Frederick Selous on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Frederick Courteney Selous, DSO (; 31 December 1851 – 4 January 1917) was a

His private collection of trophies was given by his widow to the Natural History Museum, where in June 1920 a national memorial to him was unveiled, a bronze half-figure by William Colton. A Selous Scholarship was also founded at his old school, Rugby.

His private collection of trophies was given by his widow to the Natural History Museum, where in June 1920 a national memorial to him was unveiled, a bronze half-figure by William Colton. A Selous Scholarship was also founded at his old school, Rugby.

''Great and small game of Africa''

Rowland Ward Ltd., London. Pp. 544–568. He was awarded the

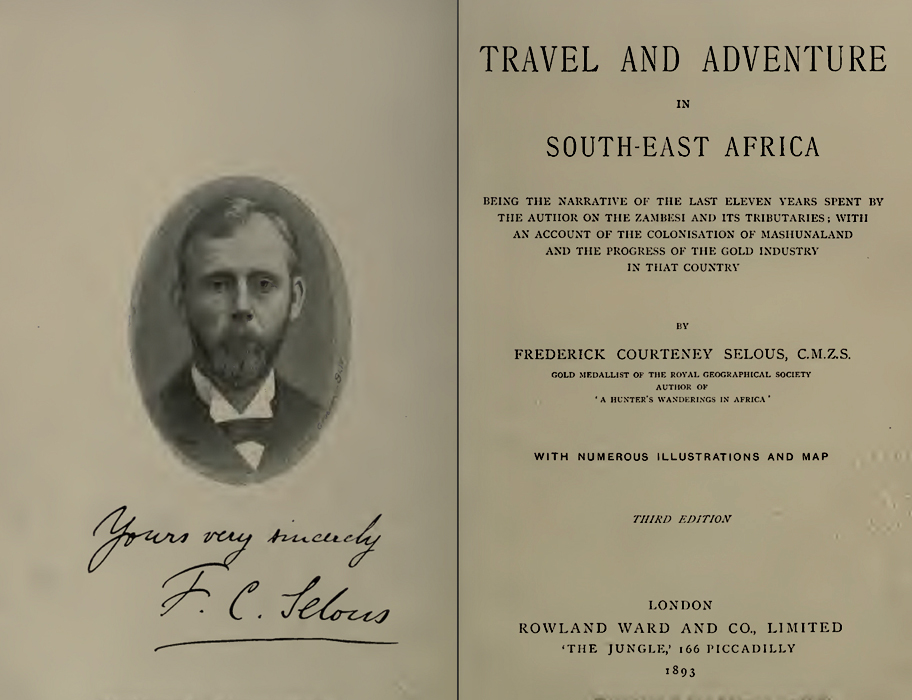

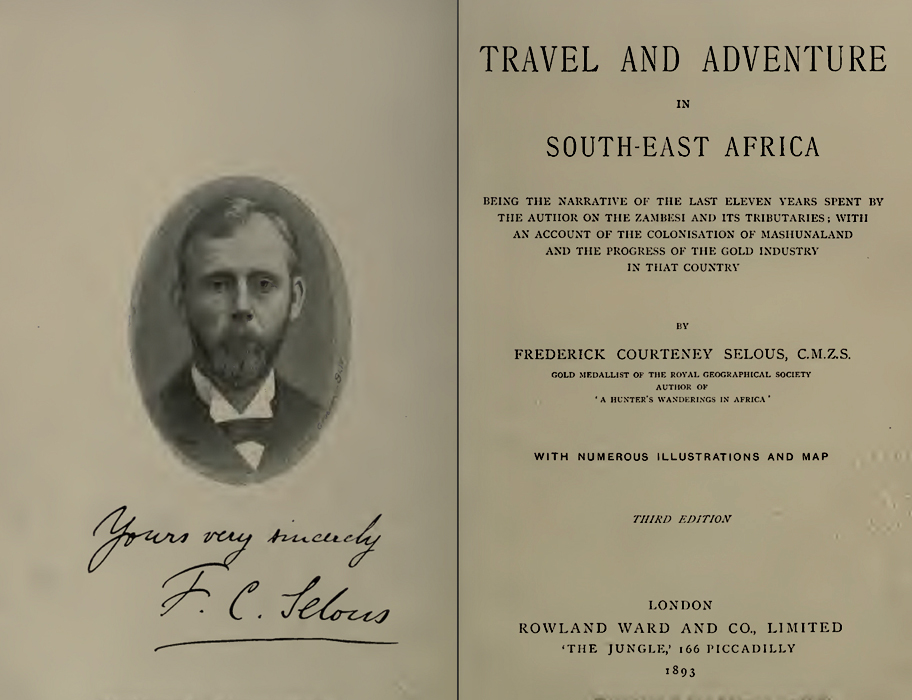

File:SelousStudioPortrait2RoyalGeographicalSociety.jpg, Studio portrait with his Gibbs Metford rifle and hunting attire.

File:ReturnFromHuntingSelous.jpg, Selous returning from stag hunt in

* The book has had many reprints.The fifth edition (1907) i

* The book has had many reprints.The fifth edition (1907) i

online available

in

Roosevelt’s quest for wilderness: a comparison of Roosevelt’s visits to Yellowstone and Africa

*''Taps for the Great Selous'', essay by Major

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

explorer, army officer

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," fro ...

, professional hunter

A professional hunter (less frequently referred to as market or commercial hunter and regionally, especially in Britain and Ireland, as professional stalker or gamekeeper) is a person who Hunting, hunts and/or manages Game (hunting), game by profe ...

, and conservationist, famous for his exploits in Southeast Africa

Southeast Africa, or Southeastern Africa, is an African region that is intermediate between East Africa and Southern Africa. It comprises the countries Botswana, Eswatini, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Rwanda, South Africa, Tanza ...

. His real-life adventures inspired Sir Henry Rider Haggard to create the fictional character Allan Quatermain. Selous was a friend of Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

, Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes ( ; 5 July 185326 March 1902) was an English-South African mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. He and his British South Africa Company founded th ...

and Frederick Russell Burnham

Major (rank), Major Frederick Russell Burnham Distinguished Service Order, DSO (May 11, 1861 – September 1, 1947) was an American scout and world-traveling adventurer. He is known for his service to the British South Africa Company and to t ...

. He was pre-eminent within a group of big game hunters that included Abel Chapman and Arthur Henry Neumann

Arthur Henry Neumann (12 June 1850 – 29 May 1907) was an English explorer, hunter, soldier, farmer and travel writer famous for his exploits in Equatorial East Africa. In 1898 he published ''Elephant Hunting in East Equatorial Africa''. xix, 4 ...

. He was the older brother of the ornithologist

Ornithology, from Ancient Greek ὄρνις (''órnis''), meaning "bird", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study", is a branch of zoology dedicated to the study of birds. Several aspects of ornithology differ from related discip ...

and writer Edmund Selous

Edmund Selous (14 August 1857 – 25 March 1934) was a British ornithologist and writer. He was the younger brother of big-game hunter Frederick Selous. Born in London, the son of a wealthy stockbroker, Selous was educated privately and matri ...

.

Early life and exploration

Frederick Courteney Selous was born on 31 December 1851 atRegent's Park

Regent's Park (officially The Regent's Park) is one of the Royal Parks of London. It occupies in north-west Inner London, administratively split between the City of Westminster and the London Borough of Camden, Borough of Camden (and historical ...

, London, as one of the five children of an upper middle class family, the third-generation descendant of a Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

immigrant. His father, Frederick Lokes Slous (original spelling) (1802–1892), was Chairman of the London Stock Exchange

The London Stock Exchange (LSE) is a stock exchange based in London, England. the total market value of all companies trading on the LSE stood at US$3.42 trillion. Its current premises are situated in Paternoster Square close to St Paul's Cath ...

, and his mother, Ann Holgate Sherborn (1827–1913), was a published poet. One of his uncles was a painter, Henry Courtney Selous. Frederick had three sisters (Florence (born 1850), Annie Berryman (born 1853), and Sybil Jane (born 1862)), and one brother (Edmund Selous

Edmund Selous (14 August 1857 – 25 March 1934) was a British ornithologist and writer. He was the younger brother of big-game hunter Frederick Selous. Born in London, the son of a wealthy stockbroker, Selous was educated privately and matri ...

(1857–1934)) who became a famous ornithologist

Ornithology, from Ancient Greek ὄρνις (''órnis''), meaning "bird", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study", is a branch of zoology dedicated to the study of birds. Several aspects of ornithology differ from related discip ...

. Frederick's love for the outdoors and wildlife was shared only by his brother; however, all of the family members were artistically inclined, as well as being successful in business.

At 42, Selous settled in Worplesdon

Worplesdon is a village NNW of Guildford in Surrey, England and a large dispersed civil parish that includes the settlements of: Worplesdon itself (including its central church area, Perry Hill), Fairlands, Jacobs Well, Rydeshill and Wood S ...

near Guildford

Guildford () is a town in west Surrey, England, around south-west of central London. As of the 2011 census, the town has a population of about 77,000 and is the seat of the wider Borough of Guildford, which had around inhabitants in . The nam ...

in Surrey

Surrey () is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Greater London to the northeast, Kent to the east, East Sussex, East and West Sussex to the south, and Hampshire and Berkshire to the wes ...

, and married 20-year-old Marie Catherine Gladys Maddy (born 1874), daughter of clergyman Canon Henry William Maddy. They had three sons: Frederick Hatherley Bruce Selous (1898–1918), Harold Sherborn Selous (1899-1954), and Bertrand Selous, who was born prematurely on 6 July 1915 and died five days later.

Youth

From a young age, Selous was drawn by stories of explorers and their adventures. Furthermore, while in school, he started establishing personal collections of various bird eggs and butterflies and studying natural history. One account is related by his schoolmaster atNorthamptonshire

Northamptonshire ( ; abbreviated Northants.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It is bordered by Leicestershire, Rutland and Lincolnshire to the north, Cambridgeshire to the east, Bedfordshi ...

when Selous was 10 years old:

On 15 January 1867, 15-year-old Selous was one of the survivors of the Regent's Park skating disaster

The Regent's Park skating disaster occurred on 15 January 1867 when 40 people died after the ice broke on the lake in London's Regent's Park pitching about 200 people into icy water up to deep. Most were rescued by bystanders but 40 people died ...

, when the ice covering the local lake broke with around 200 skaters on it, leaving 40 dead by drowning and freezing. He escaped by crawling on broken ice slabs to the shore.

He was educated at Bruce Castle School, Tottenham,Joseph Comyns Carr, ''Some eminent Victorians: personal recollections in the world of art and letters'' (Duckworth & Co., 1908), p. 4 then at Rugby, and finally abroad in Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

. His parents hoped that he would become a doctor. However, his love for natural history led him to study the ways of wild animals in their native habitat. His imagination was strongly fuelled by the literature of African exploration and hunting, Dr. David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, and an explorer in Africa. Livingstone was married to Mary Moffat Livings ...

, and William Charles Baldwin in particular.

African exploration

Going toSouth Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

when he was 19, he traveled from the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

to Matabeleland

Matabeleland is a region located in southwestern Zimbabwe that is divided into three provinces: Matabeleland North, Bulawayo, and Matabeleland South. These provinces are in the west and south-west of Zimbabwe, between the Limpopo and Zambezi ...

, which he reached early in 1872, and where (according to his own account) he was granted permission by Lobengula

Lobengula Khumalo ( 1835 – 1894) was the second and last official king of the Northern Ndebele people (historically called Matabele in English). Both names in the Zimbabwean Ndebele language, Ndebele language mean "the men of the long shields ...

, King of the Ndebele, to shoot game anywhere in his dominions.

From then until 1890, Selous hunted and explored over the little-known regions north of the Transvaal

Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name ''Transvaal''.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; ...

and south of the Congo Basin

The Congo Basin () is the sedimentary basin of the Congo River. The Congo Basin is located in Central Africa, in a region known as west equatorial Africa. The Congo Basin region is sometimes known simply as the Congo. It contains some of the larg ...

(with a few brief intervals spent in England), shooting African elephant

African elephants are members of the genus ''Loxodonta'' comprising two living elephant species, the African bush elephant (''L. africana'') and the smaller African forest elephant (''L. cyclotis''). Both are social herbivores with grey skin. ...

s and collecting specimens of all kinds for museums and private collections. His travels added greatly to the knowledge of the country now known as Zimbabwe

file:Zimbabwe, relief map.jpg, upright=1.22, Zimbabwe, relief map

Zimbabwe, officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Bots ...

. He made valuable ethnological

Ethnology (from the , meaning 'nation') is an academic field and discipline that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural anthropology, cultural, social anthropology, so ...

investigations, and throughout his wanderings—often among people who had never previously seen a white man—he maintained cordial relations with the chiefs and tribes, winning their confidence and esteem, notably so in the case of Lobengula.

In 1890, Selous entered the service of the British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSACo) was chartered in 1889 following the amalgamation of Cecil Rhodes' Central Search Association and the London-based Exploring Company Ltd, which had originally competed to capitalize on the expecte ...

, at the request of magnate Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes ( ; 5 July 185326 March 1902) was an English-South African mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. He and his British South Africa Company founded th ...

, acting as a guide to the pioneer expedition to Mashonaland

Mashonaland is a region in northeastern Zimbabwe. It is home to nearly half of the population of Zimbabwe. The majority of the Mashonaland people are from the Shona tribe while the Zezuru and Korekore dialects are most common. Harare is the larg ...

. Over of road were constructed through a country of forest, mountain, and swamp. He then went east to Manica, concluding arrangements that brought the country there under British control. Coming to England in December 1892, he was awarded the Founder's Medal

The Founder's Medal is a medal awarded annually by the Royal Geographical Society, upon approval of the Sovereign of the United Kingdom, to individuals for "the encouragement and promotion of geographical science and discovery".

Foundation

From ...

of the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

in recognition of his extensive explorations and surveys, of which he gave a summary in a journal article entitled "Twenty Years in Zambesia".

Military career

Rhodesia and First World War

Selous returned to Africa to take part in theFirst Matabele War

The First Matabele War was fought between 1893 and 1894 in modern-day Zimbabwe. It pitted the British South Africa Company against the Ndebele (Matabele) Kingdom. Lobengula, king of the Ndebele, had tried to avoid outright war with the compa ...

of 1893 and was wounded during the advance on Bulawayo

Bulawayo (, ; ) is the second largest city in Zimbabwe, and the largest city in the country's Matabeleland region. The city's population is disputed; the 2022 census listed it at 665,940, while the Bulawayo City Council claimed it to be about ...

. It was during this advance that he first met fellow scout Frederick Russell Burnham, who had only just arrived in Africa and who continued on with the small scouting party to Bulawayo and observed the self-destruction of the Ndebele settlement as ordered by Lobengula

Lobengula Khumalo ( 1835 – 1894) was the second and last official king of the Northern Ndebele people (historically called Matabele in English). Both names in the Zimbabwean Ndebele language, Ndebele language mean "the men of the long shields ...

.

Selous returned to England, and married Mary Maddy in 1894. In 1896 he returned to Africa with his wife and settled on a landed property in Essexvale, Matabeleland

Matabeleland is a region located in southwestern Zimbabwe that is divided into three provinces: Matabeleland North, Bulawayo, and Matabeleland South. These provinces are in the west and south-west of Zimbabwe, between the Limpopo and Zambezi ...

, overlooking the Ncema River. When the Second Matabele War

The Second Matabele War, also known as the First Chimurenga, was fought between 1896 and 1897 in the region that later became Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). The conflict was initially between the British South Africa Company and the Mata ...

broke out, Selous took a prominent part in the fighting which followed, serving as a leader in the Bulawayo Field Force, and published an account of the campaign entitled ''Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia'' (1896). It was during this time that he met and fought alongside Robert Baden-Powell

Lieutenant-General Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell, ( ; 22 February 1857 – 8 January 1941) was a British Army officer, writer, founder of The Boy Scouts Association and its first Chief Scout, and founder, with ...

, who was then a Major and newly appointed to the British Army headquarters staff in Matabeleland.

During the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, after initially being rejected on account of his age (64), Selous rejoined the British Army as a subaltern and saw active service in the fighting against German colonial forces in the East Africa Campaign. On 23 August 1915, he was promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

in the uniquely-composed 25th (Frontiersmen) Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, and on 26 September 1916 was awarded the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a Military awards and decorations, military award of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly throughout the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth, awarded for operational gallantry for highly successful ...

, the citation reading:

Death and legacy

On 4 January 1917, Selous was fighting in the bush war on the banks of theRufiji River

The Rufiji River lies entirely within Tanzania. It is also the largest and longest river in the country. The river is formed by the confluence of the Kilombero and Luwegu rivers. It is approximately long, with its source in southwestern Tanzani ...

against German colonial Schutztruppen, which outnumbered his troops five to one. That morning, he was creeping forward in combat during a minor engagement in which he raised his head and binoculars to locate the enemy. He was shot in the head by a German sniper and was killed instantly.

Upon getting the news, former US President Theodore Roosevelt, his close friend, wrote:

He was buried under a tamarind

Tamarind (''Tamarindus indica'') is a Legume, leguminous tree bearing edible fruit that is indigenous to tropical Africa and naturalized in Asia. The genus ''Tamarindus'' is monotypic taxon, monotypic, meaning that it contains only this spe ...

tree near the place of his death, at Chokawali on the Rufiji River, in today's Selous Game Reserve, Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

, in a modest, flat stone grave with a simple bronze plaque reading: "CAPTAIN F.C. SELOUS D.S.O., 25TH ROYAL FUSILIERS, KILLED IN ACTION 4.1.17." Exactly a year later, on 4 January 1918, his son, Captain Frederick Hatherley Bruce MC, who was a pilot in the Royal Flying Corps

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was the air arm of the British Army before and during the First World War until it merged with the Royal Naval Air Service on 1 April 1918 to form the Royal Air Force. During the early part of the war, the RFC sup ...

, was killed in a flight over Menin Road, Belgium.(Memorials of Rugbeians who fell in the Great War, Volume VI)

His private collection of trophies was given by his widow to the Natural History Museum, where in June 1920 a national memorial to him was unveiled, a bronze half-figure by William Colton. A Selous Scholarship was also founded at his old school, Rugby.

His private collection of trophies was given by his widow to the Natural History Museum, where in June 1920 a national memorial to him was unveiled, a bronze half-figure by William Colton. A Selous Scholarship was also founded at his old school, Rugby.

Hunter, naturalist and conservationist

Hunting icon

Selous is remembered for his powerful ties, such as those with Theodore Roosevelt andCecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes ( ; 5 July 185326 March 1902) was an English-South African mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. He and his British South Africa Company founded th ...

, as well as for his military achievements and the books that he left behind. However, he is best remembered as one of the world's most revered hunters, as he pursued big-game hunting

Big-game hunting is the hunting of large game animals for trophies, taxidermy, meat, and commercially valuable animal by-products (such as horns, antlers, tusks, bones, fur, body fat, or special organs). The term is often associated with t ...

in his southern African homelands and in wildernesses worldwide.

Accounts of his youth are filled with stories of trespassing, poaching, and brawling, almost all within romanticized and humorous portrayals, but one in particular from 1870 stands out as more serious. In Wiesbaden

Wiesbaden (; ) is the capital of the German state of Hesse, and the second-largest Hessian city after Frankfurt am Main. With around 283,000 inhabitants, it is List of cities in Germany by population, Germany's 24th-largest city. Wiesbaden form ...

, Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

, he knocked unconscious a Prussian game warden who tackled him while he was stealing buzzard eggs for his collection, and he had to leave the country at once to avoid imprisonment. Then, he moved to Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

, and in Salzburg

Salzburg is the List of cities and towns in Austria, fourth-largest city in Austria. In 2020 its population was 156,852. The city lies on the Salzach, Salzach River, near the border with Germany and at the foot of the Austrian Alps, Alps moun ...

, he went big game hunting for the first time in the nearby Alps

The Alps () are some of the highest and most extensive mountain ranges in Europe, stretching approximately across eight Alpine countries (from west to east): Monaco, France, Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Germany, Austria and Slovenia.

...

, where he shot two chamois

The chamois (; ) (''Rupicapra rupicapra'') or Alpine chamois is a species of Caprinae, goat-antelope native to the mountains in Southern Europe, from the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Apennines, the Dinarides, the Tatra Mountains, Tatra to the Carpa ...

.

On 4 September 1871, at the age of 19, he left England with £400 in his pocket and was determined to earn his living as a professional elephant hunter. By the age of 25, he was known across South Africa as one of the most successful ivory hunters of the day.

Selous journeyed in pursuit of big game to Europe (Bavaria

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a States of Germany, state in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the list of German states by area, largest German state by land area, comprising approximately 1/5 of the total l ...

, Germany in 1870, Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

, then Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

but now Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

in 1899, Mull Island, Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

in 1894, Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

in 1902, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

in 1907), Asia (Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

in 1894–95, 1897, 1907), North America (Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

, Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in great-circle distance, straight-line distance from the northernmost part of Western Can ...

in 1897 and 1898, Eastern Canada

Eastern Canada (, also the Eastern provinces, Canadian East or the East) is generally considered to be the region of Canada south of Hudson Bay/ Hudson Strait and east of Manitoba, consisting of the following provinces (from east to west): Newf ...

in 1900–1901, 1905, Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

and Yukon

Yukon () is a Provinces and territories of Canada, territory of Canada, bordering British Columbia to the south, the Northwest Territories to the east, the Beaufort Sea to the north, and the U.S. state of Alaska to the west. It is Canada’s we ...

in 1904, 1905) and the "dark continent" in a territory that extends from today's South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

and Namibia

Namibia, officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country on the west coast of Southern Africa. Its borders include the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Angola and Zambia to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south; in the no ...

all the way up into central Sudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

where he collected specimens of virtually every medium and large African mammal species.

On 2 May 1902, Selous was elected Associate Member of the Boone and Crockett Club

The Boone and Crockett Club is an American nonprofit organization that advocates fair chase hunting in support of habitat conservation. The club is North America's oldest wildlife and habitat conservation organization, founded in the United S ...

, a wildlife conservation organization founded by Theodore Roosevelt and George Bird Grinnell

George Bird Grinnell (September 20, 1849 – April 11, 1938) was an American anthropologist, historian, naturalist, and writer. Originally specializing in zoology, he became a prominent early conservationist and student of Native American life. ...

in 1887.

In 1909–1910, Selous accompanied American ex-president Roosevelt in his famous African safari. Contrary to popular belief, Selous did not lead Roosevelt's 1909 expedition to British East Africa

East Africa Protectorate (also known as British East Africa) was a British protectorate in the African Great Lakes, occupying roughly the same area as present-day Kenya, from the Indian Ocean inland to the border with Uganda in the west. Cont ...

, the Congo, and Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

. While Selous was a member of this expedition from time to time and helped organize the safari's logistics, the excursion was in fact led by R. J. Cunninghame. Roosevelt wrote of Selous:

In 1909, Selous co-founded the Shikar Club, a big-game hunters' association, with two other British Army Captains, Charles Edward Radclyffe and P. B. Vanderbyl, and regularly met at the Savoy Hotel

The Savoy Hotel is a luxury hotel located in the Strand in the City of Westminster in central London, England. Built by the impresario Richard D'Oyly Carte with profits from his Gilbert and Sullivan opera productions, it opened on 6 August 1 ...

in London. The association's president was The 5th Earl of Lonsdale; another founding member included the artist, explorer, and Selous biographer John Guille Millais

John Guille Millais ( , also ; 24 March 1865 – 24 March 1931) was a British artist, naturalist, gardener and travel writer who specialised in wildlife and flower portraiture. He travelled extensively around the world in the late Victorian per ...

.

In 1910, he represented Britain at the Congress of Field Sports in Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

.

He was a rifleman icon and a valued expert in firearms. Early in his hunting career, in the mid-1870s, Selous favored a four bore black powder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

muzzleloader

A muzzleloader is any firearm in which the user loads the bullet, projectile and the propellant charge into the Muzzle (firearms), muzzle end of the gun (i.e., from the forward, open end of the gun's barrel). This is distinct from the modern desi ...

for killing an elephant, a short-barreled musket firing a bullet with as much as of black powder, one of the largest hunting calibers fabricated. Between 1874 and 1876 he killed seventy-eight elephants with that gun, but eventually, there was a double loading incident together with other recoil problems from it, and he finally gave it up as too "upsetting my nerve". He used a ten-bore muzzleloader to hunt lions.

After black powder muzzleloader firearms became obsolete

Obsolescence is the process of becoming antiquated, out of date, old-fashioned, no longer in general use, or no longer useful, or the condition of being in such a state. When used in a biological sense, it means imperfect or rudimentary when comp ...

, he adopted a breech-loading 10 bore as shown in "A Hunters Wanderings in Africa" and by 1880 he was using his favorite, black powder breech-loading rifle a .461 No 1 Gibbs / Metford / Farquharson single shot later he was approached by both Birmingham and London gunmakers in hopes of his endorsement, with Holland and Holland providing two Holland and Woodward patent single-shot rifles (often confused in photos as Farquharson's) in the two calibers: a 303 and a 375 2 1/2" and later a .425 Westley Richards bolt-action rifle. There are quotes as to how Selous was not a crack shot, but a rather ordinary marksman, yet most agree that was just another personal statement of modesty from Selous himself. Regardless, he remains an iconic rifleman figure and, following in the tradition of others, the German gunmaker Blaser and the Italian gunmaker Perugini Visini chose to name their top line safari rifles the Selous after him.

Naturalist

Many of the Selous trophies entered into museums and international taxidermy and natural-history collections, notably that of theNatural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history scientific collection, collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleo ...

in London. In their ''Selous Collection'' they have 524 mammals from three continents, all shot by him, including 19 lion

The lion (''Panthera leo'') is a large Felidae, cat of the genus ''Panthera'', native to Sub-Saharan Africa and India. It has a muscular, broad-chested body (biology), body; a short, rounded head; round ears; and a dark, hairy tuft at the ...

s. In the last year of his life, while in combat in 1916, he was known to carry his butterfly net in the evening and collect specimens, for the same institution. Overall, more than five thousand plants and animal specimens were donated by him to the Natural History section of the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

. This collection was held in 1881 in the new Natural History Museum in South Kensington (which became an independent institution in 1963). Here, posthumously in 1920, they unveiled a bronze bust of him in the Main Hall, where it stands to this day. He is mentioned widely in foremost taxidermist Rowland Wards catalogs for world's largest animal specimens hunted, where Selous is ranked in many trophy categories, including rhinoceros

A rhinoceros ( ; ; ; : rhinoceros or rhinoceroses), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant taxon, extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates (perissodactyls) in the family (biology), famil ...

, elephant and many ungulates

Ungulates ( ) are members of the diverse clade Euungulata ("true ungulates"), which primarily consists of large mammals with hooves. Once part of the clade "Ungulata" along with the clade Paenungulata, "Ungulata" has since been determined to b ...

.Bryden, H. A. (ed.) (1899)''Great and small game of Africa''

Rowland Ward Ltd., London. Pp. 544–568. He was awarded the

Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

's Founder's Medal

The Founder's Medal is a medal awarded annually by the Royal Geographical Society, upon approval of the Sovereign of the United Kingdom, to individuals for "the encouragement and promotion of geographical science and discovery".

Foundation

From ...

in 1893 "in recognition of twenty years' exploration and surveys in South Africa".

In 1896, British zoologist William Edward de Winton (1856–1922), named a new African small Carnivora

Carnivora ( ) is an order of placental mammals specialized primarily in eating flesh, whose members are formally referred to as carnivorans. The order Carnivora is the sixth largest order of mammals, comprising at least 279 species. Carnivor ...

, '' Paracynictis selousi'' or the Selous mongoose, in his honour.Nowak, Ronald. Walker’s Carnivores of the World. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, 2005 Also, a subspecies of the African Sitatunga

The sitatunga (''Tragelaphus spekii'') or marshbuck is a swamp-dwelling medium-sized antelope found throughout central Africa, centering on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo, Cameroon, parts of South Sudan, Southern ...

antelope

The term antelope refers to numerous extant or recently extinct species of the ruminant artiodactyl family Bovidae that are indigenous to most of Africa, India, the Middle East, Central Asia, and a small area of Eastern Europe. Antelopes do ...

, (''Tragelaphus spekii selousi''), bears his name.

Conservationist

Selous noticed over time how the impact of European hunters was leading to a significant reduction in the amount of game available in Africa. In 1881, he commented that: This realization led Selous, and other big game hunters of his time, to become keen advocates of faunal conservation. Eventually, colonial governments passed laws enforcing hunting regulations and establishing game reserves, with the aim of preventing the outright extinction of certain species and of preserving animal stocks for future white sportsmen. The Selous Game Reserve in southeasternTanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

is a hunting reserve named in his honor. Established in 1922, it covers an area of along the rivers Kilombero

Kilombero District is a Districts of Tanzania, district in Morogoro Region, south-western Tanzania.

The district is situated in a vast floodplain, between the Kilombero River in the south-east and the Udzungwa-Mountains in the north-west. On the ...

, Ruaha, and Rufiji. The area first became a hunting reserve in 1905, although it is rarely visited by humans due to the significant presence of the Tsetse fly

Tsetse ( , or ) (sometimes spelled tzetze; also known as tik-tik flies) are large, biting flies that inhabit much of tropical Africa. Tsetse flies include all the species in the genus ''Glossina'', which are placed in their own family, Gloss ...

. In 1982 it was designated a UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

due to the diversity of its wildlife and undisturbed nature.

Selous as man and character

Portrait in literature

Frederick Courteney Selous's image remains a classic, romantic portrait of a properVictorian period

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the reign of Queen Victoria, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. Slightly different definitions are sometimes used. The era followed th ...

English gentleman of the colonies, one whose real-life adventures and exploits of almost epic proportions generated successful Lost World

The lost world is a subgenre of the fantasy or science fiction genres that involves the discovery of an unknown Earth civilization. It began as a subgenre of the late- Victorian adventure romance and remains popular into the 21st century.

The ...

and Steampunk

Steampunk is a subgenre of science fiction that incorporates retrofuturistic technology and Applied arts, aesthetics inspired by, but not limited to, 19th-century Industrial Revolution, industrial steam engine, steam-powered machinery. Steampun ...

genre fictional characters like Allan Quatermain, to a large extent an embodiment of the popular " white hunter" concept of the times; yet he remained a modest and stoic pillar in personality all throughout his life. As for himself, he was featured in the "Young Indiana Jones" and "Rhodes" series. He was widely remembered in real tales of war, exploration, and big game hunting as a balanced blend between gentleman officer and epic wild man.

Appearance and character

He excelled in cricket, rugby, cycling, swimming, and tennis. He loved the outdoors, developing a rugged and robust physique by trekking, packing, marching, and hunting. He was also an accomplished rider, and he waged war and hunted much on horses. To the African locals, he was the "best white runner" (in the endurance aspect, similar as to native bushmen's concept). While in England, all his life he played sports, he still did half-day 100-mile bicycle races when almost sixty years old. Millais, friend and biographer, wrote: "As a sport, he loved cricket most, and played regularly for his club at Worplesdon taking part in all their matches until 1915…'Big Game Hunters' vs. 'Worplesdon' was always a great and solemn occasion."Television accounts

* ''The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles

''The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles'' (sometimes referred to as ''Young Indy'') is an American television series that aired on ABC from March 4, 1992, to July 24, 1993. Filming took place in various locations around the world, with "Old Indy" ...

'' (TV-Series, 1992–1993) ; played by Paul Freeman

** ''British East Africa, September 1909'' (1992)

** ''Young Indiana Jones and the Phantom Train of Doom, German East Africa, November 1916'' (1993)

* ''Rhodes'' (TV Mini-Series, 1996) ; played by Paul Slabolepszy

Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, book illustration, 1908.

File:Selousmemorial.jpg, Captain Selous Memorial is in the wall just to the left of the elephant tusks. (The elephant is no longer displayed).

File:Captain frederick c selous.jpg, Close up picture of the Selous Memorial in the wall in the main hall of the Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history scientific collection, collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleo ...

File:RhinoSelous.jpg, Skull of a record white rhino

The white rhinoceros, also known as the white rhino or square-lipped rhinoceros (''Ceratotherium simum''), is the largest extant species of rhinoceros and the most Sociality, social of all rhino species, characterized by its wide mouth adapted f ...

, shot by Selous in Mashonaland

Mashonaland is a region in northeastern Zimbabwe. It is home to nearly half of the population of Zimbabwe. The majority of the Mashonaland people are from the Shona tribe while the Zezuru and Korekore dialects are most common. Harare is the larg ...

, 1880.

File:ElkSelous.jpg, Head of a wapiti

The elk (: ''elk'' or ''elks''; ''Cervus canadensis'') or wapiti, is the second largest species within the deer family, Cervidae, and one of the largest terrestrial mammals in its native range of North America and Central and East Asia. T ...

, shot by Selous at Cabin Creek, Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

, 1897.

Chronology of works

By Frederick Courteney Selous: * The book has had many reprints.The fifth edition (1907) i

* The book has had many reprints.The fifth edition (1907) ionline available

in

Biodiversity Heritage Library

The Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL) is the world’s largest open-access digital library for biodiversity literature and archives. BHL operates as a worldwide consortium of natural history, botanical, research, and national libraries working ...

. Annie Berryman Selous, Frederick's sister drew "ten illustrations, representing the hunting-scenes which embellish my pages, all of which were drawn under my own supervision"; they were engraved in wood by Edward Whymper

Edward Whymper FRSE (27 April 184016 September 1911) was an English mountaineer, explorer, illustrator, and author best known for the first ascent of the Matterhorn in 1865. Four members of his climbing party were killed during the descent. W ...

. Other illustrations were produced by Joseph Smit

Joseph Smit (18 July 1836 – 4 November 1929) was a Dutch zoological illustrator. L.B. Holthuis, Leiden, (1958, 1995) ''Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, 1820 - 1958''. page 47reprint manuscript, PDF

Background

Smit was born in Lisse. He ...

. (p. viii/ix)

* ''Travel and Adventure in South-East Africa: Being the Narrative of the Last Eleven Years Spent by the Author on the Zambesi and its Tributaries; With an Account of the Colonisation of Mashunaland and the Progress of the Gold Industry in That Country '' (1893)

* ''Sunshine & Storm in Rhodesia: Being a Narrative of Events in Matabeleland Both Before and During the Recent Native Insurrection up to the Date of the Disbandment of the Bulawayo Field Force.'' (1896),

* ''Sport & Travel East and West'' (1900)

* ''Living Animals of the World; A Popular Natural History With One Thousand Illustrations'' (London, 1902)

* ''Newfoundland Guide Book'' (1905)

* ''Recent Hunting Trips in British North America'' (1907)

* ''African Nature Notes and Reminiscences'' with foreword by Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

(1908)

* ''Africa's Greatest Hunter: the Lost Writings of Frederick C. Selous'', edited by Dr James A. Casada (1998)

Selous also wrote the foreword to Africa's most popular man-eater story: ''The man-eaters of Tsavo and other East African Adventures by Lieut.-Col. J. H. Patterson, D.S.O. With a foreword by Frederick Courteney Selous'' (London, 1907).

Besides the works mentioned, Selous made numerous contributions to ''The Geographical Journal

''The Geographical Journal'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal of the Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers). It publishes papers covering research on all aspects of geography. It also publishes shorter ...

'', '' the Field'', and other journals.

;Writings by others on Frederick Courtenay Selous

* ''Big Game Shooting'', volume. 1, edited by Clive Phillipps-Wolley (London, 1894)

* ''Records of Big Game'' by Rowland Ward FZS (London, fifth edition, 1907)

* ''The life of Frederick Courtenay Selous, D.S.O.'' by John Guille Millais

John Guille Millais ( , also ; 24 March 1865 – 24 March 1931) was a British artist, naturalist, gardener and travel writer who specialised in wildlife and flower portraiture. He travelled extensively around the world in the late Victorian per ...

(London, 1919)

* ''Catalogue of the Selous Collection of Big Game in the British Museum (Natural History)'' by J. G. Dollman (London, 1921)

* ''Big Game Shooting Records'' by Edgar N. Barclay (London, 1932)

* ''Frederick C. Selous, A Hunting Legend: Recollections By and About the Great Hunter'' by Dr. James A. Casada (Safari Press, 2000)

* ''The Gun at Home and Abroad, vol. 3: Big Game of Africa'' (London, 1912–1915)

* ''The African Adventurers'' by Peter Hathaway Capstick (New York: St. Martins Press, 1992), chapter 1

* ''The British Big-Game Hunting Tradition, Masculinity and Fraternalism with Particular Reference to "The Shikar Club"'' by Callum McKenzie (British Society of Sports History, May 2000)

* ''The Mighty Nimrod: A Life of Frederick Courteney Selous, African Hunter and Adventurer 1851-1917'' by Stephen Taylor (London: Collins, 1989)

See also

*Selous Scouts

The Selous Scouts was a special forces unit of the Rhodesian Army that operated during the Rhodesian Bush War from 1973 until the reconstitution of the country as Zimbabwe in 1980. It was mainly responsible for infiltrating the black majority ...

* Pioneer Column

The Pioneer Column was a force raised by Cecil Rhodes and his British South Africa Company in 1890 and used in his efforts to annex the territory of Mashonaland, later part of Zimbabwe (once Southern Rhodesia).

Background

Rhodes was anxious to ...

* Shangani Patrol

* Frederick Russell Burnham

Major (rank), Major Frederick Russell Burnham Distinguished Service Order, DSO (May 11, 1861 – September 1, 1947) was an American scout and world-traveling adventurer. He is known for his service to the British South Africa Company and to t ...

* Second Matabele War

The Second Matabele War, also known as the First Chimurenga, was fought between 1896 and 1897 in the region that later became Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). The conflict was initially between the British South Africa Company and the Mata ...

* List of famous big game hunters

References

* *Further reading

Roosevelt’s quest for wilderness: a comparison of Roosevelt’s visits to Yellowstone and Africa

*''Taps for the Great Selous'', essay by Major

Frederick Russell Burnham

Major (rank), Major Frederick Russell Burnham Distinguished Service Order, DSO (May 11, 1861 – September 1, 1947) was an American scout and world-traveling adventurer. He is known for his service to the British South Africa Company and to t ...

, D.S.O., and published in ''Hunting Trails on Three Continents,'' Grinnell, George Bird, Kermit Roosevelt

Kermit Roosevelt Sr. Military Cross, MC (October 10, 1889 – June 4, 1943) was an American businessman, soldier, explorer, and writer. A son of Theodore Roosevelt, the List of Presidents of the United States, 26th President of the United State ...

, W. Redmond Cross, and Prentiss N. Gray (editors). A Book of the Boone and Crockett Club

The Boone and Crockett Club is an American nonprofit organization that advocates fair chase hunting in support of habitat conservation. The club is North America's oldest wildlife and habitat conservation organization, founded in the United S ...

. New York: The Derrydale Press, (1933)

External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Selous, Frederick English explorers British explorers of Africa Royal Fusiliers officers British Army personnel of World War I British military personnel killed in World War I Legion of Frontiersmen members Companions of the Distinguished Service Order 1851 births 1917 deaths People of the Second Matabele War People of the First Matabele War People educated at Bruce Castle School People educated at Rugby School British hunters South African explorers Elephant hunters H. Rider Haggard Military personnel from the London Borough of Camden Military personnel from the City of Westminster