Escherichia Virus CC31 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Escherichia virus CC31'', formerly known as ''Enterobacter virus CC31'', is a dsDNA

In order for viral genomic replication to occur, ''CC31'' needs to enter the host, ''Escherichia'' ''coli''. Due to the lack of an outer envelope, the virion must find an alternate way to enter its host. It does this by penetrating the membrane of the bacterium with its tail region. First, the long tail fibers ejecting from the top of the base plate attach to the cell membrane of the bacterium. The small tail fibers underneath base plate then attach to the membrane, initiating a

In order for viral genomic replication to occur, ''CC31'' needs to enter the host, ''Escherichia'' ''coli''. Due to the lack of an outer envelope, the virion must find an alternate way to enter its host. It does this by penetrating the membrane of the bacterium with its tail region. First, the long tail fibers ejecting from the top of the base plate attach to the cell membrane of the bacterium. The small tail fibers underneath base plate then attach to the membrane, initiating a

Once inside the cell, replication can begin. The virus starts by breaking down all ''E. coli'' genetic material. This is known as the

Once inside the cell, replication can begin. The virus starts by breaking down all ''E. coli'' genetic material. This is known as the

bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a phage (), is a virus that infects and replicates within bacteria. The term is derived . Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that Capsid, encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome, and may have structu ...

of the subfamily ''Tevenvirinae

''Tevenvirinae'' is a subfamily of viruses in the family ''Straboviridae'' of class ''Caudoviricetes''. The subfamily was previously placed in the morphology-based family ''Myoviridae'', which was found to be paraphyletic in genome studies and ab ...

'' responsible for infecting the bacteria family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

of Enterobacteriaceae

Enterobacteriaceae is a large family (biology), family of Gram-negative bacteria. It includes over 30 genera and more than 100 species. Its classification above the level of Family (taxonomy), family is still a subject of debate, but one class ...

. It is one of two discovered viruses of the genus '' Karamvirus'', diverging away from the previously discovered '' T4virus'', as a clonal complex (CC).Bielak, E.M., Hasman, H. and Aarestrup, F.M., 2012. ''Diversity and epidemiology of plasmids from Enterobacteriaceae from human and non-human reservoirs'' (Doctoral dissertation, Technical University of DenmarkDanmarks Tekniske Universitet, National Food InstituteFødevareinstituttet, Division of Epidemiology and Microbial GenomicsAfdeling for Epidemiologi og Genomisk Mikrobiologi). ''CC31'' was first isolated from ''Escherichia coli

''Escherichia coli'' ( )Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. is a gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus '' Escherichia'' that is commonly fo ...

'' B strain S/6/4 and is primarily associated with ''Escherichia

''Escherichia'' ( ) is a genus of Gram-negative, non-Endospore, spore-forming, Facultative anaerobic organism, facultatively anaerobic, rod-shaped bacteria from the family Enterobacteriaceae. In those species which are inhabitants of the gastroin ...

,'' even though is named after ''Enterobacter

''Enterobacter'' is a genus of common Gram-negative, Facultative anaerobic organism, facultatively anaerobic, bacillus (shape), rod-shaped, non-spore-forming bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae. Cultures are found in soil, water, sewage, ...

.''

Viral classification and structure

''Enterobacter virus CC31'' is adsDNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

virus lacking an RNA intermediate. The dsDNA is contained within an icosahedral capsid of proteins, but the virus lacks an envelope. It is in the order ''Caudovirales

''Caudoviricetes'' is a class of viruses known as tailed viruses and head-tail viruses (''cauda'' is Latin for "tail"). It is the sole representative of its own phylum, ''Uroviricota'' (from ''ouros'' (ουρος), a Greek word for "tailed" + ...

'', being that it is a bacteriophage with a protein sheath and tail used to infect host cells. ''Caudovirales'' genetic material is contained within an icosahedral capsid

A capsid is the protein shell of a virus, enclosing its genetic material. It consists of several oligomeric (repeating) structural subunits made of protein called protomers. The observable 3-dimensional morphological subunits, which may or may ...

resting on top of the sheath and tail. ''CC31'' is in the ''Myoviridae

''Myoviridae'' was a family of bacteriophages in the order '' Caudovirales''. The family ''Myoviridae'' and order '' Caudovirales'' have now been abolished, with the term myovirus now used to refer to the morphology of viruses in this former famil ...

'' family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

due to its lack of envelope

An envelope is a common packaging item, usually made of thin, flat material. It is designed to contain a flat object, such as a letter (message), letter or Greeting card, card.

Traditional envelopes are made from sheets of paper cut to one o ...

, linear genome, and long, helical, permanent tail subunits. ''Tevenvirinae

''Tevenvirinae'' is a subfamily of viruses in the family ''Straboviridae'' of class ''Caudoviricetes''. The subfamily was previously placed in the morphology-based family ''Myoviridae'', which was found to be paraphyletic in genome studies and ab ...

'' is the relatively large (43 genera

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family as used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In binomial nomenclature, the genus name forms the first part of the binomial s ...

) subfamily

In biological classification, a subfamily (Latin: ', plural ') is an auxiliary (intermediate) taxonomic rank, next below family but more inclusive than genus. Standard nomenclature rules end botanical subfamily names with "-oideae", and zo ...

''CC13'' falls underneath. Finally, ''Cc13virus'' is the relatively new genus associated with ''Enterobacter virus CC31''.

Genome

''Enterobacter virus CC31'' has a double stranded linear DNA (dsDNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

) genome consisting of 165,540 nucleotide base pairs. The bases account for 287 genes that are capable of making 279 different proteins using 8 tRNAs

Transfer ribonucleic acid (tRNA), formerly referred to as soluble ribonucleic acid (sRNA), is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes). In a cell, it provides the physical link between the genet ...

. 93% of the genetic material is homologous with ''Enterobacter virus PG7,'' the other ''Tevenvirinae'', and 74% of the material is homologous with the close relative '' Enterobacteria phage T-4.'' 120 new open reading frame

In molecular biology, reading frames are defined as spans of DNA sequence between the start and stop codons. Usually, this is considered within a studied region of a prokaryotic DNA sequence, where only one of the six possible reading frames ...

s (ORFs) were identified across the base pairs that were added to the ''Enterobacteria phage'' pan-genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a pan-genome (pangenome or supragenome) is the entire set of genes from all strains within a clade. More generally, it is the union of all the genomes of a clade. The pan-genome can be broken do ...

. It is currently the only phage, that is not a T-even bacteriophage, capable of encoding for glycosyltransferase

Glycosyltransferases (GTFs, Gtfs) are enzymes ( EC 2.4) that establish natural glycosidic linkages. They catalyze the transfer of saccharide moieties from an activated nucleotide sugar (also known as the "glycosyl donor") to a nucleophilic gl ...

s.

Genetic modification

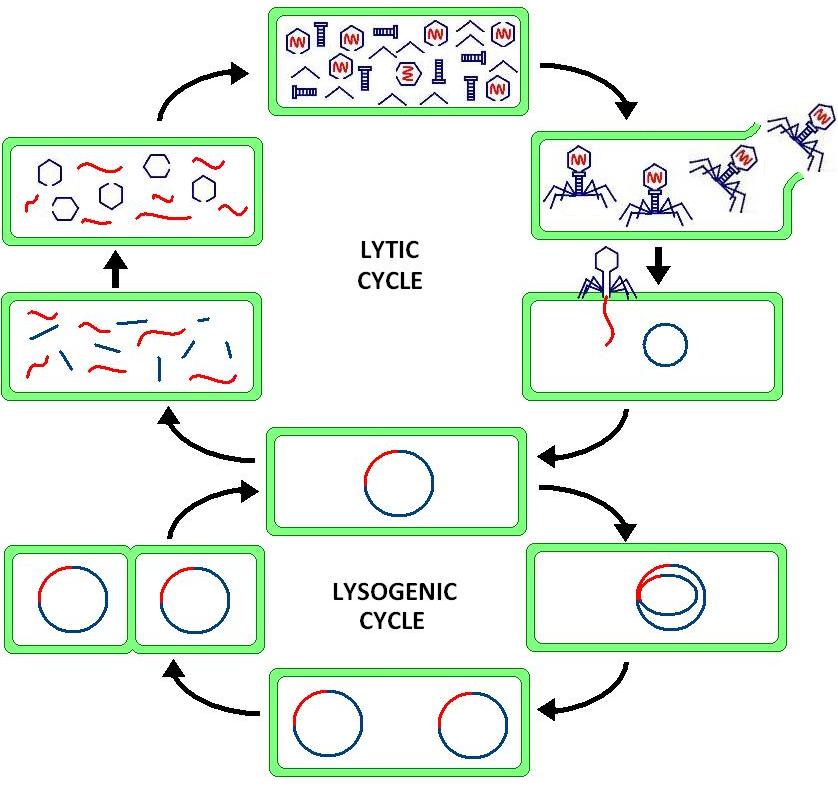

The ''CC31'' is capable of integrating its genetic material with the host's. This stage, known as thelysogenic cycle

Lysogeny, or the lysogenic cycle, is one of two cycles of Virus, viral reproduction (the lytic cycle being the other). Lysogeny is characterized by integration of the bacteriophage nucleic acid into the host Bacteria, bacterium's genome or form ...

, halts particle formation, and allows for the virus's genetic material to amplify across many subsequent bacterium generations. The integration of the viral DNA happens non-homologously, forming bubbles of single stranded DNA. As DNA replication, crossing over, and cellular division occurs, the viral DNA is reshuffled with cellular DNA. This results in horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). HGT is an important factor in the e ...

between the virus and cell, resulting in the evolution of the virus and the bacterium. The viral DNA also develops minute deletions, immunity regions, and silent genetic regions due to the non-homologous binding of the DNA. These change in virus' genetic material can either inhibit or promote future replication.

Pathogenesis

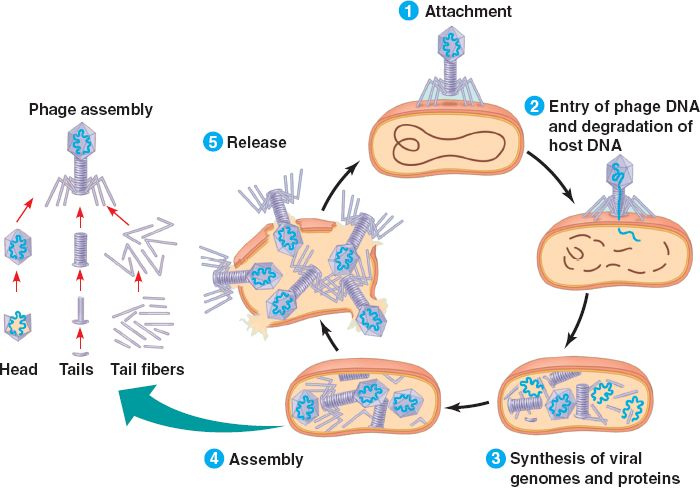

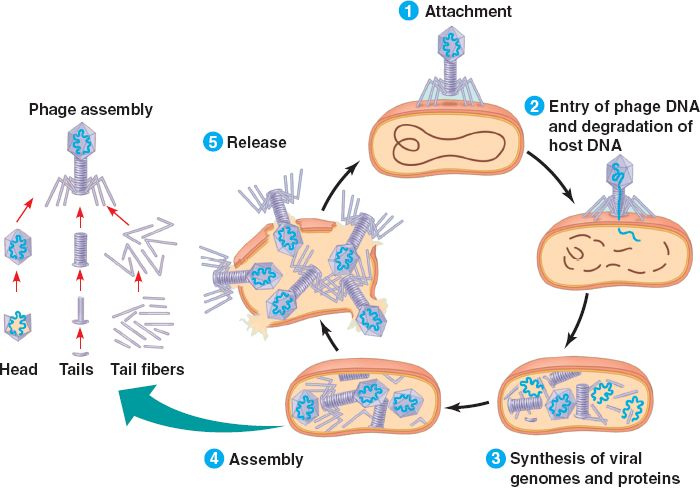

In order for viral genomic replication to occur, ''CC31'' needs to enter the host, ''Escherichia'' ''coli''. Due to the lack of an outer envelope, the virion must find an alternate way to enter its host. It does this by penetrating the membrane of the bacterium with its tail region. First, the long tail fibers ejecting from the top of the base plate attach to the cell membrane of the bacterium. The small tail fibers underneath base plate then attach to the membrane, initiating a

In order for viral genomic replication to occur, ''CC31'' needs to enter the host, ''Escherichia'' ''coli''. Due to the lack of an outer envelope, the virion must find an alternate way to enter its host. It does this by penetrating the membrane of the bacterium with its tail region. First, the long tail fibers ejecting from the top of the base plate attach to the cell membrane of the bacterium. The small tail fibers underneath base plate then attach to the membrane, initiating a conformational change

In biochemistry, a conformational change is a change in the shape of a macromolecule, often induced by environmental factors.

A macromolecule is usually flexible and dynamic. Its shape can change in response to changes in its environment or othe ...

of the base plate to a six-point star from the previous hexagon conformation. This forces the sheath to undergo a conformational change to contract and effectively stretching the membrane. While this is occurring, the rigid tube underneath the sheath remains stagnant to push against the membrane. Digestion of the inner membrane occurs with the assistance of the tail's lysozyme

Lysozyme (, muramidase, ''N''-acetylmuramide glycanhydrolase; systematic name peptidoglycan ''N''-acetylmuramoylhydrolase) is an antimicrobial enzyme produced by animals that forms part of the innate immune system. It is a glycoside hydrolase ...

s. As this continues, the inner tube breaks through the membrane and allows the viral DNA to flow into the cytoplasm

The cytoplasm describes all the material within a eukaryotic or prokaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, including the organelles and excluding the nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The material inside the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell a ...

of the bacterium.

Lytic cycle

lytic cycle

The lytic cycle ( ) is one of the two cycles of viral reproduction (referring to bacterial viruses or bacteriophages), the other being the lysogenic cycle. The lytic cycle results in the destruction of the infected cell and its membrane. Bacter ...

. The virus can now occupy the cell of the ''E. coli'' without being inhibited by proteins or enzymes of the host. The ''CC30'' genetic material is then capable of using the residue ''E. coli'' proteins to assist with viral replication. ''Enterobacter virus CC31'' has most of the genes responsible for coding proteins to induce gene expression and replication: endonuclease

In molecular biology, endonucleases are enzymes that cleave the phosphodiester bond within a polynucleotide chain (namely DNA or RNA). Some, such as deoxyribonuclease I, cut DNA relatively nonspecifically (with regard to sequence), while man ...

, RNA polymerase

In molecular biology, RNA polymerase (abbreviated RNAP or RNApol), or more specifically DNA-directed/dependent RNA polymerase (DdRP), is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reactions that synthesize RNA from a DNA template.

Using the e ...

, DNA polymerase

A DNA polymerase is a member of a family of enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of DNA molecules from nucleoside triphosphates, the molecular precursors of DNA. These enzymes are essential for DNA replication and usually work in groups to create t ...

, RNA primase, DNA ligase

DNA ligase is a type of enzyme that facilitates the joining of DNA strands together by catalyzing the formation of a phosphodiester bond. It plays a role in repairing single-strand breaks in duplex DNA in living organisms, but some forms (such ...

, topoisomerase

DNA topoisomerases (or topoisomerases) are enzymes that catalyze changes in the topological state of DNA, interconverting relaxed and supercoiled forms, linked (catenated) and unlinked species, and knotted and unknotted DNA. Topological issues in ...

, and DNA helicase

Helicases are a class of enzymes that are vital to all organisms. Their main function is to unpack an organism's genetic material. Helicases are motor proteins that move directionally along a nucleic double helix, separating the two hybridized ...

. Therefore, ''CC31'' does not require access to ''E. coli''parasitic

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives (at least some of the time) on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The ent ...

fashion. This allows for rapid formation of virus particles within the empty cell. DNA is amplified, while proteins are made for the virion construction. Protein subunits combine into domains to make the individual components of the virion. The viral particles begin to combine once overcrowding of the cell occurs. The ''E. coli'' cell will lyse Lyse may refer to:

People

* Lyse Doucet (born 1939), Canadian journalist, presenter and correspondent for BBC World Service radio and BBC World television

* Lyse Richer (born 1958), Canadian administrator and music teacher

* Carl L. Lyse (1899– ...

due to over-population, allowing the virions to burst out of the cell and move on to the next host.

Lysogenic cycle

The virus is also capable of taking a different pathway to replicate its DNA known as thelysogenic cycle

Lysogeny, or the lysogenic cycle, is one of two cycles of Virus, viral reproduction (the lytic cycle being the other). Lysogeny is characterized by integration of the bacteriophage nucleic acid into the host Bacteria, bacterium's genome or form ...

. Instead of destroying the cellular DNA, the viral DNA integrates itself within it with the assistance of integrase

Retroviral integrase (IN) is an enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme ...

, to become a silent provirus

A provirus is a virus genome that is integrated into the DNA of a host cell. In the case of bacterial viruses (bacteriophages), proviruses are often referred to as prophages. However, proviruses are distinctly different from prophages and these te ...

. This integration forms non-homologous single stranded bubbles of viral DNA. These regions are susceptible to damage, resulting in frame shifts, minute deletions, immunity regions, and silent genetic regions. These modifications, patterned with horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). HGT is an important factor in the e ...

between ''E. coli'' DNA and ''CC30'' DNA, allow for evolution to occur for the virus and bacterium. This patience illustrated by the virus allows for it to amplify its genetic material significantly through many ''E. coli'' generations. Also, as the integrated viral DNA is translated

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between ''transla ...

into mRNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of Protein biosynthesis, synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is ...

, proteins are synthesized and are readily available for future virion formation. Once a stressor is induced onto the cell, the integration weakens and subsequently releases the viral genetic material. The virus now enters the lytic cycle

The lytic cycle ( ) is one of the two cycles of viral reproduction (referring to bacterial viruses or bacteriophages), the other being the lysogenic cycle. The lytic cycle results in the destruction of the infected cell and its membrane. Bacter ...

and begins replication in the numerous bacteria cells it now occupies. As the lytic cycle progresses and the virions begin to infect new cells, the acquired ''E. coli'' genetic material can now be transduced into other cells as the bacteriophage reenters the lysogenic cycle.

Interactions with ''Enterobacteriaceae''

Beta-lactamase

Beta-lactamases (β-lactamases) are enzymes () produced by bacteria that provide multi-resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics such as penicillins, cephalosporins, cephamycins, monobactams and carbapenems ( ertapenem), although carbapene ...

(blaCMY-2) is an enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

responsible for providing antibiotic resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR or AR) occurs when microbes evolve mechanisms that protect them from antimicrobials, which are drugs used to treat infections. This resistance affects all classes of microbes, including bacteria (antibiotic resis ...

to penicillin

Penicillins (P, PCN or PEN) are a group of beta-lactam antibiotic, β-lactam antibiotics originally obtained from ''Penicillium'' Mold (fungus), moulds, principally ''Penicillium chrysogenum, P. chrysogenum'' and ''Penicillium rubens, P. ru ...

s, cephalosporin

The cephalosporins (sg. ) are a class of β-lactam antibiotics originally derived from the fungus '' Acremonium'', which was previously known as ''Cephalosporium''.

Together with cephamycins, they constitute a subgroup of β-lactam antibio ...

s, and carbapenem

Carbapenems are a class of very effective antibiotic agents most commonly used for treatment of severe bacterial infections. This class of antibiotics is usually reserved for known or suspected multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacterial infections. Si ...

s. Hydrolysis

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution reaction, substitution, elimination reaction, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water ...

of the antibiotics by blaCMY-2 results in the resistance. This enzyme is present and expressed in '' Salmonella choleraesuis'', a bacterium primarily associated with infecting cattle and poultry. This gene presents a global issue for the consumption of food products. The antibiotic resistance of ''Salmonella'' makes it difficult to treat these infections if they were to inflict humans. The genetic material coding for the blaCMY-2 enzyme was not ancestrally part of the bacterium's genome, but was acquired by the IncI1 plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria and ...

.

''E. coli'' local to the human's GI tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascular system. T ...

have acquired this same antibiotic resistance using the blaCMY-2 enzyme. The sequence coding for the blaCMY-2 gene is a derivative of the IncI1 plasmid. The distinct divergence of ''E. coli'' and ''S. choleraesuis'' removes the possibility of this occurrence being from plasma transmission between the species. The acquisition of these sequences is a result of ''Enterobacter virus'' ''CC31''s ability to influence gene transduction.

With the plasma integrated into the bacterium DNA and the ''CC31'' in the lysogenic cycle

Lysogeny, or the lysogenic cycle, is one of two cycles of Virus, viral reproduction (the lytic cycle being the other). Lysogeny is characterized by integration of the bacteriophage nucleic acid into the host Bacteria, bacterium's genome or form ...

, genetic material is exchanged across subsequent generations. Random crossing over and gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). HGT is an important factor in the e ...

results in heterozygosity

Zygosity (the noun, zygote, is from the Greek "yoked," from "yoke") () is the degree to which both copies of a chromosome or gene have the same genetic sequence. In other words, it is the degree of similarity of the alleles in an organism.

Mos ...

of the bacteria and prophage

A prophage is a bacteriophage (often shortened to "phage") genome that is integrated into the circular bacterial chromosome or exists as an extrachromosomal plasmid within the bacterial cell (biology), cell. Integration of prophages into the bacte ...

. After a stressor is induced onto the cells and the virus enters the lytic cycle

The lytic cycle ( ) is one of the two cycles of viral reproduction (referring to bacterial viruses or bacteriophages), the other being the lysogenic cycle. The lytic cycle results in the destruction of the infected cell and its membrane. Bacter ...

to eventually lyse the cell, ''CC31'' is free to roam around the body to infect a different bacteria species and undergo random gene transfer once again. As this continues, variable gene fragments from the plasma and virus are transferred. These random gene transfers have resulted in adoption of the IncI1 and a new antibiotic resistant ''E. coli''.

References