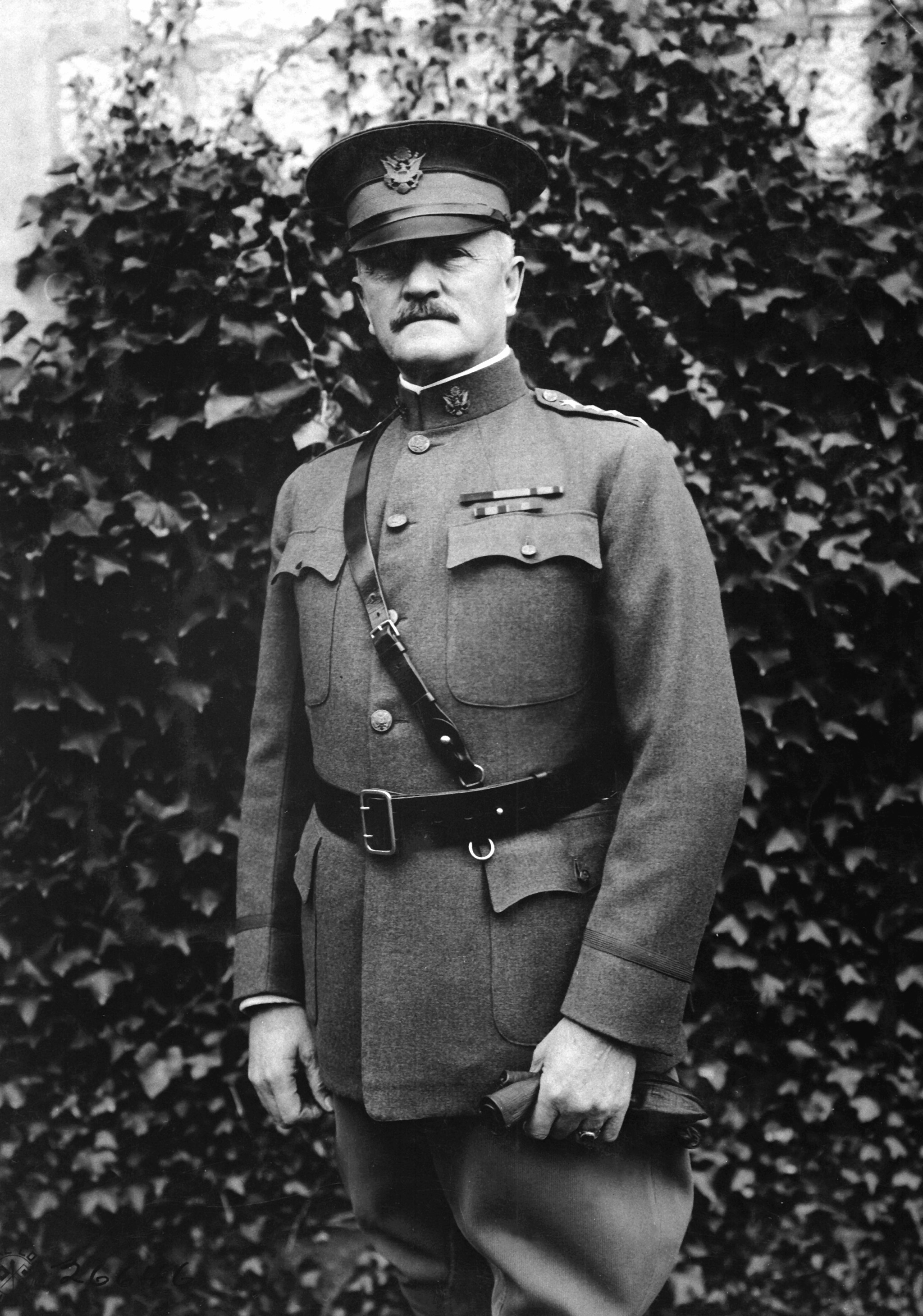

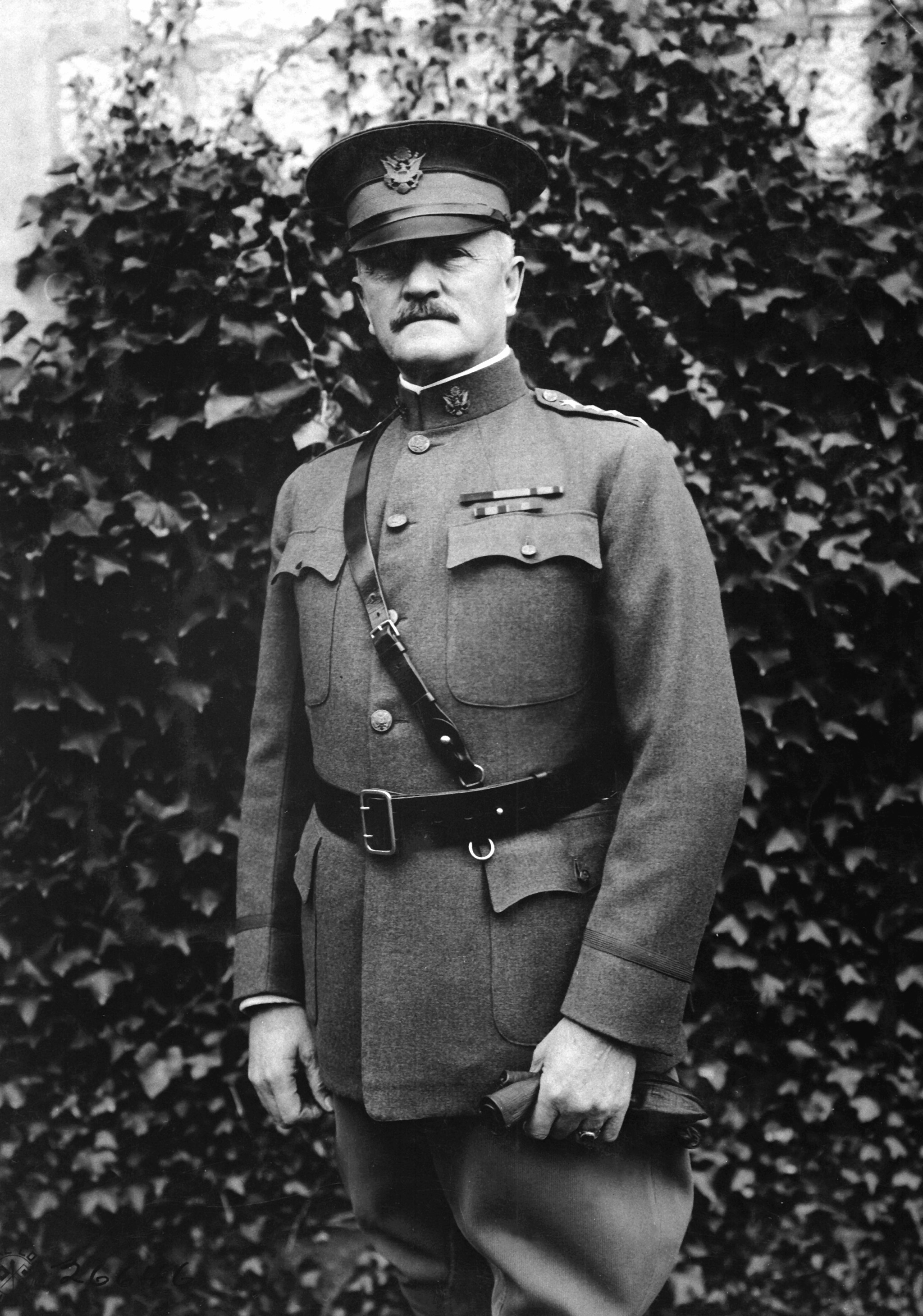

General Pershing on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pershing was sworn in as a West Point cadet in July 1882. He was selected early for leadership positions and became successively First Corporal, First Sergeant, First Lieutenant, and First Captain, the highest possible cadet rank. Pershing also commanded, ''

Pershing was sworn in as a West Point cadet in July 1882. He was selected early for leadership positions and became successively First Corporal, First Sergeant, First Lieutenant, and First Captain, the highest possible cadet rank. Pershing also commanded, ''

In 1897, Pershing was appointed to the West Point tactical staff as an instructor, where he was assigned to Cadet Company A. Because of his strictness and rigidity, Pershing was unpopular with the cadets, who took to calling him "

In 1897, Pershing was appointed to the West Point tactical staff as an instructor, where he was assigned to Cadet Company A. Because of his strictness and rigidity, Pershing was unpopular with the cadets, who took to calling him "

''My Life Before the World War, 1860–1917: A Memoir''

, pages 284–85 Lexington, Kentucky:

"Trump said to study General Pershing. Here's what the president got wrong"

''

"Study Pershing, Trump Said. But the Story Doesn't Add Up"

''

For the first time in American history, Pershing allowed American soldiers to be under the command of a foreign power. In late June, General Sir Henry Rawlinson, commanding the British Fourth Army, suggested to Australian Lieutenant General

For the first time in American history, Pershing allowed American soldiers to be under the command of a foreign power. In late June, General Sir Henry Rawlinson, commanding the British Fourth Army, suggested to Australian Lieutenant General

When General Pershing met General Pétain at Compiègne at 10:45pm on the evening of March 25, 1918, Pétain told him he had few reserves left to stop the

When General Pershing met General Pétain at Compiègne at 10:45pm on the evening of March 25, 1918, Pétain told him he had few reserves left to stop the

American successes were largely credited to Pershing, and he became the most celebrated American leader of the war. MacArthur, however, saw Pershing as a desk soldier, and the relationship between the two men deteriorated by the end of the war. Similar criticism of senior commanders by the younger generation of officers (the future generals of

American successes were largely credited to Pershing, and he became the most celebrated American leader of the war. MacArthur, however, saw Pershing as a desk soldier, and the relationship between the two men deteriorated by the end of the war. Similar criticism of senior commanders by the younger generation of officers (the future generals of

On November 1, 1921, Pershing was in

On November 1, 1921, Pershing was in

*1882: Cadet, United States Military Academy

*1886: Troop L, Sixth Cavalry

*1891: Professor of tactics, University of Nebraska–Lincoln

*1895: 1st lieutenant, 10th Cavalry Regiment

*1897: Instructor, United States Military Academy, West Point

*1898: Major of Volunteer Forces, Cuban Campaign, Spanish–American War

*1899: Officer-in-charge, Office of Customs and Insular Affairs

*1900: Adjutant general, Department of Mindanao and Jolo, Philippines

*1901: Battalion officer, 1st Cavalry and intelligence officer, 15th Cavalry (Philippines)

*1902: Officer-in-charge, Camp Vicars, Philippines

*1904: Assistant chief of staff, Southwest Army Division, Oklahoma

*1905: Military attaché, U.S. Embassy,

*1882: Cadet, United States Military Academy

*1886: Troop L, Sixth Cavalry

*1891: Professor of tactics, University of Nebraska–Lincoln

*1895: 1st lieutenant, 10th Cavalry Regiment

*1897: Instructor, United States Military Academy, West Point

*1898: Major of Volunteer Forces, Cuban Campaign, Spanish–American War

*1899: Officer-in-charge, Office of Customs and Insular Affairs

*1900: Adjutant general, Department of Mindanao and Jolo, Philippines

*1901: Battalion officer, 1st Cavalry and intelligence officer, 15th Cavalry (Philippines)

*1902: Officer-in-charge, Camp Vicars, Philippines

*1904: Assistant chief of staff, Southwest Army Division, Oklahoma

*1905: Military attaché, U.S. Embassy,

;Distinguished Service Cross Citation

;Distinguished Service Cross Citation

In 1940 General Pershing was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary heroism in action leading an assault against hostile Moros at Mount Bagsak, on the island of Jolo in the Philippines on June 15, 1913.American Decorations. Supplement V. July 1, 1940 – June 30, 1941. Government Printing Office. Washington. 1941. p. 1.

;Citation:

In 1940 General Pershing was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary heroism in action leading an assault against hostile Moros at Mount Bagsak, on the island of Jolo in the Philippines on June 15, 1913.American Decorations. Supplement V. July 1, 1940 – June 30, 1941. Government Printing Office. Washington. 1941. p. 1.

;Citation:

*

*

* Pershing Barracks at the United States Military Academy, West Point, NY.

* Pershing Arena, Pershing Society, Pershing Hall, and the Pershing Scholarships of Truman State University in Kirksville, Missouri (Pershing's former college)

* A bust of Pershing was created in 1921 by Bryant Baker for the Nebraska Hall of Fame. Pershing was inducted into the Nebraska Hall of Fame in 1963.

*Since 1930, the Pershing Park Memorial Association (PPMA), headquartered in Pershing's hometown of Laclede, Missouri, has been dedicated to preserving the memory of General Pershing's military history.

*On November 17, 1961, the

* Pershing Barracks at the United States Military Academy, West Point, NY.

* Pershing Arena, Pershing Society, Pershing Hall, and the Pershing Scholarships of Truman State University in Kirksville, Missouri (Pershing's former college)

* A bust of Pershing was created in 1921 by Bryant Baker for the Nebraska Hall of Fame. Pershing was inducted into the Nebraska Hall of Fame in 1963.

*Since 1930, the Pershing Park Memorial Association (PPMA), headquartered in Pershing's hometown of Laclede, Missouri, has been dedicated to preserving the memory of General Pershing's military history.

*On November 17, 1961, the

Film:

*Pershing is played by Joseph W. Girard in the 1941 film ''

Film:

*Pershing is played by Joseph W. Girard in the 1941 film ''

''Military Operations: France and Belgium: 1914-18''

London: MacMillan, 1935 *Faulkner, Richard S. ''Pershing's Crusaders: The American Soldier in World War I'' ( University Press of Kansas, 2017). xiv, 758 pp *Goldhurst, Richard. ''Pipe Clay and Drill: John J. Pershing, the classic American soldier'' (Reader's Digest Press, 1977) *Lacey, Jim. ''Pershing''. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. *Mordacq, Henri. ''Unity of Command: How it was Achieved'', Paris: Tallandier, 1929 (translated by Major J.C. Bardin, National War College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania) *O'Connor, Richard. ''Black Jack Pershing''. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1961. *Pershing, John J., and John T. Greenwood. ''My Life Before the World War, 1860–1917: A Memoir''. Lexington, Kentucky:

online review

* Yockelson, Mitchell (Foreword by John S. D. Eisenhower). ''Borrowed Soldiers: Americans under British Command, 1918'' (University of Oklahoma Press, 2008) * Yockelson, Mitchell. ''Forty-Seven Days: How Pershing's Warriors Came of Age to Defeat at the German Army in World War I'' (New York: NAL, Caliber, 2016) *

Pershing Museum

*

Black Jack Pershing in Cuba

in ttp://www.history.army.mil/books/Last_Salute/index.htm The Last Salute: Civil and Military Funeral, 1921–1969 by B. C. Mossman and M. W. Stark,

Americans Under British Command, 1918

at Borrowed Soldiers *

John J. Pershing Papers

at

John J. Pershing at the World Digital Archive

* *

The National Society of Pershing Rifles

The Pershing Foundation

* Pershing's voice (48:58 to 49:40)

''Link''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Pershing, John J. 1860 births 1948 deaths American Episcopalians American Expeditionary Forces American Freemasons American memoirists American military personnel of the Philippine–American War American military personnel of the Spanish–American War American people of English descent American people of German descent Articles containing video clips Buffalo Soldiers Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Grand Crosses of the Order of the White Lion Commanders of the Virtuti Militari Congressional Gold Medal recipients Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour Grand Crosses of the Order of the Sun of Peru Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Knights Grand Cross of the Military Order of Savoy Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus Military personnel from Missouri Nebraska lawyers Military personnel from Lincoln, Nebraska People from Linn County, Missouri People of the Mexican Revolution People of the Russo-Japanese War Pulitzer Prize for History winners American recipients of the Croix de guerre (Belgium) Recipients of the Croix de Guerre (France) Recipients of the Czechoslovak War Cross Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United States) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army) Recipients of the Order of Michael the Brave, 1st class Recipients of the Order of the Rising Sun Recipients of the Silver Star Members of the Sons of the American Revolution Truman State University alumni Chiefs of Staff of the United States Army United States Army generals of World War I United States Army generals United States Army War College alumni United States Military Academy alumni Candidates in the 1920 United States presidential election University of Nebraska–Lincoln alumni Writers from Missouri 19th-century American people 20th-century American people United States military attachés Nebraska Republicans University of Nebraska College of Law alumni American people of World War I American people of World War II University of Nebraska–Lincoln faculty United States Military Academy faculty Military leaders of World War I United States Army Cavalry Branch personnel Deaths from coronary artery disease United States Army personnel of the Indian Wars College honor society founders

General of the Armies

General of the Armies of the United States, more commonly referred to as General of the Armies, is the highest military rank in the United States. The rank has been conferred three times: to John J. Pershing in 1919, as a personal accolade fo ...

John Joseph Pershing (September 13, 1860 – July 15, 1948), nicknamed "Black Jack", was an American army general, educator, and founder of the Pershing Rifles. He served as the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces

The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) was a formation of the United States Armed Forces on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front during World War I, composed mostly of units from the United States Army, U.S. Army. The AEF was establis ...

(AEF) during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

from 1917 to 1920. In addition to leading the AEF to victory in World War I, Pershing served as a mentor to many in the generation of generals who led the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, including George C. Marshall, Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

, Omar Bradley

Omar Nelson Bradley (12 February 1893 – 8 April 1981) was a senior Officer (armed forces), officer of the United States Army during and after World War II, rising to the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He wa ...

, Lesley J. McNair, George S. Patton, and Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

.

During his command in World War I, Pershing resisted British and French demands that American forces be integrated with their armies, essentially as replacement units, and insisted that the AEF would operate as a single unit under his command, although some American units fought under British and Australian command, notably in the Battle of Hamel and the breaching of the Hindenburg Line

The Hindenburg Line (, Siegfried Position) was a German Defense line, defensive position built during the winter of 1916–1917 on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front in France during the First World War. The line ran from Arras to ...

at St Quentin Canal, precipitating the final German collapse. Pershing also allowed (at that time segregated) American all-Black units to be integrated with the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (, , ), is the principal Army, land warfare force of France, and the largest component of the French Armed Forces; it is responsible to the Government of France, alongside the French Navy, Fren ...

.

Pershing's soldiers first saw serious battle at Cantigny, Chateau-Thierry, and Belleau Wood on June 1–26, 1918, and Soissons

Soissons () is a commune in the northern French department of Aisne, in the region of Hauts-de-France. Located on the river Aisne, about northeast of Paris, it is one of the most ancient towns of France, and is probably the ancient capital ...

on July 18–22, 1918. To speed up the arrival of American troops, they embarked for France leaving heavy equipment behind, and used British and French tanks, artillery, airplanes and other munitions. In September 1918 at St. Mihiel, the First Army was directly under Pershing's command; it overwhelmed the salient – the encroachment into Allied territory – that the German Army

The German Army (, 'army') is the land component of the armed forces of Federal Republic of Germany, Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German together with the German Navy, ''Marine'' (G ...

had held for three years. For the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, Pershing shifted roughly 600,000 American soldiers to the heavily defended forests of the Argonne, keeping his divisions engaged in hard fighting for 47 days, alongside the French. The Allied Hundred Days Offensive

The Hundred Days Offensive (8 August to 11 November 1918) was a series of massive Allied offensives that ended the First World War. Beginning with the Battle of Amiens (8–12 August) on the Western Front, the Allies pushed the Imperial Germa ...

, of which the Argonne fighting was part, contributed to Germany calling for an armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from t ...

. Pershing was of the opinion that the war should continue and that all of Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

should be occupied in an effort to permanently destroy German militarism.

Pershing is the only American to be promoted in his own lifetime to General of the Armies

General of the Armies of the United States, more commonly referred to as General of the Armies, is the highest military rank in the United States. The rank has been conferred three times: to John J. Pershing in 1919, as a personal accolade fo ...

, the highest possible rank in the United States Army. Allowed to select his own insignia, Pershing chose to continue using four stars in either silver or gold. Some of his tactics have been criticized both by other commanders at the time and by modern historians. His reliance on costly frontal assaults, long after other Allied armies had abandoned such tactics, has been blamed for causing unnecessarily high American casualties.

Pershing was also criticized by some historians for his actions on the day of armistice as the commander of the American Expeditionary Force. Pershing did not approve of the armistice, and despite knowing of the imminent ceasefire, he did not tell his commanders to suspend any new offensive actions or assaults in the final few hours of the war. In total, there were nearly 11,000 casualties (3,500 American), dead, missing, or injured during November 11, the final day of the war, which exceeded the D-Day

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during the Second World War. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

casualty counts of June 1944. For instance, allied casualties on the first day of the D-Day invasion were 4,414 confirmed dead. Pershing and several subordinates were later questioned by Congress; Pershing maintained that he had followed the orders of his superior, Ferdinand Foch

Ferdinand Foch ( , ; 2 October 1851 – 20 March 1929) was a French general, Marshal of France and a member of the Académie Française and French Academy of Sciences, Académie des Sciences. He distinguished himself as Supreme Allied Commander ...

; Congress found that no one was culpable.

Early life

Pershing was born on a farm near Laclede, Missouri, on September 13, 1860, the son of farmer and store owner John Fletcher Pershing and homemaker Ann Elizabeth Thompson. Pershing's great-grandfather, Frederick ''Pfoerschin'', emigrated fromAlsace

Alsace (, ; ) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in the Grand Est administrative region of northeastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine, next to Germany and Switzerland. In January 2021, it had a population of 1,9 ...

and arrived in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

in 1749. He had five siblings who lived to adulthood: brothers James F. (1862–1933) and Ward (1874–1909), and sisters Mary Elizabeth (1864–1928), Anna May (1867–1955) and Grace (1867–1903); three other children died in infancy. When the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

began, his father supported the Union and was a sutler

A sutler or victualer is a civilian merchant who sells provisions to an army in the field, in camp, or in quarters. Sutlers sold wares from the back of a wagon or a temporary tent, traveling with an army or to remote military outposts. Sutler wa ...

for the 18th Missouri Volunteer Infantry; he died on March 16, 1906. Pershing's mother died during his initial assignment in the American West.Vandiver, v.1, p. 388

Pershing attended a school in Laclede that was reserved for precocious students who were also the children of prominent citizens, and he later attended Laclede's one-room schoolhouse. After completing high school in 1878, he became a teacher of local African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

children. While pursuing his teaching career, Pershing also studied at the State Normal School (now Truman State University

Truman State University (TSU or Truman) is a Public university, public Liberal arts college, liberal arts university in Kirksville, Missouri, United States. It had 3,664 enrolled students in the fall of 2024 pursuing degrees in 55 undergraduate ...

) in Kirksville, Missouri

Kirksville is the county seat of and most populous city in Adair County, Missouri, United States. Located in Benton Township, Adair County, Missouri, Benton Township, its population was 17,530 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Kirk ...

, from which he graduated in 1880 with a Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, B.S., B.Sc., SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree that is awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Scienc ...

degree in scientific didactics. Two years later, he competed for appointment to the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

. He performed well on the examination, and received the appointment from Congressman Joseph Henry Burrows. He later admitted that he had applied not because he was interested in a military career, but because the education was free and better than what he could obtain in rural Missouri.

West Point years

Pershing was sworn in as a West Point cadet in July 1882. He was selected early for leadership positions and became successively First Corporal, First Sergeant, First Lieutenant, and First Captain, the highest possible cadet rank. Pershing also commanded, ''

Pershing was sworn in as a West Point cadet in July 1882. He was selected early for leadership positions and became successively First Corporal, First Sergeant, First Lieutenant, and First Captain, the highest possible cadet rank. Pershing also commanded, ''ex officio

An ''ex officio'' member is a member of a body (notably a board, committee, or council) who is part of it by virtue of holding another office. The term '' ex officio'' is Latin, meaning literally 'from the office', and the sense intended is 'by r ...

,'' the honor guard that saluted the funeral train of President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

as it passed West Point in August 1885.

Pershing graduated in the summer of 1886 ranked 30th in his class of 77, and was commissioned a second lieutenant; he was commended by the West Point Superintendent, General Wesley Merritt, who said Pershing gave early promise of becoming an outstanding officer. Pershing briefly considered petitioning the Army to let him study law and delay the start of his mandatory military service. He also considered joining several classmates in a partnership that would pursue development of an irrigation project in Oregon

Oregon ( , ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while t ...

. He ultimately decided against both courses of action in favor of active Army duty.

Early career

Pershing reported for active duty on September 30, 1887, and was assigned to Troop L of the 6th U.S. Cavalry stationed at Fort Bayard, in theNew Mexico Territory

The Territory of New Mexico was an organized incorporated territory of the United States from September 9, 1850, until January 6, 1912. It was created from the U.S. provisional government of New Mexico, as a result of '' Nuevo México'' becomi ...

. While serving in the 6th Cavalry, Pershing participated in several Indian campaigns and was cited for bravery for actions against the Apache

The Apache ( ) are several Southern Athabaskan language-speaking peoples of the Southwestern United States, Southwest, the Southern Plains and Northern Mexico. They are linguistically related to the Navajo. They migrated from the Athabascan ho ...

. During his time at Fort Stanton, Pershing and close friends Lt. Julius A. Penn and Lt. Richard B. Paddock were nicknamed "The Three Green P's," spending their leisure time hunting and attending Hispanic

The term Hispanic () are people, Spanish culture, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or broadly. In some contexts, Hispanic and Latino Americans, especially within the United States, "Hispanic" is used as an Ethnici ...

dances. Pershing's sister Grace married Paddock in 1890.Vandiver, v.1, p. 67.

Between 1887 and 1890, Pershing served with the 6th Cavalry at various postings in New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

, Arizona

Arizona is a U.S. state, state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States, sharing the Four Corners region of the western United States with Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. It also borders Nevada to the nort ...

, and South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state, state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Dakota people, Dakota Sioux ...

. He also became an expert marksman and won several prizes for rifle and pistol at army shooting competitions.

On December 9, 1890, Pershing and the 6th Cavalry arrived at Fort Meade

Fort George G. Meade is a United States Army installation located in Maryland, that includes the Defense Information School, the Defense Media Activity, the United States military bands#Army Field Band, United States Army Field Band, and the head ...

, South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state, state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Dakota people, Dakota Sioux ...

where Pershing played a role in suppressing the last uprisings of the Lakota (Sioux) Indians. Though he and his unit did not participate in the Wounded Knee Massacre

The Wounded Knee Massacre, also known as the Battle of Wounded Knee, involved nearly three hundred Lakota people killed by soldiers of the United States Army. More than 250 people of the Lakota were killed and 51 wounded (4 men and 47 women a ...

, they did fight three days after it on January 1, 1891, when Sioux warriors attacked the 6th Cavalry's supply wagons. When the Sioux began firing at the wagons, Pershing and his troops heard the shots, and rode more than six miles to the location of the attack. The cavalry fired at the forces of Chief War Eagle, causing them to retreat. This was the only occasion on which Pershing saw action during the Ghost Dance campaign.

In September 1891, he was assigned as the professor of military science and tactics at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

The University of Nebraska–Lincoln (Nebraska, NU, or UNL) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Lincoln, Nebraska, United States. Chartered in 1869 by the Nebraska Legislature as part of the M ...

, a position he held until 1895. While carrying out this assignment, Pershing attended the university's College of Law, from which he received his LL.B. degree in 1893. He formed a drill company of chosen university cadets, Company A. In March 1892, it won the Maiden Prize competition of the National Competitive Drills in Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha ( ) is the List of cities in Nebraska, most populous city in the U.S. state of Nebraska. It is located in the Midwestern United States along the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's List of United S ...

. The Citizens of Omaha presented the company with a large silver cup, the "Omaha Cup". On October 2, 1894, former members of Company A established a fraternal military drill organization named the Varsity Rifles. The group renamed itself the Pershing Rifles in 1895 in honor of its mentor and patron. Pershing maintained a close relationship with Pershing Rifles for the remainder of his life.

On October 20, 1892, Pershing was promoted to first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a se ...

and in 1895 took command of a troop of the 10th Cavalry Regiment, one of the original Buffalo Soldier regiments composed of African-American soldiers under white officers. From Fort Assinniboine in north central Montana

Montana ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota to the east, South Dakota to the southeast, Wyoming to the south, an ...

, he commanded an expedition to the south and southwest that rounded up and deported a large number of Cree Indians to Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

.

West Point instructor

In 1897, Pershing was appointed to the West Point tactical staff as an instructor, where he was assigned to Cadet Company A. Because of his strictness and rigidity, Pershing was unpopular with the cadets, who took to calling him "

In 1897, Pershing was appointed to the West Point tactical staff as an instructor, where he was assigned to Cadet Company A. Because of his strictness and rigidity, Pershing was unpopular with the cadets, who took to calling him "Nigger

In the English language, ''nigger'' is a racial slur directed at black people. Starting in the 1990s, references to ''nigger'' have been increasingly replaced by the euphemistic contraction , notably in cases where ''nigger'' is Use–menti ...

Jack" because of his service with the 10th Cavalry.Vandiver v.1, p.171

During the course of his tour at the Academy

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of tertiary education. The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 386 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the go ...

, this epithet softened to "Black Jack," although, according to Vandiver, "the intent remained hostile." Still, this nickname stuck with Pershing for the rest of his life, and was known to the public as early as 1917.

Spanish– and Philippine–American wars

At the start of theSpanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

, First Lieutenant Pershing was the regimental quartermaster for the 10th Cavalry. His duties as quartermaster had him unloading supplies at Daiquiri Cuba on June 24. He missed the Battle of Las Guasimas

The Battle of Las Guasimas of June 24, 1898 was a Spanish rearguard action by Major General Antero Rubín against advancing columns led by Major General Joseph Wheeler, "Fighting Joe" Wheeler and the first land engagement of the Spanish–Ameri ...

that was fought that same day but arrived at the battle site late in the afternoon of June 24. He fought on Kettle and San Juan Hills in Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, and was cited for gallantry. Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

, who also participated in those battles, said that "Captain Pershing is the coolest man under fire I ever saw in my life." In 1919, Pershing was awarded the Silver Citation Star

The Citation Star was a United States Department of War, Department of War personal valor decoration issued as a United States military award devices, ribbon device which was first established by the United States Congress on July 9, 1918 (Bulleti ...

for these actions, and in 1932 the award was upgraded to the Silver Star

The Silver Star Medal (SSM) is the United States Armed Forces' third-highest military decoration for valor in combat. The Silver Star Medal is awarded primarily to members of the United States Armed Forces for gallantry in action against a ...

decoration. A commanding officer here commented on Pershing's calm demeanor under fire, saying he was "cool as a bowl of cracked ice."Boot, p. 191 Pershing also served with the 10th Cavalry during the siege and surrender of Santiago de Cuba.

Pershing was commissioned as a major of United States Volunteers

United States Volunteers also known as U.S. Volunteers, U.S. Volunteer Army, or other variations of these, were military volunteers called upon during wartime to assist the United States Army but who were separate from both the Regular Army (United ...

on August 26, 1898, and assigned as an ordnance officer. In March 1899, after suffering from malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

, Pershing was put in charge of the Office of Customs and Insular Affairs which oversaw occupation forces in territories gained in the Spanish–American War, including Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, Puerto Rico

; abbreviated PR), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is a Government of Puerto Rico, self-governing Caribbean Geography of Puerto Rico, archipelago and island organized as an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territo ...

, the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

, and Guam

Guam ( ; ) is an island that is an Territories of the United States, organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. Guam's capital is Hagåtña, Guam, Hagåtña, and the most ...

. He was honorably discharged from the volunteers and reverted to his permanent rank of first lieutenant on May 12, 1899. He was again commissioned as a major of Volunteers on June 6, 1899, this time as an assistant adjutant

Adjutant is a military appointment given to an Officer (armed forces), officer who assists the commanding officer with unit administration, mostly the management of “human resources” in an army unit. The term is used in French-speaking armed ...

.

When the Philippine–American War

The Philippine–American War, known alternatively as the Philippine Insurrection, Filipino–American War, or Tagalog Insurgency, emerged following the conclusion of the Spanish–American War in December 1898 when the United States annexed th ...

began, Pershing reported to Manila on August 17, 1899, was assigned to the Department of Mindanao

Mindanao ( ) is the List of islands of the Philippines, second-largest island in the Philippines, after Luzon, and List of islands by population, seventh-most populous island in the world. Located in the southern region of the archipelago, the ...

and Jolo

Jolo () is a volcanic island in the southwest Philippines and the primary island of the province of Sulu, on which the capital of the same name is situated. It is located in the Sulu Archipelago, between Borneo and Mindanao, and has a populatio ...

, and commanded efforts to suppress the Filipino Insurrection. On November 27, 1900, Pershing was appointed adjutant general of his department and served in this posting until March 1, 1901. He was cited for bravery for actions on the Cagayan River

The Cagayan River, also known as the Río Grande de Cagayán, is the longest river and the largest river by discharge volume of water in the Philippines. It has a total length of approximately and a drainage basin covering . It is located in ...

while attempting to destroy a Philippine stronghold at Macajambos (or Macahambus).

Pershing wrote in his autobiography that "The bodies Moro outlaws">Moro_people.html" ;"title="f some Moro people">Moro outlawswere publicly buried in the same grave with a dead pig." This treatment was used against captured ''juramentado'' so that the superstitious Moro would believe they would be going to hell. Pershing added that "it was not pleasant [for the Army] to have to take such measures".Pershing, John (2013''My Life Before the World War, 1860–1917: A Memoir''

, pages 284–85 Lexington, Kentucky:

University Press of Kentucky

The University Press of Kentucky (UPK) is the scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth of Kentucky, and was organized in 1969 as successor to the University of Kentucky Press. The university had sponsored scholarly publication since 1943. In 194 ...

. Quote: "... the commanding office, Colonel Frank West, had seen the attack and called out the guard, and before the man could kill anyone else he was shot dead in his tracks. These ''juramentado'' attacks were materially reduced in number by a practice the army had already adopted, one that Muhhamadans held in abhorrence. The bodies were publicly buried in the same grave with a dead pig. It was not pleasant to have to take such measures, but the prospect of going to hell instead of heaven sometimes deterred the would-be assassins." A footnote in the 2013 edition cites a letter from Maj. Gen. J. Franklin Bell to Pershing: "Of course there is nothing to be done, but I understand it has long been a custom to bury (insurgents) with pigs when they kill Americans. I think this a good plan, for if anything will discourage the (insurgents) it is the prospect of going to hell instead of to heaven. You can rely on me to stand by you in maintaining this custom. It is the only possible thing we can do to discourage crazy fanatics." Historians do not believe that Pershing was directly involved with such incidents, or that he personally gave such orders to his subordinates. Letters and memoirs from soldiers describing events similar to this do not have credible evidence of Pershing having been personally involved.Horton, Alex (August 18, 2017"Trump said to study General Pershing. Here's what the president got wrong"

''

The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'', locally known as ''The'' ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'' or ''WP'', is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C., the national capital. It is the most widely circulated newspaper in the Washington m ...

''Qiu, Linda (August 18, 2017"Study Pershing, Trump Said. But the Story Doesn't Add Up"

''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' Military historian B.H. Liddell Hart wrote that, on the contrary, Pershing's conduct toward the Moros was notable for its "unexpected sympathy," and for the fact that, because of Pershing's conscious effort to interact with and understand them, "he could negotiate with the Moros without the intervention of an interpreter."

On June 30, 1901, Pershing was honorably discharged from the Volunteers and he reverted to the rank of captain in the Regular Army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the following:

* a ...

, to which he had been promoted on February 2, 1901. He served with the 1st Cavalry Regiment in the Philippines. He later was assigned to the 15th Cavalry Regiment, serving as an intelligence officer and participating in actions against the Moros. He was cited for bravery at Lake Lanao. In June 1901, he served as commander of Camp Vicars in Lanao, Philippines, after the previous camp commander was promoted to brigadier general.

Rise to general

In June 1903, Pershing was ordered to return to the United States. PresidentTheodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

, taken by Pershing's ability, petitioned the Army General Staff to promote Pershing to colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

. At the time, Army officer promotions were based primarily on seniority rather than merit, and although there was widespread acknowledgment that Pershing should serve as a colonel, the Army General Staff declined to change their seniority-based promotion tradition just to accommodate Pershing. They would not consider a promotion to lieutenant colonel or even major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

. This angered Roosevelt, but since the President could only name and promote army officers in the generals' ranks, his options for recognizing Pershing through promotion were limited.

In 1904, Pershing was assigned as the Assistant Chief of Staff of the Southwest Army Division stationed at Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

Oklahoma City (), officially the City of Oklahoma City, and often shortened to OKC, is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Oklahoma, most populous city of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The county seat ...

. In October 1904, he began attendance at the Army War College, and then was ordered to Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, for "general duties unassigned."

Since Roosevelt could not yet promote Pershing, he petitioned the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

to authorize a diplomatic posting, and Pershing was stationed as military attaché

A military attaché or defence attaché (DA),Defence Attachés

''Geneva C ...

in ''Geneva C ...

Tokyo

Tokyo, officially the Tokyo Metropolis, is the capital of Japan, capital and List of cities in Japan, most populous city in Japan. With a population of over 14 million in the city proper in 2023, it is List of largest cities, one of the most ...

after his January 1905 War College graduation. Also in 1905, Pershing married Helen Frances Warren, the daughter of powerful U.S. Senator Francis E. Warren, a Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

Republican who served at different times as chairman of the Military Affairs and Appropriations Committees. This union with the daughter of a powerful politician who had also received the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, military decoration and is awarded to recognize American United States Army, soldiers, United States Navy, sailors, Un ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

continued to aid Pershing's career even after his wife died in 1915.

After serving as an observer in the Russo-Japanese War attached to General Kuroki Tamemoto's Japanese First Army in Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

from March to September, Pershing returned to the United States in the fall of 1905. President Roosevelt employed his presidential prerogative and nominated Pershing as a brigadier general, a move of which Congress approved. In skipping three ranks and more than 835 officers senior to him, the promotion gave rise to accusations that Pershing's appointment was the result of political connections and not military abilities. However, several other junior officers were similarly advanced to brigadier general ahead of their peers and seniors, including Albert L. Mills (captain), Tasker H. Bliss

Tasker Howard Bliss (December 31, 1853 – November 9, 1930) was a United States Army officer who served as Chief of Staff of the United States Army during World War I, from September 22, 1917, until May 18, 1918. He was also a diplomat involved i ...

(major), and Leonard Wood

Leonard Wood (October 9, 1860 – August 7, 1927) was a United States Army major general, physician, and public official. He served as the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, List of colonial governors of Cuba, Military Governor of Cuba, ...

(captain). Pershing's promotion, while unusual, was not unprecedented, and had the support of many soldiers who admired his abilities.

In 1908, Pershing briefly served as a U.S. military observer in the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

, an assignment which was based in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

. Upon returning to the United States at the end of 1909, Pershing was assigned once again to the Philippines, an assignment in which he served until 1913. While in the Philippines, he served as Commander of Fort McKinley, near Manila

Manila, officially the City of Manila, is the Capital of the Philippines, capital and second-most populous city of the Philippines after Quezon City, with a population of 1,846,513 people in 2020. Located on the eastern shore of Manila Bay on ...

, and also was the governor of the Moro Province. The last of Pershing's four children was born in the Philippines, and during this time he became an Episcopalian

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protes ...

.

In 1913, Pershing was recommended for the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, military decoration and is awarded to recognize American United States Army, soldiers, United States Navy, sailors, Un ...

following his actions at the Battle of Bud Bagsak. He wrote to the Adjutant General to request that the recommendation not be acted on, though the board which considered the recommendation had already voted no before receiving Pershing's letter. In 1922 a further review of this event resulted in Pershing being recommended for the Distinguished Service Cross, but as the Army Chief of Staff Pershing disapproved the action. In 1940 Pershing received the Distinguished Service Cross for his heroism at Bud Bagsak, with President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

presenting it in a ceremony timed to coincide with Pershing's 80th birthday.

During this period Pershing's reputation for both stern discipline and effective leadership continued to grow, with one experienced old soldier under his command later saying Pershing was an " S.O.B." and that he hated Pershing's guts, but that "as a soldier, the ones then and the ones now couldn't polish his (Pershing's) boots."

Pancho Villa and Mexico

On December 20, 1913, Pershing received orders to take command of the 8th Brigade at thePresidio

A presidio (''jail, fortification'') was a fortified base established by the Spanish Empire mainly between the 16th and 18th centuries in areas under their control or influence. The term is derived from the Latin word ''praesidium'' meaning ''pr ...

in San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

. With tensions running high on the border between the United States and Mexico because of the Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution () was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from 20 November 1910 to 1 December 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It saw the destruction of the Federal Army, its ...

, the brigade was deployed to Fort Bliss, Texas, on April 24, 1914, arriving there on the 27th.

Death of wife Frances and daughters

After a year at Fort Bliss, Pershing decided to take his family there. The arrangements were almost complete, when on the morning of August 27, 1915, he received a telegram informing him of a house fire at thePresidio

A presidio (''jail, fortification'') was a fortified base established by the Spanish Empire mainly between the 16th and 18th centuries in areas under their control or influence. The term is derived from the Latin word ''praesidium'' meaning ''pr ...

in San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, where a lacquered floor ignited; the flames rapidly spread, resulting in the smoke inhalation deaths of his wife, Frances Warren Pershing and three young daughters: Mary Margaret, age 3; Anne Orr, age 7; and Helen, age 8. Only his 6-year-old son, Warren, survived. After the funerals at Lakeview Cemetery in Cheyenne, Wyoming

Cheyenne ( or ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Wyoming, most populous city of the U.S. state of Wyoming. It is the county seat of Laramie County, Wyoming, Laramie County, with 65,132 reside ...

, Pershing returned to Fort Bliss with his son, Warren, and his sister, May, and resumed his duties as commanding officer.

Commander of Villa expedition

On March 15, 1916, Pershing led an expedition into Mexico to capturePancho Villa

Francisco "Pancho" Villa ( , , ; born José Doroteo Arango Arámbula; 5 June 1878 – 20 July 1923) was a Mexican revolutionary and prominent figure in the Mexican Revolution. He was a key figure in the revolutionary movement that forced ...

. This expedition was ill-equipped and hampered by a lack of supplies due to the breakdown of the Quartermaster Corps

Following is a list of quartermaster corps, military units, active and defunct, with logistics duties:

* Egyptian Army Quartermaster Corps - see Structure of the Egyptian Army

* Hellenic Army Quartermaster Corps (''Σώμα Φροντιστών ...

. Although there had been talk of war on the border for years, no steps had been taken to provide for the handling of supplies for an expedition. Despite this and other hindrances, such as the lack of aid from the former Mexican government, and their refusal to allow American troops to transport troops and supplies over their railroads, Pershing organized and commanded the Mexican Punitive Expedition, a combined armed force of 10,000 men that penetrated into chaotic Mexico. They routed Villa's revolutionaries, but failed to capture him.

World War I

At the start of the United States' involvement in World War I, PresidentWoodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

considered mobilizing an army to join the fight. Frederick Funston

Frederick Funston (November 9, 1865 – February 19, 1917), also known as Fighting Fred Funston, was a General officer, general in the United States Army, best known for his roles in the Spanish–American War and the Philippine–American ...

, Pershing's superior in Mexico, was being considered for the top billet as the Commander of the American Expeditionary Forces

The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) was a formation of the United States Armed Forces on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front during World War I, composed mostly of units from the United States Army, U.S. Army. The AEF was establis ...

(AEF) when he died suddenly from a heart attack on February 19, 1917. Pershing was the most likely candidate other than Funston, and following America's entrance into the war in May, Wilson briefly interviewed Pershing, and then selected him for the command. He was officially installed in the position on May 10, 1917, and held the post until 1918. Pershing chose Chaumont, France as the AEF headquarters. On October 6, 1917, Pershing, then a major general, was promoted to full general in the National Army. He bypassed the three star rank of lieutenant general, and was the first full general since Philip Sheridan in 1888.

As AEF commander, Pershing was responsible for the organization, training, and supply of a combined professional and draft Army and National Guard force that eventually grew from 27,000 inexperienced men to two field armies, with a third forming as the war ended, totaling over two million soldiers. Pershing was keenly aware of logistics, and worked closely with AEF's Services of Supply (SOS). The new agency performed poorly under generals Richard M. Blatchford

Richard Milford Blatchford (August 17, 1859 – August 31, 1934) was a career officer in the United States Army. A veteran of the Spanish–American War, Philippine–American War, Pancho Villa Expedition, and World War I, he attained the rank ...

and Francis Joseph Kernan; finally in 1918 James Harbord took control and got the job done. Pershing also worked with Colonel Charles G. Dawes—whom he had befriended in Nebraska and who had convinced him not to give up the army for a legal career—to establish an Interallied coordination Board, the Military Board of Allied Supply.

Pershing exercised significant control over his command, with a full delegation of authority from Wilson and Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Newton D. Baker. Baker, cognizant of the endless problems of domestic and allied political involvement in military decision making in wartime, gave Pershing unmatched authority to run his command as he saw fit. In turn, Pershing exercised his prerogative carefully, not engaging in politics or disputes over government policy that might distract him from his military mission. While earlier a champion of the African-American soldier, he did not advocate their full participation on the battlefield, understanding the general racial attitudes of white Americans.

George C. Marshall served as one of Pershing's top assistants during and after the war. Pershing's initial chief of staff was James Harbord, who later took a combat command but worked as Pershing's closest assistant for many years and remained extremely loyal to him.

After departing from Fort Jay

Fort Jay is a coastal bastion fort and the name of a former United States Army post on Governors Island in New York Harbor, within New York City. Fort Jay is the oldest existing defensive structure on the island, and was named for John Jay, a m ...

at Governors Island

Governors Island is a island in New York Harbor, within the Boroughs of New York City, New York City borough of Manhattan. It is located approximately south of Manhattan Island, and is separated from Brooklyn to the east by the Buttermilk ...

in New York Harbor

New York Harbor is a bay that covers all of the Upper Bay. It is at the mouth of the Hudson River near the East River tidal estuary on the East Coast of the United States.

New York Harbor is generally synonymous with Upper New York Bay, ...

under top secrecy on May 28, 1917, aboard the , Pershing arrived in France in June 1917. In a show of American presence, part of the 16th Infantry Regiment marched through Paris shortly after his arrival. Pausing at the tomb of Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette, Marquis de La Fayette (; 6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (), was a French military officer and politician who volunteered to join the Conti ...

, he was reputed to have uttered the famous line "Lafayette, we are here," a line spoken, in fact, by his aide, Colonel Charles E. Stanton. American forces were deployed in France in the autumn of 1917.

In September 1917, the French government commissioned a portrait of Pershing by 23-year-old Romanian artist Micheline Resco. Pershing removed the stars and flag from his car and sat up front with his chauffeur while traveling from his AEF headquarters to visit her by night in her apartment on the rue Descombes. Their friendship continued for the rest of his life. In 1946, at 85, Pershing secretly wed Resco in his Walter Reed Hospital apartment. Resco was 35 years his junior.

Battle of Hamel

For the first time in American history, Pershing allowed American soldiers to be under the command of a foreign power. In late June, General Sir Henry Rawlinson, commanding the British Fourth Army, suggested to Australian Lieutenant General

For the first time in American history, Pershing allowed American soldiers to be under the command of a foreign power. In late June, General Sir Henry Rawlinson, commanding the British Fourth Army, suggested to Australian Lieutenant General John Monash

General (Australia), General Sir John Monash (; 27 June 1865 – 8 October 1931) was an Australian civil engineer and military commander of the World War I, First World War. He commanded the 13th Brigade (Australia), 13th Infantry Brigade befor ...

that American involvement in a set-piece attack alongside the experienced Australians in the upcoming Battle of Hamel would both give the American troops experience and also strengthen the Australian battalions by an additional company each. On June 29, Major General George Bell Jr., commanding the American 33rd Division, selected two companies each from the 131st and 132nd Infantry Regiments of the 66th Brigade. Monash had been promised ten companies of American troops and on June 30 the remaining companies of the 1st and 2nd battalions of the 131st regiment were sent. Each American platoon was attached to a First Australian Imperial Force

The First Australian Imperial Force (1st AIF) was the main Expeditionary warfare, expeditionary force of the Australian Army during the First World War. It was formed as the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) following United Kingdom of Great Bri ...

company, but there was difficulty in integrating the American platoons (which numbered 60 men) among the Australian companies of 100 men. This difficulty was overcome by reducing the size of each American platoon by one-fifth and sending the troops thus removed, which numbered 50 officers and men, back to battalion reinforcement camps.

The day before the attack was scheduled to commence, Pershing learned of the plan and ordered the withdrawal of six American companies.Nunan, Peter (2000). "Diggers' Fourth of July". ''Military History''. 17 (3): 26–32, 80. While a few Americans, such as those attached to the 42nd Battalion, disobeyed the order, the majority, although disappointed, moved back to the rear. This meant that battalions had to rearrange their attack formations and caused a serious reduction in the size of the Allied force. For example, the 11th Brigade was now attacking with 2,200 men instead of 3,000.Bean, C.E.W (1942). The Australian Imperial Force in France during the Allied Offensive, 1918. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Volume VI. Sydney, New South Wales: Angus and Robertson. There was a further last-minute call for the removal of all American troops from the attack, but Monash, who had chosen July 4 as the date of the attack out of "deference" to the US troops, protested to Rawlinson and received support from Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, commander of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). The four American companies that had joined the Australians during the assault were withdrawn from the line after the battle and returned to their regiments, having gained valuable experience. Monash sent the 33rd Division's commander, Bell, his personal thanks, praising the Americans' gallantry, while Pershing set out explicit instructions to ensure that US troops would not be employed in a similar manner again (except as described below).

African American units

Undercivilian control of the military

Civil control of the military is a doctrine in military science, military and political science that places ultimate command responsibility, responsibility for a country's Grand strategy, strategic decision-making in the hands of the state's c ...

, Pershing adhered to the racial policies of President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

, Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Newton D. Baker, and southern Democrats who promoted the "separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protectio ...

" doctrine. African-American " Buffalo Soldiers" units were not allowed to participate with the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) during the war, but experienced non-commissioned officer

A non-commissioned officer (NCO) is an enlisted rank, enlisted leader, petty officer, or in some cases warrant officer, who does not hold a Commission (document), commission. Non-commissioned officers usually earn their position of authority b ...

s were provided to other segregated black units for combat servicesuch as the 317th Engineer Battalion. The American Buffalo Soldiers of the 92nd and 93rd Infantry Divisions were the first American soldiers to fight in France in 1918, but they did so under French command as Pershing had detached them from the AEF to get them into action. Most regiments of the 92nd and all of the 93rd would continue to fight under French command for the duration of the war.

Full American participation

Organization

When General Pershing met General Pétain at Compiègne at 10:45pm on the evening of March 25, 1918, Pétain told him he had few reserves left to stop the

When General Pershing met General Pétain at Compiègne at 10:45pm on the evening of March 25, 1918, Pétain told him he had few reserves left to stop the German Spring Offensive

The German spring offensive, also known as ''Kaiserschlacht'' ("Kaiser's Battle") or the Ludendorff offensive, was a series of German Empire, German attacks along the Western Front (World War I), Western Front during the World War I, First Wor ...

on the Western Front. In response, Pershing said he would waive the idea of forming a separate American I Corps, and put all available American divisions at Pétain's disposal. The message was repeated to General Foch on March 28, after Foch assumed command of all allied armies. Most of these divisions were sent south to relieve French divisions, which were transported to the fight in Flanders.

By early 1918, entire divisions were beginning to serve on the front lines alongside French troops. Although Pershing desired that the AEF fight as units under American command rather than being split up by battalions to augment British and French regiments and brigades, the 27th and 30th Divisions, grouped under II Corps command, were loaned during the desperate days of spring 1918, and fought with the British Fourth Army under General Rawlinson until the end of the war, taking part in the breach of the Hindenburg Line

The Hindenburg Line (, Siegfried Position) was a German Defense line, defensive position built during the winter of 1916–1917 on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front in France during the First World War. The line ran from Arras to ...

in October.

By May 1918, Pershing had become discontented with Air Service of the American Expeditionary Force, believing staff planning had been inefficient with considerable internal dissension, as well as conflict between its members and those of Pershing's General Staff. Further, aircraft and unit totals lagged far behind those expected. Pershing appointed his former West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

classmate and non-aviator, Major General Mason Patrick

Mason Mathews Patrick (December 13, 1863 – January 29, 1942) was a general officer in the United States Army who led the United States Army Air Service during and after World War I and became the first United States Army Air Corps, Chief of the ...

as the new Chief of Air Service. Considerable house-cleaning of the existing staff resulted from Patrick's appointment, bringing in experienced staff officers to administrate, and tightening up lines of communication.

In October 1918, Pershing saw the need for a dedicated Military Police Corps and the first U.S. Army MP School was established at Autun, France. For this, he is considered the founding father of the United States MPs.

Because of the effects

Effect may refer to:

* A result or change of something

** List of effects

** Cause and effect, an idiom describing causality

Pharmacy and pharmacology

* Drug effect, a change resulting from the administration of a drug

** Therapeutic effect, ...

of trench warfare

Trench warfare is a type of land warfare using occupied lines largely comprising Trench#Military engineering, military trenches, in which combatants are well-protected from the enemy's small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from a ...

on soldiers' feet, in January 1918, Pershing oversaw the creation of an improved combat boot

Combat or tactical boots are military boots designed to be worn by soldiers during combat or combat training, as opposed to during parades and other ceremonial duties. Modern combat boots are designed to provide a combination of grip, ankle ...

, the " 1918 Trench Boot," which became known as the "Pershing Boot" upon its introduction.

Combat

American forces first saw serious action during the summer of 1918, contributing eight large divisions, alongside 24 French ones, at the Second Battle of the Marne. Along with the British Fourth Army's victory at Amiens on August 8, the Allied victory at the Second Battle of the Marne marked the turning point of World War I on the Western Front. In August 1918 theU.S. First Army

First Army is the largest OC/T organization in the U.S. Army, comprising two divisions, ten brigades, and more than 7,500 Soldiers. Its mission is to partner with the U.S. Army National Guard and U.S. Army Reserve to enable leaders and deli ...

had been formed, first under Pershing's direct command (while still in command of the AEF) and then by Lieutenant General Hunter Liggett

Hunter Liggett (March 21, 1857 − December 30, 1935) was a senior United States Army officer. His 42 years of military service spanned the period from the Indian campaigns to the trench warfare of World War I. Additionally, he also identified ...

, when the U.S. Second Army under Lieutenant General Robert Bullard was created in mid-October. After a relatively quick victory at Saint-Mihiel, east of Verdun

Verdun ( , ; ; ; official name before 1970: Verdun-sur-Meuse) is a city in the Meuse (department), Meuse departments of France, department in Grand Est, northeastern France. It is an arrondissement of the department.

In 843, the Treaty of V ...

, some of the more bullish AEF commanders had hoped to push on eastwards to Metz

Metz ( , , , then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle (river), Moselle and the Seille (Moselle), Seille rivers. Metz is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Moselle (department), Moselle Departments ...

, but this did not fit in with the plans of the Allied Supreme Commander, Marshal Ferdinand Foch

Ferdinand Foch ( , ; 2 October 1851 – 20 March 1929) was a French general, Marshal of France and a member of the Académie Française and French Academy of Sciences, Académie des Sciences. He distinguished himself as Supreme Allied Commander ...

, for three simultaneous offensives into the "bulge" of the Western Front (the other two being the French Fourth Army's breach of the Hindenburg Line

The Hindenburg Line (, Siegfried Position) was a German Defense line, defensive position built during the winter of 1916–1917 on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front in France during the First World War. The line ran from Arras to ...

and an Anglo-Belgian offensive, led by General Sir Herbert Plumer's British Second Army

The British Second Army was a Field Army active during the World War I, First and World War II, Second World Wars. During the First World War the army was active on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front throughout most of the war and later ...

, in Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

). Instead, the AEF was required to redeploy and aided by French tanks, launched a major offensive northward in very difficult terrain at Meuse-Argonne. Initially enjoying numerical odds of eight to one, this offensive eventually engaged 35 or 40 of the 190 or so German divisions on the Western Front, although to put this in perspective, around half the German divisions were engaged on the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) sector at the time.

The offensive was marked by a Pershing failure, specifically his reliance on massed infantry attacks with little artillery support led to high casualty rates in the capturing of three key points. This was despite the AEF facing only second-line German troops after the decision by Erich Ludendorff

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff (; 9 April 1865 – 20 December 1937) was a German general and politician. He achieved fame during World War I (1914–1918) for his central role in the German victories at Battle of Liège, Liège and Battle ...

, the German Chief of Staff, to withdraw to the Hindenburg Line on October 3 – and in notable contrast to the simultaneous British breakthrough of the Hindenburg Line in the north. Pershing was subsequently forced to reorganize the AEF with the creation of the Second Army, and to step down as the commander of the First Army.

When he arrived in Europe, Pershing had openly scorned the slow trench warfare of the previous three years on the Western Front, believing that American soldiers' skill with the rifle would enable them to avoid costly and senseless fighting over a small area of no-man's land. This was regarded as unrealistic by British and French commanders, and (privately) by a number of Americans such as the former Army Chief of Staff General Tasker Bliss and even Liggett. Even German generals were negative, with Erich Ludendorff

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff (; 9 April 1865 – 20 December 1937) was a German general and politician. He achieved fame during World War I (1914–1918) for his central role in the German victories at Battle of Liège, Liège and Battle ...

dismissing Pershing's strategic efforts in the Meuse-Argonne offensive by recalling how "the attacks of the youthful American troops broke down with the heaviest losses". The AEF had performed well in the relatively open warfare of the Second Battle of the Marne, but the eventual American casualties against German defensive positions in the Argonne (roughly 120,000 American casualties in six weeks, against 35 or 40 German divisions) were not noticeably better than those of the Franco-British offensive on the Somme two years earlier (600,000 casualties in four and a half months, versus 50 or so German divisions). More ground was gained, but by this stage of the war the German Army

The German Army (, 'army') is the land component of the armed forces of Federal Republic of Germany, Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German together with the German Navy, ''Marine'' (G ...

was in worse shape than in previous years.

Some writers have speculated that Pershing's frustration at the slow progress through the Argonne was the cause of two incidents which then ensued. First, he ordered the U.S. First Army to take "the honor" of recapturing Sedan, site of the French defeat in 1870; the ensuing confusion (an order was issued that "boundaries were not to be considered binding") exposed American troops to danger not only from the French on their left, but even from one another, as the 1st Division tacked westward by night across the path of the 42nd Division (accounts differ as to whether Brigadier General Douglas MacArthur