History Of Phagocytosis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of phagocytosis is an account of the discoveries of cells, known as

The history of phagocytosis is an account of the discoveries of cells, known as

The history of phagocytosis is an account of the discoveries of cells, known as

The history of phagocytosis is an account of the discoveries of cells, known as phagocytes

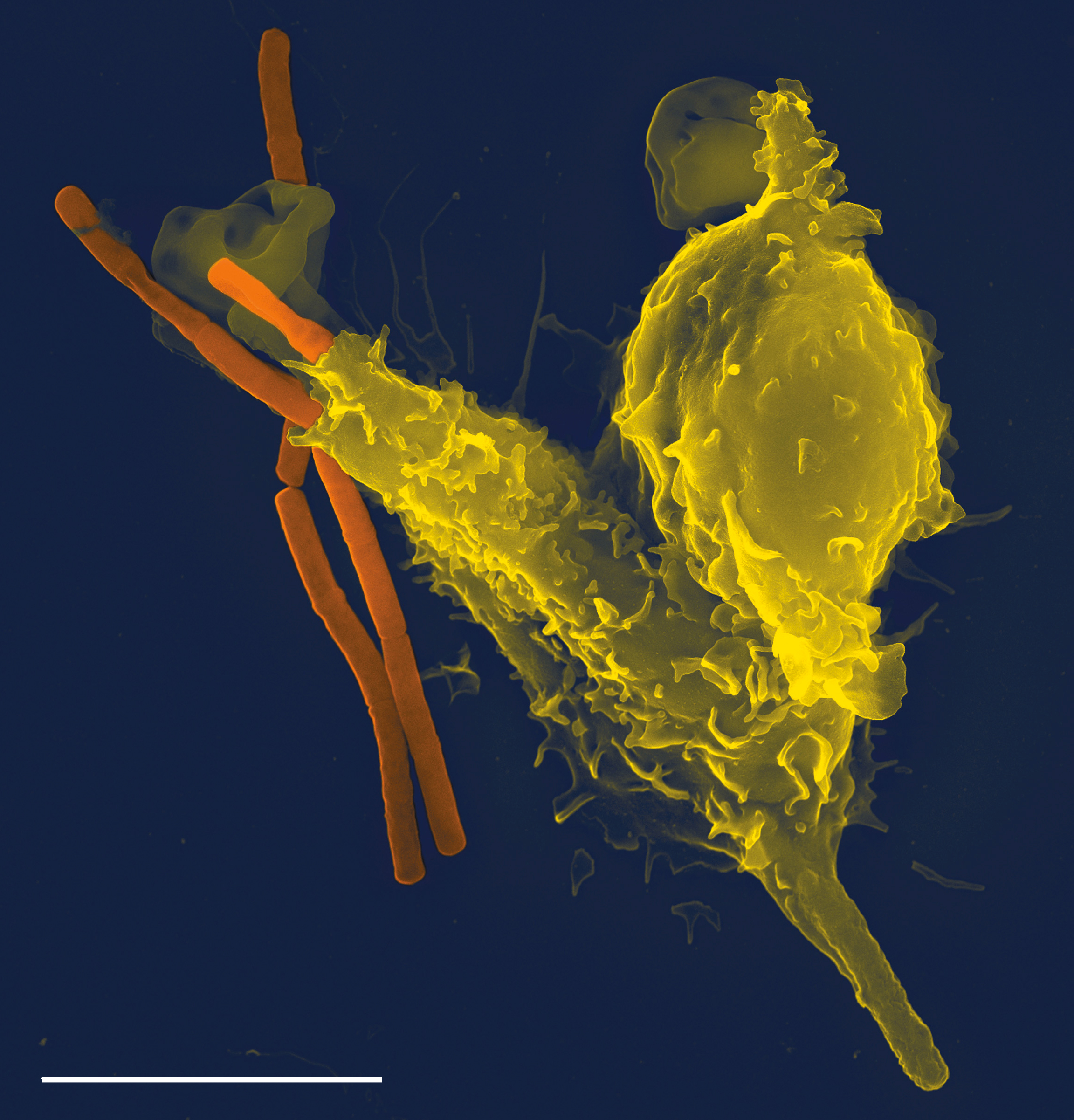

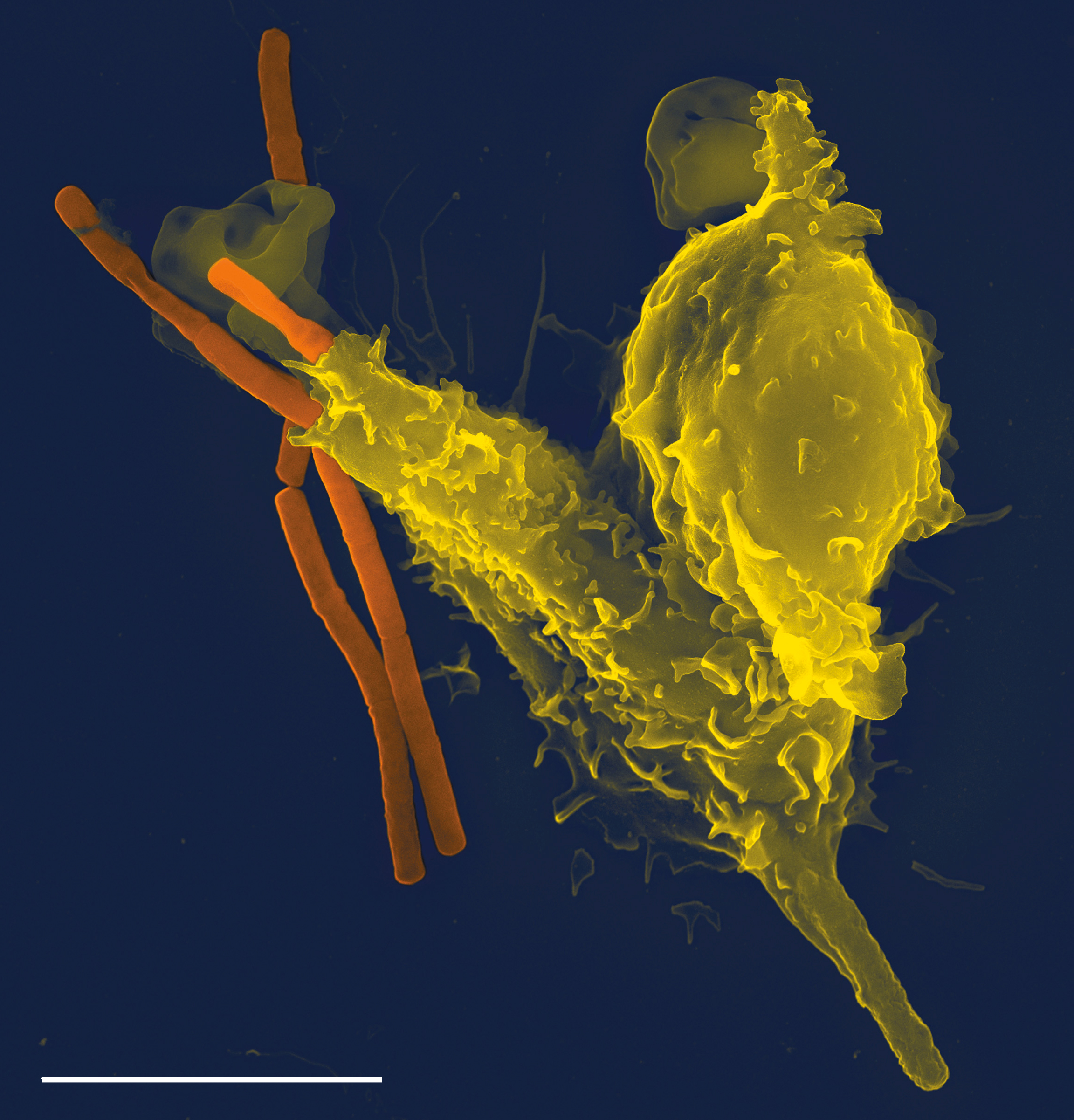

Phagocytes are cell (biology), cells that protect the body by ingesting harmful foreign particles, bacteria, and dead or Apoptosis, dying cells. Their name comes from the Greek language, Greek ', "to eat" or "devour", and "-cyte", the suffix in ...

, that are capable of eating other cells or particles, and how that eventually established the science of immunology

Immunology is a branch of biology and medicine that covers the study of Immune system, immune systems in all Organism, organisms.

Immunology charts, measures, and contextualizes the Physiology, physiological functioning of the immune system in ...

. Phagocytosis is broadly used in two ways in different organisms, for feeding in unicellular organisms (protists) and for immune response

An immune response is a physiological reaction which occurs within an organism in the context of inflammation for the purpose of defending against exogenous factors. These include a wide variety of different toxins, viruses, intra- and extracellula ...

to protect the body against infections in metazoans. Although it is found in a variety of organisms with different functions, its fundamental process is cellular ingestion of foreign (external) materials, and thus, is considered as an evolutionary conserved process.

The biological theory and concept, experimental observations and the name, phagocyte () were introduced by a Ukrainian zoologist √Člie Metchnikoff

Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov (; ‚Äď 15 July 1916), also spelled √Člie Metchnikoff, was a zoologist from the Russian Empire of Moldavian noble ancestry and alshereat archive.org best known for his research in immunology (study of immune systems) and ...

in 1883, the moment regarded as the foundation or birth of immunology. The discovery of phagocytes and the process of innate immunity earned Metchnikoff the 1908 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine () is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, acco ...

, and the epithet "father of natural immunity".

However, the cellular process was known before Metchnikoff's works, but with inconclusive descriptions. The first scientific description was from Albert von Kölliker who in 1849 reported an alga

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular microalgae, suc ...

eating a microbe. In 1862, Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; ; 16 February 1834 ‚Äď 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, natural history, naturalist, eugenics, eugenicist, Philosophy, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biology, marine biologist and artist ...

experimentally showed that some blood cells in a slug could ingest external particles. By then evidences were mounting that leucocytes can perform cell eating just like protists, but it was not until Metchnikoff showed that specific leukocytes (in his case macrophages

Macrophages (; abbreviated MPhi, ŌÜ, Mő¶ or MP) are a type of white blood cell of the innate immune system that engulf and digest pathogens, such as cancer cells, microbes, cellular debris and foreign substances, which do not have proteins that ...

) eat cell that the role of phagocytosis in immunity was realised.

Discovery of cell feeding

Phagocytosis was first observed as a process by which unicellular organisms eat their food, usually smaller organisms like protists and bacteria. The earliest definitive account was given by Swiss scientist Albert von Kölliker in 1849. As he reported in the journal '','' Kölliker described the feeding process of an amoeba-like alga, '' Actinophyrys sol'' (a heliozoan). Under microscope, he noticed that the protist engulfed and swallowed (the process now called endocytosis) a small organism, that he namedinfusoria

Infusoria is a word used to describe various freshwater microorganisms, including ciliates, copepods, Euglena, euglenoids, planktonic crustaceans, protozoa, unicellular algae and small invertebrates. Some authors (e.g., Otto B√ľtschli, B√ľtschli) ...

(a generic name for microbes at the time). Modern translation of his description reads:The creature nfusoriawhich is destined for food .e., trapped by the spines gradually reaches the surface of the animal [i.e., ''Actinophyrys''), in particular, the thread that caught it is shortened to nothing, or, as it often happens, once trapped in the thread space, the thread unwinds from around the prey when close together and at the surface of the cell body... The place on the cell surface where the caught animal is, gradually becomes a deeper and deeper pit into which the prey, which is attached everywhere to the cell surface, comes to rest. Now, by continuing to draw in the body wall, the pit gets deeper, and the prey which was previously on the edge of the ''Actinophrys'', disappears completely, and at the same time the catching threads, which still lay with their points against each other, cancel each other out and extend again. Finally, the edges "choke" the pit, so that it is flask-shaped (''flaschenformig'') all sides increasingly merging together, so that the pit completely closes and the prey is completely within the cortical cytoplasm.The general process given by Kölliker correlates with modern understanding of phagocytosis as a feeding method. The thread and thread space are pseudopodia, gradually deepening pit is the endocytosis, the ''flaschenformig'' structure is the phagosome.

Discovery of phagocytic immune cells

Eosinophils

The first demonstration of phagocytosis as a property of leukocytes, the immune cells, was from the German zoologistErnst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; ; 16 February 1834 ‚Äď 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, natural history, naturalist, eugenics, eugenicist, Philosophy, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biology, marine biologist and artist ...

. In 1846, English physician Thomas Wharton Jones

Thomas Wharton Jones (9 January 1808 ‚Äď 7 November 1891) was a ophthalmologist and physiologist of the 19th century.

Biography

Jones's father was Richard Jones, a native of London. Richard Jones had moved north to St Andrews and was working w ...

had discovered that a group of leucocytes

White blood cells (scientific name leukocytes), also called immune cells or immunocytes, are cells of the immune system that are involved in protecting the body against both infectious disease and foreign entities. White blood cells are genera ...

, which he called "granule-cell" (later renamed and identified as eosinophil

Eosinophils, sometimes called eosinophiles or, less commonly, acidophils, are a variety of white blood cells and one of the immune system components responsible for combating multicellular parasites and certain infections in vertebrates. Along wi ...

), could change shape, the phenomenon later called amoeboid movement. Jones studied the bloods of different animals, from invertebrates to mammals, and noticed the blood of a marine fish ( skate) had cells that could move by themselves and remarked that "the granule-cells at first presented most remarkable changes of shape." Other scientists confirmed his findings, however, among them, German physician Johann Nathanael Lieberk√ľhn in 1854 concluded that the movement was not for ingesting food or particles.

Disproving Lieberk√ľhn's conclusion, Haeckel discovered that such cells could indeed ingest particles, even experimentally introduced ones. In 1862, Haeckel injected an Indian ink

India ink (British English: Indian ink; also Chinese ink) is a simple black or coloured ink once widely used for writing and printing and now more commonly used for drawing and outlining, especially when inking comic books and comic strips. In ...

(or indigo

InterGlobe Aviation Limited (d/b/a IndiGo), is an India, Indian airline headquartered in Gurgaon, Haryana, India. It is the largest List of airlines of India, airline in India by passengers carried and fleet size, with a 64.1% domestic market ...

) into a sea slug,'' Tethys'', and observed how the colour was taken up by the tissues. As he extracted the blood, he found that the colour particles accumulated in the cytoplasm of some blood cells. It was a direct evidence of phagocytosis by immune cells. Haeckel reported his experiment in a monograph ''Die Radiolarien (Rhizopoda Radiaria): Eine Monographie.''

In 1869, Joseph Gibbon Richardson at the Pennsylvania Hospital

Pennsylvania Hospital is a Private hospital, private, non-profit, 515-bed teaching hospital located at 800 Spruce Street (Philadelphia), Spruce Street in Center City, Philadelphia, Center City Philadelphia, The hospital was founded on May 11, 17 ...

observed amoeboid leukocytes from his own salivary cells, urine of an individual hospitalised for kidney and bladder problem and urine from a cystitis

A urinary tract infection (UTI) is an infection that affects a part of the urinary tract. Lower urinary tract infections may involve the bladder (cystitis) or urethra ( urethritis) while upper urinary tract infections affect the kidney (py ...

case. He noticed from the pus sample that one cell had moving "molecule" inside, the cell gradually enlarged and ultimately ruptured like "that of swarm of bees from a hive". He hypothesised: " tseems not improbably that the white corpuscles, either in the capillaries or lymphatic glands, collect during their amoebaform icmovements, those germs of bacteria, which my own experiments indicate always exist in the blood to a greater or less amount." Although generally overlooked in the study of phagocytosis, after it was originally published in the ''Pennsylvania Hospital Report'', it was reproduced in other journals.

Epithelial cells

In 1869, Russian physician Kranid Slavjansky published his research on injection of guinea pigs and rabbits with indigo andcinnabar

Cinnabar (; ), or cinnabarite (), also known as ''mercurblende'' is the bright scarlet to brick-red form of Mercury sulfide, mercury(II) sulfide (HgS). It is the most common source ore for refining mercury (element), elemental mercury and is t ...

in (later renamed '' Virchows Archiv'')''.'' Slavjansky found that leukocytes easily take up the indigo and cinnabar as do the cells of the respiratory tract ( alveoli). He noticed that the alveolar cells behaved like the leukocytes as they became distributed in the alveoli and the bronchial mucus, the observation of which made him to suggest that the tissue cells were the source of particle up-take in the lungs. He concluded:[As those cells contain cinnabar, it is natural to suppose them to be white blood cells migrating out of the vessels and finding no free pigment in the pulmonary alveoli, as is the case in the experiments in which cinnabar is introduced into the blood after introducing indigo into the lungs two days before cinnabar cells appear... either they are migrated white blood cells which have undergone mucus metamorphosis and have thus become mucus corpuscles, or they can come from the metamorphosed columnar epithelium of the bronchial mucosa.]A Canadian physician William Osler at McGill College reported "On the pathology of miner's lung" in ''Canada Medical and Surgical Journal'' in 1875. Osler had examined a case of black lung disease ( pneumoconiosis) in two miners. From an autopsy of one who died from the disease, he found leukocytes and lung cells (alveolar cells) that contained the coal (carbon) particles. For the blood cells, he was not convinced that the coal particles were taken up by the cells; instead suggesting that "they must be regarded as the original cell elements of the alveoli", conceding that he lacked "the necessary knowledge to decide." But on the lung cells, his observation was clear, remarking:

Inside all of these ung cellsthe carbon particles exist in extraordinary numbers, filling the cells in different degrees. Some are so densely crowded that not a trace of cell substance can be detected, more commonly a rim of protoplasm remains free, or at a spot near the circumference, the nucleus, which in these cells is almost always eccentric, is seen uncovered... One most curious specimen was observed: on an elongated piece of carbon three cells were attached, one at either end, and a third in the middle; so that the whole had a striking resemblance to a dumbbell. I could hardly credit this at first, until, by touching top-cover with a needle and causing the whole to roll over, I quite satisfied myself that the ends of the rod were completely imbedded in the corpuscles, and the middle portion entirely surrounded by another.Oslar's report continued with his experimental observation. He injected Indian ink into the axillae and lungs of kittens. On autopsy of a two-day-old kitten, he noticed leukocytes and large tissue cells, which showed amoeboid movements, containing the ink. However, he could not work out how the ink spread inside the cells, as he accidentally dropped and broke his slide. From a four-week-old kitten, he found that the ink also accumulated in almost all the blood and lung cells, and such cells were so crowded that under a microscope "hardly anything could be seen. He was convinced that there was a cellular process of up-taking particles ("irritating materials" as he called them), which he considered as an "intravasation" or "ingestion", as he concluded:

Here we have to do with an intravasation, or rather an ingestion of the coloured corpuscles within others. Many deny this, but as far as my observation goes there can be no doubt of the fact. In these corpuscles as many as six to ten were seen, in others again the outlines of the red corpuscles could not be detected, as if the cells had absorbed only the colouring matter.

Discovery of macrophage

Groundwork

The phagocytic property of macrophage, a specialised leukocyte, and its role in immunity was discovered by Ukrainian zoologist √Člie Metchnikoff. However, he did not discover phagocytes or phagocytosis, as is often depicted in books. Metchnikoff had been working as professor of zoology and comparative anatomy at the University of Odessa, Ukraine (then Russian Empire), since 1870. In 1880, he had nervous breakdown, partly due to her wife Olga Belokopytova's terminal typhoid fever, and attempted suicide by self-injecting with blood sample from blood from an individual with relapsing fever. By then he had keen interest in Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection, and had been investigating the origin of metazoans. Based on the knowledge of cell eating in primitive metazoans, Metchnikoff believed that the common ancestor of metazoan must be a simple cell-eating organism. His initial experimental observation in 1880 in Naples, Italy, showed that such intracellular digestion does occur in theparenchyma

upright=1.6, Lung parenchyma showing damage due to large subpleural bullae.

Parenchyma () is the bulk of functional substance in an animal organ such as the brain or lungs, or a structure such as a tumour. In zoology, it is the tissue that ...

(tissue cells) of coelenterates, and became convinced that the original metazoan must be like that. He called this hypothetical metazoan ancestor ''parenchymella'' (later commonly known as ''phagocytella''; the term parechymella adopted for the name of the larvae of demosponges.) This was a direct contradiction to the hypothesis of Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; ; 16 February 1834 ‚Äď 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, natural history, naturalist, eugenics, eugenicist, Philosophy, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biology, marine biologist and artist ...

, a German zoologist and staunch supporter of Darwin's theory. In 1872, Haeckel had formulated a theory (as part of his evolutionary theory called biogenetic law) that a metazoan ancestor must be like a gastrula

Gastrulation is the stage in the early embryonic development of most animals, during which the blastula (a single-layered hollow sphere of Cell (biology), cells), or in mammals, the blastocyst, is reorganized into a two-layered or three-layered e ...

, an embryonic stage undergoing invagination

Invagination is the process of a surface folding in on itself to form a cavity, pouch or tube. In developmental biology, invagination of Epithelium, epithelial sheets occurs in many contexts during Animal embryonic development, embryonic developme ...

as seen in chordates. He named the hypothetical ancestor ''gastrea.''

Experimental discovery

To strengthen his parenchymella theory, Metchnikoff thought about several ways to look for cell eating as a fundamental process in metazoans. In the summer of 1880, he resigned from the University of Odessa and moved toMessina

Messina ( , ; ; ; ) is a harbour city and the capital city, capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of 216,918 inhabitants ...

, a seashore city in Sicily, where he could conduct a private research. His initial study on sponges indicated that the mesoderm

The mesoderm is the middle layer of the three germ layers that develops during gastrulation in the very early development of the embryo of most animals. The outer layer is the ectoderm, and the inner layer is the endoderm.Langman's Medical ...

al and endoderm

Endoderm is the innermost of the three primary germ layers in the very early embryo. The other two layers are the ectoderm (outside layer) and mesoderm (middle layer). Cells migrating inward along the archenteron form the inner layer of the gastr ...

al (body tissue wall) cells performed amoeboid movements and cell eating. His earlier experiments on planarian

Planarians (triclads) are free-living flatworms of the class Turbellaria, order Tricladida, which includes hundreds of species, found in freshwater, marine, and terrestrial habitats.pp 3., "Planarians (the popular name for the group as a whole ...

worms already showed that the endoderm is formed by migrating cells, and not by invagination. His critical study came from the larvae ( bipinnaria) of a starfish, ''Astropecten pentacanthus'' (later reclassified as '' Astropecten irregularis'').

Metchnikoff observed that the body covering of the transparent starfish consisted of the outer (ectoderm

The ectoderm is one of the three primary germ layers formed in early embryonic development. It is the outermost layer, and is superficial to the mesoderm (the middle layer) and endoderm (the innermost layer). It emerges and originates from the o ...

) and internal (endoderm) layers, and that the space in between the layers are filled with moving endodermal cells. When he injected carmine

Carmine ()also called cochineal (when it is extracted from the Cochineal, cochineal insect), cochineal extract, crimson Lake pigment, lake, or carmine lake is a pigment of a bright-red color obtained from the aluminium coordination complex, compl ...

stain (a red dye) into the starfish, he found that the stain was taken up (eaten) by the amoeboid cells as they turned red in colour. He remarked: "I found it an easy matter to demonstrate that these elements seized foreign bodies of very varied nature by means of their living processes, and certain of these bodies underwent a true digestion within the amoeboid cells." Then, he conceived a novel idea that if the cells could eat external particles, they must be responsible for eating harmful materials and pathogens like bacteria to protect the body ‚Äď the key process to immunity.

It was one afternoon in December 1880, when he stayed home alone while his family went to a circus show that he momentarily realised that his idea could be put to test by piercing live starfish larvae. He collected fresh specimens from the seashore and a few rose thorns on the way home. He discovered what he hypothesised, that the amoeboid cell gathers round the rose thorn as if to eat when it pierced through the skin, and predicted that the same would be true in humans as a form of body defence. Recapitulating the experiment, he said:I hypothesized that if my presumption was correct, a thorn introduced into the body of a starfish larva, devoid of blood vessels and nervous system, would have to be rapidly encircled by the motile cells, similarly to what happens to a human finger with a splinter. No sooner said than done. In the shrubbery of our home, the same shrubbery where we had just a few days before assembled a 'Christmas tree' for the children on a mandarin bush, I picked up some rose thorns to introduce them right away under the skin of the superb starfish larva, as transparent as water. I was so excited I couldn't fall asleep all night in trepidation of the result of my experiment, and the next morning, at a very early hour, I observed with immense joy that the experiment was a perfect success! This experiment formed the basis for the theory of phagocytosis, to whose elaboration I devoted the next 25 years of my life. Thus, it was in Messina that the turning point in my scientific life took place.

References

{{Reflist History of medicine Immunology Cellular processes