Giulio Andreotti on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Giulio Andreotti ( ; ; 14 January 1919 – 6 May 2013) was an Italian politician and

Andreotti did not shine at his school and started work in a tax office while studying law at the University of Rome. In this period he became a member of the Italian Catholic Federation of University Students (FUCI), the only non-

Andreotti did not shine at his school and started work in a tax office while studying law at the University of Rome. In this period he became a member of the Italian Catholic Federation of University Students (FUCI), the only non-

In 1954, Andreotti became

In 1954, Andreotti became

Andreotti's third cabinet was called "the government of the "not- no confidence", because it was externally supported by all the political parties in the Parliament, except for the neo-fascist

Andreotti's third cabinet was called "the government of the "not- no confidence", because it was externally supported by all the political parties in the Parliament, except for the neo-fascist

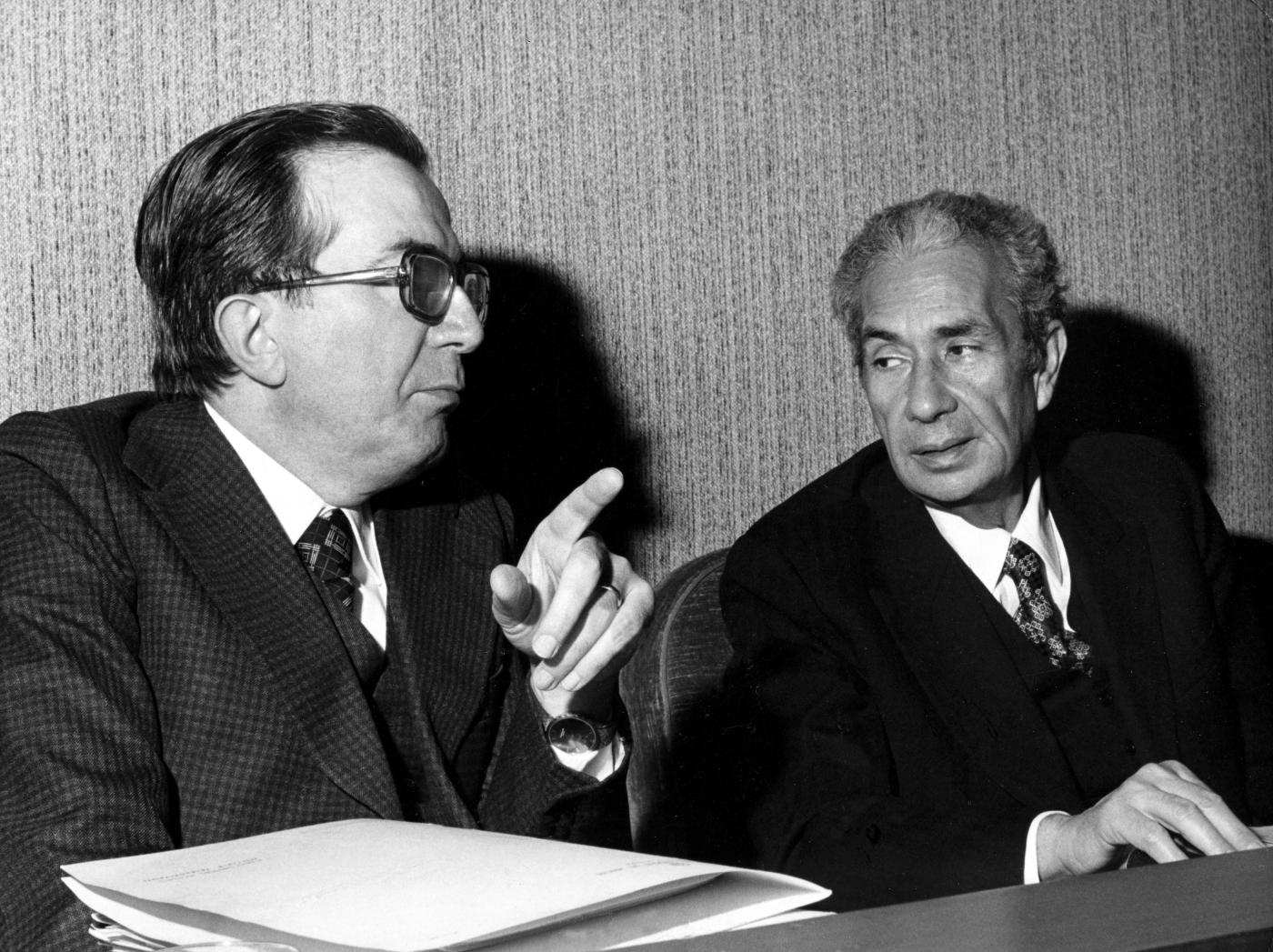

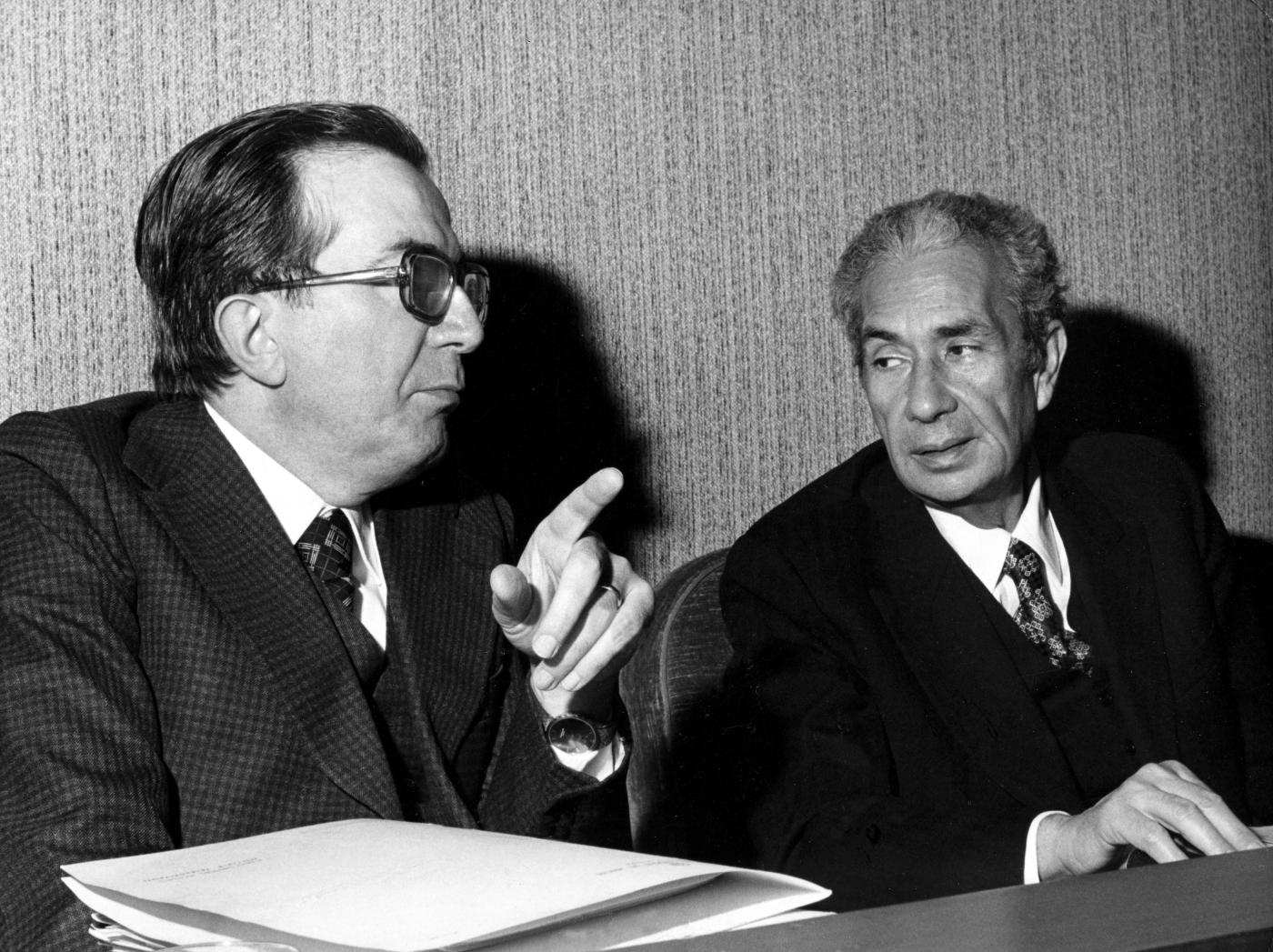

On the morning of 16 March 1978, the day on which the new Andreotti cabinet was supposed to have undergone a

On the morning of 16 March 1978, the day on which the new Andreotti cabinet was supposed to have undergone a

On 7 October 1985, four men representing the Palestine Liberation Front (PLF) hijacked the Italian MS ''Achille Lauro'' liner off the coast of

On 7 October 1985, four men representing the Palestine Liberation Front (PLF) hijacked the Italian MS ''Achille Lauro'' liner off the coast of

Andreotti joined the PPI of Mino Martinazzoli. In 2001, after the creation of The Daisy, Andreotti abandoned the People's Party and joined the European Democracy, a minor

Andreotti joined the PPI of Mino Martinazzoli. In 2001, after the creation of The Daisy, Andreotti abandoned the People's Party and joined the European Democracy, a minor

Andreotti came under suspicion because his relatively small faction within the Christian Democrats included Sicilian Salvatore Lima. In Sicily, Lima cooperated with a

Andreotti came under suspicion because his relatively small faction within the Christian Democrats included Sicilian Salvatore Lima. In Sicily, Lima cooperated with a

in JSTOR

("The Andreotti trials in Italy") by Philippe Foro, published by University of

Il Divo

a Paolo Sorrentino Film *

{{DEFAULTSORT:Andreotti, Giulio 1919 births 2013 deaths Bancarella Prize winners Christian Democracy (Italy) politicians Deputies of Legislature I of Italy Deputies of Legislature II of Italy Deputies of Legislature III of Italy Deputies of Legislature IV of Italy Deputies of Legislature V of Italy Deputies of Legislature VI of Italy Deputies of Legislature VII of Italy Deputies of Legislature VIII of Italy Deputies of Legislature IX of Italy Deputies of Legislature X of Italy European Democracy politicians Ministers of finance of Italy Ministers of foreign affairs of Italy Grand Crosses 1st class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Italian anti-communists Italian life senators Ministers of defence of Italy Ministers of the interior of Italy Italian People's Party (1994) politicians Italian Roman Catholics Members of the Order of the Holy Sepulchre Knights of Malta Members of the Constituent Assembly of Italy Members of the National Council (Italy) Overturned convictions in Italy People acquitted of murder Politicians from Rome Presidents of the European Council Presidents of the Organising Committees for the Olympic Games Prime ministers of Italy Sapienza University of Rome alumni Union of the Centre (2002) politicians Burials at Campo Verano Political controversies in Italy

statesman

A statesman or stateswoman is a politician or a leader in an organization who has had a long and respected career at the national or international level, or in a given field.

Statesman or statesmen may also refer to:

Newspapers United States

...

who served as the 41st prime minister of Italy

The prime minister of Italy, officially the president of the Council of Ministers (), is the head of government of the Italy, Italian Republic. The office of president of the Council of Ministers is established by articles 92–96 of the Co ...

in seven governments (1972–1973, 1976–1979, and 1989–1992), and was leader of the Christian Democracy

Christian democracy is an ideology inspired by Christian social teaching to respond to the challenges of contemporary society and politics.

Christian democracy has drawn mainly from Catholic social teaching and neo-scholasticism, as well ...

party and its right-wing; he was the sixth-longest-serving prime minister since the Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the annexation of various states of the Italian peninsula and its outlying isles to the Kingdom of ...

and the second-longest-serving post-war prime minister. Andreotti is widely considered the most powerful and prominent politician of the First Republic.

Beginning as a protégé of Alcide De Gasperi

Alcide Amedeo Francesco De Gasperi (; 3 April 1881 – 19 August 1954) was an Italian politician and statesman who founded the Christian Democracy party and served as prime minister of Italy in eight successive coalition governments from 1945 t ...

, Andreotti achieved cabinet rank at a young age and occupied all the major offices of the state over the course of a 40-year political career, being seen as a reassuring figure by the civil service, the business community, and the Vatican. Domestically, he contained inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the average price of goods and services in terms of money. This increase is measured using a price index, typically a consumer price index (CPI). When the general price level rises, each unit of curre ...

following the 1973 oil crisis

In October 1973, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) announced that it was implementing a total oil embargo against countries that had supported Israel at any point during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, which began after Eg ...

, founded the National Healthcare Service (''Sistema Sanitario Nazionale'') and combated terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of violence against non-combatants to achieve political or ideological aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violence during peacetime or in the context of war aga ...

during the Years of Lead. In foreign policy, he guided Italy's European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

integration and established closer relations with the Arab world. Admirers of Andreotti saw him as having mediated political and social contradictions, enabling the transformation of a substantially rural country into the world's fifth-largest economy. Critics said he had done nothing to challenge a system of patronage that had led to pervasive corruption. Andreotti staunchly supported the Vatican and a capitalist structure and opposed the Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party (, PCI) was a communist and democratic socialist political party in Italy. It was established in Livorno as the Communist Party of Italy (, PCd'I) on 21 January 1921, when it seceded from the Italian Socialist Part ...

. Following the popular Italian sentiment of the time, he supported the development of a strong European community playing host to neoliberal

Neoliberalism is a political and economic ideology that advocates for free-market capitalism, which became dominant in policy-making from the late 20th century onward. The term has multiple, competing definitions, and is most often used pej ...

economics. He was not opposed to the implementation of the European Social Fund

The European Social Fund Plus (ESF+) is one of the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIFs), which are dedicated to improving social cohesion and economic well-being across the regions of the Union. The funds are redistributive financi ...

and the European Regional Development Fund

The European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) is one of the European Structural and Investment Funds allocated by the European Union. Its purpose is to transfer money from richer regions (not countries), and invest it in the infrastructure and se ...

in building the European economy.

At the height of his statesman career, Andreotti was subjected to criminal prosecutions and charged with colluding with ''Cosa Nostra

The Sicilian Mafia or Cosa Nostra (, ; "our thing"), also referred to as simply Mafia, is a criminal society and criminal organization originating on the island of Sicily and dates back to the mid-19th century. Emerging as a form of local protect ...

''. Courts managed to prove that he was undoubtedly linked with them until 1980; however, the case was closed due to past statutes of limitations. The most sensational allegation came from prosecutors in Perugia

Perugia ( , ; ; ) is the capital city of Umbria in central Italy, crossed by the River Tiber. The city is located about north of Rome and southeast of Florence. It covers a high hilltop and part of the valleys around the area. It has 162,467 ...

, who charged him with ordering the murder of a journalist. He was found guilty at a trial, which led to complaints that the justice system had "gone mad". After being acquitted of all charges, in part due to statute-barred limitations, Andreotti remarked: "Apart from the Punic Wars

The Punic Wars were a series of wars fought between the Roman Republic and the Ancient Carthage, Carthaginian Empire during the period 264 to 146BC. Three such wars took place, involving a total of forty-three years of warfare on both land and ...

, for which I was too young, I have been blamed for everything that's happened in Italy."

In addition to his prime ministerial posts, Andreotti served in numerous ministerial positions, among them as Minister of the Interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

(1954 and 1978), Minister of Finance

A ministry of finance is a ministry or other government agency in charge of government finance, fiscal policy, and financial regulation. It is headed by a finance minister, an executive or cabinet position .

A ministry of finance's portfolio ...

(1955–1958), Minister of Treasury (1958–1959), Minister of Defence

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is the part of a government responsible for matters of defence and military forces, found in states where the government is divid ...

(1959–1966 and 1974), Minister of Budget and Economic Planning (1974–1976), and Minister of Foreign Affairs

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and foreign relations, relations, diplomacy, bilateralism, ...

(1983–1989), and was a senator for life from 1991 until his death in 2013. He was also a journalist and author. Andreotti was sometimes called ''Divo Giulio'' (from Latin ''Divus Iulius'', "Divine Julius", an epithet

An epithet (, ), also a byname, is a descriptive term (word or phrase) commonly accompanying or occurring in place of the name of a real or fictitious person, place, or thing. It is usually literally descriptive, as in Alfred the Great, Suleima ...

of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

after his posthumous deification), or simply ''Il divo''.

Background and attributes

Andreotti, the youngest of three children, was born on 14 January 1919 inRome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

. His father, who died when Giulio was two, was a primary school teacher from Segni

Segni (, ) is an Italian town and ''comune'' located in Lazio. The city is situated on a hilltop in the Lepini Mountains and overlooks the valley of the Sacco River.

History

Early history

According to ancient Roman sources, Lucius Tarquinius ...

, a small town in Lazio

Lazio ( , ; ) or Latium ( , ; from Latium, the original Latin name, ) is one of the 20 Regions of Italy, administrative regions of Italy. Situated in the Central Italy, central peninsular section of the country, it has 5,714,882 inhabitants an ...

; after a few years his sister Elena also died. Andreotti attended the Liceo Torquato Tasso in Rome and graduated in law at the University of Rome, with a mark of 110/110.

Andreotti showed some ferocity as a youth, once stubbing out a lit taper in the eye of another altar boy who was ridiculing him. His mother was described as not very affectionate. An aunt is said to have advised him to remember that few things in life are important and never to over-dramatise difficulties. As an adult, he was described as having a somewhat unusual demeanour for an Italian politician, being mild-mannered and unassuming. Andreotti did not use his influence to advance his children to prominence, despite being widely considered the most powerful person in the country for decades. "See all, tolerate much, and correct one thing at a time" was a quote that emphasised what has been called his "art of the possible" view of politics.

Andreotti was known for his discretion and retentive memory, and also a sense of humour, often placing things in perspective with a sardonic quip. Andreotti's personal support within the Christian Democrats was limited, but he could see where the mutual advantage for apparently conflicting interests lay and put himself at the centre of events as mediator. Though not a physically imposing man, Andreotti navigated political waters through conversational skill.

Early political career

Andreotti did not shine at his school and started work in a tax office while studying law at the University of Rome. In this period he became a member of the Italian Catholic Federation of University Students (FUCI), the only non-

Andreotti did not shine at his school and started work in a tax office while studying law at the University of Rome. In this period he became a member of the Italian Catholic Federation of University Students (FUCI), the only non-fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

youth organization which was allowed by the regime of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

. Its members included many of the future leaders of Christian Democracy

Christian democracy is an ideology inspired by Christian social teaching to respond to the challenges of contemporary society and politics.

Christian democracy has drawn mainly from Catholic social teaching and neo-scholasticism, as well ...

.

In 1938, while researching the papal navy in the Vatican library, he met Alcide De Gasperi

Alcide Amedeo Francesco De Gasperi (; 3 April 1881 – 19 August 1954) was an Italian politician and statesman who founded the Christian Democracy party and served as prime minister of Italy in eight successive coalition governments from 1945 t ...

, who had been given sanctuary by the Pope. De Gasperi asked Andreotti if he had nothing better to do with his time, inspiring him to become politically active. Speaking of De Gasperi, Andreotti said, "He taught us to search for compromise, to mediate."

In July 1939, while Aldo Moro

Aldo Moro (; 23 September 1916 – 9 May 1978) was an Italian statesman and prominent member of Christian Democracy (Italy), Christian Democracy (DC) and its centre-left wing. He served as prime minister of Italy in five terms from December 1963 ...

was president of FUCI, Andreotti became director of its magazine ''Azione Fucina''. In 1942, when Moro was enrolled in the Italian Army, Andreotti succeeded him as president of FUCI, a position he held until 1944. During his early years, Andreotti suffered violent migraine

Migraine (, ) is a complex neurological disorder characterized by episodes of moderate-to-severe headache, most often unilateral and generally associated with nausea, and light and sound sensitivity. Other characterizing symptoms may includ ...

s that forced him to make use of psychoactive drugs sporadically and opiate

An opiate is an alkaloid substance derived from opium (or poppy straw). It differs from the similar term ''opioid'' in that the latter is used to designate all substances, both natural and synthetic, that bind to opioid receptors in the brain ( ...

s. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Andreotti wrote for the ''Rivista del Lavoro'', a fascist propaganda publication, but was also a member of the then-clandestine newspaper ''Il Popolo''.

In July 1943, Andreotti contributed, along with Mario Ferrari Aggradi, Paolo Emilio Taviani

Paolo Emilio Taviani (6 November 1912 – 18 June 2001) was an Italian political leader, economist, and historian of the career of Christopher Columbus. He was a partisan leader in Liguria, a Gold Medal of the Italian resistance movement, then a ...

, Guido Gonella, Giuseppe Capogrossi, Ferruccio Pergolesi, Vittore Branca, Giorgio La Pira, Giuseppe Medici and Moro, to the creation of the Code of Camaldoli, a document planning of economic policy drawn up by members of the Italian Catholic forces. The Code served as inspiration and guideline for economic policy of the future Christian Democrats. In 1944, he became a member of the National Council of the newborn Christian Democracy party. After the end of the conflict, he became responsible for the party's youth organisation.

Chamber of Deputies and government

In 1946, Andreotti was elected to theConstituent Assembly of Italy

The Italian Constituent Assembly ( Italian: ''Assemblea Costituente della Repubblica Italiana'') was a parliamentary chamber which existed in Italy from 25 June 1946 until 31 January 1948. It was tasked with writing a constitution for the Ital ...

, the provisional parliament which had the task of writing the new Italian constitution. His election was supported by Alcide De Gasperi

Alcide Amedeo Francesco De Gasperi (; 3 April 1881 – 19 August 1954) was an Italian politician and statesman who founded the Christian Democracy party and served as prime minister of Italy in eight successive coalition governments from 1945 t ...

, founder of the modern DC, of whom Andreotti became a close assistant and advisor; the two politicians became close friends despite their very different characters. However, De Gasperi later described Andreotti as a man "so capable in everything that he could become capable of anything". In 1948, he was elected to the newly formed Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourb ...

to represent the constituency of Rome–Viterbo–Latina–Frosinone, which remained his stronghold until the 1990s.

Andreotti began his government career in 1947 when he became Secretary of the Council of Ministers in the cabinet of his patron De Gasperi. The appointment was also supported by Giovanni Battista Montini, who later would become Pope Paul VI. During the office, Andreotti had wider-ranging responsibilities than many full ministers, which caused some envy. Andreotti's main undertaking was representing the interests of Frosinone

Frosinone (; local dialect: ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Italian region of Lazio, administrative seat of the province of Frosinone. It is about southeast of Rome, close to the Rome-Naples A1 Motorway. The city is the main city of th ...

in the province of Lazio

Lazio ( , ; ) or Latium ( , ; from Latium, the original Latin name, ) is one of the 20 Regions of Italy, administrative regions of Italy. Situated in the Central Italy, central peninsular section of the country, it has 5,714,882 inhabitants an ...

. Lazio

Lazio ( , ; ) or Latium ( , ; from Latium, the original Latin name, ) is one of the 20 Regions of Italy, administrative regions of Italy. Situated in the Central Italy, central peninsular section of the country, it has 5,714,882 inhabitants an ...

would continue to serve as Andreotti's geographical base of power later in his political career.

Influence on culture

As the state undersecretary in charge of entertainment in 1949, Andreotti established import limits and screen quotas, and provided loans to Italian production firms. The measures aimed to prevent American productions from dominating the market against Neorealist films, a genre that exhibitors complained lacked stars and was held in low esteem by the public. As he phrased it, there were to be 'Less rags, more legs'. Raunchy comedies and historical dramas with voluptuous toga-clad actresses became the staple of the Italian film industry. The screenplays were vetted to ensure that state funds were not used to prop up commercially unsustainable films, thereby creating a form of preproduction censorship. It was intended that Italian studios use part of their profits for high-quality films; However,Vittorio De Sica

Vittorio De Sica ( , ; 7 July 1901 – 13 November 1974) was an Italian film director and actor, a leading figure in the neorealist movement.

Widely considered one of the most influential filmmakers in the history of cinema, four of the fil ...

's '' Umberto D.'', which depicted the lonely life of a retired man, could only strike government officials as a dangerous throwback, due to the opening scene featuring police breaking up a demonstration of old pensioners and the ending scene featuring Umberto's aborted suicide attempt. In a public letter to De Sica, Andreotti castigated him for his "wretched service to his fatherland".

1950s and 1960s

In 1952, ahead of local elections in the municipality of Rome, Andreotti gave proof of his diplomatic skills and gained credibility. Andreotti persuaded De Gasperi not to establish a political alliance with the neo-fascistItalian Social Movement

The Italian Social Movement (, MSI) was a neo-fascist political party in Italy. A far-right party, it presented itself until the 1990s as the defender of Italian fascism's legacy, and later moved towards national conservatism. In 1972, the Itali ...

, as Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII (; born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli; 2 March 18769 October 1958) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death on 9 October 1958. He is the most recent p ...

asked, to prevent a Communist victory.

As Secretary, Andreotti contributed to the re-formation of the Italian Olympic Committee, which had been disbanded after the fall of the Fascist regime. In 1953, among other things, he promoted the so-called "Andreotti's veto" against foreign football players in Italian Serie A.

After De Gasperi's resignation and retirement in August 1953, Andreotti remained Secretary of the Council under the short-lived premiership of Giuseppe Pella.

In 1954, Andreotti became

In 1954, Andreotti became Minister of the Interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

in the first government of Amintore Fanfani

Amintore Fanfani (; 6 February 1908 – 20 November 1999) was an Italian politician and statesman, who served as 32nd prime minister of Italy for five separate terms. He was one of the best-known Italian politicians after the Second World War an ...

. From July 1956 to July 1958, he was appointed Finance Minister in the cabinets of Antonio Segni and Adone Zoli. In the same period, Andreotti started forming a ''corrente'' (unofficial political association, or a faction) within the Christian Democracy party, the largest party in Italy. His ''corrente'' was supported by the Roman Catholic right wing. It started its activity with a press campaign accusing Piero Piccioni

Piero Piccioni (; December 6, 1921 – July 23, 2004) was an Italian film score composer.

A pianist, organist, conductor, and composer, he was also the prolific author of more than 300 film soundtracks. He played for the first time on radio in ...

, son of the deputy national secretary of the DC, Attilio Piccioni

Attilio Piccioni (14 July 1892 – 10 March 1976) was an Italian politician. He had been a prominent member of the Christian Democracy.

Biography

Piccioni was born on 14 July 1892 in Poggio Bustone (Province of Rieti, Umbria) and graduate ...

, of the murder of fashion model Wilma Montesi at Torvaianica. After the defeat of De Gasperi's old followers in the DC National Council, Andreotti helped another newly formed ''corrente'', the ''Dorotei'', to oust Amintore Fanfani, who was the leader of the left wing of the party, as Prime Minister of Italy and National Secretary of the DC. On 20 November 1958 Andreotti, then Minister of Treasury, was appointed president of the organizing committee of the 1960 Summer Olympics

The 1960 Summer Olympics (), officially known as the Games of the XVII Olympiad () and commonly known as Rome 1960 (), were an international multi-sport event held from 25 August to 11 September 1960 in Rome, Italy. Rome had previously been awar ...

to be held in Rome.

In the early 1960s, Andreotti was Minister of Defence

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is the part of a government responsible for matters of defence and military forces, found in states where the government is divid ...

, and was widely considered the ''de facto'' leader of the right-wing Christian Democratic opposition to Fanfani and Moro's strategy. In this period, the revelation that the Secret Service had compiled dossiers on virtually every public figure in the country resulted in the SIFAR

(; , ) was the military intelligence agency of Italy from 1977 to 2007.

With the reform of the Italian Intelligence Services approved on 1 August 2007, SISMI was replaced by Agenzia Informazioni e Sicurezza Esterna (AISE).Legislative Act n.12 ...

affair. Andreotti ordered the destruction of the dossiers; but before the destruction, Andreotti provided the documents to Licio Gelli, the Venerable Master of the clandestine lodge Propaganda Due (P2).

Andreotti was also involved in the Piano Solo

The piano is often used to provide harmonic accompaniment to a voice or other instrument. However, solo

Solo or SOLO may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Characters

* Han Solo, a ''Star Wars'' character

* Jacen Solo, a Jedi in the non-canoni ...

scandal, an envisaged plot for an Italian coup in 1964 requested by the then-President of the Italian Republic Antonio Segni. It was prepared by the commander of the Carabinieri, Giovanni de Lorenzo, at the beginning of 1964 in close collaboration with the Italian secret service (SIFAR), CIA secret warfare expert Vernon Walters, William Harvey

William Harvey (1 April 1578 – 3 June 1657) was an English physician who made influential contributions to anatomy and physiology. He was the first known physician to describe completely, and in detail, pulmonary and systemic circulation ...

, then-chief of the CIA station in Rome, and Renzo Rocca, director of the Gladio

Operation Gladio was the codename for clandestine "stay-behind" operations of armed resistance that were organized by the Western Union (WU; founded in 1948), and subsequently by NATO (formed in 1949) and by the CIA (established in 1947), in c ...

units within the military secret service SID.

In 1968, Andreotti was appointed leader of the parliamentary group of Christian Democracy, a position he held until 1972.

First term as prime minister

In 1972, with Andreotti's first term as prime minister began a period when he was often seen as the '' éminence grise'' of governments even when not premier. He remained in office in two consecutive centre-right cabinets in 1972 and 1973. His first cabinet failed in obtaining theconfidence vote

A motion or vote of no confidence (or the inverse, a motion or vote of confidence) is a motion and corresponding vote thereon in a deliberative assembly (usually a legislative body) as to whether an officer (typically an executive) is deemed fit ...

and he was forced to resign after only 9 days; this government has been the one with the shortest period of fullness of powers in the history of the Italian Republic.

A snap election

A snap election is an election that is called earlier than the one that has been scheduled. Snap elections in parliamentary systems are often called to resolve a political impasse such as a hung parliament where no single political party has a ma ...

was called for May 1972, and Christian Democracy, led by Andreotti's ally Arnaldo Forlani, remained stable with around 38% of the votes, as did the Communist Party, with the same 27% as in 1968

Events January–February

* January 1968, January – The I'm Backing Britain, I'm Backing Britain campaign starts spontaneously.

* January 5 – Prague Spring: Alexander Dubček is chosen as leader of the Communist Party of Cze ...

. Andreotti, supported by secretary Forlani, tried to continue his centrist

Centrism is the range of political ideologies that exist between left-wing politics and right-wing politics on the left–right political spectrum. It is associated with moderate politics, including people who strongly support moderate policie ...

strategy, but his attempt only lasted a year. The cabinet fell due to the withdrawal of the external support of the Italian Republican Party

The Italian Republican Party (, PRI) is a political party in Italy established in 1895, which makes it the oldest political party still active in the country. The PRI identifies with 19th-century classical radicalism, as well as Mazzinianism, a ...

on the matter of local television reform.

Social policies

Andeotti's approach owed little to a belief that market mechanisms could be left to work without interference. He usedprice controls

Price controls are restrictions set in place and enforced by governments, on the prices that can be charged for goods and services in a market. The intent behind implementing such controls can stem from the desire to maintain affordability of go ...

on essential foodstuffs and various social reforms to reach an understanding of organised labour. A law of 11 August 1972 extended health insurance to citizens over 65 to receive a social pension. A law of 30 June 1973 extended the cost of living indexation to the social pension.

A devout Catholic, Andreotti was on close terms with six successive pontiffs. He occasionally gave the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Geography

* Vatican City, an independent city-state surrounded by Rome, Italy

* Vatican Hill, in Rome, namesake of Vatican City

* Ager Vaticanus, an alluvial plain in Rome

* Vatican, an unincorporated community in the ...

unsolicited advice which was often heeded. He updated the relationship of Roman Catholicism to the Italian state in an accord he presented to parliament. It put the country on a more secular basis: abolishing Roman Catholicism as the state religion, making religious instruction in public schools optional, and having the Church accept Italy's divorce law in 1971. Andreotti opposed legal divorce and abortion, but despite his party's opposition, he couldn't avoid the legalization of abortion in May 1978.

Foreign policy

Andreotti was a strongNATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

supporter and was invited to America by the U.S. President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

in 1973. A year earlier, he paid an official visit to the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, the first one by an Italian Prime Minister in over a decade. During his premiership, Italy opened and developed diplomatic and economic relationships with Arab countries of the Mediterranean Basin, and supported business and trade between Italy and the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

.

Second term as prime minister

After his resignation, Andreotti served asMinister of Defence

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is the part of a government responsible for matters of defence and military forces, found in states where the government is divid ...

in the government of Mariano Rumor

Mariano Rumor ( ;16 June 1915 – 22 January 1990) was an Italian politician and statesman. A member of the Christian Democracy (Italy), Christian Democracy (DC), he served as the 39th prime minister of Italy from December 1968 to August 1970 an ...

and as Minister of Budget in the cabinets of Aldo Moro. In 1976, the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Social democracy, social democratic and Democratic socialism, democratic socialist political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parti ...

left the centre-left government of Moro. The ensuing general elections

A general election is an electoral process to choose most or all members of a governing body at the same time. They are distinct from by-elections, which fill individual seats that have become vacant between general elections. General elections ...

saw the growth of the Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party (, PCI) was a communist and democratic socialist political party in Italy. It was established in Livorno as the Communist Party of Italy (, PCd'I) on 21 January 1921, when it seceded from the Italian Socialist Part ...

(PCI), and the DC kept only a minimal advantage as the relative majority party in Italy, which was then suffering from an economic crisis and terrorism. After the success of his party, the Communist secretary Enrico Berlinguer

Enrico Berlinguer (; 25 May 1922 – 11 June 1984) was an Italian politician and statesman. Considered the most popular leader of the Italian Communist Party (PCI), he led the PCI as the national secretary from 1972 until his death during a te ...

approached DC's left-leaning leaders, Moro and Fanfani, with a proposal to bring forward the so-called Historic Compromise, a political pact proposed by Moro which would see a government coalition between DC and PCI for the first time. Andreotti, known as a staunch anti-communist, was called in to lead the first experiment in that direction: his new cabinet, formed in July 1976, included only members of his own Christian Democratic party but had the indirect support of the communists.

Andreotti's third cabinet was called "the government of the "not- no confidence", because it was externally supported by all the political parties in the Parliament, except for the neo-fascist

Andreotti's third cabinet was called "the government of the "not- no confidence", because it was externally supported by all the political parties in the Parliament, except for the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement

The Italian Social Movement (, MSI) was a neo-fascist political party in Italy. A far-right party, it presented itself until the 1990s as the defender of Italian fascism's legacy, and later moved towards national conservatism. In 1972, the Itali ...

.

Legislative action

On 28 January 1977, theItalian Parliament

The Italian Parliament () is the national parliament of the Italy, Italian Republic. It is the representative body of Italian citizens and is the successor to the Parliament of the Kingdom of Sardinia (1848–1861), the Parliament of the Kingd ...

approved the Land Use Law, which introduced severe constraints on construction, such as new criteria for land expropriations and new planning procedures. On 27 July 1978, the Fair Rent Law completed state control of rents with general rules for rent levels and terms of leases. A law of 16 February 1977 introduced ad hoc upgrading of cash benefits for the agricultural sector. In November 1977, pension linkage to the industrial wage was extended to all other pension schemes not administered by INPS. A law of 16 February 1977 extended family allowances to part-time agricultural workers. A law of 5 August 1978 introduced a ten-year housing plan, with the state making funds available to regions for public housing and subsidies for private housing. As premier, Andeotti's urging of fellow leaders in the European Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organisation created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisbo ...

was influential in the creation of an EU Regional Development Fund, which the south of Italy was to greatly benefit from.

In 1977, Andreotti dealt with an economic crisis by criticising the luxury lifestyle of many Italians and pushing through tough austerity measures. This cabinet fell in January 1978. In March, the crisis was overcome by the intervention of Moro, who proposed a new cabinet, again formed only by DC politicians, but this time with positive confidence votes from the other parties, including the PCI. This cabinet was also chaired by Andreotti and was formed on 16 March 1978.

Kidnapping of Aldo Moro

On the morning of 16 March 1978, the day on which the new Andreotti cabinet was supposed to have undergone a

On the morning of 16 March 1978, the day on which the new Andreotti cabinet was supposed to have undergone a confidence

Confidence is the feeling of belief or trust that a person or thing is reliable.

*

*

* Self-confidence is trust in oneself. Self-confidence involves a positive belief that one can generally accomplish what one wishes to do in the future. Sel ...

vote in Parliament, the car of Aldo Moro, then-president of Christian Democracy, was assaulted by a group of Red Brigades

The Red Brigades ( , often abbreviated BR) were an Italian far-left Marxist–Leninist militant group. It was responsible for numerous violent incidents during Italy's Years of Lead, including the kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro in 1978, ...

(Italian: ''Brigate Rosse'', or BR) terrorists in Via Fani in Rome. Firing automatic weapons, the terrorists killed Moro's bodyguards (two Carabinieri

The Carabinieri (, also , ; formally ''Arma dei Carabinieri'', "Arm of Carabineers"; previously ''Corpo dei Carabinieri Reali'', "Royal Carabineers Corps") are the national gendarmerie of Italy who primarily carry out domestic and foreign poli ...

in Moro's car and three policemen in the following car) and kidnapped him.

During the kidnapping of Moro, Andreotti refused any negotiation with the terrorists. Moro, during his imprisonment, wrote a statement expressing very harsh judgements against Andreotti.

On 9 May 1978, Moro's body was found in the trunk of a Renault 4 in Via Caetani after 55 days of imprisonment, during which he was submitted to a political trial by the so-called "people's court" set up by the Brigate Rosse and the Italian government was asked for an exchange of prisoners. After Moro's death, Andreotti continued as Prime Minister of the "National Solidarity" government with the support of the PCI. Laws approved during his tenure included the Italian National Health Service reform. However, when the PCI asked to participate more directly in the government, Andreotti refused, and the government was dissolved in June 1979. Due also to conflict with Bettino Craxi

Benedetto "Bettino" Craxi ( ; ; ; 24 February 1934 – 19 January 2000) was an Italian politician and statesman, leader of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) from 1976 to 1993, and the 45th Prime Minister of Italy, prime minister of Italy from 1 ...

, secretary of the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Social democracy, social democratic and Democratic socialism, democratic socialist political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parti ...

(PSI), the other main party in Italy at the time, Andreotti did not hold any further government position until 1983.

Foreign Affairs Minister

In 1983, Andreotti becameMinister of Foreign Affairs

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and foreign relations, relations, diplomacy, bilateralism, ...

in the first Cabinet of Bettino Craxi, despite the long-lasting personal antagonism between the two men which had occurred earlier on; Craxi was the first Socialist to become Prime Minister of Italy since Unification.

Sigonella Crisis

On 7 October 1985, four men representing the Palestine Liberation Front (PLF) hijacked the Italian MS ''Achille Lauro'' liner off the coast of

On 7 October 1985, four men representing the Palestine Liberation Front (PLF) hijacked the Italian MS ''Achille Lauro'' liner off the coast of Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, as she was sailing from Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

to Ashdod

Ashdod (, ; , , or ; Philistine language, Philistine: , romanized: *''ʾašdūd'') is the List of Israeli cities, sixth-largest city in Israel. Located in the country's Southern District (Israel), Southern District, it lies on the Mediterranean ...

, Israel. The hijacking was organized by Muhammad Zaidan, leader of the PLF. One 69-year-old Jewish American man in a wheelchair, Leon Klinghoffer, was murdered by the hijackers and thrown overboard.

The Egyptian airliner carrying the hijackers was intercepted by F-14 Tomcat

The Grumman F-14 Tomcat is an American carrier-capable supersonic, twin-engine, tandem two-seat, twin-tail, all-weather-capable variable-sweep wing fighter aircraft. The Tomcat was developed for the United States Navy's Naval Fighter Experi ...

s from the VF-74 "BeDevilers" and the VF-103 "Sluggers" of Carrier Air Wing 17, based on the aircraft carrier , and directed to land at Naval Air Station Sigonella (a NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

air base in Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

) under the orders of U.S. Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger; there, the hijackers were arrested by the Italian Carabinieri

The Carabinieri (, also , ; formally ''Arma dei Carabinieri'', "Arm of Carabineers"; previously ''Corpo dei Carabinieri Reali'', "Royal Carabineers Corps") are the national gendarmerie of Italy who primarily carry out domestic and foreign poli ...

after a disagreement between American and Italian authorities. Prime Minister Bettino Craxi claimed Italian territorial rights over the NATO base. Italian Air Force

The Italian Air Force (; AM, ) is the air force of the Italy, Italian Republic. The Italian Air Force was founded as an independent service arm on 28 March 1923 by Victor Emmanuel III of Italy, King Victor Emmanuel III as the ("Royal Air Force ...

personnel and Carabinieri lined up facing the United States Navy SEALs

The United States Navy Sea, Air, and Land (SEAL) Teams, commonly known as Navy SEALs, are the United States Navy's primary special operations force and a component of the United States Naval Special Warfare Command. Among the SEALs' main func ...

which had arrived with two C-141s. Other Carabinieri were sent from Catania

Catania (, , , Sicilian and ) is the second-largest municipality on Sicily, after Palermo, both by area and by population. Despite being the second city of the island, Catania is the center of the most densely populated Sicilian conurbation, wh ...

to reinforce the Italians. The US eventually allowed the hijackers to be taken into Italian custody, after receiving assurances that the hijackers would be tried for murder. The other passengers on the plane (including Zaidan) were allowed to continue on to their destination, despite protests by the United States. Egypt demanded an apology from the U.S. for forcing the airplane off course.

The escape of Muhammad Zaidan was the result of a deal made with Yassar Arafat.

Policies

As Minister Andreotti encouraged diplomacy between the United States and theSoviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and improving Italian links with Arab countries. In this respect he followed a line similar to that of Craxi, with whom he had an otherwise troubled political relationship. The Italian authorities had banned the ''Lion of the Desert

''Lion of the Desert'' (alternative titles: ''Omar Mukhtar'' and ''Omar Mukhtar: Lion of the Desert'') is a 1981 epic film, epic historical film, historical war film about the Second Italo-Senussi War, starring Anthony Quinn as Libyan tribal leade ...

'' war film about the Second Italo-Senussi War

The Second Italo-Senussi War, also referred to as the pacification of Libya, was a conflict that occurred during the Italian colonization of Libya between Italian military forces (composed mainly by colonial troops from Libya, Eritrea, and Som ...

during the Italian colonization of Libya

The Italian colonization of Libya began in 1911 and it lasted until 1943. The country, which was previously an Ottoman Tripolitania, Ottoman possession, was occupied by Kingdom of Italy, Italy in 1911 after the Italo-Turkish War, which resulted i ...

, because, in the words of Andreotti, it was "damaging to the honor of the army".

On 14 April 1986, Andreotti revealed to Libyan Foreign Minister Abdel Rahman Shalgham

Abdel Rahman Shalgam (Arabic: عبد الرحمن شلقم; born 22 January 1949) is a Libyan politician. He was Foreign Minister of Libya from 2000 to 2009.

Early life

Shalgam was born in Sabha in southern Libya.

Career in politics

In 1973, he ...

that the United States would bomb Libya the next day in retaliation for the Berlin disco terrorist attack which had been linked to Libya. As a result of the warning from Italy – a supposed ally of the US – Libya was better prepared for the bombing. Nevertheless, on the following day, Libya fired two Scud

A Scud missile is one of a series of tactical ballistic missiles developed by the Soviet Union during the Cold War. It was exported widely to both Second and Third World countries. The term comes from the NATO reporting name attached to the m ...

s at the Italian island of Lampedusa in retaliation. However, the missiles passed over the island, landed in the sea and caused no damage. As Craxi's relationship with the then-National Secretary of the DC, Ciriaco De Mita

Luigi Ciriaco De Mita (; 2 February 1928 – 26 May 2022) was an Italian politician and statesman who served as Prime Minister of Italy from April 1988 to July 1989.

A member of the Christian Democracy (Italy), Christian Democracy (DC), De Mita ...

, was even worse, Andreotti was instrumental in the creation of the so-called "CAF triangle" (from the initials of the surnames of Craxi, Andreotti and another DC leader, Arnaldo Forlani) opposing De Mita's power.

After Craxi's resignation in 1987, Andreotti remained Minister of Foreign Affairs in the governments of Fanfani and De Mita. In 1989, when De Mita's government fell, Andreotti was appointed as the new prime minister.

Third term as prime minister

On 22 July 1989, Andreotti was sworn in for the third time as prime minister. A turbulent course characterized his government; he decided to stay at the head of government, despite the abandonment of manysocial democratic

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

ministers, after the approval of the norm on TV spots favourable to private TV channels of Silvio Berlusconi

Silvio Berlusconi ( ; ; 29 September 193612 June 2023) was an Italian Media proprietor, media tycoon and politician who served as the prime minister of Italy in three governments from 1994 to 1995, 2001 to 2006 and 2008 to 2011. He was a mem ...

. This choice did not prevent the resurgence of old suspicions and resentments with Bettino Craxi

Benedetto "Bettino" Craxi ( ; ; ; 24 February 1934 – 19 January 2000) was an Italian politician and statesman, leader of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) from 1976 to 1993, and the 45th Prime Minister of Italy, prime minister of Italy from 1 ...

, whose Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Social democracy, social democratic and Democratic socialism, democratic socialist political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parti ...

withdrew from their coalition government in 1991. Andreotti would create a new government consisting of Christian Democrats, Socialists, Social Democrats, and Liberals.

In 1990, Andreotti revealed the existence of the Operation Gladio

Operation Gladio was the codename for clandestine " stay-behind" operations of armed resistance that were organized by the Western Union (WU; founded in 1948), and subsequently by NATO (formed in 1949) and by the CIA (established in 1947), in ...

; Gladio was the codename for a clandestine North Atlantic Treaty Organization

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental transnational military alliance of 32 member states—30 European and 2 North American. Established in the aftermat ...

(NATO) "stay-behind" operation in Italy during the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

. Its purpose was to prepare for and implement armed resistance in the event of a Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP), formally the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance (TFCMA), was a Collective security#Collective defense, collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Polish People's Republic, Poland, between the Sovi ...

invasion and conquest. Although Gladio specifically refers to the Italian branch of the NATO stay-behind

A stay-behind operation is one where a country places secret operatives or organizations in its own territory, for use in case of a later enemy occupation. The stay-behind operatives would then form the basis of a resistance movement, and act as ...

organizations, "Operation Gladio" is used as an informal name for all of them.

During his premiership, Andreotti clashed many times with the President of the Republic Francesco Cossiga.

European Union negotiations

In 1990, Andreotti was involved in getting all parties to agree to a binding timetable for theMaastricht Treaty

The Treaty on European Union, commonly known as the Maastricht Treaty, is the foundation treaty of the European Union (EU). Concluded in 1992 between the then-twelve Member state of the European Union, member states of the European Communities, ...

. The deep Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union

The economic and monetary union (EMU) of the European Union is a group of policies aimed at converging the economies of member states of the European Union at three stages.

There are three stages of the EMU, each of which consists of progressi ...

favoured by Italy was opposed by Britain's Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013), was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of th ...

, who wanted a system of competition between currencies. Germany had doubts about committing to the project without requiring economic reforms from Italy, which was seen as having various imbalances. As President of the European Council, Andreotti co-opted Germany by making admittance to the single market automatic once the criteria had been met and committing to a rigorous overhaul of Italian public finances. Critics later questioned Andreotti's understanding of the obligation or whether he had ever intended to fulfil it.

Resignation and decline

In 1992, at the end of the legislature, Andreotti resigned from premiership; he was the last Christian Democratic Prime Minister of Italy. The previous year, Cossiga had appointed him Senator for Life. Andreotti was one of the most likely candidates to succeed Cossiga as President of the Republic in the 1992 presidential election. Andreotti and the members of his ''corrente'' had adopted a strategy of launching his candidature only after effectively quenching all the others. Allegations against him thwarted the strategy; moreover, the election was influenced by the murder of theanti-mafia

The Antimafia Commission () is a bicameral commission of the Italian Parliament, composed of members from the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate of the Republic (Italy), Senate of the Republic. The first commission, formed in 1963, was established ...

magistrate Giovanni Falcone

Giovanni Falcone (; 18 May 1939 – 23 May 1992) was an Italian judge and prosecuting magistrate. From his office in the Palace of Justice in Palermo, Sicily, he spent most of his professional life trying to overthrow the power of the Sicilian ...

in Palermo

Palermo ( ; ; , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital (political), capital of both the autonomous area, autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The ...

.

Later political life

Tangentopoli

In 1992, an investigation was started inMilan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

, dubbed ''Mani pulite

(; ) was a nationwide judicial investigation into political corruption in Italy held in the early 1990s, resulting in the demise of the First Italian Republic and the disappearance of many political parties. Some politicians and industry leade ...

''. It uncovered endemic corruption practices at the highest levels, causing many spectacular (and sometimes controversial) arrests and resignations. After the disappointing result in the 1992 general election (29.7%) and two years of mounting scandals (which included several Mafia investigations which notably touched Andreotti), the Christian Democracy party was disbanded in 1994. In the 1990s, most of the politicians prosecuted were acquitted during those investigations, sometimes based on legal formalities or on statutory time limit rules.

After Christian Democracy

Christian Democracy suffered heavy defeats in the provincial and municipal elections, and polling suggested heavy losses in the 1994 Italian general election. In hopes of changing the party's image, the DC's last secretary,Mino Martinazzoli

Fermo "Mino" Martinazzoli (; 3 November 1931 – 4 September 2011) was an Italian lawyer, politician, and former minister. He was the last secretary of the Christian Democracy (Italy), Christian Democracy (DC) party and the first secretary of the ...

, decided to change the name of the party to the Italian People's Party (PPI). Pier Ferdinando Casini

Pier Ferdinando Casini (; born 3 December 1955) is an Italian politician. He served as President of the Chamber of Deputies (Italy), President of the Chamber of Deputies from 2001 to 2006.

Casini is the honorary president of the Centrist Democra ...

, representing the centre-right faction of the party (previously led by Forlani), decided to launch a new party called Christian Democratic Centre and form an alliance with Silvio Berlusconi

Silvio Berlusconi ( ; ; 29 September 193612 June 2023) was an Italian Media proprietor, media tycoon and politician who served as the prime minister of Italy in three governments from 1994 to 1995, 2001 to 2006 and 2008 to 2011. He was a mem ...

's new party, Forza Italia

(FI; ) was a centre-right liberal-conservative political party in Italy, with Christian democratic,Chiara Moroni, , Carocci, Rome 2008 liberalOreste Massari, ''I partiti politici nelle democrazie contempoiranee'', Laterza, Rome-Bari 2004 (esp ...

. The left-wing faction either joined the Democratic Party of the Left

The Democratic Party of the Left (, PDS) was a democratic-socialist and social-democratic political party in Italy. Founded in February 1991 as the post-communist evolution of the Italian Communist Party, the party was the largest in the A ...

or stayed within the new PPI, while some right-wingers joined National Alliance.

Andreotti joined the PPI of Mino Martinazzoli. In 2001, after the creation of The Daisy, Andreotti abandoned the People's Party and joined the European Democracy, a minor

Andreotti joined the PPI of Mino Martinazzoli. In 2001, after the creation of The Daisy, Andreotti abandoned the People's Party and joined the European Democracy, a minor Christian democratic

Christian democracy is an ideology inspired by Christian social teaching to respond to the challenges of contemporary society and politics.

Christian democracy has drawn mainly from Catholic social teaching and neo-scholasticism, as well ...

political party in Italy, led by Sergio D'Antoni, former leader of the Italian Confederation of Workers' Trade Unions. Andreotti immediately became a prominent party member and was widely considered the ''de facto'' leader of the movement.

In the 2001 general election, the party scored 2.3% on a stand-alone list, winning only two seats in the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

. In December 2002 it was merged with the Christian Democratic Centre and the United Christian Democrats to form the Union of Christian and Centre Democrats

The Union of the Centre (, UdC), whose complete name is Union of Christian and Centre Democrats (''Unione dei Democratici Cristiani e Democratici di Centro'', UDC), is a Christian-democratic political party in Italy.

Lorenzo Cesa is the part ...

. Andreotti opposed this union and did not join the new party.

In 2006, Andreotti stood for the Presidency of the Italian Senate, obtaining 156 votes against the 165 of Franco Marini, former Labour Minister in the last Andreotti Cabinet. On 21 January 2008, he abstained from a vote in the Senate concerning Minister Massimo D'Alema

Massimo D'Alema (; born 20 April 1949) is an Italian politician and journalist who was the 53rd prime minister of Italy from 1998 to 2000. He was Deputy Prime Minister of Italy and Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs from 2006 to 2008. D'Alema ...

's report on foreign politics. The abstentions of another life senator, Sergio Pininfarina, and of two Communist senators caused the government to lose the vote. Consequently, Prime Minister Romano Prodi

Romano Prodi (; born 9 August 1939) is an Italian politician who served as President of the European Commission from 1999 to 2004 and twice as Prime Minister of Italy, from 1996 to 1998, and again from 2006 to 2008. Prodi is considered the fo ...

resigned. On previous occasions, Andreotti had always supported Prodi's government with his vote.

During the 16th term of the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

in 2008–2013, he opted to join the parliamentary group Union of the Centre – Independents of Pier Ferdinando Casini

Pier Ferdinando Casini (; born 3 December 1955) is an Italian politician. He served as President of the Chamber of Deputies (Italy), President of the Chamber of Deputies from 2001 to 2006.

Casini is the honorary president of the Centrist Democra ...

.

Controversies

Trial for Mafia association

Andreotti came under suspicion because his relatively small faction within the Christian Democrats included Sicilian Salvatore Lima. In Sicily, Lima cooperated with a

Andreotti came under suspicion because his relatively small faction within the Christian Democrats included Sicilian Salvatore Lima. In Sicily, Lima cooperated with a Palermo

Palermo ( ; ; , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital (political), capital of both the autonomous area, autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The ...

-based Mafia, which operated below the surface of public life by controlling large numbers of votes to enable mutually beneficial relationships with local politicians. Andreotti said, "But Lima never spoke to me about these things."Follain, (2012). By the 1980s, the old low-profile Mafia was overthrown by the Corleonesi, an extremely violent faction led by fugitive Salvatore Riina.Stille, ''Excellent Cadavers'', p. 384 Whereas old Mafia bosses had been cautious about violence, Riina's targeting of anti-mafia officials proved ever more counter-productive. The 1982 murders of parliamentarian Pio La Torre and Carabinieri general Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa led to the Maxi Trial

The Maxi Trial () was a criminal trial against the Sicilian Mafia that took place in Palermo, Sicily. The trial lasted from 10 February 1986 (the first day of the Corte d'Assise) to 30 January 1992 (the final day of the Supreme Court of Cassati ...

. Prosecutors, who could not be disciplined or removed except by their self-government board, the CSM, were given increased powers. After January 1992 upholding of the Maxi Trial verdicts as definitive convictions by the supreme court, Riina embarked on a renewed campaign which claimed the lives of the prosecuting magistrates, Giovanni Falcone

Giovanni Falcone (; 18 May 1939 – 23 May 1992) was an Italian judge and prosecuting magistrate. From his office in the Palace of Justice in Palermo, Sicily, he spent most of his professional life trying to overthrow the power of the Sicilian ...

and Paolo Borsellino

Paolo Emanuele Borsellino (; 19 January 1940 – 19 July 1992) was an Italian judge and prosecuting magistrate. From his office in the Palace of Justice in Palermo, Sicily, he spent most of his professional life trying to overthrow the power of ...

, and their police guards. As Riina intended, the assassination of Falcone discredited Andreotti and prevented him from becoming Italy's president. It also led to prosecutors being seen as epitomising civic virtue. In January 1993, Riina was arrested in Palermo. In the aftermath of Riina's capture, there were further Mafia bomb outrages that included terror attacks on art galleries and churches, which killed ten among the audience and led to a weakening of rules on the evidence which prosecutors could use to bring charges.

Labelled by Italian media as the "trial of the century", legal action against Andreotti began on 27 March 1993 in Palermo. The prosecution accused the former prime minister of " akingavailable to the mafia association named Cosa Nostra for the defence of its interests and attainment of its criminal goals, the influence and power coming from his position as the leader of a political faction". Prosecutors said in return for electoral support of Lima and assassination of Andreotti's enemies, he had agreed to protect the Mafia, which had expected him to fix the Maxi Trial. Andreotti's defence was predicated on character attacks against the prosecution's key witnesses, who were themselves involved with the mafia. This created a "his word against theirs" dynamic between a prominent politician and a handful of criminals. The defence said Andreotti had been a long-time politician of national stature, never beholden to Lima; and that far from providing protection, Andreotti had passed many tough anti-mafia laws when in government during the '80s. According to Andreotti's lawyers, the prosecution case was based on conjecture and inference, without any concrete proof of direct involvement by Andreotti. The defence also contended the prosecution relied on the word of mafia turncoats whose evidence had been contradictory. One such informer testified that Riina and Andreotti had met and exchanged a "kiss of honour".Stille, ''Excellent Cadavers'', p. 392 It emerged that the informer had received a US$300,000 "bonus" and committed a number of murders while in the witness protection programme. Andreotti dismissed the allegation against him as "lies and slander ... the kiss of Riina, mafia summits ... scenes out of a comic horror film".

Andreotti was eventually acquitted on 23 October 1999; however, together with the greater series of corruption cases of Mani pulite

(; ) was a nationwide judicial investigation into political corruption in Italy held in the early 1990s, resulting in the demise of the First Italian Republic and the disappearance of many political parties. Some politicians and industry leade ...

, Andreotti's trials marked the purging and renewal of Italy's political system.

Andreotti's absolution and statute of limitations

Andreotti was tried in Palermo for criminal association until 28 September 1982 and mafia association from 29 September 1982 onwards. While the first-degree sentence, issued on 23 October 1999, acquitted him because the fact did not exist on the basis of article 530, paragraph 2, of the Penal Code, the appeal sentence, issued on 2 May 2003, distinguishing between the facts up to 1980 and those that followed, established that Andreotti "had committed" the "offence of participation in the criminal association" (''Cosa Nostra

The Sicilian Mafia or Cosa Nostra (, ; "our thing"), also referred to as simply Mafia, is a criminal society and criminal organization originating on the island of Sicily and dates back to the mid-19th century. Emerging as a form of local protect ...

''), "concretely recognisable until the spring of 1980", an offence that was "extinguished by statute of limitations

A statute of limitations, known in civil law systems as a prescriptive period, is a law passed by a legislative body to set the maximum time after an event within which legal proceedings may be initiated. ("Time for commencing proceedings") In ...

". For facts subsequent to the spring of 1980, Andreotti was acquitted.

Both the prosecution and the defence appealed to the Court of Cassation

A court of cassation is a high-instance court that exists in some judicial systems. Courts of cassation do not re-examine the facts of a case; they only interpret the relevant law. In this, they are appellate courts of the highest instance. In ...

, one against the acquittal, and the other to try to obtain an acquittal even on the facts until 1980, instead of a statute of limitations. On 15 October 2004, the Court of Cassation rejected both requests, confirming the statute of limitations for any offence until the spring of 1980 and acquittal for the rest. The grounds for the appeal judgment read (on page 211): "Therefore the appealed sentence ... has recognized the participation in the associative crime not in the reductive terms of mere availability, but in the widest and juridically significant ones of a concrete collaboration." It quotes the opinion of the Court of Appeal and is immediately followed by another sentence of the Court of Cassation: "The reconstruction of single episodes and the evaluation of their consequences were made per comments and interpretations that can also be not shared and against which other ones can be relied on." Suppose the final judgment had arrived by 20 December 2002 (limitation period). In that case, it could have resulted in one of the following two alternative outcomes:

* Andreotti could have been convicted based on article 416 of the Penal Code, i.e. the "simple" association, since the aggravated mafia-type association (416-bis of the Penal Code) was introduced in the Italian Penal Code only in 1982, thanks to the rapporteurs Virginio Rognoni

Virginio Rognoni (5 August 1924 – 20 September 2022) was an Italian politician, who was a prominent member of Christian Democracy (Italy), Christian Democracy. He was several times Italian Minister of the Interior, Interior Minister, Italian M ...

(DC) and Pio La Torre. (PCI).

* The defendant could have been acquitted in full with the confirmation of the first instance judgment.

In 2010, the Court of Cassation ruled that Andreotti had slandered a judge who had given testimony by saying the self-governing body of prosecutors and judges should remove him from his position. Andreotti had said that leaving the man as a judge was "like leaving a lighted fuse in the hand of a child".

Trial for murder

Contemporaneously with his trial for Mafia association, Andreotti was tried inPerugia

Perugia ( , ; ; ) is the capital city of Umbria in central Italy, crossed by the River Tiber. The city is located about north of Rome and southeast of Florence. It covers a high hilltop and part of the valleys around the area. It has 162,467 ...

with Sicilian Mafia boss Gaetano Badalamenti

Gaetano Badalamenti (; 14 September 1923 – 29 April 2004) was a powerful member of the Sicilian Mafia. ''Don Tano'' Badalamenti was the capofamiglia of his hometown Cinisi, Sicily, and headed the Sicilian Mafia Commission in the 1970s. In 1 ...

, Massimo Carminati

Massimo Carminati (; born 31 May 1958), referred by the press as one of "the kings of Rome", and in the context of the onset of the "Mafia Capitale" investigation nicknamed as ''il Cecato'' ("The Blinded One"), is an Italian underworld figure and ...

, and others on charges of complicity in the murder of journalist Mino Pecorelli. The case was circumstantial and based on the word of Mafia turncoat Tommaso Buscetta

Tommaso Buscetta (; 13 July 1928 – 2 April 2000) was a high-ranking Italian mobster and a member of the Sicilian Mafia. He became one of the first of its members to turn informant and explain the inner workings of the organization.

Buscetta p ...

, who had not originally mentioned the allegation about Andreotti when interviewed by Giovanni Falcone

Giovanni Falcone (; 18 May 1939 – 23 May 1992) was an Italian judge and prosecuting magistrate. From his office in the Palace of Justice in Palermo, Sicily, he spent most of his professional life trying to overthrow the power of the Sicilian ...

and had recanted it by the time of the trial.

Mino Pecorelli was killed in Rome's Prati district with four gunshots, on 20 March 1979. The bullets used to kill him were ''Gevelot'' brand, a peculiarly rare type of bullet not easily found on gun markets, legal and clandestine alike. The same kind of bullet was later found in the '' Banda della Magliana''s weapon stock, concealed in the Health Ministry's basement. Investigations targeted Massimo Carminati

Massimo Carminati (; born 31 May 1958), referred by the press as one of "the kings of Rome", and in the context of the onset of the "Mafia Capitale" investigation nicknamed as ''il Cecato'' ("The Blinded One"), is an Italian underworld figure and ...

, member of the far-right organization ''Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari

The Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari (), abbreviated NAR, was an Italian neofascist, neo-fascist armed militant organization active during the Years of Lead (Italy), Years of Lead from 1977 to November 1981. It committed over 100 murders in four year ...

'' (NAR) and of the ''Banda della Magliana'', the head of Propaganda Due, Licio Gelli, Antonio Viezzer, Cristiano Fioravanti and Valerio Fioravanti

Giuseppe Valerio Fioravanti (born 28 March 1958) is an Italian former terrorist and actor, who was a leading figure in the Far-right politics, far-right ''Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari'' (Armed Revolutionary Nuclei, or NAR). Fioravanti appeared in ...

.

On 6 April 1993, Mafia turncoat Tommaso Buscetta told Palermo prosecutors that he had learnt from his boss Gaetano Badalamenti

Gaetano Badalamenti (; 14 September 1923 – 29 April 2004) was a powerful member of the Sicilian Mafia. ''Don Tano'' Badalamenti was the capofamiglia of his hometown Cinisi, Sicily, and headed the Sicilian Mafia Commission in the 1970s. In 1 ...

that Pecorelli's murder had been carried out in the interest of Andreotti. The Salvo cousins, two powerful Sicilian politicians with deep ties to local Mafia families, were also involved in the murder. Buscetta testified that Gaetano Badalamenti told him that the Salvo cousins had commissioned the murder as a favour to Andreotti. Andreotti was allegedly afraid that Pecorelli was about to publish information that could have destroyed his political career. Among the information was the complete memorial of Aldo Moro

Aldo Moro (; 23 September 1916 – 9 May 1978) was an Italian statesman and prominent member of Christian Democracy (Italy), Christian Democracy (DC) and its centre-left wing. He served as prime minister of Italy in five terms from December 1963 ...

, which would be published only in 1990 and which Pecorelli had shown to General Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa before his death. Dalla Chiesa was also assassinated by Mafia in September 1982.

Andreotti was acquitted along with his co-defendants in 1999. Local prosecutors successfully appealed the acquittal, and there was a retrial, which in 2002 convicted Andreotti and sentenced him to 24 years imprisonment. Italians of all political allegiances denounced the conviction. Many failed to understand how the court could convict Andreotti of orchestrating the killing, yet acquit his co-accused, who supposedly had carried out his orders by setting up and committing the murder. The Italian supreme court definitively acquitted Andreotti of the murder in 2003.

Personal life

On 16 April 1945, Andreotti married Livia Danese (1 June 1921 – 29 July 2015) and had two sons and two daughters, Lamberto (born 6 July 1950), Marilena, Stefano and Serena.Death and legacy

Andreotti said the opinion of others was of little consequence to him, and "In any case, a few years from now, no one will remember me." He died inRome