French Battleship Bouvet on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Bouvet'' was a

In 1889, the

In 1889, the

''Bouvet'' was

''Bouvet'' was

''Bouvet''s main armament consisted of two Canon de 305 mm Modèle 1893 guns in two single-gun turrets, one each fore and aft and two Canon de 274 mm Modèle 1893 guns in two single-gun turrets, one amidships on each side,

''Bouvet''s main armament consisted of two Canon de 305 mm Modèle 1893 guns in two single-gun turrets, one each fore and aft and two Canon de 274 mm Modèle 1893 guns in two single-gun turrets, one amidships on each side,

''Bouvet'' was

''Bouvet'' was  Beginning in January 1909, with the commissioning of the six and s, the Mediterranean Squadron was reorganized into two battle squadrons; ''Bouvet'' was at that time assigned to the 3rd Division, part of the 2nd Battle Squadron, still the flagship of Marin-Darbel. Her place was taken the following year by ''Saint Louis'', and she remained out of service that year, with the exception of during the fleet maneuvers conducted in June, which she joined. In January 1911, she returned to service as the flagship of Adam in the 2nd Division of the 2nd Battle Squadron. On 5 October, the fleet was again reorganized and her place in what was now the 3rd Battle Squadron was taken by ''Charles Martel''. On 16 October 1912, ''Bouvet'', ''Gaulois'', ''Saint Louis'', ''Carnot'', ''Masséna'', and ''Jauréguiberry'' were activated for training duties as the 3rd Squadron of the Mediterranean Squadron; in July 1913, they were joined by ''Charlemagne''. The squadron was dissolved on 11 November, and ''Bouvet'', ''Saint Louis'', and ''Gaulois'' were assigned to the (). Training activities continued into 1914, and in March, the division joined the rest of the Mediterranean Squadron, which was now re-designated as the () for gunnery training off Corsica. Additional maneuvers were conducted beginning on 13 May, during which the fleet visited

Beginning in January 1909, with the commissioning of the six and s, the Mediterranean Squadron was reorganized into two battle squadrons; ''Bouvet'' was at that time assigned to the 3rd Division, part of the 2nd Battle Squadron, still the flagship of Marin-Darbel. Her place was taken the following year by ''Saint Louis'', and she remained out of service that year, with the exception of during the fleet maneuvers conducted in June, which she joined. In January 1911, she returned to service as the flagship of Adam in the 2nd Division of the 2nd Battle Squadron. On 5 October, the fleet was again reorganized and her place in what was now the 3rd Battle Squadron was taken by ''Charles Martel''. On 16 October 1912, ''Bouvet'', ''Gaulois'', ''Saint Louis'', ''Carnot'', ''Masséna'', and ''Jauréguiberry'' were activated for training duties as the 3rd Squadron of the Mediterranean Squadron; in July 1913, they were joined by ''Charlemagne''. The squadron was dissolved on 11 November, and ''Bouvet'', ''Saint Louis'', and ''Gaulois'' were assigned to the (). Training activities continued into 1914, and in March, the division joined the rest of the Mediterranean Squadron, which was now re-designated as the () for gunnery training off Corsica. Additional maneuvers were conducted beginning on 13 May, during which the fleet visited

pre-dreadnought battleship

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built from the mid- to late- 1880s to the early 1900s. Their designs were conceived before the appearance of in 1906 and their classification as "pre-dreadnought" is retrospectively appli ...

of the French Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the Navy, maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of History of France, France. It is among the largest and most powerful List of navies, naval forces i ...

that was built in the 1890s. She was a member of a group of five broadly similar battleships, along with , , , and , which were ordered in response to the British . ''Bouvet'' was the last vessel of the group to be built, and her design was based on that of ''Charles Martel''. Like her half-sisters, she was armed with a main battery of two guns and two guns in individual turrets. She had a top speed of , which made her one of the fastest battleships in the world at the time. ''Bouvet'' proved to be the most successful design of the five, and she was used as the basis for the subsequent . Nevertheless, she suffered from design flaws that reduced her stability and contributed to her loss in 1915.

''Bouvet'' spent the majority of her peacetime career in the Mediterranean Squadron conducting routine training exercises. This period was relatively uneventful, though she was involved in a collision with the battleship in 1903 that saw both ships' captains relieved of command. In 1906, she assisted in the response to the eruption of Mount Vesuvius

Mount Vesuvius ( ) is a Somma volcano, somma–stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples in Campania, Italy, about east of Naples and a short distance from the shore. It is one of several volcanoes forming the Campanian volcanic arc. Vesuv ...

in Italy. ''Bouvet'' was withdrawn from front-line service in 1907 and thereafter used as part of the training fleet. The ship was the only vessel of her group of five half-sisters still in service at the outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in July 1914.

A significant portion of the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (, , ), is the principal Army, land warfare force of France, and the largest component of the French Armed Forces; it is responsible to the Government of France, alongside the French Navy, Fren ...

was stationed in French North Africa

French North Africa (, sometimes abbreviated to ANF) is a term often applied to the three territories that were controlled by France in the North African Maghreb during the colonial era, namely Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. In contrast to French ...

, so at the start of the war, ''Bouvet'' and much of the rest of the fleet were used to escort troop convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

s across to southern France. With this work done by late August, ''Bouvet'' and several other battleships were used to patrol for contraband

Contraband (from Medieval French ''contrebande'' "smuggling") is any item that, relating to its nature, is illegal to be possessed or sold. It comprises goods that by their nature are considered too dangerous or offensive in the eyes of the leg ...

shipments in the central Mediterranean. From November to late December, she was stationed as a guard ship

A guard ship is a warship assigned as a stationary guard in a port or harbour, as opposed to a coastal patrol boat, which serves its protective role at sea.

Royal Navy

In the Royal Navy of the eighteenth century, peacetime guard ships were usual ...

at the northern entrance to the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

. The ship thereafter joined the naval operations off the Dardanelles, where she participated in a series of attacks on the Ottoman fortifications guarding the straits. These culminated in a major assault on 18 March 1915; during the attack, she was hit approximately eight times by shellfire but was not seriously damaged. While turning to withdraw, however, she struck a mine

Mine, mines, miners or mining may refer to:

Extraction or digging

*Miner, a person engaged in mining or digging

*Mining, extraction of mineral resources from the ground through a mine

Grammar

*Mine, a first-person English possessive pronoun

M ...

and sank within two minutes; only 75 men were rescued from a complement of 718. Two British battleships were also sunk by mines that day, and the disaster convinced the Allies to abandon the naval campaign in favor of an amphibious assault on the Gallipoli Peninsula.

Design

In 1889, the

In 1889, the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of ...

passed the Naval Defence Act that resulted in the construction of the eight s; this major expansion of naval power led the French government to pass its reply, the (Naval Law) of 1890. The law called for a total of twenty-four "" (squadron battleships) and a host of other vessels, including coastal defense battleships, cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several operational roles from search-and-destroy to ocean escort to sea ...

s, and torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s. The first stage of the program was to be a group of four squadron battleships that were built to different designs but met the same basic characteristics, including armor, armament, and displacement. The naval high command issued the basic requirements on 24 December 1889; displacement

Displacement may refer to:

Physical sciences

Mathematics and physics

*Displacement (geometry), is the difference between the final and initial position of a point trajectory (for instance, the center of mass of a moving object). The actual path ...

would not exceed , the primary armament was to consist of and guns, the belt armor

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from penetrating to ...

should be thick, and the ships should maintain a top speed of . The secondary battery

A rechargeable battery, storage battery, or secondary cell (formally a type of Accumulator (energy), energy accumulator), is a type of electrical battery which can be charged, discharged into a load, and recharged many times, as opposed to a ...

was to be either or caliber, with as many guns fitted as space would allow. The general similarity of the ships led some observers to group them together as a ship class

A ship class is a group of ships of a similar design. This is distinct from a ship type, which might reflect a similarity of tonnage or intended use. For example, is a nuclear aircraft carrier (ship type) of the (ship class).

In the course o ...

, though the authors of ''Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships'' point out that the vessels had "sufficient differences to prevent them from being considered as one class."

The basic design for the ships was based on the previous battleship , but instead of mounting the main battery all on the centerline, the ships used the lozenge arrangement of the earlier vessel , which moved two of the main battery guns to single turrets

Turret may refer to:

* Turret (architecture), a small tower that projects above the wall of a building

* Gun turret, a mechanism of a projectile-firing weapon

* Objective turret, an indexable holder of multiple lenses in an optical microscope

* ...

on the wings

A wing is a type of fin that produces both lift and drag while moving through air. Wings are defined by two shape characteristics, an airfoil section and a planform. Wing efficiency is expressed as lift-to-drag ratio, which compares the bene ...

. Although the navy had stipulated that displacement could be up to 14,000 t, political considerations, namely parliamentary objections to increases in naval expenditures, led the designers to limit displacement to around . Five naval architects submitted proposals to the competition; Charles Ernest Huin prepared the design for ''Bouvet''. He had also designed her half-sister , upon which the design for ''Bouvet'' was based. Before work on ''Charles Martel'' had begun, the naval command asked Huin to design an improved version. He completed the plans for the ship, which was slightly larger than her half-sisters, on 20 May, and the Navy awarded the contract for the ship on 8 October 1892.

''Bouvet'' proved to be the most successful of the five ships, and she was the only one still in active service at the outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. She also provided the basis for the next class of French battleships, the three s built in the mid-1890s. She and her half-sisters nevertheless were disappointments in service; ''Bouvet'' suffered from stability problems that ultimately contributed to her loss in 1915, and all five of the vessels compared poorly to their British counterparts, particularly their contemporaries of the . The ships suffered from a lack of uniformity of equipment, which made them hard to maintain in service, and their mixed gun batteries comprising several calibers made gunnery in combat conditions difficult, since shell splashes were hard to differentiate. Many of the problems that plagued the ships in service were a result of the limitation on their displacement, particularly their stability and seakeeping

Seakeeping ability or seaworthiness is a measure of how well-suited a watercraft is to conditions when underway. A ship or boat which has good seakeeping ability is said to be very seaworthy and is able to operate effectively even in high sea stat ...

.

General characteristics and machinery

''Bouvet'' was

''Bouvet'' was long between perpendiculars

Length between perpendiculars (often abbreviated as p/p, p.p., pp, LPP, LBP or Length BPP) is the length of a ship along the summer load line from the forward surface of the stem, or main bow perpendicular member, to the after surface of the stern ...

, long at the waterline

A vessel's length at the waterline (abbreviated to L.W.L) is the length of a ship or boat at the level where it sits in the water (the ''waterline''). The LWL will be shorter than the length of the boat overall (''length overall'' or LOA) as mos ...

, and long overall

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, and is also u ...

. She had a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Radio beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially lo ...

of and an average draft

Draft, the draft, or draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a v ...

of . She had a displacement of as designed. Unlike her half-sisters, which had a cut down quarterdeck

The quarterdeck is a raised deck behind the main mast of a sailing ship. Traditionally it was where the captain commanded his vessel and where the ship's colours were kept. This led to its use as the main ceremonial and reception area on bo ...

, ''Bouvet'' retained a full flush deck

In naval architecture, a flush deck is a Deck (ship), ship deck that is continuous from stem to stern.

History

Flush decks have been in use since the times of the ancient Egyptians. Greco-Roman Trireme often had a flush deck but may have also ha ...

. Her superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

was reduced in size compared to her half-sisters, and she had a pair of short military masts; these changes were made to reduce the top-heaviness experienced with the earlier vessels. She kept the pronounced tumblehome

Tumblehome or tumble home is the narrowing of a Hull (watercraft), hull above the waterline, giving less beam (nautical), beam at the level of the main deck. The opposite of tumblehome is flare (ship), flare.

A small amount of tumblehome is nor ...

to give the 27 cm guns wide fields of fire. ''Bouvet'' had a standard crew of 31 officers and 591 enlisted men, though as a flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

her crew grew to 41 officers and 651 enlisted men.

She had three vertical triple-expansion steam engine

A compound steam engine unit is a type of steam engine where steam is expanded in two or more stages.

A typical arrangement for a compound engine is that the steam is first expanded in a high-pressure (HP) Cylinder (engine), cylinder, then ha ...

s each driving a single three-bladed screw

A screw is an externally helical threaded fastener capable of being tightened or released by a twisting force (torque) to the screw head, head. The most common uses of screws are to hold objects together and there are many forms for a variety ...

; the outboard screws were wide, while the center shaft was slightly smaller, at in diameter. The engines were powered with steam supplied by thirty-two Belleville water-tube boiler

A high pressure watertube boiler (also spelled water-tube and water tube) is a type of boiler in which water circulates in tubes heated externally by fire. Fuel is burned inside the furnace, creating hot gas which boils water in the steam-generat ...

s that were license-built by Indret. The boilers were divided into four boiler rooms, which were placed in two pairs on either end of the magazines for the wing turrets, and divided by a central bulkhead. The boilers were ducted into a pair of funnels

A funnel is a tube or pipe that is wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, used for guiding liquid or powder into a small opening.

Funnels are usually made of stainless steel, aluminium, glass, or plastic. The material used in its constructi ...

. Her three engines were placed side by side and also divided by longitudinal bulkheads.

Her propulsion system was rated at , which allowed the ship to steam at a maximum speed of on speed trials with a light loading, though while on a 24-hour test using normal displacement, she cruised at . Using forced draft

In a water boiler, draft is the difference between atmospheric pressure and the pressure existing in the furnace or flue gas passage. Draft can also be referred to as the difference in pressure in the combustion chamber area which results in the mo ...

, she reached from during the tests. ''Bouvet'' was fast by the standards of the day; the only British battleship that approached her in speed was the second-class battleship . As built, ''Bouvet'' could carry of coal, though additional space allowed for up to in total. At a cruising speed of , the ship could steam for .

The ship's electrical system consisted of four 400-ampere

The ampere ( , ; symbol: A), often shortened to amp,SI supports only the use of symbols and deprecates the use of abbreviations for units. is the unit of electric current in the International System of Units (SI). One ampere is equal to 1 c ...

/80-volt

The volt (symbol: V) is the unit of electric potential, Voltage#Galvani potential vs. electrochemical potential, electric potential difference (voltage), and electromotive force in the International System of Units, International System of Uni ...

dynamo

"Dynamo Electric Machine" (end view, partly section, )

A dynamo is an electrical generator that creates direct current using a commutator. Dynamos employed electromagnets for self-starting by using residual magnetic field left in the iron cores ...

s that had a combined output of . The dynamos were placed on the platform deck between the ducting for the boilers. Several smaller electric motors, rated at , powered the ship's ventilation system, and motors drove the ash hoists for the boiler rooms. ''Bouvet'' was fitted with six searchlight

A searchlight (or spotlight) is an apparatus that combines an extremely luminosity, bright source (traditionally a carbon arc lamp) with a mirrored parabolic reflector to project a powerful beam of light of approximately parallel rays in a part ...

s: four on the battery deck (two amidships and one each forward and aft) and the remaining two on the masts.

Armament

''Bouvet''s main armament consisted of two Canon de 305 mm Modèle 1893 guns in two single-gun turrets, one each fore and aft and two Canon de 274 mm Modèle 1893 guns in two single-gun turrets, one amidships on each side,

''Bouvet''s main armament consisted of two Canon de 305 mm Modèle 1893 guns in two single-gun turrets, one each fore and aft and two Canon de 274 mm Modèle 1893 guns in two single-gun turrets, one amidships on each side, sponson

Sponsons are projections extending from the sides of land vehicles, aircraft or watercraft to provide protection, Instantaneous stability, stability, storage locations, mounting points for weapons or other devices, or equipment housing.

Watercra ...

ed out over the tumblehome of the ship's sides. Both types of guns were experimental 45 caliber

In guns, particularly firearms, but not #As a measurement of length, artillery, where a different definition may apply, caliber (or calibre; sometimes abbreviated as "cal") is the specified nominal internal diameter of the gun barrel Gauge ( ...

variants of the guns fitted in her half-sister . The 305 mm guns had a muzzle velocity

Muzzle velocity is the speed of a projectile (bullet, pellet, slug, ball/ shots or shell) with respect to the muzzle at the moment it leaves the end of a gun's barrel (i.e. the muzzle). Firearm muzzle velocities range from approximately t ...

of , which allowed the shells to penetrate up to of iron armor at a range of . This was sufficiently powerful to allow ''Bouvet''s main guns to easily penetrate the armor of most contemporary battleships at the common battle ranges of the day. The 274 mm guns, which were also 45 calibers long, had the same muzzle velocity, but being significantly smaller than the 305 mm guns, produced of iron penetration. The gun turrets were hydraulically operated and required the guns to be depressed to −4° to be loaded. They both had a rate of fire

Rate of fire is the frequency at which a specific weapon can fire or launch its projectiles. This can be influenced by several factors, including operator training level, mechanical limitations, ammunition availability, and weapon condition. In m ...

of one shell per minute. Both types of mounts allowed elevation to 14°; for the 305 mm guns, this produced a maximum range of , and for the 274 mm guns, their maximum range was .

Her secondary armament consisted of eight Canon de 138 mm Modèle 1891 naval guns, which were mounted in single turrets in the hull; two were placed just aft of the forward 305 mm turret, four were placed on either sides of the 274 mm guns, and the remaining two were just aft of the rear 305 mm turret. These guns had a firing rate of 4 rounds per minute, with a maximum range of from up to 20° elevation. For defense against torpedo boats, ''Bouvet'' carried eight quick-firing (QF) guns in individual pedestal mounts with gun shield

A U.S. Marine manning an M240 machine gun equipped with a gun shield

A gun shield is a flat (or sometimes curved) piece of armor designed to be mounted on a crew-served weapon such as a machine gun, automatic grenade launcher, or artillery pie ...

s on the upper deck. Four were located between the funnels, two were placed abreast of the forward bridge, and the remaining two were similarly arranged on either side of the aft bridge. They had a rate of fire of between 7 and 15 shots per minute and they could engage targets out to . She also had twelve 3-pounder guns, and eight 1-pounder guns, all in individual mounts. Of the 37 mm guns, three were five-barreled Hotchkiss revolver cannon

The Hotchkiss gun can refer to different types of the Hotchkiss arms company starting in the late 19th century. It usually refers to the 1.65-inch (42 mm) light mountain gun. There were also navy (47 mm) and 3-inch (76 mm) ...

and the remaining five were single-barrel QF guns. Four of the 47 mm guns were mounted on the lower platforms of the military masts and the remainder, along with the 37 mm guns, were distributed along the length of the superstructure.

As was customary for capital ships of the period, her armament suite was rounded out by four torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, two of which were submerged in the ship's hull; both were located on the broadside close to the bow; they were aimed directly perpendicular to the centerline. The other two tubes were mounted above water, in trainable launchers placed amidships. The fire of these tubes was directed either by armored sights located abreast of the conning tower or unprotected sights on the battery deck. ''Bouvet'' carried a total of ten torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

es of the Modèle 1892 Toulon/Fiume type; six were allocated to the submerged tubes, with the other four for the deck launchers. ''Bouvet'' also carried twenty Modèle 1892 naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive weapon placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Similar to anti-personnel mine, anti-personnel and other land mines, and unlike purpose launched naval depth charges, they are ...

s that could be laid by the ship's pinnaces

Pinnace may refer to:

* Pinnace (ship's boat), a small vessel used as a tender to larger vessels among other things

* Full-rigged pinnace

The full-rigged pinnace was the larger of two types of vessel called a pinnace in use from the sixteenth ...

.

Fire control

In the early 1890s, before ''Bouvet'' had begun construction, the French Navy introduced afire-control system

A fire-control system (FCS) is a number of components working together, usually a gun data computer, a director and radar, which is designed to assist a ranged weapon system to target, track, and hit a target. It performs the same task as a hum ...

that included rangefinder

A rangefinder (also rangefinding telemeter, depending on the context) is a device used to Length measurement, measure distances to remote objects. Originally optical devices used in surveying, they soon found applications in other fields, suc ...

s, observers in the masts, and electric order transmitters to communicate fire control instructions from the control center to the gun crews. ''Bouvet'' was the first battleship completed with the system; for the purposes of fire control, her gun battery was divided into either individual sections (the large and medium-caliber guns) or groups of two or more guns (the 100 mm, 47 mm, and 37 mm guns). All of the guns were controlled by the () that was located directly below the conning tower, below the armored deck. The central command post received the range and bearing information from the rangefinders and calculated firing solutions, which would then be sent via the electric order transmitters to direct the fire of individual guns or sections.

Armor

The ship's armor was constructed with nickel steel manufactured by several firms, includingSchneider-Creusot

Schneider et Compagnie, also known as Schneider-Creusot for its birthplace in the French town of Le Creusot, was a historic iron and steel-mill company which became a major arms manufacturer. In the 1960s, it was taken over by the Belgian Empain ...

, Saint-Chamond St Chamond may refer to:

* Saint Chamond otherwise Annemund, bishop of Lyon

* Saint-Chamond, Loire, a French town named after him

* Saint-Chamond (manufacturer), informal name for the ''Compagnie des forges et aciéries de la marine et d'Homéco ...

, and Châtillon & Commentry, which allowed the design staff to reduce the thickness of the steel without compromising its effectiveness. Thus, weight could be saved that could be used elsewhere in the displacement-limited ships. The main belt was thick amidships, and tapered down to at the lower edge. Forward of the central citadel, the belt was reduced to (also reduced to 200 mm on the lower edge) and aft of the citadel, it tapered to (reduced to on the bottom edge). The belt extended for the entire length of the hull, and it was backed with 200 mm of teak

Teak (''Tectona grandis'') is a tropical hardwood tree species in the family Lamiaceae. It is a large, deciduous tree that occurs in mixed hardwood forests. ''Tectona grandis'' has small, fragrant white flowers arranged in dense clusters (panic ...

. Above the belt was thick strake

On a vessel's Hull (watercraft), hull, a strake is a longitudinal course of Plank (wood), planking or Plate (metal), plating which runs from the boat's stem (ship), stempost (at the Bow (ship), bows) to the stern, sternpost or transom (nautica ...

of side armor that created a highly subdivided cofferdam

A cofferdam is an enclosure built within a body of water to allow the enclosed area to be pumped out or drained. This pumping creates a dry working environment so that the work can be carried out safely. Cofferdams are commonly used for constru ...

to reduce the risk of flooding from battle damage. The side of the cofferdam was reinforced by two layers of plating. ''Bouvet''s main deck was protected with of mild steel

Carbon steel is a steel with carbon content from about 0.05 up to 2.1 percent by weight. The definition of carbon steel from the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) states:

* no minimum content is specified or required for chromium, cobalt ...

, back with two layers of 10 mm plating. Mild steel was used here, as the deck was designed to bend rather than shatter when struck by an armor-piercing shell at an oblique angle. The lower platform deck was thick, with a single layer of 10 mm plating behind it; it was intended to catch splinters that penetrated the main deck.

The main battery guns (both the 305 mm and 274 mm guns) were protected with of cemented armor on the faces and sides, with thick roofs and thick floors. Both the floors and roofs were composed of mild steel. The turrets sat atop barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protection ...

s with thick sides. The 138 mm turrets had thick sides and faces, with roofs and floors. Gun shields that were thick protected the 100 mm guns. The conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armoured, from which an officer in charge can conn (nautical), conn (conduct or control) the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for t ...

had thick sides, a 20 mm thick roof, and a thick floor. The uptakes for the boilers were protected with coaming

Coaming is any vertical surface on a ship designed to deflect or prevent entry of water. It usually consists of a raised section of deck plating around an opening, such as a cargo hatch. Coamings also provide a frame onto which to fit a hatch cov ...

s that were 300 mm thick.

The ship's armor layout was not as effective as the designers had hoped; at the designed displacement, the belt armor was submerged with just a 3° heel

The heel is the prominence at the posterior end of the foot. It is based on the projection of one bone, the calcaneus or heel bone, behind the articulation of the bones of the lower leg.

Structure

To distribute the compressive forces exerted ...

, and training all of the main battery turrets to one side would produce a heel of 2°. Incremental increases in weight during the construction process, which Huin was unable to supervise, left little margin for the belt to remain above the water. These increases forced compromises elsewhere in the ship's armor protection, most notably the barbettes, which were criticized at the time; nothing could be done, however, due to the strict limit placed on displacement. The cofferdam also proved to be highly susceptible to uncontrollable flooding, which would have serious effects on the vessel's stability.

Service history

''Bouvet'' was

''Bouvet'' was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one ...

at the French Navy shipyard in Lorient

Lorient (; ) is a town (''Communes of France, commune'') and Port, seaport in the Morbihan Departments of France, department of Brittany (administrative region), Brittany in western France.

History

Prehistory and classical antiquity

Beginn ...

on 16 January 1893, and was launched on 27 April 1896. After completing fitting-out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her o ...

work, she began sea trials

A sea trial or trial trip is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on o ...

on 5 March 1898. The ship was intended to have conducted her trials from Brest, but she was sent to Toulon

Toulon (, , ; , , ) is a city in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the French Riviera and the historical Provence, it is the prefecture of the Var (department), Var department.

The Commune of Toulon h ...

to reinforce the Mediterranean Squadron due to the Fashoda crisis

The Fashoda Incident, also known as the Fashoda Crisis ( French: ''Crise de Fachoda''), was the climax of imperialist territorial disputes between Britain and France in East Africa, occurring between 10 July to 3 November 1898. A French expedit ...

with Britain. She was commissioned into the French Navy in June 1898. The ship was named in honor of Admiral François Joseph Bouvet

François Joseph Bouvet (; 1753–1832) was a French admiral.

Early life

Son of René Joseph Bouvet de Précourt, a captain in the service of the French East India Company and of the French Royal Navy under Suffren, François Joseph Bouvet we ...

.

Throughout the ship's peacetime career, she was occupied with routine training exercises that included gunnery training, combined maneuvers with torpedo boats and submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

s, and practicing attacking coastal fortifications

A coast (coastline, shoreline, seashore) is the land next to the sea or the line that forms the boundary between the land and the ocean or a lake. Coasts are influenced by the topography of the surrounding landscape and by aquatic erosion, su ...

. Since ''Bouvet'' was one of the most modern French battleships in the late 1890s and early 1900s, she spent this time in the Mediterranean Squadron, France's primary fleet. One of the largest of these exercises was conducted between March and July 1900, and involved the Mediterranean Squadron and the Northern Squadron. On 6 March, ''Bouvet'' joined the battleships ''Brennus'', , , ''Charles Martel'', and and four protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of cruiser of the late 19th century, took their name from the armored deck, which protected vital machine-spaces from fragments released by explosive shells. Protected cruisers notably lacked a belt of armour alon ...

s for maneuvers off Golfe-Juan

Golfe-Juan (; ) is a seaside resort on France's Côte d'Azur. The distinct local character of Golfe-Juan is indicated by the existence of a demonym, "Golfe-Juanais", which is applied to its inhabitants.

Overview

Golfe-Juan belongs to the commu ...

on the Côte d'Azur

The French Riviera, known in French as the (; , ; ), is the Mediterranean coastline of the southeast corner of France. There is no official boundary, but it is considered to be the coastal area of the Alpes-Maritimes department, extending fr ...

, including night firing training. Over the course of April, the ships visited numerous French ports along the Mediterranean coast, and on 31 May the fleet steamed to Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

for a visit that lasted until 8 June. After completing its own exercises in the Mediterranean, the Mediterranean Squadron rendezvoused with the Northern Squadron off Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

, Portugal, in late June before proceeding to Quiberon Bay

Quiberon Bay (, ; ) is an area of sheltered water on the south coast of Brittany. The bay is in the Morbihan département.

Geography

The bay is roughly triangular in shape, open to the south with the Gulf of Morbihan to the north-east and the ...

for joint maneuvers in July. The maneuvers concluded with a naval review

A Naval Review is an event where select vessels and assets of the United States Navy are paraded to be reviewed by the President of the United States or the Secretary of the Navy. Due to the geographic distance separating the modern U.S. Na ...

in Cherbourg

Cherbourg is a former Communes of France, commune and Subprefectures in France, subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French departments of France, department of Manche. It was merged into the com ...

on 19 July for President Émile Loubet

Émile François Loubet (; 30 December 183820 December 1929) was the 45th Prime Minister of France from February to December 1892 and later President of France from 1899 to 1906.

Trained in law, he became Mayor (France), mayor of Montélimar, w ...

. On 1 August, the Mediterranean Fleet departed for Toulon, arriving on 14 August.

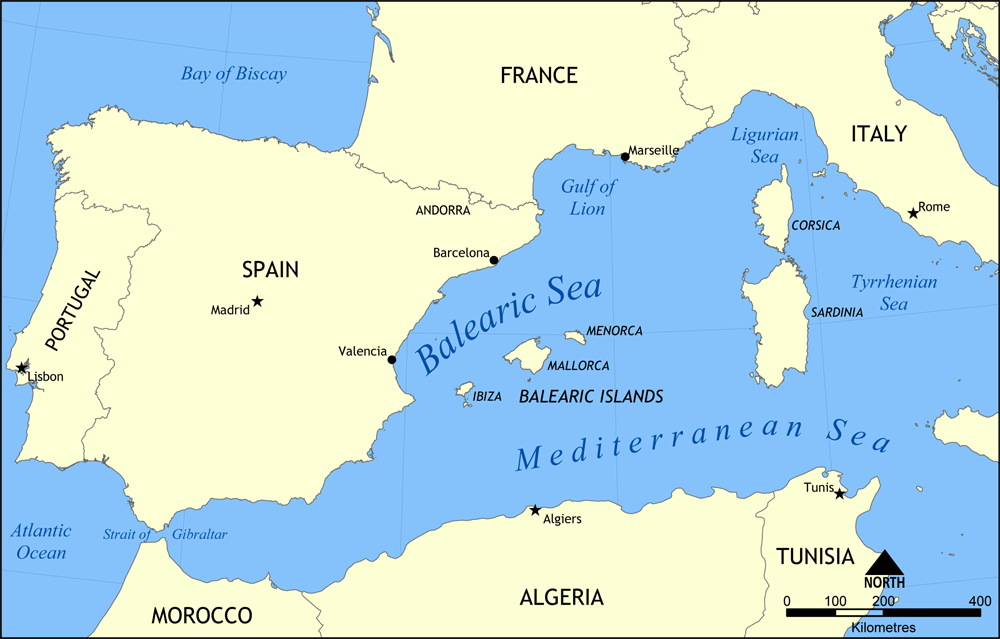

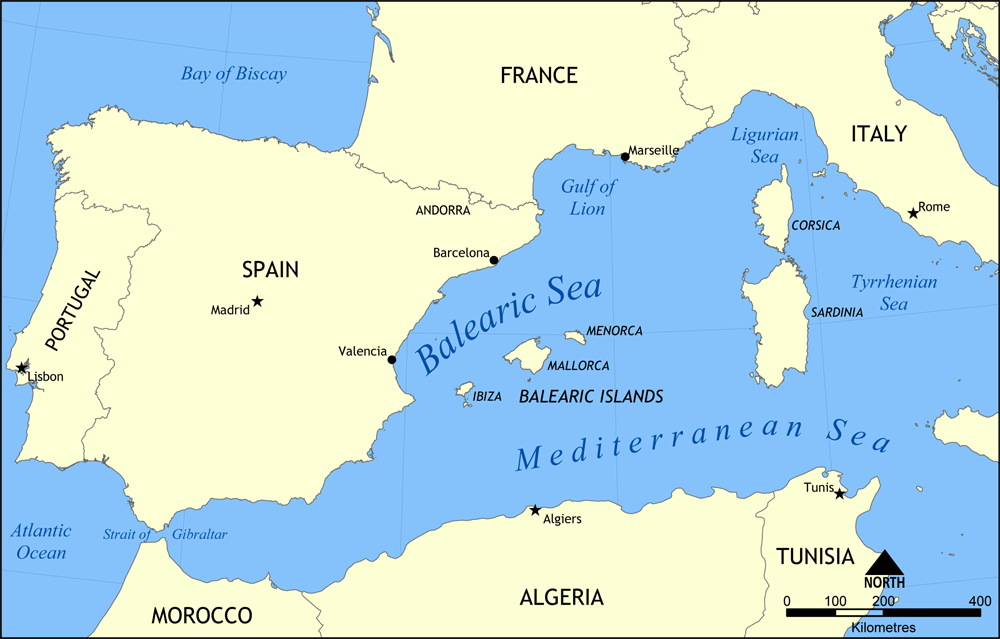

''Bouvet'' was assigned to the 2nd Battle Division of the Mediterranean Squadron, along with ''Jauréguiberry'' and the new battleship , the latter becoming the divisional flagship. ''Bouvet'' departed Toulon on 29 January 1903 in company with the battleships , ''Gaulois'', and ''Charlemagne'', four cruisers, and accompanying destroyers for gunnery training off Golfe-Juan. At the time, ''Bouvet'' and ''Gaulois'' were the 2nd Division, with ''Bouvet'' in the lead; the other two ships formed the 1st Division. Two days later, when the divisions were ordered to change from two columns to a single line ahead for shooting drills, ''Bouvet'' failed to take her prescribed position and instead turned too closely to ''Gaulois''. The latter accidentally struck the former, with ''Bouvet'' losing a ladder and incurring damage to one of the deck-mounted torpedo tubes. ''Gaulois'' had two armor plates torn from her bow. Both ships' captains were relieved of command over the incident. In October, ''Bouvet'' and the rest of the Mediterranean Squadron battleships steamed to Palma de Mallorca, and on their return to Toulon they conducted training exercises.

The year 1904 saw the Mediterranean Squadron visit Souda Bay

Souda Bay () is a bay and natural harbour near the town of Souda on the northwest coast of the Greek island of Crete. The bay is about 15 km long and only two to four km wide, and a deep natural harbour. It is formed between the Akroti ...

in Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

, Beirut

Beirut ( ; ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, just under half of Lebanon's population, which makes it the List of largest cities in the Levant region by populatio ...

, Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

, and Salonika

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, Messina

Messina ( , ; ; ; ) is a harbour city and the capital city, capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of 216,918 inhabitants ...

in Sicily, and Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; ; , Ancient: , Katharevousa: ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens city centre along the east coast of the Saronic Gulf in the Ath ...

, Greece, during a cruise of the eastern Mediterranean in the middle of the year. The following year passed uneventfully for ''Bouvet'', and on 10 April 1906, she, ''Iéna'', and ''Gaulois'' were sent to Italy in the aftermath of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius

Mount Vesuvius ( ) is a Somma volcano, somma–stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples in Campania, Italy, about east of Naples and a short distance from the shore. It is one of several volcanoes forming the Campanian volcanic arc. Vesuv ...

. The three ships carried some 9,000 rations and their crews assisted the victims to recover from the disaster. The division returned to France in time for a naval review on 16 September held in Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

that included detachments from Britain, Spain, and Italy. ''Bouvet'' and the other French ships then returned to Toulon. The following year, in January 1907, ''Bouvet'' was withdrawn from front-line service with the Mediterranean Squadron. Now part of the Second Squadron, she was retained on active service for the year, but with a reduced crew. In July 1908, the Mediterranean Fleet was reorganized and ''Bouvet'' was attached to the 3rd Battleship Division as its flagship, under the command of () Laurent Marin-Darbel, along with ''Jauréguiberry'' and the battleship .

Beginning in January 1909, with the commissioning of the six and s, the Mediterranean Squadron was reorganized into two battle squadrons; ''Bouvet'' was at that time assigned to the 3rd Division, part of the 2nd Battle Squadron, still the flagship of Marin-Darbel. Her place was taken the following year by ''Saint Louis'', and she remained out of service that year, with the exception of during the fleet maneuvers conducted in June, which she joined. In January 1911, she returned to service as the flagship of Adam in the 2nd Division of the 2nd Battle Squadron. On 5 October, the fleet was again reorganized and her place in what was now the 3rd Battle Squadron was taken by ''Charles Martel''. On 16 October 1912, ''Bouvet'', ''Gaulois'', ''Saint Louis'', ''Carnot'', ''Masséna'', and ''Jauréguiberry'' were activated for training duties as the 3rd Squadron of the Mediterranean Squadron; in July 1913, they were joined by ''Charlemagne''. The squadron was dissolved on 11 November, and ''Bouvet'', ''Saint Louis'', and ''Gaulois'' were assigned to the (). Training activities continued into 1914, and in March, the division joined the rest of the Mediterranean Squadron, which was now re-designated as the () for gunnery training off Corsica. Additional maneuvers were conducted beginning on 13 May, during which the fleet visited

Beginning in January 1909, with the commissioning of the six and s, the Mediterranean Squadron was reorganized into two battle squadrons; ''Bouvet'' was at that time assigned to the 3rd Division, part of the 2nd Battle Squadron, still the flagship of Marin-Darbel. Her place was taken the following year by ''Saint Louis'', and she remained out of service that year, with the exception of during the fleet maneuvers conducted in June, which she joined. In January 1911, she returned to service as the flagship of Adam in the 2nd Division of the 2nd Battle Squadron. On 5 October, the fleet was again reorganized and her place in what was now the 3rd Battle Squadron was taken by ''Charles Martel''. On 16 October 1912, ''Bouvet'', ''Gaulois'', ''Saint Louis'', ''Carnot'', ''Masséna'', and ''Jauréguiberry'' were activated for training duties as the 3rd Squadron of the Mediterranean Squadron; in July 1913, they were joined by ''Charlemagne''. The squadron was dissolved on 11 November, and ''Bouvet'', ''Saint Louis'', and ''Gaulois'' were assigned to the (). Training activities continued into 1914, and in March, the division joined the rest of the Mediterranean Squadron, which was now re-designated as the () for gunnery training off Corsica. Additional maneuvers were conducted beginning on 13 May, during which the fleet visited Bizerte

Bizerte (, ) is the capital and largest city of Bizerte Governorate in northern Tunisia. It is the List of northernmost items, northernmost city in Africa, located north of the capital Tunis. It is also known as the last town to remain under Fr ...

in French Tunisia

The French protectorate of Tunisia (; '), officially the Regency of Tunis () and commonly referred to as simply French Tunisia, was established in 1881, during the French colonial empire era, and lasted until Tunisian independence in 1956.

Th ...

, Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

in French Algeria

French Algeria ( until 1839, then afterwards; unofficially ; ), also known as Colonial Algeria, was the period of History of Algeria, Algerian history when the country was a colony and later an integral part of France. French rule lasted until ...

, and Ajaccio

Ajaccio (, , ; French language, French: ; or ; , locally: ; ) is the capital and largest city of Corsica, France. It forms a communes of France, French commune, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Corse-du-Sud, and head o ...

, Corsica.

World War I

Following the outbreak of World War I in July 1914, France announced generalmobilization

Mobilization (alternatively spelled as mobilisation) is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the ...

on 1 August. The next day, Admiral Augustin Boué de Lapeyrère ordered the entire French fleet to begin raising steam at 22:15 so the ships could sortie early the following morning. The bulk of the fleet, including the (designated as "Group C"), was sent to French North Africa, where they would escort the vital troop convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

s carrying elements of the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (, , ), is the principal Army, land warfare force of France, and the largest component of the French Armed Forces; it is responsible to the Government of France, alongside the French Navy, Fren ...

from North Africa back to France to counter the expected German invasion. At the time, the division was commanded by Émile Paul Amable Guépratte, and it was tasked with guarding against a possible attack by the German battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of att ...

, which instead fled to the Ottoman Empire. ''Bouvet'' and her division mates steamed first to Algiers and then Oran

Oran () is a major coastal city located in the northwest of Algeria. It is considered the second most important city of Algeria, after the capital, Algiers, because of its population and commercial, industrial and cultural importance. It is w ...

. There, they rendezvoused with one of the convoys and covered its voyage north to Sète

Sète (; , ), also historically spelled ''Cette'' (official until 1928) and ''Sette'', is a commune in the Hérault department, in the region of Occitania, southern France. Its inhabitants are called ''Sétois'' (male) and ''Sétoises'' (fem ...

on 6 August. From there, ''Bouvet'' and the battleships proceeded on to Toulon, before departing again for Algiers for another escort mission. Once the French Army units had completed their crossing by late August, the Group C ships were tasked with patrolling merchant traffic between Tunis and Sicily to prevent contraband

Contraband (from Medieval French ''contrebande'' "smuggling") is any item that, relating to its nature, is illegal to be possessed or sold. It comprises goods that by their nature are considered too dangerous or offensive in the eyes of the leg ...

shipments to the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

.

In November, she and the armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a pre-dreadnought battles ...

were sent to relieve the British armored cruisers and as guard ship

A guard ship is a warship assigned as a stationary guard in a port or harbour, as opposed to a coastal patrol boat, which serves its protective role at sea.

Royal Navy

In the Royal Navy of the eighteenth century, peacetime guard ships were usual ...

s at the northern entrance to the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

. She remained there only briefly, however, before she was ordered north to the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey th ...

to relieve the battleship on 20 December. Over the coming months, the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was built upon th ...

amassed a large fleet tasked with breaking through the Ottoman defenses that guarded the straits. During this period, before the start of major offensive operations, the Anglo-French fleet alternated between anchorages at Tenedos

Tenedos (, ''Tenedhos''; ), or Bozcaada in Turkish language, Turkish, is an island of Turkey in the northeastern part of the Aegean Sea. Administratively, the island constitutes the Bozcaada, Çanakkale, Bozcaada district of Çanakkale Provinc ...

and Mudros Bay on the island of Lemnos

Lemnos ( ) or Limnos ( ) is a Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within the Lemnos (regional unit), Lemnos regional unit, which is part of the North Aegean modern regions of Greece ...

, and it was tasked with patrolling the entrance to the straits to ensure that ''Goeben''—which had by then been transferred to the Ottoman Navy

The Ottoman Navy () or the Imperial Navy (), also known as the Ottoman Fleet, was the naval warfare arm of the Ottoman Empire. It was established after the Ottomans first reached the sea in 1323 by capturing Praenetos (later called Karamürsel ...

as ''Yavuz Sultan Selim''—did not attempt to sortie. On 1 February 1915, the ships sailed to Sigri Sigri may refer to:

* Sigri (village), Lesbos, Greece

*Sigri (stove)

{{ref improve, date=July 2023

A Sigri is a stove used for cooking, especially in North India. The fuel used is usually coal, dried cow dung and wood, therefore it is principally ...

on the island of Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of , with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, eighth largest ...

.

Dardanelles campaign

By mid-February 1915, the French and British had assembled a fleet of four French and twelve British battleships, including ''Bouvet'', to lead the assault on the Dardanelles. The plan called for Ottoman defenses to be neutralized to allow the fleet to enter theSea of Marmara

The Sea of Marmara, also known as the Sea of Marmora or the Marmara Sea, is a small inland sea entirely within the borders of Turkey. It links the Black Sea and the Aegean Sea via the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits, separating Turkey's E ...

and attack Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

directly. The first stage of the attack began on 19 February, which saw ''Bouvet'' and ''Suffren'', together with the British battlecruiser and the pre-dreadnought battleship

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built from the mid- to late- 1880s to the early 1900s. Their designs were conceived before the appearance of in 1906 and their classification as "pre-dreadnought" is retrospectively appli ...

s , , and , bombard the coastal defenses protecting the entrance of the straits. During the bombardment, ''Bouvet'' assisted the battleship ''Suffren'' by sending firing corrections via radio

Radio is the technology of communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 3 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmitter connec ...

while ''Gaulois'' provided counter-battery fire

Counter-battery fire (sometimes called counter-fire) is a battlefield tactic employed to defeat the enemy's indirect fire elements ( multiple rocket launchers, artillery and mortars), including their target acquisition, as well as their command ...

to suppress the Ottoman coastal artillery

Coastal artillery is the branch of the armed forces concerned with operating anti-ship artillery or fixed gun batteries in coastal fortifications.

From the Middle Ages until World War II, coastal artillery and naval artillery in the form of ...

. Another attempt was made six days later, with ''Bouvet'' again spotting for ''Gaulois''; this attack was more successful, and the French and British battleships silenced the outer fortresses, allowing minesweeper

A minesweeper is a small warship designed to remove or detonate naval mines. Using various mechanisms intended to counter the threat posed by naval mines, minesweepers keep waterways clear for safe shipping.

History

The earliest known usage of ...

s to enter the area and begin clearing the minefields protecting the straits. The French division steamed into the Gulf of Saros

Gulf of Saros or Saros Bay () is a gulf north of the Dardanelles, Turkey. Ancient Greeks called it the Gulf of Melas ().

The bay is long and wide. Far from industrialized areas and thanks to underwater currents, it is a popular summer recre ...

on the Aegean coast of the Gallipoli Peninsula

The Gallipoli Peninsula (; ; ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles strait to the east.

Gallipoli is the Italian form of the Greek name (), meaning ' ...

on 1 March to scout Ottoman positions in the area. They then covered the British battleships as they bombarded Ottoman positions in the straits on 5 March, before taking their turn the next day, when they attacked the fortification at Dardanus.

On 18 March, the French and British squadrons made another attack on the straits, directed at the inner ring of fortresses that guarded the narrowest part of the Dardanelles. The larger British contingent, commanded by Rear Admiral John de Robeck

Admiral of the Fleet Sir John Michael de Robeck, 1st Baronet, (10 June 1862 – 20 January 1928) was an officer in the Royal Navy. In the early years of the 20th century he served as Admiral of Patrols, commanding four flotillas of destroyers.

...

, was to make the initial attack at longer range, led by the powerful dreadnought battleship

The dreadnought was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an effect when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her were referred to as "dreadnoughts", ...

; once the batteries were reduced, the French ships, under Guépratte, were to enter the straits and attack at closer range. ''Bouvet'' and ''Suffren'' were to attack the fortresses on the Asian side of the straits, while ''Gaulois'' and ''Charlemagne'' were to silence the batteries on the European side. Mistakenly believing the Ottoman guns to have been largely neutralized by the British bombardment, Guépratte led his ships to within of the inner fortresses and engaged in an artillery duel. ''Suffren'' and ''Bouvet'' operated as a pair, taking alternating passes at high speed to make it more difficult for the Ottoman gunners to score hits. Nevertheless, by 14:00, ''Bouvet'' had taken several hits and two of her casemate guns had been knocked out. A serious fire had also been started on her bridge

A bridge is a structure built to Span (engineering), span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or railway) without blocking the path underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, whi ...

, though she had succeeded in neutralizing the Hamidieh battery. In the course of the attack on the fortresses, ''Bouvet'' sustained eight hits from Turkish artillery fire. Her forward turret was disabled after the propellant gas extractor broke down.

At around 13:45, de Robeck had ordered Guépratte to withdraw his ships so their British counterparts could take their turn against the Ottoman fortifications. ''Bouvet'' was at that time battling the fort at Namazieh, and her commander, ( Ship of the line captain) Rageot de la Touche, initially did not respond to Guépratte's instruction to follow ''Suffren'' out of the narrows. After Guépratte again ordered him to break off contact, de la Touche turned ''Bouvet'' south to withdraw. Shortly thereafter, ''Bouvet'' was rocked by a major explosion, followed by a large cloud of red-black smoke; observers aboard the other ships could not immediately tell whether she had been hit by an Ottoman shell, torpedoed by a shore-mounted torpedo battery, or if she had struck a mine. The escorting destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

s and picket boats raced to the scene to pick up her crew, but in the span of just two minutes, ''Bouvet'' capsized and sank. A total of 75 of her crew were pulled from the water; 24 officers and 619 enlisted men died in the sinking. Most of the survivors were rescued by the British destroyer . The ship was in poor condition at the time due to her age, which likely contributed to her rapid sinking, though there was some speculation that her ammunition magazine exploded. Guépratte himself remarked that "that ship must have had poor stability." It was later determined that ''Bouvet'' had struck a mine, which was part of a field that had been freshly laid a week before the attack, and was unknown to the Allies.

Despite the sinking of ''Bouvet'', the first such loss of the day, the British remained unaware of the minefield, thinking the explosion had been caused by a shell or torpedo. Subsequently, two British pre-dreadnoughts, and , were sunk and the battlecruiser ''Inflexible'' was damaged by the same minefield. ''Suffren'' and ''Gaulois'' were both badly damaged by coastal artillery during the engagement. The loss of ''Bouvet'' and the two British battleships during the 18 March attack was a major factor in the decision to abandon a naval strategy to take Constantinople, and instead opt for the Gallipoli land campaign. While the Franco-British forces began preparations for the attack, ''Bouvet''s place in the fleet was filled by .

Wreck

In the early 2010s, Turkish marine archaeologists conducted sonar surveys of many of the wrecks from the Dardanelles campaign, including ''Bouvet''. Research on the wrecks had long been difficult, as the area's status as a busy maritime artery and the strong current combine to make diving difficult. The survey of ''Bouvet'', which lies upside down on the sea floor, revealed that a 305 mm shell from an Ottoman shore battery had struck the ship at thewaterline

The waterline is the line where the hull of a ship meets the surface of the water.

A waterline can also refer to any line on a ship's hull that is parallel to the water's surface when the ship is afloat in a level trimmed position. Hence, wate ...

amidships on the same side as she struck the mine, which contributed to the fatal flooding that caused her to rapidly capsize and sink.

Footnotes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Bouvet Gallipoli campaign Ships sunk by mines Maritime incidents in 1915 World War I battleships of France Ships built in France World War I shipwrecks in the Dardanelles 1896 ships Battleships of the French Navy Ships with Belleville boilers Shipwrecks of Turkey