Escot House on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Escot in the parish of

Escot in the parish of

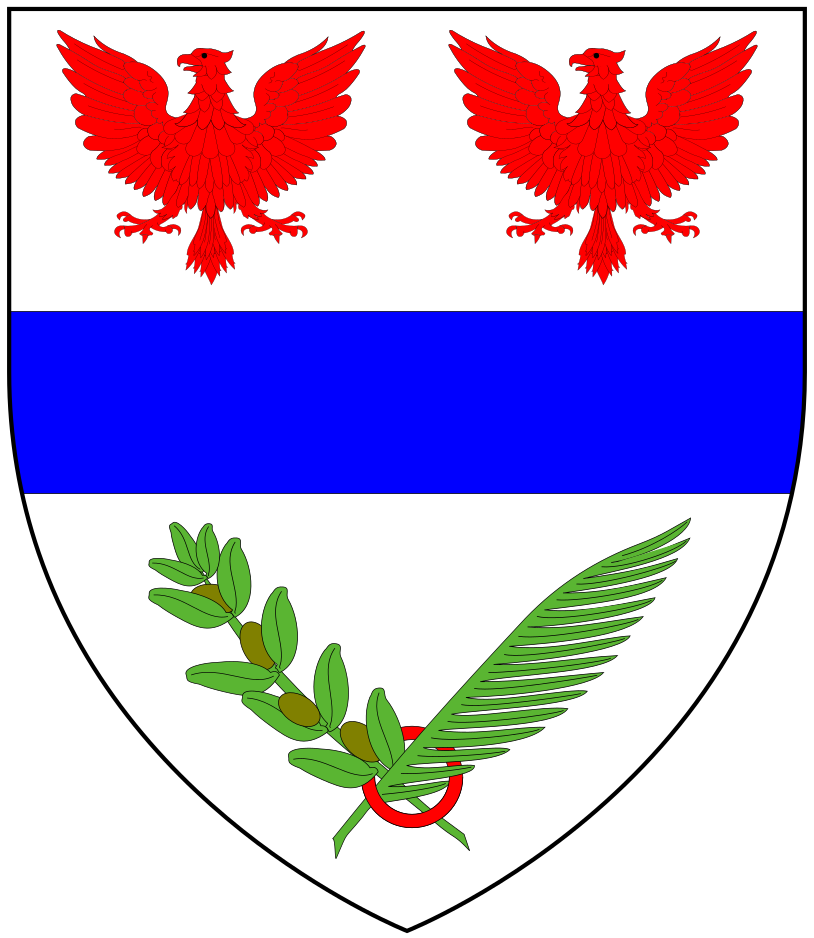

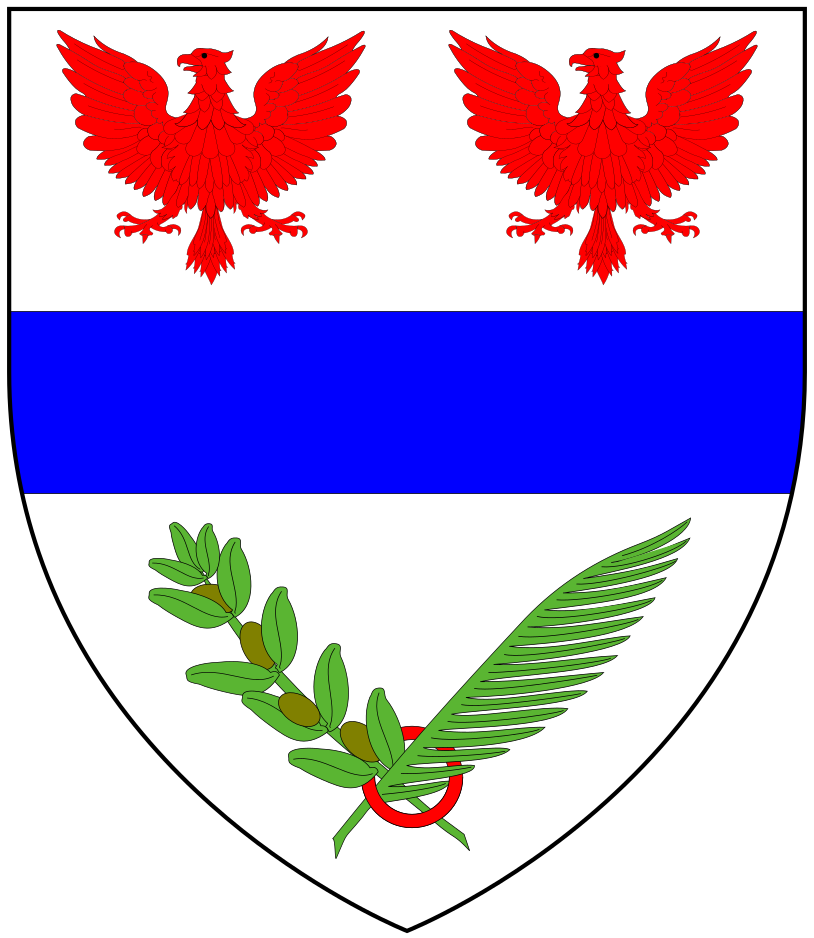

The estate then passed to the family of Beauchamp of Ryme in Dorset, a junior branch of the Beauchamp feudal barons of Hatch Beauchamp in Somerset. Thomas Beauchamp (son of Sir John Beauchamp (1315–1349)) died without children, when his heirs to one

The estate then passed to the family of Beauchamp of Ryme in Dorset, a junior branch of the Beauchamp feudal barons of Hatch Beauchamp in Somerset. Thomas Beauchamp (son of Sir John Beauchamp (1315–1349)) died without children, when his heirs to one

Both moieties were purchased by Richard Chanon, who married Margaret Dyer, widow of a certain Swaine. His son and heir was Phillip Chanon (died 1622), who married Frances Calmady, daughter of Richard Calmady (died 1586) of Farwood in the parish of Talaton,Vivian, p.167 MP for

Both moieties were purchased by Richard Chanon, who married Margaret Dyer, widow of a certain Swaine. His son and heir was Phillip Chanon (died 1622), who married Frances Calmady, daughter of Richard Calmady (died 1586) of Farwood in the parish of Talaton,Vivian, p.167 MP for

The building of a new mansion house was commenced in 1684 by

The building of a new mansion house was commenced in 1684 by

:From the road which ran through a very wide avenue of oaks which were at so great a distance from one another as to exhibit the noblest specimens of this tree ''the Glory of the Forest'', in all their beauty and luxuriance, the house was beheld to considerable advantage, seated on a gently rising slope just beyond a piece of water, which being of an oval figure detracted in a most glaring manner from the beauty which the scenery would otherwise have possess'd...The walls are formed of brick with freestone mouldings and a variety of ornaments...a light and not inelegant air pervades the whole, which united with its many rural beauties, gave me much pleasure and excited my admiration". As a

*Channon, L., ''Escot: The Fall and Rise of a Country Estate'', published by Ottery Heritage, Devon, 201

*Greenaway, Winifred O., ''The Kennaways of Escot'', published in ''Devon Historian'', Vol.46, April 1993, pp. 9–11 * Colen Campbell, Campbell, Colen, ''

Escot in the parish of

Escot in the parish of Talaton

Talaton is a village and a civil parish in the English county of Devon. It lies approximately 6 miles to the west of Honiton, 3 miles to the north of Ottery St Mary, 2 miles to the west of Feniton and 2 miles to the east of Whimple. The parish c ...

, near Ottery St Mary

Ottery St Mary, known as "Ottery", is a town and civil parish in the East Devon district of Devon, England, on the River Otter, about east of Exeter on the B3174. At the 2001 census, the parish, which includes the villages of Metcombe, Fair ...

in Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devon is ...

, is an historic estate. The present mansion house known as Escot House is a grade II listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Ir ...

building built in 1837 by Sir John Kennaway, 3rd Baronet

Sir John Henry Kennaway, 3rd Baronet, (6 June 1837 – 6 September 1919) was an English Conservative Party politician.

Early life and education

Kennaway was born on 6 June 1837 in Park Crescent, London, England, to Sir John Kennaway, 2nd ...

to the design of Henry Roberts, to replace an earlier house built in about 1680 by Sir Walter Yonge, 3rd Baronet

Sir Walter Yonge, 3rd Baronet (1653 – 18 July 1731) of Escot in the parish of Talaton, Devon, was an English landowner and Whig politician who sat in the English and British House of Commons between 1679 and 1710.

Early life

Yonge was bapti ...

(1653–1731) of Great House

A great house is a large house or mansion with luxurious appointments and great retinues of indoor and outdoor staff. The term is used mainly historically, especially of properties at the turn of the 20th century, i.e., the late Victorian or ...

in the parish of Colyton, Devon, to the design of Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath active as a scientist, natural philosopher and architect, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganisms in 1665 using a compound microscope that h ...

, which burned down in 1808. Today it remains the home of the Kennaway baronets.Kidd, Charles, ''Debrett's peerage & Baronetage'' 2015 Edition, London, 2015, p.B454

Escot House is currently used as a wedding and conference venue, with Wildwood Escot (a family attraction) being situated next door within the grounds of Escot estate).

History

The estate or manor of Escot is not listed in theDomesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

of 1086.

de Escote

The earliest holder of the estate was the ''de Escote'' family which, as was usual, took its surname from the estate. The Devon historianPole

Pole may refer to:

Astronomy

*Celestial pole, the projection of the planet Earth's axis of rotation onto the celestial sphere; also applies to the axis of rotation of other planets

* Pole star, a visible star that is approximately aligned with th ...

(died 1635) states that it "hath taken his name from the situacion", presumably meaning that it was a cott

Primo Water Corporation (formerly Cott Corporation) is an American-Canadian water company offering multi-gallon bottled water, water dispensers, self-service refill water machines, and water filtration appliances. The company is headquartered in ...

(mediaeval farmstead) on the east side of the manor of Talaton. In 1249 it was occupied by the widow ''Domina Lucia de Escote'' (Latin: Lady Lucy de Escote), who was succeeded by her son Baldwyn de Lestre.

Beauchamp

moiety

Moiety may refer to:

Chemistry

* Moiety (chemistry), a part or functional group of a molecule

** Moiety conservation, conservation of a subgroup in a chemical species

Anthropology

* Moiety (kinship), either of two groups into which a society is ...

each became the descendants of his two sisters:Pole, p.180

*Joan Beauchamp, wife of Sir Robert Chalons, whose share was said to have passed to an unnamed member of the Carwitham family.

*Elizabeth Beauchamp, who married twice, firstly to Richard Branscombe, secondly to William Fortescue of Whympston

Whympston (anciently Wimpstone, Wymondston, Wimston, Wymston, etc), in the parish of Modbury in Devon, England, is a historic manor. In the 12th century, it became the earliest English seat of the prominent Norman family of Fortescue, influ ...

in the parish of Modbury

Modbury is a large village, ecclesiastical parish, civil parish and former manor situated in the South Hams district of the county of Devon in England. Today due to its large size it is generally referred to as a "town" although the parish co ...

, Devon, by whom she had two sons, William Fortescue of Whympston and Sir John Fortescue, Captain of the Castle of Meaux in France under King Henry V (1413–1422), who was the ancestor of the Earls Fortescue.

Chanon

Both moieties were purchased by Richard Chanon, who married Margaret Dyer, widow of a certain Swaine. His son and heir was Phillip Chanon (died 1622), who married Frances Calmady, daughter of Richard Calmady (died 1586) of Farwood in the parish of Talaton,Vivian, p.167 MP for

Both moieties were purchased by Richard Chanon, who married Margaret Dyer, widow of a certain Swaine. His son and heir was Phillip Chanon (died 1622), who married Frances Calmady, daughter of Richard Calmady (died 1586) of Farwood in the parish of Talaton,Vivian, p.167 MP for Plympton

Plympton is a suburb of the city of Plymouth in Devon, England. It is in origin an ancient stannary town. It was an important trading centre for locally mined tin, and a seaport before the River Plym silted up and trade moved down river to P ...

in 1554, second son of John Calmady of Calmady in the parish of Wembury

Wembury is a village on the south coast of Devon, England, very close to Plymouth Sound. Wembury is located south of Plymouth. Wembury is also the name of the peninsula in which the village is situated. The village lies in the administrative dis ...

, Devon. Escot descended to the latter's son and heir Richard Chanon (born 1584), who married Margerie Lawrence, daughter of Sir Edward Lawrence of Grange House

Grange House (also known as Grangepans, Grange, Old Grange, and Grange Hamilton) was an estate house near Bo'ness, West Lothian

West Lothian ( sco, Wast Lowden; gd, Lodainn an Iar) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland, and was one of ...

, near Purbeck, Dorset (son and heir of Oliver Lawrence (died 1559), MP), by whom he had children.

Yonge

The building of a new mansion house was commenced in 1684 by

The building of a new mansion house was commenced in 1684 by Sir Walter Yonge, 3rd Baronet

Sir Walter Yonge, 3rd Baronet (1653 – 18 July 1731) of Escot in the parish of Talaton, Devon, was an English landowner and Whig politician who sat in the English and British House of Commons between 1679 and 1710.

Early life

Yonge was bapti ...

(1653–1731) of Great House

A great house is a large house or mansion with luxurious appointments and great retinues of indoor and outdoor staff. The term is used mainly historically, especially of properties at the turn of the 20th century, i.e., the late Victorian or ...

in the parish of Colyton, Devon, and was completed in 1688. It is generally stated the architect was Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath active as a scientist, natural philosopher and architect, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganisms in 1665 using a compound microscope that h ...

,Pevsner but Colvin quotes in his ''Dictionary of Architects'' that in 1684 a certain "William Taylor" was contracted to "contrive, designe, and draw out in paper and supervise the building of the house, for which he was paid £200". Little is known of Taylor but Colvin states that he was almost certainly responsible for the rebuilding of Halswell House in Somerset. It was a brick house of rectangular form, about by , the facade of which is recorded in a detailed drawing published in the 1715 edition of ''Vitruvius Britannicus

Colen Campbell (15 June 1676 – 13 September 1729) was a pioneering Scottish architect and architectural writer, credited as a founder of the Georgian style. For most of his career, he resided in Italy and England. As well as his architectura ...

'' (see above). Rev. John Swete

Rev. John Swete (born John Tripe) (baptised 13 August 1752 – 25 October 1821) of Oxton House, Kenton in Devon, was a clergyman, landowner, artist, antiquary, historian and topographer and author of the ''Picturesque Sketches of Devon'' consis ...

(died 1821) of Oxton House in the parish of Kenton, Devon, visited the house in 1794 during one of his ''Picturesque Tours'' and arrived one or two weeks before the estate was about to be sold at auction, when marquees had been set up on the front lawn to house the crowds of prospective buyers. It had been advertised for several months in various newspapers. The seller was Sir George Yonge, 5th Baronet

Sir George Yonge, 5th Baronet, KCB, PC (17 July 1731 – 25 September 1812), of Escot House in the parish of Talaton in Devon, England, was a British Secretary at War (1782–1783 and 1783–1794). He succeeded to his father's baronetcy ...

(1731–1812), grandson of the builder. Swete remarked in his ''Travel Journal'': "From the sight of the tents I assumed a notion that Sir George with some of his friends was come once more to greet the Lares

Lares ( , ; archaic , singular ''Lar'') were guardian deities in ancient Roman religion. Their origin is uncertain; they may have been hero-ancestors, guardians of the hearth, fields, boundaries, or fruitfulness, or an amalgam of these.

Lares ...

of his ancestors". Swete remarked as follows concerning the house::From the road which ran through a very wide avenue of oaks which were at so great a distance from one another as to exhibit the noblest specimens of this tree ''the Glory of the Forest'', in all their beauty and luxuriance, the house was beheld to considerable advantage, seated on a gently rising slope just beyond a piece of water, which being of an oval figure detracted in a most glaring manner from the beauty which the scenery would otherwise have possess'd...The walls are formed of brick with freestone mouldings and a variety of ornaments...a light and not inelegant air pervades the whole, which united with its many rural beauties, gave me much pleasure and excited my admiration". As a

connoisseur

A connoisseur (French traditional, pre-1835, spelling of , from Middle-French , then meaning 'to be acquainted with' or 'to know somebody/something') is a person who has a great deal of knowledge about the fine arts; who is a keen appreciator o ...

of landscaping, Swete mused on what improvements might have been made by "Mr Brown" (Capability Brown

Lancelot Brown (born c. 1715–16, baptised 30 August 1716 – 6 February 1783), more commonly known as Capability Brown, was an English gardener and landscape architect, who remains the most famous figure in the history of the English lan ...

) to the park, and made a watercolour of the scene (see at right), now in the Devon Record Office.

Kennaway

Sir John Kennaway, 1st Baronet (1758–1836)

Shortly after Swete's visit, as he recorded in his Journal, the estate was purchased for the sum of £26,000 (sic) by Sir John Kennaway, 1st Baronet (1758–1836), a returningNabob

A nabob is a conspicuously wealthy man deriving his fortune in the east, especially in India during the 18th century with the privately held East India Company.

Etymology

''Nabob'' is an Anglo-Indian term that came to English from Urdu, poss ...

(like his contemporary Sir Robert Palk, 1st Baronet

Sir Robert Palk, 1st Baronet (December 1717 – 29 April 1798) of Haldon House in the parish of Kenn, in Devon, England, was an officer of the British East India Company who served as Governor of the Madras Presidency. In England he served as ...

(1717–1798) of Haldon House

Haldon House (pronounced: "Hol-don") on the eastern side of the Haldon Hills in the parishes of Dunchideock and Kenn, near Exeter in Devon, England, was a large Georgian country house largely demolished in the 1920s. The surviving north wing of ...

). He was from Exeter and had made a fortune in the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and aroun ...

where he served as British Resident at the Court of the Nizam

The Nizams were the rulers of Hyderabad from the 18th through the 20th century. Nizam of Hyderabad (Niẓām ul-Mulk, also known as Asaf Jah) was the title of the monarch of the Hyderabad State ( divided between the state of Telangana, Mar ...

of Hyderabad

Hyderabad ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Telangana and the ''de jure'' capital of Andhra Pradesh. It occupies on the Deccan Plateau along the banks of the Musi River (India), Musi River, in the northern part ...

. The house was destroyed by fire in 1808, which occurred while the Kennaway family was away, resulting in almost total destruction of the structure and furnishings. One notable survival rescued from the fire was the prized portrait of Lord Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805), styled Viscount Brome between 1753 and 1762 and known as the Earl Cornwallis between 1762 and 1792, was a British Army general and official. In the United ...

, Governor-General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

and commander-in-chief in India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

, presented to the first Baronet when he left India.Channon Although Sir John was a director of a local Fire Insurance company, his own house was uninsured as he had not yet signed the documents for his own policy. His is said to have told the unfortunate young female house-guest who caused the fire by drying her clothing too close to the fireplace in her bedroom: "My dear, I forgive you, but I never wish to see you again". The author William Makepiece Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray (; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was a British novelist, author and illustrator. He is known for his satirical works, particularly his 1848 novel '' Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portrait of British society, and t ...

was an acquaintance of the 1st Baronet and his children, and in 1852, long after his death, he used his memories of former visits to Escot in writing his novel ''Pendennis

''The History of Pendennis: His Fortunes and Misfortunes, His Friends and His Greatest Enemy'' (1848–50) is a novel by the English author William Makepeace Thackeray. It is set in 19th-century England, particularly in London. The main ...

''. The protagonist "Major Pendennis" was based on the 1st Baronet, and features of the house and grounds appear in the book, thinly disguised. Thus the nearby town of Ottery St Mary he called "Clavering" and Escot itself became "Clavering Park"; the oval pond in front of the house became "Carp Pond", the River Tale the "Brawl".

Sir John Kennaway, 2nd Baronet (1797–1873)

The present house was built in 1838 bySir John Kennaway, 2nd Baronet

''Sir'' is a formal honorific address in English for men, derived from Sire in the High Middle Ages. Both are derived from the old French "Sieur" (Lord), brought to England by the French-speaking Normans, and which now exist in French only a ...

(1797–1873) (whose father had died two years earlier in 1836), to the design of Henry Roberts. The new house was built on the same site, but the ground-floor was raised on higher foundations and a terrace was created to the south and west. The principal entrance was moved to the east side, looking across the parkland. On the north side the hillside was cut back to create various service buildings. It is built of Flemish bond brick and appears yellow on the forward aspects but red to the rear and service buildings. The roof is of slate, with limestone ashlar

Ashlar () is finely dressed (cut, worked) stone, either an individual stone that has been worked until squared, or a structure built from such stones. Ashlar is the finest stone masonry unit, generally rectangular cuboid, mentioned by Vitr ...

chimney stacks. The building has two stories with basement and cellars, and is constructed on a square plan, being two rooms wide and two rooms deep. The entrance on the east side gives onto a hallway containing the main staircase. The house has multi-pane sash window

A sash window or hung sash window is made of one or more movable panels, or "sashes". The individual sashes are traditionally paned windows, but can now contain an individual sheet (or sheets, in the case of double glazing) of glass.

History

...

s with limestone architraves

In classical architecture, an architrave (; from it, architrave "chief beam", also called an epistyle; from Ancient Greek, Greek ἐπίστυλον ''epistylon'' "door frame") is the lintel (architecture), lintel or beam (structure), beam t ...

. The building was designated grade II listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Ir ...

on 24 October 1988. In 1844 he constructed bridges over the River Tale flowing through the estate, and erected several miles of fencing in the park. He took a great interest in gardening and in 1858 started to plant azaleas and rhododendrons. In 1860 part of the northern edge of the park was lost when used for the track of the new Exeter to Yeovil railway. In 1858 he built a glass-sided aquarium, made possibly by advances in the manufacture of strong glass.

Sir John Kennaway, 3rd Baronet (1837–1919)

Sir John Kennaway, 3rd Baronet (1837–1919), son, lived through the agricultural depression of the 1870s and sold off some of the estate's farms to the tenants and increased rents on others. He was a Conservative Party politician whose longevity in Parliament brought him the distinction of becomingFather of the House of Commons

Father of the House is a title that has been traditionally bestowed, unofficially, on certain members of some legislatures, most notably the House of Commons in the United Kingdom. In some legislatures the title refers to the longest continuously- ...

. He was noted for his long and luxuriant beard.

Sir John Kennaway, 4th Baronet (1879–1956)

Sir John Kennaway, 4th Baronet (1879–1956), son, who inherited Escot one year after the end ofWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, and whose first major objective became repairing the damage to the estate caused by the War, for example the loss of many trees cut down to assist the war-effort. At the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

in 1939 Sir John joined the Home Guard

Home guard is a title given to various military organizations at various times, with the implication of an emergency or military reserve force, reserve force raised for local defense.

The term "home guard" was first officially used in the America ...

, being too old to serve in the main forces. Escot became a home for 40 evacuee children from London, under management of the Waifs and Strays Society

The Children's Society, formally the Church of England Children's Society, is a United Kingdom national children's charity (registered No. 221124) allied to the Church of England.

The charity's two governing objectives are to:

# directly impr ...

, and the Kennaway family moved out temporarily to Fairmile, a house on the estate. However, Sir John enjoyed visiting the children at Escot and having seen the joy induced in one boy to whom he had given a coin as reward for finding his penknife dropped in the walled garden, he made it a point thereafter to periodically drop his penknife on purpose.

Sir John Lawrence Kennaway, 5th Baronet (1933–2017)

Sir John Lawrence Kennaway, 5th Baronet (1933 – October 22, 2017), son, who in 1956 inherited from his father an estate which was barely financially viable, partly due to highdeath duties

An inheritance tax is a tax paid by a person who inherits money or property of a person who has died, whereas an estate tax is a levy on the estate (money and property) of a person who has died.

International tax law distinguishes between an e ...

payable. His main interest was in forestry, rather than in gardening, the passion of his ancestors. In the interests of economy he demolished the derelict and redundant old nursery at the rear of the house, but retained the remainder of the service buildings next to it, including the old dairy, the bread oven and the bothy

A bothy is a basic shelter, usually left unlocked and available for anyone to use free of charge. It was also a term for basic accommodation, usually for gardeners or other workers on an estate. Bothies are found in remote mountainous areas of Sco ...

. In 1987, with the agreement of his family, he handed over the running of the estate to his son and retired to live in Malvern.

John-Michael Kennaway, 6th Baronet (born 1962)

John-Michael Kennaway, 6th Baronet (born 1962), has been running the estate since January 1984, but took over formally from his father in 1987. He attended Hampshire College of Agriculture and is an expert in aquaculture (fish farming). In 1988 he married Lucy Bradshaw-Smith (born 1966), from nearby Ottery St Mary, trained in catering, who with her husband "shared a love of the natural world and a selfless commitment to the Escot cause". They discontinued the aquaculture business and in 1989 filled in the fish ponds in the walled garden, which became a Victorian rose garden. They opened instead a pet and ornamental fish business known as "Escot Aquatic Centre", situated in the disusedlinhay

A linhay ( ) is a type of farm building found particularly in Devon and Somerset, south-west England. It is characterised as a two-storeyed building with an open front, with ''tallet'' or hay-loft above and livestock housing below. It often has ...

of Home Farm, which in 1992 was nominated UK Pet Centre of the Year. This business concentrated on the sale of ornamental fish and a range of pets and pet supplies. The gardens were opened to the paying public.

The couple have faced many setbacks including:

*1990 hurricane, which blew down about 5,000 trees on the estate and 200 metres of garden wall.

*1997: the building of the new A30 dual-carriageway road through the park, opposed by the celebrated environmental protester Daniel Hooper (better known as ''Swampy''), whose activities were "very much supported by the local community". This cut off the house from Escot Church.

*2000: a national outbreak of Spring viraemia of carp which resulted in a government order to destroy the entire fish stock of eight ponds, and disinfection by hydrochloric acid and quick lime which destroyed the pond plumbing system and caused a loss of £30,000.

*2008: flash-flooding which swept away two of the 1844 brick bridges over the river and three others.

Otters and wild boar were introduced to the estate and boosted visitor numbers to 4,500 in 1990. A successful new water garden design and construction business was established, trading as "Gentlemen Prefer Ponds". In 1993 the "Coach House Restaurant" was established. The house itself is now hired out for a variety of events, including a Policeman's Ball, wedding receptions from 1994, Civil Marriage ceremonies from 1996, conferences, etc. Parts of the upper floors are let as flats. In 2002 the estate hosted "Beautiful Days", a new music and arts festival comprising a mix of music, art and crafts, which received 15,000 visitors. From 2007 various pop concerts have been held in the grounds.

Escot parish

The ecclesiasticalparish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or ...

of Escot was created in 1839, comprising small areas taken from the surrounding parishes of Ottery St Mary, Feniton and Talaton. The parish church of St. Philip and St. James was built by Sir John Kennaway, 2nd Baronet

''Sir'' is a formal honorific address in English for men, derived from Sire in the High Middle Ages. Both are derived from the old French "Sieur" (Lord), brought to England by the French-speaking Normans, and which now exist in French only a ...

on his estate and was consecrated in 1840. Rev. P.W. Douglas was appointed perpetual curate and Rev. J. Furnival was appointed the first vicar of Escot in 1868.

Escot Park

Escot Park, the surrounding 220-acre (89 ha) park designed byCapability Brown

Lancelot Brown (born c. 1715–16, baptised 30 August 1716 – 6 February 1783), more commonly known as Capability Brown, was an English gardener and landscape architect, who remains the most famous figure in the history of the English lan ...

in the 18th century, and the gardens, are open to the public. Escot Park is used for events including the annual " Beautiful Days" music festival and occasional other outdoor music and theatre performances.

References

{{reflist ;Sources * Gray, Todd & Rowe, Margery (Eds.), Travels in Georgian Devon: The Illustrated Journals of The ReverendJohn Swete

Rev. John Swete (born John Tripe) (baptised 13 August 1752 – 25 October 1821) of Oxton House, Kenton in Devon, was a clergyman, landowner, artist, antiquary, historian and topographer and author of the ''Picturesque Sketches of Devon'' consis ...

, 1789-1800, 4 vols., Tiverton, 1999, Vol.2, pp. 94–6

* Polwhele, Richard, ''History of Devonshire'', Vol.3, pp. 271–2

Further reading

* Lysons, Daniel & Lysons, Samuel, Magna Britannia, Vol.6, ''Devonshire'', London, 1822, re Talato*Channon, L., ''Escot: The Fall and Rise of a Country Estate'', published by Ottery Heritage, Devon, 201

*Greenaway, Winifred O., ''The Kennaways of Escot'', published in ''Devon Historian'', Vol.46, April 1993, pp. 9–11 * Colen Campbell, Campbell, Colen, ''

Vitruvius Britannicus

Colen Campbell (15 June 1676 – 13 September 1729) was a pioneering Scottish architect and architectural writer, credited as a founder of the Georgian style. For most of his career, he resided in Italy and England. As well as his architectura ...

'', Vol.1, 1715, pp. 78–9 (illustration)

*Badeslade, Thomas & Rocque, J., ''Vitruvius Britannicus

Colen Campbell (15 June 1676 – 13 September 1729) was a pioneering Scottish architect and architectural writer, credited as a founder of the Georgian style. For most of his career, he resided in Italy and England. As well as his architectura ...

'', Vol.2, 1739 (illustration)

Grade II listed buildings in Devon

Country houses in Devon

Houses completed in 1838

Historic estates in Devon