General Qasim on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Abdul-Karim Qasim Muhammad Bakr al-Fadhli al-Zubaidi ( ar, عبد الكريم قاسم ' ; 21 November 1914 – 9 February 1963) was an Iraqi military officer and

Abd al-Karim's father, Qasim Muhammed Bakr Al-Fadhli Al-Zubaidi was a farmer from southern

Abd al-Karim's father, Qasim Muhammed Bakr Al-Fadhli Al-Zubaidi was a farmer from southern

nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

who came to power in 1958 when the Iraqi monarchy

Iraqi or Iraqis (in plural) means from Iraq, a country in the Middle East, and may refer to:

* Iraqi people or Iraqis, people from Iraq or of Iraqi descent

* A citizen of Iraq, see demographics of Iraq

* Iraqi or Araghi ( fa, عراقی), someone o ...

was overthrown during the 14 July Revolution

The 14 July Revolution, also known as the 1958 Iraqi coup d'état, took place on 14 July 1958 in Iraq, and resulted in the overthrow of the Hashemite monarchy in Iraq that had been established by King Faisal I in 1921 under the auspices of the B ...

. He ruled the country as the prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

until his downfall and execution during the 1963 Ramadan Revolution

The Ramadan Revolution, also referred to as the 8 February Revolution and the February 1963 coup d'état in Iraq, was a military coup by the Ba'ath Party's Iraqi-wing which overthrew the Prime Minister of Iraq, Abd al-Karim Qasim in 1963. It t ...

.

During his rule, Qasim was popularly known as ''al-zaʿīm'' (الزعيم), or "The Leader".

Early life and career

Abd al-Karim's father, Qasim Muhammed Bakr Al-Fadhli Al-Zubaidi was a farmer from southern

Abd al-Karim's father, Qasim Muhammed Bakr Al-Fadhli Al-Zubaidi was a farmer from southern Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesipho ...

and an Iraqi

Iraqi or Iraqis (in plural) means from Iraq, a country in the Middle East, and may refer to:

* Iraqi people or Iraqis, people from Iraq or of Iraqi descent

* A citizen of Iraq, see demographics of Iraq

* Iraqi or Araghi ( fa, عراقی), someone o ...

Sunni Muslim who died during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fig ...

, shortly after his son's birth. Qasim's mother, Kayfia Hassan Yakub Al-Sakini was a Shia Feyli Kurd Muslim from Baghdad.

Qasim was born in Mahdiyya, a lower-income district of Baghdad on the left side of the river, now known as Karkh

Karkh or Al-Karkh (Arabic: الكرخ) is historically the name of the western half of Baghdad, Iraq, or alternatively, the western shore of the Tigris River as it ran through Baghdad. The eastern shore is known as Al-Rasafa. When Qasim was six, his family moved to Suwayra, a small town near the

On 14 July 1958, Qasim used troop movements planned by the government as an opportunity to seize military control of Baghdad and overthrow the monarchy. The king, several members of the royal family, and their close associates, including Prime Minister

On 14 July 1958, Qasim used troop movements planned by the government as an opportunity to seize military control of Baghdad and overthrow the monarchy. The king, several members of the royal family, and their close associates, including Prime Minister

Qasim assumed office after being elected as Prime Minister shortly after the coup in July 1958. He held this position until he was overthrown in February 1963.

Despite the encouraging tones of the temporary constitution, the new government descended into autocracy with Qasim at its head. The genesis of his elevation to "Sole Leader" began with a schism between Qasim and his fellow conspirator Arif. Despite one of the major goals of the revolution being to join the

Qasim assumed office after being elected as Prime Minister shortly after the coup in July 1958. He held this position until he was overthrown in February 1963.

Despite the encouraging tones of the temporary constitution, the new government descended into autocracy with Qasim at its head. The genesis of his elevation to "Sole Leader" began with a schism between Qasim and his fellow conspirator Arif. Despite one of the major goals of the revolution being to join the  Unlike the bulk of military officers, Qasim did not come from the Arab Sunni north-western towns, nor did he share their enthusiasm for pan-Arabism: he was of mixed Sunni-Shia parentage from south-eastern Iraq. His ability to remain in power depended, therefore, on a skilful balancing of the communists and the pan-Arabists. For most of his tenure, Qasim sought to balance the growing pan-Arab trend in the military.

He lifted a ban on the

Unlike the bulk of military officers, Qasim did not come from the Arab Sunni north-western towns, nor did he share their enthusiasm for pan-Arabism: he was of mixed Sunni-Shia parentage from south-eastern Iraq. His ability to remain in power depended, therefore, on a skilful balancing of the communists and the pan-Arabists. For most of his tenure, Qasim sought to balance the growing pan-Arab trend in the military.

He lifted a ban on the

The new Government declared Kurdistan "one of the two nations of Iraq". During his rule, the Kurdish groups selected

The new Government declared Kurdistan "one of the two nations of Iraq". During his rule, the Kurdish groups selected

Qasim was given a short show trial and was shot soon after. Many of Qasim's Shi'ite supporters believed that he had merely gone into hiding and would appear like the

Qasim was given a short show trial and was shot soon after. Many of Qasim's Shi'ite supporters believed that he had merely gone into hiding and would appear like the

The 1958 Revolution can be considered a watershed in Iraqi politics, not just because of its obvious political implications (e.g. the abolition of monarchy, republicanism, and paving the way for Ba'athist rule) but also because of its domestic reforms. Despite its shortcomings, Qasim's rule helped to implement a number of positive domestic changes that benefited Iraqi society and were widely popular, especially the provision of low-cost housing to the inhabitants of Baghdad's urban slums. While criticising Qasim's "irrational and capricious behaviour" and "extraordinarily quixotic attempt to annex Kuwait in the summer of 1961", actions that raised "serious doubts about his sanity", Marion Farouk–Sluglett and Peter Sluglett conclude that, "Qasim's failings, serious as they were, can scarcely be discussed in the same terms as the venality, savagery and wanton brutality characteristic of the regimes which followed his own". Despite upholding death sentences against those involved in the

The 1958 Revolution can be considered a watershed in Iraqi politics, not just because of its obvious political implications (e.g. the abolition of monarchy, republicanism, and paving the way for Ba'athist rule) but also because of its domestic reforms. Despite its shortcomings, Qasim's rule helped to implement a number of positive domestic changes that benefited Iraqi society and were widely popular, especially the provision of low-cost housing to the inhabitants of Baghdad's urban slums. While criticising Qasim's "irrational and capricious behaviour" and "extraordinarily quixotic attempt to annex Kuwait in the summer of 1961", actions that raised "serious doubts about his sanity", Marion Farouk–Sluglett and Peter Sluglett conclude that, "Qasim's failings, serious as they were, can scarcely be discussed in the same terms as the venality, savagery and wanton brutality characteristic of the regimes which followed his own". Despite upholding death sentences against those involved in the

"Principles of 14th July revolution; a few collections of the epoch-making speeches delivered on some auspicious and historical occasions after the blessed, peaceful and miraculous revolution of July 14, 1958"

Baghdad; Times Press. * Christopher Solomon

60 years after Iraq’s 1958 July 14 Revolution

Gulf International Forum, 9 August 2018 {{DEFAULTSORT:Qasim, Abd Al-Karim Prime ministers of Iraq 20th century in Iraq 1914 births 1963 deaths Iraqi nationalists Leaders who took power by coup Leaders ousted by a coup Executed prime ministers Politicians from Baghdad Iraqi Muslims Iraqi generals Articles containing video clips Executed Iraqi people People executed by Iraq by firing squad 20th-century executions by Iraq Iraqi Military Academy alumni People of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War

Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

, then to Baghdad in 1926. Qasim was an excellent student and entered secondary school on a government scholarship. After graduation in 1931, he attended Shamiyya Elementary School from 22 October 1931 until 3 September 1932, when he was accepted into Military College. In 1934, he graduated as a second lieutenant. Qasim then attended al-Arkan (Iraqi Staff) College and graduated with honours (grade A) in December 1941. In 1951, he completed a senior officers’ course in Devizes

Devizes is a market town and civil parish in Wiltshire, England. It developed around Devizes Castle, an 11th-century Norman castle, and received a charter in 1141. The castle was besieged during the Anarchy, a 12th-century civil war between St ...

, Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershir ...

. Qasim was nicknamed "the snake charmer" by his classmates in Devizes because of his ability to persuade them to undertake improbable courses of action during military exercises.

Militarily, he participated in the suppression of the tribal disturbances in the Middle Euphrates region in 1935, in the Anglo-Iraqi War

The Anglo-Iraqi War was a British-led Allies of World War II, Allied military campaign during the Second World War against the Kingdom of Iraq under Rashid Ali, Rashid Gaylani, who had seized power in the 1941 Iraqi coup d'état, with assista ...

in May 1941 and the Barzani revolt in 1945. Qasim also served during the Iraqi military involvement in the 1948 Arab-Israeli War from May 1948 to June 1949. Toward the latter part of that mission, he commanded a battalion of the First Brigade, which was situated in the Kafr Qassem

Kafr Qasim ( ar, كفر قاسم, he, כַּפְר קָאסִם), also spelled as Kafr Qassem, Kufur Kassem, Kfar Kassem and Kafar Kassem, is a hill-top city in Israel with an Arab population. It is located about east of Tel Aviv, on the Israe ...

area south of Qilqilya

Qalqilya or Qalqiliya ( ar, قلقيلية, Qalqīlyaḧ) is a Palestinian city in the West Bank which serves as the administrative center of the Qalqilya Governorate of the State of Palestine. In the 2007 census, the city had a population of 41,73 ...

. In 1956–57, he served with his brigade at Mafraq

Mafraq ( ar, المفرق ''Al-Mafraq'', local dialects: ''Mafrag'' or ''Mafra''; ) is the capital city of Mafraq Governorate in Jordan, located 80 km to the north from the capital Amman in crossroad to Syria to the north and Iraq to the east ...

in Jordan in the wake of the Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

. By 1957 Qasim had assumed leadership of several opposition groups that had formed in the army.

14 July Revolution

On 14 July 1958, Qasim used troop movements planned by the government as an opportunity to seize military control of Baghdad and overthrow the monarchy. The king, several members of the royal family, and their close associates, including Prime Minister

On 14 July 1958, Qasim used troop movements planned by the government as an opportunity to seize military control of Baghdad and overthrow the monarchy. The king, several members of the royal family, and their close associates, including Prime Minister Nuri as-Said

Nuri Pasha al-Said CH (December 1888 – 15 July 1958) ( ar, نوري السعيد) was an Iraqi politician during the British mandate in Iraq and the Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq. He held various key cabinet positions and served eight terms as ...

, were executed.

The coup was discussed and planned by the Free Officers and Civilians Movement

The Free Officers and Civilians Movement was an Iraqi opposition (pre-2003), Iraqi opposition movement that campaigned against President Saddam Hussein.

It was formed in 1996 from defected Iraqi army officers and led by former Brigadier General Na ...

, which although inspired by the Egypt's eponymous movement, was not as advanced or cohesive. From as early as 1952 the Iraqi Free Officers and Civilians Movement's initial cell was led by Qasim and Colonel Isma'il Arif, before being joined later by an infantry officer serving under Qasim who would later go on to be his closest collaborator, Colonel Abdul Salam Arif. By the time of the coup in 1958, the total number of agents operating on behalf of the Free Officers had risen to around 150 who were all planted as informants or go-betweens in most units and depots of the army.

The coup was triggered when King Hussein

Hussein bin Talal ( ar, الحسين بن طلال, ''Al-Ḥusayn ibn Ṭalāl''; 14 November 1935 – 7 February 1999) was King of Jordan from 11 August 1952 until his death in 1999. As a member of the Hashemite dynasty, the royal family o ...

of Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Ri ...

, fearing that an anti-Western revolt in Lebanon might spread to Jordan, requested Iraqi assistance. Instead of moving towards Jordan, however, Colonel Arif led a battalion into Baghdad and immediately proclaimed a new republic and the end of the old regime.

King Faisal II ordered the Royal Guard to offer no resistance, and surrendered to the coup forces. Around 8 am, Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Abdul Sattar Sabaa Al-Ibousi, leading the revolutionary assault group at the Rihab Palace, which was still the principal royal residence in central Baghdad, ordered the King, Crown Prince

A crown prince or hereditary prince is the heir apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The female form of the title is crown princess, which may refer either to an heiress apparent or, especially in earlier times, to the wife ...

'Abd al-Ilah

'Abd al-Ilah of Hejaz, ( ar, عبد الإله; also written Abdul Ilah or Abdullah; 14 November 1913 – 14 July 1958) was a cousin and brother-in-law of King Ghazi of the Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq and was regent for his first-cousin once rem ...

, Crown Princess Hiyam ('Abd al-Ilah's wife), Princess Nafeesa ('Abd al-Ilah's mother), Princess Abadiya

Aliya bint Ali (1907 – 14 July 1958) was an Iraqi princess. She was the daughter of Ali, King of Hejaz, and Princess Nafeesa, sister of Crown Prince 'Abd al-Ilah, and the aunt of King Faisal II of Iraq. She was murdered in the massacre of the ...

(Faisal's aunt) and several servants to gather in the palace courtyard (the young King having not yet moved into the newly completed Royal Palace

This is a list of royal palaces, sorted by continent.

Africa

* Abdin Palace, Cairo

* Al-Gawhara Palace, Cairo

* Koubbeh Palace, Cairo

* Tahra Palace, Cairo

* Menelik Palace

* Jubilee Palace

* Guenete Leul Palace

* Imperial Palace- Mass ...

). When they all arrived in the courtyard they were told to turn towards the palace wall. All were then shot by Captain Abdus Sattar As Sab’, a member of the coup led by Qasim.T. Abdullah, ''A Short History of Iraq: 636 to the present'', Pearson Education

Pearson Education is a British-owned education publishing and assessment service to schools and corporations, as well for students directly. Pearson owns educational media brands including Addison–Wesley, Peachpit, Prentice Hall, eColleg ...

, Harlow, UK,(2003)

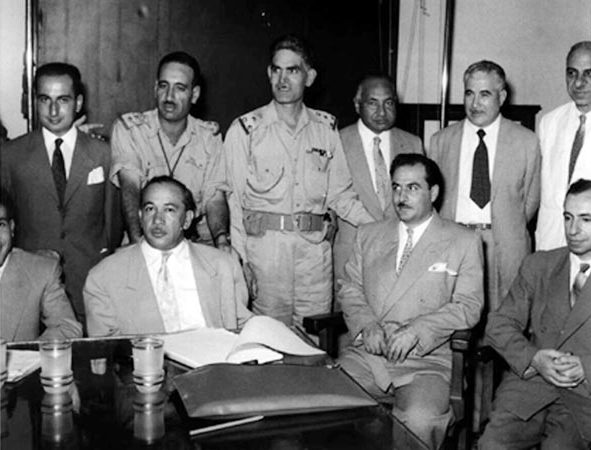

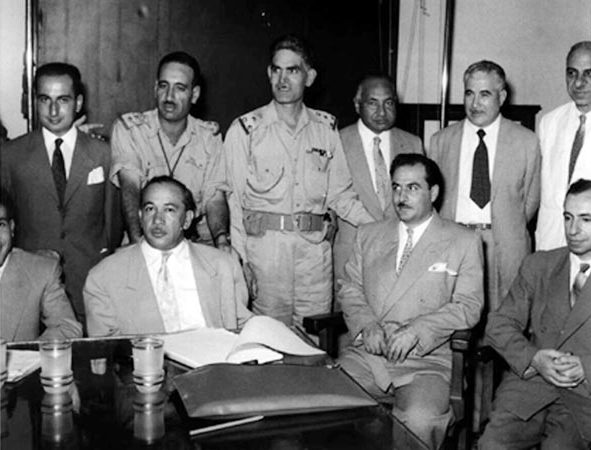

In the wake of the brutal coup, the new Iraqi Republic was proclaimed and headed by a Revolutionary Council. At its head was a three-man Sovereignty Council, composed of members of Iraq's three main communal/ethnic groups. Muhammad Mahdi Kubbah

Muhammad Mahdi Kubba ( ar, محمد مهدي كبة) (19001984) was an Iraqi politician and Vice President.

Kubba was the President of the Iraqi Independence Party.

Sovereignty Council

In the wake of the 14 July Revolution, the new Iraqi Repub ...

represented the Arab Shi’a

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that the Islamic prophet Muhammad designated ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his successor (''khalīfa'') and the Imam (spiritual and political leader) after him, most ...

population; Khalid al-Naqshabandi the Kurds ug:كۇردلار

Kurds ( ku, کورد ,Kurd, italic=yes, rtl=yes) or Kurdish people are an Iranian peoples, Iranian ethnic group native to the mountainous region of Kurdistan in Western Asia, which spans southeastern Turkey, northwestern Ir ...

; and Najib al Rubay’i

Muhammad Najib Ar-Ruba'i ( ar, محمد نجيب الربيعي) (also spelled Al-Rubai) (1904–1965) was the first president of Iraq (Chairman of Sovereignty Council), from July 14, 1958 to February 8, 1963. Together with Abdul Karim Qassim ...

the Arab Sunni population. This tripartite Council was to assume the role of the Presidency. A cabinet was created, composed of a broad spectrum of Iraqi political movements, including two National Democratic Party representatives, one member of al-Istiqlal, one Ba’ath representative and one Marxist.

After seizing power, Qasim assumed the post of Prime Minister and Defence Minister, while Colonel Arif was selected as Deputy Prime Minister and Interior Minister. They became the highest authority in Iraq with both executive and legislative powers. Muhammad Najib ar-Ruba'i

Muhammad Najib Ar-Ruba'i ( ar, محمد نجيب الربيعي) (also spelled Al-Rubai) (1904–1965) was the first president of Iraq (Chairman of Sovereignty Council), from July 14, 1958 to February 8, 1963. Together with Abdul Karim Qassim ...

became Chairman of the Sovereignty Council (head of state), but his power was very limited.

On 26 July 1958, the Interim Constitution was adopted, pending a permanent law to be promulgated after a free referendum. According to the document, Iraq was to be a republic and a part of the Arab nation while the official state religion was listed as Islam. Powers of legislation were vested in the Council of Ministers, with the approval of the Sovereignty Council, whilst executive function was also vested in the Council of Ministers.

Prime minister

pan-Arabism

Pan-Arabism ( ar, الوحدة العربية or ) is an ideology that espouses the unification of the countries of North Africa and Western Asia from the Atlantic Ocean to the Arabian Sea, which is referred to as the Arab world. It is closely c ...

movement and practise ''qawmiyah'' (Arab nationalism) policies, once in power Qasim soon modified his views to what is known today as Qasimism. Qasim, reluctant to tie himself too closely to Nasser's Egypt, sided with various groups within Iraq (notably the social democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote s ...

) that told him such an action would be dangerous. Instead he found himself echoing the views of his predecessor, Said, by adopting a ''wataniyah'' policy of "Iraq First". This caused a divide in the Iraqi government between the Iraqi nationalist Qasim, who wanted Iraq's identity to be secular and civic nationalist, revolving around Mesopotamian identity, and the Arab nationalists who sought an Arab identity

Arab identity ( ar, الهوية العربية ) is the objective or subjective state of perceiving oneself as an Arab and as relating to being Arab. Like other cultural identities, it relies on a common culture, a traditional lineage, the com ...

for Iraq and closer ties to the rest of the Arab world.

Iraqi Communist Party

The Iraqi Communist Party ( ar, الحزب الشيوعي العراقي '; ku, Partiya Komunista Iraqê حزبی شیوعی عێراق) is a communist party and the oldest active party in Iraq. Since its foundation in 1934, it has dominated the ...

, and demanded the annexation of Kuwait. He was also involved in the 1958 Agrarian Reform, modelled after the Egyptian experiment of 1952.

Qasim was said by his admirers to have worked to improve the position of ordinary people in Iraq, after the long period of self-interested rule by a small elite under the monarchy which had resulted in widespread social unrest. Qasim passed law No. 80 which seized 99% of Iraqi land from the British-owned Iraq Petroleum Company, and distributed farms to more of the population. This increased the size of the middle class. Qasim also oversaw the building of 35,000 residential units to house the poor and lower middle class

In developed nations around the world, the lower middle class is a subdivision of the greater middle class. Universally, the term refers to the group of middle class households or individuals who have not attained the status of the upper middle ...

es. The most notable example of this was the new suburb of Baghdad named Madinat al-Thawra (revolution city), renamed Saddam City under the Ba'ath regime and now widely referred to as Sadr City

Sadr City ( ar, مدينة الصدر, translit=Madīnat aṣ-Ṣadr), formerly known as Al-Thawra ( ar, الثورة, aṯ-Ṯawra) and Saddam City ( ar, مدينة صدام, Madīnat Ṣaddām), is a suburb district of the city of Baghdad, Iraq. ...

. Qasim rewrote the constitution to encourage women's participation in society.

Qasim tried to maintain the political balance by using the traditional opponents of pan-Arabs, the right wing

Right-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that view certain social orders and Social stratification, hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this pos ...

and nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

s. Up until the war with the Kurdish factions in the north, he was able to maintain the loyalty of the army.

He appointed as a minister Naziha al-Dulaimi

Naziha Jawdet Ashgah al-Dulaimi (1923 – 9 October 2007) was an early pioneer of the Iraqi feminist movement. She was a co-founder and the first president of the Iraqi Women League, the first woman minister in Iraq's modern history, and t ...

, who became the first woman minister in the history of Iraq and the Arab world. She also participated in the drafting of the 1959 Civil Affairs Law, which was far ahead of its time in liberalising marriage and inheritance laws for the benefit of Iraqi women.

Power struggles

Despite a shared military background, the group of Free Officers that carried out 14 July Revolution was plagued by internal dissension. Its members lacked both a coherent ideology and an effective organisational structure. Many of the more senior officers resented having to take orders from Arif, their junior in rank. A power struggle developed between Qasim and Arif over joining the Egyptian-Syrian union. Arif's pro-Nasserite

Nasserism ( ) is an Arab nationalist and Arab socialist political ideology based on the thinking of Gamal Abdel Nasser, one of the two principal leaders of the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, and Egypt's second President. Spanning the domestic and ...

sympathies were supported by the Ba'ath Party

The Arab Socialist Baʿath Party ( ar, حزب البعث العربي الاشتراكي ' ) was a political party founded in Syria by Mishel ʿAflaq, Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn al-Bītār, and associates of Zaki al-ʾArsūzī. The party espoused ...

, while Qasim found support for his anti-unification position in the ranks of the Iraqi Communist Party

The Iraqi Communist Party ( ar, الحزب الشيوعي العراقي '; ku, Partiya Komunista Iraqê حزبی شیوعی عێراق) is a communist party and the oldest active party in Iraq. Since its foundation in 1934, it has dominated the ...

.

Qasim's change of policy aggravated his relationship with Arif who, despite being subordinate to Qasim, had gained great prestige as the perpetrator of the coup. Arif capitalised upon his new-found position by engaging in a series of widely publicised public orations, during which he strongly advocated union with the UAR and making numerous positive references to Nasser, while remaining noticeably less full of praise for Qasim. Arif's criticism of Qasim became gradually more pronounced. This led Qasim to take steps to counter his potential rival. He began to foster relations with the Iraqi Communist Party, which attempted to mobilise support in favour of his policies. He also moved to counter Arif's power base by removing him from his position as deputy commander of the armed forces.

On 30 September 1958 Qasim removed Arif from his roles as Deputy Prime Minister and as Minister of the Interior. Qasim attempted to remove Arif's disruptive influence by offering him a role as Iraqi ambassador to West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

in Bonn

The federal city of Bonn ( lat, Bonna) is a city on the banks of the Rhine in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with a population of over 300,000. About south-southeast of Cologne, Bonn is in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ru ...

. Arif refused, and in a confrontation with Qasim on 11 October he is reported to have drawn his pistol in Qasim's presence, although whether it was to assassinate Qasim or commit suicide is a source of debate. No blood was shed, and Arif agreed to depart for Bonn. However, his time in Germany was brief, as he attempted to return to Baghdad on 4 November amid rumours of an attempted coup against Qasim. He was promptly arrested, and charged on 5 November with the attempted assassination of Qasim and attempts to overthrow the regime. He was brought to trial for treason and condemned to death in January 1959. He was subsequently pardoned in December 1962 and was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Although the threat of Arif had been negated, another soon arose in the form of Rashid Ali

Rashid Ali al-Gaylaniin Arab standard pronunciation Rashid Aali al-Kaylani; also transliterated as Sayyid Rashid Aali al-Gillani, Sayyid Rashid Ali al-Gailani or sometimes Sayyad Rashid Ali el Keilany ("Sayyad" serves to address higher standing m ...

, the exiled former prime minister who had fled Iraq in 1941. He attempted to foster support among officers who were unhappy with Qasim's policy reversals. A coup was planned for 9 December 1958, but Qasim was prepared, and instead had the conspirators arrested on the same date. Ali was imprisoned and sentenced to death, although the execution was never carried out.

Relations with Iran

Relations with Iran and the West deteriorated significantly under Qasim's leadership. He actively opposed the presence of foreign troops in Iraq and spoke out against it. Relations with Iran were strained due to his call for Arab territory within Iran to be annexed to Iraq, and Iran continued to actively fund and facilitate Kurdish rebels in the north of Iraq. Relations with the Pan-Arab Nasserist factions such as the Arab Struggle Party caused tensions with the United Arab Republic (UAR), and as a result the UAR began to aid rebellions in Iraqi Kurdistan against the government.Kurdish revolts

The new Government declared Kurdistan "one of the two nations of Iraq". During his rule, the Kurdish groups selected

The new Government declared Kurdistan "one of the two nations of Iraq". During his rule, the Kurdish groups selected Mustafa Barzani

Mustafa Barzani ( ku, مەلا مستهفا بارزانی, Mistefa Barzanî; 14 March 1903 – 1 March 1979) also known as Mela Mustafa (Preacher Mustafa), was a Kurdish leader, general and one of the most prominent political figures in mod ...

to negotiate with the government, seeking an opportunity to declare independence.

After a period of relative calm, the issue of Kurdish autonomy (self-rule or independence) went unfulfilled, sparking discontent and eventual rebellion among the Kurds in 1961. Kurdish separatists under the leadership of Mustafa Barzani chose to wage war against the Iraqi establishment. Although relations between Qasim and the Kurds had been positive initially, by 1961 relations had deteriorated and the Kurds had become openly critical of Qasim's regime. Barzani had delivered an ultimatum to Qasim in August 1961 demanding an end to authoritarian rule, recognition of Kurdish autonomy, and restoration of democratic liberties.

The Mosul uprising and subsequent unrest

During Qasim's term, there was much debate over whether Iraq should join theUnited Arab Republic

The United Arab Republic (UAR; ar, الجمهورية العربية المتحدة, al-Jumhūrīyah al-'Arabīyah al-Muttaḥidah) was a sovereign state in the Middle East from 1958 until 1971. It was initially a political union between Eg ...

, led by Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein, . (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian politician who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 and introduced far-r ...

. Having dissolved the Hashemite Arab Federation

The Hashemite Arab Federation was a short-lived country that was formed in 1958 from the union between the Hashemite Kingdoms of Iraq and Jordan. Although the name implies a federal structure, it was ''de facto'' a confederation.

The Federation ...

with the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

, Qasim refused to allow Iraq to enter the federation, although his government recognized the republic and considered joining it later.

Qasim's growing ties with the communists served to provoke rebellion in the northern Iraqi city of Mosul led by Arab nationalists in charge of military units. In an attempt to reduce the likelihood of a potential coup, Qasim had encouraged a communist backed Peace Partisans rally to be held in Mosul on 6 March 1959. Some 250,000 Peace Partisans and communists thronged through Mosul's streets that day, and although the rally passed peacefully, on 7 March, skirmishes broke out between communists and nationalists. This degenerated into a major civil disturbance over the following days. Although the rebellion was crushed by the military, it had a number of adverse effects that impacted Qasim's position. First, it increased the power of the communists. Second, it increased the strength of the Ba’ath Party

The Arab Socialist Baʿath Party ( ar, حزب البعث العربي الاشتراكي ' ) was a political party founded in Syria by Mishel ʿAflaq, Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn al-Bītār, and associates of Zaki al-ʾArsūzī. The party espoused ...

, which had been growing steadily since the 14 July coup. The Ba'ath Party believed that the only way of halting the engulfing tide of communism was to assassinate Qasim.

The Ba'ath Party turned against Qasim because of his refusal to join Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein, . (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian politician who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 and introduced far-r ...

's United Arab Republic. To strengthen his own position within the government, Qasim created an alliance with the Iraqi Communist Party

The Iraqi Communist Party ( ar, الحزب الشيوعي العراقي '; ku, Partiya Komunista Iraqê حزبی شیوعی عێراق) is a communist party and the oldest active party in Iraq. Since its foundation in 1934, it has dominated the ...

(ICP), which was opposed to any notion of pan-Arabism. Later that year, the Ba'ath Party leadership put in place plans to assassinate Qasim. Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein ( ; ar, صدام حسين, Ṣaddām Ḥusayn; 28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 16 July 1979 until 9 April 2003. A leading member of the revolution ...

was a leading member of the operation. At the time, the Ba'ath Party was more of an ideological experiment than a strong anti-government fighting machine. The majority of its members were either educated professionals or students, and Saddam fitted in well within this group.

The choice of Saddam was, according to journalist Con Coughlin

Con Coughlin (born 14 January 1955) is a British journalist and author, currently ''The Daily Telegraph'' defence editor.

Early life

Coughlin was born in 1955 in London, England. He read Modern History at Brasenose College, Oxford, where he spe ...

, "hardly surprising". The idea of assassinating Qasim may have been Nasser's, and there is speculation that some of those who participated in the operation received training in Damascus, which was then part of the United Arabic Republic. However, "no evidence has ever been produced to implicate Nasser directly in the plot".

The assassins planned to ambush Qasim on Al-Rashid Street on 7 October 1959. One man was to kill those sitting at the back of the car, the others killing those in front. During the ambush it was claimed that Saddam began shooting prematurely, which disrupted the whole operation. Qasim's chauffeur was killed, and Qasim was hit in the arm and shoulder. The would-be assassins believed they had killed him and quickly retreated to their headquarters, but Qasim survived.

The growing influence of communism was felt throughout 1959. A communist-sponsored purge of the armed forces was carried out in the wake of the Mosul revolt. The Iraqi cabinet began to shift towards the radical-left as several communist sympathisers gained posts in the cabinet. Iraq's foreign policy began to reflect this communist influence, as Qasim removed Iraq from the Baghdad Pact

The Middle East Treaty Organization (METO), also known as the Baghdad Pact and subsequently known as the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), was a military alliance of the Cold War. It was formed in 24 February 1955 by Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Turk ...

on 24 March, and then fostered closer ties with the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, including extensive economic agreements. However, communist successes encouraged them to attempt to expand their power. The communists attempted to replicate their success at Mosul in Kirkuk. A rally was called for 14 July which was intended to intimidate conservative elements. Instead it resulted in widespread bloodshed between ethnic Kurds (who were associated with the ICP at the time) and Iraqi Turkmen

The Iraqi Turkmens (also spelled as Turkoman and Turcoman; tr, Irak Türkmenleri), also referred to as Iraqi Turks, Turkish-Iraqis, the Turkish minority in Iraq, and the Iraqi-Turkish minority ( ar, تركمان العراق; tr, Irak Türkleri ...

, leaving between 30 and 80 people dead.

Despite being largely the result of pre-existing ethnic tensions, the Kirkuk "massacre" was exploited by Iraqi anti-communists and Qasim subsequently purged the communists and in early 1960 he refused to license the ICP as a legitimate political party. Qasim's actions led to a major reduction of communist influence in the Iraqi government. Communist influence in Iraq peaked in 1959 and the ICP squandered its best chance of taking power by remaining loyal to Qasim, while his attempts to appease Iraqi nationalists backfired and contributed to his eventual overthrow. For example, Qasim released Salih Mahdi Ammash

Salih Mahdi Ammash ( ar, صالح مهدي عماش; 1924 – 30 January 1985) was an Iraqi historian, writer, author, poet and Iraqi Regional Branch politician and Iraqi army officer who sat on the Regional Command from 1963 to 1971.

Life

He w ...

from custody and reinstated him in the Iraqi army, allowing Ammash to act as the military liaison to the Ba'athist coup plotters. Furthermore, notwithstanding his outwardly friendly posture towards the Kurds, Qasim was unable to grant Kurdistan autonomous status within Iraq, leading to the 1961 outbreak of the First Iraqi–Kurdish War

The First Iraqi–Kurdish WarMichael G. Lortz. (Chapter 1, Introduction). ''The Kurdish Warrior Tradition and the Importance of the Peshmerga''. pp.39-42. (Arabic: الحرب العراقية الكردية الأولى) also known as Aylul revo ...

and secret contacts between the Kurdistan Democratic Party

The Kurdistan Democratic Party ( ku, Partiya Demokrat a Kurdistanê; پارتی دیموکراتی کوردستان), usually abbreviated as KDP or PDK, is the largest party in Iraqi Kurdistan and the senior partner in the Kurdistan Regional G ...

(KDP) and Qasim's Ba'athist opponents in 1962 and 1963. The KDP promised not to aid Qasim in the event of a Ba'athist coup, ignoring long-standing Kurdish antipathy towards pan-Arab ideology. Disagreements between Qasim, the ICP and the Kurds thus created a power vacuum that was exploited by a "tiny" group of Iraqi Ba'athists in 1963.

Foreign policy

Qasim had withdrawn Iraq from the pro-Western Baghdad Pact in March 1959 and established friendly relations with the Soviet Union. Iraq also abolished its treaty of mutual security and bilateral relations with the UK. Iraq also withdrew from the agreement with theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

that was signed by the Iraqi monarchy in 1954 and 1955 regarding military, arms, and equipment. On 30 May 1959, the last of the British soldiers and military officers departed the al-Habbāniyya base in Iraq. Qasim supported the Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, religi ...

n and Palestinian

Palestinians ( ar, الفلسطينيون, ; he, פָלַסְטִינִים, ) or Palestinian people ( ar, الشعب الفلسطيني, label=none, ), also referred to as Palestinian Arabs ( ar, الفلسطينيين العرب, label=non ...

struggles against France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

and Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

.

Qasim further undermined his rapidly deteriorating domestic position with a series of foreign policy blunders. In 1959 Qasim antagonised Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkm ...

with a series of territory disputes, most notably over the Khuzestan

Khuzestan Province (also spelled Xuzestan; fa, استان خوزستان ''Ostān-e Xūzestān'') is one of the 31 provinces of Iran. It is in the southwest of the country, bordering Iraq and the Persian Gulf. Its capital is Ahvaz and it cover ...

region of Iran, which was home to an Arabic-speaking minority, and the division of the Shatt al-Arab

The Shatt al-Arab ( ar, شط العرب, lit=River of the Arabs; fa, اروندرود, Arvand Rud, lit=Swift River) is a river of some in length that is formed at the confluence of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers in the town of al-Qurnah in ...

waterway between south eastern Iraq and western Iran. On 18 December 1959, Abd al-Karim Qasim declared:

"We do not wish to refer to the history of Arab tribes residing in Al-Ahwaz and Muhammareh (Khurramshahr

Khorramshahr ( fa, خرمشهر , also romanized as ''Khurramshahr'', ar, المحمرة, romanized as ''Al-Muhammerah'') is a city and capital of Khorramshahr County, Khuzestan Province, Iran. At the 2016 census, its population was 170,976, in ...

). The Ottomans handed over Muhammareh, which was part of Iraqi territory, to Iran."

After this, Iraq started supporting secessionist movements in Khuzestan, and even raised the issue of its territorial claims at a subsequent meeting of the Arab League, without success.

In June 1961, Qasim re-ignited the Iraqi claim over the state of Kuwait

Kuwait (; ar, الكويت ', or ), officially the State of Kuwait ( ar, دولة الكويت '), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated in the northern edge of Eastern Arabia at the tip of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to the no ...

. On 25 June, he announced in a press conference that Kuwait was a part of Iraq, and claimed its territory. Kuwait, however, had signed a recent defence treaty with the British, who came to Kuwait's assistance with troops to stave off any attack on 1 July. These were subsequently replaced by an Arab force (assembled by the Arab League) in September, where they remained until 1962.

The result of Qasim's foreign policy blunders was to further weaken his position. Iraq was isolated from the Arab world for its part in the Kuwait incident, whilst Iraq had antagonised its powerful neighbour, Iran. Western attitudes toward Qasim had also cooled, due to these incidents and his perceived communist sympathies. Iraq was isolated internationally, and Qasim became increasingly isolated domestically, to his considerable detriment.

After assuming power, Qasim demanded that the Anglo American-owned Iraq Petroleum Company

The Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC), formerly known as the Turkish Petroleum Company (TPC), is an oil company that had a virtual monopoly on all oil exploration and production in Iraq between 1925 and 1961. It is jointly owned by some of the world' ...

(IPC) sell a 20% ownership stake to the Iraqi government, increase Iraqi oil production, hire Iraqi managers, and cede control of most of its concessionary holding

A concession or concession agreement is a grant of rights, land or property by a government, local authority, corporation, individual or other legal entity.

Public services such as water supply may be operated as a concession. In the case of a ...

. When the IPC failed to meet these conditions, Qasim issued Public Law 80 on 11 December 1961, which unilaterally limited the IPC's concession to those areas where oil was actually being produced—namely, the fields at Az Zubair

Az Zubayr ( ar, الزبير) is a city in and the capital of Al-Zubair District, part of the Basra Governorate of Iraq. The city is just south of Basra. The name can also refer to the old Emirate of Zubair.

The name is also sometimes written Al ...

and Kirkuk—while all other territories (including North Rumaila) were returned to Iraqi state control. This effectively expropriated 99.5% of the concession. British and US officials and multinationals demanded that the Kennedy administration place pressure on the Qasim regime. The Government of Iraq, under Qasim, along with five petroleum-exporting nations met at a conference held 10–14 September 1960 in Baghdad, which led to the creation of the International Organization of Petroleum-Exporting Countries (OPEC

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC, ) is a cartel of countries. Founded on 14 September 1960 in Baghdad by the first five members (Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela), it has, since 1965, been headquart ...

).

Overthrow and execution

In 1962, both the Ba'ath Party and the United StatesCentral Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

(CIA) began plotting to overthrow Qasim, with U.S. government officials cultivating supportive relationships with Ba'athist leaders and others opposed to Qasim. On 8 February 1963, Qasim was overthrown by the Ba'athists in the Ramadan Revolution

The Ramadan Revolution, also referred to as the 8 February Revolution and the February 1963 coup d'état in Iraq, was a military coup by the Ba'ath Party's Iraqi-wing which overthrew the Prime Minister of Iraq, Abd al-Karim Qasim in 1963. It t ...

; long suspected to be supported by the CIA. Pertinent contemporary documents relating to the CIA's operations in Iraq have remained classified and as of 2021, " holars are only beginning to uncover the extent to which the United States was involved in organizing the coup", but are "divided in their interpretations of American foreign policy". Bryan R. Gibson, writes that although " is accepted among scholars that the CIA ... assisted the Ba’th Party in its overthrow of asim'sregime", that "barring the release of new information, the preponderance of evidence substantiates the conclusion that the CIA was not behind the February 1963 Ba'thist coup". Likewise, Peter Hahn argues that " classified U.S. government documents offer no evidence to support" suggestions of direct U.S. involvement. On the other hand, Brandon Wolfe-Hunnicutt cites "compelling evidence of an American role", and that publicly declassified documents "largely substantiate the plausibility" of CIA involvement in the coup. Eric Jacobsen, citing the testimony of contemporary prominent Ba'athists and U.S. government officials, states that " ere is ample evidence that the CIA not only had contacts with the Iraqi Ba'th in the early sixties, but also assisted in the planning of the coup". Nathan J. Citino writes that "Washington backed the movement by military officers linked to the pan-Arab Ba‘th Party that overthrew Qasim", but that "the extent of U.S. responsibility cannot be fully established on the basis of available documents", and that " though the United States did not initiate the 14 Ramadan coup, at best it condoned and at worst it contributed to the violence that followed".

Qasim was given a short show trial and was shot soon after. Many of Qasim's Shi'ite supporters believed that he had merely gone into hiding and would appear like the

Qasim was given a short show trial and was shot soon after. Many of Qasim's Shi'ite supporters believed that he had merely gone into hiding and would appear like the Mahdi

The Mahdi ( ar, ٱلْمَهْدِيّ, al-Mahdī, lit=the Guided) is a messianic figure in Islamic eschatology who is believed to appear at the end of times to rid the world of evil and injustice. He is said to be a descendant of Muhammad w ...

to lead a rebellion against the new government. To counter this sentiment and terrorise his supporters, Qasim's dead body was displayed on television in a five-minute long propaganda video called ''The End of the Criminals'' that included close-up views of his bullet wounds amid disrespectful treatment of his corpse, which was spat on in the final scene. About 100 government loyalists were killed in the fighting as well as between 1,500 and 5,000 civilian supporters of the Qasim administration or the Iraqi Communist Party

The Iraqi Communist Party ( ar, الحزب الشيوعي العراقي '; ku, Partiya Komunista Iraqê حزبی شیوعی عێراق) is a communist party and the oldest active party in Iraq. Since its foundation in 1934, it has dominated the ...

during the three-day "house-to-house search" that immediately followed the coup.

Legacy

The 1958 Revolution can be considered a watershed in Iraqi politics, not just because of its obvious political implications (e.g. the abolition of monarchy, republicanism, and paving the way for Ba'athist rule) but also because of its domestic reforms. Despite its shortcomings, Qasim's rule helped to implement a number of positive domestic changes that benefited Iraqi society and were widely popular, especially the provision of low-cost housing to the inhabitants of Baghdad's urban slums. While criticising Qasim's "irrational and capricious behaviour" and "extraordinarily quixotic attempt to annex Kuwait in the summer of 1961", actions that raised "serious doubts about his sanity", Marion Farouk–Sluglett and Peter Sluglett conclude that, "Qasim's failings, serious as they were, can scarcely be discussed in the same terms as the venality, savagery and wanton brutality characteristic of the regimes which followed his own". Despite upholding death sentences against those involved in the

The 1958 Revolution can be considered a watershed in Iraqi politics, not just because of its obvious political implications (e.g. the abolition of monarchy, republicanism, and paving the way for Ba'athist rule) but also because of its domestic reforms. Despite its shortcomings, Qasim's rule helped to implement a number of positive domestic changes that benefited Iraqi society and were widely popular, especially the provision of low-cost housing to the inhabitants of Baghdad's urban slums. While criticising Qasim's "irrational and capricious behaviour" and "extraordinarily quixotic attempt to annex Kuwait in the summer of 1961", actions that raised "serious doubts about his sanity", Marion Farouk–Sluglett and Peter Sluglett conclude that, "Qasim's failings, serious as they were, can scarcely be discussed in the same terms as the venality, savagery and wanton brutality characteristic of the regimes which followed his own". Despite upholding death sentences against those involved in the 1959 Mosul uprising

The 1959 Mosul Uprising was an attempted coup by Arab nationalists in Mosul who wished to depose the then Iraqi Prime Minister Abd al-Karim Qasim, and install an Arab nationalist government which would then join the Republic of Iraq with the U ...

, Qasim also demonstrated "considerable magnanimity towards those who had sought at various times to overthrow him", including through large amnesties "in October and November 1961". Furthermore, not even Qasim's harshest critics could paint him as corrupt.

Land reform

The revolution brought about sweeping changes in the Iraqi agrarian sector. Reformers dismantled the old feudal structure of rural Iraq. For example, the 1933 Law of Rights and Duties of Cultivators and the Tribal Disputes Code were replaced, benefiting Iraq's peasant population and ensuring a fairer process of law. The Agrarian Reform Law (30 September 1958 Reporting article on discovery of Qasim's body ) attempted a large-scale redistribution of landholdings and placed ceilings on ground rents; the land was more evenly distributed among peasants who, due to the new rent laws, received around 55% to 70% of their crop. While "inadequate" and allowing for "fairly generous" large holdings, the land reform was successful at reducing the political influence of powerful landowners, who under the Hashemite monarchy had wielded significant power.Women's rights

Qasim attempted to bring about greater equality for women in Iraq. In December 1959 he promulgated a significant revision of the personal status code, particularly that regulating family relations.Polygamy

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is marri ...

was outlawed, and minimum ages for marriage were also set out, with 18 being the minimum age (except for special dispensation when it could be lowered by the court to 16). Women were also protected from arbitrary divorce. The most revolutionary reform was a provision in Article 74 giving women equal rights in matters of inheritance. The laws applied to Sunni and Shi’a alike. The laws encountered much opposition and did not survive Qasim's government.

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * *External links

* * Qasim, Abd al-Karim (1959)"Principles of 14th July revolution; a few collections of the epoch-making speeches delivered on some auspicious and historical occasions after the blessed, peaceful and miraculous revolution of July 14, 1958"

Baghdad; Times Press. * Christopher Solomon

60 years after Iraq’s 1958 July 14 Revolution

Gulf International Forum, 9 August 2018 {{DEFAULTSORT:Qasim, Abd Al-Karim Prime ministers of Iraq 20th century in Iraq 1914 births 1963 deaths Iraqi nationalists Leaders who took power by coup Leaders ousted by a coup Executed prime ministers Politicians from Baghdad Iraqi Muslims Iraqi generals Articles containing video clips Executed Iraqi people People executed by Iraq by firing squad 20th-century executions by Iraq Iraqi Military Academy alumni People of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War