Fettmilch Uprising on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Fettmilch uprising () of 1614 was an

The Fettmilch uprising () of 1614 was an

Since the Council was not able to produce any evidence on the location of the 9.5 tonnes of missing gold, the radical wing of the guilds under Vincenz Fettmilch gained ground. On 5 May 1614, he had the city gates occupied by his supporters, declared the old council dissolved, and imprisoned its members in the Römer. The Senior Mayor , one of the 18 new councillors created by the citizens' contract, negotiated with the protestors and on 19 May, he signed an agreement with Fettmilch providing for the resignation of the council. However, two months later, on 26 July, an imperial herald appeared in the city, demanding the restoration of the council. When this had not happened by 22 August, the emperor threatened to place every Frankfurter under the

Since the Council was not able to produce any evidence on the location of the 9.5 tonnes of missing gold, the radical wing of the guilds under Vincenz Fettmilch gained ground. On 5 May 1614, he had the city gates occupied by his supporters, declared the old council dissolved, and imprisoned its members in the Römer. The Senior Mayor , one of the 18 new councillors created by the citizens' contract, negotiated with the protestors and on 19 May, he signed an agreement with Fettmilch providing for the resignation of the council. However, two months later, on 26 July, an imperial herald appeared in the city, demanding the restoration of the council. When this had not happened by 22 August, the emperor threatened to place every Frankfurter under the

The protestors, who had assumed all along that the emperor would support them, reacted with fury, directed at the weakest of their supposed enemies. On 22 August, a crowd of

The protestors, who had assumed all along that the emperor would support them, reacted with fury, directed at the weakest of their supposed enemies. On 22 August, a crowd of

These anti-semitic acts and the intertwined conflict with the emperor caused Fettmilch's prestige to rapidly drop. Ever more of his followers abandoned him. On 28 October 1614, an imperial herald announced in the Römer that the

These anti-semitic acts and the intertwined conflict with the emperor caused Fettmilch's prestige to rapidly drop. Ever more of his followers abandoned him. On 28 October 1614, an imperial herald announced in the Römer that the  Fettmilch's house on the was torn down and a was erected on the spot which listed his crimes in German and Latin.

After the executions, which included an extensive reading of verdicts and lasted several hours, an imperial mandate was proclaimed, which ordered the restoration of the Jews expelled in August 1614, with their old rights and privileges. Later the same day, the Jews who had been in Höchst and Hanau since the expulsion, returned to the Judengasse in a festive procession. An

Fettmilch's house on the was torn down and a was erected on the spot which listed his crimes in German and Latin.

After the executions, which included an extensive reading of verdicts and lasted several hours, an imperial mandate was proclaimed, which ordered the restoration of the Jews expelled in August 1614, with their old rights and privileges. Later the same day, the Jews who had been in Höchst and Hanau since the expulsion, returned to the Judengasse in a festive procession. An

With Imperial support, the old council controlled by the Alten Limpurg society largely pushed through its goals. The number of councillors from the society was limited to fourteen, but all complaints of the citizenry against the old council were denied. The balance of power in the council shifted slightly in favour of merchants from the Zum Frauenstein society.

While the commercial element in the civic government was therefore slightly strengthened, the influence of craftsmen was curtailed even further. The guilds were required to pay a fine of 100,000 guilders to the emperor and were dissolved. Supervision of trades henceforth rested with the council itself. Nine Frankfurt citizens who participated in the riots were permanently exiled from the city, another 23 were exiled for a limited period of time. More than 2,000 citizens had to pay fines.

It was more than a century before the Frankfurt citizens peacefully regained the privileges which they had lost as a result of the Fettmilch uprising. With the support of the emperor, the nine-man audit committee was reintroduced in 1726, which ended the worst abuses of the patrician government through control of the finances.

The Jews were meant to be compensated for all property damage from the city treasury, but they never actually received the money. Although they were the victims of the uprising, the old restrictions on their rights were largely retained. The new ''Judenstättigkeit'' for Frankfurt, which was issued by the Imperial commissioners from Hesse and Mainz, specified that the number of Jewish families in Frankfurt should be limited to five hundred. Only twelve Jewish couples were allowed to marry each year, while Christians only had to prove to the civic administration that they had sufficient assets in order to get a marriage license. The Jews' economic rights were broadly equivalent to those of Christian non-citizen residents, since they could not operate shops, engage in small-scale commerce, establish commercial partnerships with citizens, or own land. These limitations all had roots deep in the Middle Ages. A new feature of the new ''Judenstättigkeit'' was that Jews were now explicitly permitted to engage in

With Imperial support, the old council controlled by the Alten Limpurg society largely pushed through its goals. The number of councillors from the society was limited to fourteen, but all complaints of the citizenry against the old council were denied. The balance of power in the council shifted slightly in favour of merchants from the Zum Frauenstein society.

While the commercial element in the civic government was therefore slightly strengthened, the influence of craftsmen was curtailed even further. The guilds were required to pay a fine of 100,000 guilders to the emperor and were dissolved. Supervision of trades henceforth rested with the council itself. Nine Frankfurt citizens who participated in the riots were permanently exiled from the city, another 23 were exiled for a limited period of time. More than 2,000 citizens had to pay fines.

It was more than a century before the Frankfurt citizens peacefully regained the privileges which they had lost as a result of the Fettmilch uprising. With the support of the emperor, the nine-man audit committee was reintroduced in 1726, which ended the worst abuses of the patrician government through control of the finances.

The Jews were meant to be compensated for all property damage from the city treasury, but they never actually received the money. Although they were the victims of the uprising, the old restrictions on their rights were largely retained. The new ''Judenstättigkeit'' for Frankfurt, which was issued by the Imperial commissioners from Hesse and Mainz, specified that the number of Jewish families in Frankfurt should be limited to five hundred. Only twelve Jewish couples were allowed to marry each year, while Christians only had to prove to the civic administration that they had sufficient assets in order to get a marriage license. The Jews' economic rights were broadly equivalent to those of Christian non-citizen residents, since they could not operate shops, engage in small-scale commerce, establish commercial partnerships with citizens, or own land. These limitations all had roots deep in the Middle Ages. A new feature of the new ''Judenstättigkeit'' was that Jews were now explicitly permitted to engage in

Bibliography

on the Fettmilch pogrom in the '' Hessian Bibliography'' *

German and Yiddish text of the Vinz-Hans-Lieds (Megillat Vintz).

The Vinz-Hans-Lied, sung by Diana Matut, accompanied by Simkhat Hanefesh

{{Authority control Rebellions in Germany Military history of Frankfurt Jews and Judaism in Frankfurt Anti-Jewish pogroms in Europe 1614 in religion 1614 in the Holy Roman Empire 17th-century rebellions Antisemitism in Germany

The Fettmilch uprising () of 1614 was an

The Fettmilch uprising () of 1614 was an antisemitic

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

revolt in the Free imperial city of Frankfurt am Main

Frankfurt am Main () is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 773,068 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the List of cities in Germany by population, fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located in the forela ...

, led by baker Vincenz Fettmilch. It was initially a revolt by the guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular territory. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradespeople belonging to a professional association. They so ...

s against the mismanagement of the patrician-dominated city council, that culminated in the pillaging of the Frankfurter Judengasse

The Frankfurter Judengasse () was the Jewish ghetto of Frankfurt and one of the earliest ghettos in Germany. It existed from 1462 until 1811 and was home to Germany's largest Jewish community in early modern times.

At the end of the 19th centu ...

(Jewish quarter) and the expulsion of Frankfurt's entire Jewish population, the worst outbreak of antisemitism in Germany between the fourteenth century and the 1930s. The uprising lasted from May until it was finally defeated in November through the intervention of the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

, the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel (), spelled Hesse-Cassel during its entire existence, also known as the Hessian Palatinate (), was a state of the Holy Roman Empire. The state was created in 1567 when the Landgraviate of Hesse was divided upon t ...

, and the Archbishop of Mainz

The Elector of Mainz was one of the seven Prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire. As both the Archbishop of Mainz and the ruling prince of the Electorate of Mainz, the Elector of Mainz held a powerful position during the Middle Ages. The Archb ...

.

Background

The uprising had its origins in the consolidation of the patrician regime in Frankfurt at the end of the 16th century, along with the discontent of the citizens about the council's mismanagement of the city and the limited influence of the guilds on civic politics. These political complaints of the guilds were intertwined with antisemitic sentiment from the beginning.Outbreak of disorder

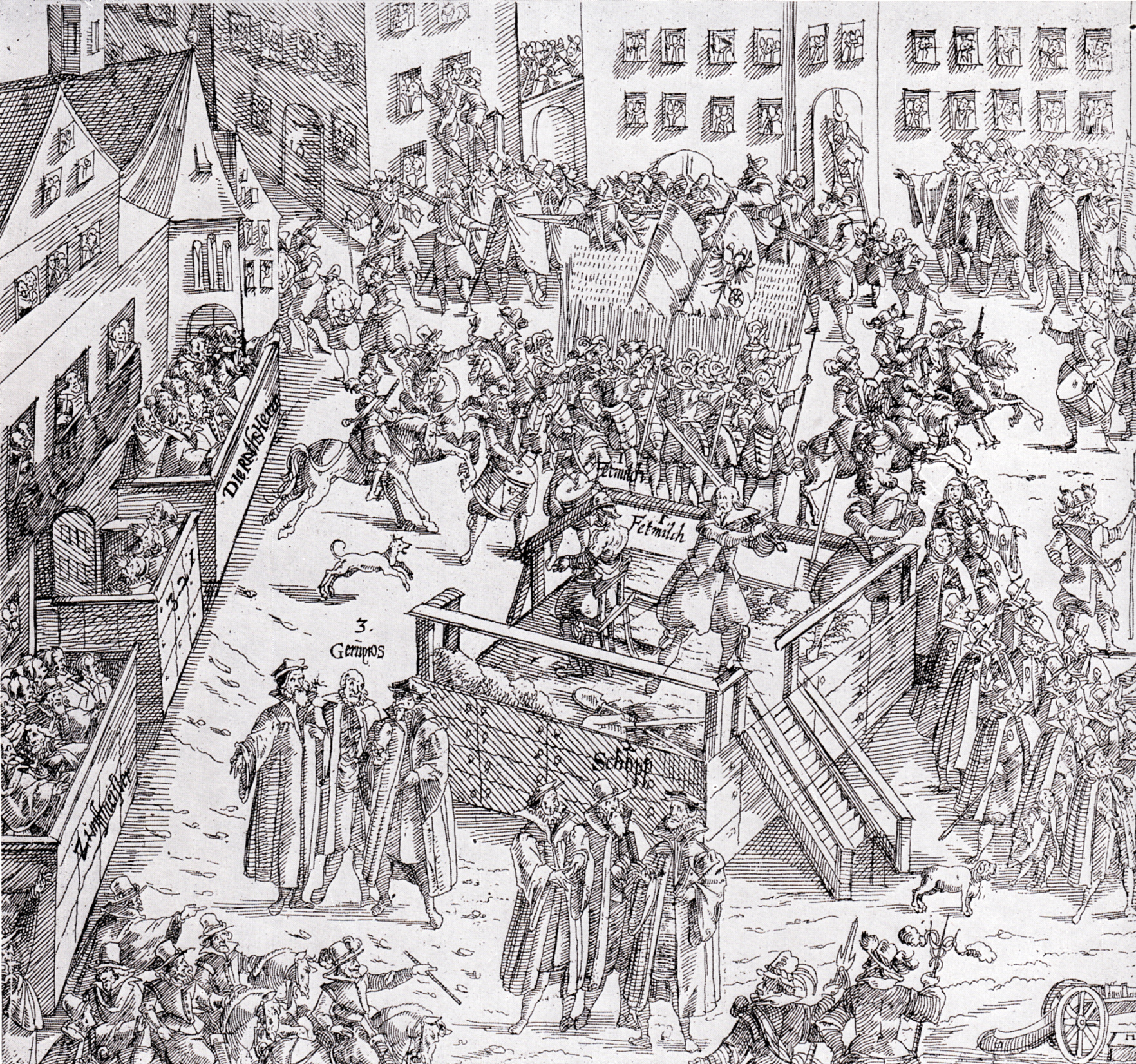

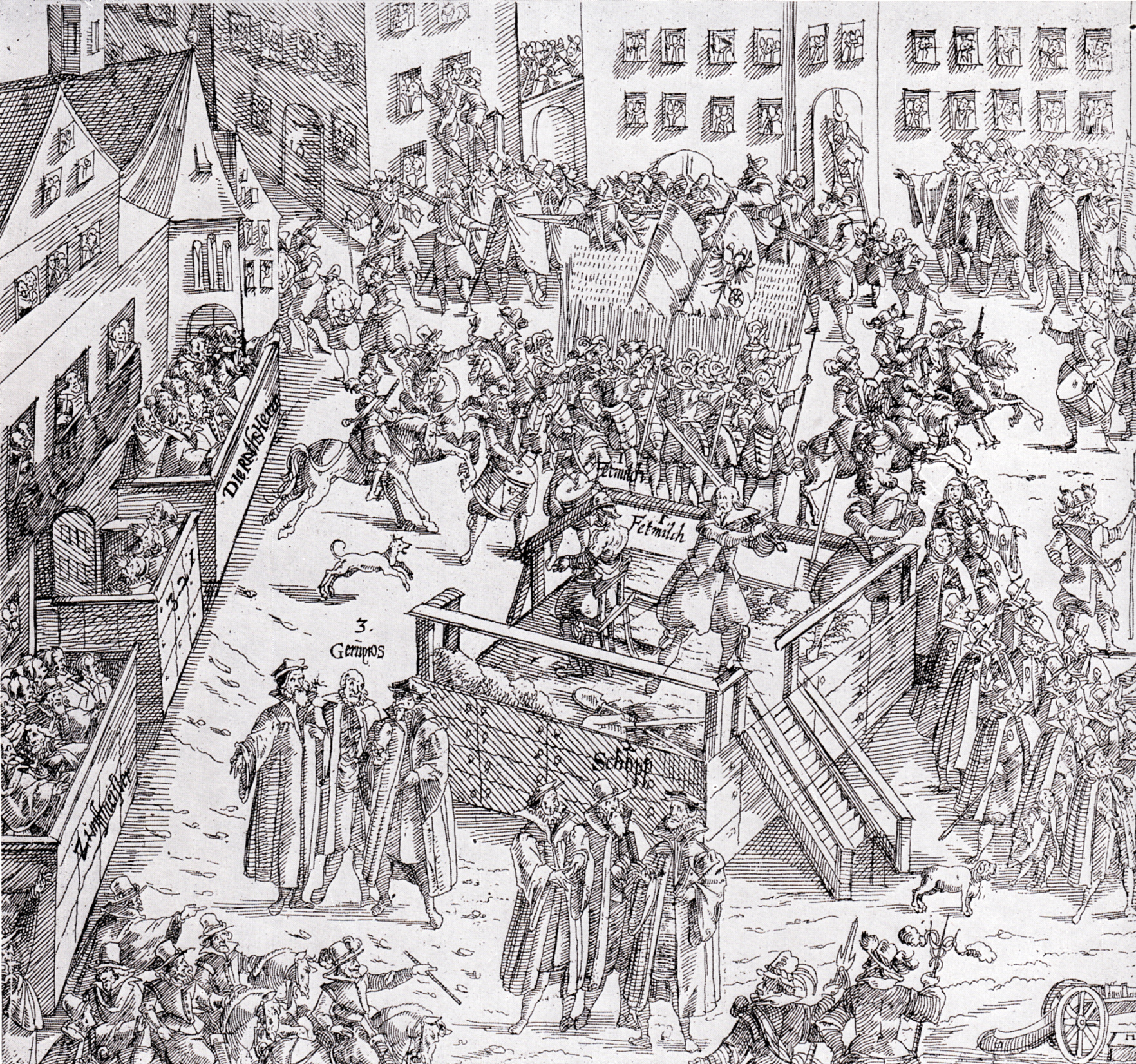

left, Coronation parade in front of the Frankfurt Römer for Emperor Matthias, on 13 June 1612. The unrest began on 9 June 1612, when the citizens and guildmasters demanded that the privileges of the city be read out publicly by the city council () before theelection

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative d ...

of the new emperor, Matthias Matthias is a name derived from the Greek Ματθαίος, in origin similar to Matthew.

Notable people

Notable people named Matthias include the following:

Religion

* Saint Matthias, chosen as an apostle in Acts 1:21–26 to replace Judas Isca ...

, as had been customary in earlier times. This had last occurred 36 years earlier, before the election of Matthias' predecessor Rudolf II

Rudolf II (18 July 1552 – 20 January 1612) was Holy Roman Emperor (1576–1612), King of Hungary and Croatia (as Rudolf I, 1572–1608), King of Bohemia (1575–1608/1611) and Archduke of Austria (1576–1608). He was a member of the H ...

. The city council denied the citizens' demand, leading to rumours that the council was planning to withhold information from them about the tax exemptions that would be awarded by the new Emperor.

Moreover, the citizens wanted a greater say in civic government. The 42-member city council was dominated by the 24 members from the "patrician" families belonging to the society. This was the part of the Frankfurt patriciate who had a noble

A noble is a member of the nobility.

Noble may also refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Noble Glacier, King George Island

* Noble Nunatak, Marie Byrd Land

* Noble Peak, Wiencke Island

* Noble Rocks, Graham Land

Australia

* Noble Island, Gr ...

lifestyle and lived off ground rent

As a legal term, ground rent specifically refers to regular payments made by a holder of a leasehold property to the freeholder or a superior leaseholder, as required under a lease. In this sense, a ground rent is created when a freehold piece of ...

s rather than from commerce

Commerce is the organized Complex system, system of activities, functions, procedures and institutions that directly or indirectly contribute to the smooth, unhindered large-scale exchange (distribution through Financial transaction, transactiona ...

or trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

Traders generally negotiate through a medium of cr ...

. Alten Limpurg was opposed by another patrician society , which contained the city's wholesalers

Wholesaling or distributing is the sale of goods or merchandise to retailers; to industrial, commercial, institutional or other professional business users; or to other wholesalers (wholesale businesses) and related subordinated services. In g ...

, and shared the remaining 18 seats with representatives of the artisans' guilds. This arrangement of seats was fixed. Furthermore, there were no general elections; voting only took place when a particular councillor resigned or died, in order to select his successor.

The guildmasters were also pushing for the establishment of a public cornmarket in Frankfurt, in order to bring about lower grain prices, and a decrease in the interest rate

An interest rate is the amount of interest due per period, as a proportion of the amount lent, deposited, or borrowed (called the principal sum). The total interest on an amount lent or borrowed depends on the principal sum, the interest rate, ...

charged by Frankfurt's Jews from 12% to 6%. The Calvinists

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyterian, ...

were demanding an equal civic position to that of the Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

s and would later support the uprising in greater numbers than them. In addition to these concrete but very diverse demands, there was a general discontent that had been brewing for decades about the perceived self-servingness of the council, which had begun referring to the citizens as "subjects" in its public pronouncements.

The antisemitic aspect of the uprising owed something to the merchants, craftsmen, and others who were in debt to moneylenders in the Frankfurt Jewish quarter, the Judengasse. They hoped to get rid of their debts by getting rid of their creditors.

The citizens' contract

In the conflict about reading of the privileges, the shopkeeper and gingerbread-baker Vinzenz Fettmilch, who had been a citizen of the city since 1593, was the guildmasters' spokesman. After being rebuffed by the council, they turned first to theprince-elector

The prince-electors ( pl. , , ) were the members of the Electoral College of the Holy Roman Empire, which elected the Holy Roman Emperor. Usually, half of the electors were archbishops.

From the 13th century onwards, a small group of prince- ...

s and their representatives, who were present in Frankfurt to hold the election of the emperor, and finally to the new emperor himself, when he arrived in Frankfurt for the coronation. Initially, the electors and the emperor refused to get involved in the internal affairs of Frankfurt. But when the guilds formed a committee to negotiate with the council, Matthias established a commission to arbitrate the dispute.

This commission, which was led by the neighbouring lords, the Archbishop-elector of Mainz and the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel (), spelled Hesse-Cassel during its entire existence, also known as the Hessian Palatinate (), was a state of the Holy Roman Empire. The state was created in 1567 when the Landgraviate of Hesse was divided upon t ...

, was seen by the Frankfurt patricians as a threat to their status. Moreover, they feared that the disorder would have a negative impact on the Messe (the city's market). Nürnberg

Nuremberg (, ; ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the largest city in Franconia, the second-largest city in the German state of Bavaria, and its 544,414 (2023) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest city in Germany. ...

and other trade cities had already submitted formal queries to the Frankfurt government, about whether it could guarantee the safety of foreign merchants. Therefore, on 21 December 1612, the council voluntarily concluded an agreement, the "citizens' contract" (). This new civic constitution, which remained in force until 1806, expanded the council's membership by 18 seats and established a nine-man committee representing the guilds, which had the right to audit the city's financial accounts. In 1614, the newly expanded council elected Nicolaus Weitz as the new '' Stadtschultheiß'' (akin to a mayor).

Renewed crisis

When the new audit process took place in 1613, it turned out that Frankfurt was deeply in debt and that the council had expended, among other things, the fund that it should have used for supporting the poor and the sick. The tax-collectors had embezzled money from fines for their own use. In addition, it became known that the patrician had tried to get the emperor to block the passage of the citizens' contract. A further conflict concerned the "''Judenstättigkeit''", the ordinance which regulated the lives of Frankfurt's Jews. Theprotection money

A protection racket is a type of racket and a scheme of organized crime perpetrated by a potentially hazardous organized crime group that generally guarantees protection outside the sanction of the law to another entity or individual from viol ...

which the Jews were required to pay under this ordinance had not gone into the civic treasury. Instead, the council members had shared it among themselves. To prevent this illegal act from becoming public, the council had all printed copies of the ''Judenstättigkeit'' confiscated. At the same time, rumours spread that the Jews had made common cause with the patricians. Vincenz Fettmilch finally published the edict which Emperor Charles IV

Charles IV (; ; ; 14 May 1316 – 29 November 1378''Karl IV''. In: (1960): ''Geschichte in Gestalten'' (''History in figures''), vol. 2: ''F–K''. 38, Frankfurt 1963, p. 294), also known as Charles of Luxembourg, born Wenceslaus (, ), was H ...

had granted to the Jews of Frankfurt in 1349. This contained the fateful sentence, stating that the emperor would not hold the city responsible if the Jews "departed into death, perished, or were slain." Many took this as permission to undertake a pogrom

A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of Massacre, massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe late 19th- and early 20th-century Anti-Jewis ...

.

The uprising

On 6 May 1613, after the enormous size of Frankfurt's debt – 9.5 tonnes of goldguilder

Guilder is the English translation of the Dutch and German ''gulden'', originally shortened from Middle High German ''guldin pfenninc'' (" gold penny"). This was the term that became current in the southern and western parts of the Holy Rom ...

s – had been made public, a crowd stormed the Römer (the Frankfurt city council building) and forced them to hand the keys to the city treasury over to the nine-man committee of the guilds. In the following months, the council was only able to spend money that the committee granted to it. On the grounds that both sides had breached the recently agreed citizen's contract, the emperor intervened, pushing for a compromise. On 15 January 1614, both parties signed a new contract.

Deposition of the Council and threat of the Imperial ban

Since the Council was not able to produce any evidence on the location of the 9.5 tonnes of missing gold, the radical wing of the guilds under Vincenz Fettmilch gained ground. On 5 May 1614, he had the city gates occupied by his supporters, declared the old council dissolved, and imprisoned its members in the Römer. The Senior Mayor , one of the 18 new councillors created by the citizens' contract, negotiated with the protestors and on 19 May, he signed an agreement with Fettmilch providing for the resignation of the council. However, two months later, on 26 July, an imperial herald appeared in the city, demanding the restoration of the council. When this had not happened by 22 August, the emperor threatened to place every Frankfurter under the

Since the Council was not able to produce any evidence on the location of the 9.5 tonnes of missing gold, the radical wing of the guilds under Vincenz Fettmilch gained ground. On 5 May 1614, he had the city gates occupied by his supporters, declared the old council dissolved, and imprisoned its members in the Römer. The Senior Mayor , one of the 18 new councillors created by the citizens' contract, negotiated with the protestors and on 19 May, he signed an agreement with Fettmilch providing for the resignation of the council. However, two months later, on 26 July, an imperial herald appeared in the city, demanding the restoration of the council. When this had not happened by 22 August, the emperor threatened to place every Frankfurter under the Imperial ban

The imperial ban () was a form of outlawry in the Holy Roman Empire. At different times, it could be declared by the Holy Roman Emperor, by the Imperial Diet, or by courts like the League of the Holy Court (''Vehmgericht'') or the '' Reichskammerg ...

, who was not prepared to swear under oath to submit to his command.

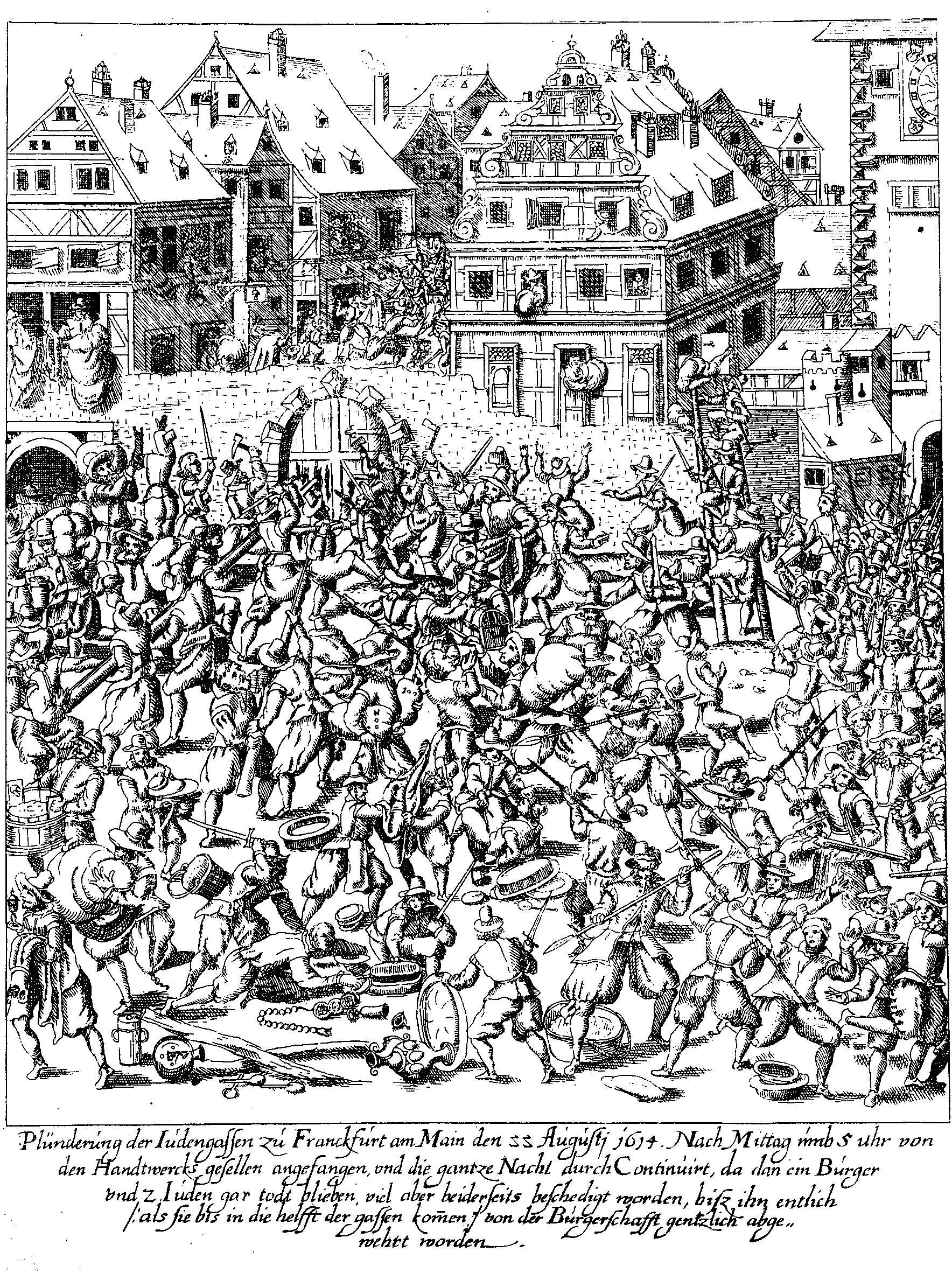

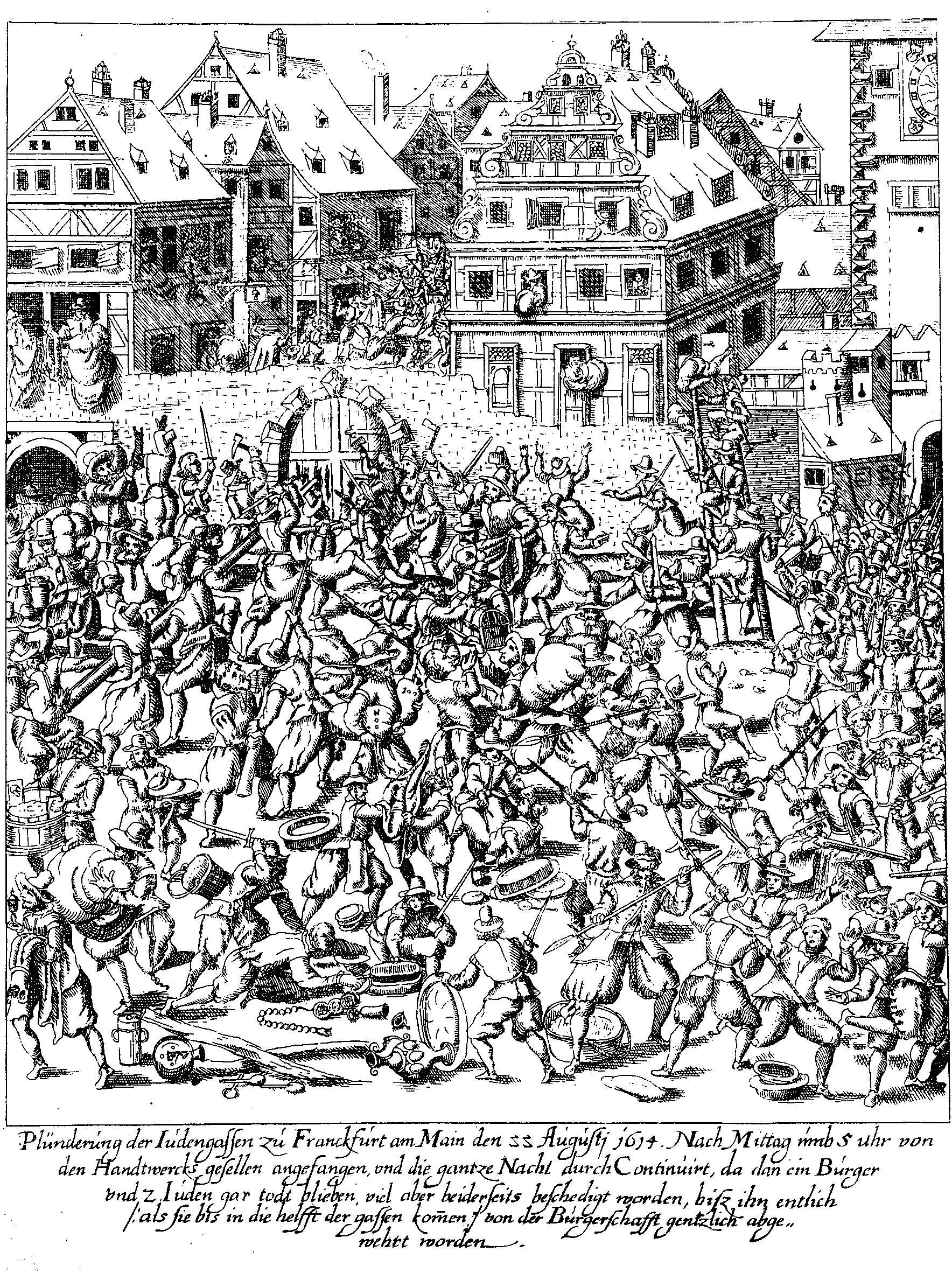

Pillaging the Judengasse

The protestors, who had assumed all along that the emperor would support them, reacted with fury, directed at the weakest of their supposed enemies. On 22 August, a crowd of

The protestors, who had assumed all along that the emperor would support them, reacted with fury, directed at the weakest of their supposed enemies. On 22 August, a crowd of journeymen

A journeyman is a worker, skilled in a given building trade or craft, who has successfully completed an official apprenticeship qualification. Journeymen are considered competent and authorized to work in that field as a fully qualified employee ...

surged through the city shouting "give us work and bread!" Around noon, the now-drunk journeymen stormed the Frankfurt Judengasse, the walled ghetto

A ghetto is a part of a city in which members of a minority group are concentrated, especially as a result of political, social, legal, religious, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished than other ...

on the east side of the town, which was accessed through three gates.

In the fighting that followed, one of the journeymen and two Jewish defenders lost their lives. The Jews eventually fled to the or into the Christian part of the city, where many of them were hidden by friendly Frankfurt citizens. Meanwhile, the mob plundered the Judengasse, until it was finally driven out by the Frankfurt citizens' militia around midnight. The damage from this pillaging ran to around 170,000 guilders.

Vincenz Fettmilch himself does not seem to have participated in the riot. Later, at his trial, he claimed that it had happened against his will. It is possible that he had briefly lost control of his followers. However, no convincing evidence exists to support Fettmilch's attempts to disentangle himself from these riots. On the contrary, the next day, he ordered the expulsion of all Jews from Frankfurt. Most of them sought refuge in the neighbouring cities of Höchst and Hanau

Hanau () is a city in the Main-Kinzig-Kreis, in Hesse, Germany. It is 25 km east of Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main and part of the Frankfurt Rhine-Main, Frankfurt Rhine-Main Metropolitan Region. Its railway Hanau Hauptbahnhof, station is a ma ...

(in Mainz and Hesse respectively).

The end of Fettmilch

These anti-semitic acts and the intertwined conflict with the emperor caused Fettmilch's prestige to rapidly drop. Ever more of his followers abandoned him. On 28 October 1614, an imperial herald announced in the Römer that the

These anti-semitic acts and the intertwined conflict with the emperor caused Fettmilch's prestige to rapidly drop. Ever more of his followers abandoned him. On 28 October 1614, an imperial herald announced in the Römer that the Imperial ban

The imperial ban () was a form of outlawry in the Holy Roman Empire. At different times, it could be declared by the Holy Roman Emperor, by the Imperial Diet, or by courts like the League of the Holy Court (''Vehmgericht'') or the '' Reichskammerg ...

had been imposed on Fettmilch, and the tailors Konrad Gerngross and Konrad Schopp, as the ringleaders of the rebellion. On 27 November the judge ordered Fettmilch's arrest. Subsequently, four more Frankfurters were placed under the ban, including the silk-dyer Georg Ebel of Sachsenhausen.

In a long trial, which extended through almost the whole of 1615, Fettmilch and thirty-eight of his associated were not prosecuted for the riots against the Jews directly, but for lèse-majesté

''Lèse-majesté'' or ''lese-majesty'' ( , ) is an offence or defamation against the dignity of a ruling head of state (traditionally a monarch but now more often a president) or of the state itself. The English name for this crime is a mod ...

, since they had disregarded the commands of the emperor. At least seven of them were sentenced to death, which was carried out on 28 February 1616 in the .Lothar Gall

Lothar Gall (3 December 1936 – 20 June 2024) was a German historian known as "one of German liberalism's primary historians". He was a professor of history at Goethe University Frankfurt from 1975 until his retirement in 2005. His biography o ...

(Ed.): ''FFM 1200. Traditionen und Perspektiven einer Stadt''. Thorbecke. Sigmaringen 1994, ISBN 3-7995-1203-9, p. 127. Before the beheading, their oath fingers were cut off. Fettmilch was also quartered after his execution. The heads of Fettmilch, Gerngross, Schopp, and Ebel were displayed on pikes on the towers of the Alte Brücke, where they remained until at least the time of Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

, who mentions them in his autobiography ''Dichtung und Wahrheit

''Aus meinem Leben: Dichtung und Wahrheit'' (''From my Life: Poetry and Truth''; 1811–1833) is an autobiography by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe that comprises the time from the poet's childhood to the days in 1775, when he was about to leave for ...

''. Fettmilch's house on the was torn down and a was erected on the spot which listed his crimes in German and Latin.

After the executions, which included an extensive reading of verdicts and lasted several hours, an imperial mandate was proclaimed, which ordered the restoration of the Jews expelled in August 1614, with their old rights and privileges. Later the same day, the Jews who had been in Höchst and Hanau since the expulsion, returned to the Judengasse in a festive procession. An

Fettmilch's house on the was torn down and a was erected on the spot which listed his crimes in German and Latin.

After the executions, which included an extensive reading of verdicts and lasted several hours, an imperial mandate was proclaimed, which ordered the restoration of the Jews expelled in August 1614, with their old rights and privileges. Later the same day, the Jews who had been in Höchst and Hanau since the expulsion, returned to the Judengasse in a festive procession. An Imperial eagle

The eagle is used in heraldry as a charge, as a supporter, and as a crest. Heraldic eagles can be found throughout world history like in the Achaemenid Empire or in the present Republic of Indonesia. The European post-classical symbolism of ...

was placed on the gate to the Judengasse with the inscription "Roman Imperial Majesty and the Holy Empire's Protection."

Aftermath

With Imperial support, the old council controlled by the Alten Limpurg society largely pushed through its goals. The number of councillors from the society was limited to fourteen, but all complaints of the citizenry against the old council were denied. The balance of power in the council shifted slightly in favour of merchants from the Zum Frauenstein society.

While the commercial element in the civic government was therefore slightly strengthened, the influence of craftsmen was curtailed even further. The guilds were required to pay a fine of 100,000 guilders to the emperor and were dissolved. Supervision of trades henceforth rested with the council itself. Nine Frankfurt citizens who participated in the riots were permanently exiled from the city, another 23 were exiled for a limited period of time. More than 2,000 citizens had to pay fines.

It was more than a century before the Frankfurt citizens peacefully regained the privileges which they had lost as a result of the Fettmilch uprising. With the support of the emperor, the nine-man audit committee was reintroduced in 1726, which ended the worst abuses of the patrician government through control of the finances.

The Jews were meant to be compensated for all property damage from the city treasury, but they never actually received the money. Although they were the victims of the uprising, the old restrictions on their rights were largely retained. The new ''Judenstättigkeit'' for Frankfurt, which was issued by the Imperial commissioners from Hesse and Mainz, specified that the number of Jewish families in Frankfurt should be limited to five hundred. Only twelve Jewish couples were allowed to marry each year, while Christians only had to prove to the civic administration that they had sufficient assets in order to get a marriage license. The Jews' economic rights were broadly equivalent to those of Christian non-citizen residents, since they could not operate shops, engage in small-scale commerce, establish commercial partnerships with citizens, or own land. These limitations all had roots deep in the Middle Ages. A new feature of the new ''Judenstättigkeit'' was that Jews were now explicitly permitted to engage in

With Imperial support, the old council controlled by the Alten Limpurg society largely pushed through its goals. The number of councillors from the society was limited to fourteen, but all complaints of the citizenry against the old council were denied. The balance of power in the council shifted slightly in favour of merchants from the Zum Frauenstein society.

While the commercial element in the civic government was therefore slightly strengthened, the influence of craftsmen was curtailed even further. The guilds were required to pay a fine of 100,000 guilders to the emperor and were dissolved. Supervision of trades henceforth rested with the council itself. Nine Frankfurt citizens who participated in the riots were permanently exiled from the city, another 23 were exiled for a limited period of time. More than 2,000 citizens had to pay fines.

It was more than a century before the Frankfurt citizens peacefully regained the privileges which they had lost as a result of the Fettmilch uprising. With the support of the emperor, the nine-man audit committee was reintroduced in 1726, which ended the worst abuses of the patrician government through control of the finances.

The Jews were meant to be compensated for all property damage from the city treasury, but they never actually received the money. Although they were the victims of the uprising, the old restrictions on their rights were largely retained. The new ''Judenstättigkeit'' for Frankfurt, which was issued by the Imperial commissioners from Hesse and Mainz, specified that the number of Jewish families in Frankfurt should be limited to five hundred. Only twelve Jewish couples were allowed to marry each year, while Christians only had to prove to the civic administration that they had sufficient assets in order to get a marriage license. The Jews' economic rights were broadly equivalent to those of Christian non-citizen residents, since they could not operate shops, engage in small-scale commerce, establish commercial partnerships with citizens, or own land. These limitations all had roots deep in the Middle Ages. A new feature of the new ''Judenstättigkeit'' was that Jews were now explicitly permitted to engage in wholesaling

Wholesaling or distributing is the sale of goods or merchandise to retailers; to industrial, commercial, institutional or other professional business users; or to other wholesalers (wholesale businesses) and related subordinated services. In ...

, although they were sometimes required to have sureties as with grain, wine, spices, and long-distance trade in cloth, silk, and other textiles. It is possible that the emperor expanded the economic power of the Jews in this way so that they could act as a counter-weight to the Christian merchant families, which the abolition of the guilds had left in charge of Frankfurt. The Judengasse ghetto endured until Napoleonic times.

The anniversary of the triumphant Jewish return to Frankfurt is commemorated annually by the Jewish community in the festival of Purim Vinz on 20 Adar

Adar (Hebrew: , ; from Akkadian ''adaru'') is the sixth month of the civil year and the twelfth month of the religious year on the Hebrew calendar, roughly corresponding to the month of March in the Gregorian calendar. It is a month of 29 days. ...

in the Jewish calendar

The Hebrew calendar (), also called the Jewish calendar, is a lunisolar calendar used today for Jewish religious observance and as an official calendar of Israel. It determines the dates of Jewish holidays and other rituals, such as ''yahrzeits ...

. The name of the festival is derived from Fettmilch's first name, Vinzenz. A celebratory song, ''Megillat Vintz'' or ''Vinz-Hans-Lief'' was published by Elchanan Bar Abraham in 1648 and continued to be sung at the Purim Vinz festival into the 20th century. It has four verses, whose lyrics exist in Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

, Yiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

, and German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

versions. The melody is that of the German marching song, ''Die Schlacht von Pavia''. The song is an important source for the events of the uprising.

References

Bibliography

;Contemporary sources: * Joseph Hahn (Yuspa): ''Josif Ometz.'' Frankfurt am Main (Hahn wrote a chronicle of the Frankfurt Jewish community up to the time of the pogrom. * Nahmann Puch: ''o title

O, or o, is the fifteenth letter and the fourth vowel letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''o'' (pronounced ), ...

' Frankfurt am Main or Hanau 1616. Ed. Bobzin, Hermann Süß: ''Sammlung Wagenseil'', Harald Fischer Verlag, Erlangen 1996, ISBN 3-89131-227-X (a Yiddish song about the pogrom and its consequences for the Jewish community).

* Horst Karasek: ''Der Fedtmilch-Aufstand oder wie die Frankfurter 1612/14 ihrem Rat einheizten'' (= ''Wagenbachs Taschenbücherei'', Band 58), Wagenbach, Berlin 1979, ISBN 3-8031-2058-6.

;Modern scholarship:

*

*

* (Catalogue for an exhibition of the Historisches Museum Frankfurt).

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Adaptations

* '' Revolution in Frankfurt'', TV documentary, BR Deutschland 1979, book: Heinrich Leippe, director:Fritz Umgelter

Fritz Umgelter (18 August 1922 – 9 May 1981) was a German television director, television writer, and film director.

Umgelter worked mainly in television as both a writer and director. He received directing credit for 68 TV films or series, a ...

, with Günter Strack

Günter Strack (4 June 1929 – 18 January 1999) was a German film and television actor.

Career

In English language films, he played Professor Karl Manfred in the Hitchcock thriller '' Torn Curtain'' (1966) and appeared as Kunik in '' The O ...

, Joost Siedhoff, Richard Münch et al.

* Astrid Keim, ''Das verschwundene Gold'', Acabus 2021 (historical novel)

External links

Bibliography

on the Fettmilch pogrom in the '' Hessian Bibliography'' *

German and Yiddish text of the Vinz-Hans-Lieds (Megillat Vintz).

The Vinz-Hans-Lied, sung by Diana Matut, accompanied by Simkhat Hanefesh

{{Authority control Rebellions in Germany Military history of Frankfurt Jews and Judaism in Frankfurt Anti-Jewish pogroms in Europe 1614 in religion 1614 in the Holy Roman Empire 17th-century rebellions Antisemitism in Germany