Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of

power

Power may refer to:

Common meanings

* Power (physics), meaning "rate of doing work"

** Engine power, the power put out by an engine

** Electric power, a type of energy

* Power (social and political), the ability to influence people or events

Math ...

over foreign nations, particularly through

expansionism

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military Imperialism, empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established p ...

, employing both

hard power

In politics, hard power is the use of military and economics, economic means to social influence, influence the behavior or interests of other political bodies. This form of political power is often aggressive (coercion), and is most immediately ...

(military and economic power) and

soft power

In politics (and particularly in international politics), soft power is the ability to co-option, co-opt rather than coerce (in contrast with hard power). It involves shaping the preferences of others through appeal and attraction. Soft power is ...

(

diplomatic power and

cultural imperialism

Cultural imperialism (also cultural colonialism) comprises the culture, cultural dimensions of imperialism. The word "imperialism" describes practices in which a country engages culture (language, tradition, ritual, politics, economics) to creat ...

). Imperialism focuses on establishing or maintaining

hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one State (polity), state over other states, either regional or global.

In Ancient Greece (ca. 8th BC – AD 6th c.), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of ...

and a more formal

empire

An empire is a political unit made up of several territories, military outpost (military), outposts, and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a hegemony, dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the ...

.

While related to the concept of

colonialism

Colonialism is the control of another territory, natural resources and people by a foreign group. Colonizers control the political and tribal power of the colonised territory. While frequently an Imperialism, imperialist project, colonialism c ...

, imperialism is a distinct concept that can apply to other forms of expansion and many forms of government.

Etymology and usage

The word ''imperialism'' was derived from the Latin word , which means 'to command', 'to be

sovereign

''Sovereign'' is a title that can be applied to the highest leader in various categories. The word is borrowed from Old French , which is ultimately derived from the Latin">-4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to ...

', or simply 'to rule'. It was coined in the 19th century to decry

Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

's despotic militarism and his attempts at obtaining political support through foreign military interventions.

The term became common in the current sense in Great Britain during the 1870s; by the 1880s it was used with a positive connotation. By the end of the 19th century, the term was used to describe the behavior of empires at all times and places.

Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt (born Johanna Arendt; 14 October 1906 – 4 December 1975) was a German and American historian and philosopher. She was one of the most influential political theory, political theorists of the twentieth century.

Her work ...

and

Joseph Schumpeter

Joseph Alois Schumpeter (; February 8, 1883 – January 8, 1950) was an Austrian political economist. He served briefly as Finance Minister of Austria in 1919. In 1932, he emigrated to the United States to become a professor at Harvard Unive ...

defined imperialism as expansion for the sake of expansion.

"Imperialism" was and is mainly used to refer to Western and Japanese political and economic dominance, especially in Asia and Africa,

in the 19th and 20th centuries. Its precise meaning continues to be debated by scholars. Some writers, such as

Edward Said

Edward Wadie Said (1 November 1935 – 24 September 2003) was a Palestinian-American academic, literary critic, and political activist. As a professor of literature at Columbia University, he was among the founders of Postcolonialism, post-co ...

, use the term more broadly to describe any system of domination and subordination organized around an imperial

core

Core or cores may refer to:

Science and technology

* Core (anatomy), everything except the appendages

* Core (laboratory), a highly specialized shared research resource

* Core (manufacturing), used in casting and molding

* Core (optical fiber ...

and a

periphery

Periphery or peripheral may refer to:

Music

*Periphery (band), American progressive metal band

* ''Periphery'' (album), released in 2010 by Periphery

*"Periphery", a song from Fiona Apple's album '' The Idler Wheel...''

Gaming and entertainme ...

.

[Edward W. Said. Culture and Imperialism. Vintage Publishers, 1994. p. 9.] This definition encompasses both nominal empires and

neocolonialism

Neocolonialism is the control by a state (usually, a former colonial power) over another nominally independent state (usually, a former colony) through indirect means. The term ''neocolonialism'' was first used after World War II to refer to ...

.

Versus colonialism

The term "imperialism" is often conflated with "

colonialism

Colonialism is the control of another territory, natural resources and people by a foreign group. Colonizers control the political and tribal power of the colonised territory. While frequently an Imperialism, imperialist project, colonialism c ...

"; however, many scholars have argued that each has its own distinct definition. Imperialism and colonialism have been used in order to describe one's influence upon a person or group of people.

Robert Young writes that imperialism operates from the centre as a state policy and is developed for ideological as well as financial reasons, while colonialism is simply the development for settlement or commercial intentions; however, colonialism still includes invasion. Colonialism in modern usage also tends to imply a degree of geographic separation between the colony and the imperial power. Particularly, Edward Said distinguishes between imperialism and colonialism by stating: "imperialism involved 'the practice, the theory and the attitudes of a dominating metropolitan center ruling a distant territory', while colonialism refers to the 'implanting of settlements on a distant territory.'

[ Contiguous land empires such as the Russian, Chinese or Ottoman have traditionally been excluded from discussions of colonialism, though this is beginning to change, since it is accepted that they also sent populations into the territories they ruled.]Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

suggested that "imperialism was the highest form of capitalism", claiming that "imperialism developed after colonialism, and was distinguished from colonialism by monopoly capitalism".[

]

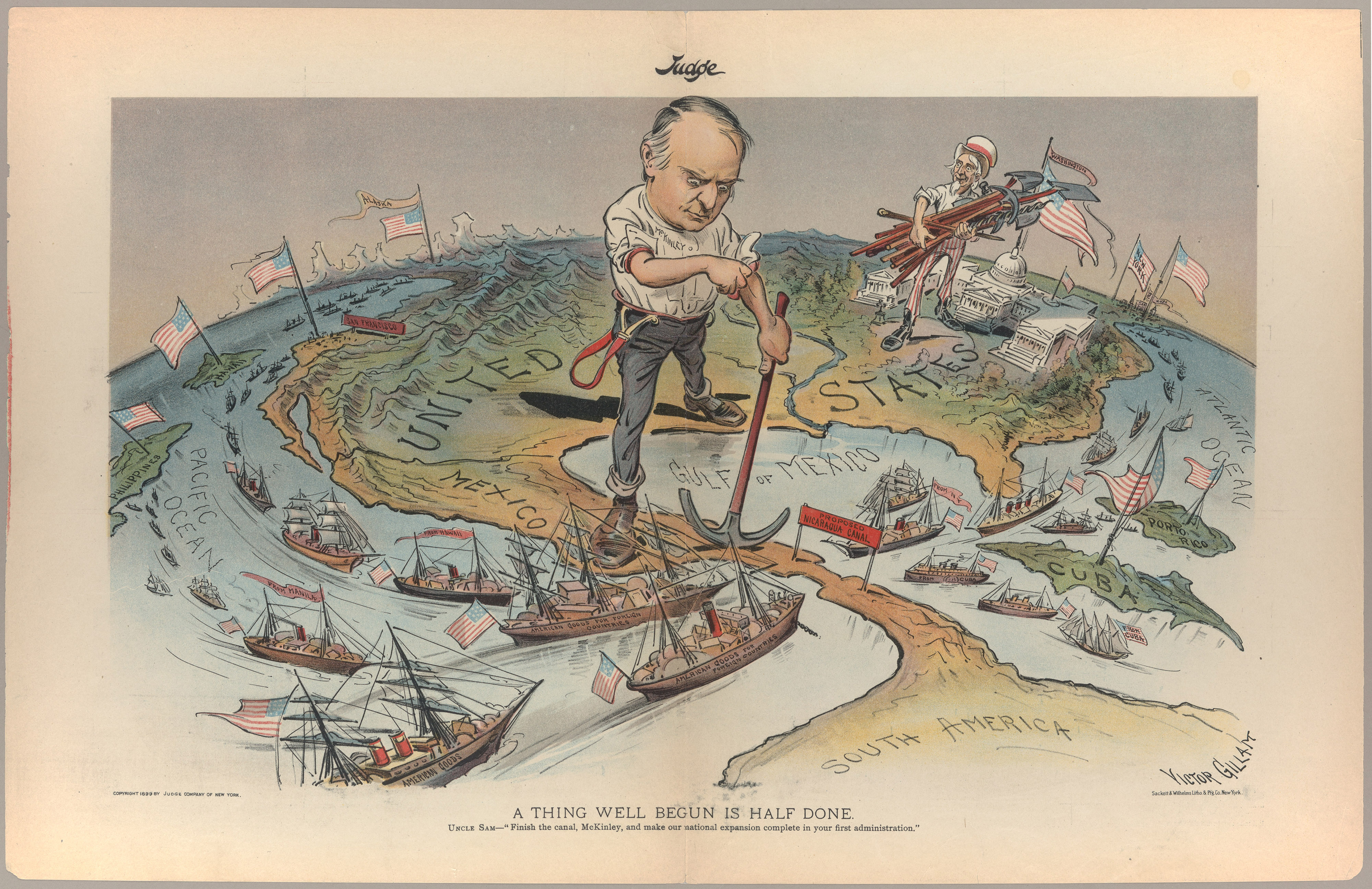

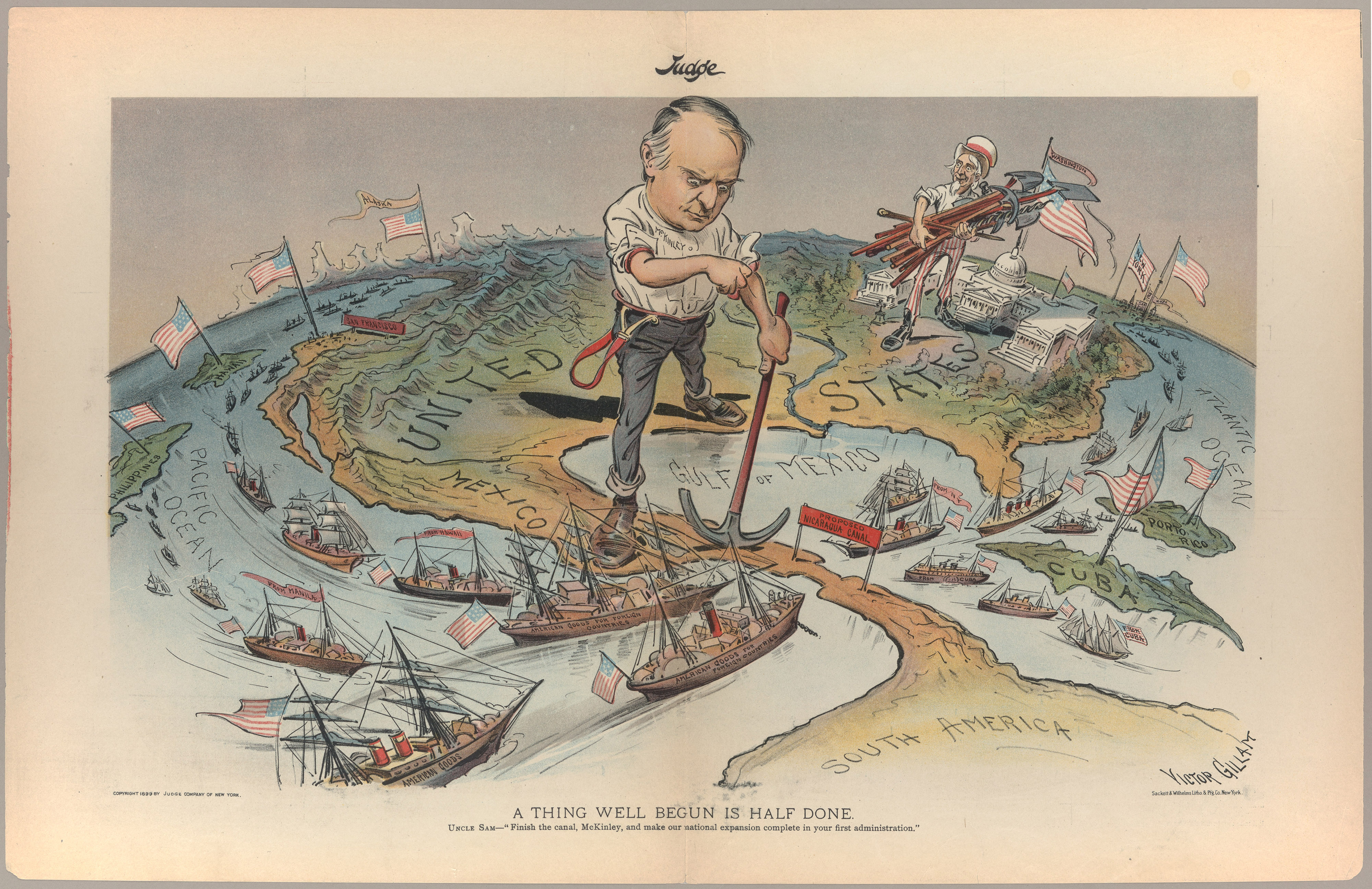

Age of Imperialism

Imperialism has been present and prominent since the beginning of history,[ Lieven, Dominic (2012). "Empire, history and the contemporary global order," ''Proceedings of the British Academy'', vol 131: p 132, https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/documents/2012/pba131p127.pdf][Waltz, Kenneth (1979). '']Theory of International Politics

''Theory of International Politics'' is a 1979 book on international relations theory by Kenneth Waltz that creates a structural realist theory, neorealism (international relations), neorealism, to explain international relations. Taking into ac ...

''. (Boston: McGraw-Hill), p 25, https://archive.org/details/theoryofinternat00walt/page/24/mode/2up?view=theater and its most intensive phase occurred in the Axial Age

''Axial Age'' (also ''Axis Age'', from the German ) is a term coined by the German philosopher Karl Jaspers. It refers to broad changes in religious and philosophical thought that occurred in a variety of locations from about the 8th to the 3rd ...

. But the concept ''Age of Imperialism'' refers to the period pre-dating World War I. While the end of the period is commonly fixed in 1914, the date of the beginning varies between 1760 and 1870. The latter date makes the Age of Imperialism identitcal with the New Imperialism

In History, historical contexts, New Imperialism characterizes a period of Colonialism, colonial expansion by European powers, the American imperialism, United States, and Empire of Japan, Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. ...

. The Age saw European nations, helped by industrialization, intensifying the process of colonizing, influencing, and annexing other parts of the world. In the late 19th century, they were joined by the United States and Japan. Other 19th century episodes included the Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa was the invasion, conquest, and colonialism, colonisation of most of Africa by seven Western European powers driven by the Second Industrial Revolution during the late 19th century and early 20th century in the era of ...

and Great Game

The Great Game was a rivalry between the 19th-century British Empire, British and Russian Empire, Russian empires over influence in Central Asia, primarily in Emirate of Afghanistan, Afghanistan, Qajar Iran, Persia, and Tibet. The two colonia ...

.

In the 1970s British historians John Gallagher (1919–1980) and

In the 1970s British historians John Gallagher (1919–1980) and Ronald Robinson

Ronald "Robbie" Edward Robinson, CBE, DFC, FBA (3 September 1920 – 19 June 1999) was a distinguished historian of the British Empire who between 1971 and 1987 held the Beit Professorship of Commonwealth History at the University of Oxford.

...

(1920–1999) argued that European leaders rejected the notion that "imperialism" required formal, legal control by one government over a colonial region. Much more important was informal control of independent areas. According to Wm. Roger Louis, "In their view, historians have been mesmerized by formal empire and maps of the world with regions colored red. The bulk of British emigration, trade, and capital went to areas outside the formal British Empire. Key to their thinking is the idea of empire 'informally if possible and formally if necessary.'" Oron Hale says that Gallagher and Robinson looked at the British involvement in Africa where they "found few capitalists, less capital, and not much pressure from the alleged traditional promoters of colonial expansion. Cabinet decisions to annex or not to annex were made, usually on the basis of political or geopolitical considerations."Mughal Bengal

The Bengal Subah ( Bengali: সুবাহ বাংলা, ), also referred to as Mughal Bengal and Bengal State (after 1717), was one of the puppet states and the largest subdivision of The Mughal Empire encompassing much of the Bengal ...

, but not from most of the rest of its empire. According to Indian Economist Utsa Patnaik

Utsa Patnaik is an Indian Marxian economist. She taught at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning in the School of Social Sciences at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in New Delhi, from 1973 until her retirement in 2010. Her husband i ...

, the scale of the wealth transfer out of India, between 1765 and 1938, was an estimated $45 Trillion. The Netherlands did very well in the East Indies. Germany and Italy got very little trade or raw materials from their empires. France did slightly better. The Belgian Congo was notoriously profitable when it was a capitalistic rubber plantation owned and operated by King Leopold II as a private enterprise. However, scandal after scandal regarding atrocities in the Congo Free State

From 1885 to 1908, many atrocities were committed in the Congo Free State (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo) under the absolute rule of King Leopold II of Belgium. These atrocities were particularly associated with the labour polici ...

led the international community to force the government of Belgium to take it over in 1908, and it became much less profitable. The Philippines cost the United States much more than expected because of military action against rebels.Mughal

Mughal or Moghul may refer to:

Related to the Mughal Empire

* Mughal Empire of South Asia between the 16th and 19th centuries

* Mughal dynasty

* Mughal emperors

* Mughal people, a social group of Central and South Asia

* Mughal architecture

* Mug ...

state, and, while military activity was important at various times, the economic and administrative incorporation of local elites was also of crucial significance" for the establishment of control over the subcontinent's resources, markets, and manpower. Although a substantial number of colonies had been designed to provide economic profit and to ship resources to home ports in the 17th and 18th centuries, D. K. Fieldhouse suggests that in the 19th and 20th centuries in places such as Africa and Asia, this idea is not necessarily valid:

During this time, European merchants had the ability to "roam the high seas and appropriate surpluses from around the world (sometimes peaceably, sometimes violently) and to concentrate them in Europe".

European expansion greatly accelerated in the 19th century. To obtain raw materials, Europe expanded imports from other countries and from the colonies. European industrialists sought raw materials such as dyes, cotton, vegetable oils, and metal ores from overseas. Concurrently, industrialization was quickly making Europe the centre of manufacturing and economic growth, driving resource needs.Anglo-Zulu War

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in present-day South Africa from January to early July 1879 between forces of the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom. Two famous battles of the war were the Zulu victory at Battle of Isandlwana, Isandlwana and th ...

of 1879).Battle of Adwa

The Battle of Adwa (; ; , also spelled ''Adowa'') was the climactic battle of the First Italo-Ethiopian War. The Ethiopian army defeated an invading Italian and Eritrean force led by Oreste Baratieri on March 1, 1896, near the town of Adwa. ...

, and the Japanese Imperial Army of Japan

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA; , ''Dai-Nippon Teikoku Rikugun'', "Army of the Greater Japanese Empire") was the principal ground force of the Empire of Japan from 1871 to 1945. It played a central role in Japan’s rapid modernization during th ...

, but these still relied heavily on weapons imported from Europe and often on European military advisors.

Theories of imperialism

Anglophone academic studies often base their theories regarding imperialism on the British experience of Empire. The term ''imperialism'' was originally introduced into English in its present sense in the late 1870s by opponents of the allegedly aggressive and ostentatious imperial policies of British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a ...

. Supporters of "imperialism" such as Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal Party (UK), Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually was a leading New Imperialism, imperial ...

quickly appropriated the concept. For some, imperialism designated a policy of idealism and philanthropy; others alleged that it was characterized by political self-interest, and a growing number associated it with capitalist greed.

Historians and political theorists have long debated the correlation between capitalism, class, and imperialism. Much of the debate was pioneered by such theorists as John A. Hobson (1858–1940), Joseph Schumpeter

Joseph Alois Schumpeter (; February 8, 1883 – January 8, 1950) was an Austrian political economist. He served briefly as Finance Minister of Austria in 1919. In 1932, he emigrated to the United States to become a professor at Harvard Unive ...

(1883–1950), Thorstein Veblen

Thorstein Bunde Veblen (; July 30, 1857 – August 3, 1929) was an American Economics, economist and Sociology, sociologist who, during his lifetime, emerged as a well-known Criticism of capitalism, critic of capitalism.

In his best-known book ...

(1857–1929), and Norman Angell

Sir Ralph Norman Angell (26 December 1872 – 7 October 1967) was an English Nobel Peace Prize winner. He was a lecturer, journalist, author and Member of Parliament for the Labour Party.

Angell was one of the principal founders of the Union ...

(1872–1967). While these non-Marxist writers were at their most prolific before World War I, they remained active in the interwar years

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

. Their combined work informed the study of imperialism and its impact on Europe, as well as contributing to reflections on the rise of the military-political complex in the United States from the 1950s.

In '' Imperialism: A Study'' (1902), Hobson developed a highly influential interpretation of imperialism that expanded on his belief that free-enterprise capitalism had a harmful effect on the majority of the population. In ''Imperialism'' he argued that the financing of overseas empires drained money that was needed at home. It was invested abroad because lower wages paid to workers overseas made for higher profits and higher rates of return, compared to domestic wages. So, although domestic wages remained higher, they did not grow nearly as fast as they might otherwise have. Exporting capital, he concluded, put a lid on the growth of domestic wages and the domestic standard of living. Hobson theorized that domestic social reforms could cure the international disease of imperialism by removing its economic foundation, while state intervention through taxation could boost broader consumption, create wealth, and encourage a peaceful, tolerant, multipolar world order.

By the 1970s, historians such as David K. FieldhouseDavid Landes

David Saul Landes (April 29, 1924 – August 17, 2013) was a professor of economics and of history at Harvard University. He is the author of ''Bankers and Pashas'', '' Revolution in Time'', '' The Unbound Prometheus'', '' The Wealth and Poverty ...

claims that businessmen were less enthusiastic about colonialism than statesmen and adventurers.

However, European Marxists picked up Hobson's ideas wholeheartedly and made it into their own theory of imperialism, most notably in Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

's ''Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism

''Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism'', originally published as ''Imperialism, the Newest Stage of Capitalism'', is a book written by Vladimir Lenin in 1916 and published in 1917. It describes the formation of oligopoly, by the interlac ...

'' (1916). Lenin portrayed imperialism as the closure of the world market and the end of capitalist free-competition that arose from the need for capitalist economies to constantly expand investment, material resources and manpower in such a way that necessitated colonial expansion. Later Marxist theoreticians echo this conception of imperialism as a structural feature of capitalism, which explained the World War as the battle between imperialists for control of external markets. Lenin's treatise became a standard textbook that flourished until the collapse of communism in 1989–91.

Some theoreticians on the non-Communist left have emphasized the structural or systemic character of "imperialism". Such writers have expanded the period associated with the term so that it now designates neither a policy, nor a short space of decades in the late 19th century, but a world system extending over a period of centuries, often going back to Colonization

475px, Map of the year each country achieved List of sovereign states by date of formation, independence.

Colonization (British English: colonisation) is a process of establishing occupation of or control over foreign territories or peoples f ...

and, in some accounts, to the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

. As the application of the term has expanded, its meaning has shifted along five distinct but often parallel axes: the moral, the economic, the systemic, the cultural, and the temporal. Those changes reflect—among other shifts in sensibility—a growing unease, even great distaste, with the pervasiveness of such power, specifically, Western power.[

]Walter Rodney

Walter Anthony Rodney (23 March 1942 – 13 June 1980) was a Guyanese historian, political activist and academic. His notable works include '' How Europe Underdeveloped Africa'', first published in 1972. He was assassinated in Georgetown, ...

, in his 1972 How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, proposes the idea that imperialism is a phase of capitalism "in which Western European capitalist countries, the US, and Japan established political, economic, military and cultural hegemony over other parts of the world which were initially at a lower level and therefore could not resist domination."

Justification and issues

Orientalism and imaginative geography

Imperial control, territorial and cultural

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

, is justified through discourse

Discourse is a generalization of the notion of a conversation to any form of communication. Discourse is a major topic in social theory, with work spanning fields such as sociology, anthropology, continental philosophy, and discourse analysis. F ...

s about the imperialists' understanding of different spaces.[Hubbard, P., & Kitchin, R. Eds. ''Key Thinkers on Space and Place'', 2nd. Ed. Los Angeles, Calif:Sage Publications. 2010. p. 239.] Conceptually, imagined geographies explain the limitations of the imperialist understanding of the societies of the different spaces inhabited by the non–European Other.Orientalism

In art history, literature, and cultural studies, Orientalism is the imitation or depiction of aspects of the Eastern world (or "Orient") by writers, designers, and artists from the Western world. Orientalist painting, particularly of the Middle ...

'' (1978), Edward Said

Edward Wadie Said (1 November 1935 – 24 September 2003) was a Palestinian-American academic, literary critic, and political activist. As a professor of literature at Columbia University, he was among the founders of Postcolonialism, post-co ...

said that the West developed the concept of The Orient

The Orient is a term referring to the East in relation to Europe, traditionally comprising anything belonging to the Eastern world. It is the antonym of the term ''Occident'', which refers to the Western world.

In English, it is largely a meto ...

—an imagined geography of the Eastern world

The Eastern world, also known as the East or historically the Orient, is an umbrella term for various cultures or social structures, nations and philosophical systems, which vary depending on the context. It most often includes Asia, the ...

—which functions as an essentializing discourse that represents neither the ethnic diversity nor the social reality of the Eastern world. That by reducing the East into cultural essences, the imperial discourse uses place-based identities to create cultural difference

Cultural diversity is the quality of diverse or different cultures, as opposed to monoculture. It has a variety of meanings in different contexts, sometimes applying to cultural products like art works in museums or entertainment available online, ...

and psychologic distance between "We, the West" and "They, the East" and between "Here, in the West" and "There, in the East".[Said, Edward. "Imaginative Geography and its Representations: Orientalizing the Oriental", ''Orientalism''. New York:Vintage. p. 357.]

That cultural differentiation was especially noticeable in the books and paintings of early Oriental studies

Oriental studies is the academic field that studies Near Eastern and Far Eastern societies and cultures, languages, peoples, history and archaeology. In recent years, the subject has often been turned into the newer terms of Middle Eastern studie ...

, the European examinations of the Orient, which misrepresented the East as irrational and backward, the opposite of the rational and progressive West.[

]

Cartography

One of the main tools used by imperialists was cartography. Cartography

Cartography (; from , 'papyrus, sheet of paper, map'; and , 'write') is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an imagined reality) can ...

is "the art, science and technology of making maps"[ p. 2] but this definition is problematic. It implies that maps are objective representations of the world when in reality they serve very political means.power

Power may refer to:

Common meanings

* Power (physics), meaning "rate of doing work"

** Engine power, the power put out by an engine

** Electric power, a type of energy

* Power (social and political), the ability to influence people or events

Math ...

and knowledge

Knowledge is an Declarative knowledge, awareness of facts, a Knowledge by acquaintance, familiarity with individuals and situations, or a Procedural knowledge, practical skill. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is oft ...

concept.

To better illustrate this idea, Bassett focuses his analysis of the role of 19th-century maps during the "Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa was the invasion, conquest, and colonialism, colonisation of most of Africa by seven Western European powers driven by the Second Industrial Revolution during the late 19th century and early 20th century in the era of ...

".[ p. 316] He states that maps "contributed to empire by promoting, assisting, and legitimizing the extension of French and British power into West Africa".eurocentrism

Eurocentrism (also Eurocentricity or Western-centrism)

refers to viewing Western world, the West as the center of world events or superior to other cultures. The exact scope of Eurocentrism varies from the entire Western world to just the con ...

. According to Bassett, " neteenth-century explorers commonly requested Africans to sketch maps of unknown areas on the ground. Many of those maps were highly regarded for their accuracy"

Expansionism

Imperialism in pre-modern times was common in the form of expansionism

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military Imperialism, empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established p ...

through vassalage

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerai ...

and conquest

Conquest involves the annexation or control of another entity's territory through war or Coercion (international relations), coercion. Historically, conquests occurred frequently in the international system, and there were limited normative or ...

.

Cultural imperialism

The concept of cultural imperialism

Cultural imperialism (also cultural colonialism) comprises the culture, cultural dimensions of imperialism. The word "imperialism" describes practices in which a country engages culture (language, tradition, ritual, politics, economics) to creat ...

refers to the cultural influence of one dominant culture over others, i.e. a form of soft power

In politics (and particularly in international politics), soft power is the ability to co-option, co-opt rather than coerce (in contrast with hard power). It involves shaping the preferences of others through appeal and attraction. Soft power is ...

, which changes the moral, cultural, and societal worldview

A worldview (also world-view) or is said to be the fundamental cognitive orientation of an individual or society encompassing the whole of the individual's or society's knowledge, culture, and Perspective (cognitive), point of view. However, whe ...

of the subordinate culture. This means more than just "foreign" music, television or film becoming popular with young people; rather that a populace changes its own expectations of life, desiring for their own country to become more like the foreign country depicted. For example, depictions of opulent American lifestyles in the soap opera ''Dallas'' during the Cold War changed the expectations of Romanians; a more recent example is the influence of smuggled South Korean drama-series in North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

. The importance of soft power is not lost on authoritarian regimes, which may oppose such influence with bans on foreign popular culture, control of the internet and of unauthorized satellite dishes, etc. Nor is such a usage of culture recent – as part of Roman imperialism, local elites would be exposed to the benefits and luxuries of Roman culture and lifestyle, with the aim that they would then become willing participants.

Imperialism has been subject to moral or immoral censure by its critics, and thus the term "imperialism" is frequently used in international propaganda as a pejorative for expansionist and aggressive foreign policy.["Imperialism." ''International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences'', 2nd edition.]

Religious imperialism

Aspects of imperialism motivated by religious supremacism can be described as religious imperialism.

Psychological imperialism

An empire mentality

A mindset refers to an established set of attitudes of a person or group concerning culture, values, philosophy, frame of reference, outlook, or disposition. It may also arise from a person's worldview or beliefs about the meaning of life.

Som ...

may build on and bolster views contrasting "primitive" and "advanced" peoples and cultures, thus justifying and encouraging imperialist practices among participants.

Associated psychological tropes include the White Man's Burden

"The White Man's Burden" (1899), by Rudyard Kipling, is a poem about the Philippine–American War (1899–1902) that exhorts the United States to assume colonial control of the Filipino people and their country.''

In "The White Man's Burden ...

and the idea of civilizing mission

The civilizing mission (; ; ) is a political rationale for military intervention and for colonization purporting to facilitate the cultural assimilation of indigenous peoples, especially in the period from the 15th to the 20th centuries. As ...

().

Social imperialism

The political concept social imperialism

As a political term, social imperialism is the political ideology of people, parties, or nations that are, according to Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin, "socialist in words, imperialist in deeds". Some academics use this phrase to refer to governm ...

is a Marxist expression first used in the early 20th century by Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

as "socialist in words, imperialist in deeds" describing the Fabian Society

The Fabian Society () is a History of the socialist movement in the United Kingdom, British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in ...

and other socialist organizations.

Later, in a split with the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

criticized its leaders as social imperialists.

Social Darwinism

Stephen Howe has summarized his view on the beneficial effects of the colonial empires:

A controversial aspect of imperialism is the defense and justification of empire-building based on seemingly rational grounds. In

Stephen Howe has summarized his view on the beneficial effects of the colonial empires:

A controversial aspect of imperialism is the defense and justification of empire-building based on seemingly rational grounds. In ancient China

The history of China spans several millennia across a wide geographical area. Each region now considered part of the Chinese world has experienced periods of unity, fracture, prosperity, and strife. Chinese civilization first emerged in the Y ...

, Tianxia

''Tianxia'', 'all under Heaven', is a Chinese term for a historical Chinese cultural concept that denoted either the entire geographical world or the metaphysical realm of mortals, and later became associated with political sovereignty. In anc ...

denoted the lands, space, and area divinely appointed to the Emperor by universal and well-defined principles of order. The center of this land was directly apportioned to the Imperial court, forming the center of a world view that centered on the Imperial court and went concentrically outward to major and minor officials and then the common citizens, tributary states

A tributary state is a pre-modern state in a particular type of subordinate relationship to a more powerful state which involved the sending of a regular token of submission, or tribute, to the superior power (the suzerain). This token often t ...

, and finally ending with the fringe "barbarians

A barbarian is a person or tribe of people that is perceived to be primitive, savage and warlike. Many cultures have referred to other cultures as barbarians, sometimes out of misunderstanding and sometimes out of prejudice.

A "barbarian" may ...

". Tianxia's idea of hierarchy gave Chinese a privileged position and was justified through the promise of order and peace.

The purportedly scientific nature of "Social Darwinism

Charles Darwin, after whom social Darwinism is named

Social Darwinism is a body of pseudoscientific theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economi ...

" and a theory of races formed a supposedly rational justification for imperialism. Under this doctrine, the French politician Jules Ferry

Jules François Camille Ferry (; 5 April 183217 March 1893) was a French statesman and republican philosopher. He was one of the leaders of the Opportunist Republicans, Moderate Republicans and served as Prime Minister of France from 1880 to 18 ...

could declare in 1883 that "Superior races have a right, because they have a duty. They have the duty to civilize the inferior races." J. A. Hobson

John Atkinson Hobson (6 July 1858 – 1 April 1940) was an English economist and social scientist. Hobson is best known for his writing on imperialism, which influenced Vladimir Lenin, and his theory of underconsumption.

His principal and e ...

identifies this justification on general grounds as: "It is desirable that the earth should be peopled, governed, and developed, as far as possible, by the races which can do this work best, i.e. by the races of highest 'social efficiency'". The Royal Geographical Society of London and other geographical societies in Europe had great influence and were able to fund travelers who would come back with tales of their discoveries. These societies also served as a space for travellers to share these stories.[ Political geographers such as ]Friedrich Ratzel

Friedrich Ratzel (August 30, 1844 – August 9, 1904) was a German geographer and ethnographer, notable for first using the term ''Lebensraum'' ("living space") in the sense that the National Socialists later would.

Life

Ratzel's father was th ...

of Germany and Halford Mackinder

Sir Halford John Mackinder (15 February 1861 – 6 March 1947) was a British geographer, academic and politician, who is regarded as one of the founding fathers of both geopolitics and geostrategy. He was the first Principal of University Ext ...

of Britain also supported imperialism.[ Ratzel believed expansion was necessary for a state's survival and this argument dominated the discipline of ]geopolitics

Geopolitics () is the study of the effects of Earth's geography on politics and international relations. Geopolitics usually refers to countries and relations between them, it may also focus on two other kinds of State (polity), states: ''de fac ...

for decades.[ British imperialism in some sparsely-inhabited regions applied a principle now termed ]Terra nullius

''Terra nullius'' (, plural ''terrae nullius'') is a Latin expression meaning " nobody's land".

Since the nineteenth century it has occasionally been used in international law as a principle to justify claims that territory may be acquired ...

(Latin expression which stems from Roman law

Roman law is the law, legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (), to the (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Justinian I.

Roman law also den ...

meaning 'no man's land'). The British settlement in Australia in the 18th century was arguably premised on ''terra nullius'', as its settlers considered it unused by its original inhabitants. The rhetoric of colonizers being racially superior appears still to have its impact. For example, throughout Latin America "whiteness" is still prized today and various forms of blanqueamiento

Blanqueamiento in Spanish, or branqueamento in Portuguese (both meaning ''whitening''), was a social, political, and economic practice used in many post-colonial countries in the Americas and Oceania to "improve the race" (''mejorar la raza' ...

(whitening) are common.

Imperial peripheries benefited from economic efficiency

In microeconomics, economic efficiency, depending on the context, is usually one of the following two related concepts:

* Allocative or Pareto efficiency: any changes made to assist one person would harm another.

* Productive efficiency: no addit ...

improved through the building of roads, other infrastructure and introduction of new technologies. Herbert Lüthy

Herbert Lüthy (January 15, 1918 - November 16, 2002) was a Swiss historian and journalist. His book ''France Against Herself'', published in the mid-1950s, criticized French traditionalism.

Life

Born in Basel, Herbert Lüthy attended school in ...

notes that ex-colonial peoples themselves show no desire to undo the basic effects of this process. Hence moral self-criticism in respect of the colonial past is out of place.

Environmental determinism

The concept of environmental determinism

Environmental determinism (also known as climatic determinism or geographical determinism) is the study of how the physical environment predisposes societies and states towards particular economic or social developmental (or even more gener ...

served as a moral justification for the domination of certain territories and peoples. The environmental determinist school of thought held that the environment in which certain people lived determined those persons' behaviours; and thus validated their domination. Some geographic scholars under colonizing empires divided the world into climatic zones. These scholars believed that Northern Europe and the Mid-Atlantic temperate climate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (approximately 23.5° to 66.5° N/S of the Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ra ...

produced a hard-working, moral, and upstanding human being. In contrast, tropical climates allegedly yielded lazy attitudes, sexual promiscuity, exotic culture, and moral degeneracy. The tropical peoples were believed to be "less civilized" and in need of European guidance,[ therefore justifying colonial control as a ]civilizing mission

The civilizing mission (; ; ) is a political rationale for military intervention and for colonization purporting to facilitate the cultural assimilation of indigenous peoples, especially in the period from the 15th to the 20th centuries. As ...

. For instance, American geographer Ellen Churchill Semple

Ellen Churchill Semple (January 8, 1863 – May 8, 1932) was an American geographer and the first female president of the Association of American Geographers. She contributed significantly to the early development of the discipline of geography ...

argued that even though human beings originated in the tropics they were only able to become fully human in the temperate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (approximately 23.5° to 66.5° N/S of the Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ran ...

zone.European colonialism

The phenomenon of colonization is one that stretches around the globe and across time. Ancient and medieval colonialism was practiced by various civilizations such as the Phoenicians, Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Han Chinese, and Ar ...

(the first in the Americas, the second in Asia and the last in Africa), environmental determinism

Environmental determinism (also known as climatic determinism or geographical determinism) is the study of how the physical environment predisposes societies and states towards particular economic or social developmental (or even more gener ...

served to place categorically indigenous people in a racial hierarchy. Tropicality can be paralleled with Edward Said's Orientalism

In art history, literature, and cultural studies, Orientalism is the imitation or depiction of aspects of the Eastern world (or "Orient") by writers, designers, and artists from the Western world. Orientalist painting, particularly of the Middle ...

as the west's construction of the east as the "other".[ According to Said, orientalism allowed Europe to establish itself as the superior and the norm, which justified its dominance over the essentialized Orient. Orientalism is a view of a people based on their geographical location.

]

Western imperialism by country

Rome

The Roman Empire was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

in Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia, ruled by emperors

The word ''emperor'' (from , via ) can mean the male ruler of an empire. ''Empress'', the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/ grand empress dowager), or a woman who rule ...

.

Belgium

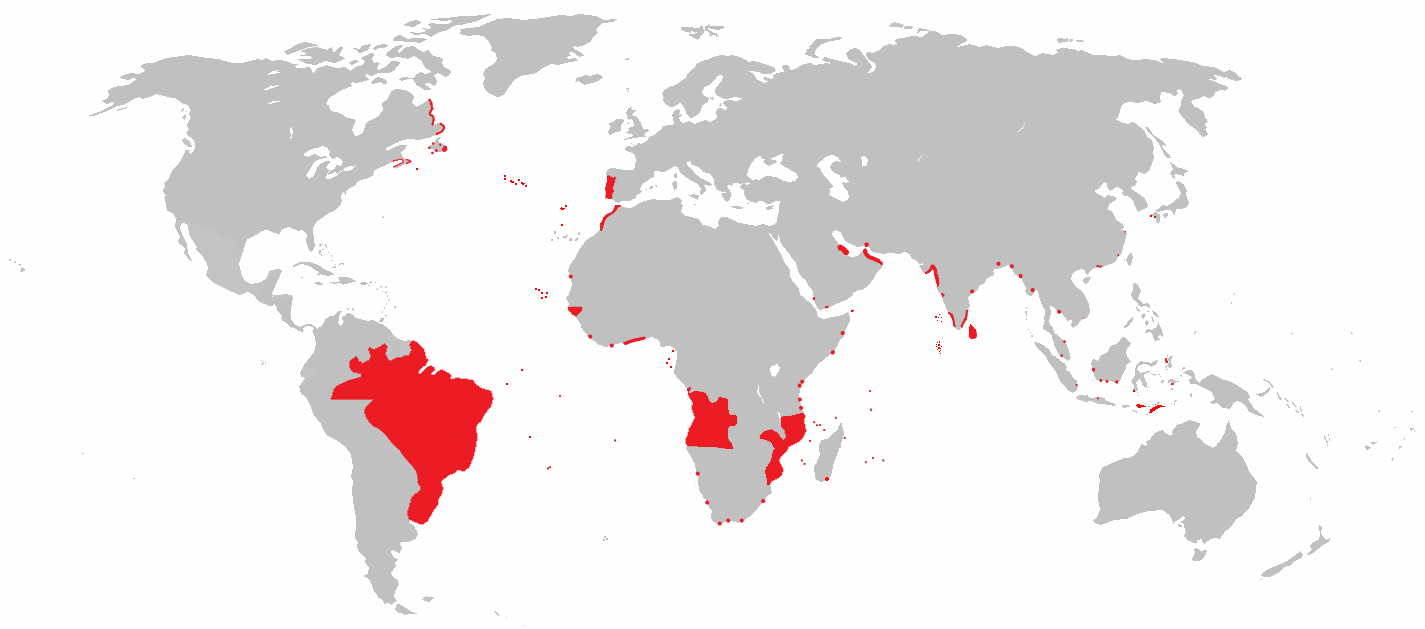

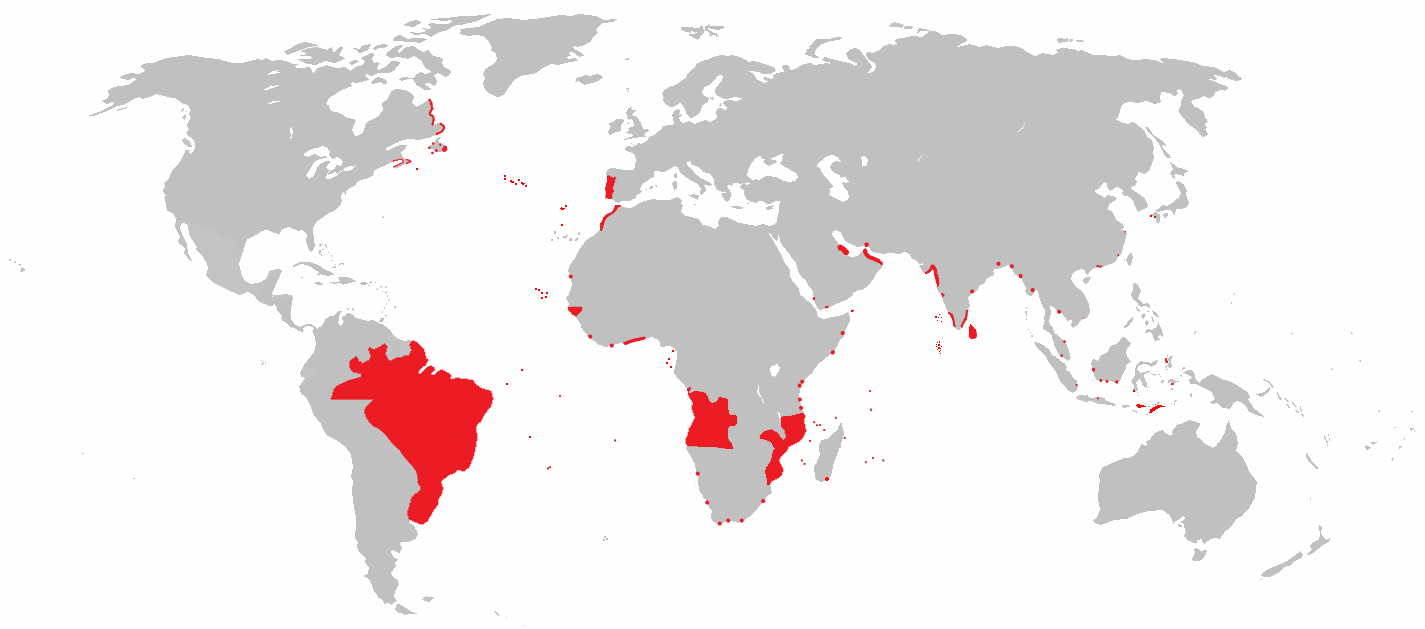

United Kingdom

England

England's imperialist ambitions can be seen as early as the 16th century as the Tudor conquest of Ireland

Ireland was conquered by the Tudor monarchs of England in the 16th century. The Anglo-Normans had Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland, conquered swathes of Ireland in the late 12th century, bringing it under Lordship of Ireland, English rule. In t ...

began in the 1530s. In 1599 the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

was established and was chartered by Queen Elizabeth in the following year.

Scotland

Between 1621 and 1699, the Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland was a sovereign state in northwest Europe, traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a Anglo-Sc ...

authorised several colonies in the Americas. Most of these colonies were either closed down or collapsed quickly for various reasons.

United Kingdom

Under the Acts of Union 1707

The Acts of Union refer to two acts of Parliament, one by the Parliament of Scotland in March 1707, followed shortly thereafter by an equivalent act of the Parliament of England. They put into effect the international Treaty of Union agree ...

, the English and Scottish kingdoms were merged, and their colonies collectively became subject to Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

(also known as the United Kingdom). The empire Great Britain would go on to found was the largest empire that the world has ever seen both in terms of landmass and population. Its power, both military and economic, remained unmatched for a few decades.

In 1767, the Anglo-Mysore Wars and other political activity caused exploitation of the East India Company causing the plundering of the local economy, almost bringing the company into bankruptcy.["British Empire" British Empire , historical state, United Kingdom , Encyclopædia Britannica Online] By the year 1670 Britain's imperialist ambitions were well off as she had colonies in Virginia, Massachusetts, Bermuda, Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Ocean at the Gulf of Fonseca, ...

, Antigua

Antigua ( ; ), also known as Waladli or Wadadli by the local population, is an island in the Lesser Antilles. It is one of the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean region and the most populous island of the country of Antigua and Barbuda. Antigua ...

, Barbados

Barbados, officially the Republic of Barbados, is an island country in the Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies and the easternmost island of the Caribbean region. It lies on the boundary of the South American ...

, Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

and Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

.John Cabot

John Cabot ( ; 1450 – 1499) was an Italians, Italian navigator and exploration, explorer. His 1497 voyage to the coast of North America under the commission of Henry VII of England, Henry VII, King of England is the earliest known Europe ...

claimed Newfoundland for the British while the French established colonies along the St. Lawrence River and claiming it as "New France". Britain continued to expand by colonizing countries such as New Zealand and Australia, both of which were not empty land as they had their own locals and cultures.proto-industrialization

Proto-industrialization is the regional development, alongside commercial agriculture, of rural handicraft production for external markets.

Cottage industries in parts of Europe between the 16th and 19th centuries had long been a niche topic of ...

, the "First" British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

was based on mercantilism

Mercantilism is a economic nationalism, nationalist economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports of an economy. It seeks to maximize the accumulation of resources within the country and use those resources ...

, and involved colonies and holdings primarily in North America, the Caribbean, and India. Its growth was reversed by the loss of the American colonies in 1776. Britain made compensating gains in India, Australia, and in constructing an informal economic empire through control of trade and finance in Latin America after the independence of Spanish and Portuguese colonies in about 1820. By the 1840s, the United Kingdom had adopted a highly successful policy of free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold Economic liberalism, economically liberal positions, while economic nationalist politica ...

that gave it dominance in the trade of much of the world. After losing its first Empire to the Americans, Britain then turned its attention towards Asia, Africa, and the Pacific. Following the defeat of Napoleonic France in 1815, the United Kingdom enjoyed a century of almost unchallenged dominance and expanded its imperial holdings around the globe. Unchallenged at sea, British dominance was later described as ''Pax Britannica

''Pax Britannica'' (Latin for , modelled after '' Pax Romana'') refers to the relative peace between the great powers in the time period roughly bounded by the Napoleonic Wars and World War I. During this time, the British Empire became the ...

'' ("British Peace"), a period of relative peace in Europe and the world (1815–1914) during which the British Empire became the global hegemon

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one state over other states, either regional or global.

In Ancient Greece (ca. 8th BC – AD 6th c.), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' ...

and adopted the role of global policeman. However, this peace was mostly a perceived one from Europe, and the period was still an almost uninterrupted series of colonial wars and disputes. The British Conquest of India, its intervention against Mehemet Ali

Muhammad Ali (4 March 1769 – 2 August 1849) was the Ottoman Albanian viceroy and governor who became the '' de facto'' ruler of Egypt from 1805 to 1848, widely considered the founder of modern Egypt. At the height of his rule in 1840, he c ...

, the Anglo-Burmese Wars

The Anglo-Burmese people, also known as the Anglo-Burmans, are a community of Eurasians of Burmese and European descent; they emerged as a distinct community through mixed relationships (sometimes permanent, sometimes temporary) between the B ...

, the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

, the Opium Wars

The Opium Wars () were two conflicts waged between China and Western powers during the mid-19th century.

The First Opium War was fought from 1839 to 1842 between China and Britain. It was triggered by the Chinese government's campaign to ...

and the Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa was the invasion, conquest, and colonialism, colonisation of most of Africa by seven Western European powers driven by the Second Industrial Revolution during the late 19th century and early 20th century in the era of ...

to name the most notable conflicts mobilised ample military means to press Britain's lead in the global conquest Europe led across the century.Porter

Porter may refer to:

Companies

* Porter Airlines, Canadian airline based in Toronto

* Porter Chemical Company, a defunct U.S. toy manufacturer of chemistry sets

* Porter Motor Company, defunct U.S. car manufacturer

* H.K. Porter, Inc., a locom ...

, p. 332.Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

began to transform Britain; by the time of the Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition that took ...

in 1851 the country was described as the "workshop of the world". The British Empire expanded to include India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, large parts of Africa and many other territories throughout the world. Alongside the formal control it exerted over its own colonies, British dominance of much of world trade meant that it effectively controlled the economies of many regions, such as Asia and Latin America. Domestically, political attitudes favoured free trade and laissez-faire policies and a gradual widening of the voting franchise. During this century, the population increased at a dramatic rate, accompanied by rapid urbanisation, causing significant social and economic stresses. To seek new markets and sources of raw materials, the Conservative Party under Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a central role in the creat ...

launched a period of imperialist expansion in Egypt, South Africa, and elsewhere. Canada, Australia, and New Zealand became self-governing dominions.

A resurgence came in the late 19th century with the

A resurgence came in the late 19th century with the Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa was the invasion, conquest, and colonialism, colonisation of most of Africa by seven Western European powers driven by the Second Industrial Revolution during the late 19th century and early 20th century in the era of ...

and major additions in Asia and the Middle East. The British spirit of imperialism was expressed by Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal Party (UK), Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually was a leading New Imperialism, imperial ...

and Lord Rosebury, and implemented in Africa by Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes ( ; 5 July 185326 March 1902) was an English-South African mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. He and his British South Africa Company founded th ...

. The pseudo-sciences of Social Darwinism and theories of race formed an ideological underpinning and legitimation during this time. Other influential spokesmen included Lord Cromer

Earl of Cromer is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom, held by members of the British branch of the Anglo-German Baring banking family.

It was created in 1901 for Evelyn Baring, 1st Viscount Cromer, long time British Consul-General ...

, Lord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), known as Lord Curzon (), was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician, explorer and writer who served as Viceroy of India ...

, General Kitchener, Lord Milner

Alfred Milner, 1st Viscount Milner, (23 March 1854 – 13 May 1925) was a British statesman and colonial administrator who played a very important role in the formulation of British foreign and domestic policy between the mid-1890s and ear ...

, and the writer Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English journalist, novelist, poet, and short-story writer. He was born in British Raj, British India, which inspired much ...

. After the First Boer War

The First Boer War (, ), was fought from 16 December 1880 until 23 March 1881 between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and Boers of the Transvaal (as the South African Republic was known while under British ad ...

, the South African Republic

The South African Republic (, abbreviated ZAR; ), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer republics, Boer republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it was annexed into the British Empire as a result ...

and Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( ; ) was an independent Boer-ruled sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeated and surrendered to the British Em ...

were recognised by the United Kingdom but eventually re-annexed after the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

. But British power was fading, as the reunited German state founded by the Kingdom of Prussia posed a growing threat to Britain's dominance. As of 1913, the United Kingdom was the world's fourth economy, behind the U.S., Russia and Germany.

Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence (), also known as the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922), Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and Unite ...

in 1919–1921 led to the сreation of the Irish Free State. But the United Kingdom gained control of former German and Ottoman colonies with the League of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate represented a legal status under international law for specific territories following World War I, involving the transfer of control from one nation to another. These mandates served as legal documents establishing th ...

. The United Kingdom now had a practically continuous line of controlled territories from Egypt to Burma and another one from Cairo to Cape Town. However, this period was also one of emergence of independence movements based on nationalism and new experiences the colonists had gained in the war.

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

decisively weakened Britain's position in the world, especially financially. Decolonization

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby Imperialism, imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholar ...

movements arose nearly everywhere in the Empire, resulting in Indian independence and partition in 1947, the self-governing dominions break away from the empire in 1949, and the establishment of independent states in the 1950s. British imperialism showed its frailty in Egypt during the Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, also known as the Second Arab–Israeli War, the Tripartite Aggression in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel, was a British–French–Israeli invasion of Egypt in 1956. Israel invaded on 29 October, having done so w ...

in 1956. However, with the United States and Soviet Union emerging from World War II as the sole superpowers, Britain's role as a worldwide power declined significantly and rapidly.

Canada

In Canada, the "imperialism" (and the related term "colonialism") has had a variety of contradictory meanings since the 19th century. In the late 19th and early 20th, to be an "imperialist" meant thinking of Canada as a part of the British nation not a separate nation. The older words for the same concepts were "loyalism

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

" or " unionism", which continued to be used as well. In mid-twentieth century Canada, the words "imperialism" and "colonialism" were used in English Canadian discourse to instead portray Canada as a victim of economic and cultural penetration by the United States. In twentieth century French-Canadian discourse the "imperialists" were all the Anglo-Saxon countries including Canada who were oppressing French-speakers and the province of Quebec

Quebec is Canada's largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, New Brunswick to the southeast and a coastal border ...

. By the early 21st century, "colonialism" was used to highlight supposed anti-indigenous attitudes and actions of Canada inherited from the British period.

Denmark

Denmark–Norway

Denmark–Norway (Danish language, Danish and Norwegian language, Norwegian: ) is a term for the 16th-to-19th-century multi-national and multi-lingual real unionFeldbæk 1998:11 consisting of the Kingdom of Denmark, the Kingdom of Norway (includ ...

(Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

after 1814) possessed overseas colonies from 1536 until 1953. At its apex there were colonies on four continents: Europe, North America, Africa and Asia. In the 17th century, following territorial losses on the Scandinavian Peninsula

The Scandinavian Peninsula is located in Northern Europe, and roughly comprises the mainlands of Sweden, Norway and the northwestern area of Finland.

The name of the peninsula is derived from the term Scandinavia, the cultural region of Denm ...

, Denmark-Norway began to develop colonies, forts, and trading posts in West Africa, the Caribbean

The Caribbean ( , ; ; ; ) is a region in the middle of the Americas centered around the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, mostly overlapping with the West Indies. Bordered by North America to the north, Central America ...

, and the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographic region of Asia below the Himalayas which projects into the Indian Ocean between the Bay of Bengal to the east and the Arabian Sea to the west. It is now divided between Bangladesh, India, and Pakista ...

. Christian IV

Christian IV (12 April 1577 – 28 February 1648) was King of Denmark and Norway and Duke of Holstein and Schleswig from 1588 until his death in 1648. His reign of 59 years and 330 days is the longest in Scandinavian history.

A member of the H ...

first initiated the policy of expanding Denmark-Norway's overseas trade, as part of the mercantilist

Mercantilism is a nationalist economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports of an economy. It seeks to maximize the accumulation of resources within the country and use those resources for one-sided trade. ...

wave that was sweeping Europe. Denmark-Norway's first colony was established at Tranquebar

Tharangambadi (), formerly Tranquebar (, ), is a town in the Mayiladuthurai district of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu on the Coromandel Coast. It lies north of Karaikal, near the mouth of a distributary named Uppanar of the Kaveri River. It wa ...

on India's southern coast in 1620. Admiral Ove Gjedde

Ove Gjedde (alternatively spelled Giedde; 27 December 1594 – 19 December 1660) was a Danish nobleman and Admiral of the Realm (), who established the first Danish colony in Asia.

Born in Tomarps (), Denmark–Norway, in 1594 to Brostrup ...

led the expedition that established the colony. After 1814, when Norway was ceded to Sweden, Denmark retained what remained of Norway's great medieval colonial holdings. One by one the smaller colonies were lost or sold. Tranquebar was sold to the British in 1845. The United States purchased the Danish West Indies

The Danish West Indies () or Danish Virgin Islands () or Danish Antilles were a Danish colony in the Caribbean, consisting of the islands of Saint Thomas with , Saint John () with , Saint Croix with , and Water Island.

The islands of St ...

in 1917. Iceland became independent in 1944. Today, the only remaining vestiges are two originally Norwegian colonies that are currently within the Danish Realm

The Danish Realm, officially the Kingdom of Denmark, or simply Denmark, is a sovereign state consisting of a collection of constituent territories united by the Constitution of Denmark, Constitutional Act, which applies to the entire territor ...

, the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ) (alt. the Faroes) are an archipelago in the North Atlantic Ocean and an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. Located between Iceland, Norway, and the United Kingdom, the islands have a populat ...

and Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

; the Faroes were a Danish county until 1948, while Greenland's colonial status ceased in 1953. They are now autonomous territories.

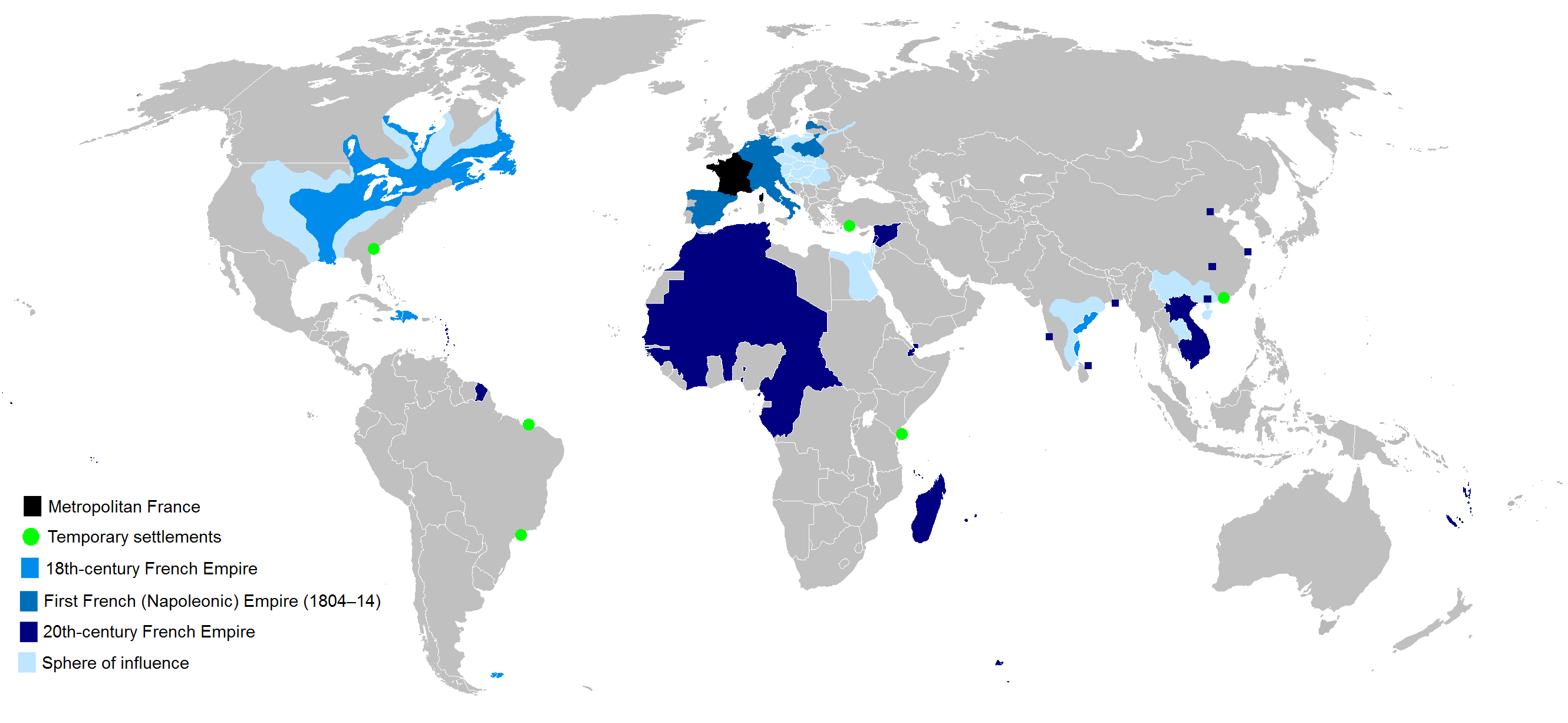

France

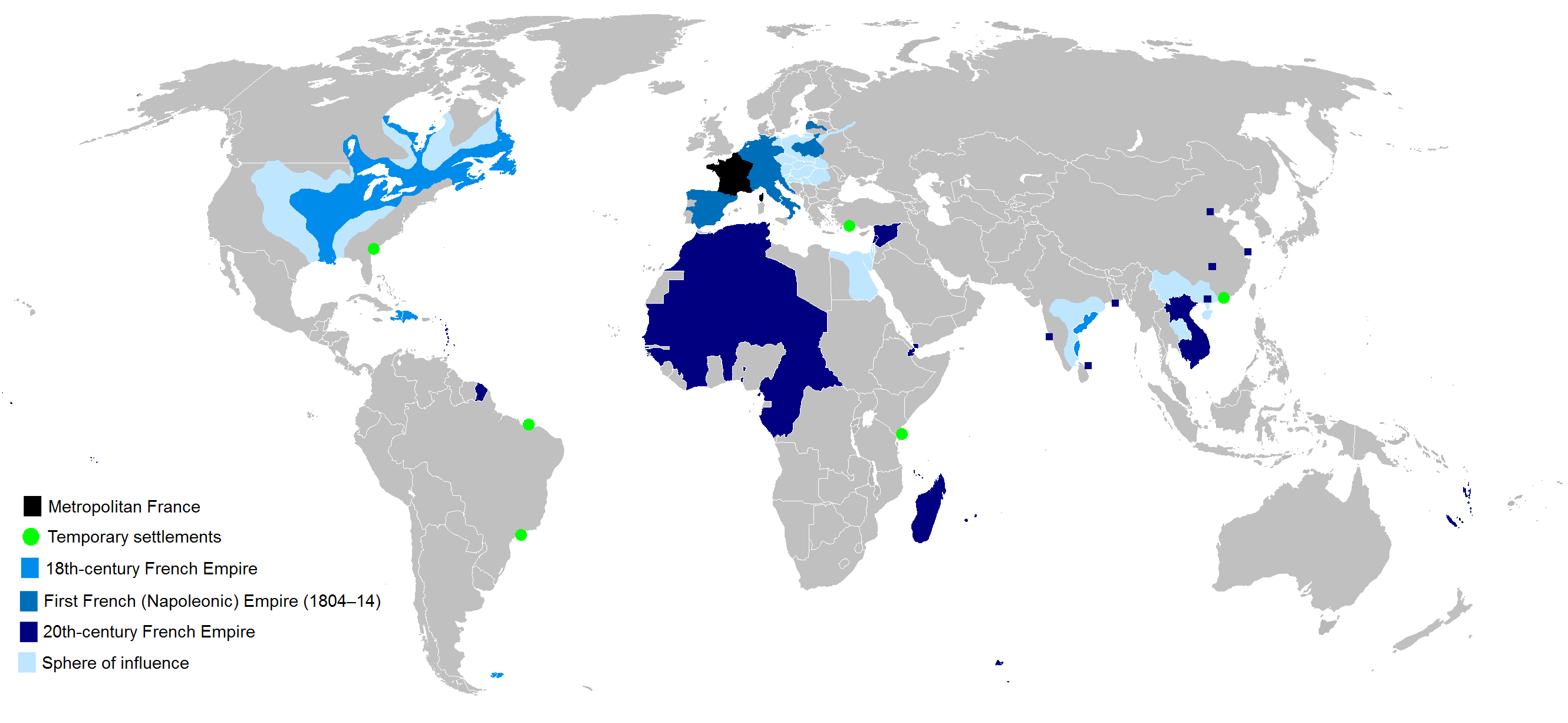

During the 16th century, the

During the 16th century, the French colonization of the Americas

France began colonizing America in the 16th century and continued into the following centuries as it established a colonial empire in the Western Hemisphere. France established colonies in much of eastern North America, on several Caribbean is ...

began with the creation of New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

. It was followed by French East India Company Compagnie des Indes () may refer to several French chartered companies involved in long-distance trading:

* First French East Indies Company, in existence from 1604 to 1614

* French West India Company, active in the Western Hemisphere from 1664 t ...

's trading posts in Africa and Asia in the 17th century. France had its "First colonial empire" from 1534 until 1814, including New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

(Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

, Acadia

Acadia (; ) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. The population of Acadia included the various ...

, Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

and Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

), French West Indies

The French West Indies or French Antilles (, ; ) are the parts of France located in the Antilles islands of the Caribbean:

* The two overseas departments of:

** Guadeloupe, including the islands of Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Les Saintes, Ma ...

(Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colonization of the Americas, French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1803. The name derives from the Spanish main city on the isl ...

, Guadeloupe, Martinique

Martinique ( ; or ; Kalinago language, Kalinago: or ) is an island in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the eastern Caribbean Sea. It was previously known as Iguanacaera which translates to iguana island in Carib language, Kariʼn ...

), French Guiana

French Guiana, or Guyane in French, is an Overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department and region of France located on the northern coast of South America in the Guianas and the West Indies. Bordered by Suriname to the west ...

, Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

(Gorée

(; "Gorée Island"; ) is one of the 19 (i.e. districts) of the city of Dakar, Senegal. It is an island located at sea from the main harbour of Dakar (), famous as a destination for people interested in the Atlantic slave trade.

Its populatio ...

), Mascarene Islands

The Mascarene Islands (, ) or Mascarenes or Mascarenhas Archipelago is a group of islands in the Indian Ocean east of Madagascar consisting of islands belonging to the Republic of Mauritius as well as the French department of Réunion. Their na ...

(Mauritius Island

Mauritius, officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island country in the Indian Ocean, about off the southeastern coast of East Africa, east of Madagascar. It includes the main island (also called Mauritius), as well as Rodrigues, Agalé ...

, Réunion) and French India

French India, formally the (), was a French colony comprising five geographically separated enclaves on the Indian subcontinent that had initially been factories of the French East India Company. They were ''de facto'' incorporated into the ...

.

Its "Second colonial empire" began with the seizure of Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

in 1830 and came for the most part to an end with the granting of independence to Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

in 1962. The French imperial history was marked by numerous wars, large and small, and also by significant help to France itself from the colonials in the world wars. France took control of Algeria in 1830 but began in earnest to rebuild its worldwide empire after 1850, concentrating chiefly in North and West Africa (French North Africa

French North Africa (, sometimes abbreviated to ANF) is a term often applied to the three territories that were controlled by France in the North African Maghreb during the colonial era, namely Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. In contrast to French ...

, French West Africa

French West Africa (, ) was a federation of eight French colonial empires#Second French colonial empire, French colonial territories in West Africa: Colonial Mauritania, Mauritania, French Senegal, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guin ...

, French Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa (, or AEF) was a federation of French colonial territories in Equatorial Africa which consisted of Gabon, French Congo, Ubangi-Shari, and Chad. It existed from 1910 to 1958 and its administration was based in Brazzav ...

), as well as South-East Asia (French Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China), officially known as the Indochinese Union and after 1941 as the Indochinese Federation, was a group of French dependent territories in Southeast Asia from 1887 to 1954. It was initial ...

), with other conquests in the South Pacific (New Caledonia

New Caledonia ( ; ) is a group of islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean, southwest of Vanuatu and east of Australia. Located from Metropolitan France, it forms a Overseas France#Sui generis collectivity, ''sui generis'' collectivity of t ...

, French Polynesia

French Polynesia ( ; ; ) is an overseas collectivity of France and its sole #Governance, overseas country. It comprises 121 geographically dispersed islands and atolls stretching over more than in the Pacific Ocean, South Pacific Ocean. The t ...

). France also twice attempted to make Mexico a colony in 1838–39 and in 1861–67 (see Pastry War

The Pastry War (; ), also known as the first French intervention in Mexico or the first Franco-Mexican war (1838–1839), began in November 1838 with the naval blockade of some Centralist Republic of Mexico, Mexican ports and the capture of the ...

and Second French intervention in Mexico

The second French intervention in Mexico (), also known as the Second Franco-Mexican War (1861–1867), was a military invasion of the Republic of Mexico by the French Empire of Napoleon III, purportedly to force the collection of Mexican de ...

).

French Republicans, at first hostile to empire, only became supportive when Germany started to build her own colonial empire. As it developed, the new empire took on roles of trade with France, supplying raw materials and purchasing manufactured items, as well as lending prestige to the motherland and spreading French civilization and language as well as Catholicism. It also provided crucial manpower in both World Wars. It became a moral justification to lift the world up to French standards by bringing Christianity and French culture. In 1884 the leading exponent of colonialism,