Inelastic demand on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A good's price elasticity of demand (, PED) is a measure of how sensitive the quantity demanded is to its price. When the price rises, quantity demanded falls for almost any good (

Together with the concept of an economic "elasticity" coefficient,

Together with the concept of an economic "elasticity" coefficient,

A firm considering a price change must know what effect the change in price will have on total revenue. Revenue is simply the product of unit price times quantity:

:

Generally, any change in price will have two effects:

A firm considering a price change must know what effect the change in price will have on total revenue. Revenue is simply the product of unit price times quantity:

:

Generally, any change in price will have two effects:

short-run for Saudi Arabia in 2013} * Cinema visits (US) **−0.87 (general) * live performing arts (theater, etc.) ** −0.4 to −0.9 * Medicine (US) **−0.31 (medical insurance)Samuelson; Nordhaus (2001). **−0.03 to −0.06 (

A Lesson on Elasticity in Four Parts, Youtube, Jodi BeggsPrice Elasticity Models and OptimizationApprox. PED of Various Products (U.S.)Approx. PED of Various Home-Consumed Foods (U.K.)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Price Elasticity Of Demand Elasticity (economics) Demand Pricing

law of demand

In microeconomics, the law of demand is a fundamental principle which states that there is an inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded. In other words, "conditional on ceteris paribus, all else being equal, as the price of a Goods, ...

), but it falls more for some than for others. The price elasticity gives the percentage change in quantity demanded when there is a one percent increase in price, holding everything else constant. If the elasticity is −2, that means a one percent price rise leads to a two percent decline in quantity demanded. Other elasticities measure how the quantity demanded changes with other variables (e.g. the income elasticity of demand

In economics, the income elasticity of demand (YED) is the responsivenesses of the quantity demanded for a good to a change in consumer income. It is measured as the ratio of the percentage change in quantity demanded to the percentage change in ...

for consumer income changes).

Price elasticities are negative except in special cases. If a good is said to have an elasticity of 2, it almost always means that the good has an elasticity of −2 according to the formal definition. The phrase "more elastic" means that a good's elasticity has greater magnitude, ignoring the sign. Veblen and Giffen good

In microeconomics and consumer theory, a Giffen good is a product that people consume more of as the price rises and vice versa, violating the law of demand.

For ordinary goods, as the price of the good rises, the substitution effect makes ...

s are two classes of goods which have positive elasticity, rare exceptions to the law of demand

In microeconomics, the law of demand is a fundamental principle which states that there is an inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded. In other words, "conditional on ceteris paribus, all else being equal, as the price of a Goods, ...

. Demand for a good is said to be ''inelastic'' when the elasticity is less than one in absolute value: that is, changes in price have a relatively small effect on the quantity demanded. Demand for a good is said to be ''elastic'' when the elasticity is greater than one. A good with an elasticity of −2 has elastic demand because quantity demanded falls twice as much as the price increase; an elasticity of −0.5 has inelastic demand because the change in quantity demanded change is half of the price increase.

At an elasticity of 0 consumption would not change at all, in spite of any price increases.

Revenue is maximized when price is set so that the elasticity is exactly one. The good's elasticity can be used to predict the incidence (or "burden") of a tax on that good. Various research methods are used to determine price elasticity, including test market

A test market, in the field of business and marketing, is a geographic region or demographic group used to gauge the viability of a product or service in the mass market prior to a wide scale rollout. The criteria used to judge the acceptability ...

s, analysis of historical sales data and conjoint analysis

Conjoint analysis is a survey-based statistical technique used in market research that helps determine how people value different attributes (feature, function, benefits) that make up an individual product or service.

The objective of conjoint an ...

.

Definition

The variation in demand in response to a variation in price is called price elasticity of demand. It may also be defined as theratio

In mathematics, a ratio () shows how many times one number contains another. For example, if there are eight oranges and six lemons in a bowl of fruit, then the ratio of oranges to lemons is eight to six (that is, 8:6, which is equivalent to the ...

of the percentage change in quantity demanded to the percentage change in price of particular commodity.Png, Ivan (1989). p. 57. The formula for the coefficient of price elasticity of demand for a good is:Gillespie, Andrew (2007). p. 43.Gwartney, Yaw Bugyei-Kyei.James D.; Stroup, Richard L.; Sobel, Russell S. (2008). p. 425.

:

where is the initial price of the good demanded, is how much it changed, is the initial quantity of the good demanded, and is how much it changed. In other words, we can say that the price elasticity of demand is the percentage change in demand for a commodity due to a given percentage change in the price. If the quantity demanded falls 20 tons from an initial 200 tons after the price rises $5 from an initial price of $100, then the quantity demanded has fallen 10% and the price has risen 5%, so the elasticity is (−10%)/(+5%) = −2.

The price elasticity of demand is ordinarily negative because quantity demanded falls when price rises, as described by the "law of demand". Two rare classes of goods which have elasticity greater than 0 (consumers buy more if the price is ''higher'') are Veblen and Giffen goods.Gillespie, Andrew (2007). p. 57. Since the price elasticity of demand is negative for the vast majority of goods and services (unlike most other elasticities, which take both positive and negative values depending on the good), economists often leave off the word "negative" or the minus sign and refer to the price elasticity of demand as a positive value (i.e., in absolute value

In mathematics, the absolute value or modulus of a real number x, is the non-negative value without regard to its sign. Namely, , x, =x if x is a positive number, and , x, =-x if x is negative (in which case negating x makes -x positive), ...

terms). They will say "Yachts have an elasticity of two" meaning the elasticity is −2. This is a common source of confusion for students.

Depending on its elasticity, a good is said to have

elastic demand (> 1),

inelastic demand (< 1), or

unitary elastic demand (= 1). If demand is elastic, the quantity demanded is very sensitive to price, e.g. when a 1% rise in price generates a 10% decrease in quantity. If demand is inelastic, the good's demand is relatively insensitive to price, with quantity changing less than price. If demand is unitary elastic, the quantity falls by exactly the percentage that the price rises. Two important special cases are perfectly elastic demand (= ∞), where even a small rise in price reduces the quantity demanded to zero; and perfectly inelastic demand (= 0), where a rise in price leaves the quantity unchanged.

The above measure of elasticity is sometimes referred to as the ''own-price'' elasticity of demand for a good, i.e., the elasticity of demand with respect to the good's own price, in order to distinguish it from the elasticity of demand for that good with respect to the change in the price of some other good, i.e., an independent, complementary, or substitute good

In microeconomics, substitute goods are two goods that can be used for the same purpose by consumers. That is, a consumer perceives both goods as similar or comparable, so that having more of one good causes the consumer to desire less of the other ...

. That two-good type of elasticity is called a ''cross''-price elasticity of demand. If a 1% rise in the price of gasoline causes a 0.5% fall in the quantity of cars demanded, the cross-price elasticity is

As the size of the price change gets bigger, the elasticity definition becomes less reliable for a combination of two reasons. First, a good's elasticity is not necessarily constant; it varies at different points along the demand curve

A demand curve is a graph depicting the inverse demand function, a relationship between the price of a certain commodity (the ''y''-axis) and the quantity of that commodity that is demanded at that price (the ''x''-axis). Demand curves can be us ...

because a 1% change in price has a quantity effect that may depend on whether the initial price is high or low. Contrary to common misconception, the price elasticity is not constant even along a linear demand curve, but rather varies along the curve. A linear demand curve's slope is constant, to be sure, but the elasticity can change even if is constant.Parkin; Powell; Matthews (2002). p .75. There does exist a nonlinear shape of demand curve along which the elasticity is constant: , where is a shift constant and is the elasticity.

Second, percentage changes are not symmetric; instead, the percentage change

In any quantitative science, the terms relative change and relative difference are used to compare two quantities while taking into account the "sizes" of the things being compared, i.e. dividing by a ''standard'' or ''reference'' or ''starting' ...

between any two values depends on which one is chosen as the starting value and which as the ending value. For example, suppose that when the price rises from $10 to $16, the quantity falls from 100 units to 80. This is a price increase of 60% and a quantity decline of 20%, an elasticity of for that part of the demand curve. If the price falls from $16 to $10 and the quantity rises from 80 units to 100, however, the price decline is 37.5% and the quantity gain is 25%, an elasticity of for the same part of the curve. This is an example of the index number problem.Ruffin; Gregory (1988). pp. 518–519.Ferguson, C.E. (1972). pp. 100–101.

Two refinements of the definition of elasticity are used to deal with these shortcomings of the basic elasticity formula: ''arc elasticity'' and ''point elasticity''.

Arc elasticity

Arc elasticity was introduced very early on by Hugh Dalton. It is very similar to an ordinary elasticity problem, but it adds in the index number problem. A second solution to the asymmetry problem of having an elasticity dependent on which of the two given points on a demand curve is chosen as the "original" point and which as the "new" one is Arc Elasticity, which is to compute the percentage change in P and Q relative to the ''average'' of the two prices and the ''average'' of the two quantities, rather than just the change relative to one point or the other. Loosely speaking, this gives an "average" elasticity for the section of the actual demand curve—i.e., the ''arc'' of the curve—between the two points. As a result, this measure is known as the '' arc elasticity'', in this case with respect to the price of the good. The arc elasticity is defined mathematically as:Wall, Stuart; Griffiths, Alan (2008). pp. 53–54.McConnell;Brue (1990). pp. 434–435. : This method for computing the price elasticity is also known as the "midpoints formula", because the average price and average quantity are the coordinates of the midpoint of the straight line between the two given points. This formula is an application of the midpoint method. However, because this formula implicitly assumes the section of the demand curve between those points is linear, the greater the curvature of the actual demand curve is over that range, the worse this approximation of its elasticity will be.Point elasticity

In order to avoid the accuracy problem described above, the difference between the starting and ending prices and quantities should be minimised. This is the approach taken in the definition of ''point'' elasticity, which usesdifferential calculus

In mathematics, differential calculus is a subfield of calculus that studies the rates at which quantities change. It is one of the two traditional divisions of calculus, the other being integral calculus—the study of the area beneath a curve. ...

to calculate the elasticity for an infinitesimal change in price and quantity at any given point on the demand curve:Sloman, John (2006). p. 55.

:

In other words, it is equal to the absolute value of the first derivative of quantity with respect to price multiplied by the point's price (''P'') divided by its quantity (''Q''d).Wessels, Walter J. (2000). p. 296. However, the point elasticity can be computed only if the formula for the demand function

In economics, an inverse demand function is the mathematical relationship that expresses price as a function of quantity demanded (it is therefore also known as a price function).

Historically, the economists first expressed the price of a good a ...

, , is known so its derivative with respect to price, , can be determined.

In terms of partial-differential calculus, point elasticity of demand can be defined as follows: let be the demand of goods as a function of parameters price and wealth, and let be the demand for good . The elasticity of demand for good with respect to price is

:

History

Together with the concept of an economic "elasticity" coefficient,

Together with the concept of an economic "elasticity" coefficient, Alfred Marshall

Alfred Marshall (26 July 1842 – 13 July 1924) was an English economist and one of the most influential economists of his time. His book ''Principles of Economics (Marshall), Principles of Economics'' (1890) was the dominant economic textboo ...

is credited with defining "elasticity of demand" in '' Principles of Economics'', published in 1890. Alfred Marshall invented price elasticity of demand only four years after he had invented the concept of elasticity. He used Cournot's basic creating of the demand curve to get the equation for price elasticity of demand. He described price elasticity of demand as thus: "And we may say generally:— the elasticity (or responsiveness) of demand in a market is great or small according as the amount demanded increases much or little for a given fall in price, and diminishes much or little for a given rise in price". He reasons this since "the only universal law as to a person's desire for a commodity is that it diminishes ... but this diminution may be slow or rapid. If it is slow... a small fall in price will cause a comparatively large increase in his purchases. But if it is rapid, a small fall in price will cause only a very small increase in his purchases. In the former case... the elasticity of his wants, we may say, is great. In the latter case... the elasticity of his demand is small." Mathematically, the Marshallian PED was based on a point-price definition, using differential calculus to calculate elasticities.

Determinants

The overriding factor in determining the elasticity is the willingness and ability of consumers after a price change to postpone immediate consumption decisions concerning the good and to search for substitutes ("wait and look").Negbennebor (2001). A number of factors can thus affect the elasticity of demand for a good:Parkin; Powell; Matthews (2002). pp. 77–9. * Availability of substitute goods: The more and closer the substitutes available, the higher the elasticity is likely to be, as people can easily switch from one good to another if an even minor price change is made;Goodwin, Nelson, Ackerman, & Weisskopf (2009). There is a strong substitution effect.Frank (2008) 118. If no close substitutes are available, the substitution effect will be small and the demand inelastic. ** Breadth of definition: The broader the definition of a good (or service), the lower the elasticity, because it is no longer possible to . For example, McDonalds hamburgers will probably have a relatively high elasticity of demand (as customers can switch to other fast-food options), whereas food in general will have an extremely low elasticity of demand, because no substitutes exist.Gillespie, Andrew (2007). p. 48. Specific foodstuffs (ice cream, meat, spinach) or families of them (dairy, meat, sea products) may be more elastic. * Necessity: The more necessary a good is, the lower the elasticity, as people will attempt to buy it no matter the price, such as the case ofinsulin

Insulin (, from Latin ''insula'', 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the insulin (''INS)'' gene. It is the main Anabolism, anabolic hormone of the body. It regulates the metabol ...

for those who need it.

* Timespan: For most goods, the longer a price change holds, the higher the elasticity is likely to be, as more and more consumers find they have the time and inclination to search for substitutes. When fuel prices increase suddenly, for instance, consumers may still fill up their empty tanks in the short run, but when prices remain high over several years, more consumers will reduce their demand for fuel by switching to carpool

Carpooling is the sharing of Automobile, car journeys so that more than one person travels in a car, and prevents the need for others to have to drive to a location themselves. Carpooling is considered a Demand-Responsive Transport (DRT) serv ...

ing or public transportation, investing in vehicles with greater fuel economy or taking other measures. This does not hold for consumer durables such as the cars themselves, however; eventually, it may become necessary for consumers to replace their present cars, so one would expect demand to be less elastic.

* Brand loyalty: An attachment to a certain brand can override sensitivity to price changes, resulting in more inelastic demand.Png, Ivan (1999). pp. 62–3.

* Who pays: Where the purchaser does not directly pay for the good they consume, such as with corporate expense accounts, demand is likely to be more inelastic.

When measuring Marshallian demand—the demand curve holding nominal, rather than real, income constant—the percentage of income a customer spends on a certain good also affects the elasticity. In introductory microeconomics

Microeconomics is a branch of economics that studies the behavior of individuals and Theory of the firm, firms in making decisions regarding the allocation of scarcity, scarce resources and the interactions among these individuals and firms. M ...

, the distinction between Marshallian and Hicksian (real-value) demand is often ignored, assuming that any particular good will be a small part of the customer's budget, but for large or frequent purchases (e.g. food or transportation) the income effect

The theory of consumer choice is the branch of microeconomics that relates preferences to consumption expenditures and to consumer demand curves. It analyzes how consumers maximize the desirability of their consumption (as measured by their pr ...

can become substantial or even dominate the price effect (as for Giffen goods).Frank (2008) 119. When the goods represent only a negligible portion of the budget, the income effect is insignificant and does not contribute substantially to elasticity.

Relation to marginal revenue

The following equation holds: : where : ''R''′ is themarginal revenue

Marginal revenue (or marginal benefit) is a central concept in microeconomics that describes the additional total revenue generated by increasing product sales by 1 unit.Bradley R. chiller, "Essentials of Economics", New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., ...

: ''P'' is the price

Proof:

: Define Total Revenue as ''R''

:

:

:

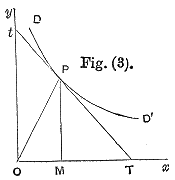

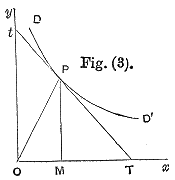

On a graph with both a demand curve and a marginal revenue curve, demand will be elastic at all quantities where marginal revenue is positive. Demand is unit elastic at the quantity where marginal revenue is zero. Demand is inelastic at every quantity where marginal revenue is negative.

Effect on entire revenue

The price effect

For inelastic goods, an increase in unit price will tend to increase revenue, while a decrease in price will tend to decrease revenue. (The effect is reversed for elastic goods.)The quantity effect

An increase in unit price will tend to lead to fewer units sold, while a decrease in unit price will tend to lead to more units sold. For inelastic goods, because of the inverse nature of the relationship between price and quantity demanded (i.e., the law of demand), the two effects affect total revenue in opposite directions. But in determining whether to increase or decrease prices, a firm needs to know what the net effect will be. Elasticity provides the answer: The percentage change in total revenue is approximately equal to the percentage change in quantity demanded plus the percentage change in price. (One change will be positive, the other negative.) The percentage change in quantity is related to the percentage change in price by elasticity: hence the percentage change in revenue can be calculated by knowing the elasticity and the percentage change in price alone. As a result, the relationship between elasticity and revenue can be described for any good:Arnold, Roger (2008). p. 385. * When the price elasticity of demand for agood

In most contexts, the concept of good denotes the conduct that should be preferred when posed with a choice between possible actions. Good is generally considered to be the opposite of evil. The specific meaning and etymology of the term and its ...

is ''perfectly inelastic'' (''E''''d'' = 0), changes in the price do not affect the quantity demanded for the good; raising prices will always cause total revenue to increase. Goods necessary to survival can be classified here; a rational person will be willing to pay anything for a good if the alternative is death. For example, a person in the desert weak and dying of thirst would easily give all the money in his wallet, no matter how much, for a bottle of water if he would otherwise die. His demand is not contingent on the price.

* When the price elasticity of demand is ''relatively inelastic'' (−1 < ''E''''d'' < 0), the percentage change in quantity demanded is smaller than that in price. Hence, when the price is raised, the total revenue increases, and vice versa.

* When the price elasticity of demand is ''unit (or unitary) elastic'' (''E''''d'' = −1), the percentage change in quantity demanded is equal to that in price, so a change in price will not affect total revenue.

* When the price elasticity of demand is ''relatively elastic'' (−∞ < ''E''''d'' < −1), the percentage change in quantity demanded is greater than that in price. Hence, when the price is raised, the total revenue falls, and vice versa.

* When the price elasticity of demand is ''perfectly elastic'' (''E''''d'' is − ∞

The infinity symbol () is a List of mathematical symbols, mathematical symbol representing the concept of infinity. This symbol is also called a ''lemniscate'', after the lemniscate curves of a similar shape studied in algebraic geometry, or " ...

), any increase in the price, no matter how small, will cause the quantity demanded for the good to drop to zero. Hence, when the price is raised, the total revenue falls to zero. This situation is typical for goods that have their value defined by law (such as fiat currency

Fiat money is a type of government-issued currency that is not backed by a precious metal, such as gold or silver, nor by any other tangible asset or commodity. Fiat currency is typically designated by the issuing government to be legal tender, ...

); if a five-dollar bill were sold for anything more than five dollars, nobody would buy it nless there is demand for economical jokes so demand is zero (assuming that the bill does not have a misprint or something else which would cause it to have its own inherent value).

Hence, as the accompanying diagram shows, total revenue is maximized at the combination of price and quantity demanded where the elasticity of demand is unitary.

Price-elasticity of demand is ''not'' necessarily constant over all price ranges. The linear demand curve in the accompanying diagram illustrates that changes in price also change the elasticity: the price elasticity is different at every point on the curve.

Effect on tax incidence

Demand elasticity, in combination with the price elasticity of supply can be used to assess where the incidence (or "burden") of a per-unit tax is falling or to predict where it will fall if the tax is imposed. For example, when demand is ''perfectly inelastic'', by definition consumers have no alternative to purchasing the good or service if the price increases, so the quantity demanded would remain constant. Hence, suppliers can increase the price by the full amount of the tax, and the consumer would end up paying the entirety. In the opposite case, when demand is ''perfectly elastic'', by definition consumers have an infinite ability to switch to alternatives if the price increases, so they would stop buying the good or service in question completely—quantity demanded would fall to zero. As a result, firms cannot pass on any part of the tax by raising prices, so they would be forced to pay all of it themselves.Wall, Stuart; Griffiths, Alan (2008). pp. 57–58. In practice, demand is likely to be only ''relatively'' elastic or relatively inelastic, that is, somewhere between the extreme cases of perfect elasticity or inelasticity. More generally, then, the ''higher'' the elasticity of demand compared to PES, the heavier the burden on producers; conversely, the more ''inelastic'' the demand compared to supply, the heavier the burden on consumers. The general principle is that the party (i.e., consumers or producers) that has ''fewer'' opportunities to avoid the tax by switching to alternatives will bear the ''greater'' proportion of the tax burden. PED and PES can also have an effect on the deadweight loss associated with a tax regime. When PED, PES or both are inelastic, the deadweight loss is lower than a comparable scenario with higher elasticity.Optimal pricing

Among the most common applications of price elasticity is to determine prices that maximize revenue or profit.Constant elasticity and optimal pricing

If one point elasticity is used to model demand changes over a finite range of prices, elasticity is implicitly assumed constant with respect to price over the finite price range. The equation defining price elasticity for one product can be rewritten (omitting secondary variables) as a linear equation. : where : is the elasticity, and is a constant. Similarly, the equations for cross elasticity for products can be written as a set of simultaneous linear equations. : where : and , and are constants; and appearance of a letter index as both an upper index and a lower index in the same term implies summation over that index. This form of the equations shows that point elasticities assumed constant over a price range cannot determine what prices generate maximum values of ; similarly they cannot predict prices that generate maximum or maximum revenue. Constant elasticities can predict optimal pricing only by computing point elasticities at several points, to determine the price at which point elasticity equals −1 (or, for multiple products, the set of prices at which the point elasticity matrix is the negative identity matrix).Non-constant elasticity and optimal pricing

If the definition of price elasticity is extended to yield a quadratic relationship between demand units () and price, then it is possible to compute prices that maximize , , and revenue. The fundamental equation for one product becomes : and the corresponding equation for several products becomes : Excel models are available that compute constant elasticity, and use non-constant elasticity to estimate prices that optimize revenue or profit for one product or several products.Limitations of revenue-maximizing strategies

In most situations, such as those with nonzero variable costs, revenue-maximizing prices are not profit-maximizing prices. For these situations, using a technique forProfit maximization

In economics, profit maximization is the short run or long run process by which a firm may determine the price, input and output levels that will lead to the highest possible total profit (or just profit in short). In neoclassical economics, ...

is more appropriate.

Selected price elasticities

Various research methods are used to calculate the price elasticities in real life, including analysis of historic sales data, both public and private, and use of present-day surveys of customers' preferences to build up test markets capable of modelling such changes. Alternatively,conjoint analysis

Conjoint analysis is a survey-based statistical technique used in market research that helps determine how people value different attributes (feature, function, benefits) that make up an individual product or service.

The objective of conjoint an ...

(a ranking of users' preferences which can then be statistically analysed) may be used. Approximate estimates of price elasticity can be calculated from the income elasticity of demand

In economics, the income elasticity of demand (YED) is the responsivenesses of the quantity demanded for a good to a change in consumer income. It is measured as the ratio of the percentage change in quantity demanded to the percentage change in ...

, under conditions of preference independence. This approach has been empirically validated using bundles of goods (e.g. food, healthcare, education, recreation, etc.).

Though elasticities for most demand schedules vary depending on price, they can be modeled assuming constant elasticity. Using this method, the elasticities for various goods—intended to act as examples of the theory described above—are as follows. For suggestions on why these goods and services may have the elasticity shown, see the above section on determinants of price elasticity.

* Cigarettes (US)Perloff, J. (2008). p. 97.

** −0.3 to −0.6 (general)

** −0.6 to −0.7 (youth)

* Alcoholic beverages

Drinks containing alcohol are typically divided into three classes—beers, wines, and spirits—with alcohol content typically between 3% and 50%. Drinks with less than 0.5% are sometimes considered non-alcoholic.

Many societies have a di ...

(US)

**−0.3 or −0.7 to −0.9 as of 1972 (beer)

**−1.0 (wine)

**−1.5 (spirits)

* Airline travel (US)Pindyck; Rubinfeld (2001). p. 381.; Steven Morrison in Duetsch (1993), p. 231.

**−0.3 (first class)

**−0.9 (discount)

**−1.5 (for pleasure travelers)

* Livestock

** −0.5 to −0.6 (broiler chicken

Breed broiler is any chicken (''Gallus gallus domesticus'') that is bred and raised specifically for meat production. Most commercial broilers reach slaughter weight between four and six weeks of age, although slower growing breeds reach slau ...

s)

* Oil (World)

**−0.4

* Car fuel

**−0.09 (short run)

**−0.31 (long run)

**−0.085 to −0.13 (non-linear with price change in the short-run for Saudi Arabia in 2013} * Cinema visits (US) **−0.87 (general) * live performing arts (theater, etc.) ** −0.4 to −0.9 * Medicine (US) **−0.31 (medical insurance)Samuelson; Nordhaus (2001). **−0.03 to −0.06 (

pediatric

Pediatrics (American English) also spelled paediatrics (British English), is the branch of medicine that involves the medical care of infants, children, adolescents, and young adults. In the United Kingdom, pediatrics covers many of their youth ...

visits)

* Patents

**−0.45

* RicePerloff, J. (2008).

**−0.47 (Austria)

**−0.8 (Bangladesh)

**−0.8 (China)

**−0.25 (Japan)

**−0.55 (US)

* Trademarks

**−0.25 to −0.40 (international market)

* Transport

** −0.20 (bus travel US)

** −2.8 (Ford compact automobile)

** −0.52 (commuter parking)

*Cannabis (US)

**−0.655

* Soft drinks

**−0.8 to −1.0 (general)

**−3.8 (Coca-Cola

Coca-Cola, or Coke, is a cola soft drink manufactured by the Coca-Cola Company. In 2013, Coke products were sold in over 200 countries and territories worldwide, with consumers drinking more than 1.8 billion company beverage servings ...

)Ayers; Collinge (2003). p. 120.

**−4.4 (Mountain Dew

Mountain Dew, stylized as Mtn Dew in some countries and colloquially known as Dew in some areas, is a soft drink brand owned by PepsiCo. The original formula was invented in 1940 by Tennessee beverage Bottler (company), bottlers Barney and A ...

)

* Steel

**−0.2 to −0.3Barnett and Crandall in Duetsch (1993), p. 147

* Telecommunications

**−0.405 (mobile)

**−0.434 (broadband)

*Eggs

**−0.1 (US: household only)

**−0.35 (Canada)

**−0.55 (South Africa)

*Golf

**−0.3 to −0.7

*University education

** near 0

See also

* Arc elasticity *Cross elasticity of demand

In economics, the cross (or cross-price) elasticity of demand (XED) measures the effect of changes in the price of one good on the quantity demanded of another good. This reflects the fact that the quantity demanded of good is dependent on not on ...

*Income elasticity of demand

In economics, the income elasticity of demand (YED) is the responsivenesses of the quantity demanded for a good to a change in consumer income. It is measured as the ratio of the percentage change in quantity demanded to the percentage change in ...

* Price elasticity of supply

*Supply and demand

In microeconomics, supply and demand is an economic model of price determination in a Market (economics), market. It postulates that, Ceteris_paribus#Applications, holding all else equal, the unit price for a particular Good (economics), good ...

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

A Lesson on Elasticity in Four Parts, Youtube, Jodi Beggs

{{DEFAULTSORT:Price Elasticity Of Demand Elasticity (economics) Demand Pricing