History Of Nuclear Power on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

This is a history of

In the United States, where Fermi and Szilárd had both emigrated, the discovery of the nuclear chain reaction led to the creation of the first man-made reactor, the

In the United States, where Fermi and Szilárd had both emigrated, the discovery of the nuclear chain reaction led to the creation of the first man-made reactor, the

The first organization to develop nuclear power was the

The first organization to develop nuclear power was the

IDO-19313: Additional Analysis of the SL-1 Excursion

Final Report of Progress July through October 1962'', 21 November 1962, Flight Propulsion Laboratory Department, General Electric Company, Idaho Falls, Idaho, U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, Division of Technical Information. The event was eventually rated at 4 on the seven-level INES scale. On 16 September 1967, the Pathfinder Nuclear Station near Sioux Falls, South Dakota, open for about a year, suffered an accident which caused the one year old plant to be retired permanently when an operator opened a valve too fast. Another serious accident happened in 1968, when one of the two liquid-metal-cooled reactors on board the underwent a

The total global installed nuclear capacity initially rose relatively quickly, rising from less than 1

The total global installed nuclear capacity initially rose relatively quickly, rising from less than 1  The

The

Cahiers d'histoire, published 2007, accessed 11 April 2011 France would construct 25 fission-electric stations, installing 56 mostly PWR design reactors over the next 15 years, though foregoing the 100 reactors initially charted in 1973, for the 1990s. In 2019, 71% of French electricity was generated by 58 reactors, the highest percentage by any nation in the world. Some local opposition to nuclear power emerged in the U.S. in the early 1960s, beginning with the proposed

Opposing nuclear power: past and present

''Social Alternatives'', Vol. 26, No. 2, Second Quarter 2007, pp. 43–47. In the early 1970s, there were large protests about a proposed nuclear power plant in

Public Acceptance of New Technologies

Routledge, pp. 375–376.Robert Gottlieb (2005)

Forcing the Spring: The Transformation of the American Environmental Movement

Revised Edition, Island Press, p. 237. By the mid-1970s, anti-nuclear activism had gained a wider appeal and influence, and nuclear power began to become an issue of major public protest.Walker, J. Samuel (2004).

Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective

' (Berkeley: University of California Press), pp. 10–11. In some countries, the nuclear power conflict "reached an intensity unprecedented in the history of technology controversies". In May 1979, an estimated 70,000 people, including then governor of California

/ref> Together with relatively minor percentage increases in the total quantity of steel, piping, cabling and concrete per unit of installed

/ref> in large part due to the pressure-group litigation strategy, of launching lawsuits against each proposed U.S construction proposal, keeping private utilities tied up in court for years, one of which having reached the supreme court in 1978 (see

In the early 2000s, the nuclear industry was expecting a nuclear renaissance, an increase in the construction of new reactors, due to concerns about carbon dioxide emissions. However, in 2009, Petteri Tiippana, the director of nuclear power plant division in the Finnish

In the early 2000s, the nuclear industry was expecting a nuclear renaissance, an increase in the construction of new reactors, due to concerns about carbon dioxide emissions. However, in 2009, Petteri Tiippana, the director of nuclear power plant division in the Finnish

Reuters, published 2011-03-14, accessed 14 March 2011 Germany approved plans to close all its reactors by 2022 (Following the energy crisis caused by the

Piers Morgan on CNN, published 2011-03-17, accessed 17 March 2011

xinhuanet.com, published 2011-03-18, accessed 17 March 2011 In 2011 the

The

The

nuclear power

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced by ...

as realized through the first artificial fission

Fission, a splitting of something into two or more parts, may refer to:

* Fission (biology), the division of a single entity into two or more parts and the regeneration of those parts into separate entities resembling the original

* Nuclear fissio ...

of atoms that would lead to the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

and, eventually, to using nuclear fission to generate electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter possessing an electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described by Maxwel ...

.

Origins

In 1932, physicistsJohn Cockcroft

Sir John Douglas Cockcroft (27 May 1897 – 18 September 1967) was an English nuclear physicist who shared the 1951 Nobel Prize in Physics with Ernest Walton for their splitting of the atomic nucleus, which was instrumental in the developmen ...

, Ernest Walton

Ernest Thomas Sinton Walton (6 October 1903 – 25 June 1995) was an Irish nuclear physicist who shared the 1951 Nobel Prize in Physics with John Cockcroft "for their pioneer work on the transmutation of atomic nuclei by artificially accelerate ...

, and Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who was a pioneering researcher in both Atomic physics, atomic and nuclear physics. He has been described as "the father of nu ...

discovered that when lithium atoms were "split" by protons from a proton accelerator, immense amounts of energy were released in accordance with the principle of mass–energy equivalence

In physics, mass–energy equivalence is the relationship between mass and energy in a system's rest frame. The two differ only by a multiplicative constant and the units of measurement. The principle is described by the physicist Albert Einstei ...

. However, they and other nuclear physics pioneers Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (, ; ; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish theoretical physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and old quantum theory, quantum theory, for which he received the No ...

and Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

believed harnessing the power of the atom for practical purposes anytime in the near future was unlikely. The same year, Rutherford's doctoral student James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick (20 October 1891 – 24 July 1974) was an English nuclear physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1935 for his discovery of the neutron. In 1941, he wrote the final draft of the MAUD Report, which inspired t ...

discovered the neutron. Experiments bombarding materials with neutrons led Frédéric

Frédéric and Frédérick are the French versions of the common male given name Frederick. They may refer to:

In artistry:

* Frédéric Back, Canadian award-winning animator

* Frédéric Bartholdi, French sculptor

* Frédéric Bazille, Impr ...

and Irène Joliot-Curie

Irène Joliot-Curie (; ; 12 September 1897 – 17 March 1956) was a French chemist and physicist who received the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with her husband, Frédéric Joliot-Curie, for their discovery of induced radioactivity. They were ...

to discover induced radioactivity

Induced radioactivity, also called artificial radioactivity or man-made radioactivity, is the process of using radiation to make a previously stable material radioactive. The husband-and-wife team of Irène Joliot-Curie and Frédéric Joliot-Curie ...

in 1934, which allowed the creation of radium

Radium is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Ra and atomic number 88. It is the sixth element in alkaline earth metal, group 2 of the periodic table, also known as the alkaline earth metals. Pure radium is silvery-white, ...

-like elements. Further work by Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian and naturalized American physicist, renowned for being the creator of the world's first artificial nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1, and a member of the Manhattan Project ...

in the 1930s focused on using slow neutron

The neutron detection temperature, also called the neutron energy, indicates a free neutron's kinetic energy, usually given in electron volts. The term ''temperature'' is used, since hot, thermal and cold neutrons are moderated in a medium with ...

s to increase the effectiveness of induced radioactivity. Experiments bombarding uranium with neutrons led Fermi to believe he had created a new transuranic element

The transuranium (or transuranic) elements are the chemical elements with atomic number greater than 92, which is the atomic number of uranium. All of them are radioactively unstable and decay into other elements. Except for neptunium and pluton ...

, which was dubbed ''hesperium

''Ausenium'' (atomic symbol Ao) and ''Hesperium'' (atomic symbol Es) were the names initially assigned to the transuranic elements with atomic numbers 93 and 94, respectively. The discovery of the elements, now discredited, was made by Enrico Fermi ...

''.

In 1938, German chemists Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn (; 8 March 1879 – 28 July 1968) was a German chemist who was a pioneer in the field of radiochemistry. He is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry and discoverer of nuclear fission, the science behind nuclear reactors and ...

and Fritz Strassmann

Friedrich Wilhelm Strassmann (; 22 February 1902 – 22 April 1980) was a German chemist who, with Otto Hahn in December 1938, identified the element barium as a product of the bombardment of uranium with neutrons. Their observation was the key ...

, along with Austrian physicist Lise Meitner

Elise Lise Meitner ( ; ; 7 November 1878 – 27 October 1968) was an Austrian-Swedish nuclear physicist who was instrumental in the discovery of nuclear fission.

After completing her doctoral research in 1906, Meitner became the second woman ...

and Meitner's nephew, Otto Robert Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch (1 October 1904 – 22 September 1979) was an Austrian-born British physicist who worked on nuclear physics. With Otto Stern and Immanuel Estermann, he first measured the magnetic moment of the proton. With his aunt, Lise M ...

, conducted experiments with the products of neutron-bombarded uranium, as a means of further investigating Fermi's claims. They determined that the relatively tiny neutron split the nucleus of the massive uranium atoms into two roughly equal pieces, contradicting Fermi. This was an extremely surprising result; all other forms of nuclear decay

Radioactive decay (also known as nuclear decay, radioactivity, radioactive disintegration, or nuclear disintegration) is the process by which an unstable atomic nucleus loses energy by radiation. A material containing unstable nuclei is conside ...

involved only small changes to the mass of the nucleus, whereas this process—dubbed "fission" as a reference to biology—involved a complete rupture of the nucleus. Numerous scientists, including Leó Szilárd

Leo Szilard (; ; born Leó Spitz; February 11, 1898 – May 30, 1964) was a Hungarian-born physicist, biologist and inventor who made numerous important discoveries in nuclear physics and the biological sciences. He conceived the nuclear ...

, who was one of the first, recognized that if fission reactions released additional neutrons, a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction

In nuclear physics, a nuclear chain reaction occurs when one single nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more subsequent nuclear reactions, thus leading to the possibility of a self-propagating series or "positive feedback loop" of thes ...

could result. Once this was experimentally confirmed and announced by Frédéric Joliot-Curie in 1939, scientists in many countries (including the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and the Soviet Union) petitioned their governments for support of nuclear fission research, just on the cusp of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, for the development of a nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear exp ...

.

First nuclear reactors

In the United States, where Fermi and Szilárd had both emigrated, the discovery of the nuclear chain reaction led to the creation of the first man-made reactor, the

In the United States, where Fermi and Szilárd had both emigrated, the discovery of the nuclear chain reaction led to the creation of the first man-made reactor, the research reactor

Research reactors are nuclear fission-based nuclear reactors that serve primarily as a neutron source. They are also called non-power reactors, in contrast to power reactors that are used for electricity production, heat generation, or maritim ...

known as Chicago Pile-1

Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1) was the first artificial nuclear reactor. On 2 December 1942, the first human-made self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was initiated in CP-1 during an experiment led by Enrico Fermi. The secret development of the react ...

, which achieved criticality on 2 December 1942. The reactor's development was part of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

, the Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

effort to create atomic bombs during World War II. It led to the building of larger single-purpose production reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction. They are used for commercial electricity, marine propulsion, weapons production and research. Fissile nuclei (primarily uranium-235 or plutonium-2 ...

s, such as the X-10 Pile

The X-10 Graphite Reactor is a decommissioned nuclear reactor at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Formerly known as the Clinton Pile and X-10 Pile, it was the world's second artificial nuclear reactor (after Enrico Fermi's ...

, for the production of weapons-grade plutonium

Weapons-grade nuclear material is any fissionable nuclear material that is pure enough to make a nuclear weapon and has properties that make it particularly suitable for nuclear weapons use. Plutonium and uranium in grades normally used in nucl ...

for use in the first nuclear weapons. The United States tested the first nuclear weapon in July 1945, the Trinity test

Trinity was the first detonation of a nuclear weapon, conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. MWT (11:29:21 GMT) on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was of an implosion-design plutonium bomb, or "gadg ...

, with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

On 6 and 9 August 1945, the United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively, during World War II. The aerial bombings killed between 150,000 and 246,000 people, most of whom were civili ...

taking place the following month.

In August 1945, the first widely distributed account of nuclear energy, the pocketbook ''The Atomic Age'', was released. It discussed the peaceful future uses of nuclear energy and depicted a future where fossil fuels

A fossil fuel is a flammable carbon compound- or hydrocarbon-containing material formed naturally in the Earth's crust from the buried remains of prehistoric organisms (animals, plants or microplanktons), a process that occurs within geologica ...

would go unused. Nobel laureate Glenn Seaborg

Glenn Theodore Seaborg ( ; April 19, 1912February 25, 1999) was an American chemist whose involvement in the synthesis, discovery and investigation of ten transuranium elements earned him a share of the 1951 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. His work i ...

, who later chaired the United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by the U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President Harry ...

, is quoted as saying "there will be nuclear powered earth-to-moon shuttles, nuclear powered artificial hearts, plutonium heated swimming pools for SCUBA divers, and much more".

In the same month, with the end of the war, Seaborg and others would file hundreds of initially classified patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an sufficiency of disclosure, enabling discl ...

s, most notably Eugene Wigner

Eugene Paul Wigner (, ; November 17, 1902 – January 1, 1995) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who also contributed to mathematical physics. He received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1963 "for his contributions to the theory of th ...

and Alvin Weinberg

Alvin Martin Weinberg (; April 20, 1915 – October 18, 2006) was an American nuclear physicist who was the administrator of Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) during and after the Manhattan Project. He came to Oak Ridge, Tennessee, in 1945 a ...

's Patent #2,736,696, on a conceptual light water reactor

The light-water reactor (LWR) is a type of thermal-neutron reactor that uses normal water, as opposed to heavy water, as both its coolant and neutron moderator; furthermore a solid form of fissile elements is used as fuel. Thermal-neutron react ...

(LWR) that would later become the United States' primary reactor for naval propulsion

Marine propulsion is the mechanism or system used to generate thrust to move a watercraft through water. While paddles and sails are still used on some smaller boats, most modern ships are propelled by mechanical systems consisting of an electri ...

and later take up the greatest share of the commercial fission-electric landscape.

The United Kingdom, Canada, and the USSR proceeded to research and develop nuclear energy over the course of the late 1940s and early 1950s.

The first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction

In nuclear physics, a nuclear chain reaction occurs when one single nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more subsequent nuclear reactions, thus leading to the possibility of a self-propagating series or "positive feedback loop" of thes ...

in Europe was achieved on 25 December 1946 by the F-1 (from "First Physical Reactor"), a research reactor

Research reactors are nuclear fission-based nuclear reactors that serve primarily as a neutron source. They are also called non-power reactors, in contrast to power reactors that are used for electricity production, heat generation, or maritim ...

operated by the Kurchatov Institute

The Kurchatov Institute (, National Research Centre "Kurchatov Institute") is Russia's leading research and development institution in the field of nuclear power, nuclear energy. It is named after Igor Kurchatov and is located at 1 Kurchatov Sq ...

in Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

, USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

.

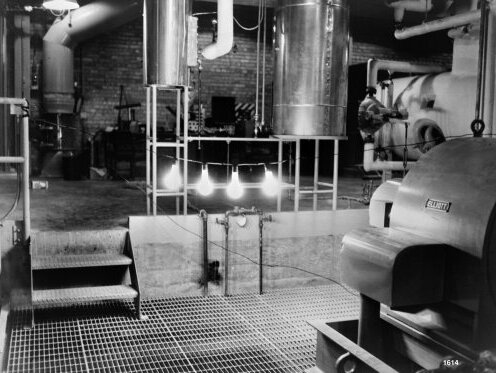

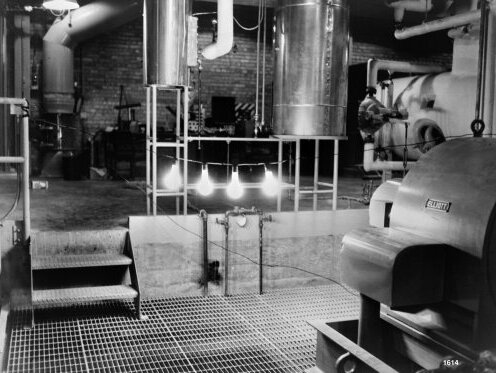

Electricity was generated for the first time by a nuclear reactor on 20 December 1951, at the EBR-I

Experimental Breeder Reactor I (EBR-I) is a decommissioned research reactor and U.S. National Historic Landmark located in the desert about southeast of Arco, Idaho. It was the world's first breeder reactor. At 1:50 p.m. on December 20, 1 ...

experimental station near Arco, Idaho

Arco is a city in Butte County, Idaho, United States. The population was 879 as of the 2020 United States census, down from 995 at the 2010 census. Arco is the county seat and largest city in Butte County.

History

Arco was named as early ...

, which initially produced about 100 kW.

In 1953, American President Dwight Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

gave his "Atoms for Peace

"Atoms for Peace" was the title of a speech delivered by U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower to the UN General Assembly in New York City on December 8, 1953.

The United States then launched an "Atoms for Peace" program that supplied equipment ...

" speech at the United Nations, emphasizing the need to develop "peaceful" uses of nuclear power quickly. This was followed by the Atomic Energy Act of 1954

The Atomic Energy Act of 1954, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2011–2021, 2022-2286i, 2296a-2297h-13, is a United States federal law that covers for the development, regulation, and disposal of nuclear materials and facilities in the United States.

It was an ...

which allowed rapid declassification of U.S. reactor technology and encouraged development by the private sector.

Early years

U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest displacement, at 4.5 million tons in 2021. It has the world's largest aircraft ...

, with the S1W reactor

The S1W reactor was the first prototype naval reactor used by the United States Navy to prove that the technology could be used for electricity generation and propulsion on submarines.

The designation of "S1W" stands for

* S = Submarine platfor ...

for the purpose of propelling submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

s and aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering carrier-based aircraft, shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the ...

s. The first nuclear-powered submarine, , was put to sea in January 1954. The S1W reactor was a Pressurized Water Reactor

A pressurized water reactor (PWR) is a type of light-water nuclear reactor. PWRs constitute the large majority of the world's nuclear power plants (with notable exceptions being the UK, Japan, India and Canada).

In a PWR, water is used both as ...

. This design was chosen because it was simpler, more compact, and easier to operate compared to alternative designs, thus more suitable to be used in submarines. This decision would result in the PWR being the reactor of choice also for power generation, thus having a lasting impact on the civilian electricity market in the years to come.

The United States Navy Nuclear Propulsion

The United States Navy Nuclear Propulsion community consists of Naval Officers and Enlisted members who are specially trained to run and maintain the nuclear reactors that power the submarines and aircraft carriers of the United States Navy. O ...

design and operation community, under Rickover's style

On 27 June 1954, the Obninsk Nuclear Power Plant

Obninsk Nuclear Power Plant (; ) was built in the " Science City" of Obninsk,USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

became the world's first nuclear power plant to generate electricity for a power grid

''Power Grid'' is the English-language version of the second edition of the multiplayer German-style board game ''Funkenschlag'', designed by Friedemann Friese and first released in 2004. ''Power Grid'' was released by Rio Grande Games.

I ...

, producing around 5 megawatts of electric power.

The world's first commercial nuclear power station, Calder Hall

Calder Hall Nuclear Power Station is a former Magnox nuclear power station at Sellafield in Cumbria in North West England. Calder Hall was the first full-scale nuclear power station to enter operation in the West, and was the sister plant to the ...

at Windscale, England was connected to the national power grid on 27 August 1956. In common with a number of other generation I reactor

A generation II reactor is a design classification for a nuclear reactor, and refers to the class of commercial reactors built until the end of the 1990s. Prototypical and older versions of PWR, CANDU, BWR, AGR, RBMK and VVER are among them. ...

s, the plant had the dual purpose of producing electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter possessing an electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described by Maxwel ...

and plutonium-239

Plutonium-239 ( or Pu-239) is an isotope of plutonium. Plutonium-239 is the primary fissile isotope used for the production of nuclear weapons, although uranium-235 is also used for that purpose. Plutonium-239 is also one of the three main iso ...

, the latter for the nascent nuclear weapons program in Britain. It had an initial capacity of 50 MW per reactor (200 MW total), it was the first of a fleet of dual-purpose MAGNOX

Magnox is a type of nuclear power / production reactor that was designed to run on natural uranium with graphite as the moderator and carbon dioxide gas as the heat exchange coolant. It belongs to the wider class of gas-cooled reactors. The ...

reactors.

The U.S. Army Nuclear Power Program

The Army Nuclear Power Program (ANPP) was a program of the United States Army to develop small pressurized water and boiling water nuclear power reactors to generate electrical and space-heating energy primarily at remote, relatively inaccessib ...

formally commenced in 1954. Under its management, the 2 megawatt SM-1

SM-1 (Stationary, Medium-size reactor, prototype #1) was a 2-megawatt nuclear reactor developed by the American Locomotive Company (ALCO) and the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) as part of the US Army Nuclear Power Program (ANPP) ...

, at Fort Belvoir

Fort Belvoir ( ) is a United States Army installation and a census-designated place (CDP) in Fairfax County, Virginia, United States. It was developed on the site of the former Belvoir (plantation), Belvoir plantation, seat of the prominent Lord ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

, was the first in the United States to supply electricity in an industrial capacity to the commercial grid ( VEPCO), in April 1957.

The first commercial nuclear station to become operational in the United States was the 60 MW Shippingport Reactor

The Shippingport Atomic Power Station was (according to the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission) the world's first full-scale atomic electric power plant devoted exclusively to peacetime uses.Though Obninsk Nuclear Power Plant was connected to the ...

(Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

), in December 1957.

Originating from a cancelled nuclear-powered

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced b ...

aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering carrier-based aircraft, shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the ...

contract, the plant used a PWR reactor design. Its early adoption, technological lock-in, and familiarity among retired naval personnel, established the PWR as the predominant civilian reactor design, that it still retains today in the United States.

In 1957 EURATOM was launched alongside the European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organisation created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisbo ...

(the latter is now the European Union). The same year also saw the launch of the International Atomic Energy Agency

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is an intergovernmental organization that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear technology, nuclear energy and to inhibit its use for any military purpose, including nuclear weapons. It was ...

(IAEA).

The first major accident at a nuclear reactor occurred at the 3 MW SL-1

Stationary Low-Power Reactor Number One, also known as SL-1, initially the Argonne Low Power Reactor (ALPR), was a United States Army experimental nuclear reactor in the Western United States, western United States at the Idaho National Laborato ...

, a U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of the United Stat ...

experimental nuclear power reactor at the National Reactor Testing Station, Idaho National Laboratory

Idaho National Laboratory (INL) is one of the national laboratories of the United States Department of Energy and is managed by the Battelle Energy Alliance. Historically, the lab has been involved with nuclear research, although the labora ...

. It was derived from the Borax Boiling water reactor (BWR) design and it first achieved operational criticality and connection to the grid in 1958.

For reasons unknown, in 1961 a technician removed a control rod about 22 inches farther than the prescribed 4 inches. This resulted in a steam explosion

A steam explosion is an explosion caused by violent boiling or flashing of water or ice into steam, occurring when water or ice is either superheated, rapidly heated by fine hot debris produced within it, or heated by the interaction of molten ...

which killed the three crew members and caused a meltdown.IDO-19313: Additional Analysis of the SL-1 Excursion

Final Report of Progress July through October 1962'', 21 November 1962, Flight Propulsion Laboratory Department, General Electric Company, Idaho Falls, Idaho, U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, Division of Technical Information. The event was eventually rated at 4 on the seven-level INES scale. On 16 September 1967, the Pathfinder Nuclear Station near Sioux Falls, South Dakota, open for about a year, suffered an accident which caused the one year old plant to be retired permanently when an operator opened a valve too fast. Another serious accident happened in 1968, when one of the two liquid-metal-cooled reactors on board the underwent a

fuel element failure

A fuel element failure is a rupture in a nuclear reactor's fuel cladding that allows the nuclear fuel or fission products, either in the form of dissolved radioisotopes or hot particles, to enter the reactor coolant or storage water.

The ' ...

, with the emission of gaseous fission product

Nuclear fission products are the atomic fragments left after a large atomic nucleus undergoes nuclear fission. Typically, a large nucleus like that of uranium fissions by splitting into two smaller nuclei, along with a few neutrons, the releas ...

s into the surrounding air. This resulted in 9 crew fatalities and 83 injuries.

Development and early opposition to nuclear power

gigawatt

The watt (symbol: W) is the unit of power or radiant flux in the International System of Units (SI), equal to 1 joule per second or 1 kg⋅m2⋅s−3. It is used to quantify the rate of energy transfer. The watt is named in honor ...

(GW) in 1960 to 100 GW in the late 1970s, and 300 GW in the late 1980s. Since the late 1980s worldwide capacity has risen much more slowly, reaching 366 GW in 2005. Between around 1970 and 1990, more than 50 GW of capacity was under construction (peaking at over 150 GW in the late 1970s and early 1980s)—in 2005, around 25 GW of new capacity was planned. More than two-thirds of all nuclear plants ordered after January 1970 were eventually cancelled. A total of 63 nuclear units were canceled in the United States between 1975 and 1980.

In 1972 Alvin Weinberg, co-inventor of the light water reactor design (the most common nuclear reactors today) was fired from his job at Oak Ridge National Laboratory

Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) is a federally funded research and development centers, federally funded research and development center in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, United States. Founded in 1943, the laboratory is sponsored by the United Sta ...

by the Nixon administration

Richard Nixon's tenure as the 37th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1969, and ended when he resigned on August 9, 1974, in the face of almost certain impeachment and removal from office, the ...

, "at least in part" over his raising of concerns about the safety and wisdom of ever larger scaling-up of his design, especially above a power rating of ~500 MWe, as in a loss of coolant accident

A loss-of-coolant accident (LOCA) is a mode of failure for a nuclear reactor; if not managed effectively, the results of a LOCA could result in reactor core damage. Each nuclear plant's emergency core cooling system (ECCS) exists specifically to ...

scenario, the decay heat

Decay heat is the heat released as a result of radioactive decay. This heat is produced as an effect of radiation on materials: the energy of the alpha particle, alpha, Beta particle, beta or gamma radiation is converted into the thermal movement ...

generated from such large compact solid-fuel cores was thought to be beyond the capabilities of passive/natural convection

Convection is single or Multiphase flow, multiphase fluid flow that occurs Spontaneous process, spontaneously through the combined effects of material property heterogeneity and body forces on a fluid, most commonly density and gravity (see buoy ...

cooling to prevent a rapid fuel rod melt-down and resulting in then, potential far reaching fission product

Nuclear fission products are the atomic fragments left after a large atomic nucleus undergoes nuclear fission. Typically, a large nucleus like that of uranium fissions by splitting into two smaller nuclei, along with a few neutrons, the releas ...

pluming. While considering the LWR, well suited at sea for the submarine and naval fleet, Weinberg did not show complete support for its use by utilities on land at the power output that they were interested in for supply scale reasons, and would request for a greater share of AEC research funding to evolve his team's demonstrated, Molten-Salt Reactor Experiment

The Molten-Salt Reactor Experiment (MSRE) was an experimental molten-salt reactor research reactor at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. This technology was researched through the 1960s, the reactor was constructed ...

, a design with greater inherent safety in this scenario and with that an envisioned greater economic growth potential in the market of large-scale civilian electricity generation.

Similar to the earlier BORAX reactor safety experiments, conducted by Argonne National Laboratory

Argonne National Laboratory is a Federally funded research and development centers, federally funded research and development center in Lemont, Illinois, Lemont, Illinois, United States. Founded in 1946, the laboratory is owned by the United Sta ...

, in 1976 Idaho National Laboratory

Idaho National Laboratory (INL) is one of the national laboratories of the United States Department of Energy and is managed by the Battelle Energy Alliance. Historically, the lab has been involved with nuclear research, although the labora ...

began a test program focused on LWR reactors under various accident scenarios, with the aim of understanding the event progression and mitigating steps necessary to respond to a failure of one or more of the disparate systems, with much of the redundant back-up safety equipment and nuclear regulations drawing from these series of destructive testing

In destructive testing (or destructive physical analysis, DPA) tests are carried out to the specimen's failure, in order to understand a specimen's performance or material behavior under different loads. These tests are generally much easier to ca ...

investigations.

During the 1970s and 1980s rising economic costs (related to extended construction times largely due to regulatory changes and pressure-group litigation) and falling fossil fuel prices made nuclear power plants then under construction less attractive. In the 1980s in the U.S. and 1990s in Europe, the flat electric grid growth and electricity liberalization

Energy liberalisation refers to the liberalisation of energy markets, with specific reference to electricity generation markets, by bringing greater competition into electricity and gas markets in the interest of creating more competitive marke ...

also made the addition of large new baseload

The base load (also baseload) is the minimum level of demand on an electrical grid over a span of time, for example, one week. This demand can be met by unvarying power plants or dispatchable generation, depending on which approach has the best mi ...

energy generators economically unattractive.

1973 oil crisis

In October 1973, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) announced that it was implementing a total oil embargo against countries that had supported Israel at any point during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, which began after Eg ...

had a significant effect on countries, such as France and Japan, which had relied more heavily on oil for electric generation (39% and 73% respectively) to invest in nuclear power.

The French plan, known as the Messmer plan, was for the complete independence from oil, with an envisaged construction of 80 reactors by 1985 and 170 by 2000.Les physiciens dans le mouvement antinucléaire : entre science, expertise et politiqueCahiers d'histoire, published 2007, accessed 11 April 2011 France would construct 25 fission-electric stations, installing 56 mostly PWR design reactors over the next 15 years, though foregoing the 100 reactors initially charted in 1973, for the 1990s. In 2019, 71% of French electricity was generated by 58 reactors, the highest percentage by any nation in the world. Some local opposition to nuclear power emerged in the U.S. in the early 1960s, beginning with the proposed

Bodega Bay

Bodega Bay () is a shallow, rocky inlet of the Pacific Ocean on the coast of northern California in the United States. It is approximately across and is located approximately northwest of San Francisco and west of Santa Rosa, California, S ...

station in California, in 1958, which produced conflict with local citizens and by 1964 the concept was ultimately abandoned. In the late 1960s some members of the scientific community began to express pointed concerns. These anti-nuclear

The Anti-nuclear war movement is a social movement that opposes various nuclear technologies. Some direct action groups, environmental movements, and professional organisations have identified themselves with the movement at the local, n ...

concerns related to nuclear accidents

A nuclear and radiation accident is defined by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) as "an event that has led to significant consequences to people, the environment or the facility." Examples include lethal effects to individuals, la ...

, nuclear proliferation

Nuclear proliferation is the spread of nuclear weapons to additional countries, particularly those not recognized as List of states with nuclear weapons, nuclear-weapon states by the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, commonl ...

, nuclear terrorism

Nuclear terrorism is the use of a nuclear weapon or radiological weapon as an act of terrorism. There are many possible terror incidents, ranging in feasibility and scope. These include the sabotage of a nuclear facility, the intentional irrad ...

and radioactive waste disposal Radioactive waste disposal may refer to:

*High-level radioactive waste management

* Low-level waste disposal

*Ocean disposal of radioactive waste

** Ocean floor disposal

* Deep borehole disposal

*Deep geological repository

A deep geological repos ...

. Brian MartinOpposing nuclear power: past and present

''Social Alternatives'', Vol. 26, No. 2, Second Quarter 2007, pp. 43–47. In the early 1970s, there were large protests about a proposed nuclear power plant in

Wyhl

Wyhl, officially Wyhl am Kaiserstuhl (; ), is a municipality in the district of Emmendingen in Baden-Württemberg in southwestern Germany.

It is known in the 1970s for its role in the anti-nuclear movement. Wyhl was first mentioned in 1971 as a ...

, Germany, and the project was cancelled in 1975. The anti-nuclear success at Wyhl inspired opposition to nuclear power in other parts of Europe and North America.Stephen Mills and Roger Williams (1986)Public Acceptance of New Technologies

Routledge, pp. 375–376.Robert Gottlieb (2005)

Forcing the Spring: The Transformation of the American Environmental Movement

Revised Edition, Island Press, p. 237. By the mid-1970s, anti-nuclear activism had gained a wider appeal and influence, and nuclear power began to become an issue of major public protest.Walker, J. Samuel (2004).

Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective

' (Berkeley: University of California Press), pp. 10–11. In some countries, the nuclear power conflict "reached an intensity unprecedented in the history of technology controversies". In May 1979, an estimated 70,000 people, including then governor of California

Jerry Brown

Edmund Gerald Brown Jr. (born April 7, 1938) is an American lawyer, author, and politician who served as the 34th and 39th governor of California from 1975 to 1983 and 2011 to 2019. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic P ...

, attended a march against nuclear power in Washington, D.C. Anti-nuclear power groups emerged in every country that had a nuclear power programme.

Globally during the 1980s one new nuclear reactor started up every 17 days on average.

Regulations, pricing and accidents

In the early 1970s, the increased public hostility to nuclear power in the United States lead theUnited States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by the U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President Harry ...

and later the Nuclear Regulatory Commission

The United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) is an independent agency of the United States government tasked with protecting public health and safety related to nuclear energy. Established by the Energy Reorganization Act of 1974, the ...

to lengthen the license procurement process, tighten engineering regulations and increase the requirements for safety equipment.Costs of Nuclear Power Plants – What Went Wrong?/ref> Together with relatively minor percentage increases in the total quantity of steel, piping, cabling and concrete per unit of installed

nameplate capacity

Nameplate capacity, also known as the rated capacity, nominal capacity, installed capacity, maximum effect or gross capacity,public hearing

In law, a hearing is the formal examination of a case (civil or criminal) before a judge. It is a proceeding before a court or other decision-making body or officer, such as a government agency or a legislative committee.

Description

A hearing ...

-response cycle for the granting of construction licenses, had the effect of what was once an initial 16 months for project initiation to the pouring of first concrete in 1967, escalating to 32 months in 1972 and finally 54 months in 1980, which ultimately, quadrupled the price of power reactors.

Utility proposals in the U.S for nuclear generating stations, peaked at 52 in 1974, fell to 12 in 1976 and have never recovered,World's Atom Energy Lags In Meeting Needs for Power, ''NYtimes'' 1979/ref> in large part due to the pressure-group litigation strategy, of launching lawsuits against each proposed U.S construction proposal, keeping private utilities tied up in court for years, one of which having reached the supreme court in 1978 (see

Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Corp. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc.

''Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Corp. v. Natural Resources Defense Council'', 435 U.S. 519 (1978), is a case in which the United States Supreme Court held that a court cannot impose rulemaking procedures on a federal government agency. The federal ...

With permission to build a nuclear station in the U.S. eventually taking longer than in any other industrial country, the spectre facing utilities of having to pay interest on large construction loans while the anti-nuclear movement used the legal system to produce delays, increasingly made the viability of financing construction, less certain. As the 1970s came to a close, it became clear that nuclear power would not grow nearly as dramatically as once believed.

Over 120 reactor proposals in the United States were ultimately cancelled and the construction of new reactors ground to a halt. A cover story in the 11 February 1985, issue of ''Forbes

''Forbes'' () is an American business magazine founded by B. C. Forbes in 1917. It has been owned by the Hong Kong–based investment group Integrated Whale Media Investments since 2014. Its chairman and editor-in-chief is Steve Forbes. The co ...

'' magazine commented on the overall failure of the U.S. nuclear power program, saying it "ranks as the largest managerial disaster in business history".

According to some commentators, the 1979 accident at Three Mile Island played a major part in the reduction in the number of new plant constructions in many other countries. According to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission

The United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) is an independent agency of the United States government tasked with protecting public health and safety related to nuclear energy. Established by the Energy Reorganization Act of 1974, the ...

(NRC), the Three Mile Island accident was the most serious accident in "U.S. commercial nuclear power plant operating history, even though it led to no deaths or injuries to plant workers or members of the nearby community." The regulatory uncertainty and delays eventually resulted in an escalation of construction related debt that led to the bankruptcy of Seabrook's major utility owner, Public Service Company of New Hampshire. At the time, it was the fourth largest bankruptcy in United States corporate history.

Among American engineers, the cost increases from implementing the regulatory changes that resulted from the TMI accident were, when eventually finalized, only a few percent of total construction costs for new reactors, primarily relating to the prevention of safety systems from being turned off. With the most significant engineering result of the TMI accident, the recognition that better operator training was needed and that the existing emergency core cooling system

The three primary objectives of nuclear reactor safety systems as defined by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission are to shut down the reactor, maintain it in a shutdown condition and prevent the release of radioactive material.

Reactor protec ...

of PWRs worked better in a real-world emergency than members of the anti-nuclear movement had routinely claimed.

The already slowing rate of new construction along with the shutdown in the 1980s of two existing demonstration nuclear power stations in the Tennessee Valley

The Tennessee Valley is the drainage basin of the Tennessee River and is largely within the U.S. state of Tennessee. It stretches from southwest Kentucky to north Alabama and from northeast Mississippi to the mountains of Virginia and North C ...

, United States, when they could not economically meet the NRC's new tightened standards, shifted electricity generation to coal-fired power plants. In 1977, following the first oil shock, U.S. President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

made a speech calling the energy crisis the "moral equivalent of war

A moral (from Latin ''morālis'') is a message that is conveyed or a lesson to be learned from a story or event. The moral may be left to the hearer, reader, or viewer to determine for themselves, or may be explicitly encapsulated in a maxim. ...

" and prominently supporting nuclear power. However, nuclear power could not compete with cheap oil and gas, particularly after public opposition and regulatory hurdles made new nuclear prohibitively expensive.

In 1982, amongst a backdrop of ongoing protests directed at the construction of the first commercial scale breeder reactor

A breeder reactor is a nuclear reactor that generates more fissile material than it consumes. These reactors can be fueled with more-commonly available isotopes of uranium and thorium, such as uranium-238 and thorium-232, as opposed to the ...

in France, a later member of the Swiss Green Party

The Green Party of Switzerland (; ; ; ) is a green political party in Switzerland. It is the fifth-largest party in the National Council of Switzerland and the largest party that is not represented on the Federal Council.

History

The first G ...

fired five RPG-7

The RPG-7 is a portable, reusable, unguided, shoulder-launched, anti-tank, rocket launcher. The RPG-7 and its predecessor, the RPG-2, were designed by the Soviet Union, and are now manufactured by the Russian company Bazalt. The weapon has t ...

rocket-propelled grenade

A rocket-propelled grenade (RPG), also known colloquially as a rocket launcher, is a Shoulder-fired missile, shoulder-fired anti-tank weapon that launches rockets equipped with a Shaped charge, shaped-charge explosive warhead. Most RPGs can ...

s at the still under construction containment building

A containment building is a reinforced steel, concrete or lead structure enclosing a nuclear reactor. It is designed, in any emergency, to contain the escape of radioactive steam or gas to a maximum pressure in the range of . The containment is ...

of the Superphenix reactor. Two grenades hit and caused minor damage to the reinforced concrete outer shell. It was the first time protests reached such heights. After examination of the superficial damage, the prototype fast breeder reactor started and operated for over a decade.

Chernobyl disaster

The Chernobyl disaster occurred on Saturday 26 April 1986, at the No. 4 reactor in theChernobyl Nuclear Power Plant

The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant (ChNPP) is a nuclear power plant undergoing decommissioning. ChNPP is located near the abandoned city of Pripyat in northern Ukraine, northwest of the city of Chernobyl, from the Belarus–Ukraine border, a ...

, near the city of Pripyat

Pripyat, also known as Prypiat, is an abandoned industrial city in Kyiv Oblast, Ukraine, located near the border with Belarus. Named after the nearby river, Pripyat (river), Pripyat, it was founded on 4 February 1970 as the ninth ''atomgrad'' ...

in the north of the Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. ...

. It is considered as the worst nuclear disaster in history both in terms of cost and casualties. The initial emergency response, together with later decontamination

Decontamination (sometimes abbreviated as decon, dcon, or decontam) is the process of removing contaminants on an object or area, including chemicals, micro-organisms, and/or radioactive substances. This may be achieved by chemical reaction, dis ...

of the environment, ultimately involved more than 500,000 personnel

Employment is a relationship between two parties regulating the provision of paid labour services. Usually based on a contract, one party, the employer, which might be a corporation, a not-for-profit organization, a co-operative, or any othe ...

and cost an estimated 18 billion Soviet ruble

The ruble or rouble (; rus, рубль, r=rubl', p=rublʲ) was the currency of the Soviet Union. It was introduced in 1922 and replaced the Russian ruble#Imperial ruble (1704-1922), Imperial Russian ruble. One ruble was divided into 100 kopecks ...

s—roughly US$68 billion in 2019, adjusted for inflation. (see 1996 interview with Mikhail Gorbachev)

According to some commentators, the Chernobyl disaster played a major part in the reduction in the number of new plant constructions in many other countries.

Unlike the Three Mile Island accident the much more serious Chernobyl accident did not increase regulations or engineering changes affecting Western reactors; because the RBMK

The RBMK (, РБМК; ''reaktor bolshoy moshchnosti kanalnyy'', "high-power channel-type reactor") is a class of graphite moderated reactor, graphite-moderated nuclear reactor, nuclear power reactor designed and built by the Soviet Union. It is so ...

design, which lacks safety features such as "robust" containment building

A containment building is a reinforced steel, concrete or lead structure enclosing a nuclear reactor. It is designed, in any emergency, to contain the escape of radioactive steam or gas to a maximum pressure in the range of . The containment is ...

s, was only used in the Soviet Union. Over 10 RBMK reactors are still in use today. However, changes were made in both the RBMK reactors themselves (use of a safer enrichment of uranium) and in the control system (preventing safety systems being disabled), amongst other things, to reduce the possibility of a similar accident.

Russia now largely relies upon, builds and exports a variant of the PWR, the VVER

The water-water energetic reactor (WWER), or VVER (from ) is a series of pressurized water reactor designs originally developed in the Soviet Union, and now Russia, by OKB Gidropress. The idea of such a reactor was proposed at the Kurchatov Instit ...

, with over 20 in use today.

An international organization to promote safety awareness and the professional development of operators in nuclear facilities, the World Association of Nuclear Operators

The World Association of Nuclear Operators (WANO) is a nonprofit, international organisation with a mission to maximize the safety and reliability of the world’s commercial nuclear power plants. The organization’s members are mainly owners ...

(WANO), was created as a direct outcome of the 1986 Chernobyl accident. The organization was created with the intent to share and grow the adoption of nuclear safety culture, technology and community, where before there was an atmosphere of Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

secrecy.

Numerous countries, including Austria (1978), Sweden (1980) and Italy (1987) (influenced by Chernobyl) have voted in referendums to oppose or phase out nuclear power.

Nuclear renaissance

In the early 2000s, the nuclear industry was expecting a nuclear renaissance, an increase in the construction of new reactors, due to concerns about carbon dioxide emissions. However, in 2009, Petteri Tiippana, the director of nuclear power plant division in the Finnish

In the early 2000s, the nuclear industry was expecting a nuclear renaissance, an increase in the construction of new reactors, due to concerns about carbon dioxide emissions. However, in 2009, Petteri Tiippana, the director of nuclear power plant division in the Finnish Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority

The Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority (, ), often abbreviated as STUK, is a government agency tasked with nuclear safety and radiation monitoring in Finland. The agency is a division of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health; when foun ...

, told the BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

that it was difficult to deliver a Generation III reactor

Generation III reactors, or Gen III reactors, are a class of nuclear reactors designed to succeed Generation II reactors, incorporating evolutionary improvements in design. These include improved fuel technology, higher thermal efficiency, signi ...

project on schedule because builders were not used to working to the exacting standards required on nuclear construction sites, since so few new reactors had been built in recent years.

The Olkiluoto 3

The Olkiluoto Nuclear Power Plant (, ) is one of Finland's two nuclear power plants, the other being the two-unit Loviisa Nuclear Power Plant. The plant is owned and operated by Teollisuuden Voima (TVO), and is located on Olkiluoto Island, on th ...

was the first EPR, a modernized PWR design, to start construction. Problems with workmanship and supervision have created costly delays. The reactor is estimated to cost three times the initial estimate and will be delivered over 10 years behind schedule.

In 2018 the MIT

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Established in 1861, MIT has played a significant role in the development of many areas of modern technology and sc ...

Energy Initiative study on the future of nuclear energy concluded that, together with the strong suggestion that government should financially support development and demonstration of new Generation IV nuclear technologies, for a worldwide renaissance to commence, a global standardization of regulations needs to take place, with a move towards serial manufacturing of standardized units akin to the other complex engineering field of aircraft and aviation. At present it is common for each country to demand bespoke

''Bespoke'' () describes anything commissioned to a particular specification, altered or tailored to the customs, tastes, or usage of an individual purchaser. In contemporary usage, ''bespoke'' has become a general marketing and branding concep ...

changes to the design to satisfy varying national regulatory bodies, often to the benefit of domestic engineering supply firms. The report goes on to note that the most cost-effective projects have been built with multiple (up to six) reactors per site using a standardized design, with the same component suppliers and construction crews working on each unit, in a continuous work flow.

Fukushima Daiichi disaster

Following the Tōhoku earthquake on 11 March 2011, one of the largest earthquakes ever recorded, and a subsequenttsunami

A tsunami ( ; from , ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and underwater explosions (including detonations, ...

off the coast of Japan, the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant

The is a disabled nuclear power plant located on a site in the towns of Ōkuma, Fukushima, Ōkuma and Futaba, Fukushima, Futaba in Fukushima Prefecture, Japan. The plant Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, suffered major damage from the 201 ...

suffered three core meltdowns due to failure of the emergency cooling system for lack of electricity supply. This resulted in the most serious nuclear accident since the Chernobyl disaster.

The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident prompted a re-examination of nuclear safety

Nuclear safety is defined by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) as "The achievement of proper operating conditions, prevention of accidents or mitigation of accident consequences, resulting in protection of workers, the public and the ...

and nuclear energy policy

Nuclear energy policy is a national and international policy concerning some or all aspects of nuclear energy and the nuclear fuel cycle, such as uranium mining, ore concentration, conversion, enrichment for nuclear fuel, generating electric ...

in many countries and raised questions among some commentators over the future of the renaissance.Analysis: Nuclear renaissance could fizzle after Japan quakeReuters, published 2011-03-14, accessed 14 March 2011 Germany approved plans to close all its reactors by 2022 (Following the energy crisis caused by the

Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 24 February 2022, , starting the largest and deadliest war in Europe since World War II, in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, conflict between the two countries which began in 2014. The fighting has caused hundreds of thou ...

, Germany now plans to keep reactors running until April 2023). Italian nuclear energy plans ended when Italy banned the generation, but not consumption, of nuclear electricity in a June 2011 referendum.

China, Switzerland, Israel, Malaysia, Thailand, United Kingdom, and the Philippines reviewed their nuclear power programs.Israel Prime Minister Netanyahu: Japan situation has "caused me to reconsider" nuclear powerPiers Morgan on CNN, published 2011-03-17, accessed 17 March 2011

xinhuanet.com, published 2011-03-18, accessed 17 March 2011 In 2011 the

International Energy Agency

The International Energy Agency (IEA) is a Paris-based autonomous intergovernmental organization, established in 1974, that provides policy recommendations, analysis and data on the global energy sector. The 31 member countries and 13 associatio ...

halved its prior estimate of new generating capacity to be built by 2035.

Nuclear power generation had the biggest ever fall year-on-year in 2012, with nuclear power plants globally producing 2,346 TWh of electricity, a drop of 7% from 2011.

This was caused primarily by the majority of Japanese reactors remaining offline that year and the permanent closure of eight reactors in Germany.

Post-Fukushima

The

The Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American not-for-profit organization, not-for-profit news agency headquartered in New York City.

Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association, and produces news reports that are dist ...

and Reuters

Reuters ( ) is a news agency owned by Thomson Reuters. It employs around 2,500 journalists and 600 photojournalists in about 200 locations worldwide writing in 16 languages. Reuters is one of the largest news agencies in the world.

The agency ...

reported in 2011 the suggestion that the safety and survival of the younger Onagawa Nuclear Power Plant

The is a nuclear power plant located on a 1,730,000 m2 (432 acres) site in Onagawa in the Oshika District and Ishinomaki city, Miyagi Prefecture, Japan. It is managed by the Tohoku Electric Power Company. It was the most quickly constructed ...

, the closest reactor facility to the epicenter

The epicenter (), epicentre, or epicentrum in seismology is the point on the Earth's surface directly above a hypocenter or focus, the point where an earthquake or an underground explosion originates.

Determination

The primary purpose of a ...

and on the coast, demonstrate that it is possible for nuclear facilities to withstand the greatest natural disasters. The Onagawa plant was also said to show that nuclear power can retain public trust, with the surviving residents of the town of Onagawa taking refuge in the gymnasium of the nuclear facility following the destruction of their town.

In February 2012, the U.S. NRC approved the construction of 2 reactors at the Vogtle Electric Generating Plant

The Alvin W. Vogtle Electric Generating Plant, also known as Plant Vogtle ( ), is a four-unit nuclear power plant located in Burke County, near Waynesboro, Georgia, in the southeastern United States. With a power capacity of 4,536 megawatts, ...

, the first approval in 30 years.

In August 2015, following 4 years of near zero fission-electricity generation, Japan began restarting its nuclear reactors, after safety upgrades were completed, beginning with Sendai Nuclear Power Plant.

By 2015, the IAEA's outlook for nuclear energy had become more promising.

"Nuclear power is a critical element in limiting greenhouse gas emissions," the agency noted, and "the prospects for nuclear energy remain positive in the medium to long term despite a negative impact in some countries in the aftermath of the ukushima-Daiichiaccident...it is still the second-largest source worldwide of low-carbon electricity.

And the 72 reactors under construction at the start of last year were the most in 25 years."

, the global trend was for new nuclear power stations coming online to be balanced by the number of old plants being retired. Eight new grid connections were completed by China in 2015.

In 2016, the BN-800

The BN-800 reactor (Russian: реактор БН–800) is a sodium-cooled fast breeder reactor, built at the Beloyarsk Nuclear Power Station, in Zarechny, Sverdlovsk Oblast, Russia. The reactor is designed to generate 880 MW of electrical pow ...

sodium cooled fast reactor

A fast-neutron reactor (FNR) or fast-spectrum reactor or simply a fast reactor is a category of nuclear reactor in which the fission chain reaction is sustained by fast neutrons (carrying energies above 1 MeV, on average), as opposed to slow t ...

in Russia, began commercial electricity generation, while plans for a BN-1200 were initially conceived the future of the fast reactor program in Russia awaits the results from MBIR, an under construction multi-loop Generation research facility for testing the chemically more inert lead, lead-bismuth

Bismuth is a chemical element; it has symbol Bi and atomic number 83. It is a post-transition metal and one of the pnictogens, with chemical properties resembling its lighter group 15 siblings arsenic and antimony. Elemental bismuth occurs nat ...

and gas coolants, it will similarly run on recycled MOX

Mox or MOX may refer to:

People

* Jon Moxley (born 1985), American professional wrestler

* Mox McQuery (1861–1900), American baseball player

Technology

* Mac OS X, a computer operating system

* Microsoft Open XML, a file format

* Mixed ox ...

(mixed uranium and plutonium oxide) fuel. An on-site pyrochemical processing, closed fuel-cycle facility, is planned, to recycle the spent fuel/"waste" and reduce the necessity for a growth in uranium mining and exploration. In 2017 the manufacture program for the reactor commenced with the facility open to collaboration under the "International Project on Innovative Nuclear Reactors and Fuel Cycle", it has a construction schedule, that includes an operational start in 2020. As planned, it will be the world's most-powerful research reactor.

In 2015, the Japanese government committed to the aim of restarting its fleet of 40 reactors by 2030 after safety upgrades, and to finish the construction of the Generation III Ōma Nuclear Power Plant

The is a nuclear power facility under construction in Ōma, Aomori, Japan.

It will be operated by the Electric Power Development Company (J-Power).

The reactor would be unique for Japan in that it would be capable of using a 100% MOX fuel core, ...

.

This would mean that approximately 20% of electricity would come from nuclear power by 2030. As of 2018, some reactors have restarted commercial operation following inspections and upgrades with new regulations. While South Korea has a large nuclear power industry, the new government in 2017, influenced by a vocal anti-nuclear movement, committed to halting nuclear development after the completion of the facilities presently under construction.

The bankruptcy of Westinghouse in March 2017 due to US$9 billion of losses from the halting of construction at Virgil C. Summer Nuclear Generating Station

The Virgil C. Summer Nuclear Power Station occupies a site near Jenkinsville, South Carolina, in Fairfield County, South Carolina, approximately northwest of Columbia.

The plant has one Westinghouse 3-loop Pressurized Water Reactor, which h ...

, in the U.S. is considered an advantage for eastern companies, for the future export and design of nuclear fuel and reactors.

In 2016, the U.S. Energy Information Administration

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) is a principal agency of the U.S. Federal Statistical System responsible for collecting, analyzing, and disseminating energy information to promote sound policymaking, efficient markets, and pub ...

projected for its "base case" that world nuclear power generation would increase from 2,344 terawatt hour

A kilowatt-hour ( unit symbol: kW⋅h or kW h; commonly written as kWh) is a non-SI unit of energy equal to 3.6 megajoules (MJ) in SI units, which is the energy delivered by one kilowatt of power for one hour. Kilowatt-hours are a commo ...

s (TWh) in 2012 to 4,500 TWh in 2040. Most of the predicted increase was expected to be in Asia. As of 2018, there are over 150 nuclear reactors planned including 50 under construction. In January 2019, China had 45 reactors in operation, 13 under construction, and plans to build 43 more, which would make it the world's largest generator of nuclear electricity.

Current prospects

Zero-emission nuclear power is an important part of theclimate change mitigation

Climate change mitigation (or decarbonisation) is action to limit the greenhouse gases in the atmosphere that cause climate change. Climate change mitigation actions include energy conservation, conserving energy and Fossil fuel phase-out, repl ...

effort. Under IEA Sustainable Development Scenario by 2030 nuclear power and CCUS would have generated 3900 TWh globally while wind and solar 8100 TWh with the ambition to achieve net-zero emissions by 2070. In order to achieve this goal on average 15 GWe of nuclear power should have been added annually on average. As of 2019 over 60 GW in new nuclear power plants was in construction, mostly in China, Russia, Korea, India and UAE. Many countries in the world are considering Small Modular Reactors with one in Russia connected to the grid in 2020.

Countries with at least one nuclear power plant in planning phase include Argentina, Brazil, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Egypt, Finland, Hungary, India, Kazakhstan, Poland, Saudi Arabia and Uzbekistan.

The future of nuclear power varies greatly between countries, depending on government policies. Some countries, most notably, Germany, have adopted policies of nuclear power phase-out

A nuclear power phase-out is the discontinuation of usage of nuclear power for energy production. Often initiated because of Politics of nuclear power, concerns about nuclear power, phase-outs usually include shutting down nuclear power plants ...

. At the same time, some Asian countries, such as China and India, have committed to rapid expansion of nuclear power. In other countries, such as the United Kingdom and the United States, nuclear power is planned to be part of the energy mix

The energy mix is a group of different primary energy, primary energy sources from which secondary energy for direct use - such as electricity - is produced. Energy mix refers to all direct uses of energy, such as transportation and housing, and ...

together with renewable energy, increasing demand for STEM jobs in the nuclear sector.

Nuclear energy may be one solution to providing clean power while also reversing the impact fossil fuels have had on our climate. These plants would capture carbon dioxide and create a clean energy source with zero emissions, making a carbon-negative process. Scientists propose that 1.8 million lives have already been saved by replacing fossil fuel sources with nuclear power.

the cost of extending plant lifetimes is competitive with other electricity generation technologies, including new solar and wind projects. In the United States, licenses of almost half of the operating nuclear reactors have been extended to 60 years.

The U.S. NRC and the U.S. Department of Energy have initiated research into light water reactor sustainability

The Light Water Reactor Sustainability Program is a U.S. government research and development program. It is directed by the United States Department of Energy and is aimed at performing research and compiling data necessary to qualify for licenses ...

which is hoped will lead to allowing extensions of reactor licenses beyond 60 years, provided that safety can be maintained, to increase energy security and preserve low-carbon generation sources. Research into nuclear reactors that can last 100 years, known as Centurion Reactors, is being conducted.Sherrell R. Greene, "Centurion Reactors – Achieving Commercial Power Reactors With 100+ Year Operating Lifetimes'", Oak Ridge National Laboratory, published in transactions of Winter 2009 American Nuclear Society National Meeting, November 2009, Washington, DC.

As of 2020, a number of US nuclear power plants were cleared by Nuclear Regulatory Commission for operations up to 80 years.

Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 24 February 2022, , starting the largest and deadliest war in Europe since World War II, in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, conflict between the two countries which began in 2014. The fighting has caused hundreds of thou ...

, the situation has changed. With the Versailles declaration

The Versailles declaration is a document issued on by leaders of the European Union (EU) in Versailles, France in response to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine that had begun two weeks earlier. Although informal, the document reaffirmed the EU ...

agreed in March 2022, the EU leaders of the 27 member states agreed to ''phase out the EU’s dependence on Russian fossil fuels'' as soon as possible.

The World Economic Forum

The World Economic Forum (WEF) is an international non-governmental organization, international advocacy non-governmental organization and think tank, based in Cologny, Canton of Geneva, Switzerland. It was founded on 24 January 1971 by German ...

has published energy policy changes, following the Russian Invasion.

Korea is planning to "increase renewables in electricity .. ndnuclear power to over 30%". Japan has decided to "restart nuclear power plants aligned with the 6th Strategic Energy Plan ...

Germany decided to postpone the shutdown of its three remaining nuclear power plants until April 2023.

See also

* Timeline of nuclear power *Timeline of nuclear weapons development