George Meade on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was an American military officer who served in the

Meade was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the 3rd Artillery. He worked for a summer as an assistant surveyor on the construction of the

Meade was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the 3rd Artillery. He worked for a summer as an assistant surveyor on the construction of the

On November 5, 1862,

On November 5, 1862,

Meade rushed the remainder of his army to Gettysburg and deployed his forces for a defensive battle. Meade was only four days into his leadership of the Army of the Potomac and informed his corps commanders that he would provide quick decisions and entrust them with the authority to carry out those orders the best way they saw fit. He also made it clear that he was counting on the corps commanders to provide him with sound advice on strategy.

Since Meade was new to high command, he did not remain in headquarters but constantly moved about the battlefield, issuing orders and ensuring that they were followed. Meade gave orders for the Army of the Potomac to move forward in a broad front to prevent Lee from flanking them and threatening the cities of Baltimore and Washington D.C. He also issued a conditional plan for a retreat to Pipe Creek, Maryland in case things went poorly for the Union. By 6 pm on the evening of July 1, 1863, Meade sent a telegram to Washington informing them of his decision to concentrate forces and make a stand at Gettysburg.

On July 2, 1863, Meade continued to monitor and maintain the placement of the troops. He was outraged when he discovered that Daniel Sickles had moved his Corps one mile forward to high ground without Meade's permission and left a gap in the line which threatened Sickles' right flank. Meade recognized that

Meade rushed the remainder of his army to Gettysburg and deployed his forces for a defensive battle. Meade was only four days into his leadership of the Army of the Potomac and informed his corps commanders that he would provide quick decisions and entrust them with the authority to carry out those orders the best way they saw fit. He also made it clear that he was counting on the corps commanders to provide him with sound advice on strategy.

Since Meade was new to high command, he did not remain in headquarters but constantly moved about the battlefield, issuing orders and ensuring that they were followed. Meade gave orders for the Army of the Potomac to move forward in a broad front to prevent Lee from flanking them and threatening the cities of Baltimore and Washington D.C. He also issued a conditional plan for a retreat to Pipe Creek, Maryland in case things went poorly for the Union. By 6 pm on the evening of July 1, 1863, Meade sent a telegram to Washington informing them of his decision to concentrate forces and make a stand at Gettysburg.

On July 2, 1863, Meade continued to monitor and maintain the placement of the troops. He was outraged when he discovered that Daniel Sickles had moved his Corps one mile forward to high ground without Meade's permission and left a gap in the line which threatened Sickles' right flank. Meade recognized that  On July 3, 1863, Meade gave orders for the XII Corps and XI Corps to retake the lost portion of Culp's Hill and personally rode the length of the lines from Cemetery Ridge to Little Round Top to inspect the troops. His headquarters were in the Leister House directly behind Cemetery Ridge which exposed it to the 150-gun cannonade which began at 1 pm. The house came under direct fire from incorrectly targeted Confederate guns; Butterfield was wounded and sixteen horses tied up in front of the house were killed. Meade did not want to vacate the headquarters and make it more difficult for messages to find him, but the situation became too dire and the house was evacuated.

During the three days, Meade made excellent use of capable subordinates, such as Maj. Gens. John F. Reynolds and Winfield S. Hancock, to whom he delegated great responsibilities. He reacted swiftly to fierce assaults on his line's left and right which culminated in Lee's disastrous assault on the center, known as

On July 3, 1863, Meade gave orders for the XII Corps and XI Corps to retake the lost portion of Culp's Hill and personally rode the length of the lines from Cemetery Ridge to Little Round Top to inspect the troops. His headquarters were in the Leister House directly behind Cemetery Ridge which exposed it to the 150-gun cannonade which began at 1 pm. The house came under direct fire from incorrectly targeted Confederate guns; Butterfield was wounded and sixteen horses tied up in front of the house were killed. Meade did not want to vacate the headquarters and make it more difficult for messages to find him, but the situation became too dire and the house was evacuated.

During the three days, Meade made excellent use of capable subordinates, such as Maj. Gens. John F. Reynolds and Winfield S. Hancock, to whom he delegated great responsibilities. He reacted swiftly to fierce assaults on his line's left and right which culminated in Lee's disastrous assault on the center, known as

During the fall of 1863, the Army of the Potomac was weakened by the transfer of the XI and XII Corps to the Western Theater. Meade felt pressure from Halleck and the Lincoln administration to pursue Lee into Virginia but he was cautious due to a misperception that Lee's Army was 70,000 in size when the reality was they were only 55,000 compared to the Army of the Potomac at 76,000. Many of the Union troop replacements for the losses suffered at Gettysburg were new recruits and it was uncertain how they would perform in combat.

Lee petitioned Jefferson Davis to allow him to take the offensive against the cautious Meade which would also prevent further Union troops being sent to the Western Theater to support William Rosencrans at the Battle of Chickamauga.

During the fall of 1863, the Army of the Potomac was weakened by the transfer of the XI and XII Corps to the Western Theater. Meade felt pressure from Halleck and the Lincoln administration to pursue Lee into Virginia but he was cautious due to a misperception that Lee's Army was 70,000 in size when the reality was they were only 55,000 compared to the Army of the Potomac at 76,000. Many of the Union troop replacements for the losses suffered at Gettysburg were new recruits and it was uncertain how they would perform in combat.

Lee petitioned Jefferson Davis to allow him to take the offensive against the cautious Meade which would also prevent further Union troops being sent to the Western Theater to support William Rosencrans at the Battle of Chickamauga.

The Army of the Potomac was stationed along the north bank of the Rapidan River and Meade made his headquarters in

The Army of the Potomac was stationed along the north bank of the Rapidan River and Meade made his headquarters in

The Union Army moved ponderously slowly toward their new positions and Meade lashed out at Maj. Gen.

The Union Army moved ponderously slowly toward their new positions and Meade lashed out at Maj. Gen.

Although he fought during the Appomattox Campaign, Grant and Sheridan received most of the credit and Meade was not present when Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House.

With the war over, the Army of the Potomac was disbanded on June 28, 1865, and Meade's command of it ended.

Although he fought during the Appomattox Campaign, Grant and Sheridan received most of the credit and Meade was not present when Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House.

With the war over, the Army of the Potomac was disbanded on June 28, 1865, and Meade's command of it ended.

Meade was presented with a gold medal from the

Meade was presented with a gold medal from the

File:George Gordon Meade Memorial, DC.jpg, George Gordon Meade Memorial, by Charles Grafly, in front of the E. Barrett Prettyman Federal Courthouse in Washington, D.C.

File:Phila MeadeHouse00.jpg, In honor of his war service, the city of Philadelphia gifted a house at 1836 Delancey Place to Meade's wife

File:George Meade monument.JPG, Equestrian statue of Meade by Henry Kirke Bush-Brown, on the

George G. Meade collection

including papers covering all aspects of his career, are available for research use at the

General Meade Society of Philadelphia

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Meade, George 1815 births 1872 deaths American civil engineers American topographers Burials at Laurel Hill Cemetery (Philadelphia) Deaths from pneumonia in Pennsylvania Fort Meade, Florida Lighthouse builders Meade County, South Dakota Meade family Military personnel from Philadelphia Pennsylvania Reserves People from Cádiz People of Pennsylvania in the American Civil War Union army generals United States Army Corps of Topographical Engineers United States Army personnel of the Mexican–American War United States Army personnel of the Seminole Wars United States Military Academy alumni Pennsylvania Democrats Members of the American Philosophical Society

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

and the Union army as Major General in command of the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the primary field army of the Union army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the Battle of ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

from 1863 to 1865. He fought in many of the key battles of the Eastern theater and defeated the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was a field army of the Confederate States Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most often arrayed agains ...

led by General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

at the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was a three-day battle in the American Civil War, which was fought between the Union and Confederate armies between July 1 and July 3, 1863, in and around Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The battle, won by the Union, ...

.

He was born in Cádiz, Spain, to a wealthy Philadelphia merchant family and graduated from the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

in 1835. He fought in the Second Seminole War

The Second Seminole War, also known as the Florida War, was a conflict from 1835 to 1842 in Florida between the United States and groups of people collectively known as Seminoles, consisting of Muscogee, Creek and Black Seminoles as well as oth ...

and the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

. He served in the United States Army Corps of Topographical Engineers and directed construction of lighthouses in Florida and New Jersey from 1851 to 1856 and the United States Lake Survey from 1857 to 1861.

His Civil War service began as brigadier general with the Pennsylvania Reserves, building defenses around Washington D.C. He fought in the Peninsula Campaign

The Peninsula campaign (also known as the Peninsular campaign) of the American Civil War was a major Union operation launched in southeastern Virginia from March to July 1862, the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. The oper ...

and the Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate States Army, Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army ...

. He was severely wounded at the Battle of Glendale

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

and returned to lead his brigade at the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confederate ...

. As a division commander, he won the Battle of South Mountain

The Battle of South Mountain, known in several early Southern United States, Southern accounts as the Battle of Boonsboro Gap, was fought on September 14, 1862, as part of the Maryland campaign of the American Civil War. Three pitched battles ...

and assumed temporary command of the I Corps at the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam ( ), also called the Battle of Sharpsburg, particularly in the Southern United States, took place during the American Civil War on September 17, 1862, between Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virgi ...

. Meade's division broke through the lines at the Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat between the Union Army, Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Major general ( ...

but were forced to retreat due to lack of support. Meade was promoted to major general and commander of the V Corps, which he led during the Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the American Civil War (1861–1865), and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville campaign.

Confederate General Robert E. Lee's risky decision to divide h ...

.

He was appointed to command the Army of the Potomac just three days before the Battle of Gettysburg and arrived on the battlefield after the first day's action on July 1, 1863. He organized his forces on favorable ground to fight an effective defensive battle against Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and repelled a series of massive assaults throughout the next two days. While elated about the victory, President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

was critical of Meade due to his perception of an ineffective pursuit during the retreat, which allowed Lee and his army to escape back to Virginia. That fall, Meade's troops had a minor victory in the Bristoe Campaign but a stalemate at the Battle of Mine Run

The Battle of Mine Run, also known as Payne's Farm, or New Hope Church, or the Mine Run campaign (November 27 – December 2, 1863), was conducted in Orange County, Virginia, in the American Civil War.

An unsuccessful attempt of the Union ...

. Meade's cautious approach prompted Lincoln to look for a new commander of the Army of the Potomac.

In 1864–1865, Meade continued to command the Army of the Potomac through the Overland Campaign

The Overland Campaign, also known as Grant's Overland Campaign and the Wilderness Campaign, was a series of battles fought in Virginia during May and June 1864, towards the end of the American Civil War. Lieutenant general (United States), Lt. G ...

, the Richmond–Petersburg Campaign, and the Appomattox Campaign, but he was overshadowed by the direct supervision of the general-in-chief, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

, who accompanied him throughout these campaigns. Grant conducted most of the strategy during these campaigns, leaving Meade with significantly less influence than before. After the war, Meade commanded the Military Division of the Atlantic from 1865 to 1866 and again from 1869 to 1872. He oversaw the formation of the state governments and reentry into the United States for five southern states through his command of the Department of the South from 1866 to 1868 and the Third Military District

The Third Military District of the U.S. Army was one of five temporary administrative units of the U.S. War Department that existed in the American South. The district was stipulated by the Reconstruction Acts during the Reconstruction period fo ...

in 1872. Meade was subjected to intense political rivalries within the Army, notably with Major Gen. Daniel Sickles

Daniel Edgar Sickles (October 20, 1819May 3, 1914) was an American politician, American Civil War , Civil War veteran, and diplomat. He served in the United States House of Representatives , U.S. House of Representatives both before and after t ...

, who tried to discredit Meade's role in the victory at Gettysburg. He had a notoriously short temper which earned him the nickname of "Old Snapping Turtle".

Early life and education

Meade was born on December 31, 1815, in Cádiz, Spain, the eighth of ten children of Richard Worsam Meade and Margaret Coats Butler. His grandfather Irishman George Meade was a wealthy merchant and land speculator in Philadelphia. His father was wealthy due to Spanish-American trade and was appointed U.S. naval agent. He was ruined financially because of his support of Spain in thePeninsular War

The Peninsular War (1808–1814) was fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Kingdom of Portugal, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French ...

; his family returned to the United States in 1817, in precarious financial straits.

Meade attended elementary school in Philadelphia and the American Classical and Military Lyceum, a private school in Philadelphia modeled after the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. His father died in 1828 when George was 12 years old and he was taken out of the Germantown military academy. George was placed in a school run by Salmon P. Chase in Washington D.C.; however, it closed after a few months due to Chase's other obligations. He was then placed in the Mount Hope Institution in Baltimore, Maryland.

Meade entered the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

at West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

on July 1, 1831. He would have preferred to attend college and study law and did not enjoy his time at West Point. He graduated 19th in his class of 56 cadets in 1835. He was uninterested in the details of military dress and drills and accumulated 168 demerits, only 32 short of the amount that would trigger a mandatory dismissal.

Topographical Corps and Mexican-American War

Meade was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the 3rd Artillery. He worked for a summer as an assistant surveyor on the construction of the

Meade was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the 3rd Artillery. He worked for a summer as an assistant surveyor on the construction of the Long Island Railroad

The Long Island Rail Road , or LIRR, is a railroad in the southeastern part of the U.S. state of New York, stretching from Manhattan to the eastern tip of Suffolk County on Long Island. The railroad currently operates a public commuter rail ...

and was assigned to service in Florida. He fought in the Second Seminole War and was assigned to accompany a group of Seminole to Indian territory in the West. He became a full second lieutenant by year's end, and in the fall of 1836, after the minimum required one year of service, he resigned from the army. He returned to Florida and worked as a private citizen for his brother-in-law, James Duncan Graham, as an assistant surveyor to the United States Army Corps of Topographical Engineers on a railroad project. He conducted additional survey work for the Topographical Engineers on the Texas-Louisiana border, the Mississippi River Delta and the northeastern boundary of Maine and Canada.

In 1842, a congressional measure was passed which excluded civilians from working in the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers and Meade reentered the army as a second lieutenant in order to continue his work with them. In November 1843, he was assigned to work on lighthouse construction under Major Hartman Bache. He worked on the Brandywine Shoal lighthouse in the Delaware Bay.

Meade served in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

and was assigned to the staffs of Generals Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military officer and politician who was the 12th president of the United States, serving from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States ...

and Robert Patterson. He fought at the Battle of Palo Alto

The Battle of Palo Alto () was the first major battle of the Mexican–American War and was fought on May 8, 1846, on disputed ground five miles (8 km) from the modern-day city of Brownsville, Texas. A force of some 3,700 Mexico, Mexican t ...

, the Battle of Resaca de la Palma and the Battle of Monterrey. He served under General William Worth at Monterrey and led a party up a hill to attack a fortified position. He was brevetted to first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a se ...

and received a gold-mounted sword for gallantry from the citizens of Philadelphia.

In 1849, Meade was assigned to Fort Brooke

Fort Brooke was a historical military post established at the mouth of the Hillsborough River (Florida), Hillsborough River in present-day Tampa, Florida in 1824. Its original purpose was to serve as a check on and trading post for the native S ...

in Florida to assist with Seminole attacks on settlements. In 1851, he led the construction of the Carysfort Reef Light in Key Largo. In 1852, the Topographical Corps established the United States Lighthouse Board and Meade was appointed the Seventh District engineer with responsibilities in Florida. He led the construction of Sand Key Light in Key West; Jupiter Inlet Light in Jupiter, Florida

Jupiter is the northernmost town in Palm Beach County, Florida, United States. According to the 2020 US Census, the town had a population of 61,047. It is 84 miles north of Miami and 15 miles north of West Palm Beach, Florida, West Palm Beach. ...

; and Sombrero Key Light in the Florida Keys

The Florida Keys are a coral island, coral cay archipelago off the southern coast of Florida, forming the southernmost part of the continental United States. They begin at the southeastern coast of the Florida peninsula, about south of Miami a ...

. When Bache was reassigned to the West Coast, Meade took over responsibility for the Fourth District in New Jersey and Delaware and built the Barnegat Light on Long Beach Island, Absecon Light in Atlantic City

Atlantic City, sometimes referred to by its initials A.C., is a Jersey Shore seaside resort city in Atlantic County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.

Atlantic City comprises the second half of the Atlantic City- Hammonton metropolitan sta ...

, and the Cape May Light in Cape May

Cape May consists of a peninsula and barrier island system in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It is roughly coterminous with Cape May County and runs southwards from the New Jersey mainland, separating Delaware Bay from the Atlantic Ocean. Th ...

. He also designed a hydraulic lamp that was used in several American lighthouses. Meade received an official promotion to first lieutenant in 1851, and to captain in 1856.

In 1857, Meade was given command of the Lakes Survey mission of the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes spanning the Canada–United States border. The five lakes are Lake Superior, Superior, Lake Michigan, Michigan, Lake Huron, H ...

. Completion of the survey of Lake Huron

Lake Huron ( ) is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is shared on the north and east by the Canadian province of Ontario and on the south and west by the U.S. state of Michigan. The name of the lake is derived from early French ex ...

and extension of the surveys of Lake Michigan

Lake Michigan ( ) is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is the second-largest of the Great Lakes by volume () and depth () after Lake Superior and the third-largest by surface area (), after Lake Superior and Lake Huron. To the ...

down to Grand and Little Traverse Bays were done under his command. Prior to Captain Meade's command, Great Lakes' water level readings were taken locally with temporary gauges; a uniform plane of reference had not been established. In 1858, based on his recommendation, instrumentation was set in place for the tabulation of records across the basin. Meade stayed with the Lakes Survey until the 1861 outbreak of the Civil War.

American Civil War

Meade was appointed brigadier general of volunteers on August 31, 1861, a few months after the start of theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, based on the strong recommendation of Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin. He was assigned command of the 2nd Brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military unit, military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute ...

of the Pennsylvania Reserves under General George A. McCall. The Pennsylvania Reserves were initially assigned to the construction of defenses around Washington, D.C.

Peninsula campaign

In March 1862, the Army of the Potomac was reorganized into four corps, Meade served as part of the I Corps under Maj. GenIrvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell (October 15, 1818 – May 4, 1885) was an American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War. In 1862, he was given command of the ...

. The I Corps was stationed in the Rappahannock area, but in June, the Pennsylvania Reserves were detached and sent to the Peninsula to reinforce the main army. With the onset of the Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate States Army, Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army ...

on June 25, the Reserves were directly involved in the fighting. At Mechanicsville and Gaines Mill, Meade's brigade was mostly held in reserve, but at Glendale on June 30, the brigade was in the middle of a fierce battle. His brigade lost 1,400 men and Meade was shot in the right arm and through the back. He was sent home to Philadelphia to recuperate. Meade resumed command of his brigade in time for the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confederate ...

, then assigned to Major General Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell (October 15, 1818 – May 4, 1885) was an American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War. In 1862, he was given command of the ...

's corps of the Army of Virginia. His brigade made a heroic stand on Henry House Hill to protect the rear of the retreating Union Army.

Maryland campaign

The division's commander John F. Reynolds was sent to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, to train militia units and Meade assumed temporary division command at theBattle of South Mountain

The Battle of South Mountain, known in several early Southern United States, Southern accounts as the Battle of Boonsboro Gap, was fought on September 14, 1862, as part of the Maryland campaign of the American Civil War. Three pitched battles ...

and the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam ( ), also called the Battle of Sharpsburg, particularly in the Southern United States, took place during the American Civil War on September 17, 1862, between Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virgi ...

. Under Meade's command, the division successfully attacked and captured a strategic position on high ground near Turner's Gap held by Robert E. Rodes

Robert Emmett (or Emmet) Rodes (March 29, 1829 – September 19, 1864) was a Confederate general in the American Civil War, and the first of Robert E. Lee's divisional commanders not trained at West Point. His division led Stonewall Jackson ...

' troops which forced the withdrawal of other Confederate troops. When Meade's troops stormed the heights, the corps commander Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

, exclaimed, "Look at Meade! Why, with troops like those, led in that way, I can win anything!"

On September 17, 1862, at Antietam, Meade assumed temporary command of the I Corps and oversaw fierce combat after Hooker was wounded and requested Meade replace him. On September 29, 1862, Reynolds returned from his service in Harrisburg. Reynolds assumed command of the I Corps and Meade assumed command of the Third Division.

Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville

On November 5, 1862,

On November 5, 1862, Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Everts Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the American Civil War and a three-time Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successfu ...

replaced McClellan as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Burnside gave command of the I Corps to Reynolds which frustrated Meade as he had more combat experience than Reynolds.

Meade was promoted to major general of the Pennsylvania Reserves on November 29, 1862, and given command of a division in the "Left Grand Division" under William B. Franklin. During the Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat between the Union Army, Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Major general ( ...

, Meade's division made the only breakthrough of the Confederate lines, spearheading through a gap in Lt. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's corps at the southern end of the battlefield. However, his attack was not reinforced, which resulted in the loss of much of his division. He led the Center Grand Division through the Mud March and stationed his troops on the banks of the Rappahanock.

On December 22, 1862, Meade replaced Daniel Butterfield

Daniel Adams Butterfield (October 31, 1831 – July 17, 1901) was a New York businessman, a Union general in the American Civil War, and Assistant Treasurer of the United States.

After working for American Express, co-founded by his father ...

in command of the V Corps which he led in the Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the American Civil War (1861–1865), and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville campaign.

Confederate General Robert E. Lee's risky decision to divide h ...

. On January 26, 1863, Joseph Hooker assumed command of the Army of the Potomac. Hooker had grand plans for the Battle of Chancellorsville, but was unsuccessful in execution, allowing the Confederates to seize the initiative. After the battle, Meade wrote to his wife that, "General Hooker has disappointed all his friends by failing to show his fighting qualities in a pinch."

Meade's corps was left in reserve for most of the battle, contributing to the Union defeat. Meade was among Hooker's commanders who argued to advance against Lee, but Hooker chose to retreat. Meade learned afterward that Hooker misrepresented his position on the advance and confronted him. All of Hooker's commanders supported Meade's position except Dan Sickles.

Gettysburg campaign

In June 1863, Lee took the initiative and moved hisArmy of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was a field army of the Confederate States Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most often arrayed agains ...

into Maryland and Pennsylvania. Hooker responded rapidly and positioned the Army of the Potomac between Lee's army and Washington D.C. However, the relationship between the Lincoln administration and Hooker had deteriorated due to Hooker's poor performance at Chancellorsville. Hooker requested additional troops be assigned from Harper's Ferry to assist in the pursuit of Lee in the Gettysburg Campaign. When Lincoln and General in Chief Henry Halleck

Henry Wager Halleck (January 16, 1815 – January 9, 1872) was a senior United States Army officer, scholar, and lawyer. A noted expert in military studies, he was known by a nickname that became derogatory: "Old Brains". He was an important part ...

refused, Hooker resigned in protest.

Command of the Army of the Potomac

In the early morning hours of June 28, 1863, a messenger fromPresident

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

arrived to inform Meade of his appointment as Hooker's replacement. Upon being woken up, he'd assumed that army politics had caught up to him and that he was under arrest, only to find that he'd been given leadership of the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the primary field army of the Union army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the Battle of ...

.

He had not actively sought command and was not the president's first choice. John F. Reynolds, one of four major generals who outranked Meade in the Army of the Potomac, had earlier turned down the president's suggestion that he take over. Three corps commanders, John Sedgwick

John Sedgwick (September 13, 1813 – May 9, 1864) was an American military officer who served as a Union Army general during the American Civil War.

He was wounded three times at the Battle of Antietam while leading his division in an unsucces ...

, Henry Slocum, and Darius N. Couch

Darius Nash Couch (July 23, 1822 – February 12, 1897) was an American soldier, businessman, and naturalist. He served as a career United States Army, U.S. Army officer during the Mexican–American War, the Second Seminole War, and as a general ...

, recommended Meade for command of the army and agreed to serve under him despite outranking him. While his colleagues were excited for the change in leadership, the soldiers in the Army of Potomac were uncertain of Meade since his modesty, lack of the theatrical and scholarly demeanor did not match their expectations for a General.

Meade assumed command of the Army of the Potomac on June 28, 1863. In a letter to his wife, Meade wrote that command of the army was "more likely to destroy one's reputation then to add to it."

Battle of Gettysburg

Meade rushed the remainder of his army to Gettysburg and deployed his forces for a defensive battle. Meade was only four days into his leadership of the Army of the Potomac and informed his corps commanders that he would provide quick decisions and entrust them with the authority to carry out those orders the best way they saw fit. He also made it clear that he was counting on the corps commanders to provide him with sound advice on strategy.

Since Meade was new to high command, he did not remain in headquarters but constantly moved about the battlefield, issuing orders and ensuring that they were followed. Meade gave orders for the Army of the Potomac to move forward in a broad front to prevent Lee from flanking them and threatening the cities of Baltimore and Washington D.C. He also issued a conditional plan for a retreat to Pipe Creek, Maryland in case things went poorly for the Union. By 6 pm on the evening of July 1, 1863, Meade sent a telegram to Washington informing them of his decision to concentrate forces and make a stand at Gettysburg.

On July 2, 1863, Meade continued to monitor and maintain the placement of the troops. He was outraged when he discovered that Daniel Sickles had moved his Corps one mile forward to high ground without Meade's permission and left a gap in the line which threatened Sickles' right flank. Meade recognized that

Meade rushed the remainder of his army to Gettysburg and deployed his forces for a defensive battle. Meade was only four days into his leadership of the Army of the Potomac and informed his corps commanders that he would provide quick decisions and entrust them with the authority to carry out those orders the best way they saw fit. He also made it clear that he was counting on the corps commanders to provide him with sound advice on strategy.

Since Meade was new to high command, he did not remain in headquarters but constantly moved about the battlefield, issuing orders and ensuring that they were followed. Meade gave orders for the Army of the Potomac to move forward in a broad front to prevent Lee from flanking them and threatening the cities of Baltimore and Washington D.C. He also issued a conditional plan for a retreat to Pipe Creek, Maryland in case things went poorly for the Union. By 6 pm on the evening of July 1, 1863, Meade sent a telegram to Washington informing them of his decision to concentrate forces and make a stand at Gettysburg.

On July 2, 1863, Meade continued to monitor and maintain the placement of the troops. He was outraged when he discovered that Daniel Sickles had moved his Corps one mile forward to high ground without Meade's permission and left a gap in the line which threatened Sickles' right flank. Meade recognized that Little Round Top

Little Round Top is the smaller of two rocky hills south of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania—the companion to the adjacent, taller hill named Big Round Top. It was the site of an unsuccessful assault by Confederate troops against the Union left ...

was critical to maintaining the left flank. He sent chief engineer Gouverneur Warren to determine the status of the hill and quickly issued orders for the V Corps to occupy it when it was discovered empty. Meade continued to reinforce the troops defending Little Round Top from Longstreet's advance and suffered the near destruction of thirteen brigades. One questionable decision Meade made that day was to order Slocum's XII Corps to move from Culp's Hill

Culp's Hill,. The modern U.S. Geographic Names System refers to "Culps Hill". which is about south of the center of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, played a prominent role in the Battle of Gettysburg. It consists of two rounded peaks, separated b ...

to the left flank which allowed Confederate troops to temporarily capture a portion of it.

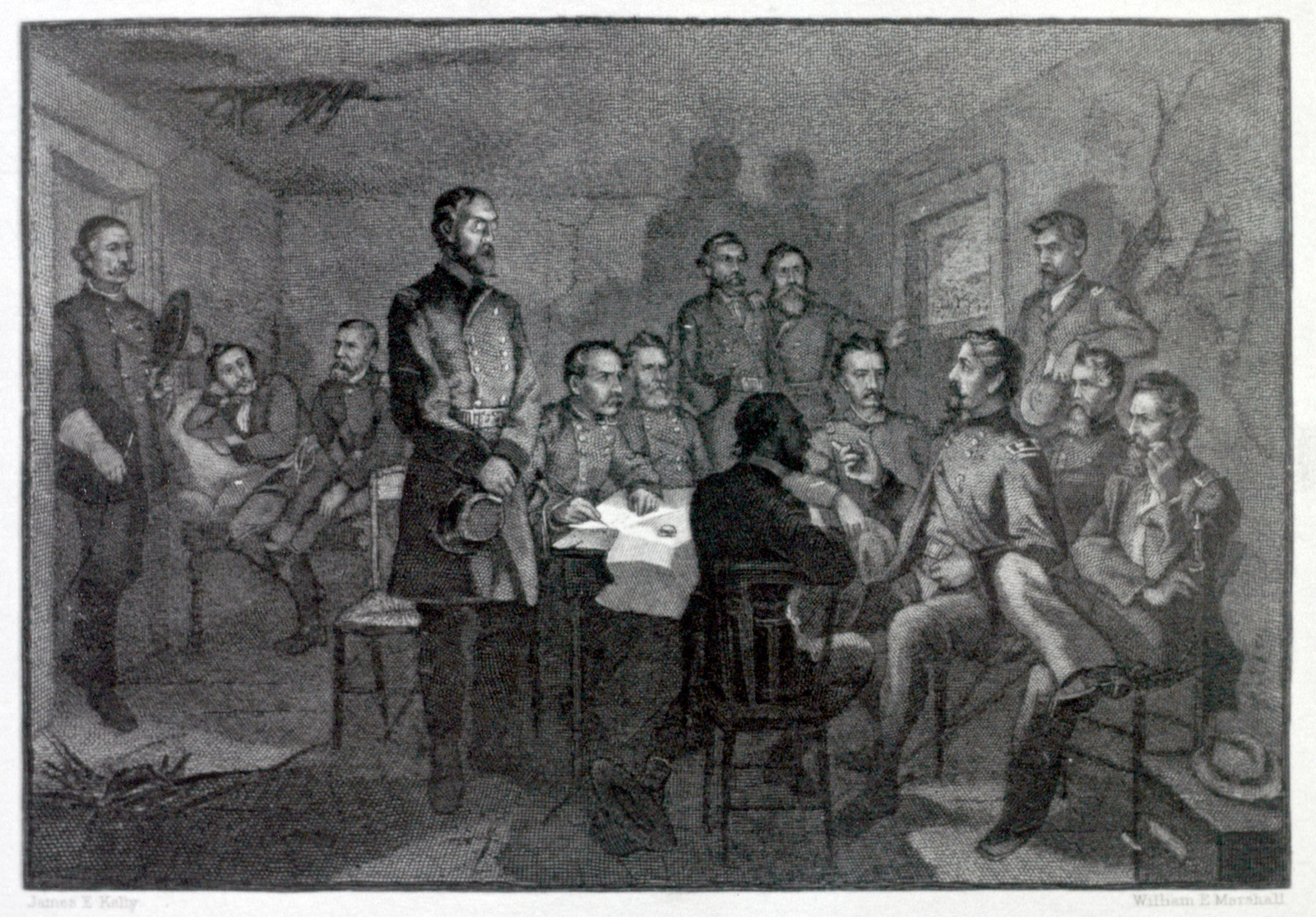

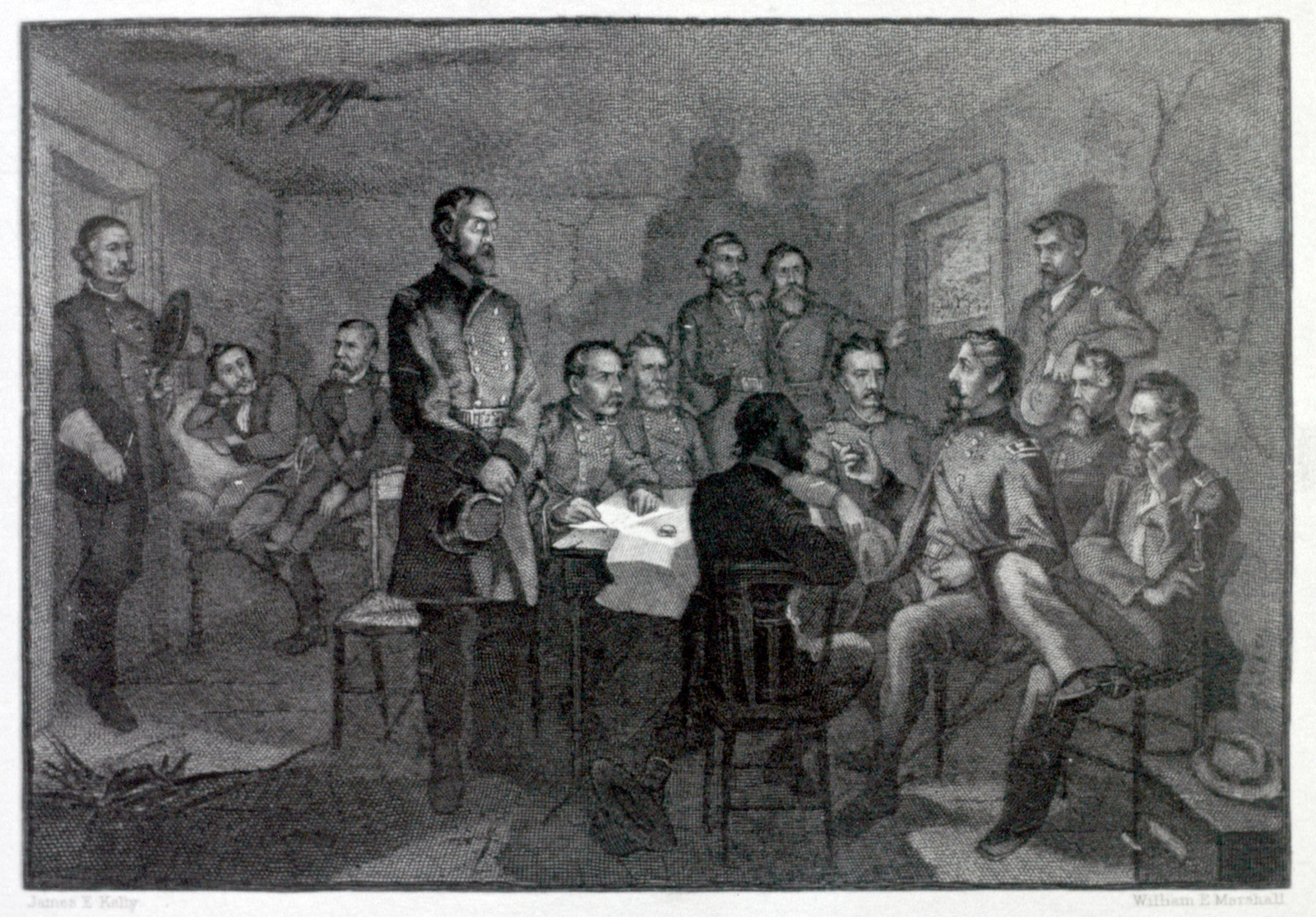

On the evening of July 2, 1863, Meade called a "council of war" consisting of his top generals. The council reviewed the battle to date and agreed to keep fighting in a defensive position.

On July 3, 1863, Meade gave orders for the XII Corps and XI Corps to retake the lost portion of Culp's Hill and personally rode the length of the lines from Cemetery Ridge to Little Round Top to inspect the troops. His headquarters were in the Leister House directly behind Cemetery Ridge which exposed it to the 150-gun cannonade which began at 1 pm. The house came under direct fire from incorrectly targeted Confederate guns; Butterfield was wounded and sixteen horses tied up in front of the house were killed. Meade did not want to vacate the headquarters and make it more difficult for messages to find him, but the situation became too dire and the house was evacuated.

During the three days, Meade made excellent use of capable subordinates, such as Maj. Gens. John F. Reynolds and Winfield S. Hancock, to whom he delegated great responsibilities. He reacted swiftly to fierce assaults on his line's left and right which culminated in Lee's disastrous assault on the center, known as

On July 3, 1863, Meade gave orders for the XII Corps and XI Corps to retake the lost portion of Culp's Hill and personally rode the length of the lines from Cemetery Ridge to Little Round Top to inspect the troops. His headquarters were in the Leister House directly behind Cemetery Ridge which exposed it to the 150-gun cannonade which began at 1 pm. The house came under direct fire from incorrectly targeted Confederate guns; Butterfield was wounded and sixteen horses tied up in front of the house were killed. Meade did not want to vacate the headquarters and make it more difficult for messages to find him, but the situation became too dire and the house was evacuated.

During the three days, Meade made excellent use of capable subordinates, such as Maj. Gens. John F. Reynolds and Winfield S. Hancock, to whom he delegated great responsibilities. He reacted swiftly to fierce assaults on his line's left and right which culminated in Lee's disastrous assault on the center, known as Pickett's Charge

Pickett's Charge was an infantry assault on July 3, 1863, during the Battle of Gettysburg. It was ordered by Confederate General Robert E. Lee as part of his plan to break through Union lines and achieve a decisive victory in the North. T ...

.

By the end of three days of fighting, the Army of the Potomac's 60,000 troops and 30,000 horses had not been fed in three days and were weary from fighting. On the evening of July 4, 1863, Meade held a second council of war with his top generals, minus Hancock and Gibbon, who were absent due to duty and injury. The council reviewed the status of the army and debated staying in place at Gettysburg versus chasing the retreating Army of Northern Virginia. The council voted to remain in place for one day to allow for rest and recovery and then set out after Lee's army. Meade sent a message to Halleck stating, "I make a reconnaissance to-morrow, to ascertain what the intention of the enemy is … should the enemy retreat, I shall pursue him on his flanks."

Lee's retreat

On July 4, it was observed that theConfederate Army

The Confederate States Army (CSA), also called the Confederate army or the Southern army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fi ...

was forming a new line near the nearby mountains after pulling back their left flank, but by July 5 it was clear that they were making a retreat, leaving Meade and his men to tend to the wounded and fallen soldiers until July 6, when Meade ordered his men to Maryland.

Meade was criticized by President Lincoln and others for not aggressively pursuing the Confederates during their retreat. Meade's perceived caution stemmed from three causes: casualties and exhaustion of the Army of the Potomac which had engaged in forced marches and heavy fighting for a week, heavy general officer casualties that impeded effective command and control, and a desire to guard a hard-won victory against a sudden reversal. Halleck informed Meade of the president's dissatisfaction which infuriated Meade that politicians and non-field-based officers were telling him how to fight the war. He wrote back and offered to resign his command, but Halleck refused the resignation and clarified that his communication was not meant as a rebuke but an incentive to continue the pursuit of Lee's army.

At one point, the Army of Northern Virginia was trapped with its back to the rain-swollen, almost impassable Potomac River

The Potomac River () is in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and flows from the Potomac Highlands in West Virginia to Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography D ...

; however, the Army of Northern Virginia was able to erect strong defensive positions before Meade, whose army had also been weakened by the fighting, could organize an effective attack. Lee knew he had the superior defensive position and hoped that Meade would attack and the resulting Union Army losses would dampen the victory at Gettysburg. By July 14, 1863, Lee's troops built a temporary bridge over the river and retreated into Virginia.

Meade was rewarded for his actions at Gettysburg by a promotion to brigadier general in the regular army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the following:

* a ...

on July 7, 1863, and the Thanks of Congress

The Thanks of Congress is a series of formal resolutions passed by the United States Congress originally to extend the government's formal thanks for significant victories or impressive actions by United States, American military commanders and th ...

, which commended Meade "... and the officers and soldiers of the Army of the Potomac, for the skill and heroic valor which at Gettysburg repulsed, defeated, and drove back, broken and dispirited, beyond the Rappahannock, the veteran army of the rebellion."

Meade wrote the following to his wife after meeting President Lincoln:

Bristoe and Mine Run campaign

During the fall of 1863, the Army of the Potomac was weakened by the transfer of the XI and XII Corps to the Western Theater. Meade felt pressure from Halleck and the Lincoln administration to pursue Lee into Virginia but he was cautious due to a misperception that Lee's Army was 70,000 in size when the reality was they were only 55,000 compared to the Army of the Potomac at 76,000. Many of the Union troop replacements for the losses suffered at Gettysburg were new recruits and it was uncertain how they would perform in combat.

Lee petitioned Jefferson Davis to allow him to take the offensive against the cautious Meade which would also prevent further Union troops being sent to the Western Theater to support William Rosencrans at the Battle of Chickamauga.

During the fall of 1863, the Army of the Potomac was weakened by the transfer of the XI and XII Corps to the Western Theater. Meade felt pressure from Halleck and the Lincoln administration to pursue Lee into Virginia but he was cautious due to a misperception that Lee's Army was 70,000 in size when the reality was they were only 55,000 compared to the Army of the Potomac at 76,000. Many of the Union troop replacements for the losses suffered at Gettysburg were new recruits and it was uncertain how they would perform in combat.

Lee petitioned Jefferson Davis to allow him to take the offensive against the cautious Meade which would also prevent further Union troops being sent to the Western Theater to support William Rosencrans at the Battle of Chickamauga.

The Army of the Potomac was stationed along the north bank of the Rapidan River and Meade made his headquarters in

The Army of the Potomac was stationed along the north bank of the Rapidan River and Meade made his headquarters in Culpeper, Virginia

Culpeper (formerly Culpeper Courthouse, earlier Fairfax) is an incorporated town in Culpeper County, Virginia, United States. It is the county seat and part of the Washington–Baltimore–Arlington, DC–MD–VA–WV–PA Combined Statistical ...

. In the Bristoe Campaign, Lee attempted to flank the Army of the Potomac and force Meade to move north of the Rappahannock River. The Union forces had deciphered the Confederate semaphore

Semaphore (; ) is the use of an apparatus to create a visual signal transmitted over distance. A semaphore can be performed with devices including: fire, lights, flags, sunlight, and moving arms. Semaphores can be used for telegraphy when arra ...

code. This along with spies and scouts gave Meade advance notice of Lee's movements. As Lee's troops moved north to the west of the Army of the Potomac, Meade abandoned his headquarters at Culpeper and gave orders for his troops to move north to intercept Lee. Meade successfully outmaneuvered Lee in the campaign and gained a small victory. Lee reported that his plans failed due to the quickness of Meade's redeployment of resources. However, Meade's inability to stop Lee from approaching the outskirts of Washington prompted Lincoln to look for another commander of the Army of the Potomac.

In late November 1863, Meade planned one last offensive against Lee before winter weather limited troop movement. In the Mine Run Campaign

The Battle of Mine Run, also known as Payne's Farm, or New Hope Church, or the Mine Run campaign (November 27 – December 2, 1863), was conducted in Orange County, Virginia, in the American Civil War.

An unsuccessful attempt of the Union ...

, Meade attempted to attack the right flank of the Army of Northern Virginia south of the Rapidan River but the maneuver failed due to the poor performance of William H. French. There was heavy skirmishing but a full attack never occurred. Meade determined that the Confederate forces were too strong and was convinced by Warren that an attack would have been suicidal. Meade held a council of war which concluded to withdraw across the Rapidan River during the night of December 1, 1863.

Overland campaign

1864 was an election year and Lincoln understood that the fate of his reelection lay in the Union Army success against the Confederates. Lt. Gen.Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

, fresh off his success in the Western Theater, was appointed commander of all Union armies in March 1864. In his meeting with Lincoln, Grant was told he could select who he wanted to lead the Army of the Potomac. Edwin M. Stanton, the Secretary of War told Grant, "You will find a very weak, irresolute man there and my advice to you is to replace him at once."

Meade offered to resign and stated the task at hand was of such importance that he would not stand in the way of Grant choosing the right man for the job and offered to serve wherever placed. Grant assured Meade he had no intentions of replacing him. Grant later wrote that this incident gave him a more favorable opinion of Meade than the great victory at Gettysburg. Grant knew that Meade disapproved of Lincoln's strategy and was unpopular with politicians and the press. Grant was not willing to allow him free command of the Army of the Potomac without direct supervision.

Grant's orders to Meade before the Overland Campaign

The Overland Campaign, also known as Grant's Overland Campaign and the Wilderness Campaign, was a series of battles fought in Virginia during May and June 1864, towards the end of the American Civil War. Lieutenant general (United States), Lt. G ...

were direct and the point. He stated "Lee's army will be your objective point. Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also." On May 4, 1864, the Army of the Potomac left its winter encampment and crossed the Rapidan River. Meade and Grant both believed that Lee would retreat to the North Anna River or to Mine Run. Lee had received intelligence about the movements of the Army of the Potomac and countered with a move to the East and met the Union Army at the Wilderness

Wilderness or wildlands (usually in the plurale tantum, plural) are Earth, Earth's natural environments that have not been significantly modified by human impact on the environment, human activity, or any urbanization, nonurbanized land not u ...

. Meade ordered Warren to attack with his whole Corps and had Hancock reinforce with his II Corps. Meade ordered additional Union troops to join the battle but they struggled to maintain formation and communicate with each other in the thick woods of the Wilderness. After three days of brutal fighting and the loss of 17,000 men, the Union Army called it a draw and Meade and Grant moved with their forces south toward Spotsylvania Court House to place the Union Army between Lee's forces and Richmond in the hopes of drawing them out to open field combat.

The Union Army moved ponderously slowly toward their new positions and Meade lashed out at Maj. Gen.

The Union Army moved ponderously slowly toward their new positions and Meade lashed out at Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan

Philip Henry Sheridan (March 6, 1831 – August 5, 1888) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close association with General-i ...

and his cavalry corps blaming them for not clearing the road and not informing Meade of the enemy's movements. Grant had brought Sheridan with him from the Western Theater and he found the Army of the Potomac's cavalry corps run down and in poor discipline. Meade and Sheridan clashed over the use of cavalry since the Army of the Potomac had historically used cavalry as couriers, scouting and headquarters guards. Sheridan told Meade that he could "whip Stuart" if Meade let him. Meade reported the conversation to Grant thinking he would reprimand the insubordinate Sheridan, but he replied, "Well, he generally knows what he is talking about. Let him start right out and do it." Meade deferred to Grant's judgment and issued orders to Sheridan to "proceed against the enemy's cavalry" and from May 9 through May 24, sent him on a raid toward Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, a city in the United States

* Richmond, London, a town in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, England

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town ...

, directly challenging the Confederate cavalry. Sheridan's cavalry had great success, they broke up the Confederate supply lines, liberated hundreds of Union prisoners, mortally wounded Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart and threatened the city of Richmond. However, his departure left the Union Army blind to enemy movements.

Grant made his headquarters with Meade for the remainder of the war, which caused Meade to chafe at the close supervision he received. A newspaper reported the Army of the Potomac was, "directed by Grant, commanded by Meade, and led by Hancock, Sedgwick and Warren." Following an incident in June 1864, in which Meade disciplined reporter Edward Cropsey from ''The Philadelphia Inquirer

''The Philadelphia Inquirer'', often referred to simply as ''The Inquirer'', is a daily newspaper headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Founded on June 1, 1829, ''The Philadelphia Inquirer'' is the third-longest continuously operating da ...

'' newspaper for an unfavorable article, all of the press assigned to his army agreed to mention Meade only in conjunction with setbacks. Meade apparently knew nothing of this arrangement, and the reporters giving all of the credit to Grant angered Meade.

Additional differences caused further friction between Grant and Meade. Waging a war of attrition in the Overland Campaign against Lee, Grant was willing to suffer previously unacceptable losses with the knowledge that the Union Army had replacement soldiers available, whereas the Confederates did not. Meade was opposed to Grant's recommendations to directly attack fortified Confederate positions which resulted in huge losses of Union soldiers. Grant became frustrated with Meade's cautious approach and despite his initial promise to allow Meade latitude in his command, Grant began to override Meade and order the tactical deployment of the Army of the Potomac.

Meade became frustrated with his lack of autonomy and his performance as a military leader suffered. During the Battle of Cold Harbor

The Battle of Cold Harbor was fought during the American Civil War near Mechanicsville, Virginia, from May 31 to June 12, 1864, with the most significant fighting occurring on June 3. It was one of the final battles of Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses ...

, Meade inadequately coordinated the disastrous frontal assault. However, Meade took some satisfaction that Grant's overconfidence at the start of the campaign against Lee had been reduced after the brutal confrontation of the Overland Campaign and stated, "I think Grant has had his eyes opened, and is willing to admit now that Virginia and Lee's army is not Tennessee and raxtonBragg's army."

After the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House

The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, sometimes more simply referred to as the Battle of Spotsylvania (or the 19th-century spelling Spottsylvania), was the second major battle in Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and Maj. Gen. George G. Meade's 18 ...

, Grant requested that Meade be promoted to major general of the regular army. In a telegram to Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Edwin Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as U.S. Secretary of War, U.S. secretary of war under the Lincoln Administration during most of the American Civil War. Stanton's manag ...

on May 13, 1864, Grant stated that "Meade has more than met my most sanguine expectations. He and illiam T.Sherman are the fittest officers for large commands I have come in contact with." Meade felt slighted that his promotion was processed after that of Sherman and Sheridan, the latter his subordinate. The U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and House have the authority under Article One of the ...

confirmed Sherman and Sheridan on January 13, 1865, Meade on February 1. Subsequently, Sheridan was promoted to lieutenant general over Meade on March 4, 1869, after Grant became president and Sherman became the commanding general of the U.S. Army. However, his date of rank meant that he was outranked at the end of the war only by Grant, Halleck, and Sherman.

Richmond-Petersburg campaign

Meade and the Army of the Potomac crossed the James River to attack the strategic supply route centered on Petersburg, Virginia. They probed the defenses of the city and Meade wrote, "We find the enemy, as usual, in a very strong position, defended by earthworks, and it looks very much as if we will have to go through a siege of Petersburg before entering on a siege of Richmond." An opportunity opened up to lead the Army of the Shenandoah, to protect Washington D.C. against the raids ofJubal Early

Jubal Anderson Early (November 3, 1816 – March 2, 1894) was an American lawyer, politician and military officer who served in the Confederate States Army during the Civil War. Trained at the United States Military Academy, Early resigned his ...

. Meade wanted the role to free himself from under Grant; however, the position was given to Sheridan. When Meade asked Grant why it did not go to himself, the more experienced officer, Grant stated that Lincoln did not want to take Meade away from the Army of the Potomac and imply that his leadership was substandard.

During the Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the siege of Petersburg, it was not a c ...

, he approved the plan of Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Everts Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the American Civil War and a three-time Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successfu ...

to plant explosives in a mine shaft dug underneath the Confederate line east of Petersburg, but at the last minute he changed Burnside's plan to lead the attack with a well-trained African-American division that was highly drilled just for this action, instructing him to take a politically less risky course and substitute an untrained and poorly led white division. The resulting Battle of the Crater was one of the great fiascoes of the war.

Although he fought during the Appomattox Campaign, Grant and Sheridan received most of the credit and Meade was not present when Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House.

With the war over, the Army of the Potomac was disbanded on June 28, 1865, and Meade's command of it ended.

Although he fought during the Appomattox Campaign, Grant and Sheridan received most of the credit and Meade was not present when Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House.

With the war over, the Army of the Potomac was disbanded on June 28, 1865, and Meade's command of it ended.

Political rivalries

Many of the political rivalries in the Army of the Potomac stemmed from opposition to the politically conservative, full-time officers from West Point. Meade was a Douglas Democrat and saw the preservation of the Union as the war's true goal and only opposed slavery as it threatened to tear the Union apart. He was a supporter of McClellan, the previously removed commander of the Army of the Potomac, and was politically aligned with him. Other McClellan loyalists who advocated a more moderate prosecution of the war, such as Charles P. Stone and Fitz John Porter, were arrested and court-martialed. When Meade was awakened in the middle of the night and informed that he was given command of the Army of the Potomac, he later wrote to his wife that he assumed that Army politics had caught up with him and he was being arrested. Meade's short temper earned him notoriety, and while he was respected by most of his peers and trusted by the men in his army, he did not inspire them. While Meade could be sociable, intellectual and courteous in normal times, the stress of war made him prickly and abrasive and earned him the nickname "Old Snapping Turtle". He was prone to bouts of anger and rashness and was paranoid about political enemies coming after him. His political enemies includedDaniel Butterfield

Daniel Adams Butterfield (October 31, 1831 – July 17, 1901) was a New York businessman, a Union general in the American Civil War, and Assistant Treasurer of the United States.

After working for American Express, co-founded by his father ...

, Abner Doubleday, Joseph Hooker, Alfred Pleasonton and Daniel Sickles

Daniel Edgar Sickles (October 20, 1819May 3, 1914) was an American politician, American Civil War , Civil War veteran, and diplomat. He served in the United States House of Representatives , U.S. House of Representatives both before and after t ...

. Sickles had developed a personal vendetta against Meade because of Sickles's allegiance to Hooker, whom Meade had replaced, and because of controversial disagreements at Gettysburg. Sickles had either mistakenly or deliberately disregarded Meade's orders about placing his III Corps in the defensive line, which led to that corps' destruction and placed the entire army at risk on the second day of battle.

Halleck, Meade's direct supervisor prior to Grant, was openly critical of Meade. Both Halleck and Lincoln pressured Meade to destroy Lee's army but gave no specifics as to how it should be done. Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans were a political faction within the Republican Party originating from the party's founding in 1854—some six years before the Civil War—until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reconstruction. They ca ...

, some of whom like Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was an American politician and lawyer who served as a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, being one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Histo ...

were former Know Nothing

The American Party, known as the Native American Party before 1855 and colloquially referred to as the Know Nothings, or the Know Nothing Party, was an Old Stock Americans, Old Stock Nativism in United States politics, nativist political movem ...

s and hostile to Irish Catholics like Meade's family, in the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War suspected that Meade was a Copperhead and tried in vain to relieve him from command. Sickles testified to the committee that Meade wanted to retreat his position at Gettysburg before the fighting started. The joint committee did not remove Meade from command of the Army of the Potomac.

Reconstruction

In July 1865, Meade assumed command of the Military Division of the Atlantic headquartered in Philadelphia. On January 6, 1868, he took command of theThird Military District

The Third Military District of the U.S. Army was one of five temporary administrative units of the U.S. War Department that existed in the American South. The district was stipulated by the Reconstruction Acts during the Reconstruction period fo ...

in Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georg ...

. In January 1868, he assumed command of the Department of the South. The formation of the state governments of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina and South Carolina for reentry into the United States was completed under his direct supervision. When the Governor of Georgia refused to accept the Reconstruction Acts of Congress, Meade replaced him with General Thomas H. Ruger.

After the Camilla massacre in September 1868, caused by anger from white southerners over blacks gaining the right to vote in the 1868 Georgia state constitution, Meade investigated the event and decided to leave the punishment in the hands of civil authorities. Meade returned to command of the Military Division of the Atlantic in Philadelphia.

In 1869, following Grant's inauguration as president and William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a General officer, general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), earning recognit ...

's assignment to general-in-chief

General-in-chief has been a military rank or title in various armed forces around the world.

France

In France, general-in-chief () was first an informal title for the lieutenant-general commanding over other lieutenant-generals, or even for some ...

, Sheridan was promoted over Meade to lieutenant general. Meade effectively served in semi-retirement as the commander of the Military Division of the Atlantic from his home in Philadelphia.

Personal life

On December 31, 1840 (his birthday), he married Margaretta Sergeant, daughter of John Sergeant, running mate ofHenry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

in the 1832 presidential election. They had seven children together: John Sergeant Meade, George Meade, Margaret Butler Meade, Spencer Meade, Sarah Wise Meade, Henrietta Meade, and William Meade.

His notable descendants include:

* George Meade Easby, great-grandson

* Happy Rockefeller, great-great-granddaughter

*Matthew Fox

Matthew Chandler Fox (born July 14, 1966) is an American actor. He is known for his roles as Charlie Salinger on '' Party of Five'' (1994–2000) and Jack Shephard on the drama series '' Lost'' (2004–2010), the latter of which earned him G ...

, great-great-great-grandson

Later life and death

Meade was presented with a gold medal from the

Meade was presented with a gold medal from the Union League of Philadelphia

The Union League of Philadelphia is a private club founded in 1862 by the Old Philadelphians as a patriotic society to support the policies of Abraham Lincoln. As of 2022, the club has over 4,000 members. Its main building was built in 1865 a ...

in recognition for his success at Gettysburg.

Meade was a commissioner of Fairmount Park

Fairmount Park is the largest municipal park in Philadelphia and the historic name for a group of parks located throughout the city. Fairmount Park consists of two park sections named East Park and West Park, divided by the Schuylkill River, w ...

in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

from 1866 until his death. The city of Philadelphia gave Meade's wife a house at 1836 Delancey Place in which he lived also. The building still has the name "Meade" over the door, but is now used as apartments.

Meade received an honorary doctorate in law (LL.D.) from Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

, and his scientific achievements were recognized by various institutions, including the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

and the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences.

Having long suffered from complications caused by his war wounds, Meade died on November 6, 1872, in the house at 1836 Delancey Place, from pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

. He was buried at Laurel Hill Cemetery

Laurel Hill Cemetery, also called Laurel Hill East to distinguish it from the affiliated West Laurel Hill Cemetery in Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania, Bala Cynwyd, is a historic rural cemetery in the East Falls, Philadelphia, East Falls neighborhood ...

.

Legacy

Meade has been memorialized with several statues including an equestrian statue atGettysburg National Military Park

The Gettysburg National Military Park protects and interprets the landscape of the Battle of Gettysburg, fought over three days between July 1 and July 3, 1863, during the American Civil War. The park, in the Gettysburg, Pennsylvania area, is m ...

by Henry Kirke Bush-Brown; the George Gordon Meade Memorial statue by Charles Grafly, in front of the E. Barrett Prettyman United States Courthouse in Washington, D.C.; an equestrian statue

An equestrian statue is a statue of a rider mounted on a horse, from the Latin ''eques'', meaning 'knight', deriving from ''equus'', meaning 'horse'. A statue of a riderless horse is strictly an equine statue. A full-sized equestrian statue is a ...

by Alexander Milne Calder

Alexander Milne Calder (August 23, 1846 – June 4, 1923) (MILL-nee) was a Scottish American sculptor best known for the architectural sculpture of Philadelphia City Hall. Both his son, Alexander Stirling Calder, and grandson, Alexander Calder ...

; and one by Daniel Chester French

Daniel Chester French (April 20, 1850 – October 7, 1931) was an American sculpture, sculptor in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His works include ''The Minute Man'', an 1874 statue in Concord, Massachusetts, and his Statue of Abr ...

atop the Smith Memorial Arch, both in Fairmount Park

Fairmount Park is the largest municipal park in Philadelphia and the historic name for a group of parks located throughout the city. Fairmount Park consists of two park sections named East Park and West Park, divided by the Schuylkill River, w ...

in Philadelphia. A bronze bust of Meade by Boris Blai was placed at Barnegat Lighthouse in 1957.

The United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

's Fort George G. Meade

Fort George G. Meade is a United States Army installation located in Maryland, that includes the Defense Information School, the Defense Media Activity, the United States Army Field Band, and the headquarters of United States Cyber Command, th ...

in Fort Meade, Maryland

Fort Meade is a census-designated place (CDP) in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, United States. The population was 9,324 at the 2020 census. It is the home to the National Security Agency, Central Security Service, United States Cyber Command an ...

, is named for him, as are Meade County, Kansas

Meade County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kansas. Its county seat and largest city is Meade. As of the 2020 census, the county population was 4,055. The county was created in 1873 and named in honor of George Meade, a Union ge ...

; Fort Meade, Florida; Fort Meade National Cemetery; and Meade County, South Dakota

Meade County is a county in the U.S. state of South Dakota. As of the 2020 census, the population was 29,852, making it the 6th most populous county in South Dakota. Its county seat is Sturgis. The county was created in 1889 and named for Fo ...

. The Grand Army of the Republic

The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) was a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army (United States Army), Union Navy (United States Navy, U.S. Navy), and the United States Marine Corps, Marines who served in the American Ci ...

Meade Post #1 founded in Philadelphia in 1866 was named in his honor.

The General Meade Society was created to "promote and preserve the memory of Union Major General George Meade". Members gather in Laurel Hill Cemetery on December 31 to recognize his birthday. The Old Baldy Civil War Round Table in Philadelphia is named in honor of Meade's horse during the war.

The one-thousand-dollar Treasury Note

United States Treasury securities, also called Treasuries or Treasurys, are government bond, government debt instruments issued by the United States Department of the Treasury to finance government spending as a supplement to taxation. Sinc ...

s, also called Coin notes, of the Series 1890 and 1891, feature portraits of Meade on the obverse. The 1890 Series note is called the Grand Watermelon Note by collectors, because the large zeroes on the reverse resemble the pattern on a watermelon.