The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the

Korean Peninsula

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically divided at or near the 38th parallel between North Korea (Dem ...

fought between

North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

(Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and

South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the southern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders North Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone, with the Yellow Sea to the west and t ...

(Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was supported by

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

and the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, while South Korea was supported by the

United Nations Command

United Nations Command (UNC or UN Command) is the multinational military force established to support the South Korea, Republic of Korea (South Korea) during and after the Korean War. It was the first attempt at collective security by the U ...

(UNC) led by the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

. The conflict was one of the first major

proxy war

In political science, a proxy war is an armed conflict where at least one of the belligerents is directed or supported by an external third-party power. In the term ''proxy war'', a belligerent with external support is the ''proxy''; both bel ...

s of the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

. Fighting ended in 1953 with an

armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from t ...

but no

peace treaty

A peace treaty is an treaty, agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually country, countries or governments, which formally ends a declaration of war, state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an ag ...

, leading to the ongoing

Korean conflict

The Korean conflict is an List of ongoing armed conflicts, ongoing conflict based on the division of Korea between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) and South Korea (Republic of Korea), both of which claim to be the sole Legit ...

.

After the end of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

in 1945, Korea, which had been a

Japanese colony for 35 years, was

divided

Division is one of the four basic operations of arithmetic. The other operations are addition, subtraction, and multiplication. What is being divided is called the ''dividend'', which is divided by the ''divisor'', and the result is called the ...

by the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and the United States into two occupation zones at the

38th parallel, with plans for a future independent state. Due to political disagreements and influence from their backers, the zones formed their governments in 1948. North Korea was led by

Kim Il Sung

Kim Il Sung (born Kim Song Ju; 15 April 1912 – 8 July 1994) was a North Korean politician and the founder of North Korea, which he led as its first Supreme Leader (North Korean title), supreme leader from North Korea#Founding, its establishm ...

in

Pyongyang

Pyongyang () is the Capital city, capital and largest city of North Korea, where it is sometimes labeled as the "Capital of the Revolution" (). Pyongyang is located on the Taedong River about upstream from its mouth on the Yellow Sea. Accordi ...

, and South Korea by

Syngman Rhee

Syngman Rhee (; 26 March 1875 – 19 July 1965), also known by his art name Unam (), was a South Korean politician who served as the first president of South Korea from 1948 to 1960. Rhee was also the first and last president of the Provisiona ...

in

Seoul

Seoul, officially Seoul Special Metropolitan City, is the capital city, capital and largest city of South Korea. The broader Seoul Metropolitan Area, encompassing Seoul, Gyeonggi Province and Incheon, emerged as the world's List of cities b ...

; both claimed to be the sole

legitimate government of all of Korea and engaged in border clashes as internal unrest was fomented by communist groups in the south. On 25 June 1950, the

Korean People's Army

The Korean People's Army (KPA; ) encompasses the combined military forces of North Korea and the armed wing of the Workers' Party of Korea (WPK). The KPA consists of five branches: the Korean People's Army Ground Force, Ground Force, the Ko ...

(KPA), equipped and trained by the Soviets, launched an invasion of the south. In the absence of the Soviet Union's representative, the

UN Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

denounced the attack and

recommended member states to repel the invasion. UN forces comprised 21 countries, with the United States providing around 90% of military personnel.

Seoul was captured by the KPA on 28 June, and by early August, the

Republic of Korea Army

The Republic of Korea Army (ROKA; ), also known as the ROK Army or South Korean Army, is the army of South Korea, responsible for ground-based warfare. It is the largest of the military branches of the Republic of Korea Armed Forces with 365,0 ...

(ROKA) and its allies were nearly defeated, holding onto only the

Pusan Perimeter

The Battle of the Pusan Perimeter, known in Korean as the Battle of the Naktong River Defense Line (), was a large-scale battle between United Nations Command (UN) and North Korean forces lasting from August 4 to September 18, 1950. It was one ...

in the peninsula's southeast. On 15 September, UN forces

landed at Inchon near Seoul, cutting off KPA troops and supply lines. UN forces broke out from the perimeter on 18 September, re-captured Seoul, and

invaded North Korea in October, capturing Pyongyang and advancing towards the

Yalu River

The Yalu River () or Amnok River () is a river on the border between China and North Korea. Together with the Tumen River to its east, and a small portion of Paektu Mountain, the Yalu forms the border between China and North Korea. Its valle ...

—the border with China. On 19 October, the Chinese

People's Volunteer Army

The People's Volunteer Army (PVA), officially the Chinese People's Volunteers (CPV), was the armed expeditionary forces China in the Korean War, deployed by the History of the People's Republic of China (1949–1976), People's Republic of Chi ...

(PVA) crossed the Yalu and

entered the war on the side of the North.

in December, following the PVA's

first

First most commonly refers to:

* First, the ordinal form of the number 1

First or 1st may also refer to:

Acronyms

* Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty-Centimeters, an astronomical survey carried out by the Very Large Array

* Far Infrared a ...

and

second offensive. Communist forces

captured Seoul again in January 1951 before losing it to

a UN counter-offensive two months later. After an abortive

Chinese spring offensive

The Chinese spring offensive (), also known as the Chinese Fifth Phase Offensive (), was a military operation conducted by the Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA) during the Korean War. Mobilizing three field armies totaling 700,000 men for th ...

, UN forces

retook territory roughly up to the 38th parallel. Armistice negotiations began in July 1951, but dragged on as the fighting became a

war of attrition

The War of Attrition (; ) involved fighting between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and their allies from 1967 to 1970.

Following the 1967 Six-Day War, no serious diplomatic efforts were made to resolve t ...

and the North suffered heavy damage

from U.S. bombing.

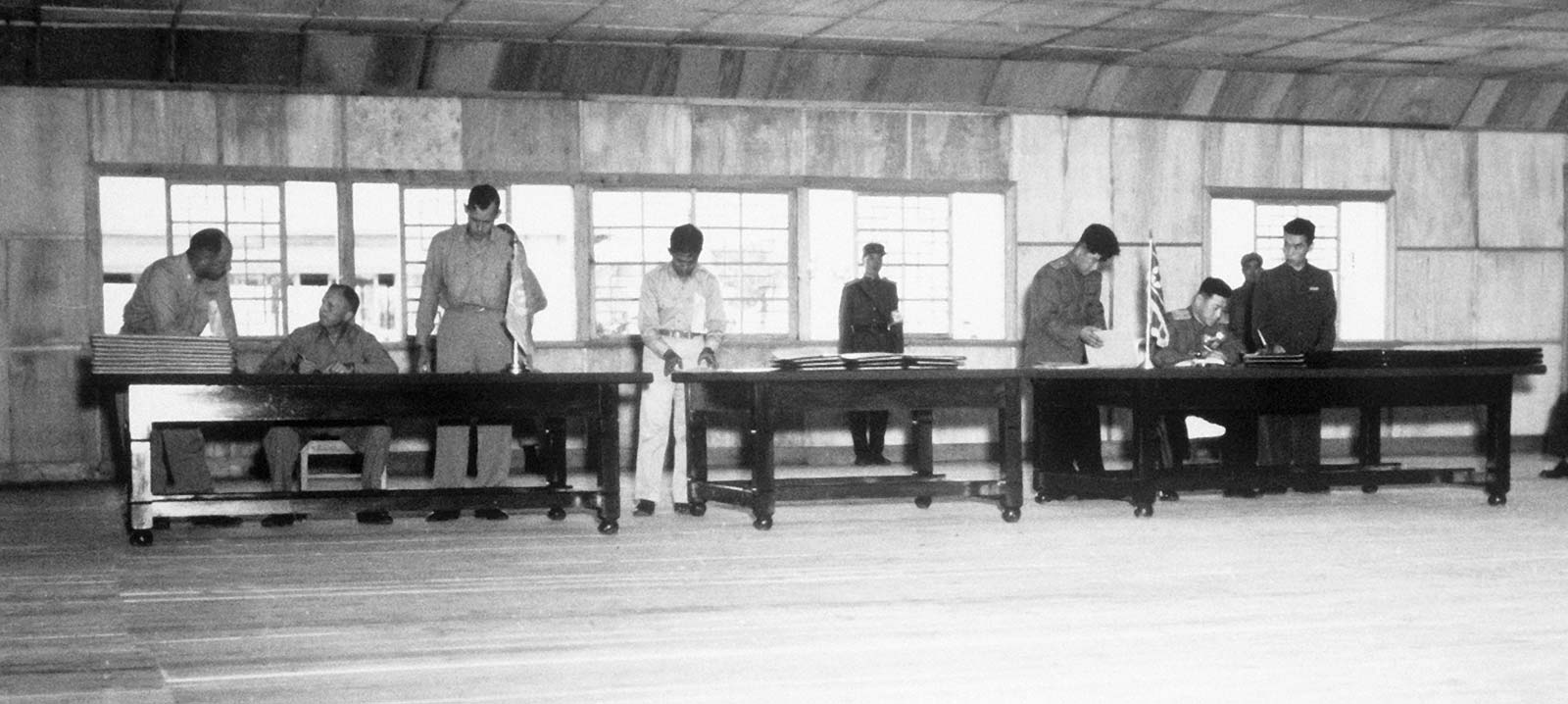

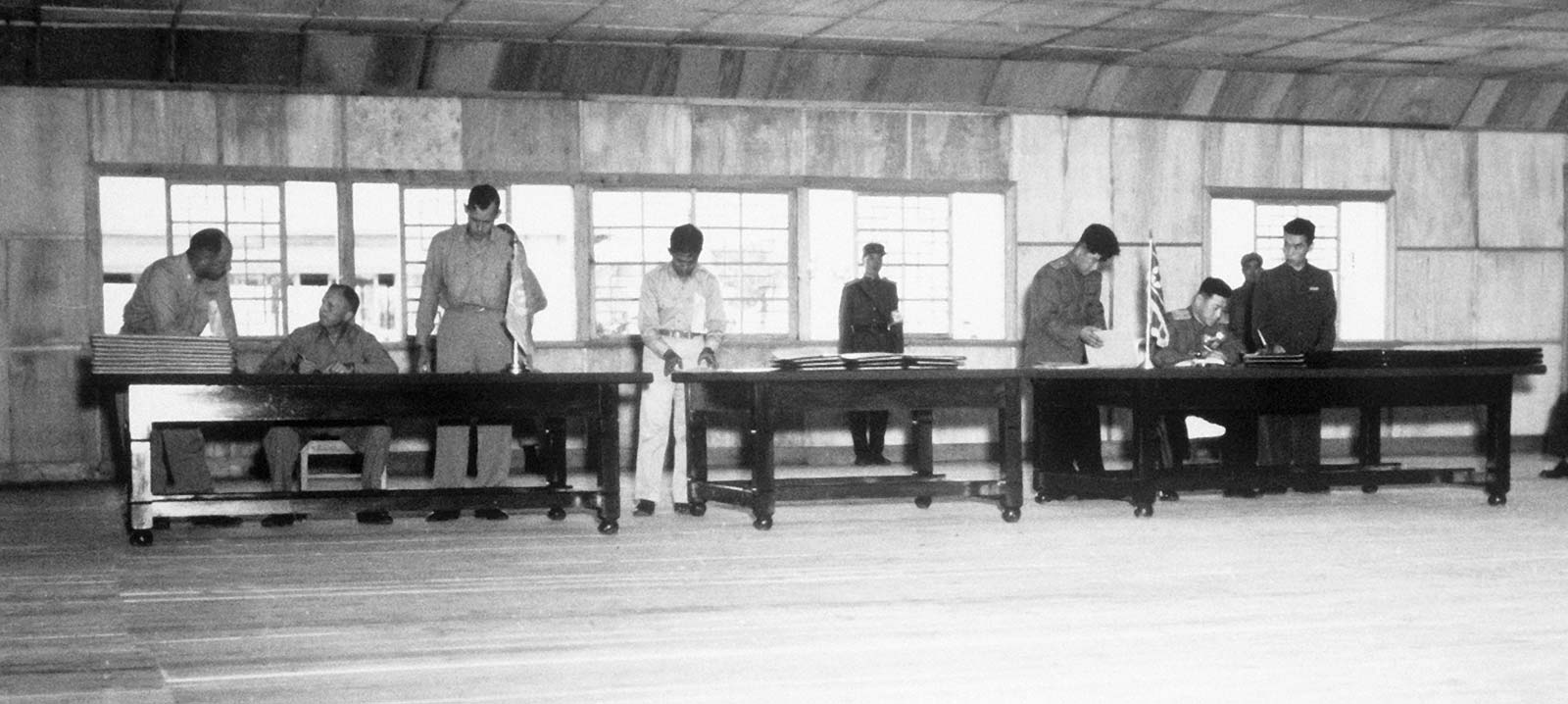

Combat ended on 27 July 1953 with the signing of the

Korean Armistice Agreement

The Korean Armistice Agreement (; zh, t=韓國停戰協定 / 朝鮮停戰協定) is an armistice that brought about a cessation of hostilities of the Korean War. It was signed by United States Army Lieutenant General William Kelly Harrison Jr ...

, which allowed the exchange of prisoners and created a

Demilitarized Zone

A demilitarized zone (DMZ or DZ) is an area in which treaties or agreements between states, military powers or contending groups forbid military installations, activities, or personnel. A DZ often lies along an established frontier or boundary ...

(DMZ) along the frontline, with a

Joint Security Area

The Joint Security Area (JSA, often referred to as the Truce Village or Panmunjom) is the only portion of the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) where North Korea, North and South Korean forces stand face-to-face. The JSA is used by the two Koreas ...

at

Panmunjom

Panmunjom (also spelled Panmunjeom) was a village just north of the ''de facto'' border between North Korea and South Korea, where the 1953 Korean Armistice Agreement that ended the Korean War was signed. It was located in what is now Paju, Gy ...

. The conflict caused more than one million military deaths and an estimated two to three million civilian deaths.

Alleged war crimes include the

mass killing of suspected communists by Seoul and the

mass killing of alleged reactionaries by Pyongyang. North Korea became one of the most heavily bombed countries in history,

and virtually all of Korea's major cities were destroyed.

No peace treaty has been signed, making the war a

frozen conflict

In international relations, a frozen conflict is a situation in which active armed conflict has been brought to an end, but no peace treaty or other political framework resolves the conflict to the satisfaction of the combatants. Therefore, ...

.

Names

In South Korea, the war is usually referred to as the "625 War" (), the "625 Upheaval" (), or simply "625", reflecting the date of its commencement on 25 June.

In North Korea, the war is officially referred to as the ''Fatherland Liberation War'' () or the ''

Chosŏn''

orean''War'' ().

In mainland China, the segment of the war after the intervention of the

People's Volunteer Army

The People's Volunteer Army (PVA), officially the Chinese People's Volunteers (CPV), was the armed expeditionary forces China in the Korean War, deployed by the History of the People's Republic of China (1949–1976), People's Republic of Chi ...

is commonly and officially known as the "Great Movement to Resist America and Assist Korea" (), although the term "''

Chosŏn'' War" () is sometimes used unofficially. The term "''

Hán'' (Korean) War" () is most used in

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

(Republic of China),

Hong Kong

Hong Kong)., Legally Hong Kong, China in international treaties and organizations. is a special administrative region of China. With 7.5 million residents in a territory, Hong Kong is the fourth most densely populated region in the wor ...

and

Macau

Macau or Macao is a special administrative regions of China, special administrative region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). With a population of about people and a land area of , it is the most List of countries and dependencies by p ...

.

In the US, the war was initially described by President

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

as a "

police action

In security studies and international relations, a police action is a military action undertaken without a formal declaration of war. In the 21st century, the term has been largely supplanted by " counter-insurgency". Since World War II, formal ...

" as the US never formally declared war and the operation was conducted under the auspices of the UN.

It has sometimes been referred to in the

English-speaking world

The English-speaking world comprises the 88 countries and territories in which English language, English is an official, administrative, or cultural language. In the early 2000s, between one and two billion people spoke English, making it the ...

as "The Forgotten War" or "The Unknown War" because of the lack of public attention it received relative to World War II and the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

.

Background

Imperial Japanese rule (1910–1945)

The

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

diminished the influence of

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

over Korea in the

First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 189417 April 1895), or the First China–Japan War, was a conflict between the Qing dynasty of China and the Empire of Japan primarily over influence in Joseon, Korea. In Chinese it is commonly known as th ...

(1894–95). A decade later, after defeating

Imperial Russia

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor/empress, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* ...

in the

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

, Japan made the Korean Empire its

protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over ...

with the

Eulsa Treaty in 1905, then annexed it with the

Japan–Korea Treaty of 1910

The Japan–Korea Treaty of 1910, also known as the Japan–Korea Annexation Treaty, was made by representatives of the Empire of Japan and the Korean Empire on 22 August 1910. In this treaty, Japan formally annexed Korea following the J ...

.

Many

Korean nationalists

Korean may refer to:

People and culture

* Koreans, people from the Korean peninsula or of Korean descent

* Korean culture

* Korean language

**Korean alphabet, known as Hangul or Korean

**Korean dialects

**See also: North–South differences in t ...

fled the country. The

Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea

The Korean Provisional Government (KPG), formally the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea (), was a Korean government-in-exile based in Republic of China (1912–1949), China during Korea under Japanese rule, Japanese rule over K ...

was founded in 1919 in

Nationalist China. It failed to achieve international recognition, failed to unite the nationalist groups, and had a fractious relationship with its US-based founding president,

Syngman Rhee

Syngman Rhee (; 26 March 1875 – 19 July 1965), also known by his art name Unam (), was a South Korean politician who served as the first president of South Korea from 1948 to 1960. Rhee was also the first and last president of the Provisiona ...

.

In China, the nationalist

National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA; zh, labels=no, t=國民革命軍) served as the military arm of the Kuomintang, Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, or KMT) from 1924 until 1947.

From 1928, it functioned as the regular army, de facto ...

and the communist

People's Liberation Army

The People's Liberation Army (PLA) is the military of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the People's Republic of China (PRC). It consists of four Military branch, services—People's Liberation Army Ground Force, Ground Force, People's ...

(PLA) helped organize Korean refugees against the Japanese military, which had also occupied parts of China. The Nationalist-backed Koreans, led by

Yi Pom-Sok

Lee Beom-seok (; October 20, 1900 – May 11, 1972), also known by his art name Cheolgi, was a Korean independence activist who served as the prime minister of South Korea from 1948 to 1950. He also headed the Korean National Youth Association. ...

, fought in the

Burma campaign

The Burma campaign was a series of battles fought in the British colony of British rule in Burma, Burma as part of the South-East Asian theatre of World War II. It primarily involved forces of the Allies of World War II, Allies (mainly from ...

(1941–45). The communists, led by, among others,

Kim Il Sung

Kim Il Sung (born Kim Song Ju; 15 April 1912 – 8 July 1994) was a North Korean politician and the founder of North Korea, which he led as its first Supreme Leader (North Korean title), supreme leader from North Korea#Founding, its establishm ...

, fought the Japanese in Korea and

Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

. At the

Cairo Conference

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

in 1943, China, the UK, and the US decided that "in due course, Korea shall become free and independent".

Korea divided (1945–1949)

At the

Tehran Conference

The Tehran Conference (codenamed Eureka) was a strategy meeting of the Allies of World War II, held between Joseph Stalin, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943. It was the first of the Allied World Wa ...

in 1943 and the

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (), held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the postwar reorganization of Germany and Europe. The three sta ...

in February 1945, the Soviet Union promised to join its

allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

in the

Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

within three months of the

victory in Europe

Victory in Europe Day is the day celebrating the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Germany's unconditional surrender of its armed forces on Tuesday, 8 May 1945; it marked the official surrender of all German military operations ...

.

The USSR declared war on Japan and

invaded Manchuria on 8 August 1945.

On 10 August, Soviet forces entered northern Korea and secured most major cities in the north by 24 August.

Japanese resistance was light.

Having fought Japan on Korean soil, the Soviet forces were well-received by Koreans.

On 10 August in

Washington

Washington most commonly refers to:

* George Washington (1732–1799), the first president of the United States

* Washington (state), a state in the Pacific Northwest of the United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A ...

, US Colonels

Dean Rusk

David Dean Rusk (February 9, 1909December 20, 1994) was the United States secretary of state from 1961 to 1969 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, the second-longest serving secretary of state after Cordell Hull from the ...

and

Charles H. Bonesteel III were assigned to divide Korea into Soviet and

US occupation zones and proposed the

38th parallel as the dividing line. This was incorporated into the US

General Order No. 1

General Order No. 1 for the surrender of Japan was prepared by the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff and approved by President Harry Truman on August 17, 1945.

It was issued by General Douglas MacArthur to the representative of the Empire of J ...

, which responded to the

Japanese surrender

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, ending the war. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) was incapable of condu ...

on 15 August. Explaining the choice of the 38th parallel, Rusk observed, "Even though it was further north than could be realistically reached by U. S.

'sic''forces in the event of Soviet disagreement ... we felt it important to include the capital of Korea in the area of responsibility of American troops".

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

, however, maintained his wartime policy of cooperation, and on 16 August, the Red Army halted at the 38th parallel for three weeks to await the arrival of US forces.

On 7 September 1945, General

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

issued Proclamation No. 1 to the people of Korea, announcing US military control over Korea south of the 38th parallel and establishing English as the official language during military control. On 8 September, US Lieutenant General

John R. Hodge

General John Reed Hodge (12 June 1893 – 12 November 1963) was an American military officer of the United States Army. Hodge commanded Operation Blacklist Forty in 1945. He served as the governor of the American military government in Korea fr ...

arrived in

Incheon

Incheon is a city located in northwestern South Korea, bordering Seoul and Gyeonggi Province to the east. Inhabited since the Neolithic, Incheon was home to just 4,700 people when it became an international port in 1883. As of February 2020, ...

to accept the Japanese surrender south of the 38th parallel. Appointed as military governor, Hodge directly controlled South Korea as head of the

United States Army Military Government in Korea

The United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK) was the official ruling body of the southern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula from 9 September 1945 to 15 August 1948.

The country during this period was plagued with political a ...

(USAMGIK 1945–48).

In December 1945, Korea was administered by the

US–Soviet Union Joint Commission, as agreed at the

Moscow Conference, to grant independence after a five-year trusteeship. Waiting five years for independence was unpopular among Koreans, and riots broke out.

The Communist Party supported the trusteeship, while

Kim Ku

Kim Ku (; August 29, 1876 – June 26, 1949), also known by his art name Paekpŏm, was a Korean independence activist and statesman. He was a leader of the Korean independence movement against the Empire of Japan, head of the Provisional Gove ...

and

Syngman Rhee

Syngman Rhee (; 26 March 1875 – 19 July 1965), also known by his art name Unam (), was a South Korean politician who served as the first president of South Korea from 1948 to 1960. Rhee was also the first and last president of the Provisiona ...

led the anti-trusteeship movement against both the

U.S. military government and the

Soviet military administration. To contain them, the USAMGIK banned strikes on 8 December and outlawed the

PRK Revolutionary Government and People's Committees on 12 December. Following further civilian unrest, the USAMGIK declared

martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

.

Citing the inability of the Joint Commission to make progress, the UN decided to hold an election under UN auspices to create an independent Korea, as stated in UN General Assembly Resolution 112. The Soviet authorities and Korean communists refused to participate in the election. The final attempt to establish a unified government was thwarted by North Korea's refusal. Due to concerns about division caused by an election without North Korea's participation, many South Korean politicians boycotted it. The

1948 South Korean general election was held in May.

The resultant South Korean government promulgated a national political constitution on 17 July and elected Syngman Rhee as

president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

on 20 July. The Republic of Korea (South Korea) was established on 15 August 1948.

In the Soviet-Korean Zone of Occupation, the Soviets agreed to the establishment of a communist government led by Kim Il Sung.

The

1948 North Korean parliamentary election

Parliamentary elections were held in North Korea on 25 August 1948 to elect the members of the 1st Supreme People's Assembly. Organised by the People's Committee of North Korea, the elections saw 572 deputies elected, of which 212 were from Nor ...

s took place in August. The Soviet Union withdrew its forces in 1948 and the US in 1949.

Chinese Civil War (1945–1949)

With the end of the

war with Japan, the

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led Nationalist government, government of the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China and the forces of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Armed conflict continued intermitt ...

resumed in earnest between the

Communists

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, d ...

and the

Nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

-led government. While the Communists were struggling for supremacy in Manchuria, they were supported by the North Korean government with

matériel

Materiel or matériel (; ) is supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

Military

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers eith ...

and manpower. According to Chinese sources, the North Koreans donated 2,000 railway cars worth of supplies while thousands of Koreans served in the Chinese PLA during the war. North Korea also provided the Chinese Communists in

Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

with a safe refuge for non-combatants and communications with the rest of China. As a token of gratitude, between 50,000 and 70,000 Korean veterans who served in the PLA were sent back along with their weapons, and they later played a significant role in the initial invasion of South Korea. China promised to support the North Koreans in the event of a war against South Korea.

Communist insurgency in South Korea (1948–1950)

By 1948, a North Korea-backed insurgency had broken out in the southern half of the peninsula. This was exacerbated by the undeclared border war between the Koreas, which saw division-level engagements and thousands of deaths on both sides. The ROK was almost entirely trained and focused on counterinsurgency, rather than conventional warfare. They were equipped and advised by a force of a few hundred American officers, who were successful in helping the ROKA to subdue guerrillas and hold its own against

North Korean military (Korean People's Army, KPA) forces along the 38th parallel.

[Bryan, p. 76.] Approximately 8,000 South Korean soldiers and police officers died in the insurgent war and border clashes.

The

first socialist uprising occurred without direct North Korean participation, though the guerrillas still professed support for the northern government. Beginning in April 1948 on

Jeju Island

Jeju Island (Jeju language, Jeju/) is South Korea's largest island, covering an area of , which is 1.83% of the total area of the country. Alongside outlying islands, it is part of Jeju Province and makes up the majority of the province.

The i ...

, the campaign saw arrests and repression by the South Korean government in the fight against the South Korean Labor Party, resulting in 30,000 violent deaths, among them 14,373 civilians, of whom ~2,000 were killed by rebels and ~12,000 by ROK security forces. The

Yeosu–Suncheon rebellion

The Yeosu-Suncheon rebellion, also known as the Yeo-Sun incident (Yeo-Sun an abbreviation of ''Yeosu'' and ''Suncheon''), was a rebellion that began in October 1948 and mostly ended by November of the same year. However, pockets of resistance l ...

overlapped with it, as several thousand army defectors waving red flags massacred right-leaning families. This resulted in another brutal suppression by the government and between 2,976 and 3,392 deaths. By May 1948, both uprisings had been crushed.

Insurgency reignited in the spring of 1949 when attacks by guerrillas in the mountainous regions (buttressed by army defectors and North Korean agents) increased. Insurgent activity peaked in late 1949 as the ROKA engaged so-called People's Guerrilla Units. Organized and armed by the North Korean government, and backed by 2,400 KPA commandos who had infiltrated through the border, these guerrillas launched an offensive in September aimed at undermining the South Korean government and preparing the country for the KPA's arrival in force. This offensive failed. However, the guerrillas were now entrenched in the Taebaek-san region of the

North Gyeongsang Province

North Gyeongsang Province (, ) is a province in eastern South Korea, and with an area of , it is the largest province in the Korean peninsula. The province was formed in 1896 from the northern half of the former Gyeongsang province, and remaine ...

and the border areas of the

Gangwon Province.

[Bryan, p. 78.]

While the insurgency was ongoing, the ROKA and KPA engaged in battalion-sized battles along the border, starting in May 1949.

Border clashes between South and North continued on 4 August 1949, when thousands of North Korean troops attacked South Korean troops occupying territory north of the 38th parallel. The 2nd and 18th ROK Infantry Regiments repulsed attacks in Kuksa-bong, and KPA troops were "completely routed". Border incidents decreased by the start of 1950.

Meanwhile, counterinsurgencies in the South Korean interior intensified; persistent operations, paired with worsening weather, denied the guerrillas sanctuary and wore away their fighting strength. North Korea responded by sending more troops to link up with insurgents and build more partisan cadres; North Korean infiltrators had reached 3,000 soldiers in 12 units by the start of 1950, but all were destroyed or scattered by the ROKA.

On 1 October 1949, the ROKA launched a three-pronged assault on the insurgents in

South Cholla and

Taegu

Daegu (; ), formerly spelled Taegu and officially Daegu Metropolitan City (), is a city in southeastern South Korea. It is the third-largest urban agglomeration in South Korea after Seoul and Busan; the fourth-largest List of provincial-level ci ...

. By March 1950, the ROKA claimed 5,621 guerrillas killed or captured and 1,066 small arms seized. This operation crippled the insurgency. Soon after, North Korea made final attempts to keep the uprising active, sending battalion-sized units of infiltrators under the commands of Kim Sang-ho and Kim Moo-hyon. The first battalion was reduced to a single man over the course of engagements by the ROKA

8th Division. The second was annihilated by a two-battalion

hammer-and-anvil maneuver by units of the ROKA

6th Division, resulting in a toll of 584 KPA guerrillas (480 killed, 104 captured) and 69 ROKA troops killed, plus 184 wounded. By the spring of 1950, guerrilla activity had mostly subsided; the border, too, was calm.

Prelude to war (1950)

By 1949, South Korean and US military actions had reduced indigenous communist guerrillas in the South from 5,000 to 1,000. However, Kim Il Sung believed widespread uprisings had weakened the South Korean military and that a North Korean invasion would be welcomed by much of the South Korean population. Kim began seeking Stalin's support for an invasion in March 1949, traveling to Moscow to persuade him.

Stalin initially did not think the time was right for a war in Korea. PLA forces were still embroiled in the Chinese Civil War, while US forces remained stationed in South Korea. By spring 1950, he believed that the strategic situation had changed: PLA forces under

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

had secured final victory, US forces had withdrawn from Korea, and the Soviets

had detonated their first nuclear bomb, breaking the US monopoly. As the US had not directly intervened to stop the communists in China, Stalin calculated they would be even less willing to fight in Korea, which had less strategic significance. The Soviets had cracked the codes used by the US to communicate with their

embassy in Moscow, and reading dispatches convinced Stalin that Korea did not have the importance to the US that would warrant a nuclear confrontation. Stalin began a more aggressive strategy in Asia based on these developments, including promising economic and military aid to China through the

.

In April 1950, Stalin permitted Kim to attack the government in the South, under the condition that Mao would agree to send reinforcements if needed. For Kim, this was the fulfillment of his goal to unite Korea. Stalin made it clear Soviet forces would not openly engage in combat, to avoid a direct war with the United States.

Kim met with Mao in May 1950 and differing historical interpretations of the meeting have been put forward. According to Barbara Barnouin and Yu Changgeng, Mao agreed to support Kim despite concerns of American intervention, as China desperately needed the economic and military aid promised by the Soviets. Kathryn Weathersby cites Soviet documents which said Kim secured Mao's support. Along with Mark O'Neill, she says this accelerated Kim's war preparations.

Chen Jian argues Mao never seriously challenged Kim's plans and Kim had every reason to inform Stalin that he had obtained Mao's support.

Citing more recent scholarship,

Zhao Suisheng contends Mao did not approve of Kim's war proposal and requested verification from Stalin, who did so via a telegram.

Mao accepted the decision made by Kim and Stalin to unify Korea but cautioned Kim over possible US intervention.

[

Soviet generals with extensive combat experience from World War II were sent to North Korea as the Soviet Advisory Group. They completed plans for attack by May and called for a skirmish to be initiated in the ]Ongjin Peninsula

Ongjin County () is a county in southern South Hwanghae Province, North Korea. It is located on the Ongjin Peninsula, which projects into the Yellow Sea.

History

The Ongjin Peninsula lies below the 38th parallel, and was therefore in the Sout ...

on the west coast of Korea. The North Koreans would then launch an attack to capture Seoul and encircle and destroy the ROK. The final stage would involve destroying South Korean government remnants and capturing the rest of South Korea, including the ports.

On 7 June 1950, Kim called for a Korea-wide election on 5–8 August 1950 and a consultative conference in Haeju

Haeju () is a city located in South Hwanghae Province near Haeju Bay in North Korea. It is the administrative centre of South Hwanghae Province. As of 2008, the population of the city is estimated to be 273,300. At the beginning of the 20th centu ...

on 15–17 June. On 11 June, the North sent three diplomats to the South as a peace overture, which Rhee rejected outright. On 21 June, Kim revised his war plan to involve a general attack across the 38th parallel, rather than a limited operation in Ongjin. Kim was concerned that South Korean agents had learned about the plans and that South Korean forces were strengthening their defenses. Stalin agreed to this change.

While these preparations were underway in the North, there were clashes along the 38th parallel, especially at Kaesong

Kaesong (, ; ) is a special city in the southern part of North Korea (formerly in North Hwanghae Province), and the capital of Korea during the Taebong kingdom and subsequent Goryeo dynasty. The city is near the Kaesong Industrial Region cl ...

and Ongjin, many initiated by the South. The ROK was being trained by the US Korean Military Advisory Group

The Korean Military Advisory Group (KMAG) (officially United States Military Advisory Group to the Republic of Korea) was a United States military unit of the Korean War. It helped to train and provide logistic support for the Republic of Korea A ...

(KMAG). On the eve of the war, KMAG commander General William Lynn Roberts voiced utmost confidence in the ROK and boasted that any North Korean invasion would merely provide "target practice". For his part, Syngman Rhee repeatedly expressed his desire to conquer the North, including when US diplomat John Foster Dulles

John Foster Dulles (February 25, 1888 – May 24, 1959) was an American politician, lawyer, and diplomat who served as United States secretary of state under President Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 until his resignation in 1959. A member of the ...

visited Korea on 18 June.

Though some South Korean and US intelligence officers predicted an attack, similar predictions had been made before and nothing had happened. The Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

noted the southward movement by the KPA but assessed this as a "defensive measure" and concluded an invasion was "unlikely". On 23 June UN observers inspected the border and did not detect that war was imminent.

Comparison of forces

Chinese involvement was extensive from the beginning, building on previous collaboration between the Chinese and Korean communists during the Chinese Civil War. Throughout 1949 and 1950, the Soviets continued arming North Korea. After the communist victory in the Chinese Civil War, ethnic Korean units in the PLA were sent to North Korea.

In the fall of 1949, two PLA divisions composed mainly of Korean-Chinese troops (the 164th and 166th) entered North Korea, followed by smaller units throughout the rest of 1949. The reinforcement of the KPA with PLA veterans continued into 1950, with the 156th Division and several other units of the former Fourth Field Army arriving in February; the PLA 156th Division was reorganized as the KPA 7th Division. By mid-1950, between 50,000 and 70,000 former PLA troops had entered North Korea, forming a significant part of the KPA's strength on the eve of the war's beginning. The combat veterans and equipment from China, the tanks, artillery, and aircraft supplied by the Soviets, and rigorous training increased North Korea's military superiority over the South, armed by the U.S. military with mostly small arms, but no heavy weaponry.

Several generals, such as Lee Kwon-mu

Lee Kwon-mu (; 1914–1986), also known as Yi Kwon-mu or Ri Gwon-mu, was a North Korean general officer during the Korean War. He commanded a division, and later a corps, on the front line of the conflict and received North Korea's two highest ...

, were PLA veterans born to ethnic Koreans in China. While older histories of the conflict often referred to these ethnic Korean PLA veterans as being sent from northern Korea to fight in the Chinese Civil War before being sent back, recent Chinese archival sources studied by Kim Donggill indicate that this was not the case. Rather, the soldiers were indigenous to China, as part of China's longstanding ethnic Korean community, and were recruited to the PLA in the same way as any other Chinese citizen.

According to the first official census in 1949, the population of North Korea numbered 9,620,000, and by mid-1950, North Korean forces numbered between 150,000 and 200,000 troops, organized into 10 infantry divisions, one tank division, and one air force division, with 210 fighter planes and 280 tanks, who captured scheduled objectives and territory, among them Kaesong, Chuncheon

Chuncheon (; ; literally ''spring river''), formerly romanized as Ch'unch'ŏn, is the capital of Gangwon Province, South Korea. The city lies in the north of the country, located in a basin formed by the Soyang River and Han River (Korea), Han R ...

, Uijeongbu

Uijeongbu (; ) is a Administrative divisions of South Korea, city in Gyeonggi Province, South Korea. It is the tenth-most populous city in the province and a suburb of Seoul within the greater Seoul Metropolitan Area.

History

Uijeongbu was estab ...

, and Ongjin. Their forces included 274 T-34-85

The T-34 is a Soviet medium tank from World War II. When introduced, its 76.2 mm (3 in) tank gun was more powerful than many of its contemporaries, and its 60-degree sloped armour provided good protection against Anti-tank warfare, ...

tanks, 200 artillery pieces, 110 attack bombers, 150 Yak

The yak (''Bos grunniens''), also known as the Tartary ox, grunting ox, hairy cattle, or domestic yak, is a species of long-haired domesticated cattle found throughout the Himalayan region, the Tibetan Plateau, Tajikistan, the Pamir Mountains ...

fighter planes, and 35 reconnaissance aircraft. In addition to the invasion force, the North had 114 fighters, 78 bombers, 105 T-34-85 tanks, and some 30,000 soldiers stationed in reserve in North Korea. Although each navy consisted of only several small warships, the North and South Korean navies fought in the war as seaborne artillery for their armies.

In contrast, the South Korean population was estimated at 20 million,

Course of the war

Operation Pokpung

At dawn on 25 June 1950, the KPA crossed the 38th parallel behind artillery fire. It justified its assault with the claim ROK troops attacked first and that the KPA were aiming to arrest and execute the "bandit traitor Syngman Rhee". Fighting began on the strategic Ongjin Peninsula in the west. There were initial South Korean claims that the 17th Regiment had counterattacked at Haeju; some scholars argue the claimed counterattack was instead the instigating attack, and therefore that the South Koreans may have fired first. However, the report that contained the Haeju claim contained errors and outright falsehoods.

KPA forces attacked all along the 38th parallel within an hour. The KPA had a combined arms force including tanks supported by heavy artillery. The ROK had no tanks, anti-tank weapons, or heavy artillery. The South Koreans committed their forces in a piecemeal fashion, and these were routed in a few days.

On 27 June, Rhee evacuated Seoul with some of the government. At 02:00 on 28 June the ROK blew up the Hangang Bridge across the Han River in an attempt to stop the KPA. The bridge was detonated while 4,000 refugees were crossing it, and hundreds were killed.United Nations Command

United Nations Command (UNC or UN Command) is the multinational military force established to support the South Korea, Republic of Korea (South Korea) during and after the Korean War. It was the first attempt at collective security by the U ...

.

Factors in U.S. intervention

The Truman administration

Harry S. Truman's tenure as the List of presidents of the United States, 33rd president of the United States began on April 12, 1945, upon the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and ended on January 20, 1953. He had been Vice President ...

was unprepared for the invasion. Korea was not included in the strategic Asian Defense Perimeter outlined by United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state (SecState) is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State.

The secretary of state serves as the principal advisor to the ...

Dean Acheson

Dean Gooderham Acheson ( ; April 11, 1893October 12, 1971) was an American politician and lawyer. As the 51st United States Secretary of State, U.S. Secretary of State, he set the foreign policy of the Harry S. Truman administration from 1949 to ...

. Military strategists were more concerned with the security of Europe against the Soviet Union than that of East Asia

East Asia is a geocultural region of Asia. It includes China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan, plus two special administrative regions of China, Hong Kong and Macau. The economies of Economy of China, China, Economy of Ja ...

. The administration was worried a war in Korea could quickly escalate without American intervention. Diplomat John Foster Dulles stated: "To sit by while Korea is overrun by unprovoked armed attack would start a disastrous chain of events leading most probably to world war."

While there was hesitance by some in the US government to get involved, considerations about Japan fed into the decision to engage on behalf of South Korea. After the fall of China to the communists, US experts saw Japan as the region's counterweight to the Soviet Union and China. While there was no US policy dealing with South Korea directly as a national interest, its proximity to Japan increased its importance. Said Kim: "The recognition that the security of Japan required a non-hostile Korea led directly to President Truman's decision to intervene ... The essential point ... is that the American response to the North Korean attack stemmed from considerations of U.S. policy toward Japan."

Another consideration was the Soviet reaction if the US intervened. The Truman administration was fearful the Korean War was a diversionary assault that would escalate to a general war in Europe once the US committed in Korea. At the same time, " ere was no suggestion from anyone that the United Nations or the United States could back away from he conflict. Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

—a possible Soviet target because of the Tito-Stalin split—was vital to the defense of Italy and Greece, and the country was first on the list of the National Security Council

A national security council (NSC) is usually an executive branch governmental body responsible for coordinating policy on national security issues and advising chief executives on matters related to national security. An NSC is often headed by a n ...

's post-North Korea invasion list of "chief danger spots".

United Nations Security Council resolutions

On 25 June 1950, the United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

unanimously condemned the North Korean invasion of South Korea with Resolution 82. The Soviet Union, a veto-wielding power, had boycotted Council meetings since January 1950, protesting Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

's occupation of China's permanent seat. The Security Council, on 27 June 1950, published Resolution 83 recommending member states provide military assistance to the Republic of Korea. On 27 June President Truman ordered U.S. air and sea forces to help. On 4 July the Soviet deputy foreign minister accused the U.S. of starting armed intervention on behalf of South Korea.UN Charter

The Charter of the United Nations is the foundational treaty of the United Nations (UN). It establishes the purposes, governing structure, and overall framework of the United Nations System, UN system, including its United Nations System#Six ...

Article 32; and the fighting was beyond the Charter's scope, because the initial North–South border fighting was classed as a civil war. Because the Soviet Union was boycotting the Security Council, some legal scholars posited that deciding upon this type of action required the unanimous vote of all five permanent members.

United States' response (July–August 1950)

As soon as word of the attack was received, Acheson informed Truman that the North Koreans had invaded South Korea.

As soon as word of the attack was received, Acheson informed Truman that the North Koreans had invaded South Korea.Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

's aggressions in the 1930s, and the mistake of appeasement

Appeasement, in an International relations, international context, is a diplomacy, diplomatic negotiation policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power (international relations), power with intention t ...

must not be repeated.containment

Containment was a Geopolitics, geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''Cordon sanitaire ...

of communism as outlined in the National Security Council Report 68 (NSC 68):

In August 1950, Truman and Acheson obtained the consent of Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

to appropriate $12 billion for military action, equivalent to $ billion in .Omar Bradley

Omar Nelson Bradley (12 February 1893 – 8 April 1981) was a senior Officer (armed forces), officer of the United States Army during and after World War II, rising to the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He wa ...

, Chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, which advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and ...

, was faced with deploying a force that was a shadow of its World War II counterpart.

Acting on Acheson's recommendation, Truman ordered MacArthur, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers

The Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (), or SCAP, was the title held by General Douglas MacArthur during the United States-led Allied occupation of Japan following World War II. It issued SCAP Directives (alias SCAPIN, SCAP Index Number) ...

in Japan, to transfer matériel to the South Korean military, while giving air cover to evacuation of US nationals. Truman disagreed with advisers who recommended unilateral bombing of the North Korean forces and ordered the U.S. Seventh Fleet to protect Taiwan, whose government asked to fight in Korea. The US denied Taiwan's request for combat, lest it provokes retaliation from the PRC. Because the US had sent the Seventh Fleet to "neutralize" the Taiwan Strait

The Taiwan Strait is a strait separating the island of Taiwan and the Asian continent. The strait is part of the South China Sea and connects to the East China Sea to the north. The narrowest part is wide.

Names

Former names of the Tai ...

, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai ( zh, s=周恩来, p=Zhōu Ēnlái, w=Chou1 Ên1-lai2; 5 March 1898 – 8 January 1976) was a Chinese statesman, diplomat, and revolutionary who served as the first Premier of the People's Republic of China from September 1954 unti ...

criticized the UN and US initiatives as "armed aggression on Chinese territory". The US supported the Kuomintang in Burma

The Kuomintang in Burma () or Kuomintang in the Golden Triangle, which was officially known as the Yunnan Province Anti-Communist National Salvation Army () were troops of the Republic of China Army loyal to the Kuomintang that fled from Chin ...

in the hope these KMT forces would harass China from the southwest

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A '' compass rose'' is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west— ...

, thereby diverting Chinese resources from Korea.

The drive south and Pusan (July–September 1950)

The

The Battle of Osan

The Battle of Osan () was the first engagement between the United States and North Korea during the Korean War. On July 5, 1950, Task Force Smith, an American task force of 540 infantry supported by an artillery battery, was moved to Osan, south ...

, the first significant US engagement, involved the 540-soldier Task Force Smith, a small forward element of the 24th Infantry Division flown in from Japan. On 5 July 1950, Task Force Smith attacked the KPA at Osan

Osan (; ) is a Subdivisions of South Korea, city in Gyeonggi Province, South Korea, approximately south of Seoul. The population of the city is around 200,000. The local economy is supported by a mix of agricultural and industrial enterprises.

...

but without weapons capable of destroying KPA tanks. The KPA defeated the US, with 180 American casualties. The KPA progressed southwards, pushing back US forces at Pyongtaek

Pyeongtaek (; ) is a city in Gyeonggi Province, South Korea. Located in the southwestern part of the province, Pyeongtaek was founded as a union of two districts in 1940. It was elevated to city status in 1986 and is home to a South Korean naval b ...

, Chonan, and Chochiwon, forcing the 24th Division's retreat to Taejeon, which the KPA captured in the Battle of Taejon

The Battle of Taejon (16–20 July 1950) was an early battle of the Korean War, between U.S. and North Korean forces. Forces of the United States Army attempted to defend the headquarters of the 24th Infantry Division (United States), 24th Infa ...

. The 24th Division suffered 3,602 dead and wounded and 2,962 captured, including its commander, Major General William F. Dean.

By August, the KPA steadily pushed back the ROK and the Eighth United States Army

The Eighth Army is a U.S. field army which commands all United States Army forces in South Korea. It is headquartered at the Camp Humphreys in the Anjeong-ri of Pyeongtaek, Pyeongtaek, South Korea.[Pusan

Busan (), officially Busan Metropolitan City, is South Korea's second most populous city after Seoul, with a population of over 3.3 million as of 2024. Formerly romanized as Pusan, it is the economic, cultural and educational center of southe ...]

. This perimeter enclosed about 10% of Korea, in a line defined by the Nakdong River

The Nakdong River or Nakdonggang (, ) is the longest river in South Korea, which passes through the major cities of Daegu and Busan. It takes its name from its role as the eastern border of the Gaya confederacy during Three Kingdoms of Korea, Kor ...

.

The KPA purged South Korea's intelligentsia by killing civil servants and intellectuals. On 20 August, MacArthur warned Kim Il Sung he would be held responsible for KPA atrocities.

Kim's early successes led him to predict the war would finish by the end of August. Chinese leaders were more pessimistic. To counter a possible US deployment, Zhou secured a Soviet commitment to have the Soviet Union support Chinese forces with air cover, and he deployed 260,000 soldiers along the Korean border, under the command of Gao Gang

Gao Gang ( zh, s=高岗, w=Kao Kang; 1905 – August 1954) was a Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leader during the Chinese Civil War and the early years of the People's Republic of China (PRC) before he became the victim of the first major purge w ...

. Zhou authorized a topographical survey of Korea and directed Lei Yingfu, Zhou's military adviser in Korea, to analyze the military situation. Lei concluded MacArthur would likely attempt a landing at Incheon. After conferring with Mao that this would be MacArthur's most likely strategy, Zhou briefed Soviet and North Korean advisers of Lei's findings, and issued orders to PLA commanders to prepare for US naval activity in the Korea Strait

The Korea Strait is a strait, sea passage in East Asia between the Korean Peninsula and Japan. It connects the East China Sea, the Yellow Sea and the Sea of Japan in the northwest Pacific Ocean. The strait is split by Tsushima Island into two par ...

.

In the resulting Battle of Pusan Perimeter

The Battle of the Pusan Perimeter, known in Korean as the Battle of the Naktong River Defense Line (), was a large-scale battle between United Nations Command (UN) and North Korean forces lasting from August 4 to September 18, 1950. It was one ...

, UN forces withstood KPA attacks meant to capture the city at the Naktong Bulge, P'ohang-dong, and Taegu

Daegu (; ), formerly spelled Taegu and officially Daegu Metropolitan City (), is a city in southeastern South Korea. It is the third-largest urban agglomeration in South Korea after Seoul and Busan; the fourth-largest List of provincial-level ci ...

. The United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Air force, air service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is one of the six United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Tracing its ori ...

(USAF) interrupted KPA logistics with 40 daily ground support sortie

A sortie (from the French word meaning ''exit'' or from Latin root ''surgere'' meaning to "rise up") is a deployment or dispatch of one military unit, be it an aircraft, ship, or troops, from a strongpoint. The term originated in siege warf ...

s, which destroyed 32 bridges, halting daytime road and rail traffic. KPA forces were forced to hide in tunnels by day and move only at night. To deny military equipment and supplies to the KPA, the USAF destroyed logistics depots, refineries, and harbors, while U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest displacement, at 4.5 million tons in 2021. It has the world's largest aircraft ...

aircraft attacked transport hubs. Consequently, the overextended KPA could not be supplied throughout the south. On 27 August, 67th Fighter Squadron

The 67th Fighter Squadron "Fighting Cocks" is a fighter squadron of the United States Air Force, part of the 18th Operations Group at Kadena Air Base, Japan. The 67th is equipped with the F-15C/D Eagle, and is planned to transition to the F-15EX ...

aircraft mistakenly attacked facilities in Chinese territory, and the Soviet Union called the Security Council's attention to China's complaint about the incident. The US proposed a commission of India and Sweden determine what the US should pay in compensation, but the Soviets vetoed this.

Meanwhile, US garrisons in Japan continually dispatched soldiers and military supplies to reinforce defenders in the Pusan Perimeter. MacArthur went so far as to call for Japan's rearmament.port of San Francisco

The port of San Francisco is a semi-independent organization that oversees the port facilities at San Francisco, California, United States. It is run by a five-member commission, appointed by the mayor subject to confirmation by a majority of the ...

to the port of Pusan

The port of Busan is the largest port in South Korea, located in the city of Busan, South Korea. Its location is known as Busan Harbour.

The port is ranked sixth in the world's container throughput and is the largest seaport in South Korea. The ...

, the largest Korean port. By late August, the Pusan Perimeter had 500 medium tanks battle-ready. In early September 1950, UN forces outnumbered the KPA 180,000 to 100,000 soldiers.

Battle of Incheon (September 1950)

Against the rested and rearmed Pusan Perimeter defenders and their reinforcements, the KPA were undermanned and poorly supplied; unlike the UN, they lacked naval and air support. To relieve the Pusan Perimeter, MacArthur recommended an amphibious landing

Amphibious warfare is a type of offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the operations were conducted ...

at Incheon, near Seoul, well over behind the KPA lines. On 6 July, he ordered Major General Hobart R. Gay, commander of the U.S. 1st Cavalry Division, to plan an amphibious landing at Incheon; on 12–14 July, the 1st Cavalry Division embarked from Yokohama

is the List of cities in Japan, second-largest city in Japan by population as well as by area, and the country's most populous Municipalities of Japan, municipality. It is the capital and most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a popu ...

, Japan, to reinforce the 24th Infantry Division inside the Pusan Perimeter.the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense, in Arlington County, Virginia, across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. The building was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As ...

opposed him. When authorized, he activated a combined US Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of the United Stat ...

and Marine Corps

Marines (or naval infantry) are military personnel generally trained to operate on both land and sea, with a particular focus on amphibious warfare. Historically, the main tasks undertaken by marines have included raiding ashore (often in supp ...

, and ROK force. The X Corps 10th Corps, Tenth Corps, or X Corps may refer to:

France

* 10th Army Corps (France)

* X Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

Germany

* X Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Army

* ...

, consisted of 40,000 troops of the 1st Marine Division

The 1st Marine Division (1st MARDIV) is a Marine (military), Marine Division (military), division of the United States Marine Corps headquartered at Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, California. It is the ground combat element of the I Marine E ...

, the 7th Infantry Division and around 8,600 ROK soldiers. By 15 September, the amphibious force faced few KPA defenders at Incheon: military intelligence, psychological warfare

Psychological warfare (PSYWAR), or the basic aspects of modern psychological operations (PsyOp), has been known by many other names or terms, including Military Information Support Operations ( MISO), Psy Ops, political warfare, "Hearts and Mi ...

, guerrilla

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, Partisan (military), partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include Children in the military, recruite ...

reconnaissance, and protracted bombardment facilitated a light battle. However, the bombardment destroyed most of Incheon.

Breakout from the Pusan Perimeter

On 16 September Eighth Army began its breakout from the Pusan Perimeter. Task Force Lynch, 3rd Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment

The 7th Cavalry Regiment is a United States Army cavalry regiment formed in 1866. Its official nickname is "Garryowen", after the Irish air " Garryowen" that was adopted as its march tune. The regiment participated in some of the largest ba ...

, and 70th Tank Battalion units advanced through of KPA territory to join the 7th Infantry Division at Osan on 27 September.Pyongyang

Pyongyang () is the Capital city, capital and largest city of North Korea, where it is sometimes labeled as the "Capital of the Revolution" (). Pyongyang is located on the Taedong River about upstream from its mouth on the Yellow Sea. Accordi ...

vulnerable. During the retreat, only 25,000-30,000 KPA soldiers managed to reach the KPA lines.Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

, where he condemned the incompetence of the KPA command and held Soviet military advisers responsible for the defeat.

UN forces invade North Korea (September–October 1950)

On 27 September, MacArthur received secret National Security Council Memorandum 81/1 from Truman reminding him operations north of the 38th parallel was authorized only if "at the time of such operation there was no entry into North Korea by major Soviet or Chinese Communist forces, no announcements of intended entry, nor a threat to counter our operations militarily".encirclement campaigns

The encirclement campaigns of the Chinese Civil War were Republic of China (ROC) offensives against Chinese Communist Party (CCP) revolutionary base areas in China from the late-1920s to 1934 during the Chinese Civil War.

The climax were the fiv ...

in the 1930s, but KPA commanders did not use these tactics effectively. Bruce Cumings

Bruce Cumings (born September 5, 1943) is an American historian of East Asia, professor, lecturer and author. He is the Gustavus F. and Ann M. Swift Distinguished Service Professor in History, and the former chair of the history department at ...

argues, however, that the KPA's rapid withdrawal was strategic, with troops melting into the mountains from where they could launch guerrilla raids on the UN forces spread out on the coasts.

By 1 October, the UN Command had driven the KPA past the 38th parallel, and RoK forces pursued the KPA northwards. MacArthur demanded the KPA's unconditional surrender. On 7 October, with UN authorization, the UN Command forces followed the ROK forces northwards. The Eighth US Army drove up western Korea and captured Pyongyang on 19 October. On 20 October, the US 187th Airborne Regiment made their first of their two combat jumps during the war at Sunchon and Sukchon. The mission was to cut the road north to China, prevent North Korean leaders from escaping Pyongyang, and rescue US prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

.

At month's end, UN forces held 135,000 KPA prisoners of war. As they neared the Sino-Korean border, the UN forces in the west were divided from those in the east by of mountainous terrain. In addition to the 135,000 captured, the KPA had suffered some 200,000 soldiers killed or wounded, for a total of 335,000 casualties since the end of June 1950, and lost 313 tanks. A mere 25,000 KPA regulars retreated across the 38th parallel, as their military had collapsed. The UN forces on the peninsula numbered 229,722 combat troops (including 125,126 Americans and 82,786 South Koreans), 119,559 rear area troops, and 36,667 US Air Force personnel. MacArthur believed it necessary to extend the war into China to destroy depots supplying the North Korean effort. Truman disagreed and ordered caution at the Sino-Korean border.

China intervenes (October–December 1950)

On 3 October 1950, China attempted to warn the US, through its embassy in India, it would intervene if UN forces crossed the Yalu River.[ The US did not respond as policymakers in Washington, including Truman, considered it a bluff.][

On 15 October Truman and MacArthur met at Wake Island. This was much publicized because of MacArthur's discourteous refusal to meet the president in the contiguous US. To Truman, MacArthur speculated there was little risk of Chinese intervention in Korea, and the PRC's opportunity for aiding the KPA had lapsed. He believed the PRC had 300,000 soldiers in Manchuria and 100,000–125,000 at the Yalu River. He concluded that, although half of those forces might cross south, "if the Chinese tried to get down to Pyongyang, there would be the greatest slaughter" without Soviet air force protection.]Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

decided China would intervene even without Soviet air support, basing its decision on a belief superior morale could defeat an enemy that had superior equipment.People's Volunteer Army

The People's Volunteer Army (PVA), officially the Chinese People's Volunteers (CPV), was the armed expeditionary forces China in the Korean War, deployed by the History of the People's Republic of China (1949–1976), People's Republic of Chi ...

(PVA) troops crossed the Yalu into North Korea. UN aerial reconnaissance had difficulty sighting PVA units in the daytime, because their march and bivouac discipline minimized detection. The PVA marched "dark-to-dark" (19:00–03:00), and aerial camouflage (concealing soldiers, pack animals, and equipment) was deployed by 05:30. Meanwhile, daylight advance parties scouted for the next bivouac site. During daylight activity or marching, soldiers remained motionless if an aircraft appeared; PVA officers were under orders to shoot security violators. Such battlefield discipline allowed a three- division army to march the from An-tung, Manchuria, to the combat zone in 19 days. Another division night-marched a circuitous mountain route, averaging daily for 18 days.

After secretly crossing the Yalu River on 19 October, the PVA 13th Army Group launched the First Phase Offensive on 25 October, attacking advancing UN forces near the Sino-Korean border. This decision made solely by China changed the attitude of the Soviet Union. Twelve days after PVA troops entered the war, Stalin allowed the Soviet Air Forces

The Soviet Air Forces (, VVS SSSR; literally "Military Air Forces of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics"; initialism VVS, sometimes referred to as the "Red Air Force") were one of the air forces of the Soviet Union. The other was the Sovie ...

to provide air cover and supported more aid to China. After inflicting heavy losses on the ROK II Corps 2nd Corps, Second Corps, or II Corps may refer to:

France

* 2nd Army Corps (France)

* II Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* II Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French ...

at the Battle of Onjong

The Battle of Onjong (), also known as the Battle of Wenjing (), was one of the first engagements between Chinese and South Korean forces during the Korean War. It took place around Onjong in present-day North Korea from 25 to 29 October 1950. ...

, the first confrontation between Chinese and US military occurred on 1 November 1950. Deep in North Korea, thousands of soldiers from the PVA 39th Army encircled and attacked the US 8th Cavalry Regiment

The 8th Cavalry Regiment is a regiment of the United States Army formed in 1866 during the American Indian Wars. The 8th Cavalry continued to serve under a number of designations, fighting in every other major U.S. conflict since, except Wor ...

with three-prong assaults—from the north, northwest, and west—and overran the defensive position flanks in the Battle of Unsan

The Battle of Unsan (), also known as the Battle of Yunshan (), was a series of engagements of the Korean War that took place from 25 October to 4 November 1950 near Unsan, North Pyongan province in present-day North Korea

North Kore ...

.Peng Dehuai

Peng Dehuai (October 24, 1898November 29, 1974; also spelled as Peng Teh-Huai) was a Chinese general and politician who was the Minister of National Defense (China), Minister of National Defense from 1954 to 1959. Peng was born into a poor ...

as field commander. On 25 November, on the Korean western front, the PVA 13th Army Group attacked and overran the ROK II Corps at the Battle of the Ch'ongch'on River

The Battle of the Ch'ongch'on River (), also known as the Battle of the Ch'ongch'on, was a decisive battle in the Korean War that took place from November 25 to December 2, 1950, along the Ch'ongch'on River Valley in the northwestern part of Nor ...

, and then inflicted heavy losses on the US 2nd Infantry Division on the UN forces' right flank. Believing they could not hold against the PVA, the Eighth Army began to retreat, crossing the 38th parallel in mid-December.

In the east, on 27 November, the PVA 9th Army Group initiated the Battle of Chosin Reservoir