Islamic Contributions To Medieval Europe on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

During the

During the

Europe and the Islamic lands had multiple points of contact during the Middle Ages. The main points of transmission of Islamic knowledge to Europe lay in

Europe and the Islamic lands had multiple points of contact during the Middle Ages. The main points of transmission of Islamic knowledge to Europe lay in

Contributing to the growth of European science was the major search by European scholars such as Gerard of Cremona for new learning. These scholars were interested in ancient Greek philosophical and scientific texts (notably the ''

Contributing to the growth of European science was the major search by European scholars such as Gerard of Cremona for new learning. These scholars were interested in ancient Greek philosophical and scientific texts (notably the ''

The Miracle of Light

, ''A World of Science'' 3 (3),

Best Idea; Eyes Wide Open

, ''

One of the most important medical works to be translated was

One of the most important medical works to be translated was

Science museum on Albucasis Other medical Arabic works translated into Latin during the medieval period include the works of Razi and Avicenna (including ''The Book of Healing'' and ''The Canon of Medicine''), and

The

The

Some scholars believe that the

Some scholars believe that the

A number of technologies in the Islamic world were adopted in European medieval technology. These included various

A number of technologies in the Islamic world were adopted in European medieval technology. These included various

Transfer Of Islamic Technology To The West, Part II: Transmission Of Islamic Engineering

, ''History of Science and Technology in Islam'' In an influential 1974 paper, historian Andrew Watson suggested that there had been an

In an influential 1974 paper, historian Andrew Watson suggested that there had been an

While the Coin#History, earliest coins were minted and widely circulated in Europe, and Ancient Rome, Islamic coinage had some influence on medieval European minting. The 8th-century English king Offa of Mercia minted a near-copy of Abbasid Caliphate, Abbasid dinars struck in 774 by Caliph Al-Mansur with "Offa Rex" centered on the reverse. The moneyer visibly had little understanding of Arabic, as the Arabic text contains a number of errors.

While the Coin#History, earliest coins were minted and widely circulated in Europe, and Ancient Rome, Islamic coinage had some influence on medieval European minting. The 8th-century English king Offa of Mercia minted a near-copy of Abbasid Caliphate, Abbasid dinars struck in 774 by Caliph Al-Mansur with "Offa Rex" centered on the reverse. The moneyer visibly had little understanding of Arabic, as the Arabic text contains a number of errors.

In

In

google books

* * Matthew, Donald, ''The Norman kingdom of Sicily'' Cambridge University Press, 1992 * * * *

Islamic Contributions to the West

by Rachida El Diwani, Professor of Comparative Literature.

by De Lacy O'Leary

Islamic Contributions to Civilization

by Stanwood Cobb (1963) {{DEFAULTSORT:Islamic Contributions To Medieval Europe Islamic Golden Age High Middle Ages Medieval Islamic world History of al-Andalus Western culture Cultural exchange Christianity and Islam Multiculturalism and Islam Multiculturalism and Christianity

High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history between and ; it was preceded by the Early Middle Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended according to historiographical convention ...

, the Islamic world

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is ...

was an important contributor to the global cultural scene, innovating and supplying information and ideas to Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, via Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

, Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

and the Crusader kingdoms in the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

. These included Latin translations of the Greek Classics and of Arabic texts in astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

, and medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

. Translation of Arabic philosophical texts into Latin "led to the transformation of almost all philosophical disciplines in the medieval Latin world", with a particularly strong influence of Muslim philosophers being felt in natural philosophy, psychology and metaphysics. Other contributions included technological and scientific innovations via the Silk Road

The Silk Road was a network of Asian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over , it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and religious interactions between the ...

, including Chinese inventions

History of Science and Technology in China, China has been the source of many innovations, scientific discovery (observation), discoveries and inventions. This includes the ''Four Great Inventions'': papermaking, the compass, gunpowder, and Hist ...

such as paper

Paper is a thin sheet material produced by mechanically or chemically processing cellulose fibres derived from wood, Textile, rags, poaceae, grasses, Feces#Other uses, herbivore dung, or other vegetable sources in water. Once the water is dra ...

, compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with No ...

and gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

.

The Islamic world also influenced other aspects of medieval European culture, partly by original innovations made during the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of scientific, economic, and cultural flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 13th century.

This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign o ...

, including various fields such as the arts

The arts or creative arts are a vast range of human practices involving creativity, creative expression, storytelling, and cultural participation. The arts encompass diverse and plural modes of thought, deeds, and existence in an extensive ...

, agriculture

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created ...

, alchemy

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

, music

Music is the arrangement of sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm, or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Music is generally agreed to be a cultural universal that is present in all hum ...

, pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other raw materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. The place where such wares are made by a ''potter'' is al ...

, etc.

Many Arabic loanwords in Western European languages, including English, mostly via Old French, date from this period. This includes traditional star names such as Aldebaran

Aldebaran () is a star in the zodiac constellation of Taurus. It has the Bayer designation α Tauri, which is Latinized to Alpha Tauri and abbreviated Alpha Tau or α Tau. Aldebaran varies in brightness from an apparent vis ...

, scientific terms like ''alchemy

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

'' (whence also ''chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

''), ''algebra

Algebra is a branch of mathematics that deals with abstract systems, known as algebraic structures, and the manipulation of expressions within those systems. It is a generalization of arithmetic that introduces variables and algebraic ope ...

'', ''algorithm

In mathematics and computer science, an algorithm () is a finite sequence of Rigour#Mathematics, mathematically rigorous instructions, typically used to solve a class of specific Computational problem, problems or to perform a computation. Algo ...

'', etc. and names of commodities such as ''sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecul ...

'', ''camphor

Camphor () is a waxy, colorless solid with a strong aroma. It is classified as a terpenoid and a cyclic ketone. It is found in the wood of the camphor laurel (''Cinnamomum camphora''), a large evergreen tree found in East Asia; and in the kapu ...

'', ''cotton

Cotton (), first recorded in ancient India, is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure ...

'', ''coffee

Coffee is a beverage brewed from roasted, ground coffee beans. Darkly colored, bitter, and slightly acidic, coffee has a stimulating effect on humans, primarily due to its caffeine content, but decaffeinated coffee is also commercially a ...

'', etc.

Transmission routes

Europe and the Islamic lands had multiple points of contact during the Middle Ages. The main points of transmission of Islamic knowledge to Europe lay in

Europe and the Islamic lands had multiple points of contact during the Middle Ages. The main points of transmission of Islamic knowledge to Europe lay in Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

and in Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, particularly in Toledo (with Gerard of Cremone, 1114–1187, following the conquest of the city by Spanish Christians in 1085). In Sicily, following the Islamic conquest of the island in 965 and its reconquest by the Normans in 1091, a syncretistic Norman–Arab–Byzantine culture developed, exemplified by rulers such as King Roger II

Roger II or Roger the Great (, , Greek: Ρογέριος; 22 December 1095 – 26 February 1154) was King of Sicily and Africa, son of Roger I of Sicily and successor to his brother Simon. He began his rule as Count of Sicily in 1105, became ...

, who had Islamic soldiers, poets and scientists at his court. The Moroccan Muhammad al-Idrisi

Abu Abdullah Muhammad al-Idrisi al-Qurtubi al-Hasani as-Sabti, or simply al-Idrisi (; ; 1100–1165), was an Arab Muslim geographer and cartographer who served in the court of King Roger II at Palermo, Sicily. Muhammad al-Idrisi was born in C ...

wrote ''The Book of Pleasant Journeys into Faraway Lands'' or '' Tabula Rogeriana'', one of the greatest geographical treatises of the Middle Ages, for Roger.

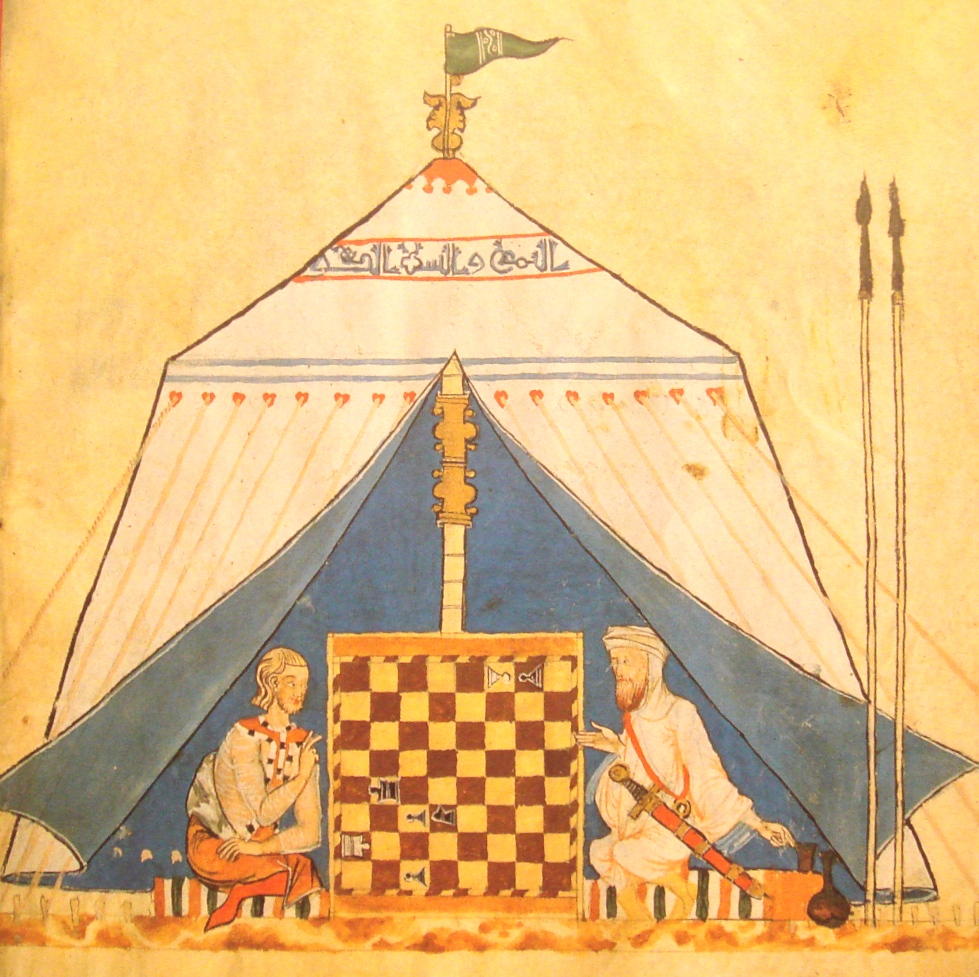

The Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

also intensified exchanges between Europe and the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

, with the Italian maritime republics taking a major role in these exchanges. In the Levant, in such cities as Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; , ) "Antioch on Daphne"; or "Antioch the Great"; ; ; ; ; ; ; . was a Hellenistic Greek city founded by Seleucus I Nicator in 300 BC. One of the most important Greek cities of the Hellenistic period, it served as ...

, Arab and Latin cultures intermixed intensively.

During the 11th and 12th centuries, many Christian scholars traveled to Muslim lands to learn sciences. Notable examples include Leonardo Fibonacci (c. 1170 –c. 1250), Adelard of Bath

Adelard of Bath (; 1080? 1142–1152?) was a 12th-century English natural philosopher. He is known both for his original works and for translating many important Greek scientific works of astrology, astronomy, philosophy, alchemy and mathemat ...

(c. 1080–c. 1152) and Constantine the African (1017–1087). From the 11th to the 14th centuries, numerous European students attended Muslim centers of higher learning (which the author calls "universities") to study medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

, philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, cosmography and other subjects.

Aristotelianism and other philosophies

In theMiddle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

, many classical Greek texts, especially the works of Aristotle, were translated into Syriac during the 6th and 7th centuries by Nestorian

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

, Melkite

The term Melkite (), also written Melchite, refers to various Eastern Christian churches of the Byzantine Rite and their members originating in West Asia. The term comes from the common Central Semitic root ''m-l-k'', meaning "royal", referrin ...

or Jacobite monks living in Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

, or by Greek exiles from Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

or Edessa

Edessa (; ) was an ancient city (''polis'') in Upper Mesopotamia, in what is now Urfa or Şanlıurfa, Turkey. It was founded during the Hellenistic period by Macedonian general and self proclaimed king Seleucus I Nicator (), founder of the Sel ...

who visited Islamic centres of higher learning. The Islamic world then kept, translated, and developed many of these texts, especially in centers of learning such as Baghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

, where a "House of Wisdom

The House of Wisdom ( ), also known as the Grand Library of Baghdad, was believed to be a major Abbasid Caliphate, Abbasid-era public academy and intellectual center in Baghdad. In popular reference, it acted as one of the world's largest publ ...

" with thousands of manuscripts existed as early as 832. These texts were in turn translated into Latin by scholars such as Michael Scot

Michael Scot (Latin: Michael Scotus; 1175 – ) was a Scottish mathematician and scholar in the Middle Ages. He was educated at University of Oxford, Oxford and University of Paris, Paris, and worked in Bologna and Toledo, Spain, Toledo, where ...

(who made translations of '' Historia Animalium'' and ''On the Soul

''On the Soul'' ( Greek: , ''Peri Psychēs''; Latin: ) is a major treatise written by Aristotle . His discussion centres on the kinds of souls possessed by different kinds of living things, distinguished by their different operations. Thus pla ...

'' as well as of Averroes's commentaries) during the Middle Ages. Eastern Christians played an important role in exploiting this knowledge, especially through the Christian Aristotelian School of Baghdad in the 11th and 12th centuries.

Later Latin translations of these texts originated in multiple places. Toledo, Spain (with Gerard of Cremona

Gerard of Cremona (Latin: ''Gerardus Cremonensis''; c. 1114 – 1187) was an Italians, Italian translator of scientific books from Arabic into Latin. He worked in Toledo, Spain, Toledo, Kingdom of Castile and obtained the Arabic books in the libr ...

's ''Almagest

The ''Almagest'' ( ) is a 2nd-century Greek mathematics, mathematical and Greek astronomy, astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Ptolemy, Claudius Ptolemy ( ) in Koine Greek. One of the most i ...

'') and Sicily became the main points of transmission of knowledge from the Islamic world to Europe. Burgundio of Pisa (died 1193) discovered lost texts of Aristotle in Antioch and translated them into Latin.

From Islamic Spain, the Arabic philosophical literature was translated into Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

, Latin, and Ladino. The Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides

Moses ben Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (, ) and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam (), was a Sephardic rabbi and philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah scholars of the Middle A ...

, Muslim sociologist-historian Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732–808 Hijri year, AH) was an Arabs, Arab Islamic scholar, historian, philosopher and sociologist. He is widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest social scientists of the Middle Ages, and cons ...

, Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

citizen Constantine the African who translated Greek medical texts, and Al-Khwarizmi's collation of mathematical techniques were important figures of the Golden Age.

Avicennism

Avicennism is a school of Islamic philosophy which was established by Avicenna. He developed his philosophy throughout the course of his life after being deeply moved and concerned by the ''Metaphysics'' of Aristotle and studying it for over a yea ...

and Averroism

Averroism, also known as Rushdism, was a school of medieval philosophy based on the application of the works of 12th-century Andalusian philosopher Averroes, (Ibn Rushd in Arabic; 1126–1198) a commentator on Aristotle, in 13th-century Latin C ...

are terms for the revival of the Peripatetic school

The Peripatetic school ( ) was a philosophical school founded in 335 BC by Aristotle in the Lyceum in ancient Athens. It was an informal institution whose members conducted philosophical and scientific inquiries. The school fell into decline afte ...

in medieval Europe due to the influence of Avicenna and Averroes, respectively. Avicenna was an important commentator on the works of Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

, modifying it with his own original thinking in some areas, notably logic. The main significance of Latin Avicennism lies in the interpretation of Avicennian doctrines such as the nature of the soul and his existence-essence distinction, along with the debates and censure that they raised in scholastic Europe. This was particularly the case in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, where so-called Arabic culture was proscribed

Proscription () is, in current usage, a 'decree of condemnation to death or banishment' (''Oxford English Dictionary'') and can be used in a political context to refer to state-approved murder or banishment. The term originated in Ancient Rome ...

in 1210, though the influence of his psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

and theory of knowledge upon William of Auvergne and Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus ( 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great, Albert of Swabia, Albert von Bollstadt, or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop, considered one of the great ...

have been noted.

The effects of Avicennism were later submerged by the much more influential Averroism

Averroism, also known as Rushdism, was a school of medieval philosophy based on the application of the works of 12th-century Andalusian philosopher Averroes, (Ibn Rushd in Arabic; 1126–1198) a commentator on Aristotle, in 13th-century Latin C ...

, the Aristotelianism of Averroes, one of the most influential Muslim philosophers in the West. Averroes disagreed with Avicenna's interpretations of Aristotle in areas such as the unity of the intellect, and it was his interpretation of Aristotle which had the most influence in medieval Europe. Dante Aligheri argues along Averroist lines for a secularist theory of the state in ''De Monarchia''.Majid Fakhry (2001). ''Averroes: His Life, Works and Influence'' p. 135 Oneworld Publications. . Averroes also developed the concept of "existence precedes essence

The proposition that existence precedes essence () is a central claim of existentialism, which reverses the traditional philosophical view that the essence (the nature) of a thing is more fundamental and immutable than its existence (the mere f ...

".

Al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111), archaically Latinized as Algazelus, was a Shafi'i Sunni Muslim scholar and polymath. He is known as one of the most prominent and influential jurisconsults, legal theoreticians, muftis, philosophers, the ...

also had an important influence on medieval Christian philosophy along with Jewish thinkers like Maimonides

Moses ben Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (, ) and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam (), was a Sephardic rabbi and Jewish philosophy, philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah schola ...

.

George Makdisi

George Abraham Makdisi was born in Detroit, Michigan, on May 15, 1920. He died in Media, Pennsylvania, on September 6, 2002. He was a professor of oriental studies. He studied first in the United States, and later in Lebanon. He then graduated in ...

(1989) has suggested that two particular aspects of Renaissance humanism have their roots in the medieval Islamic world, the "art of '' dictation'', called in Latin, ''ars dictaminis

''Ars dictaminis'' (or ''ars dictandi'') is the art of letter-writing, which often intersects with the art of rhetoric.

History of letter-writing

Greco-Roman theory

Early examples of letter-writing theory can be found in C. Julius Victor's ...

''," and "the humanist attitude toward classical language

According to the definition by George L. Hart, a classical language is any language with an independent literary tradition and a large body of ancient written literature.

Classical languages are usually extinct languages. Those that are still ...

".

He notes that dictation was a necessary part of Arabic scholarship (where the vowel sounds need to be added correctly based on the spoken word), and argues that the medieval Italian use of the term "ars dictaminis" makes best sense in this context. He also believes that the medieval humanist favouring of classical Latin over medieval Latin makes most sense in the context of a reaction to Arabic scholarship, with its study of the classical Arabic of the Koran in preference to medieval Arabic.

Sciences

During theIslamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of scientific, economic, and cultural flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 13th century.

This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign o ...

, certain advances were made in scientific fields, notably in mathematics and astronomy (algebra

Algebra is a branch of mathematics that deals with abstract systems, known as algebraic structures, and the manipulation of expressions within those systems. It is a generalization of arithmetic that introduces variables and algebraic ope ...

, spherical trigonometry

Spherical trigonometry is the branch of spherical geometry that deals with the metrical relationships between the edge (geometry), sides and angles of spherical triangles, traditionally expressed using trigonometric functions. On the sphere, ge ...

), and in chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

, etc. which were later also transmitted to the West.

Stefan of Pise translated into Latin around 1127 an Arab manual of medical theory. The method of algorism

Algorism is the technique of performing basic arithmetic by writing numbers in place value form and applying a set of memorized rules and facts to the digits. One who practices algorism is known as an algorist. This positional notation system ...

for performing arithmetic with the Hindu–Arabic numeral system

The Hindu–Arabic numeral system (also known as the Indo-Arabic numeral system, Hindu numeral system, and Arabic numeral system) is a positional notation, positional Decimal, base-ten numeral system for representing integers; its extension t ...

was developed by the Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

al-Khwarizmi

Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi , or simply al-Khwarizmi, was a mathematician active during the Islamic Golden Age, who produced Arabic-language works in mathematics, astronomy, and geography. Around 820, he worked at the House of Wisdom in B ...

in the 9th century, and introduced in Europe by Leonardo Fibonacci (1170–1250). A translation by Robert of Chester of the ''Algebra

Algebra is a branch of mathematics that deals with abstract systems, known as algebraic structures, and the manipulation of expressions within those systems. It is a generalization of arithmetic that introduces variables and algebraic ope ...

'' by al-Kharizmi is known as early as 1145. Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham (Latinization of names, Latinized as Alhazen; ; full name ; ) was a medieval Mathematics in medieval Islam, mathematician, Astronomy in the medieval Islamic world, astronomer, and Physics in the medieval Islamic world, p ...

(Alhazen, 980–1037) compiled treatises on optical sciences, which were used as references by Newton and Descartes. Medical sciences were also highly developed in Islam as testified by the Crusaders, who relied on Arab doctors on numerous occasions. Joinville

Joinville () is the largest city in Santa Catarina (state), Santa Catarina, in the Southern Brazil, Southern Region of Brazil. It is the third largest municipality in the southern region of Brazil, after the much larger state capitals of Curitib ...

reports he was saved in 1250 by a "Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

''Saracen'' ( ) was a term used both in Greek and Latin writings between the 5th and 15th centuries to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Rom ...

" doctor.

Almagest

The ''Almagest'' ( ) is a 2nd-century Greek mathematics, mathematical and Greek astronomy, astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Ptolemy, Claudius Ptolemy ( ) in Koine Greek. One of the most i ...

'') which were not obtainable in Latin in Western Europe, but which had survived and been translated into Arabic in the Muslim world. Gerard was said to have made his way to Toledo in Spain and learnt Arabic specifically because of his "love of the ''Almagest''". While there he took advantage of the "abundance of books in Arabic on every subject". Islamic Spain and Sicily were particularly productive areas because of the proximity of multi-lingual scholars. These scholars translated many scientific and philosophical texts from Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

into Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

. Gerard personally translated 87 books from Arabic into Latin, including the ''Almagest'', and also Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monotheistic teachings of Adam, Noah, Abraham, Mos ...

's ''On Algebra and Almucabala'', Jabir ibn Aflah's ''Elementa astronomica'', al-Kindi

Abū Yūsuf Yaʻqūb ibn ʼIsḥāq aṣ-Ṣabbāḥ al-Kindī (; ; ; ) was an Arab Muslim polymath active as a philosopher, mathematician, physician, and music theorist

Music theory is the study of theoretical frameworks for understandin ...

's ''On Optics'', Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Kathīr al-Farghānī's ''On Elements of Astronomy on the Celestial Motions'', al-Farabi

file:A21-133 grande.webp, thumbnail, 200px, Postage stamp of the USSR, issued on the 1100th anniversary of the birth of Al-Farabi (1975)

Abu Nasr Muhammad al-Farabi (; – 14 December 950–12 January 951), known in the Greek East and Latin West ...

's ''On the Classification of the Sciences'', the chemical and medical

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

works of Rhazes, the works of Thabit ibn Qurra Thabit () is an Arabic name

Arabic names have historically been based on a long naming system. Many people from Arabic-speaking and also non-Arab Muslim countries have not had given name, given, middle name, middle, and family names but rather a ...

and Hunayn ibn Ishaq

Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi (808–873; also Hunain or Hunein; ; ; known in Latin as Johannitius) was an influential Arab Nestorian Christian translator, scholar, physician, and scientist. During the apex of the Islamic Abbasid era, he worked w ...

, and the works of Arzachel, Jabir ibn Aflah, the Banū Mūsā, Abū Kāmil Shujā ibn Aslam

Abū Kāmil Shujāʿ ibn Aslam ibn Muḥammad Ibn Shujāʿ ( Latinized as Auoquamel, , also known as ''Al-ḥāsib al-miṣrī''—lit. "The Egyptian Calculator") (c. 850 – c. 930) was a prominent Egyptian mathematician during the Islamic Go ...

, Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi

Abū al-Qāsim Khalaf ibn al-'Abbās al-Zahrāwī al-Ansari (; c. 936–1013), popularly known as al-Zahrawi (), Latinised as Albucasis or Abulcasis (from Arabic ''Abū al-Qāsim''), was an Arab physician, surgeon and chemist from al-And ...

(Abulcasis), and Ibn al-Haytham (including the ''Book of Optics

The ''Book of Optics'' (; or ''Perspectiva''; ) is a seven-volume treatise on optics and other fields of study composed by the medieval Arab scholar Ibn al-Haytham, known in the West as Alhazen or Alhacen (965–c. 1040 AD).

The ''Book ...

'').

Alchemy

Westernalchemy

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

was directly dependent upon Arabic sources. Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

translations of Arabic alchemical works such as those attributed to Khalid ibn Yazid

Khālid ibn Yazīd (full name ''Abū Hāshim Khālid ibn Yazīd ibn Muʿāwiya ibn Abī Sufyān'', ), 668–704 or 709, was an Umayyad prince and purported alchemist.

As a son of the Umayyad caliph Yazid I, Khalid was supposed to become ca ...

(Latin: Calid), Jabir ibn Hayyan

Abū Mūsā Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (Arabic: , variously called al-Ṣūfī, al-Azdī, al-Kūfī, or al-Ṭūsī), died 806−816, is the purported author of a large number of works in Arabic, often called the Jabirian corpus. The treatises that ...

(Latin: Geber), Abu Bakr al-Razi

Abū Bakr al-Rāzī, also known as Rhazes (full name: ), , was a Persian physician, philosopher and alchemist who lived during the Islamic Golden Age. He is widely regarded as one of the most important figures in the history of medicine, and al ...

(Latin: Rhazes) and Ibn Umayl (Latin: Senior Zadith) were standard texts for European alchemists. Some important texts translated from the Arabic include the '' Liber de compositione alchemiae'' ("Book on the Composition of Alchemy") attributed to Khalid ibn Yazid and translated by Robert of Chester in 1144, the '' Liber de septuaginta'' ("Book of Seventy") attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan and translated by Gerard of Cremona

Gerard of Cremona (Latin: ''Gerardus Cremonensis''; c. 1114 – 1187) was an Italians, Italian translator of scientific books from Arabic into Latin. He worked in Toledo, Spain, Toledo, Kingdom of Castile and obtained the Arabic books in the libr ...

(before 1187), Abu Bakr al-Razi's , and Ibn Umayl's .

Many texts were also translated from anonymous Arabic sources and then falsely attributed to various authors, as for example the ("On Alums and Salts"), an 11th- or 12th-century text attributed in some manuscripts to Hermes Trismegistus

Hermes Trismegistus (from , "Hermes the Thrice-Greatest") is a legendary Hellenistic period figure that originated as a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth.A survey of the literary and archaeological eviden ...

or Abu Bakr al-Razi. Other texts were directly written in Latin but still attributed to Arabic authors, such as the influential ("The Sum of Perfection") and other 13th-/14th-century works by pseudo-Geber

Pseudo-Geber (or "Middle Latin, Latin pseudo-Geber") is the presumed author or group of authors responsible for a corpus of pseudepigraphic alchemical writings dating to the late 13th and early 14th centuries. These writings were falsely attrib ...

. Although these were original and often innovative texts, their anonymous authors probably knew Arabic and were still intimately familiar with Arabic sources.

Several technical Arabic words from Arabic alchemical works, such as ''alkali

In chemistry, an alkali (; from the Arabic word , ) is a basic salt of an alkali metal or an alkaline earth metal. An alkali can also be defined as a base that dissolves in water. A solution of a soluble base has a pH greater than 7.0. The a ...

'', found their way into European languages and became part of scientific vocabulary.

Astronomy, mathematics and physics

The translation ofAl-Khwarizmi

Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi , or simply al-Khwarizmi, was a mathematician active during the Islamic Golden Age, who produced Arabic-language works in mathematics, astronomy, and geography. Around 820, he worked at the House of Wisdom in B ...

's work greatly influenced mathematics in Europe. As Professor Victor J. Katz writes: "Most early algebra works in Europe in fact recognized that the first algebra works in that continent were translations of the work of al-Khwärizmï and other Islamic authors. There was also some awareness that much of plane and spherical trigonometry could be attributed to Islamic authors". The words algorithm

In mathematics and computer science, an algorithm () is a finite sequence of Rigour#Mathematics, mathematically rigorous instructions, typically used to solve a class of specific Computational problem, problems or to perform a computation. Algo ...

, deriving from Al-Khwarizmi's Latinized name Algorismi, and algebra, deriving from the title of his AD 820 book ''Hisab al-jabr w’al-muqabala, Kitab al-Jabr wa-l-Muqabala'' are themselves Arabic loanwords. This and other Arabic astronomical and mathematical works, such as those by al-Battani

Al-Battani (before 858929), archaically Latinized as Albategnius, was a Muslim astronomer, astrologer, geographer and mathematician, who lived and worked for most of his life at Raqqa, now in Syria. He is considered to be the greatest and mos ...

and Muhammad al-Fazari's ''Great Sindhind'' (based on the ''Surya Siddhanta

The ''Surya Siddhanta'' (; ) is a Sanskrit treatise in Indian astronomy dated to 4th to 5th century,Menso Folkerts, Craig G. Fraser, Jeremy John Gray, John L. Berggren, Wilbur R. Knorr (2017)Mathematics Encyclopaedia Britannica, Quote: "(...) i ...

'' and the works of Brahmagupta

Brahmagupta ( – ) was an Indian Indian mathematics, mathematician and Indian astronomy, astronomer. He is the author of two early works on mathematics and astronomy: the ''Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta'' (BSS, "correctly established Siddhanta, do ...

). were translated into Latin during the 12th century.

Al-Khazini

Abū al-Fath Abd al-Rahman Mansūr al-Khāzini or simply al-Khāzini (, flourished 1115–1130) was an Iranian astronomer, mechanician and physicist of Byzantine Greek origin who lived during the Seljuk Empire. His astronomical tables, written ...

's ''Zij

A ' () is an Islamic astronomical book that tabulates parameters used for astronomical calculations of the positions of the sun, moon, stars, and planets.

Etymology

The name ''zīj'' is derived from the Middle Persian term ' or ' "cord". Th ...

as-Sanjari'' (1115–1116) was translated into Greek by Gregory Chioniades

Gregory Chioniades (; c. 1240 – c. 1320) was a Byzantine Greek astronomer. He traveled to Persia, where he learned Persian mathematical and astronomical science, which he introduced into Byzantium upon his return from Persia and founded an astro ...

in the 13th century and was studied in the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

. The astronomical modifications to the Ptolemaic model

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, a ...

made by al-Battani

Al-Battani (before 858929), archaically Latinized as Albategnius, was a Muslim astronomer, astrologer, geographer and mathematician, who lived and worked for most of his life at Raqqa, now in Syria. He is considered to be the greatest and mos ...

and Averroes

Ibn Rushd (14 April 112611 December 1198), archaically Latinization of names, Latinized as Averroes, was an Arab Muslim polymath and Faqīh, jurist from Al-Andalus who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astron ...

led to non-Ptolemaic models produced by Mo'ayyeduddin Urdi (Urdi lemma), Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī

Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan al-Ṭūsī (1201 – 1274), also known as Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (; ) or simply as (al-)Tusi, was a Persian polymath, architect, philosopher, physician, scientist, and theologian. Nasir al-Din al-Tu ...

( Tusi-couple) and Ibn al-Shatir

ʿAbu al-Ḥasan Alāʾ al‐Dīn bin Alī bin Ibrāhīm bin Muhammad bin al-Matam al-Ansari, known as Ibn al-Shatir or Ibn ash-Shatir (; 1304–1375) was an Arab astronomer, mathematician and engineer. He worked as '' muwaqqit'' (موقت, timek ...

, which were later adapted into the Copernican heliocentric model. Abū al-Rayhān al-Bīrūnī's ''Ta'rikh al-Hind'' and ''Kitab al-qanun al-Mas’udi'' were translated into Latin as ''Indica'' and ''Canon Mas’udicus'' respectively.

Fibonacci

Leonardo Bonacci ( – ), commonly known as Fibonacci, was an Italians, Italian mathematician from the Republic of Pisa, considered to be "the most talented Western mathematician of the Middle Ages".

The name he is commonly called, ''Fibonacci ...

presented the first complete European account of Arabic numerals

The ten Arabic numerals (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9) are the most commonly used symbols for writing numbers. The term often also implies a positional notation number with a decimal base, in particular when contrasted with Roman numera ...

and the Hindu–Arabic numeral system

The Hindu–Arabic numeral system (also known as the Indo-Arabic numeral system, Hindu numeral system, and Arabic numeral system) is a positional notation, positional Decimal, base-ten numeral system for representing integers; its extension t ...

in his ''Liber Abaci

The or (Latin for "The Book of Calculation") was a 1202 Latin work on arithmetic by Leonardo of Pisa, posthumously known as Fibonacci. It is primarily famous for introducing both base-10 positional notation and the symbols known as Arabic n ...

'' (1202).

Al-Jayyani's ''The book of unknown arcs of a sphere'' (a treatise on spherical trigonometry) had a "strong influence on European mathematics". Regiomantus' ''On Triangles'' (c. 1463) certainly took his material on spherical trigonometry (without acknowledgment) from Arab sources. Much of the material was taken from the 12th-century work of Jabir ibn Aflah, as noted in the 16th century by Gerolamo Cardano

Gerolamo Cardano (; also Girolamo or Geronimo; ; ; 24 September 1501– 21 September 1576) was an Italian polymath whose interests and proficiencies ranged through those of mathematician, physician, biologist, physicist, chemist, astrologer, as ...

., p.4

A short verse used by Fulbert of Chartres (952-970 –1028) to help remember some of the brightest stars in the sky gives us the earliest known use of Arabic loanwords in a Latin text: "Aldebaran

Aldebaran () is a star in the zodiac constellation of Taurus. It has the Bayer designation α Tauri, which is Latinized to Alpha Tauri and abbreviated Alpha Tau or α Tau. Aldebaran varies in brightness from an apparent vis ...

stands out in Taurus, Menke and Rigel

Rigel is a blue supergiant star in the constellation of Orion. It has the Bayer designation β Orionis, which is Latinized to Beta Orionis and abbreviated Beta Ori or β Ori. Rigel is the brightest and most massive componentand ...

in Gemini, and Frons and bright Calbalazet in Leo. Scorpio, you have Galbalagrab; and you, Capricorn, Deneb

Deneb () is a blue supergiant star in the constellation of Cygnus. It is the brightest star in the constellation and the 19th brightest in the night sky, with an apparent magnitude slightly varying between +1.21 and +1.29. Deneb is one ...

. You, Batanalhaut, are alone enough for Pisces."

Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) wrote the ''Book of Optics'' (1021), in which he developed a theory of vision and light which built on the work of the Roman writer Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

(but which rejected Ptolemy's theory that light was emitted by the eye, insisting instead that light rays entered the eye), and was the most significant advance in this field until Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws of p ...

. The ''Book of Optics'' was an important stepping stone in the history of the scientific method and history of optics

Optics began with the development of lenses by the ancient Egyptians and Mesopotamians, followed by theories on light and vision developed by ancient Greek philosophers, and the development of geometrical optics in the Greco-Roman world. The w ...

.H. Salih, M. Al-Amri, M. El Gomati (2005).The Miracle of Light

, ''A World of Science'' 3 (3),

UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

The Latin translation of the ''Book of Optics'' influenced the works of many later European scientists, including Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the Scholastic accolades, scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English polymath, philosopher, scientist, theologian and Franciscans, Franciscan friar who placed co ...

and Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best know ...

.Richard Powers (University of Illinois

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC, U of I, Illinois, or University of Illinois) is a public university, public land-grant university, land-grant research university in the Champaign–Urbana metropolitan area, Illinois, United ...

)Best Idea; Eyes Wide Open

, ''

New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', April 18, 1999. The book also influenced other aspects of European culture. In religion

Religion is a range of social system, social-cultural systems, including designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics in religion, ethics, or ...

, for example, John Wycliffe

John Wycliffe (; also spelled Wyclif, Wickliffe, and other variants; 1328 – 31 December 1384) was an English scholastic philosopher, Christianity, Christian reformer, Catholic priest, and a theology professor at the University of Oxfor ...

, the intellectual progenitor of the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

, referred to Alhazen in discussing the seven deadly sin

In religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law or a law of the deities. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered ...

s in terms of the distortions in the seven types of mirror

A mirror, also known as a looking glass, is an object that Reflection (physics), reflects an image. Light that bounces off a mirror forms an image of whatever is in front of it, which is then focused through the lens of the eye or a camera ...

s analyzed in ''De aspectibus''. In literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

, Alhazen's ''Book of Optics'' is praised in Guillaume de Lorris

Guillaume de Lorris () was a French scholar and poet from Lorris. He was the author of the first section of the . Little is known about him, other than that he wrote the earlier section of the poem around 1230, and that the work was completed f ...

' ''Roman de la Rose

''Le Roman de la Rose'' (''The Romance of the Rose'') is a medieval poem written in Old French and presented as an allegory">allegorical romantic love is disclosed. Its two authors conceived it as a psychological allegory; throughout the Lover' ...

''. In art

Art is a diverse range of cultural activity centered around ''works'' utilizing creative or imaginative talents, which are expected to evoke a worthwhile experience, generally through an expression of emotional power, conceptual ideas, tec ...

, the ''Book of Optics'' laid the foundations for the linear perspective technique and may have influenced the use of optical aids in Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

art (see Hockney-Falco thesis). These same techniques were later employed in the maps made by European cartographers such as Paolo Toscanelli during the Age of Exploration

The Age of Discovery (), also known as the Age of Exploration, was part of the early modern period and overlapped with the Age of Sail. It was a period from approximately the 15th to the 17th century, during which Seamanship, seafarers fro ...

.

The theory of motion developed by Avicenna from Aristotelian physics

Aristotelian physics is the form of natural philosophy described in the works of the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC). In his work ''Physics'', Aristotle intended to establish general principles of change that govern all natural bodies ...

may have influenced Jean Buridan

Jean Buridan (; ; Latin: ''Johannes Buridanus''; – ) was an influential 14thcentury French scholastic philosopher.

Buridan taught in the faculty of arts at the University of Paris for his entire career and focused in particular on logic and ...

's theory of impetus

The theory of impetus, developed in the Middle Ages, attempts to explain the forced motion of a body, what it is, and how it comes about or ceases. It is important to note that in ancient and medieval times, motion was always considered absolute, ...

(the ancestor of the inertia

Inertia is the natural tendency of objects in motion to stay in motion and objects at rest to stay at rest, unless a force causes the velocity to change. It is one of the fundamental principles in classical physics, and described by Isaac Newto ...

and momentum

In Newtonian mechanics, momentum (: momenta or momentums; more specifically linear momentum or translational momentum) is the product of the mass and velocity of an object. It is a vector quantity, possessing a magnitude and a direction. ...

concepts). The work of Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

on classical mechanics

Classical mechanics is a Theoretical physics, physical theory describing the motion of objects such as projectiles, parts of Machine (mechanical), machinery, spacecraft, planets, stars, and galaxies. The development of classical mechanics inv ...

(superseding Aristotelian physics) was also influenced by earlier medieval physics writers, including Avempace

Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Yaḥyà ibn aṣ-Ṣā’igh at-Tūjībī ibn Bājja (), known simply as Ibn Bajja () or his Latinized name Avempace (; – 1138), was an Arab polymath, whose writings include works regarding astronomy, physic ...

.

Other notable works include those of Nur Ed-Din Al Betrugi, notably ''On the Motions of the Heavens'', Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi

Abu Ma‘shar al-Balkhi, Latinized as Albumasar (also ''Albusar'', ''Albuxar'', ''Albumazar''; full name ''Abū Maʿshar Jaʿfar ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿUmar al-Balkhī'' ;

, AH 171–272), was an early Persian Muslim astrologer, thought to be ...

's ''Introduction to Astrology'', Abū Kāmil Shujā ibn Aslam's ''Algebra'',V. J. Katz, ''A History of Mathematics: An Introduction'', p. 291. and '' De Proprietatibus Elementorum'', an Arabic work on geology written by a pseudo-Aristotle

Pseudo-Aristotle is a general cognomen for authors of philosophical or medical treatises who attributed their works to the Greek philosopher Aristotle, or whose work was later attributed to him by others. Such falsely attributed works are known a ...

.

Medicine

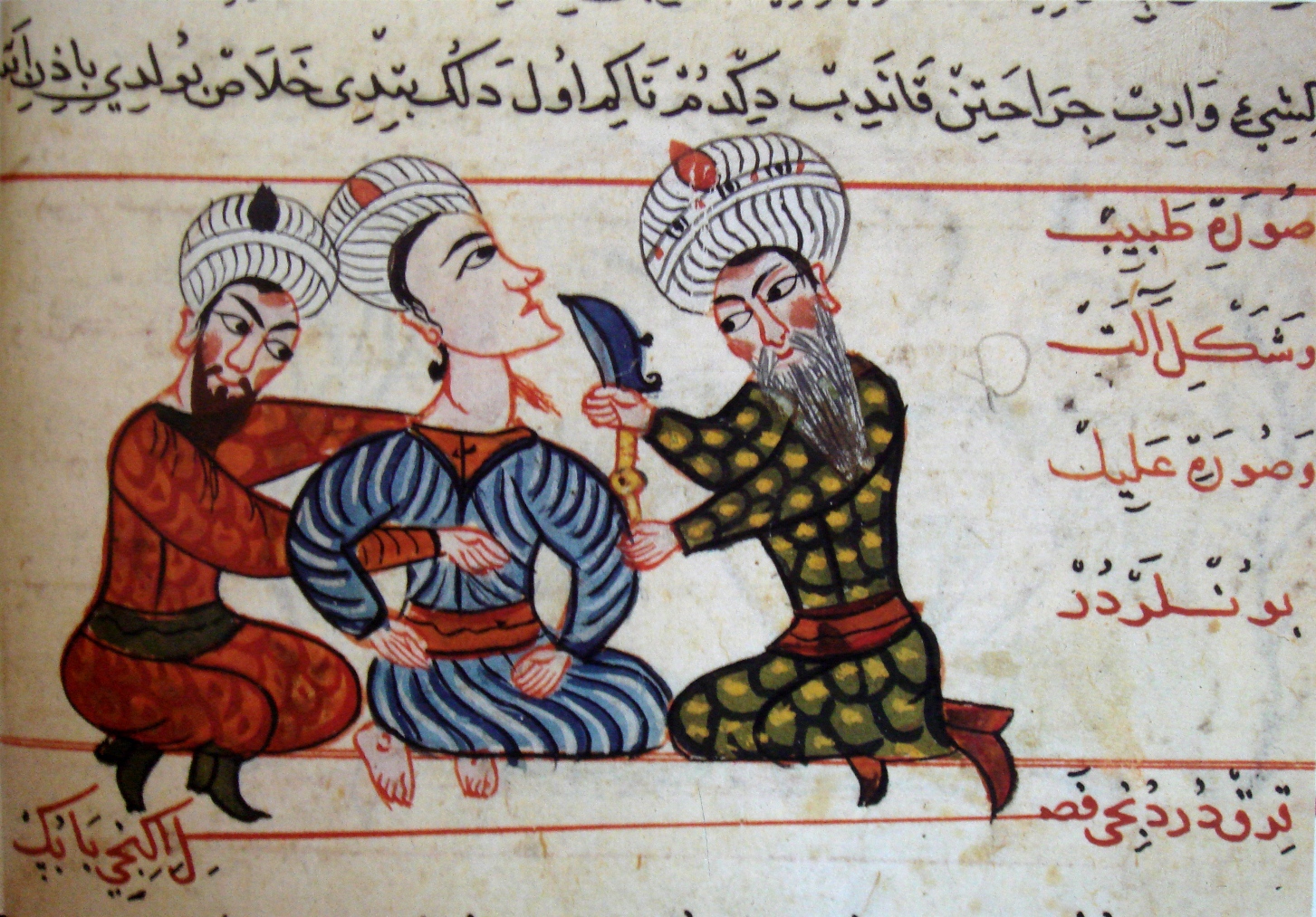

One of the most important medical works to be translated was

One of the most important medical works to be translated was Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian peoples, Iranian ...

's ''The Canon of Medicine

''The Canon of Medicine'' () is an encyclopedia of medicine in five books compiled by Avicenna (, ibn Sina) and completed in 1025. It is among the most influential works of its time. It presents an overview of the contemporary medical knowle ...

'' (1025), which was translated into Latin and then disseminated in manuscript and printed form throughout Europe. It remained a standard medical textbook in Europe until the early modern period, and during the 15th and 16th centuries alone, ''The Canon of Medicine'' was published more than thirty-five times.National Library of Medicine

The United States National Library of Medicine (NLM), operated by the United States federal government, is the world's largest medical library.

Located in Bethesda, Maryland, the NLM is an institute within the National Institutes of Health. I ...

digital archives Avicenna noted the contagious nature of some infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissue (biology), tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host (biology), host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmis ...

s (which he attributed to "traces" left in the air by a sick person), and discussed how to effectively test new medicines.David W. Tschanz, MSPH, PhD (August 2003). "Arab Roots of European Medicine", ''Heart Views'' 4 (2). He also wrote ''The Book of Healing

''The Book of Healing'' (; ; also known as ) is a scientific and philosophical encyclopedia written by Abu Ali ibn Sīna (also known as Avicenna). He most likely began to compose the book in 1014, completed it around 1020, and published it in ...

'', a more general encyclopedia of science and philosophy, which became another popular textbook in Europe. Muhammad ibn Zakarīya Rāzi wrote the ''Comprehensive Book of Medicine'', with its careful description of and distinction between measles

Measles (probably from Middle Dutch or Middle High German ''masel(e)'', meaning "blemish, blood blister") is a highly contagious, Vaccine-preventable diseases, vaccine-preventable infectious disease caused by Measles morbillivirus, measles v ...

and smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

, which was also influential in Europe. Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi wrote ''Kitab al-Tasrif

The ''Kitāb al-Taṣrīf'' (), known in English as The Method of Medicine, is a 30-volume Arabic encyclopedia on medicine and surgery, written near the year 1000 by Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (Abulcasis). It is available in translation.

The took a ...

'', an encyclopedia of medicine which was particularly famed for its section on surgery. It included descriptions and diagrams of over 200 surgical instruments, many of which he developed. The surgery section was translated into Latin by Gerard of Cremona in the 12th century, and used in European medical school

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, professional school, or forms a part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, ...

s for centuries, still being reprinted in the 1770s.D. Campbell, ''Arabian Medicine and Its Influence on the Middle Ages'', p. 3.AlbucasisScience museum on Albucasis Other medical Arabic works translated into Latin during the medieval period include the works of Razi and Avicenna (including ''The Book of Healing'' and ''The Canon of Medicine''), and

Ali ibn Abbas al-Majusi

'Ali ibn al-'Abbas al-Majusi (; died between 982 and 994), also known as Masoudi, or Latinized as Haly Abbas, was a Persian physician and psychologist from the Islamic Golden Age, most famous for the '' Kitab al-Maliki'' or '' Complete Book of ...

's medical encyclopedia, ''The Complete Book of the Medical Art''.

Mark of Toledo in the early 13th century translated the Qur'an

The Quran, also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation directly from God ('' Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which consist of individual verses ('). Besides ...

as well as various medical works.

Technology and culture

Agriculture and textiles

Variousfruits

In botany, a fruit is the seed-bearing structure in flowering plants (angiosperms) that is formed from the ovary after flowering.

Fruits are the means by which angiosperms disseminate their seeds. Edible fruits in particular have long propaga ...

and vegetables

Vegetables are edible parts of plants that are consumed by humans or other animals as food. This original meaning is still commonly used, and is applied to plants collectively to refer to all edible plant matter, including flowers, fruits, ...

were introduced to Europe in this period via the Middle East and North Africa, some from as far as China and India, including the artichoke, spinach

Spinach (''Spinacia oleracea'') is a leafy green flowering plant native to Central Asia, Central and Western Asia. It is of the order Caryophyllales, family Amaranthaceae, subfamily Chenopodioideae. Its leaves are a common vegetable consumed eit ...

, and aubergine

Eggplant ( US, CA, AU, PH), aubergine ( UK, IE, NZ), brinjal ( IN, SG, MY, ZA, SLE), or baigan ( IN, GY) is a plant species in the nightshade family Solanaceae. ''Solanum melongena'' is grown worldwide for its edible fruit, typica ...

.

Arts

Islamic decorative arts were highly valued imports to Europe throughout the Middle Ages. Largely because of accidents of survival, most surviving examples are those that were in the possession of the church. In the early period textiles were especially important, used for church vestments, shrouds, hangings and clothing for the elite.Islamic pottery

Islamic pottery occupied a geographical position between Chinese ceramics, and the pottery of the Byzantine Empire and Europe. For most of the period, it made great aesthetic achievements and influence as well, influencing Byzantium and Europe ...

of everyday quality was still preferred to European wares. Because decoration was mostly ornamental, or small hunting scenes and the like, and inscriptions were not understood, Islamic objects did not offend Christian sensibilities. Medieval art in Sicily is interesting stylistically because of the mixture of Norman, Arab and Byzantine influences in areas such as mosaic

A mosaic () is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/Mortar (masonry), mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and ...

s and metal inlays, sculpture

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

, and bronze-working.

Writing

The

The Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

Kufic

The Kufic script () is a style of Arabic script, that gained prominence early on as a preferred script for Quran transcription and architectural decoration, and it has since become a reference and an archetype for a number of other Arabic scripts ...

script was often imitated for decorative effect in the West during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, to produce what is known as pseudo-Kufic: "Imitations of Arabic in European art are often described as pseudo-Kufic, borrowing the term for an Arabic script that emphasizes straight and angular strokes, and is most commonly used in Islamic architectural decoration".Mack, p.51 Numerous cases of pseudo-Kufic are known from European art from around the 10th to the 15th century; usually the characters are meaningless, though sometimes a text has been copied. Pseudo-Kufic would be used as writing or as decorative elements in textiles, religious halos or frames. Many are visible in the paintings of Giotto

Giotto di Bondone (; – January 8, 1337), known mononymously as Giotto, was an List of Italian painters, Italian painter and architect from Florence during the Late Middle Ages. He worked during the International Gothic, Gothic and Italian Ren ...

. The exact reason for the incorporation of pseudo-Kufic in early Renaissance painting is unclear. It seems that Westerners mistakenly associated 13th- and 14th-century Middle-Eastern scripts as being identical with the scripts current during Jesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

's time, and thus found natural to represent early Christians in association with them: ''"In Renaissance art, pseudo-Kufic script was used to decorate the costumes of Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

heroes like David"''. Another reason might be that artist wished to express a cultural universality for the Christian faith, by blending together various written languages, at a time when the church had strong international ambitions.

Carpets

Carpet

A carpet is a textile floor covering typically consisting of an upper layer of Pile (textile), pile attached to a backing. The pile was traditionally made from wool, but since the 20th century synthetic fiber, synthetic fibres such as polyprop ...

s of Middle-Eastern origin, either from the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, the Levant or the Mamluk

Mamluk or Mamaluk (; (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural); translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave") were non-Arab, ethnically diverse (mostly Turkic, Caucasian, Eastern and Southeastern European) enslaved mercenaries, slave-so ...

state of Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

or Northern Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

, were a significant sign of wealth and luxury in Europe, as demonstrated by their frequent occurrence as important decorative features in paintings

Painting is a visual art, which is characterized by the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called "matrix" or " support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush. Other implements, ...

from the 13th century and continuing into the Baroque period. Such carpets, together with Pseudo-Kufic script offer an interesting example of the integration of Eastern elements into European painting, most particularly those depicting religious subjects.

Music

A number ofmusical instrument

A musical instrument is a device created or adapted to make Music, musical sounds. In principle, any object that produces sound can be considered a musical instrument—it is through purpose that the object becomes a musical instrument. A person ...

s used in European music were influenced by Arabic music

Arabic music () is the music of the Arab world with all its diverse List of music styles, music styles and genres. Arabic countries have many rich and varied styles of music and also many linguistic Varieties of Arabic, dialects, with each countr ...

al instruments, including the rebec (an ancestor of the violin

The violin, sometimes referred to as a fiddle, is a wooden chordophone, and is the smallest, and thus highest-pitched instrument (soprano) in regular use in the violin family. Smaller violin-type instruments exist, including the violino picc ...

) from the ''rebab

''Rebab'' (, ''rabāba'', variously spelled ''rebap'', ''rubob'', ''rebeb'', ''rababa'', ''rabeba'', ''robab'', ''rubab'', ''rebob'', etc) is the name of several related string instruments that independently spread via Islamic trading rout ...

'' and the naker from ''naqareh'' The oud is cited as one of several precursors to the modern guitar

The guitar is a stringed musical instrument that is usually fretted (with Fretless guitar, some exceptions) and typically has six or Twelve-string guitar, twelve strings. It is usually held flat against the player's body and played by strumming ...

.

Some scholars believe that the

Some scholars believe that the troubador

A troubadour (, ; ) was a composer and performer of Old Occitan lyric poetry during the High Middle Ages (1100–1350). Since the word ''troubadour'' is etymologically masculine, a female equivalent is usually called a ''trobairitz''.

The tro ...

s may have had Arabian origins, with Magda Bogin stating that the Arab poetic and musical tradition was one of several influences on European "courtly love poetry". Évariste Lévi-Provençal and other scholars stated that three lines of a poem by William IX of Aquitaine

William IX ( or , ; 22 October 1071 – 10 February 1126), called the Troubadour, was the Duke of Aquitaine and Gascony and Count of Poitou (as William VII) between 1086 and his death. He was also one of the leaders of the Crusade of 1101.

Thoug ...

were in some form of Arabic, indicating a potential Andalusian origin for his works. The scholars attempted to translate the lines in question and produced various different translations; the medievalist Istvan Frank contended that the lines were not Arabic at all, but instead the result of the rewriting of the original by a later scribe.

The theory that the troubadour tradition was created by William after his experiences with Moorish

The term Moor is an exonym used in European languages to designate the Muslim populations of North Africa (the Maghreb) and the Iberian Peninsula (particularly al-Andalus) during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a single, distinct or self-defi ...

arts while fighting with the Reconquista

The ''Reconquista'' (Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese for ) or the fall of al-Andalus was a series of military and cultural campaigns that European Christian Reconquista#Northern Christian realms, kingdoms waged ag ...

in Spain has been championed by Ramón Menéndez Pidal

Ramón Menéndez Pidal (; 13 March 1869 – 14 November 1968) was a Spanish philologist and historian."Ramon Menendez Pidal", ''Almanac of Famous People'' (2011) ''Biography in Context'', Gale, Detroit He worked extensively on the history of t ...

and Idries Shah

Idries Shah (; , , ; 16 June 1924 – 23 November 1996), also known as Idris Shah, Indries Shah, né Sayyid, Sayed Idries el-Hashemite, Hashimi (Arabic: ) and by the pen name Arkon Daraul, was an Afghans, Afghan author, thinker and teacher in ...

, though George T. Beech states that there is only one documented battle that William fought in Spain, and it occurred towards the end of his life. However, Beech adds that William and his father did have Spanish individuals within their extended family, and that while there is no evidence he himself knew Arabic, he may have been friendly with some European Christians who could speak the language. Others state that the notion that William created the concept of troubadours is itself incorrect, and that his "songs represent not the beginnings of a tradition but summits of achievement in that tradition."

Technology

A number of technologies in the Islamic world were adopted in European medieval technology. These included various

A number of technologies in the Islamic world were adopted in European medieval technology. These included various crops

A crop is a plant that can be grown and harvested extensively for profit or subsistence. In other words, a crop is a plant or plant product that is grown for a specific purpose such as food, fibre, or fuel.

When plants of the same species a ...

; various astronomical instruments, including the Greek astrolabe

An astrolabe (; ; ) is an astronomy, astronomical list of astronomical instruments, instrument dating to ancient times. It serves as a star chart and Model#Physical model, physical model of the visible celestial sphere, half-dome of the sky. It ...

which Arab astronomers developed and refined into such instruments as the '' Quadrans Vetus'', a universal horary quadrant which could be used for any latitude

In geography, latitude is a geographic coordinate system, geographic coordinate that specifies the north-south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from −90° at t ...

,David A. King (2002). "A Vetustissimus Arabic Text on the Quadrans Vetus", ''Journal for the History of Astronomy'' 33, p. 237–255 37–238 and the ''Saphaea'', a universal astrolabe invented by Abū Ishāq Ibrāhīm al-Zarqālī; the astronomical sextant; various surgical instruments, including refinements on older forms and completely new inventions; and advanced gearing in waterclocks and automata. Ahmad Y HassanTransfer Of Islamic Technology To The West, Part II: Transmission Of Islamic Engineering

, ''History of Science and Technology in Islam''

Distillation

Distillation, also classical distillation, is the process of separating the component substances of a liquid mixture of two or more chemically discrete substances; the separation process is realized by way of the selective boiling of the mixt ...

was known to the Greeks and Romans, but was rediscovered in medieval Europe through the Arabs. The word alcohol

Alcohol may refer to:

Common uses

* Alcohol (chemistry), a class of compounds

* Ethanol, one of several alcohols, commonly known as alcohol in everyday life

** Alcohol (drug), intoxicant found in alcoholic beverages

** Alcoholic beverage, an alco ...

(to describe the liquid produced by distillation) comes from Arabic ''al-kuhl''. The word alembic

An alembic (from , originating from , 'cup, beaker') is an alchemical still consisting of two vessels connected by a tube, used for distillation of liquids.

Description

The complete distilling apparatus consists of three parts:

* the "" ...

(via the Greek Ambix) comes from Arabic ''al-anbiq''. Islamic examples of complex water clocks and automata are believed to have strongly influenced the European craftsmen who produced the first mechanical clocks in the 13th century.

The importation of both the ancient and new technology from the Middle East and the Orient

The Orient is a term referring to the East in relation to Europe, traditionally comprising anything belonging to the Eastern world. It is the antonym of the term ''Occident'', which refers to the Western world.

In English, it is largely a meto ...

to Renaissance Europe represented “one of the largest technology transfers in world history.”