HMS Vengeance (1899) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMS ''Vengeance'' was a

''Vengeance'' and her five

''Vengeance'' and her five

On the outbreak of the

On the outbreak of the

On 22 January 1915, ''Vengeance'' was selected to take part in the Dardanelles campaign. She stopped at

On 22 January 1915, ''Vengeance'' was selected to take part in the Dardanelles campaign. She stopped at

pre-dreadnought

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built from the mid- to late- 1880s to the early 1900s. Their designs were conceived before the appearance of in 1906 and their classification as "pre-dreadnought" is retrospectively appl ...

battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

of the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

and a member of the . Intended for service in Asia, ''Vengeance'' and her sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same Ship class, class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They o ...

s were smaller and faster than the preceding s, but retained the same battery of four guns. She also carried thinner armour, but incorporated new Krupp steel, which was more effective than the Harvey armour used in the ''Majestic''s. ''Vengeance'' was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one ...

in August 1898, launched in July 1899, and commissioned into the fleet in April 1902.

On entering service, ''Vengeance'' was assigned to the China Station

The Commander-in-Chief, China, was the admiral in command of what was usually known as the China Station, at once both a British Royal Navy naval formation and its admiral in command. It was created in 1865 and deactivated in 1941.

From 1831 to 1 ...

, but the Anglo-Japanese Alliance

The was an alliance between the United Kingdom and the Empire of Japan which was effective from 1902 to 1923. The treaty creating the alliance was signed at Lansdowne House in London on 30 January 1902 by British foreign secretary Lord Lans ...

rendered her presence there unnecessary, and she returned to European waters in 1905. Late that year, she underwent a refit that lasted into 1906. She then served in the Channel Fleet

The Channel Fleet and originally known as the Channel Squadron was the Royal Navy formation of warships that defended the waters of the English Channel from 1854 to 1909 and 1914 to 1915.

History

Throughout the course of Royal Navy's history th ...

until 1908, when she moved to the Home Fleet

The Home Fleet was a fleet of the Royal Navy that operated from the United Kingdom's territorial waters from 1902 with intervals until 1967. In 1967, it was merged with the Mediterranean Fleet creating the new Western Fleet.

Before the First ...

, thereafter serving in secondary roles, including as a tender and a gunnery training ship

A training ship is a ship used to train students as sailors. The term is mostly used to describe ships employed by navies to train future officers. Essentially there are two types: those used for training at sea and old hulks used to house class ...

. In 1913, she was transferred to the 6th Battle Squadron of the Second Fleet.

Following Britain's entrance into the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in August 1914, ''Vengeance'' patrolled the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

with the 8th Battle Squadron before moving to Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

to protect the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

in November 1914. She then joined the Dardanelles Campaign in January 1915, where she saw extensive action trying to force the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey th ...

strait in February and March and later supporting the fighting ashore during the Gallipoli Campaign in April and May. Worn out from these operations, she returned to Britain for a refit. She was recommissioned in December 1915 for service in East Africa

East Africa, also known as Eastern Africa or the East of Africa, is a region at the eastern edge of the Africa, African continent, distinguished by its unique geographical, historical, and cultural landscape. Defined in varying scopes, the regi ...

, during which she supported the capture of Dar es Salaam

Dar es Salaam (, ; from ) is the largest city and financial hub of Tanzania. It is also the capital of the Dar es Salaam Region. With a population of over 7 million people, Dar es Salaam is the largest city in East Africa by population and the ...

in German East Africa

German East Africa (GEA; ) was a German colonial empire, German colony in the African Great Lakes region, which included present-day Burundi, Rwanda, the Tanzania mainland, and the Kionga Triangle, a small region later incorporated into Portugu ...

. She returned to Britain again in 1917 and was decommissioned, thereafter serving in subsidiary roles until 1921, when she was sold for scrap

Scrap consists of recyclable materials, usually metals, left over from product manufacturing and consumption, such as parts of vehicles, building supplies, and surplus materials. Unlike waste, scrap can have monetary value, especially recover ...

. ''Vengeance'' was broken up

Ship breaking (also known as ship recycling, ship demolition, ship scrapping, ship dismantling, or ship cracking) is a type of ship disposal involving the breaking up of ships either as a source of Interchangeable parts, parts, which can be sol ...

the following year.

Design

''Vengeance'' and her five

''Vengeance'' and her five sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same Ship class, class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They o ...

s were designed for service in East Asia, where the new rising power Japan was beginning to build a powerful navy, though this role was quickly made redundant by the Anglo-Japanese Alliance

The was an alliance between the United Kingdom and the Empire of Japan which was effective from 1902 to 1923. The treaty creating the alliance was signed at Lansdowne House in London on 30 January 1902 by British foreign secretary Lord Lans ...

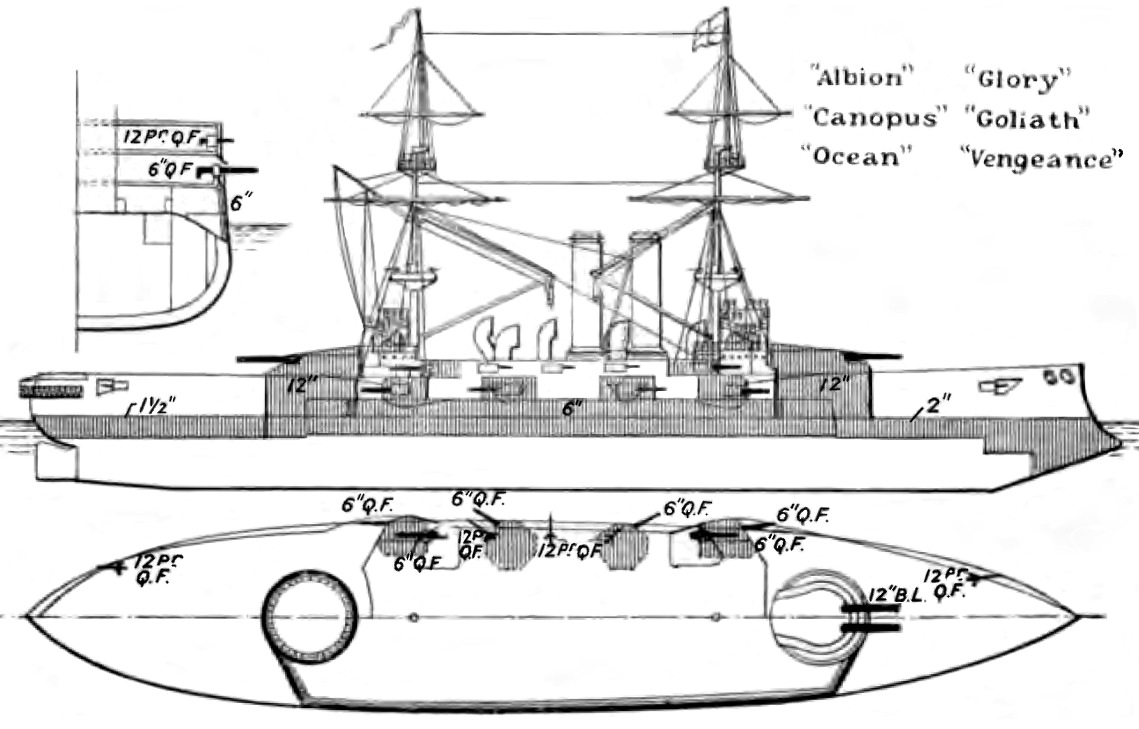

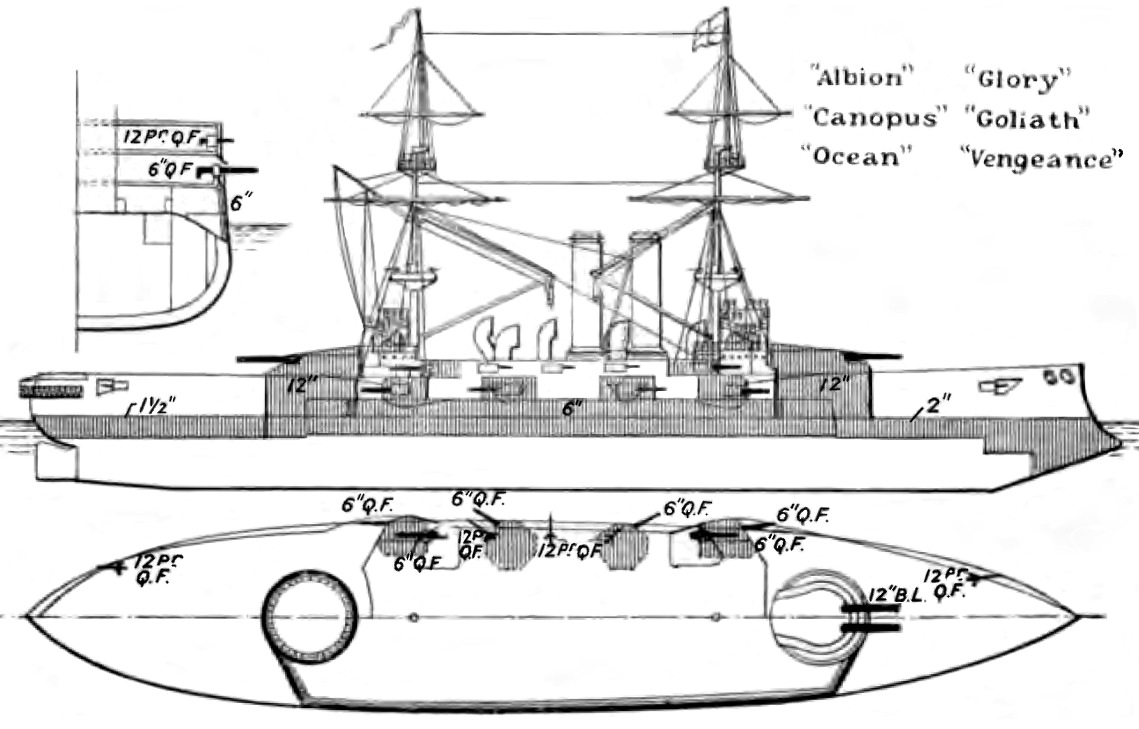

of 1902. The ships were designed to be smaller, lighter and faster than their predecessors, the s. ''Vengeance'' was long overall, with a beam of and a draught of . She displaced normally and up to fully loaded. Her crew numbered 682 officers and ratings.

The ''Canopus''-class ships were powered by a pair of 3-cylinder triple-expansion engine

A compound steam engine unit is a type of steam engine where steam is expanded in two or more stages.

A typical arrangement for a compound engine is that the steam is first expanded in a high-pressure (HP) Cylinder (engine), cylinder, then ha ...

s, with steam provided by twenty Belleville boilers. They were the first British battleships with water-tube boiler

A high pressure watertube boiler (also spelled water-tube and water tube) is a type of boiler in which water circulates in tubes heated externally by fire. Fuel is burned inside the furnace, creating hot gas which boils water in the steam-generat ...

s, which generated more power at less expense in weight compared with the fire-tube boiler

A fire-tube boiler is a type of boiler invented in 1828 by Marc Seguin, in which hot gases pass from a fire through one or more tubes running through a sealed container of water. The heat of the gases is transferred through the walls of the tube ...

s used in previous ships. The new boilers led to the adoption of fore-and-aft funnels, rather than the side-by-side funnel arrangement used in many previous British battleships. The ''Canopus''-class ships proved to be good steamers, with a high speed for battleships of their time— from —a full two knots faster than the ''Majestic''s.

''Vengeance'' had a main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a naval gun or group of guns used in volleys, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, th ...

of four BL 35-caliber Mk VIII guns mounted in twin-gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechanis ...

s fore and aft; these guns were mounted in circular barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protection ...

s that allowed all-around loading, although at a fixed elevation. The ships also mounted a secondary battery

A rechargeable battery, storage battery, or secondary cell (formally a type of Accumulator (energy), energy accumulator), is a type of electrical battery which can be charged, discharged into a load, and recharged many times, as opposed to a ...

of twelve 40-calibre guns mounted in casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armoured structure from which guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to antiquity, the term "casemate wall" ...

s, in addition to ten 12-pounder guns and six 3-pounder guns for defence against torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s. As was customary for battleships of the period, she was also equipped with four torpedo tubes

Tube or tubes may refer to:

* ''Tube'' (2003 film), a 2003 Korean film

* "Tubes" (Peter Dale), performer on the Soccer AM television show

* Tube (band), a Japanese rock band

* Tube & Berger, the alias of dance/electronica producers Arndt Röri ...

submerged in the hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* The hull of an armored fighting vehicle, housing the chassis

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a sea-going craft

* Submarine hull

Ma ...

, two on each broadside near the forward and aft barbette.

To save weight, ''Vengeance'' carried less armour than the ''Majestic''s— in the belt compared to —although the change from Harvey armour in the ''Majestic''s to Krupp armour

Krupp armour was a type of steel naval armour used in the construction of capital ships starting shortly before the end of the nineteenth century. It was developed by Germany's Krupp Arms Works in 1893 and quickly replaced Harvey armour as th ...

in ''Vengeance'' meant that the loss in protection was not as great as it might have been, Krupp armour having greater protective value at a given thickness than its Harvey equivalent. Similarly, the other armour used to protect the ship could also be thinner; the bulkheads on either end of the belt were thick. The main battery turrets were 8 in thick, atop barbettes, and the casemate battery was protected with 6 in of Krupp steel. Her conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armoured, from which an officer in charge can conn (nautical), conn (conduct or control) the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for t ...

had 12 in thick sides as well. She was fitted with two armoured decks, thick, respectively.

Service history

Pre-First World War

HMS ''Vengeance'' was laid down byVickers

Vickers was a British engineering company that existed from 1828 until 1999. It was formed in Sheffield as a steel foundry by Edward Vickers and his father-in-law, and soon became famous for casting church bells. The company went public in 18 ...

at Barrow-in-Furness

Barrow-in-Furness is a port town and civil parish (as just "Barrow") in the Westmorland and Furness district of Cumbria, England. Historic counties of England, Historically in the county of Lancashire, it was incorporated as a municipal borou ...

on 23 August 1898 and launched on 25 July 1899. Her completion was delayed by damage to the fitting-out dock, and she was not completed until April 1902. She was the first British battleship completely built, armed, and engined by a single company. HMS ''Vengeance'' was commissioned at Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. Most of Portsmouth is located on Portsea Island, off the south coast of England in the Solent, making Portsmouth the only city in En ...

by Captain Leslie Creery Stuart on 8 April 1902 for service with the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between ...

. She left the United Kingdom early the following month, arriving at Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

on 12 May. In September 1902 she visited the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

with other ships of the station for combined manoeuvres near Nauplia

Nafplio or Nauplio () is a coastal city located in the Peloponnese in Greece. It is the capital of the regional unit of Argolis and an important tourist destination. Founded in antiquity, the city became an important seaport in the Middle Ages du ...

, and two months later she was back visiting Plataea

Plataea (; , ''Plátaia'') was an ancient Greek city-state situated in Boeotia near the frontier with Attica at the foot of Mt. Cithaeron, between the mountain and the river Asopus, which divided its territory from that of Thebes. Its inhab ...

. In July 1903 she transferred to the China Station

The Commander-in-Chief, China, was the admiral in command of what was usually known as the China Station, at once both a British Royal Navy naval formation and its admiral in command. It was created in 1865 and deactivated in 1941.

From 1831 to 1 ...

to relieve her sister ship , and underwent a refit at Hong Kong

Hong Kong)., Legally Hong Kong, China in international treaties and organizations. is a special administrative region of China. With 7.5 million residents in a territory, Hong Kong is the fourth most densely populated region in the wor ...

in 1903–1904.

In 1905, the United Kingdom and Japan ratified a treaty of alliance, reducing the need for a large Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

presence on the China Station and prompting a recall of all battleships from the station. ''Vengeance'' was recalled on 1 June 1905 and proceeded to Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

, where she and her sister ship rendezvoused with their sister and the battleship . The four battleships departed Singapore on 20 June 1905 and steamed home in company, arriving at Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

on 2 August 1905. ''Vengeance'' paid off into the Devonport Reserve on 23 August 1905, and underwent a refit that lasted into 1906 during which her machinery was repaired.

On 15 May 1906, ''Vengeance'' commissioned for service in the Channel Fleet

The Channel Fleet and originally known as the Channel Squadron was the Royal Navy formation of warships that defended the waters of the English Channel from 1854 to 1909 and 1914 to 1915.

History

Throughout the course of Royal Navy's history th ...

. She transferred to the Home Fleet

The Home Fleet was a fleet of the Royal Navy that operated from the United Kingdom's territorial waters from 1902 with intervals until 1967. In 1967, it was merged with the Mediterranean Fleet creating the new Western Fleet.

Before the First ...

on 6 May 1908, and on 13 June 1908 was damaged in a collision with the merchant ship at Portsmouth. She moved to the Nore Division, Home Fleet, at the Nore

The Nore is a long sandbank, bank of sand and silt running along the south-centre of the final narrowing of the Thames Estuary, England. Its south-west is the very narrow Nore Sand. Just short of the Nore's easternmost point where it fades int ...

in February 1909, where she became a parent ship to special service vessels, and grounded in the Thames Estuary

The Thames Estuary is where the River Thames meets the waters of the North Sea, in the south-east of Great Britain.

Limits

An estuary can be defined according to different criteria (e.g. tidal, geographical, navigational or in terms of salinit ...

on 28 February 1909 without damage. In April 1909, she became tender to the Chatham Dockyard

Chatham Dockyard was a Royal Navy Dockyard located on the River Medway in Kent. Established in Chatham, Kent, Chatham in the mid-16th century, the dockyard subsequently expanded into neighbouring Gillingham, Kent, Gillingham; at its most extens ...

gunnery school, where she acted as a gunnery drill ship. On 29 November 1910, ''Vengeance'' suffered another mishap when she collided in fog with the merchant ship , suffering damage to her side, net shelf, and net booms. ''Vengeance'' then served in the 6th Battle Squadron based at Portland

Portland most commonly refers to:

*Portland, Oregon, the most populous city in the U.S. state of Oregon

*Portland, Maine, the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maine

*Isle of Portland, a tied island in the English Channel

Portland may also r ...

, then became a gunnery training ship at the Nore in January 1913.The 6th Squadron, together with the 5th Battle Squadron

The 5th Battle Squadron was a squadron of the British Royal Navy consisting of battleships. The 5th Battle Squadron was initially part of the Royal Navy's Second Fleet. During the First World War, the Home Fleet was renamed the Grand Fleet.

His ...

, formed the core of the Second Fleet.

First World War

On the outbreak of the

On the outbreak of the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in August 1914, the Royal Navy mobilised to meet the German High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet () was the battle fleet of the German Empire, German Imperial German Navy, Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. In February 1907, the Home Fleet () was renamed the High Seas Fleet. Admiral Alfred von Tirpi ...

. On 7 August, the 6th Battle Squadron was dissolved, the more modern s being transferred to the Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from th ...

; ''Vengeance'' was assigned to the 8th Battle Squadron, Channel Fleet. The 8th Squadron was tasked with patrol duties in the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

and Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

, though ''Vengeance'' was quickly transferred to the 7th Battle Squadron on 15 August 1914 to relieve the battleship as the squadron flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

. Shortly thereafter, half of the 7th Squadron battleships were dispersed to strengthen the detached cruiser squadrons patrolling for German commerce raider

Commerce raiding is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than engaging its combatants or enforcing a blockade against them. Privateering is a fo ...

s, leaving only ''Vengeance'', ''Prince George'', , and ''Goliath'' and the protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of cruiser of the late 19th century, took their name from the armored deck, which protected vital machine-spaces from fragments released by explosive shells. Protected cruisers notably lacked a belt of armour alon ...

. She covered the landing of the Plymouth Marine Battalion at Ostend

Ostend ( ; ; ; ) is a coastal city and municipality in the province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It comprises the boroughs of Mariakerke, Raversijde, Stene and Zandvoorde, and the city of Ostend proper – the la ...

, Belgium, on 25 August 1914. For this operation, she and the other five ships of the squadron, along with six destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

s, escorted the troopship

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable to land troops directly on shore, typic ...

s; at the same time, elements of the Grand Fleet attacked the German patrol line off Heligoland to occupy the High Seas Fleet.

In November 1914, she was transferred to Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

to replace a pair of older French vessels, the battleship and the armoured cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a pre-dreadnought battles ...

that had in turn relieved the armoured cruisers and as guard ship

A guard ship is a warship assigned as a stationary guard in a port or harbour, as opposed to a coastal patrol boat, which serves its protective role at sea.

Royal Navy

In the Royal Navy of the eighteenth century, peacetime guard ships were usual ...

s for the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

. She later moved on to the Cape Verde

Cape Verde or Cabo Verde, officially the Republic of Cabo Verde, is an island country and archipelagic state of West Africa in the central Atlantic Ocean, consisting of ten volcanic islands with a combined land area of about . These islands ...

-Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; ) or Canaries are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean and the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, Autonomous Community of Spain. They are located in the northwest of Africa, with the closest point to the cont ...

Station to relieve ''Albion'' as guard ship at Saint Vincent.

Dardanelles campaign

On 22 January 1915, ''Vengeance'' was selected to take part in the Dardanelles campaign. She stopped at

On 22 January 1915, ''Vengeance'' was selected to take part in the Dardanelles campaign. She stopped at Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

that month to embark Admiral John de Robeck and become second flagship of the Dardanelles squadron, and arrived at the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey th ...

in February 1915. Admiral Sackville Carden, the commander of the British Mediterranean Fleet, devised a plan to force the straits and attack the Ottoman capital by neutralising the Ottoman coastal defences at long range, clearing the minefields in the Dardanelles, and then entering the Sea of Marmara

The Sea of Marmara, also known as the Sea of Marmora or the Marmara Sea, is a small inland sea entirely within the borders of Turkey. It links the Black Sea and the Aegean Sea via the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits, separating Turkey's E ...

.

''Vengeance'' participated in the opening bombardment of the Ottoman Turkish

Ottoman Turkish (, ; ) was the standardized register of the Turkish language in the Ottoman Empire (14th to 20th centuries CE). It borrowed extensively, in all aspects, from Arabic and Persian. It was written in the Ottoman Turkish alphabet. ...

entrance forts on 18 February and 19 February 1915, though her role as de Robeck's flagship limited her to observing the fire of the other ships in his formation. The battleship developed problems with her capstan and so could not anchor in her firing position, forcing ''Vengeance'' to take her place. She bombarded the Orkanie fortress with direct fire

Direct fire or line-of-sight fire refers to firing of a ranged weapon whose projectile is launched directly at a target within the line-of-sight of the user. The firing weapon must have a sighting device and an unobstructed view to the target, ...

, but aerial reconnaissance proved that the fortress guns had not been disabled. Nevertheless, Carden ordered ''Vengeance'' and several other battleships to close with their targets and engage them at close range. The French battleship joined ''Vengeance'' in shelling Orkanie. Later in the afternoon, both ships began to engage a battery at Kumkale with their main guns, while their secondary battery kept firing at Orkanie. At 16:10, Carden ordered them to cease fire and inspect the fortification. On closing, ''Vengeance'' came under heavy fire from Orkanie and a battery at Cape Helles. ''Contre-amiral

Counter admiral is a military rank used for high-ranking officers in several navies around the world, though the rank is not used in the English-speaking world, where its equivalent rank is rear admiral. The term derives from the French . Dependi ...

'' (Rear Admiral) Émile Guépratte

Émile Paul Aimable Guépratte (30 August 1856 – 21 November 1939) was a French admiral.

Biography

Guépratte was born in Granville to a family of naval officers. He studied at the ''Lycée impérial'' in Brest from 1868, and joined the Écol ...

, the commander of the French contingent, later wrote that "the daring attack of the ''Vengeance'' in flinging herself against the forts when their fire was in no way reduced was one of the finest episodes of the day." She suffered some damage to her masts and rigging from gunfire from the forts, but she was not hit directly. Several other battleships came to her aid, and at 17:20, Carden ordered a retreat.

On 25 February, ''Vengeance'' took part in another attack on the Dardanelles fortresses. Along with ''Cornwallis'' and the French battleships ''Suffren'' and , she led the assault, which was supported by one French and three British battleships. Once the four supporting battleships had taken up their positions and begun firing at long range to suppress the Ottoman batteries, ''Vengeance'' and ''Cornwallis'' made the first pass at close range, intending to destroy the guns with direct hits. De Robeck took ''Vengeance'' to within of the fortifications at Kumkale and fired for ten minutes, before turning about to allow ''Cornwallis'' to engage the guns. The two French ships then followed, and by 15:00, the Ottoman guns had been effectively silenced, allowing for minesweepers to advance and attempt to clear the minefields; most of the fleet withdrew while the minesweepers worked, though ''Vengeance'' and the battleships and remained behind to cover them.

By clearing these fields, Allied warships could now enter the Dardanelles themselves, opening the route to attack additional fortifications around the town of Dardanus. While other vessels shelled the forts there, ''Vengeance'' and the battleship sent men ashore to destroy an abandoned artillery battery near Kumkale, with both ships remaining off shore to support the raid. The men landed unopposed, but the detachment from ''Vengeance'' quickly came under fire from Ottoman infantry on the far side of Kumkale. Lieutenant-Commander Eric Gascoigne Robinson

Rear admiral (Royal Navy), Rear Admiral Eric Gascoigne Robinson (16 May 1882 – 20 August 1965) was a Royal Navy officer and a recipient of the Victoria Cross. He earned his award by going ashore and single-handedly destroying a Turkish naval ...

, who led ''Vengeance''s demolition party, went forward by himself to destroy an Ottoman anti-aircraft gun, then led his detachment to destroy a second anti-aircraft gun and the one remaining gun at the Orkanie battery. For his actions, he was awarded the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious decoration of the Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, British decorations system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British ...

. Ottoman resistance prevented any further action, and the men returned to ''Vengeance''.

By late February, ''Vengeance'' was in need of boiler maintenance, so de Robeck transferred his flag to ''Irresistible'' while ''Vengeance'' went to Mudros

Moudros () is a town and a former municipality on the island of Lemnos, North Aegean, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Lemnos, of which it is a municipal unit. It covers the entire eastern peninsula o ...

for repairs. She had returned by 6 March, in time for another bombardment of the Ottoman defences; de Robeck again transferred his flag back to the ship for the operation. This time, the plan involved using ''Albion'' to spot for the powerful dreadnought battleship

The dreadnought was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an effect when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her were referred to as "dreadnoughts", ...

, which was to fire indirectly in the hopes of being able to neutralise the Ottoman guns at a range at which they could not respond. ''Vengeance'' and three other battleships covered ''Albion'' inside the straits. The ships quickly silenced the Ottoman guns at Dardanus, but mobile artillery batteries continually forced both ''Albion'' and ''Queen Elizabeth'' to shift position, largely preventing the latter from firing and the former from relaying corrections for the few shots ''Queen Elizabeth'' had been able to make. Nightfall and the lack of progress led to the operation being called off. Two days later, ''Queen Elizabeth'' was sent into the straits in an attempt to destroy the guns with direct fire, while ''Vengeance'' and three other battleships covered her from the mobile howitzers. Poor visibility hampered ''Queen Elizabeth''s gunners, and at 15:30 Carden called off the attack, having achieved nothing.

''Vengeance'' also took part in the main attack on the Narrows forts on 18 March 1915, by which time Carden had fallen ill and had to resign, leaving de Robeck to take overall command of the fleet. He therefore shifted his flag to ''Queen Elizabeth'', and ''Vengeance'' returned to the Second Division as a private ship

Private ship is a term used in the Royal Navy to describe that status of a commissioned warship in active service that is not currently serving as the flagship of a flag officer (i.e., an admiral or commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Com ...

. ''Vengeance'' did not engage the Ottomans until later in the afternoon, after ''Bouvet'' had been mined and sunk. ''Vengeance'' attacked the Ottoman "Hamidieh" battery, but most of her shells fell harmlessly in the center of the fortification, away from the guns. When it became clear that the Ottoman fortresses could not be silenced in time to allow the minesweepers to begin clearing the minefields further in the straits, de Robeck ordered the fleet to withdraw. In the process, two British battleships were also mined and sunk, and the battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of att ...

had also struck a mine, though she managed to return to Malta for repairs.

By late-April, the First Squadron included ''Vengeance'', seven other battleships, and four cruisers, and was commanded by Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a flag officer rank used by English-speaking navies. In most European navies, the equivalent rank is called counter admiral.

Rear admiral is usually immediately senior to commodore and immediately below vice admiral. It is ...

Rosslyn Wemyss

Admiral of the Fleet (Royal Navy), Admiral of the Fleet Rosslyn Erskine Wemyss, 1st Baron Wester Wemyss, (12 April 1864 – 24 May 1933), known as Sir Rosslyn Wemyss between 1916 and 1919, was a Royal Navy officer. During the First World War he ...

. The First Squadron was tasked with supporting the Landing at Cape Helles

The landing at Cape Helles () was part of the Gallipoli campaign, the amphibious landings on the Gallipoli peninsula by British and French forces on 25 April 1915 during the First World War. Cape Helles, Helles, at the foot of the peninsula, wa ...

, which took place on 25 April. ''Vengeance'' and the battleship were initially assigned to support the landing at Morto Bay, taking up their firing positions at 05:00 and opening fire at Ottoman positions in the heights around the bay shortly thereafter. ''Lord Nelson'' was later sent to support other landing beaches further south on the peninsula, and ''Vengeance'' was joined by ''Prince George''. As the allied ground forces advanced on Krithia, ''Vengeance'' and several other battleships provided fire support, though the Ottomans blocked the attack in the First Battle of Krithia.

Through early May, she remained off the beachhead, supporting the allied right flank along with ''Lord Nelson'' and the French battleship . She supported the ground troops during the Ottoman attack on Allied positions at Anzac Cove on 19 May 1915, before retiring to Mudros to replenish her fuel and ammunition. She returned to Gallipoli

The Gallipoli Peninsula (; ; ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles strait to the east.

Gallipoli is the Italian form of the Greek name (), meaning ' ...

on 25 May to relieve her sister . A submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

attacked her that day while she was steaming up from Mudros, but ''Vengeance'' quickly turned to starboard to avoid the torpedo and fired several shots at the submarine's periscope

A periscope is an instrument for observation over, around or through an object, obstacle or condition that prevents direct line-of-sight observation from an observer's current position.

In its simplest form, it consists of an outer case with ...

, forcing her to withdraw. By July 1915, ''Vengeance'' had boiler defects that prevented her from continuing combat operations, and she returned to the United Kingdom and paid off that month. She was under refit at Devonport until December 1915.

Later service

''Vengeance'' recommissioned in December 1915 and left Devonport on 30 December 1915 for a deployment toEast Africa

East Africa, also known as Eastern Africa or the East of Africa, is a region at the eastern edge of the Africa, African continent, distinguished by its unique geographical, historical, and cultural landscape. Defined in varying scopes, the regi ...

. The Royal Navy had begun sending reinforcements to the area in November to support the East African Campaign; on her arrival there, she joined three monitors

Monitor or monitor may refer to:

Places

* Monitor, Alberta

* Monitor, Indiana, town in the United States

* Monitor, Kentucky

* Monitor, Oregon, unincorporated community in the United States

* Monitor, Washington

* Monitor, Logan County, West ...

, two cruisers, two armed merchant vessels, and two gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

s. While there, she supported operations leading to the capture of Dar es Salaam

Dar es Salaam (, ; from ) is the largest city and financial hub of Tanzania. It is also the capital of the Dar es Salaam Region. With a population of over 7 million people, Dar es Salaam is the largest city in East Africa by population and the ...

in 1916. In February 1917, ''Vengeance'' returned to the United Kingdom and paid off. She was laid up until February 1918, when she recommissioned for use in experiments with anti-flash equipment for the fleet's guns. She completed these in April 1918, and then was partially disarmed, with four 6-inch (152-mm) main-deck casemate guns removed and four 6-inch guns being installed in open shields on the battery deck. She became an ammunition store ship in May 1918. ''Vengeance'' was placed on the sale list at Devonport on 9 July 1920, and was sold for scrapping on 1 December 1921. She had an eventful trip to the scrapyard. After she departed Devonport under tow on 27 December 1921 en route to Dover

Dover ( ) is a town and major ferry port in Kent, southeast England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies southeast of Canterbury and east of Maidstone. ...

, her tow rope parted in the English Channel on 29 December 1921. French tugs

A tugboat or tug is a marine vessel that manoeuvres other vessels by pushing or pulling them, with direct contact or a tow line. These boats typically tug ships in circumstances where they cannot or should not move under their own power, such ...

located her and towed her to Cherbourg

Cherbourg is a former Communes of France, commune and Subprefectures in France, subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French departments of France, department of Manche. It was merged into the com ...

, France. From there she was towed to Dover, where she finally arrived for scrapping on 9 January 1922.

Notes

References

* * * * * * *Further reading

* Dittmar, F. J., & J. J. Colledge., "British Warships 1914–1919", London: Ian Allan, 1972. . * * Pears, Randolph. ''British Battleships 1892–1957: The Great Days of the Fleets''. G. Cave Associates, 1979. . {{DEFAULTSORT:Vengeance Canopus-class battleships Vickers Ships built in Barrow-in-Furness 1899 ships Victorian-era battleships of the United Kingdom World War I battleships of the United Kingdom