Paul-Michel Foucault ( , ; ; 15 October 192625 June 1984) was a French

historian of ideas and

philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

who was also an author,

literary critic

A genre of arts criticism, literary criticism or literary studies is the study, evaluation, and interpretation of literature. Modern literary criticism is often influenced by literary theory, which is the philosophical analysis of literature' ...

,

political activist, and teacher. Foucault's theories primarily addressed the relationships between

power versus

knowledge

Knowledge is an Declarative knowledge, awareness of facts, a Knowledge by acquaintance, familiarity with individuals and situations, or a Procedural knowledge, practical skill. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is oft ...

and

liberty

Liberty is the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority on one's way of life, behavior, or political views. The concept of liberty can vary depending on perspective and context. In the Constitutional ...

, and he analyzed how they are used as a form of

social control

Social control is the regulations, sanctions, mechanisms, and systems that restrict the behaviour of individuals in accordance with social norms and orders. Through both informal and formal means, individuals and groups exercise social con ...

through multiple institutions. Though often cited as a

structuralist and

postmodernist

Postmodernism encompasses a variety of artistic, Culture, cultural, and philosophical movements that claim to mark a break from modernism. They have in common the conviction that it is no longer possible to rely upon previous ways of depicting ...

, Foucault rejected these labels and sought to critique

authority

Authority is commonly understood as the legitimate power of a person or group of other people.

In a civil state, ''authority'' may be practiced by legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government,''The New Fontana Dictionary of M ...

without limits on himself.

His thought has influenced academics within a large number of contrasting areas of study, with this especially including those working in

anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

,

communication studies

Communication studies (or communication science) is an academic discipline that deals with processes of human communication and behavior, patterns of communication in interpersonal relationships, social interactions and communication in differ ...

,

criminology

Criminology (from Latin , 'accusation', and Ancient Greek , ''-logia'', from λόγος ''logos'', 'word, reason') is the interdisciplinary study of crime and deviant behaviour. Criminology is a multidisciplinary field in both the behaviou ...

,

cultural studies

Cultural studies is an academic field that explores the dynamics of contemporary culture (including the politics of popular culture) and its social and historical foundations. Cultural studies researchers investigate how cultural practices rel ...

,

feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

,

literary theory

Literary theory is the systematic study of the nature of literature and of the methods for literary analysis. Culler 1997, p.1 Since the 19th century, literary scholarship includes literary theory and considerations of intellectual history, m ...

,

psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

, and

sociology

Sociology is the scientific study of human society that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of Interpersonal ties, social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. The term sociol ...

. His efforts against

homophobia

Homophobia encompasses a range of negative attitudes and feelings toward homosexuality or people who identify or are perceived as being lesbian, Gay men, gay or bisexual. It has been defined as contempt, prejudice, aversion, hatred, or ant ...

and

racial prejudice as well as against other

ideological doctrines have also shaped research into

critical theory

Critical theory is a social, historical, and political school of thought and philosophical perspective which centers on analyzing and challenging systemic power relations in society, arguing that knowledge, truth, and social structures are ...

and

Marxism–Leninism

Marxism–Leninism () is a communist ideology that became the largest faction of the History of communism, communist movement in the world in the years following the October Revolution. It was the predominant ideology of most communist gov ...

alongside other topics.

Born in

Poitiers

Poitiers is a city on the river Clain in west-central France. It is a commune in France, commune, the capital of the Vienne (department), Vienne department and the historical center of Poitou, Poitou Province. In 2021, it had a population of 9 ...

, France, into an

upper-middle-class family, Foucault was educated at the

Lycée Henri-IV, at the , where he developed an interest in philosophy and came under the influence of his tutors

Jean Hyppolite and

Louis Althusser

Louis Pierre Althusser (, ; ; 16 October 1918 – 22 October 1990) was a French Marxist philosopher who studied at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, where he eventually became Professor of Philosophy.

Althusser was a long-time member an ...

, and at the

University of Paris

The University of Paris (), known Metonymy, metonymically as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, from 1150 to 1970, except for 1793–1806 during the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation associated wit ...

(

Sorbonne), where he earned degrees in philosophy and psychology. After several years as a cultural diplomat abroad, he returned to France and published his first major book, ''

The History of Madness'' (1961). After obtaining work between 1960 and 1966 at the

University of Clermont-Ferrand, he produced ''

The Birth of the Clinic'' (1963) and ''

The Order of Things

''The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences'' (''Les Mots et les Choses: Une archéologie des sciences humaines'') is a book by French philosopher Michel Foucault. It proposes that every historical period has underlying epistemi ...

'' (1966), publications that displayed his increasing involvement with structuralism, from which he later distanced himself. These first three histories exemplified a

historiographical

Historiography is the study of the methods used by historians in developing history as an academic discipline. By extension, the term ":wikt:historiography, historiography" is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiog ...

technique Foucault was developing, which he called "

archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

".

From 1966 to 1968, Foucault lectured at the

University of Tunis, before returning to France, where he became head of the philosophy department at the new experimental university of

Paris VIII. Foucault subsequently published ''

The Archaeology of Knowledge'' (1969). In 1970, Foucault was admitted to the

Collège de France, a membership he retained until his death. He also became active in several

left-wing groups involved in campaigns against racism and other violations of

human rights

Human rights are universally recognized Morality, moral principles or Social norm, norms that establish standards of human behavior and are often protected by both Municipal law, national and international laws. These rights are considered ...

, focusing on struggles such as

penal reform. Foucault later published ''

Discipline and Punish'' (1975) and ''

The History of Sexuality'' (1976), in which he developed archaeological and

genealogical methods that emphasized the role that power plays in society.

Foucault died in Paris from complications of

HIV/AIDS

The HIV, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that attacks the immune system. Without treatment, it can lead to a spectrum of conditions including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). It is a Preventive healthcare, pr ...

. He became the first

public figure

A public figure is a person who has achieved fame, prominence or notoriety within a society, whether through achievement, luck, action, or in some cases through no purposeful action of their own.

In the context of defamation actions (libel and ...

in France to die from complications of the disease, with his

charisma and

career influence changing mass awareness of the

pandemic

A pandemic ( ) is an epidemic of an infectious disease that has a sudden increase in cases and spreads across a large region, for instance multiple continents or worldwide, affecting a substantial number of individuals. Widespread endemic (epi ...

. This occurrence influenced

HIV/AIDS activism

Activism, Socio-political activism to raise awareness about HIV/AIDS as well as to advance the Management of HIV/AIDS, effective treatment and care of people with AIDS (PWAs) has taken place in multiple locations since the 1980s. The evolution o ...

; his partner,

Daniel Defert, founded the

AIDES charity in his memory. It continues to campaign as of 2024, despite the deaths of both Defert (in 2023) and Foucault (in 1984).

Early life

Early years: 1926–1938

Paul-Michel Foucault was born on 15 October 1926 in the city of

Poitiers

Poitiers is a city on the river Clain in west-central France. It is a commune in France, commune, the capital of the Vienne (department), Vienne department and the historical center of Poitou, Poitou Province. In 2021, it had a population of 9 ...

, west-central France, as the second of three children in a prosperous,

socially conservative,

upper-middle-class family. Family tradition prescribed naming him after his father, Paul Foucault (1893–1959), but his mother insisted on the addition of Michel; referred to as Paul at school, he expressed a preference for "Michel" throughout his life.

His father, a successful local surgeon born in

Fontainebleau

Fontainebleau ( , , ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Functional area (France), metropolitan area of Paris, France. It is located south-southeast of the Kilometre zero#France, centre of Paris. Fontainebleau is a Subprefectures in Franc ...

, moved to

Poitiers

Poitiers is a city on the river Clain in west-central France. It is a commune in France, commune, the capital of the Vienne (department), Vienne department and the historical center of Poitou, Poitou Province. In 2021, it had a population of 9 ...

, where he set up his own practice. He married Anne Malapert, the daughter of prosperous surgeon Prosper Malapert, who owned a private practice and taught anatomy at the University of Poitiers' School of Medicine. Paul Foucault eventually took over his father-in-law's medical practice, while Anne took charge of their large mid-19th-century house, Le Piroir, in the village of

Vendeuvre-du-Poitou. Together the couple had three children—a girl named Francine and two boys, Paul-Michel and Denys—who all shared the same fair hair and bright blue eyes. The children were raised to be nominal Catholics, attending mass at the , and while Michel briefly became an

altar boy, none of the family was devout.

In later life, Foucault revealed very little about his childhood. Describing himself as a "juvenile delinquent", he said his father was a "bully" who sternly punished him. In 1930, two years early, Foucault began his schooling at the local Lycée Henry-IV. There he undertook two years of elementary education before entering the main ''

lycée'', where he stayed until 1936. Afterwards, he took his first four years of secondary education at the same establishment, excelling in French, Greek, Latin, and history, though doing poorly at mathematics, including

arithmetic

Arithmetic is an elementary branch of mathematics that deals with numerical operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. In a wider sense, it also includes exponentiation, extraction of roots, and taking logarithms.

...

.

Teens to young adulthood: 1939–1945

In 1939, the Second World War began, followed by

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

's occupation of France in 1940. Foucault's parents opposed the occupation and the

Vichy regime, but did not join the

Resistance. That year, Foucault's mother enrolled him in the

Collège Saint-Stanislas, a strict Catholic institution run by the

Jesuits

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

. Although he later described his years there as an "ordeal", Foucault excelled academically, particularly in philosophy, history, and literature. In 1942, he entered his final year, the ''terminale'', where he focused on the study of philosophy, earning his ''

baccalauréat

The ''baccalauréat'' (; ), often known in France colloquially as the ''bac'', is a French national academic qualification that students can obtain at the completion of their secondary education (at the end of the ''lycée'') by meeting certain ...

'' in 1943.

Returning to the local Lycée Henry-IV, he studied history and philosophy for a year, aided by a personal tutor, the philosopher Louis Girard. Rejecting his father's wishes that he become a surgeon, in 1945 Foucault went to Paris, where he enrolled in one of the country's most prestigious secondary schools, which was also known as the

Lycée Henri-IV. Here he studied under the philosopher

Jean Hyppolite, an

existentialist and expert on the work of 19th-century German philosopher

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political philosophy and t ...

. Hyppolite had devoted himself to uniting existentialist theories with the

dialectical theories of Hegel and

Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

. These ideas influenced Foucault, who adopted Hyppolite's conviction that philosophy must develop through a study of history.

University studies: 1946–1951

In autumn 1946, attaining excellent results, Foucault was admitted to the élite (ENS), for which he undertook exams and an oral interrogation by

Georges Canguilhem

Georges Canguilhem (; ; 4 June 1904 – 11 September 1995) was a French philosopher and physician who specialized in epistemology and the philosophy of science (in particular, philosophy of biology, biology).

Life and work

Canguilhem entered t ...

and Pierre-Maxime Schuhl to gain entry. Of the hundred students entering the ENS, Foucault ranked fourth based on his entry results, and encountered the highly competitive nature of the institution. Like most of his classmates, he lived in the school's communal dormitories on the Parisian Rue d'Ulm.

He remained largely unpopular, spending much time alone, reading voraciously. His fellow students noted his love of violence and the macabre; he decorated his bedroom with images of torture and war drawn during the

Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

by Spanish artist

Francisco Goya

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (; ; 30 March 1746 – 16 April 1828) was a Spanish Romanticism, romantic painter and Printmaking, printmaker. He is considered the most important Spanish artist of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Hi ...

, and on one occasion chased a classmate with a dagger. Prone to

self-harm

Self-harm refers to intentional behaviors that cause harm to oneself. This is most commonly regarded as direct injury of one's own skin tissues, usually without suicidal intention. Other terms such as cutting, self-abuse, self-injury, and s ...

, Foucault allegedly

attempted suicide in 1948; his father sent him to see the psychiatrist

Jean Delay

Jean Delay (14 November 1907, Bayonne – 29 May 1987, Paris) was a French psychiatrist, neurologist, writer, and a member of the Académie française (Chair 17).

His assistant Pierre Deniker conducted a test of chlorpromazine on the male me ...

at the

Sainte-Anne Hospital Center. Obsessed with the idea of self-mutilation and suicide, Foucault attempted the latter several times in ensuing years, praising suicide in later writings. The ENS's doctor examined Foucault's state of mind, suggesting that his suicidal tendencies emerged from the distress surrounding his homosexuality, because same-sex sexual activity was socially taboo in France. At the time, Foucault engaged in homosexual activity with men whom he encountered in the underground Parisian

gay scene, also indulging in drug use; according to biographer

James Miller, he enjoyed the thrill and sense of danger that these activities offered him.

Although studying various subjects, Foucault soon gravitated towards philosophy, reading not only Hegel and Marx but also

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

,

Edmund Husserl

Edmund Gustav Albrecht Husserl (; 8 April 1859 – 27 April 1938) was an Austrian-German philosopher and mathematician who established the school of Phenomenology (philosophy), phenomenology.

In his early work, he elaborated critiques of histori ...

and most significantly,

Martin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (; 26 September 1889 – 26 May 1976) was a German philosopher known for contributions to Phenomenology (philosophy), phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. His work covers a range of topics including metaphysics, art ...

. He began reading the publications of philosopher

Gaston Bachelard, taking a particular interest in his work exploring the

history of science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient history, ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural science, natural, social science, social, and formal science, formal. Pr ...

. He graduated from the ENS with a

B.A. (licence) in Philosophy in 1948

and a ''Diplôme d'études supérieures'' (''DES''), roughly equivalent to an

M.A. degree) in

Philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

in 1949.

His DES thesis under the direction of Hyppolite was titled ''La Constitution d'un transcendental dans La Phénoménologie de l'esprit de Hegel'' (''The Constitution of a Historical Transcendental in Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit'').

In 1948, the philosopher

Louis Althusser

Louis Pierre Althusser (, ; ; 16 October 1918 – 22 October 1990) was a French Marxist philosopher who studied at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, where he eventually became Professor of Philosophy.

Althusser was a long-time member an ...

became a tutor at the ENS. A

Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

, he influenced both Foucault and a number of other students, encouraging them to join the

French Communist Party

The French Communist Party (, , PCF) is a Communism, communist list of political parties in France, party in France. The PCF is a member of the Party of the European Left, and its Member of the European Parliament, MEPs sit with The Left in the ...

. Foucault did so in 1950, but never became particularly active in its activities, and never adopted an

orthodox Marxist viewpoint, rejecting core Marxist tenets such as

class struggle. He soon became dissatisfied with the bigotry that he experienced within the party's ranks; he personally faced

homophobia

Homophobia encompasses a range of negative attitudes and feelings toward homosexuality or people who identify or are perceived as being lesbian, Gay men, gay or bisexual. It has been defined as contempt, prejudice, aversion, hatred, or ant ...

and was appalled by the

anti-semitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

exhibited during the 1952–53 "

doctors' plot" in the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. He left the Communist Party in 1953, but remained Althusser's friend and defender for the rest of his life. Although failing at the first attempt in 1950, he passed his ''

agrégation

In France, the () is the most competitive and prestigious examination for civil service in the French public education

A state school, public school, or government school is a primary school, primary or secondary school that educates all stu ...

'' in philosophy on the second try, in 1951. Excused from

national service on medical grounds, he decided to start a doctorate at the

Fondation Thiers in 1951, focusing on the philosophy of psychology, but he relinquished it after only one year in 1952.

Foucault was also interested in psychology and he attended

Daniel Lagache's lectures at the University of Paris, where he obtained a

B.A. (licence) in psychology in 1949 and a ''Specialist Diploma in

Psychopathology

Psychopathology is the study of mental illness. It includes the signs and symptoms of all mental disorders. The field includes Abnormal psychology, abnormal cognition, maladaptive behavior, and experiences which differ according to social norms ...

'' (''Diplôme de psychopathologie'') from the university's institute of psychology (now called the Institut de psychologie de l'université Paris Descartes} in June 1952.

Early career (1951–1960)

France: 1951–1955

Over the following few years, Foucault embarked on a variety of research and teaching jobs. From 1951 to 1955, he worked as a psychology instructor at the ENS at Althusser's invitation. In Paris, he shared a flat with his brother, who was training to become a surgeon, but for three days in the week commuted to the northern town of

Lille

Lille (, ; ; ; ; ) is a city in the northern part of France, within French Flanders. Positioned along the Deûle river, near France's border with Belgium, it is the capital of the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, region, the Prefectures in F ...

, teaching psychology at the

Université de Lille from 1953 to 1954. Many of his students liked his lecturing style. Meanwhile, he continued working on his thesis, visiting the

Bibliothèque Nationale every day to read the work of psychologists such as

Ivan Pavlov,

Jean Piaget

Jean William Fritz Piaget (, ; ; 9 August 1896 – 16 September 1980) was a Swiss psychologist known for his work on child development. Piaget's theory of cognitive development and epistemological view are together called genetic epistemology.

...

and

Karl Jaspers

Karl Theodor Jaspers (; ; 23 February 1883 – 26 February 1969) was a German-Swiss psychiatrist and philosopher who had a strong influence on modern theology, psychiatry, and philosophy. His 1913 work ''General Psychopathology'' influenced many ...

. Undertaking research at the psychiatric institute of the Sainte-Anne Hospital, he became an unofficial intern, studying the relationship between doctor and patient and aiding experiments in the

electroencephalographic laboratory. Foucault adopted many of the theories of the psychoanalyst

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( ; ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating psychopathology, pathologies seen as originating fro ...

, undertaking psychoanalytical interpretation of his dreams and making friends undergo

Rorschach tests.

Embracing the Parisian

avant-garde

In the arts and literature, the term ''avant-garde'' ( meaning or ) identifies an experimental genre or work of art, and the artist who created it, which usually is aesthetically innovative, whilst initially being ideologically unacceptable ...

, Foucault entered into a romantic relationship with the

serialist composer

Jean Barraqué. Together, they tried to produce their greatest work, heavily used recreational drugs and engaged in

sado-masochistic sexual activity. In August 1953, Foucault and Barraqué holidayed in Italy, where the philosopher immersed himself in ''

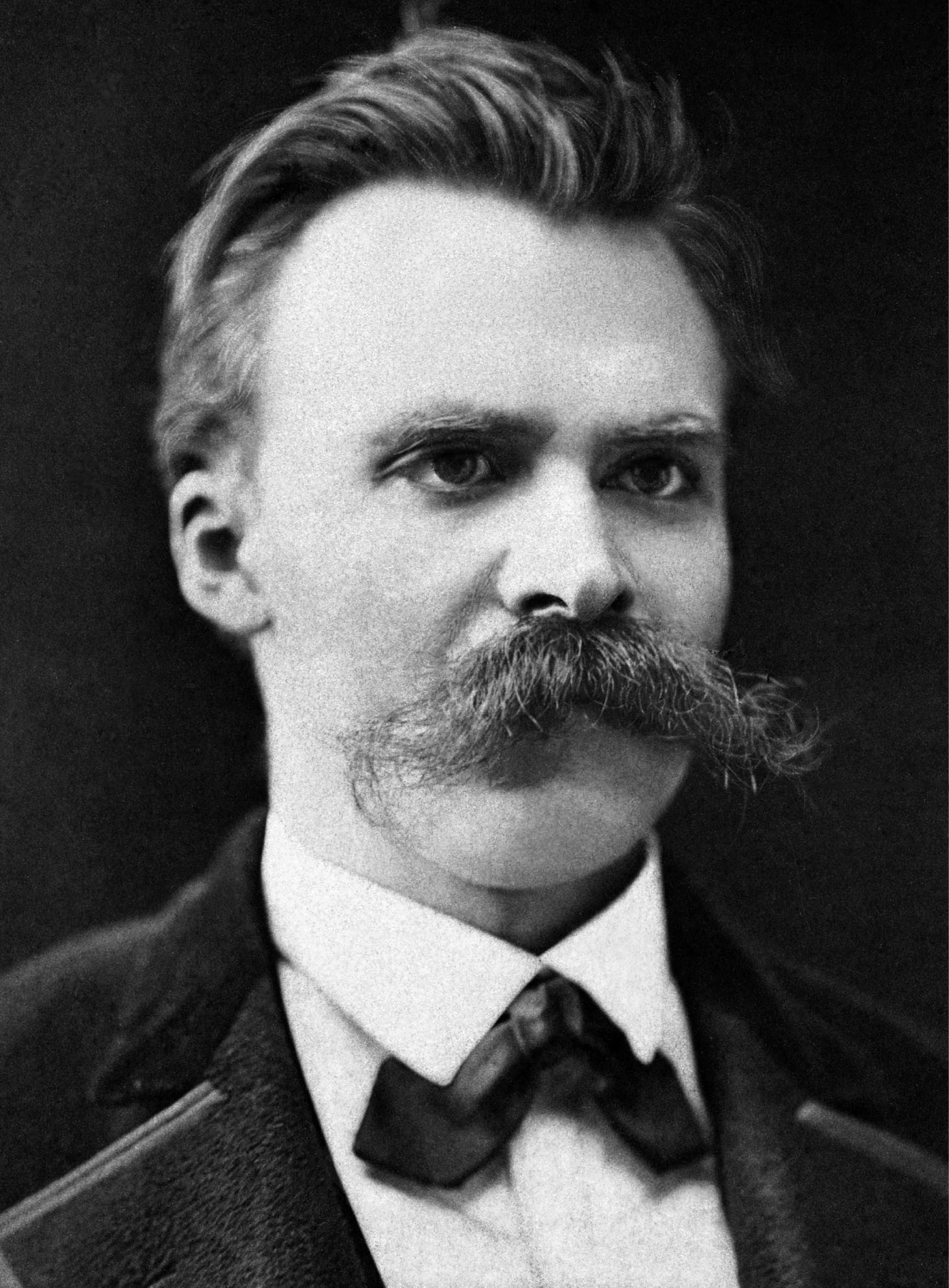

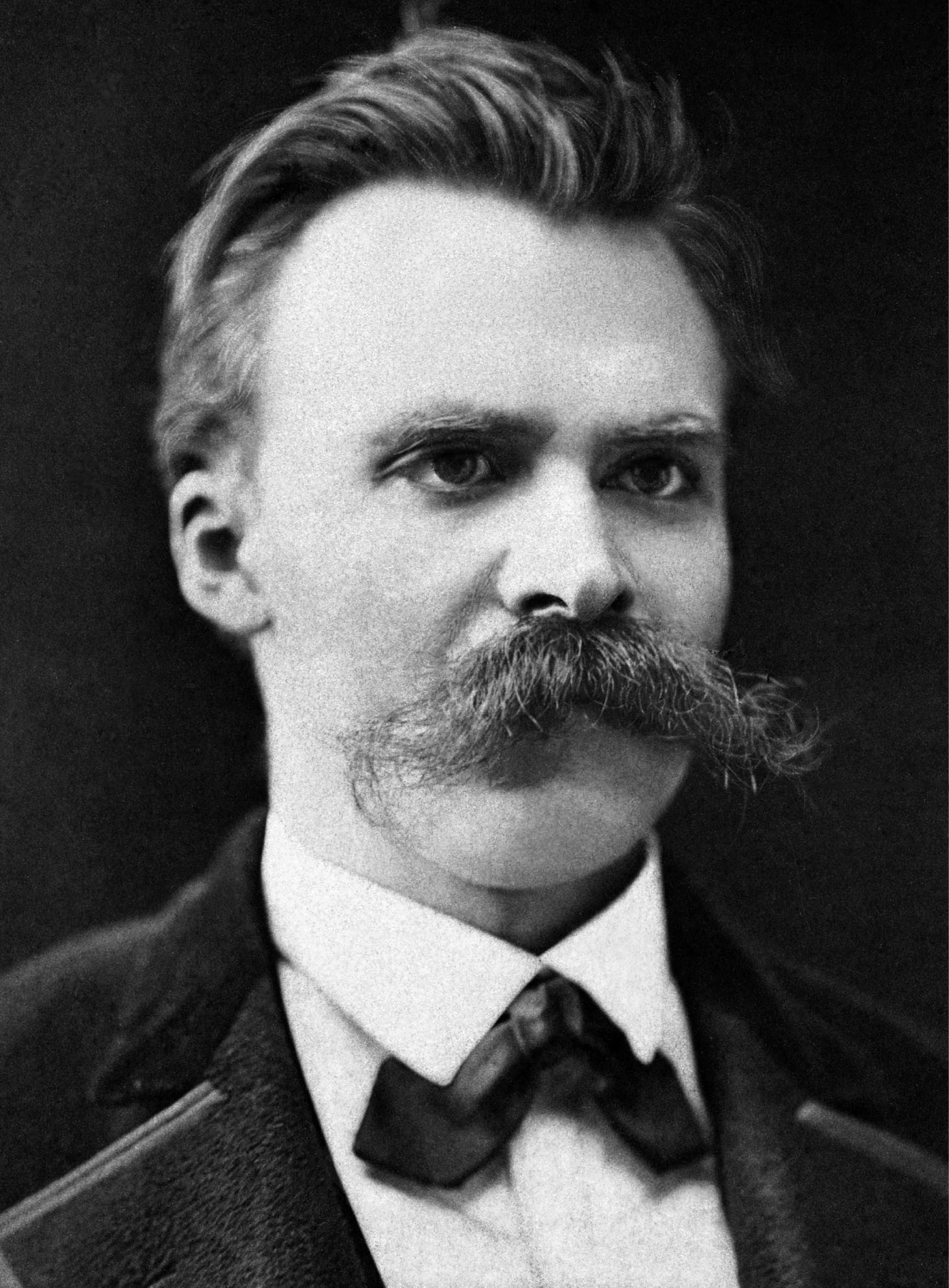

Untimely Meditations'' (1873–1876), a set of four essays by the philosopher

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philology, classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche bec ...

. Later describing Nietzsche's work as "a revelation", he felt that reading the book deeply affected him, being a watershed moment in his life. Foucault subsequently experienced another groundbreaking self-revelation when watching a Parisian performance of

Samuel Beckett

Samuel Barclay Beckett (; 13 April 1906 – 22 December 1989) was an Irish writer of novels, plays, short stories, and poems. Writing in both English and French, his literary and theatrical work features bleak, impersonal, and Tragicomedy, tra ...

's new play, ''

Waiting for Godot'', in 1953.

Interested in literature, Foucault was an avid reader of the philosopher

Maurice Blanchot's book reviews published in ''

Nouvelle Revue Française

''La Nouvelle Revue Française'' (; "The New French Review") is a literary magazine based in France. In France, it is often referred to as the ''NRF''.

History and profile

The magazine was founded in 1909 by a group of intellectuals including And ...

''. Enamoured of Blanchot's literary style and critical theories, in later works he adopted Blanchot's technique of "interviewing" himself. Foucault also came across

Hermann Broch's 1945 novel ''

The Death of Virgil'', a work that obsessed both him and Barraqué. While the latter attempted to convert the work into an

epic opera, Foucault admired Broch's text for its portrayal of death as an affirmation of life. The couple took a mutual interest in the work of such authors as the

Marquis de Sade,

Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist and journalist. He is regarded as one of the greatest novelists in both Russian literature, Russian and world literature, and many of his works are consider ...

,

Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka (3 July 1883 – 3 June 1924) was a novelist and writer from Prague who was Jewish, Austrian, and Czech and wrote in German. He is widely regarded as a major figure of 20th-century literature. His work fuses elements of Litera ...

and

Jean Genet, all of whose works explored the themes of sex and violence.

Interested in the work of Swiss psychologist

Ludwig Binswanger

Ludwig Binswanger (; ; 13 April 1881 – 5 February 1966) was a Swiss people, Swiss psychiatrist and pioneer in the field of existential psychology. His parents were Robert Johann Binswanger (1850–1910) and Bertha Hasenclever (1847–1896). ...

, Foucault aided family friend Jacqueline Verdeaux in translating his works into French. Foucault was particularly interested in Binswanger's studies of

Ellen West

Ellen West (1888–1921) was a patient of Dr. Ludwig Binswanger who had anorexia nervosa. She became a famous example of Daseinsanalysis who died by suicide at age 33 by poisoning herself.

Life

Ellen West was born to a Jewish family in 1888. When ...

who, like himself, had a deep obsession with suicide, eventually killing herself. In 1954, Foucault authored an introduction to Binswanger's paper "Dream and Existence", in which he argued that dreams constituted "the birth of the world" or "the heart laid bare", expressing the mind's deepest desires. That same year, Foucault published his first book, ''Maladie mentale et personalité'' (''Mental Illness and Personality''), in which he exhibited his influence from both Marxist and Heideggerian thought, covering a wide range of subject matter from the reflex psychology of Pavlov to the classic psychoanalysis of Freud. Referencing the work of

sociologists

This list of sociologists includes people who have made notable contributions to sociological theory or to research in one or more areas of sociology.

A

* Peter Abell, British sociologist

* Andrew Abbott, American sociologist

* Margaret ...

and anthropologists such as

Émile Durkheim

David Émile Durkheim (; or ; 15 April 1858 – 15 November 1917) was a French Sociology, sociologist. Durkheim formally established the academic discipline of sociology and is commonly cited as one of the principal architects of modern soci ...

and

Margaret Mead, he presented his theory that illness was culturally relative. Biographer

James Miller noted that while the book exhibited "erudition and evident intelligence", it lacked the "kind of fire and flair" that Foucault exhibited in subsequent works. It was largely critically ignored, receiving only one review at the time. Foucault grew to despise it, unsuccessfully attempting to prevent its republication and translation into English.

Sweden, Poland, and West Germany: 1955–1960

Foucault spent the next five years abroad, first in Sweden, working as cultural diplomat at the

University of Uppsala

Uppsala University (UU) () is a public research university in Uppsala, Sweden. Founded in 1477, it is the oldest university in Sweden and the Nordic countries still in operation.

Initially founded in the 15th century, the university rose to s ...

, a job obtained through his acquaintance with historian of religion

Georges Dumézil. At

Uppsala

Uppsala ( ; ; archaically spelled ''Upsala'') is the capital of Uppsala County and the List of urban areas in Sweden by population, fourth-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmö. It had 177,074 inhabitants in 2019.

Loc ...

, he was appointed a Reader in French language and literature, while simultaneously working as director of the Maison de France, thus opening the possibility of a cultural-diplomatic career. Although finding it difficult to adjust to the "Nordic gloom" and long winters, he developed close friendships with two Frenchmen, biochemist Jean-François Miquel and physicist Jacques Papet-Lépine, and entered into romantic and sexual relationships with various men. In Uppsala he became known for his heavy alcohol consumption and reckless driving in his new

Jaguar car. In spring 1956, Barraqué broke from his relationship with Foucault, announcing that he wanted to leave the "vertigo of madness". In Uppsala, Foucault spent much of his spare time in the university's

Carolina Rediviva library, making use of their Bibliotheca Walleriana collection of texts on the history of medicine for his ongoing research. Finishing his doctoral thesis, Foucault hoped that Uppsala University would accept it, but

Sten Lindroth, a

positivistic historian of science there, remained unimpressed, asserting that it was full of speculative generalisations and was a poor work of history; he refused to allow Foucault to be awarded a doctorate at Uppsala. In part because of this rejection, Foucault left Sweden. Later, Foucault admitted that the work was a first draft with certain lack of quality.

Again at Dumézil's behest, in October 1958 Foucault arrived in

Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

, the capital of the

Polish People's Republic

The Polish People's Republic (1952–1989), formerly the Republic of Poland (1947–1952), and also often simply known as Poland, was a country in Central Europe that existed as the predecessor of the modern-day democratic Republic of Poland. ...

, and took charge of the

University of Warsaw's Centre Français. Foucault found life in Poland difficult due to the lack of material goods and services following the destruction of the Second World War. Witnessing the aftermath of the

Polish October of 1956, when students had protested against the governing communist

Polish United Workers' Party, he felt that most Poles despised their government as a

puppet regime of the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, and thought that the system ran "badly". Considering the university a liberal enclave, he traveled the country giving lectures; proving popular, he adopted the position of ''de facto'' cultural attaché. Like France and Sweden, Poland legally tolerated but socially frowned on homosexual activity, and Foucault undertook relationships with a number of men; one was with a Polish security agent who hoped to trap Foucault in an embarrassing situation, which therefore would reflect badly on the French embassy. Wracked in diplomatic scandal, he was ordered to leave Poland for a new destination. Various positions were available in

West Germany

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republi ...

, and so Foucault relocated to the Institut français Hamburg (where he served as director in 1958–1960), teaching the same courses he had given in Uppsala and Warsaw.

Spending much time in the

Reeperbahn red-light district, he entered into a relationship with a

transvestite.

Growing career (1960–1970)

''Madness and Civilization'': 1960

In West Germany, Foucault completed in 1960 his primary thesis (''thèse principale'') for his

State doctorate, titled ''

Folie et déraison: Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique'' (trans. "Madness and Insanity: History of Madness in the Classical Age"), a philosophical work based upon his studies into the

history of medicine

The history of medicine is both a study of medicine throughout history as well as a multidisciplinary field of study that seeks to explore and understand medical practices, both past and present, throughout human societies.

The history of med ...

. The book discussed how West European society had dealt with

madness, arguing that it was a social construct distinct from

mental illness. Foucault traces the evolution of the concept of madness through three phases: the

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

, the later 17th and 18th centuries, and the modern experience. The work alludes to the work of French poet and playwright

Antonin Artaud

Antoine Maria Joseph Paul Artaud (; ; 4September 18964March 1948), better known as Antonin Artaud, was a French artist who worked across a variety of media. He is best known for his writings, as well as his work in the theatre and cinema. Widely ...

, who exerted a strong influence over Foucault's thought at the time.

''Histoire de la folie'' was an expansive work, consisting of 943 pages of text, followed by appendices and a bibliography. Foucault submitted it at the

University of Paris

The University of Paris (), known Metonymy, metonymically as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, from 1150 to 1970, except for 1793–1806 during the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation associated wit ...

, although the university's regulations for awarding a State doctorate required the submission of both his main thesis and a shorter complementary thesis. Obtaining a doctorate in France at the period was a multi-step process. The first step was to obtain a ''rapporteur'', or "sponsor" for the work: Foucault chose

Georges Canguilhem

Georges Canguilhem (; ; 4 June 1904 – 11 September 1995) was a French philosopher and physician who specialized in epistemology and the philosophy of science (in particular, philosophy of biology, biology).

Life and work

Canguilhem entered t ...

. The second was to find a publisher, and as a result ''Folie et déraison'' was published in French in May 1961 by the company

Plon, whom Foucault chose over

Presses Universitaires de France

Presses universitaires de France (PUF; ), founded in 1921 by Paul Angoulvent (1899–1976), is a French publishing house.

Recent company history

The financial and legal structure of the Presses Universitaires de France was completely restruc ...

after being rejected by

Gallimard. In 1964, a heavily abridged version was published as a mass market paperback, then translated into English for publication the following year as ''Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason''.

''Folie et déraison'' received a mixed reception in France and in foreign journals focusing on French affairs. Although it was critically acclaimed by

Maurice Blanchot,

Michel Serres,

Roland Barthes

Roland Gérard Barthes (; ; 12 November 1915 – 25 March 1980) was a French literary theorist, essayist, philosopher, critic, and semiotician. His work engaged in the analysis of a variety of sign systems, mainly derived from Western popu ...

,

Gaston Bachelard, and

Fernand Braudel, it was largely ignored by the leftist press, much to Foucault's disappointment. It was notably criticised for advocating

metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

by young philosopher

Jacques Derrida

Jacques Derrida (; ; born Jackie Élie Derrida;Peeters (2013), pp. 12–13. See also 15 July 1930 – 9 October 2004) was a French Algerian philosopher. He developed the philosophy of deconstruction, which he utilized in a number of his texts, ...

in a

March 1963 lecture at the

University of Paris

The University of Paris (), known Metonymy, metonymically as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, from 1150 to 1970, except for 1793–1806 during the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation associated wit ...

. Responding with a vicious retort, Foucault criticised Derrida's interpretation of

René Descartes

René Descartes ( , ; ; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and Modern science, science. Mathematics was paramou ...

. The two remained bitter rivals until reconciling in 1981. In the English-speaking world, the work became a significant influence on the

anti-psychiatry movement during the 1960s; Foucault took a mixed approach to this, associating with a number of anti-psychiatrists but arguing that most of them misunderstood his work.

Foucault's secondary thesis (), written in Hamburg between 1959 and 1960, was a translation and commentary on German philosopher

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

's ''Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View'' (1798);

the thesis was titled ''

Introduction à l'Anthropologie''. Largely consisting of Foucault's discussion of textual dating—an "archaeology of the Kantian text"—he rounded off the thesis with an evocation of Nietzsche, his biggest philosophical influence. This work's ''rapporteur'' was Foucault's old tutor and then-director of the ENS, Hyppolite, who was well acquainted with German philosophy. After both theses were championed and reviewed, he underwent his public defense of his

doctoral thesis

A thesis (: theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: D ...

(''soutenance de thèse'') on 20 May 1961. The academics responsible for reviewing his work were concerned about the unconventional nature of his major thesis; reviewer

Henri Gouhier noted that it was not a conventional work of history, making sweeping generalisations without sufficient particular argument, and that Foucault clearly "thinks in allegories". They all agreed however that the overall project was of merit, awarding Foucault his doctorate "despite reservations".

University of Clermont-Ferrand, ''The Birth of the Clinic'', and ''The Order of Things'': 1960–1966

In October 1960, Foucault took a tenured post in philosophy at the

University of Clermont-Ferrand, commuting to the city every week from Paris, where he lived in a high-rise block on the rue du Dr Finlay. Responsible for teaching psychology, which was subsumed within the philosophy department, he was considered a "fascinating" but "rather traditional" teacher at Clermont. The department was run by

Jules Vuillemin, who soon developed a friendship with Foucault. Foucault then took Vuillemin's job when the latter was elected to the

Collège de France in 1962. In this position, Foucault took a dislike to another staff member whom he considered stupid:

Roger Garaudy, a senior figure in the Communist Party. Foucault made life at the university difficult for Garaudy, leading the latter to transfer to Poitiers. Foucault also caused controversy by securing a university job for his lover, the philosopher

Daniel Defert, with whom he retained a non-monogamous relationship for the rest of his life.

Foucault maintained a keen interest in literature, publishing reviews in literary journals, including ''

Tel Quel'' and ''

Nouvelle Revue Française

''La Nouvelle Revue Française'' (; "The New French Review") is a literary magazine based in France. In France, it is often referred to as the ''NRF''.

History and profile

The magazine was founded in 1909 by a group of intellectuals including And ...

'', and sitting on the editorial board of ''

Critique

Critique is a method of disciplined, systematic study of a written or oral discourse. Although critique is frequently understood as fault finding and negative judgment, Rodolphe Gasché (2007''The honor of thinking: critique, theory, philosophy ...

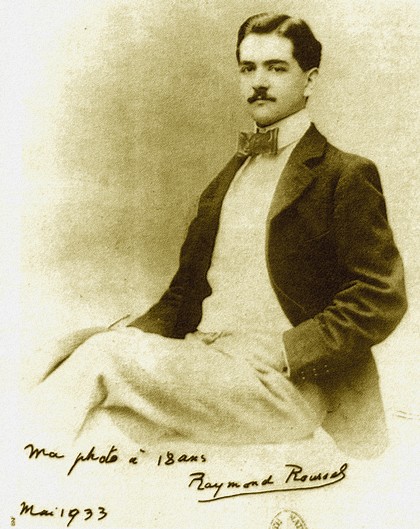

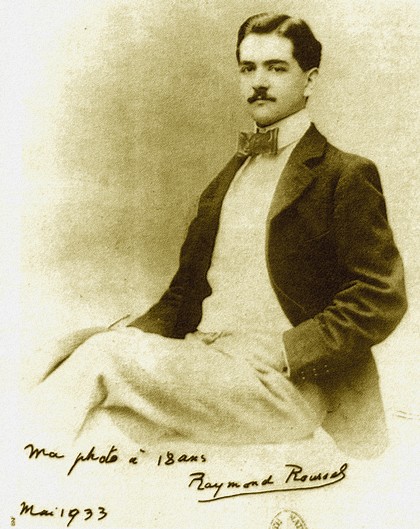

'', In May 1963, he published a book devoted to poet, novelist, and playwright

Raymond Roussel. It was written in under two months, published by Gallimard, and was described by biographer

David Macey as "a very personal book" that resulted from a "love affair" with Roussel's work. It was published in English in 1983 as ''Death and the Labyrinth: The World of Raymond Roussel''. Receiving few reviews, it was largely ignored. That same year he published a sequel to ''Folie et déraison'', titled ''Naissance de la Clinique'', subsequently translated as ''

The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception''. Shorter than its predecessor, it focused on the changes that the medical establishment underwent in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Like his preceding work, ''Naissance de la Clinique'' was largely critically ignored, but later gained a cult following. It was of interest within the field of

medical ethics

Medical ethics is an applied branch of ethics which analyzes the practice of clinical medicine and related scientific research. Medical ethics is based on a set of values that professionals can refer to in the case of any confusion or conflict. T ...

, as it considered the ways in which the history of medicine and hospitals, and the training that those working within them receive, bring about a particular way of looking at the body: the 'medical

gaze

In critical theory, philosophy, sociology, and psychoanalysis, the gaze (French: ''le regard''), in the figurative sense, is an individual's (or a group's) awareness and perception of other individuals, other groups, or oneself. Since the 20th ...

'. Foucault was also selected to be among the "Eighteen Man Commission" that assembled between November 1963 and March 1964 to discuss university reforms that were to be implemented by

Christian Fouchet, the Gaullist

Minister of National Education. Implemented in 1967, they brought staff strikes and student protests.

In April 1966, Gallimard published Foucault's ' (Words and Things), later translated as ''

The Order of Things

''The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences'' (''Les Mots et les Choses: Une archéologie des sciences humaines'') is a book by French philosopher Michel Foucault. It proposes that every historical period has underlying epistemi ...

: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences''. Exploring how man came to be an object of knowledge, it argued that all periods of history have possessed certain underlying conditions of truth that constituted what was acceptable as scientific discourse. Foucault argues that these conditions of discourse have changed over time, from one period's ''

épistémè'' to another. Although designed for a specialist audience, the work gained media attention, becoming a surprise bestseller in France. Appearing at the height of interest in

structuralism

Structuralism is an intellectual current and methodological approach, primarily in the social sciences, that interprets elements of human culture by way of their relationship to a broader system. It works to uncover the structural patterns t ...

, Foucault was quickly grouped with scholars such as

Jacques Lacan

Jacques Marie Émile Lacan (, ; ; 13 April 1901 – 9 September 1981) was a French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist. Described as "the most controversial psycho-analyst since Sigmund Freud, Freud", Lacan gave The Seminars of Jacques Lacan, year ...

,

Claude Lévi-Strauss

Claude Lévi-Strauss ( ; ; 28 November 1908 – 30 October 2009) was a Belgian-born French anthropologist and ethnologist whose work was key in the development of the theories of structuralism and structural anthropology. He held the chair o ...

, and

Roland Barthes

Roland Gérard Barthes (; ; 12 November 1915 – 25 March 1980) was a French literary theorist, essayist, philosopher, critic, and semiotician. His work engaged in the analysis of a variety of sign systems, mainly derived from Western popu ...

, as the latest wave of thinkers set to topple the

existentialism popularized by

Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was a French philosopher, playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and literary criticism, literary critic, considered a leading figure in 20th ...

. Although initially accepting this description, Foucault soon vehemently rejected it, because he "never posited a universal theory of discourse, but rather sought to describe the historical forms taken by discoursive practices". Foucault and Sartre regularly criticised one another in the press. Both Sartre and

Simone de Beauvoir attacked Foucault's ideas as "

bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and Aristocracy (class), aristocracy. They are tradition ...

", while Foucault retaliated against their Marxist beliefs by proclaiming that "Marxism exists in nineteenth-century thought as a fish exists in water; that is, it ceases to breathe anywhere else."

University of Tunis and Vincennes: 1966–1970

In September 1966, Foucault took a position teaching psychology at the

University of Tunis in Tunisia. His decision to do so was largely because his lover, Defert, had been posted to the country as part of his

national service. Foucault moved a few kilometres from

Tunis

Tunis (, ') is the capital city, capital and largest city of Tunisia. The greater metropolitan area of Tunis, often referred to as "Grand Tunis", has about 2,700,000 inhabitants. , it is the third-largest city in the Maghreb region (after Casabl ...

, to the village of

Sidi Bou Saïd, where fellow academic Gérard Deledalle lived with his wife. Soon after his arrival, Foucault announced that Tunisia was "blessed by history", a nation which "deserves to live forever because it was where

Hannibal

Hannibal (; ; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Punic people, Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Ancient Carthage, Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Punic War.

Hannibal's fat ...

and

St. Augustine lived". His lectures at the university proved very popular, and were well attended. Although many young students were enthusiastic about his teaching, they were critical of what they believed to be his right-wing political views, viewing him as a "representative of Gaullist technocracy", even though he considered himself a leftist.

Foucault was in Tunis during the anti-government and pro-Palestinian riots that rocked the city in June 1967, and which continued for a year. Although highly critical of the violent, ultra-nationalistic and anti-semitic nature of many protesters, he used his status to try to prevent some of his militant leftist students from being arrested and tortured for their role in the agitation. He hid their printing press in his garden, and tried to testify on their behalf at their trials, but was prevented when the trials became closed-door events. While in Tunis, Foucault continued to write. Inspired by a correspondence with the surrealist artist

René Magritte

René François Ghislain Magritte (; 21 November 1898 – 15 August 1967) was a Belgium, Belgian surrealist artist known for his depictions of familiar objects in unfamiliar, unexpected contexts, which often provoked questions about the nature ...

, Foucault started to write a book about the

impressionist artist

Édouard Manet

Édouard Manet (, ; ; 23 January 1832 – 30 April 1883) was a French Modernism, modernist painter. He was one of the first 19th-century artists to paint modern life, as well as a pivotal figure in the transition from Realism (art movement), R ...

, but never completed it.

In 1968, Foucault returned to Paris, moving into an apartment on the Rue de Vaugirard. After the May 1968 student protests, Minister of Education

Edgar Faure responded by founding new universities with greater autonomy. Most prominent of these was the

Centre Expérimental de Vincennes in

Vincennes on the outskirts of Paris. A group of prominent academics were asked to select teachers to run the centre's departments, and Canguilheim recommended Foucault as head of the Philosophy Department. Becoming a tenured professor of Vincennes, Foucault's desire was to obtain "the best in French philosophy today" for his department, employing

Michel Serres,

Judith Miller,

Alain Badiou

Alain Badiou (; ; born 17 January 1937) is a French philosopher, formerly chair of Philosophy at the École normale supérieure (ENS) and founder of the faculty of Philosophy of the Université de Paris VIII with Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucault ...

,

Jacques Rancière,

François Regnault,

Henri Weber,

Étienne Balibar

Étienne Balibar (; ; born 23 April 1942) is a French philosopher. He has taught at the University of Paris X, at the University of California, Irvine and is currently an Anniversary Chair Professor at the Centre for Research in Modern European ...

, and

François Châtelet; most of them were Marxists or ultra-left activists.

Lectures began at the university in January 1969, and straight away its students and staff, including Foucault, were involved in occupations and clashes with police, resulting in arrests. In February, Foucault gave a speech denouncing police provocation to protesters at the

Maison de la Mutualité. Such actions marked Foucault's embrace of the ultra-left, undoubtedly influenced by Defert, who had gained a job at Vincennes' sociology department and who had become a

Maoist. Most of the courses at Foucault's philosophy department were

Marxist–Leninist oriented, although Foucault himself gave courses on Nietzsche, "The end of Metaphysics", and "The Discourse of Sexuality", which were highly popular and over-subscribed. While the right-wing press was heavily critical of this new institution, new Minister of Education

Olivier Guichard was angered by its ideological bent and the lack of exams, with students being awarded degrees in a haphazard manner. He refused national accreditation of the department's degrees, resulting in a public rebuttal from Foucault.

Later life (1970–1984)

Collège de France and ''Discipline and Punish'': 1970–1975

Foucault desired to leave Vincennes and become a fellow of the prestigious

Collège de France. He requested to join, taking up a chair in what he called the "history of systems of thought", and his request was championed by members Dumézil, Hyppolite, and Vuillemin. In November 1969, when an opening became available, Foucault was elected to the Collège, though with opposition by a large minority. He gave his inaugural lecture in December 1970, which was subsequently published as ''L'Ordre du discours'' (''The Discourse of Language''). He was obliged to give 12 weekly lectures a year—and did so for the rest of his life—covering the topics that he was researching at the time; these became "one of the events of Parisian intellectual life" and were repeatedly packed out events. On Mondays, he also gave seminars to a group of students; many of them became a "Foulcauldian tribe" who worked with him on his research. He enjoyed this teamwork and collective research, and together they published a number of short books. Working at the Collège allowed him to travel widely, giving lectures in Brazil, Japan, Canada, and the United States over the next 14 years. In 1970 and 1972, Foucault served as a professor in the French Department of the

University at Buffalo

The State University of New York at Buffalo (commonly referred to as UB, University at Buffalo, and sometimes SUNY Buffalo) is a public university, public research university in Buffalo, New York, Buffalo and Amherst, New York, United States. ...

in Buffalo, New York.

In May 1971, Foucault co-founded the Groupe d'Information sur les Prisons (GIP) along with historian

Pierre Vidal-Naquet and journalist

Jean-Marie Domenach. The GIP aimed to investigate and expose poor conditions in prisons and give prisoners and ex-prisoners a voice in French society. It was highly critical of the penal system, believing that it converted petty criminals into hardened delinquents. The GIP gave press conferences and staged protests surrounding the events of the Toul prison riot in December 1971, alongside other prison riots that it sparked off; in doing so it faced a police crackdown and repeated arrests. The group became active across France, with 2,000 to 3,000, members, but disbanded before 1974. Also campaigning against the death penalty, Foucault co-authored a short book on the case of the convicted murderer Pierre Rivière. After his research into the penal system, Foucault published ''Surveiller et punir: Naissance de la prison'' (''

Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison'') in 1975, offering a history of the system in western Europe. In it, Foucault examines the penal evolution away from corporal and capital punishment to the penitentiary system that began in Europe and the United States around the end of the 18th century. Biographer

Didier Eribon described it as "perhaps the finest" of Foucault's works, and it was well received.

Foucault was also active in

anti-racist campaigns; in November 1971, he was a leading figure in protests following the perceived racist killing of Arab migrant Djellali Ben Ali. In this he worked alongside his old rival Sartre, the journalist

Claude Mauriac, and one of his literary heroes, Jean Genet. This campaign was formalised as the Committee for the Defence of the Rights of Immigrants, but there was tension at their meetings as Foucault opposed the anti-Israeli sentiment of many Arab workers and Maoist activists. At a December 1972 protest against the police killing of Algerian worker Mohammad Diab, both Foucault and Genet were arrested, resulting in widespread publicity. Foucault was also involved in founding the Agence de Press-Libération (APL), a group of leftist journalists who intended to cover news stories neglected by the mainstream press. In 1973, they established the daily newspaper ''

Libération

(), popularly known as ''Libé'' (), is a daily newspaper in France, founded in Paris by Jean-Paul Sartre and Serge July in 1973 in the wake of the protest movements of May 1968 in France, May 1968. Initially positioned on the far left of Fr ...

'', and Foucault suggested that they establish committees across France to collect news and distribute the paper, and advocated a column known as the "Chronicle of the Workers' Memory" to allow workers to express their opinions. Foucault wanted an active journalistic role in the paper, but this proved untenable, and he soon became disillusioned with ''Libération'', believing that it distorted the facts; he did not publish in it until 1980.

In 1975 he had an

LSD experience with Simeon Wade and Michael Stoneman in

Death Valley

Death Valley is a desert valley in Eastern California, in the northern Mojave Desert, bordering the Great Basin Desert. It is thought to be the Highest temperature recorded on Earth, hottest place on Earth during summer.

Death Valley's Badwat ...

, California, and later wrote "it was the greatest experience of his life, and that it profoundly changed his life and his work". In front of

Zabriskie Point they took LSD while listening to a well-prepared music program:

Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss (; ; 11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was a German composer and conductor best known for his Tone poems (Strauss), tone poems and List of operas by Richard Strauss, operas. Considered a leading composer of the late Roman ...

's ''

Four Last Songs'', followed by

Charles Ives

Charles Edward Ives (; October 20, 1874May 19, 1954) was an American modernist composer, actuary and businessman. Ives was among the earliest renowned American composers to achieve recognition on a global scale. His music was largely ignored d ...

's ''

Three Places in New England'', ending with a few avant-garde pieces by

Stockhausen. According to Wade, as soon as he came back to Paris, Foucault scrapped the second ''The History of Sexuality''s manuscript, and totally rethought the whole project.

''The History of Sexuality'' and Iranian Revolution: 1976–1979

In 1976, Gallimard published Foucault's ''

Histoire de la sexualité: la volonté de savoir'' (''The History of Sexuality: The Will to Knowledge''), a short book exploring what Foucault called the "repressive hypothesis". It revolved largely around the concept of power, rejecting both Marxist and Freudian theory. Foucault intended it as the first in a seven-volume exploration of the subject. ''Histoire de la sexualité'' was a best-seller in France and gained positive press, but lukewarm intellectual interest, something that upset Foucault, who felt that many misunderstood his hypothesis. He soon became dissatisfied with Gallimard after being offended by senior staff member

Pierre Nora. Along with

Paul Veyne and

François Wahl, Foucault launched a new series of academic books, known as ''Des travaux'' (''Some Works''), through the company

Seuil, which he hoped would improve the state of academic research in France. He also produced introductions for the memoirs of

Herculine Barbin and ''

My Secret Life''.

Foucault's ''Histoire de la sexualité'' concentrates on the relation between truth and sex.

He defines truth as a system of ordered procedures for the production, distribution, regulation, circulation, and operation of statements. Through this system of truth, power structures are created and enforced. Though Foucault's definition of truth may differ from other sociologists before and after him, his work with truth in relation to power structures, such as sexuality, has left a profound mark on social science theory. In his work, he examines the heightened curiosity regarding sexuality that induced a "world of perversion" during the elite, capitalist 18th and 19th century in the western world. According to Foucault in ''History of Sexuality'', society of the modern age is symbolized by the conception of sexual discourses and their union with the system of truth.

In the "world of perversion", including extramarital affairs, homosexual behavior, and other such sexual promiscuities, Foucault concludes that sexual relations of the kind are constructed around producing the truth.

Sex became not only a means of pleasure, but an issue of truth.

Sex is what confines one to darkness, but also what brings one to light.

Similarly, in ''The History of Sexuality'', society validates and approves people based on how closely they fit the discursive mold of sexual truth.

As Foucault reminds us, in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Church was the epitome of power structure within society. Thus, many aligned their personal virtues with those of the Church, further internalizing their beliefs on the meaning of sex.

However, those who unify their sexual relation to the truth become decreasingly obliged to share their internal views with those of the Church. They will no longer see the arrangement of societal norms as an effect of the Church's deep-seated power structure.

Foucault remained a political activist, focusing on protesting government abuses of human rights around the world. He was a key player in the 1975 protests against the Spanish government who were set to execute 11 militants sentenced to death without fair trial. It was his idea to travel to

Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

with six others to give a press conference there; they were subsequently arrested and deported back to Paris. In 1977, he protested the extradition of

Klaus Croissant to West Germany, and his rib was fractured during clashes with riot police. In July that year, he organised an assembly of

Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

dissidents to mark the visit of

Soviet general secretary Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (19 December 190610 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until Death and state funeral of Leonid Brezhnev, his death in 1982 as w ...

to Paris. In 1979, he campaigned for Vietnamese political dissidents to be granted asylum in France.

In 1977, Italian newspaper ''

Corriere della sera'' asked Foucault to write a column for them. In doing so, in 1978 he travelled to

Tehran

Tehran (; , ''Tehrân'') is the capital and largest city of Iran. It is the capital of Tehran province, and the administrative center for Tehran County and its Central District (Tehran County), Central District. With a population of around 9. ...

in Iran, days after the

Black Friday massacre. Documenting the developing

Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution (, ), also known as the 1979 Revolution, or the Islamic Revolution of 1979 (, ) was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynasty in 1979. The revolution led to the replacement of the Impe ...

, he met with opposition leaders such as

Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari and

Mehdi Bazargan

Mehdi Bazargan (; 1 September 1907 – 20 January 1995) was an Iranian scholar, academic, long-time pro-democracy activist and head of Interim government of Iran, 1979, Iran's interim government.

One of the leading figures of Iranian Revolutio ...

, and discovered the popular support for

Islamism

Islamism is a range of religious and political ideological movements that believe that Islam should influence political systems. Its proponents believe Islam is innately political, and that Islam as a political system is superior to communism ...

. Returning to France, he was one of the journalists who visited the

Ayatollah Khomeini, before visiting Tehran. His articles expressed awe of Khomeini's Islamist movement, for which he was widely criticised in the French press, including by Iranian expatriates. Foucault's response was that Islamism was to become a major political force in the region, and that the West must treat it with respect rather than hostility. In April 1978, Foucault traveled to Japan, where he studied

Zen Buddhism

Zen (; from Chinese: '' Chán''; in Korean: ''Sŏn'', and Vietnamese: ''Thiền'') is a Mahayana Buddhist tradition that developed in China during the Tang dynasty by blending Indian Mahayana Buddhism, particularly Yogacara and Madhyamaka ph ...

under

Omori Sogen at the Seionji temple in

Uenohara.

Final years: 1980–1984

Although remaining critical of power relations, Foucault expressed cautious support for the

Socialist Party government of

François Mitterrand following its

electoral victory in 1981. But his support soon deteriorated when that party refused to condemn the Polish government's crackdown on the

1982 demonstrations in Poland orchestrated by the

Solidarity

Solidarity or solidarism is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. True solidarity means moving beyond individual identities and single issue politics ...

trade union. He and sociologist

Pierre Bourdieu

Pierre Bourdieu (, ; ; ; 1 August 1930 – 23 January 2002) was a French sociologist and public intellectual. Bourdieu's contributions to the sociology of education, the theory of sociology, and sociology of aesthetics have achieved wide influ ...

authored a document condemning Mitterrand's inaction that was published in ''Libération'', and they also took part in large public protests on the issue. Foucault continued to support Solidarity, and with his friend

Simone Signoret traveled to Poland as part of a

Médecins du Monde expedition, taking time out to visit the

Auschwitz concentration camp

Auschwitz, or Oświęcim, was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) d ...

. He continued his academic research, and in June 1984 Gallimard published the second and third volumes of ''Histoire de la sexualité''. Volume two, ''L'Usage des plaisirs'', dealt with the "techniques of self" prescribed by ancient Greek pagan morality in relation to sexual ethics, while volume three, ''Le Souci de soi'', explored the same theme in the Greek and Latin texts of the first two centuries CE. A fourth volume, ''Les Aveux de la chair'', was to examine sexuality in early Christianity, but it was not finished.

In October 1980, Foucault became a visiting professor at the

University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

, giving the Howison Lectures on "Truth and Subjectivity", while in November he lectured at the

Humanities Institute at

New York University

New York University (NYU) is a private university, private research university in New York City, New York, United States. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded in 1832 by Albert Gallatin as a Nondenominational ...

. His growing popularity in American intellectual circles was noted by ''

Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' magazine, while Foucault went on to lecture at

University of California, Los Angeles

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California, United States. Its academic roots were established in 1881 as a normal school the ...

in 1981, the

University of Vermont

The University of Vermont and State Agricultural College, commonly referred to as the University of Vermont (UVM), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Burlington, Vermont, United States. Foun ...

in 1982, and Berkeley again in 1983, where his lectures drew huge crowds. Foucault spent many evenings in the

San Francisco gay scene, frequenting

sado-masochistic bathhouses, engaging in unprotected sex. He praised sado-masochistic activity in interviews with the gay press, describing it as "the real creation of new possibilities of pleasure, which people had no idea about previously". Foucault contracted

HIV and eventually developed

AIDS

The HIV, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that attacks the immune system. Without treatment, it can lead to a spectrum of conditions including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). It is a Preventive healthcare, pr ...

. Little was known of the virus at the time; the first cases had only been identified in 1980. Foucault initially referred to AIDS as a "dreamed-up disease". In summer 1983, he developed a persistent dry cough, which concerned friends in Paris, but Foucault insisted it was just a pulmonary infection. Only when hospitalized was Foucault correctly diagnosed as being

HIV-positive; treated with antibiotics, he delivered a final set of lectures at the Collège de France. Foucault entered Paris'

Hôpital de la Salpêtrière—the same institution that he had studied in ''Madness and Civilisation''—on 10 June 1984, with neurological symptoms complicated by

sepsis

Sepsis is a potentially life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs.

This initial stage of sepsis is followed by suppression of the immune system. Common signs and s ...

. He died in the hospital on 25 June.

Death

On 26 June 1984, ''Libération'' announced Foucault's death, mentioning the rumour that it had been brought on by AIDS. The following day, ''Le Monde'' issued a medical bulletin cleared by his family that made no reference to HIV/AIDS. On 29 June, Foucault's ''la levée du corps'' ceremony was held, in which the coffin was carried from the hospital morgue. Hundreds attended, including activists and academic friends, while

Gilles Deleuze

Gilles Louis René Deleuze (18 January 1925 – 4 November 1995) was a French philosopher who, from the early 1950s until his death in 1995, wrote on philosophy, literature, film, and fine art. His most popular works were the two volumes o ...

gave a speech using excerpts from ''The History of Sexuality''. His body was then buried at

Vendeuvre-du-Poitou in a small ceremony. Soon after his death, Foucault's partner

Daniel Defert founded the first national HIV/AIDS organisation in France,

AIDES; a play on the French word for "help" (''aide'') and the English-language acronym for the disease. On the second anniversary of Foucault's death, Defert publicly revealed in ''

The Advocate'' that Foucault's death was AIDS-related.

Personal life

Foucault's first biographer,

Didier Eribon, described the philosopher as "a complex, many-sided character", and that "under one mask there is always another". He also noted that he exhibited an "enormous capacity for work". At the ENS, Foucault's classmates unanimously summed him up as a figure who was both "disconcerting and strange" and "a passionate worker". As he aged, his personality changed: Eribon noted that while he was a "tortured adolescent", post-1960, he had become "a radiant man, relaxed and cheerful", even being described by those who worked with him as a

dandy. He noted that in 1969, Foucault embodied the idea of "the militant intellectual".

Foucault was an

atheist. He loved classical music, particularly enjoying the work of

Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (German: Help:IPA/Standard German, �joːhan zeˈbasti̯an baχ ( – 28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque music, Baroque period. He is known for his prolific output across a variety ...

and

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 1756 – 5 December 1791) was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition and proficiency from an early age ...

, and became known for wearing

turtleneck sweaters. After his death, Foucault's friend

Georges Dumézil described him as having possessed "a profound kindness and goodness", also exhibiting an "intelligence

hat

A hat is a Headgear, head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorpor ...

literally knew no bounds". His life-partner

Daniel Defert inherited his estate, whose archive was sold in 2012 to the

National Library of France for €3.8 million ($4.5 million in April 2021).

Politics