Henry Alsberg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Henry Garfield Alsberg (September 21, 1881November 1, 1970) was an American journalist and writer who served as the founding director of the

In January 1920, Alsberg traveled north, intending to make his way to Moscow; "a believer in the utopia promised by a classless society, ewanted to witness and write about those ideals made manifest". After weeks trying to get into Soviet Russia, he finally succeeded in May. In August, he accompanied

In January 1920, Alsberg traveled north, intending to make his way to Moscow; "a believer in the utopia promised by a classless society, ewanted to witness and write about those ideals made manifest". After weeks trying to get into Soviet Russia, he finally succeeded in May. In August, he accompanied  Alsberg left Russia for Germany in May 1921. In September he went to Mexico to observe and write about the presidency of

Alsberg left Russia for Germany in May 1921. In September he went to Mexico to observe and write about the presidency of

Alsberg became involved in the theater during the early 1920s. In 1924, Alsberg obtained the English translation rights to

Alsberg became involved in the theater during the early 1920s. In 1924, Alsberg obtained the English translation rights to

Alsberg was particularly concerned about the conditions of political prisoners in Russia. He tried to involve the

Alsberg was particularly concerned about the conditions of political prisoners in Russia. He tried to involve the

Henry G. Alsberg and Dora Thea Hettwer Collection, Bienes Museum of the Modern Book, Broward County Library.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Alsberg, Henry G 1881 births 1970 deaths 20th-century American journalists American male journalists Jews from New York (state) American people of German-Jewish descent Columbia Law School alumni Writers from Manhattan People of the United States Office of War Information

Federal Writers' Project

The Federal Writers' Project (FWP) was a federal government project in the United States created to provide jobs for out-of-work writers and to develop a history and overview of the United States, by state, cities and other jurisdictions. It was ...

.

A lawyer by training, he was a foreign correspondent during the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

, secretary to the U.S. Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, and an influential volunteer for refugee aid efforts. Alsberg was a producer at the Provincetown Playhouse

The Provincetown Playhouse is a historic theatre at 133 MacDougal Street between West 3rd and 4th streets in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. It is named for the Provincetown Players, who converted the forme ...

. He spent years traveling through war-torn Europe on behalf of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee Advert

Where and how does this article resemble an WP:SOAP, advert and how should it be improved? See: Wikipedia:Spam (you might trthe Teahouseif you have questions).

American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, also known as Joint or JDC, is a J ...

. After publishing several magazines for the Federal Emergency Relief Administration

The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) was a program established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, building on the Hoover administration's Emergency Relief and Construction Act. It was replaced in 1935 by the Works Progre ...

, he was appointed to head the Federal Writers' Project. Fired from the project in 1939 shortly after testifying before the House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative United States Congressional committee, committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 19 ...

, he worked for a short time for the Office of War Information

The United States Office of War Information (OWI) was a United States government agency created during World War II. The OWI operated from June 1942 until September 1945. Through radio broadcasts, newspapers, posters, photographs, films and other ...

, before joining Hastings House Publishers as an editor.

Early life and education

Alsberg was born September 21, 1881, inManhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

to Meinhard and Bertha Alsberg. Meinhard was born in Arolsen

Bad Arolsen (, until 1997 Arolsen, being the German name for ''Spa'') is a small town in northern Hesse, Germany, in Waldeck-Frankenberg district. From 1655 until 1918 it served as the residence town of the Princes of Waldeck (state), Waldeck-Pyr ...

, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and immigrated as a child with his family to the United States in 1865. He was naturalized in 1876. He married Bertha (born in New York City) and had four children with her, of whom Henry was the youngest.

Alsberg's parents were secular Jews, his mother being indifferent to religion and his father described as "aggressive in his agnosticism". Alsberg had neither a bris

The ''brit milah'' (, , ; "Covenant (religion), covenant of circumcision") or ''bris'' (, ) is Religion and circumcision, the ceremony of circumcision in Judaism and Samaritanism, during which the foreskin is surgically removed. According to t ...

nor a Bar Mitzvah

A ''bar mitzvah'' () or ''bat mitzvah'' () is a coming of age ritual in Judaism. According to Halakha, Jewish law, before children reach a certain age, the parents are responsible for their child's actions. Once Jewish children reach that age ...

. He attended a shul

A synagogue, also called a shul or a temple, is a place of worship for Jews and Samaritans. It is a place for prayer (the main sanctuary and sometimes smaller chapels) where Jews attend religious services or special ceremonies such as Jewi ...

only once as a child, when his grandmother took him to Temple Emanu-El, which infuriated his father.

Initially home-schooled, Alsberg was fluent in German and French, and spoke some Yiddish and Russian. For his secondary education, he attended Mount Morris Latin School. Alsberg suffered from lifelong digestive problems, possibly related to an incident in his teens when his appendix ruptured in the middle of the night. Alsberg waited till morning to tell his family rather than wake them up, and had emergency abdominal surgery.

Alsberg, called Hank by friends and family, entered Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

at age 15 in 1896, the youngest member of the class of 1900, who called themselves the "Naughty-Naughtians". Alsberg was an editor of the literary magazine ''The Morningside'', and also contributed poems and short stories. He belonged to the Société Française and the Philharmonic Society (cellist), and participated in baseball, wrestling, and fencing. After graduation, Alsberg enrolled in Columbia Law School

Columbia Law School (CLS) is the Law school in the United States, law school of Columbia University, a Private university, private Ivy League university in New York City.

The school was founded in 1858 as the Columbia College Law School. The un ...

, graduating in 1903. Alsberg played two seasons on both the college and varsity football teams as guard and tackle.

After practicing law for three years, Alsberg entered Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher lear ...

's Graduate School of Arts and Science for a year to study comparative literature.

Journalism, theater, and international activity

Early years in journalism

Uninterested in finishing his graduate studies at Harvard or practicing law, Alsberg moved back to New York City to write. He sent an early play toPaul Kester

Paul Kester (November 2, 1870 – June 21, 1933) was an American playwright and novelist. He was the younger brother of journalist Vaughan Kester and a cousin of the literary editor and critic William Dean Howells.

Life and career

Kester was bor ...

, who recommended it to Bertha Galland. He sold a short story, "Soirée Kokimono", to '' The Forum'' in 1912; the story was selected for the following year's ''Forum Stories'' compilation.

Abram Isaac Elkus, a friend of Alsberg's brother Carl Carl may refer to:

*Carl, Georgia, city in USA

*Carl, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

*Carl (name), includes info about the name, variations of the name, and a list of people with the name

*Carl², a TV series

* "Carl", an episode of tel ...

and a strategist for Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

's presidential campaign, sent Alsberg to London to investigate claims that American-made goods were cheaper abroad than in the U.S. due to Republican-imposed tariffs. Alsberg wrote up the results of his investigation in an article published in the ''New York Sunday World''. The Wilson campaign used it to buttress their platform's call to reduce tariffs.

Alsberg began writing for the ''New York Evening Post

The ''New York Post'' (''NY Post'') is an American conservative

daily tabloid newspaper published in New York City. The ''Post'' also operates three online sites: NYPost.com; PageSix.com, a gossip site; and Decider.com, an entertainm ...

'' in 1913, as well as its sister publication ''The Nation''. His 1914 article for ''The Masses

''The Masses'' was a graphically innovative American magazine of socialist politics published monthly from 1911 until 1917, when federal prosecutors brought charges against its editors for conspiring to obstruct conscription in the United Stat ...

'' criticized the churches that turned away homeless during the brutal blizzard that hit New York on March 1. Alsberg went to London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

where he began working as a roving foreign correspondent for ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is a progressive American monthly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper ...

'', ''New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 to 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers as a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under publisher Jo ...

'', and London's '' Daily Herald''.

In August 1916, Alsberg was appointed personal secretary and press attaché to Elkus, who had been appointed U.S. Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire; they traveled on the ''Oscar II'' to Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

via Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a population of 1.4 million in the Urban area of Copenhagen, urban area. The city is situated on the islands of Zealand and Amager, separated from Malmö, Sweden, by the ...

. Alsberg took charge of the embassy's efforts to aid Armenians and Jews, which put him in contact with the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee Advert

Where and how does this article resemble an WP:SOAP, advert and how should it be improved? See: Wikipedia:Spam (you might trthe Teahouseif you have questions).

American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, also known as Joint or JDC, is a J ...

(JDC). When the U.S. declared war on Germany in April 1917, Turkey broke off diplomatic relations and the American embassy officials left. On his return to the states, Alsberg met with Secretary of State Robert Lansing

Robert Lansing (; October 17, 1864 – October 30, 1928) was an American lawyer and diplomat who served as the 42nd United States Secretary of State under President Woodrow Wilson from 1915 to 1920. As Counselor to the State Department and then a ...

to brief him on conditions in Constantinople and offered a plan for separating the Ottoman Empire from the German Alliance, which Lansing passed on to Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

. The next day, former Ambassador Henry Morgenthau Henry Morgenthau may refer to:

* Henry Morgenthau Sr. (1856–1946), United States diplomat

* Henry Morgenthau Jr.

Henry Morgenthau Jr. (; May 11, 1891February 6, 1967) was the United States Secretary of the Treasury during most of the adminis ...

suggested a similar plan to Lansing. A mission to Turkey consisted of Morgenthau and Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, advocating judicial restraint.

Born in Vienna, Frankfurter im ...

(then an assistant to the Secretary of War), with Alsberg advising them on conditions and issues.

In 1917, Alsberg taught a course on the socialist-inspired cooperative movement at the Rand School of Social Science

The Rand School of Social Science was formed in 1906 in New York City by adherents of the Socialist Party of America. The school aimed to provide a broad education to workers, imparting a politicizing class-consciousness, and additionally served a ...

, while again writing for ''Evening Post'' and ''The Nation''. In the ''Evening Post'', Alsberg disputed the authenticity of the Sisson Documents

The Sisson Documents () are a set of 68 Russian-language documents obtained in 1918 by Edgar Sisson, the Petrograd representative of the United States Committee on Public Information. Published as ''The German-Bolshevik Conspiracy'', they purporte ...

, claiming that they were forgeries, which was later confirmed by historians. In Jan 1919, Alsberg was secretary of the Palestine Restoration Fund Campaign's National Finance Commission, and wrote for ''The Maccabaean'', the official organ of the Zionist Organization of America

The Zionist Organization of America (ZOA; ) is an American nonprofit pro-Israel organization. Founded in 1897, as the Federation of American Zionists, it was the first official Zionist organization in the United States. Early in the 20th century ...

. Later in 1919, Alsberg returned to Europe as a foreign correspondent for ''The Nation''. He attended the Peace Conference

A peace conference is a diplomatic meeting where representatives of states, armies, or other warring parties converge to end hostilities by negotiation and signing and ratifying a peace treaty.

Significant international peace conferences in ...

in Paris as attaché to the Zionist delegation. While there, Alsberg reconnected with the JDC which needed volunteers to assess and provide relief to destitute Jews in Central and Eastern Europe.

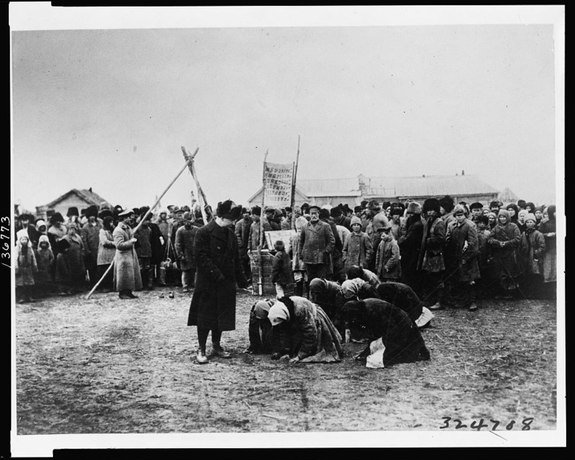

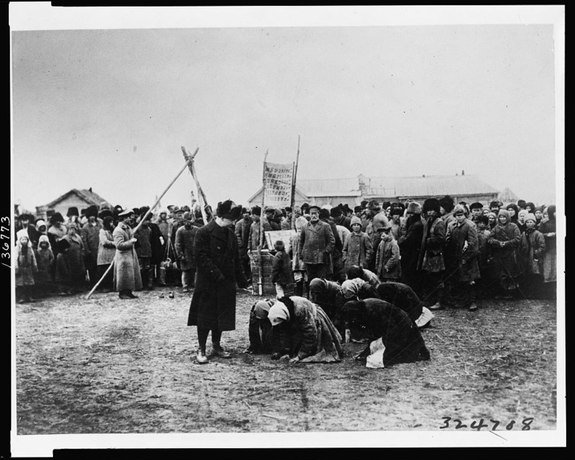

Work with the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee

While volunteering with the JDC, Alsberg's passport listed his occupation as "food relief" for theAmerican Relief Administration

American Relief Administration (ARA) was an American Humanitarian aid, relief mission to Europe and later Russian Civil War, post-revolutionary Russia after World War I. Herbert Hoover, future president of the United States, was the program dire ...

. Alsberg described the period after the Russian Revolution and World War I as "the emergence of many minor nationalities, all imbued with grand imperialistic passions, fighting for their independence in a condition of economic wretchedness and moral degradation". New nations were formed after the break-up of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires.

He spent four years in various countries, including the "bandit-ridden Ukraine". His first stop was the new country of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

, where he set up programs in Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

to help refugees. Alsberg also continued his reporting for ''The Nation'', the ''London Herald'', and the ''New York World'', bringing the anti-Semitism he was observing to international attention. Some of his articles were noticed by American authorities for their sympathy to Bolshevik, anarchist, and radical ideas, and he was observed for some time by Allied military intelligence.

In April 1919, the JDC transferred him to Poland, though he went reluctantly, concerned about abandoning his work in Prague. In June, he returned briefly to Prague, then went to Paris where he witnessed the signing of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

. For the rest of the year, Alsberg traveled throughout eastern Europe, reporting on Hungary, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Romania, and the Balkans. His experiences and observations made him abhor violence.

Travels in Russia

In September 1919, Alsberg arrived atKamianets-Podilskyi

Kamianets-Podilskyi (, ; ) is a city on the Smotrych River in western Ukraine, western Ukraine, to the north-east of Chernivtsi. Formerly the administrative center of Khmelnytskyi Oblast, the city is now the administrative center of Kamianets ...

, which was being fought over by the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

, the White Army

The White Army, also known as the White Guard, the White Guardsmen, or simply the Whites, was a common collective name for the armed formations of the White movement and Anti-Sovietism, anti-Bolshevik governments during the Russian Civil War. T ...

, and the Ukrainian Independence Movement. He went to Odessa

ODESSA is an American codename (from the German language, German: ''Organisation der ehemaligen SS-Angehörigen'', meaning: Organization of Former SS Members) coined in 1946 to cover Ratlines (World War II aftermath), Nazi underground escape-pl ...

and on to Kiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

with Allied military officers, where he reported on the pogrom

A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of Massacre, massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe late 19th- and early 20th-century Anti-Jewis ...

s, the terrorism by the Cossacks

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic languages, East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borde ...

, and the atrocities of the Bolsheviks.

In January 1920, Alsberg traveled north, intending to make his way to Moscow; "a believer in the utopia promised by a classless society, ewanted to witness and write about those ideals made manifest". After weeks trying to get into Soviet Russia, he finally succeeded in May. In August, he accompanied

In January 1920, Alsberg traveled north, intending to make his way to Moscow; "a believer in the utopia promised by a classless society, ewanted to witness and write about those ideals made manifest". After weeks trying to get into Soviet Russia, he finally succeeded in May. In August, he accompanied Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born Anarchism, anarchist revolutionary, political activist, and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europ ...

and Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman (November 21, 1870June 28, 1936) was a Russian-American anarchist and author. He was a leading member of the anarchist movement in the early 20th century, famous for both his political activism and his writing.

Be ...

(both of whom had been deported to Russia from the United States the previous year) on a six-week expedition to collect historic materials for the Museum of the Revolution. Their accommodations and treatment by the Soviets were luxurious and opulent, but Alsberg was able to get away from the controlled tours to see the disparity between what they were being told and the conditions of the general public. He conceded that "Russia has not now a democratic form of government in any sense of the word", but was still swayed by the framework of the "necessity of extreme measures in order to save the revolution", comparing it to U.S. actions during war when the government found "habeas corpus, free speech, and such-like refinements...superfluous". In Poltava

Poltava (, ; , ) is a city located on the Vorskla, Vorskla River in Central Ukraine, Central Ukraine. It serves as the administrative center of Poltava Oblast as well as Poltava Raion within the oblast. It also hosts the administration of Po ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

, Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born Anarchism, anarchist revolutionary, political activist, and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europ ...

acted as interpreter for Alsberg while he interviewed local Soviet officials. In Goldman's autobiography, she noted that Alsberg was particularly affected by the stories that the townspeople in Fastov

Fastiv (, ) is a city in the Kyiv Oblast (province) in central Ukraine. On older maps it is depicted as Khvastiv (; ). Administratively, it serves as the administrative centre of the Fastiv Raion (district), to which it does not administratively ...

told them of the pogrom

A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of Massacre, massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe late 19th- and early 20th-century Anti-Jewis ...

s.

For his travels with Goldman and Berkman, Alsberg had obtained written permission from the Soviet Union Foreign Office's Cheka

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ( rus, Всероссийская чрезвычайная комиссия, r=Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya, p=fsʲɪrɐˈsʲijskəjə tɕrʲɪzvɨˈtɕæjnəjə kɐˈmʲisʲɪjə, links=yes), ...

and from a high-ranking Soviet official to travel on the expedition, but did not get a special visa from the local Moscow Cheka. The Foreign Office assured him the Moscow Cheka visa was not needed. But during their travels, orders were sent out to arrest Alsberg for travelling in Russia without having obtained permission from the Moscow Cheka, and he was taken into custody in Zhmerynka

Zhmerynka (, ) is a city in Vinnytsia Oblast, central Ukraine. It serves as the administrative center of Zhmerynka Raion within the oblast. Population: It is located in the historic region of Podolia.

Name

There are many propositions as far as ...

. Alsberg managed to get the police agent who escorted him to Moscow drunk on the trip. Arriving at the police station in Moscow carrying the agent, Alsberg set the unconscious body on the desk and said, "Here is the man you sent out to find me."

The following year, Alsberg accompanied the Bolshevik delegation to the Russo-Polish peace talks in Riga

Riga ( ) is the capital, Primate city, primate, and List of cities and towns in Latvia, largest city of Latvia. Home to 591,882 inhabitants (as of 2025), the city accounts for a third of Latvia's total population. The population of Riga Planni ...

, and he wrote about the signing of the armistice. J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American attorney and law enforcement administrator who served as the fifth and final director of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) and the first director of the Federal Bureau o ...

, head of the newly formed Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. An agency of the United States Department of Justice, the FBI is a member of ...

(now the FBI), received voluminous reports on Alsberg due to his involvement with the Bolsheviks, his friendship with Goldman and Berkman, and because he was a Jew. Alsberg continued his association with and work for the JDC, working in Italy with refugees.

In Feb 1921, Alsberg returned to Russia. He was in Moscow during the Kronstadt rebellion

The Kronstadt rebellion () was a 1921 insurrection of Soviet sailors, Marines, naval infantry, and civilians against the Bolsheviks, Bolshevik government in the Russian port city of Kronstadt. Located on Kotlin Island in the Gulf of Finland, ...

, an event which brought him to condemn the Bolshevik regime in the article "Russia: Smoked Glass vs. Rose-Tint" in ''The Nation''. American Max Eastman

Max Forrester Eastman (January 4, 1883 – March 25, 1969) was an American writer on literature, philosophy, and society, a poet, and a prominent political activist. Moving to New York City for graduate school, Eastman became involved with radica ...

responded in '' The Liberator'', calling it "journalistic emotionalizing" and declaring Alsberg was "a petit-bourgeois liberal". Alsberg's article was reprinted in ''New York Call'' and reported on the front page of the ''New York Tribune''. In all, Alsberg made six trips to Russia, carrying some $10,000 in cash to distribute to Jews in need. In one village, when they heard that soldiers were approaching, village elders dressed Alsberg in an old coat and skullcap as a disguise; he escaped on a ferry to Rumania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to the east, and the Black Sea t ...

while the soldiers' bullets missed their target.

Alsberg left Russia for Germany in May 1921. In September he went to Mexico to observe and write about the presidency of

Alsberg left Russia for Germany in May 1921. In September he went to Mexico to observe and write about the presidency of Álvaro Obregón

Álvaro Obregón Salido (; 19 February 1880 – 17 July 1928) was a Mexican general, inventor and politician who served as the 46th President of Mexico from 1920 to 1924. Obregón was re-elected to the presidency in 1928 but was assassinated b ...

following the Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution () was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from 20 November 1910 to 1 December 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It saw the destruction of the Federal Army, its ...

. His articles accused the U.S. State Department of "putting into effect a private and unofficial imperialism of its own in Latin America" – accusations which were debated in major newspapers across the U.S. After the famine of 1921, the JDC sent Alsberg back to Russia to help set up trade schools and agricultural colonies for Jewish families.

JDC history and theater work

The JDC hired Alsberg to write a history of their organization in 1923, which was his first paid work for them. Alsberg submitted a draft in the summer of 1927. Although it was never published, Susan Rubenstein DeMasi wrote: "it still remains as perhaps the most exhaustive account of pre-World War II Central and Eastern European Jewry ever written." Alsberg became involved in the theater during the early 1920s. In 1924, Alsberg obtained the English translation rights to

Alsberg became involved in the theater during the early 1920s. In 1924, Alsberg obtained the English translation rights to S. Ansky

Shloyme Zanvl Rappoport (1863 – November 8, 1920), also known by his pen name S. An-sky, was a Jewish author, playwright, researcher of Jewish folklore, polemicist, and cultural and political activist. He is best known for his play '' The ...

's ''The Dybbuk

''The Dybbuk'', or ''Between Two Worlds'' (, trans. ''Mezh dvukh mirov ibuk'; , ''Tsvishn Tsvey Veltn – der Dibuk'') is a play by S. An-sky, authored between 1913 and 1916. It was originally written in Russian and later translated into Yidd ...

'', written in Yiddish. His adaptation ran at the off-Broadway Neighborhood Playhouse

A neighbourhood (Commonwealth English) or neighborhood (American English) is a geographically localized community within a larger town, city, suburb or rural area, sometimes consisting of a single street and the buildings lining it. Neighbourh ...

. ''The New York Times'' called his adaptation "a triumph", naming it one of the ten best plays of the 1925–1926 season. Alsberg would continue to earn from productions of his adaptation of ''The Dybbuk'' throughout his life.

Alsberg was a director of the Provincetown Playhouse

The Provincetown Playhouse is a historic theatre at 133 MacDougal Street between West 3rd and 4th streets in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. It is named for the Provincetown Players, who converted the forme ...

company for the 1925–1926 season, during which he translated and adapted ''Turandot

''Turandot'' ( ; see #Origin and pronunciation of the name, below) is an opera in three acts by Giacomo Puccini to a libretto in Italian by Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni. Puccini left the opera unfinished at the time of his death in 1924; it ...

'' with Isaac Don Levine

Isaac Don Levine (January 19, 1892 – February 15, 1981) was a 20th-century Russian-born American journalist and anticommunist writer, who is known as a specialist on the Soviet Union.

He worked with Soviet ex-spy Walter Krivitsky in a 1939 e ...

. He was associate director of ''Abraham's Bosom

The Bosom of Abraham refers to the place of comfort in the biblical Sheol (or Hades in the Greek Septuagint version of the Hebrew scriptures from around 200 BC, and therefore so described in the New Testament) where the righteous dead await re ...

'', which won Paul Green a Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

, and producer of '' Him'' by E. E. Cummings

Edward Estlin Cummings (October 14, 1894 – September 3, 1962), commonly known as e e cummings or E. E. Cummings, was an American poet, painter, essayist, author, and playwright. During World War I, he worked as an ambulance driver and was ...

. George Gershwin

George Gershwin (; born Jacob Gershwine; September 26, 1898 – July 11, 1937) was an American composer and pianist whose compositions spanned jazz, popular music, popular and classical music. Among his best-known works are the songs "Swan ...

asked Alsberg to act as librettist on an opera adaptation of ''The Dybbuk'', to open at the Metropolitan Opera, but was unable to obtain the musical rights.

International Committee for Political Prisoners

Alsberg was particularly concerned about the conditions of political prisoners in Russia. He tried to involve the

Alsberg was particularly concerned about the conditions of political prisoners in Russia. He tried to involve the American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is an American nonprofit civil rights organization founded in 1920. ACLU affiliates are active in all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico. The budget of the ACLU in 2024 was $383 million.

T ...

(ACLU) in his cause, but their charter limited them to domestic issues, so ACLU co-founder Roger Baldwin and Alsberg formed the International Committee for Political Prisoners (ICPP), enlisting people such as Frankfurter, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (August 7, 1890 – September 5, 1964) was an American labor leader, activist, and feminist who played a leading role in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Flynn was a founding member of the American Civil Libe ...

, W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relativel ...

, and Carlo Tresca

Carlo Tresca (March 9, 1879 – January 11, 1943) was an Italian-American dissident, newspaper editor, orator, and labor organizer and activist who was a leader of the Industrial Workers of the World during the 1910s. He is remembered as a leadi ...

. (Baldwin later described the ICPP as similar to Amnesty International.) Alsberg contributed many documents to and edited ''Letters from Russian Prisons

''Letters from Russian Prisons: Consisting of Reprints of Documents by Political Prisoners in Soviet Prisons, Prison Camps and Exile, and Reprints of Affidavits Concerning Political Persecution in Soviet Russia, Official Statements by Soviet Auth ...

'', and insisted that the title page list all committee members without singling out any individual contributors. The book was intended to bring to international attention the mistreatment that political prisoners in Russia suffered. Some committee members resigned, feeling that the book was too anti-Soviet. Alsberg later gathered material for and edited ''Political Persecution Today'' (Poland) and ''The Fascist Dictatorship'' (Italy) for the ICPP. Alsberg left the committee by 1928.

Alsberg spent several years traveling in Europe and working on his own writing, including his autobiography which he never finished. In March 1934, he joined the publications division of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration

The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) was a program established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, building on the Hoover administration's Emergency Relief and Construction Act. It was replaced in 1935 by the Works Progre ...

(FERA) where his first assignment was editing ''America Fights the Depression'', a book about the Civil Works Administration

The Civil Works Administration (CWA) was a short-lived job creation program established by the New Deal during the Great Depression in the United States in order to rapidly create mostly manual-labor jobs for millions of unemployed workers. The j ...

's accomplishments. He then took on editing two magazines for the agency.

Federal Writers' Project

The Federal Writers' Project (FWP) was part ofFederal One

Federal Project Number One, also referred to as Federal One (Fed One), is the collective name for a group of projects under the Works Progress Administration, a New Deal program in the United States. Of the $4.88 billion allocated by the Emergen ...

, one of the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; from 1935 to 1939, then known as the Work Projects Administration from 1939 to 1943) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to car ...

programs created to provide jobs during the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

. Jacob Baker, chief architect of Federal One, appointed Alsberg as head of the FWP in July 1935. At the time, Alsberg dubbed himself a "philosophical anarchist" although others labelled him a "tired radical of the 20s". On Alsberg's appointment, friends privately questioned the choice as Alsberg was considered to be reluctant to make decisions and often left projects unfinished. Alsberg was not selected as director of the Writers' Project because of any administrative or managerial skill, but rather because of his understanding of the project's purpose and his insistence on high editorial standards for the project's products. Novelist Vincent McHugh classified Alsberg in an elite group: "men with a ''public'' sense, a feeling for broad human movements and how people are caught up in them." Baker described Alsberg to an associate as "An anarchistic sort of a fellow incapable of administration but one with a great deal of creative talent".

Project leadership

Alsberg came to the Writers' Project with a "visionary sense of its potential to join social reform with the democratic renaissance of American letters". His original vision for the project was to produce a guide for each major region of the country, but changed the plans to a guide for each state due to political pressure. Alsberg insisted that the American Guide Series be much more than an AmericanBaedeker

Verlag Karl Baedeker, founded by Karl Baedeker on 1 July 1827, is a German publisher and pioneer in the business of worldwide travel guides. The guides, often referred to simply as "List of Baedeker Guides, Baedekers" (a term sometimes used to re ...

; the guides needed to capture the whole of American civilization and culture and celebrate the diversity of the nation. He required that each state project include ethnography with particular attention to Native Americans and African Americans, and that the front third of every guide contain essays on local culture, history, economics, etc.

Alsberg appointed fourteen women as state directors of the project, and 40% of FWP employees were women. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt ( ; October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the longest-serving First Lady of the United States, first lady of the United States, during her husband Franklin D ...

was an enthusiastic supporter of the FWP. Two of the writers Alsberg personally recruited to the Writers' Project were John Cheever

John William Cheever (May 27, 1912 – June 18, 1982) was an American short story writer and novelist. He is sometimes called "the Chekhov of the suburbs". His fiction is mostly set on the Upper East Side of Manhattan; the Westchester suburbs ...

and Conrad Aiken

Conrad Potter Aiken (August 5, 1889 – August 17, 1973) was an American writer and poet, honored with a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award, and was United States Poet Laureate from 1950 to 1952. His published works include poetry, short st ...

.

Alsberg felt the American Guide Series needed to be supplemented with books about the people of the country. With this in mind, the project published ethnic studies such as ''The Italians of New York'' (in both English and Italian), ''Jewish Landsmanschaften of New York'' (in Yiddish), ''The Armenians of Massachusetts'', and ''The Swedes and Finns of New Jersey''. One of Alsberg's letters describes the approach that he wanted the ethnic studies writers to take:

Reception

Although the first books in theAmerican Guide Series

The American Guide Series includes books and pamphlets published from 1937 to 1941 under the auspices of the Federal Writers' Project (FWP), a Great Depression, Depression-era program that was part of the larger Works Progress Administration in the ...

published under the auspices of the project—''Idaho'', ''Washington: City and Capital'', and ''Cape Cod Pilot''—were met with praise, the furor that accompanied the release of ''Massachusetts'' damaged the reputations of the project and Alsberg. A reporter published a story decrying the Massachusetts guide because it spent forty-one lines discussing the Sacco-Vanzetti

Nicola Sacco (; April 22, 1891 – August 23, 1927) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (; June 11, 1888 – August 23, 1927) were Italian immigrants and anarchists who were controversially convicted of murdering Alessandro Berardelli and Frederick Parm ...

case, while only giving nine lines to the Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was a seminal American protest, political and Mercantilism, mercantile protest on December 16, 1773, during the American Revolution. Initiated by Sons of Liberty activists in Boston in Province of Massachusetts Bay, colo ...

and five to the Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre, known in Great Britain as the Incident on King Street, was a confrontation, on March 5, 1770, during the American Revolution in Boston in what was then the colonial-era Province of Massachusetts Bay.

In the confrontati ...

. Other newspapers jumped on the bandwagon to smear the Writers' Project (and the Roosevelt administration by association). Senators demanded investigations. More scrutiny found that the guide had a number of passages that appeared to be pro-labor, and the book was banned by several Massachusetts mayors. Ralph M. Easley, representing a group called the National Civic Federation, complained in a letter to President Roosevelt that the Writer's Project was "dominated by Communist sympathizers whose principal interest was political agitation". After these complaints, WPA administrators placed a worker in the Writers' Project central office to censor "subversive" material.

When Alsberg threw a cocktail party to celebrate the publication of the Washington guide, Alsberg and the Writers' Project were attacked on the Senate floor by Mississippi's Senator Bilbo in a tirade because a woman from his own state had been invited to a party that had both white and black guests. Bilbo later had his comments expunged from the ''Congressional Record''.

Alsberg struggled with the project's tension between providing jobs (relief) and creative works. The American Guide Series was a necessary product to justify the project's existence, but Alsberg sympathized with the many writers who chafed at being confined to writing guidebooks and secretly allowed some project writers to focus on their own creative writing. One of those writers, Richard Wright, used the time to work on his first novel, ''Native Son

Native may refer to:

People

* '' Jus sanguinis'', nationality by blood

* '' Jus soli'', nationality by location of birth

* Indigenous peoples, peoples with a set of specific rights based on their historical ties to a particular territory

** Nat ...

'', which would become a bestseller when published in 1940. Alsberg also quietly attempted to put out a literary magazine, but the single issue was subject to bickering and resistance from the Writers Union (Stalinists

Stalinism (, ) is the totalitarian means of governing and Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1927 to 1953 by dictator Joseph Stalin and in Soviet satellite states between 1944 and 1953. Stalinism inc ...

, who insisted that the magazine's editors were Trotskyites

Trotskyism (, ) is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as a ...

). Knowing the Writers' Project was a target of the Dies Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloyalty an ...

, Alsberg abandoned the magazine effort and also ended the creative writing program.

Dies Committee

The Dies Committee was a special investigation committee established by the House Committee on Un-American Activities and chaired byMartin Dies Jr

Martin Dies Jr. (November 5, 1900 – November 14, 1972), also known as Martin Dies Sr., was a Texas politician and a Democratic member of the United States House of Representatives. He was elected as a Democrat to the Seventy-second and after ...

. Aiming to discredit the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

by attacking individual projects, Dies claimed that one-third of the Writers' Project's members were Communists. Despite inaccuracies in statements from the committee being widely reported in the press, Alsberg's superiors refused him permission to issue any statements refuting the charges. Alsberg was called to testify before the committee December 6, 1938, after months of requesting a hearing. In Alsberg's testimony, he emphasized his anti-Communist views and stated that he had to "clean up" the Writer's Project, going so far as to threaten to shut it down at the mention of strikes. Unfortunately, these statements reinforced the committee's suspicions that many Communists were part of the project. Within the project, liberals felt Alsberg had been too deferential toward the committee, while conservatives felt the committee had gone too easy on Alsberg. Numerous co-workers said his testimony was brilliant, but Alsberg wanted to resign afterward. Despite Dies's compliments to Alsberg on his testimony, the committee condemned the Writers' Project.

In 1939, Congress cut the WPA budget, and 6,000 were laid off from Federal One. The FWP was then investigated by Clifton Woodrum's House subcommittee on appropriations, which attacked a letter to the editor Alsberg had written ten years previously about conditions in prisons. The Emergency Relief Appropriation Act of 1939 cut funding and required the FWP, now renamed the Writers' Program, to obtain state sponsorship for its projects. The new head of the WPA, Francis C. Harrington, demanded Alsberg's resignation. Alsberg refused to resign immediately, continuing to work on state sponsorships and works in progress. When Alsberg continued working past the August 1 deadline that Harrington set, he was fired. The liberal press was indignant, with ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is a progressive American monthly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper ...

'' writing "The dismissal looks too much like a living sacrifice on the altar of Messrs. Dies and Woodrum and the Red-baiting they represent".

Under Alsberg's leadership, the Writer's Project had produced over 200 books of more than 20 million words. Lewis Mumford

Lewis Mumford (October 19, 1895 – January 26, 1990) was an American historian, sociologist, philosopher of technology, and literary critic. Particularly noted for his study of cities and urban architecture, he had a broad career as a ...

praised the guidebooks as "the finest contribution to American patriotism that has been made in our generation".

Later life

After leaving the Writers' Project, Alsberg went on a speaking tour for the American Association of Colleges, presenting "Adventures in Journalism and Literature". He continued with his political writing, including a piece calling for "an all-out effort to defeat the Axis", and worked on a book that would never be published. In 1942, Alsberg was hired to work at theOffice of War Information

The United States Office of War Information (OWI) was a United States government agency created during World War II. The OWI operated from June 1942 until September 1945. Through radio broadcasts, newspapers, posters, photographs, films and other ...

. Soon after, the Civil Service Commission investigated a claim that Alsberg and a former colleague were involved in an "immoral relationship", which Alsberg denied. In 1943, Dies made a speech in the House of Representatives demanding forty "subversive" employees be fired, naming Alsberg in particular. The Civil Service Commission held a hearing and Alsberg resigned.

Alsberg began work on his book, ''Let's Talk About the Peace'', which would be published after the war in 1945. The book was praised by the ''Chicago Daily Tribune'' and ''The Nation'', however the ''Saturday Review'' noted that the book "does not suffer from intellectual modesty or any moral humility." He also worked with Eugene O'Neill Jr. to establish a Readers Theater

Readers theater is a style of theater in which the actors present dramatic readings of narrative material without costumes, props, scenery, or special lighting. Actors use only scripts and vocal expression to help the audience understand the story. ...

group.

Alsberg took on a project for Hastings House Publishers as editor-in-chief for a one-volume version of the American Guide Series. Alsberg's condensed American Guide series was published in 1949 as ''The American Guide'', and was featured in the Book of the Month Club

Book of the Month (founded 1926) is a United States subscription-based e-commerce service that offers a selection of five to seven new hardcover books each month to its members. Books are selected and endorsed by a panel of judges, and members ch ...

. ''The American Guide'' made ''The New York Times'' best-seller list on October 2, 1949. Alsberg continued as an editor at Hastings House for more than a decade.

Alsberg translated and edited '' Stefan and Friderike Zweig : their correspondence, 1912–1942'' in 1954. In 1956, he moved to Mexico, with occasional visits to Palo Alto, and continued to edit for Hastings House. During this period, he worked on his "Mexican stories" (never published) in which he imagined a social climate that accepted homosexuality.

During the last years of his life, Alsberg, who never married, lived in Palo Alto, California, with his sister Elsa. Alsberg died November 1, 1970, after a short illness.

Some of Alsberg's papers are archived at the libraries at the University of Oregon

The University of Oregon (UO, U of O or Oregon) is a Public university, public research university in Eugene, Oregon, United States. Founded in 1876, the university is organized into nine colleges and schools and offers 420 undergraduate and gra ...

.

Notes

References

* * * * * * *External links

Henry G. Alsberg and Dora Thea Hettwer Collection, Bienes Museum of the Modern Book, Broward County Library.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Alsberg, Henry G 1881 births 1970 deaths 20th-century American journalists American male journalists Jews from New York (state) American people of German-Jewish descent Columbia Law School alumni Writers from Manhattan People of the United States Office of War Information