The history of magic extends from the earliest literate cultures, who relied on charms, divination and spells to interpret and influence the forces of nature. Even societies without written language left crafted artifacts,

cave art

In archaeology, cave paintings are a type of parietal art (which category also includes petroglyphs, or engravings), found on the wall or ceilings of caves. The term usually implies prehistoric art, prehistoric origin. These paintings were often c ...

and monuments that have been interpreted as having magical purpose. Magic and what would later be called

science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

were often practiced together, with the notable examples of

astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions ...

and

alchemy

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

, before the

Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of History of science, modern science during the early modern period, when developments in History of mathematics#Mathematics during the Scientific Revolution, mathemati ...

of the late European

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

moved to separate science from magic on the basis of repeatable observation. Despite this loss of prestige, the use of magic has continued both in its traditional role, and among modern occultists who seek to adapt it for a scientific world.

Ancient practitioners

Mesopotamia

Magic was invoked in many kinds of rituals and medical formulae, and to counteract evil omens. Defensive or legitimate magic in Mesopotamia (''asiputu'' or ''masmassutu'' in the Akkadian language) were incantations and ritual practices intended to alter specific realities. The ancient

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

ns believed that magic was the only viable defense against

demon

A demon is a malevolent supernatural entity. Historically, belief in demons, or stories about demons, occurs in folklore, mythology, religion, occultism, and literature; these beliefs are reflected in Media (communication), media including

f ...

s,

ghosts

In folklore, a ghost is the soul or Spirit (supernatural entity), spirit of a dead Human, person or non-human animal that is believed by some people to be able to appear to the living. In ghostlore, descriptions of ghosts vary widely, from a ...

, and evil sorcerers. To defend themselves against the spirits of those they had wronged, they would leave offerings known as ''kispu'' in the person's tomb in hope of appeasing them. If that failed, they also sometimes took a figurine of the deceased and buried it in the ground, demanding for the gods to eradicate the spirit, or force it to leave the person alone.

The ancient Mesopotamians also used magic intending to protect themselves from evil sorcerers who might place curses on them. Black magic as a category didn't exist in ancient Mesopotamia, and a person legitimately using magic to defend themselves against illegitimate magic would use exactly the same techniques. The only major difference was the fact that curses were enacted in secret; whereas a defense against sorcery was conducted in the open, in front of an audience if possible. One ritual to punish a sorcerer was known as

Maqlû

The Maqlû, “burning,” series is an Akkadian incantation text which concerns the performance of a rather lengthy anti-witchcraft, or ''kišpū'', ritual. In its mature form, probably composed in the early first millennium BC, it comprises eigh ...

, or "The Burning". The person viewed as being afflicted by witchcraft would create an effigy of the sorcerer and put it on trial at night. Then, once the nature of the sorcerer's crimes had been determined, the person would burn the effigy and thereby break the sorcerer's power over them.

The ancient Mesopotamians also performed magical rituals to purify themselves of sins committed unknowingly. One such ritual was known as the

Šurpu

The ancient Mesopotamian incantation series Šurpu begins ''enūma nēpešē ša šur-pu t'' 'eppušu'', “when you perform the rituals for (the series) ‘Burning,’” and was probably compiled in the middle Babylonian period, ca. 1350–105 ...

, or "Burning", in which the caster of the spell would transfer the guilt for all their misdeeds onto various objects such as a strip of dates, an onion, and a tuft of wool. The person would then burn the objects and thereby purify themself of all sins that they might have unknowingly committed. A whole genre of

love spells existed. Such spells were believed to cause a person to fall in love with another person, restore love which had faded, or cause a male sexual partner to be able to sustain an erection when he had previously been unable. Other spells were used to reconcile a man with his patron deity or to reconcile a wife with a husband who had been neglecting her.

The ancient Mesopotamians made no distinction between rational science and magic.

When a person became ill, doctors would prescribe both magical formulas to be recited as well as medicinal treatments.

Most magical rituals were intended to be performed by an ''

āšipu'', an expert in the magical arts.

The profession was generally passed down from generation to generation and was held in extremely high regard and often served as advisors to kings and great leaders. An āšipu probably served not only as a magician, but also as a physician, a priest, a scribe, and a scholar.

The Sumerian god

Enki

Enki ( ) is the Sumerian god of water, knowledge ('' gestú''), crafts (''gašam''), and creation (''nudimmud''), and one of the Anunnaki. He was later known as Ea () or Ae p. 324, note 27. in Akkadian (Assyrian-Babylonian) religion, and ...

, who was later syncretized with the

East Semitic

The East Semitic languages are one of three divisions of the Semitic languages. The East Semitic group is attested by three distinct languages, Akkadian, Eblaite and possibly Kishite, all of which have been long extinct. They were influenced ...

god Ea, was closely associated with magic and incantations; he was the patron god of the ''

bārȗ'' and the ''ašipū'' and was widely regarded as the ultimate source of all arcane knowledge. The ancient Mesopotamians also believed in

omen

An omen (also called ''portent'') is a phenomenon that is believed to foretell the future, often signifying the advent of change. It was commonly believed in ancient history, and still believed by some today, that omens bring divine messages ...

s, which could come when solicited or unsolicited. Regardless of how they came, omens were always taken with the utmost seriousness.

A common set of shared assumptions about the causes of evil and how to avert it are found in a form of early

protective magic

Apotropaic magic (From ) or protective magic is a type of Magic (paranormal), magic intended to turn away harm or evil influences, as in deflecting misfortune or averting the evil eye. Apotropaic observances may also be practiced out of supers ...

called incantation bowl or magic bowls. The bowls were produced in the Middle East, particularly in

Upper Mesopotamia

Upper Mesopotamia constitutes the Upland and lowland, uplands and great outwash plain of northwestern Iraq, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey, in the northern Middle East. Since the early Muslim conquests of the mid-7th century, the regio ...

and

Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

, what is now

Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

and

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, and fairly popular during the sixth to eighth centuries. The

bowl

A bowl is a typically round dish or container generally used for preparing, serving, storing, or consuming food. The interior of a bowl is characteristically shaped like a spherical cap, with the edges and the bottom, forming a seamless curve ...

s were buried face down and were meant to capture

demon

A demon is a malevolent supernatural entity. Historically, belief in demons, or stories about demons, occurs in folklore, mythology, religion, occultism, and literature; these beliefs are reflected in Media (communication), media including

f ...

s. They were commonly placed under the threshold, courtyards, in the corner of the homes of the recently deceased and in

cemeteries

A cemetery, burial ground, gravesite, graveyard, or a green space called a memorial park or memorial garden, is a place where the remains of many dead people are buried or otherwise entombed. The word ''cemetery'' (from Greek ) implies th ...

.

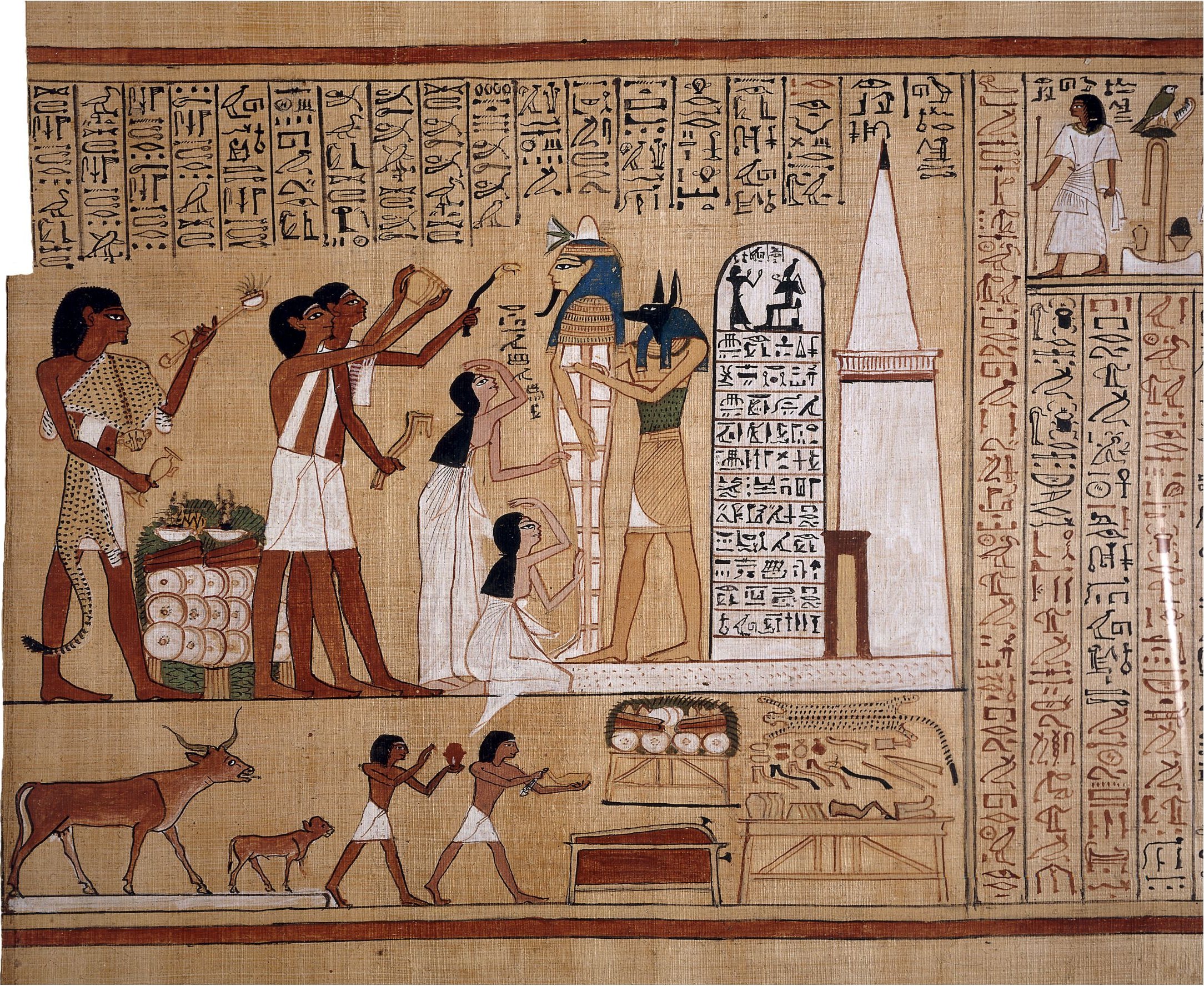

Egypt

In ancient Egypt (''Kemet'' in the Egyptian language), Magic (personified as the god

''heka'') was an integral part of religion and culture which is known to us through a substantial corpus of texts which are products of the Egyptian tradition.

While the category magic has been contentious for modern Egyptology, there is clear support for its applicability from ancient terminology.

[Ritner, R.K., Magic: An Overview in Redford, D.B., Oxford Encyclopedia Of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, 2001, p 321] The Coptic term ''hik'' is the descendant of the pharaonic term ''heka'', which, unlike its Coptic counterpart, had no connotation of impiety or illegality, and is attested from the Old Kingdom through to the Roman era.

''Heka'' was considered morally neutral and was applied to the practices and beliefs of both foreigners and Egyptians alike. The Instructions for Merikare informs us that ''heka'' was a beneficence gifted by the creator to humanity "... in order to be weapons to ward off the blow of events".

Magic was practiced by both the literate priestly hierarchy and by illiterate farmers and herdsmen, and the principle of ''heka'' underlay all ritual activity, both in the temples and in private settings.

The main principle of ''heka'' is centered on the power of words to bring things into being.

Karenga explains the pivotal power of words and their vital ontological role as the primary tool used by the creator to bring the manifest world into being. Because humans were understood to share a divine nature with the gods, ''snnw ntr'' (images of the god), the same power to use words creatively that the gods have is shared by humans.

The use of

amulets

An amulet, also known as a good luck charm or phylactery, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The word "amulet" comes from the Latin word , which Pliny's ''Natural History'' describes as "an object that protects a pers ...

, (''meket'') was widespread among both living and dead ancient Egyptians.

[Teeter, E., (2011), Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt, Cambridge University Press, p. 170] They were used for protection and as a means of "...reaffirming the fundamental fairness of the universe". The oldest amulets found are from the predynastic

Badarian Period, and they persisted through to Roman times.

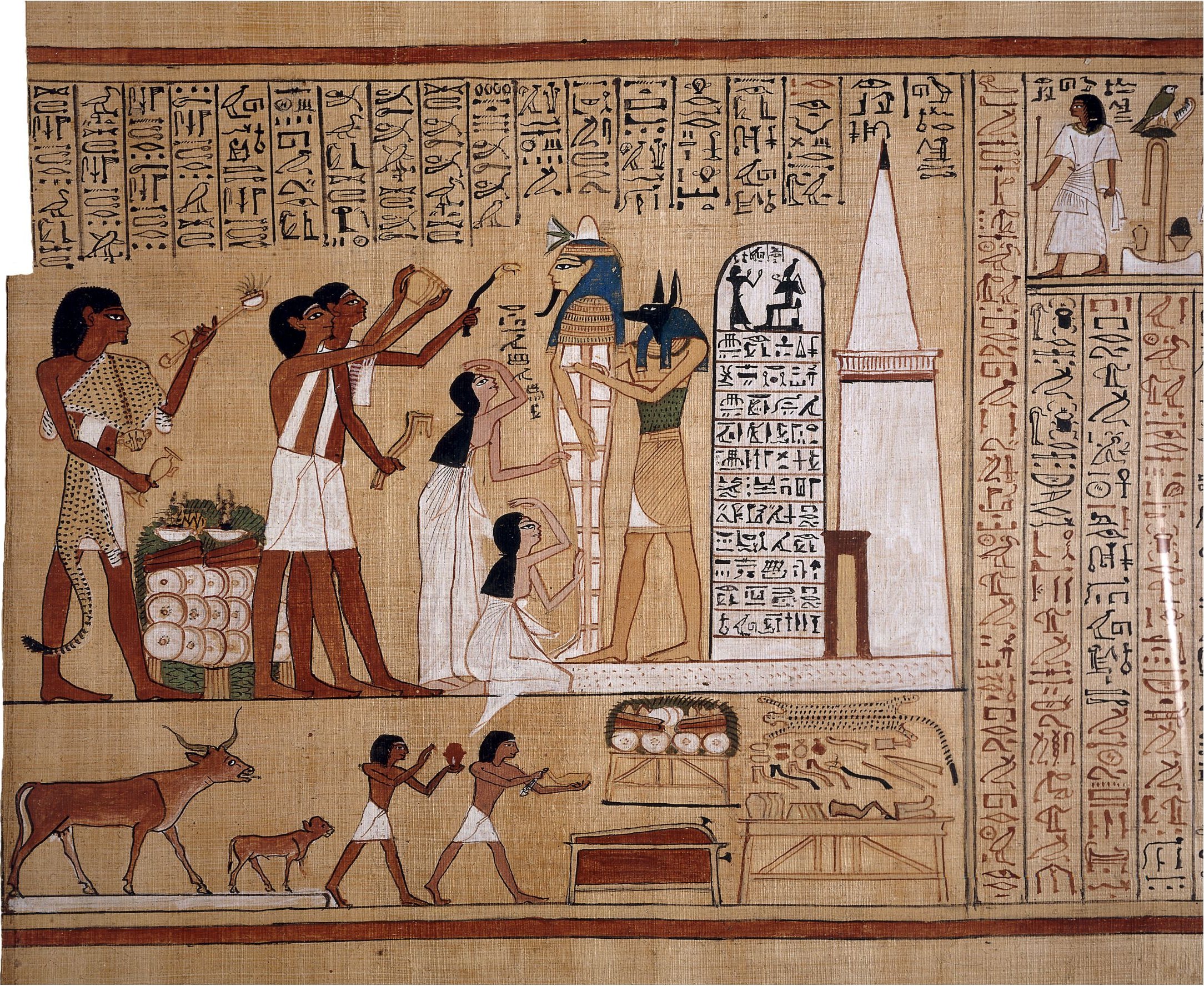

''Book of the Dead''

The

Book of the Dead

The ''Book of the Dead'' is the name given to an Ancient Egyptian funerary texts, ancient Egyptian funerary text generally written on papyrus and used from the beginning of the New Kingdom of Egypt, New Kingdom (around 1550 BC) to around 50 BC ...

were a series of texts written in

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

with various spells to help guide the Egyptians in the

afterlife

The afterlife or life after death is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's Stream of consciousness (psychology), stream of consciousness or Personal identity, identity continues to exist after the death of their ...

.

The interior walls of the pyramid of Unas, the final pharaoh of the Egyptian Fifth Dynasty, are covered in hundreds of magical spells and inscriptions, running from floor to ceiling in vertical columns.

These inscriptions are known as the

Pyramid Texts

The Pyramid Texts are the oldest ancient Egyptian funerary texts, dating to the late Old Kingdom. They are the earliest known corpus of ancient Egyptian religious texts. Written in Old Egyptian, the pyramid texts were carved onto the subterranea ...

and they contain spells needed by the pharaoh in order to survive in the

Afterlife

The afterlife or life after death is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's Stream of consciousness (psychology), stream of consciousness or Personal identity, identity continues to exist after the death of their ...

.

The Pyramid Texts were strictly for royalty only;

the spells were kept secret from commoners and were written only inside royal tombs.

During the chaos and unrest of the

First Intermediate Period

The First Intermediate Period, described as a 'dark period' in ancient Egyptian history, spanned approximately 125 years, c. 2181–2055 BC, after the end of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, Old Kingdom. It comprises the seventh Dynasty, Seventh (altho ...

, however, tomb robbers broke into the pyramids and saw the magical inscriptions.

Commoners began learning the spells and, by the beginning of the

Middle Kingdom, commoners began inscribing similar writings on the sides of their own coffins, hoping that doing so would ensure their own survival in the afterlife.

These writings are known as the

Coffin Texts

The Coffin Texts are a collection of ancient Egyptian funerary spells written on coffins beginning in the First Intermediate Period. They are partially derived from the earlier Pyramid Texts, reserved for royal use only, but contain substantial n ...

.

After a person died, his or her corpse would be mummified and wrapped in linen bandages to ensure that the deceased's body would survive for as long as possible

because the Egyptians believed that a person's soul could only survive in the afterlife for as long as his or her physical body survived here on earth.

The last ceremony before a person's body was sealed away inside the tomb was known as the

Opening of the Mouth

The opening of the mouth ceremony (or ritual) was an ancient Egyptian ritual described in funerary texts such as the Pyramid Texts. From the Old Kingdom to the Roman Period, there is ample evidence of this ceremony, which was believed to give the ...

.

In this ritual, the priests would touch various magical instruments to various parts of the deceased's body, thereby giving the deceased the ability to see, hear, taste, and smell in the afterlife.

Spells

The ''Book of the Dead'' is made up of a number of individual texts and their accompanying illustrations. Most sub-texts begin with the word ''ro'', which can mean "mouth", "speech", "spell", "utterance", "incantation", or "chapter of a book". This ambiguity reflects the similarity in Egyptian thought between ritual speech and magical power. In the context of the ''Book of the Dead'', it is typically translated as either ''chapter'' or ''spell''. In this article, the word ''spell'' is used.

At present, some 192 spells are known,

[Faulkner 1994, p.18] though no single manuscript contains them all. They served a range of purposes. Some are intended to give the deceased mystical knowledge in the afterlife, or perhaps to identify them with the gods: for instance, Spell 17 is an obscure and lengthy description of the god

Atum

Atum (, Egyptian: ''jtm(w)'' or ''tm(w)'', ''reconstructed'' ; Coptic ''Atoum''), sometimes rendered as Atem, Temu, or Tem, is the primordial God in Egyptian mythology from whom all else arose. He created himself and is the father of Shu and ...

. Others are incantations to ensure the different elements of the dead person's being were preserved and reunited, and to give the deceased control over the world around him. Still others protect the deceased from various hostile forces or guide him through the underworld past various obstacles. Famously, two spells also deal with the judgement of the deceased in the

Weighing of the Heart

Ancient Egyptian afterlife beliefs were centered around a variety of complex rituals that were influenced by many aspects of Egyptian culture. Religion was a major contributor, since it was an important social practice that bound all Egyptians to ...

ritual.

Such spells as 26–30, and sometimes spells 6 and 126, relate to the heart and were inscribed on scarabs.

The texts and images of the ''Book of the Dead'' were magical as well as religious. Magic was as legitimate an activity as praying to the gods, even when the magic was aimed at controlling the gods themselves.

[Faulkner 1994, p.146] Indeed, there was little distinction for the Ancient Egyptians between magical and religious practice.

[Faulkner 1994, p.145] The concept of magic (''heka'') was also intimately linked with the spoken and written word. The act of speaking a ritual formula was an act of creation;

[Taylor 2010, p.30] there is a sense in which action and speech were one and the same thing.

The magical power of words extended to the written word. Hieroglyphic script was held to have been invented by the god

Thoth

Thoth (from , borrowed from , , the reflex of " eis like the ibis") is an ancient Egyptian deity. In art, he was often depicted as a man with the head of an African sacred ibis, ibis or a baboon, animals sacred to him. His feminine count ...

, and the hieroglyphs themselves were powerful. Written words conveyed the full force of a spell.

This was even true when the text was abbreviated or omitted, as often occurred in later ''Book of the Dead'' scrolls, particularly if the accompanying images were present. The Egyptians also believed that knowing the name of something gave power over it; thus, the ''Book of the Dead'' equips its owner with the mystical names of many of the entities he would encounter in the afterlife, giving him power over them.

The spells of the ''Book of the Dead'' made use of several magical techniques which can also be seen in other areas of Egyptian life. A number of spells are for magical

amulet

An amulet, also known as a good luck charm or phylactery, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The word "amulet" comes from the Latin word , which Pliny's ''Natural History'' describes as "an object that protects a perso ...

s, which would protect the deceased from harm. In addition to being represented on a ''Book of the Dead'' papyrus, these spells appeared on amulets wound into the wrappings of a mummy.

Everyday magic made use of amulets in huge numbers. Other items in direct contact with the body in the tomb, such as headrests, were also considered to have amuletic value. A number of spells also refer to Egyptian beliefs about the magical healing power of saliva.

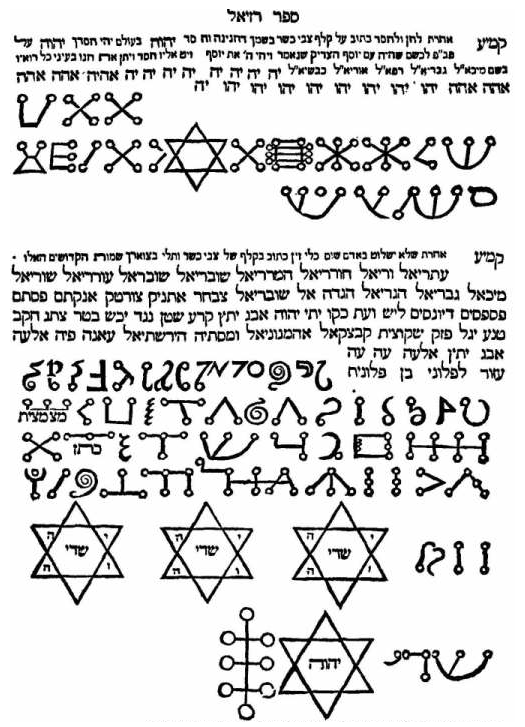

Judea

''

Halakha

''Halakha'' ( ; , ), also Romanization of Hebrew, transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Judaism, Jewish religious laws that are derived from the Torah, Written and Oral Torah. ''Halakha'' is ...

'' (Jewish religious law) forbids

divination

Divination () is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic ritual or practice. Using various methods throughout history, diviners ascertain their interpretations of how a should proceed by reading signs, ...

and other forms of soothsaying, and the

Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

lists many persistent yet condemned divining practices.

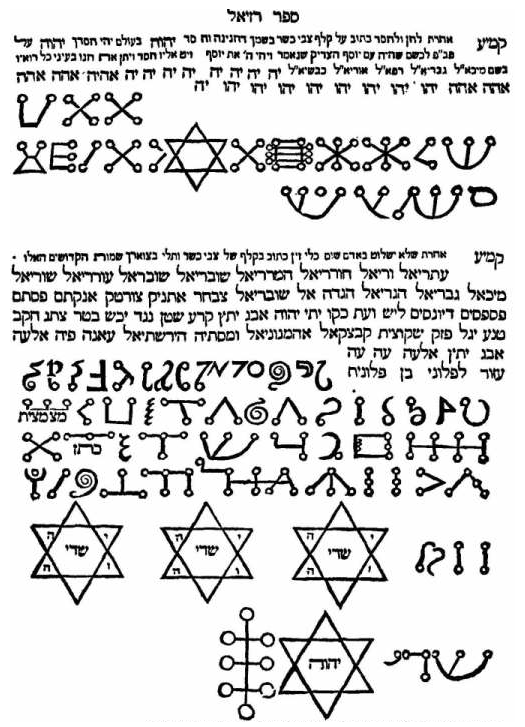

Practical Kabbalah

Practical Kabbalah ( ''Kabbalah Ma'asit'') in historical Judaism, is a branch of Jewish mysticism that concerns the use of magic. It was considered permitted white magic by its practitioners, reserved for the elite, who could separate its spiri ...

in historical Judaism, is a branch of the

Jewish mystical tradition

Academic study of Jewish mysticism, especially since Gershom Scholem's '' Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism'' (1941), draws distinctions between different forms of mysticism which were practiced in different eras of Jewish history. Of these, Kabba ...

that concerns the use of magic. It was considered permitted

white magic

White magic has traditionally referred to the use of supernatural powers or magic for selfless purposes. Practitioners of white magic have been given titles such as wise men or women, healers, white witches or wizards. Many of these people ...

by its practitioners, reserved for the elite, who could separate its spiritual source from

qlipoothic realms of evil if performed under circumstances that were holy (

Q-D-Š

''Q-D-Š'' is a triconsonantal Semitic root meaning " sacred, holy", derived from a concept central to ancient Semitic religion. From a basic verbal meaning "to consecrate, to purify", it could be used as an adjective meaning "holy", or as a ...

) and

pure (טומאה וטהרה, ''tvmh vthrh''). The concern of overstepping Judaism's

strong prohibitions of impure magic ensured it remained a minor tradition in Jewish history. Its teachings include the use of

Divine

Divinity (from Latin ) refers to the quality, presence, or nature of that which is divine—a term that, before the rise of monotheism, evoked a broad and dynamic field of sacred power. In the ancient world, divinity was not limited to a singl ...

and angelic names for

amulet

An amulet, also known as a good luck charm or phylactery, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The word "amulet" comes from the Latin word , which Pliny's ''Natural History'' describes as "an object that protects a perso ...

s and

incantation

An incantation, spell, charm, enchantment, or bewitchery is a magical formula intended to trigger a magical effect on a person or objects. The formula can be spoken, sung, or chanted. An incantation can also be performed during ceremonial ri ...

s.

[Elber, Mark. ''The Everything Kabbalah Book: Explore This Mystical Tradition--From Ancient Rituals to Modern Day Practices'', p. 137. Adams Media, 2006. ] These magical practices of Judaic folk religion which became part of practical Kabbalah date from Talmudic times.

[ The Talmud mentions the use of charms for healing, and a wide range of magical cures were sanctioned by rabbis. It was ruled that any practice actually producing a cure was not to be regarded superstitiously and there has been the widespread practice of medicinal amulets, and folk remedies ''(segullot)'' in Jewish societies across time and geography.

]Jewish law

''Halakha'' ( ; , ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws that are derived from the Written and Oral Torah. ''Halakha'' is based on biblical commandments ('' mit ...

views the practice of witchcraft as being laden with idolatry

Idolatry is the worship of an idol as though it were a deity. In Abrahamic religions (namely Judaism, Samaritanism, Christianity, Islam, and the Baháʼí Faith) idolatry connotes the worship of something or someone other than the Abrahamic ...

and/or necromancy

Necromancy () is the practice of Magic (paranormal), magic involving communication with the Death, dead by Evocation, summoning their spirits as Ghost, apparitions or Vision (spirituality), visions for the purpose of divination; imparting the ...

; both being serious theological and practical offenses in Judaism

Judaism () is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic, Monotheism, monotheistic, ethnic religion that comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Jews, Jewish people. Religious Jews regard Judaism as their means of o ...

. Although Maimonides

Moses ben Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (, ) and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam (), was a Sephardic rabbi and Jewish philosophy, philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah schola ...

vigorously denied the efficacy of all methods of witchcraft, and claimed that the Biblical prohibitions regarding it were precisely to wean the Israelites from practices related to idolatry

Idolatry is the worship of an idol as though it were a deity. In Abrahamic religions (namely Judaism, Samaritanism, Christianity, Islam, and the Baháʼí Faith) idolatry connotes the worship of something or someone other than the Abrahamic ...

. It is acknowledged that while magic exists, it is forbidden to practice it on the basis that it usually involves the worship of other gods. Rabbi

A rabbi (; ) is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi—known as ''semikha''—following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of t ...

s of the Talmud also condemned magic when it produced something other than illusion, giving the example of two men who use magic to pick cucumbers. The one who creates the illusion of picking cucumbers should not be condemned, only the one who actually picks the cucumbers through magic.

Although magic was forbidden by Levitical law in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;["Tanach"](_blank)

. '' Second Temple period

The Second Temple period or post-exilic period in Jewish history denotes the approximately 600 years (516 BCE – 70 CE) during which the Second Temple stood in the city of Jerusalem. It began with the return to Zion and subsequent reconstructio ...

, and particularly well documented in the period following the destruction of the temple into the third, fourth, and fifth centuries CE. Some of the rabbis practiced "magic" themselves or taught the subject. For instance, Rava (amora)

Abba ben Joseph bar Ḥama ( – 352 CE), who is exclusively referred to in the Talmud by the name Rava (), was a Babylonian rabbi who belonged to the fourth generation of amoraim. He is known for his debates with Abaye, and is one of the most ...

created a golem

A golem ( ; ) is an animated Anthropomorphism, anthropomorphic being in Jewish folklore, which is created entirely from inanimate matter, usually clay or mud. The most famous golem narrative involves Judah Loew ben Bezalel, the late 16th-century ...

and sent it to Rav Zeira

Rabbi Zeira (), known before his ''semikhah'' as Rav Zeira () and known in the Jerusalem Talmud as Rabbi Ze'era (), was a Jewish Talmudist of the third generation of ''Amoraim'' who lived in the Land of Israel.

Biography

He was born in Babyloni ...

, and Hanina

Rav Hanina (), also known as Hananiah (; sometimes spelled Hananyah), was a second- or third-generation '' amora'' of the Land of Israel.

Biography

Rav Hanina is noted in tractate Ketubot 56a as a student of Rabbi Yannai, and, in Yevamot 58b a ...

and Hoshaiah studied every Friday together and created a small calf to eat on Shabbat

Shabbat (, , or ; , , ) or the Sabbath (), also called Shabbos (, ) by Ashkenazi Hebrew, Ashkenazim, is Judaism's day of rest on the seventh day of the seven-day week, week—i.e., Friday prayer, Friday–Saturday. On this day, religious Jews ...

. In these cases, the "magic" was seen more as divine miracles (i.e., coming from God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

rather than "unclean" forces) than as witchcraft.

A subcategory of incantation bowls are those used in Jewish magical practice. Aramaic

Aramaic (; ) is a Northwest Semitic language that originated in the ancient region of Syria and quickly spread to Mesopotamia, the southern Levant, Sinai, southeastern Anatolia, and Eastern Arabia, where it has been continually written a ...

incantation bowls are an important source of knowledge about Jewish magical practices.

Judaism does make it clear that Jews shall not try to learn about the ways of witches and that witches are to be put to death. Judaism's most famous reference to a medium is undoubtedly the Witch of Endor

The Witch of Endor (), according to the Hebrew Bible, was consulted by Saul to summon the spirit of the prophet Samuel. Saul wished to receive advice on defeating the Philistines in battle after prior attempts to consult God through sacred lots a ...

whom Saul

Saul (; , ; , ; ) was a monarch of ancient Israel and Judah and, according to the Hebrew Bible and Old Testament, the first king of the United Monarchy, a polity of uncertain historicity. His reign, traditionally placed in the late eleventh c ...

consults, as recounted in 1 Samuel

The Book of Samuel () is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Samuel) in the Old Testament. The book is part of the Deuteronomistic history, a series of books (Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings) that constitute a theological ...

28.

Greco-Roman world

The English word magic has its origins in ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

.

During the late sixth and early fifth centuries BCE, the Persian ''maguš'' was Graecicized and introduced into the ancient Greek language as ''μάγος'' and ''μαγεία''. In doing so it transformed meaning, gaining negative connotations, with the ''magos'' being regarded as a charlatan whose ritual practices were fraudulent, strange, unconventional, and dangerous. As noted by Davies, for the ancient Greeks—and subsequently for the ancient Romans—"magic was not distinct from religion but rather an unwelcome, improper expression of it—the religion of the other". The historian Richard Gordon suggested that for the ancient Greeks, being accused of practicing magic was "a form of insult".

This change in meaning was influenced by the military conflicts that the Greek city-states were then engaged in against the Persian Empire. In this context, the term makes appearances in such surviving text as Sophocles

Sophocles ( 497/496 – winter 406/405 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. was an ancient Greek tragedian known as one of three from whom at least two plays have survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or contemporary with, those ...

' ''Oedipus Rex

''Oedipus Rex'', also known by its Greek title, ''Oedipus Tyrannus'' (, ), or ''Oedipus the King'', is an Athenian tragedy by Sophocles. While some scholars have argued that the play was first performed , this is highly uncertain. Originally, to ...

'', Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; ; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician and philosopher of the Classical Greece, classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of medicine. He is traditionally referr ...

' ''De morbo sacro'', and Gorgias

Gorgias ( ; ; – ) was an ancient Greek sophist, pre-Socratic philosopher, and rhetorician who was a native of Leontinoi in Sicily. Several doxographers report that he was a pupil of Empedocles, although he would only have been a few years ...

' ''Encomium of Helen

Gorgias ( ; ; – ) was an ancient Greek sophist, pre-Socratic philosopher, and rhetorician who was a native of Leontinoi in Sicily. Several doxographers report that he was a pupil of Empedocles, although he would only have been a few years y ...

''. In Sophocles' play, for example, the character Oedipus

Oedipus (, ; "swollen foot") was a mythical Greek king of Thebes. A tragic hero in Greek mythology, Oedipus fulfilled a prophecy that he would end up killing his father and marrying his mother, thereby bringing disaster to his city and family. ...

derogatorily refers to the seer Tiresius as a ''magos''—in this context meaning something akin to quack or charlatan—reflecting how this epithet was no longer reserved only for Persians.

In the first century BCE, the Greek concept of the ''magos'' was adopted into Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

and used by a number of ancient Roman

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

writers as ''magus'' and ''magia''. The earliest known Latin use of the term was in Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

's ''Eclogue

An eclogue is a poem in a classical style on a pastoral subject. Poems in the genre are sometimes also called bucolics. The term is also used for a musical genre thought of as evoking a pastoral scene.

Classical beginnings

The form of the word ...

'', written around 40 BCE, which makes reference to ''magicis... sacris'' (magic rites). The Romans already had other terms for the negative use of supernatural powers, such as ''veneficus'' and ''saga''. The Roman use of the term was similar to that of the Greeks, but placed greater emphasis on the judicial application of it. Within the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, laws would be introduced criminalising things regarded as magic.

In ancient Roman society, magic was associated with societies to the east of the empire; the first century CE writer Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

for instance claimed that magic had been created by the Iranian philosopher Zoroaster

Zarathushtra Spitama, more commonly known as Zoroaster or Zarathustra, was an Iranian peoples, Iranian religious reformer who challenged the tenets of the contemporary Ancient Iranian religion, becoming the spiritual founder of Zoroastrianism ...

, and that it had then been brought west into Greece by the magician Osthanes

Ostanes (from Greek ), also spelled Hostanes and Osthanes, is a legendary Persian magus and alchemist. It was the pen-name used by several pseudo-anonymous authors of Greek and Latin works from Hellenistic period onwards. Together with Pseudo- ...

, who accompanied the military campaigns of the Persian King Xerxes.

Ancient Greek scholarship of the 20th century, almost certainly influenced by Christianising preconceptions of the meanings of magic and religion

People who believe in magic can be found in all societies, regardless of whether they have organized religious hierarchies, including formal clergy, or more informal systems. Such concepts tend to appear more frequently in cultures based in p ...

, and the wish to establish Greek culture as the foundation of Western rationality, developed a theory of ancient Greek magic as primitive and insignificant, and thereby essentially separate from Homeric

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his authorship, Homer is ...

, communal (''polis'') religion. Since the last decade of the century, however, recognising the ubiquity and respectability of acts such as ''katadesmoi'' ( binding spells), described as magic by modern and ancient observers alike, scholars have been compelled to abandon this viewpoint.mystery cults

Mystery religions, mystery cults, sacred mysteries or simply mysteries (), were religious schools of the Greco-Roman world for which participation was reserved to initiates ''(mystai)''. The main characteristic of these religious schools was th ...

have been similarly re-evaluated:magical papyri Magical papyri may refer to:

* Coptic magical papyri

* Greek magical papyri

*Jewish magical papyri

Jewish magical papyri are a subclass of papyri with specific Jewish magical uses, and which shed light on popular belief during the late Second Temp ...

, in Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, Coptic, and Demotic

Demotic may refer to:

* Demotic Greek, the modern vernacular form of the Greek language

* Demotic (Egyptian), an ancient Egyptian script and version of the language

* Chữ Nôm

Chữ Nôm (, ) is a logographic writing system formerly used t ...

, have been recovered and translated. They contain early instances of:

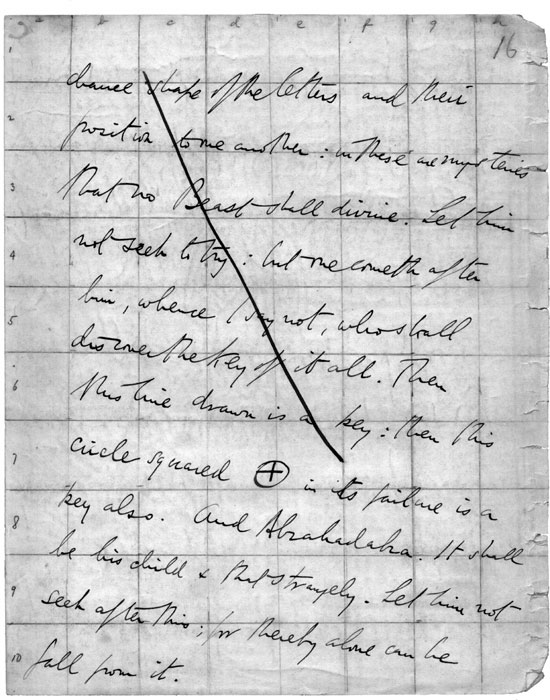

* the use of magic word

Magic words are phrases used in fantasy fiction or by Magic (illusion), stage magicians. Frequently such words are presented as being part of a Divine language, divine, Adamic language, adamic, or other Twilight language, secret or Language of t ...

s said to have the power to command spirits;

* the use of mysterious symbol

A symbol is a mark, Sign (semiotics), sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, physical object, object, or wikt:relationship, relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by cr ...

s or sigils which are thought to be useful when invoking or evoking spirits.Codex Theodosianus

The ''Codex Theodosianus'' ("Theodosian Code") is a compilation of the laws of the Roman Empire under the Christian emperors since 312. A commission was established by Emperor Theodosius II and his co-emperor Valentinian III on 26 March 429 an ...

'' (438 AD) states:If any wizard therefore or person imbued with magical contamination who is called by custom of the people a magician...should be apprehended in my retinue, or in that of the Caesar, he shall not escape punishment and torture by the protection of his rank.

Middle Ages

In the first century CE, early Christian authors absorbed the Greco-Roman

The Greco-Roman world , also Greco-Roman civilization, Greco-Roman culture or Greco-Latin culture (spelled Græco-Roman or Graeco-Roman in British English), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and co ...

concept of magic and incorporated it into their developing Christian theology

Christian theology is the theology – the systematic study of the divine and religion – of Christianity, Christian belief and practice. It concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and of the New Testament, as well as on Ch ...

. These Christians retained the already implied Greco-Roman negative stereotypes of the term and extended them by incorporating conceptual patterns borrowed from Jewish thought, in particular the opposition of magic and miracle

A miracle is an event that is inexplicable by natural or scientific lawsOne dictionary define"Miracle"as: "A surprising and welcome event that is not explicable by natural or scientific laws and is therefore considered to be the work of a divi ...

. Some early Christian authors followed the Greek-Roman thinking by ascribing the origin of magic to the human realm, mainly to Zoroaster

Zarathushtra Spitama, more commonly known as Zoroaster or Zarathustra, was an Iranian peoples, Iranian religious reformer who challenged the tenets of the contemporary Ancient Iranian religion, becoming the spiritual founder of Zoroastrianism ...

and Osthanes

Ostanes (from Greek ), also spelled Hostanes and Osthanes, is a legendary Persian magus and alchemist. It was the pen-name used by several pseudo-anonymous authors of Greek and Latin works from Hellenistic period onwards. Together with Pseudo- ...

. The Christian view was that magic was a product of the Babylonians, Persians, or Egyptians. The Christians shared with earlier classical culture the idea that magic was something distinct from proper religion, although drew their distinction between the two in different ways.

For early Christian writers like

For early Christian writers like Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

, magic did not merely constitute fraudulent and unsanctioned ritual practices, but was the very opposite of religion because it relied upon cooperation from demons

A demon is a malevolent supernatural entity. Historically, belief in demons, or stories about demons, occurs in folklore, mythology, religion, occultism, and literature; these beliefs are reflected in media including

fiction, comics, film, t ...

, the henchmen of Satan

Satan, also known as the Devil, is a devilish entity in Abrahamic religions who seduces humans into sin (or falsehood). In Judaism, Satan is seen as an agent subservient to God, typically regarded as a metaphor for the '' yetzer hara'', or ' ...

. In this, Christian ideas of magic were closely linked to the Christian category of paganism

Paganism (, later 'civilian') is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Christianity, Judaism, and Samaritanism. In the time of the ...

, and both magic and paganism were regarded as belonging under the broader category of ''superstitio'' (superstition

A superstition is any belief or practice considered by non-practitioners to be irrational or supernatural, attributed to fate or magic (supernatural), magic, perceived supernatural influence, or fear of that which is unknown. It is commonly app ...

), another term borrowed from pre-Christian Roman culture. This Christian emphasis on the inherent immorality and wrongness of magic as something conflicting with good religion was far starker than the approach in the other large monotheistic

Monotheism is the belief that one God is the only, or at least the dominant deity.F. L. Cross, Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. A ...

religions of the period, Judaism and Islam. For instance, while Christians regarded demons as inherently evil, the jinn

Jinn or djinn (), alternatively genies, are supernatural beings in pre-Islamic Arabian religion and Islam.

Their existence is generally defined as parallel to humans, as they have free will, are accountable for their deeds, and can be either ...

—comparable entities in Islamic mythology

Islamic mythology is the body of myths associated with Islam and the Quran. Islam is a religion that is more concerned with social order and law than with religious rituals or myths. The primary focus of Islam is the practical and rational pra ...

—were perceived as more ambivalent figures by Muslims.

The model of the magician in Christian thought was provided by Simon Magus

Simon Magus (Greek Σίμων ὁ μάγος, Latin: Simon Magus), also known as Simon the Sorcerer or Simon the Magician, was a religious figure whose confrontation with Peter is recorded in the Acts of the Apostles. The act of simony, or payi ...

, (Simon the Magician), a figure who opposed Saint Peter

Saint Peter (born Shimon Bar Yonah; 1 BC – AD 64/68), also known as Peter the Apostle, Simon Peter, Simeon, Simon, or Cephas, was one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus and one of the first leaders of the Jewish Christian#Jerusalem ekklēsia, e ...

in both the Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles (, ''Práxeis Apostólōn''; ) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of The gospel, its message to the Roman Empire.

Acts and the Gospel of Luke make u ...

and the apocryphal yet influential Acts of Peter

The Acts of Peter is one of the earliest of the apocryphal Acts of the Apostles (genre), Acts of the Apostles in Christianity, dating to the late 2nd century AD. The majority of the text has survived only in the Vetus Latina, Latin translation of ...

. The historian Michael D. Bailey stated that in medieval Europe, magic was a "relatively broad and encompassing category". Christian theologians believed that there were multiple different forms of magic, the majority of which were types of divination

Divination () is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic ritual or practice. Using various methods throughout history, diviners ascertain their interpretations of how a should proceed by reading signs, ...

, for instance, Isidore of Seville

Isidore of Seville (; 4 April 636) was a Spania, Hispano-Roman scholar, theologian and Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Seville, archbishop of Seville. He is widely regarded, in the words of the 19th-century historian Charles Forbes René de Montal ...

produced a catalogue of things he regarded as magic in which he listed divination by the four elements i.e. geomancy

Geomancy, a compound of Greek roots denoting "earth divination", was originally used to mean methods of divination that interpret geographic features, markings on the ground, or the patterns formed by soil, rock (geology), rocks, or sand. Its d ...

, hydromancy

Hydromancy (Ancient Greek ὑδρομαντεία, ''water-divination'',Liddell, H.G. & Scott, R. (1940). ''A Greek-English Lexicon. revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones. with the assistance of. Roderick McKenzie.'' Oxford ...

, aeromancy

Aeromancy (from Greek ἀήρ ''aḗr'', "air", and ''manteia'', "divination") is divination that is conducted by interpreting atmospheric conditions. Alternate terms include "arologie", "aeriology", and "aërology".

Practice

Aeromancy uses clo ...

, and pyromancy

Pyromancy (Ancient Greek ἐμπυρία (empyria), ''divination by fire'')Liddell, H.G. & Scott, R. (1940). ''A Greek-English Lexicon. revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones. with the assistance of. Roderick McKenzie.'' Oxf ...

, as well as by observation of natural phenomena e.g. the flight of birds and astrology. He also mentioned enchantment and ligatures (the medical use of magical objects bound to the patient) as being magical. Medieval Europe also saw magic come to be associated with the Old Testament figure of Solomon

Solomon (), also called Jedidiah, was the fourth monarch of the Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy), Kingdom of Israel and Judah, according to the Hebrew Bible. The successor of his father David, he is described as having been the penultimate ...

; various grimoire

A grimoire () (also known as a book of spells, magic book, or a spellbook) is a textbook of magic, typically including instructions on how to create magical objects like talismans and amulets, how to perform magical spells, charms, and divin ...

s, or books outlining magical practices, were written that claimed to have been written by Solomon, most notably the Key of Solomon

The ''Key of Solomon'' (; ), also known as the ''Greater Key of Solomon'', is a pseudepigraphical grimoire attributed to Solomon, King Solomon. It probably dates back to the 14th or 15th century Italian Renaissance. It presents a typical exampl ...

.

In early medieval Europe, ''magia'' was a term of condemnation. In medieval Europe, Christians often suspected Muslims and Jews of engaging in magical practices; in certain cases, these perceived magical rites—including the alleged Jewish sacrifice of Christian children—resulted in Christians massacring these religious minorities. Christian groups often also accused other, rival Christian groups—which they regarded as heretical

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Christianity, Judai ...

—of engaging in magical activities. Medieval Europe also saw the term ''maleficium'' applied to forms of magic that were conducted with the intention of causing harm. The later Middle Ages saw words for these practitioners of harmful magical acts appear in various European languages: ''sorcière'' in French, ''Hexe'' in German, ''strega'' in Italian, and ''bruja'' in Spanish. The English term for malevolent practitioners of magic, witch, derived from the earlier Old English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

term ''wicce''.

Ars Magica or magic is a major component and supporting contribution to the belief and practice of spiritual, and in many cases, physical healing throughout the Middle Ages. Emanating from many modern interpretations lies a trail of misconceptions about magic, one of the largest revolving around wickedness or the existence of nefarious beings who practice it. These misinterpretations stem from numerous acts or rituals that have been performed throughout antiquity, and due to their exoticism from the commoner's perspective, the rituals invoked uneasiness and an even stronger sense of dismissal. In the medieval Jewish view, the separation of the

In the medieval Jewish view, the separation of the mystical

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight ...

and magical elements of Kabbalah, dividing it into speculative theological Kabbalah (''Kabbalah Iyyunit'') with its meditative traditions, and theurgic practical Kabbalah (''Kabbalah Ma'asit''), had occurred by the beginning of the 14th century.

One societal force in the Middle Ages more powerful than the singular commoner, the Christian Church, rejected magic as a whole because it was viewed as a means of tampering with the natural world in a supernatural manner associated with the biblical

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) biblical languages ...

verses of Deuteronomy 18:9–12. Despite the many negative connotations which surround the term magic, there exist many elements that are seen in a divine or holy light.

Diversified instruments or rituals used in medieval magic include, but are not limited to: various amulets, talismans, potions, as well as specific chants, dances, and prayer

File:Prayers-collage.png, 300px, alt=Collage of various religionists praying – Clickable Image, Collage of various religionists praying ''(Clickable image – use cursor to identify.)''

rect 0 0 1000 1000 Shinto festivalgoer praying in front ...

s. Along with these rituals are the adversely imbued notions of demonic participation which influence of them. The idea that magic was devised, taught, and worked by demons would have seemed reasonable to anyone who read the Greek magical papyri or the Sefer-ha-Razim and found that healing magic appeared alongside rituals for killing people, gaining wealth, or personal advantage, and coercing women into sexual submission. Archaeology is contributing to a fuller understanding of ritual practices performed in the home, on the body and in monastic and church settings.

The Islamic reaction towards magic did not condemn magic in general and distinguished between magic which can heal sickness and possession

Possession may refer to:

Law

*Dependent territory, an area of land over which another country exercises sovereignty, but which does not have the full right of participation in that country's governance

*Drug possession, a crime

*Ownership

*Pe ...

, and sorcery. The former is therefore a special gift from God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

, while the latter is achieved through help of Jinn

Jinn or djinn (), alternatively genies, are supernatural beings in pre-Islamic Arabian religion and Islam.

Their existence is generally defined as parallel to humans, as they have free will, are accountable for their deeds, and can be either ...

and devils

A devil is the personification of evil as it is conceived in many and various cultures and religious traditions.

Devil or Devils may also refer to:

* Satan

* Devil in Christianity

* Demon

* Folk devil

Art, entertainment, and media

Film and ...

. Ibn al-Nadim

Abū al-Faraj Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq an-Nadīm (), also Ibn Abī Yaʿqūb Isḥāq ibn Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq al-Warrāq, and commonly known by the '' nasab'' (patronymic) Ibn an-Nadīm (; died 17 September 995 or 998), was an important Muslim ...

held that exorcist

In some religions, an exorcist (from the Greek „ἐξορκιστής“) is a person who is believed to be able to cast out the devil or performs the ridding of demons or other supernatural beings who are alleged to have possessed a person ...

s gain their power by their obedience to God, while sorcerers please the devils by acts of disobedience and sacrifices and they in return do him a favor. According to Ibn Arabi

Ibn Arabi (July 1165–November 1240) was an Andalusian Sunni

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam and the largest religious denomination in the world. It holds that Muhammad did not appoint any successor and that his closest com ...

, Al-Ḥajjāj ibn Yusuf al-Shubarbuli was able to walk on water due to his piety. According to the Quran 2:102, magic was also taught to humans by devils and the fallen angels Harut and Marut

Harut and Marut () are a pair of angels mentioned in the Quran Surah 2:102, who teach the arts of sorcery (''siḥr'') in Babylon. According to Quranic exegesis (''tafsīr''), when Harut and Marut complained about mankinds' wickedness, they we ...

.

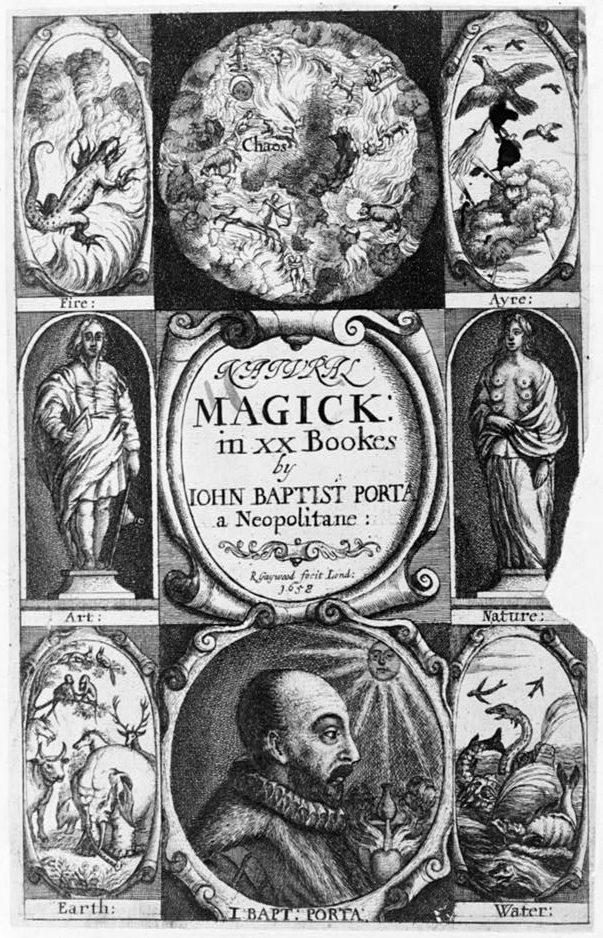

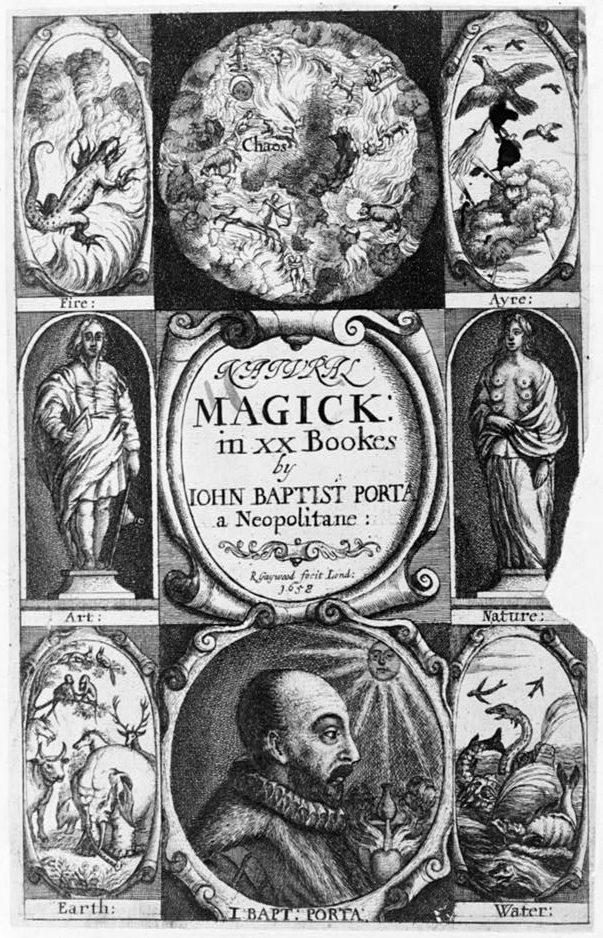

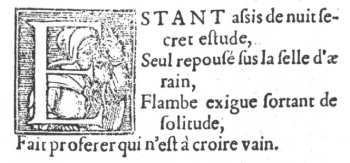

During the early modern period, the concept of magic underwent a more positive reassessment through the development of the concept of ''

During the early modern period, the concept of magic underwent a more positive reassessment through the development of the concept of ''magia naturalis

' (in English, ''Natural Magic'') is a work of popular science by Giambattista della Porta first published in Naples in 1558. Its popularity ensured it was republished in five Latin editions within ten years, with translations into Italian (1560 ...

'' (natural magic). This was a term introduced and developed by two Italian humanists, Marsilio Ficino

Marsilio Ficino (; Latin name: ; 19 October 1433 – 1 October 1499) was an Italian scholar and Catholic priest who was one of the most influential humanist philosophers of the early Italian Renaissance. He was an astrologer, a reviver of Neo ...

and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola

Giovanni Pico dei conti della Mirandola e della Concordia ( ; ; ; 24 February 146317 November 1494), known as Pico della Mirandola, was an Italian Renaissance nobleman and philosopher. He is famed for the events of 1486, when, at the age of 23, ...

. For them, ''magia'' was viewed as an elemental force pervading many natural processes, and thus was fundamentally distinct from the mainstream Christian idea of demonic magic. Their ideas influenced an array of later philosophers and writers, among them Paracelsus

Paracelsus (; ; 1493 – 24 September 1541), born Theophrastus von Hohenheim (full name Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim), was a Swiss physician, alchemist, lay theologian, and philosopher of the German Renaissance.

H ...

, Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno ( , ; ; born Filippo Bruno; January or February 1548 – 17 February 1600) was an Italian philosopher, poet, alchemist, astrologer, cosmological theorist, and esotericist. He is known for his cosmological theories, which concep ...

, Johannes Reuchlin

Johann Reuchlin (; 29 January 1455 – 30 June 1522), sometimes called Johannes, was a German Catholic humanist and a scholar of Greek and Hebrew, whose work also took him to modern-day Austria, Switzerland, Italy, and France. Most of Reuchlin's c ...

, and Johannes Trithemius

Johannes Trithemius (; 1 February 1462 – 13 December 1516), born Johann Heidenberg, was a German Benedictine abbot and a polymath who was active in the German Renaissance as a Lexicography, lexicographer, chronicler, Cryptography, cryptograph ...

. According to the historian Richard Kieckhefer

Richard Kieckhefer (born 1946) is an American medievalist, religious historian, scholar of church architecture, and author. He is Professor of History and John Evans Professor of Religious Studies at Northwestern University.

Education

After an un ...

, the concept of ''magia naturalis'' took "firm hold in European culture" during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, attracting the interest of natural philosophers

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the developme ...

of various theoretical orientations, including Aristotelians

Aristotelianism ( ) is a philosophical tradition inspired by the work of Aristotle, usually characterized by deductive logic and an analytic inductive method in the study of natural philosophy and metaphysics. It covers the treatment of the soci ...

, Neoplatonists

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common i ...

, and Hermeticists

Hermeticism, or Hermetism, is a philosophical and religious tradition rooted in the teachings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, a syncretism, syncretic figure combining elements of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth. This system e ...

.

Adherents of this position argued that ''magia'' could appear in both good and bad forms; in 1625, the French librarian Gabriel Naudé

Gabriel Naudé (2 February 1600 – 10 July 1653) was a French librarian and scholar. He was a prolific writer who produced works on many subjects including politics, religion, history and the supernatural. In 1627, he published an influential b ...

wrote his ''Apology for all the Wise Men Falsely Suspected of Magic'', in which he distinguished "Mosoaicall Magick"—which he claimed came from God and included prophecies, miracles, and speaking in tongues

Speaking in tongues, also known as glossolalia, is an activity or practice in which people utter words or speech-like sounds, often thought by believers to be languages unknown to the speaker. One definition used by linguists is the fluid voc ...

—from "geotick" magic caused by demons. While the proponents of ''magia naturalis'' insisted that this did not rely on the actions of demons, critics disagreed, arguing that the demons had simply deceived these magicians. By the seventeenth century the concept of ''magia naturalis'' had moved in increasingly 'naturalistic' directions, with the distinctions between it and science becoming blurred. The validity of ''magia naturalis'' as a concept for understanding the universe then came under increasing criticism during the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

in the eighteenth century.

Despite the attempt to reclaim the term ''magia'' for use in a positive sense, it did not supplant traditional attitudes toward magic in the West, which remained largely negative. At the same time as ''magia naturalis'' was attracting interest and was largely tolerated, Europe saw an active persecution of accused witches believed to be guilty of ''maleficia''. Reflecting the term's continued negative associations, Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

often sought to denigrate Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

sacramental and devotional practices as being magical rather than religious. Many Roman Catholics were concerned by this allegation and for several centuries various Roman Catholic writers devoted attention to arguing that their practices were religious rather than magical. At the same time, Protestants often used the accusation of magic against other Protestant groups which they were in contest with. In this way, the concept of magic was used to prescribe what was appropriate as religious belief and practice.

Similar claims were also being made in the Islamic world during this period. The Arabian cleric Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab

Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhāb ibn Sulaymān al-Tamīmī (1703–1792) was a Sunni Muslim scholar, theologian, preacher, activist, religious leader, jurist, and reformer, who was from Najd in Arabian Peninsula and is considered as the eponymo ...

—founder of Wahhabism

Wahhabism is an exonym for a Salafi revivalist movement within Sunni Islam named after the 18th-century Hanbali scholar Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. It was initially established in the central Arabian region of Najd and later spread to oth ...

—for instance condemned a range of customs and practices such as divination and the veneration of spirits as ''sihr'', which he in turn claimed was a form of ''shirk

Shirk may refer to:

* Shirk (surname)

* Shirk (Islam), in Islam, the sin of idolatry or worshiping beings or things other than God ('attributing an associate (to God)')

* Shirk, Iran, a village in South Khorasan Province, Iran

* Shirk-e Sorjeh ...

'', the sin of idolatry.

Witchcraft in medieval Europe

In the early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages (historiography), Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th to the 10th century. They marked the start o ...

, there were those who both spoke against witchcraft, and those who spoke against accusing others of witchcraft (at all). For example, the '' Pactus Legis Alamannorum'', an early 7th-century code of laws of the Alemanni

The Alemanni or Alamanni were a confederation of Germanic peoples, Germanic tribes

*

*

*

on the Upper Rhine River during the first millennium. First mentioned by Cassius Dio in the context of the campaign of Roman emperor Caracalla of 213 CE ...

confederation of Germanic tribes, lists witchcraft as a punishable crime on equal terms with poisoning. If a free man accuses a free woman of witchcraft or poisoning, the accused may be disculpated either by twelve people swearing an oath on her innocence or by one of her relatives defending her in a trial by combat

Trial by combat (also wager of battle, trial by battle or judicial duel) was a method of Germanic law to settle accusations in the absence of witnesses or a confession in which two parties in dispute fought in single combat; the winner of the ...

. In this case, the accuser is required to pay a fine (''Pactus Legis Alamannorum'' 13). In contrast, Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( ; 2 April 748 – 28 January 814) was List of Frankish kings, King of the Franks from 768, List of kings of the Lombards, King of the Lombards from 774, and Holy Roman Emperor, Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian ...

prescribed the death penalty for anyone who would burn witches, as seen when he imposed Christianity upon the people of Saxony

Saxony, officially the Free State of Saxony, is a landlocked state of Germany, bordering the states of Brandenburg, Saxony-Anhalt, Thuringia, and Bavaria, as well as the countries of Poland and the Czech Republic. Its capital is Dresden, and ...

in 789 and he proclaimed:

Similarly, the Lombard code of 643 states:

This conforms to the thoughts of Saint Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

, who taught that witchcraft did not exist and that the belief in it was heretical.witch trials

A witch hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. Practicing evil spells or incantations was proscribed and punishable in early human civilizations in the Middle East. ...

started becoming more accepted if the accusations of witchcraft were related to heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Heresy in Christian ...

. However, accusations of witchcraft could be for political reasons too, such as in 1425 when Veronika of Desenice

Veronika of Desenice ( or , ; died 17 October 1425) was the second wife of Frederick II, Count of Celje.

She is known for having been subjected to a witch trial by her father-in-law, who objected to her marriage to his son, but failed to have her ...

was accused of witchcraft and murdered even though she was acquitted by a court because her father-in-law did not want her to marry his son.trial of Joan of Arc

The trial of Joan of Arc, a French military leader under Charles VII of France, Charles VII during the Hundred Years' War, began on 9 January 1431 and ended with her execution on 30 May. The trial is one of the most famous in history, becoming ...

in 1431 may be the most famous witch trial of the Middle Ages and can be seen as the beginning of the witch trials of the early modern era. A young woman who led France to victory during the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy ...

, she was sold to the English and accused of heresy because she believed God had designated her to defend her country from invasion. While her capture was initially political, the trial quickly turned to focusing on her claims of divine guidance, leading to heresy and witchcraft being the main focus of her trial. She was given the choice to renounce her divine visions and to stop wearing soldier's clothing, or to be put to death. She renounced her visions and stopped wearing soldier's clothing, but only for four days. Since she again had professed her belief in divine guidance and began wearing men's clothes, she was convicted of heresy and burnt alive at the stake—a punishment that at the time was felt only necessary for witches.

Renaissance practitioners

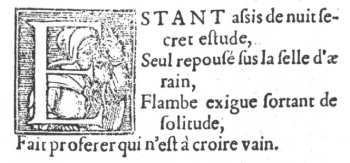

The term "Renaissance magic" originates in 16th-century Renaissance magic

Renaissance magic was a resurgence in Hermeticism and Neoplatonic varieties of the magical arts which arose along with Renaissance humanism in the 15th and 16th centuries CE. During the Renaissance period, magic and occult practices underwent s ...

, referring to practices described in various medieval and Renaissance grimoire

A grimoire () (also known as a book of spells, magic book, or a spellbook) is a textbook of magic, typically including instructions on how to create magical objects like talismans and amulets, how to perform magical spells, charms, and divin ...

s and in collections such as that of Johannes Hartlieb

Johannes Hartlieb (c. 1410Hartlieb's year of birth is unknown; his existence is first attested as the author of ''Kunst der Gedächtnüß'', written during 1430–32, and an estimate of his year of birth as either "c. 1400" or "c. 1410" can be ...

. Georg Pictor uses the term synonymously with ''goetia

(, ) is a type of European sorcery, often referred to as witchcraft, that has been transmitted through grimoires—books containing instructions for performing magical practices. The term "goetia" finds its origins in the Greek word "goes", ...

''.

James Sanford in his 1569 translation of Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (; ; 14 September 1486 – 18 February 1535) was a German Renaissance polymath, physician, legal scholar, soldier, knight, theologian, and occult writer. Agrippa's ''Three Books of Occult Philosophy'' pub ...

's 1526 ''De incertitudine et vanitate scientiarum'' has "The partes of ceremoniall Magicke be Geocie, and Theurgie". For Agrippa, ceremonial magic was in opposition to natural magic

' (in English, ''Natural Magic'') is a work of popular science by Giambattista della Porta first published in Naples in 1558. Its popularity ensured it was republished in five Latin editions within ten years, with translations into Italian (156 ...

. While he had his misgivings about natural magic, which included astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions ...

, alchemy

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

, and also what we would today consider fields of natural science

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

, such as botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

, he was nevertheless prepared to accept it as "the highest peak of natural philosophy". Ceremonial magic, on the other hand, which included all sorts of communication with spirits, including necromancy

Necromancy () is the practice of Magic (paranormal), magic involving communication with the Death, dead by Evocation, summoning their spirits as Ghost, apparitions or Vision (spirituality), visions for the purpose of divination; imparting the ...

and witchcraft

Witchcraft is the use of Magic (supernatural), magic by a person called a witch. Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic to inflict supernatural harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meanin ...

, he denounced in its entirety as impious disobedience towards God.

Both bourgeoisie and nobility in the 15th and 16th centuries showed great fascination with the seven artes magicae

The seven ''artes prohibitae'', or ''artes magicae'', are arts prohibited by canon law as expounded by Johannes Hartlieb in 1456. They were divided into seven types reflecting that of the artes liberales and artes mechanicae.

The categories w ...

, which exerted an exotic charm by their ascription to Arabic, Jewish, Romani, and Egyptian sources. There was great uncertainty in distinguishing practices of vain superstition, blasphemous occultism, and perfectly sound scholarly knowledge or pious ritual. Intellectual and spiritual tensions erupted in the Early Modern witch craze, further reinforced by the turmoils of the Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

, especially in Germany, England, and Scotland.Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

humanism

Humanism is a philosophy, philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and Agency (philosophy), agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The me ...

saw a resurgence in hermeticism

Hermeticism, or Hermetism, is a philosophical and religious tradition rooted in the teachings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, a syncretism, syncretic figure combining elements of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth. This system e ...

and Neo-Platonic

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

varieties of ceremonial magic

Ceremonial magic (also known as magick, ritual magic, high magic or learned magic) encompasses a wide variety of rituals of Magic (supernatural), magic. The works included are characterized by ceremony and numerous requisite accessories t ...

. The Renaissance, on the other hand, saw the rise of science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

, in such forms as the dethronement of the Ptolemaic theory of the universe, the distinction of astronomy from astrology, and of chemistry from alchemy.Hasidism

Hasidism () or Hasidic Judaism is a religious movement within Judaism that arose in the 18th century as a Spirituality, spiritual revival movement in contemporary Western Ukraine before spreading rapidly throughout Eastern Europe. Today, most ...