A

democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

is a

political system

In political science, a political system means the form of Political organisation, political organization that can be observed, recognised or otherwise declared by a society or state (polity), state.

It defines the process for making official gov ...

, or a system of decision-making within an institution, organization, or state, in which members have a share of power. Modern democracies are characterized by two capabilities of their citizens that differentiate them fundamentally from earlier forms of government: to intervene in society and have their sovereign (e.g., their representatives) held accountable to the international laws of other governments of their kind. Democratic government is commonly juxtaposed with oligarchic and monarchic systems, which are ruled by a minority and a sole monarch respectively.

Democracy is generally associated with the efforts of the ancient Greeks, whom 18th-century intellectuals such as

Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the principal so ...

considered the founders of Western civilization. These individuals attempted to leverage these early democratic experiments into a new template for post-monarchical political organization. The extent to which these 18th-century democratic revivalists succeeded in turning the democratic ideals of the ancient Greeks into the dominant political institution of the next 300 years is hardly debatable, even if the moral justifications they often employed might be. Nevertheless, the critical historical juncture catalyzed by the resurrection of democratic ideals and institutions fundamentally transformed the ensuing centuries and has dominated the international landscape since the dismantling of the final vestige of the

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

following the end of the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

Modern

representative democracies attempt to bridge the gap between

Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher ('' philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects ...

's depiction of the state of nature and

Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered to be one of the founders ...

's depiction of society as inevitably authoritarian through 'social contracts' that enshrine the rights of the citizens, curtail the power of the state, and grant agency through the

right to vote

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in ...

.

Antiquity

Prehistoric origins

Anthropologists have identified forms of proto-democracy that date back to small bands of hunter-gatherers that predate the establishment of agrarian, sedentary societies and still exist virtually unchanged in isolated indigenous groups today. In these groups of generally 50–100 individuals, often tied closely by familial bonds, decisions are reached by consensus or majority and many times without the designation of any specific chief.

These types of democracy are commonly identified as

tribalism

Tribalism is the state of being organized by, or advocating for, tribes or tribal lifestyles. Human evolution primarily occurred in small hunter-gatherer groups, as opposed to in larger and more recently settled agricultural societies or civilizat ...

, or ''primitive democracy''. In this sense, a ''primitive democracy'' usually takes shape in small communities or villages when there are face-to-face discussions in a village, council or with a leader who has the backing of village elders or other cooperative forms of government.

["Political System"](_blank)

Updated November 17, 2023. ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The is a general knowledge, general-knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It has been published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. since 1768, although the company has changed ownership seven times. The 2010 version of the 15th edition, ...

'' This becomes more complex on a larger scale, such as when the village and city are examined more broadly as political communities. All other forms of rule – including

monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, reigns as head of state for the rest of their life, or until abdication. The extent of the authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutio ...

,

tyranny

A tyrant (), in the modern English language, English usage of the word, is an autocracy, absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurper, usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defen ...

,

aristocracy

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense Economy, economic, Politics, political, and soc ...

, and

oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or t ...

– have flourished in more urban centers, often those with concentrated populations.

["Democracy"](_blank)

Updated March 17, 2024. ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The is a general knowledge, general-knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It has been published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. since 1768, although the company has changed ownership seven times. The 2010 version of the 15th edition, ...

'' David Graeber and David Wengrow, in ''

The Dawn of Everything'', argue in contrast that cities and early settlements were more varied and unpredictable in terms of how their political systems alternated and evolved from more to less democratic.

The concepts (and name) of democracy and constitution as a form of government originated in ancient Athens in the sixth-century BC (circa 508 BC). In ancient Greece, where there were many

city-states

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world throughout history, including cities such as Rome, ...

with different forms of government, democracy ("rule by the ", i.e. citizen body) was contrasted with governance by elites (aristocracy, literally "rule by the best"), by one person (monarchy), by tyrants (tyranny), etc.

Potential proto-democratic societies

Although fifth-century BC Athens is widely considered to have been the first state to develop a sophisticated system of rule that we today call democracy,

[Dunn, 1994, p. 2][Robinson, 1997, pp. 24–5][Thorley, 1996, p. 2][Dunn, 2006, p. 13] in recent decades scholars have explored the possibility that advancements toward democratic government occurred independently in the

Near East

The Near East () is a transcontinental region around the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing the historical Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and coastal areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The term was invented in the 20th ...

, the

Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographic region of Asia below the Himalayas which projects into the Indian Ocean between the Bay of Bengal to the east and the Arabian Sea to the west. It is now divided between Bangladesh, India, and Pakista ...

, and elsewhere before this.

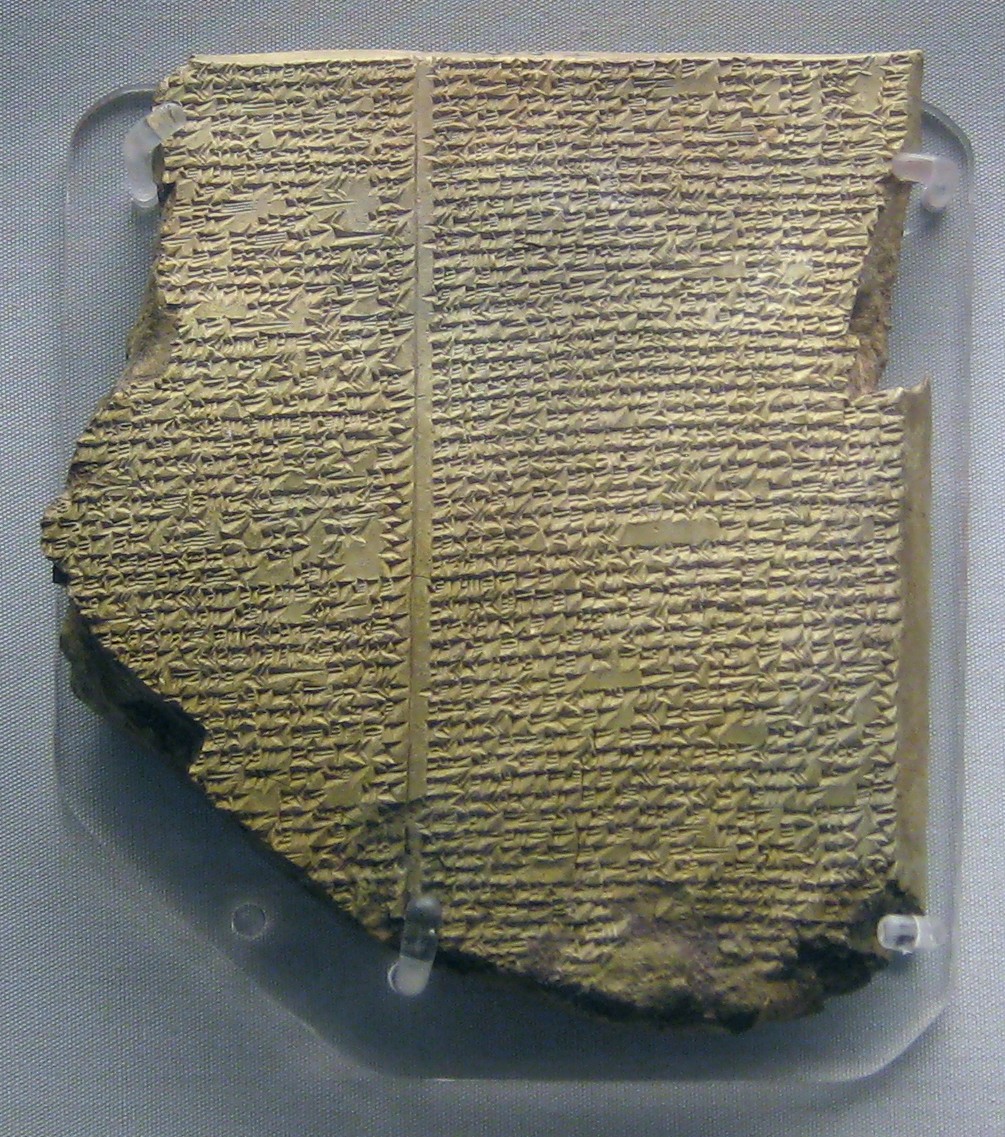

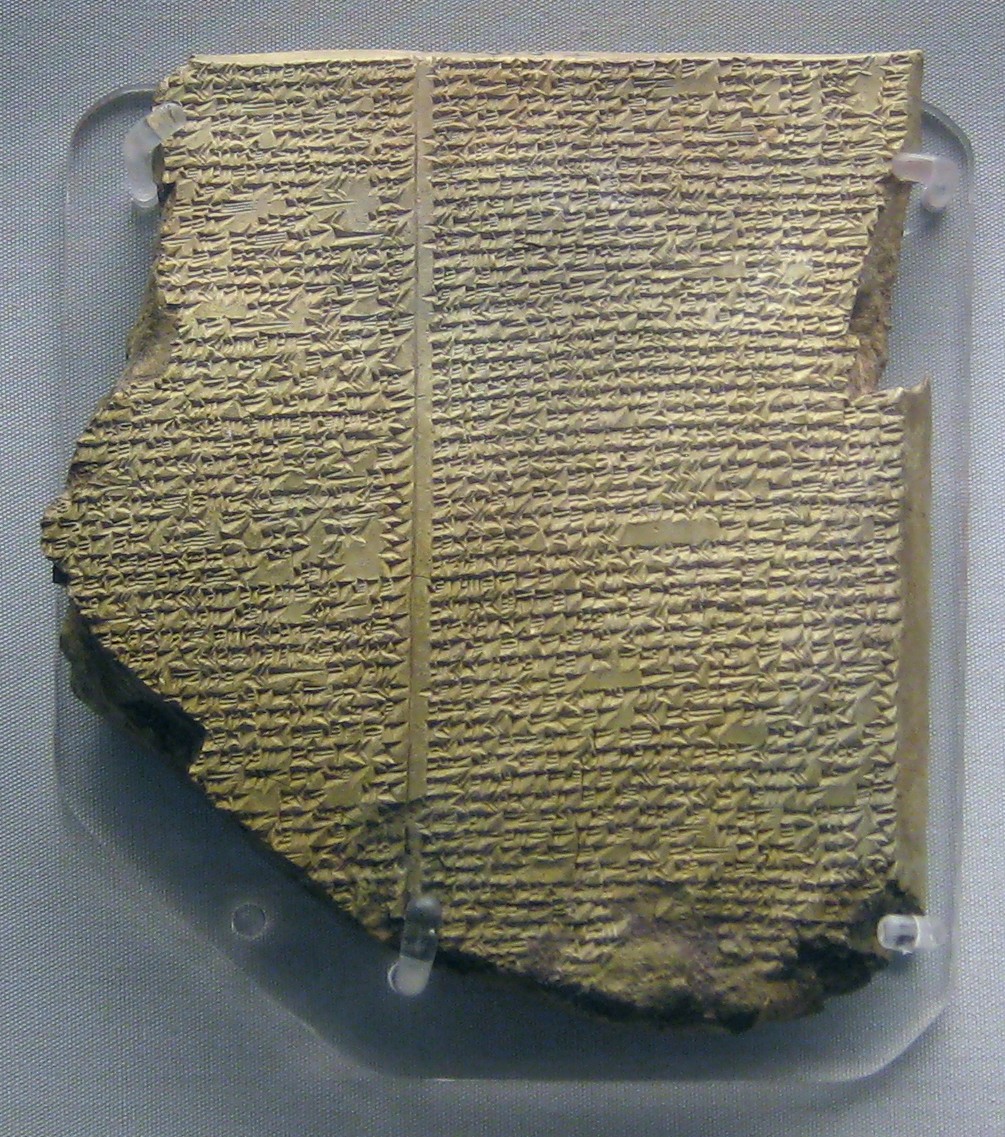

Mesopotamia

Studying pre-

Babylonia

Babylonia (; , ) was an Ancient history, ancient Akkadian language, Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Kuwait, Syria and Iran). It emerged as a ...

n Mesopotamia,

Thorkild Jacobsen used

Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization, located in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (now south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age, early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. ...

ian epic, myth, and historical records to identify what he has called ''primitive democracy''. By this, Jacobsen means a government in which ultimate power rests with the mass of free (non-slave) male citizens, although "the various functions of government are as yet little specialised

ndthe power structure is loose". In early Sumer, kings like

Gilgamesh

Gilgamesh (, ; ; originally ) was a hero in ancient Mesopotamian mythology and the protagonist of the ''Epic of Gilgamesh'', an epic poem written in Akkadian during the late 2nd millennium BC. He was possibly a historical king of the Sumer ...

did not hold the

autocratic

Autocracy is a form of government in which absolute power is held by the head of state and Head of government, government, known as an autocrat. It includes some forms of monarchy and all forms of dictatorship, while it is contrasted with demo ...

power that later Mesopotamian rulers wielded. Rather, major

city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world throughout history, including cities such as Rome, ...

s functioned with councils of elders and "young men" (likely free men bearing arms) that possessed the final political authority, and had to be consulted on all major issues such as war.

The work has gained little outright acceptance. Scholars criticize the use of the word "democracy" in this context since the same evidence also can be interpreted to demonstrate a power struggle between primitive monarchy and noble classes, a struggle in which the common people function more like pawns rather than any kind of sovereign authority. Jacobsen conceded that the vagueness of the evidence prohibits the separation between the ''Mesopotamian democracy'' from a ''primitive oligarchy''.

Phoenicia

The practice of "governing by assembly" was at least part of how ancient Phoenicians made important decisions. One source is the story of Wen-Amon, an Egyptian trader who travelled north to the Phoenician city of Byblos around 1100 BC to trade for Phoenician lumber. After loading his lumber, a group of pirates surrounded Wen-Amon and his cargo ship. The Phoenician prince of Byblos was called in to fix the problem, whereupon he summoned his ''mw-'dwt,'' an old Semitic word meaning assembly, to reach a decision. This shows that Byblos was ruled in part by a popular assembly (drawn from what subpopulation and equipped with exactly what power is not known exactly).

Ancient Iran

Several forms of proto-democratic governance also existed in

Ancient Iran

The history of Iran (also known as Name of Iran, Persia) is intertwined with Greater Iran, which is a socio-cultural region encompassing all of the areas that have witnessed significant settlement or influence exerted by the Iranian peoples and ...

, particularly among the

Medes

The Medes were an Iron Age Iranian peoples, Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media (region), Media between western Iran, western and northern Iran. Around the 11th century BC, they occupied the m ...

,

Achaemenids

The Achaemenid dynasty ( ; ; ; ) was a royal house that ruled the Achaemenid Empire, which eventually stretched from Egypt and Thrace in the west to Central Asia and the Indus Valley in the east.

Origins

The history of the Achaemenid dy ...

, and

Parthians.

The

Gathas, attributed to the Iranian prophet

Zoroaster

Zarathushtra Spitama, more commonly known as Zoroaster or Zarathustra, was an Iranian peoples, Iranian religious reformer who challenged the tenets of the contemporary Ancient Iranian religion, becoming the spiritual founder of Zoroastrianism ...

in 6th century BC, emphasize moral choice, civic responsibility, and the selection of righteous leaders. In the sacred text Yasna 30, Zoroaster calls on people to “listen to the best arguments, ponder with good judgment, and choose freely their path.” The concept of Vohu Khshathra Vairya (lit. “Good Dominion Worthy of Choice”) reflects the ideal of a just, elected rulership. According to scholars, Zoroastrianism promoted a form of spiritual and political democracy, emphasizing individual judgment and non-discrimination between men and women in civic decision-making.

According to

Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental Universal history (genre), universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty ...

, following the fall of the Assyrian Empire, the

Medes

The Medes were an Iron Age Iranian peoples, Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media (region), Media between western Iran, western and northern Iran. Around the 11th century BC, they occupied the m ...

established independent city-states that were “administered in a democratic fashion.” Similarly,

Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

describes the Medes' revolt against the Assyrians as a popular uprising that led to self-governance before eventually transitioning to monarchy under

Deioces

Deioces was the founder and the first king of the Median Kingdom, an ancient polity in western Asia. His name has been mentioned in different forms in various sources, including the ancient Greek historian Herodotus.

The exact date of the era of ...

in 7th century BC.

One of the earliest recorded constitutional debates took place in 522 BCE, following the death of the usurper

Gaumata

Bardiya or Smerdis ( ; ; possibly died 522 BCE), also named as Tanyoxarces (; ) by Ctesias, was a son of Cyrus the Great and the younger brother of Cambyses II, both Persian kings. There are sharply divided views on his life. Bardiya either ...

. Herodotus recounts a pivotal discussion among seven Persian nobles regarding the future of governance.

Otanes proposed a democratic system based on

equality before the law

Equality before the law, also known as equality under the law, equality in the eyes of the law, legal equality, or legal egalitarianism, is the principle that all people must be equally protected by the law. The principle requires a systematic ru ...

, appointment of officials by lot, public deliberation, and collective rule. Though ultimately unsuccessful in swaying the decision, Otanes' speech is seen by some scholars as advocating a radical form of democracy, and his arguments are cited as among the earliest theoretical defenses of democratic governance. Herodotus later defends the historicity of this debate, stating that Otanes had indeed advised the Persians “to become democratic” (demokrateesthai).

During the

Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire (), also known as the Arsacid Empire (), was a major Iranian political and cultural power centered in ancient Iran from 247 BC to 224 AD. Its latter name comes from its founder, Arsaces I, who led the Parni tribe ...

, political power was shared between the monarchy and a

bicameral

Bicameralism is a type of legislature that is divided into two separate Deliberative assembly, assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate ...

parliament known as the ''Magistan'' (Greek: ''Megisthanes''). According to

Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-si ...

and

Justin

Justin may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Justin (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Justin (historian), Latin historian who lived under the Roman Empire

* Justin I (c. 450–527) ...

, the council was composed of noble families (including the

Seven Great Houses of Iran

The Seven Great Houses of Iran, also known as the seven Parthian clans, were seven aristocracies of Parthian origin, who were allied with the Sasanian court. The Parthian clans all claimed ancestry from Achaemenid Persians.

The seven Great House ...

) and religious scholars, primarily the

magi

Magi (), or magus (), is the term for priests in Zoroastrianism and earlier Iranian religions. The earliest known use of the word ''magi'' is in the trilingual inscription written by Darius the Great, known as the Behistun Inscription. Old Per ...

. Although the kings held ultimate power, the parliament often played a decisive role in royal succession and policy-making, suggesting an early model of

constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

. The first session of the Megisthanes is reported to have occurred during the reign of

Mithridates I in 137 BCE.

Indian subcontinent

Another claim for early democratic institutions comes from the independent "

republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

s" of India,

s and

s, which existed as early as the 6th century BC and persisted in some areas until the 4th century. In addition,

Diodorus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which survive intact, b ...

—a Greek historian who wrote two centuries after the time of

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

's invasion of India—mentions that independent and democratic states existed in India.

Key characteristics of the seem to include a monarch, usually known by the name

raja

Raja (; from , IAST ') is a noble or royal Sanskrit title historically used by some Indian subcontinent, Indian rulers and monarchs and highest-ranking nobles. The title was historically used in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia.

T ...

, and a deliberative assembly. The assembly met regularly. It discussed all major state decisions. At least in some states, attendance was open to all free men. This body also had full financial, administrative, and judicial authority. Other officers, who rarely receive any mention, obeyed the decisions of the assembly. Elected by the , the monarch apparently always belonged to a family of the noble class of ''

Kshatriya

Kshatriya () (from Sanskrit ''kṣatra'', "rule, authority"; also called Rajanya) is one of the four varnas (social orders) of Hindu society and is associated with the warrior aristocracy. The Sanskrit term ''kṣatriyaḥ'' is used in the con ...

Varna''. The monarch coordinated his activities with the assembly; in some states, he did so with a council of other nobles. The

Licchavis had a primary governing body of 7,077 rajas, presumably the heads of the most important families. In contrast, the

Shakya

Shakya (Pali, Pāḷi: ; Sanskrit: ) was an ancient Indo-Aryan clan of the northeastern region of South Asia, whose existence is attested during the Iron Age in India, Iron Age. The Shakyas were organised into a Gaṇasaṅgha, (an Aristocrac ...

s, during the period around

Gautama Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha (),*

*

*

was a śramaṇa, wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism. According to Buddhist lege ...

, had the assembly open to all men, rich and poor. Early "republics" or

,

such as

Mallakas, centered in the city of

Kusinagara, and the

Vajji (or Vṛji) League, centered in the city of

Vaishali, existed as early as the 6th century BC and persisted in some areas until the 4th century CE. The most famous clan amongst the ruling confederate tribes of the Vajji Mahajanapada were the

Licchavis. The Magadha kingdom included republican communities such as the community of Rajakumara. Villages had their own assemblies under their local chiefs called Gramakas. Their administrations were divided into executive, judicial, and military functions.

Scholars differ over how best to describe these governments, and the vague, sporadic quality of the evidence allows for wide disagreements. Some emphasize the central role of the assemblies and thus tout them as democracies; other scholars focus on the upper-class domination of the leadership and possible control of the assembly and see an oligarchy or an

aristocracy

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense Economy, economic, Politics, political, and soc ...

.

[Bongard-Levin, 1996, pp. 61–106][Sharma 1968, pp. 109–22] Despite the assembly's obvious power, it has not yet been established whether the composition and participation were truly popular. The first main obstacle is the lack of evidence describing the popular power of the assembly. This is reflected in the ''

Arthashastra

''Kautilya's Arthashastra'' (, ; ) is an Ancient Indian Sanskrit treatise on statecraft, politics, economic policy and military strategy. The text is likely the work of several authors over centuries, starting as a compilation of ''Arthashas ...

'', an ancient handbook for monarchs on how to rule efficiently. It contains a chapter on how to deal with the ''sangas'', which includes injunctions on manipulating the noble leaders, yet it does not mention how to influence the mass of the citizens—a surprising omission if democratic bodies, not the aristocratic families, actively controlled the republican governments. Another issue is the persistence of the

four-tiered Varna class system.

The duties and privileges on the members of each particular caste—rigid enough to prohibit someone sharing a meal with those of another order—might have affected the roles members were expected to play in the state, regardless of the formality of the institutions. A central tenet of democracy is the notion of shared decision-making power. The absence of any concrete notion of citizen equality across these caste system boundaries leads many scholars to claim that the true nature of s and s is not comparable to truly democratic institutions.

Sparta

Ancient Greece, in its early period, was a loose collection of independent

city states called

poleis. Many of these poleis were oligarchies. The most prominent Greek

oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or t ...

, and the state with which democratic Athens is most often and most fruitfully compared, was Sparta. Yet Sparta, in its rejection of private wealth as a primary social differentiator, was a peculiar kind of oligarchy and some scholars note its resemblance to democracy.

[Plato, ''Laws'', 712e-d][Aristotle, ''Politics'', 1294b] In Spartan government, the political power was divided between four bodies: two

Spartan kings (

diarchy

Diarchy (from Greek , ''di-'', "double", and , ''-arkhía'', "ruled"),Occasionally spelled ''dyarchy'', as in the ''Encyclopaedia Britannica'' article on the colonial British institution duarchy, or duumvirate. is a form of government charac ...

), (''Council of Gerontes'' (elders), including the two kings), the

ephors

The ephors were a board of five magistrates in ancient Sparta. They had an extensive range of judicial, religious, legislative, and military powers, and could shape Sparta's home and foreign affairs.

The word "''ephors''" (Ancient Greek ''éph ...

(representatives of the citizens who oversaw the kings), and the (assembly of Spartans).

The two kings served as the head of the government. They ruled simultaneously, but they came from two separate lines. The dual kingship diluted the effective power of the executive office. The kings shared their judicial functions with other members of the . The members of the had to be over the age of 60 and were elected for life. In theory, any Spartan over that age could stand for election. However, in practice, they were selected from wealthy, aristocratic families. The gerousia possessed the crucial power of legislative initiative. Apella, the most democratic element, was the assembly where Spartans above the age of 30 elected the members of the gerousia and the ephors, and accepted or rejected gerousia's proposals. Finally, the five ephors were Spartans chosen in apella to oversee the actions of the kings and other public officials and, if necessary, depose them. They served for one year and could not be re-elected for a second term. Over the years, the ephors held great influence on the formation of foreign policy and acted as the main executive body of the state. Additionally, they had full responsibility for the Spartan educational system, which was essential for maintaining the high standards of the Spartan army. As

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

noted, ephors were the most important key institution of the state, but because often they were appointed from the whole social body it resulted in very poor men holding office, with the ensuing possibility that they could easily be bribed.

The creator of the Spartan system of rule was the legendary lawgiver

Lycurgus

Lycurgus (; ) was the legendary lawgiver of Sparta, credited with the formation of its (), involving political, economic, and social reforms to produce a military-oriented Spartan society in accordance with the Delphic oracle. The Spartans i ...

. He is associated with the drastic reforms that were instituted in Sparta after the revolt of the

helots

The helots (; , ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their exact characteristic ...

in the second half of the 7th century BC. In order to prevent another helot revolt, Lycurgus devised the highly militarized communal system that made Sparta unique among the city-states of Greece. All his reforms were directed towards the three Spartan virtues: equality (among citizens), military fitness, and austerity. It is also probable that Lycurgus delineated the powers of the two traditional organs of the Spartan government, the and the .

[Lycurgus](_blank)

Encyclopædia Britannica Online

The reforms of Lycurgus were written as a list of rules/laws called

Great Rhetra

The Great Rhetra (, literally: Great "Saying" or "Proclamation", charter) was used in two senses by the classical authors. In one sense, it was the Spartan Constitution, believed to have been formulated and established by the quasi-legendary law ...

, making it the world's first written constitution. In the following centuries, Sparta became a military superpower, and its system of rule was admired throughout the Greek world for its political stability. In particular, the concept of equality played an important role in Spartan society. The Spartans referred to themselves as (, ''men of equal status''). It was also reflected in the Spartan public educational system, , where all citizens irrespective of wealth or status had the same education.

This was admired almost universally by contemporaries, from historians such as

Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

and

Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; ; 355/354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian. At the age of 30, he was elected as one of the leaders of the retreating Ancient Greek mercenaries, Greek mercenaries, the Ten Thousand, who had been ...

to philosophers such as

Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

and Aristotle. In addition, the Spartan women, unlike elsewhere, enjoyed "every kind of luxury and intemperance" including rights such as the right to inheritance, property ownership, and public education.

Overall, the Spartans were relatively free to criticize their kings and they were able to depose and exile them. However, despite these 'democratic' elements in the Spartan constitution, there are two cardinal criticisms, classifying Sparta as an oligarchy. First, individual freedom was restricted, since as

Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

writes "no man was allowed to live as he wished", but as in a "military camp" all were engaged in the public service of their . And second, the effectively maintained the biggest share of power of the various governmental bodies.

The political stability of Sparta also meant that no significant changes in the constitution were made. The oligarchic elements of Sparta became even stronger, especially after the influx of gold and silver from the victories in the

Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of th ...

. In addition, Athens, after the

Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of th ...

, was becoming the hegemonic power in the Greek world and disagreements between Sparta and Athens over supremacy emerged. These led to a series of armed conflicts known as the

Peloponnesian War

The Second Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), often called simply the Peloponnesian War (), was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek war fought between Classical Athens, Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Ancien ...

, with Sparta prevailing in the end. However, the war exhausted both and Sparta was in turn humbled by

Thebes at the

Battle of Leuctra

The Battle of Leuctra (, ) was fought on 6 July 371 BC between the Boeotians led by the Thebes (Greece), Thebans, and the History of Sparta, Spartans along with their allies amidst the post–Corinthian War conflict. The battle took place in the ...

in 371 BC. It was all brought to an end a few years later, when

Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon (; 382 BC – October 336 BC) was the king (''basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the ...

crushed what remained of the power of the factional city-states to his South.

Athens

Athens is often regarded by western scholars as the birthplace of democracy and remains an important reference point for democracy, as evidenced by the etymological origins of democracy in English and many other languages being traced back to the Greek words '(common) people' and 'force/might'. Literature about the Athenian democracy spans over centuries with the earliest works being ''

The Republic'' of Plato and ''

Politics

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

'' of Aristotle, continuing in the 16th century with ''

Discourses'' of

Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli (3 May 1469 – 21 June 1527) was a Florentine diplomat, author, philosopher, and historian who lived during the Italian Renaissance. He is best known for his political treatise '' The Prince'' (), writte ...

.

Athens emerged in the 7th century BC, like many other , with a dominating powerful aristocracy. However, this domination led to exploitation, creating significant economic, political, and social problems. These problems were exacerbated early in the 6th century BC; and, as "the many were enslaved to few, the people rose against the notables". At the same time, a number of popular revolutions disrupted traditional aristocracies. This included Sparta in the second half of the 7th century BC. The constitutional reforms implemented by Lycurgus in Sparta introduced a

hoplite

Hoplites ( ) ( ) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The formation discouraged the sold ...

state that showed, in turn, how inherited governments can be changed and lead to military victory. After a period of unrest between the rich and poor, Athenians of all classes turned to

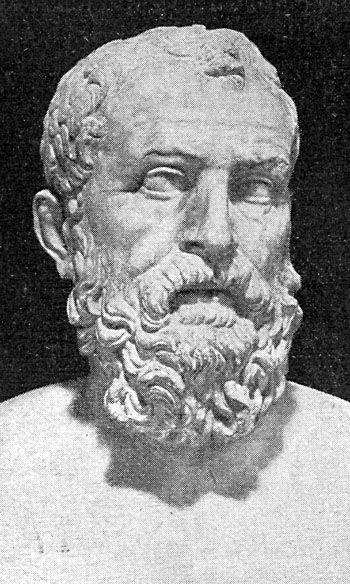

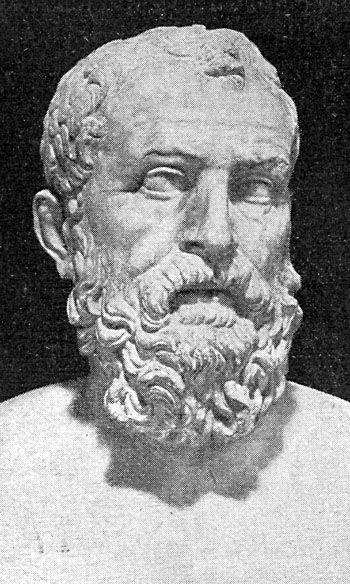

Solon

Solon (; ; BC) was an Archaic Greece#Athens, archaic History of Athens, Athenian statesman, lawmaker, political philosopher, and poet. He is one of the Seven Sages of Greece and credited with laying the foundations for Athenian democracy. ...

to act as a mediator between rival factions, and reached a generally satisfactory solution to their problems.

[

]

Solon and the foundations of democracy

Solon ( BC), an Athenian (Greek) of noble descent but moderate means, was a

Solon ( BC), an Athenian (Greek) of noble descent but moderate means, was a lyric

Lyric may refer to:

* Lyrics, the words, often in verse form, which are sung, usually to a melody, and constitute the semantic content of a song

* Lyric poetry is a form of poetry that expresses a subjective, personal point of view

* Lyric, from t ...

poet and later a lawmaker; Plutarch ranked him as one of the Seven Sages of the ancient world.["Solon"]

''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Solon attempted to satisfy all sides by alleviating the suffering of the poor majority without removing all the privileges of the rich minority. Solon divided the Athenians into four property classes, with different rights and duties for each. As the Rhetra did in Lycurgian Sparta, Solon formalized the composition and functions of the governmental bodies. All citizens gained the right to attend the Ecclesia (Assembly) and to vote. The Ecclesia became, in principle, the sovereign body, entitled to pass laws and decrees, elect officials, and hear appeals from the most important decisions of the court

A court is an institution, often a government entity, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between Party (law), parties and Administration of justice, administer justice in Civil law (common law), civil, Criminal law, criminal, an ...

s.[ All but those in the poorest group might serve, a year at a time, on a new Boule of 400, which was to prepare the agenda for the Ecclesia. The higher governmental posts, those of the ]archons

''Archon'' (, plural: , ''árchontes'') is a Greek word that means "ruler", frequently used as the title of a specific public office. It is the masculine present participle of the verb stem , meaning "to be first, to rule", derived from the same ...

(magistrates), were reserved for citizens of the top two income groups. The retired archons became members of the Areopagus

The Areopagus () is a prominent rock outcropping located northwest of the Acropolis in Athens, Greece. Its English name is the Late Latin composite form of the Greek name Areios Pagos, translated "Hill of Ares" (). The name ''Areopagus'' also r ...

(Council of the Hill of Ares), which like the Gerousia in Sparta, was able to check improper actions of the newly powerful Ecclesia. Solon created a mixed timocratic and democratic system of institutions.

Overall, Solon devised the reforms of 594 BC to avert the political, economic, and moral decline in archaic Athens and gave Athens its first comprehensive code of law. The constitutional reforms eliminated enslavement of Athenians by Athenians, established rules for legal redress against over-reaching aristocratic archons, and assigned political privileges on the basis of productive wealth rather than of noble birth. Some of Solon's reforms failed in the short term, yet he is often credited with having laid the foundations for Athenian democracy.

Democracy under Cleisthenes and Pericles

Even though the Solonian reorganization of the constitution improved the economic position of the Athenian lower classes, it did not eliminate the bitter aristocratic contentions for control of the archonship, the chief executive post. Peisistratos became

Even though the Solonian reorganization of the constitution improved the economic position of the Athenian lower classes, it did not eliminate the bitter aristocratic contentions for control of the archonship, the chief executive post. Peisistratos became tyrant

A tyrant (), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to ...

of Athens three times from 561 BC and remained in power until his death in 527 BC. His sons Hippias and Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; , ; BC) was a Ancient Greek astronomy, Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equinoxes. Hippar ...

succeeded him.["Peisistratus"](_blank)

''Encyclopædia Britannica''.

After the fall of tyranny (510 BC) and before the year 508–507 BC was over, Cleisthenes

Cleisthenes ( ; ), or Clisthenes (), was an ancient Athenian lawgiver credited with reforming the constitution of ancient Athens and setting it on a democratic footing in 508 BC. For these accomplishments, historians refer to him as "the fath ...

proposed a complete reform of the system of government, which later was approved by the popular .["Cleisthenes of Athens"](_blank)

''Encyclopædia Britannica''. by expanding access to power to more citizens. During this period, Athenians first used the word "democracy" ( – "rule by the people") to define their new system of government.[Clarke, 2001, pp. 194–201] In the next generation, Athens entered its Golden Age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the ''Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages of Man, Ages, Gold being the first and the one during wh ...

, becoming a great center of literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

and art

Art is a diverse range of cultural activity centered around ''works'' utilizing creative or imaginative talents, which are expected to evoke a worthwhile experience, generally through an expression of emotional power, conceptual ideas, tec ...

. Greek victories in Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of th ...

(499–449 BC) encouraged the poorest Athenians (who participated in the military campaigns) to demand a greater say in the running of their city. In the late 460s, Ephialtes

Ephialtes (, ''Ephialtēs'') was an ancient Athenian politician and an early leader of the democratic movement there. In the late 460s BC, he oversaw reforms that diminished the power of the Areopagus, a traditional bastion of conservatism, and w ...

and Pericles

Pericles (; ; –429 BC) was a Greek statesman and general during the Golden Age of Athens. He was prominent and influential in Ancient Athenian politics, particularly between the Greco-Persian Wars and the Peloponnesian War, and was acclaimed ...

presided over a radicalization of power that shifted the balance decisively to the poorest sections of society, by passing laws which severely limited the powers of the Council of the Areopagus and allowed thetes (Athenians without wealth) to occupy public office. Pericles became distinguished as the Athenians' greatest democratic leader, even though he has been accused of running a political machine

In the politics of representative democracies, a political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by the use of tangible incentives (such as money or political jobs) and that is characterized by a high degree of leadership c ...

. In the following passage, Thucydides

Thucydides ( ; ; BC) was an Classical Athens, Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts Peloponnesian War, the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been d ...

recorded Pericles, in the funeral oration, describing the Athenian system of rule:

The Athenian democracy of Cleisthenes and Pericles was based on freedom of citizens (through the reforms of Solon) and on equality of citizens () – introduced by Cleisthenes and later expanded by Ephialtes and Pericles. To preserve these principles, the Athenians used lot for selecting officials. Casting lots aimed to ensure that all citizens were "equally" qualified for office, and to avoid any corruption allotment machines were used. Moreover, in most positions chosen by lot, Athenian citizens could not be selected more than once; this rotation in office meant that no-one could build up a power base through staying in a particular position.

The courts formed another important political institution in Athens; they were composed of a large number of

The Athenian democracy of Cleisthenes and Pericles was based on freedom of citizens (through the reforms of Solon) and on equality of citizens () – introduced by Cleisthenes and later expanded by Ephialtes and Pericles. To preserve these principles, the Athenians used lot for selecting officials. Casting lots aimed to ensure that all citizens were "equally" qualified for office, and to avoid any corruption allotment machines were used. Moreover, in most positions chosen by lot, Athenian citizens could not be selected more than once; this rotation in office meant that no-one could build up a power base through staying in a particular position.

The courts formed another important political institution in Athens; they were composed of a large number of juries

A jury is a sworn body of people (jurors) convened to hear evidence, make findings of fact, and render an impartial verdict officially submitted to them by a court, or to set a penalty or judgment. Most trial juries are " petit juries", an ...

with no judge

A judge is a person who wiktionary:preside, presides over court proceedings, either alone or as a part of a judicial panel. In an adversarial system, the judge hears all the witnesses and any other Evidence (law), evidence presented by the barris ...

s, and they were selected by lot on a daily basis from an annual pool, also chosen by lot. The courts had unlimited power to control the other bodies of the government and its political leaders.majority

A majority is more than half of a total; however, the term is commonly used with other meanings, as explained in the "#Related terms, Related terms" section below.

It is a subset of a Set (mathematics), set consisting of more than half of the se ...

vote in the (compare direct democracy

Direct democracy or pure democracy is a form of democracy in which the Election#Electorate, electorate directly decides on policy initiatives, without legislator, elected representatives as proxies, as opposed to the representative democracy m ...

), in which all male citizens could participate (in some cases with a quorum of 6000). The decisions taken in the were executed by the Boule of 500, which had already approved the agenda for the Ecclesia. The Athenian Boule was elected by lot every year

The birth of political philosophy

Within the Athenian democratic environment, many philosophers from all over the Greek world gathered to develop their theories. Socrates

Socrates (; ; – 399 BC) was a Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher from Classical Athens, Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and as among the first moral philosophers of the Ethics, ethical tradition ...

(470–399 BC) was the first to raise the question, further expanded by his pupil Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

(died 348/347), about the relation/position of an individual within a community. Aristotle (384–322 BC) continued the work of his teacher, Plato, and laid the foundations of political philosophy

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and Political legitimacy, legitimacy of political institutions, such as State (polity), states. This field investigates different ...

. The political philosophy developed in Athens was, in the words of Peter Hall, "in a form so complete that hardly added anyone of moment to it for over a millennium". Aristotle systematically analyzed the different systems of rule that the numerous Greek city-states had and divided them into three categories based on how many ruled: the many (democracy/polity), the few (oligarchy/aristocracy), a single person (tyranny, or today: autocracy/monarchy). For Aristotle, the underlying principles of democracy are reflected in his work ''Politics'':

Decline, revival, and criticisms

The Athenian democracy, in its two centuries of life-time, twice voted against its democratic constitution (both times during the crisis at the end of the Pelopponesian War of 431 to 404 BC), establishing first the Four Hundred (in 411 BC) and second Sparta's puppet régime of the Thirty Tyrants The Thirty Tyrants (, ''hoi triákonta týrannoi'') were an oligarchy that briefly ruled Classical Athens, Athens from 404 BC, 404 BCE to 403 BC, 403 BCE. Installed into power by the Sparta, Spartans after the Athenian surrender in the Peloponnesian ...

(in 404 BC). Both votes took place under manipulation and pressure, but democracy was recovered in less than a year in both cases. Reforms following the restoration of democracy after the overthrow of the Thirty Tyrants The Thirty Tyrants (, ''hoi triákonta týrannoi'') were an oligarchy that briefly ruled Classical Athens, Athens from 404 BC, 404 BCE to 403 BC, 403 BCE. Installed into power by the Sparta, Spartans after the Athenian surrender in the Peloponnesian ...

removed most law-making authority from the Assembly and placed it in randomly selected law-making juries known as . Athens restored its democratic constitution again after King Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon (; 382 BC – October 336 BC) was the king (''basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the ...

(reigned 359–336 BC) and later Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

(reigned 336–323 BC) unified Greece, but it was politically overshadowed by the Hellenistic empires. Finally, after the Roman conquest of Greece in 146 BC, Athens was restricted to matters of local administration.

However, democracy in Athens declined not only due to external powers, but due to its citizens, such as Plato and his student Aristotle. Because of their influential works, after the rediscovery of classics

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

during the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

, Sparta's political stability was praised,[Plato, ''Republic''][Paul Cartledge]

"The Socratics' Sparta and Rousseau's"

(seminar notes). . Institute of Historical Research,

University of Cambridge. while the Periclean democracy was described as a system of rule where either the less well-born, the mob (as a collective tyrant), or the poorer classes held power.George Grote

George Grote (; 17 November 1794 – 18 June 1871) was an English political radical and classical historian. He is now best known for his major work, the voluminous ''History of Greece''.

Early life

George Grote was born at Clay Hill near Be ...

from 1846 onwards, did modern political thinkers start to view the Athenian democracy of Pericles positively. In the late 20th century scholars re-examined the Athenian system of rule as a model of empowering citizens and as a "post-modern" example for communities and organizations alike.

Rome

Rome's history has helped preserve the concept of democracy over the centuries. The Romans invented the concept of classics and many works from Ancient Greece were preserved. Additionally, the Roman model of governance inspired many political thinkers over the centuries, and today's modern (representative) democracies imitate more the Roman than the Greek models.

The Roman Republic

Rome was a city-state in

Rome was a city-state in Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

next to powerful neighbors; Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization ( ) was an ancient civilization created by the Etruscans, a people who inhabited Etruria in List of ancient peoples of Italy, ancient Italy, with a common language and culture, and formed a federation of city-states. Af ...

had built city-states throughout central Italy since the 13th century BC and in the south were Greek colonies. Similar to other city-states, Rome was ruled by a king elected by the Assemblies. However, social unrest and the pressure of external threats led in 510 BC the last king to be deposed by a group of aristocrats led by Lucius Junius Brutus

Lucius Junius Brutus (died ) was the semi-legendary founder of the Roman Republic and traditionally one of its two first consuls. Depicted as responsible for the expulsion of his uncle, the Roman king Tarquinius Superbus after the suicide of L ...

.[Livy, 2002, p. 23][Durant, 1942, p. 23] A new constitution was crafted, but the conflict between the ruling families (patricians

The patricians (from ) were originally a group of ruling class families in ancient Rome. The distinction was highly significant in the Roman Kingdom and the early Republic, but its relevance waned after the Conflict of the Orders (494 BC to 287 B ...

) and the rest of the population, the plebeians

In ancient Rome, the plebeians or plebs were the general body of free Roman citizens who were not Patrician (ancient Rome), patricians, as determined by the Capite censi, census, or in other words "commoners". Both classes were hereditary.

Et ...

continued. The plebs were demanding for definite, written, and secular laws. The patrician priests, who were the recorders and interpreters of the statutes, by keeping their records secret used their monopoly against social change. After a long resistance to the new demands, the Senate in 454 BC sent a commission of three patricians to Greece to study and report on the legislation of Solon and other lawmakers.Twelve Tables

The Laws of the Twelve Tables () was the legislation that stood at the foundation of Roman law. Formally promulgated in 449 BC, the Tables consolidated earlier traditions into an enduring set of laws.Crawford, M.H. 'Twelve Tables' in Simon Hornbl ...

and submitted them to the Assembly (which passed them with some changes) and they were displayed in the Forum for all who would and could read. The Twelve Tables recognised certain rights and by the 4th century BC, the plebs were given the right to stand for consulship and other major offices of the state.

The political structure as outlined in the Roman constitution resembled a mixed constitution and its constituent parts were comparable to those of the Spartan constitution: two consuls, embodying the monarchic form; the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, embodying the aristocratic form; and the people through the assemblies. The consul was the highest ranking ordinary magistrate.[Balot, 2009, p. 216] Consuls had power in both civil and military matters. While in the city of Rome, the consuls were the head of the Roman government and they would preside over the Senate and the assemblies. While abroad, each consul would command an army. The Senate passed decrees, which were called and were official advice to a magistrate. However, in practice, it was difficult for a magistrate to ignore the Senate's advice.Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding i ...

writes: "levels were designed so that no one appeared to be excluded from an election and yet all of the clout resided with the leading men".[Liv 1.43.11] Moreover, the unequal weight of votes was making a rare practice for asking the lowest classes for their votes.[

Roman stability, in ]Polybius

Polybius (; , ; ) was a Greek historian of the middle Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , a universal history documenting the rise of Rome in the Mediterranean in the third and second centuries BC. It covered the period of 264–146 ...

' assessment, was owing to the checks each element put on the superiority of any other: a consul at war, for example, required the cooperation of the Senate and the people if he hoped to secure victory and glory, and could not be indifferent to their wishes. This was not to say that the balance was in every way even: Polybius observes that the superiority of the Roman to the Carthaginian constitution (another mixed constitution) at the time of the Hannibalic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of three wars fought between Carthage and Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For 17 years the two states struggled for supremacy, primarily in Ita ...

was an effect of the latter's greater inclination toward democracy than to aristocracy. Moreover, recent attempts to posit for Rome personal freedom in the Greek sense – : living as you like – have fallen on stony ground, since (which was an ideology and way of life in the democratic Athens) was anathema in the Roman eyes. Rome's core values included order, hierarchy, discipline, and obedience. These values were enforced with laws regulating the private life of an individual. The laws were applied in particular to the upper classes, since the upper classes were the source of Roman moral examples.

Rome became the ruler of a great Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

empire. The new provinces brought wealth to Italy, and fortunes were made through mineral concessions and enormous slave run estates. Slaves were imported to Italy and wealthy landowners soon began to buy up and displace the original peasant farmers. By the late 2nd century this led to renewed conflict between the rich and poor and demands from the latter for reform of the constitution. The background of social unease and the inability of the traditional republican constitutions to adapt to the needs of the growing empire led to the rise of a series of over-mighty generals, championing the cause of either the rich or the poor, in the last century BC.

Transition to empire

Over the next few hundred years, various generals would bypass or overthrow the Senate for various reasons, mostly to address perceived injustices, either against themselves or against poorer citizens or soldiers. One of those generals was

Over the next few hundred years, various generals would bypass or overthrow the Senate for various reasons, mostly to address perceived injustices, either against themselves or against poorer citizens or soldiers. One of those generals was Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

, where he marched on Rome and took supreme power over the republic. Caesar's career was cut short by his assassination at Rome in 44 BC by a group of Senators including Marcus Junius Brutus

Marcus Junius Brutus (; ; 85 BC – 23 October 42 BC) was a Roman politician, orator, and the most famous of the assassins of Julius Caesar. After being adopted by a relative, he used the name Quintus Servilius Caepio Brutus, which was reta ...

. In the power vacuum that followed Caesar's assassination, his friend and chief lieutenant, Marcus Antonius

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the ...

, and Caesar's grandnephew Octavian

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in ...

who also was the adopted son of Caesar, rose to prominence. Their combined strength gave the triumvirs absolute power. However, in 31 BC war between the two broke out. The final confrontation occurred on 2 September 31 BC, at the naval Battle of Actium

The Battle of Actium was a naval battle fought between Octavian's maritime fleet, led by Marcus Agrippa, and the combined fleets of both Mark Antony and Cleopatra. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC in the Ionian Sea, near the former R ...

where the fleet of Octavian under the command of Agrippa routed Antony's fleet. Thereafter, there was no one left in the Roman Republic who wanted to, or could stand against Octavian, and the adopted son of Caesar moved to take absolute control. Octavian left the majority of Republican institutions intact, though he influenced everything using personal authority and ultimately controlled the final decisions, having the military might to back up his rule if necessary. By 27 BC the transition, though subtle, disguised, and relying on personal power over the power of offices, was complete. In that year, Octavian offered back all his powers to the Senate, and in a carefully staged way, the Senate refused and titled Octavian – "the revered one". He was always careful to avoid the title of – "king", and instead took on the titles of – "first citizen" and , a title given by Roman troops to their victorious commanders, completing the transition from the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

.

Institutions in the medieval era

Early institutions included:

* The continuations of the early Germanic thing from the

Early institutions included:

* The continuations of the early Germanic thing from the Viking Age

The Viking Age (about ) was the period during the Middle Ages when Norsemen known as Vikings undertook large-scale raiding, colonising, conquest, and trading throughout Europe and reached North America. The Viking Age applies not only to their ...

:

** The Witenagemot

The witan () was the king's council in the Anglo-Saxon government of England from before the 7th century until the 11th century. It comprised important noblemen, including ealdormen, thegns, and bishops. Meetings of the witan were sometimes ...

(folkmoot) of Early Medieval England

Anglo-Saxon England or early medieval England covers the period from the end of Roman imperial rule in Britain in the 5th century until the Norman Conquest in 1066. Compared to modern England, the territory of the Anglo-Saxons stretched nort ...

, councils of advisors to the kings of the petty kingdoms and then that of a unified England before the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, French people, French, Flemish people, Flemish, and Bretons, Breton troops, all led by the Du ...

.

** The Frankish custom of the or ''Camp of Mars''.

** In the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

, in Portuguese, Leonese, Castillian, Aragonese, Catalan and Valencian Valencian can refer to:

* Something related to the Valencian Community ( Valencian Country) in Spain

* Something related to the city of Valencia

* Something related to the province of Valencia in Spain

* Something related to the old Kingdom of ...

customs, (or ) were periodically convened to debate the state of the Realms. The Corts of Catalonia were the first parliament of Europe that officially obtained the power to pass legislation.

** Tynwald

Tynwald (), or more formally, the High Court of Tynwald () or Tynwald Court, is the legislature of the Isle of Man. It consists of two chambers, known as the branches of Tynwald: the directly elected House of Keys and the indirectly chosen Leg ...

, on the Isle of Man

The Isle of Man ( , also ), or Mann ( ), is a self-governing British Crown Dependency in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland. As head of state, Charles III holds the title Lord of Mann and is represented by a Lieutenant Govern ...

, claims to be one of the oldest continuous parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

s in the world, with roots back to the late 9th or 10th century.

** The , the parliament of the Icelandic Commonwealth

The Icelandic Commonwealth, also known as the Icelandic Free State, was the political unit existing in Iceland between the establishment of the Althing () in 930 and the pledge of fealty to the Norwegian king with the Old Covenant in 1262. W ...

, founded in 930. It consisted of the 39, later 55, ; each owner of a ; and each hereditary kept a tight hold on his membership, which could in principle be lent or sold. Thus, for example, when Burnt Njal's stepson wanted to enter it, Njal had to persuade the to enlarge itself so a seat would become available. But as each independent farmer in the country could choose what represented him, the system could be claimed as an early form of democracy. The has run nearly continuously to the present day. The was preceded by less elaborate " things" (assemblies) all over Northern Europe.

** Sicilian Parliament of the kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily (; ; ) was a state that existed in Sicily and the southern Italian peninsula, Italian Peninsula as well as, for a time, in Kingdom of Africa, Northern Africa, from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 until 1816. It was ...

, from 1097, one of the oldest parliaments in the world and the first legislature in the modern sense.

** The '' Thing of all Swedes'', which took place annually at Uppsala

Uppsala ( ; ; archaically spelled ''Upsala'') is the capital of Uppsala County and the List of urban areas in Sweden by population, fourth-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmö. It had 177,074 inhabitants in 2019.

Loc ...

at the end of February or in early March. As in Iceland, the lawspeaker

A lawspeaker or lawman ( Swedish: ''lagman'', Old Swedish: ''laghmaþer'' or ''laghman'', Danish: ''lovsigemand'', Norwegian: ''lagmann'', Icelandic: , Faroese: '' løgmaður'', Finnish: ''laamanni'', ) is a unique Scandinavian legal offic ...

presided over the assemblies, but the Swedish king functioned as a judge. A famous incident took place circa 1018, when King Olof Skötkonung

Olof Skötkonung (; – 1022), sometimes stylized as Olaf the Swede, was King of Sweden, son of Eric the Victorious and, according to Icelandic sources, Sigrid the Haughty. He succeeded his father in c. 995. He stands at the threshold of record ...

wanted to pursue the war against Norway against the will of the people. Þorgnýr the Lawspeaker reminded the king in a long speech that the power resided with the Swedish people and not with the king. When the king heard the din of swords beating the shields in support of Þorgnýr's speech, he gave in. Adam of Bremen wrote that the people used to obey the king only when they thought his suggestions seemed better, although in war his power was absolute.

** The Swiss .

** In Norway:

* The election of Gopala in the Pala Empire

The Pāla Empire was the empire ruled by the Pala dynasty, ("protector" in Sanskrit) a medieval Indian dynasty which ruled the kingdom of Gauda Kingdom, Gauda. The empire was founded with the election of Gopala, Gopāla by the chiefs of Kingdo ...

(8th century).

* The system in early medieval Ireland. Landowners and the masters of a profession or craft were members of a local assembly, known as a . Each met in annual assembly which approved all common policies, declared war or peace on other , and accepted the election of a new "king"; normally during the old king's lifetime, as a tanist

Tanistry is a Gaelic system for passing on titles and lands. In this system the Tanist (; ; ) is the office of heir-apparent, or second-in-command, among the (royal) Gaelic patrilineal dynasties of Ireland, Scotland and Mann, to succeed to ...

. The new king had to be descended within four generations from a previous king, so this usually became, in practice, a hereditary kingship; although some kingships alternated between lines of cousins. About 80 to 100 coexisted at any time throughout Ireland. Each controlled a more or less compact area of land which it could pretty much defend from cattle-raids, and this was divided among its members.

* The Ibadi

Ibadism (, ) is a school of Islam concentrated in Oman established from within the Kharijites. The followers of the Ibadi sect are known as the Ibadis or, as they call themselves, The People of Truth and Integrity ().

Ibadism emerged around 6 ...

tes of Oman

Oman, officially the Sultanate of Oman, is a country located on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia and the Middle East. It shares land borders with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. Oman’s coastline ...

, a minority sect distinct from both Sunni

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam and the largest religious denomination in the world. It holds that Muhammad did not appoint any successor and that his closest companion Abu Bakr () rightfully succeeded him as the caliph of the Mu ...

and Shia

Shia Islam is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that Muhammad designated Ali ibn Abi Talib () as both his political successor (caliph) and as the spiritual leader of the Muslim community (imam). However, his right is understood ...

Muslims, have traditionally chosen their leaders via community-wide elections of qualified candidates starting in the 8th century.[

* The ]guilds

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular territory. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradespeople belonging to a professional association. They so ...

, of economic, social and religious natures, in the later Middle Ages elected officers for yearly terms.

* The city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world throughout history, including cities such as Rome, ...

s (republics) of medieval Italy

The history of Italy in the Middle Ages can be roughly defined as the time between the collapse of the Western Roman Empire and the Italian Renaissance. Late antiquity in Italy lingered on into the 7th century under the Ostrogothic Kingdom and ...

, as Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

and Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

, and similar city-states in Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

, Flanders and the Hanseatic league

The Hanseatic League was a Middle Ages, medieval commercial and defensive network of merchant guilds and market towns in Central Europe, Central and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Growing from a few Northern Germany, North German towns in the ...

had not a modern democratic system but a guild democratic system. The Italian cities in the middle medieval period had "lobbies war" democracies without institutional guarantee systems (a full developed balance of powers). During late medieval and renaissance periods, Venice became an oligarchy and others became ("lordships"). They were, in any case in late medieval times, not nearly as democratic as the Athenian-influenced city-states of Ancient Greece (discussed above), but they served as focal points for early modern democracy.

* , – popular assemblies in Slavic countries. In Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, developed in 1182 into the – the Polish parliament. The was the highest legislature

A legislature (, ) is a deliberative assembly with the legal authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country, nation or city on behalf of the people therein. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial power ...

and judicial authority in the republics of Novgorod

Veliky Novgorod ( ; , ; ), also known simply as Novgorod (), is the largest city and administrative centre of Novgorod Oblast, Russia. It is one of the oldest cities in Russia, being first mentioned in the 9th century. The city lies along the V ...

until 1478 and Pskov

Pskov ( rus, Псков, a=Ru-Псков.oga, p=psˈkof; see also Names of Pskov in different languages, names in other languages) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city in northwestern Russia and the administrative center of Pskov O ...

until 1510.

* The system of the Basque Country in which farmholders of a rural area connected to a particular church would meet to reach decisions on issues affecting the community and to elect representatives to the provincial /.

* The rise of democratic parliaments in England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

and Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

: Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter"), sometimes spelled Magna Charta, is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardin ...

(1215) limiting the authority of the king; first representative parliament (1265). The version of Magna Carta signed by King John implicitly supported what became the English writ of habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a legal procedure invoking the jurisdiction of a court to review the unlawful detention or imprisonment of an individual, and request the individual's custodian (usually a prison official) to ...

, safeguarding individual freedom against unlawful imprisonment with right to appeal. The emergence of petitioning in the 13th century is some of the earliest evidence of this parliament being used as a forum to address the general grievances of ordinary people.

Indigenous peoples of the Americas

Professor of anthropology Jack Weatherford has argued that the ideas leading to the United States Constitution