French Battleship Patrie on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Patrie'' was the second and final member of the of

''Patrie'' joined ''République'', ''Justice'', ''Vérité'', ''Démocratie'', and ''Suffren'' for a simulated attack on the port of

''Patrie'' joined ''République'', ''Justice'', ''Vérité'', ''Démocratie'', and ''Suffren'' for a simulated attack on the port of

pre-dreadnought battleship

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built from the mid- to late- 1880s to the early 1900s. Their designs were conceived before the appearance of in 1906 and their classification as "pre-dreadnought" is retrospectively appli ...

s of the French Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the Navy, maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of History of France, France. It is among the largest and most powerful List of navies, naval forces i ...

built between her keel laying

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a shipbuilding, ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel l ...

in April 1902 and her commissioning

Commissioning is a process or service provided to validate the completeness and accuracy of a project or venture.

It may refer more specifically to:

* Project commissioning, a process of assuring that all components of a facility are designed, in ...

in July 1907. Armed with a main battery of four guns, she was outclassed before even entering service by the revolutionary British battleship , that had been commissioned the previous December and was armed with a battery of ten guns of the same caliber. Though built to an obsolescent design, ''Patrie'' proved to be a workhorse of the French fleet, particularly during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

.

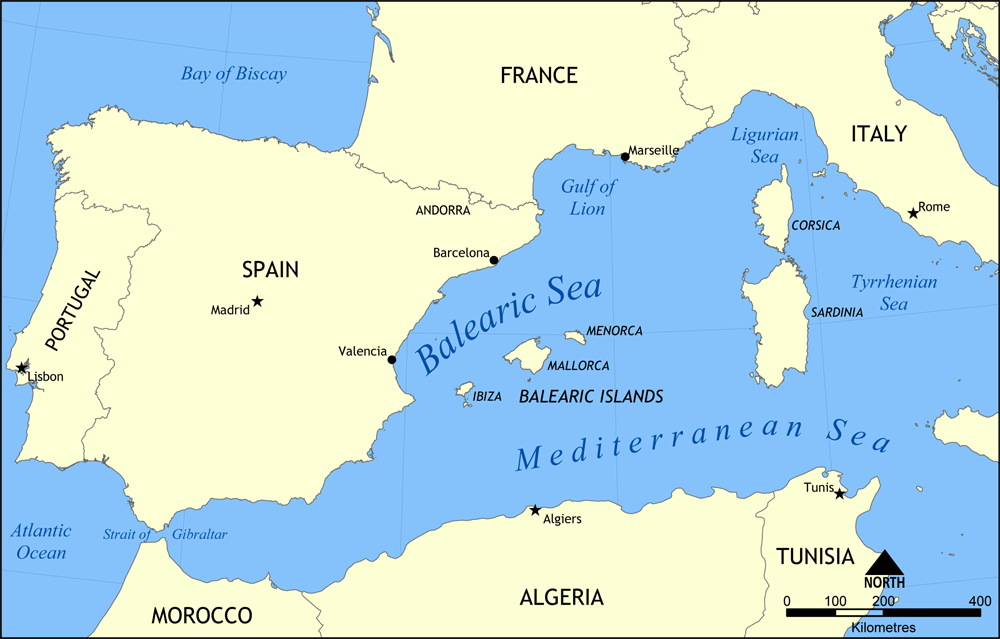

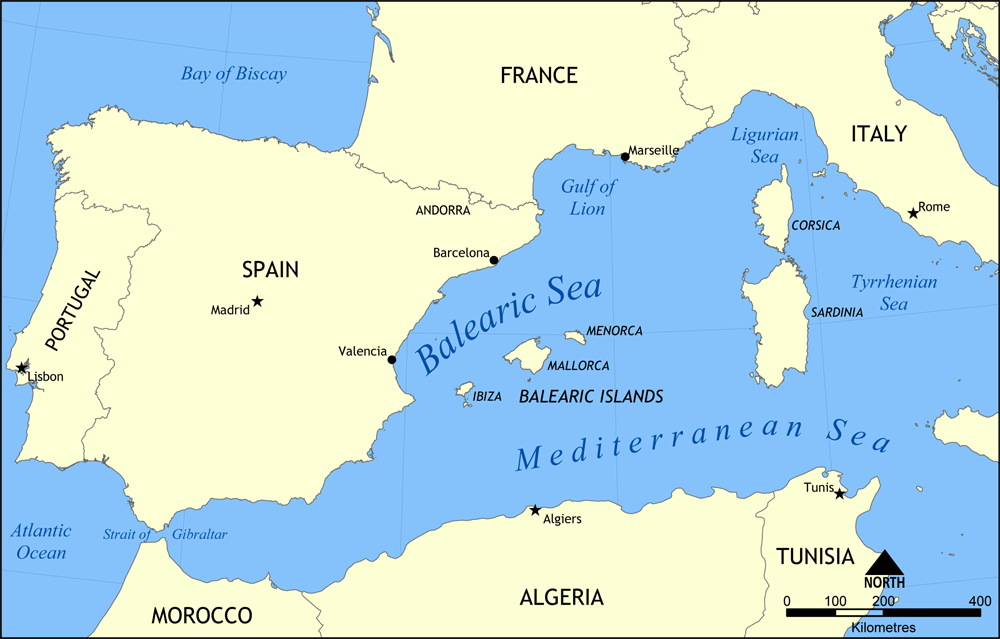

During the ship's peacetime career, ''Patrie'' served with the Mediterranean Squadron; this period was occupied with training exercises and cruises in the western Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

and the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

. She served as the squadron's flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

until replaced by newer vessels in 1911. Following the outbreak of war in July 1914, ''Patrie'' was used to escort troopship

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable to land troops directly on shore, typic ...

convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

s carrying elements of the French Army from French North Africa

French North Africa (, sometimes abbreviated to ANF) is a term often applied to the three territories that were controlled by France in the North African Maghreb during the colonial era, namely Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. In contrast to French ...

to face the Germans invading northern France. She thereafter steamed to contain the Austro-Hungarian Navy

The Austro-Hungarian Navy or Imperial and Royal War Navy (, in short ''k.u.k. Kriegsmarine'', ) was the navy, naval force of Austria-Hungary. Ships of the Austro-Hungarian Navy were designated ''SMS'', for ''Seiner Majestät Schiff'' (His Majes ...

in the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

, taking part in the minor Battle of Antivari

The Battle of Antivari or Action off Antivari was a naval engagement between a large fleet of French and British warships and two ships of the Austro-Hungarian navy at the start of the First World War. The old Austrian protected cruiser and the ...

in August. The increasing threat of Austro-Hungarian U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

s and the unwillingness of the Austro-Hungarian fleet to engage in battle led to a period of inactivity that ended with a transfer of the vessel to the Dardanelles Division fighting in the Gallipoli Campaign, where she bombarded Ottoman forces.

Following the Allied withdrawal from Gallipoli in 1916, ''Patrie'' became involved in events in Greece, being stationed in Salonika

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

to put pressure on the Greek government to enter the war on the side of the Allies. She contributed men to a landing party that went ashore in Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

to support a pro-Allied coup. She saw little activity in 1917 and 1918 after the coup succeeded. Following the end of the war in late 1918, she was sent to Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

to support the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War

The Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War consisted of a series of multi-national military expeditions that began in 1918. The initial impetus behind the interventions was to secure munitions and supply depots from falling into the German ...

, though she took no active role and served as a barracks ship

A barracks ship or barracks barge or berthing barge, or in civilian use accommodation vessel or accommodation ship, is a ship or a non-self-propelled barge containing a superstructure of a type suitable for use as a temporary barracks for sai ...

. She then became a training ship

A training ship is a ship used to train students as sailors. The term is mostly used to describe ships employed by navies to train future officers. Essentially there are two types: those used for training at sea and old hulks used to house class ...

, a role she filled in one capacity or another until 1936, when she was withdrawn from service and sold for scrap

Scrap consists of recyclable materials, usually metals, left over from product manufacturing and consumption, such as parts of vehicles, building supplies, and surplus materials. Unlike waste, scrap can have monetary value, especially recover ...

the following year.

Design

The ships of the ''République'' class marked a significant improvement over earlier French battleships, being significantly larger and better-armed and armored than the preceding battleship . Designed byLouis-Émile Bertin

Louis-Émile Bertin (; 23 March 1840 – 22 October 1924) was a French naval engineer, one of the foremost of his time, and a proponent of the "Jeune École" philosophy of using light, but powerfully armed warships instead of large battleships. ...

, the ships incorporated a new armor layout that included a more comprehensive armored citadel that would better resist flooding than the shallow side armor used in earlier vessels.

''Patrie'' was long overall and had a beam of and an average draft

Draft, the draft, or draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a v ...

of . She displaced at full load. She was powered by three vertical triple expansion engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be transf ...

s with twenty-four Niclausse boilers. They were rated at and provided a top speed of . Coal storage amounted to , which provided a maximum range of at a cruising speed of . She had a crew of 32 officers and 710 enlisted men.

''Patrie''s main battery consisted of four Canon de 305 mm Modèle 1893/96 guns mounted in two twin-gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechanis ...

s, one forward and one aft. The secondary battery

A rechargeable battery, storage battery, or secondary cell (formally a type of Accumulator (energy), energy accumulator), is a type of electrical battery which can be charged, discharged into a load, and recharged many times, as opposed to a ...

consisted of eighteen Canon de 164 mm Modèle 1893

Railroad model, 1916.

The Canon de 164 mm Modèle 1893 was a medium-caliber naval gun used as the secondary armament of a number of French pre-dreadnoughts and armoured cruisers during World War I. It was used as railway artillery in bo ...

guns; twelve were mounted in twin turrets, and six were in casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armoured structure from which guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to antiquity, the term "casemate wall" ...

s in the hull. She also carried twenty-four guns. The ship was also armed with two torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, which were submerged in the hull.

The ship's main belt

The asteroid belt is a torus-shaped region in the Solar System, centered on the Sun and roughly spanning the space between the orbits of the planets Jupiter and Mars. It contains a great many solid, irregularly shaped bodies called asteroids ...

was thick in the central citadel, and was connected to two armored decks; the upper deck was thick while the lower deck was thick, with sloped sides. The main battery guns were protected by up to of armor on the fronts of the turrets, while the secondary turrets had of armor on the faces. The conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armoured, from which an officer in charge can conn (nautical), conn (conduct or control) the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for t ...

had thick sides.

Modifications

Tests to determine whether the main battery turrets could be modified to increase the elevation of the guns (and hence their range) proved to be impossible, but the Navy determined that tanks on either side of the vessel could be flooded to induce aheel

The heel is the prominence at the posterior end of the foot. It is based on the projection of one bone, the calcaneus or heel bone, behind the articulation of the bones of the lower leg.

Structure

To distribute the compressive forces exerted ...

of 2 degrees. This increased the maximum range of the guns from . New motors were installed in the secondary turrets in 1915–1916 to improve their training and elevation rates. Also in 1915, the 47 mm guns located on either side of the bridge

A bridge is a structure built to Span (engineering), span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or railway) without blocking the path underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, whi ...

were removed and the two on the aft superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

were moved to the roof of the rear turret. On 8 December 1915, the naval command issued orders that the light battery was to be revised to just four of the 47 mm guns and eight guns. The light battery was revised again in 1916, with the four 47 mm guns being converted with high-angle anti-aircraft mounts. They were placed atop the rear main battery turret and the number 5 and 6 secondary turret roofs.

In 1912–1913, the ship received two Barr & Stroud

Barr & Stroud Limited was a pioneering Glasgow optical engineering firm. They played a leading role in developing modern optics, including rangefinders, for the Royal Navy and other branches of British Armed Forces during the 20th century. There ...

rangefinder

A rangefinder (also rangefinding telemeter, depending on the context) is a device used to Length measurement, measure distances to remote objects. Originally optical devices used in surveying, they soon found applications in other fields, suc ...

s, though ''Patrie'' later had these replaced with rangefinders taken from the dreadnought battleship

The dreadnought was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an effect when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her were referred to as "dreadnoughts", ...

. Tests revealed the wider rangefinders were more susceptible to working themselves out of alignment, so the navy decided to retain the 2 m version for the other battleships of the fleet. By 1916, the command determined to modernize the fleet's rangefinding equipment, and ''Patrie'' was fitted with one 2.74 m and two 2 m rangefinders for her primary and secondary guns, and one Barr & Stroud rangefinder for her anti-aircraft guns.

Service history

Construction – 1909

''Patrie'' waslaid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one ...

at the La Seyne shipyard on 1 April 1902, launched on 17 December 1903, and completed on 1 July 1907, several months after the revolutionary British battleship entered service, which rendered the pre-dreadnought

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built from the mid- to late- 1880s to the early 1900s. Their designs were conceived before the appearance of in 1906 and their classification as "pre-dreadnought" is retrospectively appl ...

s like ''Patrie'' outdated. While ''Patrie'' was still fitting-out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her o ...

, the nearby battleship suffered a catastrophic magazine explosion that destroyed the vessel. Her commanding officer attempted to flood the dock holding ''Iéna'' to put out the inferno by firing one of ''Patrie''s secondary guns at the dock gate, but the shell bounced off and did not penetrate it. The dock was finally flooded when Ensign de Vaisseau Jean-Antoine Roux (who was killed shortly afterward by fragments from the ship) managed to open the sluice gates. In May, the ship conducted sea trial

A sea trial or trial trip is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a "shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on op ...

s, and on 29 May, a condenser pipe in one of her boilers burst. Several stokers were scalded, and the ship had to return to Toulon

Toulon (, , ; , , ) is a city in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the French Riviera and the historical Provence, it is the prefecture of the Var (department), Var department.

The Commune of Toulon h ...

to have the condenser pipe replaced.

After entering service, she was assigned to the 1st Division of the Mediterranean Squadron, along with her sister and ''Suffren'', the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

of both the division and the squadron. The fleet thereafter embarked on its annual summer maneuvers, which lasted until 31 July. The Mediterranean Squadron joined the Northern Squadron for exercises in the western Mediterranean. On 5 November, ''Patrie'' replaced ''Suffren'' as the squadron flagship, hoisting the flag of ''Vice-amiral

Vice admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to lieutenant general and air marshal. A vice admiral is typically senior to a rear admiral and junior to an admiral.

Australia

In the Royal Australian Navy, the rank of vic ...

'' (''VA''—Vice Admiral) Germinet. On 13 January 1908, ''Patrie'' and the battleships ''République'', , , , , and steamed to Golfe-Juan

Golfe-Juan (; ) is a seaside resort on France's Côte d'Azur. The distinct local character of Golfe-Juan is indicated by the existence of a demonym, "Golfe-Juanais", which is applied to its inhabitants.

Overview

Golfe-Juan belongs to the commu ...

and then to Villefranche-sur-Mer

Villefranche-sur-Mer (, ; ; ) is a resort town in the Alpes-Maritimes department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region on the French Riviera and is located southwest of the Principality of Monaco, which is just west of the French-Italian ...

, where they remained for more than a month. During this period of training, on 17 March, ''Patrie'', ''République'', , and conducted shooting training, using the old ironclad

An ironclad was a steam engine, steam-propelled warship protected by iron armour, steel or iron armor constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or ince ...

as a target

Target may refer to:

Warfare and shooting

* Shooting target, used in marksmanship training and various shooting sports

** Bullseye (target), the goal one for which one aims in many of these sports

** Aiming point, in field artille ...

. In June and July, the Mediterranean and Northern Squadrons conducted their annual maneuvers, this time off Bizerte

Bizerte (, ) is the capital and largest city of Bizerte Governorate in northern Tunisia. It is the List of northernmost items, northernmost city in Africa, located north of the capital Tunis. It is also known as the last town to remain under Fr ...

. In October, the 1st Division ships, which by then consisted of ''Patrie'' and ''République'' steamed to Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

, Spain. The ships were inspected by King Alfonso XIII

Alfonso XIII ( Spanish: ''Alfonso León Fernando María Jaime Isidro Pascual Antonio de Borbón y Habsburgo-Lorena''; French: ''Alphonse Léon Ferdinand Marie Jacques Isidore Pascal Antoine de Bourbon''; 17 May 1886 – 28 February 1941), also ...

, who boarded ''Patrie'' during the visit.

By 5 January 1909, Germinet had been replaced by ''VA'' Fauque de Jonquières, following the publication of a letter in which Germinet criticized the fleet's ammunition supply. While in Villefranche, ''Patrie'' hosted Albert I, Prince of Monaco

Albert I (Albert Honoré Charles Grimaldi; 13 November 1848 – 26 June 1922) was Prince of Monaco from 10 September 1889 until his death in 1922. He devoted much of his life to oceanography, exploration and science. Alongside his expeditions, ...

during his visit to the port from 18 to 24 February. After his departure, the Mediterranean Squadron conducted training exercises off Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

, followed by a naval review

A Naval Review is an event where select vessels and assets of the United States Navy are paraded to be reviewed by the President of the United States or the Secretary of the Navy. Due to the geographic distance separating the modern U.S. Na ...

in Villefranche for President Armand Fallières

Clément Armand Fallières (; 6 November 1841 – 22 June 1931) was a French statesman who was President of France from 1906 to 1913.

Clément Armand Fallières was a symbol of republicanism in the French Third Republic. He was born into ...

on 26 April. ''Patrie'', ''Démocratie'', ''Liberté'', and the armored cruiser steamed into the Atlantic for training exercises on 2 June; while at sea ten days later, they rendezvoused with ''République'', ''Justice'', and the protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of cruiser of the late 19th century, took their name from the armored deck, which protected vital machine-spaces from fragments released by explosive shells. Protected cruisers notably lacked a belt of armour alon ...

at Cádiz

Cádiz ( , , ) is a city in Spain and the capital of the Province of Cádiz in the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia. It is located in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula off the Atlantic Ocean separated fr ...

, Spain. Training included serving as targets for the fleet's submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

s in the Pertuis d'Antioche

The Pertuis d'Antioche (, ''Passage of Antioch'') is a strait on the Atlantic coast of Western France between two islands; Île de Ré to the north, and Oléron to the south. To the east lies the continental coast between the cities of La Rochelle ...

strait. The ships then steamed north to La Pallice

La Pallice (also known as ''grand port maritime de La Rochelle'') is the commercial deep-water port of La Rochelle, France.

During the Fall of France, on 19 June 1940, approximately 6,000 Polish soldiers in exile under the command of Stanisła ...

, where they conducted tests with their wireless telegraphy

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is the transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using electrical cable, cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimenta ...

sets and shooting training in Quiberon Bay

Quiberon Bay (, ; ) is an area of sheltered water on the south coast of Brittany. The bay is in the Morbihan département.

Geography

The bay is roughly triangular in shape, open to the south with the Gulf of Morbihan to the north-east and the ...

. From 8 to 15 July, the ships lay at Brest and the next day, they steamed to Le Havre

Le Havre is a major port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy (administrative region), Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the Seine, river Seine on the English Channel, Channe ...

. There, they met the Northern Squadron for another fleet review for Fallières on 17 July. Ten days later, the combined fleet steamed to Cherbourg

Cherbourg is a former Communes of France, commune and Subprefectures in France, subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French departments of France, department of Manche. It was merged into the com ...

, where they held another fleet review, this time during the visit of Czar Nicholas II of Russia

Nicholas II (Nikolai Alexandrovich Romanov; 186817 July 1918) or Nikolai II was the last reigning Emperor of Russia, Congress Poland, King of Congress Poland, and Grand Duke of Finland from 1 November 1894 until Abdication of Nicholas II, hi ...

. ''Patrie'', ''République'', and ''Démocratie'' departed for Toulon on 17 August and arrived on 6 September.

1910–1914

''Patrie'' joined ''République'', ''Justice'', ''Vérité'', ''Démocratie'', and ''Suffren'' for a simulated attack on the port of

''Patrie'' joined ''République'', ''Justice'', ''Vérité'', ''Démocratie'', and ''Suffren'' for a simulated attack on the port of Nice

Nice ( ; ) is a city in and the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative city limits, with a population of nearly one milliontorpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

that accidentally hit ''République'', damaging her hull and forcing her to put into Toulon for repairs. She then steamed to Monaco

Monaco, officially the Principality of Monaco, is a Sovereign state, sovereign city-state and European microstates, microstate on the French Riviera a few kilometres west of the Regions of Italy, Italian region of Liguria, in Western Europe, ...

for the opening of the Oceanographic Museum of Monaco

The Oceanographic Museum (), is a museum of marine sciences in Monaco City, Monaco.

This building is part of the Institut océanographique, which is committed to sharing its knowledge of the oceans.

History

The Oceanographic Museum was i ...

in company with the destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

s and on 29 March. She then returned for maneuvers off Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

and Algeria from 21 May to 4 June in company with ''République'' and ''Démocratie''. Exercises with the rest of the Mediterranean Squadron followed from 7 to 18 June. An outbreak of typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by ''Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often ther ...

among the crews of the battleships in early December forced the navy to confine them to Golfe-Juan to contain the fever. By 15 December, the outbreak had subsided.

''VA'' Bellue replaced Fauque de Jonquières on 5 January 1911. On 16 April, ''Patrie'' and the rest of the fleet escorted ''Vérité'', which had aboard Fallières, the Naval Minister Théophile Delcassé

Théophile Delcassé (; 1 March 185222 February 1923) was a French politician who served as foreign minister from 1898 to 1905. He is best known for his hatred of German Empire, Germany and efforts to secure alliances with Russian Empire, Russ ...

, and Charles Dumont, the Minister of Public Works, Posts and Telegraphs, to Bizerte. They arrived two days later and held a fleet review that included two British battleships, two Italian battleships, and a Spanish cruiser on 19 April. The fleet returned to Toulon on 29 April, where Fallières doubled the crews' rations and suspended any punishments to thank the men for their performance. ''Patrie'' and the rest of 1st Squadron and the armored cruisers ''Ernest Renan'' and went on a cruise in the western Mediterranean in May and June, visiting a number of ports including Cagliari

Cagliari (, , ; ; ; Latin: ''Caralis'') is an Comune, Italian municipality and the capital and largest city of the island of Sardinia, an Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Italy. It has about 146,62 ...

, Bizerte, Bône

Annaba (), formerly known as Bon, Bona and Bône, is a seaport city in the northeastern corner of Algeria, close to the border with Tunisia. Annaba is near the small Seybouse River and is in the Annaba Province. With a population of about 263,65 ...

, Philippeville

Philippeville (; ) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Namur, Belgium. The Philippeville municipality includes the former municipalities of Fagnolle, Franchimont, Jamagne, Jamiolle, Merlemont, Neuville, Om ...

, Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

, and Bougie. By 1 August, the battleships of the had begun to enter service, and they were assigned to the 1st Squadron, displacing ''Patrie'', ''République'', and the ''Liberté''-class ships to the 2nd Squadron.

The fleet held another fleet review outside Toulon on 4 September. Admiral Jauréguiberry took the fleet to sea on 11 September for maneuvers and visits to Golfe-Juan and Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

, returning to port five days later. On 25 September, ''Liberté'' exploded while in Toulon, another French battleship claimed by unstable Poudre B

Poudre B was the first practical smokeless gunpowder created in 1884. It was perfected between 1882 and 1884 at "Laboratoire Central des Poudres et Salpêtres" in Paris, France. Originally called "Poudre V" from the name of the inventor, Paul V ...

propellant. Several ships in the harbor were damaged, though ''Patrie'' emerged unscathed. Despite the accident, the fleet continued with its normal routine of training exercises and cruises for the rest of the year. The 2nd Squadron conducted in maneuvers in April 1912, and on 25 April, ''Patrie'' and ''Vérité'' steamed to the Hyères

Hyères (), Provençal dialect, Provençal Occitan language, Occitan: ''Ieras'' in classical norm, or ''Iero'' in Mistralian norm) is a Communes of France, commune in the Var (département), Var Departments of France, department in the Provence-Al ...

roadstead

A roadstead or road is a sheltered body of water where ships can lie reasonably safely at anchor without dragging or snatching.United States Army technical manual, TM 5-360. Port Construction and Rehabilitation'. Washington: United States. Gove ...

for gunnery training. The two ships, joined by ''Justice'', left Toulon on 21 May for a set of exercises held between Marseille and Villefranche; while at sea, the battleship joined them, which had Admiral Augustin Boué de Lapeyrère

Augustin Manuel Hubert Gaston Boué de Lapeyrère (18 January 1852 – 17 February 1924) was a French admiral during World War I. He was a strong proponent of naval reform, and is comparable to Admiral Jackie Fisher of the British Royal Navy.

...

and the British Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales (, ; ) is a title traditionally given to the male heir apparent to the History of the English monarchy, English, and later, the British throne. The title originated with the Welsh rulers of Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd who, from ...

aboard. Boué de Lapeyrère inspected both battleship squadrons in Golfe-Juan from 2 to 12 July, after which the ships cruised first to Corsica and then to Algeria.

''VA'' de Marolles took command of the 2nd Squadron, hoisting his flag aboard ''Patrie'' on 6 January 1913. The ships then took part in training exercises off Le Lavandou

Le Lavandou (; ) is a seaside commune in the Var department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region in Southeastern France. Le Lavandou derives its name either from the flower lavender (''lavanda'' in Provençal) that is prevalent in the area ...

. The French fleet, which by then included sixteen battleships, held large-scale maneuvers between Toulon and Sardinia beginning on 19 May. The exercises concluded with a fleet review for President Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Nicolas Landry Poincaré (; 20 August 1860 – 15 October 1934) was a French statesman who served as President of France from 1913 to 1920, and three times as Prime Minister of France. He was a conservative leader, primarily committed to ...

. Gunnery practice followed from 1 to 4 July. The 2nd Squadron departed Toulon on 23 August with the armored cruisers and and two destroyer flotilla

A flotilla (from Spanish, meaning a small ''flota'' ( fleet) of ships), or naval flotilla, is a formation of small warships that may be part of a larger fleet.

Composition

A flotilla is usually composed of a homogeneous group of the same cla ...

s to conduct training exercises in the Atlantic. While en route to Brest, the ships stopped in Tangier

Tangier ( ; , , ) is a city in northwestern Morocco, on the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. The city is the capital city, capital of the Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima region, as well as the Tangier-Assilah Prefecture of Moroc ...

, Royan

Royan (; in the Saintongeais dialect; ) is a commune and town in the south-west of France, in the Departments of France, department of Charente-Maritime in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region. Capital of the Côte de Beauté, Royan is one of the mai ...

, Le Verdon, La Pallice, Quiberon Bay, and Cherbourg. They reached Brest on 20 September, where they met a Russian squadron of four battleships and five cruisers. The ships then steamed back south, stopping in Cádiz, Tangier, Mers El Kébir

Mers El Kébir ( ) is a port on the Mediterranean Sea, near Oran in Oran Province, northwest Algeria. It is famous for the attack on the French fleet in 1940, in the Second World War.

History

Originally a Phoenician port, it was called ''Port ...

, Algiers, and Bizerte before ultimately arriving back in Toulon on 1 November. The 2nd Squadron ships conducted torpedo training on 19 January 1914, and later that month they steamed to Bizerte, returning to Toulon on 6 February. The squadron visited various ports in June, but following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand was one of the key events that led to World War I. Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir presumptive to the Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg ...

and the ensuing July Crisis

The July Crisis was a series of interrelated diplomatic and military escalations among the Great power, major powers of Europe in mid-1914, Causes of World War I, which led to the outbreak of World War I. It began on 28 June 1914 when the Serbs ...

prompted the fleet to remain close to port, making only short training sorties as international tensions rose.

World War I

1914–1915

Following the outbreak of World War I in July 1914, France announced generalmobilization

Mobilization (alternatively spelled as mobilisation) is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the ...

on 1 August. The next day, Boué de Lapeyrère ordered the entire French fleet to begin raising steam at 22:15 so the ships could sortie early the next day. Faced with the prospect that the German Mediterranean Division

The Mediterranean Division () was a division consisting of the battlecruiser and the light cruiser of the German ''Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial Navy) in the early 1910s. It was established in response to the First Balkan War and saw action du ...

—centered on the battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of att ...

—might attack the troopship

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable to land troops directly on shore, typic ...

s carrying the French Army in North Africa to metropolitan France, the French fleet was tasked with providing heavy escort to the convoys. Accordingly, ''Patrie'' and the rest of the 2nd Squadron were sent to Algiers, where they joined a group of seven passenger ship

A passenger ship is a merchant ship whose primary function is to carry passengers on the sea. The category does not include cargo vessels which have accommodations for limited numbers of passengers, such as the ubiquitous twelve-passenger freig ...

s that had a contingent of 7,000 troops from XIX Corps aboard. While at sea, the new dreadnought battleship

The dreadnought was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an effect when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her were referred to as "dreadnoughts", ...

s and and the ''Danton''-class battleships and , which took over as the convoy's escort. Instead of attacking the convoys, ''Goeben'' bombarded Bône and Philippeville and then fled east to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

.

On 12 August, France and Britain declared war on the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military and diplomatic alliance, it consist ...

as the war continued to widen. The 1st and 2nd Squadrons were therefore sent to the southern Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

to contain the Austro-Hungarian Navy

The Austro-Hungarian Navy or Imperial and Royal War Navy (, in short ''k.u.k. Kriegsmarine'', ) was the navy, naval force of Austria-Hungary. Ships of the Austro-Hungarian Navy were designated ''SMS'', for ''Seiner Majestät Schiff'' (His Majes ...

. On 15 August, the two squadrons arrived off the Strait of Otranto

The Strait of Otranto (; ) connects the Adriatic Sea with the Ionian Sea and separates Italy from Albania. Its width between Punta Palascìa, eastern Salento, and Karaburun Peninsula, western Albania, is less than . The strait is named after ...

, where they met the patrolling British cruisers and north of Othonoi

Othonoi (, also rendered as Othoni, ) is a small inhabited list of Greek islands, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, located northwest of Corfu, and is the westernmost point of Greece. Othonoi is the largest and most populated of the Diapontian Isl ...

. Boué de Lapeyrère then took the fleet into the Adriatic in an attempt to force a battle with the Austro-Hungarian fleet; the following morning, the British and French cruisers spotted vessels in the distance that, on closing with them, turned out to be the protected cruiser and the torpedo boat , which were trying to blockade the coast of Montenegro. In the ensuing Battle of Antivari

The Battle of Antivari or Action off Antivari was a naval engagement between a large fleet of French and British warships and two ships of the Austro-Hungarian navy at the start of the First World War. The old Austrian protected cruiser and the ...

, Boué de Lapeyrère initially ordered his battleships to fire warning shots, but this caused confusion among the fleet's gunners that allowed ''Ulan'' to escape. The slower ''Zenta'' attempted to evade, but she quickly received several hits that disabled her engines and set her on fire. She sank shortly thereafter and the Anglo-French fleet withdrew.

The French fleet patrolled the southern end of the Adriatic for the next three days with the expectation that the Austro-Hungarians would counterattack, but their opponent never arrived. On 20 August, the 1st Squadron was sent to replenish fuel at Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

while ''Patrie'' and ''Vérité'' remained on station; ''Justice'', ''Démocratie'', and ''République'' had had to withdraw as well, the first two ships having collided and ''République'' having taken ''Démocratie'' under tow. The French battleships then bombarded Austrian fortifications at Cattaro

Kotor (Cyrillic: Котор, ), historically known as Cattaro (from Italian: ), is a town in Coastal region of Montenegro. It is located in a secluded part of the Bay of Kotor. The city has a population of 13,347 and is the administrative cen ...

on 1 September in an attempt to draw out the Austro-Hungarian fleet, which again refused to take the bait. By this time, ''République'' and ''Justice'' had returned. On 18–19 September, the fleet made another incursion into the Adriatic, steaming as far north as the island of Lissa; on the return south, several French cruisers inadvertently came within range of the guns at Cattaro, so ''Patrie'' and ''Démocratie'' opened fire at the guns to suppress them while the cruisers withdrew.

The patrols continued through December, when an Austro-Hungarian U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

torpedoed ''Jean Bart'', leading to the decision by the French naval command to withdraw the main battle fleet from direct operations in the Adriatic. During this period, the French made Corfu their primary naval base in the area, with Malta serving as a support base where maintenance could be effected. On 21 January 1915, ''Patrie'' went to Prováti to rescue the crew from a Greek steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

that had run aground there. On 18 May, ''VA'' Nicol came aboard ''Patrie'', making her his flagship; she then left 2nd Squadron for service with the Dardanelles Division as part of the Gallipoli Campaign. She steamed to the eastern Mediterranean with the armored cruiser and joined what became the 3rd Battle Division, which also included the battleships ''Suffren'', ''Saint Louis'', ''Charlemagne'', ''Jauréguiberry'', and . On 12 July, ''Patrie'' supported an assault on the Ottoman forts at Achi Baba Achi Baba () is a height dominating the Gallipoli Peninsula in Turkey, located in Çanakkale Province.''Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary'', p. 5 Achi Baba was the main position of the Ottoman Turkish defenses in 1915 during the World War I ...

, firing several salvos with her secondary battery before returning to Mudros

Moudros () is a town and a former municipality on the island of Lemnos, North Aegean, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Lemnos, of which it is a municipal unit. It covers the entire eastern peninsula o ...

for the night. On 2 August, she steamed south to shell Seferihisar

Seferihisar is a municipality and district of İzmir Province, Turkey. Its area is 375 km2, and its population is 60,914 (2024). Seferihisar district area borders on other İzmir districts of Urla to the west and Menderes to the east, and t ...

. During this action, a shell detonated in one of her secondary guns, wounding seven men.

1916–1918

Following the withdrawal from Gallipoli, the French transferred the ships of the erstwhile Dardanelles Division toSalonika

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

, Greece. There, on 5 May 1916, ''Patrie'' and ''Vérité'' shot down a German zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp. 155� ...

conducting reconnaissance in the area. By June, the French and British had grown weary over the refusal of the Greek King Constantine I

Constantine I (27 February 27222 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was a Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337 and the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. He played a Constantine the Great and Christianity, pivotal ro ...

to enter the war on the side of the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

, so the French formed the 3rd Squadron, comprising the five ''République''- and ''Liberté''-class battleships and sent them to Salonika to put pressure on the Greek government. Over the course of June and July, the ships alternated between Salonika and Mudros, and on 9 July, ''Patrie'' was detached for an overhaul at Toulon. While she was away, the bulk of the French fleet was transferred to Cephalonia

Kefalonia or Cephalonia (), formerly also known as Kefallinia or Kephallonia (), is the largest of the Ionian Islands in western Greece and the 6th-largest island in Greece after Crete, Euboea, Lesbos, Rhodes and Chios. It is also a separate regio ...

. Having arrived there after completing repairs by 1 September, the ship joined the 3rd Squadron on a patrol to Keratsini

Keratsini () is a suburban town in the western part of the Piraeus regional unit, which in turn is a part of the Athens Urban Area. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Keratsini-Drapetsona, of which it is the s ...

. From there, ''Patrie'', ''Démocratie'', and ''Suffren'' steamed to the roadstead

A roadstead or road is a sheltered body of water where ships can lie reasonably safely at anchor without dragging or snatching.United States Army technical manual, TM 5-360. Port Construction and Rehabilitation'. Washington: United States. Gove ...

off Eleusis

Elefsina () or Eleusis ( ; ) is a suburban city and Communities and Municipalities of Greece, municipality in Athens metropolitan area. It belongs to West Attica regional unit of Greece. It is located in the Thriasio Plain, at the northernmost ...

just outside Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

on 7 October. There, the ships were to take part in an attack on the Greek fleet, with ''Patrie'' slated to engage the battleship . But the plan was shelved and the French ultimately seized the Greek ships on 19 October.

In the meantime, in August, a pro-Allied group launched a coup against the monarchy in the ''Noemvriana

The ''Noemvriana'' (, "November Events") of , also called the Greek Vespers, was a political dispute, rooted in Greece's neutrality in World War I, that escalated into an armed confrontation in Athens between the Greek royalist government an ...

'', which the Allies sought to support. ''Patrie'' contributed men to a landing party that went ashore in Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

on 1 December support the coup. The British and French troops were defeated by the Greek Army and armed civilians and were forced to withdraw to their ships, after which the British and French fleet imposed a blockade of the royalist-controlled parts of the country. By June 1917, Constantine had been forced to abdicate and the 3rd Squadron was disbanded; ''Patrie'' and ''République'' became the Eastern Naval Division and were sent to the eastern Mediterranean. In December, both ships had their center and aft casemate guns removed. The ships spent 1917 largely idle as men were withdrawn from the fleet's battleships for use in anti-submarine warships. On 20 January 1918, the French received word that the battlecruiser ''Goeben'' (now under the Ottoman flag as ''Yavuz Sultan Selim'') would sortie, so ''Patrie'' and ''République'' prepared for action. The battlecruiser struck several naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive weapon placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Similar to anti-personnel mine, anti-personnel and other land mines, and unlike purpose launched naval depth charges, they are ...

s, however, and broke off the attack so the French ships remained in port.

On 4 July, ''Patrie'' went to Malta for periodic maintenance, which was completed four days later. She then returned to Mudros, by which time an influenza

Influenza, commonly known as the flu, is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These sympto ...

outbreak had killed eleven men and made another 475 seriously ill, 150 of whom had to be sent home to recover. ''Patrie'' was thereafter assigned to the Salonika Division, which was based in Mudros. The ship saw no further action for the remainder of the war, which concluded with the armistices signed with Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire in November.

Postwar career

Immediately after the end of the war, the French fleet began deploying to theBlack Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

as part of the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War

The Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War consisted of a series of multi-national military expeditions that began in 1918. The initial impetus behind the interventions was to secure munitions and supply depots from falling into the German ...

. ''Patrie'' was sent to Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

in the Ottoman Empire, itself wracked with internal collapse and the Greco-Turkish War. Due to personnel shortages, ''Patrie'' was reduced to a barracks ship

A barracks ship or barracks barge or berthing barge, or in civilian use accommodation vessel or accommodation ship, is a ship or a non-self-propelled barge containing a superstructure of a type suitable for use as a temporary barracks for sai ...

there. On 5 June 1919, she departed Constantinople and arrived in Toulon by way of Bizerte ten days later. She was assigned to the Training Division on 1 August as a replacement for the armored cruiser . She was transferred to the school for torpedomen and electricians on 19 February 1921. During a gunnery drill on 20 May 1924, a shell exploded in her starboard forward secondary turret, killing eight and wounding five men. Another accident occurred on 3 June when one of the training torpedoes malfunctioned and circled back, striking ''Patrie'' and punching a hole in the hull. She was decommissioned on 20 June and repairs lasted from 15 August to 15 September. ''Patrie'' then became a stationary training ship

A training ship is a ship used to train students as sailors. The term is mostly used to describe ships employed by navies to train future officers. Essentially there are two types: those used for training at sea and old hulks used to house class ...

at Saint-Mandrier-sur-Mer

Saint-Mandrier-sur-Mer (, "Saint-Mandrier on Sea"; ), commonly referred to simply as Saint-Mandrier (former official name), is a commune in the southeastern French department of Var, Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Across the harbour from t ...

, serving in that role until 1936. She was ultimately sold to ship breaker

Ship breaking (also known as ship recycling, ship demolition, ship scrapping, ship dismantling, or ship cracking) is a type of ship disposal involving the breaking up of ships either as a source of Interchangeable parts, parts, which can be sol ...

s on 25 September 1937 and scrap

Scrap consists of recyclable materials, usually metals, left over from product manufacturing and consumption, such as parts of vehicles, building supplies, and surplus materials. Unlike waste, scrap can have monetary value, especially recover ...

ped.

Footnotes

References

* * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Patrie (1903) République-class battleships Ships built in France 1906 ships Maritime incidents in 1907 Maritime incidents in 1910