Greenback Party on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Greenback Party (known successively as the Independent Party, the National Independent Party and the Greenback Labor Party) was an American political party with an anti-monopoly ideology which was active from 1874 to 1889. The party ran candidates in three

The

The

The late 1860s and early 1870s were a time of frenetic railway construction and associated land speculation. Rather than a managed system of national railroad construction through

The late 1860s and early 1870s were a time of frenetic railway construction and associated land speculation. Rather than a managed system of national railroad construction through

The Greenback Party emerged gradually from the consolidation of like-minded

The Greenback Party emerged gradually from the consolidation of like-minded

The Greenback Party was in decline throughout the entire

The Greenback Party was in decline throughout the entire

''The True Greenback: Or the Way to Pay the National Debt Without Taxes, and Emancipate Labor.''

Chicago: Alexander Campbell, 1868. * McGrane, R. C. (1925).

Ohio and the Greenback Movement

. ''The Mississippi Valley Historical Review''. 11 (4): 526–542. * Peter Cooper, ''The Nomination to the Presidency of Peter Cooper and his Address to the Indianapolis Convention of the National Independent Party.'' New York: Peter Cooper/Trow's Printing and Bookbinding, 1876. * Wesley Clair Mitchell

''A History of the Greenbacks: With Special Reference to the Economic Consequences of Their Issue, 1862-65.''

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1903. * Wesley Clair Mitchell

''Gold, Prices, and Wages under the Greenback Standard.''

Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1908. * Gretchen Ritter, ''Goldbugs and Greenbacks: The Antimonopoly Tradition and the Politics of Finance in America.'' New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997. * {{Historical left-wing third party presidential tickets (U.S.) Defunct political parties in the United States History of Indianapolis Left-wing populism in the United States Political parties established in 1874 Political parties disestablished in 1889 1874 establishments in the United States

presidential elections

A presidential election is the election of any head of state whose official title is President.

Elections by country

Albania

The president of Albania is elected by the Assembly of Albania who are elected by the Albanian public.

Chile

The ...

, in 1876

Events

January

* January 1

** The Reichsbank opens in Berlin.

** The Bass Brewery Red Triangle becomes the world's first registered trademark symbol.

*January 27 – The Northampton Bank robbery occurs in Massachusetts.

February

* Febr ...

, 1880

Events

January

*January 27 – Thomas Edison is granted a patent for the incandescent light bulb. Edison filed for a US patent for an electric lamp using "a carbon filament or strip coiled and connected ... to platina contact wires." gr ...

and 1884

Events January

* January 4 – The Fabian Society is founded in London to promote gradualist social progress.

* January 5 – Gilbert and Sullivan's comic opera '' Princess Ida'', a satire on feminism, premières at the Savoy The ...

, before it faded away.

The party's name referred to the non- gold backed paper money, commonly known as " greenbacks", that had been issued by the North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

and shortly afterward. The party opposed the deflation

In economics, deflation is a decrease in the general price level of goods and services. Deflation occurs when the inflation rate falls below 0% and becomes negative. While inflation reduces the value of currency over time, deflation increases i ...

ary lowering of prices paid to producers that was entailed by a return to a bullion

Bullion is non-ferrous metal that has been refined to a high standard of elemental purity. The term is ordinarily applied to bulk metal used in the production of coins and especially to precious metals such as gold and silver. It comes from ...

-based monetary system, the policy favored by the Republican and Democratic parties. Continued use of unbacked currency, it was believed, would better foster business and assist farmers

A farmer is a person engaged in agriculture, raising living organisms for food or raw materials. The term usually applies to people who do some combination of raising field crops, orchards, vineyards, poultry, or other livestock. A farmer mi ...

by raising prices and making debts easier to pay.

Initially an agrarian organization associated with the policies of the Grange, the organization took the name Greenback Labor Party in 1878 and attempted to forge a farmer–labor alliance by adding industrial reforms to its agenda, such as support of the 8-hour day and opposition to the use of state or private force to suppress union strikes. The organization faded into obscurity in the second half of the 1880s, with its basic program reborn shortly under the aegis of the People's Party, commonly known as the "Populists". Later, during the early 20th century, parts of the agenda from both parties were accomplished by the Progressives.

Organizational history

Background

The

The American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

of 1861 to 1865 greatly affected the financial system of the United States of America, creating vast new war-related expenditures while disrupting the flow of tax revenue from the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is List of regions of the United States, census regions defined by the United States Cens ...

, organized as the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), also known as the Confederate States (C.S.), the Confederacy, or Dixieland, was an List of historical unrecognized states and dependencies, unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United State ...

. The act of Southern secession prompted a brief and severe business panic in the North and a crisis of public confidence in the Federal government.Paul Kleppner, "The Greenback and Prohibition Parties," in Arthur M. Schlesinger (ed.), ''History of U.S. Political Parties: Volume II, 1860-1910, The Gilded Age of Politics.'' New York: Chelsea House/R.R. Bowker Co., 1973; pg. 1552. The government's initial illusions of a quick military victory proved ephemeral and in the wake of Southern victories the federal government found it increasingly difficult to sell the government bonds necessary to finance the war effort.

Two 1861 bond sales of $50 million each conducted through private banks went without a hitch, but bankers found the market for the 7.3% securities soft for a third bond issue. A general fear arose that the country's gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

supply was inadequate and that the nation would soon leave the gold standard

A gold standard is a backed currency, monetary system in which the standard economics, economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the ...

. In December runs on deposits began in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

, forcing banks there to disburse a substantial part of their hard metal reserves. On December 30, 1861, New York banks suspended the redemption of their banknotes with gold. This spontaneous action was followed shortly by banks in other states suspending payment on their own banknotes and the U.S. Treasury

The Department of the Treasury (USDT) is the Treasury, national treasury and finance department of the federal government of the United States. It is one of 15 current United States federal executive departments, U.S. government departments.

...

itself suspending redemption of its own Treasury notes. The gold standard was thus effectively suspended.

United States Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

Salmon P. Chase had already anticipated the coming financial crisis, proposing to Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

the establishment of a system of national banks, each empowered to issue banknotes backed not with gold but with federal bonds. This December 1861 proposal was initially ignored by Congress, which in February 1862 decided instead to pass the First Legal Tender Act, authorizing the production of not more than $150 million of these legal tender United States Note

A United States Note, also known as a Legal Tender Note, is a type of Banknote, paper money that was issued from 1862 to 1971 in the United States. Having been current for 109 years, they were issued for longer than any other form of U.S. paper ...

s. Two additional issues were deemed necessary, approved in June 1862 and January 1863, so that by the end of the war some $450 million of this non-gold-backed currency was in circulation.

The new United States Notes were popularly known as "greenbacks" due to the vibrant green ink used on the reverse side of the bill. A dual currency system emerged in which this fiat money

Fiat money is a type of government-issued currency that is not backed by a precious metal, such as gold or silver, nor by any other tangible asset or commodity. Fiat currency is typically designated by the issuing government to be legal tende ...

circulated side by side with ostensibly gold-backed currency and gold coin, with the value of the former bearing a discount in trade. The greatest differential in value of these currencies came in 1864, when the value of a gold dollar equaled $1.85 in greenback currency.Kleppner, "The Greenback and Prohibition Parties," pg. 1553.

Congress finally enacted Treasury Secretary Chase's National Bank plan in January 1863, creating a yet another form of currency, also backed by government bonds rather than gold and redeemable in United States Notes. This non-gold-based currency became the functional equivalent of greenbacks in circulation, further expanding the money supply.

With the production of consumer goods impacted by the conversion of factories to wartime production and the expansion of the money supply, the United States of America experienced a period of protracted inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the average price of goods and services in terms of money. This increase is measured using a price index, typically a consumer price index (CPI). When the general price level rises, each unit of curre ...

during the Civil War. Between the years 1860 and 1865, the cost of living nearly doubled. As is the case in all inflationary periods, there were winners and losers created by the significant fall in currency value, with banks and creditors receiving less real value from the loans repaid by debtors. Pressure began to build in the financial industry for a rectification of the weak currency situation.

A change of heads at the Treasury Department in March 1865 proved the occasion for a change of course in American monetary policy. New Secretary of the Treasury Hugh McCulloch not only declared himself sympathetic to the banking industry's desire for restoration of a gold-based currency, but he declared the resumption of gold payments to be his primary aim. In December 1865, McCulloch formally sought approval from Congress to retire the greenback currency from circulation, a necessary first step towards restoration of the gold standard. In response, Congress passed the Contraction Act of 1866, calling for the withdrawal of $10 million in United States Notes within the first 6 months and an addition $4 million per month thereafter. Substantial contraction of the physical money supply followed.

About $44 million in greenback currency was successfully withdrawn from circulation before a recession

In economics, a recession is a business cycle contraction that occurs when there is a period of broad decline in economic activity. Recessions generally occur when there is a widespread drop in spending (an adverse demand shock). This may be tr ...

in 1867 helped fuel opposition in Congress to the deflationary redemption program. In February 1868, Congress terminated the Redemption Act and a state of what is today known as gridlock

Gridlock is a form of traffic congestion where continuous queues of vehicles block an entire network of intersecting streets, bringing traffic in all directions to a complete standstill. The term originates from a situation possible in a grid ...

emerged, during which Congress refused to either formally leave the gold standard or to redeem its non-gold currency in circulation. Secretary of the Treasury of the Grant administration

Ulysses S. Grant's tenure as the 18th president of the United States began on March 4, 1869, and ended on March 4, 1877. Grant, a Republican Party (US), Republican, took office after winning the 1868 United States presidential election, 1868 e ...

George S. Boutwell formally abandoned the contraction policy and embraced the ongoing state of political inertia.

Currency policy emerged as a hot topic in national politics, with politically active farmer

A farmer is a person engaged in agriculture, raising living organisms for food or raw materials. The term usually applies to people who do some combination of raising field crops, orchards, vineyards, poultry, or other livestock. A farmer ...

s and representatives of the fledgling national trade union

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

movement endorsing a weak greenback-type currency as conducive to the needs of these groups as debtors.Kleppner, "The Greenback and Prohibition Parties," pg. 1554. A looser currency supply was seen as a way of breaking the perceived stranglehold on the national economy held by banks and wealthy industrialists. Chief among these supporters of so-called "Greenbackism" was the National Labor Union (NLU), established in 1866. This and other groups began to turn to political action

In sociology, social action, also known as Weberian social action, is an act which takes into account the actions and reactions of individuals (or ' agents'). According to Max Weber, "Action is 'social' insofar as its subjective meaning takes acco ...

in 1870 in an effort to advance their political agenda, with an August 1870 convention calling for the establishment of the National Labor Reform Party.

Joining organized labor were the organized farmers in the form of the Patrons of Husbandry, commonly known as the Grange.Kleppner, "The Greenback and Prohibition Parties," pg. 1555. Established in 1867, the Grange concerned itself with the monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek language, Greek and ) is a market in which one person or company is the only supplier of a particular good or service. A monopoly is characterized by a lack of economic Competition (economics), competition to produce ...

power exerted by railroads, which used various aggressive pricing mechanisms for its own benefit against the farmers who shipped commodities over its lines. When the Grangers turned to politics around the start of the 1870s, railroad price reform was chief on its agenda, with currency reform making it easier for debtors to repay their loans a distinctly lesser concern.

The Greenback Party would be an alliance of organized labor and reform-minded farmers intent on toppling the political hegemony of the industrial- and banking-oriented Republican Party which ruled the North during the Reconstruction period.

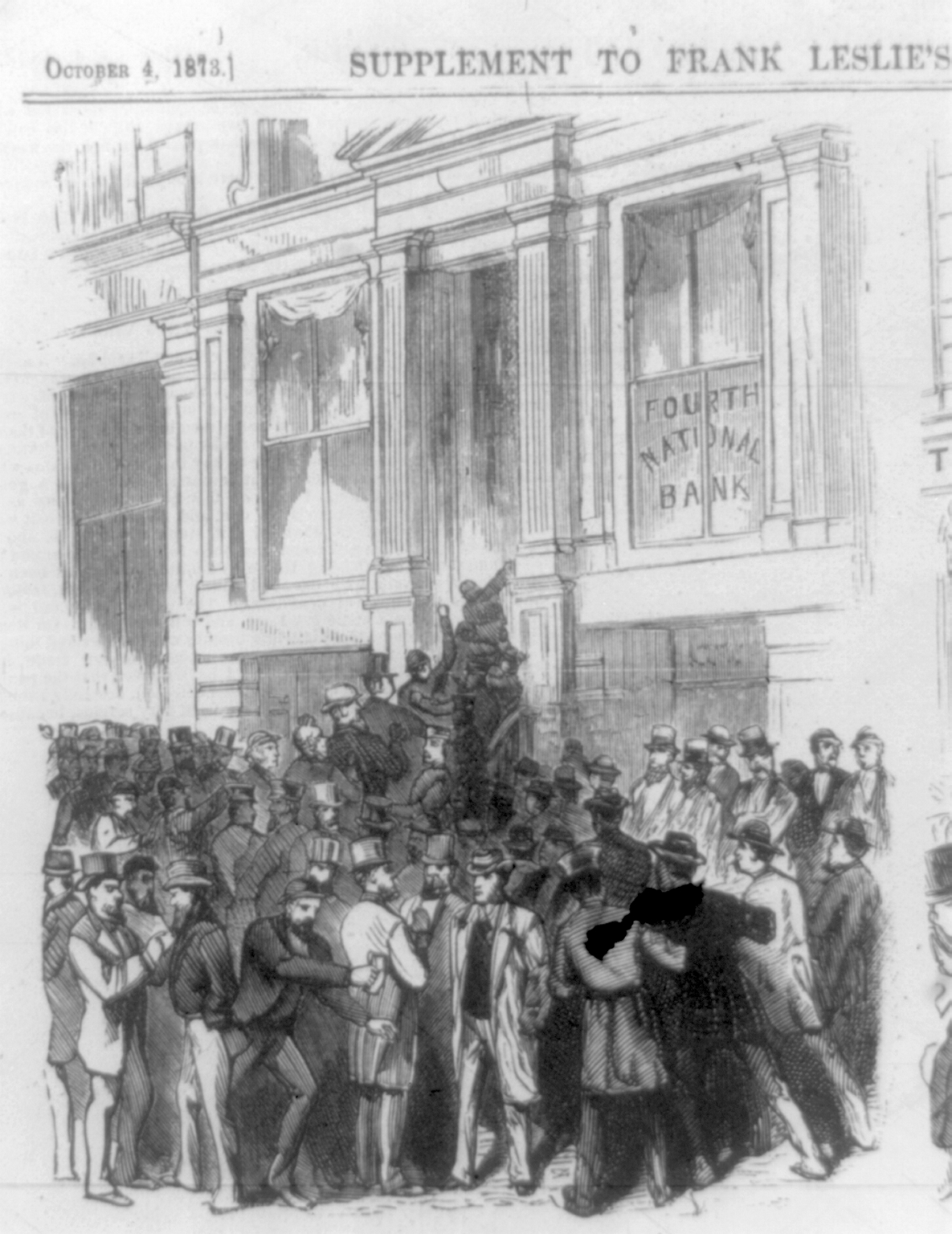

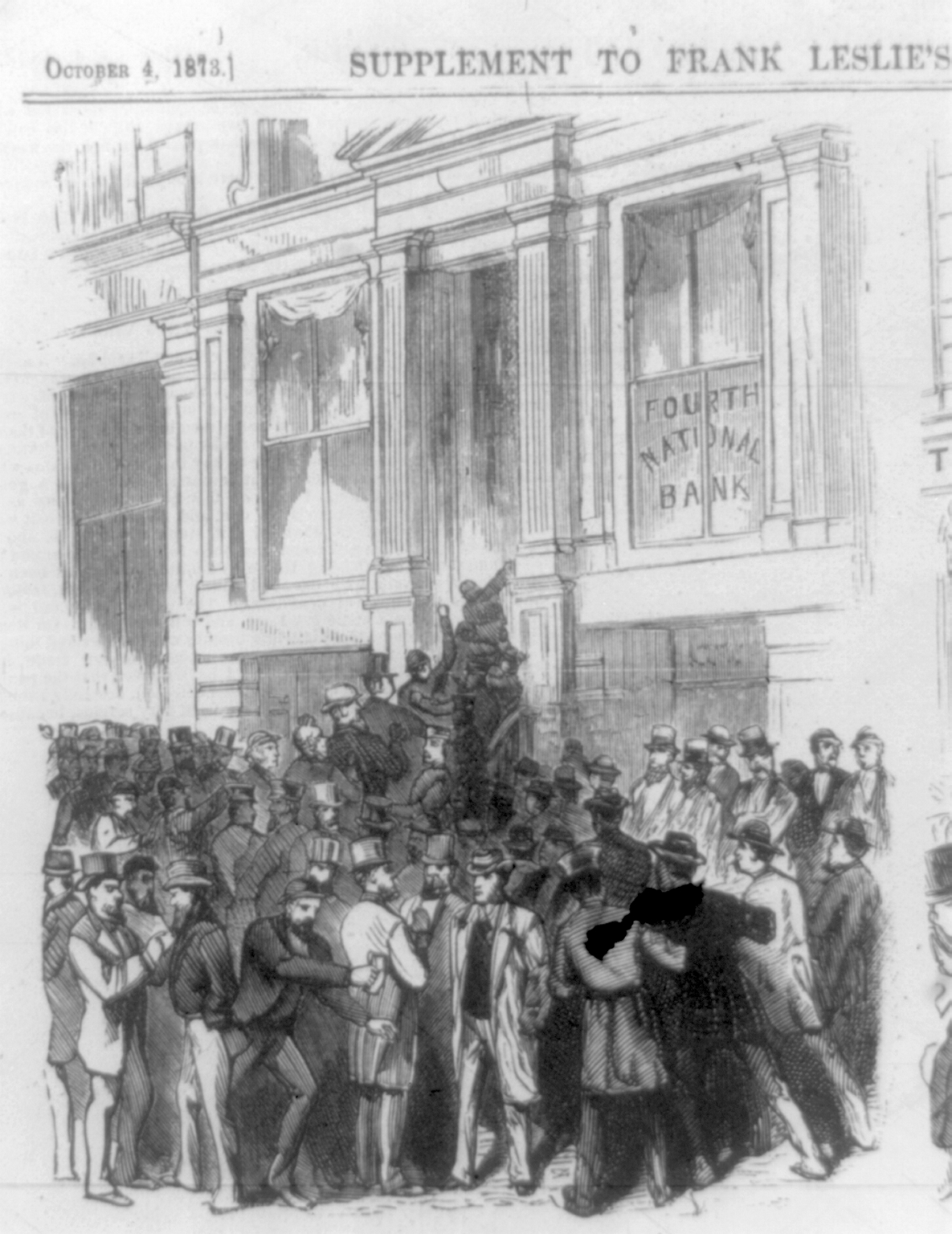

1873 economic crisis and response

The late 1860s and early 1870s were a time of frenetic railway construction and associated land speculation. Rather than a managed system of national railroad construction through

The late 1860s and early 1870s were a time of frenetic railway construction and associated land speculation. Rather than a managed system of national railroad construction through public works

Public works are a broad category of infrastructure projects, financed and procured by a government body for recreational, employment, and health and safety uses in the greater community. They include public buildings ( municipal buildings, ...

or leaving the construction of lines strictly to market forces, Congress attempted to spur the growth of the industry through the grant of enormous tracts of public land

In all modern states, a portion of land is held by central or local governments. This is called public land, state land, or Crown land (Commonwealth realms). The system of tenure of public land, and the terminology used, varies between countries. ...

s to privately owned railway companies. In May 1869, the First transcontinental railroad

America's first transcontinental railroad (known originally as the "Pacific Railroad" and later as the "Overland Route (Union Pacific Railroad), Overland Route") was a continuous railroad line built between 1863 and 1869 that connected the exis ...

across the North American continent was completed, bringing many localities to within reach of a national market for the first time.

A frenzy to complete additional railway lines to open up new frontier areas for development followed, a situation in which the United States government and the great railroad companies of the day maintained a common interest. In an effort to speed such development, Congress granted cash loans and some 129 million acres (52.2 million hectares) of publicly owned land to subsidize construction.John D. Hicks, ''The Populist Revolt: A History of the Crusade for Farm Relief.'' Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1931; pp. 3-4.

A great part of this massive stockpile of land needed to be converted into cash by the railways to finance their building activities, since railroad construction was a costly undertaking. New settlement had to be attracted to the virgin lands west of the Missouri River

The Missouri River is a river in the Central United States, Central and Mountain states, Mountain West regions of the United States. The nation's longest, it rises in the eastern Centennial Mountains of the Bitterroot Range of the Rocky Moun ...

, which had been previously regarded by the public as worthless to the needs of agriculture due to insufficiencies of the soil as well as the arid climate. Millions of advertising dollars were spent by the railway companies promoting the agricultural development of the land which they had to sell.Hicks, ''The Populist Revolt,'' pg. 15. Populations skyrocketed and marginal lands were sold and settled.

In 1873, the economic bubble

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

burst. The Panic began with a crisis in the overextended railroad industry, when the brokerage house Jay Cooke & Company

Jay Cooke & Company was a U.S. bank that operated from 1861 to 1873. Headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, with branches in New York City and Washington, D.C., the bank helped underwrite the American Civil War, Union Civil War effort. It ...

found itself unable to sell enough Northern Pacific Railroad

The Northern Pacific Railway was an important American transcontinental railroad that operated across the northern tier of the Western United States, from Minnesota to the Pacific Northwest between 1864 and 1970. It was approved and chartered b ...

bonds to meet its financial obligations, leading to a default on loans and setting off a financial chain reaction. Runs began on banks, causing a series of bank failures, and manufacturers shuttered their production, laying off workers. Dozens of marginal railroads went bankrupt while unemployment skyrocketed. A lengthy depression ensued, continuing through 1878.Kleppner, "The Greenback and Prohibition Parties," pp. 1555-1556.

Pressure was placed on Congress to alleviate the business crisis through reinflation of the currency, pitting railroad promoters and the iron industry against Eastern bankers and the merchant elite, who favored a stable, gold-based currency.Kleppner, "The Greenback and Prohibition Parties," pp. 1556. Although those favoring currency expansion won the day in Congress, which passed an Inflation Bill calling for a $46 million boost in output of National Bank notes that would raise the ceiling on unbacked currency back to $400 million, the legislation was veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president (government title), president or monarch vetoes a bill (law), bill to stop it from becoming statutory law, law. In many countries, veto powe ...

ed by President Grant on April 22, 1874.

The next Congress moved in the other direction, with the Republican leadership making use of steamroller tactics in order to finally resolve the dual currency situation through passage of the Specie Payment Resumption Act

The Specie Payment Resumption Act of January 14, 1875 was a law in the United States that restored the nation to the gold standard through the redemption of previously unbacked United States Notes and reversed inflationary government policies prom ...

.Kleppner, "The Greenback and Prohibition Parties," pg. 1557. Under the plan the government would accumulate a sufficient gold reserve over the next several years through the sale of interest-bearing bonds for gold, using the accumulated metal to redeem the greenback currency on January 1, 1879. This deflationary move further tightened the already contracting economy, moving currency reform higher on the list of objectives of politically minded farmers.

With the Democratic Party still discredited in the minds of many Northerners for its pro-Southern orientation and the Republican Party dominated by pro-gold interests, conditions had become ripe for the emergence of a new political organization to challenge the political hegemony of the two established parties of American politics.

Establishment

The Greenback Party emerged gradually from the consolidation of like-minded

The Greenback Party emerged gradually from the consolidation of like-minded state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

-level political organizations of differing names. According to historian Paul Kleppner, the origin of the Greenback Party is to be found in the state of Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

, where early in 1873 a group of reform-minded farmers and political activist

A political movement is a collective attempt by a group of people to change government policy or social values. Political movements are usually in opposition to an element of the status quo, and are often associated with a certain ideology. Some ...

s declared themselves free of the two established parties and established themselves as the Independent Party. One of the founding members, John C. Wilde, is cited several times in a northern Michigan newspaper from 1898 explaining the reasons for the beginning of the Party. The group nominated a slate for statewide office, running on a platform which called for expansion of the national currency. (In Wisconsin

Wisconsin ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest of the United States. It borders Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east, Michig ...

in the same year, a short-lived Reform Party, also called Liberal Reform Party or People's Reform Party, a coalition

A coalition is formed when two or more people or groups temporarily work together to achieve a common goal. The term is most frequently used to denote a formation of power in political, military, or economic spaces.

Formation

According to ''A G ...

of Democrats, reform

Reform refers to the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The modern usage of the word emerged in the late 18th century and is believed to have originated from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement, which ...

-minded Republicans, and Grangers secured the election of William Robert Taylor as Governor of Wisconsin

The governor of Wisconsin is the head of government of Wisconsin and the commander-in-chief of the state's Wisconsin Army National Guard, army and Wisconsin Air National Guard, air forces. The governor has a duty to enforce state laws, and the ...

for a two-year term, as well as a number of state legislators, but it never formed a coherent organization.)

The Indiana Independent organization cast its eyes upon a broader existence the following year, issuing a convention call in August 1874 urging all "greenback men" to assemble at Indianapolis

Indianapolis ( ), colloquially known as Indy, is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Indiana, most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the county seat of Marion County, Indiana, Marion ...

in November to form a new national political party. The result of this call was an undelegated gathering of individuals held in November in Indianapolis which was more akin to an organizational conference than a formal convention. No new party was formally established, but a governing Executive Committee was named for the prospective "National Independent Party", with the body assigned the task of composing a declaration of principles and issuing another call for a formal founding convention.

Several regional conventions took place in 1875, merging the activities of local political parties towards a single end. Most of those attending these initial gatherings were farmers or lawyers, with few urban wage workers or trade union officials — the union movement having been shattered and atomized following the Panic of 1873.

The party nominated its first national ticket at a convention held in Indianapolis

Indianapolis ( ), colloquially known as Indy, is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Indiana, most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the county seat of Marion County, Indiana, Marion ...

, Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

in May 1876.Kleppner, "The Greenback and Prohibition Parties," pg. 1551. The party's platform focused upon repeal of the Specie Resumption Act of 1875 and the renewed use of non-gold-backed United States Note

A United States Note, also known as a Legal Tender Note, is a type of Banknote, paper money that was issued from 1862 to 1971 in the United States. Having been current for 109 years, they were issued for longer than any other form of U.S. paper ...

s in an effort to restore prosperity through an expanded money supply

In macroeconomics, money supply (or money stock) refers to the total volume of money held by the public at a particular point in time. There are several ways to define "money", but standard measures usually include currency in circulation (i ...

. The convention nominated New York economics pamphleteer Peter Cooper

Peter Cooper (February 12, 1791April 4, 1883) was an American industrialist, inventor, philanthropist, and politician. He designed and built the first American steam locomotive, the ''Tom Thumb (locomotive), Tom Thumb'', founded the Cooper Union ...

as its presidential standard-bearer.

Cooper declared to the convention:

The Greenback movement argued that the previous effort of using an unbacked currency had been sabotaged by monied interests, which had prevailed upon Congress to restrict the functionality of the notes — declaring them unsuitable for the payment of taxes or national debt.William D.P. Bliss and Rudolph M. Binder (eds.), ''The New Encyclopedia of Social Reform.'' New York: Funk and Wagnalls, 1908; pp. 562-563. This inevitably depreciated the value of the unbacked currency when circulated side by side with fully functional gold-backed notes, the Greenback movement argued. Moreover, this differential in values was exploited by speculators, who purchased unbacked currency at a severe discount with gold-backed notes and then pressured Congress into redemption of the same at a 1-to-1 rate — thereby netting the speculator a tidy profit.

The Greenback Party of 1876 drew the support almost exclusively from farmers — few urban workmen cast ballots for the Greenback ticket.Selig Perlman, "Upheaval and Reorganization (Since 1876)," in John Commons et al. (eds.), ''History of Labour in the United States: Volume 2.'' New York: Macmillan, 1918; pg. 240. The situation changed somewhat in the summer of 1877, however, when a strike movement erupted across the country, leading to the suppression of local strike actions by Federal troops and a radicalization of workers. A myriad of local political organizations, independent not only of the Republican and Democratic Parties but also of the fledgling Greenback Party sprung up around the country, concentrated in the states of Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

, and New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

.

Development

In the late 1870s, the party controlled local government in a number of industrial and mining communities and contributed to the election of 21 members in theUnited States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

independent of the two major parties.Foner, ''Give Me Liberty!'' vol. 2, pg. 532. The movement found particular success at the 1874 elections in Wisconsin, California, Iowa and Kansas.

This led the ''Chicago Weekly Tribune'' to state that the movement offered, "an opportunity to accomplish something for the country at large — not for the farmers merely, but for all who live by their industry, as distinguished from those who live by politics, speculations and class-legislation." Frustrated by their inability to get Democrats or Republicans to adopt inflationary monetary policy, southern and western leaders of monetary reform met in Indianapolis and proposed the creation of a new political party for currency reform. They would meet again in Cleveland to formally launch the Greenback Party in 1875. The Greenbackers condemned the National Banking System, created by the National Banking Act of 1863, the harmonization of the silver dollar (Coinage Act of 1873

The Coinage Act of 1873 or Mint Act of 1873 was a general revision of laws relating to the Mint of the United States. By ending the right of holders of silver bullion to have it coined into standard silver dollars, while allowing holders of g ...

was in fact the "Crime of '73" to Greenback), and the Resumption Act of 1875, which mandated that the U.S. Treasury issue specie (coinage or "hard" currency) in exchange for greenback currency upon its presentation for redemption beginning on January 1, 1879, thus returning the nation to the gold standard. Together, these measures created an inflexible currency controlled by banks rather than the federal government. Greenbacks contended that such a system favored creditors and industry to the detriment of farmers and laborers.

In 1880, the Greenback Party broadened its platform to include support for an income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Tax ...

, an eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses of working time.

The modern movement originated i ...

, and allowing women the right to vote. Ideological similarities also existed between the Grange (The National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry

The National Grange, also known as The Grange and officially named The National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry, is a social organization in the United States that encourages families to band together to promote the economic and pol ...

) and the Greenback movement. For example, both the Grange and the GAP favored a national graduated income tax and proposed that public lands be given to settlers rather than sold to land speculators.Hild, ''Greenback, Knights of Labor, and Populists,'' pg. 22. The town of Greenback, Tennessee, was named after the Greenback Party about 1882.

The party seems to have made use of slightly different official names in some states, with the organization appearing on the ballot in the November 1880 Sacramento

Sacramento ( or ; ; ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of California and the seat of Sacramento County. Located at the confluence of the Sacramento and American Rivers in Northern California's Sacramento Valley, Sacramento's 2020 p ...

, California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

city election as the "Greenback Labor and Socialist Party".

Among its national spokesmen, although not the best known, was Thomas Ewing, Jr., a noted Free State advocate in Kansas before the civil war, a controversial major general of Union forces during the war, and a Republican turned Democrat after the Grant Administration. His national debates on Greenback monetary policy led the party's growth and influence as spokesmen against the post-war redevelopment of monopolistic gold-based capitalism. Ewing's advice to Andrew Johnson had helped point the administration towards an anti-gold-standard Treasury department.

Ewing served in Congress from 1877 to 1881 during the Hayes administration as a leading spokesman for those national politicians who wanted the nation's money supply used to expand commerce and fund westward expansion of the nation, not repay in gold the interest on civil war bonds Eastern bankers had bought to fund much of the civil war effort but whose antebellum lending practices to the South had helped slavery flourish. His 1875 national debates with hard money New York Governor Stewart L. Woodford set the stage for a rapid but brief rise in party national influence.

Decline and dissolution

The Greenback Party was in decline throughout the entire

The Greenback Party was in decline throughout the entire Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

administration. In the election of 1884, the party failed to win any House

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air c ...

seats outright, although they did win one seat in conjunction with Plains States Democrats, James B. Weaver, as well as a handful of other seats by endorsing the Democratic nominee.

In the election of 1886, only two dozen Greenback candidates ran for the House, apart from another six who ran on fusion tickets. Again, Weaver was the party's only victory. Much of the Greenback news in early 1888 took place in Michigan, where the party remained active.

In early 1888, it was not clear if the Greenback Party would hold another national convention. The 4th Greenback Party National Convention assembled in Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ; colloquially nicknamed Cincy) is a city in Hamilton County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. Settled in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking River (Kentucky), Licking and Ohio Ri ...

, Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

, on May 16, 1888. There were so few delegates who attended that no actions were taken. On August 16, 1888, George O. Jones, chairman of the national committee, called a second session of the national convention. The second session of the national convention met in Cincinnati on September 12, 1888. Only seven delegates attended. Chairman Jones issued an address criticizing the two major parties, and the delegates made no nominations. With the failure of the convention, the Greenback Party ceased to exist.

Legacy

Many Greenback activists, including 1880 Presidential nominee James B. Weaver, later participated in the Populist Party. By the middle of the 1880s, Greenback Labor nationally was losing its labor-based support, in part as a result ofcraft union

Craft unionism refers to a model of trade unionism in which workers are organised based on the particular craft or trade in which they work. It contrasts with industrial unionism, in which all workers in the same industry are organized into the sa ...

voluntarism and in part as a result of Irish defections back to the Democratic Party.

Historian Paul Kleppner has observed that one of the traditional functions of third parties in the American political system has been the raising of new issues, the testing of their viability amongst the electorate, and the pressuring of established political parties to appropriate these issues as part of their own electoral agenda.Kleppner, "The Greenback and Prohibition Parties," pg. 1550. In this the Greenback Party and the People's Party which followed it were ultimately successful, moving the Democratic Party to espouse looser monetary policy and an ultimate abandonment of the gold standard.

Conventions

Presidential tickets

Elected officials

The following were Greenback members of theU.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Article One of th ...

:

46th United States Congress

The 46th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1879 ...

, March 4, 1879 - March 3, 1881.

* William M. Lowe (1842–1882), Alabama's 8th congressional district

* Albert P. Forsythe (1830–1906), Illinois's 15th congressional district

The 15th congressional district of Illinois is currently located in central Illinois.

It was located in eastern and southeastern Illinois until 2022. It is currently represented by Republican Party (United States), Republican Mary Miller (poli ...

* Gilbert De La Matyr (1825–1892), "National" Indiana's 7th congressional district

* James B. Weaver (1833–1912), Iowa's 6th congressional district

Iowa's 6th congressional district is a former List of United States congressional districts, U.S. congressional district in the Iowa, State of Iowa. It existed in elections from 1862 to 1992, when it was lost due to Iowa's population growth rate ...

* Edward H. Gillette (1840–1918), Iowa's 7th congressional district

* George W. Ladd

George Washington Ladd (September 28, 1818 – January 30, 1892) was a United States House of Representatives, U.S. Representative from Maine.

Life history

Ladd was born on September 28, 1818 to Joseph and Sarah (Hamlin) Ladd in Augusta, Main ...

(1818–1892), Maine's 4th congressional district

* Thompson H. Murch (1838–1886), Maine's 5th congressional district

* Nicholas Ford (1833–1897), Missouri's 9th congressional district

* Daniel Lindsay Russell (1845–1908), North Carolina's 3rd congressional district

North Carolina's 3rd congressional district is located on the East Coast of the United States, Atlantic coast of North Carolina. It covers the Outer Banks and the counties adjacent to the Pamlico Sound.

The district is currently represented by ...

* Hendrick B. Wright, Pennsylvania's 12th congressional district

* Seth H. Yocum (1834–1895), Pennsylvania's 20th congressional district

* George Washington Jones (1828–1903), Texas's 5th congressional district

* Bradley Barlow (1814–1889), Vermont's 3rd congressional district

47th United States Congress

The 47th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1881, ...

, March 4, 1881, to March 3, 1883.

* William M. Lowe, Alabama's 8th congressional district.—Seated June 3, 1882, subsequently died August 12, 1882.

* George W. Ladd

George Washington Ladd (September 28, 1818 – January 30, 1892) was a United States House of Representatives, U.S. Representative from Maine.

Life history

Ladd was born on September 28, 1818 to Joseph and Sarah (Hamlin) Ladd in Augusta, Main ...

, Maine's 4th congressional district

* Thompson H. Murch, Maine's 5th congressional district

* Ira S. Hazeltine Missouri's 6th congressional district

Missouri's 6th congressional district takes in a large swath of land in northern Missouri, stretching across nearly the entire width of the state from Kansas to Illinois. Its largest voting population is centered in the northern portion of the ...

* Theron M. Rice Missouri's 7th congressional district

* Nicholas Ford, Missouri's 9th congressional district

* Joseph H. Burrows Missouri's 10th congressional district

* Charles N. Brumm, Pennsylvania's 13th congressional district

* James Mosgrove, Pennsylvania's 25th congressional district

Pennsylvania's 25th congressional district was one of Pennsylvania's districts of the United States House of Representatives.

Geography

In 1903, the district was drawn to cover Crawford County, Pennsylvania, Crawford and Erie County, Pennsylvan ...

* George Washington Jones, Texas' 5th congressional district

48th United States Congress

The 48th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C., from March 4, 1883, ...

, March 4, 1883, to March 3, 1885.

* Benjamin F. Shively, Anti-Monopolist Indiana's 13th congressional district

* Luman Hamlin Weller, Iowa's 4th congressional district

Iowa's 4th congressional district is a List of United States congressional districts, congressional district in the U.S. state of Iowa that covers the western border of the state, including Sioux City, Iowa, Sioux City and Council Bluffs, Iowa, C ...

* Charles N. Brumm, Pennsylvania's 13th congressional district

49th United States Congress

The 49th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C., from March 4, 188 ...

, March 4, 1885, to March 3, 1887.

* James Weaver, Iowa's 6th congressional district

50th United States Congress

The 50th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C., from March 4, 1887 ...

, March 4, 1887, to March 3, 1889.

* James Weaver, Iowa's 6th congressional district

Other elected officials

* Harriel G. Geiger, lawyer and state legislator in Texas * Robert A. Kerr, state legislator in TexasSee also

* Producerism *United States Note

A United States Note, also known as a Legal Tender Note, is a type of Banknote, paper money that was issued from 1862 to 1971 in the United States. Having been current for 109 years, they were issued for longer than any other form of U.S. paper ...

* List of political parties in the United States

This list of political parties in the United States, both past and present, does not include independents.

Not all states allow the public to access voter registration data. Therefore, voter registration data should not be taken as the correct ...

* List of 19th century American labor parties

Footnotes

Further reading

* Don C. Barrett, ''The Greenbacks and Resumption of Specie Payments, 1862-1879.'' Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1931. * Alexander Campbell''The True Greenback: Or the Way to Pay the National Debt Without Taxes, and Emancipate Labor.''

Chicago: Alexander Campbell, 1868. * McGrane, R. C. (1925).

Ohio and the Greenback Movement

. ''The Mississippi Valley Historical Review''. 11 (4): 526–542. * Peter Cooper, ''The Nomination to the Presidency of Peter Cooper and his Address to the Indianapolis Convention of the National Independent Party.'' New York: Peter Cooper/Trow's Printing and Bookbinding, 1876. * Wesley Clair Mitchell

''A History of the Greenbacks: With Special Reference to the Economic Consequences of Their Issue, 1862-65.''

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1903. * Wesley Clair Mitchell

''Gold, Prices, and Wages under the Greenback Standard.''

Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1908. * Gretchen Ritter, ''Goldbugs and Greenbacks: The Antimonopoly Tradition and the Politics of Finance in America.'' New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997. * {{Historical left-wing third party presidential tickets (U.S.) Defunct political parties in the United States History of Indianapolis Left-wing populism in the United States Political parties established in 1874 Political parties disestablished in 1889 1874 establishments in the United States