International Association of Geodesy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The International Association of Geodesy (IAG) is a constituent association of the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics focusing on the science which measures and describes the Earth's shape, its rotation and gravity field.

Seventeen years after Bessel calculated his ellipsoid of reference, some of the meridian arcs the German astronomer had used for his calculation had been enlarged. This was a very important circumstance because the influence of random errors due to vertical deflections was minimized in proportion to the length of the meridian arcs: the longer the meridian arcs, the more precise the image of the

Seventeen years after Bessel calculated his ellipsoid of reference, some of the meridian arcs the German astronomer had used for his calculation had been enlarged. This was a very important circumstance because the influence of random errors due to vertical deflections was minimized in proportion to the length of the meridian arcs: the longer the meridian arcs, the more precise the image of the  It was well known that by measuring the latitude of two stations in

It was well known that by measuring the latitude of two stations in  Significant improvements in gravity measuring instruments must also be attributed to Bessel. He devised a gravimeter constructed by Adolf Repsold which was first used in

Significant improvements in gravity measuring instruments must also be attributed to Bessel. He devised a gravimeter constructed by Adolf Repsold which was first used in

IUGG Report

(2012) pg 47-50

IAG History: Photos of the Presidents and Secretaries

''Terrestrial Reference Frames - Connecting the World through Geodesy''

(2023) GGOS short video {{authority control International geodesy organizations International scientific organizations International organisations based in Germany Scientific organizations established in 1940 Earth sciences societies International geographic data and information organizations

History

The precursors to the IAG were arc measurement campaigns. The IAG was founded in 1862 as the ''Mitteleuropäische Gradmessung'' (Central European Arc Measurement), later became the ''Europäische Gradmessung'' (European Arc Measurement) in 1867, the ''Internationale Erdmessung'' (''Association Geodésique Internationale'' in French and "International Geodetic Association" in English) in 1886, and took its present name in 1946. In the second half of the 19th century, the creation of the International Geodetic Association marked, followingFriedrich Wilhelm Bessel

Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel (; 22 July 1784 – 17 March 1846) was a German astronomer, mathematician, physicist, and geodesist. He was the first astronomer who determined reliable values for the distance from the Sun to another star by the method ...

and Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve

Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve (, trans. ''Vasily Yakovlevich Struve''; 15 April 1793 – ) was a Baltic German astronomer and geodesist. He is best known for studying double stars and initiating a triangulation survey later named Struve ...

examples, the systematic adoption of more rigorous methods among them the application of the least squares

The method of least squares is a mathematical optimization technique that aims to determine the best fit function by minimizing the sum of the squares of the differences between the observed values and the predicted values of the model. The me ...

in geodesy. It became possible to accurately measure parallel arcs, since the difference in longitude between their ends could be determined thanks to the invention of the electrical telegraph

Electrical telegraphy is point-to-point distance communicating via sending electric signals over wire, a system primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most wid ...

. Furthermore, advances in metrology

Metrology is the scientific study of measurement. It establishes a common understanding of Unit of measurement, units, crucial in linking human activities. Modern metrology has its roots in the French Revolution's political motivation to stan ...

combined with those of gravimetry

Gravimetry is the measurement of the strength of a gravitational field. Gravimetry may be used when either the magnitude of a gravitational field or the properties of matter responsible for its creation are of interest. The study of gravity c ...

have led to a new era of geodesy

Geodesy or geodetics is the science of measuring and representing the Figure of the Earth, geometry, Gravity of Earth, gravity, and Earth's rotation, spatial orientation of the Earth in Relative change, temporally varying Three-dimensional spac ...

. If precision metrology had needed the help of geodesy, the latter could not continue to prosper without the help of metrology. It was then necessary to define a single unit to express all the measurements of terrestrial arcs and all determinations of the gravitational acceleration

In physics, gravitational acceleration is the acceleration of an object in free fall within a vacuum (and thus without experiencing drag (physics), drag). This is the steady gain in speed caused exclusively by gravitational attraction. All bodi ...

by means of pendulum.Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero, ''Discursos leidos ante la Real Academia de Ciencias Exactas Fisicas y Naturales en la recepcion pública de Don Joaquin Barraquer y Rovira'', Madrid, Imprenta de la Viuda e Hijo de D.E. Aguado, 1881, pp. 70–78

As early as 1861, Johann Jacob Baeyer sent a memorandum to the King of Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

recommending international collaboration in Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

with the aim of determining the shape and dimensions of the Earth. At the time of its creation, the association had sixteen member countries: Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

, Kingdom of Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southe ...

, Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

, seven German states (Grand Duchy of Baden

The Grand Duchy of Baden () was a German polity on the east bank of the Rhine. It originally existed as a sovereign state from 1806 to 1871 and later as part of the German Empire until 1918.

The duchy's 12th-century origins were as a Margravia ...

, Kingdom of Bavaria

The Kingdom of Bavaria ( ; ; spelled ''Baiern'' until 1825) was a German state that succeeded the former Electorate of Bavaria in 1806 and continued to exist until 1918. With the unification of Germany into the German Empire in 1871, the kingd ...

, Kingdom of Hanover

The Kingdom of Hanover () was established in October 1814 by the Congress of Vienna, with the restoration of George III to his Hanoverian territories after the Napoleonic Wars, Napoleonic era. It succeeded the former Electorate of Hanover, and j ...

, Mecklenburg

Mecklenburg (; ) is a historical region in northern Germany comprising the western and larger part of the federal-state Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. The largest cities of the region are Rostock, Schwerin, Neubrandenburg, Wismar and Güstrow. ...

, Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (, ) was a German state that existed from 1701 to 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946. It played a signif ...

, Kingdom of Saxony

The Kingdom of Saxony () was a German monarchy in Central Europe between 1806 and 1918, the successor of the Electorate of Saxony. It joined the Confederation of the Rhine after the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, later joining the German ...

, Saxe-Coburg and Gotha), Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

, Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

(for Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

), United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway, as well as Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

. The Central European Arc Measurement created a Central Office, located at the Prussian Geodetic Institute, whose management was entrusted to Johann Jacob Baeyer.

Baeyer's goal was a new determination of anomalies in the shape of the Earth using precise triangulations, combined with gravity measurements. This involved determining the geoid

The geoid ( ) is the shape that the ocean surface would take under the influence of the gravity of Earth, including gravitational attraction and Earth's rotation, if other influences such as winds and tides were absent. This surface is exte ...

by means of gravimetric and leveling measurements, in order to deduce the exact knowledge of the terrestrial spheroid while taking into account local variations. To resolve this problem, it was necessary to carefully study considerable areas of land in all directions. Baeyer developed a plan to coordinate geodetic surveys in the space between the parallels of Palermo

Palermo ( ; ; , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital (political), capital of both the autonomous area, autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The ...

and Christiana (Oslo

Oslo ( or ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of 1,064,235 in 2022 ...

) and the meridians of Bonn

Bonn () is a federal city in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, located on the banks of the Rhine. With a population exceeding 300,000, it lies about south-southeast of Cologne, in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ruhr region. This ...

and Trunz (German name for Milejewo in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

). This territory was covered by a triangle network and included more than thirty observatories or stations whose position was determined astronomically. Bayer proposed to remeasure ten arcs of meridians and a larger number of arcs of parallels, to compare the curvature of the meridian arcs on the two slopes of the Alps

The Alps () are some of the highest and most extensive mountain ranges in Europe, stretching approximately across eight Alpine countries (from west to east): Monaco, France, Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Germany, Austria and Slovenia.

...

, in order to determine the influence of this mountain range on vertical deflection. Baeyer also planned to determine the curvature of the seas, the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

and Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

in the south, the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

and the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

in the north. In his mind, the cooperation of all the States of Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

could open the field to scientific research of the highest interest, research that each State, taken in isolation, was not able to undertake.

Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel

Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel (; 22 July 1784 – 17 March 1846) was a German astronomer, mathematician, physicist, and geodesist. He was the first astronomer who determined reliable values for the distance from the Sun to another star by the method ...

using the method of least squares

The method of least squares is a mathematical optimization technique that aims to determine the best fit function by minimizing the sum of the squares of the differences between the observed values and the predicted values of the model. The me ...

calculated from several arc measurements a new value for the flattening of the Earth, which he determined as . Errors in the method of calculating the length of the arc measurement of Delambre and Méchain were taken into account by Bessel when he proposed his reference ellipsoid

An Earth ellipsoid or Earth spheroid is a mathematical figure approximating the Earth's form, used as a reference frame for computations in geodesy, astronomy, and the geosciences. Various different ellipsoids have been used as approximation ...

in 1841. The definitive length of the had required a value for the non-spherical shape of the Earth, known as the flattening of the Earth. The Weights and Measures Commission adopted, in 1799, a flattening of based on analysis by Pierre-Simon Laplace

Pierre-Simon, Marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French polymath, a scholar whose work has been instrumental in the fields of physics, astronomy, mathematics, engineering, statistics, and philosophy. He summariz ...

who combined the arc of Peru and the data of the meridian arc of Delambre and Méchain. Combining these two data sets Laplace succeeded to estimate the flattening anew and was happy to find the suitable value . It also fitted well with his estimate based on 15 pendulum measurements Bessel's reference ellipsoid

An Earth ellipsoid or Earth spheroid is a mathematical figure approximating the Earth's form, used as a reference frame for computations in geodesy, astronomy, and the geosciences. Various different ellipsoids have been used as approximation ...

would long be used by geodesists. An even more accurate value was proposed in 1901 by Friedrich Robert Helmert according to gravity measurements performed under the auspices of the International Geodetic Association.

Earth ellipsoid

An Earth ellipsoid or Earth spheroid is a mathematical figure approximating the Earth's form, used as a reference frame for computations in geodesy, astronomy, and the geosciences. Various different ellipsoids have been used as approximation ...

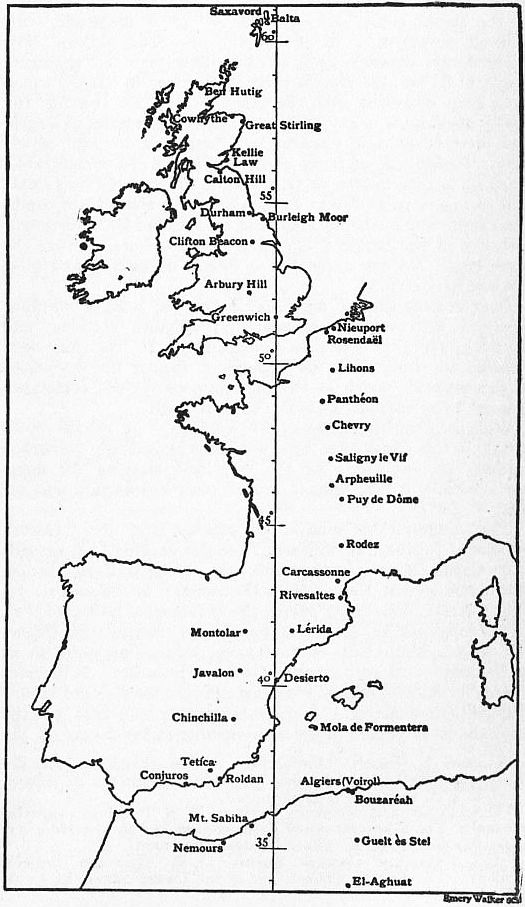

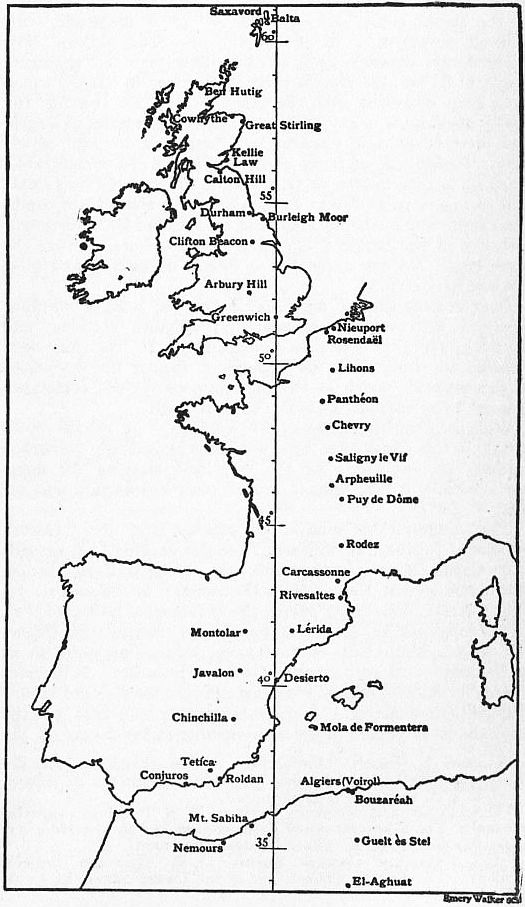

would be. After the Struve Geodetic Arc measurement, it was resolved in the 1860s, at the initiative of Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero, future president of both the International Geodetic Association and the International Committee for Weights and Measure, to remeasure the arc of meridian from Dunkirk

Dunkirk ( ; ; ; Picard language, Picard: ''Dunkèke''; ; or ) is a major port city in the Departments of France, department of Nord (French department), Nord in northern France. It lies from the Belgium, Belgian border. It has the third-larg ...

to Formentera and to extend it from Shetland

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands, and Norway, marking the northernmost region of the United Kingdom. The islands lie about to the ...

to the Sahara

The Sahara (, ) is a desert spanning across North Africa. With an area of , it is the largest hot desert in the world and the list of deserts by area, third-largest desert overall, smaller only than the deserts of Antarctica and the northern Ar ...

. This did not pave the way to a new definition of the metre because it was known that the theoretical definition of the metre had been inaccessible and misleading at the time of Delambre and Mechain arc measurement, as the geoid

The geoid ( ) is the shape that the ocean surface would take under the influence of the gravity of Earth, including gravitational attraction and Earth's rotation, if other influences such as winds and tides were absent. This surface is exte ...

is a ball, which on the whole can be assimilated to an oblate spheroid

A spheroid, also known as an ellipsoid of revolution or rotational ellipsoid, is a quadric surface (mathematics), surface obtained by Surface of revolution, rotating an ellipse about one of its principal axes; in other words, an ellipsoid with t ...

, but which in detail differs from it so as to prohibit any generalization and any extrapolation from the measurement of a single meridian arc. In 1859, Friedrich von Schubert demonstrated that several meridians had not the same length, confirming an hypothesis of Jean Le Rond d'Alembert

Jean-Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert ( ; ; 16 November 1717 – 29 October 1783) was a French mathematician, mechanician, physicist, philosopher, and music theorist. Until 1759 he was, together with Denis Diderot, a co-editor of the ''Encyclopé ...

. He also proposed an ellipsoid with three unequal axes. In 1860, Elie Ritter, a mathematician from Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

, using Schubert's data computed that the Earth ellipsoid could rather be a spheroid of revolution accordingly to Adrien-Marie Legendre

Adrien-Marie Legendre (; ; 18 September 1752 – 9 January 1833) was a French people, French mathematician who made numerous contributions to mathematics. Well-known and important concepts such as the Legendre polynomials and Legendre transforma ...

's model. However, the following year, resuming his calculation on the basis of all the data available at the time, Ritter came to the conclusion that the problem was only resolved in an approximate manner, the data appearing too scant, and for some affected by vertical deflections, in particular the latitude of Montjuïc in the French meridian arc which determination had also been affected in a lesser proportion by systematic errors of the repeating circle. It was well known that by measuring the latitude of two stations in

It was well known that by measuring the latitude of two stations in Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

, Méchain had found that the difference between these latitudes was greater than predicted by direct measurement of distance by triangulation and that he did not dare to admit this inaccuracy. This was later explained by clearance in the central axis of the repeating circle causing wear and consequently the zenith

The zenith (, ) is the imaginary point on the celestial sphere directly "above" a particular location. "Above" means in the vertical direction (Vertical and horizontal, plumb line) opposite to the gravity direction at that location (nadir). The z ...

measurements contained significant systematic errors

Observational error (or measurement error) is the difference between a measurement, measured value of a physical quantity, quantity and its unknown true value.Dodge, Y. (2003) ''The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical Terms'', OUP. Such errors are ...

.Martina Schiavon. La geodesia y la investigación científica en la Francia del siglo XIX : la medida del arco de meridiano franco-argelino (1870–1895). ''Revista Colombiana de Sociología'', 2004, Estudios sociales de la ciencia y la tecnologia, 23, pp. 11–30. Polar motion

Polar motion of the Earth is the motion of the Earth's rotation, Earth's rotational axis relative to its Earth's crust, crust. This is measured with respect to a reference frame in which the solid Earth is fixed (a so-called ''Earth-centered, Ea ...

predicted by Leonhard Euler

Leonhard Euler ( ; ; ; 15 April 170718 September 1783) was a Swiss polymath who was active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, logician, geographer, and engineer. He founded the studies of graph theory and topology and made influential ...

and later discovered by Seth Carlo Chandler also had an impact on accuracy of latitudes' determinations. Among all these sources of error, it was mainly an unfavourable vertical deflection that gave an inaccurate determination of Barcelona's latitude

In geography, latitude is a geographic coordinate system, geographic coordinate that specifies the north-south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from −90° at t ...

and a metre "too short" compared to a more general definition taken from the average of a large number of arcs.

Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

and Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

joined the European Arc Measurement in 1866. French Empire hesitated for a long time before giving in to the demands of the Association, which asked the French geodesists to take part in its work. It was only after the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

, that Charles-Eugène Delaunay represented France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

at the Congress of Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

in 1871. In 1874, Hervé Faye was appointed member of the Permanent Commission which was presided by Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero.

Significant improvements in gravity measuring instruments must also be attributed to Bessel. He devised a gravimeter constructed by Adolf Repsold which was first used in

Significant improvements in gravity measuring instruments must also be attributed to Bessel. He devised a gravimeter constructed by Adolf Repsold which was first used in Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

by Emile Plantamour, Charles Sanders Peirce

Charles Sanders Peirce ( ; September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American scientist, mathematician, logician, and philosopher who is sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism". According to philosopher Paul Weiss (philosopher), Paul ...

and Isaac-Charles Élisée Cellérier (1818–1889), a Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

n mathematician soon independently discovered a mathematical formula to correct systematic errors

Observational error (or measurement error) is the difference between a measurement, measured value of a physical quantity, quantity and its unknown true value.Dodge, Y. (2003) ''The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical Terms'', OUP. Such errors are ...

of this device which had been noticed by Plantamour and Adolphe Hirsch. This would allow Friedrich Robert Helmert to determine a remarkably accurate value of for the flattening of the Earth when he proposed his ellipsoid of reference.

This was also the result of the Metre Convention

The Metre Convention (), also known as the Treaty of the Metre, is an international treaty that was signed in Paris on 20 May 1875 by representatives of 17 nations: Argentina, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, France, German Empire, Ge ...

of 1875, when the metre was adopted as an international scientific unit of length for the convenience of continental European geodesists following forerunners such as Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler later Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero.

Since the metre was originally defined, each time a new measurement is made, with more accurate instruments, methods or techniques, it is said that the metre is based on some error, from calculations or measurements. When Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero first president of both the International Geodetic Association and the International Committee for Weigths and Measures took part to the remeasurement and extension of the arc measurement of Delambre and Méchain, mathematicians like Legendre and Gauss

Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss (; ; ; 30 April 177723 February 1855) was a German mathematician, astronomer, Geodesy, geodesist, and physicist, who contributed to many fields in mathematics and science. He was director of the Göttingen Observat ...

had developed new methods for processing data, including the " least squares method" which allowed to compare experimental data tainted with observational error

Observational error (or measurement error) is the difference between a measured value of a quantity and its unknown true value.Dodge, Y. (2003) ''The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical Terms'', OUP. Such errors are inherent in the measurement ...

s to a mathematical model. Moreover the International Bureau of Weights and Measures

The International Bureau of Weights and Measures (, BIPM) is an List of intergovernmental organizations, intergovernmental organisation, through which its 64 member-states act on measurement standards in areas including chemistry, ionising radi ...

would have a central role for international geodetic measurements as Charles Édouard Guillaume's discovery of invar

Invar, also known generically as FeNi36 (64FeNi in the US), is a nickel–iron alloy notable for its uniquely low coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE or α). The name ''Invar'' comes from the word ''invariable'', referring to its relative lac ...

minimized the impact of measurement inaccuracies due to temperature systematic errors

Observational error (or measurement error) is the difference between a measurement, measured value of a physical quantity, quantity and its unknown true value.Dodge, Y. (2003) ''The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical Terms'', OUP. Such errors are ...

. The Earth measurements thus underscored the importance of the scientific method at a time when statistics

Statistics (from German language, German: ', "description of a State (polity), state, a country") is the discipline that concerns the collection, organization, analysis, interpretation, and presentation of data. In applying statistics to a s ...

were implemented in geodesy. As a leading scientist of his time, Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero was one of the 81 initial members of the International Statistical Institute (ISI) and delegate of Spain to the first ISI session (now called World Statistic Congress) in Rome in 1887.

In the 19th century, astronomers and geodesists were concerned with questions of longitude and time, because they were responsible for determining them scientifically and used them continually in their studies. The International Geodetic Association, which had covered Europe with a network of fundamental longitudes, took an interest in the question of an internationally-accepted prime meridian at its seventh general conference in Rome in 1883. Indeed, the Association was already providing administrations with the bases for topographical surveys, and engineers with the fundamental benchmarks for their levelling. It seemed natural that it should contribute to the achievement of significant progress in navigation, cartography and geography, as well as in the service of major communications institutions, railways and telegraphs. From a scientific point of view, to be a candidate for the status of international prime meridian, the proponent needed to satisfy three important criteria. According to the report by Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero, it must have a first-rate astronomical observatory, be directly linked by astronomical observations to other nearby observatories, and be attached to a network of first-rate triangles in the surrounding country. Four major observatories could satisfy these requirements: Greenwich

Greenwich ( , , ) is an List of areas of London, area in south-east London, England, within the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Greater London, east-south-east of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime hi ...

, Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

and Washington. The conference concluded that Greenwich Observatory best corresponded to the geographical, nautical, astronomical and cartographic conditions that guided the choice of an international prime meridian, and recommended the governments should adopt it as the world standard. The Conference further hoped that, if the whole world agreed on the unification of longitudes and times by the Association's choosing the Greenwich meridian, Great Britain might respond in favour of the unification of weights and measures, by adhering to the Metre Convention

The Metre Convention (), also known as the Treaty of the Metre, is an international treaty that was signed in Paris on 20 May 1875 by representatives of 17 nations: Argentina, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, France, German Empire, Ge ...

.

The International Geodetic Association gained global importance with the accession of Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

, Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

and Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

in 1888; Argentina

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in the southern half of South America. It covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourt ...

and United-States in 1889; and British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

in 1898. The convention of the International Geodetic Association expired at the end of 1916. It was not renewed due to the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. However, the activities of the International Latitude Service were continued through an thanks to the efforts of H.G. van de Sande Bakhuyzen and Raoul Gautier (1854–1931), respectively directors of Leiden Observatory and Geneva Observatory.

During the war, many scientists were concerned with the means to be considered for resuming, at the end of hostilities, international scientific work. An essentially American and British idea was to group together the scientific unions relating to various disciplines under the authority of a Supreme Council. An international conference, which brought together in Brussels

Brussels, officially the Brussels-Capital Region, (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) is a Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium#Regions, region of Belgium comprising #Municipalit ...

in July 1919 the scientists of the countries allied or associated in the fight against Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and of a certain number of neutral states, created an International Science Council

The International Science Council (ISC) is an international non-governmental organization that unites scientific bodies at various levels across the social and natural sciences. The ISC was formed with its inaugural general assembly on 4 July 20 ...

and various unions dependent on this Council; but, Geodesy

Geodesy or geodetics is the science of measuring and representing the Figure of the Earth, geometry, Gravity of Earth, gravity, and Earth's rotation, spatial orientation of the Earth in Relative change, temporally varying Three-dimensional spac ...

, instead of being free and independent as before, was associated with the Geophysical Sciences in the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics which first president was Charles Jean-Pierre Lallemand.

Overview

At present there are 4 commissions and one inter-commission committee: * Reference Frames * Gravity Field * Geodynamics and Earth Rotation * Positioning & Applications * Inter-commission Committee on TheoryInternational Services

The twelve IAG Services are split into three general topic areas: geodesy (IERS, IDS, IGS, ILRS, and IVS), gravity (IGFS, ICGEM, IDEMS, ISG, IGETS and BGI) and sea level (PSMSL). * International Gravimetric Bureau (French: Bureau Gravimétrique International) (BGI) * International Center for Global Earth Models (ICGEM) * InternationalDigital Elevation Model

A digital elevation model (DEM) or digital surface model (DSM) is a 3D computer graphics representation of elevation data to represent terrain or overlaying objects, commonly of a planet, Natural satellite, moon, or asteroid. A "global DEM" refer ...

Service (IDEMS)

* International DORIS Service (IDS)

* International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS)

* International Geodynamics and Earth Tide

Earth tide (also known as solid-Earth tide, crustal tide, body tide, bodily tide or land tide) is the displacement of the solid earth's surface caused by the gravity of the Moon and Sun. Its main component has meter-level amplitude at periods of a ...

Service (IGETS)

* International Gravity Field

In physics, a gravitational field or gravitational acceleration field is a vector field used to explain the influences that a body extends into the space around itself. A gravitational field is used to explain gravitational phenomena, such as ...

Service (IGFS)

* International GNSS Service (IGS)

* International Laser Ranging Service (ILRS)

* International VLBI Service for Geodesy and Astrometry (IVS)

* International Service for the Geoid

The geoid ( ) is the shape that the ocean surface would take under the influence of the gravity of Earth, including gravitational attraction and Earth's rotation, if other influences such as winds and tides were absent. This surface is exte ...

(ISG)

* Permanent Service for Mean Sea Level (PSMSL)

The Global Geodetic Observing System (GGOS) is the observing arm of the IAG that focuses on proving the geodetic infrastructure to measure changes in the earth's shape, rotation and mass distribution.

The International GNSS Service (IGS), part of GGOS, archives and processes GNSS data from around the world. IGS data is used in the 2021 reference frame (G2139) of WGS84.

Journal

IAG sponsors the ''Journal of Geodesy

The ''Journal of Geodesy'' is an academic journal about geodesy published by Springer on behalf of the International Association of Geodesy (IAG). It is the merger and continuation of ''Bulletin Géodésique'' and ''manuscripta geodaetica'' (both ...

'', published by Springer.

Awards

The IAG's awards for outstanding achievement in geodesy include (See Tables 9, 10, & 11.) the Guy Bomford Prize (inaugurated in 1975), the Levallois Medal (inaugurated in 1979), and the IAG Young Author's Award (inaugurated in 1993).See also

* Arc measurement of Delambre and Méchain * Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero – president of the International Geodetic Association and 1st president of theInternational Committee for Weights and Measures

The General Conference on Weights and Measures (abbreviated CGPM from the ) is the supreme authority of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM), the intergovernmental organization established in 1875 under the terms of the Metre C ...

* Johann Jacob Baeyer – founder of the ''Mitteleuropaïsche Gradmessung''

* History of geodesy

* History of the metre

During the French Revolution, the traditional units of measure were to be replaced by consistent measures based on natural phenomena. As a base unit of length, scientists had favoured the seconds pendulum (a pendulum with a half-period of ...

* International Bureau of Weights and Measures

The International Bureau of Weights and Measures (, BIPM) is an List of intergovernmental organizations, intergovernmental organisation, through which its 64 member-states act on measurement standards in areas including chemistry, ionising radi ...

* International Geodetic Student Organisation

* Metre Convention

The Metre Convention (), also known as the Treaty of the Metre, is an international treaty that was signed in Paris on 20 May 1875 by representatives of 17 nations: Argentina, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, France, German Empire, Ge ...

* Seconds pendulum

A seconds pendulum is a pendulum whose period is precisely two seconds; one second for a swing in one direction and one second for the return swing, a frequency of 0.5 Hz.

Principles

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a pivot so tha ...

References

Sources

*Further reading

*IUGG Report

(2012) pg 47-50

IAG History: Photos of the Presidents and Secretaries

''Terrestrial Reference Frames - Connecting the World through Geodesy''

(2023) GGOS short video {{authority control International geodesy organizations International scientific organizations International organisations based in Germany Scientific organizations established in 1940 Earth sciences societies International geographic data and information organizations