innate immune response on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The innate immune system or nonspecific immune system is one of the two main immunity strategies in

The innate immune system or nonspecific immune system is one of the two main immunity strategies in

White blood cells (WBCs) are also known as

White blood cells (WBCs) are also known as

Neutrophils, along with

Neutrophils, along with

Innate Immune System Animation

XVIVO Scientific Animation {{Use dmy dates, date=August 2016 Immune system Insect immunity

The innate immune system or nonspecific immune system is one of the two main immunity strategies in

The innate immune system or nonspecific immune system is one of the two main immunity strategies in vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s (the other being the adaptive immune system

The adaptive immune system (AIS), also known as the acquired immune system, or specific immune system is a subsystem of the immune system that is composed of specialized cells, organs, and processes that eliminate pathogens specifically. The ac ...

). The innate immune system is an alternate defense strategy and is the dominant immune system response found in plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s, fungi

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one ...

, prokaryote

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a unicellular organism, single-celled organism whose cell (biology), cell lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Gree ...

s, and invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s (see Beyond vertebrates)..

The major functions of the innate immune system are to:

* recruit immune cells to infection sites by producing chemical factors, including chemical mediators called cytokine

Cytokines () are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling.

Cytokines are produced by a broad range of cells, including immune cells like macrophages, B cell, B lymphocytes, T cell, T lymphocytes ...

s

* activate the complement cascade to identify bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

, activate cells, and promote clearance of antibody complexes or dead cells

* identify and remove foreign substances present in organs, tissues, blood and lymph

Lymph () is the fluid that flows through the lymphatic system, a system composed of lymph vessels (channels) and intervening lymph nodes whose function, like the venous system, is to return fluid from the tissues to be recirculated. At the ori ...

, by specialized white blood cell

White blood cells (scientific name leukocytes), also called immune cells or immunocytes, are cells of the immune system that are involved in protecting the body against both infectious disease and foreign entities. White blood cells are genera ...

s

* activate the adaptive immune system

The adaptive immune system (AIS), also known as the acquired immune system, or specific immune system is a subsystem of the immune system that is composed of specialized cells, organs, and processes that eliminate pathogens specifically. The ac ...

through antigen presentation

Antigen presentation is a vital immune process that is essential for T cell immune response triggering. Because T cells recognize only fragmented antigens displayed on cell surfaces, antigen processing must occur before the antigen fragment can ...

* act as a physical and chemical barrier to infectious agents; via physical measures such as skin and mucus, and chemical measures such as clotting factors and host defence peptides.

Anatomical barriers

Anatomical barriers include physical, chemical and biological barriers. The epithelial surfaces form a physical barrier that is impermeable to most infectious agents, acting as the first line of defense against invading organisms.Desquamation

Desquamation, or peeling skin, is the shedding of dead cells from the outermost layer of skin.

The term is .

Physiologic desquamation

Keratinocytes are the predominant cells of the epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin. Living keratin ...

(shedding) of skin epithelium also helps remove bacteria and other infectious agents that have adhered to the epithelial surface. Lack of blood vessels, the inability of the epidermis to retain moisture, and the presence of sebaceous gland

A sebaceous gland or oil gland is a microscopic exocrine gland in the skin that opens into a hair follicle to secrete an oily or waxy matter, called sebum, which lubricates the hair and skin of mammals. In humans, sebaceous glands occur in ...

s in the dermis, produces an environment unsuitable for the survival of microbes

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic size, which may exist in its single-celled form or as a colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen microbial life was suspected from antiquity, with an early attestation in ...

. In the gastrointestinal and respiratory tract

The respiratory tract is the subdivision of the respiratory system involved with the process of conducting air to the alveoli for the purposes of gas exchange in mammals. The respiratory tract is lined with respiratory epithelium as respirato ...

, movement due to peristalsis or cilia, respectively, helps remove infectious agents. Also, mucus

Mucus (, ) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both Serous fluid, serous and muc ...

traps infectious agents. Gut flora

Gut microbiota, gut microbiome, or gut flora are the microorganisms, including bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses, that live in the digestive tracts of animals. The gastrointestinal metagenome is the aggregate of all the genomes of the g ...

can prevent the colonization of pathogenic bacteria by secreting toxic substances or by competing with pathogenic bacteria for nutrients or cell surface attachment sites. The flushing action of tears and saliva helps prevent infection of the eyes and mouth.

Inflammation

Inflammation

Inflammation (from ) is part of the biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants. The five cardinal signs are heat, pain, redness, swelling, and loss of function (Latin ''calor'', '' ...

is one of the first responses of the immune system to infection or irritation. Inflammation is stimulated by chemical factors released by injured cells. It establishes a physical barrier against the spread of infection and promotes healing of any damaged tissue following pathogen clearance.

The process of acute inflammation is initiated by cells already present in all tissues, mainly resident macrophages

Macrophages (; abbreviated MPhi, φ, MΦ or MP) are a type of white blood cell of the innate immune system that engulf and digest pathogens, such as cancer cells, microbes, cellular debris and foreign substances, which do not have proteins that ...

, dendritic cells

A dendritic cell (DC) is an antigen-presenting cell (also known as an ''accessory cell'') of the mammalian immune system. A DC's main function is to process antigen material and present it on the cell surface to the T cells of the immune system ...

, histiocytes, Kupffer cells, and mast cells

A mast cell (also known as a mastocyte or a labrocyte) is a resident cell of connective tissue that contains many granules rich in histamine and heparin. Specifically, it is a type of granulocyte derived from the myeloid stem cell that is a ...

. These cells present receptors contained on the surface or within the cell, named '' pattern recognition receptors'' (PRRs), which recognize molecules that are broadly shared by pathogen

In biology, a pathogen (, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of"), in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a Germ theory of d ...

s but distinguishable from host molecules, collectively referred to as pathogen-associated molecular pattern

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are small molecular motifs conserved within a class of microbes, but not present in the host. They are recognized by toll-like receptors (TLRs) and other pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) in both p ...

s (PAMPs). At the onset of an infection, burn, or other injuries, these cells undergo activation (one of their PRRs recognizes a PAMP) and release inflammatory mediators, like cytokines and chemokines, which are responsible for the clinical signs of inflammation. PRR activation and its cellular consequences have been well-characterized as methods of inflammatory cell death, which include pyroptosis, necroptosis, and PANoptosis. These cell death pathways help clear infected or aberrant cells and release cellular contents and inflammatory mediators.

Chemical factors produced during inflammation (histamine

Histamine is an organic nitrogenous compound involved in local immune responses communication, as well as regulating physiological functions in the gut and acting as a neurotransmitter for the brain, spinal cord, and uterus. Discovered in 19 ...

, bradykinin

Bradykinin (BK) (from Greek ''brady-'' 'slow' + ''-kinin'', ''kīn(eîn)'' 'to move') is a peptide that promotes inflammation. It causes arterioles to dilate (enlarge) via the release of prostacyclin, nitric oxide, and endothelium-derived hyperpo ...

, serotonin

Serotonin (), also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), is a monoamine neurotransmitter with a wide range of functions in both the central nervous system (CNS) and also peripheral tissues. It is involved in mood, cognition, reward, learning, ...

, leukotriene

Leukotrienes are a family of eicosanoid inflammation, inflammatory mediators produced in leukocytes by the redox, oxidation of arachidonic acid (AA) and the essential fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) by the enzyme arachidonate 5-lipoxyg ...

s, and prostaglandin

Prostaglandins (PG) are a group of physiology, physiologically active lipid compounds called eicosanoids that have diverse hormone-like effects in animals. Prostaglandins have been found in almost every Tissue (biology), tissue in humans and ot ...

s) sensitize pain receptors, cause local vasodilation

Vasodilation, also known as vasorelaxation, is the widening of blood vessels. It results from relaxation of smooth muscle cells within the vessel walls, in particular in the large veins, large arteries, and smaller arterioles. Blood vessel wa ...

of the blood vessel

Blood vessels are the tubular structures of a circulatory system that transport blood throughout many Animal, animals’ bodies. Blood vessels transport blood cells, nutrients, and oxygen to most of the Tissue (biology), tissues of a Body (bi ...

s, and attract phagocytes, especially neutrophils. Neutrophils then trigger other parts of the immune system by releasing factors that summon additional leukocytes and lymphocytes. Cytokines

Cytokines () are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling.

Cytokines are produced by a broad range of cells, including immune cells like macrophages, B cell, B lymphocytes, T cell, T lymphocytes ...

produced by macrophages and other cells of the innate immune system mediate the inflammatory response. These cytokines include TNF, HMGB1

High mobility group box 1 protein, also known as high-mobility group protein 1 (HMG-1) and amphoterin, is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''HMGB1'' gene.

HMG-1 belongs to the high mobility group and contains a HMG-box domain.

Funct ...

, and IL-1.

The inflammatory response is characterized by the following symptoms:

* redness of the skin, due to locally increased blood circulation;

* heat, either increased local temperature, such as a warm feeling around a localized infection, or a systemic fever

Fever or pyrexia in humans is a symptom of an anti-infection defense mechanism that appears with Human body temperature, body temperature exceeding the normal range caused by an increase in the body's temperature Human body temperature#Fever, s ...

;

* swelling of affected tissues, such as the upper throat during the common cold

The common cold, or the cold, is a virus, viral infectious disease of the upper respiratory tract that primarily affects the Respiratory epithelium, respiratory mucosa of the human nose, nose, throat, Paranasal sinuses, sinuses, and larynx. ...

or joints affected by rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a long-term autoimmune disorder that primarily affects synovial joint, joints. It typically results in warm, swollen, and painful joints. Pain and stiffness often worsen following rest. Most commonly, the wrist and h ...

;

* increased production of mucus, which can cause symptoms like a runny nose or a productive cough

A cough is a sudden expulsion of air through the large breathing passages which can help clear them of fluids, irritants, foreign particles and microbes. As a protective reflex, coughing can be repetitive with the cough reflex following three ...

;

* pain, either local pain, such as painful joints or a sore throat

Sore throat, also known as throat pain, is pain or irritation of the throat. The majority of sore throats are caused by a virus, for which antibiotics are not helpful.

For sore throat caused by bacteria (GAS), treatment with antibiotics may hel ...

, or affecting the whole body, such as body aches; and

* possible dysfunction of involved organs/tissues.

Complement system

Thecomplement system

The complement system, also known as complement cascade, is a part of the humoral, innate immune system and enhances (complements) the ability of antibodies and phagocytic cells to clear microbes and damaged cells from an organism, promote inf ...

is a biochemical cascade

A biochemical cascade, also known as a signaling cascade or signaling pathway, is a series of chemical reactions that occur within a biological cell when initiated by a stimulus. This stimulus, known as a first messenger, acts on a receptor that ...

of the immune system that helps, or "complements", the ability of antibodies to clear pathogens or mark them for destruction by other cells. The cascade is composed of many plasma proteins, synthesized in the liver

The liver is a major metabolic organ (anatomy), organ exclusively found in vertebrates, which performs many essential biological Function (biology), functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of var ...

, primarily by hepatocytes. The proteins work together to:

* trigger the recruitment of inflammatory cells

* "tag" pathogens for destruction by other cells by ''opsonizing'', or coating, the surface of the pathogen

* form holes in the plasma membrane of the pathogen, resulting in cytolysis

Cytolysis, or osmotic lysis, occurs when a cell bursts due to an osmotic imbalance that has caused excess water to diffuse into the cell. Water can enter the cell by diffusion through the cell membrane or through selective membrane channels ...

of the pathogen cell, causing its death

* rid the body of neutralised antigen-antibody complexes.

The three different complement systems are classical, alternative and lectin.

* Classical: starts when antibody binds to bacteria

* Alternative: starts "spontaneously"

* Lectin: starts when lectin

Lectins are carbohydrate-binding proteins that are highly specific for sugar Moiety (chemistry), groups that are part of other molecules, so cause agglutination (biology), agglutination of particular cells or precipitation of glycoconjugates an ...

s bind to mannose

Mannose is a sugar with the formula , which sometimes is abbreviated Man. It is one of the monomers of the aldohexose series of carbohydrates. It is a C-2 epimer of glucose. Mannose is important in human metabolism, especially in the glycosylatio ...

on bacteria

Elements of the complement cascade can be found in many non-mammalian species including plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s, bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s, fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

, and some species of invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s.

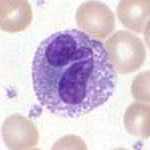

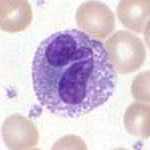

White blood cells

White blood cells (WBCs) are also known as

White blood cells (WBCs) are also known as leukocyte

White blood cells (scientific name leukocytes), also called immune cells or immunocytes, are cells of the immune system that are involved in protecting the body against both infectious disease and foreign entities. White blood cells are genera ...

s. Most leukocytes differ from other cells of the body in that they are not tightly associated with a particular organ or tissue; thus, their function is similar to that of independent, single-cell organisms. Most leukocytes are able to move freely and interact with and capture cellular debris, foreign particles, and invading microorganisms (although macrophage

Macrophages (; abbreviated MPhi, φ, MΦ or MP) are a type of white blood cell of the innate immune system that engulf and digest pathogens, such as cancer cells, microbes, cellular debris and foreign substances, which do not have proteins that ...

s, mast cell

A mast cell (also known as a mastocyte or a labrocyte) is a resident cell of connective tissue that contains many granules rich in histamine and heparin. Specifically, it is a type of granulocyte derived from the myeloid stem cell that is a p ...

s, and dendritic cell

A dendritic cell (DC) is an antigen-presenting cell (also known as an ''accessory cell'') of the mammalian immune system. A DC's main function is to process antigen material and present it on the cell surface to the T cells of the immune system ...

s are less mobile). Unlike many other cells, most innate immune leukocytes cannot divide or reproduce on their own, but are the products of multipotent hematopoietic stem cell

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are the stem cells that give rise to other blood cells. This process is called haematopoiesis. In vertebrates, the first definitive HSCs arise from the ventral endothelial wall of the embryonic aorta within the ...

s present in bone marrow

Bone marrow is a semi-solid biological tissue, tissue found within the Spongy bone, spongy (also known as cancellous) portions of bones. In birds and mammals, bone marrow is the primary site of new blood cell production (or haematopoiesis). It i ...

.

The innate leukocytes include: natural killer cells, mast cells, eosinophils

Eosinophils, sometimes called eosinophiles or, less commonly, acidophils, are a variety of white blood cells and one of the immune system components responsible for combating multicellular parasites and certain infections in vertebrates. Along wi ...

, basophils; and the phagocytic cells include macrophages

Macrophages (; abbreviated MPhi, φ, MΦ or MP) are a type of white blood cell of the innate immune system that engulf and digest pathogens, such as cancer cells, microbes, cellular debris and foreign substances, which do not have proteins that ...

, neutrophils

Neutrophils are a type of phagocytic white blood cell and part of innate immunity. More specifically, they form the most abundant type of granulocytes and make up 40% to 70% of all white blood cells in humans. Their functions vary in different ...

, and dendritic cells, and function within the immune system by identifying and eliminating pathogens that might cause infection.

Mast cells

Mast cells are a type of innate immune cell that resides in connective tissue and in mucous membranes. They are intimately associated with wound healing and defense against pathogens, but are also often associated withallergy

Allergies, also known as allergic diseases, are various conditions caused by hypersensitivity of the immune system to typically harmless substances in the environment. These diseases include Allergic rhinitis, hay fever, Food allergy, food al ...

and anaphylaxis

Anaphylaxis (Greek: 'up' + 'guarding') is a serious, potentially fatal allergic reaction and medical emergency that is rapid in onset and requires immediate medical attention regardless of the use of emergency medication on site. It typicall ...

. When activated, mast cells rapidly release characteristic granules, rich in histamine

Histamine is an organic nitrogenous compound involved in local immune responses communication, as well as regulating physiological functions in the gut and acting as a neurotransmitter for the brain, spinal cord, and uterus. Discovered in 19 ...

and heparin

Heparin, also known as unfractionated heparin (UFH), is a medication and naturally occurring glycosaminoglycan. Heparin is a blood anticoagulant that increases the activity of antithrombin. It is used in the treatment of myocardial infarction, ...

, along with various hormonal mediators and chemokine

Chemokines (), or chemotactic cytokines, are a family of small cytokines or signaling proteins secreted by cells that induce directional movement of leukocytes, as well as other cell types, including endothelial and epithelial cells. In addit ...

s, or chemotactic cytokine

Cytokines () are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling.

Cytokines are produced by a broad range of cells, including immune cells like macrophages, B cell, B lymphocytes, T cell, T lymphocytes ...

s into the environment. Histamine dilates blood vessel

Blood vessels are the tubular structures of a circulatory system that transport blood throughout many Animal, animals’ bodies. Blood vessels transport blood cells, nutrients, and oxygen to most of the Tissue (biology), tissues of a Body (bi ...

s, causing the characteristic signs of inflammation, and recruits neutrophils and macrophages.

Phagocytes

The word 'phagocyte' literally means 'eating cell'. These are immune cells that engulf, or ' phagocytose', pathogens or particles. To engulf a particle or pathogen, a phagocyte extends portions of itsplasma membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

, wrapping the membrane around the particle until it is enveloped (i.e., the particle is now inside the cell). Once inside the cell, the invading pathogen is contained inside a phagosome

In cell biology, a phagosome is a vesicle formed around a particle engulfed by a phagocyte via phagocytosis. Professional phagocytes include macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells (DCs).

A phagosome is formed by the fusion of the cel ...

, which merges with a lysosome

A lysosome () is a membrane-bound organelle that is found in all mammalian cells, with the exception of red blood cells (erythrocytes). There are normally hundreds of lysosomes in the cytosol, where they function as the cell’s degradation cent ...

. The lysosome contains enzymes and acids that kill and digest the particle or organism. In general, phagocytes patrol the body searching for pathogens, but are also able to react to a group of highly specialized molecular signals produced by other cells, called cytokines

Cytokines () are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling.

Cytokines are produced by a broad range of cells, including immune cells like macrophages, B cell, B lymphocytes, T cell, T lymphocytes ...

. The phagocytic cells of the immune system include macrophages, neutrophils

Neutrophils are a type of phagocytic white blood cell and part of innate immunity. More specifically, they form the most abundant type of granulocytes and make up 40% to 70% of all white blood cells in humans. Their functions vary in different ...

, and dendritic cells.

Phagocytosis of the hosts' own cells is common as part of regular tissue development and maintenance. When host cells die, either by apoptosis

Apoptosis (from ) is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms and in some eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms such as yeast. Biochemistry, Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (Morphology (biol ...

or by cell injury due to an infection, phagocytic cells are responsible for their removal from the affected site. By helping to remove dead cells preceding growth and development of new healthy cells, phagocytosis is an important part of the healing process following tissue injury.

Macrophages

Macrophages, from the Greek, meaning "large eaters", are large phagocytic leukocytes, which are able to move beyond the vascular system by migrating through the walls ofcapillary

A capillary is a small blood vessel, from 5 to 10 micrometres in diameter, and is part of the microcirculation system. Capillaries are microvessels and the smallest blood vessels in the body. They are composed of only the tunica intima (the inn ...

vessels and entering the areas between cells in pursuit of invading pathogens. In tissues, organ-specific macrophages are differentiated from phagocytic cells present in the blood called monocyte

Monocytes are a type of leukocyte or white blood cell. They are the largest type of leukocyte in blood and can differentiate into macrophages and monocyte-derived dendritic cells. As a part of the vertebrate innate immune system monocytes also ...

s. Macrophages are the most efficient phagocytes and can phagocytose substantial numbers of bacteria or other cells or microbes. The binding of bacterial molecules to receptors on the surface of a macrophage triggers it to engulf and destroy the bacteria through the generation of a "respiratory burst

Respiratory burst (or oxidative burst) is the rapid release of the reactive oxygen species (ROS), superoxide anion () and hydrogen peroxide (), from different cell types.

This is usually utilised for mammalian immunological defence, but also pl ...

", causing the release of reactive oxygen species

In chemistry and biology, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly Reactivity (chemistry), reactive chemicals formed from diatomic oxygen (), water, and hydrogen peroxide. Some prominent ROS are hydroperoxide (H2O2), superoxide (O2−), hydroxyl ...

. Pathogens also stimulate the macrophage to produce chemokines, which summon other cells to the site of infection. There are also resident macrophages in many tissues including mucous membranes, liver, lungs, and skin (where they are often called Langerhans cell

A Langerhans cell (LC) is a tissue-resident macrophage of the skin once thought to be a resident dendritic cell. These cells contain organelles called Birbeck granules. They are present in all layers of the epidermis and are most prominent in t ...

s).

Neutrophils

Neutrophils, along with

Neutrophils, along with eosinophils

Eosinophils, sometimes called eosinophiles or, less commonly, acidophils, are a variety of white blood cells and one of the immune system components responsible for combating multicellular parasites and certain infections in vertebrates. Along wi ...

and basophils, are known as granulocyte

Granulocytes are cells in the innate immune system characterized by the presence of specific granules in their cytoplasm. Such granules distinguish them from the various agranulocytes. All myeloblastic granulocytes are polymorphonuclear, that i ...

s due to the presence of granules in their cytoplasm, or as polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) due to their distinctive lobed nuclei. Neutrophil granules contain a variety of toxic substances that kill or inhibit growth of bacteria and fungi. Similar to macrophages, neutrophils attack pathogens by activating a respiratory burst

Respiratory burst (or oxidative burst) is the rapid release of the reactive oxygen species (ROS), superoxide anion () and hydrogen peroxide (), from different cell types.

This is usually utilised for mammalian immunological defence, but also pl ...

. The main products of the neutrophil respiratory burst are strong oxidizing agent

An oxidizing agent (also known as an oxidant, oxidizer, electron recipient, or electron acceptor) is a substance in a redox chemical reaction that gains or " accepts"/"receives" an electron from a (called the , , or ''electron donor''). In ot ...

s including hydrogen peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide is a chemical compound with the formula . In its pure form, it is a very pale blue liquid that is slightly more viscosity, viscous than Properties of water, water. It is used as an oxidizer, bleaching agent, and antiseptic, usua ...

, free oxygen radicals and hypochlorite

In chemistry, hypochlorite, or chloroxide is an oxyanion with the chemical formula ClO−. It combines with a number of cations to form hypochlorite salts. Common examples include sodium hypochlorite (household bleach) and calcium hypochlorite ...

. Neutrophils are the most abundant type of phagocyte, normally representing 50–60% of the total circulating leukocytes, and are usually the first cells to arrive at the site of an infection. The bone marrow of a normal healthy adult produces more than 100 billion neutrophils per day, and more than 10 times that many per day during acute inflammation.

Dendritic cells

Dendritic cells (DCs) are phagocytic cells present in tissues that are in contact with the external environment, mainly theskin

Skin is the layer of usually soft, flexible outer tissue covering the body of a vertebrate animal, with three main functions: protection, regulation, and sensation.

Other animal coverings, such as the arthropod exoskeleton, have different ...

and the inner mucosal lining of the nose

A nose is a sensory organ and respiratory structure in vertebrates. It consists of a nasal cavity inside the head, and an external nose on the face. The external nose houses the nostrils, or nares, a pair of tubes providing airflow through the ...

, lung

The lungs are the primary Organ (biology), organs of the respiratory system in many animals, including humans. In mammals and most other tetrapods, two lungs are located near the Vertebral column, backbone on either side of the heart. Their ...

s, stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the upper gastrointestinal tract of Human, humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The Ancient Greek name for the stomach is ''gaster'' which is used as ''gastric'' in medical t ...

, and intestine

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascular system. T ...

s. They are named for their resemblance to neuronal

A neuron (American English), neurone (British English), or nerve cell, is an excitable cell that fires electric signals called action potentials across a neural network in the nervous system. They are located in the nervous system and help to ...

dendrite

A dendrite (from Ancient Greek language, Greek δένδρον ''déndron'', "tree") or dendron is a branched cytoplasmic process that extends from a nerve cell that propagates the neurotransmission, electrochemical stimulation received from oth ...

s, but dendritic cells are not connected to the nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the complex system, highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its behavior, actions and sense, sensory information by transmitting action potential, signals to and from different parts of its body. Th ...

. Dendritic cells are very important in the process of antigen presentation

Antigen presentation is a vital immune process that is essential for T cell immune response triggering. Because T cells recognize only fragmented antigens displayed on cell surfaces, antigen processing must occur before the antigen fragment can ...

, and serve as a link between the innate and adaptive immune system

The adaptive immune system (AIS), also known as the acquired immune system, or specific immune system is a subsystem of the immune system that is composed of specialized cells, organs, and processes that eliminate pathogens specifically. The ac ...

s.

Basophils and eosinophils

Basophils and eosinophils are cells related to the neutrophil. When activated by a pathogen encounter,histamine

Histamine is an organic nitrogenous compound involved in local immune responses communication, as well as regulating physiological functions in the gut and acting as a neurotransmitter for the brain, spinal cord, and uterus. Discovered in 19 ...

-releasing basophils are important in the defense against parasite

Parasitism is a Symbiosis, close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives (at least some of the time) on or inside another organism, the Host (biology), host, causing it some harm, and is Adaptation, adapted str ...

s and play a role in allergic reactions

Allergies, also known as allergic diseases, are various conditions caused by hypersensitivity of the immune system to typically harmless substances in the environment. These diseases include hay fever, food allergies, atopic dermatitis, alle ...

, such as asthma

Asthma is a common long-term inflammatory disease of the airways of the lungs. It is characterized by variable and recurring symptoms, reversible airflow obstruction, and easily triggered bronchospasms. Symptoms include episodes of wh ...

. Upon activation, eosinophils secrete a range of highly toxic

Toxicity is the degree to which a chemical substance or a particular mixture of substances can damage an organism. Toxicity can refer to the effect on a whole organism, such as an animal, bacterium, or plant, as well as the effect on a subst ...

proteins and free radicals that are highly effective in killing parasites, but may also damage tissue during an allergic reaction. Activation and release of toxins by eosinophils are, therefore, tightly regulated to prevent any inappropriate tissue destruction.

Natural killer cells

Natural killer cells (NK cells) do not directly attack invading microbes. Rather, NK cells destroy compromised host cells, such astumor

A neoplasm () is a type of abnormal and excessive growth of tissue. The process that occurs to form or produce a neoplasm is called neoplasia. The growth of a neoplasm is uncoordinated with that of the normal surrounding tissue, and persists ...

cells or virus-infected cells, recognizing such cells by a condition known as "missing self". This term describes cells with abnormally low levels of a cell-surface marker called MHC I (major histocompatibility complex

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is a large Locus (genetics), locus on vertebrate DNA containing a set of closely linked polymorphic genes that code for Cell (biology), cell surface proteins essential for the adaptive immune system. The ...

) - a situation that can arise in viral infections of host cells. They were named "natural killer" because of the initial notion that they do not require activation in order to kill cells that are "missing self". The MHC makeup on the surface of damaged cells is altered and the NK cells become activated by recognizing this. Normal body cells are not recognized and attacked by NK cells because they express intact self MHC antigens. Those MHC antigens are recognized by killer cell immunoglobulin

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as pathogenic bacteria, bacteria and viruses, includin ...

receptors (KIR) that slow the reaction of NK cells. The NK-92 cell line does not express KIR and is developed for tumor therapy.

γδ T cells

Like other 'unconventional' T cell subsets bearing invariantT cell receptor

The T-cell receptor (TCR) is a protein complex, located on the surface of T cells (also called T lymphocytes). They are responsible for recognizing fragments of antigen as peptides bound to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules. ...

s (TCRs), such as CD1d

CD1D is the human gene that encodes the protein CD1d, a member of the CD1 (cluster of differentiation 1) family of glycoproteins expressed on the surface of various human antigen-presenting cells. They are non-classical Major histocompatibility c ...

-restricted Natural Killer T cells, γδ T cells exhibit characteristics that place them at the border between innate and adaptive immunity. γδ T cells may be considered a component of adaptive immunity

The adaptive immune system (AIS), also known as the acquired immune system, or specific immune system is a subsystem of the immune system that is composed of specialized cells, organs, and processes that eliminate pathogens specifically. The ac ...

in that they rearrange TCR genes to produce junctional diversity and develop a memory phenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology (physical form and structure), its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological propert ...

. The various subsets may be considered part of the innate immune system where a restricted TCR or NK receptors may be used as a pattern recognition receptor. For example, according to this paradigm, large numbers of Vγ9/Vδ2 T cells respond within hours to common molecules produced by microbes, and highly restricted intraepithelial Vδ1 T cells will respond to stressed epithelial cells.

Other vertebrate mechanisms

Thecoagulation system

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a blood clot. It results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The process of coagulation ...

overlaps with the immune system. Some products of the coagulation system can contribute to non-specific defenses via their ability to increase vascular permeability

Vascular permeability, often in the form of capillary permeability or microvascular permeability, characterizes the permeability of a blood vessel wall–in other words, the blood vessel wall's capacity to allow for the flow of small molecules ( ...

and act as chemotactic agent

Chemotaxis (from ''chemical substance, chemo-'' + ''taxis'') is the movement of an organism or entity in response to a chemical stimulus. Somatic cells, bacteria, and other single-cell organism, single-cell or multicellular organisms direct thei ...

s for phagocytic cells. In addition, some of the products of the coagulation system are directly antimicrobial

An antimicrobial is an agent that kills microorganisms (microbicide) or stops their growth (bacteriostatic agent). Antimicrobial medicines can be grouped according to the microorganisms they are used to treat. For example, antibiotics are used aga ...

. For example, beta-lysine, a protein produced by platelets during coagulation

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a thrombus, blood clot. It results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The process of co ...

, can cause lysis

Lysis ( ; from Greek 'loosening') is the breaking down of the membrane of a cell, often by viral, enzymic, or osmotic (that is, "lytic" ) mechanisms that compromise its integrity. A fluid containing the contents of lysed cells is called a ...

of many Gram-positive bacteria

In bacteriology, gram-positive bacteria are bacteria that give a positive result in the Gram stain test, which is traditionally used to quickly classify bacteria into two broad categories according to their type of cell wall.

The Gram stain ...

by acting as a cationic detergent. Many acute-phase protein

Acute-phase proteins (APPs) are a class of proteins whose concentrations in blood plasma either increase (positive acute-phase proteins) or decrease (negative acute-phase proteins) in response to inflammation. This response is called the ''acute-p ...

s of inflammation

Inflammation (from ) is part of the biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants. The five cardinal signs are heat, pain, redness, swelling, and loss of function (Latin ''calor'', '' ...

are involved in the coagulation system.

Increased levels of lactoferrin

Lactoferrin (LF), also known as lactotransferrin (LTF), is a multifunctional protein of the transferrin family. Lactoferrin is a globular proteins, globular glycoprotein with a molecular mass of about 80 Atomic mass unit, kDa that is widely repre ...

and transferrin

Transferrins are glycoproteins found in vertebrates which bind and consequently mediate the transport of iron (Fe) through blood plasma. They are produced in the liver and contain binding sites for two Iron(III), Fe3+ ions. Human transferrin is ...

inhibit bacterial growth by binding iron, an essential bacterial nutrient.

Neural regulation

The innate immune response to infectious and sterile injury is modulated by neural circuits that control cytokine production period. The inflammatory reflex is a prototypical neural circuit that controls cytokine production in thespleen

The spleen (, from Ancient Greek '' σπλήν'', splḗn) is an organ (biology), organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter.

The spleen plays important roles in reg ...

. Action potentials transmitted via the vagus nerve

The vagus nerve, also known as the tenth cranial nerve (CN X), plays a crucial role in the autonomic nervous system, which is responsible for regulating involuntary functions within the human body. This nerve carries both sensory and motor fibe ...

to the spleen mediate the release of acetylcholine

Acetylcholine (ACh) is an organic compound that functions in the brain and body of many types of animals (including humans) as a neurotransmitter. Its name is derived from its chemical structure: it is an ester of acetic acid and choline. Par ...

, the neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a signaling molecule secreted by a neuron to affect another cell across a Chemical synapse, synapse. The cell receiving the signal, or target cell, may be another neuron, but could also be a gland or muscle cell.

Neurotra ...

that inhibits cytokine release by interacting with alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors ( CHRNA7) expressed on cytokine-producing cells. The motor arc of the inflammatory reflex is termed the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway.

Pathogen-specificity

The parts of the innate immune system display specificity for different pathogens.Immune evasion

Innate immune system cells prevent free growth of microorganisms within the body, but many pathogens have evolved mechanisms to evade it. One strategy is intracellular replication, as practised by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis

''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (M. tb), also known as Koch's bacillus, is a species of pathogenic bacteria in the family Mycobacteriaceae and the causative agent of tuberculosis.

First discovered in 1882 by Robert Koch, ''M. tuberculosis'' ha ...

'', or wearing a protective capsule, which prevents lysis by complement and by phagocytes, as in ''Salmonella

''Salmonella'' is a genus of bacillus (shape), rod-shaped, (bacillus) Gram-negative bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae. The two known species of ''Salmonella'' are ''Salmonella enterica'' and ''Salmonella bongori''. ''S. enterica'' ...

''. ''Bacteroides

''Bacteroides'' is a genus of Gram-negative, obligate anaerobic bacteria. ''Bacteroides'' species are non endospore–forming bacilli, and may be either motile or nonmotile, depending on the species. The DNA base composition is 40–48% GC. Un ...

'' species are normally mutualistic bacteria, making up a substantial portion of the mammalian gastrointestinal flora. Species such as '' B. fragilis'' are opportunistic pathogens, causing infections of the peritoneal cavity

The peritoneal cavity is a potential space located between the two layers of the peritoneum—the parietal peritoneum, the serous membrane that lines the abdominal wall, and visceral peritoneum, which surrounds the internal organs. While situated ...

. They inhibit phagocytosis by affecting the phagocytes receptors used to engulf bacteria. They may also mimic host cells so the immune system does not recognize them as foreign. ''Staphylococcus aureus

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is a Gram-positive spherically shaped bacterium, a member of the Bacillota, and is a usual member of the microbiota of the body, frequently found in the upper respiratory tract and on the skin. It is often posi ...

'' inhibits the ability of the phagocyte to respond to chemokine signals. '' M. tuberculosis'', ''Streptococcus pyogenes

''Streptococcus pyogenes'' is a species of Gram-positive, aerotolerant bacteria in the genus '' Streptococcus''. These bacteria are extracellular, and made up of non-motile and non-sporing cocci (round cells) that tend to link in chains. They ...

'', and ''Bacillus anthracis

''Bacillus anthracis'' is a gram-positive and rod-shaped bacterium that causes anthrax, a deadly disease to livestock and, occasionally, to humans. It is the only permanent (obligate) pathogen within the genus ''Bacillus''. Its infection is a ty ...

'' utilize mechanisms that directly kill the phagocyte.

Bacteria and fungi may form complex biofilm

A biofilm is a Syntrophy, syntrophic Microbial consortium, community of microorganisms in which cell (biology), cells cell adhesion, stick to each other and often also to a surface. These adherent cells become embedded within a slimy ext ...

s, protecting them from immune cells and proteins; biofilms are present in the chronic ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa

''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'' is a common Bacterial capsule, encapsulated, Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-negative, Aerobic organism, aerobic–facultative anaerobe, facultatively anaerobic, Bacillus (shape), rod-shaped bacteria, bacterium that can c ...

'' and '' Burkholderia cenocepacia'' infections characteristic of cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic disorder inherited in an autosomal recessive manner that impairs the normal clearance of Sputum, mucus from the lungs, which facilitates the colonization and infection of the lungs by bacteria, notably ''Staphy ...

.

Viruses

Type Iinterferon

Interferons (IFNs, ) are a group of signaling proteins made and released by host cells in response to the presence of several viruses. In a typical scenario, a virus-infected cell will release interferons causing nearby cells to heighten ...

s (IFN), secreted mainly by dendritic cell

A dendritic cell (DC) is an antigen-presenting cell (also known as an ''accessory cell'') of the mammalian immune system. A DC's main function is to process antigen material and present it on the cell surface to the T cells of the immune system ...

s, play a central role in antiviral host defense and a cell's antiviral state. Viral components are recognized by different receptors: Toll-like receptor

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a class of proteins that play a key role in the innate immune system. They are single-pass membrane protein, single-spanning receptor (biochemistry), receptors usually expressed on sentinel cells such as macrophages ...

s are located in the endosomal membrane and recognize double-stranded RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

(dsRNA), MDA5 and RIG-I receptors are located in the cytoplasm and recognize long dsRNA and phosphate-containing dsRNA respectively. When the cytoplasmic

The cytoplasm describes all the material within a eukaryotic or prokaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, including the organelles and excluding the nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The material inside the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell and ...

receptors MDA5 and RIG-I

RIG-I (retinoic acid-inducible gene I) is a cytosolic pattern recognition receptor (PRR) that can mediate induction of a type-I interferon (IFN1) response. RIG-I is an essential molecule in the innate immune system for recognizing cells that ...

recognize a virus the conformation between the caspase-recruitment domain (CARD) and the CARD-containing adaptor MAVS changes. In parallel, when TLRs in the endocytic compartments recognize a virus the activation of the adaptor protein TRIF is induced. Both pathways converge in the recruitment and activation of the IKKε/TBK-1 complex, inducing dimerization of transcription factor

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription (genetics), transcription of genetics, genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding t ...

s IRF3 and IRF7, which are translocated in the nucleus, where they induce IFN production with the presence of a particular transcription factor and activate transcription factor 2. IFN is secreted through secretory vesicles, where it can activate receptors on both the cell it was released from (autocrine

Autocrine signaling is a form of cell signaling in which a cell secretes a hormone or chemical messenger (called the autocrine agent) that binds to autocrine receptors on that same cell, leading to changes in the cell. This can be contrasted with ...

) or nearby cells (paracrine). This induces hundreds of interferon-stimulated genes to be expressed. This leads to antiviral protein production, such as protein kinase R

Protein kinase RNA-activated also known as protein kinase R (PKR), interferon-induced, double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase, or eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2-alpha kinase 2 (EIF2AK2) is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by ...

, which inhibits viral protein synthesis, or the 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase family, which degrades viral RNA.

Some viruses evade this by producing molecules that interfere with IFN production. For example, the Influenza A

''Influenza A virus'' (''Alphainfluenzavirus influenzae'') or IAV is the only species of the genus ''Alphainfluenzavirus'' of the virus family '' Orthomyxoviridae''. It is a pathogen with strains that infect birds and some mammals, as well as c ...

virus produces NS1 protein, which can bind to host and viral RNA, interact with immune signaling proteins or block their activation by ubiquitin

Ubiquitin is a small (8.6 kDa) regulatory protein found in most tissues of eukaryotic organisms, i.e., it is found ''ubiquitously''. It was discovered in 1975 by Gideon Goldstein and further characterized throughout the late 1970s and 19 ...

ation, thus inhibiting type I IFN production. Influenza A also blocks protein kinase R activation and establishment of the antiviral state. The dengue virus also inhibits type I IFN production by blocking IRF-3 phosophorylation using NS2B3 protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalysis, catalyzes proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the formation of new protein products ...

complex.

Beyond vertebrates

Prokaryotes

Bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

(and perhaps other prokaryotic

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a single-celled organism whose cell lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'before', and (), meaning 'nut' ...

organisms), utilize a unique defense mechanism, called the restriction modification system

The restriction modification system (RM system) is found in bacteria and archaea, and provides a defense against foreign DNA, such as that borne by bacteriophages.

Bacteria have restriction enzymes, also called restriction endonucleases, which ...

to protect themselves from pathogens, such as bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a phage (), is a virus that infects and replicates within bacteria. The term is derived . Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that Capsid, encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome, and may have structu ...

s. In this system, bacteria produce enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s, called restriction endonuclease

A restriction enzyme, restriction endonuclease, REase, ENase or'' restrictase '' is an enzyme that cleaves DNA into fragments at or near specific recognition sites within molecules known as restriction sites. Restriction enzymes are one class o ...

s, that attack and destroy specific regions of the viral DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

of invading bacteriophages. Methylation

Methylation, in the chemistry, chemical sciences, is the addition of a methyl group on a substrate (chemistry), substrate, or the substitution of an atom (or group) by a methyl group. Methylation is a form of alkylation, with a methyl group replac ...

of the host's own DNA marks it as "self" and prevents it from being attacked by endonucleases. Restriction endonucleases and the restriction modification system exist exclusively in prokaryotes.

Invertebrates

Invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s do not possess lymphocytes or an antibody-based humoral immune system, and it is likely that a multicomponent, adaptive immune system arose with the first vertebrates. Nevertheless, invertebrates possess mechanisms that appear to be precursors of these aspects of vertebrate immunity. Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) are proteins used by nearly all organisms to identify molecules associated with microbial pathogens. TLRs are a major class of pattern recognition receptor, that exists in all coelomates (animals with a body-cavity), including humans. The complement system

The complement system, also known as complement cascade, is a part of the humoral, innate immune system and enhances (complements) the ability of antibodies and phagocytic cells to clear microbes and damaged cells from an organism, promote inf ...

exists in most life forms. Some invertebrates, including various insects, crab

Crabs are decapod crustaceans of the infraorder Brachyura (meaning "short tailed" in Greek language, Greek), which typically have a very short projecting tail-like abdomen#Arthropoda, abdomen, usually hidden entirely under the Thorax (arthropo ...

s, and worm

Worms are many different distantly related bilateria, bilateral animals that typically have a long cylindrical tube-like body, no limb (anatomy), limbs, and usually no eyes.

Worms vary in size from microscopic to over in length for marine ...

s utilize a modified form of the complement response known as the prophenoloxidase (proPO) system.

Antimicrobial peptides

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), also called host defence peptides (HDPs) are part of the innate immune response found among all classes of life. Fundamental differences exist between Prokaryote, prokaryotic and eukaryota, eukaryotic cells that may ...

are an evolutionarily conserved component of the innate immune response found among all classes of life and represent the main form of invertebrate systemic immunity

Immunity may refer to:

Medicine

* Immunity (medical), resistance of an organism to infection or disease

* ''Immunity'' (journal), a scientific journal published by Cell Press

Biology

* Immune system

Engineering

* Radiofrequence immunity ...

. Several species of insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

produce antimicrobial peptides known as ''defensin

Defensins are small cysteine-rich cationic proteins across cellular life, including vertebrate and invertebrate animals, plants, and fungi. They are host defense peptides, with members displaying either direct Antimicrobial, antimicrobial activit ...

s'' and '' cecropins''.

Proteolytic cascades

In invertebrates, PRRs triggerproteolytic

Proteolysis is the breakdown of proteins into smaller polypeptides or amino acids. Protein degradation is a major regulatory mechanism of gene expression and contributes substantially to shaping mammalian proteomes. Uncatalysed, the hydrolysis o ...

cascades that degrade proteins and control many of the mechanisms of the innate immune system of invertebrates—including hemolymph

Hemolymph, or haemolymph, is a fluid, similar to the blood in invertebrates, that circulates in the inside of the arthropod's body, remaining in direct contact with the animal's tissues. It is composed of a fluid plasma in which hemolymph c ...

coagulation and melanization. Proteolytic cascades are important components of the invertebrate immune system because they are turned on more rapidly than other innate immune reactions because they do not rely on gene changes. Proteolytic cascades function in both vertebrate and invertebrates, even though different proteins are used throughout the cascades.

Clotting mechanisms

In the hemolymph, which makes up the fluid in the circulatory system ofarthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

s, a gel-like fluid surrounds pathogen invaders, similar to the way blood does in other animals. Various proteins and mechanisms are involved in invertebrate clotting. In crustaceans, transglutaminase from blood cells and mobile plasma proteins make up the clotting system, where the transglutaminase polymerizes 210 kDa subunits of a plasma-clotting protein. On the other hand, in the horseshoe crab

Horseshoe crabs are arthropods of the family Limulidae and the only surviving xiphosurans. Despite their name, they are not true crabs or even crustaceans; they are chelicerates, more closely related to arachnids like spiders, ticks, and scor ...

clotting system, components of proteolytic cascades are stored as inactive forms in granules of hemocytes, which are released when foreign molecules, like lipopolysaccharides enter.

Plants

Members of every class of pathogen that infect humans also infect plants. Although the exact pathogenic species vary with the infected species, bacteria, fungi, viruses, nematodes, and insects can all causeplant disease

Plant diseases are diseases in plants caused by pathogens (infectious organisms) and environmental conditions (physiological factors). Organisms that cause infectious disease include fungi, oomycetes, bacteria, viruses, viroids, virus-like or ...

. As with animals, plants attacked by insects or other pathogens use a set of complex metabolic

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the ...

responses that lead to the formation of defensive chemical compounds that fight infection or make the plant less attractive to insects and other herbivore

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically evolved to feed on plants, especially upon vascular tissues such as foliage, fruits or seeds, as the main component of its diet. These more broadly also encompass animals that eat ...

s. (see: plant defense against herbivory

Plant defense against herbivory or host-plant resistance is a range of adaptations Evolution, evolved by plants which improve their fitness (biology), survival and reproduction by reducing the impact of herbivores. Many plants produce secondary ...

).

Like invertebrates, plants neither generate antibody or T-cell responses nor possess mobile cells that detect and attack pathogens. In addition, in case of infection, parts of some plants are treated as disposable and replaceable, in ways that few animals can. Walling off or discarding a part of a plant helps stop infection spread.

Most plant immune responses involve systemic chemical signals sent throughout a plant. Plants use PRRs to recognize conserved microbial signatures. This recognition triggers an immune response. The first plant receptors of conserved microbial signatures were identified in rice ( XA21, 1995) and in ''Arabidopsis

''Arabidopsis'' (rockcress) is a genus in the family Brassicaceae. They are small flowering plants related to cabbage and mustard. This genus is of great interest since it contains thale cress (''Arabidopsis thaliana''), one of the model organ ...

'' (FLS2

''FLS'' genes have been discovered to be involved in flagellin reception of bacteria. FLS1 was the original gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence ...

, 2000). Plants also carry immune receptors that recognize variable pathogen effectors. These include the NBS-LRR class of proteins. When a part of a plant becomes infected with a microbial or viral pathogen, in case of an incompatible interaction triggered by specific elicitors, the plant produces a localized hypersensitive response (HR), in which cells at the site of infection undergo rapid apoptosis to prevent spread to other parts of the plant. HR has some similarities to animal pyroptosis, such as a requirement of caspase-1-like proteolytic activity of VPEγ, a cysteine protease

Cysteine proteases, also known as thiol proteases, are hydrolase enzymes that degrade proteins. These proteases share a common catalytic mechanism that involves a nucleophilic cysteine thiol in a catalytic triad or dyad.

Discovered by Gopal Chu ...

that regulates cell disassembly during cell death.

"Resistance" (R) proteins, encoded by R genes, are widely present in plants and detect pathogens. These proteins contain domains similar to the NOD Like Receptors and TLRs. Systemic acquired resistance (SAR) is a type of defensive response that renders the entire plant resistant to a broad spectrum of infectious agents. SAR involves the production of chemical messengers, such as salicylic acid

Salicylic acid is an organic compound with the formula HOC6H4COOH. A colorless (or white), bitter-tasting solid, it is a precursor to and a active metabolite, metabolite of acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin). It is a plant hormone, and has been lis ...

or jasmonic acid. Some of these travel through the plant and signal other cells to produce defensive compounds to protect uninfected parts, e.g., leaves. Salicylic acid itself, although indispensable for expression of SAR, is not the translocated signal responsible for the systemic response. Recent evidence indicates a role for jasmonates in transmission of the signal to distal portions of the plant. RNA silencing

RNA silencing or RNA interference refers to a family of gene silencing effects by which gene expression is negatively regulated by non-coding RNAs such as microRNAs. RNA silencing may also be defined as sequence-specific regulation of gene expressi ...

mechanisms are important in the plant systemic response, as they can block virus replication. The '' jasmonic acid response'' is stimulated in leaves damaged by insects, and involves the production of methyl jasmonate.

See also

*Antimicrobial peptides

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), also called host defence peptides (HDPs) are part of the innate immune response found among all classes of life. Fundamental differences exist between Prokaryote, prokaryotic and eukaryota, eukaryotic cells that may ...

* Apoptosis

Apoptosis (from ) is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms and in some eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms such as yeast. Biochemistry, Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (Morphology (biol ...

* Innate lymphoid cell

Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) are the most recently discovered family of Innate immune system, innate immune cells, derived from common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs). In response to pathogenic tissue damage, ILCs contribute to immunity via the secreti ...

* NOD-like receptor

The nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors, or NOD-like receptors (NLRs) (also known as nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat receptors), are intracellular sensors of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) that enter th ...

* Endothelial cell tropism

References

External links

* systemInnate Immune System Animation

XVIVO Scientific Animation {{Use dmy dates, date=August 2016 Immune system Insect immunity