Intraplate Volcanism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Intraplate volcanism is

A

A

The chemical and isotopic composition of basalts found at hotspots differs subtly from mid-ocean-ridge basalts. These basalts, also called ocean island basalts (OIBs), are analysed in their radiogenic and stable isotope compositions. In radiogenic isotope systems the originally subducted material creates diverging trends, termed mantle components. Identified mantle components are DMM (depleted mid-ocean ridge basalt (MORB) mantle), HIMU (high U/Pb-ratio mantle), EM1 (enriched mantle 1), EM2 (enriched mantle 2) and FOZO (focus zone). This geochemical signature arises from the mixing of near-surface materials such as subducted slabs and continental sediments, in the mantle source. There are two competing interpretations for this. In the context of mantle plumes, the near-surface material is postulated to have been transported down to the core-mantle boundary by subducting slabs, and to have been transported back up to the surface by plumes. In the context of the Plate hypothesis, subducted material is mostly re-circulated in the shallow mantle and tapped from there by volcanoes.

Stable isotopes like Fe are used to track processes that the uprising material experiences during melting.

The processing of oceanic crust, lithosphere, and sediment through a subduction zone decouples the water-soluble trace elements (e.g., K, Rb, Th) from the immobile trace elements (e.g., Ti, Nb, Ta), concentrating the immobile elements in the oceanic slab (the water-soluble elements are added to the crust in island arc volcanoes).

The chemical and isotopic composition of basalts found at hotspots differs subtly from mid-ocean-ridge basalts. These basalts, also called ocean island basalts (OIBs), are analysed in their radiogenic and stable isotope compositions. In radiogenic isotope systems the originally subducted material creates diverging trends, termed mantle components. Identified mantle components are DMM (depleted mid-ocean ridge basalt (MORB) mantle), HIMU (high U/Pb-ratio mantle), EM1 (enriched mantle 1), EM2 (enriched mantle 2) and FOZO (focus zone). This geochemical signature arises from the mixing of near-surface materials such as subducted slabs and continental sediments, in the mantle source. There are two competing interpretations for this. In the context of mantle plumes, the near-surface material is postulated to have been transported down to the core-mantle boundary by subducting slabs, and to have been transported back up to the surface by plumes. In the context of the Plate hypothesis, subducted material is mostly re-circulated in the shallow mantle and tapped from there by volcanoes.

Stable isotopes like Fe are used to track processes that the uprising material experiences during melting.

The processing of oceanic crust, lithosphere, and sediment through a subduction zone decouples the water-soluble trace elements (e.g., K, Rb, Th) from the immobile trace elements (e.g., Ti, Nb, Ta), concentrating the immobile elements in the oceanic slab (the water-soluble elements are added to the crust in island arc volcanoes).

The most prominent thermal contrast known to exist in the deep (1000 km) mantle is at the core-mantle boundary at 2900 km. Mantle plumes were originally postulated to rise from this layer because the "hot spots" that are assumed to be their surface expression were thought to be fixed relative to one another. This required that plumes were sourced from beneath the shallow asthenosphere that is thought to be flowing rapidly in response to motion of the overlying tectonic plates. There is no other known major thermal boundary layer in the deep Earth, and so the core-mantle boundary was the only candidate.

The base of the mantle is known as the D″ layer, a seismological subdivision of the Earth. It appears to be compositionally distinct from the overlying mantle, and may contain partial melt.

Two very broad,

The most prominent thermal contrast known to exist in the deep (1000 km) mantle is at the core-mantle boundary at 2900 km. Mantle plumes were originally postulated to rise from this layer because the "hot spots" that are assumed to be their surface expression were thought to be fixed relative to one another. This required that plumes were sourced from beneath the shallow asthenosphere that is thought to be flowing rapidly in response to motion of the overlying tectonic plates. There is no other known major thermal boundary layer in the deep Earth, and so the core-mantle boundary was the only candidate.

The base of the mantle is known as the D″ layer, a seismological subdivision of the Earth. It appears to be compositionally distinct from the overlying mantle, and may contain partial melt.

Two very broad,

The plume hypothesis has been tested by looking for the geophysical anomalies predicted to be associated with them. These include thermal, seismic, and elevation anomalies. Thermal anomalies are inherent in the term "hotspot". They can be measured in numerous different ways, including surface heat flow, petrology, and seismology. Thermal anomalies produce anomalies in the speeds of seismic waves, but unfortunately so do composition and partial melt. As a result, wave speeds cannot be used simply and directly to measure temperature, but more sophisticated approaches must be taken.

Seismic anomalies are identified by mapping variations in wave speed as seismic waves travel through Earth. A hot mantle plume is predicted to have lower seismic wave speeds compared with similar material at a lower temperature. Mantle material containing a trace of partial melt (e.g., as a result of it having a lower melting point), or being richer in Fe, also has a lower seismic wave speed and those effects are stronger than temperature. Thus, although unusually low wave speeds have been taken to indicate anomalously hot mantle beneath "hot spots", this interpretation is ambiguous. The most commonly cited seismic wave-speed images that are used to look for variations in regions where plumes have been proposed come from seismic tomography. This method involves using a network of seismometers to construct three-dimensional images of the variation in seismic wave speed throughout the mantle.

The plume hypothesis has been tested by looking for the geophysical anomalies predicted to be associated with them. These include thermal, seismic, and elevation anomalies. Thermal anomalies are inherent in the term "hotspot". They can be measured in numerous different ways, including surface heat flow, petrology, and seismology. Thermal anomalies produce anomalies in the speeds of seismic waves, but unfortunately so do composition and partial melt. As a result, wave speeds cannot be used simply and directly to measure temperature, but more sophisticated approaches must be taken.

Seismic anomalies are identified by mapping variations in wave speed as seismic waves travel through Earth. A hot mantle plume is predicted to have lower seismic wave speeds compared with similar material at a lower temperature. Mantle material containing a trace of partial melt (e.g., as a result of it having a lower melting point), or being richer in Fe, also has a lower seismic wave speed and those effects are stronger than temperature. Thus, although unusually low wave speeds have been taken to indicate anomalously hot mantle beneath "hot spots", this interpretation is ambiguous. The most commonly cited seismic wave-speed images that are used to look for variations in regions where plumes have been proposed come from seismic tomography. This method involves using a network of seismometers to construct three-dimensional images of the variation in seismic wave speed throughout the mantle.

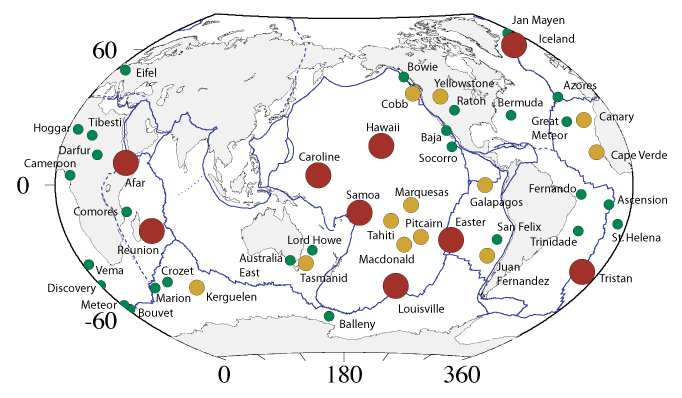

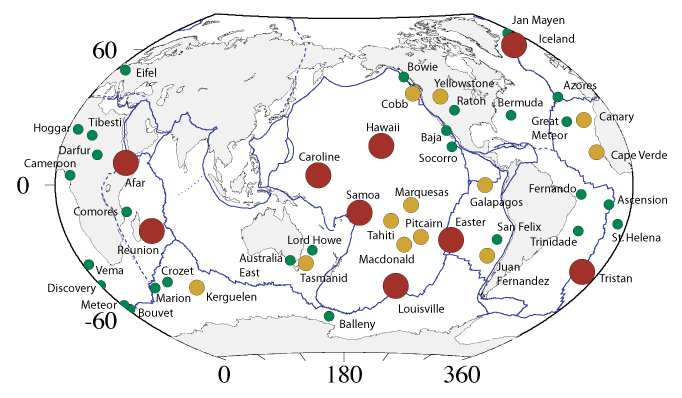

Many different localities have been suggested to be underlain by mantle plumes, and scientists cannot agree on a definitive list. Some scientists suggest that several tens of plumes exist, whereas others suggest that there are none. The theory was really inspired by the Hawaiian volcano system. Hawaii is a large volcanic edifice in the center of the Pacific Ocean, far from any plate boundaries. Its regular, time-progressive chain of islands and seamounts superficially fits the plume theory well. However, it is almost unique on Earth, as nothing as extreme exists anywhere else. The second strongest candidate for a plume location is often quoted to be Iceland, but according to opponents of the plume hypothesis its massive nature can be explained by plate tectonic forces along the mid-Atlantic spreading center.

Mantle plumes have been suggested as the source for

Many different localities have been suggested to be underlain by mantle plumes, and scientists cannot agree on a definitive list. Some scientists suggest that several tens of plumes exist, whereas others suggest that there are none. The theory was really inspired by the Hawaiian volcano system. Hawaii is a large volcanic edifice in the center of the Pacific Ocean, far from any plate boundaries. Its regular, time-progressive chain of islands and seamounts superficially fits the plume theory well. However, it is almost unique on Earth, as nothing as extreme exists anywhere else. The second strongest candidate for a plume location is often quoted to be Iceland, but according to opponents of the plume hypothesis its massive nature can be explained by plate tectonic forces along the mid-Atlantic spreading center.

Mantle plumes have been suggested as the source for

The plate theory attributes all

The plate theory attributes all  Beginning in the early 2000s, dissatisfaction with the state of the evidence for mantle plumes and the proliferation of

Beginning in the early 2000s, dissatisfaction with the state of the evidence for mantle plumes and the proliferation of

mantleplumes.org

a major international forum with contributions from geoscientists working in a wide variety of specialties.

Iceland is a 1 km high, 450x300 km basaltic shield on the mid-ocean ridge in the northeast Atlantic Ocean. It comprises over 100 active or extinct volcanoes and has been extensively studied by Earth scientists for several decades.

Iceland must be understood in the context of the broader structure and tectonic history of the northeast Atlantic. The northeast Atlantic formed in the early

Iceland is a 1 km high, 450x300 km basaltic shield on the mid-ocean ridge in the northeast Atlantic Ocean. It comprises over 100 active or extinct volcanoes and has been extensively studied by Earth scientists for several decades.

Iceland must be understood in the context of the broader structure and tectonic history of the northeast Atlantic. The northeast Atlantic formed in the early

Yellowstone and the Eastern Snake River Plain to the west comprise a belt of large, silicic caldera volcanoes that get progressively younger to the east, culminating in the currently active

Yellowstone and the Eastern Snake River Plain to the west comprise a belt of large, silicic caldera volcanoes that get progressively younger to the east, culminating in the currently active

Seismic-tomography image of Yellowstone mantle plumeLarge Igneous Provinces Commissionmantleplumes.org - mantle-plume skeptic website managed and maintained by Gillian R. Foulger

Geodynamics Plate tectonics Structure of the Earth Volcanism {{DEFAULTSORT:Intraplate volcanism

volcanism

Volcanism, vulcanism or volcanicity is the phenomenon of eruption of molten rock (magma) onto the Earth#Surface, surface of the Earth or a solid-surface planet or moon, where lava, pyroclastics, and volcanic gases erupt through a break in the su ...

that takes place away from the margins of tectonic plates

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large t ...

. Most volcanic activity takes place on plate margins, and there is broad consensus among geologists that this activity is explained well by the theory of plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (from the la, label= Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large t ...

. However, the origins of volcanic activity within plates remains controversial.

Mechanisms

Mechanisms that have been proposed to explain intraplate volcanism include mantle plumes; non-rigid motion within tectonic plates (the plate model); andimpact event

An impact event is a collision between astronomical objects causing measurable effects. Impact events have physical consequences and have been found to regularly occur in planetary systems, though the most frequent involve asteroids, comets or ...

s. It is likely that different mechanisms accounts for different cases of interplate volcanism.

Plume model

mantle plume

A mantle plume is a proposed mechanism of convection within the Earth's mantle, hypothesized to explain anomalous volcanism. Because the plume head partially melts on reaching shallow depths, a plume is often invoked as the cause of volcanic hot ...

is a proposed mechanism of convection

Convection is single or multiphase fluid flow that occurs spontaneously due to the combined effects of material property heterogeneity and body forces on a fluid, most commonly density and gravity (see buoyancy). When the cause of the c ...

of abnormally hot rock within the Earth's mantle

Earth's mantle is a layer of silicate rock between the crust and the outer core. It has a mass of 4.01 × 1024 kg and thus makes up 67% of the mass of Earth. It has a thickness of making up about 84% of Earth's volume. It is predominantly so ...

. Because the plume head partly melts on reaching shallow depths, a plume is often invoked as the cause of volcanic hotspot

Hotspot, Hot Spot or Hot spot may refer to:

Places

* Hot Spot, Kentucky, a community in the United States

Arts, entertainment, and media Fictional entities

* Hot Spot (comics), a name for the DC Comics character Isaiah Crockett

* Hot Spot (Tra ...

s, such as Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only ...

or Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

, and large igneous province

A large igneous province (LIP) is an extremely large accumulation of igneous rocks, including intrusive (sills, dikes) and extrusive (lava flows, tephra deposits), arising when magma travels through the crust towards the surface. The formation ...

s such as the Deccan

The large Deccan Plateau in southern India is located between the Western Ghats and the Eastern Ghats, and is loosely defined as the peninsular region between these ranges that is south of the Narmada river. To the north, it is bounded by t ...

and Siberian traps

The Siberian Traps (russian: Сибирские траппы, Sibirskiye trappy) is a large region of volcanic rock, known as a large igneous province, in Siberia, Russia. The massive eruptive event that formed the traps is one of the large ...

. Some such volcanic regions lie far from tectonic plate boundaries

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large ...

, while others represent unusually large-volume volcanism

Volcanism, vulcanism or volcanicity is the phenomenon of eruption of molten rock (magma) onto the Earth#Surface, surface of the Earth or a solid-surface planet or moon, where lava, pyroclastics, and volcanic gases erupt through a break in the su ...

near plate boundaries.

The hypothesis

A hypothesis (plural hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. For a hypothesis to be a scientific hypothesis, the scientific method requires that one can testable, test it. Scientists generally base scientific hypotheses on prev ...

of mantle plumes has required progressive hypothesis-elaboration leading to variant propositions such as mini-plumes and pulsing plumes.

Concepts

Mantle plumes were first proposed byJ. Tuzo Wilson

John Tuzo Wilson (October 24, 1908 – April 15, 1993) was a Canadian geophysicist and geologist who achieved worldwide acclaim for his contributions to the theory of plate tectonics.

''Plate tectonics'' is the scientific theory that the rigid ...

in 1963 and further developed by W. Jason Morgan in 1971. A mantle plume is posited to exist where hot rock nucleates at the core-mantle boundary and rises through the Earth's mantle becoming a diapir

A diapir (; , ) is a type of igneous intrusion in which a more mobile and ductily deformable material is forced into brittle overlying rocks. Depending on the tectonic environment, diapirs can range from idealized mushroom-shaped Rayleigh– ...

in the Earth's crust

Earth's crust is Earth's thin outer shell of rock, referring to less than 1% of Earth's radius and volume. It is the top component of the lithosphere, a division of Earth's layers that includes the crust and the upper part of the mantle. The ...

. In particular, the concept that mantle plumes are fixed relative to one another, and anchored at the core-mantle boundary, would provide a natural explanation for the time-progressive chains of older volcanoes seen extending out from some such hot spots, such as the Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain

The Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain is a mostly undersea mountain range in the Pacific Ocean that reaches above sea level in Hawaii. It is composed of the Hawaiian ridge, consisting of the islands of the Hawaiian chain northwest to Kure Atoll, ...

. However, paleomagnetic

Paleomagnetism (or palaeomagnetismsee ), is the study of magnetic fields recorded in rocks, sediment, or archeological materials. Geophysicists who specialize in paleomagnetism are called ''paleomagnetists.''

Certain magnetic minerals in rocks ...

data show that mantle plumes can be associated with Large Low Shear Velocity Provinces (LLSVPs) and do move.

Two largely independent convective processes are proposed:

* the broad convective flow associated with plate tectonics, driven primarily by the sinking of cold plates of lithosphere

A lithosphere () is the rigid, outermost rocky shell of a terrestrial planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust and the portion of the upper mantle that behaves elastically on time scales of up to thousands of years ...

back into the mantle asthenosphere

The asthenosphere () is the mechanically weak and ductile region of the upper mantle of Earth. It lies below the lithosphere, at a depth between ~ below the surface, and extends as deep as . However, the lower boundary of the asthenosphere is ...

* the mantle plume, driven by heat exchange across the core-mantle boundary carrying heat upward in a narrow, rising column, and postulated to be independent of plate motions.

The plume hypothesis was studied using laboratory experiments conducted in small fluid-filled tanks in the early 1970s. Thermal or compositional fluid-dynamical plumes produced in that way were presented as model

A model is an informative representation of an object, person or system. The term originally denoted the plans of a building in late 16th-century English, and derived via French and Italian ultimately from Latin ''modulus'', a measure.

Models c ...

s for the much larger postulated mantle plumes. Based on these experiments, mantle plumes are now postulated to comprise two parts: a long thin conduit connecting the top of the plume to its base, and a bulbous head that expands in size as the plume rises. The entire structure is considered to resemble a mushroom. The bulbous head of thermal plumes forms because hot material moves upward through the conduit faster than the plume itself rises through its surroundings. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, experiments with thermal models showed that as the bulbous head expands it may entrain some of the adjacent mantle into the head.

The sizes and occurrence of mushroom mantle plumes can be predicted easily by transient instability theory developed by Tan and Thorpe. The theory predicts mushroom shaped mantle plumes with heads of about 2000 km diameter that have a critical time of about 830 Myr for a core mantle heat flux

Heat flux or thermal flux, sometimes also referred to as ''heat flux density'', heat-flow density or ''heat flow rate intensity'' is a flow of energy

In physics, energy (from Ancient Greek: ἐνέργεια, ''enérgeia'', “activity ...

of 20 mW/m2, while the cycle time is about 2 Gyr. The number of mantle plumes is predicted to be about 17.

When a plume head encounters the base of the lithosphere, it is expected to flatten out against this barrier and to undergo widespread decompression melting to form large volumes of basalt magma. It may then erupt onto the surface. Numerical modelling predicts that melting and eruption will take place over several million years. These eruptions have been linked to flood basalt

A flood basalt (or plateau basalt) is the result of a giant volcanic eruption or series of eruptions that covers large stretches of land or the ocean floor with basalt lava. Many flood basalts have been attributed to the onset of a hotspot reac ...

s, although many of those erupt over much shorter time scales (less than 1 million years). Examples include the Deccan traps

The Deccan Traps is a large igneous province of west-central India (17–24°N, 73–74°E). It is one of the largest volcanic features on Earth, taking the form of a large shield volcano. It consists of numerous layers of solidified flood ...

in India, the Siberian traps

The Siberian Traps (russian: Сибирские траппы, Sibirskiye trappy) is a large region of volcanic rock, known as a large igneous province, in Siberia, Russia. The massive eruptive event that formed the traps is one of the large ...

of Asia, the Karoo-Ferrar

The Karoo and Ferrar Large Igneous Provinces (LIPs) are two large igneous provinces in Southern Africa and Antarctica respectively, collectively known as the Karoo-Ferrar, Gondwana,E.g. or Southeast African LIP, associated with the initial break-u ...

basalts/dolerites in South Africa and Antarctica, the Paraná and Etendeka traps

The Paraná-Etendeka traps (or Paraná and Etendeka Plateau; or Paraná and Etendeka Province) comprise a large igneous province that includes both the main Paraná traps (in Paraná Basin, a South American geological basin) as well as the sma ...

in South America and Africa (formerly a single province separated by opening of the South Atlantic Ocean), and the Columbia River basalts

The Columbia River Basalt Group is the youngest, smallest and one of the best-preserved continental flood basalt province on Earth, covering over mainly eastern Oregon and Washington, western Idaho, and part of northern Nevada. The basalt grou ...

of North America. Flood basalts in the oceans are known as oceanic plateaus, and include the Ontong Java plateau

The Ontong Java Plateau (OJP) is a massive oceanic plateau located in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, north of the Solomon Islands.

The OJP was formed around (Ma) with a much smaller volcanic event around 90 Ma. Two other southwestern Pacific ...

of the western Pacific Ocean and the Kerguelen Plateau

The Kerguelen Plateau (, ), also known as the Kerguelen–Heard Plateau, is an oceanic plateau and a large igneous province (LIP) located on the Antarctic Plate, in the southern Indian Ocean. It is about to the southwest of Australia and is ...

of the Indian Ocean.

The narrow vertical pipe, or conduit, postulated to connect the plume head to the core-mantle boundary, is viewed as providing a continuous supply of magma to a fixed location, often referred to as a "hotspot". As the overlying tectonic plate (lithosphere) moves over this hotspot, the eruption of magma from the fixed conduit onto the surface is expected to form a chain of volcanoes that parallels plate motion. The Hawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands ( haw, Nā Mokupuni o Hawai‘i) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost ...

chain in the Pacific Ocean is the type example. It has recently been discovered that the volcanic locus of this chain has not been fixed over time, and it thus joined the club of the many type examples that do not exhibit the key characteristic originally proposed.

The eruption of continental flood basalts is often associated with continental rifting

In geology, a rift is a linear zone where the lithosphere is being pulled apart and is an example of extensional tectonics.

Typical rift features are a central linear downfaulted depression, called a graben, or more commonly a half-graben w ...

and breakup. This has led to the hypothesis that mantle plumes contribute to continental rifting and the formation of ocean basins. In the context of the alternative "Plate model", continental breakup is a process integral to plate tectonics, and massive volcanism occurs as a natural consequence when it starts.

The current mantle plume theory is that material and energy from Earth's interior are exchanged with the surface crust in two distinct modes: the predominant, steady state plate tectonic regime driven by upper mantle convection

Mantle convection is the very slow creeping motion of Earth's solid silicate mantle as convection currents carrying heat from the interior to the planet's surface.

The Earth's surface lithosphere rides atop the asthenosphere and the two form ...

, and a punctuated, intermittently dominant, mantle overturn regime driven by plume convection. This second regime, while often discontinuous, is periodically significant in mountain building and continental breakup.

=Chemistry, heat flow and melting

= The chemical and isotopic composition of basalts found at hotspots differs subtly from mid-ocean-ridge basalts. These basalts, also called ocean island basalts (OIBs), are analysed in their radiogenic and stable isotope compositions. In radiogenic isotope systems the originally subducted material creates diverging trends, termed mantle components. Identified mantle components are DMM (depleted mid-ocean ridge basalt (MORB) mantle), HIMU (high U/Pb-ratio mantle), EM1 (enriched mantle 1), EM2 (enriched mantle 2) and FOZO (focus zone). This geochemical signature arises from the mixing of near-surface materials such as subducted slabs and continental sediments, in the mantle source. There are two competing interpretations for this. In the context of mantle plumes, the near-surface material is postulated to have been transported down to the core-mantle boundary by subducting slabs, and to have been transported back up to the surface by plumes. In the context of the Plate hypothesis, subducted material is mostly re-circulated in the shallow mantle and tapped from there by volcanoes.

Stable isotopes like Fe are used to track processes that the uprising material experiences during melting.

The processing of oceanic crust, lithosphere, and sediment through a subduction zone decouples the water-soluble trace elements (e.g., K, Rb, Th) from the immobile trace elements (e.g., Ti, Nb, Ta), concentrating the immobile elements in the oceanic slab (the water-soluble elements are added to the crust in island arc volcanoes).

The chemical and isotopic composition of basalts found at hotspots differs subtly from mid-ocean-ridge basalts. These basalts, also called ocean island basalts (OIBs), are analysed in their radiogenic and stable isotope compositions. In radiogenic isotope systems the originally subducted material creates diverging trends, termed mantle components. Identified mantle components are DMM (depleted mid-ocean ridge basalt (MORB) mantle), HIMU (high U/Pb-ratio mantle), EM1 (enriched mantle 1), EM2 (enriched mantle 2) and FOZO (focus zone). This geochemical signature arises from the mixing of near-surface materials such as subducted slabs and continental sediments, in the mantle source. There are two competing interpretations for this. In the context of mantle plumes, the near-surface material is postulated to have been transported down to the core-mantle boundary by subducting slabs, and to have been transported back up to the surface by plumes. In the context of the Plate hypothesis, subducted material is mostly re-circulated in the shallow mantle and tapped from there by volcanoes.

Stable isotopes like Fe are used to track processes that the uprising material experiences during melting.

The processing of oceanic crust, lithosphere, and sediment through a subduction zone decouples the water-soluble trace elements (e.g., K, Rb, Th) from the immobile trace elements (e.g., Ti, Nb, Ta), concentrating the immobile elements in the oceanic slab (the water-soluble elements are added to the crust in island arc volcanoes). Seismic tomography

Seismic tomography or seismotomography is a technique for imaging the subsurface of the Earth with seismic waves produced by earthquakes or explosions. P-, S-, and surface waves can be used for tomographic models of different resolutions based on ...

shows that subducted

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

oceanic slabs sink as far as the bottom of the mantle transition zone

The transition zone is part of the Earth's mantle, and is located between the lower mantle and the upper mantle, between a depth of 410 and 660 km (250 to 400 mi). The Earth's mantle, including the transition zone, consists primarily o ...

at 650 km depth. Subduction to greater depths is less certain, but there is evidence that they may sink to mid-lower-mantle depths at about 1,500 km depth.

The source of mantle plumes is postulated to be the core-mantle boundary at 3,000 km depth. Because there is little material transport across the core-mantle boundary, heat transfer must occur by conduction, with adiabatic gradients above and below this boundary. The core-mantle boundary is a strong thermal (temperature) discontinuity. The temperature of the core is approximately 1,000 degrees Celsius higher than that of the overlying mantle. Plumes are postulated to rise as the base of the mantle becomes hotter and more buoyant.

Plumes are postulated to rise through the mantle and begin to partially melt on reaching shallow depths in the asthenosphere by decompression melting

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rock is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or l ...

. This would create large volumes of magma. The plume hypothesis postulates that this melt rises to the surface and erupts to form "hot spots".

The lower mantle and the core

large low-shear-velocity provinces

Large low-shear-velocity provinces, LLSVPs, also called LLVPs or superplumes, are characteristic structures of parts of the lowermost mantle (the region surrounding the outer core) of Earth. These provinces are characterized by slow shear wave ve ...

, exist in the lower mantle

The lower mantle, historically also known as the mesosphere, represents approximately 56% of Earth's total volume, and is the region from 660 to 2900 km below Earth's surface; between the transition zone and the outer core. The preliminary ...

under Africa and under the central Pacific. It is postulated that plumes rise from their surface or their edges. Their low seismic velocities were thought to suggest that they are relatively hot, although it has recently been shown that their low wave velocities are due to high density caused by chemical heterogeneity.

Evidence for the theory

Various lines of evidence have been cited in support of mantle plumes. There is some confusion regarding what constitutes support, as there has been a tendency to re-define the postulated characteristics of mantle plumes after observations have been made. Some common and basic lines of evidence cited in support of the theory are linear volcanic chains,noble gas

The noble gases (historically also the inert gases; sometimes referred to as aerogens) make up a class of chemical elements with similar properties; under standard conditions, they are all odorless, colorless, monatomic gases with very low che ...

es, geophysical

Geophysics () is a subject of natural science concerned with the physical processes and physical properties of the Earth and its surrounding space environment, and the use of quantitative methods for their analysis. The term ''geophysics'' so ...

anomalies, and geochemistry

Geochemistry is the science that uses the tools and principles of chemistry to explain the mechanisms behind major geological systems such as the Earth's crust and its oceans. The realm of geochemistry extends beyond the Earth, encompassing the ...

.

=Linear volcanic chains

= The age-progressive distribution of the Hawaiian-Emperor seamount chain has been explained as a result of a fixed, deep-mantle plume rising into the upper mantle, partly melting, and causing a volcanic chain to form as the plate moves overhead relative to the fixed plume source. Other "hot spots" with time-progressive volcanic chains behind them includeRéunion

Réunion (; french: La Réunion, ; previously ''Île Bourbon''; rcf, label= Reunionese Creole, La Rényon) is an island in the Indian Ocean that is an overseas department and region of France. It is located approximately east of the island ...

, the Chagos-Laccadive Ridge, the Louisville Ridge

The Louisville Ridge, also known as the Louisville Seamount Chain, is an underwater chain of over 70 seamounts located in the Southwest portion of the Pacific Ocean. As one of the longest seamount chains on Earth it stretches some Vanderkluysen, ...

, the Ninety East Ridge

The Ninety East Ridge (also rendered as Ninetyeast Ridge, 90E Ridge or 90°E Ridge) is a mid-ocean ridge on the Indian Ocean floor named for its near-parallel strike along the 90th meridian at the center of the Eastern Hemisphere. It is approxima ...

and Kerguelen, Tristan

Tristan (Latin/Brythonic: ''Drustanus''; cy, Trystan), also known as Tristram or Tristain and similar names, is the hero of the legend of Tristan and Iseult. In the legend, he is tasked with escorting the Irish princess Iseult to wed ...

, and Yellowstone

Yellowstone National Park is an American national park located in the western United States, largely in the northwest corner of Wyoming and extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U.S. Congress with the Yellow ...

.

An intrinsic aspect of the plume hypothesis is that the "hot spots" and their volcanic trails have been fixed relative to one another throughout geological time. Whereas there is evidence that the chains listed above are time-progressive, it has, however, been shown that they are not fixed relative to one another. The most remarkable example of this is the Emperor chain, the older part of the Hawaii system, which was formed by migration of volcanic activity across a geo-stationary plate.

Many postulated "hot spots" are also lacking time-progressive volcanic trails, e.g., Iceland, the Galapagos, and the Azores. Mismatches between the predictions of the hypothesis and observations are commonly explained by auxiliary processes such as "mantle wind", "ridge capture", "ridge escape" and lateral flow of plume material.

=Noble gas and other isotopes

= Helium-3 is a primordial isotope that formed in theBig Bang

The Big Bang event is a physical theory that describes how the universe expanded from an initial state of high density and temperature. Various cosmological models of the Big Bang explain the evolution of the observable universe from t ...

. Very little is produced, and little has been added to the Earth by other processes since then. Helium-4

Helium-4 () is a stable isotope of the element helium. It is by far the more abundant of the two naturally occurring isotopes of helium, making up about 99.99986% of the helium on Earth. Its nucleus is identical to an alpha particle, and consis ...

includes a primordial component, but it is also produced by the natural radioactive decay of elements such as uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weakly ...

and thorium

Thorium is a weakly radioactive metallic chemical element with the symbol Th and atomic number 90. Thorium is silvery and tarnishes black when it is exposed to air, forming thorium dioxide; it is moderately soft and malleable and has a high ...

. Over time, helium in the upper atmosphere is lost into space. Thus, the Earth has become progressively depleted in helium, and 3He is not replaced as 4He is. As a result, the ratio 3He/4He in the Earth has decreased over time.

Unusually high 3He/4He have been observed in some, but not all, "hot spots". In mantle plume theory, this is explained by plumes tapping a deep, primordial reservoir in the lower mantle, where the original, high 3He/4He ratios have been preserved throughout geologic time. In the context of the Plate hypothesis, the high ratios are explained by preservation of old material in the shallow mantle. Ancient, high 3He/4He ratios would be particularly easily preserved in materials lacking U or Th, so 4He was not added over time. Olivine

The mineral olivine () is a magnesium iron silicate with the chemical formula . It is a type of nesosilicate or orthosilicate. The primary component of the Earth's upper mantle, it is a common mineral in Earth's subsurface, but weathers qui ...

and dunite

Dunite (), also known as olivinite (not to be confused with the mineral olivenite), is an intrusive igneous rock of ultramafic composition and with phaneritic (coarse-grained) texture. The mineral assemblage is greater than 90% olivine, with ...

, both found in subducted crust, are materials of this sort.

Other elements, e.g. osmium

Osmium (from Greek grc, ὀσμή, osme, smell, label=none) is a chemical element with the symbol Os and atomic number 76. It is a hard, brittle, bluish-white transition metal in the platinum group that is found as a trace element in alloys, mos ...

, have been suggested to be tracers of material arising from near to the Earth's core, in basalts at oceanic islands. However, so far conclusive proof for this is lacking.

=Geophysical anomalies

=Seismic waves

A seismic wave is a wave of acoustic energy that travels through the Earth. It can result from an earthquake, volcanic eruption, magma movement, a large landslide, and a large man-made explosion that produces low-frequency acoustic energy. ...

generated by large earthquakes enable structure below the Earth's surface to be determined along the ray path. Seismic waves that have traveled a thousand or more kilometers (also called teleseismic waves) can be used to image large regions of Earth's mantle. They also have limited resolution, however, and only structures at least several hundred kilometers in diameter can be detected.

Seismic tomography images have been cited as evidence for a number of mantle plumes in Earth's mantle. There is, however, vigorous on-going discussion regarding whether the structures imaged are reliably resolved, and whether they correspond to columns of hot, rising rock.

The mantle plume hypothesis predicts that domal topographic uplifts will develop when plume heads impinge on the base of the lithosphere. An uplift of this kind occurred when the north Atlantic Ocean opened about 54 million years ago. Some scientists have linked this to a mantle plume postulated to have caused the breakup of Eurasia and the opening of the north Atlantic, now suggested to underlie Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

. Current research has shown that the time-history of the uplift is probably much shorter than predicted, however. It is thus not clear how strongly this observation supports the mantle plume hypothesis.

=Geochemistry

= Basalts found at oceanic islands are geochemically distinct from those found atmid-ocean ridge

A mid-ocean ridge (MOR) is a seafloor mountain system formed by plate tectonics. It typically has a depth of about and rises about above the deepest portion of an ocean basin. This feature is where seafloor spreading takes place along a div ...

s and volcanoes associated with subduction zones

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

(island arc basalts). "Ocean island basalt

Ocean island basalt (OIB) is a volcanic rock, usually basaltic in composition, erupted in oceans away from tectonic plate boundaries. Although ocean island basaltic magma is mainly erupted as basalt lava, the basaltic magma is sometimes modified b ...

" is also similar to basalts found throughout the oceans on both small and large seamounts (thought to be formed by eruptions on the sea floor that did not rise above the surface of the ocean). They are also compositionally similar to some basalts found in the interiors of the continents (e.g., the Snake River Plain

The canyons">Snake River cutting through the plain leaves many canyons and Canyon#List of gorges">gorges, such as this one near Twin Falls, Idaho

The Snake River Plain is a geologic feature located primarily within the U.S. state of Idaho ...

).

In major elements, ocean island basalts are typically higher in iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

(Fe) and titanium

Titanium is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ti and atomic number 22. Found in nature only as an oxide, it can be reduced to produce a lustrous transition metal with a silver color, low density, and high strength, resista ...

(Ti) than mid-ocean ridge basalts at similar magnesium

Magnesium is a chemical element with the symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a shiny gray metal having a low density, low melting point and high chemical reactivity. Like the other alkaline earth metals (group 2 of the periodic ...

(Mg) contents. In trace elements

__NOTOC__

A trace element, also called minor element, is a chemical element whose concentration (or other measure of amount) is very low (a "trace amount"). They are classified into two groups: essential and non-essential. Essential trace elements ...

, they are typically more enriched in the light rare-earth element

The rare-earth elements (REE), also called the rare-earth metals or (in context) rare-earth oxides or sometimes the lanthanides (yttrium and scandium are usually included as rare earths), are a set of 17 nearly-indistinguishable lustrous silv ...

s than mid-ocean ridge basalts. Compared to island arc basalts, ocean island basalts are lower in alumina (Al2O3) and higher in immobile trace elements (e.g., Ti, Nb, Ta).

These differences result from processes that occur during the subduction of oceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the uppermost layer of the oceanic portion of the tectonic plates. It is composed of the upper oceanic crust, with pillow lavas and a dike complex, and the lower oceanic crust, composed of troctolite, gabbro and ultramafi ...

and mantle lithosphere

A lithosphere () is the rigid, outermost rocky shell of a terrestrial planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust and the portion of the upper mantle that behaves elastically on time scales of up to thousands of years ...

. Oceanic crust (and to a lesser extent, the underlying mantle) typically becomes hydrated to varying degrees on the seafloor, partly as the result of seafloor weathering, and partly in response to hydrothermal circulation near the mid-ocean-ridge crest where it was originally formed. As oceanic crust and underlying lithosphere subduct, water is released by dehydration reactions, along with water-soluble elements and trace elements. This enriched fluid rises to metasomatize the overlying mantle wedge and leads to the formation of island arc basalts. The subducting slab is depleted in these water-mobile elements (e.g., K, Rb, Th, Pb) and thus relatively enriched in elements that are not water-mobile (e.g., Ti, Nb, Ta) compared to both mid-ocean ridge and island arc basalts.

Ocean island basalts are also relatively enriched in immobile elements relative to the water-mobile elements. This, and other observations, have been interpreted as indicating that the distinct geochemical signature of ocean island basalts results from inclusion of a component of subducted slab material. This must have been recycled in the mantle, then re-melted and incorporated in the lavas erupted. In the context of the plume hypothesis, subducted slabs are postulated to have been subducted down as far as the core-mantle boundary, and transported back up to the surface in rising plumes. In the plate hypothesis, the slabs are postulated to have been recycled at shallower depths – in the upper few hundred kilometers that make up the upper mantle

The upper mantle of Earth is a very thick layer of rock inside the planet, which begins just beneath the crust (at about under the oceans and about under the continents) and ends at the top of the lower mantle at . Temperatures range from appro ...

. However, the plate hypothesis is inconsistent with both the geochemistry of shallow asthenosphere melts (i.e., Mid-ocean ridge basalts) and with the isotopic compositions of ocean island basalts.

=Seismology

= In 2015, based on data from 273 large earthquakes, researchers compiled a model based onfull waveform tomography

Full may refer to:

* People with the surname Full, including:

** Mr. Full (given name unknown), acting Governor of German Cameroon, 1913 to 1914

* A property in the mathematical field of topology; see Full set

* A property of functors in the mathe ...

, requiring the equivalent of 3 million hours of supercomputer time. Due to computational limitations, high-frequency data still could not be used, and seismic data remained unavailable from much of the seafloor. Nonetheless, vertical plumes, 400 C hotter than the surrounding rock, were visualized under many hotspots, including the Pitcairn

The Pitcairn Islands (; Pitkern: '), officially the Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno Islands, is a group of four volcanic islands in the southern Pacific Ocean that form the sole British Overseas Territory in the Pacific Ocean. The four is ...

, Macdonald

Macdonald, MacDonald or McDonald may refer to:

Organisations

* McDonald's, a chain of fast food restaurants

* McDonald & Co., a former investment firm

* MacDonald Motorsports, a NASCAR team

* Macdonald Realty, a Canadian real estate brokerage f ...

, Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands (Manono Island, Manono an ...

, Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Aust ...

, Marquesas

The Marquesas Islands (; french: Îles Marquises or ' or '; Marquesan: ' (North Marquesan) and ' (South Marquesan), both meaning "the land of men") are a group of volcanic islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France in ...

, Galapagos, Cape Verde

, national_anthem = ()

, official_languages = Portuguese

, national_languages = Cape Verdean Creole

, capital = Praia

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, demonym ...

, and Canary hotspots. They extended nearly vertically from the core-mantle boundary (2900 km depth) to a possible layer of shearing and bending at 1000 km. They were detectable because they were 600–800 km wide, more than three times the width expected from contemporary models. Many of these plumes are in the large low-shear-velocity provinces

Large low-shear-velocity provinces, LLSVPs, also called LLVPs or superplumes, are characteristic structures of parts of the lowermost mantle (the region surrounding the outer core) of Earth. These provinces are characterized by slow shear wave ve ...

under Africa and the Pacific, while some other hotspots such as Yellowstone were less clearly related to mantle features in the model.

The unexpected size of the plumes leaves open the possibility that they may conduct the bulk of the Earth's 44 terawatts of internal heat flow from the core to the surface, and means that the lower mantle convects less than expected, if at all. It is possible that there is a compositional difference between plumes and the surrounding mantle that slows them down and broadens them.

Suggested mantle plume locations

Many different localities have been suggested to be underlain by mantle plumes, and scientists cannot agree on a definitive list. Some scientists suggest that several tens of plumes exist, whereas others suggest that there are none. The theory was really inspired by the Hawaiian volcano system. Hawaii is a large volcanic edifice in the center of the Pacific Ocean, far from any plate boundaries. Its regular, time-progressive chain of islands and seamounts superficially fits the plume theory well. However, it is almost unique on Earth, as nothing as extreme exists anywhere else. The second strongest candidate for a plume location is often quoted to be Iceland, but according to opponents of the plume hypothesis its massive nature can be explained by plate tectonic forces along the mid-Atlantic spreading center.

Mantle plumes have been suggested as the source for

Many different localities have been suggested to be underlain by mantle plumes, and scientists cannot agree on a definitive list. Some scientists suggest that several tens of plumes exist, whereas others suggest that there are none. The theory was really inspired by the Hawaiian volcano system. Hawaii is a large volcanic edifice in the center of the Pacific Ocean, far from any plate boundaries. Its regular, time-progressive chain of islands and seamounts superficially fits the plume theory well. However, it is almost unique on Earth, as nothing as extreme exists anywhere else. The second strongest candidate for a plume location is often quoted to be Iceland, but according to opponents of the plume hypothesis its massive nature can be explained by plate tectonic forces along the mid-Atlantic spreading center.

Mantle plumes have been suggested as the source for flood basalt

A flood basalt (or plateau basalt) is the result of a giant volcanic eruption or series of eruptions that covers large stretches of land or the ocean floor with basalt lava. Many flood basalts have been attributed to the onset of a hotspot reac ...

s. These extremely rapid, large scale eruptions of basaltic magmas have periodically formed continental flood basalt provinces on land and oceanic plateaus in the ocean basins, such as the Deccan Traps

The Deccan Traps is a large igneous province of west-central India (17–24°N, 73–74°E). It is one of the largest volcanic features on Earth, taking the form of a large shield volcano. It consists of numerous layers of solidified flood ...

, the Siberian Traps

The Siberian Traps (russian: Сибирские траппы, Sibirskiye trappy) is a large region of volcanic rock, known as a large igneous province, in Siberia, Russia. The massive eruptive event that formed the traps is one of the large ...

the Karoo-Ferrar

The Karoo and Ferrar Large Igneous Provinces (LIPs) are two large igneous provinces in Southern Africa and Antarctica respectively, collectively known as the Karoo-Ferrar, Gondwana,E.g. or Southeast African LIP, associated with the initial break-u ...

flood basalts of Gondwana

Gondwana () was a large landmass, often referred to as a supercontinent, that formed during the late Neoproterozoic (about 550 million years ago) and began to break up during the Jurassic period (about 180 million years ago). The final st ...

, and the largest known continental flood basalt, the Central Atlantic magmatic province

The Central Atlantic magmatic province (CAMP) is the Earth's largest continental large igneous province, covering an area of roughly 11 million km2. It is composed mainly of basalt that formed before Pangaea broke up in the Mesozoic Era, near the ...

(CAMP).

Many continental flood basalt events coincide with continental rifting. This is consistent with a system that tends toward equilibrium: as matter rises in a mantle plume, other material is drawn down into the mantle, causing rifting.

Plate theory

Thehypothesis

A hypothesis (plural hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. For a hypothesis to be a scientific hypothesis, the scientific method requires that one can testable, test it. Scientists generally base scientific hypotheses on prev ...

of mantle plumes from depth is not universally accepted as explaining all such volcanism. It has required progressive hypothesis-elaboration leading to variant propositions such as mini-plumes and pulsing plumes. Another hypothesis for unusual volcanic regions is the plate theory. This proposes shallower, passive leakage of magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natura ...

from the mantle onto the Earth's surface where extension of the lithosphere permits it, attributing most volcanism to plate tectonic processes, with volcanoes far from plate boundaries resulting from intraplate extension.

The plate theory attributes all

The plate theory attributes all volcanic

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates ...

activity on Earth, even that which appears superficially to be anomalous, to the operation of plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (from the la, label= Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large t ...

. According to the plate theory, the principal cause of volcanism is extension of the lithosphere

A lithosphere () is the rigid, outermost rocky shell of a terrestrial planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust and the portion of the upper mantle that behaves elastically on time scales of up to thousands of years ...

. Extension of the lithosphere is a function of the lithospheric stress field

A stress field is the distribution of internal forces in a body that balance a given set of external forces. Stress fields are widely used in fluid dynamics and materials science.

Consider that one can picture the stress fields as the stress cr ...

. The global distribution of volcanic activity at a given time reflects the contemporaneous lithospheric stress field, and changes in the spatial and temporal distribution of volcanoes reflect changes in the stress field. The main factors governing the evolution of the stress field are:

# Changes in the configuration of plate boundaries

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large t ...

.

# Vertical motions.

# Thermal contraction.

Beginning in the early 2000s, dissatisfaction with the state of the evidence for mantle plumes and the proliferation of

Beginning in the early 2000s, dissatisfaction with the state of the evidence for mantle plumes and the proliferation of ad hoc hypotheses

In science and philosophy, an ''ad hoc'' hypothesis is a hypothesis added to a theory in order to save it from being falsified. Often, ''ad hoc'' hypothesizing is employed to compensate for anomalies not anticipated by the theory in its unmodifie ...

drove a number of geologists, led by Don L. Anderson, Gillian Foulger, and Warren B. Hamilton, to propose a broad alternative based on shallow processes in the upper mantle and above, with an emphasis on plate tectonics as the driving force of magmatism.

The plate hypothesis suggests that "anomalous" volcanism results from lithospheric extension that permits melt to rise passively from the asthenosphere beneath. It is thus the conceptual inverse of the plume hypothesis because the plate hypothesis attributes volcanism to shallow, near-surface processes associated with plate tectonics, rather than active processes arising at the core-mantle boundary.

Lithospheric extension is attributed to processes related to plate tectonics. These processes are well understood at mid-ocean ridges, where most of Earth's volcanism occurs. It is less commonly recognised that the plates themselves deform internally, and can permit volcanism in those regions where the deformation is extensional. Well-known examples are the Basin and Range Province in the western USA, the East African Rift

The East African Rift (EAR) or East African Rift System (EARS) is an active continental rift zone in East Africa. The EAR began developing around the onset of the Miocene, 22–25 million years ago. In the past it was considered to be part of a ...

valley, and the Rhine Graben. Under this hypothesis, variable volumes of magma are attributed to variations in chemical composition (large volumes of volcanism corresponding to more easily molten mantle material) rather than to temperature differences.

While not denying the presence of deep mantle convection and upwelling in general, the plate hypothesis holds that these processes do not result in mantle plumes, in the sense of columnar vertical features that span most of the Earth's mantle, transport large amounts of heat, and contribute to surface volcanism.

Under the umbrella of the plate hypothesis, the following sub-processes, all of which can contribute to permitting surface volcanism, are recognised:

*Continental break-up;

*Fertility at mid-ocean ridges;

*Enhanced volcanism at plate boundary junctions;

*Small-scale sublithospheric convection;

*Oceanic intraplate extension;

*Slab tearing and break-off;

*Shallow mantle convection;

*Abrupt lateral changes in stress at structural discontinuities;

*Continental intraplate extension;

*Catastrophic lithospheric thinning;

*Sublithospheric melt ponding and draining.

Lithospheric extension enables pre-existing melt

Melt may refer to:

Science and technology

* Melting, in physics, the process of heating a solid substance to a liquid

* Melt (manufacturing), the semi-liquid material used in steelmaking and glassblowing

* Melt (geology), magma

** Melt inclusions, ...

in the crust and mantle to escape to the surface. If extension is severe and thins the lithosphere to the extent that the asthenosphere

The asthenosphere () is the mechanically weak and ductile region of the upper mantle of Earth. It lies below the lithosphere, at a depth between ~ below the surface, and extends as deep as . However, the lower boundary of the asthenosphere is ...

rises, then additional melt is produced by decompression upwelling.

A major virtue of the plate theory is that it extends plate tectonics into a unifying account of the Earth's volcanism which dispenses with the need to invoke extraneous hypotheses designed to accommodate instances of volcanic activity which appear superficially to be exceptional.

Origins of the plate theory

Developed during the late 1960s and 1970s, plate tectonics provided an elegant explanation for most of the Earth's volcanic activity. At spreading boundaries where plates move apart, the asthenosphere decompresses and melts to form newoceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the uppermost layer of the oceanic portion of the tectonic plates. It is composed of the upper oceanic crust, with pillow lavas and a dike complex, and the lower oceanic crust, composed of troctolite, gabbro and ultramafi ...

. At subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, ...

zones, slabs of oceanic crust sink into the mantle, dehydrate, and release volatiles

Volatiles are the group of chemical elements and chemical compounds that can be readily vaporized. In contrast with volatiles, elements and compounds that are not readily vaporized are known as refractory substances.

On planet Earth, the term ...

which lower the melting temperature and give rise to volcanic arc

A volcanic arc (also known as a magmatic arc) is a belt of volcanoes formed above a subducting oceanic tectonic plate,

with the belt arranged in an arc shape as seen from above. Volcanic arcs typically parallel an oceanic trench, with the arc ...

s and back-arc extensions. Several volcanic provinces, however, do not fit this simple picture and have traditionally been considered exceptional cases which require a non-plate-tectonic explanation.

Just prior to the development of plate tectonics in the early 1960s, the Canadian Geophysicist

Geophysics () is a subject of natural science concerned with the physical processes and physical properties of the Earth and its surrounding space environment, and the use of quantitative methods for their analysis. The term ''geophysics'' so ...

John Tuzo Wilson suggested that chains of volcanic islands form from movement of the seafloor over relatively stationary hotspots

Hotspot, Hot Spot or Hot spot may refer to:

Places

* Hot Spot, Kentucky, a community in the United States

Arts, entertainment, and media Fictional entities

* Hot Spot (comics), a name for the DC Comics character Isaiah Crockett

* Hot Spot (Tra ...

in stable centres of mantle convection

Convection is single or multiphase fluid flow that occurs spontaneously due to the combined effects of material property heterogeneity and body forces on a fluid, most commonly density and gravity (see buoyancy). When the cause of the c ...

cells. In the early 1970s, Wilson's idea was revived by the American geophysicist W. Jason Morgan. In order to account for the long-lived supply of magma that some volcanic regions seemed to require, Morgan modified the hypothesis, shifting the source to a thermal boundary layer

In physics and fluid mechanics, a boundary layer is the thin layer of fluid in the immediate vicinity of a bounding surface formed by the fluid flowing along the surface. The fluid's interaction with the wall induces a no-slip boundary cond ...

. Because of the perceived fixity of some volcanic sources relative to the plates, he proposed that this thermal boundary was deeper than the convecting upper mantle on which the plates ride and located it at the core-mantle boundary, 3,000 km beneath the surface. He suggested that narrow convection currents rise from fixed points at this thermal boundary and form conduits which transport abnormally hot material to the surface.

This, the mantle plume

A mantle plume is a proposed mechanism of convection within the Earth's mantle, hypothesized to explain anomalous volcanism. Because the plume head partially melts on reaching shallow depths, a plume is often invoked as the cause of volcanic hot ...

theory, became the dominant explanation for apparent volcanic anomalies for the remainder of the 20th century. Testing the hypothesis, however, is beset with difficulties. A central tenet of the plume theory is that the source of melt is significantly hotter than the surrounding mantle, so the most direct test is to measure the source temperature of magmas. This is difficult as the petrogenesis

Petrogenesis, also known as petrogeny, is a branch of petrology dealing with the origin and formation of rocks. While the word petrogenesis is most commonly used to refer to the processes that form igneous rocks, it can also include metamorphic an ...

of magmas is extremely complex, rendering inferences from petrology

Petrology () is the branch of geology that studies rocks and the conditions under which they form. Petrology has three subdivisions: igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary petrology. Igneous and metamorphic petrology are commonly taught together ...

or geochemistry

Geochemistry is the science that uses the tools and principles of chemistry to explain the mechanisms behind major geological systems such as the Earth's crust and its oceans. The realm of geochemistry extends beyond the Earth, encompassing the ...

to source temperatures unreliable. Seismic

Seismology (; from Ancient Greek σεισμός (''seismós'') meaning "earthquake" and -λογία (''-logía'') meaning "study of") is the scientific study of earthquakes and the propagation of elastic waves through the Earth or through other ...

data used to provide additional constraints on source temperatures are highly ambiguous. In addition to this, several predictions of the plume theory have proved unsuccessful at many locations purported to be underlain by mantle plumes, and there are also significant theoretical reasons to doubt the hypothesis.

The foregoing issues have inspired a growing number of geoscientists, led by American geophysicist Don L. Anderson and British geophysicist Gillian R. Foulger, to pursue other explanations for volcanic activity not easily accounted for by plate tectonics. Rather than introducing another extraneous theory, these explanations essentially expand the scope of plate tectonics in ways that can accommodate volcanic activity previously thought to be outside its remit. The key modification to the basic plate-tectonic model here is a relaxation of the assumption that plates are rigid. This implies that lithospheric extension occurs not only at spreading plate boundaries but throughout plate interiors, a phenomenon that is well supported both theoretically and empirically.

Over the last two decades, the plate theory has developed into a cohesive research programme, attracting many adherents, and occupying researchers in several subdisciplines of Earth science

Earth science or geoscience includes all fields of natural science related to the planet Earth. This is a branch of science dealing with the physical, chemical, and biological complex constitutions and synergistic linkages of Earth's four spher ...

. It has also been the focus of several international conferences and many peer-reviewed papers and is the subject of two major Geological Society of America

The Geological Society of America (GSA) is a nonprofit organization dedicated to the advancement of the geosciences.

History

The society was founded in Ithaca, New York, in 1888 by Alexander Winchell, John J. Stevenson, Charles H. Hitch ...

edited volumes and a textbook.

Since 2003, discussion and development of the plate theory has been fostered by the Durham University(UK)-hosted websitmantleplumes.org

a major international forum with contributions from geoscientists working in a wide variety of specialties.

Lithospheric extension

Global-scale lithospheric extension is a necessary consequence of the non-closure of plate motion circuits and is equivalent to an additional slow-spreading boundary. Extension results principally from the following three processes. # Changes in the configuration of plate boundaries. These can result from various processes including the formation or annihilation of plates and boundaries and slab rollback (vertical sinking of subducting slabs causing oceanward migration of trenches). # Vertical motions resulting fromdelamination

Delamination is a mode of failure where a material fractures into layers. A variety of materials including laminate composites and concrete can fail by delamination. Processing can create layers in materials such as steel formed by rolling an ...

of the lower crust and mantle lithosphere and isostatic adjustment following erosion

Erosion is the action of surface processes (such as water flow or wind) that removes soil, rock, or dissolved material from one location on the Earth's crust, and then transports it to another location where it is deposited. Erosion is di ...

, orogeny

Orogeny is a mountain building process. An orogeny is an event that takes place at a convergent plate margin when plate motion compresses the margin. An '' orogenic belt'' or ''orogen'' develops as the compressed plate crumples and is uplifted ...

, or melting of ice caps.

# Thermal contraction, which sums to the largest amount across large plates such as the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

.

Extension resulting from these processes manifests in a variety of structures including continental rift zone

A rift zone is a feature of some volcanoes, especially shield volcanoes, in which a set of linear cracks (or rifts) develops in a volcanic edifice, typically forming into two or three well-defined regions along the flanks of the vent. Believed t ...

s (e.g., the East African Rift

The East African Rift (EAR) or East African Rift System (EARS) is an active continental rift zone in East Africa. The EAR began developing around the onset of the Miocene, 22–25 million years ago. In the past it was considered to be part of a ...

), diffuse oceanic plate boundaries (e.g., Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

), continental back-arc extensional regions (e.g., the Basin and Range Province

The Basin and Range Province is a vast physiographic region covering much of the inland Western United States and northwestern Mexico. It is defined by unique basin and range topography, characterized by abrupt changes in elevation, alternatin ...

in the Western United States

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Far West, and the West) is the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the meaning of the term ''the Wes ...

), oceanic back-arc basins (e.g., the Manus Basin in the Bismarck Sea

The Bismarck Sea (, ) lies in the southwestern Pacific Ocean within the nation of Papua New Guinea. It is located northeast of the island of New Guinea and south of the Bismarck Archipelago. It has coastlines in districts of the Islands Region, ...

off Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

), fore-arc regions (e.g., the western Pacific), and continental regions undergoing lithospheric delamination (e.g., New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 List of islands of New Zealand, smaller islands. It is the ...

).

Continental breakup begins with rifting. When extension is persistent and entirely compensated by magma from asthenospheric upwelling, oceanic crust is formed, and the rift becomes a spreading plate boundary. If extension is isolated and ephemeral it is classified as intraplate. Rifting can occur in both oceanic and continental crust and ranges from minor to amounts approaching those seen at spreading boundaries. All can give rise to magmatism.

Various extensional styles are seen in the northeast Atlantic. Continental rifting began in the late Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ' ...

and was followed by catastrophic destabilisation in the late Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

and early Paleocene

The Paleocene, ( ) or Palaeocene, is a geological epoch that lasted from about 66 to 56 million years ago (mya). It is the first epoch of the Paleogene Period in the modern Cenozoic Era. The name is a combination of the Ancient Greek ''pal ...

. The latter was possibly caused by rollback of the Alpine slab, which generated extension throughout Europe. More severe rifting occurred along the Caledonian Suture, a zone of pre-existing weakness where the Iapetus Ocean

The Iapetus Ocean (; ) was an ocean that existed in the late Neoproterozoic and early Paleozoic eras of the geologic timescale (between 600 and 400 million years ago). The Iapetus Ocean was situated in the southern hemisphere, between the paleoc ...

closed around 420 Ma. As extension became localised, oceanic crust began to form around 54 Ma, with diffuse extension persisting around Iceland.

Some intracontinental rifts are essentially failed continental breakup axes, and some of these form triple junctions with plate boundaries. The East African Rift, for example, forms a triple junction with the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

and the Gulf of Aden

The Gulf of Aden ( ar, خليج عدن, so, Gacanka Cadmeed 𐒅𐒖𐒐𐒕𐒌 𐒋𐒖𐒆𐒗𐒒) is a deepwater gulf of the Indian Ocean between Yemen to the north, the Arabian Sea to the east, Djibouti to the west, and the Guardafui Chan ...

, both of which have progressed to the seafloor spreading stage. Likewise, the Mid-American Rift constitutes two arms of a triple junction along with a third which separated the Amazonian Craton

The Amazonian Craton is a geologic province located in South America. It occupies a large portion of the central, north and eastern part of the continent and represents one of Earth's largest cratonic regions. The Guiana Shield and Central Braz ...

from Laurentia

Laurentia or the North American Craton is a large continental craton that forms the ancient geological core of North America. Many times in its past, Laurentia has been a separate continent, as it is now in the form of North America, althoug ...

around 1.1 Ga.

Diverse volcanic activity resulting from lithospheric extension has occurred throughout the western United States. The Cascade Volcanoes

The Cascade Volcanoes (also known as the Cascade Volcanic Arc or the Cascade Arc) are a number of volcanoes in a volcanic arc in western North America, extending from southwestern British Columbia through Washington and Oregon to Northern Cali ...

are a back-arc volcanic chain extending from British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include ...

to Northern California

Northern California (colloquially known as NorCal) is a geographic and cultural region that generally comprises the northern portion of the U.S. state of California. Spanning the state's northernmost 48 counties, its main population centers incl ...

. Back-arc extension continues to the east in the Basin and Range Province

The Basin and Range Province is a vast physiographic region covering much of the inland Western United States and northwestern Mexico. It is defined by unique basin and range topography, characterized by abrupt changes in elevation, alternatin ...

, with small-scale volcanism distributed throughout the region.

The Pacific Plate