. Genoa was also the place of the genesis of the ''podestà''-troubadour phenomenon: men who served in several cities as ''podestàs'' on behalf of either the

Guelph or Ghibelline party and who wrote

political poetry in Occitan. Rambertino Buvalelli was the first ''podestà''-troubadour and in Genoa there were the Guelphs

Luca Grimaldi and

Luchetto Gattilusio and the Ghibellines

Perceval

Perceval (, also written Percival, Parzival, Parsifal), alternatively called Peredur (), is a figure in the legend of King Arthur, often appearing as one of the Knights of the Round Table. First mentioned by the French author Chrétien de Tro ...

and

Simon Doria.

Perhaps the most important aspect of the Italian troubadour phenomenon was the production of

chansonniers and the composition of ''

vidas'' and ''

razos''.

Uc de Saint Circ undertook to author the entire ''razo'' corpus and a great many of the ''vidas''. The most famous and influential Italian troubadour was

Sordello.

The troubadours had a connection with the rise of a school of poetry in the

Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily (; ; ) was a state that existed in Sicily and the southern Italian peninsula, Italian Peninsula as well as, for a time, in Kingdom of Africa, Northern Africa, from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 until 1816. It was ...

. In 1220

Obs de Biguli was present as a "singer" at the coronation of the

Emperor Frederick II.

Guillem Augier Novella before 1230 and

Guilhem Figueira thereafter were important Occitan poets at Frederick's court. The

Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade (), also known as the Cathar Crusade (1209–1229), was a military and ideological campaign initiated by Pope Innocent III to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc, what is now southern France. The Crusade was prosecuted pri ...

had devastated

Languedoc

The Province of Languedoc (, , ; ) is a former province of France.

Most of its territory is now contained in the modern-day region of Occitanie in Southern France. Its capital city was Toulouse. It had an area of approximately .

History

...

and forced many troubadours of the area to flee to Italy, where an Italian tradition of papal criticism was begun.

Chivalric romance

The ''Historia de excidio Trojae'', attributed to

Dares Phrygius, claimed to be an eyewitness account of the Trojan War.

Guido delle Colonne of

Messina

Messina ( , ; ; ; ) is a harbour city and the capital city, capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of 216,918 inhabitants ...

, one of the

vernacular

Vernacular is the ordinary, informal, spoken language, spoken form of language, particularly when perceptual dialectology, perceived as having lower social status or less Prestige (sociolinguistics), prestige than standard language, which is mor ...

poets of the Sicilian school, composed the ''

Historia destructionis Troiae''. In his poetry, Guido was an imitator of the

Provençals, but in this book he converted

Benoît de Sainte-Maure's French romance into what sounded like serious Latin history.

Much the same thing occurred with other great legends.

Quilichino of Spoleto wrote

couplets about the legend of

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

. Europe was full of the legend of

King Arthur

According to legends, King Arthur (; ; ; ) was a king of Great Britain, Britain. He is a folk hero and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In Wales, Welsh sources, Arthur is portrayed as a le ...

, but the Italians contented themselves with translating and abridging French romances.

Jacobus de Voragine, while collecting his ''

Golden Legend'' (1260), remained a historian. Farfa,

Marsicano, and other scholars translated

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

, the precepts of the school of

Salerno, and the travels of

Marco Polo

Marco Polo (; ; ; 8 January 1324) was a Republic of Venice, Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known a ...

, linking the classics and the Renaissance.

At the same time, epic poetry was written in a mixed language, a dialect of Italian based on French: hybrid words exhibited a treatment of sounds according to the rules of both languages, had French roots with Italian endings, and were pronounced according to Italian or Latin rules. Examples include the ''

chansons de geste'', ''

Macaire'', the ''

Entrée d'Espagne'' written by Anonymous of

Padua

Padua ( ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Veneto, northern Italy, and the capital of the province of Padua. The city lies on the banks of the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice and southeast of Vicenza, and has a population of 20 ...

, the ''

Prise de Pampelune'', written by

Niccolò of Verona, and others. All this preceded the appearance of purely Italian literature.

Emergence of native vernacular literature

The French and Occitan languages gradually gave way to the native Italian. Hybridism recurred, but it no longer predominated. In the ''Bovo d'Antona'' and the ''Rainaldo e Lesengrino'',

Venetian is clearly felt, although the language is influenced by French forms. These writings, which

Graziadio Isaia Ascoli has called ''miste'' (mixed), immediately preceded the appearance of purely Italian works.

There is evidence that a type of literature already existed before the 13th century: the ''

Ritmo cassinese'', ''

Ritmo di Sant'Alessio'', ''

Laudes creaturarum'', ''

Ritmo lucchese'', ''

Ritmo laurenziano'', ''

Ritmo bellunese'' are classified by

Cesare Segre, et al. as "Archaic Works" ("Componimenti Arcaici"): "such are labelled the first literary works in the Italian vernacular, their dates ranging from the last decades of the 12th century to the early decades of the 13th".

However, as he points out, such early literature does not yet present any uniform stylistic or linguistic traits.

This early development, however, was simultaneous in the whole peninsula, varying only in the subject matter of the art. In the north, the poems of

Giacomino da Verona and

Bonvesin da la Riva were written in a dialect of

Lombard and

Venetian. This sort of composition may have been encouraged by the old custom in the north of Italy of listening to the songs of the

jongleurs.

Sicilian School

The year 1230 marked the beginning of the

Sicilian School and of literature showing more uniform traits. Its importance lies more in the language (the creation of the first standard Italian) than its subject, a love song partly modelled on the Provençal poetry imported to the south by the

Normans

The Normans (Norman language, Norman: ''Normaunds''; ; ) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norsemen, Norse Viking settlers and locals of West Francia. The Norse settlements in West Franc ...

and the

Svevs under

Frederick II.

This poetry differs from the French equivalent in its treatment of the woman, less

erotic and more

platonic, a vein further developed by ''

Dolce Stil Novo'' in later 13th century Bologna and

Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

. The customary repertoire of

chivalry

Chivalry, or the chivalric language, is an informal and varying code of conduct that developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It is associated with the medieval Christianity, Christian institution of knighthood, with knights being members of ...

terms is adapted to Italian

phonotactics

Phonotactics (from Ancient Greek 'voice, sound' and 'having to do with arranging') is a branch of phonology that deals with restrictions in a language on the permissible combinations of phonemes. Phonotactics defines permissible syllable struc ...

, creating new Italian vocabulary. These were adopted by

Dante

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

and his contemporaries, and handed on to future generations of Italian writers.

To the Sicilian school belonged

Enzio, king of

Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

,

Pietro della Vigna,

Inghilfredi,

Guido

Guido is a given name. It has been a male first name in Italy, Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Argentina, the Low Countries, Scandinavia, Spain, Portugal and Latin America, as well as other places with migration from those. Regarding origins, there ...

and

Odo delle Colonne,

Jacopo d'Aquino,

Ruggieri Apugliese,

Giacomo da Lentini,

Arrigo Testa, and others. Most famous is ''Io m'aggio posto in core'', by Giacomo da Lentini, the head of the movement, but there is also poetry written by Frederick himself. Giacomo da Lentini is also credited with inventing the

sonnet

A sonnet is a fixed poetic form with a structure traditionally consisting of fourteen lines adhering to a set Rhyme scheme, rhyming scheme. The term derives from the Italian word ''sonetto'' (, from the Latin word ''sonus'', ). Originating in ...

, a form later perfected by Dante,

Petrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

and

Boccaccio. The

censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governmen ...

imposed by Frederick meant that no political matter entered literary debate. In this respect, the poetry of the north, still divided into

communes or

city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world throughout history, including cities such as Rome, ...

s with relatively democratic governments, provided new ideas. These new ideas are shown in the

Sirventese genre, and later, Dante's

Commedia, full of invectives against contemporary political leaders and popes.

Though the conventional love song prevailed at Frederick's (and later

Manfred's) court, more spontaneous poetry existed in the ''Contrasto'' attributed to

Cielo d'Alcamo. The ''Contrasto'' is probably a scholarly re-elaboration of a lost popular rhyme and is the closest to a type of poetry that perished or was smothered by the ancient Sicilian literature.

The poems of the Sicilian school were written in the first known standard Italian. This was elaborated by these poets under the direction of Frederick II and combines many traits typical of the Sicilian, and to a lesser extent,

Apulia

Apulia ( ), also known by its Italian language, Italian name Puglia (), is a Regions of Italy, region of Italy, located in the Southern Italy, southern peninsular section of the country, bordering the Adriatic Sea to the east, the Strait of Ot ...

n dialects and other southern dialects, with many words of Latin and French origin.

Dante's styles ''illustre, cardinale, aulico, curiale'' were developed from his linguistic study of the Sicilian School, whose technical features had been imported by

Guittone d'Arezzo in

Tuscany

Tuscany ( ; ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of 3,660,834 inhabitants as of 2025. The capital city is Florence.

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, artistic legacy, and its in ...

. The standard changed slightly in Tuscany because Tuscan

scriveners perceived the five-vowel system used by southern Italians as a seven-vowel one. As a consequence, the texts that Italian students read in their anthology contain lines that appear not to rhyme, a feature known as ″Sicilian rhyme" (''rima siciliana'') which was widely used later by poets such as Dante or Petrarch.

Religious literature

The earliest preserved sermons in the Italian language are from

Jordan of Pisa, a Dominican.

Francis of Assisi

Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone ( 1181 – 3 October 1226), known as Francis of Assisi, was an Italians, Italian Mysticism, mystic, poet and Friar, Catholic friar who founded the religious order of the Franciscans. Inspired to lead a Chris ...

, the founder of the Franciscans, also wrote poetry. According to legend, Francis dictated the

hymn

A hymn is a type of song, and partially synonymous with devotional song, specifically written for the purpose of adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification. The word ''hymn'' d ...

''Cantico del Sole'' in the eighteenth year of his penance. It was the first great poetical work of northern Italy, written in a type of verse marked by

assonance, a poetic device more widespread in Northern Europe.

Jacopone da Todi was a poet who represented the religious feeling that had made special progress in

Umbria

Umbria ( ; ) is a Regions of Italy, region of central Italy. It includes Lake Trasimeno and Cascata delle Marmore, Marmore Falls, and is crossed by the Tiber. It is the only landlocked region on the Italian Peninsula, Apennine Peninsula. The re ...

. Jacopone was possessed by St. Francis's mysticism, but was also a satirist who mocked the

corruption

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense that is undertaken by a person or an organization that is entrusted in a position of authority to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's gain. Corruption may involve activities ...

and

hypocrisy of the Church. The religious movement in Umbria was followed by another literary phenomenon, the religious drama. In 1258 a hermit,

Raniero Fasani, represented himself as sent by God to disclose mysterious visions, and to announce to the world terrible visitations. Fasani's pronouncements stimulated the formation of the

Compagnie di Disciplinanti, who, for a penance, scourged themselves until they drew blood, and sang ''

Laudi'' in dialogue in their

confraternities. These ''laudi'', closely connected with the

liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and participation in the sacred through activities reflecting praise, thanksgiving, remembra ...

, were the first example of drama in the vernacular tongue of Italy. They were written in the

Umbrian dialect, in verses of eight syllables. As early as the end of the 13th century the ''Devozioni del Giovedi e Venerdi Santo'' appeared, mixing liturgy and drama. Later, ''di un Monaco che andò al servizio di Dio'' ('of a monk who entered the service of God') approached the definite form the religious drama would assume in the following centuries.

First Tuscan literature

13th century Tuscans spoke a dialect that closely resembled Latin and afterwards became, almost exclusively, the language of literature, and which was already regarded at the end of the 13th century as surpassing other dialects. In Tuscany, too, popular love poetry existed. A school of imitators of the Sicilians was led by

Dante da Majano, but its literary originality took another line—that of humorous and satirical poetry. The entirely democratic form of government created a style of poetry that stood strongly against the medieval mystic and chivalrous style. The sonnets of

Rustico di Filippo are half-fun and half-satire, as is the work of

Cecco Angiolieri of Siena, the oldest known humorist.

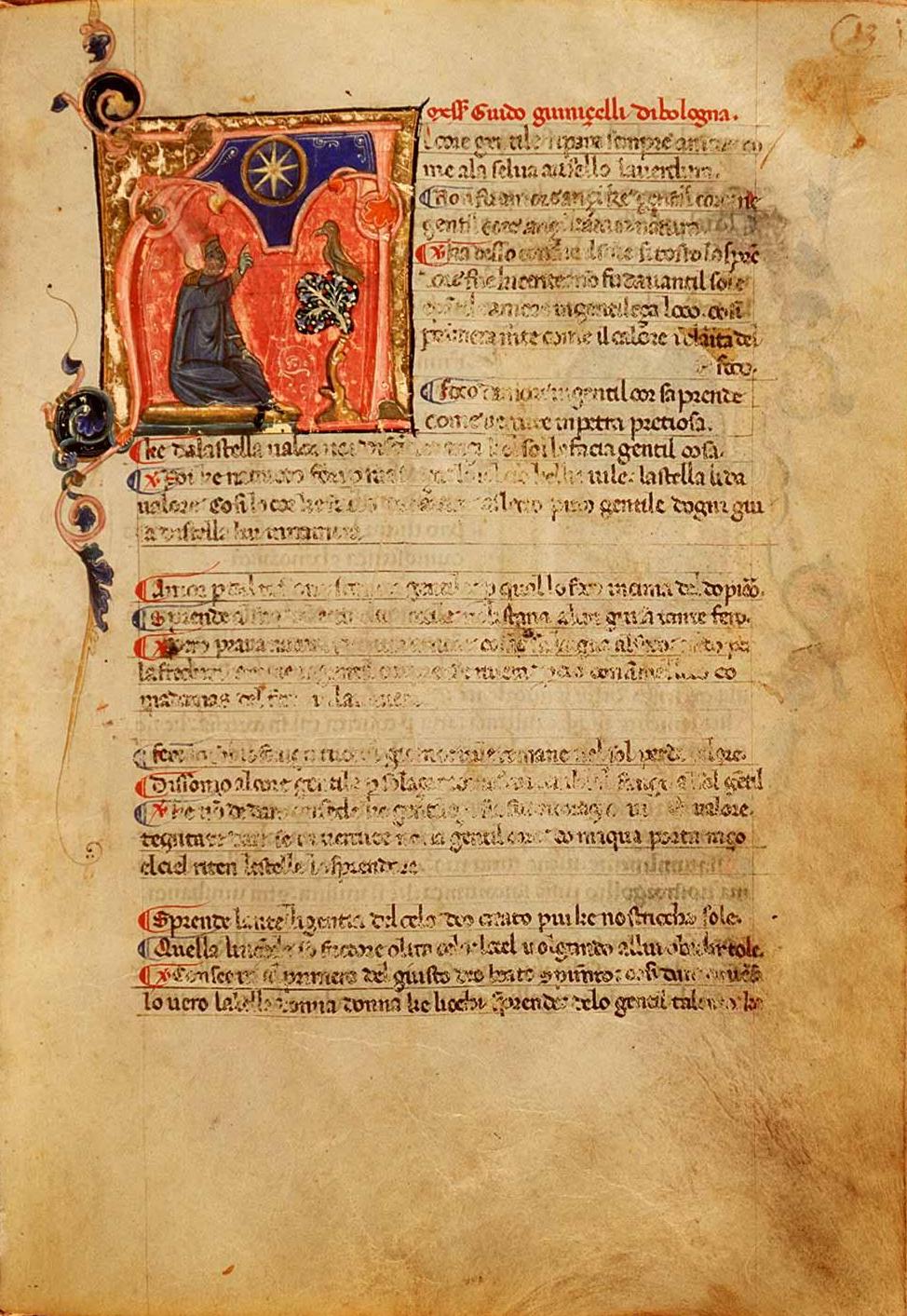

Another type of poetry also began in Tuscany. Guittone d'Arezzo made art quit chivalry and Provençal forms for national motives and Latin forms. He attempted political poetry and prepared the way for the Bolognese school. Bologna was the city of science, and

philosophical poetry appeared there.

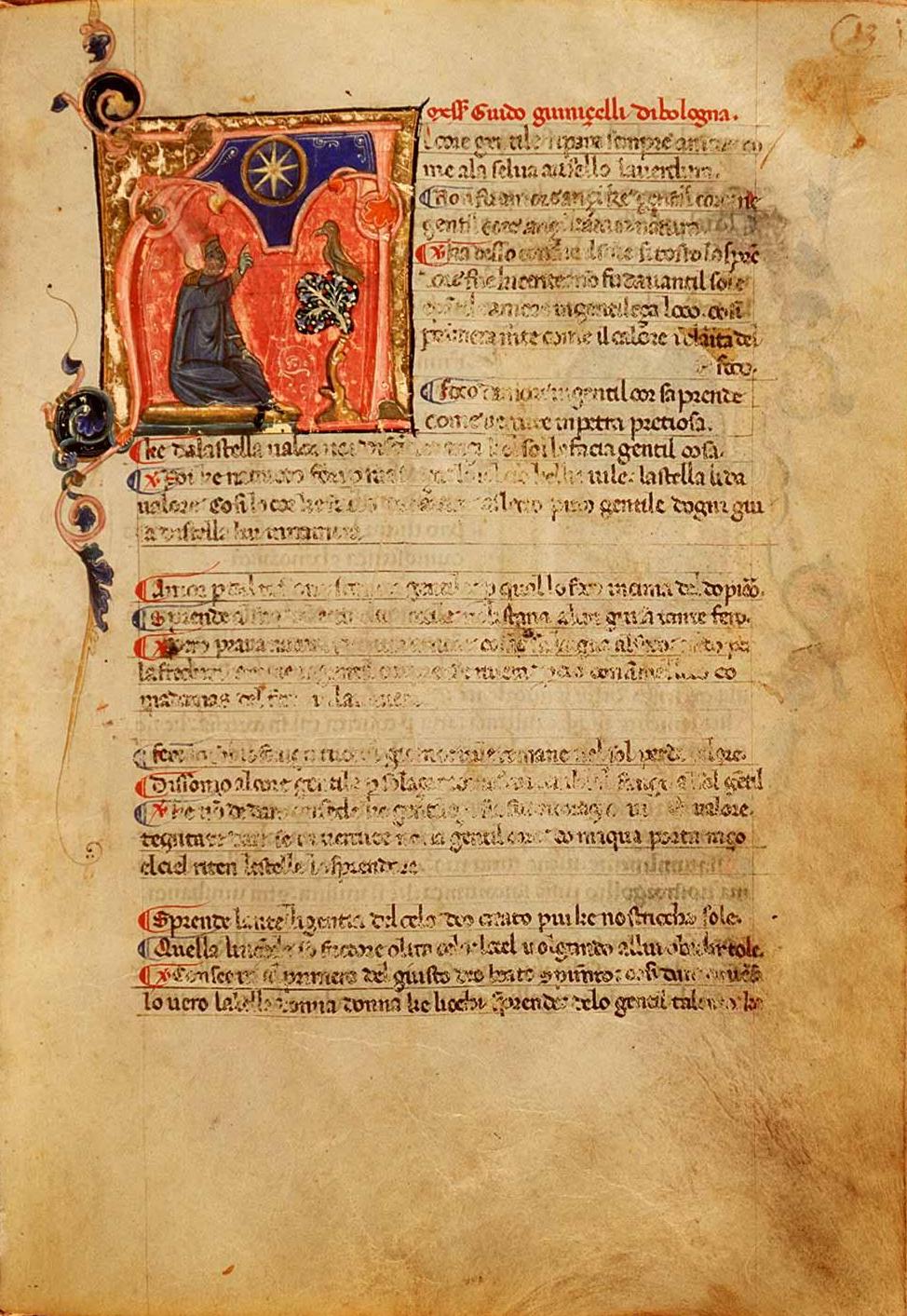

Guido Guinizelli was the poet after the new fashion of the art. In his work, the ideas of chivalry are changed and enlarged. Guinizelli's ''

Canzoni'' make up the bible of Dolce Stil Novo, and one in particular, "Al cor gentil" ('To a Kind Heart'), is considered the manifesto of the new movement that bloomed in Florence under Cavalcanti, Dante, and their followers. He marks a great development in the history of Italian art, especially because of his close connection with Dante's

lyric poetry.

In the 13th century, there were several major

allegorical poems. One of these is by

Brunetto Latini: his ''Tesoretto'' is a short poem, in seven-syllable verses, rhyming in couplets, in which the author is lost in a wilderness and meets a lady, who represents Nature and gives him much instruction.

Francesco da Barberino wrote two little allegorical poems, the ''Documenti d'amore'' and ''Del reggimento e dei costumi delle donne''. The poems today are generally studied not as literature, but for historical context.

In the 15th century, humanist and publisher

Aldus Manutius

Aldus Pius Manutius (; ; 6 February 1515) was an Italian printer and Renaissance humanism, humanist who founded the Aldine Press. Manutius devoted the later part of his life to publishing and disseminating rare texts. His interest in and preser ...

published Tuscan poets

Petrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

and

Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

(''Divine Comedy''), creating the model for what became a standard for modern Italian.

Development of early prose

Italian prose of the 13th century was as abundant and varied as its poetry. Halfway through the century, a certain Aldobrando or Aldobrandino wrote a book for

Beatrice of Savoy, called ''Le Régime du corps''. In 1267

Martino da Canale wrote a history of Venice in the same Old French (''

langue d'oïl'').

Rustichello da Pisa composed many chivalrous romances, derived from the

Arthurian cycle, and subsequently wrote the ''

Travels of Marco Polo'', which may have been dictated by Polo himself. And finally

Brunetto Latini wrote his ''Tesoro'' in French. Latini also wrote some works in Italian prose such as ''La rettorica'', an adaptation from

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

's ''

De inventione'', and translated three orations from Cicero. Another important writer was the Florentine judge

Bono Giamboni, who translated

Orosius's ''Historiae adversus paganos'',

Vegetius's ''

Epitoma rei militaris'', made a translation/adaptation of Cicero's ''De inventione'' mixed with the ''

Rethorica ad Erennium'', and a translation/adaptation of

Innocent III

Pope Innocent III (; born Lotario dei Conti di Segni; 22 February 1161 – 16 July 1216) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 until his death on 16 July 1216.

Pope Innocent was one of the most power ...

's ''De miseria humane conditionis''. He also wrote an allegorical novel called ''Libro de' Vizi e delle Virtudi''.

Andrea of Grosseto, in 1268, translated three Treaties of

Albertanus of Brescia, from Latin to

Tuscan.

After the original compositions in the ''langue d'oïl'' came translations or adaptations from the same. There are some moral narratives taken from religious legends, a romance of

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

, some short histories of ancient knights, the ''

Tavola rotonda'', translations of the ''Viaggi'' of

Marco Polo

Marco Polo (; ; ; 8 January 1324) was a Republic of Venice, Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known a ...

, and of Latini's ''Tesoro''. At the same time, translations from Latin of moral and ascetic works, histories, and treatises on

rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

and

oratory appeared. Also noteworthy is ''Composizione del mondo'', a scientific book by

Ristoro d'Arezzo, who lived about the middle of the 13th century.

Another short treatise exists: ''De regimine rectoris'', by

Fra Paolino, a

Minorite friar of Venice, who was

bishop of Pozzuoli, and who also wrote a Latin chronicle. His treatise stands in close relation to that of

Egidio Colonna, ''De regimine principum''. It is written in

Venetian.

The 13th century was very rich in tales. A collection called the ''Cento Novelle antiche'' contains stories drawn from many sources, including Asian, Greek and Trojan traditions, ancient and medieval history, the legends of

Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

,

Provence

Provence is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which stretches from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the France–Italy border, Italian border to the east; it is bordered by the Mediterrane ...

and Italy, the

Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

, local Italian traditions, and histories of animals and old

mythology

Myth is a genre of folklore consisting primarily of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society. For scholars, this is very different from the vernacular usage of the term "myth" that refers to a belief that is not true. Instead, the ...

.

On the whole the Italian novels of the 13th century have little originality, and are a faint reflection of the very rich legendary

literature of France. Some attention should be paid to the ''Lettere'' of Fra Guittone d'Arezzo, who wrote many poems and also some letters in prose, the subjects of which are moral and religious. Guittone's love of antiquity and the traditions of Rome and its language was so strong that he tried to write Italian in a Latin style. The letters are obscure, involved and altogether barbarous. Guittone took as his special model

Seneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger ( ; AD 65), usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoicism, Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, a dramatist, and in one work, a satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Seneca ...

,

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

,

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

,

Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known simply as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480–524 AD), was a Roman Roman Senate, senator, Roman consul, consul, ''magister officiorum'', polymath, historian, and philosopher of the Early Middl ...

and

Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

. Guittone viewed his style as very artistic, but later scholars view it as extravagant and grotesque.

Dolce Stil Novo

With the school of

Lapo Gianni,

Guido Cavalcanti

Guido Cavalcanti (between 1250 and 1259 – August 1300) was an Italians, Italian poet. He was also a friend of and intellectual influence on Dante Alighieri.

Historical background

Cavalcanti was born in Florence at a time when the comune was b ...

,

Cino da Pistoia and

Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

, lyric poetry became exclusively Tuscan. The whole novelty and poetic power of this school, consisted in, according to Dante, ''Quando Amore spira, noto, ed a quel niodo Ch'ei detta dentro, vo significando'': that is, in a power of expressing the feelings of the soul in the way in which love inspires them, in an appropriate and graceful manner, fitting form to matter, and by art fusing one with the other. This a neo-platonic approach widely endorsed by ''

Dolce Stil Novo'', and although in Cavalcanti's case, it can be upsetting and even destructive, it is nonetheless a metaphysical experience able to lift man onto a higher, spiritual dimension. Gianni's new style was still influenced by the Siculo-Provençal school.

Cavalcanti's poems fall into two classes: those that portray the philosopher (''il sottilissimo dialettico'', as

Lorenzo the Magnificent called him) and those more directly the product of his poetic nature imbued with

mysticism

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute (philosophy), Absolute, but may refer to any kind of Religious ecstasy, ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or Spirituality, spiritual meani ...

and

metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

. To the first set belongs the famous poem ''Sulla natura d'amore'', which in fact is a treatise on amorous

metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

, and was annotated later in a learned way by renowned Platonic philosophers of the 15th century, such as

Marsilius Ficinus and others. On the other hand, in his ''Ballate'', he pours himself out ingenuously, but with a consciousness of his art. The greatest of these is considered to be the ''ballata'' composed by Cavalcanti when he was banished from Florence with the party of the Bianchi in 1300, and took refuge at

Sarzana.

14th century: the roots of Renaissance

Dante

Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

, one of the greatest of Italian poets, also shows these lyrical tendencies. In 1293 he wrote ''

La Vita Nuova'', in which he idealizes love. It is a collection of poems to which Dante added narration and explication. Everything is sensual, aerial, and heavenly, and the real Beatrice is supplanted by an idealized vision of her, losing her human nature and becoming a representation of the divine.

The ''

Divine Comedy

The ''Divine Comedy'' (, ) is an Italian narrative poetry, narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun and completed around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature and one of ...

'' tells of the poet's travels through the three realms of the dead—

Hell

In religion and folklore, hell is a location or state in the afterlife in which souls are subjected to punishment after death. Religions with a linear divine history sometimes depict hells as eternal destinations, such as Christianity and I ...

,

Purgatory

In Christianity, Purgatory (, borrowed into English language, English via Anglo-Norman language, Anglo-Norman and Old French) is a passing Intermediate state (Christianity), intermediate state after physical death for purifying or purging a soul ...

, and

Paradise

In religion and folklore, paradise is a place of everlasting happiness, delight, and bliss. Paradisiacal notions are often laden with pastoral imagery, and may be cosmogonical, eschatological, or both, often contrasted with the miseries of human ...

—accompanied by the Latin poet

Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

. An allegorical meaning hides under the literal one of this great epic. Dante, travelling through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise, symbolizes mankind aiming at the double object of temporal and eternal happiness. The forest where the poet loses himself lost symbolizes sin. The mountain illuminated by the sun is the universal monarchy. Envy is Florence, Pride is the house of France, and Avarice is the papal court. Virgil represents reason and the empire. Beatrice is the symbol of the supernatural aid mankind must have to attain the supreme end, which is God.

The merit of the poem lies is the individual art of the poet, the classic art transfused for the first time into a Romance form. Whether he describes nature, analyses passions, curses the vices or sings hymns to the virtues, Dante is notable for the grandeur and delicacy of his art. He took the materials for his poem from

theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

, philosophy, history, and mythology, but especially from his own passions, from hatred and love. The ''Divine Comedy'' ranks among the finest works of

world literature.

Petrarch

Petrarch was the first

humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

, and he was at the same time the first modern lyric poet. His career was long and tempestuous. He lived for many years at

Avignon

Avignon (, , ; or , ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the Communes of France, commune had a ...

, cursing the corruption of the papal court; he travelled through nearly the whole of Europe; he corresponded with emperors and popes, and he was considered the most important writer of his time. Petrarch's lyric verse is quite different, not only from that of the Provençal

troubadours and the Italian poets before him, but also from the lyrics of Dante. Petrarch is a psychological poet, who examines all his feelings and renders them with an art of exquisite sweetness. The lyrics of Petrarch are no longer transcendental like Dante's, but keep entirely within human limits.

The ''Canzoniere'' includes a few political poems, one supposed to be addressed to

Cola di Rienzi and several sonnets against the court of Avignon. These are remarkable for their vigour of feeling, and also for showing that, compared to Dante, Petrarch had a sense of a broader Italian consciousness.

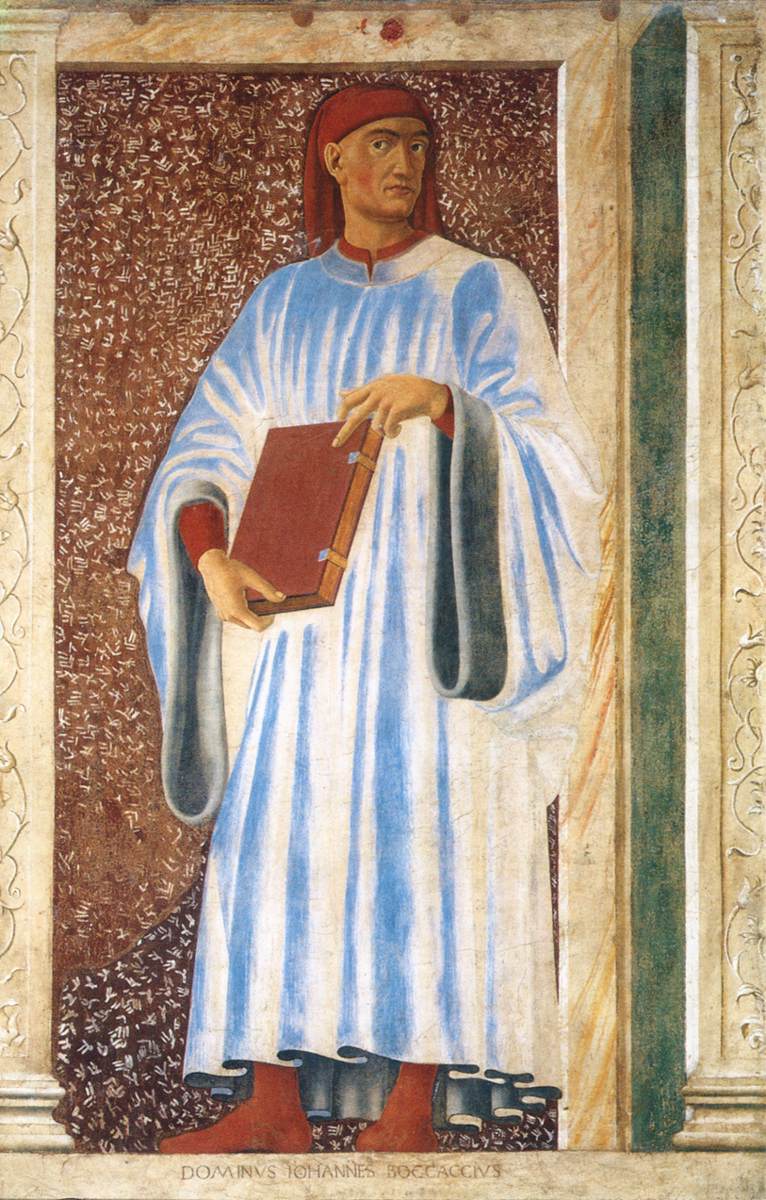

Boccaccio

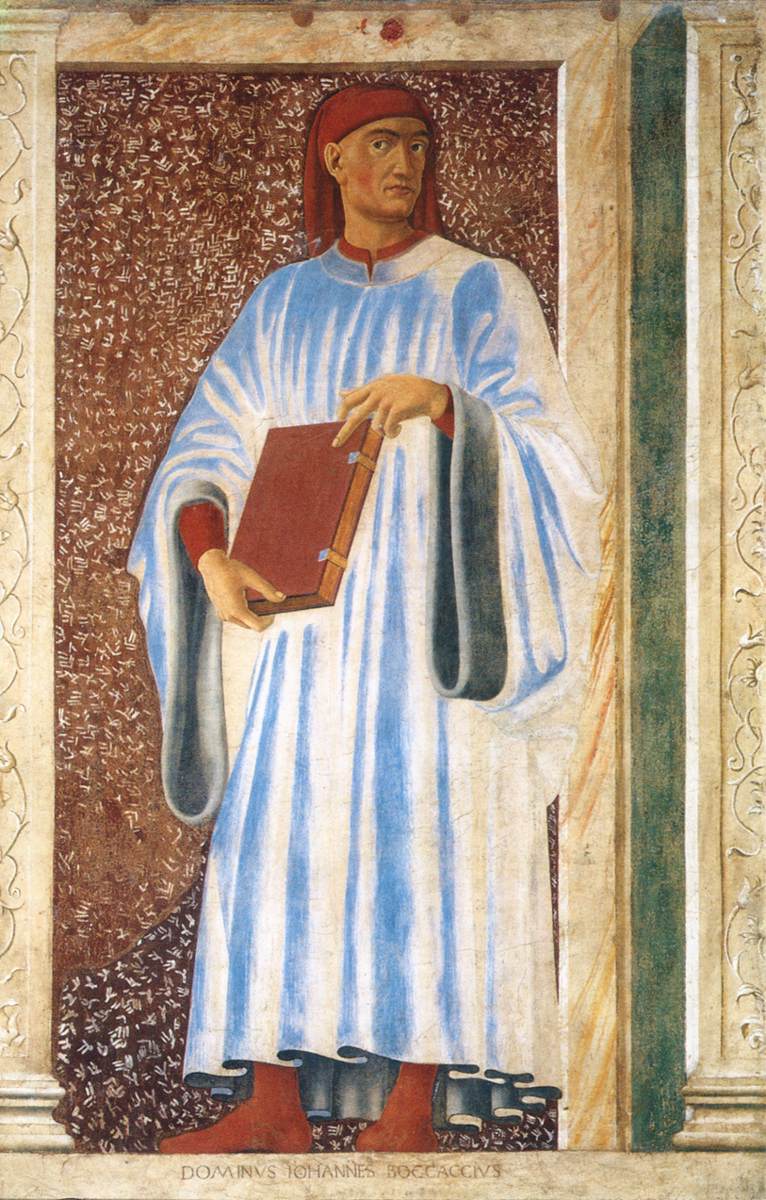

Giovanni Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio had the same enthusiastic love of antiquity and the same worship for the new Italian literature as Petrarch.

He was the first to put together a Latin translation of the ''

Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

'' and, in 1375, the ''

Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; ) is one of two major epics of ancient Greek literature attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest surviving works of literature and remains popular with modern audiences. Like the ''Iliad'', the ''Odyssey'' is divi ...

''. His classical learning was shown in the work ''De genealogia deorum''; as

A. H. Heeren said, it is an encyclopaedia of mythological knowledge; and it was the precursor of the

humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

movement of the 15th century. Boccaccio was also the first historian of women in his ''

De mulieribus claris'', and the first to tell the story of the great unfortunates in his ''

De casibus virorum illustrium''. He continued and perfected former geographical investigations in his ''De montibus, silvis, fontibus, lacubus, fluminibus, stagnis, et paludibus, et de nominibus maris'', for which he made use of

Vibius Sequester.

He did not invent the

octave stanza, but was the first to use it in a work of length and artistic merit, his ''

Teseide'', the oldest Italian romantic poem. The ''

Filostrato'' relates the loves of Troiolo and Griseida (

Troilus and Cressida). The ''

Ninfale fiesolano'' tells the love story of the nymph Mesola and the shepherd Africo. The ''

Amorosa Visione'', a poem in triplets, doubtless owed its origin to the ''Divine Comedy''. The ''

Ameto'' is a mixture of prose and poetry, and is the first Italian pastoral romance.

Boccaccio became famous principally for the Italian work, ''

Decamerone'', a collection of a hundred novels, related by a party of men and women who retired to a villa near Florence to escape the

plague in 1348. Novel writing, so abundant in the preceding centuries, especially in France, now for the first time assumed an artistic shape. The style of Boccaccio tends to the imitation of Latin, but in him, prose first took the form of elaborated art. Over and above this, in the ''Decamerone'', Boccaccio is a delineator of character and an observer of passions. Much has been written about the sources of the novels of the ''Decamerone''. Probably Boccaccio made use both of written and of oral sources.

Others

Imitators

Fazio degli Uberti

Fazio degli Uberti and

Federico Frezzi were imitators of the ''Divine Comedy'', but only in its external form.

Giovanni Fiorentino wrote, under the title of ''Pecorone'', a collection of tales, which are supposed to have been related by a monk and a nun in the parlour of the monastery Novelists of Forli. He closely imitated Boccaccio, and drew on Villani's chronicle for his historical stories.

Franco Sacchetti wrote tales too, for the most part on subjects taken from Florentine history. The subjects are almost always improper, but it is evident that Sacchetti collected these anecdotes so he could draw his own conclusions and moral reflections, which he puts at the end of each story. From this point of view, Sacchetti's work comes near to the Monalisaliones of the Middle Ages. A third novelist was

Giovanni Sercambi of Lucca, who after 1374 wrote a book, in imitation of Boccaccio, about a party of people who were supposed to fly from a plague and to go travelling about in different Italian cities, stopping here and there telling stories. Later, but important, names are those of

Masuccio Salernitano (Tommaso Guardato), who wrote the ''Novellino'', and

Antonio Cornazzano whose ''Proverbii'' became extremely popular.

Chronicles

Chronicles formerly believed to have been of the 13th century are now mainly regarded as forgeries. At the end of the 13th century there is a chronicle by

Dino Compagni, probably authentic.

Giovanni Villani, born in 1300, was more of a chronicler than a historian. He relates the events up to 1347. The journeys that he made in Italy and France, and the information thus acquired, mean that his chronicle, the ''Historie Fiorentine'', covers events all over Europe. Matteo was the brother of Giovanni Villani, and continued the chronicle up to 1363. It was again continued by Filippo Villani.

Ascetics

St

Catherine of Siena's mysticism was political. She aspired to bring back the Church of Rome to evangelical virtue, and left a collection of letters written to all types of people, including popes.

Another Sienese,

Giovanni Colombini, founder of the order of

Jesuati, preached poverty by precept and example, going back to the religious idea of St Francis of Assisi. His letters are among the most remarkable in the category of ascetic works in the 14th century.

Bianco da Siena wrote several religiously-inspired poems (lauda) that were popular in the Middle Ages.

Jacopo Passavanti, in his ''Specchio della vera penitenza'', attached instruction to narrative.

Domenico Cavalca translated from the Latin the ''Vite de' Santi Padri''. Rivalta left behind him many sermons, and

Franco Sacchetti (the famous novelist) many discourses. On the whole, there is no doubt that one of the most important productions of the Italian spirit of the 14th century was religious literature.

Popular works

Humorous poetry, largely developed in the 13th century, was carried on in the 14th by

Bindo Bonichi,

Arrigo di Castruccio,

Cecco Nuccoli,

Andrea Orcagna,

Lippo Pasci de' Bardi,

Adriano de Rossi,

Antonio Pucci and other lesser writers. Orcagna was especially comic; Bonichi was comic with a satirical and moral purpose. Pucci was superior to all of them for the variety of his production.

Political works

Many poets of the 14th century produced political works.

Fazio degli Uberti, the author of ''Dittamondo'', who wrote a ''Serventese'' to the lords and people of Italy, a poem on Rome, and a fierce invective against Charles IV, deserves notice, as do

Francesco di Vannozzo,

Frate Stoppa de' Bostichi and

Matteo Frescobaldi. It may be said in general that following the example of Petrarch many writers devoted themselves to patriotic poetry.

From this period also dates that literary phenomenon known under the name of Petrarchism. The Petrarchists, or those who sang of love, imitating Petrarch's manner, were found already in the 14th century. But others treated the same subject with more originality, in a manner that might be called semi-popular. Such were the ''Ballate'' of Ser

Giovanni Fiorentino, of Franco Sacchetti, of

Niccolò Soldanieri, and of

Guido

Guido is a given name. It has been a male first name in Italy, Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Argentina, the Low Countries, Scandinavia, Spain, Portugal and Latin America, as well as other places with migration from those. Regarding origins, there ...

and

Bindo Donati. ''Ballate'' were poems sung to dancing, and we have very many songs for the music of the 14th century. We have already stated that Antonio Pucci versified Villani's ''Chronicle''. It is enough to notice a chronicle of

Arezzo

Arezzo ( , ; ) is a city and ''comune'' in Italy and the capital of the Province of Arezzo, province of the same name located in Tuscany. Arezzo is about southeast of Florence at an elevation of Above mean sea level, above sea level. As of 2 ...

in ''

terza rima'' by

Bartolomeo Sinigardi, and the history, also in ''terza rima'', of the journey of Pope Alexander III to Venice, by

Pier de Natali. Besides this, every type of subject, whether history, tragedy or husbandry, was treated in verse.

Neri di Landocio wrote a life of St Catherine;

Jacopo Gradenigo called ''il Belletto'' put the Gospels into triplets.

15th century: Renaissance humanism

Renaissance humanism developed during the 14th and the beginning of the 15th centuries, and was a response to the challenge of Mediæval scholastic education, emphasizing practical, pre-professional and -scientific studies.

Scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and Ca ...

focused on preparing men to be doctors, lawyers or professional theologians, and was taught from approved textbooks in logic, natural philosophy, medicine, law and theology. The main centers of humanism were

Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

and

Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

.

Rather than train professionals in jargon and strict practice, humanists sought to create a citizenry (including, sometimes, women) able to speak and write with eloquence and clarity. This was to be accomplished through the study of the ''

studia humanitatis'', today known as the

humanities

Humanities are academic disciplines that study aspects of human society and culture, including Philosophy, certain fundamental questions asked by humans. During the Renaissance, the term "humanities" referred to the study of classical literature a ...

: grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry and moral philosophy. Early humanists, such as

Petrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

,

Coluccio Salutati

Coluccio Salutati (16 February 1331 – 4 May 1406) was an Italian Renaissance humanist and notary, and one of the most important political and cultural leaders of Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history ...

and

Leonardo Bruni, were great collectors of antique manuscripts.

In Italy, the humanist educational program won rapid acceptance and, by the mid-15th century, many of the upper classes had received humanist educations. There were five 15th century Humanist Popes, one of whom,

Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini (Pius II), was a prolific author and wrote a treatise on "The Education of Boys".

Literature in the Florence of the Medici

Leone Battista Alberti

Leone Battista Alberti, the learned Greek and Latin scholar, wrote in the vernacular, and

Vespasiano da Bisticci, while he was constantly absorbed in Greek and Latin manuscripts, wrote the ''Vite di uomini illustri'', valuable for their historical contents, and rivalling the best works of the 14th century in their candour and simplicity.

Andrea da Barberino wrote the beautiful prose of the ''Reali di Francia'', giving a coloring of ''romanità'' to the chivalrous romances.

Belcari and

Girolamo Benivieni returned to the mystic idealism of earlier times.

But it is in

Cosimo de' Medici and

Lorenzo de' Medici

Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici (), known as Lorenzo the Magnificent (; 1 January 1449 – 9 April 1492), was an Italian statesman, the ''de facto'' ruler of the Florentine Republic, and the most powerful patron of Renaissance culture in Italy. Lore ...

, from 1430 to 1492, that the influence of Florence on the Renaissance is particularly seen. Lorenzo de' Medici gave to his poetry the colors of the most pronounced realism as well as of the loftiest idealism, who passes from the Platonic

sonnet

A sonnet is a fixed poetic form with a structure traditionally consisting of fourteen lines adhering to a set Rhyme scheme, rhyming scheme. The term derives from the Italian word ''sonetto'' (, from the Latin word ''sonus'', ). Originating in ...

to the impassioned triplets of the ''Amori di Venere'', from the grandiosity of the ''Salve to Nencia'' and to Beoni, from the ''

Canto carnascialesco'' to the ''lauda''.

Next to Lorenzo comes

Poliziano, who also united, and with greater art, the ancient and the modern, the popular and the classical style. In his ''Rispetti'' and in his ''Ballate'' the freshness of imagery and the plasticity of form are inimitable. A great Greek scholar, Poliziano wrote Italian verses with dazzling colours; the purest elegance of the Greek sources pervaded his art in all its varieties, in the ''Orfeo'' as well as the ''Stanze per la giostra''.

A completely new style of poetry arose, the ''Canto carnascialesco''. These were a type of choral songs, which were accompanied by symbolic masquerades, common in Florence at the carnival. They were written in a metre like that of the ''ballate''; and for the most part, they were put into the mouth of a party of workmen and tradesmen, who, with not very chaste allusions, sang the praises of their art. These triumphs and masquerades were directed by Lorenzo himself. In the evening, there set out into the city large companies on horseback, playing and singing these songs. There are some by Lorenzo himself, which surpass all the others in their mastery of art. That entitled ''Bacco ed Arianna'' is the most famous.

Epic: Pulci and Boiardo

Italy did not yet have true

epic poetry

In poetry, an epic is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants. With regard t ...

, but had, however, many poems called ''

cantari'', because they contained stories that were sung to the people, and besides there were romantic poems, such as the ''

Buovo d'Antona'', the ''

Regina Ancroja'' and others. But the first to introduce life into this style was

Luigi Pulci, who wrote the ''

Morgante Maggiore''. The material of the ''Morgante'' is almost completely taken from an obscure chivalrous poem of the 15th century, rediscovered by

Pio Rajna. Pulci erected a structure of his own, often turning the subject into ridicule, burlesquing the characters, and introducing many digressions, now capricious, now scientific, now theological. Pulci raised the romantic epic into a work of art and united the serious and the comic.

With a more serious intention

Matteo Boiardo, count of

Scandiano, wrote his ''

Orlando innamorato

''Orlando Innamorato'' (; known in English language, English as "''Orlando in Love''"; in Italian language, Italian titled "''Orlando innamorato''" as the "I" is never capitalized) is an epic poem written by the Italian Renaissance author Matte ...

'', in which he seems to have aspired to embrace the whole range of

Carolingian legends; but he did not complete his task. A third romantic poem of the 15th century was the ''Mambriano'' by

Francesco Bello (Cieco of Ferrara). He drew from the

Carolingian cycle, from the romances of the

Round Table

The Round Table (; ; ; ) is King Arthur's famed table (furniture), table in the Arthurian legend, around which he and his knights congregate. As its name suggests, it has no head, implying that everyone who sits there has equal status, unlike co ...

, and from classical antiquity.

Other

Gioviano Pontano wrote the history of Naples,

Leonardo Bruni of Arezzo that of Florence, in Latin.

Bernardino Corio wrote the history of

Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

in Italian.

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 1452 - 2 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested o ...

wrote a treatise on painting,

Leone Battista Alberti one on sculpture and architecture.

Piero Capponi, author of the ''Commentari deli acquisto di Pisa'' and of the narration of the ''Tumulto dei Ciompi'', belonged to both the 14th and the 15th centuries.

Albertino Mussato of

Padua

Padua ( ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Veneto, northern Italy, and the capital of the province of Padua. The city lies on the banks of the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice and southeast of Vicenza, and has a population of 20 ...

wrote in Latin a history of

Emperor Henry VII. He then produced a Latin tragedy on

Ezzelino da Romano, Henry's imperial vicar in northern Italy, the ''Eccerinus'', which was probably not represented on the stage.

The development of drama in the 15th century was very great. This type of semi-popular literature was born in Florence, and attached itself to certain popular festivities that were usually held in honor of St

John the Baptist

John the Baptist ( – ) was a Jewish preacher active in the area of the Jordan River in the early first century AD. He is also known as Saint John the Forerunner in Eastern Orthodoxy and Oriental Orthodoxy, John the Immerser in some Baptist ...

, patron saint of the city. The ''

Sacra Rappresentazione'' is the development of the medieval ''Mistero'' (

mystery play). Although it belonged to popular poetry, some of its authors were literary men. From the 15th century, some element of the comic-profane found its way into the Sacra Rappresentazione. From its Biblical and legendary conventionalism Poliziano emancipated himself in his ''Orfeo'', which, although in its exterior form belonging to the sacred representations, yet substantially detaches itself from them in its contents and in the artistic element introduced.

16th century: the High Renaissance

The fundamental characteristic of the literary epoch following that of the Renaissance is that it perfected itself in every type of art, in particular uniting the essentially Italian character of its language with the classicism of style.

This period lasted from about 1494 to about 1560—1494 being when Charles VIII descended into Italy, marking the beginning of Italy's foreign domination and political decadence. Literary activity that appeared from the end of the 15th century to the middle of the 16th century was the product of the political and social conditions of an earlier age.

Baldassare Castiglione

Baldassare Castiglione wrote ''Il Cortegiano'' or ''

The Book of the Courtier

''The Book of the Courtier'' ( ) by Baldassare Castiglione is a lengthy philosophical dialogue on the topic of what constitutes an ideal courtier or (in the third chapter) court lady, worthy to befriend and advise a prince or political leader. ...

'', a

courtesy book A courtesy book (also book of manners) was a didactic manual of knowledge for courtiers to handle matters of etiquette, socially acceptable behaviour, and personal morals, with an especial emphasis upon life in a royal court; the genre of courtesy ...

dealing with questions of the etiquette and morality of the

courtier

A courtier () is a person who attends the royal court of a monarch or other royalty. The earliest historical examples of courtiers were part of the retinues of rulers. Historically the court was the centre of government as well as the officia ...

. Published in 1528, it was very influential in 16th century European court circles. ''The Book of the Courtier'' is a lengthy philosophical

dialogue

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog in American and British English spelling differences, American English) is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literature, literary and theatrical form that depicts suc ...

on the topic of what constitutes an ideal

courtier

A courtier () is a person who attends the royal court of a monarch or other royalty. The earliest historical examples of courtiers were part of the retinues of rulers. Historically the court was the centre of government as well as the officia ...

or (in the third chapter) court lady, worthy to befriend and advise a Prince or political leader. Inspired by the

Spanish court during his time as

Ambassador of the Holy See (1524–1529), Castiglione set the narrative of the book in his years as a courtier in his native

Duchy of Urbino

The Duchy of Urbino () was an independent duchy in Early modern period, early modern central Italy, corresponding to the northern half of the modern region of Marche. It was directly annexed by the Papal States in 1631.

It was bordered by the A ...

. The book quickly became enormously popular and was assimilated by its readers into the genre of prescriptive

courtesy book A courtesy book (also book of manners) was a didactic manual of knowledge for courtiers to handle matters of etiquette, socially acceptable behaviour, and personal morals, with an especial emphasis upon life in a royal court; the genre of courtesy ...

s or books of manners, dealing with issues of

etiquette

Etiquette ( /ˈɛtikɛt, -kɪt/) can be defined as a set of norms of personal behavior in polite society, usually occurring in the form of an ethical code of the expected and accepted social behaviors that accord with the conventions and ...

, self-presentation, and morals, particularly at

princely, or royal courts, books such as

Giovanni Della Casa's ''Galateo '' (1558) and

Stefano Guazzo's ''The civil conversation'' (1574). The ''Book of the Courtier'' was much more than that, however, having the character of a drama, an open-ended philosophical discussion, and an essay. It has also been seen as a veiled political

allegory

As a List of narrative techniques, literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a wikt:narrative, narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a meaning with moral or political signi ...

.

Science of history: Machiavelli and Guicciardini

Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli (3 May 1469 – 21 June 1527) was a Florentine diplomat, author, philosopher, and historian who lived during the Italian Renaissance. He is best known for his political treatise '' The Prince'' (), writte ...

and

Francesco Guicciardini were the chief originators of the science of history. Machiavelli's principal works are the ''Istorie fiorentine'', the ''Discorsi sulla prima deca di Tito Livio'', the ''Arte della guerra'' and the ''Principe''. His merit consists in having emphasized the experimental side of the study of political action by having observed facts, studied histories and drawn principles from them. His history is sometimes inexact in facts; it is rather a political than a historical work.

Guicciardini was very observant and endeavoured to reduce his observations to a science. His ''Storia d'Italia'', which extends from the death of

Lorenzo de' Medici

Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici (), known as Lorenzo the Magnificent (; 1 January 1449 – 9 April 1492), was an Italian statesman, the ''de facto'' ruler of the Florentine Republic, and the most powerful patron of Renaissance culture in Italy. Lore ...

to 1534, is full of political wisdom, is skillfully arranged in its parts, gives a lively picture of the character of the persons it treats of, and is written in a grand style. Machiavelli and Guicciardini may be considered distinguished historians as well as originators of the science of history founded on observation.

Inferior to them were

Jacopo Nardi (a just and faithful historian and a virtuous man, who defended the rights of Florence against the Medici before Charles V),

Benedetto Varchi,

Giambattista Adriani,

Bernardo Segni, and, outside Tuscany,

Camillo Porzio, who related the ''Congiura de baroni'' and the history of Italy from 1547 to 1552;

Angelo di Costanzo,

Pietro Bembo

Pietro Bembo, (; 20 May 1470 – 18 January 1547) was a Venetian scholar, poet, and literary theory, literary theorist who also was a member of the Knights Hospitaller and a cardinal of the Catholic Church. As an intellectual of the Italian Re ...

,

Paolo Paruta, and others.

Ludovico Ariosto

Ludovico Ariosto

Ludovico Ariosto's ''

Orlando furioso'' was a continuation of Boiardo's ''Innamorato''. His characteristic is that he assimilated the romance of chivalry into the style and models of classicism. Romantic Ariosto was an artist only for the love of his art; his epic.

Pietro Bembo

Pietro Bembo

Pietro Bembo, (; 20 May 1470 – 18 January 1547) was a Venetian scholar, poet, and literary theory, literary theorist who also was a member of the Knights Hospitaller and a cardinal of the Catholic Church. As an intellectual of the Italian Re ...

was an influential figure in the development of the

Italian language

Italian (, , or , ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European language family. It evolved from the colloquial Latin of the Roman Empire. Italian is the least divergent language from Latin, together with Sardinian language, Sardinian. It is ...

, specifically Tuscan, as a literary medium, and his writings assisted in the 16th century revival of interest in the works of

Petrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

. As a writer, Bembo attempted to restore some of the legendary "effect" that

ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

had on its hearers, but in Tuscan Italian instead. He held as his model and as the highest example of poetic expression ever achieved in Italian, the work of Petrarch and Boccaccio, two 14th century writers he assisted in bringing back into fashion.

In the ''Prose della volgar lingua'', he set Petrarch up as the perfect model and discussed

verse composition in detail.

Torquato Tasso

The historians of Italian literature are in doubt whether

Torquato Tasso

Torquato Tasso ( , also , ; 11 March 154425 April 1595) was an Italian poet of the 16th century, known for his 1591 poem ''Gerusalemme liberata'' (Jerusalem Delivered), in which he depicts a highly imaginative version of the combats between ...