Irish Citizen Army on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Irish Citizen Army (), or ICA, was a

The Irish Citizen Army (), or ICA, was a

The Citizen Army arose out of the lockout and strike strike of the

The Citizen Army arose out of the lockout and strike strike of the

The Irish Citizen Army underwent a complete reorganisation in 1914.

In March of that year, police attacked a demonstration of the Citizen Army and arrested Jack White, its commander. Seán O'Casey, the playwright, then suggested that the ICA needed a more formal organisation. He wrote a constitution, stating the Army's principles as follows: "the ownership of Ireland, moral and material, is vested of right in the people of Ireland" and to "sink all difference of birth property and creed under the common name of the Irish people".

Larkin insisted that all members also be members of a trade union, if eligible. In mid-1914, White resigned as ICA commander in order to join the mainstream nationalist

The Irish Citizen Army underwent a complete reorganisation in 1914.

In March of that year, police attacked a demonstration of the Citizen Army and arrested Jack White, its commander. Seán O'Casey, the playwright, then suggested that the ICA needed a more formal organisation. He wrote a constitution, stating the Army's principles as follows: "the ownership of Ireland, moral and material, is vested of right in the people of Ireland" and to "sink all difference of birth property and creed under the common name of the Irish people".

Larkin insisted that all members also be members of a trade union, if eligible. In mid-1914, White resigned as ICA commander in order to join the mainstream nationalist

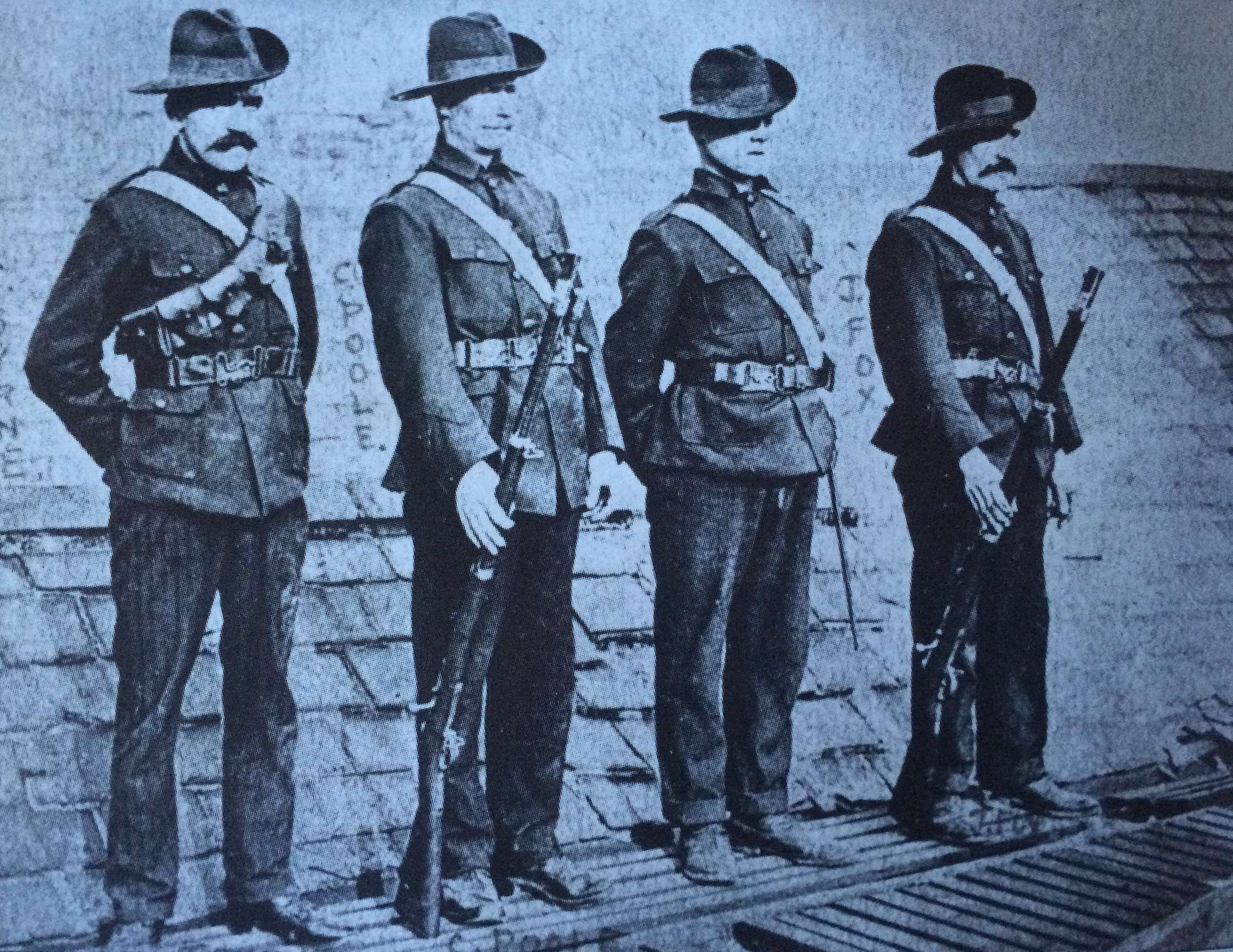

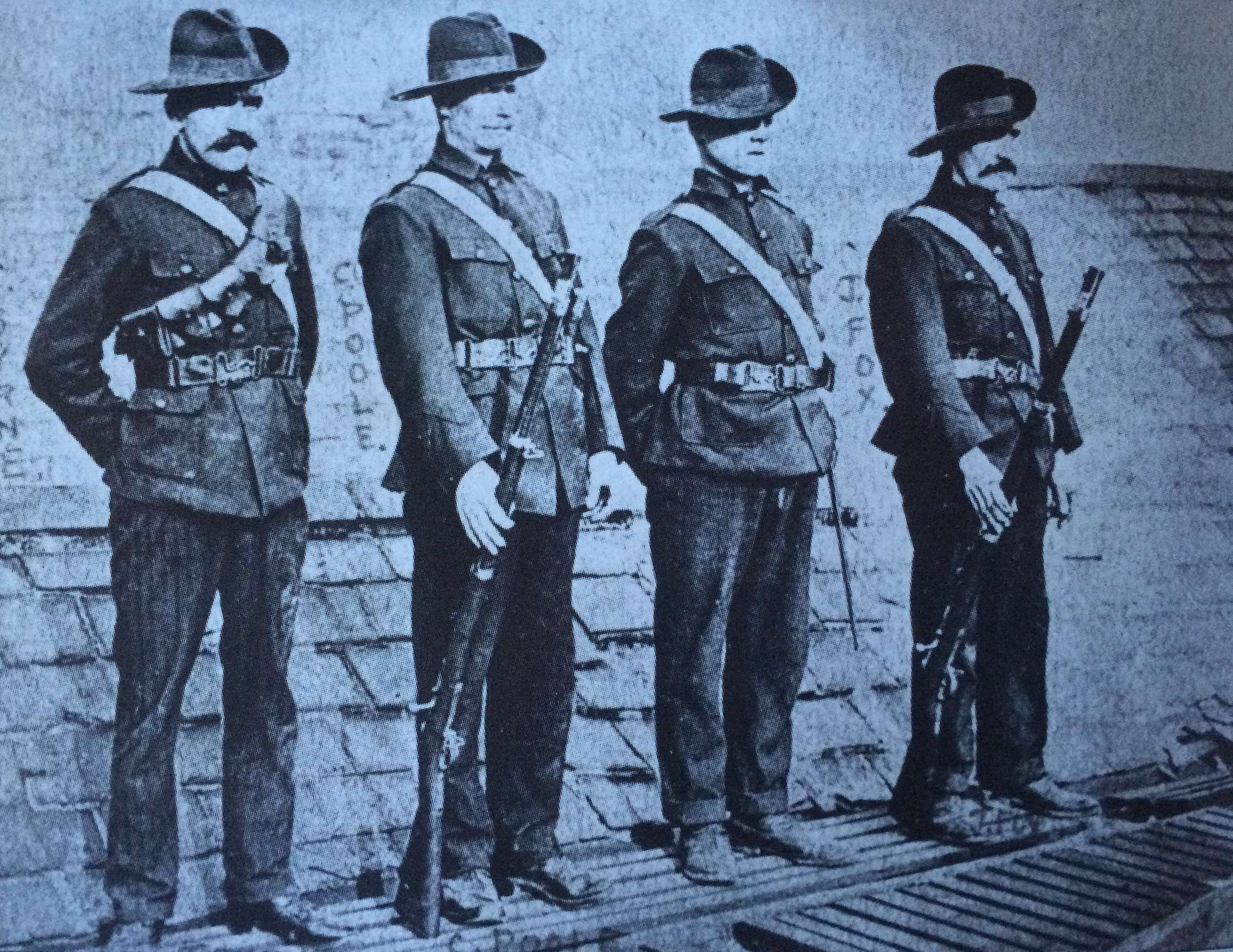

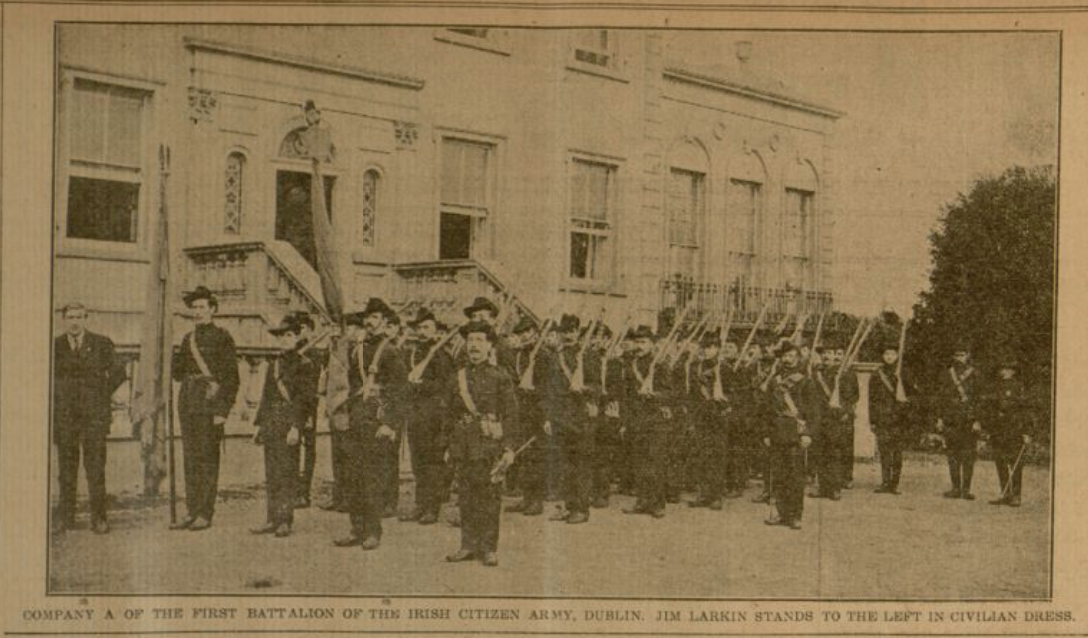

The ICA uniform was dark green with a slouched hat and badge in the shape of the Red Hand of Ulster.Michael McNally, Peter Dennis, ''Easter Rising 1916: Birth of the Irish Republic'', Osprey Publishin

The ICA uniform was dark green with a slouched hat and badge in the shape of the Red Hand of Ulster.Michael McNally, Peter Dennis, ''Easter Rising 1916: Birth of the Irish Republic'', Osprey Publishin

As many members could not afford a uniform, they wore a blue armband, with officers wearing red ones. Their banner was the Starry Plough (flag), Starry Plough. James Connolly said the significance of the banner was that a free Ireland would control its own destiny from the plough to the stars. The symbolism of the flag was evident in its earliest inception of a plough with a sword as its blade. Taking inspiration from the Bible, and following the internationalist aspect of socialism, it reflected the belief that war would be redundant with the rise of the

The Irish Citizen Army : Labour clenches its fist!

{{Authority control 1913 establishments in Ireland 1947 disestablishments in Ireland Easter Rising Irish republican militant groups Left-wing militant groups in the United Kingdom Paramilitary organisations based in Ireland

The Irish Citizen Army (), or ICA, was a

The Irish Citizen Army (), or ICA, was a paramilitary

A paramilitary is a military that is not a part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. The Oxford English Dictionary traces the use of the term "paramilitary" as far back as 1934.

Overview

Though a paramilitary is, by definiti ...

group first formed in Dublin to defend the picket lines and street demonstrations of the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (ITGWU) against the police during the Great Dublin Lockout of 1913. Subsequently, under the leadership of James Connolly

James Connolly (; 5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was a Scottish people, Scottish-born Irish republicanism, Irish republican, socialist, and trade union leader, executed for his part in the Easter Rising, 1916 Easter Rising against British rule i ...

, the ICA participated in the Irish Republican

Irish republicanism () is the political movement for an Irish republic, void of any British rule. Throughout its centuries of existence, it has encompassed various tactics and identities, simultaneously elective and militant and has been both w ...

insurrection of Easter 1916.

Following the Easter Rising, the death of James Connolly and the departure of Jim Larkin, the ICA largely sidelined itself during the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence (), also known as the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922), Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and Unite ...

by choosing to only offer material support to the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various Resistance movement, resistance organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dominantly Catholic and dedicated to anti-imperiali ...

and not become directly involved itself. Following the ICA's declaration in July 1919 that members could not be simultaneously members of both the ICA and the IRA, combined with the ICA's military inactivity, there was a steady stream of desertion from the ICA. During the Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War (; 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923) was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United Kingdom but within the British Emp ...

, the ICA declared itself "neutral", resulting in further departures from the organisation.

The ICA ceased to hold any military importance from 1920 until 1934 when the newly formed Republican Congress attempted to revive it. However, when the republican-socialist alliance split and collapsed over ideological in-fighting, so too did the ICA.

The Lockout of 1913

The Citizen Army arose out of the lockout and strike strike of the

The Citizen Army arose out of the lockout and strike strike of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union

The Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) was a trade union representing workers, initially mainly labourers, in Ireland.

History

The union was founded by James Larkin and James Fearon (trade unionist), James Fearon in January 1909 ...

(ITGWU) in 1913. Rejecting collective bargaining

Collective bargaining is a process of negotiation between employers and a group of employees aimed at agreements to regulate working salaries, working conditions, benefits, and other aspects of workers' compensation and labour rights, rights for ...

, Dublin's leading employer, William Martin Murphy

William Martin Murphy (6 January 1845 – 26 June 1919) was an Irish businessman, newspaper publisher and politician. A member of parliament (MP) representing Dublin from 1885 to 1892, he was dubbed "William ''Murder'' Murphy" among the Iris ...

, locked out union members on 19 August 1913. The ITGWU's leader and founder, James Larkin, responded by calling out on strike Murphy's employees in Dublin United Tramway Company. Other employers, encouraged by Murphy, retaliated by following his example. The conflict eventually escalated to involve 400 employers and 25,000 workers, and the Dublin Metropolitan Police

The Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) was the police force of Dublin in History of Ireland (1801–1923), British-controlled Ireland from 1836 to 1922 and then the Irish Free State until 1925, when it was absorbed into the new state's Garda SĂo ...

engaged in increasingly violent efforts to break picket lines and suppress protest. With Larkin in prison, his deputy James Connolly

James Connolly (; 5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was a Scottish people, Scottish-born Irish republicanism, Irish republican, socialist, and trade union leader, executed for his part in the Easter Rising, 1916 Easter Rising against British rule i ...

took up the offer the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

veteran Jack White

John Anthony White (; born July 9, 1975) is an American musician who achieved international fame as the guitarist and lead singer of the rock duo the White Stripes. As the White Stripes disbanded, he sought success with his solo career, subse ...

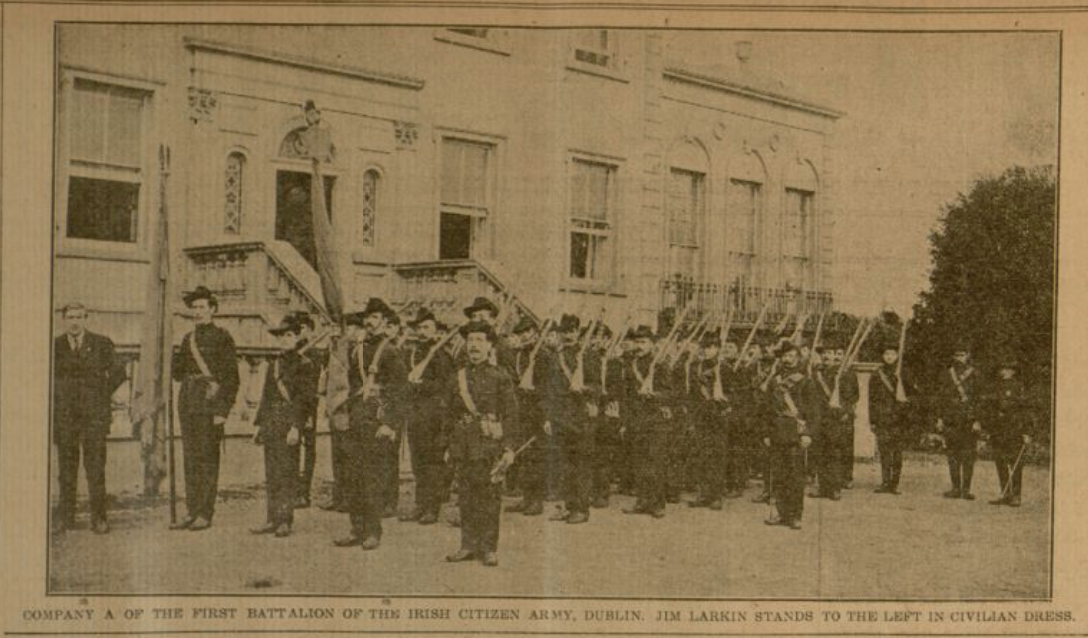

to drill union men as a workers' defence corps, a "Citizen Army". Calling for four battalions of trained men with corporals and sergeants, Connolly helped in the organisation to which Markievicz contributed her Fianna Éireann nationalist youth, and in November 1913 the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) was born.

This strike caused most of Dublin to come to an economic standstill; it was marked by vicious rioting between the strikers and the Dublin Metropolitan Police

The Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) was the police force of Dublin in History of Ireland (1801–1923), British-controlled Ireland from 1836 to 1922 and then the Irish Free State until 1925, when it was absorbed into the new state's Garda SĂo ...

, particularly at a rally on O'Connell Street

O'Connell Street () is a street in the centre of Dublin, Ireland, running north from the River Liffey. It connects the O'Connell Bridge to the south with Parnell Street to the north and is roughly split into two sections bisected by Henry ...

on 31 August, in which two men were beaten to death and about 500 more injured. Another striker was later fatally wounded by a ricochet from a revolver fired by a strike-breaker.Yeates, P Lockout: Dublin 1913, Gill and Macmillan, Dublin, 2000, Pages 497-8 The violence at union rallies during the strike prompted Larkin to call for a workers' militia to be formed to protect themselves against the police. The Citizen Army for the duration of the lock-out was armed with hurleys (sticks used in hurling

Hurling (, ') is an outdoor Team sport, team game of ancient Gaelic culture, Gaelic Irish origin, played by men and women. One of Ireland's native Gaelic games, it shares a number of features with Gaelic football, such as the field and goa ...

, a traditional Irish sport) and bats to protect workers' demonstrations from the police. Jack White

John Anthony White (; born July 9, 1975) is an American musician who achieved international fame as the guitarist and lead singer of the rock duo the White Stripes. As the White Stripes disbanded, he sought success with his solo career, subse ...

, a former captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

in the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

, volunteered to train this army and offered ÂŁ50 towards the cost of shoes to workers so that they could train. In addition to its role as a self-defence organisation, the Army, which was drilled in Croydon Park in Fairview by White, provided a diversion for workers unemployed and idle during the dispute. After a six-month standoff, the workers returned to work hungry and defeated in January 1914. The original purpose of the ICA was over, but it would soon be totally transformed.

Re-organisation

The Irish Citizen Army underwent a complete reorganisation in 1914.

In March of that year, police attacked a demonstration of the Citizen Army and arrested Jack White, its commander. Seán O'Casey, the playwright, then suggested that the ICA needed a more formal organisation. He wrote a constitution, stating the Army's principles as follows: "the ownership of Ireland, moral and material, is vested of right in the people of Ireland" and to "sink all difference of birth property and creed under the common name of the Irish people".

Larkin insisted that all members also be members of a trade union, if eligible. In mid-1914, White resigned as ICA commander in order to join the mainstream nationalist

The Irish Citizen Army underwent a complete reorganisation in 1914.

In March of that year, police attacked a demonstration of the Citizen Army and arrested Jack White, its commander. Seán O'Casey, the playwright, then suggested that the ICA needed a more formal organisation. He wrote a constitution, stating the Army's principles as follows: "the ownership of Ireland, moral and material, is vested of right in the people of Ireland" and to "sink all difference of birth property and creed under the common name of the Irish people".

Larkin insisted that all members also be members of a trade union, if eligible. In mid-1914, White resigned as ICA commander in order to join the mainstream nationalist Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers (), also known as the Irish Volunteer Force or the Irish Volunteer Army, was a paramilitary organisation established in 1913 by nationalists and republicans in Ireland. It was ostensibly formed in response to the format ...

, and Larkin assumed direct command.

The ICA armed itself with Mauser

Mauser, originally the Königlich Württembergische Gewehrfabrik, was a German arms manufacturer. Their line of bolt-action rifles and semi-automatic pistols was produced beginning in the 1870s for the German armed forces. In the late 19th and ...

rifles, bought from Germany by the Irish Volunteers and smuggled into Ireland at Howth

Howth ( ; ; ) is a peninsular village and outer suburb of Dublin, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The district as a whole occupies the greater part of the peninsula of Howth Head, which forms the northern boundary of Dublin Bay, and includes the ...

in July 1914. This organisation was one of the first to offer equal membership to both men and women, and trained them both in the use of weapons. The army's headquarters was the ITGWU union building, Liberty Hall, and membership was almost entirely Dublin-based. However, Connolly also set up branches in Tralee

Tralee ( ; , ; formerly , meaning 'strand of the River Lee') is the county town of County Kerry in the south-west of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The town is on the northern side of the neck of the Dingle Peninsula, and is the largest town in ...

and Killarney

Killarney ( ; , meaning 'church of sloes') is a town in County Kerry, southwestern Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The town is on the northeastern shore of Lough Leane, part of Killarney National Park, and is home to St Mary's Cathedral, Killar ...

in County Kerry

County Kerry () is a Counties of Ireland, county on the southwest coast of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. It is bordered by two other countie ...

. Tom Clarke called a meeting of all the separatist groups in Dublin on 9 September 1914 to assist a German invasion of Ireland, and prevent the police disarming the Volunteers.Townshend, p.93. An intellectual dispute broke out within the ranks of the ICA between Liam O'Briain and the ICA's military commander, Michael Mallin, who thought that the former's plan for an integrated movement was totally unrealistic. O'Brian wanted to pursue a strategy without the Dublin brigade being "cooped up in the city". Mallin told him that, on the contrary, the whole strategy was to focus on the central objective on and around Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle () is a major Government of Ireland, Irish government complex, conference centre, and tourist attraction. It is located off Dame Street in central Dublin.

It is a former motte-and-bailey castle and was chosen for its position at ...

. Little did they know that the Castle and the barracks behind possessed no more than a skeleton garrison, and could have been taken by a token force.

James Larkin left Ireland for America in October 1914, leaving the Citizen Army under the command of James Connolly. Whereas during the Lockout the ICA had been a workers' self-defence militia, Connolly conceived of it as a revolutionary organisation dedicated to the creation of an Irish socialist republic. He had served in the British Army in his youth, and knew something about military tactics and discipline.

Other active members in the early days included the Secretary to the council, Seán O'Casey, who tried to have Constance Markievicz

Constance Georgine Markievicz ( ; ' Gore-Booth; 4 February 1868 – 15 July 1927), also known as Countess Markievicz and Madame Markievicz, was an Irish politician, revolutionary, nationalist, suffragist, and socialist who was the first woman ...

expelled for her close associations with the Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers (), also known as the Irish Volunteer Force or the Irish Volunteer Army, was a paramilitary organisation established in 1913 by nationalists and republicans in Ireland. It was ostensibly formed in response to the format ...

. He described the formation of the nationalist force as "one of the most effective blows" that the ICA had received. Men who might have joined the ICA were now drilling—with the blessing of the Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

(IRB)—under a command that included employers who had stood with Murphy against those trying to "assert the first principles of Trade Unionism". When in the late summer of 1914, it became apparent that Connolly was gravitating towards the IRB, O'Casey and Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, vice-president, resigned from the ICA.

In May 1914, Jack White

John Anthony White (; born July 9, 1975) is an American musician who achieved international fame as the guitarist and lead singer of the rock duo the White Stripes. As the White Stripes disbanded, he sought success with his solo career, subse ...

had also withdrawn from ICA, replaced as chairman of the executive by Larkin, but it was to join Volunteers. Explaining that he had always "to link the Labour and National Causes as soon as they can be linked", White, who had clashed with O'Casey, insisted that the nationalist militia was an allied force. It was a move for which later, as a socialist, he was to express regret. What White failed to appreciate, according ICA veteran and trade unionist, Frank Robbins

Franklin Robbins (September 9, 1917 – November 28, 1994) was an American comic book and comic strip artist and writer, as well as a prominent painter whose work appeared in museums including the Whitney Museum of American Art, where one of his ...

, was that, despite the guiding presence of Connolly, the men he had drilled in Dublin, "while trade unionists, were not by any measure socialists".

The ICA was grossly under-funded. John Devoy

John Devoy (, ; 3 September 1842 – 29 September 1928) was an Irish republican Rebellion, rebel and journalist who owned and edited ''The Gaelic American'', a New York weekly newspaper, from 1903 to 1928.

Devoy dedicated over 60 year ...

, the prominent Irish-American member of IRB Fenians, believed the existence of "a land army on Irish soil" was the most important sign since the founding of the Gaelic League

(; historically known in English as the Gaelic League) is a social and cultural organisation which promotes the Irish language in Ireland and worldwide. The organisation was founded in 1893 with Douglas Hyde as its first president, when it eme ...

. James Connolly, a convinced Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

socialist and Irish Republican

Irish republicanism () is the political movement for an Irish republic, void of any British rule. Throughout its centuries of existence, it has encompassed various tactics and identities, simultaneously elective and militant and has been both w ...

, believed that achieving political change through physical force, in the tradition of the Fenians

The word ''Fenian'' () served as an umbrella term for the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and their affiliate in the United States, the Fenian Brotherhood. They were secret political organisations in the late 19th and early 20th centurie ...

, was legitimate. The ICA was the victim of small numbers, that shrank to only 200-300 persons, and fitful discipline.

In October 1915, armed ICA pickets patrolled a strike by dockers at Dublin port

Dublin Port () is the seaport of Dublin, Ireland, of both historical and contemporary economic importance. Approximately two-thirds of Ireland's port traffic travels via the port, which is by far the busiest on the island of Ireland.

Locatio ...

. Appalled by the participation of Irishmen in the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, which he regarded as an imperialist, capitalist conflict, Connolly began openly calling for insurrection in his newspaper, the ''Irish Worker''. When this was banned he opened another, the ''Worker's Republic''.

British authorities tolerated the open drilling and bearing of arms by the ICA, thinking that to clamp down on the organisation would provoke further unrest. A small group of IRB conspirators within the Irish Volunteers movement had started planning a rising. Worried that Connolly would embark on premature military action with the ICA, they approached him and inducted him into the IRB's Supreme Council to co-ordinate their preparations for the armed rebellion which became known as the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising (), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an ind ...

.

Easter Rising

On Monday, 24 April 1916, 220 members of the ICA (including 28 women) took part in the Easter Rising, alongside a much larger body of the Irish Volunteers. They helped occupy theGeneral Post Office

The General Post Office (GPO) was the state postal system and telecommunications carrier of the United Kingdom until 1969. Established in England in the 17th century, the GPO was a state monopoly covering the dispatch of items from a specific ...

(GPO) on O'Connell Street (then named Sackville Street), Dublin's main thoroughfare. Michael Mallin, Connolly's second-in-command, along with Kit Poole, Constance Markievicz and an ICA company, occupied St Stephen's Green

St Stephen's Green () is a garden square and public park located in the city centre of Dublin, Ireland. The current landscape of the park was designed by William Sheppard. It was officially re-opened to the public on Tuesday, 27 July 1880 by ...

. Another company under Sean Connolly took over City Hall

In local government, a city hall, town hall, civic centre (in the UK or Australia), guildhall, or municipal hall (in the Philippines) is the chief administrative building of a city, town, or other municipality. It usually houses the city o ...

and attacked Dublin Castle. Finally, a detachment occupied Harcourt Street railway station. ICA men were the first rebel casualties of Easter week, two of them being killed in an abortive attack on Dublin Castle. The confusion in the chain of command caused conflict with the Volunteers. Harry Colley and Harry Boland came out from their outposts in the Wicklow Chemical Manure Company's office 200 yards away, where they were under the command of an irascible officer, Vincent Poole; the post had been set up by James Connolly, without countermanding orders from affective Volunteers.

Sean Connolly, an ICA officer and Abbey Theatre

The Abbey Theatre (), also known as the National Theatre of Ireland () is a theatre in Dublin, Ireland. First opening to the public on 27 December 1904, and moved from its original building after a fire in 1951, it has remained active to the p ...

actor, was both the first rebel to kill a British soldier and the first to be killed. footnote 62

A total of eleven Citizen Army men were killed in action in the rising, five in the City Hall/Dublin castle area, five in St Stephen's Green and one in the GPO.

James Connolly was made commander of the rebel forces in Dublin during the Rising and issued orders to surrender after a week. He and Mallin were executed by British Army firing squad some weeks later. The surviving ICA members were interned, in English prisons or at Frongoch internment camp

Frongoch is a village located in Gwynedd, Wales. It lies close to the market town of Bala, on the A4212 road.

It was the home of the Frongoch internment camp, used to hold German prisoners-of-war during First World War, and then Irish ...

in Wales, for between nine and 12 months.

Inactivity during the War of Independence and Civil War

War of Independence

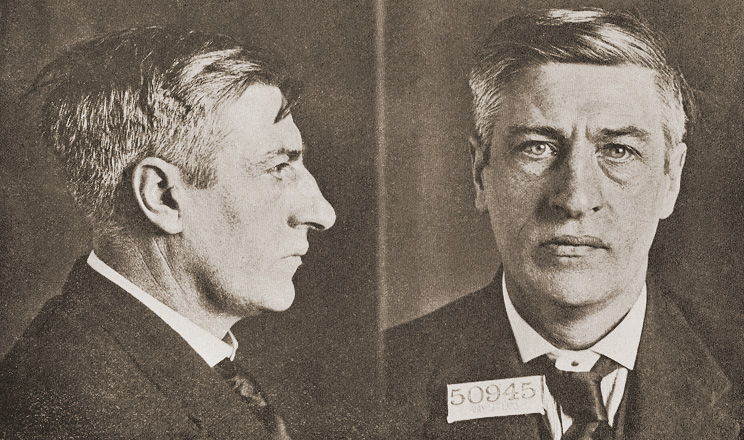

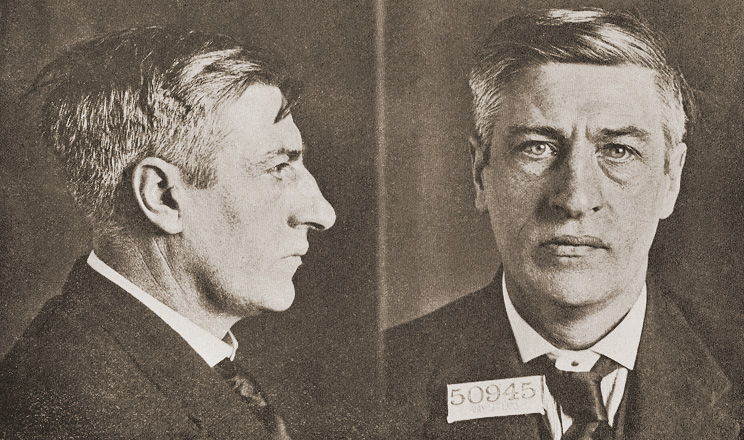

Following the Easter Rising, the ICA had lost most of their most dynamic and militant leaders. James Connolly and Michael Mallin had been executed, while Jim Larkin was in America and later imprisoned inSing Sing

Sing Sing Correctional Facility is a maximum-security prison for men operated by the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision in the village of Ossining (village), New York, Ossining, New York, United States. It is abou ...

from 1920 until 1923. The ICA was largely left in the hands of James O'Neill. By the time of the Irish War of Independence, there were never more than 250 people actively involved in the ICA, and these were mostly concentrated in Dublin city. By this stage, the ICA could not nor would not engage directly British forces in Ireland; Instead the organisation chose to operate as a support organisation to the IRA, provide weapons, medical aid and other material support. On one occasion ICA members stewarding a proscribed Connolly commemoration fired on police, wounding four of them. While at first the ICA was content to allow members to both in the IRA and ICA, in July 1919 they declared members could only be in one or the other. This caused much resentment with the ICA's own membership and resulted in a number of people choosing the IRA over the ICA.

In April 1919 the ICA choose to take no action in relation to the establishment of the Limerick Soviet, part of a wider wave of Irish soviets happening at the time. Internal frustrations with the ICA's inactivity began to boil over: In January 1920 members began to argue over its relationship to Sinn FĂ©in and the IRA. Member Michael Donnelly accused the ICA of now simply being a "tail" to Sinn FĂ©in and suggested that supporting the IRA was "illogical" because the IRA was no longer fighting for the same Republic the ICA sought. In response, leading ICA member Dick MacCormack accused Donnelly of seeking to break up the ICA. Infighting continued to grow as the months progressed: Members criticised Countess Markievicz, still a standing member of the ICA, for speaking at Sinn FĂ©in rallies. When Sean McLoughlin, a socialist who had fought in the Easter Rising, published a report to the Third International

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internation ...

containing criticisms of the ICA, the ICA responded by putting out a "warrant" for his "arrest". As 1920 continued, while the ICA continued to practice military drills, in practicality, it was beginning to operate more like a social club for members of Dublin's labour and socialists cliques than a paramilitary organisation, with members noting that as much time was being given to playing cards together, classes on socialism, and the operating of a Pipeband as anything else.

Civil War

Following the signing of theAnglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty (), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain an ...

, the ICA adopted a stance of "neutrality" between the pro and anti-treaty sides of now emerging Irish Civil War. In a view of a majority of the ICA, neither side was working towards a "Workers' Republic", which was the ICA's aim. Their views matched that of the mainstream labour movement such as the Labour Party, who campaigned for peace between both sides in the face of the civil war. However, what direction the ICA should move towards lead to ideological in-fighting, with different factions arguing in favour of following Jim Larkin, others supporting Roddy Connolly and his newly formed Communist Party of Ireland (a renamed version of his father's Socialist Party of Ireland), while others wanted to keep the ICA in line with the mainstream Labour Party.

In the end, a majority choose to stand by the Labour Party and to campaign for peace between the Pro and Anti Treaty sides. This led to many defections from the ICA, with a majority joining the Anti-Treaty IRA while a minority joined the newly formed National Army of the Free State.

Post Revolutionary Period

In the 1920s and 1930s, the ICA was kept alive by veterans such as Seamus McGowan, Dick McCormack and Frank Purcell, though largely as an old comrades association by veterans of the Easter Rising. Uniformed Citizen Army men provided a guard of honour at Constance Markievicz's funeral in 1927. In 1929 Roddy Connolly and Helena Molony encouraged the formation of a "Workers' Defence Corps" that was to be a "New ICA"—an idea that British Intelligence was also associating with Jack White. However, this new group was to comprise both ICA veterans and the remnants of the anti-treaty IRA, who were still a much larger group than the ICA, and thus out of fear of being simply absorbed and annexed by the IRA, the ICA passed on the idea.Brief revival under the Republican Congress

In 1934, spurred by events in Spain,Peadar O'Donnell

Peadar O'Donnell (; 22 February 1893 – 13 May 1986) was one of the foremost radicals of 20th-century Ireland. O'Donnell became prominent as an Irish republican, socialist politician and writer.

Early life

Peadar O'Donnell was born into an I ...

and other left-wing republicans left the IRA and founded the Republican Congress. For a brief time, they revived the ICA as a paramilitary force, intended to be an armed wing for their new movement. According to Brian Hanley's history of the IRA, the revived Citizen Army had 300 or so members around the country in 1935. Dynamic new figures such as Frank Ryan and Michael Price made the move into the ICA and helped give it new strength. The ICA and the Republican Congress came up with a new framework for revolution in Ireland, the need for a "triple alliance". They believed the path to success lay in three forces united in the name of the workers: A paramilitary force (the ICA), A Socialist Party (The Republican Congress) and One Big Union (in this case, ITGWU).

However, the Congress itself split in September 1934, which led to a corresponding split in the ICA. One fraction, which had left the Congress, were led by Michael Price and Nora Connolly O'Brien, while the opposing faction led by O'Donnell and Roddy Connolly were loyal to those who stayed.

The ICA's last public appearance was to accompany the funeral procession of union leader and ICA founding figure James Larkin in Dublin in 1947.

Name used during the Troubles

In December 1974 when the INLA was at its founding meeting in Dublin while deciding what to name the new paramilitary organization the name "Irish Citizens Army" had been suggested, this it was hoped would make the new group seem like the true inheritors of James Connolly's legacy & ideology, but it was ultimately passed on as a group had used the name to carry out several sectarian attacks in Belfast during the early 1970s.Uniforms and banners

As many members could not afford a uniform, they wore a blue armband, with officers wearing red ones. Their banner was the Starry Plough (flag), Starry Plough. James Connolly said the significance of the banner was that a free Ireland would control its own destiny from the plough to the stars. The symbolism of the flag was evident in its earliest inception of a plough with a sword as its blade. Taking inspiration from the Bible, and following the internationalist aspect of socialism, it reflected the belief that war would be redundant with the rise of the

Socialist International

The Socialist International (SI) is a political international or worldwide organisation of political parties which seek to establish democratic socialism, consisting mostly of Social democracy, social democratic political parties and Labour mov ...

. This was flown by the ICA during the Rising of 1916. The design changed during the 1930s to that of the blue banner on the right, which was designed by members of the Republican Congress, and was adopted as the emblem of the Irish Labour movement, including the Irish Labour Party. It is also claimed by Irish republicans, and has been carried alongside the Irish tricolour and Irish provincial flags at Official IRA

The Official Irish Republican Army or Official IRA (OIRA; ) was an Irish republican paramilitary group whose goal was to remove Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom and create a " workers' republic" encompassing all of Ireland. It emerg ...

, Provisional IRA

The Provisional Irish Republican Army (Provisional IRA), officially known as the Irish Republican Army (IRA; ) and informally known as the Provos, was an Irish republican paramilitary force that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland ...

, Irish National Liberation Army

The Irish National Liberation Army (INLA, ) is an Irish republicanism, Irish republican Socialism, socialist paramilitary group formed on 8 December 1974, during the 30-year period of conflict known as "the Troubles". The group seeks to remove ...

(INLA), Irish People's Liberation Organisation

The Irish People's Liberation Organisation was a small Irish socialist republican paramilitary organisation formed in 1986 by disaffected and expelled members of the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA), whose factions coalesced in the after ...

(IPLO) and Continuity IRA

The Continuity Irish Republican Army (Continuity IRA or CIRA), styling itself as the Irish Republican Army (), is an Irish republican paramilitary group that aims to bring about a united Ireland. It claims to be a direct continuation of the or ...

rallies and marches.

The banner, and alternative versions of it, is also used by Anti-Imperialist Action Ireland the Workers' Party

Workers' Party is a name used by several political parties throughout the world. The name has been used by both organisations on the left and right of the political spectrum. It is currently used by followers of Marxism, Marxism–Leninism, Maoism ...

, Republican Sinn FĂ©in, Connolly Youth Movement, Labour Youth

Labour Youth is the youth wing of the Labour Party of Ireland. Membership is open to those aged from 16 to 30 years old.

History 1979–2000

Labour Youth succeeded the Young Labour League as a full section of the Labour Party in 1979, unde ...

, Ă“gra Shinn FĂ©in, the Irish Republican Socialist Party, the Republican Socialist Youth Movement and the Republican Socialist Collective (IPLO's political wing).

Gallery

References

Bibliography

* Anderson, W.K., James Connolly and the Irish Left (Dublin 1994). . * Fox, R.M., The History of the Irish Citizen Army (Dublin 1943) * Greaves, C. Desmond, Life and Times of James Connolly, (London 1972) * Haswell, Jock, ''Citizen Armies'' (London 1973) * Hart, Peter, ''The IRA at War 1916-1923'' (Oxford 2003) * Hayes-McCoy, G.A., 'A Military History of the 1916 Rising', in K.B.Nowlan (ed.), ''The Making of 1916. Studies in the History of the Rising'' (Dublin 1969) * Mac An Mháistir, DaithĂ, The Irish Citizen Army: The World's First Working-Class Army Third Edition (Dublin 2023) * Martin, F.X., ''Leaders and Men of the Easter Rising: Dublin 1916'' (London 1967) * O'Casey, Sean (as P. Ă“ Cathasaigh) Story of the Irish Citizen Army (Dublin 1919) * O'Drisceoil, Donal, ''Peadar O'Donnell'' (Cork 2000) * Perry, Ciaran, ''The Irish Citizen Army, Labour clenches its fist!'' * Phelan, Mark, 'World War I and the Legacy of the Dublin Lockout, 1914-1916', in ''Éire''-Ireland (Winter, 2016) * Robbins, Frank. 1978. Under the Starry Plough: Recollections of the Irish Citizen Army. Dublin: The Academy Press. .External links

The Irish Citizen Army : Labour clenches its fist!

{{Authority control 1913 establishments in Ireland 1947 disestablishments in Ireland Easter Rising Irish republican militant groups Left-wing militant groups in the United Kingdom Paramilitary organisations based in Ireland