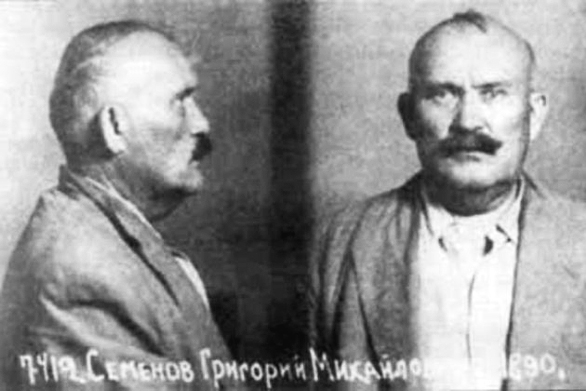

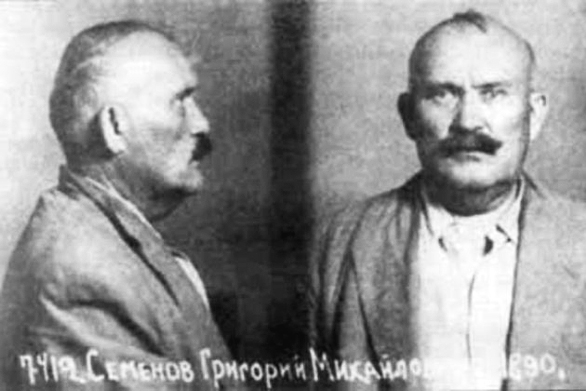

Grigory Mikhaylovich Semyonov on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Grigory Mikhaylovich Semyonov, or Semenov (; September 25, 1890 – August 30, 1946), was a

Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

-supported leader of the White movement in Transbaikal

The White movement in Transbaikal was a period of the confrontation between the Soviets and the Whites over dominance in Transbaikal from December 1917 to November 1920.

Initial stages

The first regular military formation of the Whites was the ...

and beyond from December 1917 to November 1920, a lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was norma ...

, and the ''ataman

Ataman (variants: ''otaman'', ''wataman'', ''vataman''; ; ) was a title of Cossack and haidamak leaders of various kinds. In the Russian Empire, the term was the official title of the supreme military commanders of the Cossack armies. The Ukra ...

'' of Baikal Cossacks

Baikal Cossacks were Cossacks of the Transbaikal Cossack Host (); a Cossack host formed in 1851 in the areas beyond Lake Baikal (hence, Transbaikal).

Organisation

The Transbaikal Cossack Host was one of those created during the 19th century as t ...

(1919). He was the commander of the Far Eastern Army

The Far Eastern Army was a military formation of Cossack and White rebel units in the Far East (20 February 1920 – 12 September 1921), formed by the former ataman of the Trans–Baikal Cossack Army, Lieutenant General Grigory Semyonov from thr ...

during the Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

. He was also a prominent figure in the White Terror

White Terror may refer to:

Events France

* First White Terror (1794–1795), a movement against the Jacobins in the French Revolution

* Second White Terror (1815), a movement against the French Revolution Post-Russian Empire

* White Terror (Rus ...

. U.S. Army intelligence estimated that he was responsible for executing 30,000 people in one year.

Early life and career

Semyonov was born in theTransbaikal

Transbaikal, Trans-Baikal, Transbaikalia ( rus, Забайка́лье, r=Zabaykal'ye, p=zəbɐjˈkalʲjɪ), or Dauria (, ''Dauriya'') is a mountainous region to the east of or "beyond" (trans-) Lake Baikal at the south side of the eastern Si ...

region of eastern Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

. His father, Mikhail Petrovich Semyonov, was Russian; his mother was a Buryat. Semyonov spoke Mongolian

Mongolian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Mongolia, a country in Asia

* Mongolian people, or Mongols

* Bogd Khanate of Mongolia, the government of Mongolia, 1911–1919 and 1921–1924

* Mongolian language

* Mongolian alphabet

* ...

and Buryat fluently. He joined the Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army () was the army of the Russian Empire, active from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was organized into a standing army and a state militia. The standing army consisted of Regular army, regular troops and ...

in 1908 and graduated from Orenburg

Orenburg (, ), formerly known as Chkalov (1938–1957), is the administrative center of Orenburg Oblast, Russia. It lies in Eastern Europe, along the banks of the Ural River, being approximately southeast of Moscow.

Orenburg is close to the ...

Military School in 1911. Commissioned first as a khorunzhiy

A standard-bearer ( Polish: ''Chorąży'' ; Russian and ; , chorunžis; ) is a military rank in Poland, Ukraine and some neighboring countries. A ''chorąży'' was once a knight who bore an ensign, the emblem of an armed troops, a voivodship, a la ...

(cornet or lieutenant), he rose to the rank of ''yesaul

Yesaul, osaul or osavul (, ) (from Turkic yasaul - ''chief''), is a post and a rank in the Russian and Ukrainian Cossack units.

The first records of the rank imply that it was introduced by Stefan Batory, King of Poland in 1576.

Cossacks in R ...

'' (Cossack captain), distinguished himself in battle against the Germans and the Austro-Hungarians in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, and earned the Saint George's Cross for courage.Bisher, ''White Terror''.

Pyotr Wrangel

Baron Pyotr Nikolayevich Wrangel (, ; ; 25 April 1928), also known by his nickname the Black Baron, was a Russian military officer of Baltic German origin in the Imperial Russian Army. During the final phase of the Russian Civil War, he was c ...

wrote:

Semenov was a Transbaikalian Cossack – dark and thickset, and of the rather alert Mongolian type. His intelligence was of a specifically Cossack calibre, and he was an exemplary soldier, especially courageous when under the eye of his superior. He knew how to make himself popular with Cossacks and officers alike, but he had his weaknesses in a love of intrigue and indifference to the means by which he achieved his ends. Though capable and ingenious, he had received no education, and his outlook was narrow. I have never been able to understand how he came to play a leading role.As somewhat of an outsider among his fellow officers because of his

ethnicity

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they Collective consciousness, collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, ...

, he met another officer shunned by his peers, Baron Ungern-Sternberg

Nikolai Robert Maximilian Freiherr von Ungern-Sternberg (; 10 January 1886 – 15 September 1921), often referred to as Roman von Ungern-Sternberg or Baron Ungern, was an anti-communist general in the Russian Civil War and then an independent wa ...

, whose eccentric nature and disregard for the rules of etiquette and decorum repelled others. He and Ungern tried to organize a regiment of Assyrian Christians

Assyrians (, ) are an ethnic group indigenous to Mesopotamia, a geographical region in West Asia. Modern Assyrians share descent directly from the ancient Assyrians, one of the key civilizations of Mesopotamia. While they are distinct from ot ...

to aid in the Russian fight against the Ottomans. In July 1917, Semyonov left the Caucasus and was appointed commissar

Commissar (or sometimes ''Kommissar'') is an English transliteration of the Russian (''komissar''), which means ' commissary'. In English, the transliteration ''commissar'' often refers specifically to the political commissars of Soviet and ...

of the Provisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, a transitional government or provisional leadership, is a temporary government formed to manage a period of transition, often following state collapse, revoluti ...

in the Baikal region and was responsible for recruiting a regiment of Buryat volunteers.

Russian Civil War in Transbaikal

After theOctober Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

of November 1917, Semyonov stirred up a sizable anti-Soviet rebellion but was defeated after several months of fighting, and he fled to the northeastern Chinese city of Harbin

Harbin, ; zh, , s=哈尔滨, t=哈爾濱, p=Hā'ěrbīn; IPA: . is the capital of Heilongjiang, China. It is the largest city of Heilongjiang, as well as being the city with the second-largest urban area, urban population (after Shenyang, Lia ...

. He then moved to Manzhouli

Manzhouli ( zh, s=满洲里; ; ) is a sub-prefectural city located in Hulunbuir prefecture-level city, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China. Located on the border with Russia, it is a major land port of entry. It has an area of and a populat ...

in Inner Mongolia, where the Chinese Eastern Railway

The Chinese Eastern Railway or CER (, , or , ''Kitaysko-Vostochnaya Zheleznaya Doroga'' or ''KVZhD''), is the historical name for a railway system in Northeast China (also known as Manchuria).

The Russian Empire constructed the line from 1897 ...

met the Chita Railway, expelled the Bolshevik garrison guarding the rail junction, and recruited an army, mainly from Buryat and Chinese recruits. In January 1918, he invaded Transbaikal, but by February, had been forced by Bolshevik partisans to retreat back to Manzhouli, where he was visited by R.B.Denny, British Military Attache in Beijing, who formed an "extremely favourable impression of him". On his recommendation, the Foreign Office in London agreed to pay Semyonov £10,000 a month, with no conditions attached,. The French government also decided to give him financial aid, while the Japanese placed an intelligence officer, Captain Kuroki Chikayochi, in Semyonov's headquarters. The British subsidies ended, by which time "Japanese influence was so strong that Semyonov was for practical purposes a puppet."

In April 1918, Semyonov launched another raid into Siberia with the help of the Czechoslovak Legion

The Czechoslovak Legion ( Czech: ''Československé legie''; Slovak: ''Československé légie'') were volunteer armed forces consisting predominantly of Czechs and Slovaks fighting on the side of the Entente powers during World War I and the ...

. By August 1918 he had managed to consolidate his positions in the Transbaikal region, where he set up a provisional government. On 6 September, his men captured Chita, and slaughtered 348 of its citizens. He made Chita his capital. Semyonov declared a "Great Mongol State" in 1918 and had designs to unify the Oirat Mongol lands, portions of Xinjiang

Xinjiang,; , SASM/GNC romanization, SASM/GNC: Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Sinkiang, officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People' ...

, Transbaikal, Inner Mongolia, Outer Mongolia, Tannu Uriankhai

Tannu Uriankhai (, ; , ; ) was a historical region of the Mongol Empire, its principal successor, the Yuan dynasty, and later the Qing dynasty. The territory of Tannu Uriankhai largely corresponds to the modern-day Tuva Republic of the Russian F ...

, Kobdo, Hulunbei'er, and Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ), or Greater Tibet, is a region in the western part of East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are other ethnic groups s ...

into one Mongolian state.

The region under his control, also called Eastern Okraina

The Russian Eastern Okraina () was a local government that existed in the Russian Far East region in 1920 during the Russian Civil War of 1917–1923.

History

In 1919, White forces in Western Siberia were defeated by the Bolsheviks. On 4 January ...

, extended from Verkhne-Udinsk near Lake Baikal

Lake Baikal is a rift lake and the deepest lake in the world. It is situated in southern Siberia, Russia between the Federal subjects of Russia, federal subjects of Irkutsk Oblast, Irkutsk Oblasts of Russia, Oblast to the northwest and the Repu ...

to the Shilka River

The Shilka (; Evenki: Силькари, Sil'kari; , ''Shilke''; , ''Shilka''; ) is a river in Zabaykalsky Krai, (Dauria) south-eastern Russia. It has a length of , and has a drainage basin of .Stretensk, to Manzhouli and northeast some distance along the ho/nowiki> drew his income from holding up trains and forcing payments, no matter what the nature of the load nor for whose benefit it was being shipped". He handed out copies of the '' With Japanese protection, he recognised no other authority. When

With Japanese protection, he recognised no other authority. When

Semyonov was captured in

Semyonov was captured in

Amur Railway

The broad gauge Amur Railway is the last section of the Trans-Siberian Railway in Russia, built in 1907–1916. The construction of this railway favoured the development of the gold mining industry, logging, fisheries and the fur trade in Siber ...

. In early 1919, Semyonov declared himself ''ataman

Ataman (variants: ''otaman'', ''wataman'', ''vataman''; ; ) was a title of Cossack and haidamak leaders of various kinds. In the Russian Empire, the term was the official title of the supreme military commanders of the Cossack armies. The Ukra ...

'' of the Transbaikal Cossack Host.

In his rule over the Transbaikal, Semyonov has been described as a "plain bandit Protocols of the Elders of Zion

''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion'' is a fabricated text purporting to detail a Jewish plot for global domination. Largely plagiarized from several earlier sources, it was first published in Imperial Russia in 1903, translated into multip ...

'' to the Japanese troops with whom he became associated.

With Japanese protection, he recognised no other authority. When

With Japanese protection, he recognised no other authority. When Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in many navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force. Admiral is ranked above vice admiral and below admiral of ...

Aleksandr Kolchak

List of Russian admirals, Admiral Alexander Vasilyevich Kolchak (; – 7 February 1920) was a Russian navy officer and Arctic exploration, polar explorer who led the White movement in the Russian Civil War. As he assumed the title of Supreme Ru ...

, who was based in Omsk

Omsk (; , ) is the administrative center and largest types of inhabited localities in Russia, city of Omsk Oblast, Russia. It is situated in southwestern Siberia and has a population of over one million. Omsk is the third List of cities and tow ...

, in Siberia, was declared Supreme Ruler by the White Armies

The White movement,. The old spelling was retained by the Whites to differentiate from the Reds. also known as the Whites, was one of the main factions of the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922. It was led mainly by the right-leaning and conserva ...

, Semyonov refused to submit to him. They had met once, in Manzhouli, in May 1918, when Semyonov insulted Kolchak by failing to be at the railway station to greet him. Kolchak considered sending an army into Transbaikal to remove Semyonov, but had to abandon the idea because Semyonov was protected by the Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

, who had 72,000 troops in Siberia. In October 1919, Kolchak recognised Semyonov as commander-in-chief of the Transbaikal region.

In December 1919, Semyonov sent a detachment to Irkutsk

Irkutsk ( ; rus, Иркутск, p=ɪrˈkutsk; Buryat language, Buryat and , ''Erhüü'', ) is the largest city and administrative center of Irkutsk Oblast, Russia. With a population of 587,891 Irkutsk is the List of cities and towns in Russ ...

, which had been the last city west of Lake Baikal still nominally under Kolchak's rule until a coalition of Mensheviks

The Mensheviks ('the Minority') were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903. Mensheviks held more moderate and reformist ...

and Socialist Revolutionaries

The Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR; ,, ) was a major socialist political party in the late Russian Empire, during both phases of the Russian Revolution, and in early Soviet Russia. The party members were known as Esers ().

The SRs were agr ...

seized control. The detachment reached Irkutsk, but did nothing except take 30 men and one young woman hostage. They took their hostages aboard an icebreaker on Lake Baikal, where, on 5 January, they clubbed them to death with a wooden mallet, one by one, and threw them overboard - all except for one man who put up a fight and was thrown alive into the freezing water.

When Kolchak resigned on 4 January 1920 he transferred his military forces in the Far East

The Far East is the geographical region that encompasses the easternmost portion of the Asian continent, including North Asia, North, East Asia, East and Southeast Asia. South Asia is sometimes also included in the definition of the term. In mod ...

to Semyonov. However, Semyonov was unable to keep his troops in Siberia under control: they stole, burned, murdered

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification or valid excuse committed with the necessary intention as defined by the law in a specific jurisdiction. ("The killing of another person without justification or excu ...

, and raped, developing a reputation for being little better than thugs. In July 1920, the Japanese Expeditionary Corps started a limited withdrawal in accordance with the Gongota Agreement, which was signed on 15 July 1920 with the Far Eastern Republic

The Far Eastern Republic ( rus, Дальневосточная Республика, Dal'nevostochnaya Respublika, p=dəlʲnʲɪvɐˈstotɕnəjə rʲɪsˈpublʲɪkə, links=yes; ), sometimes called the Chita Republic (, ), was a nominally indep ...

and undermined support for Semyonov. Transbaikal partisans, internationalists Internationalists may refer to:

* Internationalism (politics)

Internationalism is a political principle that advocates greater political or economic cooperation among State (polity), states and nations. It is associated with other political mov ...

, and the 5th Soviet Army under Genrich Eiche

Genrich Christoforovich Eiche (, ; September 29 (October 12) 1893, Riga — June 25, 1968 Jūrmala, Latvia) was a Soviet military commander and historian of Latvian ethnicity. He served in World War I as an officer in the Russian Imperial Army ...

launched an operation to retake Chita. In October 1920, units of the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

and guerrillas

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, Partisan (military), partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include Children in the military, recruite ...

forced Semyonov's army out of the Baikal region. He escaped by plane to Manchuria. In late May 1921 Semyonov travelled to Japan, where he received some support. He returned to the Primorye

Primorsky Krai, informally known as Primorye, is a federal subject (a krai) of Russia, part of the Far Eastern Federal District in the Russian Far East. The city of Vladivostok on the southern coast of the krai is its administrative center, an ...

in the hope of continuing to fight against the Soviets, but was finally forced to abandon all of Russian territory by September 1921.

In exile

He eventually returned toChina

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, where he was given a monthly 1000-yen

The is the official currency of Japan. It is the third-most traded currency in the foreign exchange market, after the United States dollar and the euro. It is also widely used as a third reserve currency after the US dollar and the euro.

T ...

pension by the Japanese government. In Tianjin

Tianjin is a direct-administered municipality in North China, northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the National Central City, nine national central cities, with a total population of 13,866,009 inhabitants at the time of the ...

, he made ties with the Japanese intelligence

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. It can be described as t ...

community and mobilized exiled Russian and Cossack communities that planned an eventual overthrow of the Soviets. He was also employed by Puyi

Puyi (7 February 190617 October 1967) was the final emperor of China, reigning as the eleventh monarch of the Qing dynasty from 1908 to 1912. When the Guangxu Emperor died without an heir, Empress Dowager Cixi picked his nephew Puyi, aged tw ...

, the dethroned Emperor of China, whom he wished to restore to power.

While he was an exile in China, he was still backed by the Japanese. His influence was such that when Anastasy Vonsiatsky

Anastasy Andreyevich Vonsiatsky (, ; June 12, 1898 – February 5, 1965), better known in the United States as Anastase Andreivitch Vonsiatsky, was a Russian anti-Bolshevik White émigré, émigré and fascism, fascist leader based in the United ...

of the Russian Fascist Party

The All-Russian Fascist Party ( ) and from 1937 onwards the Russian Fascist Union () was a minor Russian émigré movement that was based in Manchukuo during the 1930s and 1940s.

History

Fascism had existed amongst the Manchurian Russians; th ...

wanted to visit Manchukuo

Manchukuo, officially known as the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of Great Manchuria thereafter, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Northeast China that existed from 1932 until its dissolution in 1945. It was ostens ...

, the Japanese puppet state in Manchuria, he needed Semyonov's help in getting a visa. Vonsiatsky, however, saw Semyonov as a threat to his dream of being Russia's Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his overthrow in 194 ...

, and declared that he should be shot, an outburst that led to the Russian Fascist Party splitting in two. Konstantin Rodzaevsky

Konstantin Vladimirovich Rodzaevsky (; – 30 August 1946) was the leader of the Russian Fascist Party, which he led in exile from Manchuria. Rodzaevsky was also the chief editor of the RFP paper '' Nash Put. After the defeat of anti-commu ...

, who supplanted Vonsiatsky as the leader of the Russian Fascists in China co-operated with Semyonov to placate the Japanese.

In 1934, the Japanese formed the Bureau for Russian Emigrants in Manchuria (BREM; Бюро по делам российских эмигрантов в Маньчжурской империи), which were nominally under the control of the recent Russian Fascist Party

The All-Russian Fascist Party ( ) and from 1937 onwards the Russian Fascist Union () was a minor Russian émigré movement that was based in Manchukuo during the 1930s and 1940s.

History

Fascism had existed amongst the Manchurian Russians; th ...

and provided identification papers necessary to live, work and travel in Manchukuo. Much more in favor with the Japanese than White General Kislitsin, Semyonov replaced him as BREM's chairman from 1943 to 1945.

Arrest and execution

Semyonov was captured in

Semyonov was captured in Dalian

Dalian ( ) is a major sub-provincial port city in Liaoning province, People's Republic of China, and is Liaoning's second largest city (after the provincial capital Shenyang) and the third-most populous city of Northeast China (after Shenyang ...

by Soviet paratroopers

A paratrooper or military parachutist is a soldier trained to conduct military operations by parachuting directly into an area of operations, usually as part of a large airborne forces unit. Traditionally paratroopers fight only as light inf ...

in September 1945 during the Soviet invasion of Manchuria

The Soviet invasion of Manchuria, formally known as the Manchurian Strategic Offensive Operation or simply the Manchurian Operation () and sometimes Operation August Storm, began on 9 August 1945 with the Soviet Union, Soviet invasion of the Emp ...

in which the Red Army conquered Manchukuo

Manchukuo, officially known as the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of Great Manchuria thereafter, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Northeast China that existed from 1932 until its dissolution in 1945. It was ostens ...

. He was taken to Moscow, and put on trial with seven others, including Rodzaevsky in front of the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR

The Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union () was created in 1924 by the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union as a court for the higher military and political personnel of the Red Army and Fleet. In addition it was an immed ...

. He pleaded guilty to espionage, sabotage, terrorism, and armed struggle, and was sentenced to death by hanging

Hanging is killing a person by suspending them from the neck with a noose or ligature strangulation, ligature. Hanging has been a standard method of capital punishment since the Middle Ages, and has been the primary execution method in numerou ...

. Semyonov was executed on August 29, 1946.

References

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Semyonov, Grigory 1890 births 1946 deaths Russian people of Buryat descent People from Ononsky District People from Transbaikal Oblast Russian military personnel of World War I People of the Russian Civil War White movement lieutenant generals Perpetrators of the White Terror (Russia) Warlords Russian fascists History of Zabaykalsky Krai Primorsky Krai White Russian emigrants to China White Russian emigrants to Japan People from Manchukuo Russian people executed for war crimes Executed White movement generals Executed White Russian collaborators with Imperial Japan Executed mass murderers People executed by the Soviet Union by hanging