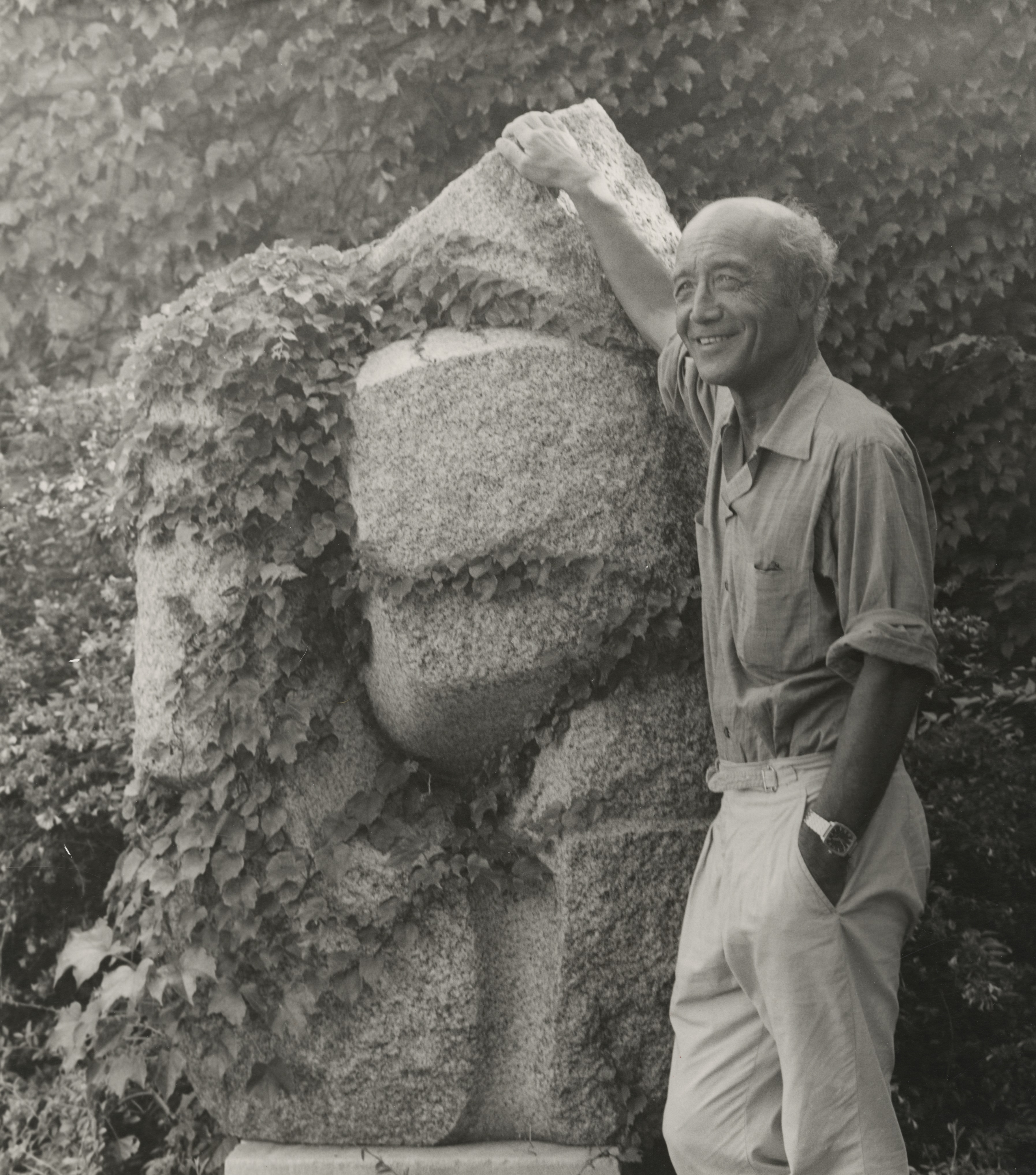

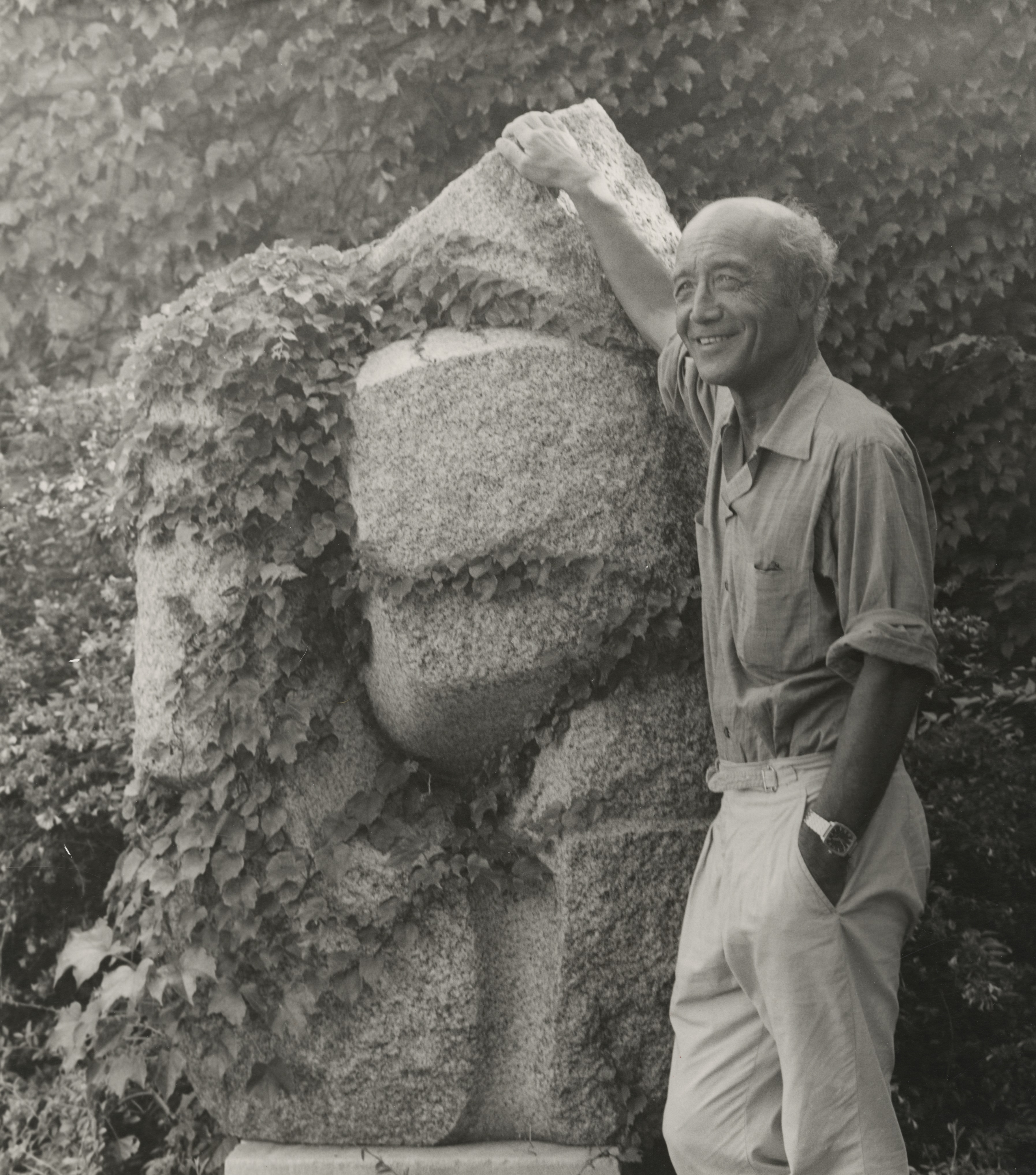

Isamu Noguchi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

was an American artist, furniture designer and

Cummings, Paul. Retrieved October 19, 2006. Another influence was his mother, who in 1923 moved from Japan to California, then later to New York. In 1924, while still enrolled at Columbia, Noguchi followed his mother's advice to take night classes at the Leonardo da Vinci Art School. The school's head, Onorio Ruotolo, was immediately impressed by Noguchi's work. Only three months later, Noguchi held his first exhibit, a selection of

The Noguchi Museum. Retrieved October 18, 2006. He was awarded the grant despite being three years short of the age requirement.

(Drag to year, then month) In September 2003, The

* ''Martha Graham'' (1929),

* ''Martha Graham'' (1929),

at the Noguchi Museum website In 2004, the US Postal Service issued a 37-cent stamp honoring Noguchi.

The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum is devoted to the preservation, documentation, presentation, and interpretation of the work of Isamu Noguchi. It is supported by a variety of public and private funding bodies. The US copyright representative for the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum is the Artists Rights Society. In 2012, it was announced that, in order to reduce liability, Noguchi's

The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum is devoted to the preservation, documentation, presentation, and interpretation of the work of Isamu Noguchi. It is supported by a variety of public and private funding bodies. The US copyright representative for the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum is the Artists Rights Society. In 2012, it was announced that, in order to reduce liability, Noguchi's

Noguchi for Danh Vo: Counterpoint

/ref> The exhibition took place in the M+ Pavilion, Hong Kong, from November 16, 2018, to April 22, 2019.

''American Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s An Illustrated Survey,''

(New York School Press, 2003.) . p. 254–257 * Marika Herskovic

''New York School Abstract Expressionists Artists Choice by Artists,''

(New York School Press, 2000.) . p. 39; p. 270–273

* Kenjiro Okazaki,

A Place to Bury Names

' (about Isamu Noguchi and Shirai Seiichi)

The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden MuseumDrawings by Isamu Noguchi

from the

landscape architect

A landscape architect is a person who is educated in the field of landscape architecture. The practice of landscape architecture includes: site analysis, site inventory, site planning, land planning, planting design, grading, storm water manage ...

whose career spanned six decades from the 1920s. Known for his sculpture and public artworks, Noguchi also designed stage sets for various Martha Graham

Martha Graham (May 11, 1894 – April 1, 1991) was an American modern dancer, teacher and choreographer, whose style, the Graham technique, reshaped the dance world and is still taught in academies worldwide.

Graham danced and taught for over s ...

productions, and several mass-produced lamps and furniture pieces, some of which are still manufactured and sold.

In 1947, Noguchi began a collaboration with the Herman Miller

MillerKnoll, Inc., doing business as Herman Miller, is an American company that produces office furniture, equipment, and home furnishings. Its best known designs include the Aeron chair, Noguchi table, Marshmallow sofa, Mirra chair, and t ...

company, when he joined with George Nelson, Paul László and Charles Eames

Charles Ormond Eames Jr. (June 17, 1907 – August 21, 1978) was an American designer, architect and filmmaker. In professional partnership with his wife Ray-Bernice Kaiser Eames, he made groundbreaking contributions in the fields of architect ...

to produce a catalog containing what is often considered to be the most influential body of modern furniture ever produced, including the iconic Noguchi table which remains in production today. His work is displayed at the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum in New York City.

Early life (1904–1922)

Isamu Noguchi was born in Los Angeles, the son of Yone Noguchi, a Japanese poet who was acclaimed in the United States, and Léonie Gilmour, an American writer who edited much of Noguchi's work. Yone had ended his relationship with Gilmour earlier that year and planned to marry ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'', locally known as ''The'' ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'' or ''WP'', is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C., the national capital. It is the most widely circulated newspaper in the Washington m ...

'' reporter Ethel Armes

Ethel Marie Armes (1876 – 1945) was an American journalist, author and historian.

Biography

Ethel Marie Armes was born in Washington, D.C., to Col. George Augustus Armes and Lucy Hamilton Kerr (daughter of John Bozman Kerr), Armes was raised ...

. After proposing to Armes, Yone left for Japan in late August, settling in Tokyo and awaiting her arrival; their engagement fell through months later when Armes learned of Léonie and her newborn son.

In 1906, Yone invited Léonie to come to Tokyo with their son. She at first refused, but growing anti-Japanese sentiment

Anti-Japanese sentiment (also called Japanophobia, Nipponophobia and anti-Japanism) is the fear or dislike of Japan or Japanese culture. Anti-Japanese sentiment can take many forms, from antipathy toward Japan as a country to racist hatr ...

following the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

eventually convinced her to take up Yone's offer. The two departed from San Francisco in March 1907, arriving in Yokohama

is the List of cities in Japan, second-largest city in Japan by population as well as by area, and the country's most populous Municipalities of Japan, municipality. It is the capital and most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a popu ...

to meet Yone. Upon arrival, their son was finally given the name Isamu (, "courage"). However, Yone had married a Japanese woman by the time they arrived, and was mostly absent from his son's childhood. After again separating from Yone, Léonie and Isamu moved several times throughout Japan.

In 1912, while the two were living in Chigasaki

is a Cities of Japan, city located in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 242,798 and a population density of 6800 people per km2. The total area of the city is .

Geography

The city is located on the eastern ban ...

, Isamu's half-sister, pioneer of the American Modern Dance

Modern dance is a broad genre of western concert dance, concert or theatrical dance which includes dance styles such as ballet, folk, ethnic, religious, and social dancing; and primarily arose out of Europe and the United States in the late 19th ...

movement Ailes Gilmour

Ailes Gilmour (January 27, 1912 – April 16, 1993) was a Japanese Americans, Japanese American dancer who was one of the young pioneers of the American Modern dance, Modern Dance movement of the 1930s. She was one of the first members of Martha ...

, was born to Léonie and an unknown Japanese father. Here, Léonie had a house built for the three of them, a project that she had the 8-year-old Isamu "oversee". Nurturing her son's artistic ability, she put him in charge of their garden and apprenticed him to a local carpenter. However, they moved once again in December 1917 to an English-speaking community in Yokohama.

In 1918, Noguchi was sent back to the US for schooling in Rolling Prairie, Indiana. After graduation, he left with Dr. Edward Rumely

Edward Aloysius Rumely (1882 – November 26, 1964) was a physician, educator, and newspaper man from Indiana.

Education

Rumely was born in La Porte, Indiana, in 1882. He attended University of Notre Dame, Oxford University and the Univers ...

to LaPorte, where he found boarding with a Swedenborgian

The New Church (or Swedenborgianism) can refer to any of several historically related Christian denominations that developed under the influence of the theology of Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772). The Swedenborgian tradition is considered to ...

pastor, Samuel Mack. Noguchi began attending La Porte High School, graduating in 1922. During this period of his life, he was known by the name "Sam Gilmour".

Early artistic career (1922–1927)

After high school, Noguchi explained his desire to become an artist to Rumely; though Rumely preferred that Noguchi become a doctor, he acknowledged Noguchi's request and sent him toConnecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

to work as an apprentice to his friend Gutzon Borglum

John Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum (March 25, 1867 – March 6, 1941) was an American sculpture, sculptor best known for his work on Mount Rushmore. He is also associated with various other public works of art across the U.S., including Stone Moun ...

. Best known as the creator of Mount Rushmore National Memorial, Borglum was at the time working on the group called ''Wars of America

''Wars of America'' is a colossal bronze sculpture by Mount Rushmore sculptor Gutzon Borglum and his assistant Luigi Del Bianco containing "forty-two humans and two horses", located in Military Park (Newark), Military Park in Newark, New Jersey. ...

'' for the city of Newark, New Jersey, a work of art that includes forty-two figures and two equestrian sculptures. As one of Borglum's apprentices, Noguchi received little training as a sculptor; his tasks included arranging the horses and modeling for the monument as General Sherman. He did, however, pick up some skills in casting from Borglum's Italian assistants, later fashioning a bust of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

. At summer's end, Borglum told Noguchi that he would never become a sculptor, prompting him to reconsider Rumely's prior suggestion.

He then traveled to New York City, reuniting with the Rumely family at their new residence, and with Dr. Rumely's financial aid enrolled in February 1922 as a premedical student at Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

. Soon after, he met the bacteriologist

A bacteriologist is a microbiologist, or similarly trained professional, in bacteriology— a subdivision of microbiology that studies bacteria, typically Pathogenic bacteria, pathogenic ones. Bacteriologists are interested in studying and learnin ...

Hideyo Noguchi

, also known as , was a prominent Japanese bacteriologist at the Rockefeller University, Rockefeller Institute known for his work on syphilis, serology, immunology, and contributing to the long term understanding of neurosyphilis.

Before the Ro ...

, who urged him to reconsider art, as well as the Japanese dancer Michio Itō, whose celebrity status later helped Noguchi find acquaintances in the art world."Interview with Isamu Noguchi. November 7, 1973."Cummings, Paul. Retrieved October 19, 2006. Another influence was his mother, who in 1923 moved from Japan to California, then later to New York. In 1924, while still enrolled at Columbia, Noguchi followed his mother's advice to take night classes at the Leonardo da Vinci Art School. The school's head, Onorio Ruotolo, was immediately impressed by Noguchi's work. Only three months later, Noguchi held his first exhibit, a selection of

plaster

Plaster is a building material used for the protective or decorative coating of walls and ceilings and for moulding and casting decorative elements. In English, "plaster" usually means a material used for the interiors of buildings, while "re ...

and terracotta

Terracotta, also known as terra cotta or terra-cotta (; ; ), is a clay-based non-vitreous ceramic OED, "Terracotta""Terracotta" MFA Boston, "Cameo" database fired at relatively low temperatures. It is therefore a term used for earthenware obj ...

works. He soon dropped out of Columbia University to pursue sculpture full-time, changing his name from Gilmour (the surname he had used for years) to Noguchi.

After moving into his own studio, Noguchi found work through commissions for portrait busts, and won the Logan Medal of the Arts

The Logan Medal of the Arts was an arts prize initiated in 1907 and associated with the Art Institute of Chicago, the Frank G Logan family and the Society for Sanity in Art. From 1917 through 1940, 270 awards were given for contributions to Amer ...

. During this time, he frequented ''avant garde'' shows at the galleries of such modernists as Alfred Stieglitz

Alfred Stieglitz (; January 1, 1864 – July 13, 1946) was an American photographer and modern art promoter who was instrumental over his 50-year career in making photography an accepted art form. In addition to his photography, Stieglitz was k ...

and J. B. Neuman, and took a particular interest in a show of the works of Romanian-born sculptor Constantin Brâncuși

Constantin Brâncuși (; February 19, 1876 – March 16, 1957) was a Romanian sculptor, painter, and photographer who made his career in France. Considered one of the most influential sculptors of the 20th century and a pioneer of modernism ...

.

In late 1926, Noguchi applied for a Guggenheim Fellowship

Guggenheim Fellowships are Grant (money), grants that have been awarded annually since by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, endowed by the late Simon Guggenheim, Simon and Olga Hirsh Guggenheim. These awards are bestowed upon indiv ...

. In his letter of application, he proposed to study stone and wood cutting and to gain "a better understanding of the human figure" in Paris for a year, then spend another year traveling through Asia, exhibit his work, and return to New York."Proposal to the Guggenheim Foundation (1927)"The Noguchi Museum. Retrieved October 18, 2006. He was awarded the grant despite being three years short of the age requirement.

Early travels (1927–1937)

Noguchi arrived in Paris in April 1927 and soon afterward met the American author Robert McAlmon, who brought him to Constantin Brâncuși's studio for an introduction. Despite a language barrier between the two artists (Noguchi barely spoke French, and Brâncuși did not speak English), Noguchi was taken in as Brâncuși's assistant for the next seven months. During this time, Noguchi gained his footing instone sculpture

In geology, rock (or stone) is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks form the Earth's ...

, a medium with which he was unacquainted, though he would later admit that one of Brâncuși's greatest teachings was to appreciate "the value of the moment". Meanwhile, Noguchi found himself in good company in France, with letters of introduction from Michio Itō helping him to meet such artists as Jules Pascin

Julius Mordecai Pincas (March 31, 1885 – June 2, 1930), known as Pascin (, erroneously or ), Jules Pascin, also known as the "Prince of Montparnasse", was a Bulgarian artist of the School of Paris, known for his paintings and drawings. He ...

and Alexander Calder

Alexander "Sandy" Calder (; July 22, 1898 – November 11, 1976) was an American sculptor known both for his innovative mobile (sculpture), mobiles (kinetic sculptures powered by motors or air currents) that embrace chance in their aesthetic, hi ...

, who lived in the studio of Arno Breker

Arno Breker (19 July 1900 – 13 February 1991) was a German sculptor who is best known for his public works in Nazi Germany, where he was endorsed by the authorities as the antithesis of degenerate art. He was made official state sculptor, ...

. They became friends and Breker did a bronze bust of Noguchi.

Noguchi only produced one sculpture – his marble ''Sphere Section'' – in his first year, but during his second year he stayed in Paris and continued his training in stoneworking

Stonemasonry or stonecraft is the creation of buildings, structures, and sculpture using stone as the primary material. Stonemasonry is the craft of shaping and arranging stones, often together with mortar and even the ancient lime mortar ...

with the Italian sculptor Mateo Hernandes, producing over twenty more abstractions of wood, stone and sheet metal

Sheet metal is metal formed into thin, flat pieces, usually by an industrial process.

Thicknesses can vary significantly; extremely thin sheets are considered foil (metal), foil or Metal leaf, leaf, and pieces thicker than 6 mm (0.25 ...

. Noguchi's next major destination was India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, from which he would travel east; he arrived in London to read up on Oriental sculpture, but was denied the extension to the Guggenheim Fellowship he needed.

In February 1929, he left for New York City. Brâncuși had recommended that Noguchi visit Romany Marie's café in Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village, or simply the Village, is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street (Manhattan), 14th Street to the north, Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the s ...

.Robert Schulman. '' Romany Marie: The Queen of Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village, or simply the Village, is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street (Manhattan), 14th Street to the north, Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the s ...

'' (pp. 109–110). Louisville

Louisville is the most populous city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, sixth-most populous city in the Southeast, and the 27th-most-populous city in the United States. By land area, it is the country's 24th-largest city; however, by populatio ...

: Butler Books, 2006. . Noguchi did so and there met Buckminster Fuller

Richard Buckminster Fuller (; July 12, 1895 – July 1, 1983) was an American architect, systems theorist, writer, designer, inventor, philosopher, and futurist. He styled his name as R. Buckminster Fuller in his writings, publishing more t ...

, with whom he collaborated on several projects, including the modeling of Fuller's Dymaxion car. Includes images

Upon his return, Noguchi's abstract sculptures made in Paris were exhibited in his first one-man show at the Eugene Schoen Gallery. After none of his works sold, Noguchi altogether abandoned abstract art for portrait busts in order to support himself. He soon found himself accepting commissions from wealthy and celebrity clients. A 1930 exhibit of several busts, including those of Martha Graham

Martha Graham (May 11, 1894 – April 1, 1991) was an American modern dancer, teacher and choreographer, whose style, the Graham technique, reshaped the dance world and is still taught in academies worldwide.

Graham danced and taught for over s ...

and Buckminster Fuller

Richard Buckminster Fuller (; July 12, 1895 – July 1, 1983) was an American architect, systems theorist, writer, designer, inventor, philosopher, and futurist. He styled his name as R. Buckminster Fuller in his writings, publishing more t ...

, garnered positive reviews, and after less than a year of portrait sculpture, Noguchi had earned enough money to continue his trip to Asia.

Noguchi left for Paris in April 1930, and two months later received his visa to ride the Trans-Siberian Railway

The Trans-Siberian Railway, historically known as the Great Siberian Route and often shortened to Transsib, is a large railway system that connects European Russia to the Russian Far East. Spanning a length of over , it is the longest railway ...

. He opted to visit Japan first rather than India, but after learning that his father Yone did not want his son to visit using his surname, a shaken Noguchi instead departed for Beijing

Beijing, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's List of national capitals by population, most populous national capital city as well as ...

. In China, he studied brush painting with Qi Baishi

Qi Baishi (1 January 1864 – 16 September 1957) was a Chinese painting, Chinese painter, noted for the whimsical, often playful style of his works. Born to a peasant family from Xiangtan, Hunan, Qi taught himself to paint, sparked by the Ma ...

, staying for six months before finally sailing for Japan. Even before his arrival in Kobe

Kobe ( ; , ), officially , is the capital city of Hyōgo Prefecture, Japan. With a population of around 1.5 million, Kobe is Japan's List of Japanese cities by population, seventh-largest city and the third-largest port city after Port of Toky ...

, Japanese newspapers had picked up on Noguchi's supposed reunion with his father; though he denied that this was the reason for his visit, the two did meet in Tokyo. He later arrived in Kyoto

Kyoto ( or ; Japanese language, Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in the Kansai region of Japan's largest and most populous island of Honshu. , the city had a population of 1.46 million, making it t ...

to study pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other raw materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. The place where such wares are made by a ''potter'' is al ...

with Uno Jinmatsu. Here he took note of local Zen gardens and haniwa

The are terracotta clay figures that were made for ritual use and buried with the dead as funerary objects during the Kofun period (3rd to 6th centuries AD) of the history of Japan. ''Haniwa'' were created according to the ''wazumi'' technique ...

, clay funerary figures of the Kofun period

The is an era in the history of Japan from about 300 to 538 AD (the date of the introduction of Buddhism), following the Yayoi period. The Kofun and the subsequent Asuka periods are sometimes collectively called the Yamato period. This period is ...

which inspired his terracotta

Terracotta, also known as terra cotta or terra-cotta (; ; ), is a clay-based non-vitreous ceramic OED, "Terracotta""Terracotta" MFA Boston, "Cameo" database fired at relatively low temperatures. It is therefore a term used for earthenware obj ...

''The Queen''.

Noguchi returned to New York amidst the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

, finding few clients for his portrait busts. However, he hoped to sell his newly produced sculptures and brush paintings from Asia. Though very few sold, Noguchi regarded this one-man exhibition (which began in February 1932 and toured Chicago, the west coast, and Honolulu

Honolulu ( ; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, located in the Pacific Ocean. It is the county seat of the Consolidated city-county, consolidated City and County of Honol ...

) as his "most successful". Additionally, his next attempt to break into abstract art

Abstract art uses visual language of shape, form, color and line to create a Composition (visual arts), composition which may exist with a degree of independence from visual references in the world. ''Abstract art'', ''non-figurative art'', ''non- ...

, a large streamlined figure of dancer Ruth Page entitled ''Miss Expanding Universe'', was poorly received. In January 1933 he worked in Chicago with Santiago Martínez Delgado on a mural for Chicago's Century of Progress

A Century of Progress International Exposition, also known as the Chicago World's Fair, was a world's fair held in the city of Chicago, Illinois, United States, from 1933 to 1934. The fair, registered under the Bureau International des Exposit ...

Exposition, then again found a business for his portrait busts. He moved to London in June hoping to find more work, but returned in December just before his mother Leonie's death.

Beginning in February 1934, Noguchi began submitting his first designs for public spaces and monuments to the Public Works of Art Program. One such design, a monument to Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

, remained unrealized for decades. Another design, a gigantic pyramidal earthwork entitled ''Monument to the American Plow'', was similarly rejected, and his "sculptural landscape" of a playground, ''Play Mountain'', was personally rejected by Parks Commissioner Robert Moses

Robert Moses (December 18, 1888 – July 29, 1981) was an American urban planner and public official who worked in the New York metropolitan area during the early to mid-20th century. Moses is regarded as one of the most powerful and influentia ...

. He was eventually dropped from the program, and again supported himself by sculpting portrait busts. In early 1935, after another solo exhibition, the '' New York Sun's'' Henry McBride labeled Noguchi's ''Death

Death is the end of life; the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain a living organism. Death eventually and inevitably occurs in all organisms. The remains of a former organism normally begin to decompose sh ...

'', depicting a lynched

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged or convicted transgressor or to intimidate others. It can also be an extreme form of in ...

African-American, as "a little Japanese mistake". That same year he produced the set for ''Frontier

A frontier is a political and geographical term referring to areas near or beyond a boundary.

Australia

The term "frontier" was frequently used in colonial Australia in the meaning of country that borders the unknown or uncivilised, th ...

'', the first of many set designs for Martha Graham.

After the Federal Art Project

The Federal Art Project (1935–1943) was a New Deal program to fund the visual arts in the United States. Under national director Holger Cahill, it was one of five Federal Project Number One projects sponsored by the Works Progress Administratio ...

started up, Noguchi again put forth designs, one of which was another earthwork chosen for the New York City airport entitled ''Relief Seen from the Sky''; following further rejection, Noguchi left for Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywood ...

, where he again worked as a portrait sculptor to earn money for a sojourn in Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

. Here, Noguchi was chosen to design his first public work, a relief mural for the Abelardo Rodriguez market in Mexico City

Mexico City is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Mexico, largest city of Mexico, as well as the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North America. It is one of the most important cultural and finan ...

. The 20-meter-long ''History as Seen from Mexico in 1936'' was hugely political and socially conscious, featuring such modern symbols as the Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

swastika

The swastika (卐 or 卍, ) is a symbol used in various Eurasian religions and cultures, as well as a few Indigenous peoples of Africa, African and Indigenous peoples of the Americas, American cultures. In the Western world, it is widely rec ...

, a hammer and sickle

The hammer and sickle (Unicode: ) is a communist symbol representing proletarian solidarity between industrial and agricultural workers. It was first adopted during the Russian Revolution at the end of World War I, the hammer representing wo ...

, and the equation ''E'' = ''mc''². Noguchi also met Frida Kahlo

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón (; 6 July 1907 – 13 July 1954) was a Mexican painter known for her many portraits, self-portraits, and works inspired by the nature and artifacts of Mexico. Inspired by Culture of Mexico, the country' ...

during this time and had a brief but passionate affair with her; they remained friends until her death.

Further career in the United States (1937–1948)

Noguchi returned to New York in 1937. He designed the Zenith Radio Nurse, the iconic originalbaby monitor

A baby monitor, also known as a baby alarm, is a radio system used to remotely listen to sounds made by an infant. An audio monitor consists of a transmitter unit, equipped with a microphone, placed near to the child. It transmits the sounds by ...

now held in many museum collections. The Radio Nurse was Noguchi's first major design commission and he called it "my only strictly industrial design".

He again began to turn out portrait busts, and after various proposals was selected for two sculptures. The first of these, a fountain built of automobile parts for the Ford Motor Company

Ford Motor Company (commonly known as Ford) is an American multinational corporation, multinational automobile manufacturer headquartered in Dearborn, Michigan, United States. It was founded by Henry Ford and incorporated on June 16, 1903. T ...

's exhibit at the 1939 New York World's Fair

The 1939 New York World's Fair (also known as the 1939–1940 New York World's Fair) was an world's fair, international exposition at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in Queens, New York City, New York, United States. The fair included exhibitio ...

, was thought of poorly by critics and Noguchi alike but nevertheless introduced him to fountain-construction and magnesite

Magnesite is a mineral with the chemical formula ( magnesium carbonate). Iron, manganese, cobalt, and nickel may occur as admixtures, but only in small amounts.

Occurrence

Magnesite occurs as veins in and an alteration product of ultramafic r ...

. Conversely, his second sculpture, a nine-ton stainless steel

Stainless steel, also known as inox, corrosion-resistant steel (CRES), or rustless steel, is an iron-based alloy that contains chromium, making it resistant to rust and corrosion. Stainless steel's resistance to corrosion comes from its chromi ...

bas-relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces remain attached to a solid background of the same material. The term ''relief'' is from the Latin verb , to raise (). To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

entitled ''News'', was unveiled over the entrance to the Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American not-for-profit organization, not-for-profit news agency headquartered in New York City.

Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association, and produces news reports that are dist ...

building at the Rockefeller Center

Rockefeller Center is a complex of 19 commerce, commercial buildings covering between 48th Street (Manhattan), 48th Street and 51st Street (Manhattan), 51st Street in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. The 14 original Art De ...

in April 1940 to much praise. Following further rejections of his playground designs, Noguchi left on a cross-country road trip with Arshile Gorky and Gorky's fiancée in July 1941, eventually separating from them to go to Hollywood.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

, anti-Japanese sentiment was energized in the United States, and in response Noguchi formed "Nisei

is a Japanese language, Japanese-language term used in countries in North America and South America to specify the nikkeijin, ethnically Japanese children born in the new country to Japanese-born immigrants, or . The , or Second generation imm ...

Writers and Artists for Democracy". Noguchi and other group leaders wrote to influential officials, including the congressional committee headed by Representative John H. Tolan, hoping to halt the internment of Japanese Americans

United States home front during World War II, During World War II, the United States forcibly relocated and Internment, incarcerated about 120,000 people of Japanese Americans, Japanese descent in ten #Terminology debate, concentration camps opera ...

; Noguchi later attended the hearings but had little effect on their outcome. He later helped organize a documentary of the internment, but left California before its release; as a legal resident of New York, he was allowed to return home. He hoped to prove Japanese-American loyalty by somehow contributing to the war effort, but when other governmental departments turned him down, Noguchi met with John Collier, head of the Office of Indian Affairs, who persuaded him to travel to the internment camp located on an Indian reservation

An American Indian reservation is an area of land land tenure, held and governed by a List of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States#Description, U.S. federal government-recognized Native American tribal nation, whose gov ...

in Poston, Arizona

Poston is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in La Paz County, Arizona, United States, in the Parker Valley. The population was 285 at the 2010 census, down from 389 in 2000.

During World War II, Poston was the si ...

, to promote arts and crafts

The Arts and Crafts movement was an international trend in the Decorative arts, decorative and fine arts that developed earliest and most fully in the British Isles and subsequently spread across the British Empire and to the rest of Europe and ...

and community.Duus, 2004. p. 169

Noguchi arrived at the Poston camp in May 1942, becoming its only voluntary internee. Noguchi first worked in a carpentry shop, but his hope was to design parks and recreational areas within the camp. Although he created several plans at Poston, among them designs for baseball fields, swimming pools, and a cemetery, he found that the War Relocation Authority

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was a United States government agency established to handle the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It also operated the Fort Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter in Oswego, New York, which was t ...

had no intention of implementing them. To the WRA camp administrators he was a troublesome interloper from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and to the internees he was an agent of the camp administration. Many did not trust him and saw him as a spy. He had found nothing in common with the Nisei

is a Japanese language, Japanese-language term used in countries in North America and South America to specify the nikkeijin, ethnically Japanese children born in the new country to Japanese-born immigrants, or . The , or Second generation imm ...

, who regarded him as a strange outsider.

In June, Noguchi applied for release, but intelligence officers labeled him as a "suspicious person" due to his involvement in "Nisei Writers and Artists for Democracy". He was finally granted a month-long furlough on November 12, but never returned; though he was granted a permanent leave afterward, he soon afterward received a deportation order. The Federal Bureau of Investigation, accusing him of espionage, launched into a full investigation of Noguchi which ended only through the American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is an American nonprofit civil rights organization founded in 1920. ACLU affiliates are active in all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico. The budget of the ACLU in 2024 was $383 million.

T ...

's intervention. Noguchi would later retell his wartime experiences in the British World War II television documentary series ''The World at War

''The World at War'' is a 26-episode British documentary television series that chronicles the events of the Second World War. Produced in 1973 at a cost of around £880,000 (), it was the most expensive factual series ever made at the time. ...

''.

Upon his return to New York, Noguchi took a new studio in Greenwich Village. Throughout the 1940s, Noguchi's sculpture drew from the ongoing surrealist

Surrealism is an art movement, art and cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists aimed to allow the unconscious mind to express itself, often resulting in the depiction of illogical or dreamlike s ...

movement; these works include not only various mixed-media constructions and landscape reliefs, but ''lunars'' – self-illuminating reliefs – and a series of biomorphic sculptures made of interlocking slabs. The most famous of these assembled-slab works, ''Kouros'', was first shown in a September 1946 exhibition, helping to cement his place in the New York art scene.

In 1947 he began a working relationship with Herman Miller

MillerKnoll, Inc., doing business as Herman Miller, is an American company that produces office furniture, equipment, and home furnishings. Its best known designs include the Aeron chair, Noguchi table, Marshmallow sofa, Mirra chair, and t ...

of Zeeland, Michigan. This relationship was to prove very fruitful, resulting in several designs that have become symbols of the modernist

Modernism was an early 20th-century movement in literature, visual arts, and music that emphasized experimentation, abstraction, and Subjectivity and objectivity (philosophy), subjective experience. Philosophy, politics, architecture, and soc ...

style, including the iconic Noguchi table, which remains in production today. Noguchi also developed a relationship with Knoll, designing furniture and lamps. During this period he continued his involvement with theater, designing sets for Martha Graham's ''Appalachian Spring

''Appalachian Spring'' is an American ballet created by the choreographer Martha Graham and the composer Aaron Copland, later arranged as an orchestral work. Commissioned by Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, Copland composed the ballet music for Gra ...

'' and John Cage

John Milton Cage Jr. (September 5, 1912 – August 12, 1992) was an American composer and music theorist. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and Extended technique, non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one ...

and Merce Cunningham

Mercier Philip "Merce" Cunningham (April 16, 1919 – July 26, 2009) was an American dancer and choreographer who was at the forefront of American modern dance for more than 50 years. He frequently collaborated with artists of other discipl ...

's production of ''The Seasons''. Near the end of his time in New York, he also found more work designing public spaces, including a commission for the ceilings of the Time-Life

Time Life, Inc. (also habitually represented with a hyphen as Time-Life, Inc., even by the company itself) was an American multi-media conglomerate company formerly known as a prolific production/publishing company and Direct marketing, direct ...

headquarters.

In March 1949, Noguchi had his first one-person show in New York since 1935 at the Charles Egan Gallery.Noguchi Museum: Timeline(Drag to year, then month) In September 2003, The

Pace Gallery

The Pace Gallery is a contemporary and modern art gallery with 9 locations worldwide. It was founded in Boston by Arne Glimcher in 1960. His son, Marc Glimcher, is now president and CEO. Pace Gallery operates in New York, London, Hong Kong, ...

held an exhibition of Noguchi's work at their 57th Street gallery. The exhibition, entitled ''33 MacDougal Alley: The Interlocking Sculpture of Isamu Noguchi'', featured eleven of the artist’s interlocking sculptures. This was the first exhibition to illustrate the historical significance of the relationship between MacDougal Alley and Isamu Noguchi’s sculptural work.

Bollingen Fellowship and life in Japan (1948–1952)

Following the suicide of his artist friend Arshile Gorky in 1948, and a failed romantic relationship with Nayantara Pandit (the niece of Indian nationalistJawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

), Noguchi applied for a Bollingen Fellowship to travel the world, proposing to study public space as research for a book about the "environment of leisure". It wasn't until 15 years after his death that this project came to fruition as an international traveling exhibition and a deluxe limited-edition publication, organized by Noguchi's long-time assistant and curator at the Noguchi Museum, Bonnie Rychlak.

Later years (1952–1988)

In his later years Noguchi gained in prominence and acclaim, installing his large-scale works in many of the world's major cities. He was married to the ethnic-Japanese icon of Chinese song and cinema Yoshiko Yamaguchi, between 1952 and 1957. From 1959 to 1988, Noguchi was in a long-term friendship with Priscilla Morgan, a New York talent agent and art patron who strove to protect Noguchi's artistic legacy after his death. In 1955, he designed the sets and costumes for a controversial theatre production of ''King Lear

''The Tragedy of King Lear'', often shortened to ''King Lear'', is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare. It is loosely based on the mythological Leir of Britain. King Lear, in preparation for his old age, divides his ...

'' starring John Gielgud

Sir Arthur John Gielgud ( ; 14 April 1904 – 21 May 2000) was an English actor and theatre director whose career spanned eight decades. With Ralph Richardson and Laurence Olivier, he was one of the trinity of actors who dominated the Britis ...

.

In 1962, he was elected to membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters

The American Academy of Arts and Letters is a 300-member honor society whose goal is to "foster, assist, and sustain excellence" in American literature, Music of the United States, music, and Visual art of the United States, art. Its fixed number ...

.

In 1971, he was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

.

In 1986, he represented the United States at the Venice Biennale, showing a number of his Akari light sculptures.

In 1987, he was awarded the National Medal of Arts

The National Medal of Arts is an award and title created by the United States Congress in 1984, for the purpose of honoring artists and Patronage, patrons of the arts. A prestigious American honor, it is the highest honor given to artists and ar ...

.

Isamu Noguchi died on December 30, 1988, at the age of 84 at New York University Medical Center of pneumonia. In its obituary for Noguchi, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' called him "a versatile and prolific sculptor whose earthy stones and meditative gardens bridging East and West have become landmarks of 20th-century art".

Notable works

Honolulu Museum of Art

The Honolulu Museum of Art (formerly the Honolulu Academy of Arts) is an art museum in Honolulu, Hawaii, Hawaii. The museum is the largest of its kind in the state, and was founded in 1922 by Anna Rice Cooke. It has one of the largest single co ...

, Honolulu, Hawaii

* ''Tsuneko-san'' (1931), Honolulu Museum of Art

* ''News'' (1938), 50 Rockefeller Plaza

* ''Lunar Landscape'' (1943–44), now at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

* ''Coffee Table'' (1944), an iconic item of Mid-century Modern

Mid-century modern (MCM) is a movement in interior design, product design, graphic design, architecture and urban development that was present in all the world, but more popular in North America, Brazil and Europe from roughly 1945 to 197 ...

furniture

* ''Texas Sculpture'' (1960–1961), First National Bank of Fort Worth Plaza, Fort Worth, Texas

* Decorative railings for a bridge in Peace Park

A transboundary protected area (TBPA) is an ecological protected area that spans boundaries of more than one country or sub-national entity. Such areas are also known as transfrontier conservation areas (TFCAs) or peace parks.

TBPAs exist in ma ...

(1951–1952), Hiroshima, Japan

* ''666 Fifth Avenue Ceiling and Waterfall'', also known as ''Landscape of the Cloud'' (1956–1958), formerly in the lobby of 666 Fifth Avenue

660 Fifth Avenue (formerly 666 Fifth Avenue and the Tishman Building) is a 41-story office building on the west side of Fifth Avenue between 52nd and 53rd Streets in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City, United States. The off ...

, New York City

* ''Gardens for UNESCO'', UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

Headquarters (1956–1958), Paris, France

*'' Floor Frame'' (1962; castings from 1963 to 1987). A 1963 cast is displayed at The White House Rose Garden, in Washington, D.C.

* ''The Cry'' (1962), Albright–Knox Art Gallery

The Buffalo AKG Art Museum, formerly known as the Albright–Knox Art Gallery, is an art museum located adjacent to Delaware Park, Buffalo, New York, United States.

The museum shows modern art and contemporary art. It is directly opposite Buff ...

, Buffalo, New York

* ''Sun'' (1963), The Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller Empire State Plaza Art Collection, Albany, New York

* ''Sunken Garden for Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

The Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library () is the rare book library and literary archive of the Yale University Library in New Haven, Connecticut. It is one of the largest buildings in the world dedicated to rare books and manuscripts and ...

'' (1960–1964), Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut

* ''Sunken Garden for Chase Manhattan Bank Plaza'' (1961–1964), New York City

* ''Gardens for IBM

International Business Machines Corporation (using the trademark IBM), nicknamed Big Blue, is an American Multinational corporation, multinational technology company headquartered in Armonk, New York, and present in over 175 countries. It is ...

Headquarters'' (1964), Armonk, New York

* ''Billy Rose

Billy Rose (born William Samuel Rosenberg; September 6, 1899 – February 10, 1966) was an American impresario, theatrical showman, lyricist and columnist. For years both before and after World War II, Billy Rose was a major force in entertainm ...

Sculpture Garden'' (1960–1965), Israel Museum

The Israel Museum (, ''Muze'on Yisrael'', ) is an Art museum, art and archaeology museum in Jerusalem. It was established in 1965 as Israel's largest and foremost cultural institution, and one of the world's leading Encyclopedic museum, encyclopa ...

, Jerusalem

* ''Children's Land'' (1965–1966), a temporary children's playground for ''Kodomo no Kuni'', Yokohama, Japan

* ''Red Cube'' (1968), HSBC Building, New York City

* Octetra (1968), Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. It was first located near Spoleto Cathedral

Spoleto Cathedral (; ''Duomo di Spoleto'') is the cathedral of the Archdiocese of Spoleto-Norcia created in 1821, previously that of the diocese of Spoleto, and the principal church of the Umbrian city of Spoleto, in Italy. It is dedicated to the A ...

It is an abstract painted concrete sculpture.

* ''Untitled Red (1965–66)'', Honolulu Museum of Art

The Honolulu Museum of Art (formerly the Honolulu Academy of Arts) is an art museum in Honolulu, Hawaii, Hawaii. The museum is the largest of its kind in the state, and was founded in 1922 by Anna Rice Cooke. It has one of the largest single co ...

* ''Sky Viewing Sculpture'' (1969), Western Washington University Public Sculpture Collection, Bellingham, Washington

* '' Black Sun'' (1969), Volunteer Park, Seattle, Washington

* ''Expo '70

The or Expo '70 was a world's fair held in Suita, Osaka Prefecture, Japan, between 15 March and 13 September 1970. Its theme was "Progress and Harmony for Mankind." In Japanese, Expo '70 is often referred to as . It was the first world's fair ...

Fountains'', Osaka, Japan

* ''Twin Sculptures, Bayerische Vereinsbank, Munich'' (1970–1972), Munich, Germany

* '' Playscapes, Piedmont Park, Atlanta, Georgia'' (1975–1976), a children's playground in Atlanta, Georgia

* ''Intetra'' (1976), Society of the Four Arts, Palm Beach, Florida

* ''Portal'' (1976), Justice Center Complex, Cleveland, Ohio

* ''Sky Gate'' (1976–1977), Honolulu Hale, Honolulu, Hawaii

* ''Dodge Fountain'' (1972–1979) and Philip A. Hart Plaza in Detroit, Michigan (created in collaboration with Shoji Sadao)

* ''Untitled'' (1981), obsidian

Obsidian ( ) is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extrusive rock, extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock. Produced from felsic lava, obsidian is rich in the lighter element ...

and wood sculpture, Honolulu Museum of Art

The Honolulu Museum of Art (formerly the Honolulu Academy of Arts) is an art museum in Honolulu, Hawaii, Hawaii. The museum is the largest of its kind in the state, and was founded in 1922 by Anna Rice Cooke. It has one of the largest single co ...

* California Scenario and ''Spirit of the Lima Bean'' (1980–1982), Noguchi Garden, Costa Mesa, California

* ''To the Issei'' (1980-1983), Noguchi Plaza, Los Angeles, California

* '' Bolt of Lightning...A Memorial to Benjamin Franklin'' (conceived 1933, installed 1984), Franklin Square, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

* ''Constellation for Louis Kahn'' (1983), Kimbell Art Museum

The Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, hosts an art collection as well as traveling art exhibitions, educational programs and an extensive research library. Its initial artwork came from the private collection of Kay and Velma Kimbell, w ...

, Fort Worth, Texas

* ''Lillie and Hugh Roy Cullen Sculpture Garden

The Lillie and Hugh Roy Cullen Sculpture Garden is a sculpture garden located at the Museum of Fine Arts (Houston), Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH) in Houston, Texas, United States. Designed by artist and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi, th ...

'' (1986) for the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH), is an art museum located in the Houston Museum District of Houston, Texas. The permanent collection of the museum spans more than 5,000 years of history with nearly 80,000 works from six continents. Follo ...

, Texas

* Bayfront Park (1980–1996), Miami, Florida

* Moerenuma Park (2004), Sapporo, Japan

His final project was the design for Moerenuma Park, a park in Sapporo, Japan. Designed in 1988 shortly before his death, it was completed by Noguchi's partner, Shoji Sadao, and Architects 5. It opened to the public in 2004.

Gallery

Honors

Noguchi received theEdward MacDowell Medal

The Edward MacDowell Medal is an award which has been given since 1960 to one person annually who has made an outstanding contribution to American culture and the arts. It is given by MacDowell, the first artist residency program in the United St ...

for Outstanding Lifetime Contribution to the Arts in 1982; the National Medal of Arts in 1987; and the Order of the Sacred Treasure

The is a Japanese Order (distinction), order, established on 4 January 1888 by Emperor Meiji as the Order of Meiji. Originally awarded in eight classes (from 8th to 1st, in ascending order of importance), since 2003 it has been awarded in six c ...

from the Japanese government in 1988.Official Biographyat the Noguchi Museum website In 2004, the US Postal Service issued a 37-cent stamp honoring Noguchi.

Legacy

catalogue raisonné

A (or critical catalogue) is an annotated listing of the works of an artist or group of artists and can contain all works or a selection of works categorised by different parameters such as medium or period.

A ''catalogue raisonné'' is normal ...

would be published as an online-only, ever-modifiable work-in-progress. It began in 1979 with the publication by Nancy Grove and Diane Botnick for Grove Press. After 1980 Bonnie Rychlak continued the research and became the managing editor of the catalogue until 2011. After 2011, Shaina Larrivee continued the project and 2015, Alex Ross became the managing editor.

Exhibition

M+ in partnership with the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum organized an exhibition of Isamu Noguchi and Danh Võ./ref> The exhibition took place in the M+ Pavilion, Hong Kong, from November 16, 2018, to April 22, 2019.

See also

* Wabi-sabi * Japanese in New York CityNotes

References

* * * * Marika Herskovic''American Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s An Illustrated Survey,''

(New York School Press, 2003.) . p. 254–257 * Marika Herskovic

''New York School Abstract Expressionists Artists Choice by Artists,''

(New York School Press, 2000.) . p. 39; p. 270–273

* Kenjiro Okazaki,

A Place to Bury Names

' (about Isamu Noguchi and Shirai Seiichi)

Further reading

* Altshuler, Bruce (1995). ''Isamu Noguchi (Modern Masters)''. Abbeville Press, Inc. . * Ashton, Dore; Hare, Denise Brown (1993). ''Noguchi East and West''. University of California Press. * Cort, Louise Allison, Bert Winther-Tamaki. ''Isamu Noguchi and modern Japanese ceramics: a close embrace of the earth'', Washington, DC: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; Berkeley:University of California Press

The University of California Press, otherwise known as UC Press, is a publishing house associated with the University of California that engages in academic publishing. It was founded in 1893 to publish scholarly and scientific works by faculty ...

, 2003.

* Herrera, Hayden. ''Listening To Stone: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi''. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. New York. 2015.

* Lyford, Amy. ''Isamu Noguchi's Modernism: Negotiating Race, Labor, and Nation, 1930–1950'' (University of California Press; 2013)

* Noguchi, Isamu et al. (1986). ''Space of Akari and Stone''. Chronicle Books. .

*

* Torres, Ana Maria; Williams, Tod (2000). ''Isamu Noguchi: A Study of Space''. The Monticelli Press. .

* Winther-Tamaki, Bert. ''Art in the encounter of nations: Japanese and American artists in the early postwar years.'' Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2001.

* Weilacher, Udo: "Isamu Noguchi: Space as Sculpture", in: Weilacher, Udo (1999): ''Between Landscape Architecture and Land Art'', Birkhauser Publisher. .

* Rychlak, Bonnie, (2021) "On Noguchi's Studio and the Bollingen Archives," transcribed interview for ''Looking Forward: Ivorypress at Twenty-Five'', London and Madrid: Ivory Press, p. 53-548.

* Rychlak, Bonnie (2004). "Forward," ''A Sculptor's World by Isamu Noguchi.'' Reprint from 1968. Gottingen, Germany: Steidl.

* Rychlak, Bonnie (2002) "A Glimpse of Isamu's Life and Works," for ''Isamu Noguchi, Human Aspect as a Contemporary: 54 Witnesses in Japan and America'', Kagawa, Japan: The Shikoku Shimbun.

External links

The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum

from the

University of Michigan Museum of Art

The University of Michigan Museum of Art (UMMA) is one of the largest university art museums in the United States, located in Ann Arbor, Michigan, with . Built as a war memorial in 1909 for the university's fallen alumni from the Civil War, Alu ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Noguchi, Isamu

1904 births

1988 deaths

Abstract expressionist artists

American furniture designers

American landscape and garden designers

American artists of Japanese descent

American landscape architects

Modernist designers

Japanese-American internees

Kyoto laureates in Arts and Philosophy

Artists from Tokyo

Artists from Yokohama

Artists from Los Angeles

Artists from Manhattan

People from Greenwich Village

Columbia College (New York) alumni

Art Students League of New York people

United States National Medal of Arts recipients

Recipients of the Order of the Sacred Treasure

20th-century American sculptors

20th-century American male artists

American male sculptors

Treasury Relief Art Project artists

National Sculpture Society members

Sculptors from California

Sculptors from New York (state)