Girolamo Savonarola on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Girolamo Savonarola, OP (, ; ; 21 September 1452 – 23 May 1498), also referred to as Jerome Savonarola, was an ascetic Dominican

Savonarola was born on 21 September 1452 in

Savonarola was born on 21 September 1452 in

The writings of Savonarola spread widely to

The writings of Savonarola spread widely to

Savonarolan religious ideas found a reception elsewhere. In Germany and Switzerland the early Protestant reformers, most notably Martin Luther himself, read some of the friar's writings and praised him as a martyr and forerunner whose ideas on faith and grace anticipated Luther's own doctrine of justification by faith alone. In France many of his works were translated and published and Savonarola came to be regarded as a precursor of evangelical, or

Savonarolan religious ideas found a reception elsewhere. In Germany and Switzerland the early Protestant reformers, most notably Martin Luther himself, read some of the friar's writings and praised him as a martyr and forerunner whose ideas on faith and grace anticipated Luther's own doctrine of justification by faith alone. In France many of his works were translated and published and Savonarola came to be regarded as a precursor of evangelical, or

Catholic Encyclopedia entry on Girolamo Savonarola

''Predica dell'arte del bene morire''

From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the

''Savonarola's Visions'', documentary about Girolamo Savonarola

{{DEFAULTSORT:Savonarola, Girolamo Executed Roman Catholic priests Italian Roman Catholics Italian torture victims Italian Dominicans People excommunicated by the Catholic Church People executed by the Papal States by burning People executed for heresy Religious leaders from Ferrara Heads of state of Florence University of Ferrara alumni 1452 births 1498 deaths 15th-century Italian Roman Catholic priests Proto-Protestants Dominican Order in Florence Friars of San Marco, Florence People of the Italian War of 1494–1495

friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders in the Catholic Church. There are also friars outside of the Catholic Church, such as within the Anglican Communion. The term, first used in the 12th or 13th century, distinguishes the mendi ...

from Ferrara

Ferrara (; ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Emilia-Romagna, Northern Italy, capital of the province of Ferrara. it had 132,009 inhabitants. It is situated northeast of Bologna, on the Po di Volano, a branch channel of the main ...

and a preacher active in Renaissance Florence. He became known for his prophecies of civic glory, his advocacy of the destruction of secular art and culture, and his calls for Christian renewal. He denounced clerical corruption, despotic rule, and the exploitation of the poor.

In September 1494, when King Charles VIII of France invaded Italy and threatened Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

, Savonarola's prophecies seemed on the verge of fulfillment. While the friar intervened with the French king, the Florentines expelled the ruling Medicis and at Savonarola's urging established a "well received" republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

, effectively under Savonarola's control. Declaring that Florence would be the New Jerusalem

In the Book of Ezekiel in the Hebrew Bible, New Jerusalem (, ''YHWH šāmmā'', YHWH sthere") is Ezekiel's prophetic vision of a city centered on the rebuilt Holy Temple, to be established in Jerusalem, which would be the capital of the ...

, the world centre of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

and "richer, more powerful, more glorious than ever", he instituted an extreme moralistic campaign, enlisting the active help of Florentine youth.

In 1495, when Florence refused to join Pope Alexander VI

Pope Alexander VI (, , ; born Roderic Llançol i de Borja; epithet: ''Valentinus'' ("The Valencian"); – 18 August 1503) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 11 August 1492 until his death in 1503.

Born into t ...

's Holy League against the French, the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Geography

* Vatican City, an independent city-state surrounded by Rome, Italy

* Vatican Hill, in Rome, namesake of Vatican City

* Ager Vaticanus, an alluvial plain in Rome

* Vatican, an unincorporated community in the ...

summoned Savonarola to Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

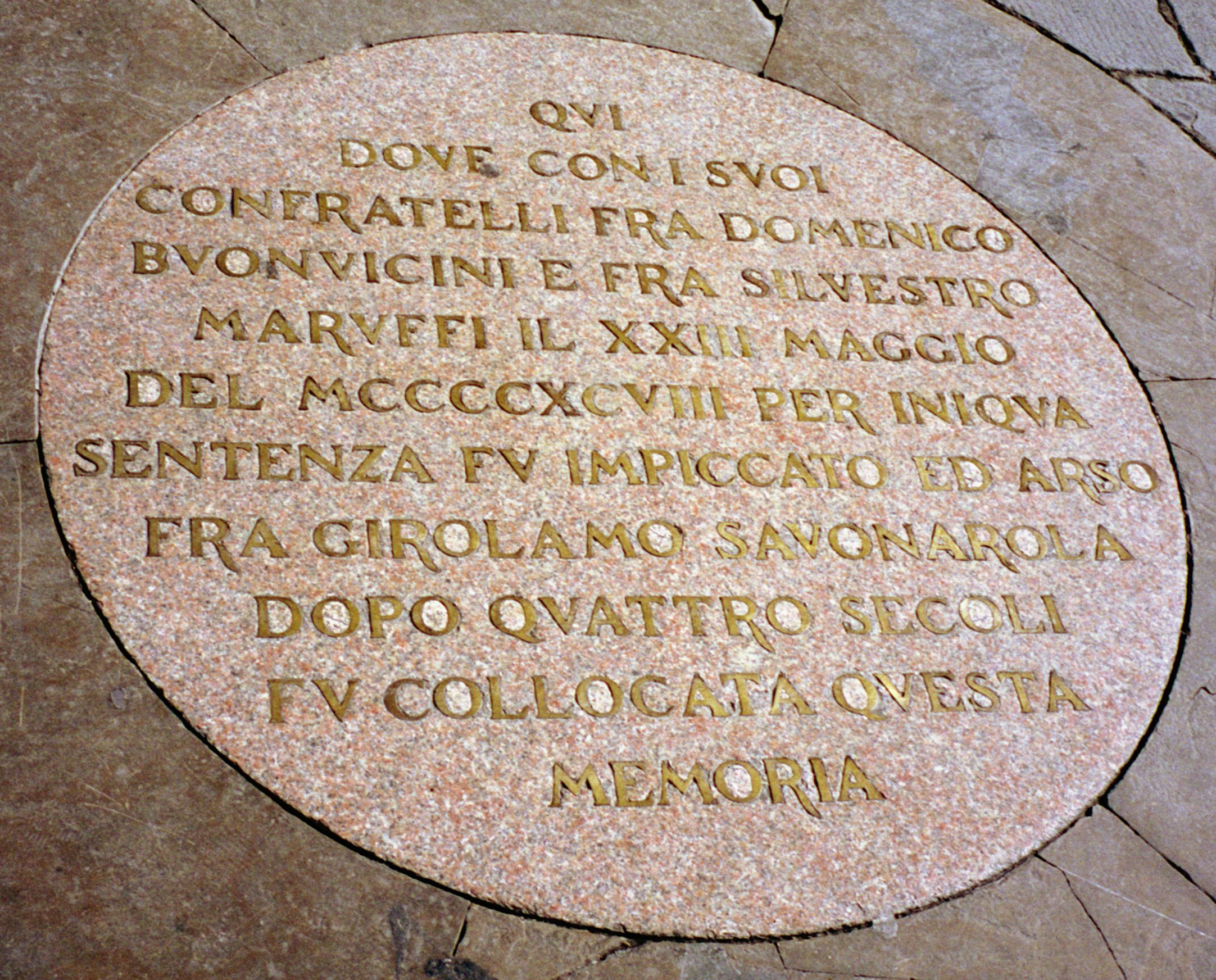

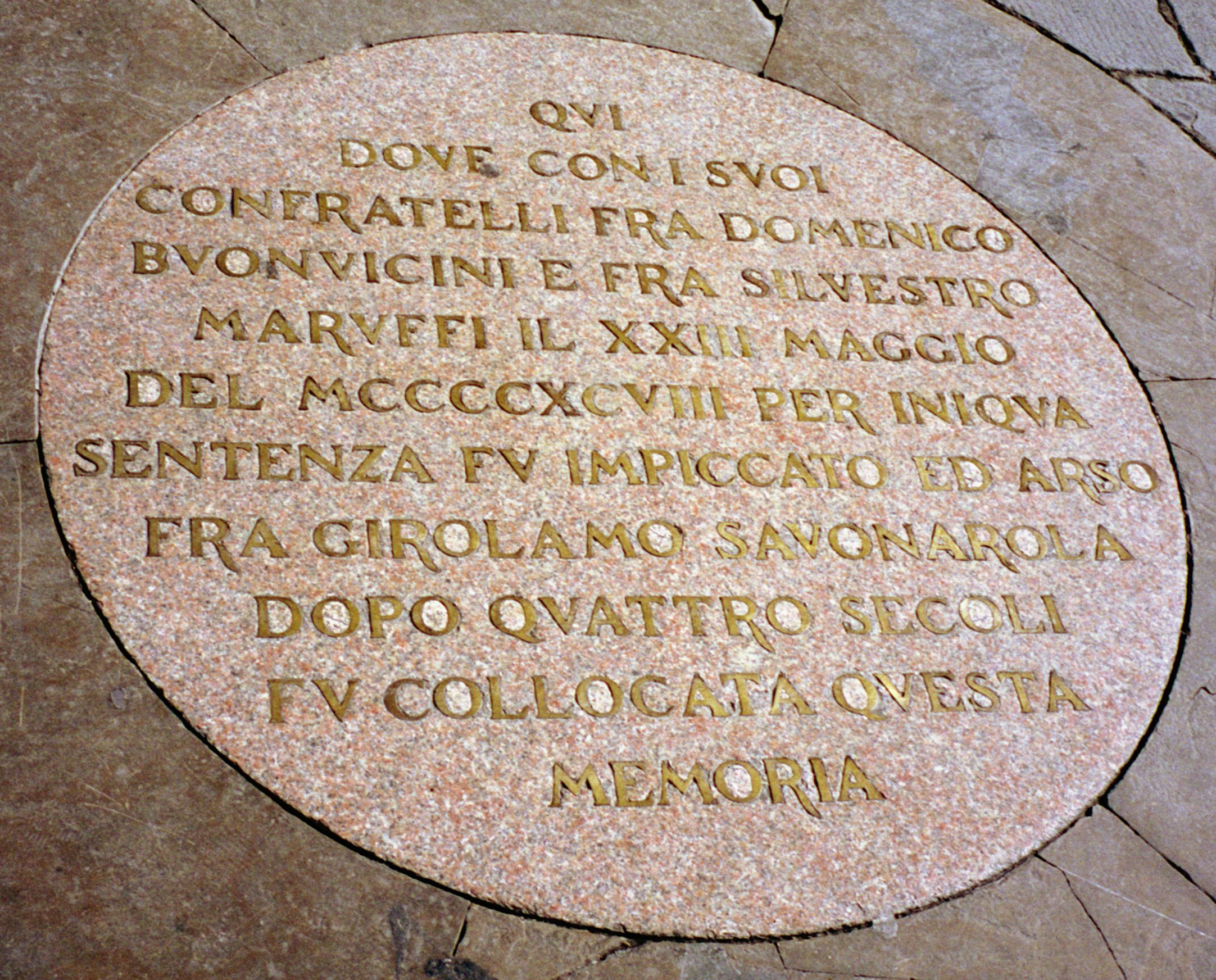

. He disobeyed, and further defied the pope by preaching under a ban, highlighting his campaign for reform with processions, bonfires of the vanities, and pious theatricals. In retaliation, Pope Alexander excommunicated Savonarola in May 1497 and threatened to place Florence under an interdict. A trial by fire proposed by a rival Florentine preacher in April 1498 to test Savonarola's divine mandate turned into a fiasco, and popular opinion turned against him. Savonarola and two of his supporting friars were imprisoned. On 23 May 1498, Church and civil authorities condemned, hanged, and burned the bodies of the three friars in the main square of Florence.

Savonarola's devotees, the , kept his cause of republican freedom and religious reform alive well into the following century. Pope Julius II

Pope Julius II (; ; born Giuliano della Rovere; 5 December 144321 February 1513) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1503 to his death, in February 1513. Nicknamed the Warrior Pope, the Battle Pope or the Fearsome ...

(in office: 1503–1513) allegedly considered his canonization

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christianity, Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon ca ...

. The Medici—restored to power in Florence in 1512 with the help of the papacy—eventually weakened the movement. Some early Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

, including Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

himself, have regarded Savonarola as a vital precursor to the Protestant Reformation.

Early years

Savonarola was born on 21 September 1452 in

Savonarola was born on 21 September 1452 in Ferrara

Ferrara (; ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Emilia-Romagna, Northern Italy, capital of the province of Ferrara. it had 132,009 inhabitants. It is situated northeast of Bologna, on the Po di Volano, a branch channel of the main ...

to Niccolò di Michele and Elena. His father, Niccolò, was born in Ferrara to a family originally from Padua

Padua ( ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Veneto, northern Italy, and the capital of the province of Padua. The city lies on the banks of the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice and southeast of Vicenza, and has a population of 20 ...

; his mother, Elena, claimed a lineage from the Bonacossi family of Mantua

Mantua ( ; ; Lombard language, Lombard and ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Italian region of Lombardy, and capital of the Province of Mantua, eponymous province.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the "Italian Capital of Culture". In 2 ...

. She and Niccolò had seven children, of whom Girolamo was third. His grandfather, Michele Savonarola, a noted and successful physician and polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

, oversaw Girolamo's education. The family amassed a great deal of wealth from Michele's medical practice. After his grandfather's death in 1468 Savonarola may have attended the public school run by Battista Guarino, son of Guarino da Verona

Guarino Veronese or Guarino da Verona (1374 – 14 December 1460) was an Italian classical scholar, humanist, and translator of ancient Greek texts during the Renaissance. In the republics of Florence and Venice he studied under Manuel Chryso ...

, where he would have received his introduction to the classics as well as to the poetry and writings of Petrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

, father of Renaissance humanism. Earning an arts degree at the University of Ferrara, he prepared to enter medical school, following in his grandfather's footsteps. At some point, however, he abandoned his career intentions.

In his early poems he expresses his preoccupation with the state of the Church and of the world. He began to write poetry of an apocalyptic bent, notably "On the Ruin of the World" (1472) and "On the Ruin of the Church" (1475), in which he singled out the papal court at Rome for special obloquy. About the same time he seems to have been thinking about a life in religion. As he later told his biographer, a sermon he heard by a preacher in Faenza persuaded him to abandon the world. Most of his biographers reject or ignore the account of his younger brother and follower, Maurelio (later fra Mauro), that in his youth Girolamo had been spurned by a neighbour, Laudomia Strozzi, to whom he had proposed marriage. True or not, in a letter he wrote to his father when he left home to join the Dominican Order

The Order of Preachers (, abbreviated OP), commonly known as the Dominican Order, is a Catholic Church, Catholic mendicant order of pontifical right that was founded in France by a Castilians, Castilian priest named Saint Dominic, Dominic de Gu ...

he hints at being troubled by desires of the flesh. There is also a story that on the eve of his departure he dreamed that he was cleansed of such thoughts by a shower of icy water, which prepared him for the ascetic life. In the unfinished treatise he left behind, later called "De contemptu Mundi" or "On Contempt for the World", he calls upon readers to fly from this world of adultery, sodomy, murder, and envy.

Savonarola studied Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

and Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

. He also studied the scriptures and memorised parts. On 25 April 1475, Savonarola went to Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

, where he knocked on the door of the Friary of San Domenico, of the Order of Friars Preacher, and asked to be admitted. As he told his father in his farewell letter, he wanted to become a knight of Christ.

Friar

In the convent, Savonarola took the vow of obedience proper to his order, and after a year was ordained to the priesthood. He studied Scripture, logic, Aristotelian philosophy and Thomistic theology in the Dominican studium, practised preaching to his fellow friars, and engaged in disputations. He then matriculated in the theological faculty to prepare for an advanced degree. Even as he continued to write devotional works and to deepen his spiritual life, he was openly critical of what he perceived as the decline in convent austerity. In 1478 his studies were interrupted when he was sent to the Dominican priory of Santa Maria degli Angeli inFerrara

Ferrara (; ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Emilia-Romagna, Northern Italy, capital of the province of Ferrara. it had 132,009 inhabitants. It is situated northeast of Bologna, on the Po di Volano, a branch channel of the main ...

as assistant master of novices. The assignment might have been a normal, temporary break from the academic routine, but in Savonarola's case, it was a turning point. One explanation is that he had alienated certain of his superiors, particularly fra Vincenzo Bandelli, or Bandello, a professor at the studium and future master general of the Dominicans, who resented the young friar's opposition to modifying the Order's rules against the ownership of property.

In 1482, instead of returning to Bologna to resume his studies, Savonarola was assigned as lector, or teacher, in the Convent of San Marco in Florence. In San Marco, fra Girolamo (Savonarola) taught logic to the novices, wrote instructional manuals on ethics, logic, philosophy and government, composed devotional works, and prepared his sermons for local congregations. As he recorded in his notes, his preaching was not altogether successful. Florentines were put off by his foreign-sounding Ferrarese speech, his strident voice and (especially to those who valued humanist rhetoric) his inelegant style.

While waiting for a friend in the Convent of San Giorgio, he was studying Scripture when he suddenly conceived "about seven reasons" why the Church was about to be scourged and renewed. He broached these apocalyptic themes in San Gimignano, where he went as Lenten preacher in 1485 and again in 1486. A year later, when he left San Marco for a new assignment, he had said nothing of his "San Giorgio revelations" in Florence.

Preacher

For the next several years, Savonarola lived as an itinerant preacher with a message of repentance and reform in the cities and convents of north Italy. As his letters to his mother and his writings show, his confidence and sense of mission grew along with his widening reputation. In 1490, he was reassigned to San Marco. It seems that this was due to the initiative of the humanist philosopher-prince,Giovanni Pico della Mirandola

Giovanni Pico dei conti della Mirandola e della Concordia ( ; ; ; 24 February 146317 November 1494), known as Pico della Mirandola, was an Italian Renaissance nobleman and philosopher. He is famed for the events of 1486, when, at the age of 23, ...

, who had heard Savonarola in a formal disputation in Reggio Emilia

Reggio nell'Emilia (; ), usually referred to as Reggio Emilia, or simply Reggio by its inhabitants, and known until Unification of Italy, 1861 as Reggio di Lombardia, is a city in northern Italy, in the Emilia-Romagna region. It has about 172,51 ...

and been impressed with his learning and piety. Pico was in trouble with the Church for some of his unorthodox philosophical ideas (the famous "900 theses") and was living under the protection of Lorenzo the Magnificent, the Medici ''de facto'' ruler of Florence. To have Savonarola beside him as a spiritual counsellor, he persuaded Lorenzo that the friar would bring prestige to the convent of San Marco and its Medici patrons. After some delay, apparently due to the interference of his former professor fra Vincenzo Bandelli, now Vicar General of the Order, Lorenzo succeeded in bringing Savonarola back to Florence, where he arrived in May or June of that year.

Prophet

Savonarola preached on the First Epistle of John and on theBook of Revelation

The Book of Revelation, also known as the Book of the Apocalypse or the Apocalypse of John, is the final book of the New Testament, and therefore the final book of the Bible#Christian Bible, Christian Bible. Written in Greek language, Greek, ...

, drawing such large crowds that he eventually moved to the cathedral. Without mentioning names, he made pointed allusions to tyrants who usurped the freedom of the people, and he excoriated their allies, the rich and powerful who neglected and exploited the poor. Complaining of the evil lives of a corrupt clergy, he now called for repentance and renewal before the arrival of a divine scourge. Scoffers dismissed him as an over-excited zealot and "preacher of the desperate" and sneered at his growing band of followers as ''Piagnoni''—"Weepers" or "Wailers", an epithet they adopted. In 1492 Savonarola warned of "the Sword of the Lord over the earth quickly and soon" and envisioned terrible tribulations to Rome. Around 1493 (these sermons have not survived) he began to prophesy that a New Cyrus was coming over the mountains to begin the renewal of the Church.

In September 1494 King Charles VIII of France crossed the Alps with a formidable army, throwing Italy into political chaos. Many viewed the arrival of King Charles as proof of Savonarola's gift of prophecy. Charles advanced on Florence, sacking Tuscan strongholds and threatening to punish the city for refusing to support his expedition. As the populace took to the streets to expel Piero the Unfortunate, Lorenzo de' Medici's son and successor, Savonarola led a delegation to the camp of the French king in mid-November 1494. He pressed Charles to spare Florence and enjoined him to take up his divinely appointed role as the reformer of the Church. After a short, tense occupation of the city, and another intervention by fra Girolamo (as well as the promise of a huge subsidy), the French resumed their journey southward on 28 November 1494. Savonarola now declared that by answering his call to penitence, the Florentines had begun to build a new Ark of Noah which had saved them from the waters of the divine flood. Even more sensational was the message in his sermon of 10 December:

I announce this good news to the city, that Florence will be more glorious, richer, more powerful than she has ever been; First, glorious in the sight of God as well as of men: and you, O Florence will be the reformation of all Italy, and from here the renewal will begin and spread everywhere, because this is the navel of Italy. Your counsels will reform all by the light and grace that God will give you. Second, O Florence, you will have innumerable riches, and God will multiply all things for you. Third, you will spread your empire, and thus you will have power temporal and spiritual.This astounding guarantee may have been an allusion to the traditional patriotic myth of Florence as the new Rome, which Savonarola would have encountered in his readings in Florentine history. In any case, it encompassed both temporal power and spiritual leadership.

Reformer

With Savonarola's advice and support (as a non-citizen and cleric he was ineligible to hold office), a Savonarolan political "party", dubbed "the Frateschi", took shape and steered the friar's program through the councils. The oligarchs most compromised by their service to the Medici were barred from office. A new constitution enfranchised the artisan class, opened minor civic offices to selection by lot, and granted every citizen in good standing the right to a vote in a new parliament, the Consiglio Maggiore, or Great Council. At Savonarola's urging, the Frateschi government, after months of debate, passed a "Law of Appeal" to limit the longtime practice of using exile and capital punishment as factional weapons. Savonarola declared a new era of "universal peace". On 13 January 1495 he preached his great Renovation Sermon to a huge audience in the cathedral, recalling that he had begun prophesying in Florence four years earlier, although the divine light had come to him "more than fifteen, maybe twenty years ago". He now claimed that he had predicted the deaths of Lorenzo de' Medici and ofPope Innocent VIII

Pope Innocent VIII (; ; 1432 – 25 July 1492), born Giovanni Battista Cybo (or Cibo), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 29 August 1484 to his death, in July 1492. Son of the viceroy of Naples, Cybo spent his ea ...

in 1492 and the coming of the sword to Italy—the invasion of King Charles of France. As he had foreseen, God had chosen Florence, "the navel of Italy", as his favourite and he repeated: if the city continued to do penance and began the work of renewal it would have riches, glory and power.

If the Florentines had any doubt that the promise of worldly power and glory had heavenly sanction, Savonarola emphasised this in a sermon of 1 April 1495, in which he described his mystical journey to the Virgin Mary in heaven. At the celestial throne Savonarola presents the Holy Mother a crown made by the Florentine people and presses her to reveal their future. Mary warns that the way will be hard both for the city and for him, but she assures him that God will fulfil his promises: Florence will be "more glorious, more powerful and richer than ever, extending its wings farther than anyone can imagine". She and her heavenly minions will protect the city against its enemies and support its alliance with the French. In the New Jerusalem that is Florence peace and unity will reign. Based on such visions, Savonarola promoted theocracy, and declared Christ

Jesus ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Christianity, central figure of Christianity, the M ...

the king of Florence. He saw sacred art as a tool to promote this worldview, and he was therefore only opposed to secular art, which he saw as worthless and potentially damaging.

Buoyed by liberation and prophetic promise, the Florentines embraced Savonarola's campaign to rid the city of "vice". At his repeated insistence, new laws were passed against "sodomy" (which included male and female same-sex relations), adultery, public drunkenness, and other moral transgressions, while his lieutenant Fra Silvestro Maruffi organised boys and young men to patrol the streets to curb immodest dress and behaviour. For a time, Pope Alexander VI

Pope Alexander VI (, , ; born Roderic Llançol i de Borja; epithet: ''Valentinus'' ("The Valencian"); – 18 August 1503) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 11 August 1492 until his death in 1503.

Born into t ...

(1492–1503) tolerated friar Girolamo's strictures against the Church, but he was moved to anger when Florence declined to join his new Holy League against the French invader, and blamed it on Savonarola's pernicious influence. An exchange of letters between the pope and the friar ended in an impasse which Savonarola tried to break by sending the pope "a little book" recounting his prophetic career and describing some of his more dramatic visions. This was the Compendium of Revelations, a self-dramatisation which was one of the farthest-reaching and most popular of his writings.

The pope was not mollified. He summoned the friar to appear before him in Rome, and when Savonarola refused, pleading ill health and confessing that he was afraid of being attacked on the journey, Alexander banned him from further preaching. For some months Savonarola obeyed, but when he saw his influence slipping he defied the pope and resumed his sermons, which became more violent in tone. He not only attacked secret enemies at home whom he rightly suspected of being in league with the papal Curia, he condemned the conventional, or "tepid", Christians who were slow to respond to his calls. He dramatised his moral campaign with special Masses for the youth, processions, bonfires of the vanities and religious theatre in San Marco. He and his close friend, the humanist poet Girolamo Benivieni, composed lauds and other devotional songs for the Carnival processions of 1496, 1497 and 1498, replacing the bawdy Carnival songs of the era of Lorenzo de' Medici. These continued to be copied and performed after his death, along with songs composed by Piagnoni in his memory. A number of them have survived.

Proto-Protestant

The writings of Savonarola spread widely to

The writings of Savonarola spread widely to Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

, and due to Savonarola's life and death, many people started to see the papacy as corrupted and sought a new reform of the church. Many people saw him as a martyr, including Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

, who was influenced by Savonarola's writings. Savonarola's beliefs on the doctrine of justification are similar in some respects to Martin Luther's teachings, stating that humans are not justified by themselves. Savonarola may have influenced John Calvin, but this is a matter of historical debate.

Savonarola never abandoned the dogmas of the Roman Catholic Church; for example, Savonarola held to a belief in seven sacraments and that the Church of Rome is "the mother of all other churches and the pope its head". However, his protests against papal corruption and his reliance on the Bible as the main guide link Savonarola with the later reformation. Savonarola, while revering the office of the papacy, nevertheless criticised the pope Alexander VI and his papal court. Savonarola even prophesied that Rome will come under judgement from God.the Pope may command me to do something that contravenes the law of Christian love or the Gospel. But, if he did so command, I would say to him, thou art no shepherd. Not the Roman Church, but thou errest Who are the fat kine of Bashan on the mountains of Samaria? I say they are the courtesans of Italy and Rome. Or, are there none? A thousand are too few for Rome, 10,000, 12,000, 14,000 are too few for Rome. Prepare thyself, O Rome, for great will be thy punishmentsCatholic sources, however, criticize the inclusion of Savonarola as a Protestant forerunner, because much of his theology still aligned with Rome. Despite inspiring some Protestant reformers, Savonarola also influenced some leaders of the

Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also sometimes called the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to, and as an alternative to or from similar insights as, the Protestant Reformations at the time. It w ...

.

Excommunication and death

On 12 May 1497, BorgiaPope Alexander VI

Pope Alexander VI (, , ; born Roderic Llançol i de Borja; epithet: ''Valentinus'' ("The Valencian"); – 18 August 1503) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 11 August 1492 until his death in 1503.

Born into t ...

excommunicated Savonarola, and also threatened the Florentines with an interdict if they persisted in harbouring him. After describing the contemporary Church leadership as a pockmarked whore sitting on Solomon's throne, Savonarola was excommunicated for heresy and sedition. On 18 March 1498, after much debate and steady pressure from a worried government, Savonarola withdrew from public preaching. Under the stress of excommunication, he composed his spiritual masterpiece, the '' Triumph of the Cross'', a celebration of the victory of the Cross over sin and death and an exploration of what it means to be a Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

. This he summed up in the theological virtue of ''caritas'', or love. In loving their neighbours, Christians return the love which they have received from their Creator and Savior. Savonarola hinted at performing miracles to prove his divine mission, but when a rival Franciscan preacher proposed to test that mission by walking through fire, he lost control of public discourse. Without consulting him, his confidant Fra Domenico da Pescia offered himself as his surrogate and Savonarola felt he could not afford to refuse. The first trial by fire in Florence in over four hundred years was set for 7 April.

A crowd filled the central square, eager to see if God would intervene, and if so, on which side. The nervous contestants and their delegations delayed the start of the contest for hours. A sudden rain drenched the spectators and government officials cancelled the proceedings. The crowd disbanded angrily; the burden of proof had been on Savonarola, and he was blamed for the fiasco. A mob assaulted the convent of San Marco. Fra Girolamo, Fra Domenico, and Fra Silvestro Maruffi were arrested and imprisoned. Under torture Savonarola confessed to having invented his prophecies and visions, then recanted, then confessed again. In his prison cell in the tower of the government palace he composed meditations on Psalms 51 ('' Infelix ego'') and 31 (''Tristitia obsedit me''). On the morning of 23 May 1498, the three friars were led out into the main square where, before a tribunal of high clerics and government officials, they were condemned as heretics and schismatics, and sentenced to die forthwith. Stripped of their Dominican garments in ritual degradation, they mounted the scaffold in their thin white shirts. Each on separate gallows, they were hanged, while fires were ignited below them to consume their bodies. To prevent devotees from searching for relics, their ashes were carted away and scattered in the Arno

The Arno is a river in the Tuscany region of Italy. It is the most important river of central Italy after the Tiber.

Source and route

The river originates on Monte Falterona in the Casentino area of the Apennines, and initially takes a sou ...

.

Aftermath

Resisting censorship and exile, the friars of San Marco fostered a cult of "the three martyrs" and venerated Savonarola as a saint. They encouraged women in local convents and surrounding towns to find mystical inspiration in his example, and, by preserving many of his sermons and writings, they helped keep his political as well as his religious ideas alive. The return of theMedici

The House of Medici ( , ; ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first consolidated power in the Republic of Florence under Cosimo de' Medici and his grandson Lorenzo "the Magnificent" during the first half of the 15th ...

in 1512 ended the Savonarola-inspired republic and intensified pressure against the movement, although both were briefly revived in 1527 when the Medici were once again forced out. In 1530, Medici Pope Clement VII

Pope Clement VII (; ; born Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici; 26 May 1478 – 25 September 1534) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 November 1523 to his death on 25 September 1534. Deemed "the most unfortunate o ...

(Giulio de' Medici), with the help of soldiers of the Holy Roman Emperor, restored Medici rule, and Florence became a hereditary dukedom. Savonarola's contemporary Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli (3 May 1469 – 21 June 1527) was a Florentine diplomat, author, philosopher, and historian who lived during the Italian Renaissance. He is best known for his political treatise '' The Prince'' (), writte ...

discusses the friar in Chapter VI of his book ''The Prince

''The Prince'' ( ; ) is a 16th-century political treatise written by the Italian diplomat, philosopher, and Political philosophy, political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli in the form of a realistic instruction guide for new Prince#Prince as gener ...

'', writing:

Savonarolan religious ideas found a reception elsewhere. In Germany and Switzerland the early Protestant reformers, most notably Martin Luther himself, read some of the friar's writings and praised him as a martyr and forerunner whose ideas on faith and grace anticipated Luther's own doctrine of justification by faith alone. In France many of his works were translated and published and Savonarola came to be regarded as a precursor of evangelical, or

Savonarolan religious ideas found a reception elsewhere. In Germany and Switzerland the early Protestant reformers, most notably Martin Luther himself, read some of the friar's writings and praised him as a martyr and forerunner whose ideas on faith and grace anticipated Luther's own doctrine of justification by faith alone. In France many of his works were translated and published and Savonarola came to be regarded as a precursor of evangelical, or Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

reform. In Wittenberg

Wittenberg, officially Lutherstadt Wittenberg, is the fourth-largest town in the state of Saxony-Anhalt, in the Germany, Federal Republic of Germany. It is situated on the River Elbe, north of Leipzig and south-west of the reunified German ...

, the hometown of Martin Luther, a statue of Girolamo Savonarola was erected to honour him.

Carafa Pope Paul IV

Pope Paul IV (; ; 28 June 1476 – 18 August 1559), born Gian Pietro Carafa, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 23 May 1555 to his death, in August 1559. While serving as papal nuncio in Spain, he developed ...

in 1558 declared that Savonarola was not a heretic. Savonarola had remained a believer in the dogmas of the Catholic church and even in his last major work had defended the institution of the papacy. Within the Dominican Order Savonarola was seen as a devotional figure ("the evolving image of a Counter-Reformation saintly prelate"), and in this benevolent guise his memory lived on. Philip Neri

Saint Philip Neri , born Filippo Romolo Neri, (22 July 151526 May 1595) was an Italian Catholic priest who founded the Congregation of the Oratory, a society of secular clergy dedicated to pastoral care and charitable work. He is sometimes refe ...

, founder of the Oratorians, a Florentine who had been educated by the San Marco Dominicans, also defended Savonarola's memory.

18th century Spanish defense

In the early 18th century, Savonarola’s reputation was defended in Spain by the Dominican friar Manuel Joseph de Medrano, ''Predicador'' General and ''Choronista'' of the Dominican Order. Medrano authored the ''Vida de la admirable Virgen Santa Inés de Monte Policiano'', which included atheological

Theology is the study of religious belief from a religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of an ...

defense of Savonarola's sanctity and prophetic mission. His writings were praised and analyzed in ''Tertulia histórica y apologética'' (Zaragoza, c. 1730) by the jurist Doctor Jayme Ardanaz y Centellas. In this work, Medrano's scholarship, moderation, and courteous style were highlighted, and his arguments against the criticisms of Savonarola by the renowned Benedictine scholar Benito Jerónimo Feijóo were carefully examined in a scholarly dialogue. This Spanish Dominican contribution reflects the continued cross-European reassessment of Savonarola’s moral and prophetic role well before the modern period.

19th century

In the mid-nineteenth century, the "New Piagnoni" found inspiration in the friar's writings and sermons for the Italian national awakening known as theRisorgimento

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the annexation of various states of the Italian peninsula and its outlying isles to the Kingdom of ...

. By emphasising his political activism over his puritanism and cultural conservatism they restored Savonarola's voice for radical political change. The venerable pre-Reformation icon ceded to the fiery Renaissance reformer. This somewhat anachronistic image, fortified by much new scholarship, informed the major new biography by Pasquale Villari

Pasquale Villari (3 October 1827 – 11 December 1917) was an Italian historian and politician.

Early life and publications

Villari was born in Naples and took part in the risings of 1848 there against the Bourbons and subsequently fled to Flo ...

, who regarded Savonarola's preaching against Medici despotism as the model for the Italian struggle for liberty and national unification. In Germany, the Catholic theologian and church historian Joseph Schnitzer

Joseph Schnitzer (15 June 1859 in Lauingen – 1 December 1939 in Munich) was a theologian. He started teaching at Munich University in 1902.

Literary works

* ''Quellen und Forschungen zur Geschichte Savonarolas'', 6 vols., 1902–1914

* ''Sa ...

edited and published contemporary sources which illuminated Savonarola's career. In 1924 he crowned his vast research with a comprehensive study of Savonarola's life and times in which he presented the friar as the last best hope of the Catholic Church before the catastrophe of the Protestant Reformation. In the Italian People's Party founded by Don Luigi Sturzo

Luigi Sturzo (; 26 November 1871 – 8 August 1959) was an Italian Catholic priest and prominent politician. He was known in his lifetime as a former Christian socialist turned Popolarismo, popularist, and is considered one of the fathers of th ...

in 1919, Savonarola was revered as a champion of social justice, and after 1945 he was held up as a model of reformed Catholicism by leaders of the Christian Democratic Party. From this milieu, in 1952 came the third of the major Savonarola biographies, the ''Vita di Girolamo Savonarola'' by Roberto Ridolfi. For the next half century Ridolfi was the guardian of the friar's saintly memory as well as the dean of Savonarola research which he helped grow into a scholarly industry. Today, most of Savonarola's treatises and sermons and many of the contemporary sources (chronicles, diaries, government documents, and literary works) are available in critical editions.

The present-day Church has considered his beatification

Beatification (from Latin , "blessed" and , "to make") is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a deceased person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in their name. ''Beati'' is the p ...

. In 2020, a devotional society (The Savonarola Society) dedicated to promoting his cause for Canonisation was founded, in 2024 this group began The Opera Savonarolae (The Savonarola Project) in collaboration with Studio Fratesco, attempting to translate all of Savonarola's works into English as well as many previously untranslated secondary sources, the first publication in this project was a reprint of Fr. J L O'Neil's 1898 biography Jerome Savonarola: A Sketch. In December 2024, the group received a personal greeting from Pope Francis

Pope Francis (born Jorge Mario Bergoglio; 17 December 1936 – 21 April 2025) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 13 March 2013 until Death and funeral of Pope Francis, his death in 2025. He was the fi ...

.

The Polish National Catholic Church, a church not in communion with Rome and a branch of the Union of Utrecht

The Union of Utrecht () was an alliance based on an agreement concluded on 23 January 1579 between a number of Habsburg Netherlands, Dutch provinces and cities, to reach a joint commitment against the king, Philip II of Spain. By joining forces ...

, named its Theological Seminary after Savonarola.

Cultural influence

Music

*William Byrd

William Byrd (; 4 July 1623) was an English Renaissance composer. Considered among the greatest composers of the Renaissance, he had a profound influence on composers both from his native country and on the Continental Europe, Continent. He i ...

used the text of Savonarola's '' Infelix ego'' in his work of the same name as part of the '' Cantiones Sacrae 1591'', pp. xxiv–xvi.

* Charles Villiers Stanford

Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (30 September 1852 – 29 March 1924) was an Anglo-Irish composer, music teacher, and conductor of the late Romantic music, Romantic era. Born to a well-off and highly musical family in Dublin, Stanford was ed ...

wrote an opera

Opera is a form of History of theatre#European theatre, Western theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by Singing, singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically ...

titled ''Savonarola'', which had its premiere in Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg,. is the List of cities in Germany by population, second-largest city in Germany after Berlin and List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, 7th-lar ...

on 18 April 1884.

* Luigi Dallapiccola used text from Savonarola's Meditation on the Psalm ''My hope is in Thee, O Lord'' in his 1938 choral work '' Canti di prigionia''.

Fiction

* Lenau, Nikolaus, ''Savonarola'' (poem, 1837) * Eliot, George, '' Romola'' (novel, 1863) * Mann, Thomas, '' Fiorenza'' (play, 1909) * Herrmann, Bernhard, ''Savonarola im Feuer'' (1909) * The 1917 story "'Savonarola' Brown" byMax Beerbohm

Sir Henry Maximilian Beerbohm (24 August 1872 – 20 May 1956) was an English essayist, Parody, parodist and Caricature, caricaturist under the signature Max. He first became known in the 1890s as a dandy and a humorist. He was the theatre crit ...

(published in '' Seven Men'') concerns an aspiring playwright, author of an unfinished, unintentionally absurd retelling of the life of Savonarola. (His four-act play took him nine years to write, is eighteen pages long, and features a romance between Savonarola and Lucrezia Borgia

Lucrezia Borgia (18 April 1480 – 24 June 1519) was an Italian noblewoman of the House of Borgia who was the illegitimate daughter of Pope Alexander VI and Vannozza dei Cattanei. She was a former governor of Spoleto.

Her family arranged ...

, and also cameos by Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

, Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 1452 - 2 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested o ...

, and St. Francis of Assisi.)

* Van Wyck, William, ''Savonarola: A Biography in Dramatic Episodes'' (1926)

* Hines and King, ''Fire of Vanity'' (play, 1930)

* Salacrou, Armand, ''Le terre est ronde'' (1938)

* The novel ''Kámen a bolest'' ("suffering and the stone") (1942), Karel Schulz's historical novel about the life of Michelangelo, features Savonarola as an important character.

* Bacon, Wallace A., Savonarola: A Play in Nine Scenes (1950)

* '' The Agony and the Ecstasy'' (1961), Irving Stone's novelisation of Michelangelo's life, depicts the events in Florence from the Medici's point of view.

* The fourth segment of Walerian Borowczyk

Walerian Borowczyk (21 October 1923 – 3 February 2006) was a Polish film director described by film critics as a "genius who also happened to be a pornographer". He directed 40 films between 1946 and 1988. Borowczyk settled in Paris in 1959. A ...

's 1974 anthology film

An anthology film (also known as an omnibus film or a portmanteau film) is a single film consisting of three or more shorter films, each complete in itself and distinguished from the other, though frequently tied together by a single theme, premise ...

, '' Immoral Tales'', is set during the reign of Pope Alexander VI. A character called "Friar Hyeronimus Savonarola", played by Philippe Desboeuf, holds a sermon in which he publicly condemns the corruption of the church and the sexual depravity of the papacy. Borowczyk juxtaposes Savonarola's sermon with the Pope enjoying a threesome with his daughter, Lucrezia Borgia

Lucrezia Borgia (18 April 1480 – 24 June 1519) was an Italian noblewoman of the House of Borgia who was the illegitimate daughter of Pope Alexander VI and Vannozza dei Cattanei. She was a former governor of Spoleto.

Her family arranged ...

, and his son, Cesare Borgia

Cesare Borgia (13 September 1475 – 12 March 1507) was a Cardinal (Catholic Church)#Cardinal_deacons, cardinal deacon and later an Italians, Italian ''condottieri, condottiero''. He was the illegitimate son of Pope Alexander VI of the Aragonese ...

. Savonarola is arrested and publicly burned to death.

* In the 1976 film '' Network'', the network programming executive played by Faye Dunaway refers to crusading reporter Howard Beale as "a magnificent messianic figure, inveighing against the hypocrisies of our times, a strip

Strip, Strips or Stripping may refer to:

Places

* Aouzou Strip, a strip of land following the northern border of Chad that had been claimed and occupied by Libya

* Caprivi Strip, narrow strip of land extending from the Okavango Region of Nami ...

Savonarola, Monday through Friday".

* In her novel '' The Passion of New Eve'' (1977), Angela Carter

Angela Olive Pearce (formerly Carter, Stalker; 7 May 1940 – 16 February 1992), who published under the name Angela Carter, was an English novelist, short story writer, poet, and journalist, known for her feminist, magical realism, and picar ...

describes the preaching leader of an army of god-fearing child soldiers as a "precocious Savonarola".

* The novel ''The Palace

''The Palace'' is a British drama television series that aired on ITV (TV network), ITV in 2008. Produced by Company Pictures for the ITV network, it was created by Tom Grieves and follows a fictional British Royal Family in the aftermath of t ...

'' (1978) by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro features Savonarola as the main antagonist of the vampire Saint Germain.

* The historical fantasy novel '' The Dragon Waiting'' (1984) by John M. Ford has Savonarola as one of the antagonists in chapter 3, set in the Medici court.

* The novel '' Sabbath's Theater'' (1995) by Philip Roth

Philip Milton Roth (; March 19, 1933 – May 22, 2018) was an American novelist and short-story writer. Roth's fiction—often set in his birthplace of Newark, New Jersey—is known for its intensely autobiographical character, for philosophical ...

makes reference to Savonarola.

* The novel ''The Birth of Venus

''The Birth of Venus'' ( ) is a painting by the Italian artist Sandro Botticelli, probably executed in the mid-1480s. It depicts the goddess Venus (mythology), Venus arriving at the shore after her birth, when she had emerged from the sea ful ...

'' (2003 ) by Sarah Dunant makes extensive references to Savonarola.

* In episode 7 (2003) of the manga-anime series '' Gunslinger Girl'', two of the protagonists, Jean and Rico, visit Florence. There Savonarola is mentioned among other famous people who lived in the city, while he shares his surname with one of the series antagonists.

* The novel '' The Rule of Four'' (2004) by Ian Caldwell and Dustin Thomason makes extensive references to Savonarola.

* In the novel ''I, Mona Lisa'' (2006) (UK title '' Painting Mona Lisa'') by Jeanne Kalogridis, he is given a negative slant, as the Medicis are portrayed as sympathetic and noble.

* The novel '' The Enchantress of Florence'' (2008) by Salman Rushdie

Sir Ahmed Salman Rushdie ( ; born 19 June 1947) is an Indian-born British and American novelist. His work often combines magic realism with historical fiction and primarily deals with connections, disruptions, and migrations between Eastern wor ...

* The young adult novel '' The Smile'' (2008) by Donna Jo Napoli shows Savonarola as he was observed by a young Mona Lisa.

* In the novel ''Wolf Hall

''Wolf Hall'' is a 2009 historical novel by English author Hilary Mantel, published by Fourth Estate, named after the Seymour family's seat of Wolfhall, or Wulfhall, in Wiltshire. Set in the period from 1500 to 1535, ''Wolf Hall'' is a sym ...

'' (2009) by Hilary Mantel

Dame Hilary Mary Mantel ( ; born Thompson; 6 July 1952 – 22 September 2022) was a British writer whose work includes historical fiction, personal memoirs and short stories. Her first published novel, ''Every Day Is Mother's Day'', was releas ...

, the Bonfire of the Vanities is brought up in a story by the protagonist, Thomas Cromwell.

* Savonarola appears as a main assassination target in the videogame '' Assassin's Creed II'' (2009).

* In the novel, ''The Poet Prince'' (2010), Kathleen McGowan portrays him as an enemy of the Tuscan people in their pursuit of artistic fame during his reign.

* Savonarola's life story is explored in the novel ''Fanatics'' (2011) by William Bell and his ghost plays an important role in the story.

* In Showtime's '' The Borgias'', Savonarola is a recurring character in the two first seasons and is portrayed by Steven Berkoff

Steven Berkoff (born Leslie Steven Berks; 3 August 1937) is an English actor, author, playwright, theatre practitioner and theatre director.

As a theatre maker he is recognised for staging work with a heightened performance style known as "Be ...

. His burning takes place in the episode '' The Confession''.

* In the Netflix series ''Borgia

The House of Borgia ( ; ; Spanish and ; ) was a Spanish noble family, which rose to prominence during the Italian Renaissance. They were from Xàtiva, Kingdom of Valencia, the surname being a toponymic from the town of Borja, then in the Cro ...

'', Savonarola is portrayed by Iain Glen

Iain Alan Sutherland Glen (born 24 June 1961) is a Scottish actor. He has appeared as Dr. Alexander Isaacs/Tyrant in three films of the Resident Evil (film series), ''Resident Evil'' film series (2004–2016) and as Ser Jorah Mormont, Jorah Morm ...

in season 2 (2013).

* Savonarola is a character in Canadian playwright Jordan Tannahill's 2016 play ''Botticelli in the Fire''.

* In the Rai Fiction series ''Medici

The House of Medici ( , ; ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first consolidated power in the Republic of Florence under Cosimo de' Medici and his grandson Lorenzo "the Magnificent" during the first half of the 15th ...

'', Savonarola is portrayed by Francesco Montanari in season 2 (2018).

* The historical fantasy and alternate history novel ''Lent

Lent (, 'Fortieth') is the solemn Christianity, Christian religious moveable feast#Lent, observance in the liturgical year in preparation for Easter. It echoes the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring Temptation of Christ, t ...

'' (2019) by Jo Walton

Jo Walton (born 1964) is a Welsh-Canadian fantasy and science fiction writer and poet. She is best known for the fantasy novel '' Among Others'', which won the Hugo and Nebula Awards in 2012, and '' Tooth and Claw'', a Victorian-era novel w ...

is a retelling of Savonarola's life.

* Three Fires (2023) by Denise Mina is a retelling of Savonarola's life.

Bibliography

Almost thirty volumes of Savonarola's sermons and writings have so far been published in the ''Edizione nazionale delle Opere di Girolamo Savonarola'' (Rome, Angelo Belardetti, 1953 to the present). For editions of the 15th and 16th centuries see ''Catalogo delle edizioni di Girolamo Savonarola (secc. xv–xvi)'' ed. P. Scapecchi (Florence, 1998, ). * ''Prison Meditations on Psalms 51 and 31'' ed. John Patrick Donnelly, S.J. () * The Compendium of Revelations in Bernard McGinn ed. ''Apocalyptic Spirituality: Treatises and Letters ofLactantius

Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius () was an early Christian author who became an advisor to Roman emperor Constantine I, guiding his Christian religious policy in its initial stages of emergence, and a tutor to his son Crispus. His most impo ...

, Adso of Montier-en-Der, Joachim of Fiore, the Franciscan Spirituals, Savonarola'' (New York, 1979, )

* Savonarola ''A Guide to Righteous Living and Other Works'' ed. Konrad Eisenbichler (Toronto, Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2003, )

* ''Selected Writings of Girolamo Savonarola Religion and Politics, 1490–1498'' ed. Anne Borelli and Maria Pastore Passaro (New Haven, Yale University Press

Yale University Press is the university press of Yale University. It was founded in 1908 by George Parmly Day and Clarence Day, grandsons of Benjamin Day, and became a department of Yale University in 1961, but it remains financially and ope ...

, 2006, )

*

*

References

Further reading

*Dall'Aglio, Stefano, ''Savonarola and Savonarolism'' (Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies. 2010). * Herzig,Tamar, ''Savonarola's Women: Visions and Reform in Renaissance Italy'' (Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 2008). * Lowinsky, Edward E., ''Music in the Culture of the Renaissance and Other Essays'' (University of Chicago Press, 1989). *Macey, Patrick, ''Bonfire Songs: Savonarola's Musical Legacy'' (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1998). *Martines, Lauro, ''Fire in the City: Savonarola and the Struggle for Renaissance Florence'' (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006) * Meltzoff, Stanley, ''Botticelli, Signorelli and Savonarola: Theologia Poetica and Painting from Boccaccio to Poliziano'' (Florence: L.S. Olschki, 1987). *Morris, Samantha, ''The Pope's Greatest Adversary: Girolamo Savonarola'' (South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword History, 2021). *Polizzotto, Lorenzo, ''The Elect Nation: The Savonarolan Movement in Florence, 1494–1545'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 1994). *Ridolfi, Roberto, ''Vita di Girolamo Savonarola'', ed. A.F. Verde (Florence, 6th ed., 1997). * Roeder, Ralph Edmund LeClercq, ''The Man of the Renaissance: Four Lawgivers: Savonarola, Machiavelli, Castiglione, Aretino'' (The Viking Press, 1933). *Steinberg, Ronald M., ''Fra Girolamo Savonarola, Florentine Art, and Renaissance Historiography'' (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1977). * Smiles, L.L.D., Samuel, "Endurance to the EndSavonarola", Ch. VI of ''Duty: With Illustrations of Courage, Patience, & Endurance'' (London: John Murray, 1880). * Strathern, Paul, ''Death in Florence: The Medici, Savanarola, and the Battle for the Soul of a Renaissance City'' (New York, London: Pegasus Books, 2015). * Villari, Pasquale, ''Life and Times of Girolamo Savonarola'', 2 vols. (London, 1888) * Weinstein, Donald, ''Savonarola: The Rise and Fall of a Renaissance Prophet'' (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011) *Weinstein, Donald and Hotchkiss, Valerie R., eds. ''Girolamo Savonarola Piety, Prophecy and Politics in Renaissance Florence'', Catalogue of the Exhibition (Dallas, Bridwell Library, 1994).External links

Catholic Encyclopedia entry on Girolamo Savonarola

''Predica dell'arte del bene morire''

From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is a research library in Washington, D.C., serving as the library and research service for the United States Congress and the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It also administers Copyright law o ...

''Savonarola's Visions'', documentary about Girolamo Savonarola

{{DEFAULTSORT:Savonarola, Girolamo Executed Roman Catholic priests Italian Roman Catholics Italian torture victims Italian Dominicans People excommunicated by the Catholic Church People executed by the Papal States by burning People executed for heresy Religious leaders from Ferrara Heads of state of Florence University of Ferrara alumni 1452 births 1498 deaths 15th-century Italian Roman Catholic priests Proto-Protestants Dominican Order in Florence Friars of San Marco, Florence People of the Italian War of 1494–1495