Haigerloch Research Reactor on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Haigerloch research reactor was a German nuclear research facility. It was built in a rock cellar in Hohenzollerischen Lande,

In 1943, all major German cities were under threat from Allied bombing raids. As a result, it was decided to relocate the KWIP to a more rural area. The suggestion to use the Hohenzollerische Lande for this probably came from the head of the Physics Division in the

In 1943, all major German cities were under threat from Allied bombing raids. As a result, it was decided to relocate the KWIP to a more rural area. The suggestion to use the Hohenzollerische Lande for this probably came from the head of the Physics Division in the

As early as July 29, 1944, the accidentally discovered potato and beer cellar of the Haigerloch Schwanenwirt was rented for 100

As early as July 29, 1944, the accidentally discovered potato and beer cellar of the Haigerloch Schwanenwirt was rented for 100

Once the materials had arrived in Haigerloch, work began immediately on rebuilding the test facility. Von Weizsäcker and Wirtz played a leading role in the construction and experiments. Heisenberg himself managed the project from Hechingen, often cycling back and forth between the two towns. In addition to Bagge and Bopp, other scientists involved in the project on site included Horst Korsching and Erich Fischer.

The outer shell of the reactor consisted of a

Once the materials had arrived in Haigerloch, work began immediately on rebuilding the test facility. Von Weizsäcker and Wirtz played a leading role in the construction and experiments. Heisenberg himself managed the project from Hechingen, often cycling back and forth between the two towns. In addition to Bagge and Bopp, other scientists involved in the project on site included Horst Korsching and Erich Fischer.

The outer shell of the reactor consisted of a

Heisenberg was also present in the cellar during the decisive experiment at the beginning of March 1945, "sitting there and constantly calculating". After the reactor had been closed and the neutron source had been introduced, the heavy water was carefully poured into the inner reactor vessel. The water supply was interrupted at regular intervals and the increase in neutrons was monitored at the probes. By plotting the reciprocal of the measured neutron intensity against the amount of heavy water filled in - an idea of Heisenberg's - the scientists were able to predict the water level at which the reactor would become critical.

However, no criticality occurred, even after all the available heavy water had been filled in. The neutron density in the filled arrangement had increased 6.7-fold compared to the empty measurement. Although this value was twice as high as in the previous experiment, it was still not enough to achieve a self-sustaining

Heisenberg was also present in the cellar during the decisive experiment at the beginning of March 1945, "sitting there and constantly calculating". After the reactor had been closed and the neutron source had been introduced, the heavy water was carefully poured into the inner reactor vessel. The water supply was interrupted at regular intervals and the increase in neutrons was monitored at the probes. By plotting the reciprocal of the measured neutron intensity against the amount of heavy water filled in - an idea of Heisenberg's - the scientists were able to predict the water level at which the reactor would become critical.

However, no criticality occurred, even after all the available heavy water had been filled in. The neutron density in the filled arrangement had increased 6.7-fold compared to the empty measurement. Although this value was twice as high as in the previous experiment, it was still not enough to achieve a self-sustaining

The Allies had long suspected that the German researchers were working on an atomic bomb. The aim of the US special unit Alsos, founded in 1943 as part of the

The Allies had long suspected that the German researchers were working on an atomic bomb. The aim of the US special unit Alsos, founded in 1943 as part of the

The French army arrived in Haigerloch on April 22, 1945, but they did not notice the underground nuclear laboratory. The Alsos mission arrived in the French occupation zone a day later as part of "Operation Harborage", found the apparatus and dismantled it the following day. Only now did the Americans realize that the German research was more than two years behind their own. It now also became apparent to them that the entire German uranium project was on a very small scale compared to the Manhattan Project:

The French army arrived in Haigerloch on April 22, 1945, but they did not notice the underground nuclear laboratory. The Alsos mission arrived in the French occupation zone a day later as part of "Operation Harborage", found the apparatus and dismantled it the following day. Only now did the Americans realize that the German research was more than two years behind their own. It now also became apparent to them that the entire German uranium project was on a very small scale compared to the Manhattan Project:

The German scientists, on the other hand, believed that their work was more advanced than that of the Americans and were initially uncooperative. The uranium cubes and the heavy water had been removed from the facility and well hidden. However, after hours of interrogation, Wirtz and von Weizsäcker were coaxed into revealing the hiding places with the false promise that they would be allowed to resume their experiments after the war under the protection of the Allies.Klaus Hoffmann: ''Schuld und Verantwortung: Otto Hahn, Konflikte eines Wissenschaftlers''. Springer, 1993, , p. 193 659 of the 664 uranium cubes were found buried in a field next to the castle church; the heavy water had been taken to the cellar of an old mill. Von Weizsäcker had hidden the scientific documents, including the top-secret Nuclear physics research reports, in a

The German scientists, on the other hand, believed that their work was more advanced than that of the Americans and were initially uncooperative. The uranium cubes and the heavy water had been removed from the facility and well hidden. However, after hours of interrogation, Wirtz and von Weizsäcker were coaxed into revealing the hiding places with the false promise that they would be allowed to resume their experiments after the war under the protection of the Allies.Klaus Hoffmann: ''Schuld und Verantwortung: Otto Hahn, Konflikte eines Wissenschaftlers''. Springer, 1993, , p. 193 659 of the 664 uranium cubes were found buried in a field next to the castle church; the heavy water had been taken to the cellar of an old mill. Von Weizsäcker had hidden the scientific documents, including the top-secret Nuclear physics research reports, in a

The scientists from the two Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes were arrested by the Americans in their offices and homes in Hechingen and Tailfingen. Heisenberg himself was apprehended a few days later in Urfeld am Walchensee, where he owned a house and spent the last days of the war with his family; Gerlach and Diebner were found in and near

The scientists from the two Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes were arrested by the Americans in their offices and homes in Hechingen and Tailfingen. Heisenberg himself was apprehended a few days later in Urfeld am Walchensee, where he owned a house and spent the last days of the war with his family; Gerlach and Diebner were found in and near

Atomkeller-Museum

City of Haigerloch, retrieved on January 21, 2024 (pictures and background information on the research reactor). * * *

Haigerloch

Haigerloch () is a town in the north-western part of the Swabian Alb in Germany.

Geography Geographical location

Haigerloch lies at between 430 and 550 metres elevation in the valley of the Eyach (Neckar), Eyach river, which forms two loops in a ...

early in 1945 as part of the German nuclear program during World War II

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transformin ...

.

In this last large-scale experiment of the uranium project with the name ''B8'' or B-VIII, as in previous piles, a finite nuclear chain reaction

In nuclear physics, a nuclear chain reaction occurs when one single nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more subsequent nuclear reactions, thus leading to the possibility of a self-propagating series or "positive feedback loop" of thes ...

via neutron source

A neutron source is any device that emits neutrons, irrespective of the mechanism used to produce the neutrons. Neutron sources are used in physics, engineering, medicine, nuclear weapons, petroleum exploration, biology, chemistry, and nuclear p ...

and measured. Natural uranium

Natural uranium (NU or Unat) is uranium with the same isotopic ratio as found in nature. It contains 0.711% uranium-235, 99.284% uranium-238, and a trace of uranium-234 by weight (0.0055%). Approximately 2.2% of its radioactivity comes from ura ...

was used as fuel and heavy water

Heavy water (deuterium oxide, , ) is a form of water (molecule), water in which hydrogen atoms are all deuterium ( or D, also known as ''heavy hydrogen'') rather than the common hydrogen-1 isotope (, also called ''protium'') that makes up most o ...

, graphite

Graphite () is a Crystallinity, crystalline allotrope (form) of the element carbon. It consists of many stacked Layered materials, layers of graphene, typically in excess of hundreds of layers. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable ...

, and light water were used as moderators. The criticality of the chain reaction was not achieved; the plant was also not designed for operation in a critical state, and the term ''reactor'' often used for it today is therefore only applicable to a limited extent. Later calculations showed that the reactor would have had to be about one and a half times the size to become critical.

The American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, p ...

Special Alsos unit found the facility on April 23, 1945, and dismantled it the following day. The scientists involved were captured and the materials used were flown out to the United States. Today, the Atomic Cellar Museum is located at the former site of the reactor.

Previous history

Previous reactor tests

The main objective of the German uranium project during the Second World War was the technical utilization ofnuclear fission

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radioactiv ...

, which had been experimentally researched by Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn (; 8 March 1879 – 28 July 1968) was a German chemist who was a pioneer in the field of radiochemistry. He is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry and discoverer of nuclear fission, the science behind nuclear reactors and ...

and Fritz Straßmann

Friedrich Wilhelm Strassmann (; 22 February 1902 – 22 April 1980) was a German chemist who, with Otto Hahn in December 1938, identified the element barium as a product of the bombardment of uranium with neutrons. Their observation was the key ...

in 1938 and theoretically explained by Lise Meitner

Elise Lise Meitner ( ; ; 7 November 1878 – 27 October 1968) was an Austrian-Swedish nuclear physicist who was instrumental in the discovery of nuclear fission.

After completing her doctoral research in 1906, Meitner became the second woman ...

and Otto Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch (1 October 1904 – 22 September 1979) was an Austrian-born British physicist who worked on nuclear physics. With Otto Stern and Immanuel Estermann, he first measured the magnetic moment of the proton. With his aunt, Lise M ...

. In a series of reactor experiments, known as "large-scale experiments", the aim was to test the theoretical considerations for generating energy from uranium

Uranium is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Ura ...

in practice. For this purpose, natural uranium was bombarded with neutrons

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , that has no electric charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. The neutron was discovered by James Chadwick in 1932, leading to the discovery of nuclear fission in 1938, the f ...

in heavy water

Heavy water (deuterium oxide, , ) is a form of water (molecule), water in which hydrogen atoms are all deuterium ( or D, also known as ''heavy hydrogen'') rather than the common hydrogen-1 isotope (, also called ''protium'') that makes up most o ...

as a moderator and the resulting increase in neutrons was observed. The researchers of the uranium project did not refer to their development goal as a reactor, but as a "uranium machine" or "uranium burner".W. Heisenberg, K. Wirtz:Large-scale tests in preparation for the construction of a uranium burner. In: ''Naturforschung und Medizin in Deutschland 1939–1946. Für Deutschland bestimmte Ausgabe der FIAT Review of German Science'', Vol. 14 Part II (ed. W. Bothe and S. Flügge), Wiesbaden: Dieterich. Also reprinted in: Stadt Haigerloch (ed.): ''Atommuseum Haigerloch'', Self-published, 1982, pp. 43-65.

* Under the direction of the Nobel Prize winner Werner Heisenberg

Werner Karl Heisenberg (; ; 5 December 1901 – 1 February 1976) was a German theoretical physicist, one of the main pioneers of the theory of quantum mechanics and a principal scientist in the German nuclear program during World War II.

He pub ...

, a total of seven large-scale experiments called ''B1'' to ''B7'' were carried out at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics

The Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science () was a German scientific institution established in the German Empire in 1911. Its functions were taken over by the Max Planck Society. The Kaiser Wilhelm Society was an umbrella organi ...

(KWIP) in Berlin-Dahlem

Dahlem ( or ) is a locality of the Steglitz-Zehlendorf borough in southwestern Berlin. Until Berlin's 2001 administrative reform it was a part of the former borough of Zehlendorf. It is located between the mansion settlements of Grunewald and ...

from 1941 to 1944. The physicists investigated the reactivity of plates of uranium metal of various thicknesses with increasing success.

* At a second location, the Physics Institute of the University of Leipzig

Leipzig University (), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 December 1409 by Frederick I, Electo ...

, four further experiments ''L-I'' to ''L-IV'' with concentrically arranged layers of uranium powder and heavy water were carried out by Heisenberg and his colleagues in 1941 and 1942. In experiment L-IV, when neutron multiplication had already been detected, the uranium powder ignited after the formation of an oxyhydrogen gas and the entire facility burned. No persons were injured. The event represents - sensu lato

''Sensu'' is a Latin word meaning "in the sense of". It is used in a number of fields including biology, geology, linguistics, semiotics, and law. Commonly it refers to how strictly or loosely an expression is used in describing any particular co ...

- the first recorded "reactor accident" in history - years before the commercial use of nuclear fission was even conceivable. The experiments in Leipzig were discontinued and only compact metallic uranium was used from then on.

* At the same time, another group was working on similar experiments at the Gottow Experimental Station near Berlin under the direction of Kurt Diebner

Kurt Diebner (13 May 1905 – 13 July 1964) was a German nuclear physicist who is well known for directing and administering parts of the German nuclear weapons program, a secretive program aiming to build nuclear weapons for Nazi Germany during ...

. In their three experiments ''G1'' to ''G3'' in 1942 and 1943, uranium cubes were used instead of plates with good results; in addition to heavy water, kerosene

Kerosene, or paraffin, is a combustibility, combustible hydrocarbon liquid which is derived from petroleum. It is widely used as a fuel in Aviation fuel, aviation as well as households. Its name derives from the Greek (''kērós'') meaning " ...

was also used as a moderator. The Heisenberg and Diebner groups competed for the scarce materials. In kerosene wax, both the hydrogen and the carbon of the hydrocarbon

In organic chemistry, a hydrocarbon is an organic compound consisting entirely of hydrogen and carbon. Hydrocarbons are examples of group 14 hydrides. Hydrocarbons are generally colourless and Hydrophobe, hydrophobic; their odor is usually fain ...

s it contains act as moderators. Even today, neutrons from smaller neutron source

A neutron source is any device that emits neutrons, irrespective of the mechanism used to produce the neutrons. Neutron sources are used in physics, engineering, medicine, nuclear weapons, petroleum exploration, biology, chemistry, and nuclear p ...

s are often slowed down with kerosene. However, attempts to cool/moderate nuclear reactors with organic substances have not yet progressed beyond the experimental stage.

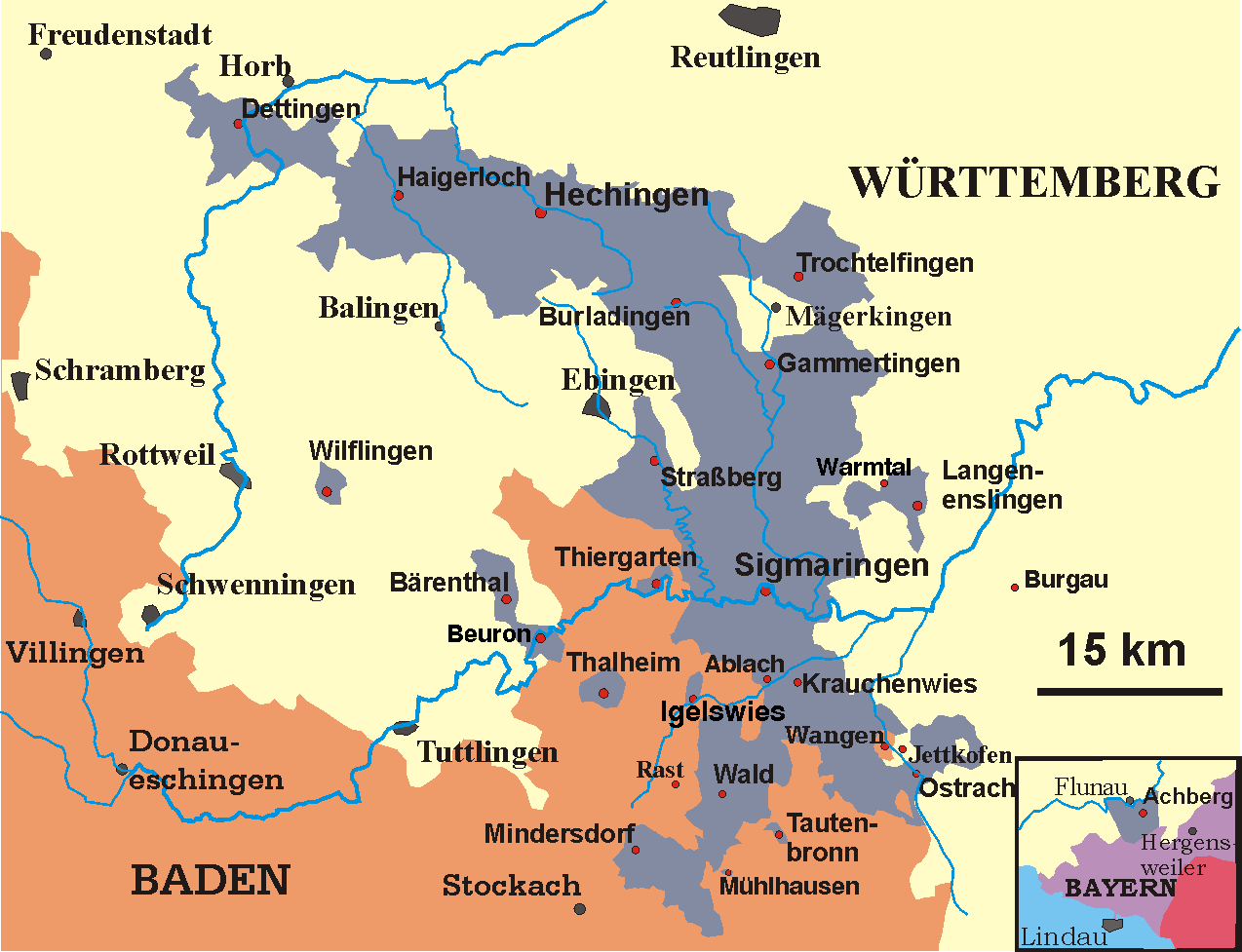

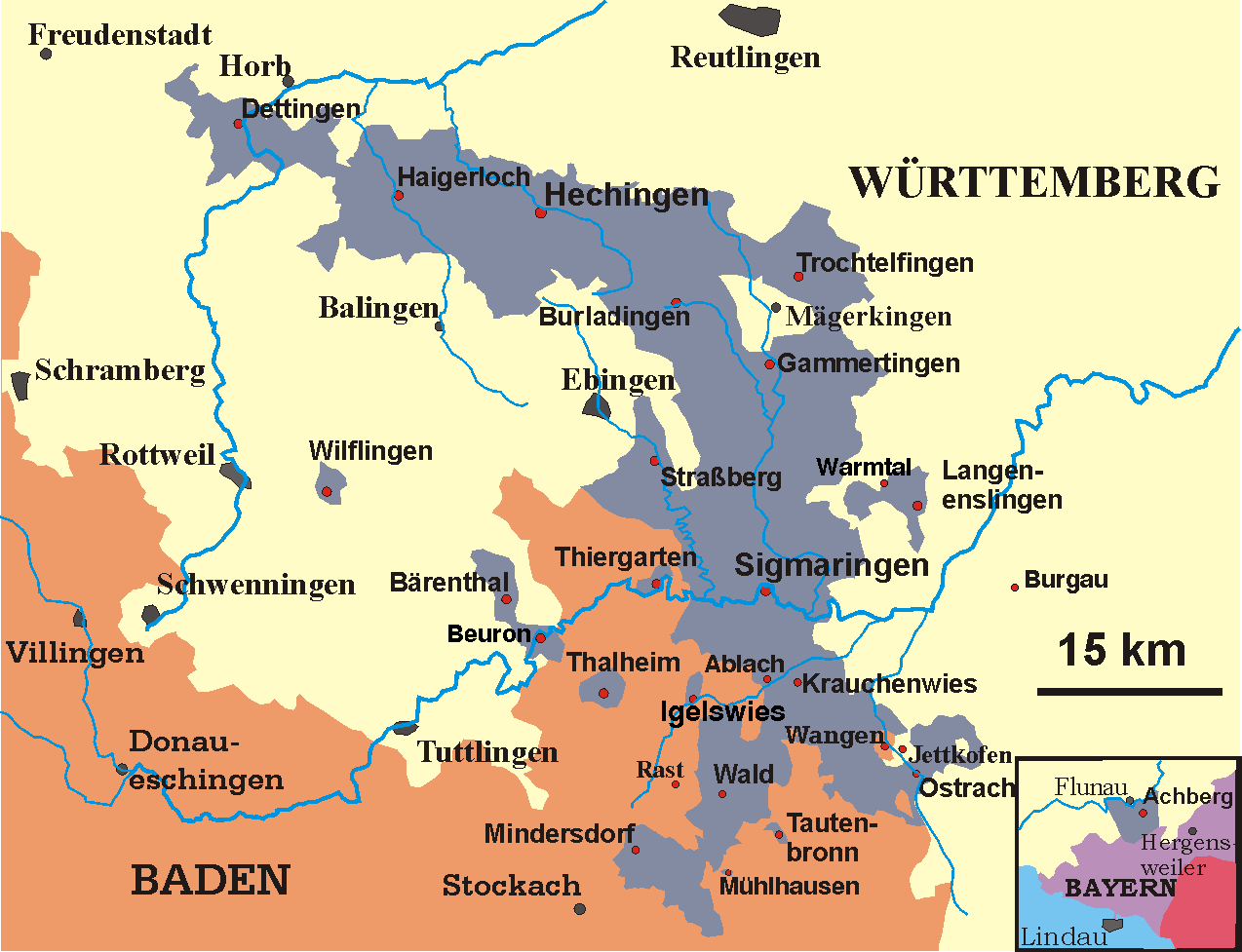

Relocation of research

In 1943, all major German cities were under threat from Allied bombing raids. As a result, it was decided to relocate the KWIP to a more rural area. The suggestion to use the Hohenzollerische Lande for this probably came from the head of the Physics Division in the

In 1943, all major German cities were under threat from Allied bombing raids. As a result, it was decided to relocate the KWIP to a more rural area. The suggestion to use the Hohenzollerische Lande for this probably came from the head of the Physics Division in the Reichsforschungsrat The Reichsforschungsrat ("Imperial Research Council") was created in Germany in 1936 under the Education Ministry for the purpose of centralized planning of all basic and applied research, with the exception of aeronautical research. It was reorgani ...

, Walther Gerlach

Walther Gerlach (1 August 1889 – 10 August 1979) was a German physicist who co-discovered, through laboratory experiment, spin quantization in a magnetic field, the Stern–Gerlach effect. The experiment was conceived by Otto Stern in 1921 an ...

, who had studied at the University of Tübingen

The University of Tübingen, officially the Eberhard Karl University of Tübingen (; ), is a public research university located in the city of Tübingen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

The University of Tübingen is one of eleven German Excellenc ...

and was a professor there in the late 1920s, making him familiar with the area. Another reason for selecting southern Germany was that it had been largely spared from air raids up until then. Additionally, the scientists involved favored this location to avoid the risk of being captured by the Soviets in the event of defeat.Dahl: ''Heavy Water and the Wartime Race for Nuclear Energy'', p. 254.

Subsequently, the KWIP was relocated to Hechingen

Hechingen (; Swabian: ''Hächenga'') is a town in central Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is situated about south of the state capital of Stuttgart and north of Lake Constance and the Swiss border.

Geography

The town lies at the foot of th ...

, approximately 15 km from Haigerloch. It was housed in the Grotz and Conzelmann textile factories and in the brewery building of the former Franciscan Monastery of St. Luzen. The relocation occurred in stages: by the end of 1943, about a third of the institute moved to Hechingen, with Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker

Carl Friedrich Freiherr von Weizsäcker (; 28 June 1912 – 28 April 2007) was a German physicist and philosopher. He was the longest-living member of the team which performed nuclear research in Nazi Germany during the Second World War, un ...

and Karl-Heinz Höcker from Strasbourg

Strasbourg ( , ; ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est Regions of France, region of Geography of France, eastern France, in the historic region of Alsace. It is the prefecture of the Bas-Rhin Departmen ...

joining in 1944, and finally Heisenberg relocating there. At the same time, the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry

The Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science () was a German scientific institution established in the German Empire in 1911. Its functions were taken over by the Max Planck Society. The Kaiser Wilhelm Society was an umbrella organi ...

, was relocated to nearby Tailfingen (now part of Albstadt

Albstadt () is the largest city in the district of Zollernalbkreis in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is located on the Swabian Jura mountains, about halfway between Stuttgart and Lake Constance.

Geography

Albstadt is spread across a variety of ...

), with prominent scientists such as Otto Hahn and Max von Laue

Max Theodor Felix von Laue (; 9 October 1879 – 24 April 1960) was a German physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1914 "for his discovery of the X-ray diffraction, diffraction of X-rays by crystals".

In addition to his scientifi ...

involved in the move.

By January 1945, only Karl Wirtz

Karl Eugen Julius Wirtz (24 April 1910 – 12 February 1994) was a German nuclear physicist, born in Cologne. He was arrested by the allied British and American Armed Forces and incarcerated at Farm Hall for six months in 1945 under Operation E ...

, Kurt Diebner

Kurt Diebner (13 May 1905 – 13 July 1964) was a German nuclear physicist who is well known for directing and administering parts of the German nuclear weapons program, a secretive program aiming to build nuclear weapons for Nazi Germany during ...

, and a few technicians remained in Berlin from the Uranverein

Nazi Germany undertook several research programs relating to nuclear technology, including nuclear weapons and nuclear reactors, before and during World War II. These were variously called () or (). The first effort started in April 1939, ju ...

. Wirtz was setting up the largest German reactor test to date in the still-intact Dahlem institute bunker when the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

advanced to within 80 km of Berlin. As a result, Gerlach decided on January 27, 1945, to abandon the almost completed test setup. He immediately traveled to Berlin to evacuate the scientists and materials to southern Germany.

Preparations

The Felsenkeller

As early as July 29, 1944, the accidentally discovered potato and beer cellar of the Haigerloch Schwanenwirt was rented for 100

As early as July 29, 1944, the accidentally discovered potato and beer cellar of the Haigerloch Schwanenwirt was rented for 100 Reichsmark

The (; sign: ℛ︁ℳ︁; abbreviation: RM) was the currency of Germany from 1924 until the fall of Nazi Germany in 1945, and in the American, British and French occupied zones of Germany, until 20 June 1948. The Reichsmark was then replace ...

per month as the new location of the Berlin research reactor

Research reactors are nuclear fission-based nuclear reactors that serve primarily as a neutron source. They are also called non-power reactors, in contrast to power reactors that are used for electricity production, heat generation, or maritim ...

. The Felsenkeller (rock cellar) was built at the beginning of the 20th century for a tunnel for the Hohenzollerische Landesbahn

The Hohenzollerische Landesbahn (HzL) was the largest non-federally owned railway company in the German state of Baden-Württemberg after the Albtal-Verkehrs-Gesellschaft and Südwestdeutsche Verkehrs-Aktiengesellschaft. It operated passenger an ...

. In the narrow Eyachtal valley, it was driven into the mountain under the Schlosskirche (castle church) there and protected against bomb attacks by a 2030m thick layer of rock made of shell limestone.Dahl: ''Heavy Water and the Wartime Race for Nuclear Energy'', p. 255.

The approximately 20-metre-long and approximately three-metre-high tunnel section had a trapezoidal cross-section, with the ceiling about four meters wide and the floor about five meters wide. The tunnel was supported along its entire length by wooden support beams, which were placed two meters apart. A small two-part porch concealed the entrance.

A three-meter-deep cylindrical pit was excavated for the reactor in the rear part of the rock cellar, a transport crane was installed on the cellar ceiling and an diesel generator

A diesel generator (DG) (also known as a diesel genset) is the combination of a diesel engine with an electric generator (often an alternator) to generate electrical energy. This is a specific case of an engine generator. A diesel compress ...

was set up in the abandoned beer house on the opposite side of the street. By the end of 1944, the conversion work in the rock cellar, which was disguised as a "cave research station", had progressed so far that the construction of the reactor could begin there.

Transportation of materials

On January 31, 1945, Gerlach, Wirtz and Diebner left the capital at the head of a small convoy (road transport). They were followed by severaltrucks

A truck or lorry is a motor vehicle designed to transport freight, carry specialized payloads, or perform other utilitarian work. Trucks vary greatly in size, power, and configuration, but the vast majority feature body-on-frame construction ...

loaded with several tons of heavy water, uranium, graphite

Graphite () is a Crystallinity, crystalline allotrope (form) of the element carbon. It consists of many stacked Layered materials, layers of graphene, typically in excess of hundreds of layers. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable ...

and technical equipment. After a night-time journey on an icy freeway

A controlled-access highway is a type of highway that has been designed for high-speed vehicular traffic, with all traffic flow—ingress and egress—regulated. Common English terms are freeway, motorway, and expressway. Other similar terms ...

, the convoy stopped the following day about 240 kilometers south of Berlin in Thuringia

Thuringia (; officially the Free State of Thuringia, ) is one of Germany, Germany's 16 States of Germany, states. With 2.1 million people, it is 12th-largest by population, and with 16,171 square kilometers, it is 11th-largest in area.

Er ...

Stadtilm, where Diebner's working group had been relocated the previous summer. Gerlach believed that Diebner's laboratory was more advanced than Heisenberg's and decided without further ado to unload the materials there. Very annoyed at the change of plan, Wirtz contacted Heisenberg in Hechingen

Hechingen (; Swabian: ''Hächenga'') is a town in central Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is situated about south of the state capital of Stuttgart and north of Lake Constance and the Swiss border.

Geography

The town lies at the foot of th ...

, who immediately set off for Stadtilm together with von Weizsäcker and arrived there three days later after an adventurous journey by bicycle, train and car.Dahl: ''Heavy Water and the Wartime Race for Nuclear Energy'', p. 256.

On site, Heisenberg tried to convince Gerlach to take the materials to Haigerloch after all. The two went to Hohenzollern on February 12, 1945 to inspect the situation on site. Wirtz, meanwhile, remained in Stadtilm to ensure that the materials were not used in Diebner's experiments. After Gerlach had ascertained in Haigerloch that the Felsenkeller was better suited as a new location for the reactor, he agreed to the relocation again. Trucks were again procured and on February 23, 1945, the physicist Erich Bagge set off from Haigerloch with a new convoy to collect the materials from their storage site in Stadtilm.

Four weeks after leaving Berlin, 1.5 tons of uranium, 1.5 tons of heavy water, 10 tons of graphite and a small amount of cadmium

Cadmium is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Cd and atomic number 48. This soft, silvery-white metal is chemically similar to the two other stable metals in group 12 element, group 12, zinc and mercury (element), mercury. Like z ...

finally arrived in Haigerloch at the end of February 1945. The uranium had been mined in Sankt Joachimsthal in the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and ) is a German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the border districts of Bohe ...

and came from the German Degussa. The heavy water had been produced by Norsk Hydro

Norsk Hydro ASA (often referred to as just ''Hydro'') is a Norway, Norwegian aluminium and renewable energy company, headquartered in Oslo. It is one of the largest aluminium companies worldwide. It has operations in some 50 countries around th ...

in Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

. In addition, the physicist Fritz Bopp

Friedrich Arnold "Fritz" Bopp (27 December 1909 – 14 November 1987) was a German theoretical physicist who contributed to nuclear physics and quantum field theory. He worked at the '' Kaiser-Wilhelm Institut für Physik'' and with the ''Uranver ...

from Berlin had flown in a 500 milligram radium

Radium is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Ra and atomic number 88. It is the sixth element in alkaline earth metal, group 2 of the periodic table, also known as the alkaline earth metals. Pure radium is silvery-white, ...

beryllium

Beryllium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Be and atomic number 4. It is a steel-gray, hard, strong, lightweight and brittle alkaline earth metal. It is a divalent element that occurs naturally only in combination with ...

sample as a neutron source. Over ten tons of uranium oxide as well as small quantities of uranium metal and heavy water remained at Diebner in Stadtilm.

The research reactor

The system

concrete

Concrete is a composite material composed of aggregate bound together with a fluid cement that cures to a solid over time. It is the second-most-used substance (after water), the most–widely used building material, and the most-manufactur ...

cylinder into which a boiler made of aluminum

Aluminium (or aluminum in North American English) is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Al and atomic number 13. It has a density lower than that of other common metals, about one-third that of steel. Aluminium has ...

with a diameter of 210.8 centimeters and a height of 216 centimeters was inserted. The aluminum boiler rested on wooden support beams on the floor, and the space in between was filled with normal water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

. Another boiler made of a very light magnesium

Magnesium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a shiny gray metal having a low density, low melting point and high chemical reactivity. Like the other alkaline earth metals (group 2 ...

alloy

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements of which in most cases at least one is a metal, metallic element, although it is also sometimes used for mixtures of elements; herein only metallic alloys are described. Metallic alloys often have prop ...

with a diameter of 124 centimetres and the same height was inserted into the aluminum boiler. The magnesium boiler had already been used in the large-scale test ''B6'', the aluminum boiler had been used for the first time in the large-scale test ''B7''. Both boilers were manufactured by the Berlin company Bamag-Meguin.Dahl: ''Heavy Water and the Wartime Race for Nuclear Energy'', S. 257.

Between the two boilers was a 43-centimetre-thick and 10-ton layer of graphite

Graphite () is a Crystallinity, crystalline allotrope (form) of the element carbon. It consists of many stacked Layered materials, layers of graphene, typically in excess of hundreds of layers. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable ...

, which served as a neutron reflector and shielding. Graphite had been used as a reflector for the first time in the previous large-scale experiment ''B7''; it had not been used in even earlier experiments because the neutron absorption in graphite had been estimated too high by Walther Bothe

Walther Wilhelm Georg Bothe (; 8 January 1891 – 8 February 1957) was a German physicist who shared the 1954 Nobel Prize in Physics with Max Born "for the coincidence method and his discoveries made therewith".

He served in the military durin ...

in 1941. The lid of the inner boiler consisted of two magnesium plates, between which there was also a graphite layer.

A total of 664 cubes made of natural uranium with an edge length of five centimetres and a weight of 2.4 kilograms each were attached to this lid using 78 aluminum wires. 40 wires held nine cubes each, the remaining 38 wires held eight cubes each.Klaus Hentschel, Ann. M. Hentschel: Physics and national socialism: an anthology of primary sources. Birkhäuser, 1996, , p. 377 The uranium cubes with a total weight of 1.58 tons were lowered into the inner vessel with the help of the crane, and the entire arrangement was sealed with the lid. In the resulting cubic face-centered lattice, the uranium cubes were arranged in the corners and in the centers of the faces of an imaginary space cube. The uranium cubes were spaced 14 centimeters apart.

The scheme with the staggered uranium cubes was first used by Diebner in 1943 in the large-scale test ''G3'' at the test facility of the Army Weapons Office in Gottow. Uranium plates had previously been used in the Berlin experiments, but with poorer results. Originally, the physicists wanted to test a construction made of suspended uranium cylinders, comparable to today's fuel rods. However, there was no longer enough time to produce such cylinders and the researchers therefore decided to copy Diebner's design. Ideally, the cubes should have had an edge length of between six and seven centimeters, but the scientists had to use the smaller cubes from Diebner's last experiments and therefore cut the uranium plates to the same size.

The radium-beryllium neutron source

A neutron source is any device that emits neutrons, irrespective of the mechanism used to produce the neutrons. Neutron sources are used in physics, engineering, medicine, nuclear weapons, petroleum exploration, biology, chemistry, and nuclear p ...

could be introduced into the center of the reactor through a so-called chimney. During the following experiment, the heavy water, which was stored in three large tanks at the end of the tunnel, was also filled into the inner reactor vessel through the chimney. There were also channels in the lid through which neutron detector

Neutron detection is the effective detection of neutrons entering a well-positioned detector. There are two key aspects to effective neutron detection: hardware and software. Detection hardware refers to the kind of neutron detector used (the mos ...

s were inserted. This made it possible to measure the spatial neutron distribution in the entire arrangement by utilizing the cylindrical symmetry. The construction work on the reactor was completed in the first week of March 1945.Dahl: ''Heavy Water and the Wartime Race for Nuclear Energy'', p. 258.

Aims of the experiment

In the large-scale experiment ''B8'', a nuclear fission chain reaction was to be induced and observed by bombarding uranium with neutrons. The Haigerloch experiments were basic research. Their purpose was to determine the associatednuclear physics

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies atomic nuclei and their constituents and interactions, in addition to the study of other forms of nuclear matter.

Nuclear physics should not be confused with atomic physics, which studies th ...

parameters, such as cross section

Cross section may refer to:

* Cross section (geometry)

** Cross-sectional views in architecture and engineering 3D

*Cross section (geology)

* Cross section (electronics)

* Radar cross section, measure of detectability

* Cross section (physics)

**A ...

s, as far as possible from the measurements. These findings were necessary for peaceful uses of nuclear fission, but were also at least helpful for military applications. At least some of those involved also hoped to achieve criticality of the facility and thus - supposedly for the first time - demonstrate a ''self-sustaining'' fission chain reaction. They could not have known that Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian and naturalized American physicist, renowned for being the creator of the world's first artificial nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1, and a member of the Manhattan Project ...

and his colleagues had already succeeded in December 1942 at the Chicago Pile 1 nuclear reactor in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

.

However, the system had no facilities for regulating a critical state and switching it off again. There were no control rods

Control rods are used in nuclear reactors to control the rate of fission of the nuclear fuel – uranium or plutonium. Their compositions include chemical elements such as boron, cadmium, silver, hafnium, or indium, that are capable of absorbing ...

, nor was there any way of quickly draining the heavy water once it had been filled in. If the measured neutron flux

The neutron flux is a scalar quantity used in nuclear physics and nuclear reactor physics. It is the total distance travelled by all free neutrons per unit time and volume. Equivalently, it can be defined as the number of neutrons travelling ...

density and thus the nuclear reaction rate

In nuclear physics and nuclear chemistry, a nuclear reaction is a process in which two nuclei, or a nucleus and an external subatomic particle, collide to produce one or more new nuclides. Thus, a nuclear reaction must cause a transformation o ...

had increased too much, the plan was to abort the experiment before criticality was reached by quickly withdrawing the neutron source and stopping the heavy water supply. The Doppler coefficient, which would have automatically reduced the neutron multiplication as the temperature increased, was relied upon to limit the power in the event of criticality. If, contrary to all expectations, the plant had gotten out of control, the cadmium piece, which acted as a neutron absorber

In applications such as nuclear reactors, a neutron poison (also called a neutron absorber or a nuclear poison) is a substance with a large neutron absorption cross-section. In such applications, absorbing neutrons is normally an undesirable ef ...

, would have been thrown into the reactor through the chimney, thus interrupting the chain reaction. However, even with a very high neutron multiplication of the subcritical arrangement, the physicists would have been exposed to a high radiation dose, because the plant did not have sufficient radiation shielding at the top.

The participants were aware of the possibility of the military use of their work, as Heisenberg had already informed the Heereswaffenamt

(WaA) was the German Army Weapons Agency. It was the centre for research and development of the Weimar Republic and later the Third Reich for weapons, ammunition and army equipment to the German Reichswehr and then Wehrmacht

The ''Wehr ...

at the end of 1939 that uranium-235 must be a powerful nuclear explosive

A nuclear explosive is an explosive device that derives its energy from nuclear reactions. Almost all nuclear explosive devices that have been designed and produced are nuclear weapons intended for warfare.

Other, non-warfare, applications for nu ...

. Von Weizsäcker had also pointed out its usability as a weapon early on, as well as the fact that a new fissile element - later known as plutonium

Plutonium is a chemical element; it has symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is a silvery-gray actinide metal that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibits six allotropes and four ...

- would have to be created in uranium reactors. In principle, the Haigerloch tests could have confirmed these assumptions, but the scientists were also aware that many years of extensive research would have been necessary to develop operational weapons.

The large-scale test''B8''

nuclear chain reaction

In nuclear physics, a nuclear chain reaction occurs when one single nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more subsequent nuclear reactions, thus leading to the possibility of a self-propagating series or "positive feedback loop" of thes ...

. The neutron multiplication factor was ''k''=0.85; the criticality would have been ''k''=1. Later calculations showed that the plant would have had to be about one and a half times the size to become critical.

However, it was not possible to expand the facility under the given circumstances, as there was neither time nor sufficient additional uranium and heavy water available. The heavy water factory of Norsk Hydro

Norsk Hydro ASA (often referred to as just ''Hydro'') is a Norway, Norwegian aluminium and renewable energy company, headquartered in Oslo. It is one of the largest aluminium companies worldwide. It has operations in some 50 countries around th ...

in Rjukan

Rjukan () is a List of towns and cities in Norway, town in Tinn Municipality in Telemark county, Norway. The town is also the administrative centre of Tinn Municipality. The town is located in the Vestfjorddalen valley, between the lakes Møsvatn ...

had already been destroyed by British bombers

A bomber is a military combat aircraft that utilizes

air-to-ground weaponry to drop bombs, launch torpedoes, or deploy air-launched cruise missiles.

There are two major classifications of bomber: strategic and tactical. Strategic bombing is ...

in November 1943, and in September 1944 the Degussa works in Frankfurt am Main

Frankfurt am Main () is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 773,068 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the List of cities in Germany by population, fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located in the forela ...

had also been badly hit by a bomber detachment.

In a final attempt to make the reactor critical after all, Heisenberg wanted to transport the remaining heavy water and uranium that was left in Stadtilm to Haigerloch. He also wanted to throw all theory to the wind and introduce uranium oxide into the graphite shield. During the last measurements, Wirtz had discovered that graphite was a better moderator than previously assumed. However, they were no longer able to establish contact with Stadtilm in the now collapsing German communications network.

More precise details about the plant and the course of the experiment can no longer be determined today, as the original reportName des Originalberichts: F. Bopp, E. Fischer, W. Heisenberg, K. Wirtz, W. Bothe, P. Jensen und O. Ritter. ''Bericht über den Versuch B8 in Haigerloch.'' is no longer available among the Group's documents subsequently brought to the USA. However, a thorough overall description of all eight large-scale experiments written by Heisenberg and Wirtz later, probably around 1950, does exist. A later analysis of two uranium cube fragments from Haigerloch by the Institute for Transuranium Elements

The Institute for Transuranium Elements (ITU) is a nuclear research institute in Karlsruhe, Germany. The ITU is one of the seven institutes of the Joint Research Centre, a Directorate-General of the European Commission. The ITU has about 300 sta ...

at the Karlsruhe Research Center revealed that the uranium had only been irradiated with relatively few neutrons; plutonium could not be detected.

This indicates that the researchers were not on the verge of a nuclear chain reaction. They were still a long way from being able to produce a nuclear weapon.

Persecution and destruction

The Alsos mission

The Allies had long suspected that the German researchers were working on an atomic bomb. The aim of the US special unit Alsos, founded in 1943 as part of the

The Allies had long suspected that the German researchers were working on an atomic bomb. The aim of the US special unit Alsos, founded in 1943 as part of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

under General Leslie R. Groves, was to expose and secure the German nuclear research facilities and to capture the leading scientists. The aim was not only to advance Germany's own nuclear weapons program, but also to prevent the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and the other later occupying forces from using the knowledge. The military head of the mission was Lieutenant Colonel Boris Pash

Boris Theodore Pash (20 June 1900 – 11 May 1995; born Boris Fyodorovich Pashkovsky) was a United States Army military intelligence officer. He commanded the Alsos Mission during World War II and retired with the rank of colonel.

Early life

Bo ...

, the scientific team was led by the Dutch-born physicist Samuel Goudsmit

Samuel Abraham Goudsmit (July 11, 1902 – December 4, 1978) was a Dutch-American physicist famous for jointly proposing the concept of electron spin with George Eugene Uhlenbeck in 1925.

Life and career

Goudsmit was born in The Hague, Ne ...

.

The Americans did not know exactly how far German research had progressed until the end of 1944. The Alsos I mission in the winter of 1943/44 in Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

had been largely unsuccessful. It was not until the end of November 1944, during the Alsos II mission in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, that Weizsäcker's office at the University of Strasbourg

The University of Strasbourg (, Unistra) is a public research university located in Strasbourg, France, with over 52,000 students and 3,300 researchers. Founded in the 16th century by Johannes Sturm, it was a center of intellectual life during ...

University of Strasbourg

The University of Strasbourg (, Unistra) is a public research university located in Strasbourg, France, with over 52,000 students and 3,300 researchers. Founded in the 16th century by Johannes Sturm, it was a center of intellectual life during ...

, letters from other members of the Uranium Association were found from which it could be concluded that Germany did not have an atomic bomb and would not produce one in the foreseeable future. However, documents were also discovered that pointed to a suspicious research laboratory in the future French occupation zone

The French occupation zone in Germany (, ) was one of the Allied-occupied areas in Germany after World War II.

Background

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin met at the Yalta C ...

in Hechingen. In order to get ahead of the French troops, Groves and Pash considered attacking the facility from the air with paratroopers

A paratrooper or military parachutist is a soldier trained to conduct military operations by parachuting directly into an area of operations, usually as part of a large airborne forces unit. Traditionally paratroopers fight only as light inf ...

or destroying it with bombing raids. However, the physicist Goudsmit was able to convince them that the uranium project was not worth the effort, and so they decided on a land operation.

The first special units of the Alsos III mission crossed the Rhine

The Rhine ( ) is one of the List of rivers of Europe, major rivers in Europe. The river begins in the Swiss canton of Graubünden in the southeastern Swiss Alps. It forms part of the Swiss-Liechtenstein border, then part of the Austria–Swit ...

together with the 7th US Army on March 26, 1945. On March 30, 1945, they were able to pick up the physicists Walther Bothe and Wolfgang Gentner

Wolfgang Gentner (23 July 1906 in Frankfurt am Main – 4 September 1980 in Heidelberg) was a German experimental nuclear physicist.

Gentner received his doctorate in 1930 from the University of Frankfurt. From 1932 to 1935 he had a fellowship wh ...

in Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; ; ) is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, fifth-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, and with a population of about 163,000, of which roughly a quarter consists of studen ...

, who were working there on their cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: Januar ...

. There, Goudsmit learned that the nuclear research facilities of the uranium project had been relocated to Haigerloch near Hechingen and to Stadtilm in the future Soviet occupation zone

The Soviet occupation zone in Germany ( or , ; ) was an area of Germany that was occupied by the Soviet Union as a communist area, established as a result of the Potsdam Agreement on 2 August 1945. On 7 October 1949 the German Democratic Republ ...

. Pash decided to go to Stadtilm first to get ahead of the Soviet army. They managed to arrive there about three weeks before the Soviet forces, but Diebner had already fled with his employees and materials towards Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

in the future American occupation zone. Now they only had to prevent the Haigerloch reactor from falling into French hands.Dahl: ''Heavy Water and the Wartime Race for Nuclear Energy'', p. 259.

The destruction of the plant

The French army arrived in Haigerloch on April 22, 1945, but they did not notice the underground nuclear laboratory. The Alsos mission arrived in the French occupation zone a day later as part of "Operation Harborage", found the apparatus and dismantled it the following day. Only now did the Americans realize that the German research was more than two years behind their own. It now also became apparent to them that the entire German uranium project was on a very small scale compared to the Manhattan Project:

The French army arrived in Haigerloch on April 22, 1945, but they did not notice the underground nuclear laboratory. The Alsos mission arrived in the French occupation zone a day later as part of "Operation Harborage", found the apparatus and dismantled it the following day. Only now did the Americans realize that the German research was more than two years behind their own. It now also became apparent to them that the entire German uranium project was on a very small scale compared to the Manhattan Project:

The German scientists, on the other hand, believed that their work was more advanced than that of the Americans and were initially uncooperative. The uranium cubes and the heavy water had been removed from the facility and well hidden. However, after hours of interrogation, Wirtz and von Weizsäcker were coaxed into revealing the hiding places with the false promise that they would be allowed to resume their experiments after the war under the protection of the Allies.Klaus Hoffmann: ''Schuld und Verantwortung: Otto Hahn, Konflikte eines Wissenschaftlers''. Springer, 1993, , p. 193 659 of the 664 uranium cubes were found buried in a field next to the castle church; the heavy water had been taken to the cellar of an old mill. Von Weizsäcker had hidden the scientific documents, including the top-secret Nuclear physics research reports, in a

The German scientists, on the other hand, believed that their work was more advanced than that of the Americans and were initially uncooperative. The uranium cubes and the heavy water had been removed from the facility and well hidden. However, after hours of interrogation, Wirtz and von Weizsäcker were coaxed into revealing the hiding places with the false promise that they would be allowed to resume their experiments after the war under the protection of the Allies.Klaus Hoffmann: ''Schuld und Verantwortung: Otto Hahn, Konflikte eines Wissenschaftlers''. Springer, 1993, , p. 193 659 of the 664 uranium cubes were found buried in a field next to the castle church; the heavy water had been taken to the cellar of an old mill. Von Weizsäcker had hidden the scientific documents, including the top-secret Nuclear physics research reports, in a cesspit

Cesspit, cesspool and soak pit in some contexts are terms with various meanings: they are used to describe either an underground holding tank (sealed at the bottom) or a Dry well, soak pit (not sealed at the bottom). A cesspit can be used for ...

behind his house in Hechingen.Dahl: ''Heavy Water and the Wartime Race for Nuclear Energy'', p. 262.

The materials and scientific reports were seized by the Americans and flown to the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

via Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

. The parts of the reactor plant that could not be removed were destroyed by several small blasts. A larger blast in the rock cellar would probably have severely damaged the baroque castle church above. The parish priest at the time was able to prevent this by showing the church to the Americans and convincing Pash to only carry out smaller blasts.

A French task force led by the physicist Yves Rocard

Yves-André Rocard (; 22 May 1903 – 16 March 1992) was a French physicist who helped develop the atomic bomb for France.

Lifes

Rocard was born in Vannes. After obtaining a double doctorate in mathematics (1927) and physics (1928) he was aw ...

, which arrived in Hechingen shortly after the US troops in search of the facility, found only a piece of uranium from a laboratory the size of a sugar cube. Nevertheless, parts from the Haigerloch research reactor, such as the high-purity graphite bricks, are said to have been reused in the first French nuclear reactor ZOÉ.

Consequences

Further developments

The scientists from the two Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes were arrested by the Americans in their offices and homes in Hechingen and Tailfingen. Heisenberg himself was apprehended a few days later in Urfeld am Walchensee, where he owned a house and spent the last days of the war with his family; Gerlach and Diebner were found in and near

The scientists from the two Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes were arrested by the Americans in their offices and homes in Hechingen and Tailfingen. Heisenberg himself was apprehended a few days later in Urfeld am Walchensee, where he owned a house and spent the last days of the war with his family; Gerlach and Diebner were found in and near Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

. The ten leading figures of the uranium project (Bagge, Diebner, Gerlach, Hahn, Heisenberg, Korsching, von Laue, von Weizsäcker and Wirtz, plus the physicist Paul Harteck

Paul Karl Maria Harteck (20 July 190222 January 1985) was an Austrian physical chemist. In 1945 under Operation Epsilon in "the big sweep" throughout Germany, Harteck was arrested by the allied British and American Armed Forces for suspicion of ...

) were interned in Operation Epsilon

Operation Epsilon was the codename of a program in which Allies of World War II, Allied forces near the end of World War II detained ten Germany, German scientists who were thought to have worked on German nuclear energy project, Nazi Germany's n ...

from July 1945 to January 1946 in British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

Farm Hall from July 1945 to January 1946. There, in August 1945, they learned of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and thus also of the progress made by the Americans in nuclear technology and its consequences. The German scientists were deeply shocked, but at the same time relieved:

After their internment, the ten researchers returned home, where - with the exception of Diebner - they were able to take up respected positions in the scientific community. Although the Control Council Law No. 25 prohibited Germany from pursuing further development of a nuclear reactor in the post-war years, Heisenberg was already thinking about a German reactor again in 1950.

It was not until 1957 that the first nuclear reactor on German soil, the Munich Research Reactor, went into operation. In the same year, most members of the Uranium Project, together with other leading German nuclear physicists, spoke out against the military use of nuclear energy in Germany in the Göttinger Manifesto.

Today, the Atomic Cellar Museum, which opened in 1980, is located in the rock cellar and houses a replica of the reactor as well as two of the five remaining uranium cubes. One of the two cubes was taken by Heisenberg and found by children playing in the Loisach

The Loisach is a river that flows through Tyrol, Austria and Bavaria, Germany. The Loisach runs through the great moors and

The Loisach is a left tributary to the Isar whose source is near Ehrwald in Austria. It flows past Garmisch-Partenkirc ...

river near his home in the early 1960s.

Further processing of events

The two-part German television film ''End of Innocence'' from 1991 documents the development of the uranium project from thediscovery of nuclear fission

Nuclear fission was discovered in December 1938 by chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann and physicists Lise Meitner and Otto Robert Frisch. Fission is a nuclear reaction or radioactive decay process in which the atomic nucleus, nucleus of a ...

in 1938 to the experiments in Haigerloch and the subsequent internment of the scientists in 1945. Some of the film scenes were shot at the original location in the Haigerloch rock cellar. Screenwriter Wolfgang Menge

Wolfgang Menge (10 April 1924 – 17 October 2012) was a German Screenwriter, television writer and journalist.

Personal life

He was married and had three sons.Frank Beyer

Frank Paul Beyer (; 26 May 1932 – 1 October 2006) was a German film director. In East Germany he was one of the most important film directors, working for the state film monopoly DEFA (film studio), DEFA and directed films that dealt mostl ...

were awarded the Deutscher Fernsehfilmpreis for writing and directing in 1991.

The play ''Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a population of 1.4 million in the Urban area of Copenhagen, urban area. The city is situated on the islands of Zealand and Amager, separated from Malmö, Sweden, by the ...

'' by Michael Frayn

Michael Frayn, FRSL (; born 8 September 1933) is an English playwright and novelist. He is best known as the author of the farce ''Noises Off'' and the dramas ''Copenhagen (play), Copenhagen'' and ''Democracy (play), Democracy''.

Frayn's novel ...

from 1998 is about a fictional meeting between Heisenberg and Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (, ; ; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish theoretical physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and old quantum theory, quantum theory, for which he received the No ...

and his wife Margarete at an unspecified point in time after the end of the war. At the end of the first act, Heisenberg reflects on the work on the Haigerloch research reactor, the lack of safety measures and the endeavor to achieve criticality for the first time. The three-character play received the Tony Award

The Antoinette Perry Award for Excellence in Broadway Theatre, more commonly known as a Tony Award, recognizes excellence in live Broadway theatre. The awards are presented by the American Theatre Wing and The Broadway League at an annual ce ...

for Best Play in 2000. A real meeting between the two men had taken place ''during'' the war in Copenhagen in 1941, but it is not clear from the documents that still exist today ''what'' was said at the time and specifically how it was ''meant'' and interpreted. According to Heisenberg's later recollection, he tried to speak "in code" because he feared that Bohr was being monitored and spied on by German occupation troops. Bohr seems to have misunderstood him, or Heisenberg's claims were a retrospective protective assertion.https://www.vanderbilt.edu/AnS/physics/brau/H182/Term%20papers%20'02/Norfleet.htm

The 1999 novel ''The Klingsor Paradox'' by Mexican author Jorge Volpi

Jorge Volpi (full name Jorge Volpi Escalante, born July 10, 1968) is a Mexican novelist and essayist, best known for his novels such as ''In Search of Klingsor ( En busca de Klingsor)''. Trained as a lawyer, he gained notice in the 1990s wi ...

is about the search by two scientists for Hitler's alleged closest scientific advisor, code-named Klingsor. In a flashback, we follow one of the two protagonists as he uncovers the German nuclear program in Heidelberg, Hechingen and Haigerloch as a fictitious part of the Alsos mission together with Goudsmit and Pash. In the end, Klingsor - the personification of evil

Evil, as a concept, is usually defined as profoundly immoral behavior, and it is related to acts that cause unnecessary pain and suffering to others.

Evil is commonly seen as the opposite, or sometimes absence, of good. It can be an extreme ...

- proves to be intangible. The bestseller received several awards, including the Spanish literary prize Premio Biblioteca Breve

The Premio Biblioteca Breve is a literary award given annually by the publisher Seix Barral (now part of Grupo Planeta) to an unpublished novel in the Spanish language. Its prize is €30,000 and publication of the winning work. It is delivered in ...

in 1999.

External links

* archive.orgAtomkeller-Museum

City of Haigerloch, retrieved on January 21, 2024 (pictures and background information on the research reactor). * * *

Literature

* * * * Werner Heisenberg: Der Teil und das Ganze. ''Gespräche im Umkreis der Atomphysik. 7.'' Edition. Piper, Munich and others 2008, (Serie Piper 2297). * * Robert Jungk: ''Heller als tausend Sonnen. Das Schicksal der Atomforscher.'' Scherz & Goverts, Stuttgart 1958 * * * * * * {{citation, author=Karl Wirtz , date=1987 , isbn=3-923704-02-X , location=Karlsruhe , publisher=Kernforschungszentrum Karlsruhe , title=Im Umkreis der PhysikReferences