General Bradley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

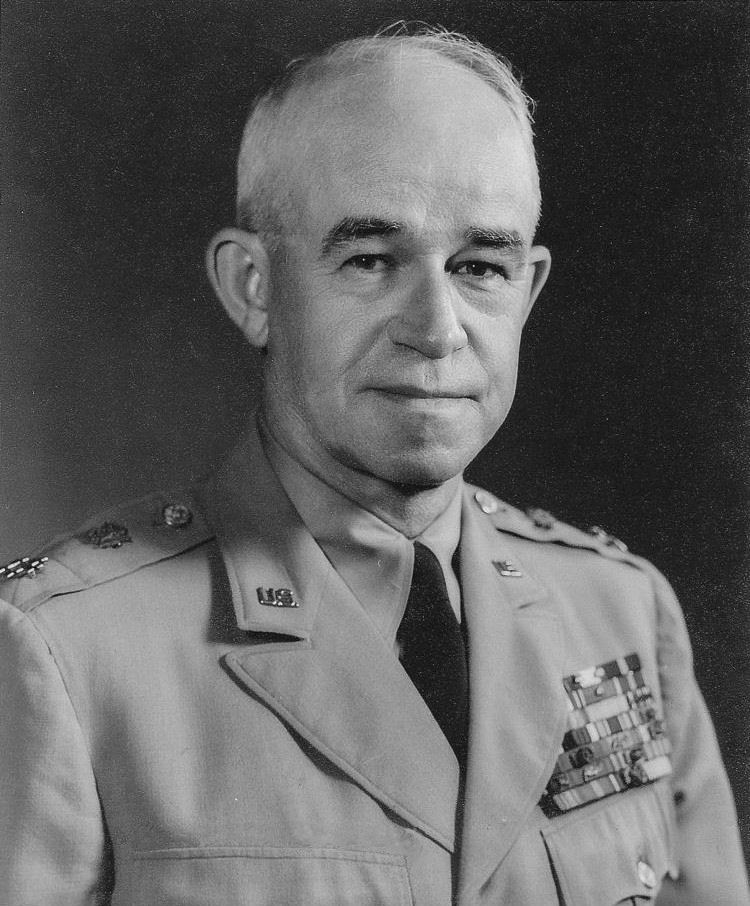

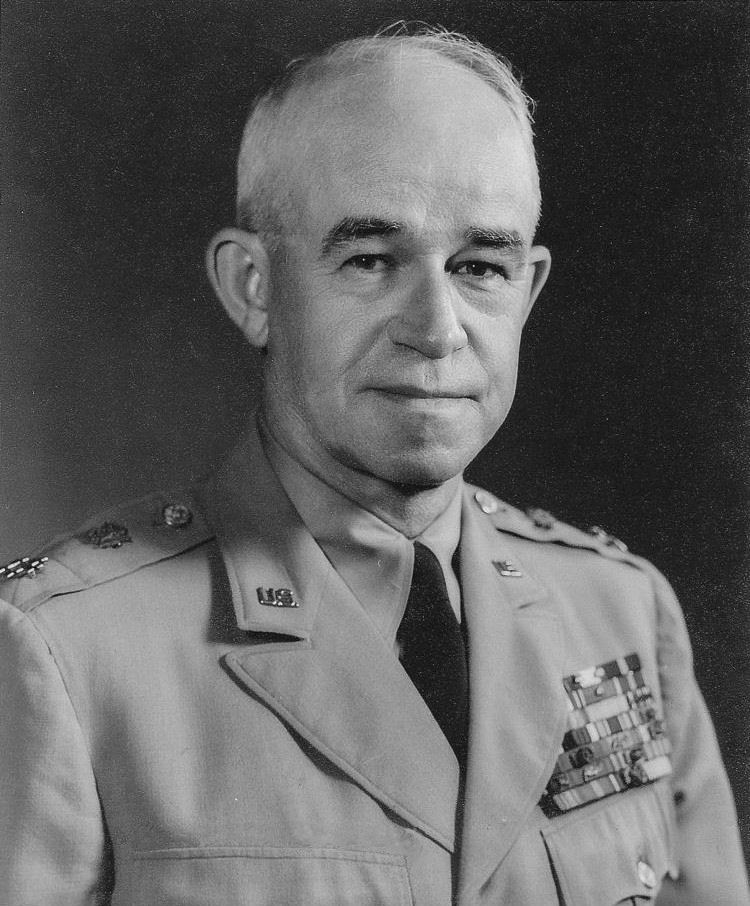

Omar Nelson Bradley (12 February 1893 – 8 April 1981) was a senior

Omar Nelson Bradley, the son of

Omar Nelson Bradley, the son of

p.7

/ref> He was of British ancestry, his ancestors having emigrated from

At West Point, Bradley played three years of varsity baseball including the 1914 team. Every player on that team who remained in the army ultimately became a general. Bradley graduated from West Point in 1915 as part of a class that produced many future generals, and which military historians have called "

At West Point, Bradley played three years of varsity baseball including the 1914 team. Every player on that team who remained in the army ultimately became a general. Bradley graduated from West Point in 1915 as part of a class that produced many future generals, and which military historians have called " From September 1919 until September 1920, Bradley served as assistant professor of military science at South Dakota State College (now University) in

From September 1919 until September 1920, Bradley served as assistant professor of military science at South Dakota State College (now University) in

Many Army officers present at the maneuvers later rose to very senior roles in World War II, including Bradley, Mark Clark,

Many Army officers present at the maneuvers later rose to very senior roles in World War II, including Bradley, Mark Clark,

On 10 September 1943, Bradley transferred to London as commander in chief of the American ground forces preparing to invade France in the spring of 1944. For D-Day, Bradley was chosen to command the

On 10 September 1943, Bradley transferred to London as commander in chief of the American ground forces preparing to invade France in the spring of 1944. For D-Day, Bradley was chosen to command the  On 10 June 1944, four days after the initial

On 10 June 1944, four days after the initial

Eisenhower faced a decision on strategy. Bradley favored an advance into the

Eisenhower faced a decision on strategy. Bradley favored an advance into the

Bradley used the advantage gained in March 1945—after Eisenhower authorized a difficult but successful Allied offensive (on a broad front with British

Bradley used the advantage gained in March 1945—after Eisenhower authorized a difficult but successful Allied offensive (on a broad front with British

Bradley became the Army Chief of Staff in 1948. After assuming command, Bradley found a U.S. military establishment badly in need of reorganization, equipment, and training. As Bradley himself put it, "the Army of 1948 could not fight its way out of a paper bag."Blair, Clay, The Forgotten War: America in Korea, 1950–1953, Naval Institute Press (2003), p. 290

On 11 August 1949, president

Bradley became the Army Chief of Staff in 1948. After assuming command, Bradley found a U.S. military establishment badly in need of reorganization, equipment, and training. As Bradley himself put it, "the Army of 1948 could not fight its way out of a paper bag."Blair, Clay, The Forgotten War: America in Korea, 1950–1953, Naval Institute Press (2003), p. 290

On 11 August 1949, president

Bradley left active military service in August 1953, but remained on active duty by virtue of his rank of General of the Army. He chaired the

Bradley left active military service in August 1953, but remained on active duty by virtue of his rank of General of the Army. He chaired the

Omar Bradley died on 8 April 1981, in New York City of a

Omar Bradley died on 8 April 1981, in New York City of a

* 1 August 1911: Cadet,

* 1 August 1911: Cadet,

Four

Four

Grand Cross,

Grand Cross,  Grand Cross,

Grand Cross,  Grand Cross,

Grand Cross,  Grand Cross,

Grand Cross,  Grand Cross, Order of the Phoenix (Greece)

*

Grand Cross, Order of the Phoenix (Greece)

*  Grand Cross,

Grand Cross,  Honorary Knight Commander of the

Honorary Knight Commander of the  Grand Officer,

Grand Officer,  Grand Officer,

Grand Officer,  Grand Officer,

Grand Officer,  Order of Suvorov First Class (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics)

*

Order of Suvorov First Class (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics)

*  Order of Kutuzov First Class) (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics)

Order of Kutuzov First Class) (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics)

French ''Croix de guerre'' with silver-gilt palm

* War Cross WWII (Belgium) with palm

*

French ''Croix de guerre'' with silver-gilt palm

* War Cross WWII (Belgium) with palm

*

* – Discharged as Major and appointed Captain on 4 November 1922; acts 30 June 1922, and 14 September 1922

** – Bradley's effective date for permanent brigadier general in the Regular Army is earlier than his effective date of promotion for permanent colonel. While serving as a temporary lieutenant general in early 1943, Bradley was notified that he would be promoted to permanent colonel with an effective date of 1 October 1943. At the time, promotions to permanent brigadier and major general had been withheld for more than two years, except for Delos C. Emmons, *** - Pursuant to the 26 June 1948 Act of Congress, 62 Stat. 791, he was authorized to be appointed to the “permanent” grade of General, as opposed to the “temporary” appointment that was standard for 3- and 4-star US officers. As the AUS was, by definition, a temporary component of the U.S. Army, but his appointment as a Regular 4-star general was not effective until 31 January 1949, the historical record is thus unclear as to exactly when the Army executed the permanent appointment authorized by Pub.L. 62 Stat. 791. If not executed retroactively prior to 31 January 1949, then his appointment as a Regular 4-star would be “permanent” as opposed to the standard “temporary” grade. In any case, his subsequent appointment to 5-star grade rendered this appointment to 4-stars as merely a footnote to history.

Chester B. Hansen Collection

– Hansen was the aide of GEN (and GOA) Bradley during and after World War II. US Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle, Pennsylvania

Omar Nelson Bradley, Lt. General FUSAG 12TH AG

– Omar Bradley's D-Day June 6, 1944, Maps restored, preserved and displayed at Historical Registry

The American Presidency Project

* *

, - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Bradley, Omar Nelson 1893 births 1981 deaths American five-star officers United States Army personnel of World War I Army Black Knights baseball players Army Black Knights football players Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Chairmen of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Commanders of the Order of Polonia Restituta Honorary Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath Military personnel from Missouri NATO military personnel People from Moberly, Missouri Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients American recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1939–1945 (France) Recipients of the Defense Distinguished Service Medal Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army) Recipients of the Legion of Merit Recipients of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal Recipients of the Order of Kutuzov, 1st class Recipients of the Order of Suvorov, 1st class Recipients of the Silver Star Chiefs of Staff of the United States Army United States Army Command and General Staff College alumni United States Army War College alumni United States Department of Veterans Affairs officials United States Military Academy alumni United States Army Infantry Branch personnel Writers from Missouri Graduates of the United States Military Academy Class of 1915 Recipients of the Czechoslovak War Cross 1939–1945 American people of British descent United States Army generals of World War II United States Army generals South Dakota State University faculty United States Military Academy faculty United States Army personnel of the Korean War American anti-communists

officer

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," fro ...

of the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

during and after World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, rising to the rank of General of the Army

Army general or General of the army is the highest ranked general officer in many countries that use the French Revolutionary System. Army general is normally the highest rank used in peacetime.

In countries that adopt the general officer fou ...

. He was the first chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) is the presiding officer of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS). The chairman is the highest-ranking and most senior military officer in the United States Armed Forces Chairman: appointment; gra ...

and oversaw the U.S. military's policy-making in the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

.

Born in Randolph County, Missouri

Randolph County is a county in the northern portion of the U.S. state of Missouri. As of the 2020 census, the population was 24,716. Its county seat is Huntsville. The county was organized January 22, 1829, and named for U.S. Representative a ...

, he worked as a boilermaker

A boilermaker is a Tradesman, tradesperson who Metal fabrication, fabricates steels, iron, or copper into boilers and other large containers intended to hold hot gas or liquid, as well as maintains and repairs boilers and boiler systems.Bure ...

before entering the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

at West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

. He graduated from the academy in 1915 alongside Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

as part of "the class the stars fell on

"The class the stars fell on" is an expression used to describe the class of 1915 at the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York. In the United States Army, the insignia reserved for generals is one or more stars. Of the 164 gradu ...

." During World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, he guarded copper mines in Montana

Montana ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota to the east, South Dakota to the southeast, Wyoming to the south, an ...

. After the war, he taught at West Point and served in other roles before taking a position at the War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War

The United States Department of War, also called the War Department (and occasionally War Office in the early years), was the United States Cabinet ...

under General George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (31 December 1880 – 16 October 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army under pres ...

. In 1941, he became commander of the United States Army Infantry School

The United States Army Infantry School is a school located at Fort Benning, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia that is dedicated to training Infantry Branch (United States), infantrymen for service in the United States Army.

Organization

The school ...

.

After the U.S. entry into World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, he oversaw the transformation of the 82nd Infantry Division into the first American airborne division. He received his first front-line command in Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8–16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa whil ...

, serving under General George S. Patton

George Smith Patton Jr. (11 November 1885 – 21 December 1945) was a general in the United States Army who commanded the Seventh Army in the Mediterranean Theater of World War II, then the Third Army in France and Germany after the Alli ...

in North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

. After Patton was reassigned, Bradley commanded II Corps in the Tunisia Campaign

The Tunisian campaign (also known as the battle of Tunisia) was a series of battles that took place in Tunisia during the North African campaign of the Second World War, between Axis and Allied forces from 17 November 1942 to 13 May 1943. The ...

and the Allied invasion of Sicily

The Allied invasion of Sicily, also known as the Battle of Sicily and Operation Husky, was a major campaign of World War II in which the Allies of World War II, Allied forces invaded the island of Sicily in July 1943 and took it from the Axis p ...

. He commanded the First United States Army

First Army is the largest OC/T organization in the U.S. Army, comprising two divisions, ten brigades, and more than 7,500 Soldiers. Its mission is to partner with the U.S. Army National Guard and U.S. Army Reserve to enable leaders and deli ...

during the Invasion of Normandy

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful liberation of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 ( D-Day) with the ...

. After the breakout from Normandy, he took command of the Twelfth United States Army Group

The Twelfth United States Army group, Army Group was the largest and most powerful United States Army formation ever to take to the field, commanding four Field army, field armies at its peak in 1945: First United States Army, United States Army C ...

, which ultimately comprised forty-three divisions and 1.3 million men, the largest body of American soldiers ever to serve under a single field commander.

After the war, Bradley headed the Veterans Administration

The United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is a Cabinet-level executive branch department of the federal government charged with providing lifelong healthcare services to eligible military veterans at the 170 VA medical centers an ...

. He was appointed as Chief of Staff of the United States Army

The chief of staff of the Army (CSA) is a statutory position in the United States Army held by a general officer. As the highest-ranking officer assigned to serve in the Department of the Army, the chief is the principal military advisor and a ...

in 1948 and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) is the presiding officer of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS). The chairman is the highest-ranking and most senior military officer in the United States Armed Forces Chairman: appointment; gra ...

in 1949. In 1950, he was promoted to the rank of General of the Army

Army general or General of the army is the highest ranked general officer in many countries that use the French Revolutionary System. Army general is normally the highest rank used in peacetime.

In countries that adopt the general officer fou ...

, becoming the last of the nine individuals promoted to five-star rank

A five-star rank is the highest military rank in many countries.Oxford English Dictionary (OED), 2nd Edition, 1989. "five" ... "five-star adj., ... (b) U.S., applied to a general or admiral whose badge of rank includes five stars;" The rank is th ...

in the United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the Military, military forces of the United States. U.S. United States Code, federal law names six armed forces: the United States Army, Army, United States Marine Corps, Marine Corps, United States Navy, Na ...

. He was the senior military commander at the start of the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

, and supported President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

's wartime policy of containment

Containment was a Geopolitics, geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''Cordon sanitaire ...

. He was instrumental in persuading Truman to dismiss General Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

in 1951 after MacArthur resisted administration attempts to scale back the war's strategic objectives. Bradley left active duty in 1953 (although remaining on "active retirement" for the next 27 years). He continued to serve in public and business roles until his death in 1981 at age 88.

Early life and education

Omar Nelson Bradley, the son of

Omar Nelson Bradley, the son of schoolteacher

A teacher, also called a schoolteacher or formally an educator, is a person who helps students to acquire knowledge, competence, or virtue, via the practice of teaching.

''Informally'' the role of teacher may be taken on by anyone (e.g. w ...

John Smith Bradley (1868–1908) and his wife Mary Elizabeth (née Hubbard) (1875–1931), was born into poverty in rural Randolph County, Missouri

Randolph County is a county in the northern portion of the U.S. state of Missouri. As of the 2020 census, the population was 24,716. Its county seat is Huntsville. The county was organized January 22, 1829, and named for U.S. Representative a ...

, near Moberly. Bradley was named after Omar D. Gray, a local newspaper editor admired by his father, and a local physician, James Nelson.Axelrodp.7

/ref> He was of British ancestry, his ancestors having emigrated from

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

to Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

in the mid-1700s. He attended at least eight country schools where his father taught. The elder Bradley never earned more than $40 a month in his lifetime, while he was a schoolteacher and sharecropper, the latter with the aid of all the family. They never owned a wagon, a horse, or a mule. When Omar was 15, his father died; he credited his father with passing on to him his love of books, baseball and shooting.

His mother moved with him to Moberly, where she remarried. Bradley graduated from Moberly High School

Moberly is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Charles Moberly (1907–1996), English cricketer

*Charles Frederic Moberly Bell (1847–1911), British editor of ''The Times''

*Clarence Moberly (1838–1902), Canadian civil enginee ...

in 1910. He was an outstanding student and athlete who was chosen captain of both the baseball and track teams.

Bradley was working as a 17-cents-an-hour (equal

to $ today) boilermaker

A boilermaker is a Tradesman, tradesperson who Metal fabrication, fabricates steels, iron, or copper into boilers and other large containers intended to hold hot gas or liquid, as well as maintains and repairs boilers and boiler systems.Bure ...

at the Wabash Railroad

The Wabash Railroad was a Class I railroad that operated in the mid-central United States. It served a large area, including track in the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Michigan, and Missouri and the province of Ontario. Its primary con ...

when he was encouraged by his Sunday school teacher at Central Christian Church in Moberly to take the entrance examination for the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

(USMA) at West Point, New York

West Point is the oldest continuously occupied military post in the United States. Located on the Hudson River in New York (state), New York, General George Washington stationed his headquarters in West Point in the summer and fall of 1779 durin ...

. Bradley had been saving his money to enter the University of Missouri

The University of Missouri (Mizzou or MU) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Columbia, Missouri, United States. It is Missouri's largest university and the flagship of the four-campus Univers ...

in Columbia, where he intended to study law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a science and as the ar ...

. He finished second in the West Point placement exams, held at Jefferson Barracks Military Post

The Jefferson Barracks Military Post is located on the Mississippi River at Lemay, Missouri, south of St. Louis. It was an important and active U.S. Army installation from 1826 through 1946. It is the oldest operating U.S. military installat ...

in St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an Independent city (United States), independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Miss ...

. The first-place winner was unable to accept the Congressional appointment, however, and the nomination was passed to Bradley in August 1911.

While Bradley was attending the academy, his devotion to sports prevented him from excelling academically; but he still ranked 44th in a class of 164. He was a baseball star and often played on semi-pro teams for no remuneration (to ensure his eligibility as an amateur to represent the academy). He was considered one of the most outstanding college players in the nation during his junior and senior seasons at West Point, noted as both a power hitter and an outfielder, with one of the best arms in his day. He rejected multiple offers to play professional baseball, choosing to pursue his Army career.

While stationed at West Point as an instructor, in 1923 Bradley became a Freemason

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

. He became a member of the West Point Lodge #877, Highland Falls, New York

Highland Falls, formerly named Buttermilk Falls, is a village in Orange County, New York, United States. The population was 3,684 at the 2020 census. The village was founded in 1906. It is part of the Kiryas Joel– Poughkeepsie– Newbu ...

and continued with them until his death.

Bradley married Mary Quayle (1892–1965), who had grown up across the street from him in Moberly. Her father, the town's popular police chief, had died when she was young. The pair attended Central Christian Church and Moberly High School together. On the cover of the 1910 Moberly High School yearbook, ''The Salutar,'' they were shown across from each other, although they did not date during those years. His picture bore the description "calculative" and hers "linguistic." She earned a college degree in education.

West Point and early military career

At West Point, Bradley played three years of varsity baseball including the 1914 team. Every player on that team who remained in the army ultimately became a general. Bradley graduated from West Point in 1915 as part of a class that produced many future generals, and which military historians have called "

At West Point, Bradley played three years of varsity baseball including the 1914 team. Every player on that team who remained in the army ultimately became a general. Bradley graduated from West Point in 1915 as part of a class that produced many future generals, and which military historians have called "the class the stars fell on

"The class the stars fell on" is an expression used to describe the class of 1915 at the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York. In the United States Army, the insignia reserved for generals is one or more stars. Of the 164 gradu ...

". Bradley's cullum number is 5356. There were ultimately 59 future general officer

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

s in that graduating class, among whom Bradley and Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

attained the rank of General of the Army

Army general or General of the army is the highest ranked general officer in many countries that use the French Revolutionary System. Army general is normally the highest rank used in peacetime.

In countries that adopt the general officer fou ...

. Eisenhower was elected in 1952 in a landslide victory as 34th President of the United States. Among the numerous others who became generals were Joseph T. McNarney

Joseph Taggart McNarney (28 August 1893 – 1 February 1972) was a Four-star rank, four-star General (United States), general in the United States Army Air Forces, United States Army and in the United States Air Force, who served as Military Go ...

, Henry Aurand

Lieutenant general (United States), Lieutenant General Henry Spiese Aurand (April 21, 1894June 18, 1980) was a United States Army career officer. He was a veteran of World War I, World War II, and the Korean War. A graduate of the United States M ...

, James Van Fleet

General (United States), General James Alward Van Fleet (19 March 1892 – 23 September 1992) was a United States Army officer who served during World War I, World War II and the Korean War. Van Fleet was a native of New Jersey, who was raised i ...

, Stafford LeRoy Irwin, John W. Leonard, Joseph May Swing, Paul J. Mueller, Charles W. Ryder, Leland Hobbs, Vernon Prichard, John B. Wogan, Roscoe B. Woodruff, John French Conklin, Walter W. Hess, and Edwin A. Zundel.

Bradley was commissioned as a second lieutenant into the Infantry Branch of the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

and was first assigned to the 14th Infantry Regiment.

He served on the Mexico–United States border

The international border separating Mexico and the United States extends from the Pacific Ocean in the west to the Gulf of Mexico in the east. The border traverses a variety of terrains, ranging from urban areas to deserts. It is the List of ...

in 1915, defending it from incursions due to the Mexican civil war. On 1 July 1916 he was promoted to first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a se ...

.

When the United States entered World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in April 1917 (see the American entry into World War I

The United States entered into World War I on 6 April 1917, more than two and a half years after the war began in Europe. Apart from an Anglophile element urging early support for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, British and an a ...

), he was promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

on 15 May and sent to guard the Butte, Montana

Butte ( ) is a consolidated city-county and the county seat of Silver Bow County, Montana, United States. In 1977, the city and county governments consolidated to form the sole entity of Butte-Silver Bow. The city covers , and, according to the 2 ...

copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

mines, considered of strategic importance. Bradley was promoted to the temporary rank of major in June 1918 and assigned to command the second battalion of the 14th Infantry, joined the 19th Division in August 1918, which was scheduled for European deployment, but the influenza pandemic

An influenza pandemic is an epidemic of an influenza virus that spreads across a large region (either multiple continents or worldwide) and infects a large proportion of the population. There have been five major influenza pandemics in the l ...

and the armistice with Germany {{Short description, none

This is a list of armistices signed by the German Empire (1871–1918) or Nazi Germany (1933–1945). An armistice is a temporary agreement to cease hostilities. The period of an armistice may be used to negotiate a peace t ...

on 11 November 1918, that fall intervened.

From September 1919 until September 1920, Bradley served as assistant professor of military science at South Dakota State College (now University) in

From September 1919 until September 1920, Bradley served as assistant professor of military science at South Dakota State College (now University) in Brookings, South Dakota

Brookings is a city in and the county seat of Brookings County, South Dakota, Brookings County, South Dakota, United States. The population was 23,377 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of cities in South Dakota, fo ...

.

During the difficult period between the wars

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

, he taught and studied. From 1920 to 1924, Bradley taught mathematics at West Point. He was promoted to major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

in 1924 and took the advanced infantry course at Fort Benning, Georgia

Fort Benning (named Fort Moore from 2023–2025) is a United States Army post in the Columbus, Georgia area. Located on Georgia's border with Alabama, Fort Benning supports more than 120,000 active-duty military, family members, reserve compone ...

. After brief duty in Hawaii, Bradley was selected to study at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth, Kansas, Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., an ...

, Kansas

Kansas ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the west. Kansas is named a ...

in 1928–29. Upon graduating, he served as an instructor in tactics at the U.S. Army Infantry School. While Bradley was serving in this assignment, the school's assistant commandant, Lieutenant Colonel George C. Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (31 December 1880 – 16 October 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army under presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. ...

, described Bradley as "quiet, unassuming, capable, with sound common sense. Absolute dependability. Give him a job and forget it."

From 1929, Bradley taught again at West Point, studying at the U.S. Army War College

The United States Army War College (USAWC) is a United States Army, U.S. Army staff college in Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, with a Carlisle, Pennsylvania, Carlisle postal address, on the 500-acre (2 km2) campus of the historic Carlisle B ...

in 1934. Bradley was promoted to lieutenant colonel on 26 June 1936 and worked at the War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War

The United States Department of War, also called the War Department (and occasionally War Office in the early years), was the United States Cabinet ...

; after 1938 he was directly reporting to U.S. Army Chief of Staff

The chief of staff of the Army (CSA) is a statutory position in the United States Army held by a general officer. As the highest-ranking officer assigned to serve in the Department of the Army, the chief is the principal military advisor and a d ...

Marshall.

On 20 February 1941, Bradley was promoted to the (wartime) temporary rank of brigadier general (bypassing the rank of colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

.) (This rank was made permanent by the army in September 1943). The temporary rank was conferred to allow him to command the U.S. Army Infantry School

The United States Army Infantry School is a school located at Fort Benning, Georgia that is dedicated to training infantrymen for service in the United States Army.

Organization

The school is made up of the following components:

* 197th Infan ...

at Fort Benning

Fort Benning (named Fort Moore from 2023–2025) is a United States Army post in the Columbus, Georgia area. Located on Georgia's border with Alabama, Fort Benning supports more than 120,000 active-duty military, family members, reserve compone ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

(he was among the first from his class to reach even a temporary rank of general officer; first was his West Point classmate Luis Esteves, who was promoted Brigadier general in October 1940). While serving in this position he played a key part in developing the officer candidate school model.

Almost a year later, on 15 February 1942, over two months after the American entry into World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Bradley was made a temporary major general (a rank made permanent in September 1944) and soon took command of the 82nd Infantry Division

The 82nd Airborne Division is an airborne infantry division of the United States Army specializing in parachute assault operations into hostile areasSof, Eric"82nd Airborne Division" ''Spec Ops Magazine'', 25 November 2012. Archived from tho ...

(soon to be redesignated as the 82nd Airborne Division) before succeeding Major General James Garesche Ord

Major General James Garesche Ord (October 18, 1886 – April 17, 1960) was a United States Army officer who briefly commanded the 28th Infantry Division and was Chairman of the Joint Brazil–U.S. Defense Commission during World War II.

Early ...

as commander of the 28th Infantry Division in June.

Louisiana Maneuvers

TheLouisiana Maneuvers

The Louisiana Maneuvers were a series of major U.S. Army exercises held from August to September 1941 in northern and west-central Louisiana, an area bounded by the Sabine River to the west, the Calcasieu River to the east, and by the city of ...

were a series of U.S. Army exercises held around Northern

Northern may refer to the following:

Geography

* North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating ...

and Western-Central Louisiana, including Fort Polk

Fort Polk, formerly Fort Johnson, is a United States Army installation located in Vernon Parish, Louisiana, about 10 miles (15 km) east of Leesville and 30 miles (50 km) north of DeRidder in Beauregard Parish.

Named after New Yo ...

, Camp Claiborne

Camp Claiborne was a U.S. Army military camp in the 1930s continuing through World War II located in Rapides Parish in central Louisiana. The camp was under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Eighth Service Command, and included 23,000 acres (93&nbs ...

and Camp Livingston

Camp Livingston was a U.S. Army military camp during World War II. It was located on the border between Rapides and Grant Parishes, near Pineville, north of Alexandria, Louisiana.

History

Camp Livingston was open from 1940 to 1945, and was ...

, in 1940 and 1941. The exercises, which involved some 400,000 troops, were designed to evaluate U.S. training, logistics

Logistics is the part of supply chain management that deals with the efficient forward and reverse flow of goods, services, and related information from the point of origin to the Consumption (economics), point of consumption according to the ...

, doctrine

Doctrine (from , meaning 'teaching, instruction') is a codification (law), codification of beliefs or a body of teacher, teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the essence of teachings in a given branch of knowledge or in a ...

, and commanders. Overall, headquarters were in the Bentley Hotel in Alexandria.

Many Army officers present at the maneuvers later rose to very senior roles in World War II, including Bradley, Mark Clark,

Many Army officers present at the maneuvers later rose to very senior roles in World War II, including Bradley, Mark Clark, Dwight Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

, Walter Krueger

Walter Krueger (26 January 1881 – 20 August 1967) was an American soldier and general officer in the first half of the 20th century. He commanded the Sixth United States Army in the South West Pacific Area during World War II. He rose fro ...

, Lesley J. McNair and George Patton

George Smith Patton Jr. (11 November 1885 – 21 December 1945) was a general in the United States Army who commanded the Seventh Army in the Mediterranean Theater of World War II, then the Third Army in France and Germany after the Alli ...

.

Lieutenant Colonel Bradley was assigned to General Headquarters during the Louisiana Maneuvers but as a courier and observer in the field, he gained invaluable experience for the future. Colonel Bradley assisted in the planning of the maneuvers, and kept the General Staff in Washington, D.C. abreast of the training that was occurring during the Louisiana Maneuvers.

Bradley later said that Louisianans welcomed the soldiers with open arms. Some soldiers even slept in some of the residents' houses. Bradley said it was so crowded in those houses sometimes when the soldiers were sleeping, there would hardly be any walking room. Bradley also said a few of the troops were disrespectful towards the residents' land and crops, and would tear down crops for extra food. However, for the most part, residents and soldiers established good relations.

World War II

Bradley's personal experiences in the war are documented in his award-winning book ''A Soldier's Story,'' published by Henry Holt & Co. in 1951. It was re-released by The Modern Library in 1999. The book is based on an extensive diary maintained by his aide-de-camp, Chester B. Hansen, who ghost-wrote the book using the diary; Hansen's original diary is maintained by the U. S. Army Heritage and Education Center, at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. On 25 March 1942, Bradley, recently promoted to major general, assumed command of the newly activated 82nd Infantry Division. Bradley oversaw the division's transformation into the first American airborne division and took parachute training. In August the division was re-designated as the82nd Airborne Division

The 82nd Airborne Division is an Airborne forces, airborne infantry division (military), division of the United States Army specializing in Paratrooper, parachute assault operations into hostile areasSof, Eric"82nd Airborne Division" ''Spec Ops ...

and Bradley relinquished command to Major General Matthew Ridgway

Matthew Bunker Ridgway (3 March 1895 – 26 July 1993) was a senior officer in the United States Army, who served as Supreme Allied Commander Europe (1952–1953) and the 19th Chief of Staff of the United States Army (1953–1955). Although he ...

, who had been his assistant division commander (ADC).

Bradley then took command of the 28th Infantry Division, which was a National Guard division with soldiers mostly from the state of Pennsylvania.

North Africa and Sicily

Bradley did not receive a front-line command until early 1943, afterOperation Torch

Operation Torch (8–16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa whil ...

, the Allied invasion of French North Africa

French North Africa (, sometimes abbreviated to ANF) is a term often applied to the three territories that were controlled by France in the North African Maghreb during the colonial era, namely Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. In contrast to French ...

. He had been given VIII Corps 8th Corps, Eighth Corps, or VIII Corps may refer to:

* VIII Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French army during the Napoleonic Wars

* VIII Army Corps (German Confederation)

* VIII Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Arm ...

after being succeeded by Lloyd D. Brown as commander of the 28th Division, but instead was sent to North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

to be Eisenhower's front-line troubleshooter. At Bradley's suggestion, II Corps, which had just suffered a great defeat at the Kasserine Pass, was overhauled from top to bottom, and Eisenhower, now the Supreme Allied Commander

Supreme Allied Commander is the title held by the most senior commander within certain multinational military alliances. It originated as a term used by the Allies during World War I, and is currently used only within NATO for Supreme Allied Co ...

of the Allied forces in North Africa, installed Major General George S. Patton

George Smith Patton Jr. (11 November 1885 – 21 December 1945) was a general in the United States Army who commanded the Seventh Army in the Mediterranean Theater of World War II, then the Third Army in France and Germany after the Alli ...

as corps commander in March 1943. Patton requested Bradley as his deputy, but Bradley retained the right to represent Eisenhower as well.

Bradley succeeded Patton as commander of II Corps in April and directed it in the final Tunisian battles of April and May, with Bizerte

Bizerte (, ) is the capital and largest city of Bizerte Governorate in northern Tunisia. It is the List of northernmost items, northernmost city in Africa, located north of the capital Tunis. It is also known as the last town to remain under Fr ...

falling to elements of II Corps on 7 May 1943. The campaign as a whole ended six days later, and with it came the surrender of over 200,000 Axis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

Germans and Italians.

As a result of his excellent performance in the campaign, Bradley was promoted to Brevet lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was norma ...

on 2 June 1943 and continued to command II Corps in the Allied invasion of Sicily

The Allied invasion of Sicily, also known as the Battle of Sicily and Operation Husky, was a major campaign of World War II in which the Allies of World War II, Allied forces invaded the island of Sicily in July 1943 and took it from the Axis p ...

(codenamed Operation Husky). The campaign lasted only a few weeks and, as he had in Tunisia, Bradley continued to impress his superiors, Eisenhower most notably, who wrote to Marshall about Bradley:

Normandy 1944

On 10 September 1943, Bradley transferred to London as commander in chief of the American ground forces preparing to invade France in the spring of 1944. For D-Day, Bradley was chosen to command the

On 10 September 1943, Bradley transferred to London as commander in chief of the American ground forces preparing to invade France in the spring of 1944. For D-Day, Bradley was chosen to command the US First Army

First Army is the largest OC/T organization in the U.S. Army, comprising two divisions, ten brigades, and more than 7,500 Soldiers. Its mission is to partner with the U.S. Army National Guard and U.S. Army Reserve to enable leaders and deliv ...

, which, alongside the British Second Army

The British Second Army was a Field Army active during the World War I, First and World War II, Second World Wars. During the First World War the army was active on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front throughout most of the war and later ...

, commanded by Lieutenant-General Miles Dempsey

General Sir Miles Christopher Dempsey, (15 December 1896 – 5 June 1969) was a senior British Army officer who served in both world wars. During the Second World War he commanded the Second Army in northwest Europe. A highly professional car ...

, made up the 21st Army Group

The 21st Army Group was a British headquarters formation formed during the Second World War. It controlled two field armies and other supporting units, consisting primarily of the British Second Army and the First Canadian Army. Established ...

, commanded by General Sir Bernard Montgomery.

On 10 June 1944, four days after the initial

On 10 June 1944, four days after the initial Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on 6 June 1944 of the Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during the Second World War. Codenamed Operation Neptune and ...

, Bradley and his staff debarked to establish a headquarters ashore. During Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allies of World War II, Allied operation that launched the successful liberation of German-occupied Western Front (World War II), Western Europe during World War II. The ope ...

, he commanded three corps directed at the two American invasion targets, Utah Beach and Omaha Beach

Omaha Beach was one of five beach landing sectors of the amphibious assault component of Operation Overlord during the Second World War.

On June 6, 1944, the Allies of World War II, Allies invaded German military administration in occupied Fra ...

. During July he inspected the modifications made by Curtis G. Culin to Sherman tanks, that led to the Rhino tank

"Rhino tank" (initially called "Rhinoceros") was the American nickname for Allied tanks fitted with "tusks", or bocage cutting devices, during World War II. The British designation for the modifications was Prongs.

In the summer of 1944, during ...

. Later in July, he planned Operation Cobra

Operation Cobra was an offensive launched by the First United States Army under Lieutenant General Omar Bradley seven weeks after the D-Day landings, during the Normandy campaign of World War II. The intention was to take advantage of the dis ...

, the beginning of the breakout from the Normandy beachhead. Operation Cobra called for the use of strategic bombers using huge bomb loads to attack German defensive lines. After several postponements due to weather, the operation began on 25 July 1944, with a short, very intensive bombardment with lighter explosives, designed so as not to create more rubble and craters that would slow Allied progress. Bradley was horrified when 77 planes bombed short and dropped bombs on their own troops, including Lieutenant General Lesley J. McNair:

However, the bombing was successful in knocking out the enemy communication system, rendering German troops confused and ineffective, and opened the way for the ground offensive by attacking infantry. Bradley sent in three infantry divisions—the 9th, 4th

Fourth or the fourth may refer to:

* the ordinal form of the number 4

* ''Fourth'' (album), by Soft Machine, 1971

* Fourth (angle), an ancient astronomical subdivision

* Fourth (music), a musical interval

* ''The Fourth'', a 1972 Soviet drama

...

and 30th—to move in close behind the bombing. The infantry succeeded in cracking the German defenses, opening the way for advances by armored forces commanded by Patton to sweep around the German lines.

As the build-up continued in Normandy, the Third Army was formed under Patton, Bradley's former commander, while Lieutenant General Courtney Hodges

General Courtney Hicks Hodges (5 January 1887 – 16 January 1966) was a decorated senior officer in the United States Army who commanded First U.S. Army in the Western European Campaign of World War II. Hodges was a notable "mustang" officer, ...

, whom Bradley had succeeded as Commandant of the Infantry School, succeeded Bradley in command of the First Army; together, they made up Bradley's new command, the 12th Army Group

The Twelfth United States Army Group was the largest and most powerful United States Army formation ever to take to the field, commanding four field armies at its peak in 1945: First United States Army, Third United States Army, Ninth United Stat ...

. By August, the 12th Army Group had swollen to over 900,000 men and ultimately consisted of four field armies. It was the largest group of American soldiers to ever serve under one field commander.

Falaise pocket

Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

's refusal to allow his army to flee the rapidly advancing Allied pincer movement created an opportunity to trap an entire German Army Group in northern France. After the German attempt to split the US armies at Mortain

Mortain () is a former commune in the Manche department in Normandy in north-western France. On 1 January 2016, it was merged into the new commune of Mortain-Bocage.

Geography

Mortain is situated on a rocky hill rising above the gorge of the ...

(Operation Lüttich

Operation Lüttich (7–13 August 1944) was the codename of the Nazi German counter-attack during the Operation Overlord, which occurred near U.S. positions near Mortain, in northwestern France. ''Lüttich'' is the German name for the city of Li� ...

), Bradley's Army Group and XV Corps became the southern pincer in forming the ''Falaise pocket

The Falaise pocket or battle of the Falaise pocket (; 12–21 August 1944) was the decisive engagement of the Battle of Normandy in the Second World War. Allied forces formed a pocket around Falaise, Calvados, in which German Army Group B, c ...

'', trapping the German Seventh Army and Fifth Panzer Army

5th Panzer Army () was the name of two different German armoured formations during World War II. The first of these was formed in 1942, during the North African campaign and surrendered to the Allies at Tunis in 1943. The army was re-formed in F ...

in Normandy. The northern pincer was formed of Canadian forces, part of British General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Sir Bernard Montgomery's 21st Army Group. On 13 August 1944, concerned that American troops would clash with Canadian forces advancing from the north-west, Bradley overrode Patton's orders for a further push north towards Falaise, while ordering Major General Wade H. Haislip

General (United States), General Wade Hampton Haislip (9 July 1889 – 23 December 1971) was a senior United States Army Officer (armed forces), officer who served in both World War I and World War II, where he led XV Corps (United States), XV ...

's XV Corps to "concentrate for operations in another direction". Any American troops in the vicinity of Argentan

Argentan () is a commune and the seat of two cantons and of an arrondissement in the Orne department in northwestern France. As of 2019, Argentan is the third largest municipality by population in the Orne department.

were ordered to withdraw. This order halted the southern pincer movement of Haislip's XV Corps.Essame, Herbert, ''Patton: As Military Commander'', p. 182 Though Patton protested the order, he obeyed it, leaving an exit—a "trap with a gap"—for the remaining German forces. Around 20,000–50,000 German troops (leaving almost all of their heavy material) escaped through the gap, avoiding encirclement and almost certain destruction. They would be reorganized and rearmed in time to slow the Allied advance into the Netherlands and Germany. Most of the blame for this outcome has been placed on Bradley. Bradley had incorrectly assumed, based on Ultra

Ultra may refer to:

Science and technology

* Ultra (cryptography), the codename for cryptographic intelligence obtained from signal traffic in World War II

* Adobe Ultra, a vector-keying application

* Sun Ultra series, a brand of computer work ...

decoding transcripts, that most of the Germans had already escaped encirclement, and he feared a German counterattack as well as possible friendly fire casualties. Though admitting that a mistake had been made, Bradley placed the blame on General Montgomery for moving the British and Commonwealth troops too slowly, though the latter were in direct contact with a large number of SS Panzer, paratroopers

A paratrooper or military parachutist is a soldier trained to conduct military operations by parachuting directly into an area of operations, usually as part of a large airborne forces unit. Traditionally paratroopers fight only as light inf ...

, and other elite German forces.

Germany

The American forces reached the "Siegfried Line

The Siegfried Line, known in German as the ''Westwall (= western bulwark)'', was a German defensive line built during the late 1930s. Started in 1936, opposite the French Maginot Line, it stretched more than from Kleve on the border with the ...

" or "Westwall" in late September. The success of the advance had taken the Allied high command by surprise. They had expected the German ''Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

'' to make stands on the natural defensive lines provided by the French rivers, and had not prepared the logistics

Logistics is the part of supply chain management that deals with the efficient forward and reverse flow of goods, services, and related information from the point of origin to the Consumption (economics), point of consumption according to the ...

for the much deeper advance of the Allied armies, so fuel ran short.

Eisenhower faced a decision on strategy. Bradley favored an advance into the

Eisenhower faced a decision on strategy. Bradley favored an advance into the Saarland

Saarland (, ; ) is a state of Germany in the southwest of the country. With an area of and population of 990,509 in 2018, it is the smallest German state in area apart from the city-states of Berlin, Bremen, and Hamburg, and the smallest in ...

, or possibly a two-thrust assault on both the Saarland and the Ruhr Area

The Ruhr ( ; , also ''Ruhrpott'' ), also referred to as the Ruhr Area, sometimes Ruhr District, Ruhr Region, or Ruhr Valley, is a polycentric urban area in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. With a population density of 1,160/km2 and a populati ...

. Montgomery argued for a narrow thrust across the Lower Rhine, preferably with all Allied ground forces under his personal command as they had been in the early months of the Normandy campaign, into the open country beyond and then to the northern flank into the Ruhr, thus avoiding the Siegfried Line

The Siegfried Line, known in German as the ''Westwall (= western bulwark)'', was a German defensive line built during the late 1930s. Started in 1936, opposite the French Maginot Line, it stretched more than from Kleve on the border with the ...

. Although Montgomery was not permitted to launch an offensive on the scale he had wanted, George Marshall and Hap Arnold

Henry Harley "Hap" Arnold (25 June 1886 – 15 January 1950) was an American general officer holding the ranks of General of the Army and later, General of the Air Force. Arnold was an aviation pioneer, Chief of the Air Corps (1938–1 ...

were eager to use the First Allied Airborne Army

The First Allied Airborne Army was an Allies of World War II, Allied Military organization, formation formed on 2 August 1944 by the order of General of the Army (United States), General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Headquarters Allied Exped ...

to cross the Rhine, so Eisenhower agreed to Operation Market Garden. Bradley opposed the operation, and bitterly protested to Eisenhower the priority of supplies given to Montgomery, but Eisenhower, mindful of British public opinion regarding damage from V-1 missile launches in the north, refused to make any changes.

Bradley's Army Group now covered a very wide front in hilly country, from the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

to Lorraine

Lorraine, also , ; ; Lorrain: ''Louréne''; Lorraine Franconian: ''Lottringe''; ; ; is a cultural and historical region in Eastern France, now located in the administrative region of Grand Est. Its name stems from the medieval kingdom of ...

. Despite having the largest concentration of Allied army forces, Bradley faced difficulties in prosecuting a successful broad-front offensive in difficult country with a skilled enemy. General Bradley and his First Army commander, General Courtney Hodges

General Courtney Hicks Hodges (5 January 1887 – 16 January 1966) was a decorated senior officer in the United States Army who commanded First U.S. Army in the Western European Campaign of World War II. Hodges was a notable "mustang" officer, ...

, eventually decided to attack through a corridor known as the Aachen Gap towards the German township of Schmidt. The only nearby military objectives were the Roer River flood control dams, but these were not mentioned in contemporary plans and documents. Bradley and Hodges' original objective may have been to outflank German forces and prevent them from reinforcing their units further north in the Battle of Aachen

The Battle of Aachen was a battle of World War II, fought by American and German forces in and around Aachen, Germany, between 12 September and 21 October 1944. The city had been incorporated into the Siegfried Line, the main defensive network ...

. After the war, Bradley would cite the Roer dams as the objective. Since the Germans held the dams, they could also unleash millions of gallons of water into the path of advance. The campaign's confused objectives, combined with poor intelligence, resulted in the costly series of battles known as the Battle of Hurtgen Forest

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force c ...

, which cost some 33,000 American casualties.D'Este, Carlo, ''Eisenhower: A Soldier's Life'', p. 627. At the end of the fighting in the Hurtgen, German forces remained in control of the Roer dams in what has been described as "the most ineptly fought series of battles of the war in the west." Further south, Patton's Third Army, which had been advancing with great speed, was faced with last priority (behind the U.S. First and Ninth Armies) for supplies, gasoline and ammunition. As a result, the Third Army lost momentum as German resistance stiffened around the extensive defenses surrounding the city of Metz

Metz ( , , , then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle (river), Moselle and the Seille (Moselle), Seille rivers. Metz is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Moselle (department), Moselle Departments ...

. While Bradley focused on these two campaigns, the Germans were in the process of assembling troops and materiel for a surprise winter offensive.

Battle of the Bulge

Bradley's command took the initial brunt of what would become theBattle of the Bulge

The Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Ardennes Offensive or Unternehmen Die Wacht am Rhein, Wacht am Rhein, was the last major German Offensive (military), offensive Military campaign, campaign on the Western Front (World War II), Western ...

. For logistical and command reasons, General Eisenhower decided to place Bradley's First and Ninth Armies under the temporary command of Field Marshal Montgomery's 21st Army Group on the northern flank of the Bulge. Bradley was incensed, and began shouting at Eisenhower: "By God, Ike, I cannot be responsible to the American people if you do this. I resign." Eisenhower turned red, took a breath and replied evenly, "Brad, I—not you—am responsible to the American people. Your resignation therefore means absolutely nothing."Ambrose, Stephen, ''Eisenhower, soldier and president'', p. 174. Bradley paused, made one more protest, then fell silent as Eisenhower concluded, "Well, Brad, those are my orders."

At least one historian has attributed Eisenhower's support for Bradley's subsequent promotion to (temporary) four-star general (March 1945, not made permanent until January 1949) to, in part, a desire to compensate him for the way in which he had been sidelined during the Battle of the Bulge. Others point out that both Secretary of War Stimson and General Eisenhower had desired to reward General Patton with a fourth star for his string of accomplishments in 1944, but that Eisenhower could not promote Patton over Bradley, Devers, and other senior commanders without upsetting the chain of command (as Bradley commanded these people in the theater). A more likely explanation is that as Bradley commanded an Army Group and was the immediate subordinate of Eisenhower, who was promoted to five star rank on 20 December 1944, it was only appropriate that he should hold the next lower rank.

Victory

Bradley used the advantage gained in March 1945—after Eisenhower authorized a difficult but successful Allied offensive (on a broad front with British

Bradley used the advantage gained in March 1945—after Eisenhower authorized a difficult but successful Allied offensive (on a broad front with British Operation Veritable

Operation Veritable (also known as the Battle of the Reichswald) was the northern part of an Allies of World War II, Allied pincer movement that took place between 8 February and 11 March 1945 during the final stages of the World War II, Second ...

to the north and American Operation Grenade

During World War II, Operation Grenade was the crossing of the Roer river between Roermond and Düren by the U.S. Ninth Army, commanded by Lieutenant General William Hood Simpson, in February 1945, which marked the beginning of the Allied inv ...

to the south) in February 1945—to break the German defenses and cross the Rhine into the industrial heartland of the Ruhr. Aggressive pursuit of the disintegrating German troops by the 9th Armored Division resulted in the capture of a bridge across the Rhine River

The Rhine ( ) is one of the major rivers in Europe. The river begins in the Swiss canton of Graubünden in the southeastern Swiss Alps. It forms part of the Swiss-Liechtenstein border, then part of the Swiss-Austrian border. From Lake Cons ...

at Remagen

Remagen () is a town in Germany in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate, in the district of Ahrweiler (district), Ahrweiler. It is about a one-hour drive from Cologne, just south of Bonn, the former West Germany, West German seat of government. It i ...

. Bradley quickly exploited the crossing, forming the southern arm of an enormous pincer movement

The pincer movement, or double envelopment, is a maneuver warfare, military maneuver in which forces simultaneously attack both flanking maneuver, flanks (sides) of an enemy Military organization, formation. This classic maneuver has been im ...

encircling the German forces in the Ruhr from the north and south. Over 300,000 prisoners were taken. American forces then met up with the Soviet forces near the Elbe

The Elbe ( ; ; or ''Elv''; Upper Sorbian, Upper and , ) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Republic), then Ge ...

River in mid-April. By V-E Day

Victory in Europe Day is the day celebrating the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Germany's unconditional surrender of its armed forces on Tuesday, 8 May 1945; it marked the official surrender of all German military operations ...

, the 12th Army Group was a force of four armies (First, Third, Ninth, and Fifteenth) that numbered over 1.3 million men.

Command style

Unlike some of the more colorful generals of World War II, Bradley was polite and courteous in his public appearances. A reticent man, Bradley was first favorably brought to public attention bywar correspondent

A war correspondent is a journalist who covers stories first-hand from a war, war zone.

War correspondence stands as one of journalism's most important and impactful forms. War correspondents operate in the most conflict-ridden parts of the wor ...

Ernie Pyle

Ernest Taylor Pyle (August 3, 1900 – April 18, 1945) was an American journalist and war correspondent who is best known for his stories about ordinary American soldiers during World War II. Pyle is also notable for the Columnist#Newspaper and ...

, who was urged by General Eisenhower to "go and discover Bradley". Pyle subsequently wrote several dispatches in which he referred to Bradley as the GI's general, a title that would stay with Bradley throughout his remaining career. Will Lang Jr.

William John Lang Jr. (October 7, 1914 – January 21, 1968) was an American journalist and a bureau head for ''Life'' magazine.

Early career

Lang was born on the south side of Chicago. While attending the University of Chicago in 1936, he wr ...

of ''Life

Life, also known as biota, refers to matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes. It is defined descriptively by the capacity for homeostasis, Structure#Biological, organisation, met ...

'' magazine said "The thing I most admire about Omar Bradley is his gentleness. He was never known to issue an order to anybody of any rank without saying 'Please' first."

While the public at large never forgot the image created by newspaper correspondents, a different view of Bradley was offered by combat historian S. L. A. Marshall, who knew both Bradley and George Patton, and had interviewed officers and men under their commands. Marshall, who was also a critic of George S. Patton, noted that Bradley's "common man" image "was played up by Ernie Pyle...The GIs were not impressed with him. They scarcely knew him. He's not a flamboyant figure and he didn't get out much to troops. And the idea that he was idolized by the average soldier is just rot."

While Bradley retained his reputation as the ''GI's general'', he was criticized by some of his contemporaries for other aspects of his leadership style, sometimes described as "managerial" in nature. British General Bernard Montgomery's assessment of Bradley was that he was "dull, conscientious, dependable, and loyal". He had a habit of peremptorily relieving senior commanders who he felt were too independent, or whose command style did not agree with his own, such as the colorful and aggressive General Terry Allen, commander of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division

The 1st Infantry Division (1ID) is a Armored brigade combat team, combined arms Division (military), division of the United States Army, and is the oldest continuously serving division in the Regular Army (United States), Regular Army. It has ...

(who was relocated to a different command because Bradley felt that his continued command of the division was making it unmanageably elitist, a decision with which Eisenhower concurred). While Patton is often viewed today as the archetype of the intolerant, impulsive commander, Bradley actually sacked far more generals and senior commanders during World War II, whereas Patton relieved only one general from his command—Orlando Ward

Major General Orlando Ward (November 4, 1891 – February 4, 1972) was a career United States Army officer who fought in both World War I and World War II. During the latter, as a major general, he commanded the 1st Armored Division during Oper ...

—for cause during the entire war (and only after giving General Ward two warnings). When required, Bradley could be a hard disciplinarian; he recommended the death sentence for several soldiers while he served as the commander of the First Army.

One controversy of Bradley's leadership involved the lack of use of specialized tanks (Hobart's Funnies

Hobart's Funnies is the nickname given to a number of specialist armoured fighting vehicles derived from tanks operated during the Second World War by units of the 79th Armoured Division of the British Army or by specialists from the Royal En ...

) in the Normandy invasion. After the war Chester Wilmot

Reginald William Winchester Wilmot (21 June 1911 – 10 January 1954) was an Australian war correspondent who reported for the BBC and the ABC during the Second World War. After the war he continued to work as a broadcast reporter, and wro ...

quoted correspondence with the developer of the tanks, Major General Percy Hobart

Major-General Sir Percy Cleghorn Stanley Hobart, (14 June 1885 – 19 February 1957), also known as "Hobo", was a British military engineer noted for his command of the 79th Armoured Division during the Second World War. He was responsible for ...

, to the effect that the failure to use such tanks was a major contributing factor to the losses at Omaha Beach, and that Bradley had deferred the decision whether to use the tanks to his staff who had not taken up the offer, other than in respect of the DD (swimming) tanks. However a later memo from the 21st Army Group is on record as relaying two separate requests from the First Army, one dealing with the DD tanks and "Porpoises" (towed waterproof trailers), the other with a variety of other Funnies. The second list gives not only items of specific interest with requested numbers, but items known to be available that were not of interest. The requested items were modified Shermans, and tank attachments compatible with Shermans. Noted as not of interest were Funnies that required Churchill or Valentine tanks, or for which alternatives were available from the US. Of the six requested types of Funnies, the Sherman flamethrower version of the Churchill Crocodile

The Churchill Crocodile was a British flame-throwing tank of late Second World War. It was a variant of the Tank, Infantry, Mk IV (A22) Churchill Mark VII, although the Churchill Mark IV was initially chosen to be the base vehicle.

The Croco ...

is known to have been difficult to produce, and the Centipede never seems to have been used in combat. Richard Anderson considers that the press of time prevented the production of the other four items in numbers beyond the Commonwealth's requirements. Given the heavier surf and the topography of Omaha Beach, it is unlikely that the funnies would have been as useful there as they were on the Commonwealth beaches. The British had agreed to provide British-crewed Funnies to operate with the American forces but were unable to train the crews and deliver the vehicles in time.

Post-war

Veterans Administration

President Truman appointed Bradley to head theVeterans Administration

The United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is a Cabinet-level executive branch department of the federal government charged with providing lifelong healthcare services to eligible military veterans at the 170 VA medical centers an ...