Freudo-Marxism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Freudo-Marxism is a loose designation for philosophical perspectives informed by both the

The Slovenian philosopher

The Slovenian philosopher

Roger Kimball: ''The Marriage of Marx and Freud''

{{Wilhelm Reich Marxist schools of thought Critical theory Freudian psychology Wilhelm Reich

Marxist philosophy

Marxist philosophy or Marxist theory are works in philosophy that are strongly influenced by Karl Marx's Historical materialism, materialist approach to theory, or works written by Marxists. Marxist philosophy may be broadly divided into Wester ...

of Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

and the psychoanalytic theory

Psychoanalytic theory is the theory of the innate structure of the human soul and the dynamics of personality development relating to the practice of psychoanalysis, a method of research and for treating of Mental disorder, mental disorders (psych ...

of Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( ; ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating psychopathology, pathologies seen as originating fro ...

. Its history within continental philosophy

Continental philosophy is a group of philosophies prominent in 20th-century continental Europe that derive from a broadly Kantianism, Kantian tradition.Continental philosophers usually identify such conditions with the transcendental subject or ...

began in the 1920s and '30s and running since through critical theory

Critical theory is a social, historical, and political school of thought and philosophical perspective which centers on analyzing and challenging systemic power relations in society, arguing that knowledge, truth, and social structures are ...

, Lacanian psychoanalysis

Lacanianism or Lacanian psychoanalysis is a theoretical system initiated by the work of Jacques Lacan from the 1950s to the 1980s. It is a theoretical approach that attempts to explain the mind, behaviour, and culture through a structuralism, str ...

, and post-structuralism

Post-structuralism is a philosophical movement that questions the objectivity or stability of the various interpretive structures that are posited by structuralism and considers them to be constituted by broader systems of Power (social and poli ...

.

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud engages with Marxism in his 1932 New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, in which he hesitantly contests what he sees as the Marxist view of history. According to Freud, Marx erroneously attributes the trajectory of society to a necessary "natural law or conceptual ialecticalevolution"; instead, Freud suggests, it can be attributed to contingent factors: "psychological factors, such as the amount of constitutional aggressiveness", "the firmness of the organization within the horde" and "material factors, such as the possession of superior weapons". However, Freud does not completely dismiss Marxism: "The strength of Marxism clearly lies, not in its view of history or its prophecies of the future that are based on it, but in its sagacious indication of the decisive influence which the economic circumstances of men have upon their intellectual, ethical and artistic attitudes."Emergence

The beginnings of Freudo-Marxist theorizing took place in the 1920s in Germany and the Soviet Union. The Soviet pedagogist Aron Zalkind was the most prominent proponent of Marxist psychoanalysis in the Soviet Union. The Soviet philosopher V. Yurinets and the Freudian analyst Siegfried Bernfeld both discussed the topic. The Soviet linguist Valentin Voloshinov, a member of the Bakhtin circle, began a Marxist critique of psychoanalysis in his 1925 article "Beyond the Social", which he developed more substantially in his 1927 book ''Freudianism: A Marxist Critique''. In 1929,Wilhelm Reich

Wilhelm Reich ( ; ; 24 March 1897 – 3 November 1957) was an Austrian Doctor of Medicine, doctor of medicine and a psychoanalysis, psychoanalyst, a member of the second generation of analysts after Sigmund Freud. The author of several in ...

's ''Dialectical Materialism and Psychoanalysis'' was published in German and Russian in the bilingual communist theory journal ''.'' At the end of this line of thought can be considered Otto Fenichel

Otto Fenichel (; 2 December 1897, Vienna – 22 January 1946, Los Angeles) was an Austrian psychoanalyst of the so-called "second generation". He was born into a prominent family of Jewish lawyers.

Education and psychoanalytic affiliations

Otto ...

's 1934 article ''Psychoanalysis as the Nucleus of a Future Dialectical-Materialistic Psychology'' which appeared in Reich's . One member of the Berlin group of Marxist psychoanalysts around Reich was Erich Fromm

Erich Seligmann Fromm (; ; March 23, 1900 – March 18, 1980) was a German-American social psychologist, psychoanalyst, sociologist, humanistic philosopher, and democratic socialist. He was a German Jew who fled the Nazi regime and set ...

, who later brought Freudo-Marxist ideas into the exiled Frankfurt School

The Frankfurt School is a school of thought in sociology and critical theory. It is associated with the University of Frankfurt Institute for Social Research, Institute for Social Research founded in 1923 at the University of Frankfurt am Main ...

led by Max Horkheimer

Max Horkheimer ( ; ; 14 February 1895 – 7 July 1973) was a German philosopher and sociologist best known for his role in developing critical theory as director of the Institute for Social Research, commonly associated with the Frankfurt Schoo ...

and Theodor W. Adorno

Theodor W. Adorno ( ; ; born Theodor Ludwig Wiesengrund; 11 September 1903 – 6 August 1969) was a German philosopher, musicologist, and social theorist. He was a leading member of the Frankfurt School of critical theory, whose work has com ...

.

Wilhelm Reich

Wilhelm Reich

Wilhelm Reich ( ; ; 24 March 1897 – 3 November 1957) was an Austrian Doctor of Medicine, doctor of medicine and a psychoanalysis, psychoanalyst, a member of the second generation of analysts after Sigmund Freud. The author of several in ...

was an Austrian psychoanalyst, a member of the second generation of psychoanalysts after Freud, and a radical psychiatrist

A psychiatrist is a physician who specializes in psychiatry. Psychiatrists are physicians who evaluate patients to determine whether their symptoms are the result of a physical illness, a combination of physical and mental ailments or strictly ...

. He was the author of several influential books and essays, most notably '' Character Analysis'' (1933), '' The Mass Psychology of Fascism'' (1933), and '' The Sexual Revolution'' (1936). His work on character contributed to the development of Anna Freud

Anna Freud CBE ( ; ; 3 December 1895 – 9 October 1982) was a British psychoanalyst of Austrian Jewish descent. She was born in Vienna, the sixth and youngest child of Sigmund Freud and Martha Bernays. She followed the path of her father a ...

's '' The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defence'' (1936), and his idea of muscular armour – the expression of the personality in the way the body moves – shaped innovations such as body psychotherapy, Fritz Perls

Friedrich Salomon Perls (July 8, 1893 – March 14, 1970), better known as Fritz Perls, was a German-born psychiatrist, psychoanalyst and psychotherapist. Perls coined the term "Gestalt therapy" to identify the form of psychotherapy that he devel ...

's Gestalt therapy

Gestalt therapy is a form of psychotherapy that emphasizes Responsibility assumption, personal responsibility and focuses on the individual's experience in the present moment, the therapist–client relationship, the environmental and social c ...

, Alexander Lowen's bioenergetic analysis, and Arthur Janov

Arthur Janov (; August 21, 1924October 1, 2017), also known as Art Janov, was an American psychologist, psychotherapist, and writer. He gained notability as the creator of primal therapy, a treatment for mental illness that involves repeatedly de ...

's primal therapy

Primal therapy is a Psychological trauma, trauma-based psychotherapy created by Arthur Janov during the 1960s, who argued that neurosis is caused by the Psychological repression, repressed Psychological pain, pain of childhood trauma. Janov argued ...

. His writing influenced generations of intellectuals: during the 1968 student uprisings in Paris and Berlin, students scrawled his name on walls and threw copies of ''The Mass Psychology of Fascism'' at the police.

Critical theory

Frankfurt School

TheFrankfurt School

The Frankfurt School is a school of thought in sociology and critical theory. It is associated with the University of Frankfurt Institute for Social Research, Institute for Social Research founded in 1923 at the University of Frankfurt am Main ...

, from the Institute for Social Research Institute for Social Research may refer to:

* Norwegian Institute for Social Research, a private research institute in Oslo, Norway

* University of Frankfurt Institute for Social Research, a research institute in Frankfurt, Germany

* University of ...

, took up the task of choosing what parts of Marx's thought might serve to clarify social conditions which Marx himself had never seen. They drew on other schools of thought to fill in Marx's perceived omissions. Max Weber

Maximilian Carl Emil Weber (; ; 21 April 186414 June 1920) was a German Sociology, sociologist, historian, jurist, and political economy, political economist who was one of the central figures in the development of sociology and the social sc ...

exerted a major influence, as did Freud. In the Institute's extensive (ed. Max Horkheimer

Max Horkheimer ( ; ; 14 February 1895 – 7 July 1973) was a German philosopher and sociologist best known for his role in developing critical theory as director of the Institute for Social Research, commonly associated with the Frankfurt Schoo ...

, Paris 1936), Erich Fromm

Erich Seligmann Fromm (; ; March 23, 1900 – March 18, 1980) was a German-American social psychologist, psychoanalyst, sociologist, humanistic philosopher, and democratic socialist. He was a German Jew who fled the Nazi regime and set ...

authored the social-psychological part. Another new member of the institute was Herbert Marcuse

Herbert Marcuse ( ; ; July 19, 1898 – July 29, 1979) was a German–American philosopher, social critic, and Political philosophy, political theorist, associated with the Frankfurt School of critical theory. Born in Berlin, Marcuse studied at ...

, who would become famous during the 1950s in the US.

Herbert Marcuse

''Eros and Civilization

''Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud'' (1955; second edition, 1966) is a book by the German philosopher and social critic Herbert Marcuse, in which the author proposes a non-repressive society, attempts a synthesis of the t ...

'' is one of Marcuse's best known early works. Written in 1955, it is an attempted dialectical synthesis of Marx and Freud whose title alludes to Freud's '' Civilization and its Discontents''. Marcuse's vision of a non-repressive society (which runs rather counter to Freud's conception of society as naturally and necessarily repressive), based on Marx and Freud, anticipated the values of 1960s countercultural

A counterculture is a culture whose values and norms of behavior differ substantially from those of mainstream society, sometimes diametrically opposed to mainstream cultural mores.Eric Donald Hirsch. ''The Dictionary of Cultural Literacy''. Ho ...

social movements.

In the book, Marcuse writes about the social meaning of biology – history seen not as a class struggle

In political science, the term class conflict, class struggle, or class war refers to the economic antagonism and political tension that exist among social classes because of clashing interests, competition for limited resources, and inequali ...

, but fight against repression of our instincts. He argues that capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

(if never named as such) is preventing us from reaching the non-repressive society "based on a fundamentally different experience of being, a fundamentally different relation between man and nature, and fundamentally different existential relations".

Erich Fromm

Erich Fromm, once a member of theFrankfurt School

The Frankfurt School is a school of thought in sociology and critical theory. It is associated with the University of Frankfurt Institute for Social Research, Institute for Social Research founded in 1923 at the University of Frankfurt am Main ...

, left the group at the end of the 1930s. The culmination of Fromm's social and political philosophy was his book ''The Sane Society'', published in 1955, which argued in favor of humanist, democratic socialism

Democratic socialism is a left-wing economic ideology, economic and political philosophy that supports political democracy and some form of a socially owned economy, with a particular emphasis on economic democracy, workplace democracy, and wor ...

. Building primarily upon the works of Marx, Fromm sought to re-emphasise the ideal of personal freedom, missing from most Soviet Marxism, and more frequently found in the writings of classic liberals. Fromm's brand of socialism rejected both Western capitalism and Soviet communism, which he saw as dehumanizing and bureaucratic social structures that resulted in a virtually universal modern phenomenon of alienation.

Other developments

Frantz Fanon

The French West Indian psychiatrist and philosopherFrantz Fanon

Frantz Omar Fanon (, ; ; 20 July 1925 – 6 December 1961) was a French West Indian psychiatrist, political philosopher, and Marxist from the French colony of Martinique (today a French department). His works have become influential in the ...

drew on both psychoanalytic and Marxist theory in his critique of colonialism

Colonialism is the control of another territory, natural resources and people by a foreign group. Colonizers control the political and tribal power of the colonised territory. While frequently an Imperialism, imperialist project, colonialism c ...

. His seminal works in this area include '' Black Skin, White Masks'' (1952) and '' The Wretched of the Earth'' (1961).

Paul Ricœur

In his 1965 book '' Freud and Philosophy: An Essay on Interpretation'', the French philosopherPaul Ricœur

Jean Paul Gustave Ricœur (; ; 27 February 1913 – 20 May 2005) was a French philosopher best known for combining phenomenological description with hermeneutics. As such, his thought is within the same tradition as other major hermeneut ...

compared the two (together with Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philology, classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche bec ...

), characterizing their common method as the " hermeneutics of suspicion".

Lacanianism

Jacques Lacan

Jacques Marie Émile Lacan (, ; ; 13 April 1901 – 9 September 1981) was a French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist. Described as "the most controversial psycho-analyst since Sigmund Freud, Freud", Lacan gave The Seminars of Jacques Lacan, year ...

was a philosophically minded French psychoanalyst, whose perspective gained widespread influence in French psychiatry and psychology. Lacan saw himself as loyal to and rescuing Freud's legacy. In his 16th Seminar

A seminar is a form of academic instruction, either at an academic institution or offered by a commercial or professional organization. It has the function of bringing together small groups for recurring meetings, focusing each time on some part ...

, , Lacan proposes and develops a homology between the Marxist notion of surplus value

In Marxian economics, surplus value is the difference between the amount raised through a sale of a product and the amount it cost to manufacture it: i.e. the amount raised through sale of the product minus the cost of the materials, plant and ...

and his own notion of . While Lacan was not himself a Marxist, many Marxists (particularly Maoists

Maoism, officially Mao Zedong Thought, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed while trying to realize a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of China and later the People's Re ...

) drew on his ideas.

Louis Althusser

The French Marxist philosopherLouis Althusser

Louis Pierre Althusser (, ; ; 16 October 1918 – 22 October 1990) was a French Marxist philosopher who studied at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, where he eventually became Professor of Philosophy.

Althusser was a long-time member an ...

is widely known as a theorist of ideology

An ideology is a set of beliefs or values attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely about belief in certain knowledge, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones". Form ...

, and his best-known essay is '' Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses: Notes Toward an Investigation''. The essay establishes the concept of ideology, also based on Gramsci's theory of hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one State (polity), state over other states, either regional or global.

In Ancient Greece (ca. 8th BC – AD 6th c.), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of ...

. Whereas hegemony is ultimately determined entirely by political forces, ideology draws on Freud's and Lacan's concepts of the unconscious and mirror-phase respectively, and describes the structures and systems that allow us to meaningfully have a concept of the self

In philosophy, the self is an individual's own being, knowledge, and values, and the relationship between these attributes.

The first-person perspective distinguishes selfhood from personal identity. Whereas "identity" is (literally) same ...

. These structures, for Althusser, are both agents of repression and inevitable – it is impossible to escape ideology, to not be subjected to it. The distinction between ideology and science or philosophy is not assured once and for all by the '' epistemological break'' (a term borrowed from Gaston Bachelard

Gaston Bachelard (; ; 27 June 1884 – 16 October 1962) was a French philosopher. He made contributions in the fields of poetics and the philosophy of science. To the latter, he introduced the concepts of ''epistemological obstacle'' and ''Epist ...

): this "break" is not a chronologically determined event, but a process. Instead of an assured victory, there is a continuous struggle against ideology: "Ideology has no history".

His essay ''Contradiction and Overdetermination'' borrows the concept of overdetermination

Overdetermination occurs when a single-observed effect is determined by multiple causes, any one of which alone would be conceivably sufficient to account for ("determine") the effect. The term "overdetermination" () was used by Sigmund Freud a ...

from psychoanalysis, in order to replace the idea of "contradiction" with a more complex model of multiple causality in political situations (an idea closely related to Gramsci's concept of hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one State (polity), state over other states, either regional or global.

In Ancient Greece (ca. 8th BC – AD 6th c.), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of ...

).

Cornelius Castoriadis

Greek-French philosopher, psychoanalyst, and social criticCornelius Castoriadis

Cornelius Castoriadis (; 11 March 1922 – 26 December 1997) was a Greeks in France, Greek-FrenchMemos 2014, p. 18: "he was ... granted full French citizenship in 1970." philosopher, sociologist, social critic, economist, psychoanalyst, au ...

also followed up on the work of Lacan.

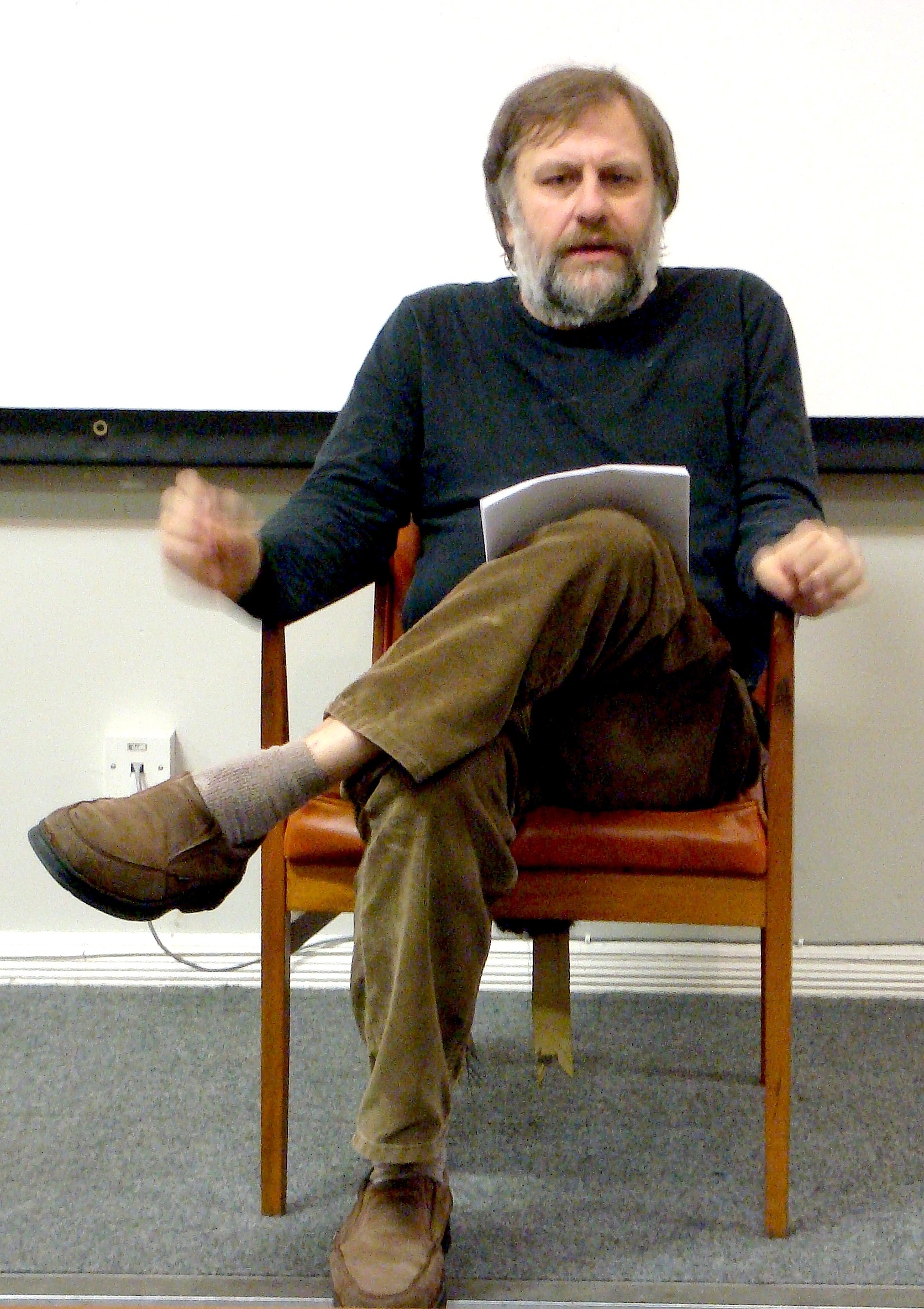

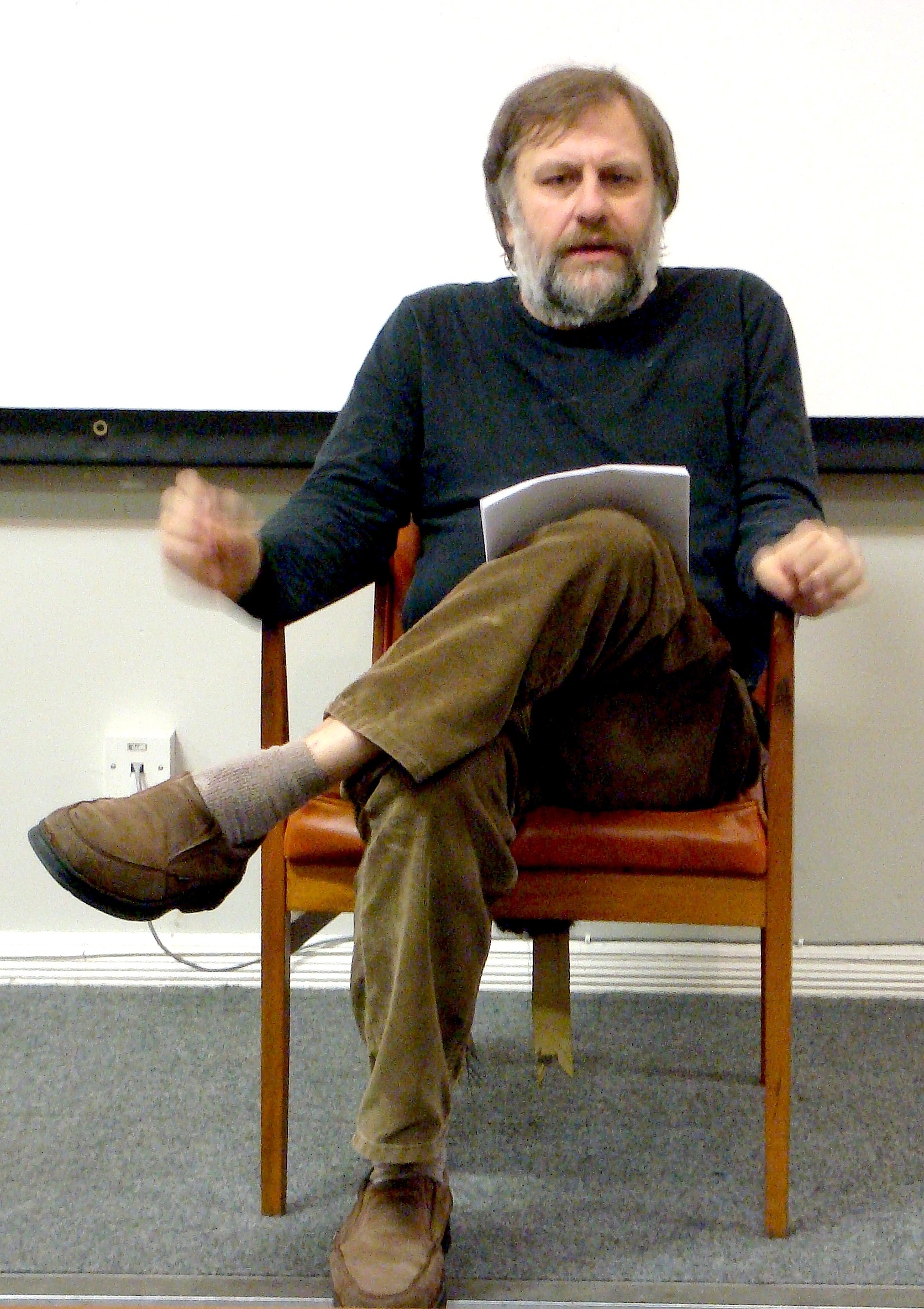

Slavoj Žižek

The Slovenian philosopher

The Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek

Slavoj Žižek ( ; ; born 21 March 1949) is a Slovenian Marxist philosopher, cultural theorist and public intellectual.

He is the international director of the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities at the University of London, Global Distin ...

promotes a form of Marxism highly modified by Lacanian psychoanalysis

PsychoanalysisFrom Greek language, Greek: and is a set of theories and techniques of research to discover unconscious mind, unconscious processes and their influence on conscious mind, conscious thought, emotion and behaviour. Based on The Inte ...

and Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealism, German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political phi ...

ian philosophy. Žižek contests Althusser's account of ideology, because it misses the role of subjectivity

The distinction between subjectivity and objectivity is a basic idea of philosophy, particularly epistemology and metaphysics. Various understandings of this distinction have evolved through the work of countless philosophers over centuries. One b ...

.

Post-structuralism

Major French philosophers associated withpost-structuralism

Post-structuralism is a philosophical movement that questions the objectivity or stability of the various interpretive structures that are posited by structuralism and considers them to be constituted by broader systems of Power (social and poli ...

, post-modernism

Postmodernism encompasses a variety of artistic, cultural, and philosophical movements that claim to mark a break from modernism. They have in common the conviction that it is no longer possible to rely upon previous ways of depicting the wor ...

, and/or deconstruction

In philosophy, deconstruction is a loosely-defined set of approaches to understand the relationship between text and meaning. The concept of deconstruction was introduced by the philosopher Jacques Derrida, who described it as a turn away from ...

, including Jean-François Lyotard

Jean-François Lyotard (; ; 10 August 1924 – 21 April 1998) was a French philosopher, sociologist, and literary theorist. His interdisciplinary discourse spans such topics as epistemology and communication, the human body, modern art and p ...

, Michel Foucault

Paul-Michel Foucault ( , ; ; 15 October 192625 June 1984) was a French History of ideas, historian of ideas and Philosophy, philosopher who was also an author, Literary criticism, literary critic, Activism, political activist, and teacher. Fo ...

, and Jacques Derrida

Jacques Derrida (; ; born Jackie Élie Derrida;Peeters (2013), pp. 12–13. See also 15 July 1930 – 9 October 2004) was a French Algerian philosopher. He developed the philosophy of deconstruction, which he utilized in a number of his texts, ...

, engaged deeply with both Marxism and psychoanalysis. Most notably, Gilles Deleuze

Gilles Louis René Deleuze (18 January 1925 – 4 November 1995) was a French philosopher who, from the early 1950s until his death in 1995, wrote on philosophy, literature, film, and fine art. His most popular works were the two volumes o ...

and Félix Guattari

Pierre-Félix Guattari ( ; ; 30 March 1930 – 29 August 1992) was a French psychoanalyst, political philosopher, Semiotics, semiotician, social activist, and screenwriter. He co-founded schizoanalysis with Gilles Deleuze, and created ecosophy ...

collaborated on the theoretical work '' Capitalism and Schizophrenia'' in two volumes: ''Anti-Oedipus

''Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia'' () is a 1972 book by French authors Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, the former a philosopher and the latter a psychoanalyst. It is the first volume of their collaborative work ''Capitalism and Sch ...

'' (1972) and ''A Thousand Plateaus

''A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia'' () is a 1980 book by the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze and the French psychoanalyst Félix Guattari. It is the second and final volume of their collaborative work '' Capitalism and Schizop ...

'' (1980).

Major works

*''Freudianism: A Marxist Critique'' (1927) by Valentin Voloshinov *'' Character Analysis'' (1933) byWilhelm Reich

Wilhelm Reich ( ; ; 24 March 1897 – 3 November 1957) was an Austrian Doctor of Medicine, doctor of medicine and a psychoanalysis, psychoanalyst, a member of the second generation of analysts after Sigmund Freud. The author of several in ...

*'' Black Skin, White Masks'' (1952) by Frantz Fanon

Frantz Omar Fanon (, ; ; 20 July 1925 – 6 December 1961) was a French West Indian psychiatrist, political philosopher, and Marxist from the French colony of Martinique (today a French department). His works have become influential in the ...

*'' Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud'' (1955) by Herbert Marcuse

Herbert Marcuse ( ; ; July 19, 1898 – July 29, 1979) was a German–American philosopher, social critic, and Political philosophy, political theorist, associated with the Frankfurt School of critical theory. Born in Berlin, Marcuse studied at ...

*''The Sane Society'' (1955) by Erich Fromm

Erich Seligmann Fromm (; ; March 23, 1900 – March 18, 1980) was a German-American social psychologist, psychoanalyst, sociologist, humanistic philosopher, and democratic socialist. He was a German Jew who fled the Nazi regime and set ...

*'' Life Against Death: The Psychoanalytical Meaning of History'' (1959) by Norman O. Brown

*''Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses

"Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes Towards an Investigation)" ( French: "Idéologie et appareils idéologiques d'État (Notes pour une recherche)") is an essay by the French Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser. First published in ...

'' (1970) by Louis Althusser

Louis Pierre Althusser (, ; ; 16 October 1918 – 22 October 1990) was a French Marxist philosopher who studied at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, where he eventually became Professor of Philosophy.

Althusser was a long-time member an ...

*'' Capitalism and Schizophrenia'' (1972/1980) by Gilles Deleuze

Gilles Louis René Deleuze (18 January 1925 – 4 November 1995) was a French philosopher who, from the early 1950s until his death in 1995, wrote on philosophy, literature, film, and fine art. His most popular works were the two volumes o ...

and Félix Guattari

Pierre-Félix Guattari ( ; ; 30 March 1930 – 29 August 1992) was a French psychoanalyst, political philosopher, Semiotics, semiotician, social activist, and screenwriter. He co-founded schizoanalysis with Gilles Deleuze, and created ecosophy ...

*'' Libidinal Economy'' (1974) by Jean-François Lyotard

Jean-François Lyotard (; ; 10 August 1924 – 21 April 1998) was a French philosopher, sociologist, and literary theorist. His interdisciplinary discourse spans such topics as epistemology and communication, the human body, modern art and p ...

*''False Consciousness: An Essay on Reification'' by Joseph Gabel

Joseph Gabel (12 July 1912 in Budapest – 15 June 2004 in Paris) was a French Hungarian-born sociology, sociologist and philosophy, philosopher. His work was always strongly influenced by Marxism; he was against Stalinism and critical of the work ...

*'' The Sublime Object of Ideology'' (1989) by Slavoj Žižek

Slavoj Žižek ( ; ; born 21 March 1949) is a Slovenian Marxist philosopher, cultural theorist and public intellectual.

He is the international director of the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities at the University of London, Global Distin ...

See also

*Class consciousness

In Marxism, class consciousness is the set of beliefs that persons hold regarding their social class or economic rank in society, the structure of their class, and their common class interests. According to Karl Marx, class consciousness is an awa ...

* Crowd psychology

Crowd psychology (or mob psychology) is a subfield of social psychology which examines how the psychology of a group of people differs from the psychology of any one person within the group. The study of crowd psychology looks into the actions ...

* Critical psychology

* Critique of political economy

Critique of political economy or simply the first critique of economy is a form of social critique that rejects the conventional ways of distributing resources. The critique also rejects what its advocates believe are unrealistic axioms, flawe ...

References

Bibliography

*Further reading

* * * * *External links

Roger Kimball: ''The Marriage of Marx and Freud''

{{Wilhelm Reich Marxist schools of thought Critical theory Freudian psychology Wilhelm Reich