History Of Avignon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The following is a history of

, Towens and Country of Art and history, Ministry of Culture, consulted on 17 October 2011 In 1960 and 1961 excavations in the northern part of the ''Rocher des Doms'' directed by Sylvain Gagnière uncovered a small anthropomorphic stele (height: 20 cm), which was found in an area of land being reworked. Carved in

The name of the city dates back to around the 6th century BC. The first citation of Avignon (''Aouen(n)ion'') was made by

The name of the city dates back to around the 6th century BC. The first citation of Avignon (''Aouen(n)ion'') was made by

, Avignon official website, consulted on 17 October 2011 Avignon was a simple Greek Emporium founded by

horizon-provence website, consulted on 17 October 2011 It acquired the status of

Although the date of the Christianization of the city is not known with certainty, it is known that the first evangelizers and prelates were within the

Although the date of the Christianization of the city is not known with certainty, it is known that the first evangelizers and prelates were within the

Invasions began and during the inroads of the

Invasions began and during the inroads of the  In September 973

In September 973

At the end of the twelfth century, Avignon declared itself an independent republic, and sided with

Diocese of Avignon, consulted on 17 October 2011 From the fifteenth century onward, the kings of France sought to control Avignon. In 1472, royal favorite Charles de Bourbon, Archbishop of Lyon became Legate, but in 1474 Pope Sixtus appointed della Rovere in his place. This offended

''Historical Bibliography and critique of the French periodical press''

Firmin Didot Frères, Paris, 1866, p. 306, consulted on 17 October 2011

The 20th century saw significant development of urbanization, mainly outside the city walls, and several major projects have emerged. Between 1920 and 1975 the population has almost doubled despite the cession of Le Pontet in 1925 and the

The 20th century saw significant development of urbanization, mainly outside the city walls, and several major projects have emerged. Between 1920 and 1975 the population has almost doubled despite the cession of Le Pontet in 1925 and the

Volume 1Volume 2

* * * * * * {{refend

Avignon

Avignon (, , ; or , ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the Communes of France, commune had a ...

, France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

.

Prehistory

The site of Avignon has been occupied since the Neolithic period as shown by excavations at ''Rocher des Doms'' and the ''Balance'' district.''Tell me about Avignon'', Towens and Country of Art and history, Ministry of Culture, consulted on 17 October 2011 In 1960 and 1961 excavations in the northern part of the ''Rocher des Doms'' directed by Sylvain Gagnière uncovered a small anthropomorphic stele (height: 20 cm), which was found in an area of land being reworked. Carved in

Burdigalian

The Burdigalian is, in the geologic timescale, an age (geology), age or stage (stratigraphy), stage in the early Miocene. It spans the time between 20.43 ± 0.05 annum, Ma and 15.97 ± 0.05 Ma (million years ago). Preceded by the Aquitanian (sta ...

sandstone, it has the shape of a "tombstone" with its face engraved with a highly stylized human figure with no mouth and whose eyes are marked by small cavities. On the bottom, shifted slightly to the right is a deep indentation with eight radiating lines forming a solar representation - a unique discovery for this type of stele.

Compared to other similar solar figures this stele representing the "first Avignonnais" and comes from the time period between the Copper Age

The Chalcolithic ( ) (also called the Copper Age and Eneolithic) was an archaeological period characterized by the increasing use of smelted copper. It followed the Neolithic and preceded the Bronze Age. It occurred at different periods in dif ...

and the Early Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

which is called the ''southern Chalcolithic''.

This was confirmed by other findings made in this excavation near the large water reservoir on top of the rock where two polished greenstone axes were discovered, a lithic industry characteristic of "shepherds of the plateaux". There were also some Chalcolithic objects for adornment and an abundance of Hallstatt

Hallstatt () is a small town in the district of Gmunden District, Gmunden, in the Austrian state of Upper Austria. Situated between the southwestern shore of Hallstätter See and the steep slopes of the Dachstein massif, the town lies in the Sa ...

pottery shards which could have been native or imported (Ionia

Ionia ( ) was an ancient region encompassing the central part of the western coast of Anatolia. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionians who ...

n or Phocaea

Phocaea or Phokaia (Ancient Greek language, Ancient Greek: Φώκαια, ''Phókaia''; modern-day Foça in Turkey) was an ancient Ionian Ancient Greece, Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia. Colonies in antiquity, Greek colonists from Phoc ...

n).

Antiquity

The name of the city dates back to around the 6th century BC. The first citation of Avignon (''Aouen(n)ion'') was made by

The name of the city dates back to around the 6th century BC. The first citation of Avignon (''Aouen(n)ion'') was made by Artemidorus of Ephesus

Artemidorus Daldianus () or Ephesius was a professional diviner and dream interpreter who lived in the 2nd century AD. He is known from an extant five-volume Greek work, the ''Oneirocritica'' or ''Oneirokritikon'' ()."Artemidorus Daldianus" in ' ...

. Although his book, ''The Journey'', is lost it is known from the abstract by Marcian of Heraclea

Marcian of Heraclea (, ''Markianòs Hērakleṓtēs''; ; fl. century AD) was a minor Greek geographer from Heraclea Pontica in Late Antiquity.

His known works are:

*'' Periplus of the Outer Sea'' (Greek: ''Περιπλοισ τησ εΞω Θ� ...

and ''The Ethnics'', a dictionary of names of cities by Stephanus of Byzantium

Stephanus or Stephen of Byzantium (; , ''Stéphanos Byzántios''; centuryAD) was a Byzantine grammarian and the author of an important geographical dictionary entitled ''Ethnica'' (). Only meagre fragments of the dictionary survive, but the epit ...

based on that book. He said: "The City of Massalia (Marseille), near the Rhone, the ethnic name (name from the inhabitants) is Avenionsios (Avenionensis) according to the local name (in Latin) and Auenionitès according to the Greek expression". This name has two interpretations: "city of violent wind" or, more likely, "lord of the river". The Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foot ...

tribes named it ''Auoention'' around the beginning of the Christian Era. Other sources trace its origin to the Gallic ''mignon'' ("marshes") and the Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foot ...

definitive article.History of the origin of the name, Avignon official website, consulted on 17 October 2011 Avignon was a simple Greek Emporium founded by

Phocaea

Phocaea or Phokaia (Ancient Greek language, Ancient Greek: Φώκαια, ''Phókaia''; modern-day Foça in Turkey) was an ancient Ionian Ancient Greece, Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia. Colonies in antiquity, Greek colonists from Phoc ...

ns from Marseille around 539 BC. It was in the 4th century BC that the Massaliotes (people from Marseilles) began to sign treaties of alliance with some cities in the Rhone valley including Avignon and Cavaillon. A century later Avignon was part of the "region of Massaliotes" or "country of Massalia".

Fortified on its rock, the city later became and long remained the capital of the Cavares

The Cavarī or Cavarēs (Gaulish: *''Cauaroi'', 'the heroes, champions, mighty men') were a Gallic tribe dwelling in the western part of modern Vaucluse, around the present-day cities of Avignon, Orange and Cavaillon, during the Roman period. Th ...

. With the arrival of the Roman legions in 120 BC. the Cavares, allies with the Massaliotes, became Roman. Under the domination of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, ''Aouenion'' became ''Avennio'' and was now part of Gallia Narbonensis

Gallia Narbonensis (Latin for "Gaul of Narbonne", from its chief settlement) was a Roman province located in Occitania and Provence, in Southern France. It was also known as Provincia Nostra ("Our Province"), because it was the first ...

(118 BC.), the first Transalpine province of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

. Very little from this period remains (a few fragments of the forum

Forum or The Forum may refer to:

Common uses

*Forum (legal), designated space for public expression in the United States

*Forum (Roman), open public space within a Roman city

**Roman Forum, most famous example

* Internet forum, discussion board ...

near Rue Molière). It later became part of the ''2nd Viennoise''. Avignon remained a "federated city" with Marseille until the conquest of Marseille by Trebonius

Gaius Trebonius (c. 92 BC – January 43 BC) was a military commander and politician of the late Roman Republic, who became suffect consul in 45 BC. He was an associate of Julius Caesar, having served as his legate and having fought on his side du ...

and Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus

Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus (27 April 81 BC – September 43 BC) was a Ancient Rome, Roman general and politician of the crisis of the Roman Republic, late republican period and one of the leading instigators of Julius Caesar's Assassination ...

, Caesar's lieutenants. It became a city of Roman law

Roman law is the law, legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (), to the (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Justinian I.

Roman law also den ...

in 49 BC.''The Origins of Avignon''horizon-provence website, consulted on 17 October 2011 It acquired the status of

Roman colony

A Roman (: ) was originally a settlement of Roman citizens, establishing a Roman outpost in federated or conquered territory, for the purpose of securing it. Eventually, however, the term came to denote the highest status of a Roman city. It ...

in 43 BC. Pomponius Mela

Pomponius Mela, who wrote around AD 43, was the earliest known Roman geographer. He was born at the end of the 1st century BC in Tingentera (now Algeciras) and died AD 45.

His short work (''De situ orbis libri III.'') remained in use nea ...

placed it among the most flourishing cities of the province.

Over the years 121 and 122 the Emperor Hadrian

Hadrian ( ; ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. Hadrian was born in Italica, close to modern Seville in Spain, an Italic peoples, Italic settlement in Hispania Baetica; his branch of the Aelia gens, Aelia '' ...

stayed in the Province

A province is an administrative division within a country or sovereign state, state. The term derives from the ancient Roman , which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire, Roman Empire's territorial possessions ou ...

where he visited Vaison

Vaison-la-Romaine (; ) is a town in the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region in southeastern France.

Vaison-la-Romaine is famous for its rich Roman ruins and mediaeval town and cathedral. It is also unusual in the way th ...

, Orange

Orange most often refers to:

*Orange (fruit), the fruit of the tree species '' Citrus'' × ''sinensis''

** Orange blossom, its fragrant flower

** Orange juice

*Orange (colour), the color of an orange fruit, occurs between red and yellow in the vi ...

, Apt, and Avignon. He gave Avignon the status of a Roman colony: "Colonia Julia Hadriana Avenniensis" and its citizens were enrolled in the ''tribu''.

Following the passage of Maximian

Maximian (; ), nicknamed Herculius, was Roman emperor from 286 to 305. He was ''Caesar (title), Caesar'' from 285 to 286, then ''Augustus (title), Augustus'' from 286 to 305. He shared the latter title with his co-emperor and superior, Diocleti ...

, who was fighting the Bagaudes, the Gallic peasants revolted. The first wooden bridge was built over the Rhone linking Avignon to the right bank. It has been dated by dendrochronology

Dendrochronology (or tree-ring dating) is the scientific method of chronological dating, dating tree rings (also called growth rings) to the exact year they were formed in a tree. As well as dating them, this can give data for dendroclimatology, ...

to the year 290. In the 3rd century there was a small Christian community outside the walls around what was to become the Abbey of Saint-Ruf.

Christianity

Although the date of the Christianization of the city is not known with certainty, it is known that the first evangelizers and prelates were within the

Although the date of the Christianization of the city is not known with certainty, it is known that the first evangelizers and prelates were within the hagiographic

A hagiography (; ) is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader, as well as, by extension, an wiktionary:adulatory, adulatory and idealized biography of a preacher, priest, founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religi ...

tradition which is attested by the participation of ''Nectarius'', the first historical Bishop of Avignon

The Archdiocese of Avignon (Latin: ''Archidioecesis Avenionensis''; French: ''Archidiocèse d'Avignon'') is a Latin archdiocese of the Catholic Church in France. The diocese exercises jurisdiction over the territory embraced by the department ...

on 29 November 439, in the regional council in the Cathedral of Riez assisted by the 13 bishops of the three provinces of Arles.

The memory of St. Eucherius still clings to three vast caves near the village of Beaumont where, it is said, the people of Lyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of the French Alps, southeast of Paris, north of Marseille, southwest of Geneva, Switzerland, north ...

had to go in search of him in 434 when they sought him to make him their archbishop

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdi ...

.

In November 441 Nectarius of Avignon, accompanied by his deacon Fontidius, participated in the Council of Orange convened and chaired by Hilary of Arles

Hilary of Arles, also known by his Latin name Hilarius (c. 403–449), was a bishop of Arles in Southern France. He is venerated as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church and Roman Catholic Church, with 5 May being his feast day.

Life

In his e ...

where the Council Fathers defined the right of asylum. In the following year, together with his assistants Fonteius and Saturninus, he was at the first Council of Vaison

The Council of Vaison refers to two separate synods consisting of officials and theologians of the Catholic Church which were held in or near to the Avignon commune of Vaison, France. The first was held in 442 and the second in 529.

First meetin ...

with 17 bishops representing the Seven Provinces. He died in 455.

Early Middle Ages

Goths

The Goths were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe. They were first reported by Graeco-Roman authors in the 3rd century AD, living north of the Danube in what is ...

it was heavily damaged. In 472 Avignon was sacked by the Burgundians

The Burgundians were an early Germanic peoples, Germanic tribe or group of tribes. They appeared east in the middle Rhine region in the third century AD, and were later moved west into the Roman Empire, in Roman Gaul, Gaul. In the first and seco ...

and replenished by the Patiens, from the city of Lyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of the French Alps, southeast of Paris, north of Marseille, southwest of Geneva, Switzerland, north ...

, who sent them wheat.

In 500 Clovis I

Clovis (; reconstructed Old Frankish, Frankish: ; – 27 November 511) was the first List of Frankish kings, king of the Franks to unite all of the Franks under one ruler, changing the form of leadership from a group of petty kings to rule by a ...

, King of the Franks

file:Frankish arms.JPG, Aristocratic Frankish burial items from the Merovingian dynasty

The Franks ( or ; ; ) were originally a group of Germanic peoples who lived near the Rhine river, Rhine-river military border of Germania Inferior, which wa ...

, attacked Gundobad

Gundobad (; ; 452 – 516) was King of the Burgundians (473–516), succeeding his father Gundioc of Burgundy. Previous to this, he had been a patrician of the moribund Western Roman Empire in 472–473, three years before its collapse, suc ...

, King of the Burgundians

The Burgundians were an early Germanic peoples, Germanic tribe or group of tribes. They appeared east in the middle Rhine region in the third century AD, and were later moved west into the Roman Empire, in Roman Gaul, Gaul. In the first and seco ...

who was accused of the murder of the father of his wife Clotilde

Clotilde ( 474 – 3 June 545 in Burgundy, France) (also known as Clotilda (Fr.), Chlothilde (Ger.) Chlothieldis, Chlotichilda, Clodechildis, Croctild, Crote-hild, Hlotild, Rhotild, and many other forms), is a saint and was a Queen of the Fran ...

. Beaten, Gondebaud left Lyon and took refuge in Avignon with Clovis besieging it. Gregory of Tours

Gregory of Tours (born ; 30 November – 17 November 594 AD) was a Gallo-Roman historian and Bishop of Tours during the Merovingian period and is known as the "father of French history". He was a prelate in the Merovingian kingdom, encom ...

reported that the Frankish king devastated the fields, cut down the vines and olive trees, and destroyed the orchards. The Burgundian was saved by the intervention of the Roman General Aredius. He had called him to his aid against the "Frankish barbarians" who ruined the countryside.

In 536 Avignon, following the fate of Provence, was ceded to the Merovingians

The Merovingian dynasty () was the ruling family of the Franks from around the middle of the 5th century until Pepin the Short in 751. They first appear as "Kings of the Franks" in the Roman army of northern Gaul. By 509 they had united all the ...

by Vitiges

Vitiges (also known as Vitigis, Vitigo, Witiges or Wittigis, and in Old Norse as Vigo) (died 542) was king of Ostrogothic Italy from 536 to 540. He succeeded to the throne of Italy in the early stages of the Gothic War of 535–554, as Belisa ...

, the new king of the Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths () were a Roman-era Germanic peoples, Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Goths, Gothic kingdoms within the Western Roman Empire, drawing upon the large Gothic populatio ...

. Chlothar I

Chlothar I, sometime called "the Old" (French: le Vieux), (died December 561) also anglicised as Clotaire from the original French version, was a king of the Franks of the Merovingian dynasty and one of the four sons of Clovis I.

With his eldes ...

annexed Avignon, Orange, Carpentras, and Gap; Childebert I

Childebert I ( 496 – 13 December 558) was a Frankish King of the Merovingian dynasty, as third of the four sons of Clovis I who shared the kingdom of the Franks upon their father's death in 511. He was one of the sons of Saint Clo ...

took Arles and Marseilles; Theudebert I

Theudebert I () (–548) was the Merovingian king of Austrasia from 533 to his death in 548. He was the son of Theuderic I and the father of Theudebald.

Sources

Most of what we know about Theudebert comes from the ''Histories'' or ''History of ...

took Aix

Aix or AIX may refer to:

Computing

* AIX, a line of IBM computer operating systems

*Alternate index, for an IBM Virtual Storage Access Method key-sequenced data set

* Athens Internet Exchange, a European Internet exchange point

Places Belg ...

, Apt, Digne

Digne-les-Bains (; Occitan: ''Dinha dei Banhs''), or simply and historically Digne (''Dinha'' in the classical norm or ''Digno'' in the Mistralian norm), is the prefecture of the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte ...

, and Glandevès. The Emperor Justinian I

Justinian I (, ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was Roman emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign was marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovatio imperii'', or "restoration of the Empire". This ambition was ...

at Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

approved the division.

Despite all the invasions, intellectual life continued to flourish on the banks of the Rhône. Gregory of Tours

Gregory of Tours (born ; 30 November – 17 November 594 AD) was a Gallo-Roman historian and Bishop of Tours during the Merovingian period and is known as the "father of French history". He was a prelate in the Merovingian kingdom, encom ...

noted that after the death of Bishop Antoninus in 561 the Parisian Father Dommole refused the bishopric of Avignon after Chlothar I

Chlothar I, sometime called "the Old" (French: le Vieux), (died December 561) also anglicised as Clotaire from the original French version, was a king of the Franks of the Merovingian dynasty and one of the four sons of Clovis I.

With his eldes ...

convinced him that it would be ridiculous "in the middle of tired senators, sophists, and philosophical judges"

St. Magnus was a Gallo-Roman

Gallo-Roman culture was a consequence of the Romanization (cultural), Romanization of Gauls under the rule of the Roman Empire in Roman Gaul. It was characterized by the Gaulish adoption or adaptation of Roman culture, Roman culture, language ...

senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or Legislative chamber, chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the Ancient Rome, ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior ...

who became a monk

A monk (; from , ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a man who is a member of a religious order and lives in a monastery. A monk usually lives his life in prayer and contemplation. The concept is ancient and can be seen in many reli ...

and then bishop of the city. His son, St. Agricol (Agricolus), bishop between 650 and 700, is the patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, Eastern Orthodoxy or Oriental Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, fa ...

of Avignon.

The 7th and 8th centuries were the darkest period in the history of Avignon. The city became the prey of the Franks

file:Frankish arms.JPG, Aristocratic Frankish burial items from the Merovingian dynasty

The Franks ( or ; ; ) were originally a group of Germanic peoples who lived near the Rhine river, Rhine-river military border of Germania Inferior, which wa ...

under Theuderic II

Theuderic II (also spelled Theuderich, Theoderic or Theodoric; in French, ''Thierry'') ( 587–613), king of Burgundy (595–613) and Austrasia (612–613), was the second son of Childebert II. At his father's death in 595, he received Guntram's ...

, King of Austrasia

Austrasia was the northeastern kingdom within the core of the Francia, Frankish Empire during the Early Middle Ages, centring on the Meuse, Middle Rhine and the Moselle rivers. It included the original Frankish-ruled territories within what had ...

in 612. The Council of Chalon-sur-Saône

Chalon-sur-Saône (, literally ''Chalon on Saône'') is a city in the Saône-et-Loire Departments of France, department in the Regions of France, region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté in eastern France.

It is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefectu ...

in 650 was the last to indicate the Episcopal participation of the Provence dioceses. In Avignon there would be no bishop for 205 years with the last known holder being Agricola

Agricola, the Latin word for farmer, may also refer to:

People Cognomen or given name

:''In chronological order''

* Gnaeus Julius Agricola (40–93), Roman governor of Britannia (AD 77–85)

* Sextus Calpurnius Agricola, Roman governor of the m ...

.

In 734 it fell into the hands of the Saracens

file:Erhard Reuwich Sarazenen 1486.png, upright 1.5, Late 15th-century History of Germany, German woodcut depicting Saracens

''Saracen'' ( ) was a term used both in Greek language, Greek and Latin writings between the 5th and 15th centuries to ...

, and it was destroyed in 737 by the Franks

file:Frankish arms.JPG, Aristocratic Frankish burial items from the Merovingian dynasty

The Franks ( or ; ; ) were originally a group of Germanic peoples who lived near the Rhine river, Rhine-river military border of Germania Inferior, which wa ...

under Charles Martel

Charles Martel (; – 22 October 741), ''Martel'' being a sobriquet in Old French for "The Hammer", was a Franks, Frankish political and military leader who, as Duke and Prince of the Franks and Mayor of the Palace, was the de facto ruler of ...

for having sided with the Saracens against him.

A centralized government was put in place and, in 879, the bishop of Avignon, Ratfred, with other Provençal colleagues, went to the Synod of Mantaille in Viennois where Boso was elected King of Provence after the death of Louis the Stammerer

Louis the Stammerer (; 1 November 846 – 10 April 879) was the king of Aquitaine and later the king of West Francia. He was the eldest son of Emperor Charles the Bald and Ermentrud ...

.

The Rhône

The Rhône ( , ; Occitan language, Occitan: ''Ròse''; Franco-Provençal, Arpitan: ''Rôno'') is a major river in France and Switzerland, rising in the Alps and flowing west and south through Lake Geneva and Southeastern France before dischargi ...

could again be crossed since in 890 part of the ancient bridge of Avignon was restored at the pier No. 14 near Villeneuve. In that same year Louis

Louis may refer to:

People

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

Other uses

* Louis (coin), a French coin

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

...

, the son of Boson, succeeded his father. His election took place in the Synod of Varennes near Macon. Thibert, who was his most effective supporter, became Count of Apt. In 896 Thibert acted as plenipotentiary of the king at Avignon, Arles, and Marseille with the title of "Governor-General of all the counties of Arles and Provence". Two years later, at his request, King Louis donated Bédarrides

Bédarrides (; Provençal: ''Bedarrida'') is a commune in the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region in southeastern France.

Name

The settlement is attested as ''villa Betorrida'' in 814, ''Biturrita'' in 898, ''Bistur ...

to the priest Rigmond d'Avignon.

On 19 October 907 King Louis the Blind

Louis the Blind ( – 5 June 928) was king in Provence and Lower Burgundy from 890 to 928, and also king of Italy from 900 to 905, and also the emperor between 901 and 905, styled as Louis III. His father was king Boso, from the Bosonid family ...

became emperor and restored an island in the Rhone to Remigius, Bishop of Avignon. This charter is the first mention of a cathedral dedicated to Mary.

After the capture and the execution of his cousin, Louis III, who had been exiled to Italy in 905, Hugh of Arles

Hugh of Italy ( 880/885 – April 10, 948), known as Hugh of Arles or Hugh of Provence, was the king of Italy from 926 until 947, and regent in Lower Burgundy and Provence from 911 to 933. He belonged to the Bosonid family. During his reign in ...

became regent and personal advisor to King Louis. He exercised most of the powers of the king of Provence and in 911, when Louis III gave him the titles of Duke of Provence and Marquis of the Viennois, he left Vienne Vienne may refer to:

Places

*Vienne (department), a department of France named after the river Vienne

*Vienne, Isère, a city in the French department of Isère

* Vienne-en-Arthies, a village in the French department of Val-d'Oise

* Vienne-en-Bessi ...

and moved to Arles which was the original seat of his family and which now was the new capital of Provence.

On 2 May 916 Louis the Blind restored the churches of Saint-Ruf and Saint-Géniès to the diocese of Avignon

The Archdiocese of Avignon (Latin: ''Archidioecesis Avenionensis''; French: ''Archidiocèse d'Avignon'') is a Latin archdiocese of the Catholic Church in France. The diocese exercises jurisdiction over the territory embraced by the department ...

. On the same day Bishop Fulcherius attested in favour of his canons and for the two churches of Notre-Dame and Saint-Étienne to form a cathedral.

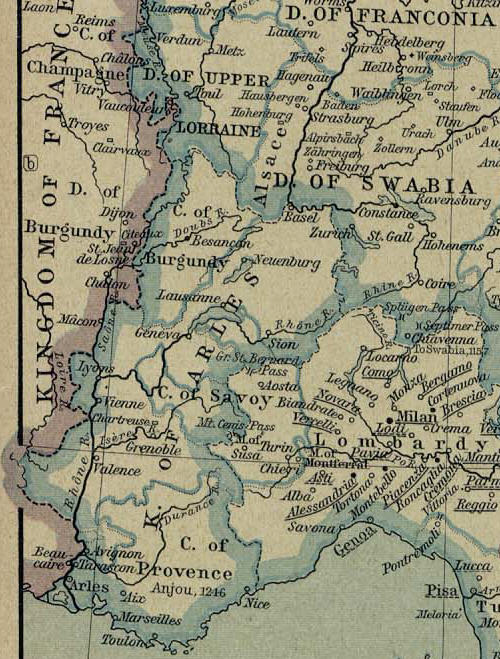

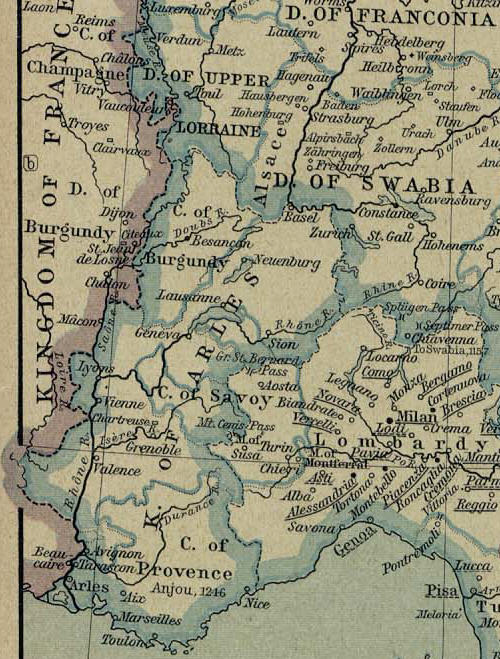

A political event of importance took place in 932 with the reunion of the kingdom of Provence with Upper Burgundy. This union formed the Kingdom of Burgundy

Kingdom of Burgundy was a name given to various successive Monarchy, kingdoms centered in the historical region of Burgundy during the Middle Ages. The heartland of historical Burgundy correlates with the border area between France and Switze ...

in which Avignon was one of the largest cities.

At the end of the 9th century, Muslim Spain installed a military base in Fraxinet

Fraxinetum or Fraxinet ( or , from Latin ''fraxinus'': "ash tree", ''fraxinetum'': "ash forest") was the site of a Muslim stronghold at the centre of a frontier state in Provence between about 887 and 972. It is identified with modern La Garde-Fre ...

since they had led the plundering expeditions in the Alps throughout the 10th century.

During the night of 21 to 22 July 972 the Muslims took dom Mayeul, the Abbot of Cluny who was returning from Rome, prisoner. They asked for one livre

Livre may refer to:

Currency

* French livre, one of a number of obsolete units of currency of France

* Livre tournois, one particular obsolete unit of currency of France

* Livre parisis, another particular obsolete unit of currency of France

* Fre ...

for each of them which came to 1,000 livres, a huge sum, which was paid to them quickly. Maïeul was released in mid-August and returned to Cluny

Cluny () is a commune in the eastern French department of Saône-et-Loire, in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. It is northwest of Mâcon.

The town grew up around the Benedictine Abbey of Cluny, founded by Duke William I of Aquitaine in ...

in September.

In September 973

In September 973 William I of Provence

William I ( 950 – after 29 August 993), called the Liberator, was Count of Provence from 968 to his abdication. In 975 or 979, he took the title of ''marchio'' or margrave. He is often considered the founder of the county of Provence. He and his ...

and his brother Rotbold, sons of the Count of Avignon, Boso II, mobilized all the nobles of Provence on behalf of dom Maïeul. With the help of Ardouin, Marquis of Turin

Turin ( , ; ; , then ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The city is main ...

, and after two weeks of siege, Provençal troops chased the Saracens

file:Erhard Reuwich Sarazenen 1486.png, upright 1.5, Late 15th-century History of Germany, German woodcut depicting Saracens

''Saracen'' ( ) was a term used both in Greek language, Greek and Latin writings between the 5th and 15th centuries to ...

from their hideouts in Fraxinet and Ramatuelle

Ramatuelle (; Provençal: ''Ramatuela'') is a commune in the southeastern French department of Var.

History

Ramatuelle lies near St-Tropez, Sainte-Maxime and Gassin. It was built on a hill to defend itself against enemies. The town was known ...

as well as those at Peirimpi near Noyers in the Jabron valley. William and Roubaud earned their title of Counts of Provence. William had his seat at Avignon and Roubaud at Arles.

In 976 while Bermond, brother-in-law of Eyric was appointed Viscount of Avignon by King Conrad the Peaceful on 1 April, the Cartulary of Notre-Dame des Doms in Avignon says that Bishop Landry restored rights that had been unjustly appropriated to the canons of Saint-Étienne. He gave them a mill and two houses he built for them on the site of the current Trouillas Tower at the papal palace. In 980 these canons were constituted in a canonical chapter by Bishop Garnier.

In 994 Dom Maïeul arrived in Avignon where his friend William the Liberator was dying. He assisted in his last moments on the island facing the city (the Île de la Barthelasse) on the Rhone. The Count had as successor the son he had by his second wife Alix. He would reign jointly with his uncle Rotbold under the name William II. In the face of County and episcopal power, the town of Avignon organized itself. Towards the year 1000 there was already a proconsul Béranger with his wife Gilberte who are known to have founded an abbey at "Castrum Caneto".

In 1032 when Conrad II

Conrad II (, – 4 June 1039), also known as and , was the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire from 1027 until his death in 1039. The first of a succession of four Salian emperors, who reigned for one century until 1125, Conrad ruled the kingdom ...

inherited the Kingdom of Burgundy

Kingdom of Burgundy was a name given to various successive Monarchy, kingdoms centered in the historical region of Burgundy during the Middle Ages. The heartland of historical Burgundy correlates with the border area between France and Switze ...

, Avignon was attached to the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

. The Rhone was now a border that could only be crossed on the old bridge at Avignon. Some Avignon people still use the term "Empire Land" to describe the Avignon side, and "Kingdom Land" to designate the Villeneuve side to the west which was in the possession of the King of France.

Late Middle Ages

After the division of the empire ofCharlemagne

Charlemagne ( ; 2 April 748 – 28 January 814) was List of Frankish kings, King of the Franks from 768, List of kings of the Lombards, King of the Lombards from 774, and Holy Roman Emperor, Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian ...

, Avignon came within the Kingdom of Burgundy, and was owned jointly by the Count of Provence

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , , "little star", is a Typography, typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a star (heraldry), heraldic star.

Computer scientists and Mathematici ...

and the Count of Toulouse

The count of Toulouse (, ) was the ruler of Toulouse during the 8th to 13th centuries. Originating as vassals of the Frankish kings,

the hereditary counts ruled the city of Toulouse and its surrounding county from the late 9th century until 12 ...

. From 1060, the Count of Forcalquier

The County of Forcalquier was a large medieval county in the region of Provence in the Kingdom of Arles, then part of the Holy Roman Empire. It was named after the fortress around which it grew, Forcalquier.

The earliest mention of a castle at Fo ...

also had nominal overlordship, until these rights were resigned to the local Bishops and Consuls in 1135.

With the German rulers at a distance, Avignon set up an autonomous administration with the creation of a consulat in 1129, two years before its neighbour Arles.

In 1209 the Council of Avignon

Council of Avignon may refer to one of a number of councils of the Roman Catholic Church which were held in Avignon in France. The first reported council met in the 11th century and the final council on record was in the mid-19th century.

Eleven ...

ordered a second excommunication for Raymond VI of Toulouse

Raymond VI (; 27 October 1156 – 2 August 1222) was Count of Toulouse and Marquis of Provence from 1194 to 1222. He was also Count of Melgueil (as Raymond IV) from 1173 to 1190.

Early life

Raymond was born at Saint-Gilles, Gard, the son of ...

.Chronology of the catharsAt the end of the twelfth century, Avignon declared itself an independent republic, and sided with

Raymond VII of Toulouse

Raymond VII (July 1197 – 27 September 1249) was Count of Toulouse, Duke of Narbonne and Marquis of Provence from 1222 until his death.

Family and marriages

Raymond was born at the Château de Beaucaire, the son of Raymond VI of Toulouse a ...

during the Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade (), also known as the Cathar Crusade (1209–1229), was a military and ideological campaign initiated by Pope Innocent III to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc, what is now southern France. The Crusade was prosecuted pri ...

. In 1226, the citizens refused to open the gates of Avignon to King Louis VIII of France

Louis VIII (5 September 1187 8 November 1226), nicknamed The Lion (), was King of France from 1223 to 1226. As a prince, he invaded Kingdom of England, England on 21 May 1216 and was Excommunication in the Catholic Church, excommunicated by a ...

and the papal legate. They besieged the city for three months (10 June-12 September). Avignon was captured and forced to pull down its city walls

A defensive wall is a fortification usually used to protect a city, town or other settlement from potential aggressors. The walls can range from simple palisades or earthworks to extensive military fortifications such as curtain walls with to ...

and fill up its moat.

At the end of September, a few days after the surrender of the city to the troops of King Louis VIII, Avignon experienced severe flooding.

In 1249 the city again declared itself a republic on the death of Raymond VII, his heirs being on a crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

.

On 7 May 1251, however, the city was forced to submit to two younger brothers of King Louis IX

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), also known as Saint Louis, was King of France from 1226 until his death in 1270. He is widely recognized as the most distinguished of the Direct Capetians. Following the death of his father, Louis ...

, Alphonse of Poitiers

Alphonse (11 November 122021 August 1271) was the Count of Poitou from 1225 and Count of Toulouse (as such called Alphonse II) from 1249. As count of Toulouse, he also governed the Marquisate of Provence.

Birth and early life

Born at Poissy, A ...

and Charles of Anjou (Charles I of Naples

Charles I (early 1226/12277 January 1285), commonly called Charles of Anjou or Charles d'Anjou, was King of Sicily from 1266 to 1285. He was a member of the royal Capetian dynasty and the founder of the House of Anjou-Sicily. Between 1246 and ...

). They were heirs through the female line of the Marquis and Count of Provence

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , , "little star", is a Typography, typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a star (heraldry), heraldic star.

Computer scientists and Mathematici ...

, and thus co-lords of the city. After the death of Alphonse in 1271, Philip III of France

Philip III (1 May 1245 – 5 October 1285), called the Bold (), was King of France from 1270 until his death in 1285. His father, Louis IX, died in Tunis during the Eighth Crusade. Philip, who was accompanying him, returned to France and wa ...

inherited his share of Avignon and passed it to his son Philip the Fair

Philip IV (April–June 1268 – 29 November 1314), called Philip the Fair (), was King of France from 1285 to 1314. By virtue of his marriage with Joan I of Navarre, he was also King of Navarre and Count of Champagne as Philip I from ...

in 1285. It passed in turn in 1290 to Charles II of Naples

Charles II, also known as Charles the Lame (; ; 1254 – 5 May 1309), was King of Naples, Count of Provence and Forcalquier (1285–1309), Prince of Achaea (1285–1289), and Count of Anjou and Maine (1285–1290); he also was King of Albania ( ...

, who thereafter remained the sole lord of the entire city.

The University of Avignon

A university () is an educational institution, institution of tertiary education and research which awards academic degrees in several Discipline (academia), academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase , which roughly ...

was founded by Pope Boniface VIII

Pope Boniface VIII (; born Benedetto Caetani; – 11 October 1303) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 December 1294 until his death in 1303. The Caetani, Caetani family was of baronial origin with connections t ...

in 1303 and was famed as a seat of legal studies, flourishing until the French Revolution (1792).

Avignon papacy

In 1309 the city, still part of theKingdom of Arles

The Kingdom of Burgundy, known from the 12th century as the Kingdom of Arles, was a realm established in 933 by the merger of the kingdoms of Upper and Lower Burgundy under King Rudolf II. It was incorporated into the Holy Roman Empire in 1033 ...

(as the Kingdom of Burgundy was known by then), was chosen by Pope Clement V

Pope Clement V (; – 20 April 1314), born Raymond Bertrand de Got (also occasionally spelled ''de Guoth'' and ''de Goth''), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 5 June 1305 to his death, in April 1314. He is reme ...

as his residence at the time of the Council of Vienne

The Council of Vienne was the fifteenth ecumenical council of the Catholic Church and met between 1311 and 1312 in Vienne, France. This occurred during the Avignon Papacy and was the only ecumenical council to be held in the Kingdom of France ...

and, from 9 March 1309 until 13 January 1377, Avignon, rather than Rome, was the seat of the Papacy. At the time the city and its surroundings (the Comtat Venaissin

The (; ; 'County of Venaissin'), often called the for short, was a part of the Papal States from 1274 to 1791, in what is now the region of Southern France.

The region was an enclave within the Kingdom of France, comprising the area aroun ...

) were ruled by the kings of Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

of the House of Anjou

Angevin or House of Anjou may refer to:

*County of Anjou or Duchy of Anjou, a historical county, and later Duchy, in France

**Angevin (language), the traditional langue d'oïl spoken in Anjou

**Counts and Dukes of Anjou

*House of Ingelger, a Franki ...

. The French King Philip the Fair

Philip IV (April–June 1268 – 29 November 1314), called Philip the Fair (), was King of France from 1285 to 1314. By virtue of his marriage with Joan I of Navarre, he was also King of Navarre and Count of Champagne as Philip I from ...

, who had inherited from his father all the rights of Alphonse de Poitiers (the last Count of Toulouse

The count of Toulouse (, ) was the ruler of Toulouse during the 8th to 13th centuries. Originating as vassals of the Frankish kings,

the hereditary counts ruled the city of Toulouse and its surrounding county from the late 9th century until 12 ...

), made them over to Charles II, King of Naples

The following is a list of rulers of the Kingdom of Naples, from its first Sicilian Vespers, separation from the Kingdom of Sicily to its merger with the same into the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

Kingdom of Naples (1282–1501)

House of Anjou

...

and Count of Provence (1290). Nonetheless, Philip was a shrewd ruler. Inasmuch as the eastern banks of the Rhône marked the edge of his kingdom, when the river flooded up into the city of Avignon, Philip taxed the city since during periods of flood, the city technically lay within his domain.

Avignon became the Pontifical residence under Pope Clement V

Pope Clement V (; – 20 April 1314), born Raymond Bertrand de Got (also occasionally spelled ''de Guoth'' and ''de Goth''), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 5 June 1305 to his death, in April 1314. He is reme ...

in 1309. His successor, John XXII

Pope John XXII (, , ; 1244 – 4 December 1334), born Jacques Duèze (or d'Euse), was head of the Catholic Church from 7 August 1316 to his death, in December 1334. He was the second and longest-reigning Avignon Pope, elected by the Conclave of ...

, a former bishop of the diocese, made it the capital of Christianity and transformed his former episcopal palace into the primary Palace of the Popes. It was Benedict XII

Pope Benedict XII (, , ; 1285 – 25 April 1342), born Jacques Fournier, was a cardinal and inquisitor, and later, head of the Catholic Church from 30 December 1334 to his death, in April 1342. He was the third Avignon pope and reformed monasti ...

who built the '' Old Palace'' and his successor Clement VI

Pope Clement VI (; 1291 – 6 December 1352), born Pierre Roger, was head of the Catholic Church from 7 May 1342 to his death, in December 1352. He was the fourth Avignon pope. Clement reigned during the first visitation of the Black Death (1 ...

the '' New Palace''. He bought the town on 9 June 1348 from Joanna I of Naples

Joanna I, also known as Johanna I (; December 1325 – 27 July 1382), was Queen of Naples, and Countess of Provence and Forcalquier from 1343 to 1381; she was also Princess of Achaea from 1373 to 1381.

Joanna was the eldest daughter of C ...

, the Queen of Naples and Countess of Provence for 80,000 florins. Innocent VI

Pope Innocent VI (; 1282 – 12 September 1362), born Étienne Aubert, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 18 December 1352 to his death, in September 1362. He was the fifth Avignon pope and the only one with the ...

endowed the city walls.

Under their rule, the Court seethed and attracted many merchants, painters, sculptors and musicians. Their palace, the most remarkable building in the International Gothic

International Gothic is a period of Gothic art that began in Burgundy, France, and northern Italy in the late 14th and early 15th century. It then spread very widely across Western Europe, hence the name for the period, which was introduced by the ...

style was the result, in its construction and ornamentation, of the joint work of the best French architects, Pierre Peysson and Jean du Louvres (called Loubières) and the larger fresco

Fresco ( or frescoes) is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid ("wet") lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plaster, the painting become ...

es from the School of Siena

Siena ( , ; traditionally spelled Sienna in English; ) is a city in Tuscany, in central Italy, and the capital of the province of Siena. It is the twelfth most populated city in the region by number of inhabitants, with a population of 52,991 ...

: Simone Martini

Simone Martini ( – July 1344) was an Italian painter born in Siena.

He was a major figure in the development of early Italian painting and greatly influenced the development of the International Gothic style.

It is thought that Martini was a p ...

and Matteo Giovanetti

Matteo Giovannetti (c. 1322, in Viterbo, Latium – 1368) was an Italian painter. He worked primarily in Avignon as a member of the papal court. He is often thought to have belonged to the Simone Martini school due to some similarities of sty ...

.

The papal library in Avignon was the largest in Europe in the 14th century, with 2,000 volumes Around the library were a group of passionate clerics of letters who were pupils of Petrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

, the founder of Humanism

Humanism is a philosophy, philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and Agency (philosophy), agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The me ...

. At the same time the Clementine Chapel, called the ''Grande Chapelle'', attracted composers, singers, and musicians including Philippe de Vitry

Philippe de Vitry (31 October 12919 June 1361) was a French composer-poet, bishop and Music theory, music theorist in the style of late medieval music. An accomplished, innovative, and influential composer, he was widely acknowledged as a le ...

, inventor of the Ars Nova

''Ars nova'' ()Fallows, David. (2001). "Ars nova". ''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'', second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan. refers to a musical style which flourished in the Kingdom of ...

, and Johannes Ciconia

Johannes Ciconia ( – between 10 June and 13 July 1412) was an important Franco-Flemish composer and music theorist of trecento music during the late Medieval era. He was born in Liège, but worked most of his adult life in Italy, parti ...

.

As Bishop of Cavaillon

The former French diocese of Cavaillon (''Lat.'' dioecesis Caballicensis) existed until the French Revolution as a diocese of the Comtat Venaissin, a fief of the Church of Rome. It was a member of the ecclesiastical province headed by the Metrop ...

, Cardinal Philippe de Cabassoles

Philippe de Cabassole or Philippe de Cabassoles (1305–1372), the Bishop of Cavaillon, Seigneur of Vaucluse, was the great protector of Renaissance poet Francesco Petrarch.

Early life

Philippe was educated by the clergy of Cavaillon and was ...

, Lord of Vaucluse, was the great protector of the Renaissance poet Petrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

.

Urban V

Pope Urban V (; 1310 – 19 December 1370), born Guillaume de Grimoard, was head of the Catholic Church from 28 September 1362 until his death, in December 1370 and was also a member of the Order of Saint Benedict. He was the only Avignon pope ...

took the first decision to return to Rome, to the delight of Petrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

, but the chaotic situation there with different conflicts prevented him from staying there. He died shortly after his return to Avignon.

His successor, Gregory XI

Pope Gregory XI (; born Pierre Roger de Beaufort; c. 1329 – 27 March 1378) was head of the Catholic Church from 30 December 1370 to his death, in March 1378. He was the seventh and last Avignon pope and the most recent French pope. In 1377, ...

, also decided to return to Rome and this ended the first period of the Avignon Papacy. When Gregory XI brought the seat of the papacy to Rome in 1377, the city of Avignon was administered by a legate.

The early death of Gregory XI, however, caused the Great Schism. Clement VII

Pope Clement VII (; ; born Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici; 26 May 1478 – 25 September 1534) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 November 1523 to his death on 25 September 1534. Deemed "the most unfortunate of ...

and Benedict XIII reigned again in Avignon Overall therefore it was nine popes who succeeded in the papal palace and enriched themselves during their pontificate.

From then on until the French Revolution, Avignon and the Comtat were papal possessions: first under the schismatic popes of the Great Schism, then under the popes of Rome ruling via legates until 1542, and then by vice-legates. The Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

appeared at Avignon in 1348 killing almost two-thirds of the city's population.

In all seven popes and two anti-popes resided in Avignon:

*Clement V

Pope Clement V (; – 20 April 1314), born Raymond Bertrand de Got (also occasionally spelled ''de Guoth'' and ''de Goth''), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 5 June 1305 to his death, in April 1314. He is reme ...

: 1305–1314 (curia moved to Avignon March 9, 1309)

*John XXII

Pope John XXII (, , ; 1244 – 4 December 1334), born Jacques Duèze (or d'Euse), was head of the Catholic Church from 7 August 1316 to his death, in December 1334. He was the second and longest-reigning Avignon Pope, elected by the Conclave of ...

: 1316–1334

*Benedict XII

Pope Benedict XII (, , ; 1285 – 25 April 1342), born Jacques Fournier, was a cardinal and inquisitor, and later, head of the Catholic Church from 30 December 1334 to his death, in April 1342. He was the third Avignon pope and reformed monasti ...

: 1334–1342

*Clement VI

Pope Clement VI (; 1291 – 6 December 1352), born Pierre Roger, was head of the Catholic Church from 7 May 1342 to his death, in December 1352. He was the fourth Avignon pope. Clement reigned during the first visitation of the Black Death (1 ...

: 1342–1352

*Innocent VI

Pope Innocent VI (; 1282 – 12 September 1362), born Étienne Aubert, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 18 December 1352 to his death, in September 1362. He was the fifth Avignon pope and the only one with the ...

: 1352–1362

*Urban V

Pope Urban V (; 1310 – 19 December 1370), born Guillaume de Grimoard, was head of the Catholic Church from 28 September 1362 until his death, in December 1370 and was also a member of the Order of Saint Benedict. He was the only Avignon pope ...

: 1362–1370 (in Rome 1367-1370; returned to Avignon 1370)

*Gregory XI

Pope Gregory XI (; born Pierre Roger de Beaufort; c. 1329 – 27 March 1378) was head of the Catholic Church from 30 December 1370 to his death, in March 1378. He was the seventh and last Avignon pope and the most recent French pope. In 1377, ...

: 1370–1378 (left Avignon to return to Rome on September 13, 1376)

;Anti-Popes

*Clement VII

Pope Clement VII (; ; born Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici; 26 May 1478 – 25 September 1534) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 November 1523 to his death on 25 September 1534. Deemed "the most unfortunate of ...

(1378-1394)

* Benedict XIII (1394-1403)

The walls that were built by the popes in the years immediately following the acquisition of Avignon as papal territory are well preserved. As they were not particularly strong fortifications, the Popes relied instead on the immensely strong fortifications of their palace, the "Palais des Papes

The ( English: Palace of the Popes; ''lo Palais dei Papas'' in Occitan) in Avignon, Southern France, is one of the largest and most important medieval Gothic buildings in Europe. Once a fortress and palace, the papal residence was a seat of We ...

". This immense Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, a Germanic people

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Gothic alphabet, an alphabet used to write the Gothic language

** Gothic ( ...

building, with walls 17–18 feet thick, was built 1335–1364 on a natural spur of rock, rendering it all but impregnable to attack. After its capture following the French Revolution, it was used as a barracks and prison for many years but it is now a museum.

Avignon, which at the beginning of the 14th century was a town of no great importance, underwent extensive development during the time the seven Avignon popes and two anti-popes, Clement V to Benedict XIII, resided there. To the north and south of the rock of the Doms, partly on the site of the Bishop's Palace that had been enlarged by John XXII

Pope John XXII (, , ; 1244 – 4 December 1334), born Jacques Duèze (or d'Euse), was head of the Catholic Church from 7 August 1316 to his death, in December 1334. He was the second and longest-reigning Avignon Pope, elected by the Conclave of ...

, was built the Palace of the Popes in the form of an imposing fortress consisting of towers linked to each other and named as follows: La Campane, Trouillas, La Glacière, Saint-Jean, Saints-Anges (Benedict XII), La Gâche, La Garde-Robe (Clement VI), Saint-Laurent (Innocent VI). The Palace of the Popes belongs, by virtue of its severe architecture, to the Gothic art

Gothic art was a style of medieval art that developed in Northern France out of Romanesque art in the 12th century, led by the concurrent development of Gothic architecture. It spread to all of Western Europe, and much of Northern Europe, Norther ...

of the South of France. Other noble examples can be seen in the churches of Saint-Didier, Saint-Pierre, and Saint Agricol as well as in the Clock Tower and in the fortifications built between 1349 and 1368 for a distance of some flanked by thirty-nine towers, all of which were erected or restored by the Roman Catholic Church.

The popes were followed to Avignon by agents (or factors) of the great Italian banking-houses who settled in the city as money-changers and as intermediaries between the Apostolic Camera

The Apostolic Camera (), formerly known as the was an office in the Roman Curia. It was the central board of finance in the papal administrative system and at one time was of great importance in the government of the States of the Church and ...

and its debtors. They lived in the most prosperous quarter of the city which was known as ''the Exchange''. A crowd of traders of all kinds brought to market the produce necessary for maintaining the numerous courts and for the visitors who flocked to it: grain and wine from Provence, the south of France, Roussillon

Roussillon ( , , ; , ; ) was a historical province of France that largely corresponded to the County of Roussillon and French Cerdagne, part of the County of Cerdagne of the former Principality of Catalonia. It is part of the region of ' ...

, and the country around Lyon. Fish was brought from places as distant as Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

; rich cloth and tapestries came from Bruges

Bruges ( , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the province of West Flanders, in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is in the northwest of the country, and is the sixth most populous city in the country.

The area of the whole city amoun ...

and Tournai

Tournai ( , ; ; ; , sometimes Anglicisation (linguistics), anglicised in older sources as "Tournay") is a city and Municipalities in Belgium, municipality of Wallonia located in the Hainaut Province, Province of Hainaut, Belgium. It lies by ...

. The account-books of the Apostolic Camera, which are still kept in the Vatican archives, give an idea of the trade of which Avignon became the centre. The university founded by Boniface VIII

Pope Boniface VIII (; born Benedetto Caetani; – 11 October 1303) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 December 1294 until his death in 1303. The Caetani family was of baronial origin with connections to the p ...

in 1303 had many students under the French popes. They were drawn there by the generosity of the sovereign pontiffs who rewarded them with books or benefice

A benefice () or living is a reward received in exchange for services rendered and as a retainer for future services. The Roman Empire used the Latin term as a benefit to an individual from the Empire for services rendered. Its use was adopted by ...

s.

Early modern period

After the return of the Papacy to Rome, the spiritual and temporal government of Avignon was entrusted to a Legate, usually theCardinal-nephew

A cardinal-nephew (; ; ; ; )Signorotto and Visceglia, 2002, p. 114. Modern French scholarly literature uses the term "cardinal-neveu'". was a Cardinal (Catholicism), cardinal elevated by a pope who was that cardinal's relative. The practice of c ...

. In the Legate's absence, a Vice-Legate (usually a commoner, not a cardinal) governed there. On 7 February 1693, Pope Innocent XII

Pope Innocent XII (; ; 13 March 1615 – 27 September 1700), born Antonio Pignatelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 July 1691 to his death in September 1700.

He took a hard stance against nepotism ...

abolished the position of Cardinal-nephew and the office of Legate in Avignon; in 1692 he had made over its temporal government to the Congregation of Avignon. This was a department of the Curia

Curia (: curiae) in ancient Rome referred to one of the original groupings of the citizenry, eventually numbering 30, and later every Roman citizen was presumed to belong to one. While they originally probably had wider powers, they came to meet ...

in Rome), with the Cardinal Secretary of State

The Secretary of State of His Holiness (; ), also known as the Cardinal Secretary of State or the Vatican Secretary of State, presides over the Secretariat of State of the Holy See, the oldest and most important dicastery of the Roman Curia. Th ...

as presiding prefect, exercising its jurisdiction through the Vice-Legate.

It was linked to the Congregation of Loreto within the Curia. Decisions of the Vice-Legate were appealed to the Congregation. In 1774, the Vice-Legate was made president, thus depriving him of almost all authority. The office was done away with under Pope Pius VI

Pope Pius VI (; born Count Angelo Onofrio Melchiorre Natale Giovanni Antonio called Giovanni Angelo or Giannangelo Braschi, 25 December 171729 August 1799) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 15 February 1775 to hi ...

on 12 June 1790.

The Public Council was composed of 48 councillors chosen by the people, four members of the clergy, and four doctors from the university, and met under the presidency of the chief magistrate of the city. This was the ''viquier'' (Occitan), the annually nominated representative of the Legate or Vice-Legate. The councillors' duty was to watch over the material and financial interests of the city. Their resolutions had to be approved by the Vice-Legate. Three consuls, chosen annually by the Council, had charge of the administration of the streets.

Avignon's survival as a papal enclave was, however, somewhat precarious, as the French crown maintained a large standing garrison at Villeneuve-lès-Avignon

Villeneuve-lès-Avignon (; Provençal: ''Vilanòva d’Avinhon'') is a commune in the Gard department in southern France. It can also be spelled ''Villeneuve-lez-Avignon''.

History

In the 6th century the Benedictine abbey of St André was fou ...

just across the river.

On the death of Philippe de Lévis, Archbishop of Arles, in 1475, Pope Sixtus IV

Pope Sixtus IV (or Xystus IV, ; born Francesco della Rovere; (21 July 1414 – 12 August 1484) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 August 1471 until his death in 1484. His accomplishments as pope included ...

divided the Archdiocese of Arles. He created the Archdiocese of Avignon

The Archdiocese of Avignon (Latin: ''Archidioecesis Avenionensis''; French: ''Archidiocèse d'Avignon'') is a Latin archdiocese of the Catholic Church in France. The diocese exercises jurisdiction over the territory embraced by the departmen ...

, including Avignon and the Dioceses of Carpentras

Carpentras (, formerly ; Provençal dialect, Provençal Occitan language, Occitan: ''Carpentràs'' in classical norm or ''Carpentras'' in Mistralian norm; ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Vaucluse Departments of France, department in the ...

, Cavaillon

Cavaillon (; ) is a commune in the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of Southeastern France.

, and Vaison

Vaison-la-Romaine (; ) is a town in the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region in southeastern France.

Vaison-la-Romaine is famous for its rich Roman ruins and mediaeval town and cathedral. It is also unusual in the way th ...

. Sixtus appointed as Archbishop his Cardinal-nephew Giuliano della Rovere (the future Pope Julius II

Pope Julius II (; ; born Giuliano della Rovere; 5 December 144321 February 1513) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1503 to his death, in February 1513. Nicknamed the Warrior Pope, the Battle Pope or the Fearsome ...

).''Catholic Church in Avignon - Historical Notice''Diocese of Avignon, consulted on 17 October 2011 From the fifteenth century onward, the kings of France sought to control Avignon. In 1472, royal favorite Charles de Bourbon, Archbishop of Lyon became Legate, but in 1474 Pope Sixtus appointed della Rovere in his place. This offended

Louis XI

Louis XI (3 July 1423 – 30 August 1483), called "Louis the Prudent" (), was King of France from 1461 to 1483. He succeeded his father, Charles VII. Louis entered into open rebellion against his father in a short-lived revolt known as the ...

of France, who sent troops to occupy the city in 1476. However, after meeting with della Rovere, Louis agreed to his appointment.

About this time, Avignon was ravaged by a major flood of the Rhone. King Louis XI issued letters patent

Letters patent (plurale tantum, plural form for singular and plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, President (government title), president or other head of state, generally granti ...

for repair of a bridge in Avignon in 1479.

In 1536, during the Italian War of 1536–1538

The Italian war of 15361538 was a conflict between King Francis I of France and Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain. The objective was to achieve control over territories in Northern Italy, in particular the Duchy of Milan. The war ...

,

king Francis I of France

Francis I (; ; 12 September 1494 – 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin once removed and father-in-law Louis&nbs ...

occupied the papal territory, to deny it to the forces of Emperor Charles V

Charles V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain (as Charles I) from 1516 to 1556, and Lord of the Netherlands as titular Duke of Burgundy (as Charles II) fr ...

. When he entered the city the people received him very well, and in return for the reception the people were all granted to them the same privileges that French subjects enjoyed, such as being able to hold state offices. However, at the end of the war in 1538, French forces withdrew.

In 1562, the city was besieged by Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

led by François de Beaumont

François de Beaumont, baron des Adrets (2 February 1587) was a Provence, Provincial military leader. He fought for the House of Valois, Valois monarchy during the Italian Wars distinguishing himself under Charles de Cossé, Count of Brissac, Mars ...

, baron des Adrets.

Charles IX passed through the city during his royal tour of France (1564-1566) together with his court and prominent nobles, including his brother Henri, Duke of Anjou, Henry of Navarre

Henry IV (; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry (''le Bon Roi Henri'') or Henry the Great (''Henri le Grand''), was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 16 ...

, Cardinal de Bourbon Cardinal of Bourbon or Cardinal de Bourbon may refer to:

* Charles II, Duke of Bourbon (1433–1488), archbishop of Lyon

* Louis de Bourbon-Vendôme (1493–1557), archbishop of Sens

*Charles, Cardinal de Bourbon (born 1523)

Charles de Bourbon (2 ...

, and Cardinal de Lorraine. The court stayed for three weeks.

In 1583 King Henry III offered exchange the Marquisate of Saluzzo

The Marquisate of Saluzzo () was a historical Italian state that included parts of the current region of Piedmont and of the French Alps. The Marquisate was much older than the Renaissance lordships, being a legacy of the feudalism of the High ...

for Avignon, but this offer was refused by Pope Gregory XIII

Pope Gregory XIII (, , born Ugo Boncompagni; 7 January 1502 – 10 April 1585) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 May 1572 to his death in April 1585. He is best known for commissioning and being the namesake ...

. In 1618 Cardinal Richelieu

Armand Jean du Plessis, 1st Duke of Richelieu (9 September 1585 – 4 December 1642), commonly known as Cardinal Richelieu, was a Catholic Church in France, French Catholic prelate and statesman who had an outsized influence in civil and religi ...

was exiled in Avignon. The city was visited by Vincent de Paul

Vincent de Paul, CM (24 April 1581 – 27 September 1660), commonly known as Saint Vincent de Paul, was an Occitan French Catholic priest who dedicated himself to serving the poor.

In 1622, Vincent was appointed as chaplain to the galleys. ...

in 1607 and also by Francis de Sales

Francis de Sales, Congregation of the Oratory, C.O., Order of Minims, O.M. (; ; 21 August 156728 December 1622) was a Savoyard state, Savoyard Catholic prelate who served as Bishop of Geneva and is a saint of the Catholic Church. He became n ...

in 1622.

By the mid-17th century, Avignon was considered a ''de facto'' part of the Kingdom of France by the provincial ''parlement'' of Provence. In 1663, Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

seized Avignon and the Comtat Venaissin in retaliation for the Corsican Guard Affair

The Corsican Guard Affair was an event in French and papal history, illustrating Louis XIV of France's will to impose his power on other European leaders.

On 20 August 1662, soldiers of pope Alexander VII's Corsican Guard came to blows with the F ...

, an attack on the Duc de Créqui, his ambassador to the Holy See. Louis returned the Comtat in 1664 after the Pope apologised for the attack. Louis annexed it a second time in 1688, from Pope Innocent XI

Pope Innocent XI (; ; 16 May 1611 – 12 August 1689), born Benedetto Odescalchi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 21 September 1676 until his death on 12 August 1689.

Political and religious tensions with ...

, and returned it to Pope Alexander VIII

Pope Alexander VIII (; 22 April 1610 – 1 February 1691), born Pietro Vito Ottoboni, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 October 1689 to his death in February 1691. He is the most recent pope to take the ...

by letters patent

Letters patent (plurale tantum, plural form for singular and plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, President (government title), president or other head of state, generally granti ...

on 20 November 1689.

Avignon was free from conflict until Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached maturity (then defi ...

next occupied the Comtat from 1768 to 1774 and Avignon itself from 1768 to 1769, substituting French institutions for those in force with the approval of the people of Avignon and leading to the rise of a pro-French faction.

At the beginning of the 18th century, the streets of Avignon were narrow and winding, but buildings changed and houses gradually replaced the old buildings. Around the city there were mulberry plantations, orchards, and grasslands. On 2 January 1733 François Morénas founded a newspaper, the '' Courrier d'Avignon'', whose name changed over time and through prohibitions. As it was published in the papal enclave, the newspaper was exempt from the French press control laws, while remaining subject to the papal authorities. The ''Courrier d'Avignon'' appeared from 1733 to 1793 with two interruptions: one between July 1768 and August 1769 due to France's annexation of Avignon and the other between 30 November 1790 and 24 May 1791. Eugène Hatin''Historical Bibliography and critique of the French periodical press''

Firmin Didot Frères, Paris, 1866, p. 306, consulted on 17 October 2011

From the French Revolution to the end of the 19th century

On 12 and 13 September 1791 the National Constituent Assembly voted for the annexation of Avignon and the reunion ofComtat Venaissin

The (; ; 'County of Venaissin'), often called the for short, was a part of the Papal States from 1274 to 1791, in what is now the region of Southern France.

The region was an enclave within the Kingdom of France, comprising the area aroun ...

with the kingdom of France following a referendum submitted to the inhabitants of the Comtat.

On the night of 16 to 17 October 1791, after the lynching by a mob of the secretary-clerk of the commune who was wrongly suspected of wanting to seize church property, the event called the Massacres of La Glacière took place, when 60 people were summarily executed and thrown into the dungeon of the tower on the Palais des Papes

The ( English: Palace of the Popes; ''lo Palais dei Papas'' in Occitan) in Avignon, Southern France, is one of the largest and most important medieval Gothic buildings in Europe. Once a fortress and palace, the papal residence was a seat of We ...

.

On 7 July 1793 federalist