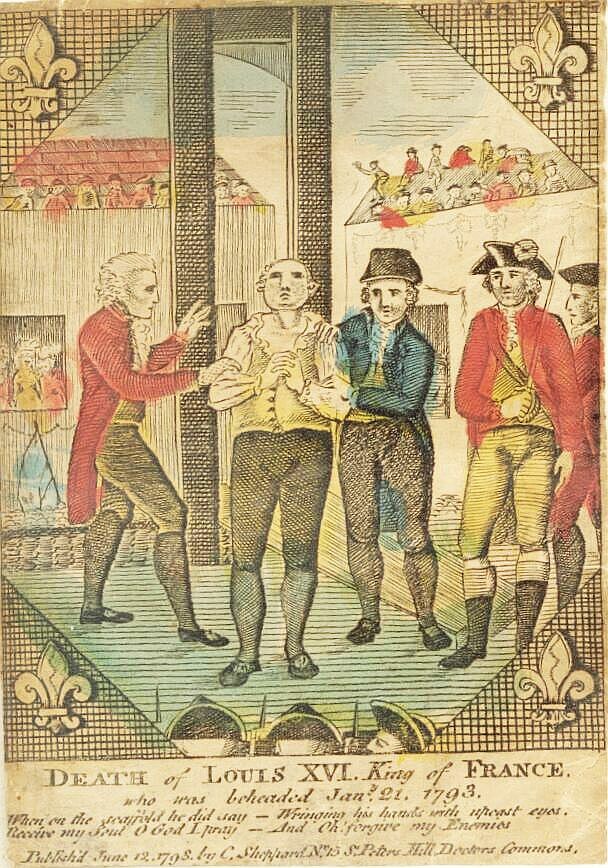

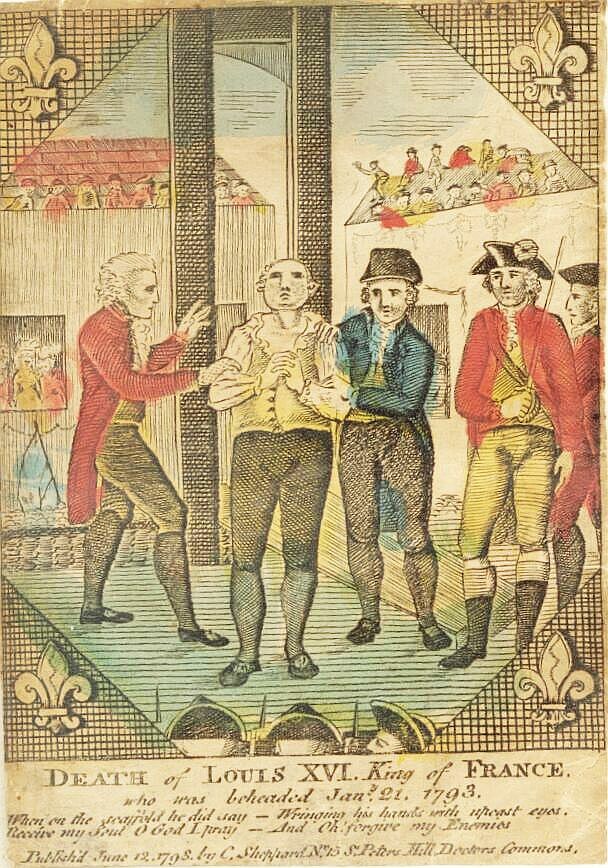

Execution Of King Louis XVI on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Louis exited the carriage and was received by the executioner Charles-Henri Sanson, and then took off his frock coat and

Louis exited the carriage and was received by the executioner Charles-Henri Sanson, and then took off his frock coat and

The body of Louis XVI was immediately transported to the old Church of the Madeleine (demolished in 1799), since the legislation in force forbade burial of his remains beside those of his father, the Dauphin Louis de France, at

The body of Louis XVI was immediately transported to the old Church of the Madeleine (demolished in 1799), since the legislation in force forbade burial of his remains beside those of his father, the Dauphin Louis de France, at

Louis XVI

Louis XVI (Louis-Auguste; ; 23 August 1754 – 21 January 1793) was the last king of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. The son of Louis, Dauphin of France (1729–1765), Louis, Dauphin of France (son and heir- ...

, former Bourbon King of France

France was ruled by monarchs from the establishment of the kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Clovis I, king of the Fra ...

since the abolition of the monarchy

The abolition of monarchy is a legislative or revolutionary movement to abolish monarchy, monarchical elements in government, usually hereditary. The abolition of an absolute monarchy in favour of limited government under a constitutional monar ...

, was publicly executed on 21 January 1793 during the French Revolution at the ''Place de la Révolution

The Place de la Concorde (; ) is a public square in Paris, France. Measuring in area, it is the largest square in the French capital. It is located in the city's eighth arrondissement, at the eastern end of the Champs-Élysées.

It was the s ...

'' in Paris. At his trial four days prior, the National Convention

The National Convention () was the constituent assembly of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for its first three years during the French Revolution, following the two-year National Constituent Assembly and the ...

had convicted the former king of high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its d ...

in a near-unanimous vote; while no one voted "not guilty", several deputies abstained. Ultimately, they condemned him to death by a simple majority Simple majority may refer to:

* Majority, a voting requirement of more than half of all votes cast

* Plurality (voting), a voting requirement of more votes cast for a proposition than for any other option

* First-past-the-post voting, the single-win ...

. The execution by guillotine

A guillotine ( ) is an apparatus designed for effectively carrying out executions by Decapitation, beheading. The device consists of a tall, upright frame with a weighted and angled blade suspended at the top. The condemned person is secur ...

was performed by Charles-Henri Sanson

Charles-Henri Sanson, full title ''Chevalier Charles-Henri Sanson de Longval'' (; 15 February 1739 – 4 July 1806), was the royal executioner of France during the reign of King Louis XVI, as well as high executioner of the First French Republic. ...

, then High Executioner of the French First Republic

In the history of France, the First Republic (), sometimes referred to in historiography as Revolutionary France, and officially the French Republic (), was founded on 21 September 1792 during the French Revolution. The First Republic lasted un ...

and previously royal executioner under Louis.

Often viewed as a turning point in both French and European history, the execution inspired various reactions around the world. To some, Louis' death at the hands of his former subjects symbolized the end of an unbroken thousand-year period of monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, reigns as head of state for the rest of their life, or until abdication. The extent of the authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutio ...

in France and the true beginning of democracy within the nation, although Louis would not be the last king of France with the Bourbon Restoration Bourbon Restoration may refer to:

France under the House of Bourbon:

* Bourbon Restoration in France (1814, after the French revolution and Napoleonic era, until 1830; interrupted by the Hundred Days in 1815)

Spain under the Spanish Bourbons:

* Ab ...

by 1814. Others (even some who had supported major political reform) condemned the execution as an act of senseless bloodshed and saw it as a sign that France had devolved into a state of violent, amoral chaos.

Louis' death emboldened revolutionaries throughout the country, who continued to alter French political and social structure radically over the next several years. Nine months after Louis' death, his wife Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette (; ; Maria Antonia Josefa Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last List of French royal consorts, queen of France before the French Revolution and the establishment of the French First Republic. She was the ...

, formerly queen of France, met her own death at the guillotine at the same location in Paris.

Background

Following the attack on theTuileries Palace

The Tuileries Palace (, ) was a palace in Paris which stood on the right bank of the Seine, directly in the west-front of the Louvre Palace. It was the Parisian residence of most French monarchs, from Henri IV to Napoleon III, until it was b ...

during the insurrection of 10 August 1792

The insurrection of 10 August 1792 was a defining event of the French Revolution, when armed revolutionaries in Paris, increasingly in conflict with the French monarchy, stormed the Tuileries Palace. The conflict led France to abolish the mona ...

, King Louis XVI was imprisoned at the Temple Prison

The Square du Temple is a garden in Paris, France in the 3rd arrondissement, established in 1857. It is one of 24 city squares planned and created by Georges-Eugène Haussmann and Jean-Charles Adolphe Alphand. The Square occupies the site ...

in Paris, along with his wife Marie Antoinette, their two children and his younger sister Élisabeth. The Convention's unanimous decision to abolish the monarchy on 21 September 1792, and the subsequent foundation of the French Republic

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, left the fate of the former king open to debate. A commission was established to examine the evidence against him while the Convention's Legislation Committee considered legal aspects of any future trial. On 13 November, Maximilien Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; ; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman, widely recognised as one of the most influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. Robespierre ferv ...

stated in the Convention that a Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

which Louis himself had violated, and which declared his inviolability, could not now be used in his defence. On 20 November, opinion turned sharply against Louis following the discovery of a secret cache of 726 documents consisting of Louis's communications with bankers and ministers.

With the question of the King's fate now occupying public discourse, Robespierre delivered a speech that would define the rhetoric and course of Louis's trial. Robespierre argued that the dethroned king could now function only as a threat to liberty and national peace and that the members of the Assembly were not to be impartial judges but rather statesmen with responsibility for ensuring public safety:

In arguing for a judgment by the elected Convention without trial, Robespierre supported the recommendations of Jean-Baptiste Mailhe

Jean-Baptiste Mailhe (; 2 June 1750 – 1 June 1834) was a politician during the French Revolution. He gave his name to the Mailhe amendment, which sought to delay the execution of Louis XVI.

Biography

Mailhe was born in 1750 in Guizerix, Gascon ...

, who headed the commission reporting on legal aspects of Louis's trial or judgment. Unlike some Girondins

The Girondins (, ), also called Girondists, were a political group during the French Revolution. From 1791 to 1793, the Girondins were active in the Legislative Assembly and the National Convention. Together with the Montagnards, they initiall ...

( Pétion), Robespierre specifically opposed judgment by primary assemblies or a referendum, believing that this could cause a civil war. While he called for a trial of Queen Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette (; ; Maria Antonia Josefa Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last List of French royal consorts, queen of France before the French Revolution and the establishment of the French First Republic. She was the ...

and the imprisonment of Louis-Charles

Louis XVII (born Louis Charles, Duke of Normandy; 27 March 1785 – 8 June 1795) was the younger son of King Louis XVI of France and Queen Marie Antoinette. His older brother, Louis Joseph, Dauphin of France, died in June 1789, a little over a ...

, the Dauphin of France

Dauphin of France (, also ; ), originally Dauphin of Viennois (''Dauphin de Viennois''), was the title given to the heir apparent to the throne of France from 1350 to 1791, and from 1824 to 1830. The word ''dauphin'' is French for dolphin and ...

, Robespierre advocated that the King be executed despite his opposition to capital punishment:

All the deputies from the Mountain

The Mountain () was a political group during the French Revolution. Its members, called the Montagnards (), sat on the highest benches in the National Convention. The term, first used during a session of the Legislative Assembly, came into ge ...

were asked to attend the meeting on 3 December. Most Montagnards favoured judgment and execution, while the Girondins were more divided concerning how to proceed, with some arguing for royal inviolability, others for clemency, and others advocating lesser punishment or banishment. The next day on 4 December the Convention decreed all the royalist writings illegal. 26 December was the day of the last hearing of the King. On 28 December, Robespierre was asked to repeat his speech on the fate of the king in the Jacobin

The Society of the Friends of the Constitution (), renamed the Society of the Jacobins, Friends of Freedom and Equality () after 1792 and commonly known as the Jacobin Club () or simply the Jacobins (; ), was the most influential political cl ...

club. On 14 January 1793, the King was unanimously voted guilty of conspiracy and attacks upon public safety. Never before the Convention was like a court. On 15 January the call for a referendum was defeated by 424 votes to 287, which Robespierre led. On 16 January, voting began to determine the King's sentence; the session continued for 24 hours. Robespierre worked fervently to ensure the king's execution. The Jacobins successfully defeated the Girondins' final appeal for clemency. On 20 January half of the deputies voted for immediate death.

Night of 20 January

After voting for Louis' execution, the Convention sent a delegation to announce the verdict to the former king at the Temple Prison. Louis made a number of requests, notably asking for an additional period of three days before his execution and a final visit from his family. The deputies accepted the latter but refused to postpone the execution. Louis was served his last dinner at around 7 p.m. After meeting with his confessor, the Irish priestHenry Essex Edgeworth

Henry Essex Edgeworth (174522 May 1807) was an Irish clergyman who was the confessor of Louis XVI.

Life

He was born in Edgeworthstown, County Longford, Ireland, the son of Robert Edgeworth, the Church of Ireland rector of Edgeworthstown. His mo ...

, at around 8 p.m. Louis received the former royal family at his room. He was visited by Marie Antoinette, their children Marie-Thérèse and Louis-Charles, and his sister Élisabeth. At around 11 p.m., Louis' family left the Temple and the former king again met with his confessor. He went to sleep at half past midnight.

Final hours at the Temple Prison

Louis was awakened by his valet Jean-Baptiste Cléry at around 5 a.m., and was greeted by a host of people includingJacques Roux

Jacques Roux (; 21 August 1752 – 10 February 1794) was a radical Roman Catholic Red priest who took an active role in politics during the French Revolution. He skillfully expounded the ideals of popular democracy and classless society to cro ...

, who was appointed to report on the day's events by the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (, ) was a French revolutionary government that seized power in Paris on 18 March 1871 and controlled parts of the city until 28 May 1871. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard (France), Nation ...

. After dressing with Cléry's aid, the former king was joined by Edgeworth at approximately 6 a.m. He heard his last Mass, served by Cléry, and received Viaticum

Viaticum is a term used – especially in the Catholic Church – for the Eucharist (also called Holy Communion), administered, with or without Anointing of the Sick (also called Extreme Unction), to a person who is dying; viaticum is thus a par ...

. The Mass requisites were provided by special direction of the authorities.

On Edgeworth's advice, Louis avoided a last farewell scene with his family. At 7 a.m. he confided his last wishes to the priest: his royal seal

A seal is a device for making an impression in wax, clay, paper, or some other medium, including an embossment on paper, and is also the impression thus made. The original purpose was to authenticate a document, or to prevent interference with ...

was to go to his son and his wedding ring to his wife. At around 8 a.m. the commander of the National Guard, Antoine Joseph Santerre

Antoine Joseph Santerre (; 16 March 1752 in Paris6 February 1809) was a businessman and general during the French Revolution.

Early life

The Santerre family moved from Saint-Michel-en-Thiérache to Paris in 1747 where they purchased a brewery k ...

, arrived at the Temple. Louis received a final blessing from Edgeworth, presented his to a municipal official and handed himself over to Santerre.

Journey to the Place de la Révolution

Louis entered a green carriage awaiting in the second court. The mayor of Paris,Nicolas Chambon

Nicolas Chambon (21 September 1748, Limeil-Brévannes, (Val-de-Marne), France - 2 November 1826, Paris, France) was a French politician who served as Mayor of Paris

The mayor of Paris (, ) is the Chief executive officer, chief executive of ...

, had ensured that the deposed king would not be taken in a tumbrel

A tumbrel (alternatively tumbril) is a two-wheeled cart or wagon typically designed to be hauled by a single horse or ox. Their original use was for agricultural work; in particular they were associated with carrying manure. Their most infamous u ...

. He seated himself in it with the priest, with two militiamen sitting opposite them. The carriage left the Temple at approximately 9 a.m. to the sound of drums and trumpets. For more than an hour the carriage made its way through Paris, escorted by about 200 mounted gendarmes

A gendarmerie () is a paramilitary or military force with law enforcement duties among the civilian population. The term ''gendarme'' () is derived from the medieval French expression ', which translates to "men-at-arms" (). In France and som ...

. The city had 80,000 men-at-arms ( National Guardsmen, '' fédérés'', and riflemen) occupying intersections, squares and posted along the streets, as well as cannons placed at strategic locations. Parisians came in large numbers to witness the execution, both on the route and at the site of the guillotine.

In the neighbourhood of the present-day ''rue de Cléry'', the Baron de Batz, a supporter of the former royal family who had financed the flight to Varennes

The Flight to Varennes (French: fuite de Varennes) during the night of 20–21 June 1791 was a significant event in the French Revolution in which the French royal family—comprising Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, the Dauphin Louis Charles, ...

, had summoned 300 royalists to enable the former king's escape. Louis was to be hidden in a house in the ''rue de Cléry'' belonging to the Count of Marsan. The Baron leaped forward calling "Follow me, my friends, let us save the King!", but his associates had been denounced and only a few had been able to turn up. Three of them were killed, but de Batz managed to escape.

The convoy continued on its way along the boulevards

A boulevard is a type of broad avenue (landscape), avenue planted with rows of trees, or in parts of North America, any urban highway or wide road in a commerce, commercial district.

In Europe, boulevards were originally circumferential roads ...

and the ''rue de la Révolution'' (now ''rue Royale

Rue Royale (French for "Royal Street") may refer to several streets:

* Rue Royale, Brussels, Belgium

* Rue Royale, Lyon, France

*Rue Royale, Paris

The Rue Royale () is a short street in Paris, France, running between the Place de la Concorde a ...

''). Louis' carriage arrived at the Place de la Révolution at around 10:15 a.m., stopping in front of a scaffold installed between the Champs-Élysées

The Avenue des Champs-Élysées (, ; ) is an Avenue (landscape), avenue in the 8th arrondissement of Paris, France, long and wide, running between the Place de la Concorde in the east and the Place Charles de Gaulle in the west, where the Arc ...

and a pedestal, where a statue of his grandfather, Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached maturity (then defi ...

, once stood until it was toppled in 1792. The scaffold was placed in an empty space surrounded by guns and ''fédérés'', with the people being kept at a distance. 20,000 men were deployed to guard the area.

Execution

Louis exited the carriage and was received by the executioner Charles-Henri Sanson, and then took off his frock coat and

Louis exited the carriage and was received by the executioner Charles-Henri Sanson, and then took off his frock coat and cravat Cravat, cravate or cravats may refer to:

* Cravat (early), forerunner neckband of the modern necktie

* Cravat, British name for what in American English is called an ascot tie

* Cravat bandage, a triangular bandage

* Cravat (horse) (1935–1954) ...

. After initially refusing to permit Sanson and his assistants to bind his hands together, the former king was ultimately convinced by Edgeworth, and his own handkerchief was used instead of rope. The executioner's men then cut his hair and opened his shirt's collar. Accompanied by drum rolls, Louis climbed the stairs of the scaffold and joined Sanson and his four assistants on the platform.

After walking to the edge of the scaffold, Louis signaled to the drummers to stop and proclaimed his innocence to the crowd and expressed his concern for the future of France. He would have continued but a drum roll was ordered by Santerre, and the resulting noise made his final words difficult to understand. The order has also been attributed to others, including Santerre's aide-de-camp Dugazon

Jean-Henri Gourgaud (15 November 1746 – 19 October 1809) was a French actor under the stage name Dugazon, the son of Pierre-Antoine Gourgaud, the director of military hospitals there and also an actor.

He began his career in the provinces, m ...

, maréchal de camp Beaufranchet d'Ayat, and the drummer Pierrard. The executioners fastened Louis to the guillotine's bench (''bascule''), positioning his neck beneath the device's yoke (''lunette'') to hold it in place. At 10:22 a.m., the device was activated and the blade swiftly decapitated him. One of Sanson's assistants grabbed his severed head out of the receptacle into which it fell and exhibited it to the cheering crowd. Some of the spectators shouted "Long live the Nation!", "Long live the Republic!", and "Long live Liberty!", and gun salutes were fired while a few danced the farandole

The farandole (; ) is an open-chain community dance popular in Provence, France. It bears similarities to the gavotte, jig, and tarantella. The carmagnole of the French Revolution is a derivative.

Etymology

No satisfactory derivation has bee ...

.

Witness quotes

Henry Essex Edgeworth

Edgeworth, Louis' Irish confessor, wrote in his memoirs:Charles-Henri Sanson

The executionerCharles-Henri Sanson

Charles-Henri Sanson, full title ''Chevalier Charles-Henri Sanson de Longval'' (; 15 February 1739 – 4 July 1806), was the royal executioner of France during the reign of King Louis XVI, as well as high executioner of the First French Republic. ...

responded to the story by offering his own version of events in a letter dated 20 February 1793. The account of Sanson states:

In his letter, published along with its French mistakes in the ''Thermomètre'' of Thursday, 21 February 1793, Sanson emphasises that the King "bore all this with a composure and a firmness which has surprised us all. I remained strongly convinced that he derived this firmness from the principles of the religion by which he seemed penetrated and persuaded as no other man."

Henri Sanson

In hisCauserie

Causerie (from French, "talk, chat") is a literary style of short informal essays mostly unknown in the English-speaking world. A causerie is generally short, light and humorous and is often published as a newspaper column (although it is not defi ...

s, Alexandre Dumas

Alexandre Dumas (born Alexandre Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie, 24 July 1802 – 5 December 1870), also known as Alexandre Dumas , was a French novelist and playwright.

His works have been translated into many languages and he is one of the mos ...

refers to a meeting circa 1830 with Henri Sanson, eldest son of Charles-Henri Sanson, who had also been present at the execution.

His son Henri Sanson was appointed Executioner of Paris from April 1793, and executed Marie Antoinette.

Jacques Roux

Jacques Roux

Jacques Roux (; 21 August 1752 – 10 February 1794) was a radical Roman Catholic Red priest who took an active role in politics during the French Revolution. He skillfully expounded the ideals of popular democracy and classless society to cro ...

, a radical Enragé and member of the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (, ) was a French revolutionary government that seized power in Paris on 18 March 1871 and controlled parts of the city until 28 May 1871. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard (France), Nation ...

, was assigned to write a report on Louis' death. In his report, he wrote:

We hose assigned to lead Louis to the guillotinewent to the Temple. There we announced to the tyrant ouisthat the hour of execution had arrived. He asked to be alone for a few minutes with his confessor. He wanted to give us a package to turn over to you he Paris Commune we made the observation that we were only charged with taking him to the scaffold. He answered: "This is proper." He turned the package over to one of our colleagues, asked that we look after his family, and asked that Cléry, his ''valet-de-chambre,'' be that of the queen; hurriedly he then said: "my wife." In addition, he asked that his former servants at Versailles not be forgotten. He said to Santerre: "Let us go." He crossed one courtyard on foot and climbed into a carriage in the second. On the way the most profound silence reigned. Nothing of note happened. We went up to the office of the Marine to prepare the official report of the execution. Capet was never out of our sight up till the guillotine. He arrived at 10 hours 10 minutes; it took him three minutes to get out of the carriage. He wanted to speak to the people but Santerre wouldn't allow it. His head fell. The citizens dipped their pikes and their handkerchiefs in his blood.Santerre is then quoted as saying:

We have just given you an exact account of what occurred. I have only praise for the armed force, which was extremely obedient. Louis Capet wanted to speak of commiseration to the people, but I prevented him so the king could receive his execution.

Leboucher

Speaking toVictor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

in 1840, a man called Leboucher, who had arrived in Paris from Bourges

Bourges ( ; ; ''Borges'' in Berrichon) is a commune in central France on the river Yèvre (Cher), Yèvre. It is the capital of the Departments of France, department of Cher (department), Cher, and also was the capital city of the former provin ...

in December 1792 and was present at the execution of Louis XVI, recalled vividly:

Louis-Sébastien Mercier

In ''Le nouveau Paris'',Mercier

Mercier is French for ''notions dealer'' or ''haberdasher'', and may refer to:

People

* Agnès Mercier, French curler and coach

*Annick Mercier (born 1964), French curler

* Amanda H. Mercier (born 1975), American Judge

*Armand Mercier, (1933–201 ...

describes the execution of Louis XVI in these words:

Burial in the cemetery of the Madeleine

The body of Louis XVI was immediately transported to the old Church of the Madeleine (demolished in 1799), since the legislation in force forbade burial of his remains beside those of his father, the Dauphin Louis de France, at

The body of Louis XVI was immediately transported to the old Church of the Madeleine (demolished in 1799), since the legislation in force forbade burial of his remains beside those of his father, the Dauphin Louis de France, at Sens

Sens () is a Communes of France, commune in the Yonne Departments of France, department in Bourgogne-Franche-Comté in north-central France, 120 km southeast from Paris.

Sens is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture and the second la ...

. Two vicars who had sworn fealty to the Revolution held a short memorial service at the church. One of them, Damoureau, stated in evidence:

On 21 January 1815, during the First Bourbon Restoration

The First Restoration was a period in French history that saw the return of the House of Bourbon to the throne, between the abdication of Napoleon in the spring of 1814 and the Hundred Days in March 1815. The regime was born following the victor ...

, Louis XVI and his wife's remains were re-buried in the Basilica of Saint-Denis

The Basilica of Saint-Denis (, now formally known as the ) is a large former medieval abbey church and present cathedral in the commune of Saint-Denis, a northern suburb of Paris. The building is of singular importance historically and archite ...

where in 1816 his brother, King Louis XVIII

Louis XVIII (Louis Stanislas Xavier; 17 November 1755 – 16 September 1824), known as the Desired (), was King of France from 1814 to 1824, except for a brief interruption during the Hundred Days in 1815. Before his reign, he spent 23 y ...

, had a funerary monument erected by Edme Gaulle

Edme Gaulle (1762,1760 in some sources Langres - January 1841, Paris) was a French sculptor.

Life

He began by studying drawing with Francois Devosge at the school in Dijon, then going to follow Jean Guillaume Moitte's course at the École des B ...

.

Jacques de Molay

A popular but apocryphal legend holds that as soon as the guillotine fell, an anonymousFreemason

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

leaped on the scaffolding, plunged his hand into the blood, splashed drips of it onto the crown, and shouted, "''Jacques de Molay

Jacques de Molay (; 1240–1250 – 11 or 18 March 1314), also spelled "Molai",Demurger, pp. 1–4. "So no conclusive decision can be reached, and we must stay in the realm of approximations, confining ourselves to placing Molay's date of birth ...

, tu es vengé!''" (usually translated as, "Jacques de Molay, thou art avenged"). De Molay (died 1314), the last Grand Master of the Knights Templar

The grand master of the Knights Templar was the supreme commander of the holy order, starting with founder Hugues de Payens. Some held the office for life while others resigned the office to pass the rest of their life in monasteries or diploma ...

, had reportedly cursed Louis' ancestor Philip the Fair

Philip IV (April–June 1268 – 29 November 1314), called Philip the Fair (), was King of France from 1285 to 1314. By virtue of his marriage with Joan I of Navarre, he was also King of Navarre and Count of Champagne as Philip I from ...

, after the latter had sentenced him to burn at the stake

A burn is an injury to skin, or other tissues, caused by heat, electricity, chemicals, friction, or ionizing radiation (such as sunburn, caused by ultraviolet radiation). Most burns are due to heat from hot fluids (called scalding), solids, ...

based on false confessions. The story spread widely and the phrase remains in use today to indicate "the triumph of reason and logic over religious superstition".

Today

The area where Louis XVI and later (16 October 1793)Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette (; ; Maria Antonia Josefa Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last List of French royal consorts, queen of France before the French Revolution and the establishment of the French First Republic. She was the ...

were buried, in the cemetery of the Church of the Madeleine, is today the "Square Louis XVI" greenspace, containing the classically self-effacing Expiatory Chapel completed in 1826 during the reign of Louis' youngest brother Charles X Charles X may refer to:

* Charles X of France (1757–1836)

* Charles X Gustav (1622–1660), King of Sweden

* Charles, Cardinal de Bourbon (1523–1590), recognized as Charles X of France but renounced the royal title

See also

*

* King Charle ...

. The crypt altar stands above the exact spot where the remains of the royal couple were originally laid to rest. The chapel narrowly escaped destruction on politico-ideological grounds during the violently anti-clerical period at the beginning of the 20th century.

References

Bibliography

* Hugo, Victor, ''The Memoirs of Victor Hugo'' (1899) * Necker, Anne Louise Germaine, ''Considerations on the principal events of the French Revolution'' (1818) * Thompson, J.M., ''English Witnesses of the French Revolution'' (1938)Paul and Pierrette Girault de Coursac

Paul Girault de Coursac (4 December 1916 – 16 March 2001) and Pierrette Girault de Coursac (''née'' Rachou; 11 November 1927 – 14 March 2010) were two French historians who specialised in the lives of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette.

Views

...

have written a number of works on Louis XVI, including:

* ''Louis XVI, Roi Martyr'' (1982) Tequi

* ''Louis XVI, un Visage retrouvé'' (1990) O.E.I.L.

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Louis 16, Execution 1790s in Paris 1793 events of the French RevolutionLouis XVI

Louis XVI (Louis-Auguste; ; 23 August 1754 – 21 January 1793) was the last king of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. The son of Louis, Dauphin of France (1729–1765), Louis, Dauphin of France (son and heir- ...

Louis XVI

Louis XVI (Louis-Auguste; ; 23 August 1754 – 21 January 1793) was the last king of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. The son of Louis, Dauphin of France (1729–1765), Louis, Dauphin of France (son and heir- ...

Louis XVI

Public executions