H4 (chronometer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Harrison ( – 24 March 1776) was an English carpenter and clockmaker who invented the

John Harrison was born in Foulby in the

John Harrison was born in Foulby in the

In the 1720s, the English clockmaker Henry Sully invented a marine clock that was designed to determine longitude: this was in the form of a clock with a large

In the 1720s, the English clockmaker Henry Sully invented a marine clock that was designed to determine longitude: this was in the form of a clock with a large

In 1716, Sully presented his first to the French

and in 1726 he published . In 1730, Harrison designed a marine clock to compete for the Longitude prize and travelled to London, seeking financial assistance. He presented his ideas to

After steadfastly pursuing various methods during thirty years of experimentation, Harrison found to his surprise that some of the watches made by Graham's successor Thomas Mudge kept time just as accurately as his huge sea clocks. It is possible that Mudge was able to do this after the early 1740s thanks to the availability of the new "Huntsman" or "Crucible" steel first produced by

After steadfastly pursuing various methods during thirty years of experimentation, Harrison found to his surprise that some of the watches made by Graham's successor Thomas Mudge kept time just as accurately as his huge sea clocks. It is possible that Mudge was able to do this after the early 1740s thanks to the availability of the new "Huntsman" or "Crucible" steel first produced by

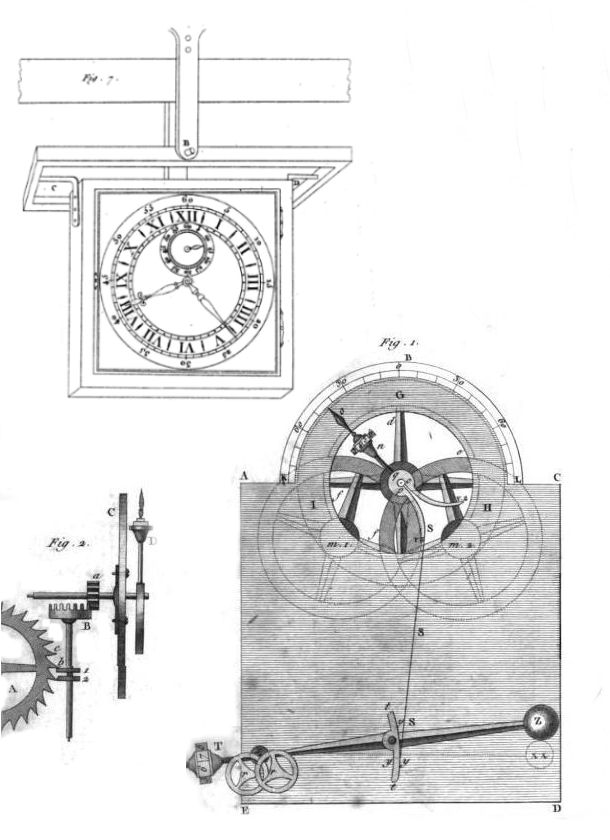

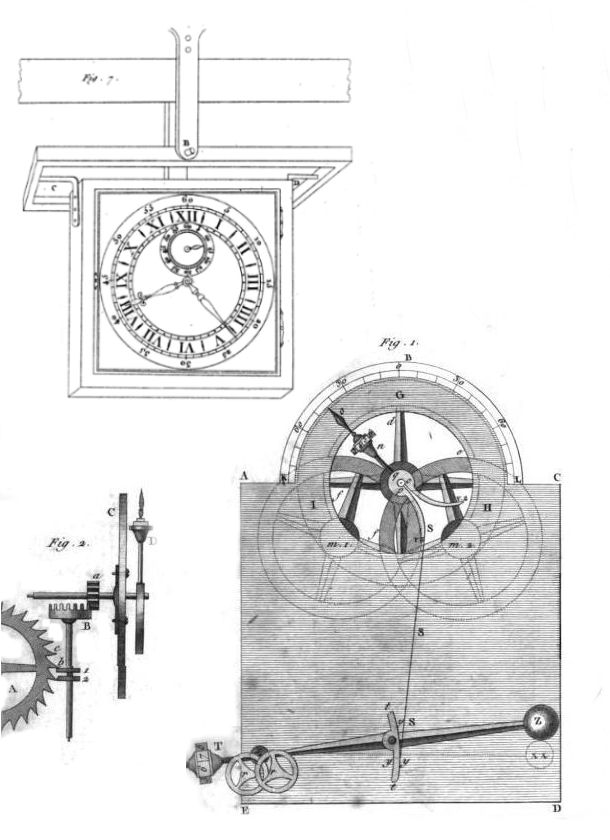

Drawings of Harrison's H4 chronometer of 1761, published in ''The principles of Mr Harrison's time-keeper'', 1767.

Harrison's first "sea watch" (now known as H4) is housed in silver pair cases some in diameter. The clock's movement is highly complex for the period, resembling a larger version of the then-current conventional movement. A coiled steel spring inside a brass mainspring barrel provides 30 hours of power. That is covered by the fusee barrel which pulls a chain wrapped around the conically shaped pulley known as the fusee. The fusee is topped by the winding square (requiring separate key). The great wheel attached to the base of this fusee transmits power to the rest of the movement. The fusee contains the

Drawings of Harrison's H4 chronometer of 1761, published in ''The principles of Mr Harrison's time-keeper'', 1767.

Harrison's first "sea watch" (now known as H4) is housed in silver pair cases some in diameter. The clock's movement is highly complex for the period, resembling a larger version of the then-current conventional movement. A coiled steel spring inside a brass mainspring barrel provides 30 hours of power. That is covered by the fusee barrel which pulls a chain wrapped around the conically shaped pulley known as the fusee. The fusee is topped by the winding square (requiring separate key). The great wheel attached to the base of this fusee transmits power to the rest of the movement. The fusee contains the

Harrison died on 24 March 1776, at the age of eighty-two, just shy of his eighty-third birthday. He was buried in the graveyard of St John's Church, Hampstead, in north London, along with his second wife Elizabeth and later their son William. His tomb was restored in 1879 by the

Harrison died on 24 March 1776, at the age of eighty-two, just shy of his eighty-third birthday. He was buried in the graveyard of St John's Church, Hampstead, in north London, along with his second wife Elizabeth and later their son William. His tomb was restored in 1879 by the

After

After

John Harrison and the Longitude Problem, at the National Maritime Museum sitePBS Nova Online: ''Lost at Sea, the Search for Longitude''John 'Longitude' Harrison and musical tuningExcerpt from: Time Restored: The Story of the Harrison Timekeepers and R.T. Gould, 'The Man who Knew (almost) Everything'

* ttps://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/arSAQ-UETSOyftkNWZTpVQ Harrison's precision pendulum-clock No. 2, 1727, on the BBC's "A History of the World" websitebr>Leeds Museums and Galleries "Secret Life of Objects" blog, John Harrison's precision pendulum-clock No. 2

Account of John Harrison and his chronometer

at

Building an Impossible Clock

Shayla Love, 19 Jan 2016, ''The Atlantic'' * {{DEFAULTSORT:Harrison, John 1693 births 1776 deaths 18th-century English people Burials at St John-at-Hampstead British carpenters English designers English clockmakers 18th-century English inventors English watchmakers (people) People from Barrow upon Humber People from Foulby Engineers from Yorkshire Recipients of the Copley Medal English scientific instrument makers

marine chronometer

A marine chronometer is a precision timepiece that is carried on a ship and employed in the determination of the ship's position by celestial navigation. It is used to determine longitude by comparing Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), and the time at t ...

, a long-sought-after device for solving the problem of how to calculate longitude while at sea.

Harrison's solution revolutionized navigation and greatly increased the safety of long-distance sea travel. The problem he solved had been considered so important following the Scilly naval disaster of 1707

The Scilly naval disaster of 1707 was the loss of four warships of a Royal Navy fleet off the Isles of Scilly in severe weather on 22 October 1707. Between 1,400 and 2,000 sailors lost their lives aboard the wrecked vessels, making the incident ...

that the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of ...

was offering financial rewards of up to £20,000 (equivalent to £ in ) under the 1714 Longitude Act, though Harrison never received the full reward due to political rivalries. He presented his first design in 1730, and worked over many years on improved designs, making several advances in time-keeping technology, finally turning to what were called sea watches. Harrison gained support from the Longitude Board in building and testing his designs. Towards the end of his life, he received recognition and a reward from Parliament.

Early life

John Harrison was born in Foulby in the

John Harrison was born in Foulby in the West Riding of Yorkshire

The West Riding of Yorkshire was one of three historic subdivisions of Yorkshire, England. From 1889 to 1974 the riding was an administrative county named County of York, West Riding. The Lord Lieutenant of the West Riding of Yorkshire, lieu ...

, the first of five children in his family. His stepfather worked as a carpenter at the nearby Nostell Priory

Nostell Priory is a Palladian house in Nostell, West Yorkshire, in England, near Crofton and on the road to Doncaster from Wakefield. It dates from 1733 and was built for the Winn family on the site of a medieval priory. The Priory and its co ...

estate. A house on the site of what may have been the family home bears a blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom, and certain other countries and territories, to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving a ...

. Around 1700, the Harrison family moved to the Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (), abbreviated ''Lincs'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands and Yorkshire and the Humber regions of England. It is bordered by the East Riding of Yorkshire across the Humber estuary to th ...

village of Barrow upon Humber

Barrow upon Humber is a village and civil parish in North Lincolnshire, England. The population at the 2021 census was about 3,000.

The village is near the Humber, about east from Barton-upon-Humber. The small port of Barrow Haven, north, ...

. Following his father's trade as a carpenter, Harrison built and repaired clock

A clock or chronometer is a device that measures and displays time. The clock is one of the oldest Invention, human inventions, meeting the need to measure intervals of time shorter than the natural units such as the day, the lunar month, a ...

s in his spare time. Legend has it that at the age of six, while in bed with smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

, he was given a watch

A watch is a timepiece carried or worn by a person. It is designed to maintain a consistent movement despite the motions caused by the person's activities. A wristwatch is worn around the wrist, attached by a watch strap or another type of ...

to amuse himself and he spent hours listening to it and studying its moving parts.

He also had a fascination with music, eventually becoming choirmaster

A choir ( ), also known as a chorale or chorus (from Latin ''chorus'', meaning 'a dance in a circle') is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform or in other words ...

for the Church of Holy Trinity, Barrow upon Humber

Church of Holy Trinity is an Anglican church and Grade I Listed building in Barrow upon Humber, North Lincolnshire, England.

Architecture

The arcades and chancel date to the 13th century, the tower and aisle are 14th-15th century. The building w ...

.

Harrison built his first longcase clock in 1713, at the age of 20. The mechanism was made entirely of wood. Three of Harrison's early wooden clocks have survived:

* the first (1713) is in the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers

The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers was established under a Royal Charter granted by King Charles I in 1631. It ranks sixty-first among the livery companies of the City of London, and comes under the jurisdiction of the Privy Council. The ...

' collection, previously in the Guildhall in London and since 2015 on display in the Science Museum

A science museum is a museum devoted primarily to science. Older science museums tended to concentrate on static displays of objects related to natural history, paleontology, geology, Industry (manufacturing), industry and Outline of industrial ...

.

* The second (1715) is also in the Science Museum in London

* the third (1717) is at Nostell Priory

Nostell Priory is a Palladian house in Nostell, West Yorkshire, in England, near Crofton and on the road to Doncaster from Wakefield. It dates from 1733 and was built for the Winn family on the site of a medieval priory. The Priory and its co ...

in Yorkshire, the face bearing the inscription "John Harrison Barrow".

The Nostell example, in the billiards

Cue sports are a wide variety of games of skill played with a cue stick, which is used to strike billiard balls and thereby cause them to move around a cloth-covered table bounded by elastic bumpers known as . Cue sports, a category of stic ...

room of this stately home, has a Victorian

Victorian or Victorians may refer to:

19th century

* Victorian era, British history during Queen Victoria's 19th-century reign

** Victorian architecture

** Victorian house

** Victorian decorative arts

** Victorian fashion

** Victorian literatur ...

outer case with small glass windows on each side of the movement so that the wooden workings may be inspected.

On 30 August 1718, John Harrison married Elizabeth Barret at Barrow-upon-Humber church. After her death in 1726, he married Elizabeth Scott on 23 November 1726, at the same church.

In the early 1720s, Harrison was commissioned to make a new turret clock

A turret clock or tower clock is a clock designed to be mounted high in the wall of a building, usually in a clock tower, in public buildings such as Church (building), churches, university buildings, and town halls. As a public amenity to enab ...

at Brocklesby Hall

Brocklesby Hall is a English country house, country house near to the village of Brocklesby in the West Lindsey Non-metropolitan district, district of Lincolnshire, England. The house is a Listed building, Grade I listed building and the surroundin ...

, North Lincolnshire. The clock still works, and like his previous clocks has a wooden movement of oak

An oak is a hardwood tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' of the beech family. They have spirally arranged leaves, often with lobed edges, and a nut called an acorn, borne within a cup. The genus is widely distributed in the Northern Hemisp ...

and lignum vitae

Lignum vitae (), also called guayacan or guaiacum, and in parts of Europe known as Pockholz or pokhout, is a wood from trees of the genus '' Guaiacum''. The trees are indigenous to the Caribbean and the northern coast of South America (e.g., Co ...

. Unlike his early clocks, it incorporates some original features to improve timekeeping, for example the grasshopper escapement

The grasshopper escapement is a low-friction escapement for pendulum clocks invented by British clockmaker John Harrison around 1722. An escapement, part of every mechanical clock, is the mechanism that gives the clock's pendulum periodic pushes ...

. Between 1725 and 1728, John and his brother James, also a skilled joiner

Joinery is a part of woodworking that involves joining pieces of wood, engineered lumber, or synthetic substitutes (such as laminate), to produce more complex items. Some woodworking joints employ mechanical fasteners, bindings, or adhesives, ...

, made at least three precision longcase clocks, again with the movements and longcase made of oak and lignum vitae. The grid-iron pendulum was developed during this period. Of these longcase clocks:

* Number 1 is in a private collection. Until 2004, it belonged to the Time Museum (USA), which closed in 2000.

* Number 2 is in the Leeds City Museum

Leeds City Museum, established in 1819, is a museum in Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. Since 2008 it has been housed in the former Mechanics' institute, Mechanics' Institute built by Cuthbert Brodrick, in Cookridge Street (now Millennium Squar ...

, as the centrepiece of a permanent display dedicated to John Harrison's achievements. The exhibition, "John Harrison: The Clockmaker Who Changed the World", opened on 23 January 2014. It was the first longitude-related event marking the tercentenary of the Longitude Act.

* Number 3 is in the collection of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers.

Harrison was a man of many skills and he used these to systematically improve the performance of the pendulum clock. He invented the gridiron pendulum, consisting of alternating brass

Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc, in proportions which can be varied to achieve different colours and mechanical, electrical, acoustic and chemical properties, but copper typically has the larger proportion, generally copper and zinc. I ...

and iron rods assembled in such a way that the thermal expansions and contractions essentially cancel each other out. Another example of his inventive genius was the grasshopper escapement

The grasshopper escapement is a low-friction escapement for pendulum clocks invented by British clockmaker John Harrison around 1722. An escapement, part of every mechanical clock, is the mechanism that gives the clock's pendulum periodic pushes ...

, a control device for the step-by-step release of a clock's driving power. Developed from the anchor escapement

In horology, the anchor escapement is a type of escapement used in pendulum clocks. The escapement is a mechanism in a mechanical clock that maintains the swing of the pendulum by giving it a small push each swing, and allows the clock's wheels ...

, it was almost frictionless, requiring no lubrication because the pallets were made from wood. This was an important advantage at a time when lubricants and their degradation were little understood. In his earlier work on sea clocks, Harrison was continually assisted, both financially and in many other ways, by the watchmaker and instrument maker George Graham

George Graham (born 30 November 1944) is a Scottish former football player and manager.

Nicknamed "Stroller", he made 455 appearances in England's Football League as a midfielder or forward for Aston Villa, Chelsea, Arsenal, Manchester Unite ...

. Harrison was introduced to Graham by the Astronomer Royal

Astronomer Royal is a senior post in the Royal Households of the United Kingdom. There are two officers, the senior being the astronomer royal dating from 22 June 1675; the junior is the astronomer royal for Scotland dating from 1834. The Astro ...

Edmond Halley

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena in 1676–77, Hal ...

, who championed Harrison and his work. The support was important to Harrison, as he was supposed to have found it difficult to communicate his ideas in a coherent manner.

Longitude problem

Longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east- west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek lett ...

fixes the location of a place on Earth east or west of a north–south reference line called the prime meridian

A prime meridian is an arbitrarily chosen meridian (geography), meridian (a line of longitude) in a geographic coordinate system at which longitude is defined to be 0°. On a spheroid, a prime meridian and its anti-meridian (the 180th meridian ...

. It is given as an angular measurement

In Euclidean geometry, an angle can refer to a number of concepts relating to the intersection of two straight lines at a point. Formally, an angle is a figure lying in a plane formed by two rays, called the '' sides'' of the angle, sharing ...

that ranges from 0° at the prime meridian to +180° eastward and −180° westward. Knowledge of a ship's east–west position is essential when approaching land. Over long voyages, cumulative errors in estimates of position by dead reckoning

In navigation, dead reckoning is the process of calculating the current position of a moving object by using a previously determined position, or fix, and incorporating estimates of speed, heading (or direction or course), and elapsed time. T ...

frequently led to shipwreck

A shipwreck is the wreckage of a ship that is located either beached on land or sunken to the bottom of a body of water. It results from the event of ''shipwrecking'', which may be intentional or unintentional. There were approximately thre ...

s and a great loss of life. Avoiding such disasters became vital in Harrison's lifetime, in an era when trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

Traders generally negotiate through a medium of cr ...

and the need for accurate navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the motion, movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navig ...

were increasing dramatically around the world.

Many ideas were proposed for how to determine longitude during a sea voyage. Earlier methods attempted to compare local time with the known time at a reference place, such as Greenwich

Greenwich ( , , ) is an List of areas of London, area in south-east London, England, within the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Greater London, east-south-east of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime hi ...

or Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, based on a simple theory that had first been proposed by Gemma Frisius

Gemma Frisius (; born Jemme Reinerszoon; December 9, 1508 – May 25, 1555) was a Dutch physician, mathematician, cartographer, philosopher, and instrument maker. He created important globes, improved the mathematical instruments of his day ...

. The methods relied on astronomical observations that were themselves reliant on the predictable nature of the motions of different heavenly bodies. Such methods were problematic because of the difficulty in maintaining an accurate record of the time at the reference place.

Harrison set out to solve the problem directly, by producing a reliable clock that could keep the time of the reference place accurately over long intervals without having to constantly adjust it. The difficulty was in producing a clock that was not affected by variations in temperature

Temperature is a physical quantity that quantitatively expresses the attribute of hotness or coldness. Temperature is measurement, measured with a thermometer. It reflects the average kinetic energy of the vibrating and colliding atoms making ...

, pressure

Pressure (symbol: ''p'' or ''P'') is the force applied perpendicular to the surface of an object per unit area over which that force is distributed. Gauge pressure (also spelled ''gage'' pressure)The preferred spelling varies by country and eve ...

, or humidity

Humidity is the concentration of water vapor present in the air. Water vapor, the gaseous state of water, is generally invisible to the human eye. Humidity indicates the likelihood for precipitation (meteorology), precipitation, dew, or fog t ...

, resisted corrosion in salt air, and was able to function on board a constantly moving ship. Many scientists, including Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

and Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Halen, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , ; ; also spelled Huyghens; ; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor who is regarded as a key figure in the Scientific Revolution ...

, doubted that such a clock could ever be built and favoured other methods for reckoning longitude, such as the method of lunar distances. Huygens ran trials using both a pendulum

A pendulum is a device made of a weight suspended from a pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate i ...

and a spiral balance spring

A balance spring, or hairspring, is a spring attached to the balance wheel in mechanical timepieces. It causes the balance wheel to oscillate with a resonant frequency when the timepiece is running, which controls the speed at which the wheels ...

clock as methods of determining longitude, with both types producing inconsistent results. Newton observed that "a good watch may serve to keep a reckoning at sea for some days and to know the time of a celestial observation; and for this end a good Jewel may suffice till a better sort of watch can be found out. But when longitude at sea is lost, it cannot be found again by any watch".

First three marine timekeepers

In the 1720s, the English clockmaker Henry Sully invented a marine clock that was designed to determine longitude: this was in the form of a clock with a large

In the 1720s, the English clockmaker Henry Sully invented a marine clock that was designed to determine longitude: this was in the form of a clock with a large balance wheel

A balance wheel, or balance, is the timekeeping device used in mechanical watches and small clocks, analogous to the pendulum in a pendulum clock. It is a weighted wheel that rotates back and forth, being returned toward its center position b ...

that was vertically mounted on friction rollers and impulsed by a frictional rest Debaufre-type escapement

An escapement is a mechanical linkage in mechanical watches and clocks that gives impulses to the timekeeping element and periodically releases the gear train to move forward, advancing the clock's hands. The impulse action transfers energy to t ...

. Very unconventionally, the balance oscillation

Oscillation is the repetitive or periodic variation, typically in time, of some measure about a central value (often a point of equilibrium) or between two or more different states. Familiar examples of oscillation include a swinging pendulum ...

s were controlled by a weight at the end of a pivoted horizontal lever attached to the balance by a cord. This solution avoided temperature error due to thermal expansion

Thermal expansion is the tendency of matter to increase in length, area, or volume, changing its size and density, in response to an increase in temperature (usually excluding phase transitions).

Substances usually contract with decreasing temp ...

, a problem which affects steel balance springs. Sully's clock kept accurate time only in calm weather, however, because the balance oscillations were affected by the pitching and rolling of the ship. Still, his clocks were among the first serious attempts to find longitude by improving the accuracy of timekeeping at sea. Harrison's machines, though much larger, are of similar layout: H3 has a vertically mounted balance wheel and is linked to another wheel of the same size, an arrangement that eliminates problems arising from the ship's motion.Federation of the Swiss Watch IndustryIn 1716, Sully presented his first to the French

Académie des Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

A Chronology of Clocksand in 1726 he published . In 1730, Harrison designed a marine clock to compete for the Longitude prize and travelled to London, seeking financial assistance. He presented his ideas to

Edmond Halley

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena in 1676–77, Hal ...

, the Astronomer Royal

Astronomer Royal is a senior post in the Royal Households of the United Kingdom. There are two officers, the senior being the astronomer royal dating from 22 June 1675; the junior is the astronomer royal for Scotland dating from 1834. The Astro ...

, who in turn referred him to George Graham

George Graham (born 30 November 1944) is a Scottish former football player and manager.

Nicknamed "Stroller", he made 455 appearances in England's Football League as a midfielder or forward for Aston Villa, Chelsea, Arsenal, Manchester Unite ...

, the country's foremost clockmaker. Graham must have been impressed by Harrison's ideas, for he loaned him money to build a model of his "Sea clock". As the clock was an attempt to make a seagoing version of his wooden pendulum clocks, which performed exceptionally well, he used wooden wheels, roller pinion

A pinion is a round gear—usually the smaller of two meshed gears—used in several applications, including drivetrain and rack and pinion systems.

Applications Drivetrain

Drivetrains usually feature a gear known as the pinion, which may v ...

s, and a version of the grasshopper escapement. Instead of a pendulum, he used two dumbbell balances which were linked together.

It took Harrison five years to build his first sea clock (or H1). He demonstrated it to members of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

who spoke on his behalf to the Board of Longitude

Board or Boards may refer to:

Flat surface

* Lumber, or other rigid material, milled or sawn flat

** Plank (wood)

** Cutting board

** Sounding board, of a musical instrument

* Cardboard (paper product)

* Paperboard

* Fiberboard

** Hardboard ...

. The clock was the first proposal that the Board considered to be worthy of a sea trial. In 1736, Harrison sailed to Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

on HMS ''Centurion'' under the command of Captain George Proctor and returned on HMS ''Orford'' after Proctor died at Lisbon on 4 October 1736. The clock lost time on the outward voyage. However, it performed well on the return trip: both the captain and the sailing master

The master, or sailing master, is a historical rank for a naval Officer (armed forces), officer trained in and responsible for the navigation of a sailing ship, sailing vessel.

In the Royal Navy, the master was originally a warrant officer who ...

of the ''Orford'' praised the design. The master noted that his own calculations had placed the ship sixty miles east of its true landfall which had been correctly predicted by Harrison using H1.

This was not the transatlantic voyage stipulated by the Board of Longitude in their conditions for winning the prize, but the Board was impressed enough to grant Harrison £500 for further development. Harrison had moved to London by 1737 and went on to develop H2, a more compact and rugged version. In 1741, after three years of building and two of on-land testing, H2 was ready, but by then Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

was at war with Spain in the War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession was a European conflict fought between 1740 and 1748, primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italian Peninsula, Italy, the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. Related conflicts include King Ge ...

, and the mechanism was deemed too important to risk falling into Spanish hands. In any event, Harrison suddenly abandoned all work on this second machine when he discovered a serious design flaw in the concept of the bar balances. He had not recognized that the period of oscillation of the bar balances could be affected by the yawing action of the ship (when the ship turned upon its vertical axis, such as when " coming about" while tacking). It was this that led him to adopt circular balances in the Third Sea Clock (H3). The Board granted him another £500 and while waiting for the war to end, he proceeded to work on H3.

Harrison spent seventeen years working on this third "sea clock", but despite every effort it did not perform exactly as he had wished. The problem was that, because Harrison did not fully understand the physics behind the springs used to control the balance wheels, the timing of the wheels was not isochronous

A sequence of events is isochronous if the events occur regularly, or at equal time intervals. The term ''isochronous'' is used in several technical contexts, but usually refers to the primary subject maintaining a constant period or interval ( ...

, a characteristic that affected its accuracy. The engineering world was not to fully understand the properties of springs for such applications for another two centuries. Despite that, it had proved a very valuable experiment and much was learned from its construction. Certainly with this machine Harrison left the world two enduring legacies–the bimetallic strip

A bimetallic strip or bimetal strip is a strip that consists of two strips of different metals which expand at different rates as they are heated. The different expansion rates cause the strip to bend one way if heated, and in the opposite dire ...

and the caged roller bearing.

Longitude watches

After steadfastly pursuing various methods during thirty years of experimentation, Harrison found to his surprise that some of the watches made by Graham's successor Thomas Mudge kept time just as accurately as his huge sea clocks. It is possible that Mudge was able to do this after the early 1740s thanks to the availability of the new "Huntsman" or "Crucible" steel first produced by

After steadfastly pursuing various methods during thirty years of experimentation, Harrison found to his surprise that some of the watches made by Graham's successor Thomas Mudge kept time just as accurately as his huge sea clocks. It is possible that Mudge was able to do this after the early 1740s thanks to the availability of the new "Huntsman" or "Crucible" steel first produced by Benjamin Huntsman

Benjamin Huntsman (4 June 170420 June 1776) was an England, English inventor and manufacturer of cast or crucible steel.

Biography

Huntsman was born the fourth child of William and Mary (née Nainby) Huntsman, a Quaker farming couple, in Epwo ...

sometime in the early 1740s, which enabled harder pinion

A pinion is a round gear—usually the smaller of two meshed gears—used in several applications, including drivetrain and rack and pinion systems.

Applications Drivetrain

Drivetrains usually feature a gear known as the pinion, which may v ...

s but more importantly a tougher and more highly polished cylinder escapement to be produced.

Harrison then realized that a mere watch after all could be made accurate enough for the task and was a far more practical proposition for use as a marine timekeeper. He proceeded to redesign the concept of the watch as a timekeeping device, basing his design on sound scientific principles.

"Jefferys" watch

He had already in the early 1750s designed a precision watch for his own use, which was made for him by the watchmaker John Jefferys 1752–1753. This watch incorporated a novel frictional rest escapement and was not only the first to have a compensation for temperature variations but also contained the first miniature '' going trainfusee

Fusee or fusée may refer to:

* Fusee (horology), a component of a clock

* Flare, a pyrotechnic device sometimes called a Fusee

* Fusee, an old word for "flintlock

Flintlock is a general term for any firearm that uses a flint-striking lock (fi ...

'' of Harrison's design which enabled the watch to continue running whilst being wound. These features led to the very successful performance of the "Jefferys" watch, which Harrison incorporated into the design of two new timekeepers which he proposed to build. These were in the form of a large watch and another of a smaller size but similar pattern. However, only the larger No. 1 watch (or "H4" as it is sometimes called) appears to have been finished (see the reference to "H4" below). Aided by some of London's finest workmen, he proceeded to design and make the world's first successful marine timekeeper that allowed a navigator to accurately assess his ship's position in longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east- west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek lett ...

. Importantly, Harrison showed everyone that it could be done by using a watch to calculate longitude. This was to be Harrison's masterpiece – an instrument of beauty, resembling an oversized pocket watch

A pocket watch is a watch that is made to be carried in a pocket, as opposed to a wristwatch, which is strapped to the wrist.

They were the most common type of watch from their development in the 16th century until wristwatches became popula ...

from the period. It is engraved with Harrison's signature, marked Number 1 and dated AD 1759.

H4

Drawings of Harrison's H4 chronometer of 1761, published in ''The principles of Mr Harrison's time-keeper'', 1767.

Harrison's first "sea watch" (now known as H4) is housed in silver pair cases some in diameter. The clock's movement is highly complex for the period, resembling a larger version of the then-current conventional movement. A coiled steel spring inside a brass mainspring barrel provides 30 hours of power. That is covered by the fusee barrel which pulls a chain wrapped around the conically shaped pulley known as the fusee. The fusee is topped by the winding square (requiring separate key). The great wheel attached to the base of this fusee transmits power to the rest of the movement. The fusee contains the

Drawings of Harrison's H4 chronometer of 1761, published in ''The principles of Mr Harrison's time-keeper'', 1767.

Harrison's first "sea watch" (now known as H4) is housed in silver pair cases some in diameter. The clock's movement is highly complex for the period, resembling a larger version of the then-current conventional movement. A coiled steel spring inside a brass mainspring barrel provides 30 hours of power. That is covered by the fusee barrel which pulls a chain wrapped around the conically shaped pulley known as the fusee. The fusee is topped by the winding square (requiring separate key). The great wheel attached to the base of this fusee transmits power to the rest of the movement. The fusee contains the maintaining power

In horology, a maintaining power is a mechanism for keeping a clock or watch going while it is being wound.

Huygens

The weight drive used by Christiaan Huygens in his early clocks acts as a maintaining power. In this layout, the weight which d ...

, a mechanism for keeping the H4 going while being wound. From Gould:

In comparison, the verge's escapement has a recoil with a limited balance arc and is sensitive to variations in driving torque. According to a review by H. M. Frodsham of the movement in 1878, H4's escapement had "a good deal of 'set' and not so much recoil, and as a result the impulse came very near to a double chronometer action".

The D-shaped pallets of Harrison's escapement are both made of diamond

Diamond is a Allotropes of carbon, solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Diamond is tasteless, odourless, strong, brittle solid, colourless in pure form, a poor conductor of e ...

, approximately 2 mm long with the curved side radius of 0.6 mm, a considerable feat of manufacture at the time. For technical reasons the balance was made much larger than in a conventional watch of the period, in diameter weighing and the vibrations controlled by a flat spiral steel spring of three turns with a long straight tail. The spring is tapered, being thicker at the stud end and tapering toward the collet at the centre. The movement also has centre seconds motion with a sweep seconds hand.

The Third Wheel is equipped with internal teeth and has an elaborate bridge similar to the pierced and engraved bridge for the period. It runs at 5 beats (ticks) per second, and is equipped with a tiny second remontoire

In mechanical horology, a remontoire (from the French ''remonter'', meaning 'to wind') is a small secondary source of power, a weight or spring, which runs the timekeeping mechanism and is itself periodically rewound by the timepiece's main power ...

. A balance-brake, activated by the position of the fusee, stops the watch half an hour before it is completely run down, in order that the remontoire does not run down also. Temperature compensation is in the form of a 'compensation curb' (or 'Thermometer Kirb' as Harrison called it). This takes the form of a bimetallic strip mounted on the regulating slide, and carrying the curb pins at the free end. During its initial testing, Harrison dispensed with this regulation using the slide, but left its indicating dial or figure piece in place. This first watch took six years to construct, following which the Board of Longitude determined to trial it on a voyage from Portsmouth to Kingston, Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

. For this purpose it was placed aboard the 50-gun , which set sail from Portsmouth on 18 November 1761. Harrison, by then 68 years old, sent it on this transatlantic trial in the care of his son, William

William is a masculine given name of Germanic languages, Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman Conquest, Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle ...

. The watch was tested before departure by Robertson, Master of the Academy at Portsmouth, who reported that on 6 November 1761 at noon it was 3 seconds slow, having lost 24 seconds in 9 days on mean solar time. The daily rate of the watch was therefore fixed as losing seconds per day.Rees's Clocks Watches and Chronometers, 1819–20, David & Charles reprint 1970

When ''Deptford'' reached its destination, after correction for the initial error of 3 seconds and accumulated loss of 3 minutes 36.5 seconds at the daily rate over the 81 days and 5 hours of the voyage, the watch was found to be 5 seconds slow compared to the known longitude of Kingston, corresponding to an error in longitude of 1.25 minutes, or approximately one nautical mile. William Harrison returned aboard the 14-gun , reaching England on 26 March 1762 to report the successful outcome of the experiment. Harrison senior thereupon waited for the £20,000 prize, but the Board were persuaded that the accuracy could have been just luck and demanded another trial. The Board were also not convinced that a timekeeper which took six years to construct met the test of practicality required by the Longitude Act. The Harrisons were outraged and demanded their prize, a matter that eventually worked its way to Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

, which offered £5,000 for the design. The Harrisons refused but were eventually obliged to make another trip to Bridgetown

Bridgetown (UN/LOCODE: BB BGI) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Barbados. Formerly The Town of Saint Michael, the Greater Bridgetown area is located within the Parishes of Barbados, parish of Saint Michael, Barbados, Saint Mic ...

on the island of Barbados

Barbados, officially the Republic of Barbados, is an island country in the Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies and the easternmost island of the Caribbean region. It lies on the boundary of the South American ...

to settle the matter.

At the time of this second trial, another method for measuring longitude was ready for testing: the Method of Lunar Distances. The Moon moves fast enough, some thirteen degrees a day, to easily measure the movement from day to day. By comparing the angle between the Moon and the Sun for the day one left for Britain, the "proper position" (how it would appear in Greenwich

Greenwich ( , , ) is an List of areas of London, area in south-east London, England, within the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Greater London, east-south-east of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime hi ...

, England, at that specific time) of the Moon could be calculated. By comparing this with the angle of the Moon over the horizon, the longitude could be calculated. During Harrison's second trial of his 'sea watch' (H4), Nevil Maskelyne

Nevil Maskelyne (; 6 October 1732 – 9 February 1811) was the fifth British Astronomer Royal. He held the office from 1765 to 1811. He was the first person to scientifically measure the mass of the planet Earth. He created '' The Nautical Al ...

was asked to accompany HMS ''Tartar'' and test the Lunar Distances system. Once again the watch proved extremely accurate, keeping time to within 39 seconds, corresponding to an error in the longitude of Bridgetown of less than . Maskelyne's measures were also fairly good, at , but required considerable work and calculation in order to use. At a meeting of the Board in 1765 the results were presented, but they again attributed the accuracy of the measurements to luck. Once again the matter reached Parliament, which offered £10,000 in advance and the other half once he turned over the design to other watchmakers to duplicate. In the meantime Harrison's watch would have to be turned over to the Astronomer Royal for long-term on-land testing.

Unfortunately, Nevil Maskelyne had been appointed Astronomer Royal

Astronomer Royal is a senior post in the Royal Households of the United Kingdom. There are two officers, the senior being the astronomer royal dating from 22 June 1675; the junior is the astronomer royal for Scotland dating from 1834. The Astro ...

on his return from Barbados, and was therefore also placed on the Board of Longitude. He returned a report of the watch that was negative, claiming that its "going rate" (the amount of time it gained or lost per day) was due to inaccuracies cancelling themselves out, and refused to allow it to be factored out when measuring longitude. Consequently, this first Marine Watch of Harrison's failed the needs of the Board despite the fact that it had succeeded in two previous trials.

Harrison began working on his second 'sea watch' (H5) while testing was conducted on the first, which Harrison felt was being held hostage by the Board. After three years he had had enough; Harrison felt "extremely ill used by the gentlemen who I might have expected better treatment from" and decided to enlist the aid of King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

. He obtained an audience with the King, who was extremely annoyed with the Board. King George tested the watch No. 2 (H5) himself at the palace and after ten weeks of daily observations between May and July in 1772, found it to be accurate to within one third of one second per day. King George then advised Harrison to petition Parliament for the full prize after threatening to appear in person to dress them down. Finally in 1773, when he was 80 years old, Harrison received a monetary award in the amount of £8,750 from Parliament for his achievements, but he never received the official award (which was never awarded to anyone). He was to live for just three more years.

In total, Harrison received £23,065 for his work on chronometers. He received £4,315 in increments from the Board of Longitude for his work, £10,000 as an interim payment for H4 in 1765 and £8,750 from Parliament in 1773. This gave him a reasonable income for most of his life (equivalent to roughly £450,000 per year in 2007, though all his costs, such as materials and subcontracting work to other horologists, had to come out of this). He became the equivalent of a multi-millionaire (in today's terms) in the final decade of his life. Captain James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

used K1, a copy of H4, on his second and third voyages, having used the lunar distance method

Lunar most commonly means "of or relating to the Moon".

Lunar may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Lunar'' (series), a series of video games

* "Lunar" (song), by David Guetta

* "Lunar", a song by Priestess from the 2009 album ''Prior t ...

on his first voyage. K1 was made by Larcum Kendall

Larcum Kendall (21 September 1719 in Charlbury, Oxfordshire – 22 November 1790 in London) was a watchmaker from Oxfordshire, who was active in London.

Early life

Kendall was born on 21 September 1719 in Charlbury. His father was a Merce ...

, who had been apprenticed to John Jefferys. Cook's log is full of praise for the watch and the charts of the southern Pacific Ocean he made with its use were remarkably accurate. K2 was loaned to Lieutenant William Bligh

William Bligh (9 September 1754 – 7 December 1817) was a Vice-admiral (Royal Navy), Royal Navy vice-admiral and colonial administrator who served as the governor of New South Wales from 1806 to 1808. He is best known for his role in the Muti ...

, commander of HMS ''Bounty'', but it was retained by Fletcher Christian

Fletcher Christian (25 September 1764 – 20 September 1793) was an English sailor who led the mutiny on the ''Bounty'' in 1789, during which he seized command of the Royal Navy vessel from Lieutenant William Bligh.

In 1787, Christian was ap ...

following the infamous mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military or a crew) to oppose, change, or remove superiors or their orders. The term is commonly used for insubordination by members of the military against an officer or superior, ...

. It was not recovered from Pitcairn Island

Pitcairn Island is the only inhabited island of the Pitcairn Islands, in the southern Pacific Ocean, of which many inhabitants are descendants of mutineers of HMS ''Bounty''.

Geography

The island is of volcanic origin, with a rugged cliff ...

until 1808, when it was given to Captain Mayhew Folger

Mayhew Folger (March 9, 1774 – September 1, 1828) was an American whaler who captained the sealing ship ''Topaz'' that rediscovered the Pitcairn Islands in 1808, whilst one of 's mutineers was still living.

Early life and family

Mayhew was born ...

, and then passed through several hands before reaching the National Maritime Museum

The National Maritime Museum (NMM) is a maritime museum in Greenwich, London. It is part of Royal Museums Greenwich, a network of museums in the Maritime Greenwich World Heritage Site. Like other publicly funded national museums in the Unit ...

in London.

Initially, the cost of these chronometers was quite high (roughly 30% of a ship's cost). However, over time, the costs dropped to between £25 and £100 (half a year's to two years' salary for a skilled worker) in the early 19th century. Many historians point to relatively low production volumes over time as evidence that the chronometers were not widely used. However, Landes points out that the chronometers lasted for decades and did not need to be replaced frequently–indeed the number of makers of marine chronometers reduced over time due to the ease in supplying the demand even as the merchant marine expanded. This book has a table showing that at the peak just prior to the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

, Britain's Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

had almost 1,000 ships. By 1840, this number had reduced to only 200. Even though the navy only officially equipped their vessels with chronometers after 1825, this shows that the number of chronometers required by the navy was shrinking in the early 19th century. Mörzer Bruyns identifies a recession starting around 1857 that depressed shipping and the need for chronometers. Also, many merchant mariners would make do with a deck chronometer at half the price. These were not as accurate as the boxed marine chronometer but were adequate for many. While the Lunar Distances method would complement and rival the marine chronometer initially, the chronometer would overtake it in the 19th century. The more accurate Harrison timekeeping device led to the much-needed precise calculation of longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east- west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek lett ...

, making the device a fundamental key to the modern age. After Harrison, the marine timekeeper was reinvented yet again by John Arnold, who, while basing his design on Harrison's most important principles, at the same time simplified it enough for him to produce equally accurate but far less costly marine chronometers in quantity from around 1783. Nonetheless, for many years even towards the end of the 18th century, chronometers were expensive rarities, as their adoption and use proceeded slowly due to the high expense of precision manufacturing. The expiry of Arnold's patents at the end of the 1790s enabled many other watchmakers including Thomas Earnshaw to produce chronometers in greater quantities at less cost even than those of Arnold.

By the early 19th century, navigation at sea without one was considered unwise to unthinkable. Using a chronometer to aid navigation simply saved lives and ships – the insurance industry, self-interest, and common sense did the rest in making the device a universal tool of maritime trade.

Death and memorials

Harrison died on 24 March 1776, at the age of eighty-two, just shy of his eighty-third birthday. He was buried in the graveyard of St John's Church, Hampstead, in north London, along with his second wife Elizabeth and later their son William. His tomb was restored in 1879 by the

Harrison died on 24 March 1776, at the age of eighty-two, just shy of his eighty-third birthday. He was buried in the graveyard of St John's Church, Hampstead, in north London, along with his second wife Elizabeth and later their son William. His tomb was restored in 1879 by the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers

The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers was established under a Royal Charter granted by King Charles I in 1631. It ranks sixty-first among the livery companies of the City of London, and comes under the jurisdiction of the Privy Council. The ...

, even though Harrison had never been a member of the Company.

Harrison's last home was 12 Red Lion Square

Red Lion Square is a small square in Holborn, London. The square was laid out in 1684 by Nicholas Barbon, taking its name from the Red Lion Inn. According to some sources, the bodies of three regicides—Oliver Cromwell, John Bradshaw and H ...

in the Holborn

Holborn ( or ), an area in central London, covers the south-eastern part of the London Borough of Camden and a part (St Andrew Holborn (parish), St Andrew Holborn Below the Bars) of the Wards of the City of London, Ward of Farringdon Without i ...

district of London. There is a blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom, and certain other countries and territories, to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving a ...

dedicated to Harrison on the wall of Summit House, a 1925 modernist office block, on the south side of the square. A memorial tablet to Harrison was unveiled in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

on 24 March 2006, finally recognising him as a worthy companion to his friend George Graham

George Graham (born 30 November 1944) is a Scottish former football player and manager.

Nicknamed "Stroller", he made 455 appearances in England's Football League as a midfielder or forward for Aston Villa, Chelsea, Arsenal, Manchester Unite ...

and Thomas Tompion

Thomas Tompion, FRS (1639–1713) was an English clockmaker, watchmaker and mechanician who is still regarded to this day as the "Father of English Clockmaking". Tompion's work includes some of the most historic and important clocks and watc ...

, 'The Father of English Watchmaking', who are both buried in the Abbey. The memorial shows a meridian line (line of constant longitude) in two metals to highlight Harrison's most widespread invention, the bimetallic strip thermometer. The strip is engraved with its own longitude of 0 degrees, 7 minutes and 35 seconds West.

The Corpus Clock

The Corpus Clock, also known as the Grasshopper clock, is a large sculptural clock at street level on the outside of the Taylor Library at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge, in the United Kingdo ...

in Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

, unveiled in 2008, is a homage by the designer to Harrison's work but is of an electromechanical design. In appearance it features Harrison's grasshopper escapement

The grasshopper escapement is a low-friction escapement for pendulum clocks invented by British clockmaker John Harrison around 1722. An escapement, part of every mechanical clock, is the mechanism that gives the clock's pendulum periodic pushes ...

, the 'pallet frame' being sculpted to resemble an actual grasshopper. This is the clock's defining feature.

In 2014, Northern Rail

Northern Rail, branded as Northern, was an English train operating company owned by Serco-Abellio that operated the Northern Rail franchise from 2004 until 2016. It was the primary passenger train operator in Northern England, and operated the ...

named diesel railcar 153316 as the ''John 'Longitude' Harrison''.

On 3 April 2018, Google

Google LLC (, ) is an American multinational corporation and technology company focusing on online advertising, search engine technology, cloud computing, computer software, quantum computing, e-commerce, consumer electronics, and artificial ...

celebrated his 325th birthday by making a Google Doodle

Google Doodle is a special, temporary alteration of the logo on Google's homepages intended to commemorate holidays, events, achievements, and historical figures. The first Google Doodle honored the 1998 edition of the long-running annual Bu ...

for its homepage.

In February 2020, a bronze statue of John Harrison was unveiled in Barrow upon Humber

Barrow upon Humber is a village and civil parish in North Lincolnshire, England. The population at the 2021 census was about 3,000.

The village is near the Humber, about east from Barton-upon-Humber. The small port of Barrow Haven, north, ...

. The statue was created by sculptor Marcus Cornish.

Later history

After

After World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Harrison's timepieces were rediscovered at the Royal Greenwich Observatory

The Royal Observatory, Greenwich (ROG; known as the Old Royal Observatory from 1957 to 1998, when the working Royal Greenwich Observatory, RGO, temporarily moved south from Greenwich to Herstmonceux) is an observatory situated on a hill in G ...

by retired naval officer Lieutenant Commander Rupert T. Gould.

The timepieces were in a highly decrepit state and Gould spent many years documenting, repairing and restoring them, without compensation for his efforts. Gould was the first to designate the timepieces from H1 to H5, initially calling them No.1 to No.5. Unfortunately, Gould made modifications and repairs that would not pass today's standards of good museum conservation practice, although most Harrison scholars give Gould credit for having ensured that the historical artifacts survived as working mechanisms to the present time. Gould wrote ''The Marine Chronometer'', published in 1923, which covered the history of chronometers from the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

to the 1920s, and which included detailed descriptions of Harrison's work and the subsequent evolution of the chronometer. The book remains the authoritative work on the marine chronometer. Today the restored H1, H2, H3, and H4 timepieces can be seen on display in the Royal Observatory at Greenwich. H1, H2, and H3 still work: H4 is kept in a stopped state because, unlike the first three, it requires oil for lubrication and so will degrade as it runs. H5 is owned by the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers

The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers was established under a Royal Charter granted by King Charles I in 1631. It ranks sixty-first among the livery companies of the City of London, and comes under the jurisdiction of the Privy Council. The ...

of London, and was previously on display at the Clockmakers' Museum in the Guildhall, London

Guildhall is a municipal building in the City of London, England. It is off Gresham and Basinghall streets, in the wards of Bassishaw and Cheap. The current building dates from the 15th century; however documentary evidence suggests that a ...

, as part of the Company's collection; since 2015 the collection has been displayed in the Science Museum, London

The Science Museum is a major museum on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, London. It was founded in 1857 and is one of the city's major tourist attractions, attracting 3.3 million visitors annually in 2019.

Like other publicly funded ...

.

In the final years of his life, John Harrison wrote about his research into musical tuning

In music, there are two common meanings for tuning:

* #Tuning practice, Tuning practice, the act of tuning an instrument or voice.

* #Tuning systems, Tuning systems, the various systems of Pitch (music), pitches used to tune an instrument, and ...

and manufacturing methods for bells. His tuning system (a meantone system derived from pi), is described in his pamphlet ''A Description Concerning Such Mechanism ... (CSM)''. The system challenged the traditional view that harmonics

In physics, acoustics, and telecommunications, a harmonic is a sinusoidal wave with a frequency that is a positive integer multiple of the ''fundamental frequency'' of a periodic signal. The fundamental frequency is also called the ''1st harm ...

occur at integer frequency

Frequency is the number of occurrences of a repeating event per unit of time. Frequency is an important parameter used in science and engineering to specify the rate of oscillatory and vibratory phenomena, such as mechanical vibrations, audio ...

ratios and in consequence all music using this tuning produces low-frequency beating. In 2002, Harrison's last manuscript, ''A true and short, but full Account of the Foundation of Musick, or, as principally therein, of the Existence of the Natural Notes of Melody'', was rediscovered in the US Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is a research library in Washington, D.C., serving as the library and research service for the United States Congress and the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It also administers Copyright law o ...

. His theories on the mathematics of bell manufacturing (using "Radical Numbers") are yet to be clearly understood.

One of the controversial claims of his last years was that of being able to build a land clock more accurate than any competing design. Specifically, he claimed to have designed a clock capable of keeping accurate time to within one second over a span of 100 days. At the time, such publications as ''The London Review of English and Foreign Literature'' ridiculed Harrison for what was considered an outlandish claim. Harrison drew a design but never built such a clock himself, but in 1970 Martin Burgess, a Harrison expert and himself a clockmaker, studied the plans and endeavored to build the timepiece as drawn. He built two versions, dubbed Clock A and Clock B. Clock A became the Gurney Clock which was given to the city of Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of the county of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. It lies by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. The population of the Norwich ...

in 1975, while Clock B lay unfinished in his workshop for decades until it was acquired in 2009 by Donald Saff

Donald Jay Saff (born 12 December 1937) is an artist, art historian, educator, and lecturer, specializing in the fields of contemporary art in addition to American and English horology.

Early life

Saff was born in Brooklyn, New York to Irving an ...

. The completed Clock B was submitted to the National Maritime Museum

The National Maritime Museum (NMM) is a maritime museum in Greenwich, London. It is part of Royal Museums Greenwich, a network of museums in the Maritime Greenwich World Heritage Site. Like other publicly funded national museums in the Unit ...

in Greenwich

Greenwich ( , , ) is an List of areas of London, area in south-east London, England, within the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Greater London, east-south-east of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime hi ...

for further study. It was found that Clock B could potentially meet Harrison's original claim, so the clock's design was carefully checked and adjusted. Finally, over a 100-day period from 6 January to 17 April 2015, Clock B was secured in a transparent case in the Royal Observatory and left to run untouched, apart from regular winding. Upon completion of the run, the clock was measured to have lost only 5/8 of a second, meaning Harrison's design was fundamentally sound. If we ignore the fact that this clock uses materials such as duraluminium and invar

Invar, also known generically as FeNi36 (64FeNi in the US), is a nickel–iron alloy notable for its uniquely low coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE or α). The name ''Invar'' comes from the word ''invariable'', referring to its relative lac ...

unavailable to Harrison, had it been built in 1762, the date of Harrison's testing of his H4, and run continuously since then without correction, it would now ( ) be slow by just minutes and seconds. Guinness World Records

''Guinness World Records'', known from its inception in 1955 until 1999 as ''The Guinness Book of Records'' and in previous United States editions as ''The Guinness Book of World Records'', is a British reference book published annually, list ...

has declared Martin Burgess' Clock B the "most accurate mechanical clock with a pendulum swinging in free air."

In literature, television, drama and music

In 1995, inspired by aHarvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

symposium on the longitude problem organized by the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors

The National Association of Watch & Clock Collectors, Inc. (NAWCC) is a nonprofit association of people who share a passion for collecting watches and clocks and studying horology (the art and science of time and timekeeping). The NAWCC's global m ...

, Dava Sobel

Dava Sobel (born June 15, 1947) is an American writer of popular expositions of scientific topics. Her books include ''Longitude'', about English clockmaker John Harrison; '' Galileo's Daughter'', about Galileo's daughter Maria Celeste; and ''T ...

wrote a book about Harrison's work. '' Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time'' became the first popular bestseller on the subject of horology

Chronometry or horology () is the science studying the measurement of time and timekeeping. Chronometry enables the establishment of standard measurements of time, which have applications in a broad range of social and scientific areas. ''Hor ...

. ''The Illustrated Longitude'', in which Sobel's text was accompanied by 180 images selected by William J. H. Andrewes, appeared in 1998. The book was dramatised for UK television by Charles Sturridge in a Granada Productions

ITV Studios Limited is a British multinational television media company owned by British television broadcaster ITV plc. It handles production and distribution of programmes broadcast on the ITV network and third-party broadcasters, and is bas ...

4 episode series for Channel 4

Channel 4 is a British free-to-air public broadcast television channel owned and operated by Channel Four Television Corporation. It is state-owned enterprise, publicly owned but, unlike the BBC, it receives no public funding and is funded en ...

in 1999, under the title ''Longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east- west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek lett ...

''. It was broadcast in the US later in the same year by co-producer A&E. The production starred Michael Gambon

Sir Michael John Gambon (; 19 October 1940 – 27 September 2023) was an Irish-English actor. Gambon started his acting career with Laurence Olivier as one of the original members of the Royal National Theatre. Over his six-decade-long career ...

as Harrison and Jeremy Irons

Jeremy John Irons (; born 19 September 1948) is an English actor. Known for his roles on stage and screen, he has received numerous accolades including an Academy Award, a Tony Award, three Primetime Emmy Awards, and two Golden Globe Awards, ...

as Gould. Sobel's book was the basis for a PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

NOVA

A nova ( novae or novas) is a transient astronomical event that causes the sudden appearance of a bright, apparently "new" star (hence the name "nova", Latin for "new") that slowly fades over weeks or months. All observed novae involve white ...

episode entitled ''Lost at Sea: The Search for Longitude''.

In 1998, British composer Harrison Birtwistle

Sir Harrison Birtwistle (15 July 1934 – 18 April 2022) was an English composer of contemporary classical music best known for his operas, often based on mythological subjects. Among his many compositions, his better known works include '' T ...

wrote the piano piece "Harrison's clocks" which contains musical depictions of Harrison's various clocks. Composer Peter Graham's piece ''Harrison's Dream'' is about Harrison's forty-year quest to produce an accurate clock. Graham worked simultaneously on the brass band and wind band versions of the piece, which received their first performances just four months apart in October 2000 and February 2001 respectively.

Works

*See also

*History of longitude

The history of longitude describes the centuries-long effort by astronomers, cartographers and navigators to discover a means of determining the longitude (the east-west position) of any given place on Earth. The measurement of longitude is impo ...

*Lunar distance (navigation)

In celestial navigation, lunar distance, also called a ''lunar'', is the angular distance between the Moon and another celestial body. The lunar distances method uses this angle and a nautical almanac to calculate Greenwich time if so desire ...

*Marine chronometer

A marine chronometer is a precision timepiece that is carried on a ship and employed in the determination of the ship's position by celestial navigation. It is used to determine longitude by comparing Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), and the time at t ...

*''The Island of the Day Before

''The Island of the Day Before'' () is a 1994 historical fiction novel by Umberto Eco set in the 17th century during the historical search for the secret of longitude. The central character is Roberto della Griva, an Italian nobleman stranded on ...

'' – Umberto Eco

References

Further reading

* * * * *External links

John Harrison and the Longitude Problem, at the National Maritime Museum site

* ttps://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/arSAQ-UETSOyftkNWZTpVQ Harrison's precision pendulum-clock No. 2, 1727, on the BBC's "A History of the World" websitebr>Leeds Museums and Galleries "Secret Life of Objects" blog, John Harrison's precision pendulum-clock No. 2

Account of John Harrison and his chronometer

at

Cambridge Digital Library

The Cambridge Digital Library is a project operated by the Cambridge University Library designed to make items from the unique and distinctive collections of Cambridge University Library available online. The project was initially funded by a dona ...

Building an Impossible Clock

Shayla Love, 19 Jan 2016, ''The Atlantic'' * {{DEFAULTSORT:Harrison, John 1693 births 1776 deaths 18th-century English people Burials at St John-at-Hampstead British carpenters English designers English clockmakers 18th-century English inventors English watchmakers (people) People from Barrow upon Humber People from Foulby Engineers from Yorkshire Recipients of the Copley Medal English scientific instrument makers