First Presidency Of Grover Cleveland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The first tenure of

Cleveland, too, had detractors—the

Cleveland, too, had detractors—the  Blaine campaigned on implementing a protective tariff, increasing international trade, and investing in infrastructure projects, while the Democratic campaign focused on Blaine's ethics. In general, Cleveland abided by the precedent of minimizing presidential campaign travel and speechmaking; Blaine became one of the first to break with that tradition. Corruption in politics became the central issue in 1884, and Blaine had over the span of his career been involved in several questionable deals. Cleveland's reputation as an opponent of corruption proved the Democrats' strongest asset. Reform-minded Republicans called "

Blaine campaigned on implementing a protective tariff, increasing international trade, and investing in infrastructure projects, while the Democratic campaign focused on Blaine's ethics. In general, Cleveland abided by the precedent of minimizing presidential campaign travel and speechmaking; Blaine became one of the first to break with that tradition. Corruption in politics became the central issue in 1884, and Blaine had over the span of his career been involved in several questionable deals. Cleveland's reputation as an opponent of corruption proved the Democrats' strongest asset. Reform-minded Republicans called "

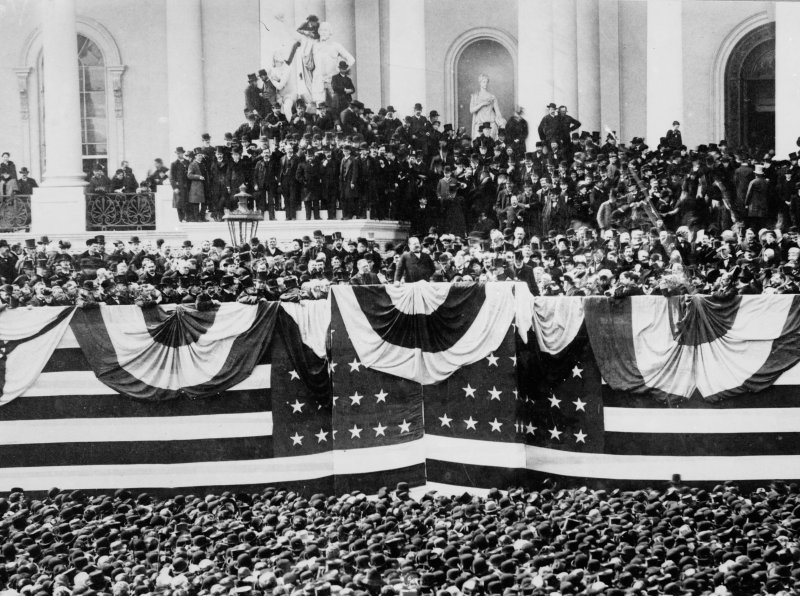

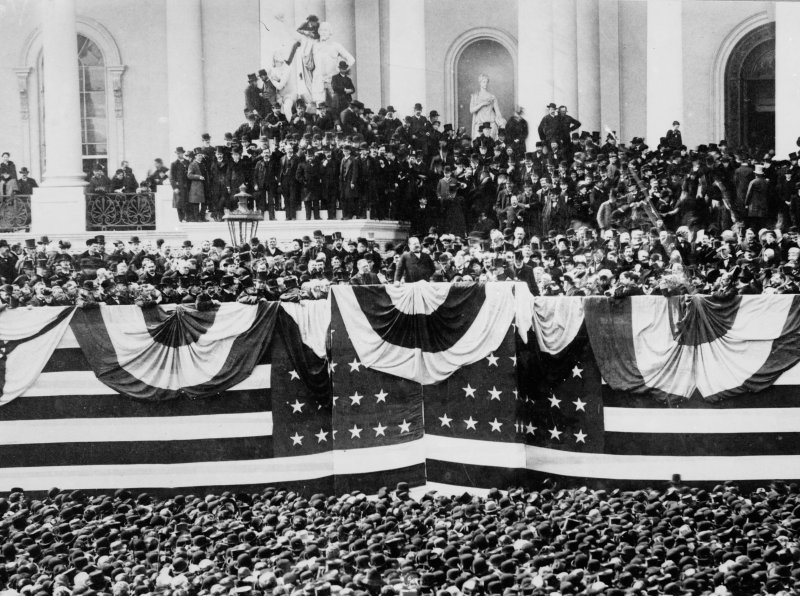

Cleveland was sworn into office as the 22nd president of the United States on March 4, 1885. That same day, Hendricks was sworn in as vice president. Hendricks died days into this term, and the office remained vacant since there was no constitutional provision at the time for filling an intra-term vice-presidential vacancy.

Cleveland was sworn into office as the 22nd president of the United States on March 4, 1885. That same day, Hendricks was sworn in as vice president. Hendricks died days into this term, and the office remained vacant since there was no constitutional provision at the time for filling an intra-term vice-presidential vacancy.

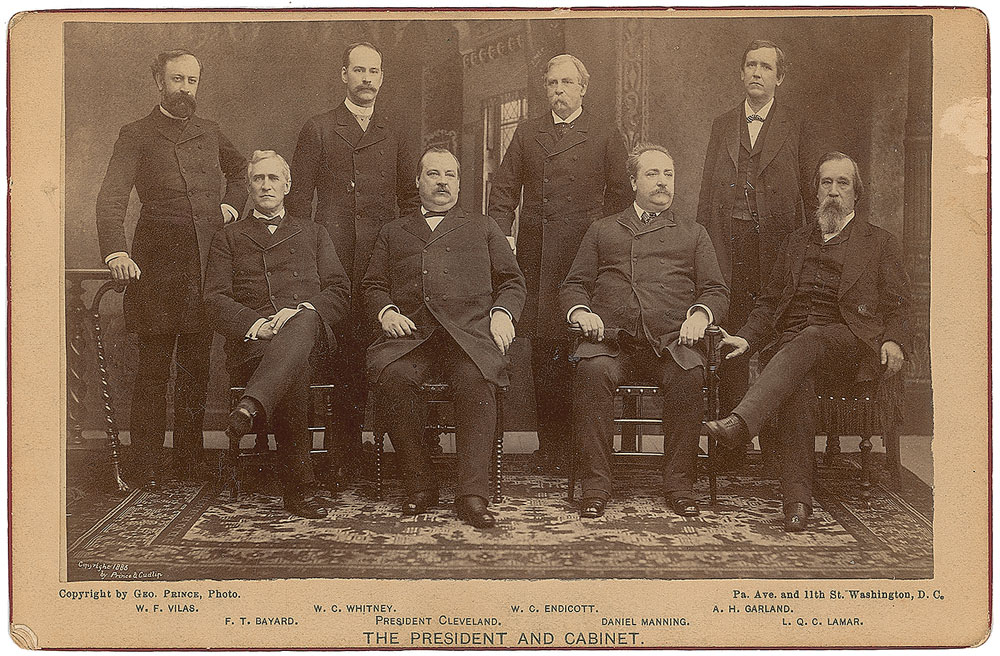

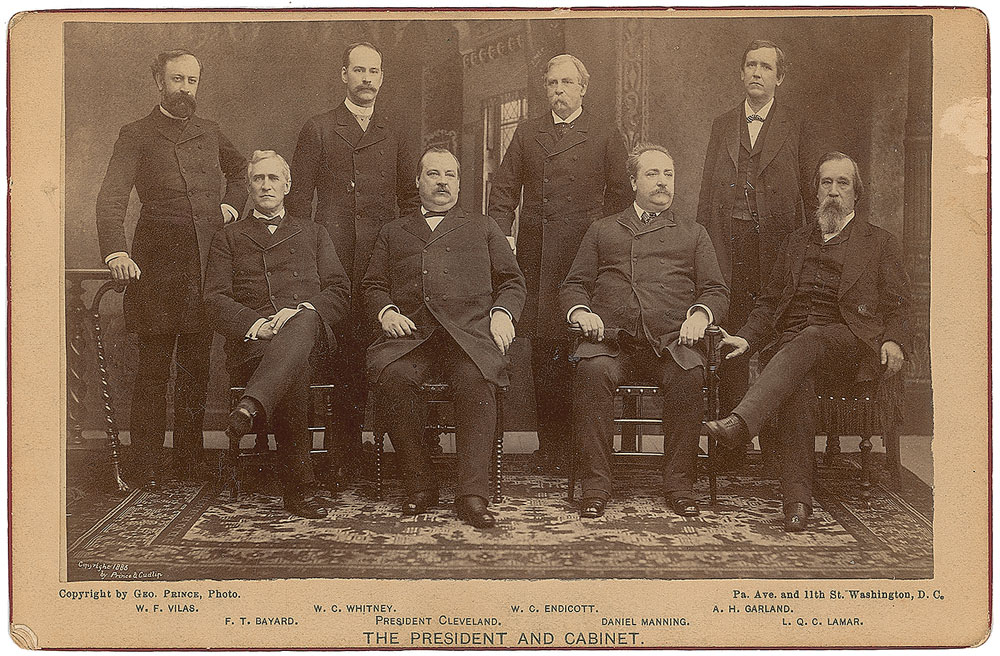

There was much speculation during the presidential transition period about who would be serving in Cleveland's cabinet. It was generally assumed that Thomas F. Bayard would be offered the position of secretary of state. By February 27, 1885, Cleveland had been reported to have settled on all the officeholders for his Cabinet. However, Daniel S. Lamont, Cleveland's private secretary, immediately denied reports that Cleveland had settled upon his Cabinet choices, and that he had announced his selections to others.

Cleveland faced the challenge of putting together the first Democratic cabinet since the 1850s, and none of the individuals that he appointed to his cabinet had served in the cabinet of another administration. Senator Bayard, Cleveland's strongest rival for the 1884 nomination, accepted the position of Secretary of State. Daniel Manning, a key New York adviser for Cleveland as well as a close ally of Samuel Tilden, became the Secretary of the Treasury. Another New Yorker, the prominent financier

There was much speculation during the presidential transition period about who would be serving in Cleveland's cabinet. It was generally assumed that Thomas F. Bayard would be offered the position of secretary of state. By February 27, 1885, Cleveland had been reported to have settled on all the officeholders for his Cabinet. However, Daniel S. Lamont, Cleveland's private secretary, immediately denied reports that Cleveland had settled upon his Cabinet choices, and that he had announced his selections to others.

Cleveland faced the challenge of putting together the first Democratic cabinet since the 1850s, and none of the individuals that he appointed to his cabinet had served in the cabinet of another administration. Senator Bayard, Cleveland's strongest rival for the 1884 nomination, accepted the position of Secretary of State. Daniel Manning, a key New York adviser for Cleveland as well as a close ally of Samuel Tilden, became the Secretary of the Treasury. Another New Yorker, the prominent financier

Cleveland entered the White House as a bachelor, and his sister

Cleveland entered the White House as a bachelor, and his sister

No improvements to U.S. coastal defenses had been made since the late 1870s. The board's 1886 report recommended a massive $127 million construction program at 29 harbors and river estuaries, to include new breech-loading rifled guns, mortars, and naval minefields. Most of the board's recommendations were implemented, and by 1910, 27 locations were defended by over 70 forts. Secretary of the Navy Whitney promoted the modernization of the Navy, although no ships were constructed that could match the best European warships. Construction of four steel-hulled warships that had begun under the Arthur administration was delayed due to a corruption investigation and subsequent bankruptcy of their building yard, but these ships were completed in a timely manner once the investigation was over. Sixteen additional steel-hulled warships were ordered by the end of 1888; these ships later proved vital in the

Cleveland generally did not embrace nativism or immigration restrictions, but he believed that the purpose of immigration was to attract immigrants who would assimilate into American society. Early in his tenure, Cleveland condemned "outrages" against Chinese immigrants, but he eventually came to believe that the deep animosity towards Chinese immigrants in the United States would prevent their assimilation. Secretary of State Bayard negotiated an extension to the

Cleveland generally did not embrace nativism or immigration restrictions, but he believed that the purpose of immigration was to attract immigrants who would assimilate into American society. Early in his tenure, Cleveland condemned "outrages" against Chinese immigrants, but he eventually came to believe that the deep animosity towards Chinese immigrants in the United States would prevent their assimilation. Secretary of State Bayard negotiated an extension to the

With little opposition, Cleveland won re-nomination at the

With little opposition, Cleveland won re-nomination at the

Text of a number of Cleveland's speeches

at the

Finding Aid to the Grover Cleveland Manuscripts, 1867–1908

at the

10 letters written by Grover Cleveland in 1884–86

Media coverage * Other

Grover Cleveland

A bibliography by The

Grover Cleveland Sites in Buffalo, NY

A Google Map developed by The

Index to the Grover Cleveland Papers at the Library of Congress

Essay on Cleveland and each member of his cabinet and First Lady

Miller Center of Public Affairs

"Life Portrait of Grover Cleveland"

from

Interview with H. Paul Jeffers on ''An Honest President: The Life and Presidencies of Grover Cleveland''

''

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

as president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

began on March 4, 1885, when he was inaugurated as the nation's 22nd president, and ended on March 4, 1889. Cleveland, a Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (Cyprus) (DCY)

**Democratic Part ...

from New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

, took office following his victory over James G. Blaine

James Gillespie Blaine (January 31, 1830January 27, 1893) was an American statesman and Republican politician who represented Maine in the United States House of Representatives from 1863 to 1876, serving as speaker of the U.S. House of Rep ...

, a Republican from Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

, in the 1884 presidential election. Cleveland became the first Democrat elected president since before the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

. His first presidency ended following his defeat in the 1888 election to Republican Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was the 23rd president of the United States, serving from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia—a grandson of the ninth president, William Henry Harrison, and a ...

of Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

.

Cleveland won the 1884 election with the support of a reform-minded group of Republicans known as Mugwumps

The Mugwumps were History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican political activists in the United States who were intensely opposed to political corruption. They were never formally organized. They famously Party switching, swit ...

, and he expanded the number of government positions that were protected by the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act

The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act is a United States federal law passed by the 47th United States Congress and signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur on January 16, 1883. The act mandates that most positions within the Federal gover ...

. He also vetoed several bills designed to provide pension

A pension (; ) is a fund into which amounts are paid regularly during an individual's working career, and from which periodic payments are made to support the person's retirement from work. A pension may be either a " defined benefit plan", wh ...

s and other benefits to various regions and individuals. In response to anti-competitive practices

Anti-competitive practices are business or government practices that prevent or reduce Competition (economics), competition in a market. Competition law, Antitrust laws ensure businesses do not engage in competitive practices that harm other, u ...

by railroads, Cleveland signed the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887

The Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 is a United States federal law that was designed to regulate the railroad industry, particularly its monopolistic practices. The Act required that railroad rates be "reasonable and just", but did not empowe ...

, which established the first independent federal agency. During his first term, he unsuccessfully sought the repeal of the Bland–Allison Act

The Bland–Allison Act, also referred to as the Grand Bland Plan of 1878, was an act of the United States Congress requiring the U.S. Treasury to buy a certain amount of silver and put it into circulation as silver dollars. Though the bill was ...

and a lowering of the tariff

A tariff or import tax is a duty (tax), duty imposed by a national Government, government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods ...

. The Samoan crisis

The Samoan crisis was a standoff between the United States, the German Empire, and the British Empire from 1887 to 1889 over control of the Samoan Islands during the First Samoan Civil War.

Background

In 1878, the United States acquired a fuel ...

was the major foreign policy event of Cleveland's first term, and that crisis ended with a tripartite protectorate in the Samoan Islands

The Samoan Islands () are an archipelago covering in the central Pacific Ocean, South Pacific, forming part of Polynesia and of the wider region of Oceania. Political geography, Administratively, the archipelago comprises all of the Samoa, Indep ...

.

Cleveland defeated Harrison in 1892

In Samoa, this was the only leap year spanned to 367 days as July 4 repeated. This means that the International Date Line was drawn from the east of the country to go west.

Events

January

* January 1 – Ellis Island begins processing imm ...

and started his second presidency on March 4, 1893, as the 24th president, thus becoming the first U.S. president to leave office after one term and later be elected for a second term.

Election of 1884

Cleveland had risen to prominence as an advocate of civil service reform, and he was widely viewed as a presidential contender after his victory in the1882 New York gubernatorial election

The 1882 New York gubernatorial election was held on November 7, 1882.

Republican incumbent Alonzo B. Cornell ran for re-election to a second term in office, but was defeated for the Republican nomination by Charles J. Folger, the Secretar ...

. Samuel J. Tilden, the party's nominee in 1876, was the initial front-runner, but he declined to run due to poor health.Nevins, 146–147 Cleveland, Thomas F. Bayard of Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

, Allen G. Thurman of Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

, and Benjamin Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (November 5, 1818 – January 11, 1893) was an American major general (United States), major general of the Union Army, politician, lawyer, and businessman from Massachusetts. Born in New Hampshire and raised in Lowell, ...

of Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

each had considerable followings entering the 1884 Democratic National Convention

The 1884 Democratic National Convention was held July 8–11, 1884 and chose Governor Grover Cleveland of New York their presidential nominee with the former Governor Thomas A. Hendricks of Indiana as the vice presidential nominee. World Book

B ...

. Each of the other candidates had hindrances to his nomination: Bayard had spoken in favor of secession

Secession is the formal withdrawal of a group from a Polity, political entity. The process begins once a group proclaims an act of secession (such as a declaration of independence). A secession attempt might be violent or peaceful, but the goal i ...

in 1861, making him unacceptable to Northerners; Butler, conversely, was reviled throughout the South for his actions during the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

; Thurman was generally well liked, but was growing old and infirm, and his views on the silver question were uncertain.

Cleveland, too, had detractors—the

Cleveland, too, had detractors—the Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was an American political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789, as the Tammany Society. It became the main local ...

political machine opposed him—but the nature of his enemies made him still more friends. He also benefited from the backing of state party leader Daniel Manning, who positioned Cleveland as the natural heir to Tilden and emphasized the importance of New York's electoral votes

An electoral college is a body whose task is to elect a candidate to a particular office. It is mostly used in the political context for a constitutional body that appoints the head of state or government, and sometimes the upper parliamenta ...

in any Democratic presidential victory. Cleveland led on the convention's first ballot and clinched the nomination on the second ballot.Nevins, 153-154; Graff, 53–54 Thomas A. Hendricks

Thomas Andrews Hendricks (September 7, 1819 – November 25, 1885) was an American politician and lawyer from Indiana who served as the 16th governor of Indiana from 1873 to 1877 and the 21st vice president of the United States from March until ...

of Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

was selected as his running mate. The 1884 Republican National Convention

The 1884 Republican National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held at the Exposition Hall in Chicago, on June 3–6, 1884. It resulted in the nomination of former House Speaker James G. Blaine from Maine for president and S ...

nominated former Speaker of the House James G. Blaine

James Gillespie Blaine (January 31, 1830January 27, 1893) was an American statesman and Republican politician who represented Maine in the United States House of Representatives from 1863 to 1876, serving as speaker of the U.S. House of Rep ...

of Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

for president; Blaine's nomination alienated many Republicans who viewed Blaine as ambitious and immoral.Nevins, 185–186; Jeffers, 96–97

Mugwump

The Mugwumps were History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican political activists in the United States who were intensely opposed to political corruption. They were never formally organized. They famously Party switching, swit ...

s", including men such as Carl Schurz

Carl Christian Schurz (; March 2, 1829 – May 14, 1906) was a German-American revolutionary and an American statesman, journalist, and reformer. He migrated to the United States after the German revolutions of 1848–1849 and became a prominent ...

and Henry Ward Beecher

Henry Ward Beecher (June 24, 1813 – March 8, 1887) was an American Congregationalist clergyman, social reformer, and speaker, known for his support of the Abolitionism, abolition of slavery, his emphasis on God's love, and his 1875 adultery ...

, denounced Blaine as corrupt and flocked to Cleveland. At the same time the Democrats gained support from the Mugwumps, they lost some blue-collar workers to the Greenback-Labor party, led by Benjamin Butler.

As expected, Cleveland carried the Solid South

The Solid South was the electoral voting bloc for the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party in the Southern United States between the end of the Reconstruction era in 1877 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In the aftermath of the Co ...

, while Blaine carried most of New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

and the Midwest

The Midwestern United States (also referred to as the Midwest, the Heartland or the American Midwest) is one of the four census regions defined by the United States Census Bureau. It occupies the northern central part of the United States. It ...

. The electoral votes of closely contested New York, New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

, Indiana, and Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

determined the election. After the votes were counted, Cleveland narrowly won all four of the swing state

In United States politics, a swing state (also known as battleground state, toss-up state, or purple state) is any state that could reasonably be won by either the Democratic or Republican candidate in a statewide election, most often refe ...

s; he won his home state of New York by a margin of 0.1%, which amounted to just 1200 votes., Cleveland won the nationwide popular vote by one-quarter of a percent, while he won the electoral vote by a majority of 219–182. Cleveland's victory made him the first successful Democratic presidential nominee since the start of the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

. Despite Cleveland's successful candidacy, Republicans retained control of the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

.

Administration

Cleveland was sworn into office as the 22nd president of the United States on March 4, 1885. That same day, Hendricks was sworn in as vice president. Hendricks died days into this term, and the office remained vacant since there was no constitutional provision at the time for filling an intra-term vice-presidential vacancy.

Cleveland was sworn into office as the 22nd president of the United States on March 4, 1885. That same day, Hendricks was sworn in as vice president. Hendricks died days into this term, and the office remained vacant since there was no constitutional provision at the time for filling an intra-term vice-presidential vacancy.

Cabinet

Appointments

There was much speculation during the presidential transition period about who would be serving in Cleveland's cabinet. It was generally assumed that Thomas F. Bayard would be offered the position of secretary of state. By February 27, 1885, Cleveland had been reported to have settled on all the officeholders for his Cabinet. However, Daniel S. Lamont, Cleveland's private secretary, immediately denied reports that Cleveland had settled upon his Cabinet choices, and that he had announced his selections to others.

Cleveland faced the challenge of putting together the first Democratic cabinet since the 1850s, and none of the individuals that he appointed to his cabinet had served in the cabinet of another administration. Senator Bayard, Cleveland's strongest rival for the 1884 nomination, accepted the position of Secretary of State. Daniel Manning, a key New York adviser for Cleveland as well as a close ally of Samuel Tilden, became the Secretary of the Treasury. Another New Yorker, the prominent financier

There was much speculation during the presidential transition period about who would be serving in Cleveland's cabinet. It was generally assumed that Thomas F. Bayard would be offered the position of secretary of state. By February 27, 1885, Cleveland had been reported to have settled on all the officeholders for his Cabinet. However, Daniel S. Lamont, Cleveland's private secretary, immediately denied reports that Cleveland had settled upon his Cabinet choices, and that he had announced his selections to others.

Cleveland faced the challenge of putting together the first Democratic cabinet since the 1850s, and none of the individuals that he appointed to his cabinet had served in the cabinet of another administration. Senator Bayard, Cleveland's strongest rival for the 1884 nomination, accepted the position of Secretary of State. Daniel Manning, a key New York adviser for Cleveland as well as a close ally of Samuel Tilden, became the Secretary of the Treasury. Another New Yorker, the prominent financier William C. Whitney

William Collins Whitney (July 5, 1841February 2, 1904) was an American political leader and financier and a prominent member of the Whitney family. He served as Secretary of the Navy in the first administration of President Grover Cleveland from ...

, was appointed Secretary of the Navy. For the position of Secretary of War, Cleveland appointed William C. Endicott, a prominent Massachusetts judge with ties to the Mugwumps. Cleveland chose two Southerners for his cabinet: Lucius Q. C. Lamar of Mississippi as Secretary of the Interior, and Augustus H. Garland of Arkansas as Attorney General. Postmaster General William F. Vilas of Wisconsin was the lone Westerner in the cabinet. Daniel S. Lamont served as Cleveland's private secretary, becoming one of the most important individuals in the administration.

Marriage and children

Cleveland entered the White House as a bachelor, and his sister

Cleveland entered the White House as a bachelor, and his sister Rose Cleveland

Rose Elizabeth "Libby" Cleveland (June 13, 1846 – November 22, 1918) was an American author and lecturer. She was acting first lady of the United States from 1885 to 1886, during the presidency of her brother, Grover Cleveland.

Receiving an ...

acted as hostess for the first two years of his administration. On June 2, 1886, Cleveland married Frances Folsom in the Blue Room at the White House. Though Cleveland had supervised Frances's upbringing after her father's death, the public took no exception to the match. At 21 years, Frances Folsom Cleveland was the youngest First Lady in history, and the public soon warmed to her beauty and warm personality.

Reforms and civil service

Presidential appointments until now were typically filled under thespoils system

In politics and government, a spoils system (also known as a patronage system) is a practice in which a political party, after winning an election, gives government jobs to its supporters, friends (cronyism), and relatives (nepotism) as a rewar ...

. However Cleveland announced that he would not fire any Republican who was doing his job well, and would not appoint anyone solely on the basis of party service. Later in his term, as his fellow Democrats chafed at being excluded from the patronage, Cleveland began to replace more of the partisan Republican officeholders with Democrats; this was especially the case with policy-making positions. While some of his decisions were influenced by party concerns, more of Cleveland's appointments were decided by merit alone than was the case in his predecessors' administrations. During his first term, Cleveland also expanded the number of federal positions subject to the merit system (under the terms of the recently passed Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act

The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act is a United States federal law passed by the 47th United States Congress and signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur on January 16, 1883. The act mandates that most positions within the Federal gover ...

) from 16,000 to 27,000. Due to Cleveland's and Harrison's efforts, between 1885 and 1897, the percentage of federal employees protected by the Pendleton Act rose from twelve percent to forty percent. Nonetheless, many Mugwumps were disappointed by Cleveland's unwillingness to promote a truly nonpartisan civil service.

Cleveland was the first Democratic president subject to the Tenure of Office Act, which originated in 1867; the act purported to require the Senate to approve the dismissal of any presidential appointee who was originally subject to its advice and consent. Cleveland resisted the Senate's attempts to enforce the act, and invoked executive privilege

Executive privilege is the right of the president of the United States and other members of the executive branch to maintain confidential communications under certain circumstances within the executive branch and to resist some subpoenas and ot ...

in refusing to hand over documents related to appointments. Despite criticism from reformers like Carl Schurz, Cleveland's stance proved popular with the public. Republican Senator George Frisbie Hoar

George Frisbie Hoar (August 29, 1826 – September 30, 1904) was an American attorney and politician, represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1877 until his death in 1904. He belonged to an extended family that became politic ...

proposed a bill to repeal the Tenure of Office Act, and Cleveland signed the repeal into law in March 1887.

In 1889, Cleveland signed into law a bill that elevated the Department of Agriculture

An agriculture ministry (also called an agriculture department, agriculture board, agriculture council, or agriculture agency, or ministry of rural development) is a ministry charged with agriculture. The ministry is often headed by a minister f ...

to the cabinet level, and Norman Jay Coleman

Norman Jay Colman (May 16, 1827 – November 3, 1911) was a politician, attorney, educator, newspaper publisher, and, for 18 days, the first United States secretary of agriculture.

Louisville, Kentucky

Colman was born in Richfield Springs, Ne ...

became the first United States Secretary of Agriculture

The United States secretary of agriculture is the head of the United States Department of Agriculture. The position carries similar responsibilities to those of agriculture ministers in other governments

The department includes several organi ...

. Cleveland angered railroad investors by ordering an investigation of Western lands they held by government grant.Nevins, 223–228 Secretary of the Interior Lamar charged that the rights of way for this land must be returned to the public because the railroads failed to extend their lines according to agreements. The lands were forfeited, resulting in the return of approximately .

Interstate Commerce Act

During the 1880s, public support for the regulation of railroads grew because of anger over anti-competitive railroad practices such as "discrimination," in which the railroads charged different rates to different clients.White, pp. 582–586 Though often critical of the business practices of railroad magnates likeJay Gould

Jason Gould (; May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was an American railroad magnate and financial speculator who founded the Gould family, Gould business dynasty. He is generally identified as one of the Robber baron (industrialist), robber bar ...

, Cleveland was generally reluctant to involve the federal government in regulatory matters. Despite this reluctance, after the Supreme Court's holding in the 1886 case of '' Wabash, St. Louis & Pacific Railway Co. v. Illinois'' severely limited the power of states to regulate interstate commerce, Cleveland assented to legislation providing for federal oversight of railroads. In 1887, he signed the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887

The Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 is a United States federal law that was designed to regulate the railroad industry, particularly its monopolistic practices. The Act required that railroad rates be "reasonable and just", but did not empowe ...

, which created the Interstate Commerce Commission

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) was a regulatory agency in the United States created by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The agency's original purpose was to regulate railroads (and later Trucking industry in the United States, truc ...

(ICC), a five-member commission tasked with investigating railroad practices. The ICC was charged with helping to ensure that the railroads charged fair rates, but the power to determine whether rates were fair was assigned to the courts. In addition to creating the ICC, the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 required railroads to publicly post rates and made the practice of railroad pooling illegal. The act was the first federal law to regulate private industry in the United States, and the ICC was the first independent agency

A regulatory agency (regulatory body, regulator) or independent agency (independent regulatory agency) is a government authority that is responsible for exercising autonomous jurisdiction over some area of human activity in a licensing and regu ...

of the federal government. The Interstate Commerce Act had only a modest effect on railroad practices, as talented railroad lawyers and a conservative judiciary limited the impact of the various provisions of the law.

Vetoes

Cleveland used theveto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president (government title), president or monarch vetoes a bill (law), bill to stop it from becoming statutory law, law. In many countries, veto powe ...

far more often than any president up to that time. He vetoed hundreds of private pension bills for Civil War veterans, believing that if their pensions requests had already been rejected by the Pension Bureau The Bureau of Pensions was an agency of the federal government of the United States which existed from 1832 to 1930. It originally administered pensions solely for military personnel. Pension duties were transferred to the United States Department o ...

, Congress should not attempt to override that decision. When Congress, pressured by the Grand Army of the Republic

The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) was a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army (United States Army), Union Navy (United States Navy, U.S. Navy), and the United States Marine Corps, Marines who served in the American Ci ...

, passed a bill granting pensions for disabilities not caused by military service, Cleveland also vetoed that. In 1887, Cleveland issued his most well-known veto, of the Texas Seed Bill.Nevins, 331–332; Graff, 85 A severe drought had devastated many in Texas, with some numbers suggesting that 85% of cattle died in the western part of the state. Many farmers themselves were on the brink of starvation as a result of the crisis. Congress, in response, appropriated $10,000 to purchase seed grain for farmers there. Cleveland vetoed the expenditure. In his veto message, he espoused a theory of limited government:

Monetary policy

One of the most volatile issues of the 1880s was whether the currency should be backed by gold and silver, or by gold alone. The issue cut across party lines, with Western Republicans and Southern Democrats joining in the call for the free coinage of silver, and both parties' representatives in the Northeast favoring the gold standard.Nevins, 201–205; Graff, 102–103 Because silver was worth less than its legal equivalent in gold, taxpayers paid their government bills in silver, while international creditors demanded payment in gold, resulting in a depletion of the nation's gold supply. Bimetallism tended to result in inflation, which in turn made it easier for debtors to pay off their loans and increased agricultural prices. It was thus popular in many agrarian states. Cleveland saw monetary policy as both an economic and moral issue; he thought that adherence to the gold standard would ensure a stable currency, and also felt that those who had extended loans should not be penalized by rising inflation.Welch, 117–119 Cleveland and Treasury Secretary Manning tried to reduce the amount of silver that the government was required to coin under theBland–Allison Act

The Bland–Allison Act, also referred to as the Grand Bland Plan of 1878, was an act of the United States Congress requiring the U.S. Treasury to buy a certain amount of silver and put it into circulation as silver dollars. Though the bill was ...

of 1878. Cleveland also unsuccessfully appealed to Congress to repeal this law before he was inaugurated. In reply, one of the foremost silverites, Richard P. Bland

Richard Parks Bland (August 19, 1835 – June 15, 1899) was an American politician, lawyer, and educator from Missouri. A Democrat, Bland served in the United States House of Representatives from 1873 to 1895 and from 1897 to 1899,

representin ...

, introduced a bill in 1886 that would require the government to coin unlimited amounts of silver, inflating the then-deflating currency.Nevins, 273 While Bland's bill was defeated, so was a bill the administration favored that would repeal any silver coinage requirement. The result was a retention of the status quo, and a postponement of the resolution of the Free Silver issue.

Tariffs

American tariff rates had increased dramatically during the Civil War, and by the 1880s the tariff brought in so much revenue that the government was running a surplus. Cleveland had not campaigned on the tariff in the 1884 election, but his cabinet, like most Democrats, were sympathetic to calls for lower tariffs.Graff, 85-87 Cleveland's opposition to protective tariffs was rooted in his belief that they unfairly benefited certain industries, and unfairly taxed consumers, by raising prices. Republicans, by contrast, generally favored a high tariff to protect American industries from foreign competitors.Nevins, 280–282, Reitano, 46–62 Cleveland recommended a reduction of the tariff as part of his first two annual messages to Congress, and he devoted the entirety of his 1887 annual message to tariff reduction. Cleveland warned that the budget surpluses caused by the high tariffs would lead to a financial crisis. Despite Cleveland's advocacy, no major tariff bill passed during Cleveland's first presidency. In 1886, a bill to reduce the tariff was narrowly defeated in the House. Republicans, as well as protectionist Northern Democrats like Samuel J. Randall, believed that American industries would fail absent high tariffs, and continued to fight efforts to lower tariffs. Roger Q. Mills, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, proposed a bill to reduce the tariff from about 47% to about 40%.Graff, 88–89 After significant exertions by Cleveland and his allies, the bill passed the House. Senate Republicans countered by introducing theBlair

Blair is a Scots-English-language name of Scottish Gaelic origin.

The surname is derived from any of the numerous places in Scotland called ''Blair'', derived from the Scottish Gaelic ''blàr'', meaning "plain", "meadow" or " field", frequently ...

Education Bill, which would have granted federal educational aid to states based on illiteracy rates. The bill passed the Senate with the support of many Southern Democrats, whose constituents benefited disproportionately from the bill. The Senate refused to pass the Mills Tariff, while the House refused to pass the Blair Education Bill. Debate over the tariff persisted into the 1888 presidential election.

Foreign policy

Cleveland was a committed non-interventionist who had campaigned in opposition to expansion and imperialism. He refused to support the Frelinghuysen-Zavala Treaty, negotiated by the lame duck Arthur Administration, which would have allowed the United States to build acanal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface ...

in Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

connecting the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

and the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

. He did, however, see the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a foreign policy of the United States, United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign ...

as an important plank of foreign policy, and he sought to protect American hegemony in the Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth that lies west of the Prime Meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and east of the 180th meridian.- The other half is called the Eastern Hemisphere. Geopolitically, ...

. Secretary of State Bayard negotiated with Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal Party (UK), Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually was a leading New Imperialism, imperial ...

of Great Britain over fishing rights in the waters off Canada, and struck a conciliatory note, despite the opposition of New England's Republican senators. Cleveland also withdrew from Senate consideration the Berlin Conference treaty, which guaranteed an open door for U.S. interests in the Congo.Zakaria, 80

Cleveland's presidency saw the start of the Samoan crisis

The Samoan crisis was a standoff between the United States, the German Empire, and the British Empire from 1887 to 1889 over control of the Samoan Islands during the First Samoan Civil War.

Background

In 1878, the United States acquired a fuel ...

between the U.S., Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, and Great Britain. Each of those nations had signed a treaty with Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa and known until 1997 as Western Samoa, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania, in the South Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu), two smaller, inhabited ...

under which they were allowed to engage in trade and maintain a naval base, but Cleveland feared that the Germans sought to annex Samoa after the Germans attempted to remove Malietoa Laupepa

Susuga Malietoa Laupepa (1841 – 22 August 1898) was the ruler ( Malietoa) of Samoa in the late 19th century. He was first crowned in 1875.

During his tenure as King, he fought constant warfare from many contenders to the throne, these battles ...

as the monarch of Samoa in favor of Tuiātua Tupua Tamasese Titimaea. The U.S. encouraged another claimant to the throne, Mata'afa Iosefo, to rebel against Malietoa, and in doing so Mata'afa's forces killed a contingent of German naval guards. German Chancellor Otto Von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

threatened a retaliatory war, but Germany backed down in the face of American and British resistance. In a subsequent conference that took place shortly after Cleveland left office, the United States, Germany, and Britain agreed to make Samoa a joint protectorate.

Military policy

Cleveland's military policy emphasized self-defense and modernization. In 1885 Cleveland established theBoard of Fortifications

Several boards have been appointed by US presidents or Congress to evaluate the US defensive fortifications, primarily coastal defenses near strategically important harbors on the US shores, its territories, and its protectorates.

Endicott Board ...

under Secretary of War Endicott to recommend a new coastal fortification system for the United States.?? Mark A. Berhow, ''American Seacoast Defenses A Reference Guide'' (1999) pp. 9–10Endicott and Taft Boards at the Coast Defense Study Group websiteNo improvements to U.S. coastal defenses had been made since the late 1870s. The board's 1886 report recommended a massive $127 million construction program at 29 harbors and river estuaries, to include new breech-loading rifled guns, mortars, and naval minefields. Most of the board's recommendations were implemented, and by 1910, 27 locations were defended by over 70 forts. Secretary of the Navy Whitney promoted the modernization of the Navy, although no ships were constructed that could match the best European warships. Construction of four steel-hulled warships that had begun under the Arthur administration was delayed due to a corruption investigation and subsequent bankruptcy of their building yard, but these ships were completed in a timely manner once the investigation was over. Sixteen additional steel-hulled warships were ordered by the end of 1888; these ships later proved vital in the

Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

of 1898, and many served in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. These ships included the "second-class battleships" and , which were designed to match modern armored ships recently acquired by South American countries from Europe. Eleven protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of cruiser of the late 19th century, took their name from the armored deck, which protected vital machine-spaces from fragments released by explosive shells. Protected cruisers notably lacked a belt of armour alon ...

s (including ), one armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a pre-dreadnought battles ...

, and one monitor

Monitor or monitor may refer to:

Places

* Monitor, Alberta

* Monitor, Indiana, town in the United States

* Monitor, Kentucky

* Monitor, Oregon, unincorporated community in the United States

* Monitor, Washington

* Monitor, Logan County, Wes ...

were also ordered, along with the experimental cruiser .

Civil rights and immigration

Cleveland, like a growing number of Northerners (and nearly all white Southerners), believed thatReconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

had been a failed experiment. He was unwilling to use federal power to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment, which guaranteed voting rights to African-Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa. ...

.Welch, 65–66 Though Cleveland appointed no black Americans to patronage jobs, he allowed Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He was the most impor ...

to continue in his post as recorder of deeds

Recorder of deeds or deeds registry is a government office tasked with maintaining public records and documents, especially records relating to real estate ownership that provide persons other than the owner of a property with real rights ove ...

in Washington, D.C. and appointed another black man to replace Douglass upon his resignation.

Cleveland generally did not embrace nativism or immigration restrictions, but he believed that the purpose of immigration was to attract immigrants who would assimilate into American society. Early in his tenure, Cleveland condemned "outrages" against Chinese immigrants, but he eventually came to believe that the deep animosity towards Chinese immigrants in the United States would prevent their assimilation. Secretary of State Bayard negotiated an extension to the

Cleveland generally did not embrace nativism or immigration restrictions, but he believed that the purpose of immigration was to attract immigrants who would assimilate into American society. Early in his tenure, Cleveland condemned "outrages" against Chinese immigrants, but he eventually came to believe that the deep animosity towards Chinese immigrants in the United States would prevent their assimilation. Secretary of State Bayard negotiated an extension to the Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was a United States Code, United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law made exceptions for travelers an ...

, and Cleveland lobbied the Congress to pass the Scott Act, written by Congressman William Lawrence Scott

William Lawrence Scott (July 2, 1828 – September 19, 1891) was a Democratic member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, a prominent railroad executive, as well as a prominent horse breeder and horse racer.

Early life

Wi ...

, which prevented the return of Chinese immigrants who left the United States. The Scott Act easily passed both houses of Congress, and Cleveland signed it into law in October 1888.

Indian policy

Approximately 250,000 Native Americans lived in the United States when Cleveland took office, a dramatic decline from previous decades. Cleveland viewed Native Americans aswards of the state

Ward may refer to:

Division or unit

* Hospital ward, a hospital division, floor, or room set aside for a particular class or group of patients, for example the psychiatric ward

* Prison ward, a division of a penal institution such as a pri ...

, saying in his first inaugural address that " is guardianship involves, on our part, efforts for the improvement of their condition and enforcement of their rights."Welch, 70; Nevins, 358–359 Cleveland encouraged the idea of cultural assimilation

Cultural assimilation is the process in which a minority group or culture comes to resemble a society's Dominant culture, majority group or fully adopts the values, behaviors, and beliefs of another group. The melting pot model is based on this ...

, pushing for the passage of the Dawes Act

The Dawes Act of 1887 (also known as the General Allotment Act or the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887) regulated land rights on tribal territories within the United States. Named after Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, it authorized the P ...

, which provided for distribution of Indian lands to individual members of tribes, rather than having them continued to be held in trust for the tribes by the federal government. While a conference of Native leaders endorsed the act, in practice the majority of Native Americans disapproved of it. Cleveland believed the Dawes Act would lift Native Americans out of poverty and encourage their assimilation into white society, but it ultimately weakened the tribal governments because it allowed individual Indians to sell tribal land and keep the money for themselves. Between 1881 and 1900, the total land held by Native Americans fell from 155 million acres to 77 million acres.

In the month before Cleveland's 1885 inauguration, President Arthur opened four million acres of Winnebago and Crow Creek Indian lands in the Dakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of ...

to white settlement by executive order.Brodsky, 141–142; Nevins, 228–229 Tens of thousands of settlers gathered at the border of these lands and prepared to take possession of them. Cleveland believed Arthur's order to be in violation of treaties with the tribes, and rescinded it on April 17 of that year, ordering the settlers out of the territory. Cleveland sent in eighteen companies

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of legal people, whether natural, juridical or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specifi ...

of Army troops to enforce the treaties and ordered General Philip Sheridan

Philip Henry Sheridan (March 6, 1831 – August 5, 1888) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close association with General-i ...

, at the time Commanding General of the U.S. Army, to investigate the matter.

Judicial appointments

During his first term, Cleveland successfully nominated two justices to theSupreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all Federal tribunals in the United States, U.S. federal court cases, and over Stat ...

. After Associate Justice William Burnham Woods

William Burnham Woods (August 3, 1824 – May 14, 1887) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. An appointee of President Rutherford B. Hayes, he served from 1881 until 1887. He w ...

died, Cleveland nominated Interior Secretary Lucius Q.C. Lamar to the Supreme Court in late 1887. While Lamar had been well-liked as a Senator, his service under the Confederacy two decades earlier caused many Republicans to vote against him. Lamar's nomination was confirmed by the narrow margin of 32 to 28.

Chief Justice Morrison Waite

Morrison Remick "Mott" Waite (November 29, 1816 – March 23, 1888) was an American attorney, jurist, and politician from Ohio who served as the seventh chief justice of the United States from 1874 until his death in 1888. During his tenure ...

died in March 1888, and Cleveland nominated Melville Fuller

Melville Weston Fuller (February 11, 1833 – July 4, 1910) was an American politician, attorney, and jurist who served as the eighth chief justice of the United States from 1888 until his death in 1910. Staunch conservatism marked his t ...

to fill his seat. Though Fuller had previously declined Cleveland's nomination to the Civil Service Commission

A civil service commission (also known as a Public Service Commission) is a government agency or public body that is established by the constitution, or by the legislature, to regulate the employment and working conditions of civil servants, overse ...

, he accepted the nomination to the Supreme Court. The Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally known as the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a Standing committee (United States Congress), standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the United States Departm ...

spent several months examining the little-known nominee, before the Senate confirmed the nomination 41 to 20.Nevins, 445–450 Fuller served as Chief Justice until 1910, presiding over a court that inaugurated the Lochner era

The ''Lochner'' era was a period in American legal history from 1897 to 1937 in which the Supreme Court of the United States is said to have made it a common practice "to strike down economic regulations adopted by a State based on the Court's o ...

.

Election of 1888

1888 Democratic National Convention

The 1888 Democratic National Convention was a nominating convention held June 5 to 7, 1888, in the St. Louis Exposition and Music Hall in St. Louis, Missouri. It nominated President Grover Cleveland for reelection and former Senator Allen G. ...

, making him the first Democratic president to win re-nomination since Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was the eighth president of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as Attorney General o ...

in 1840

Events

January–March

* January 3 – One of the predecessor papers of the ''Herald Sun'' of Melbourne, Australia, ''The Port Phillip Herald'', is founded.

* January 10 – Uniform Penny Post is introduced in the United Kingdom.

* Janu ...

. Vice President Hendricks having died in 1885, the Democrats chose Allen G. Thurman of Ohio to be Cleveland's new running mate.Graff, 90–91 Former Senator Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was the 23rd president of the United States, serving from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia—a grandson of the ninth president, William Henry Harrison, and a ...

of Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

defeated John Sherman

John Sherman (May 10, 1823October 22, 1900) was an American politician from Ohio who served in federal office throughout the Civil War and into the late nineteenth century. A member of the Republican Party, he served in both houses of the U. ...

and several other candidates to win the presidential nomination of the 1888 Republican National Convention

The 1888 Republican National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held at the Auditorium Theatre in Chicago, Illinois, on June 19–25, 1888. It resulted in the nomination of former United States Senate, Senator Benjamin Harrison of ...

. The Republicans campaigned heavily on the tariff issue, turning out protectionist voters in the important industrial states of the North.Nevins, 418–420 Democrats in the crucial swing state of New York were divided over the gubernatorial candidacy of David B. Hill, weakening Cleveland's support. The Republicans gained the upper hand in the campaign, as Cleveland's campaign was poorly managed by Calvin S. Brice and William H. Barnum, whereas Harrison had engaged more aggressive fundraisers and tacticians in Matt Quay and John Wanamaker

John Wanamaker (July 11, 1838December 12, 1922) was an American merchant and religious, civic and political figure, considered by some to be a proponent of advertising and a "pioneer in marketing". He served as United States Postmaster General ...

. The Cleveland campaign was further damaged by the desertion of many Mugwumps, who were disappointed by the lack of far-reaching civil service reforms.

As in 1884, the election focused on the swing states of New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Indiana. Cleveland won every state he had carried in 1884 except for Indiana and his home state of New York, both of which were narrowly won by Harrison., Though Cleveland won the nationwide popular vote by a margin of 0.8%, the loss of his home state's 36 electoral votes denied him re-election. Republicans also won control of the House of Representatives, giving the party control of both houses of Congress for the first time since 1875. Cleveland's loss made him the first incumbent president since Van Buren to be defeated in the general election.Charles W. Calhoun, ''Minority Victory: Gilded Age Politics and the Front Porch Campaign of 1888'' (University Press of Kansas, 2008).

Notes

References

External links

Letters and speechesText of a number of Cleveland's speeches

at the

Miller Center of Public Affairs

The Miller Center is a nonpartisan affiliate of the University of Virginia that specializes in United States presidential scholarship, public policy, and political history. It is headquartered at Faulkner House.

History

The Miller Center wa ...

Finding Aid to the Grover Cleveland Manuscripts, 1867–1908

at the

New York State Library

The New York State Library is a research library in Albany, New York, United States. It was established in 1818 to serve the state government of New York and is part of the New York State Education Department. The library is one of the large ...

, accessed May 11, 2016

10 letters written by Grover Cleveland in 1884–86

Media coverage * Other

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is a research library in Washington, D.C., serving as the library and research service for the United States Congress and the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It also administers Copyright law o ...

Grover Cleveland

A bibliography by The

Buffalo History Museum

The Buffalo History Museum (founded as the Buffalo Historical Society, and later named the Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society) is located at 1 Museum Court (formerly 25 Nottingham Court) in Buffalo, New York, just east of Elmwood Avenue an ...

Grover Cleveland Sites in Buffalo, NY

A Google Map developed by The

Buffalo History Museum

The Buffalo History Museum (founded as the Buffalo Historical Society, and later named the Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society) is located at 1 Museum Court (formerly 25 Nottingham Court) in Buffalo, New York, just east of Elmwood Avenue an ...

Index to the Grover Cleveland Papers at the Library of Congress

Essay on Cleveland and each member of his cabinet and First Lady

Miller Center of Public Affairs

"Life Portrait of Grover Cleveland"

from

C-SPAN

Cable-Satellite Public Affairs Network (C-SPAN ) is an American Cable television in the United States, cable and Satellite television in the United States, satellite television network, created in 1979 by the cable television industry as a Non ...

's '' American Presidents: Life Portraits'', August 13, 1999

Interview with H. Paul Jeffers on ''An Honest President: The Life and Presidencies of Grover Cleveland''

''

Booknotes

''Booknotes'' is an American television series on the C-SPAN network hosted by Brian Lamb, which originally aired from 1989 to 2004. The format of the show is a one-hour, one-on-one interview with a non-fiction author. The series was broadcast ...

'' (2000)

*

*

{{Authority control

1880s in the United States

1885 establishments in the United States

1889 disestablishments in the United States

Gilded Age

Thomas A. Hendricks

Cleveland, Grover first