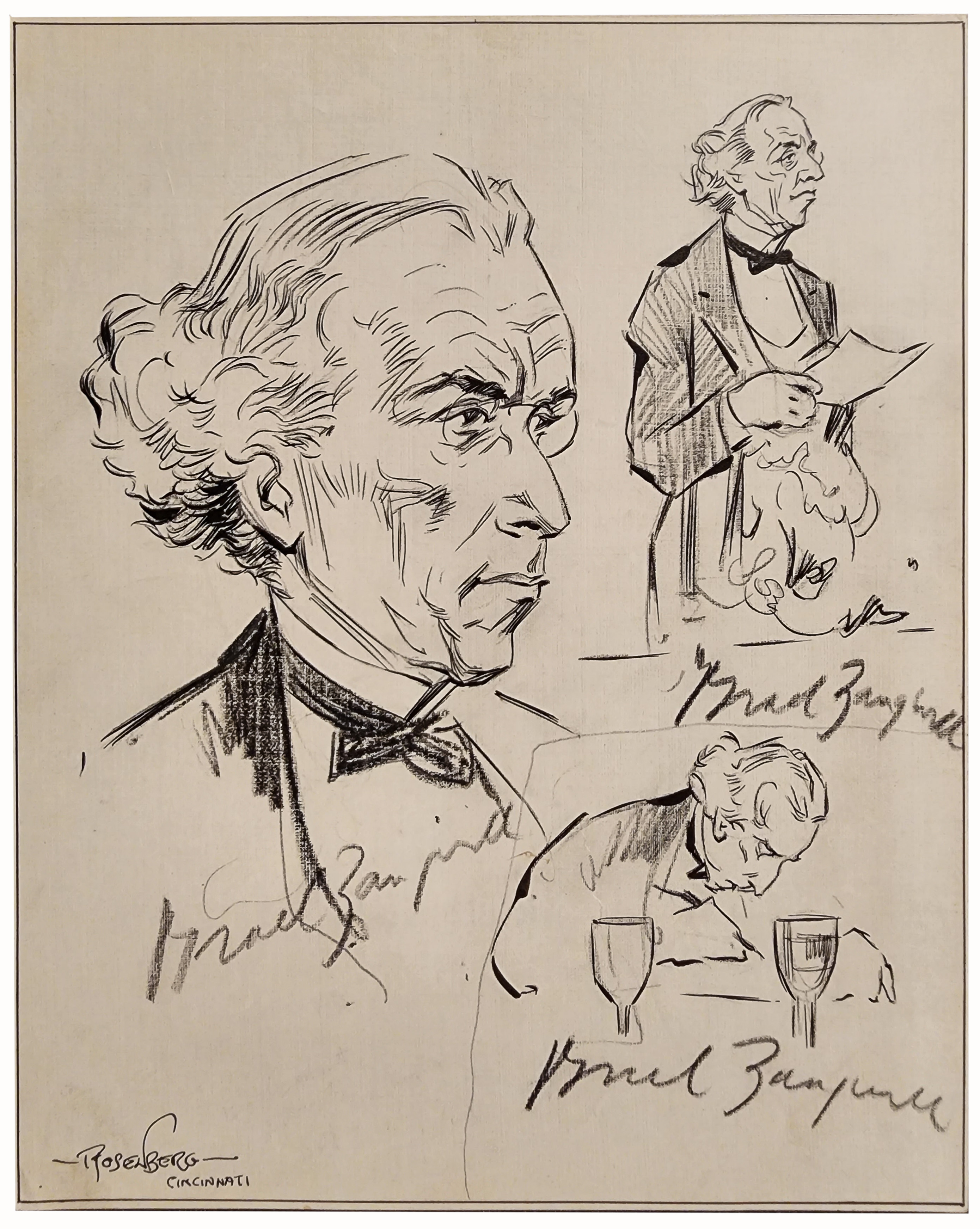

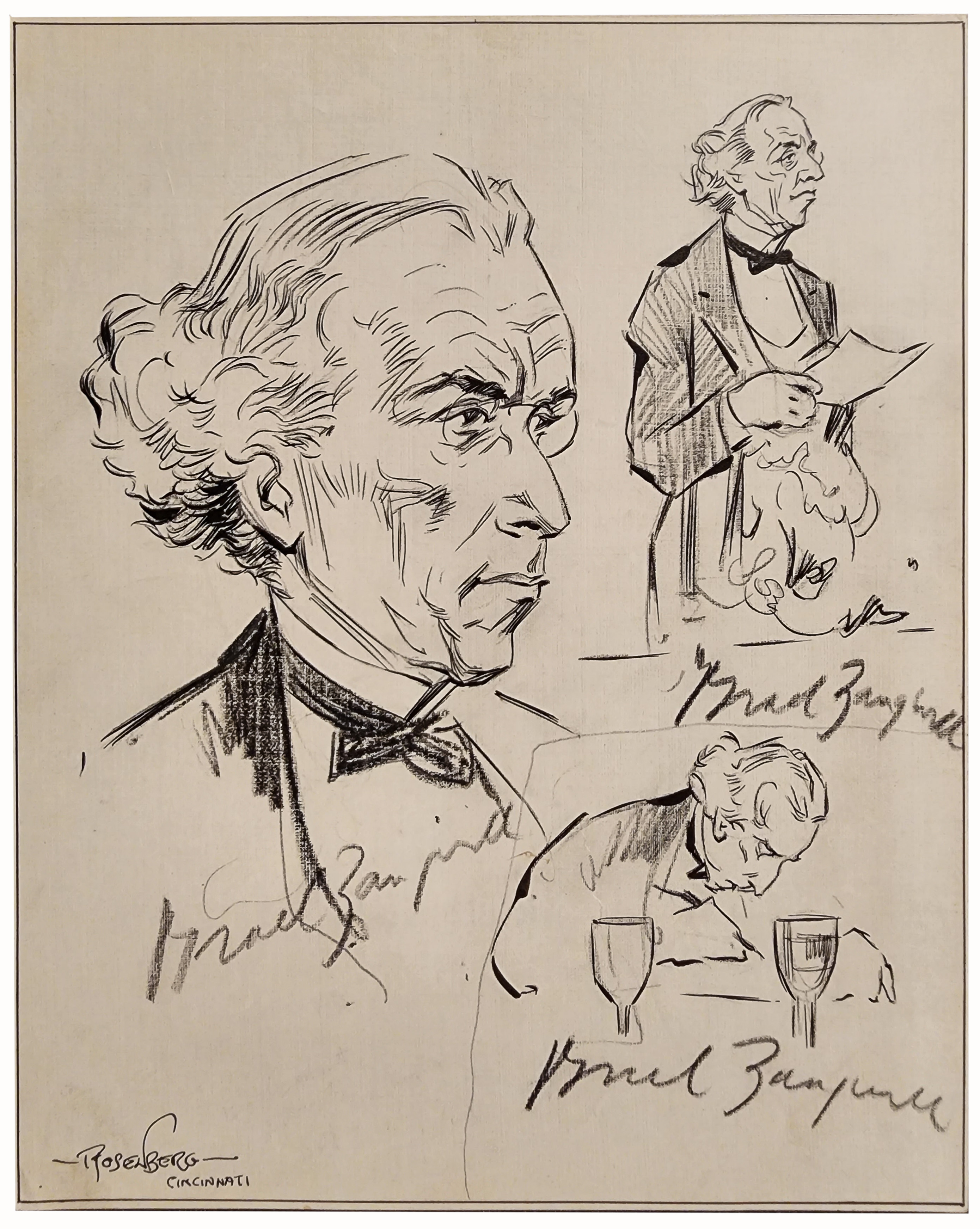

Israel Zangwill on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Israel Zangwill (21 January 18641 August 1926) was a British author at the forefront of

Zangwill's work earned him the nickname "the

Zangwill's work earned him the nickname "the  Another much produced play was ''The Lens Grinder'', based on the life of

Another much produced play was ''The Lens Grinder'', based on the life of

Zangwill endorsed feminism and pacifism, but his greatest effect may have been as a writer who popularised the idea of the combination of ethnicities into a single, American nation. The hero of his widely produced play '' The Melting Pot'' proclaims: "America is God's Crucible, the great Melting-Pot where all the races of Europe are melting and reforming...Germans and Frenchmen, Irishmen and Englishmen, Jews and Russians – into the Crucible with you all! God is making the American."

Zangwill endorsed feminism and pacifism, but his greatest effect may have been as a writer who popularised the idea of the combination of ethnicities into a single, American nation. The hero of his widely produced play '' The Melting Pot'' proclaims: "America is God's Crucible, the great Melting-Pot where all the races of Europe are melting and reforming...Germans and Frenchmen, Irishmen and Englishmen, Jews and Russians – into the Crucible with you all! God is making the American."

" An oft-cited Zionist slogan was neither Zionist nor popular,"

*''The Bachelors' Club'' (London : Henry, 1891)

*''The Old Maid’s Club'' (1892)

*'' The Big Bow Mystery'' (1892)

*''Merely Mary Ann'' (1893) (London: Raphael Tuck & Sons, illustrated by Mark Zangwill)

*'' The King of Schnorrers'' (1894)

*''The Master'' (1895) (based on the life of friend and illustrator George Wylie Hutchinson)

*''The Bachelors' Club'' (London : Henry, 1891)

*''The Old Maid’s Club'' (1892)

*'' The Big Bow Mystery'' (1892)

*''Merely Mary Ann'' (1893) (London: Raphael Tuck & Sons, illustrated by Mark Zangwill)

*'' The King of Schnorrers'' (1894)

*''The Master'' (1895) (based on the life of friend and illustrator George Wylie Hutchinson) Sandra Barry, "What's in a Name? The Gilbert Stuart Newton Plaque Error", Acadiensis, XXV, 1 (Autumn, 1995), p. 107

*

Without Prejudice

' (1896) *''The Grey Wig: Stories and Novelettes'' (1903) which include The Grey Wig; Chasse-Croise; The Woman Beater; The Eternal Feminine; The Silent Sisters; Merely Mary Ann *''Merely Mary Ann'' (1904) – Separate edition with photo illustrations from the stage production *''The Serio-Comic Governess'' (1904) *''Nurse Marjorie'' (1906) *'' The Melting Pot'' (1909) *''Italian Fantasies'' (1910) *''The Mantle of Elijah'' (London : Heinemann) *''The Principle of Nationalities'' (1917) *''Chosen Peoples'' (1919) As translator: *''Selected Religious Poems of Solomon ibn Gabirol''; pub. The Jewish Publication Society of America (1923) The "of the Ghetto" books: *''Children of the Ghetto: A Study of a Peculiar People'' (1892) *''Grandchildren of the Ghetto'' (1892) *''Dreamers of the Ghetto'' (1898) *''Ghetto Tragedies'', (1899) *''Ghetto Comedies'', (1907)

''Hands Off Russia: Speech by Mr. Israel Zangwill at the Albert Hall, February 8th, 1919.''

London: Workers' Socialist Federation, n.d. 919 * ''The Voice of Jerusalem.'' New York: Macmillan, 1921.

Central Zionist Archives

in Jerusalem. The notation of the record group is A120.

(1917)

Israel Zangwill and Children of the Ghetto

*

Jewish Museum in London

* *

Plays by Israel Zangwill written during World War 1 on Great War Theatre

{{DEFAULTSORT:Zangwill, Israel 1864 births 1926 deaths Writers from the London Borough of Tower Hamlets 19th-century English novelists Alumni of the University of London British Zionists English male novelists 19th-century English dramatists and playwrights Jewish English writers British people of Russian-Jewish descent Jewish novelists Jewish pacifists English male dramatists and playwrights People educated at JFS (school) Territorialism 19th-century English male writers 20th-century English novelists 20th-century English dramatists and playwrights 20th-century English male writers Ayrton family People from East Preston, West Sussex Delegates to the First World Zionist Congress Members of the Men's League for Women's Suffrage (United Kingdom) People from Whitechapel English male short story writers 19th-century English short story writers 20th-century English short story writers Victorian novelists Victorian short story writers 19th-century pseudonymous writers 20th-century pseudonymous writers English magazine editors 20th-century English translators

Zionism

Zionism is an Ethnic nationalism, ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in History of Europe#From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914), Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the ...

during the 19th century, and was a close associate of Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian Jewish journalist and lawyer who was the father of Types of Zionism, modern political Zionism. Herzl formed the World Zionist Organization, Zionist Organizat ...

. He later rejected the search for a Jewish homeland in Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

and became the prime thinker behind the territorial movement.

Early life and education

Zangwill was born inWhitechapel

Whitechapel () is an area in London, England, and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in east London and part of the East End of London, East End. It is the location of Tower Hamlets Town Hall and therefore the borough tow ...

, London on 21 January 1864, in a family of Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

immigrants from the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

. His father, Moses Zangwill, was from what is now Latvia

Latvia, officially the Republic of Latvia, is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is one of the three Baltic states, along with Estonia to the north and Lithuania to the south. It borders Russia to the east and Belarus to t ...

, and his mother, Ellen Hannah Marks Zangwill, was from what is now Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

. He dedicated his life to championing the cause of people he considered oppressed, becoming involved with topics such as Jewish emancipation, Jewish assimilation

Jewish assimilation (, ''hitbolelut'') refers either to the gradual cultural assimilation and social integration of Jews in their surrounding culture or to an ideological program in the age of emancipation promoting conformity as a potential so ...

, territorialism

Territorialism can refer to:

* Animal territorialism, the animal behavior of defending a geographical area from intruders

* Environmental territorialism, a stance toward threats posed toward individuals, communities or nations by environmental even ...

, Zionism

Zionism is an Ethnic nationalism, ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in History of Europe#From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914), Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the ...

, and women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

. His brother was novelist Louis Zangwill.

Zangwill received his early schooling in Plymouth and Bristol. When he was eight years old, his parents moved to Spitalfields, East London and he was enrolled in the Jews' Free School there, a school for Jewish immigrant children. The school offered a strict course of both secular and religious studies while supplying clothing, food, and health care for the scholars; presently one of its four houses is named Zangwill in his honour. At this school he excelled and even taught part-time, eventually becoming a full-fledged teacher.

While teaching, he studied for his degree from the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a collegiate university, federal Public university, public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The ...

, earning a BA with triple honours in 1884.

Career

Writings

Zangwill published some of his works under the pen-names J. Freeman Bell (for works written in collaboration), and Countess von S. and Marshallik. He had already written a tale entitled ''The Premier and the Painter'' in collaboration with Louis Cowen, when he resigned his position as a teacher at the Jews' Free School owing to differences with the school managers and ventured into journalism. He initiated and edited ''Ariel, The London Puck'', and did miscellaneous work for the London press. Zangwill's work earned him the nickname "the

Zangwill's work earned him the nickname "the Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by many as the great ...

of the Ghetto

A ghetto is a part of a city in which members of a minority group are concentrated, especially as a result of political, social, legal, religious, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished than other ...

". He wrote a very influential novel ''Children of the Ghetto: A Study of a Peculiar People'' (1892), which the late 19th-century English novelist George Gissing

George Robert Gissing ( ; 22 November 1857 – 28 December 1903) was an English novelist, who published 23 novels between 1880 and 1903. In the 1890s he was considered one of the three greatest novelists in England, and by the 1940s he had been ...

called "a powerful book".

The use of the metaphorical phrase "melting pot

A melting pot is a Monoculturalism, monocultural metaphor for a wiktionary:heterogeneous, heterogeneous society becoming more wiktionary:homogeneous, homogeneous, the different elements "melting together" with a common culture; an alternative bei ...

" to describe American absorption of immigrants was popularised by Zangwill's play '' The Melting Pot'', a success in the United States in 1909–10. The theatrical work explored the themes of ethnic tensions and the idea of cultural assimilation in early 20th-century America.

When ''The Melting Pot'' opened in Washington, D.C., on 5 October 1908, former President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

leaned over the edge of his box and shouted "That's a great play, Mr. Zangwill. That's a great play." In 1912, Zangwill received a letter from Roosevelt in which Roosevelt wrote of ''The Melting Pot'' "That particular play I shall always count among the very strong and real influences upon my thought and my life."

The protagonist of the play is David Quixano, a Russian Jewish immigrant who arrives in New York City after the Kishinev pogrom, in which his entire family is killed. He writes a great symphony named "The Crucible" expressing his hope for a world in which all ethnicity has melted away, and becomes enamored of a beautiful Russian Christian immigrant named Vera. The dramatic climax of the play is the moment when David meets Vera's father, who turns out to be the Russian officer responsible for the annihilation of David's family. Vera's father admits guilt, the symphony is performed to accolades, and David and Vera agree to wed and kiss as the curtain falls.

"''Melting Pot'' celebrated America's capacity to absorb and grow from the contributions of its immigrants." Zangwill was writing as "a Jew who no longer wanted to be a Jew. His real hope was for a world in which the entire lexicon of racial and religious difference is thrown away."

However, the play also addresses the challenges and conflicts that arise when different ethnic groups collide. It portrays the tensions between the Jewish and Christian communities, as well as the struggles of immigrants to find their place in a new society while preserving their cultural heritage.

"The Melting Pot" resonated with audiences during its time, as it captured the spirit of the American immigrant experience and explored issues of assimilation, identity, and the potential for a unified nation. The play contributed to the discourse on multiculturalism and the American identity, and it remains a significant work in the context of American theater and the portrayal of ethnic tensions on stage.

Zangwill wrote many other plays, including, on Broadway, '' Children of the Ghetto'' (1899), a dramatization of his own novel, directed by James A. Herne and starring Blanche Bates

Blanche Bates (August 25, 1873 – December 25, 1941) was an American actress.

Early years

Bates was born in Portland, Oregon, while her parents (both of whom were actors) were on a road tour. As an infant, she traveled with them on a tou ...

, Ada Dwyer, and Wilton Lackaye; '' Merely Mary Ann'' (1903) and ''Nurse Marjorie'' (1906), both of which were directed by Charles Cartwright and starred Eleanor Robson. Liebler & Co. produced all three plays as well as ''The Melting Pot''. Daniel Frohman produced Zangwill's 1904 play ''The Serio-Comic Governess'', featuring Cecilia Loftus, Kate Pattison-Selten, and Julia Dean. In 1931, Jules Furthman adapted '' Merely Mary Ann'' for a movie with Janet Gaynor.

Zangwill's simulation of Yiddish sentence structure in English aroused great interest. He also wrote mystery works, such as '' The Big Bow Mystery'' (1892), and social satire, such as '' The King of Schnorrers'' (1894), a picaresque novel

The picaresque novel ( Spanish: ''picaresca'', from ''pícaro'', for ' rogue' or 'rascal') is a genre of prose fiction. It depicts the adventures of a roguish but appealing hero, usually of low social class, who lives by his wits in a corrup ...

(which became a short-lived musical comedy in 1979). His ''Dreamers of the Ghetto'' (1898) includes essays on famous Jews such as Baruch Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (24 November 163221 February 1677), also known under his Latinized pen name Benedictus de Spinoza, was a philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, who was born in the Dutch Republic. A forerunner of the Age of Enlightenmen ...

, Heinrich Heine

Christian Johann Heinrich Heine (; ; born Harry Heine; 13 December 1797 – 17 February 1856) was an outstanding poet, writer, and literary criticism, literary critic of 19th-century German Romanticism. He is best known outside Germany for his ...

and Ferdinand Lassalle.

''The Big Bow Mystery'' was one of the first locked room mystery novels. It has been almost continuously in print since 1891 and has been used as the basis for three movies.

Another much produced play was ''The Lens Grinder'', based on the life of

Another much produced play was ''The Lens Grinder'', based on the life of Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (24 November 163221 February 1677), also known under his Latinized pen name Benedictus de Spinoza, was a philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, who was born in the Dutch Republic. A forerunner of the Age of Enlightenmen ...

.

Politics

Zangwill endorsed feminism and pacifism, but his greatest effect may have been as a writer who popularised the idea of the combination of ethnicities into a single, American nation. The hero of his widely produced play '' The Melting Pot'' proclaims: "America is God's Crucible, the great Melting-Pot where all the races of Europe are melting and reforming...Germans and Frenchmen, Irishmen and Englishmen, Jews and Russians – into the Crucible with you all! God is making the American."

Zangwill endorsed feminism and pacifism, but his greatest effect may have been as a writer who popularised the idea of the combination of ethnicities into a single, American nation. The hero of his widely produced play '' The Melting Pot'' proclaims: "America is God's Crucible, the great Melting-Pot where all the races of Europe are melting and reforming...Germans and Frenchmen, Irishmen and Englishmen, Jews and Russians – into the Crucible with you all! God is making the American."

Jewish politics

Zangwill was also involved with specifically Jewish issues as an assimilationist, an early Zionist, and a territorialist. Jewish territorialism was a political movement that emerged as a response to the rise of anti-Semitism in Europe during the early 20th century. It proposed the establishment of a Jewish homeland outside of Palestine, offering alternative solutions to the ongoing debate about Jewish self-determination and Zionism. After having for a time endorsedTheodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian Jewish journalist and lawyer who was the father of Types of Zionism, modern political Zionism. Herzl formed the World Zionist Organization, Zionist Organizat ...

, including presiding over a meeting at the Maccabean Club, London, addressed by Herzl on 24 November 1895, and endorsing the main Palestine-oriented Zionist movement. Zangwill changed his mind and founded his own organization, named the Jewish Territorialist Organization

The Jewish Territorial Organisation, known as the ITO, was a Jewish political movement which first arose in 1903 in response to the British Uganda Scheme, but only institutionalized in 1905. Its main goal was to find an alternative territory to ...

in 1905, advocating a Jewish homeland in whatever land might be available in the world which could be found for them, with speculations including Canada, Australia, Mesopotamia, Uganda and Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika (, , after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between the 16th and 25th meridians east, including the Kufra District. The coastal region, als ...

.

Zangwill is inaccurately known for creating the slogan "A land without a people for a people without a land

"A land without a people for a people without a land" is a widely cited phrase associated with the movement to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine (region), Palestine. Its historicity and significance are a matter of contention.

Although ...

" describing Zionist aspirations in the Biblical land of Israel. He did not invent the phrase; he acknowledged borrowing it from Lord Shaftesbury.Garfinkle, Adam M., "On the Origin, Meaning, Use and Abuse of a Phrase." ''Middle Eastern Studies'', London, October 1991, vol. 27 In 1853, during the preparation for the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

, Shaftesbury wrote to Foreign Secretary Aberdeen that Greater Syria was "a country without a nation" in need of "a nation without a country.... Is there such a thing? To be sure there is, the ancient and rightful lords of the soil, the Jews!" In his diary that year he wrote "these vast and fertile regions will soon be without a ruler, without a known and acknowledged power to claim dominion. The territory must be assigned to some one or other.... There is a country without a nation; and God now in his wisdom and mercy, directs us to a nation without a country." Shaftesbury himself was echoing the sentiments of Alexander Keith, D.D.A Land without a People for a People without a Land" An oft-cited Zionist slogan was neither Zionist nor popular,"

Diana Muir

Diana Muir, also known as Diana Muir Appelbaum, is an American historian from Newton, Massachusetts, best known for her 2000 book, ''Reflections in Bullough's Pond'', a history of the impact of human activity on the New England ecosystem.

Perso ...

, Middle Eastern Quarterly, Spring 2008, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 55–62.

In 1901, in the ''New Liberal Review

The ''New Liberal Review'' was a short-lived British, monthly periodical published from 1901 to 1904 in London. The ''New Liberal Review'' was founded by brothers Cecil and Hildebrand Harmsworth. Their stated goals were "to reflect the best Libe ...

'', Zangwill wrote that "Palestine is a country without a people; the Jews are a people without a country".

Theodor Herzl got along well with Israel Zangwill and Max Nordau. They were both writers or 'men of letters'. In November 1901 Zangwill was still misreading the situation: "Palestine has but a small population of Arabs and fellahin

A fellah ( ; feminine ; plural ''fellaheen'' or ''fellahin'', , ) is a local peasant, usually a farmer or agricultural laborer in the Middle East and North Africa. The word derives from the Arabic word for "ploughman" or "tiller".

Due to a con ...

and wandering, lawless, blackmailing Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu ( ; , singular ) are pastorally nomadic Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia (Iraq). The Bedouin originated in the Sy ...

tribes."Israel Zangwill, The Commercial Future of Palestine, Debate at the Article Club, 20 November 1901. Published by Greenberg & Co. Also published in ''English Illustrated Magazine'', Vol. 221 (Feb 1902) pp. 421–430. To conclude his opening address to the Article Club, Zangwill pretended to speak as the weary, Ashkenazic folktale character, the Wandering Jew, saying, "restore the country without a people to the people without a country... For we have something to give as well as to get. We can sweep away the blackmailerbe he Pasha or Bedouinwe can make the wilderness blossom as the rose, and build up in the heart of the world a civilization that may be a mediator and interpreter between the East and the West."

In 1902, Zangwill wrote that Palestine "remains at this moment an almost uninhabited, forsaken and ruined Turkish territory". However, within a few years, Zangwill had "become fully aware of the Arab peril", telling an audience in New York, "Palestine proper has already its inhabitants. The pashalik of Jerusalem is already twice as thickly populated as the United States" leaving Zionists the choice of driving the Arabs out or dealing with a "large alien population". He moved his support to the Uganda scheme, leading to a break with the mainstream Zionist movement by 1905. In 1908, Zangwill told a London court that he had been naive when he made his 1901 speech and had since "realized what is the density of the Arab population", namely twice that of the United States. In 1913 he criticized those who insisted on repeating that Palestine was "empty and derelict" and who called him a traitor for reporting otherwise.

According to Ze'ev Jabotinsky

Ze'ev Jabotinsky (born Vladimir Yevgenyevich Zhabotinsky; 17 October 1880 – 3 August 1940) was a Russian-born author, poet, orator, soldier, and founder of the Revisionist Zionist movement and the Jewish Self-Defense Organization in O ...

, Zangwill told him in 1916 that, "If you wish to give a country to a people without a country, it is utter foolishness to allow it to be the country of two peoples. This can only cause trouble. The Jews will suffer and so will their neighbours. One of the two: a different place must be found either for the Jews or for their neighbours".

In 1917, he wrote "'Give the country without a people,' magnanimously pleaded Lord Shaftesbury, 'to the people without a country.' Alas, it was a misleading mistake. The country holds 600,000 Arabs."In 1921, Zangwill suggested Lord Shaftesbury "was literally inexact in describing Palestine as a country without a people, he was essentially correct, for there is no Arab people living in intimate fusion with the country, utilizing its resources and stamping it with a characteristic impress: there is at best an Arab encampment, the break-up of which would throw upon the Jews the actual manual labor of regeneration and prevent them from exploiting the ''fellah

A fellah ( ; feminine ; plural ''fellaheen'' or ''fellahin'', , ) is a local peasant, usually a farmer or agricultural laborer in the Middle East and North Africa. The word derives from the Arabic word for "ploughman" or "tiller".

Due to a con ...

in'', whose numbers and lower wages are moreover a considerable obstacle to the proposed immigration from Poland and other suffering centers".

Views

In his writings, Zangwill expressed mixed sentiments about the then-territory of Palestine, parts of which became the modern State ofIsrael

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

in 1948, two decades after his death. After the establishment of the state, Philip Rubin speculated that the new state might have met his aspirations.

He was an early suffragist.

During World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, he advocated the formation of a Jewish foreign legion to the central powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

.

"The League of Damnations" is a term associated with Zangwill's critique of the anti-Semitic sentiment prevalent in Europe during his time. He used this phrase to describe the collective hostility and discrimination faced by Jewish people in various countries. Zangwill was an ardent opponent of anti-Semitism and used his writings to expose and challenge the prejudices and injustices faced by Jews.

Personal life

Zangwill married Edith Ayrton in 1903. She was a feminist and author, and the daughter of cousinsWilliam Edward Ayrton

William Edward Ayrton, FRS (14 September 18478 November 1908) was an English physicist and electrical engineer.

Life

Early life and education

Ayrton was born in London, the son of Edward Nugent Ayrton, a barrister, and educated at University ...

and Matilda Chaplin Ayrton. Ayrton's stepmother was Hertha Ayrton, who, like Zangwill, was Jewish.

The Zangwill family lived for many years in East Preston, West Sussex in a house named Far End. The couple had three children, two sons and a daughter. The younger of their two sons was the British psychologist Oliver Zangwill.

Zangwill died of pneumonia on 1 August 1926 at a nursing home in Midhurst, West Sussex. He had spent two months at the nursing home.

Other works

*''The Bachelors' Club'' (London : Henry, 1891)

*''The Old Maid’s Club'' (1892)

*'' The Big Bow Mystery'' (1892)

*''Merely Mary Ann'' (1893) (London: Raphael Tuck & Sons, illustrated by Mark Zangwill)

*'' The King of Schnorrers'' (1894)

*''The Master'' (1895) (based on the life of friend and illustrator George Wylie Hutchinson)

*''The Bachelors' Club'' (London : Henry, 1891)

*''The Old Maid’s Club'' (1892)

*'' The Big Bow Mystery'' (1892)

*''Merely Mary Ann'' (1893) (London: Raphael Tuck & Sons, illustrated by Mark Zangwill)

*'' The King of Schnorrers'' (1894)

*''The Master'' (1895) (based on the life of friend and illustrator George Wylie Hutchinson)*

Without Prejudice

' (1896) *''The Grey Wig: Stories and Novelettes'' (1903) which include The Grey Wig; Chasse-Croise; The Woman Beater; The Eternal Feminine; The Silent Sisters; Merely Mary Ann *''Merely Mary Ann'' (1904) – Separate edition with photo illustrations from the stage production *''The Serio-Comic Governess'' (1904) *''Nurse Marjorie'' (1906) *'' The Melting Pot'' (1909) *''Italian Fantasies'' (1910) *''The Mantle of Elijah'' (London : Heinemann) *''The Principle of Nationalities'' (1917) *''Chosen Peoples'' (1919) As translator: *''Selected Religious Poems of Solomon ibn Gabirol''; pub. The Jewish Publication Society of America (1923) The "of the Ghetto" books: *''Children of the Ghetto: A Study of a Peculiar People'' (1892) *''Grandchildren of the Ghetto'' (1892) *''Dreamers of the Ghetto'' (1898) *''Ghetto Tragedies'', (1899) *''Ghetto Comedies'', (1907)

Filmography

*'' Children of the Ghetto'', directed byFrank Powell

Francis William Powell (May 8, 1877 – ?) was a Canadian-born American stage and silent film actor, director, Film producer, producer, and screenwriter who worked predominantly in the United States."Ontario Births, 1869-1912", digital copy of ...

(1915, based on the play ''Children of the Ghetto'')

*'' The Melting Pot'', directed by Oliver D. Bailey and James Vincent (1915, based on the play ''The Melting Pot'')

*'' Merely Mary Ann'', directed by John G. Adolfi (1916, based on the play ''Merely Mary Ann'')

*'' The Moment Before'', directed by Robert G. Vignola

Robert G. Vignola (born Rocco Giuseppe Vignola, August 7, 1882 – October 25, 1953) was an Italian-American actor, screenwriter, and film director. A former stage actor, he appeared in many motion pictures produced by Kalem Company and later mov ...

(1916, based on the play ''The Moment of Death'')

*'' Mary Ann'', directed by Alexander Korda

Sir Alexander Korda (; born Sándor László Kellner; ; 16 September 1893 – 23 January 1956)

(Hungary, 1918, based on the play ''Merely Mary Ann'')

*'' Nurse Marjorie'', directed by William Desmond Taylor

William Desmond Taylor (born William Cunningham Deane-Tanner; 26 April 1872 – 1 February 1922) was an Anglo-Irish-American film director and actor. A popular figure in the growing Cinema of the United States, Hollywood motion picture colony o ...

(1920, based on the play ''Nurse Marjorie'')

*'' Merely Mary Ann'', directed by Edward LeSaint

Edward LeSaint (January 1, 1871 – September 10, 1940) was an American stage and film actor and Film director, director whose career began in the silent film, silent era. He acted in over 300 films and directed more than 90. He was sometimes ...

(1920, based on the play ''Merely Mary Ann'')

*'' The Bachelor's Club'', directed by A. V. Bramble

Albert Victor Bramble (1884–1963) was an English film actor, actor and film director. He began his acting career on the stage. He started acting in films in 1914 and subsequently turned to directing and producing films. He died on 17 May 196 ...

(1921, based on the novel ''We Moderns'')

*'' We Moderns'', directed by John Francis Dillon (1925, based on the play ''We Moderns'')

*'' Too Much Money'', directed by John Francis Dillon (1926, based on the play ''Too Much Money'')

*', directed by Bert Glennon

Bert Lawrence Glennon (November 19, 1895 – June 29, 1967) was an American cinematographer and film director. He directed ''Syncopation (1929 film), Syncopation'' (1929), the first film released by RKO Radio Pictures.

Biography

Glennon ...

(1928, based on the novel ''The Big Bow Mystery'')

*'' Merely Mary Ann'', directed by Henry King (1931, based on the play ''Merely Mary Ann'')

*'' The Crime Doctor'', directed by John S. Robertson (1934, based on the novel ''The Big Bow Mystery'')

*''The Verdict

''The Verdict'' is a 1982 American legal drama film directed by Sidney Lumet and written by David Mamet, adapted from Barry Reed's 1980 novel of the same name. The film stars Paul Newman as a down-on-his-luck alcoholic lawyer in Boston who acc ...

'', directed by Don Siegel

Donald Siegel ( ; October 26, 1912 – April 20, 1991) was an American film director and producer.

Siegel was described by ''The New York Times'' as "a director of tough, cynical and forthright action-adventure films whose taut plots centered o ...

(1946, based on the novel ''The Big Bow Mystery'')

Bibliography

References

Own writing

* "The Return to Palestine", New Liberal Review, Dec. 1901 * * "Providence, Palestine and the Rothschilds", ''The Speaker,'' vol. 4, no. 125 (22 February 1902). *''The War For The World.'' New York: Macmillan, 1916.''Hands Off Russia: Speech by Mr. Israel Zangwill at the Albert Hall, February 8th, 1919.''

London: Workers' Socialist Federation, n.d. 919 * ''The Voice of Jerusalem.'' New York: Macmillan, 1921.

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * *External links

* * * * * * * The personal papers of Israel Zangwill are kept at thCentral Zionist Archives

in Jerusalem. The notation of the record group is A120.

(1917)

Israel Zangwill and Children of the Ghetto

*

Jewish Museum in London

* *

Plays by Israel Zangwill written during World War 1 on Great War Theatre

{{DEFAULTSORT:Zangwill, Israel 1864 births 1926 deaths Writers from the London Borough of Tower Hamlets 19th-century English novelists Alumni of the University of London British Zionists English male novelists 19th-century English dramatists and playwrights Jewish English writers British people of Russian-Jewish descent Jewish novelists Jewish pacifists English male dramatists and playwrights People educated at JFS (school) Territorialism 19th-century English male writers 20th-century English novelists 20th-century English dramatists and playwrights 20th-century English male writers Ayrton family People from East Preston, West Sussex Delegates to the First World Zionist Congress Members of the Men's League for Women's Suffrage (United Kingdom) People from Whitechapel English male short story writers 19th-century English short story writers 20th-century English short story writers Victorian novelists Victorian short story writers 19th-century pseudonymous writers 20th-century pseudonymous writers English magazine editors 20th-century English translators