Galileo Affair on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Galileo affair was an early 17th century political, religious, and scientific controversy regarding the astronomer

Galileo began his telescopic observations in the later part of 1609, and by March 1610 was able to publish a small book, ''The Starry Messenger'' (''

Galileo began his telescopic observations in the later part of 1609, and by March 1610 was able to publish a small book, ''The Starry Messenger'' (''

/ref>Extract of page 4

/ref> and supported the Copernican model advanced by Galileo.

Geostaticism agreed with a literal interpretation of Scripture in several places, such as , , , , (but see varied interpretations of ).

Geostaticism agreed with a literal interpretation of Scripture in several places, such as , , , , (but see varied interpretations of ).

Lorini and his colleagues decided to bring Galileo's letter to the attention of the Inquisition. In February 1615, Lorini accordingly sent a copy to the Secretary of the Inquisition, Cardinal

Lorini and his colleagues decided to bring Galileo's letter to the attention of the Inquisition. In February 1615, Lorini accordingly sent a copy to the Secretary of the Inquisition, Cardinal

Cardinal

Cardinal

With no attractive alternatives, Galileo accepted the orders delivered, even sterner than those recommended by the Pope. Galileo met again with Bellarmine, apparently on friendly terms; and on March 11 he met with the Pope, who assured him that he was safe from prosecution so long as he, the Pope, should live. Nonetheless, Galileo's friends Sagredo and Castelli reported that there were rumors that Galileo had been forced to

With no attractive alternatives, Galileo accepted the orders delivered, even sterner than those recommended by the Pope. Galileo met again with Bellarmine, apparently on friendly terms; and on March 11 he met with the Pope, who assured him that he was safe from prosecution so long as he, the Pope, should live. Nonetheless, Galileo's friends Sagredo and Castelli reported that there were rumors that Galileo had been forced to

In 1623,

In 1623,

With the loss of many of his defenders in Rome because of ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'', in 1633 Galileo was ordered to stand trial on suspicion of heresy "for holding as true the false doctrine taught by some that the sun is the center of the world" against the 1616 condemnation, since "it was decided at the Holy Congregation ..on 25 Feb 1616 that ..the Holy Office would give you an injunction to abandon this doctrine, not to teach it to others, not to defend it, and not to treat of it; and that if you did not acquiesce in this injunction, you should be imprisoned".

Galileo was interrogated while threatened with physical torture. A panel of theologians, consisting of

With the loss of many of his defenders in Rome because of ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'', in 1633 Galileo was ordered to stand trial on suspicion of heresy "for holding as true the false doctrine taught by some that the sun is the center of the world" against the 1616 condemnation, since "it was decided at the Holy Congregation ..on 25 Feb 1616 that ..the Holy Office would give you an injunction to abandon this doctrine, not to teach it to others, not to defend it, and not to treat of it; and that if you did not acquiesce in this injunction, you should be imprisoned".

Galileo was interrogated while threatened with physical torture. A panel of theologians, consisting of  After a period with the friendly Archbishop Piccolomini in

After a period with the friendly Archbishop Piccolomini in

pp. 133–134)

and Seeger (1966

p. 30)

for example. Drake (1978

p. 355)

asserts that Simplicio's character is modelled on the Aristotelian philosophers, Lodovico delle Colombe and Cesare Cremonini, rather than Urban. He also considers that the demand for Galileo to include the Pope's argument in the ''Dialogue'' left him with no option but to put it in the mouth of Simplicio (Drake, 1953, p. 491). Even

In addition to the large non-fiction literature and the many documentary films about Galileo and the Galileo affair, there have also been several treatments in historical plays and films. The

In addition to the large non-fiction literature and the many documentary films about Galileo and the Galileo affair, there have also been several treatments in historical plays and films. The

Institute and Museum of the History of Science

Florence, and a brief overview of ''Le Opere'' is available at , an

* * * * * * * * * * * * * Original edition published by Hutchinson (London). * . Original edition by Desclee (New York, 1966) * * McMullen, Emerson Thomas, ''Galileo's condemnation: The real and complex story'' (Georgia Journal of Science, vol. 61(2) 2003) * * * * * . * * * * * * Speller, Jules, ''Galileo's Inquisition Trial Revisited '', Peter Lang Europäischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2008. 431 pp. / US- * * * * *

lecture ( ttps://web.archive.org/web/20110108175957/http://thomasaquinas.edu/news/recent_events/Galileo_Galilei-Scripture_Exegete.mp3 audio here by Thomas Aquinas College tutor Dr. Christopher Decaen

"The End of the Myth of Galileo Galilei"

by

''The Starry Messenger'' (1610)

. An English translation fro

Bard College

Original Latin text a

LiberLiber

online library.

Galileo's letter to Castelli of 1613

The English translation given on the web page at this link is from Finocchiaro (1989), contrary to the claim made in the citation given on the page itself.

Galileo's letter to the Grand Duchess Christina of 1615Bellarmine's letter to Foscarini of 1615

Extensively documented series of lectures by William E. Carroll and Peter Hodgson.

Edizione Nationale

. A searchable online copy of Favaro's National Edition of Galileo's works at the website of th

Florence. {{Authority control 17th-century Catholicism 17th century in science Astronomical controversies Cognitive inertia Copernican Revolution Events relating to freedom of expression Galileo Galilei History of astronomy Inquisition Pope Paul V 1610 beginnings 1633 endings

Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

's defence of heliocentrism

Heliocentrism (also known as the heliocentric model) is a superseded astronomical model in which the Earth and planets orbit around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed t ...

, the idea that the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

revolves around the Sun

The Sun is the star at the centre of the Solar System. It is a massive, nearly perfect sphere of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core, radiating the energy from its surface mainly as visible light a ...

. It pitted supporters and opponents of Galileo within both the Catholic Church and academia

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of tertiary education. The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 386 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the go ...

against each other through two phases: an interrogation and condemnation of Galileo's ideas by a panel of the Roman Inquisition

The Roman Inquisition, formally , was a system of partisan tribunals developed by the Holy See of the Catholic Church, during the second half of the 16th century, responsible for prosecuting individuals accused of a wide array of crimes according ...

in 1616, and a second trial in 1632 which led to Galileo's house arrest

House arrest (also called home confinement, or nowadays electronic monitoring) is a legal measure where a person is required to remain at their residence under supervision, typically as an alternative to imprisonment. The person is confined b ...

and a ban on his books.

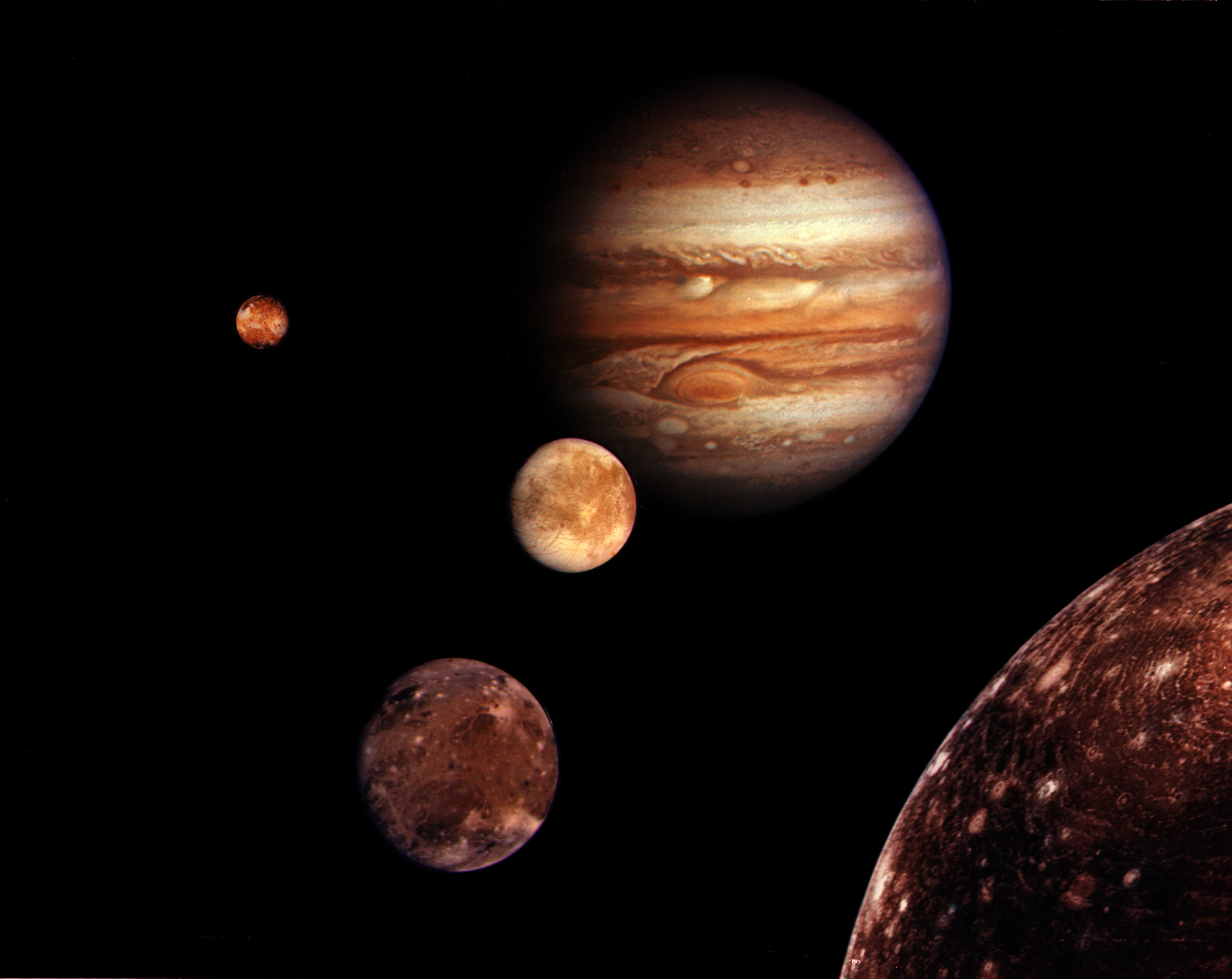

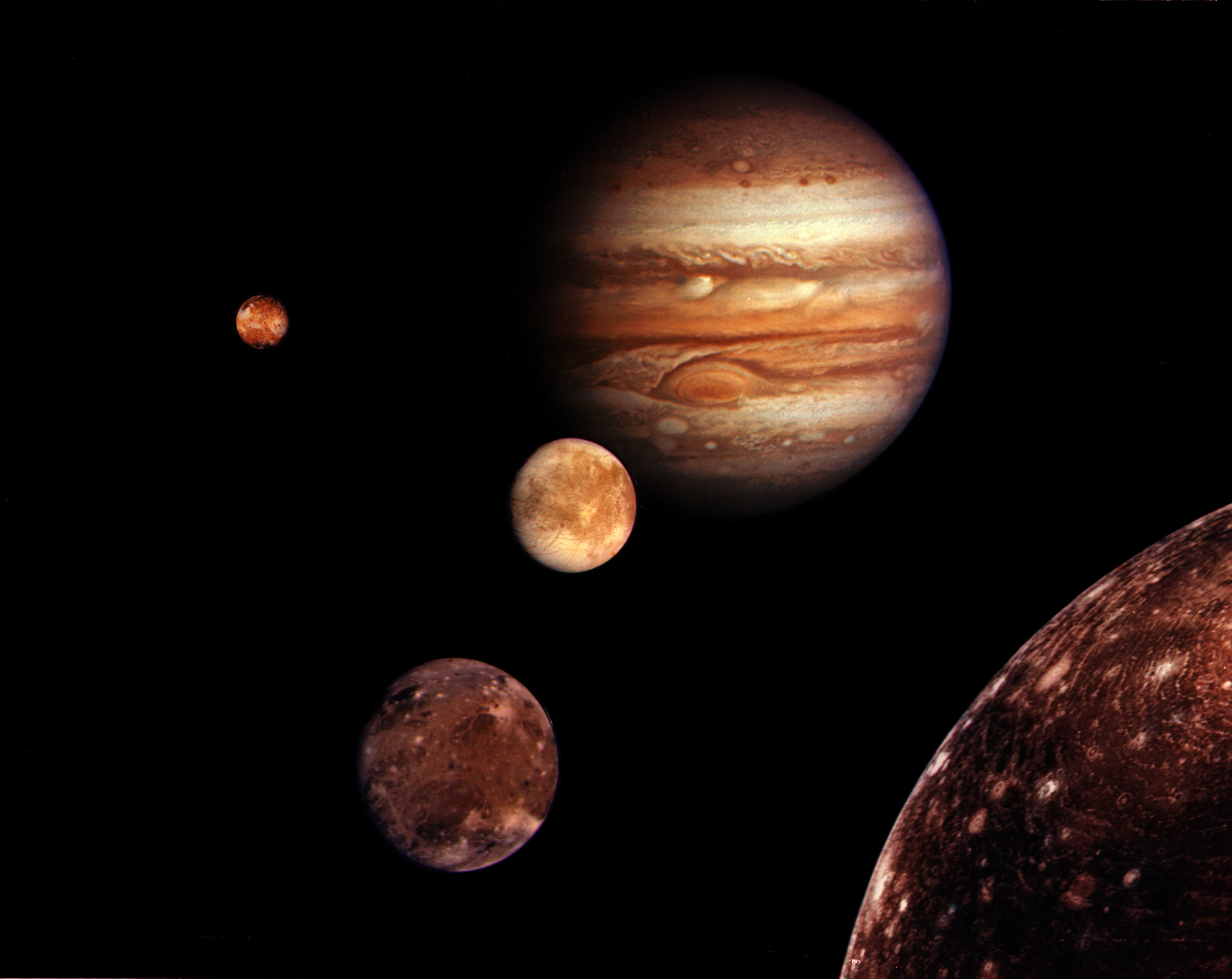

In 1610, Galileo published his ''Sidereus Nuncius

''Sidereus Nuncius'' (usually ''Sidereal Messenger'', also ''Starry Messenger'' or ''Sidereal Message'') is a short astronomical treatise (or ''pamphlet'') published in Neo-Latin by Galileo Galilei on March 13, 1610. It was the first published ...

'' (''Starry Messenger'') describing the observations that he had made with his new, much stronger telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, Absorption (electromagnetic radiation), absorption, or Reflection (physics), reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally, it was an optical instrument using len ...

, amongst them the Galilean moons

The Galilean moons (), or Galilean satellites, are the four largest moons of Jupiter. They are, in descending-size order, Ganymede (moon), Ganymede, Callisto (moon), Callisto, Io (moon), Io, and Europa (moon), Europa. They are the most apparent m ...

of Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a Jupiter mass, mass more than 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined a ...

. With these observations and additional observations that followed, such as the phases of Venus

The phases of Venus are the variations of lighting seen on the planet's surface, similar to lunar phases. The first recorded observations of them are thought to have been telescopic observations by Galileo Galilei in 1610. Although the extreme c ...

, he promoted the heliocentric theory of Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

published in ''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (English translation: ''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres'') is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) of the Polish Renaissance. The book ...

'' in 1543. Galileo's opinions were met with opposition within the Catholic Church, and in 1616 the Inquisition declared heliocentrism to be both scientifically indefensible and heretical. Galileo went on to propose a theory of tides

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ...

in 1616, and of comets

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that warms and begins to release gases when passing close to the Sun, a process called outgassing. This produces an extended, gravitationally unbound atmosphere or coma surrounding the nucleus, an ...

in 1619; he argued (incorrectly) that the tides were evidence for the motion of the Earth.

In 1632, Galileo published his ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems

''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'' (''Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo'') is a 1632 book by Galileo Galilei comparing Nicolaus Copernicus's Copernican heliocentrism, heliocentric system model with Ptolemy's geocen ...

'', which defended heliocentrism while describing geocentrists as "simpletons". Responding to mounting controversy, the Roman Inquisition

The Roman Inquisition, formally , was a system of partisan tribunals developed by the Holy See of the Catholic Church, during the second half of the 16th century, responsible for prosecuting individuals accused of a wide array of crimes according ...

tried Galileo in 1633 and found him "vehemently suspect of heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Heresy in Christian ...

", sentencing him to house arrest. At this point, heliocentric books were banned and Galileo was ordered to abstain from holding, teaching or defending heliocentric ideas after the trial.

The affair was complex, with Pope Urban VIII

Pope Urban VIII (; ; baptised 5 April 1568 – 29 July 1644), born Maffeo Vincenzo Barberini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 August 1623 to his death, in July 1644. As pope, he expanded the papal terri ...

originally being a patron and supporter of Galileo before turning against him. Urban initially gave Galileo permission to publish on the Copernican theory so long as he treated it as a hypothesis, but after the publication of the ''Dialogue'' in 1632, the patronage was broken off. Historians of science have since corrected numerous false interpretations of the affair. McMullin (2008)

Initial controversies

Galileo began his telescopic observations in the later part of 1609, and by March 1610 was able to publish a small book, ''The Starry Messenger'' (''

Galileo began his telescopic observations in the later part of 1609, and by March 1610 was able to publish a small book, ''The Starry Messenger'' (''Sidereus Nuncius

''Sidereus Nuncius'' (usually ''Sidereal Messenger'', also ''Starry Messenger'' or ''Sidereal Message'') is a short astronomical treatise (or ''pamphlet'') published in Neo-Latin by Galileo Galilei on March 13, 1610. It was the first published ...

''), describing some of his discoveries: mountains on the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It Orbit of the Moon, orbits around Earth at Lunar distance, an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth diameter, Earth's diameter). The Moon rotation, rotates, with a rotation period (lunar ...

, lesser moons in orbit around Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a Jupiter mass, mass more than 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined a ...

, and the resolution of what had been thought to be very cloudy masses in the sky (nebulae) into collections of stars too faint to see individually without a telescope. Other observations followed, including the phases of Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is often called Earth's "twin" or "sister" planet for having almost the same size and mass, and the closest orbit to Earth's. While both are rocky planets, Venus has an atmosphere much thicker ...

and the existence of sunspot

Sunspots are temporary spots on the Sun's surface that are darker than the surrounding area. They are one of the most recognizable Solar phenomena and despite the fact that they are mostly visible in the solar photosphere they usually aff ...

s.

Galileo's contributions caused difficulties for theologians

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

and natural philosophers

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the developme ...

of the time, as they contradicted scientific and philosophical ideas based on those of Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

and Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

and closely associated with the Catholic Church. In particular, Galileo's observations of the phases of Venus, which showed it to circle the Sun, and the observation of moons orbiting Jupiter, contradicted the geocentric model

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded scientific theories, superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric m ...

of Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

, which was backed and accepted by the Roman Catholic Church,Extract of page 1/ref>Extract of page 4

/ref> and supported the Copernican model advanced by Galileo.

Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

astronomers, experts both in Church teachings, science, and in natural philosophy, were at first skeptical and hostile to the new ideas; however, within a year or two the availability of good telescopes enabled them to repeat the observations. In 1611, Galileo visited the Collegium Romanum in Rome, where the Jesuit astronomers by that time had repeated his observations. Christoph Grienberger, one of the Jesuit scholars on the faculty, sympathized with Galileo's theories, but was asked to defend the Aristotelian viewpoint by Claudio Acquaviva

Claudio Acquaviva, SJ (14 September 1543 – 31 January 1615) was an Italian Jesuit priest. Elected in 1581 as the fifth Superior General of the Society of Jesus, he has been referred to as the second founder of the Jesuit order.

Early life and ...

, the Father General of the Jesuits. Not all of Galileo's claims were completely accepted: Christopher Clavius

Christopher Clavius, (25 March 1538 – 6 February 1612) was a Jesuit German mathematician, head of mathematicians at the , and astronomer who was a member of the Vatican commission that accepted the proposed calendar invented by Aloysius ...

, the most distinguished astronomer of his age, never was reconciled to the idea of mountains on the Moon, and outside the collegium many still disputed the reality of the observations. In a letter to Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws of p ...

of August 1610, Galileo complained that some of the philosophers who opposed his discoveries had refused even to look through a telescope:

In 1611, the same year that Galileo visited the Collegium Romanum, his theories first came to the attention of the Roman Inquisition. A commission of cardinals working with the inquisition made inquiries into Galileo's activities, and asked the city of Padua if he had any connections to Cesare Cremonini, a professor at the university of Padua who had been charged with heresy by the Inquisition. These inquiries marked the first time Galileo's name was brought before the inquisition.

Geocentrists who did verify and accept Galileo's findings had an alternative to Ptolemy's model in an alternative geocentric (or "geo-heliocentric") model proposed some decades earlier by Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe, ; 14 December 154624 October 1601), generally called Tycho for short, was a Danish astronomer of the Renaissance, known for his comprehensive and unprecedentedly accurate astronomical observations. He ...

– a model in which, for example, Venus circled the Sun. Tycho argued that the distance to the stars in the Copernican system would have to be 700 times greater than the distance from the Sun to Saturn. (The nearest star other than the Sun, Proxima Centauri, is over 28,000 times the distance from the Sun to Saturn.) Moreover, the only way the stars could be so distant and still appear the sizes they do in the sky would be if even average stars were gigantic – at least as big as the orbit of the Earth, and of course vastly larger than the Sun. (See the articles on the Tychonic System

The Tychonic system (or Tychonian system) is a model of the universe published by Tycho Brahe in 1588, which combines what he saw as the mathematical benefits of the Copernican heliocentrism, Copernican system with the philosophical and "physic ...

and Stellar parallax

Stellar parallax is the apparent shift of position (''parallax'') of any nearby star (or other object) against the background of distant stars. By extension, it is a method for determining the distance to the star through trigonometry, the stel ...

.)

Galileo became involved in a dispute over priority in the discovery of sunspots with Christoph Scheiner

Christoph Scheiner (25 July 1573 (or 1575) – 18 June 1650) was a Jesuit priest, physicist and astronomer in Ingolstadt.

Biography Augsburg/Dillingen: 1591–1605

Scheiner was born in Markt Wald near Mindelheim in Swabia, earlier margravate Burg ...

, a Jesuit. This became a bitter lifelong feud. Neither of them, however, was the first to recognise sunspots – the Chinese had already been familiar with them for centuries.

At this time, Galileo also engaged in a dispute over the reasons that objects float or sink in water, siding with Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse ( ; ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Greek mathematics, mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and Invention, inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse, Sicily, Syracuse in History of Greek and Hellenis ...

against Aristotle. The debate was unfriendly, and Galileo's blunt and sometimes sarcastic style, though not extraordinary in academic debates of the time, made him enemies. During this controversy one of Galileo's friends, the painter Lodovico Cardi da Cigoli, informed him that a group of malicious opponents, which Cigoli subsequently referred to derisively as "the Pigeon league", was plotting to cause him trouble over the motion of the Earth, or anything else that would serve the purpose. According to Cigoli, one of the plotters asked a priest to denounce Galileo's views from the pulpit, but the latter refused. Nevertheless, three years later another priest, Tommaso Caccini

Tommaso Caccini (1574–1648) was an Italian Dominican friar and preacher.

Born in Florence as Cosimo Caccini, he entered into the Dominican Order of the Catholic Church as a teenager. Caccini began his career in the monastery of San Marco and gra ...

, did in fact do precisely that, as described below.

Bible argument

In the Catholic world prior to Galileo's conflict with the Church, the majority of educated people subscribed to the Aristoteliangeocentric

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, an ...

view that the Earth was the centre of the universe and that all heavenly bodies revolved around the Earth, though Copernican theories were used to reform the calendar in 1582.

Geostaticism agreed with a literal interpretation of Scripture in several places, such as , , , , (but see varied interpretations of ).

Geostaticism agreed with a literal interpretation of Scripture in several places, such as , , , , (but see varied interpretations of ). Heliocentrism

Heliocentrism (also known as the heliocentric model) is a superseded astronomical model in which the Earth and planets orbit around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed t ...

, the theory that the Earth was a planet, which along with all the others revolved around the Sun, contradicted both geocentrism

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, a ...

and the prevailing theological support of the theory.

One of the first suggestions of heresy that Galileo had to deal with came in 1613 from a professor of philosophy, poet and specialist in Greek literature, Cosimo Boscaglia. In conversation with Galileo's patron Cosimo II de' Medici

Cosimo II de' Medici (12 May 1590 – 28 February 1621) was Grand Duke of Tuscany from 1609 until his death. He was the elder son of Ferdinando I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, and Christina of Lorraine.

For the majority of his 12-year rei ...

and Cosimo's mother Christina of Lorraine, Boscaglia said that the telescopic discoveries were valid, but that the motion of the Earth was obviously contrary to Scripture:

Dr. Boscaglia had talked to Madame hristinafor a while, and though he conceded all the things you have discovered in the sky, he said that the motion of the Earth was incredible and could not be, particularly since Holy Scripture obviously was contrary to such motion. – Letter from Benedetto Castelli to Galileo, 1613–14Galileo was defended on the spot by his former student

Benedetto Castelli

Benedetto Castelli (1578 – 9 April 1643), born Antonio Castelli, was an Italians, Italian mathematician. Benedetto was his name in religion on entering the Benedictine Order in 1595.

Life

Born in Brescia, Castelli studied at the University of ...

, now a professor of mathematics and Benedictine

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict (, abbreviated as O.S.B. or OSB), are a mainly contemplative monastic order of the Catholic Church for men and for women who follow the Rule of Saint Benedict. Initiated in 529, th ...

abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the head of an independent monastery for men in various Western Christian traditions. The name is derived from ''abba'', the Aramaic form of the Hebrew ''ab'', and means "father". The female equivale ...

. The exchange having been reported to Galileo by Castelli, Galileo decided to write a letter to Castelli, expounding his views on what he considered the most appropriate way of treating scriptural passages which made assertions about natural phenomena. Later, in 1615, he expanded this into his much longer '' Letter to the Grand Duchess Christina''.

Tommaso Caccini

Tommaso Caccini (1574–1648) was an Italian Dominican friar and preacher.

Born in Florence as Cosimo Caccini, he entered into the Dominican Order of the Catholic Church as a teenager. Caccini began his career in the monastery of San Marco and gra ...

, a Dominican friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders in the Catholic Church. There are also friars outside of the Catholic Church, such as within the Anglican Communion. The term, first used in the 12th or 13th century, distinguishes the mendi ...

, appears to have made the first dangerous attack on Galileo. Preaching a sermon in Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

at the end of 1614, he denounced Galileo, his associates, and mathematicians in general (a category that included astronomers). The biblical text for the sermon on that day was Joshua

Joshua ( ), also known as Yehoshua ( ''Yəhōšuaʿ'', Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yŏhōšuaʿ,'' Literal translation, lit. 'Yahweh is salvation'), Jehoshua, or Josue, functioned as Moses' assistant in the books of Book of Exodus, Exodus and ...

10, in which Joshua makes the Sun stand still; this was the story that Castelli had to interpret for the Medici family the year before. It is said, though it is not verifiable, that Caccini also used the passage from Acts 1:11, "Ye men of Galilee, why stand ye gazing up into heaven?".First meetings with theological authorities

In late 1614 or early 1615, one of Caccini's fellow Dominicans, Niccolò Lorini, acquired a copy of Galileo's letter to Castelli. Lorini and other Dominicans at the Convent of San Marco considered the letter of doubtful orthodoxy, in part because it may have violated the decrees of theCouncil of Trent

The Council of Trent (), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation at the time, it has been described as the "most ...

:

Paolo Emilio Sfondrati

Paolo Emilio Sfondrati (1560 – 14 February 1618) was an Italian cardinal.

Biography

Born to a noble family in Milan and the nephew of Pope Gregory XIV, he was the cardinal priest of Santa Cecilia in Trastevere, papal legate in Bologna, member ...

, with a covering letter critical of Galileo's supporters:

On March 19, Caccini arrived at the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a Catholic Inquisitorial system#History, judicial procedure where the Ecclesiastical court, ecclesiastical judges could initiate, investigate and try cases in their jurisdiction. Popularly it became the name for various med ...

's offices in Rome to denounce Galileo for his Copernicanism

Copernican heliocentrism is the astronomical model developed by Nicolaus Copernicus and published in 1543. This model positioned the Sun at the center of the Universe, motionless, with Earth and the other planets orbiting around it in circular pa ...

and various other alleged heresies supposedly being spread by his pupils.

Galileo soon heard reports that Lorini had obtained a copy of his letter to Castelli and was claiming that it contained many heresies. He also heard that Caccini had gone to Rome and suspected him of trying to stir up trouble with Lorini's copy of the letter. As 1615 wore on he became more concerned, and eventually determined to go to Rome as soon as his health permitted, which it did at the end of the year. By presenting his case there, he hoped to clear his name of any suspicion of heresy, and to persuade the Church authorities not to suppress heliocentric ideas.

In going to Rome Galileo was acting against the advice of friends and allies, and of the Tuscan ambassador to Rome, Piero Guicciardini.

Bellarmine

Cardinal

Cardinal Robert Bellarmine

Robert Bellarmine (; ; 4 October 1542 – 17 September 1621) was an Italian Jesuit and a cardinal of the Catholic Church. He was canonized a saint in 1930 and named Doctor of the Church, one of only 37. He was one of the most important figure ...

, one of the most respected Catholic theologians of the time, was called on to adjudicate the dispute between Galileo and his opponents. The question of heliocentrism had first been raised with Cardinal Bellarmine, in the case of Paolo Antonio Foscarini, a Carmelite

The Order of the Brothers of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel (; abbreviated OCarm), known as the Carmelites or sometimes by synecdoche known simply as Carmel, is a mendicant order in the Catholic Church for both men and women. Histo ...

father; Foscarini had published a book, ''Lettera ... sopra l'opinione ... del Copernico'', which attempted to reconcile Copernicus with the biblical passages that seemed to be in contradiction. Bellarmine at first expressed the opinion that Copernicus's book would not be banned, but would at most require some editing so as to present the theory purely as a calculating device for " saving the appearances" (i.e. preserving the observable evidence).

Foscarini sent a copy of his book to Bellarmine, who replied in a letter of April 12, 1615. Galileo is mentioned by name in the letter, and a copy was soon sent to him. After some preliminary salutations and acknowledgements, Bellarmine begins by telling Foscarini that it is prudent for him and Galileo to limit themselves to treating heliocentrism as a merely hypothetical phenomenon and not a physically real one. Further on he says that interpreting heliocentrism as physically real would be "a very dangerous thing, likely not only to irritate all scholastic philosophers and theologians, but also to harm the Holy Faith by rendering Holy Scripture as false." Moreover, while the topic was not inherently a matter of faith, the statements about it in Scripture ''were'' so by virtue of who said them – namely, the Holy Spirit. He conceded that if there were conclusive proof, "then one would have to proceed with great care in explaining the Scriptures that appear contrary; and say rather that we do not understand them, than that what is demonstrated is false." However, demonstrating that heliocentrism merely "saved the appearances" could not be regarded as sufficient to establish that it was physically real. Although he believed that the former may well have been possible, he had "very great doubts" that the latter would be, and in case of doubt it was not permissible to depart from the traditional interpretation of Scriptures. His final argument was a rebuttal of an analogy that Foscarini had made between a moving Earth and a ship on which the passengers perceive themselves as apparently stationary and the receding shore as apparently moving. Bellarmine replied that in the case of the ship the passengers know that their perceptions are erroneous and can mentally correct them, whereas the scientist on the Earth clearly experiences that it is stationary and therefore the perception that the Sun, Moon and stars are moving is not in error and does not need to be corrected.

Bellarmine found no problem with heliocentrism so long as it was treated as a purely hypothetical calculating device and not as a physically real phenomenon, but he did not regard it as permissible to advocate the latter unless it could be conclusively proved through current scientific standards. This put Galileo in a difficult position, because he believed that the available evidence strongly favoured heliocentrism, and he wished to be able to publish his arguments.

Francesco Ingoli

In addition to Bellarmine, Monsignor Francesco Ingoli initiated a debate with Galileo, sending him in January 1616 an essay disputing the Copernican system. Galileo later stated that he believed this essay to have been instrumental in the action against Copernicanism that followed in February. According to philosopher Maurice Finocchiaro, Ingoli had probably been commissioned by the Inquisition to write an expert opinion on the controversy, and the essay provided the "chief direct basis" for the ban. The essay focused on eighteen physical and mathematical arguments against heliocentrism. It borrowed primarily from the arguments of Tycho Brahe, and it notedly mentioned Brahe's argument that heliocentrism required the stars to be much larger than the Sun. Ingoli wrote that the great distance to the stars in the heliocentric theory "clearly proves ... the fixed stars to be of such size, as they may surpass or equal the size of the orbit circle of the Earth itself." Ingoli included four theological arguments in the essay, but suggested to Galileo that he focus on the physical and mathematical arguments. Galileo did not write a response to Ingoli until 1624, in which, among other arguments and evidence, he listed the results of experiments such as dropping a rock from the mast of a moving ship.Inquisition and first judgment, 1616

Deliberation

On February 19, 1616, the Inquisition asked a commission of theologians, known as qualifiers, about the propositions of the heliocentric view of the universe. Historians of the Galileo affair have offered different accounts of why the matter was referred to the qualifiers at this time.Beretta

Fabbrica d'Armi Pietro Beretta (; "Pietro Beretta Weapons Factory") is a privately held Italian firearms manufacturing company operating in several countries. Its firearms are used worldwide for various civilian, law enforcement, and military p ...

points out that the Inquisition had taken a deposition from Gianozzi Attavanti in November 1615, as part of its investigation into the denunciations of Galileo by Lorini and Caccini. In this deposition, Attavanti confirmed that Galileo had advocated the Copernican doctrines of a stationary Sun and a mobile Earth, and as a consequence the Tribunal of the Inquisition would have eventually needed to determine the theological status of those doctrines. It is however possible, as surmised by the Tuscan ambassador, Piero Guiccardini, in a letter to the Grand Duke, that the actual referral may have been precipitated by Galileo's aggressive campaign to prevent the condemnation of Copernicanism.

Judgement

On February 24 the Qualifiers delivered their unanimous report: the proposition that the Sun is stationary at the centre of the universe is "foolish and absurd in philosophy, and formally heretical since it explicitly contradicts in many places the sense of Holy Scripture"; the proposition that the Earth moves and is not at the centre of the universe "receives the same judgement in philosophy; and ... in regard to theological truth it is at least erroneous in faith." The original report document was made widely available in 2014. At a meeting of the cardinals of the Inquisition on the following day,Pope Paul V

Pope Paul V (; ) (17 September 1552 – 28 January 1621), born Camillo Borghese, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 16 May 1605 to his death, in January 1621. In 1611, he honored Galileo Galilei as a mem ...

instructed Bellarmine to deliver this result to Galileo, and to order him to abandon the Copernican opinions; should Galileo resist the decree, stronger action would be taken. On February 26, Galileo was called to Bellarmine's residence and ordered,

With no attractive alternatives, Galileo accepted the orders delivered, even sterner than those recommended by the Pope. Galileo met again with Bellarmine, apparently on friendly terms; and on March 11 he met with the Pope, who assured him that he was safe from prosecution so long as he, the Pope, should live. Nonetheless, Galileo's friends Sagredo and Castelli reported that there were rumors that Galileo had been forced to

With no attractive alternatives, Galileo accepted the orders delivered, even sterner than those recommended by the Pope. Galileo met again with Bellarmine, apparently on friendly terms; and on March 11 he met with the Pope, who assured him that he was safe from prosecution so long as he, the Pope, should live. Nonetheless, Galileo's friends Sagredo and Castelli reported that there were rumors that Galileo had been forced to recant

Recantation is a public denial of a previously publishing, published opinion or belief. The word is derived from the Latin ''re cantare'' ("sing again"). It is related to repentance and revocation.

Philosophy

In philosophy, recantation is link ...

and do penance. To protect his good name, Galileo requested a letter from Bellarmine stating the truth of the matter. This letter assumed great importance in 1633, as did the question whether Galileo had been ordered not to "hold or defend" Copernican ideas (which would have allowed their hypothetical treatment) or not to teach them in any way. If the Inquisition had issued the order not to teach heliocentrism at all, it would have been ignoring Bellarmine's position.

In the end, Galileo did not persuade the Church to stay out of the controversy, but instead saw heliocentrism

Heliocentrism (also known as the heliocentric model) is a superseded astronomical model in which the Earth and planets orbit around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed t ...

formally declared false. It was consequently termed heretical by the Qualifiers, since it contradicted the literal meaning of the Scriptures, though this position was not binding on the Church.

Copernican books banned

Following the Inquisition's injunction against Galileo, the papalMaster of the Sacred Palace

In the Catholic Church, Roman Catholic Church, Theologian of the Pontifical Household () is a Roman Curial office which has always been entrusted to a Friar Preacher of the Dominican Order and may be described as the pope's theologian. The title w ...

ordered that Foscarini's ''Letter'' be banned, and Copernicus' ''De revolutionibus'' suspended until corrected. The papal Congregation of the Index preferred a stricter prohibition, and so with the Pope's approval, on March 5 the Congregation banned all books advocating the Copernican system, which it called "the false Pythagorean doctrine, altogether contrary to Holy Scripture."

Francesco Ingoli, a consultor to the Holy Office, recommended that ''De revolutionibus'' be amended rather than banned due to its utility for calendrics. In 1618, the Congregation of the Index accepted his recommendation, and published their decision two years later, allowing a corrected version of Copernicus' book to be used. The uncorrected ''De revolutionibus'' remained on the Index of banned books until 1758.

Galileo's works advocating Copernicanism were therefore banned, and his sentence prohibited him from "teaching, defending… or discussing" Copernicanism. In Germany, Kepler's works were also banned by the papal order.

''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems''

In 1623,

In 1623, Pope Gregory XV

Pope Gregory XV (; ; 9 January 1554 – 8 July 1623), born Alessandro Ludovisi, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 February 1621 until his death in 1623. He is notable for founding the Congregation for the ...

died and was succeeded by Pope Urban VIII

Pope Urban VIII (; ; baptised 5 April 1568 – 29 July 1644), born Maffeo Vincenzo Barberini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 August 1623 to his death, in July 1644. As pope, he expanded the papal terri ...

who showed greater favor to Galileo, particularly after Galileo traveled to Rome to congratulate the new Pontiff.Youngson, Robert M. ''Scientific Blunders: A Brief History of How Wrong Scientists Can Sometimes Be''; Carroll & Graff Publishers, Inc.; 1998; Pages 290–293

Galileo's ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems

''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'' (''Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo'') is a 1632 book by Galileo Galilei comparing Nicolaus Copernicus's Copernican heliocentrism, heliocentric system model with Ptolemy's geocen ...

'', which was published in 1632 to great popularity, was an account of conversations between a Copernican scientist, Salviati, an impartial and witty scholar named Sagredo, and a ponderous Aristotelian named Simplicio, who employed stock arguments in support of geocentricity, and was depicted in the book as being an intellectually inept fool. Simplicio's arguments are systematically refuted and ridiculed by the other two characters with what Youngson calls "unassailable proof" for the Copernican theory (at least versus the theory of Ptolemy – as Finocchiaro points out, "the Copernican and Tychonic systems were observationally equivalent and the available evidence could be explained equally well by either"), which reduces Simplicio to baffled rage, and makes the author's position unambiguous. Indeed, although Galileo states in the preface of his book that the character is named after a famous Aristotelian philosopher ( Simplicius in Latin, Simplicio in Italian), the name "Simplicio" in Italian also had the connotation of "simpleton." Authors Langford and Stillman Drake asserted that Simplicio was modeled on philosophers Lodovico delle Colombe and Cesare Cremonini. Pope Urban demanded that his own arguments be included in the book, which resulted in Galileo putting them in the mouth of Simplicio. Some months after the book's publication, Pope Urban VIII

Pope Urban VIII (; ; baptised 5 April 1568 – 29 July 1644), born Maffeo Vincenzo Barberini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 August 1623 to his death, in July 1644. As pope, he expanded the papal terri ...

banned its sale and had its text submitted for examination by a special commission.

Trial and second judgment, 1633

With the loss of many of his defenders in Rome because of ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'', in 1633 Galileo was ordered to stand trial on suspicion of heresy "for holding as true the false doctrine taught by some that the sun is the center of the world" against the 1616 condemnation, since "it was decided at the Holy Congregation ..on 25 Feb 1616 that ..the Holy Office would give you an injunction to abandon this doctrine, not to teach it to others, not to defend it, and not to treat of it; and that if you did not acquiesce in this injunction, you should be imprisoned".

Galileo was interrogated while threatened with physical torture. A panel of theologians, consisting of

With the loss of many of his defenders in Rome because of ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'', in 1633 Galileo was ordered to stand trial on suspicion of heresy "for holding as true the false doctrine taught by some that the sun is the center of the world" against the 1616 condemnation, since "it was decided at the Holy Congregation ..on 25 Feb 1616 that ..the Holy Office would give you an injunction to abandon this doctrine, not to teach it to others, not to defend it, and not to treat of it; and that if you did not acquiesce in this injunction, you should be imprisoned".

Galileo was interrogated while threatened with physical torture. A panel of theologians, consisting of Melchior Inchofer

Melchior Inchofer or Imhofer, in Hungarian: Inchofer Menyhért (c. 1584 – 28 September 1648) was an Austrian-Hungarian Jesuit. He played an important part in the trial of Galileo, by his arguments, later published in his ''Tractatus Syllepticu ...

, Agostino Oreggi and Zaccaria Pasqualigo, reported on the ''Dialogue''. Their opinions were strongly argued in favour of the view that the ''Dialogue'' taught the Copernican theory.

Galileo was found guilty, and the sentence of the Inquisition, issued on 22 June 1633, was in three essential parts:

* Galileo was found "vehemently suspect of heresy", namely of having held the opinions that the Sun lies motionless at the centre of the universe, that the Earth is not at its centre and moves, and that one may hold and defend an opinion as probable after it has been declared contrary to Holy Scripture. He was required to "abjure, curse, and detest" those opinions.

* He was sentenced to formal imprisonment at the pleasure of the Inquisition. On the following day this was commuted to house arrest, which he remained under for the rest of his life.

* His offending ''Dialogue'' was banned; and in an action not announced at the trial, publication of any of his works was forbidden, including any he might write in the future.

According to popular legend, after his abjuration Galileo allegedly muttered the rebellious phrase "and yet it moves" (''Eppur si muove''), but there is no evidence that he actually said this or anything similar. The first account of the legend dates to a century after his death. The phrase "Eppur si muove" does appear, however, in a painting of the 1640s by the Spanish painter Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo ( , ; late December 1617, baptized January 1, 1618April 3, 1682) was a Spanish Baroque painter. Although he is best known for his religious works, Murillo also produced a considerable number of paintings of contempor ...

or an artist of his school. The painting depicts an imprisoned Galileo apparently pointing to a copy of the phrase written on the wall of his dungeon.

Siena

Siena ( , ; traditionally spelled Sienna in English; ) is a city in Tuscany, in central Italy, and the capital of the province of Siena. It is the twelfth most populated city in the region by number of inhabitants, with a population of 52,991 ...

, Galileo was allowed to return to his villa at Arcetri near Florence, where he spent the rest of his life under house arrest. He continued his work on mechanics, and in 1638 he published a scientific book in Holland. His standing would remain questioned at every turn. In March 1641, Vincentio Reinieri, a follower and pupil of Galileo, wrote him at Arcetri that an Inquisitor had recently compelled the author of a book printed at Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

to change the words "most distinguished Galileo" to "Galileo, man of noted name".

However, partially in tribute to Galileo, at Arcetri the first academy devoted to the new experimental science, the Accademia del Cimento, was formed, which is where Francesco Redi

Francesco Redi (18 February 1626 – 1 March 1697) was an Italians, Italian physician, naturalist, biologist, and poet. He is referred to as the "founder of experimental biology", and as the "father of modern parasitology". He was the first perso ...

performed controlled experiment

A scientific control is an experiment or observation designed to minimize the effects of variables other than the independent variable (i.e. confounding variables). This increases the reliability of the results, often through a comparison betw ...

s, and many other important advancements were made which would eventually help usher in The Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a European intellectual and philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained through rationalism and empirici ...

.

Modern views

Historians and scholars

Pope Urban VIII had been a patron to Galileo and had given him permission to publish on the Copernican theory as long as he treated it as a hypothesis, but after the publication in 1632, the patronage broke due to Galileo placing Urban's arguments for God's omnipotence, which Galileo had been required to include, in the mouth of a simpleton character named "Simplicio" in the book; this caused great offense to the Pope. There is some evidence that enemies of Galileo persuaded Urban that Simplicio was intended to be a caricature of him. Modern historians have dismissed it as most unlikely that this had been Galileo's intention.See Langford (1966pp. 133–134)

and Seeger (1966

p. 30)

for example. Drake (1978

p. 355)

asserts that Simplicio's character is modelled on the Aristotelian philosophers, Lodovico delle Colombe and Cesare Cremonini, rather than Urban. He also considers that the demand for Galileo to include the Pope's argument in the ''Dialogue'' left him with no option but to put it in the mouth of Simplicio (Drake, 1953, p. 491). Even

Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler (, ; ; ; 5 September 1905 – 1 March 1983) was an Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian-born author and journalist. Koestler was born in Budapest, and was educated in Austria, apart from his early school years. In 1931, Koestler j ...

, who is generally quite harsh on Galileo in '' The Sleepwalkers'' (1959), after noting that Urban suspected Galileo of having intended Simplicio to be a caricature of him, says "this of course is untrue" (1959, p. 483)

Dava Sobel

Dava Sobel (born June 15, 1947) is an American writer of popular expositions of scientific topics. Her books include ''Longitude'', about English clockmaker John Harrison; '' Galileo's Daughter'', about Galileo's daughter Maria Celeste; and ''T ...

argues that during this time, Urban had fallen under the influence of court intrigue and problems of state. His friendship with Galileo began to take second place to his feelings of persecution and fear for his own life. The problem of Galileo was presented to the pope by court insiders and enemies of Galileo, following claims by a Spanish cardinal that Urban was a poor defender of the church. This situation did not bode well for Galileo's defense of his book.

In his 1998 book, ''Scientific Blunders'', Robert Youngson indicates that Galileo struggled for two years against the ecclesiastical censor to publish a book promoting heliocentrism. He claims the book passed only as a result of possible idleness or carelessness on the part of the censor, who was eventually dismissed. On the other hand, Jerome K. Langford and Raymond J. Seeger contend that Pope Urban and the Inquisition gave formal permission to publish the book, ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems

''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'' (''Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo'') is a 1632 book by Galileo Galilei comparing Nicolaus Copernicus's Copernican heliocentrism, heliocentric system model with Ptolemy's geocen ...

, Ptolemaic & Copernican''. They claim Urban personally asked Galileo to give arguments for and against heliocentrism in the book, to include Urban's own arguments, and for Galileo not to advocate heliocentrism.

Some historians emphasize Galileo's confrontation not only with the church, but also with Aristotelian philosophy, either secular or religious.

Views on Galileo's scientific arguments

While Galileo never claimed that his arguments themselves directly proved heliocentrism to be true, they were significant evidence in its favor. According to Finocchiaro, defenders of the Catholic church's position have sometimes attempted to argue, unsuccessfully, that Galileo was right on the facts but that his scientific arguments were weak or unsupported by evidence of the day; Finocchiaro rejects this view, saying that some of Galileo's key epistemological arguments are accepted fact today. Direct evidence ultimately confirmed the motion of the Earth, with the emergence ofNewtonian mechanics

Newton's laws of motion are three physical laws that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. These laws, which provide the basis for Newtonian mechanics, can be paraphrased as follows:

# A body r ...

in the late 17th century, the observation of the stellar aberration

In astronomy, aberration (also referred to as astronomical aberration, stellar aberration, or velocity aberration) is a phenomenon where celestial objects exhibit an apparent motion about their true positions based on the velocity of the obser ...

of light by James Bradley

James Bradley (September 1692 – 13 July 1762) was an English astronomer and priest who served as the third Astronomer Royal from 1742. He is best known for two fundamental discoveries in astronomy, the aberration of light (1725–1728), and ...

in the 18th century, the analysis of orbital motions of binary stars by William Herschel

Frederick William Herschel ( ; ; 15 November 1738 – 25 August 1822) was a German-British astronomer and composer. He frequently collaborated with his younger sister and fellow astronomer Caroline Herschel. Born in the Electorate of Hanover ...

in the 19th century, and the accurate measurement of the stellar parallax

Stellar parallax is the apparent shift of position (''parallax'') of any nearby star (or other object) against the background of distant stars. By extension, it is a method for determining the distance to the star through trigonometry, the stel ...

in the 19th century. According to Christopher Graney, an Adjunct Scholar at the Vatican Observatory, one of Galileo's observations did not support the Copernican heliocentric view, but was more consistent with Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe, ; 14 December 154624 October 1601), generally called Tycho for short, was a Danish astronomer of the Renaissance, known for his comprehensive and unprecedentedly accurate astronomical observations. He ...

's hybrid model where the Earth did not move, and everything else circled around it and the Sun.

Redondi's theory

According to a controversial alternative theory proposed by Pietro Redondi in 1983, the main reason for Galileo's condemnation in 1633 was his attack on the Aristotelian doctrine ofmatter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic pa ...

rather than his defence of Copernicanism. Redondi (1983). An anonymous denunciation, labeled "G3", discovered by Redondi in the Vatican archives, had argued that the atomism

Atomism () is a natural philosophy proposing that the physical universe is composed of fundamental indivisible components known as atoms.

References to the concept of atomism and its Atom, atoms appeared in both Ancient Greek philosophy, ancien ...

espoused by Galileo in his previous work of 1623, ''The Assayer

''The Assayer'' () is a book by Galileo Galilei, published in Rome in October 1623. It is generally considered to be one of the pioneering works of the scientific method, first broaching the idea that the book of nature is to be read with mathem ...

'', was incompatible with the doctrine of transubstantiation

Transubstantiation (; Greek language, Greek: μετουσίωσις ''metousiosis'') is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of sacramental bread, bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and ...

of the Eucharist

The Eucharist ( ; from , ), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an Ordinance (Christianity), ordinance in ...

. At the time, investigation of this complaint was apparently entrusted to a Father Giovanni di Guevara, who was well-disposed towards Galileo, and who cleared ''The Assayer'' of any taint of unorthodoxy. A similar attack against ''The Assayer'' on doctrinal grounds was penned by Jesuit Orazio Grassi in 1626 under the pseudonym "Sarsi". According to Redondi:

* The Jesuits, who had already linked ''The Assayer'' to allegedly heretical atomist ideas, regarded the ideas about matter expressed by Galileo in ''The Dialogue'' as further evidence that his atomism was heretically inconsistent with the doctrine of the Eucharist, and protested against it on these grounds.

* Pope Urban VIII

Pope Urban VIII (; ; baptised 5 April 1568 – 29 July 1644), born Maffeo Vincenzo Barberini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 August 1623 to his death, in July 1644. As pope, he expanded the papal terri ...

, who had been under attack by Spanish cardinals for being too tolerant of heretics, and who had also encouraged Galileo to publish ''The Dialogue'', would have been compromised had his enemies among the Cardinal Inquisitors been given an opening to comment on his support of a publication containing Eucharistic heresies.

* Urban, after banning the book's sale, established a commission to examine ''The Dialogue'', ostensibly for the purpose of determining whether it would be possible to avoid referring the matter to the Inquisition at all, and as a special favor to Galileo's patron, the Grand Duke of Tuscany

Grand may refer to:

People with the name

* Grand (surname)

* Grand L. Bush (born 1955), American actor

Places

* Grand, Oklahoma, USA

* Grand, Vosges, village and commune in France with Gallo-Roman amphitheatre

* Grand County (disambiguation), se ...

. Urban's real purpose, though, was to avoid having the accusations of Eucharistic heresy referred to the Inquisition, and he stacked the commission with friendly commissioners who could be relied upon not to mention them in their report. The commission reported against Galileo.

Redondi's hypothesis concerning the hidden motives behind the 1633 trial has been criticized, and mainly rejected, by other Galileo scholars. However, it has been supported recently, as of 2007, by novelist and science writer Michael White.

Modern Catholic Church views

In 1758 the Catholic Church dropped the general prohibition of books advocating heliocentrism from the ''Index of Forbidden Books

The (English: ''Index of Forbidden Books'') was a changing list of publications deemed heretical or contrary to morality by the Sacred Congregation of the Index (a former dicastery of the Roman Curia); Catholics were forbidden to print o ...

''. Heilbron (2005, p. 307). It did not, however, explicitly rescind the decisions issued by the Inquisition in its judgement of 1633 against Galileo, or lift the prohibition of uncensored versions of Copernicus's ''De Revolutionibus'' or Galileo's ''Dialogue''. The issue finally came to a head in 1820 when the Master of the Sacred Palace (the Church's chief censor), Filippo Anfossi, refused to license a book by a Catholic canon, Giuseppe Settele, because it openly treated heliocentrism as a physical fact. Heilbron (2005, pp. 279, 312–313) Settele appealed to pope Pius VII

Pope Pius VII (; born Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti; 14 August 1742 – 20 August 1823) was head of the Catholic Church from 14 March 1800 to his death in August 1823. He ruled the Papal States from June 1800 to 17 May 1809 and again ...

. After the matter had been reconsidered by the Congregation of the Index and the Holy Office, Anfossi's decision was overturned. Copernicus's ''De Revolutionibus'' and Galileo's ''Dialogue'' were then subsequently omitted from the next edition of the ''Index'' when it appeared in 1835.

In 1979, Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II (born Karol Józef Wojtyła; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 16 October 1978 until Death and funeral of Pope John Paul II, his death in 2005.

In his you ...

expressed the hope that "theologians, scholars and historians, animated by a spirit of sincere collaboration, will study the Galileo case more deeply and in loyal recognition of wrongs, from whatever side they come." However, the Pontifical Interdisciplinary Study Commission constituted in 1981 to study the case did not reach any definitive result. Because of this, the Pope's 1992 speech that closed the project was vague, and did not fulfill his intentions expressed in 1979.

On February 15, 1990, in a speech delivered at La Sapienza University

The Sapienza University of Rome (), formally the Università degli Studi di Roma "La Sapienza", abbreviated simply as Sapienza ('Wisdom'), is a Public university, public research university located in Rome, Italy. It was founded in 1303 and is ...

in Rome,An earlier version had been delivered on December 16, 1989, in Rieti, and a later version in Madrid on February 24, 1990 (Ratzinger, 1994, p. 81). According to Feyerabend himself, Ratzinger had also mentioned him "in support of" his own views in a speech in Parma around the same time (Feyerabend, 1995, p. 178). Cardinal Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI

Pope BenedictXVI (born Joseph Alois Ratzinger; 16 April 1927 – 31 December 2022) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 19 April 2005 until his resignation on 28 February 2013. Benedict's election as p ...

) cited some current views on the Galileo affair as forming what he called "a symptomatic case that illustrates the extent to which modernity’s doubts about itself have grown today in science and technology".Ratzinger (1994, p. 98). As evidence, he presented the views of a few prominent philosophers including Ernst Bloch

Ernst Simon Bloch (; ; July 8, 1885 – August 4, 1977; pseudonyms: Karl Jahraus, Jakob Knerz) was a German Marxist philosopher. Bloch was influenced by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Karl Marx, as well as by apocalyptic and religious thinker ...

and Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker, as well as Paul Feyerabend

Paul Karl Feyerabend (; ; January 13, 1924 – February 11, 1994) was an Austrian philosopher best known for his work in the philosophy of science. He started his academic career as lecturer in the philosophy of science at the University of Bri ...

, whom he quoted as saying:

Ratzinger did not directly say whether he agreed or disagreed with Feyerabend's assertions, but did say in this same context that "It would be foolish to construct an impulsive apologetic on the basis of such views."

In 1992, it was reported that the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

had turned towards vindicating Galileo:

In January 2008, students and professors protested the planned visit of Pope Benedict XVI

Pope BenedictXVI (born Joseph Alois Ratzinger; 16 April 1927 – 31 December 2022) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 19 April 2005 until his resignation on 28 February 2013. Benedict's election as p ...

to La Sapienza University

The Sapienza University of Rome (), formally the Università degli Studi di Roma "La Sapienza", abbreviated simply as Sapienza ('Wisdom'), is a Public university, public research university located in Rome, Italy. It was founded in 1303 and is ...

, stating in a letter that the pope's expressed views on Galileo "offend and humiliate us as scientists who are loyal to reason and as teachers who have dedicated our lives to the advance and dissemination of knowledge". In response the pope canceled his visit. The full text of the speech that would have been given was made available a few days following Pope Benedict's cancelled appearance at the university.

La Sapienza's rector, Renato Guarini, and former Italian Prime Minister Romano Prodi

Romano Prodi (; born 9 August 1939) is an Italian politician who served as President of the European Commission from 1999 to 2004 and twice as Prime Minister of Italy, from 1996 to 1998, and again from 2006 to 2008. Prodi is considered the fo ...

opposed the protest and supported the pope's right to speak.

Also notable were public counter-statements by La Sapienza professors Giorgio Israel; This last citation is a reprint of the original article that appeared in L'Osservatore Romano on January 15, 2008. Scroll down for access. and Bruno Dalla Piccola.

List of artistic treatments

In addition to the large non-fiction literature and the many documentary films about Galileo and the Galileo affair, there have also been several treatments in historical plays and films. The

In addition to the large non-fiction literature and the many documentary films about Galileo and the Galileo affair, there have also been several treatments in historical plays and films. The Museo Galileo

Museo Galileo (formerly ''Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza''; Institute and Museum of the History of Science) is located in Florence, Italy, in Piazza dei Giudici, along the River Arno and close to the Uffizi Gallery. The museum, dedicat ...

has posted a listing of several of the plays. A listing centered on the films was presented in a 2010 article by Cristina Olivotto and Antonella Testa.

*''Galilée'' is a French play by François Ponsard first performed in 1867.

*''Galileo Galilei'' is a short Italian silent film by Luigi Maggi that was released in 1909.

*''Life of Galileo

''Life of Galileo'' (), also known as ''Galileo'', is a Play (theatre), play by the 20th century Germany, German dramatist Bertolt Brecht and collaborator Margarete Steffin with incidental music by Hanns Eisler. The play was written in 1938 and re ...

'' is a play by the German playwright Bertolt Brecht

Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht (10 February 1898 – 14 August 1956), known as Bertolt Brecht and Bert Brecht, was a German theatre practitioner, playwright, and poet. Coming of age during the Weimar Republic, he had his first successes as a p ...

that exists in several versions, including a 1947 version in English written with Charles Laughton

Charles Laughton (; 1 July 1899 – 15 December 1962) was a British and American actor. He was trained in London at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and first appeared professionally on the stage in 1926. In 1927, he was cast in a play wi ...

. The play has been called "Brecht's masterpiece" by Michael Billington of ''The Guardian'' British newspaper. Joseph Losey

Joseph Walton Losey III (; January 14, 1909 – June 22, 1984) was an American film and theatre director, producer, and screenwriter. Born in Wisconsin, he studied in Germany with Bertolt Brecht and then returned to the United States. Hollywood ...

, who directed the first productions of the English language version in 1947, made a film based on the play that was released in 1975.

*'' Lamp at Midnight'' is a play by Barrie Stavis that was first performed in 1947. An adaptation of the play was televised in 1964; it was directed by George Schaefer. A recording was released as a VHS tape in the 1980s.

*''Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

'' is a 1968 Italian film written and directed by Liliana Cavani

Liliana Cavani (born 12 January 1933) is an Italian film director and screenwriter. Cavani became internationally known after the success of her 1974 feature film ''Il portiere di notte'' ('' The Night Porter''). Her films have historical concerns ...

.

*''Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

'' is an opera with music by Philip Glass

Philip Glass (born January 31, 1937) is an American composer and pianist. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential composers of the late 20th century. Glass's work has been associated with minimal music, minimalism, being built up fr ...

and a libretto by Mary Zimmerman

Mary Zimmerman (born August 23, 1960) is an American theatre and opera director and playwright from Nebraska. She is an ensemble member of the Lookingglass Theatre Company, the Manilow Resident Director at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago, Illinoi ...

. It was first performed in 2002.

See also

*Aristarchus of Samos

Aristarchus of Samos (; , ; ) was an ancient Greek astronomer and mathematician who presented the first known heliocentric model that placed the Sun at the center of the universe, with the Earth revolving around the Sun once a year and rotati ...

* Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno ( , ; ; born Filippo Bruno; January or February 1548 – 17 February 1600) was an Italian philosopher, poet, alchemist, astrologer, cosmological theorist, and esotericist. He is known for his cosmological theories, which concep ...

* Catholic Church and science

* Conflict thesis

* Vincenzo Maculani

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * A searchable online copy is available on thInstitute and Museum of the History of Science

Florence, and a brief overview of ''Le Opere'' is available at , an

* * * * * * * * * * * * * Original edition published by Hutchinson (London). * . Original edition by Desclee (New York, 1966) * * McMullen, Emerson Thomas, ''Galileo's condemnation: The real and complex story'' (Georgia Journal of Science, vol. 61(2) 2003) * * * * * . * * * * * * Speller, Jules, ''Galileo's Inquisition Trial Revisited '', Peter Lang Europäischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2008. 431 pp. / US- * * * * *

External links

lecture ( ttps://web.archive.org/web/20110108175957/http://thomasaquinas.edu/news/recent_events/Galileo_Galilei-Scripture_Exegete.mp3 audio here by Thomas Aquinas College tutor Dr. Christopher Decaen

"The End of the Myth of Galileo Galilei"

by

''The Starry Messenger'' (1610)

. An English translation fro

Bard College

Original Latin text a

LiberLiber

online library.

Galileo's letter to Castelli of 1613

The English translation given on the web page at this link is from Finocchiaro (1989), contrary to the claim made in the citation given on the page itself.

Galileo's letter to the Grand Duchess Christina of 1615

Extensively documented series of lectures by William E. Carroll and Peter Hodgson.

Edizione Nationale

. A searchable online copy of Favaro's National Edition of Galileo's works at the website of th

Florence. {{Authority control 17th-century Catholicism 17th century in science Astronomical controversies Cognitive inertia Copernican Revolution Events relating to freedom of expression Galileo Galilei History of astronomy Inquisition Pope Paul V 1610 beginnings 1633 endings