Ernie Fletcher (1) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ernest Lee Fletcher (born November 12, 1952) is an American

As a result of legislative redistricting in 1996, Fletcher's district was consolidated with the one represented by fellow Republican Stan Cave. Rather than challenge a member of his own party, Fletcher decided to run for a seat representing Kentucky's 6th District in the

As a result of legislative redistricting in 1996, Fletcher's district was consolidated with the one represented by fellow Republican Stan Cave. Rather than challenge a member of his own party, Fletcher decided to run for a seat representing Kentucky's 6th District in the

In 2002, Fletcher was encouraged by Senator

In 2002, Fletcher was encouraged by Senator

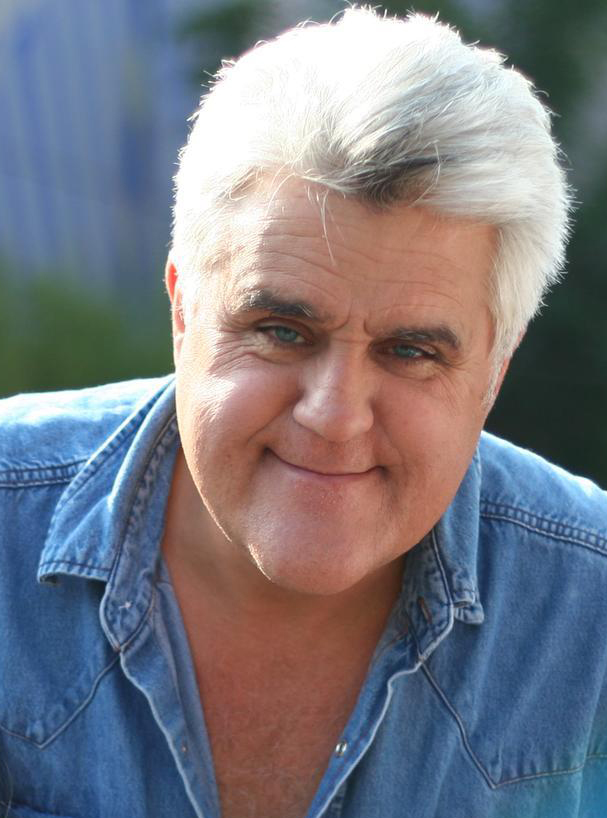

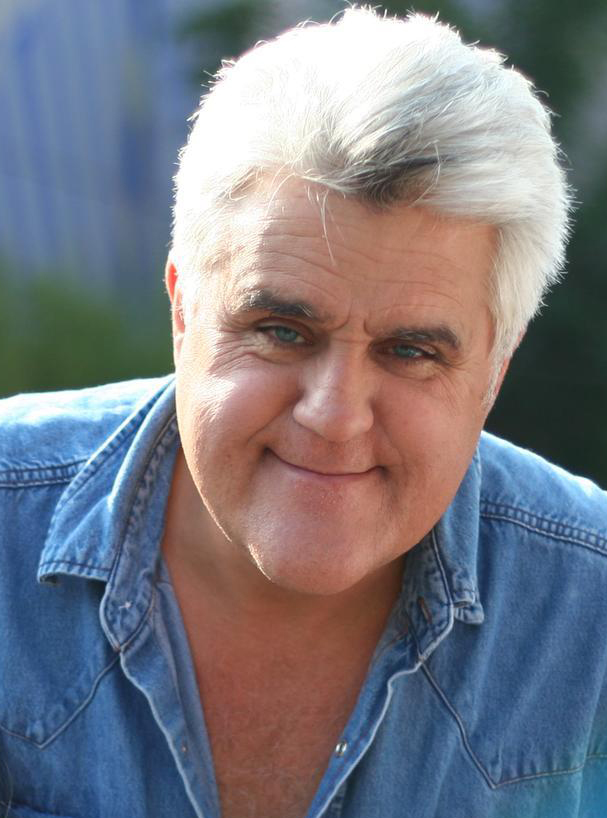

In July 2004, Fletcher announced a plan to unify the state's branding to improve its public perception.Biesk, "Leno Spot to Boost Image", p. K1 Shortly after the announcement, late-night comedians

In July 2004, Fletcher announced a plan to unify the state's branding to improve its public perception.Biesk, "Leno Spot to Boost Image", p. K1 Shortly after the announcement, late-night comedians

Follow the MoneyErnie Fletcher & Stephen B Pence 2006 campaign contributions

* , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Fletcher, Ernie 1952 births Living people Baptist ministers from the United States Baptists from Kentucky Republican Party governors of Kentucky Intelligent design advocates Military personnel from Kentucky Republican Party members of the Kentucky House of Representatives Politicians from Lexington, Kentucky People from Mount Sterling, Kentucky Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Kentucky United States Air Force officers University of Kentucky College of Medicine alumni Physicians from Kentucky 21st-century Kentucky politicians 20th-century American physicians 21st-century American physicians 21st-century members of the United States House of Representatives 20th-century members of the United States House of Representatives 20th-century members of the Kentucky General Assembly

physician

A physician, medical practitioner (British English), medical doctor, or simply doctor is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through the Medical education, study, Med ...

and politician who was the 60th governor of Kentucky from 2003 to 2007. He previously served three consecutive terms in the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

before resigning after being elected governor. A member of the Republican Party, Fletcher was a family practice physician and a Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

lay minister and is the second physician to be elected Governor of Kentucky; the first was Luke P. Blackburn

Luke Pryor Blackburn (June 16, 1816September 14, 1887) was an American physician, philanthropist, and politician from Kentucky. He was elected the 28th governor of Kentucky, serving from 1879 to 1883. Until the election of Ernie Fletcher in 200 ...

in 1879. He was also the first Republican governor of Kentucky since Louie Nunn

Louie Broady Nunn (March 8, 1924 – January 29, 2004) was an American politician who served as the 52nd governor of Kentucky. Elected in 1967, he was the only Republican to hold the office between the end of Simeon Willis's term in 1947 and ...

left office in 1971.

Fletcher graduated from the University of Kentucky

The University of Kentucky (UK, UKY, or U of K) is a Public University, public Land-grant University, land-grant research university in Lexington, Kentucky, United States. Founded in 1865 by John Bryan Bowman as the Agricultural and Mechanical ...

and joined the United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Air force, air service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is one of the six United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Tracing its ori ...

to pursue his dream of becoming an astronaut

An astronaut (from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'star', and (), meaning 'sailor') is a person trained, equipped, and deployed by a List of human spaceflight programs, human spaceflight program to serve as a commander or crew member of a spa ...

. He left the Air Force after budget cuts reduced his squadron's flying time and earned a degree in medicine, hoping to earn a spot as a civilian on a space mission. Deteriorating eyesight eventually ended those hopes, and he entered private practice as a physician and conducted services as a Baptist lay minister. He became active in politics and was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives

The Kentucky House of Representatives is the lower house of the Kentucky General Assembly. It is composed of 100 Representatives elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. Not more than two counties can be joined to form a ...

in 1994. Two years later he ran for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, but lost to incumbent Scotty Baesler

Henry Scott Baesler (born July 9, 1941) is an American Democratic politician and former Representative for the 6th district in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, including Lexington, Richmond, and Georgetown. He served as the Mayor of Lexington fr ...

. When Baesler retired to run for a seat in the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and House have the authority under Article One of the ...

, Fletcher again ran for the congressional seat and defeated Democratic state senator

A state senator is a member of a State legislature (United States), state's senate in the bicameral legislature of 49 U.S. states, or a member of the unicameral Nebraska Legislature.

History

There are typically fewer state senators than there ...

Ernesto Scorsone

Ernesto M. Scorsone (born February 15, 1952) is an LGBT advocate, American lawyer, politician and retired judge from Kentucky.

Early life and career

Ernesto Scorsone was born in Palermo, Italy, on February 15, 1952. His family immigrated to th ...

. He soon became one of the House Republican caucus's leaders regarding health care legislation, particularly the Patients' Bill of Rights

Patient rights consist of enforceable duties that healthcare professionals and healthcare business persons owe to Patient, patients to provide them with certain services or benefits. When such services or benefits become rights instead of simply ...

.

Fletcher was elected governor in 2003 over state Attorney General

The state attorney general in each of the 50 U.S. states, of the District of Columbia, federal district, or of any of the Territories of the United States, territories is the chief legal advisor to the State governments of the United States, sta ...

Ben Chandler

Albert Benjamin Chandler III (born September 12, 1959) is an American lawyer and politician who served as the United States House of Representatives, United States representative for from 2004 to 2013. A United States Democratic Party, Democrat, ...

. Early in his term, Fletcher achieved some savings to the state by reorganizing the executive branch

The executive branch is the part of government which executes or enforces the law.

Function

The scope of executive power varies greatly depending on the political context in which it emerges, and it can change over time in a given country. In ...

. He proposed an overhaul to the state tax code in 2004, but was unable to get it passed through the General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of presby ...

. When Republicans in the state senate

In the United States, the state legislature is the legislative branch in each of the 50 U.S. states.

A legislature generally performs state duties for a state in the same way that the United States Congress performs national duties at ...

insisted on tying the reforms to the state budget, the legislature adjourned without passing either and the state operated under an executive spending plan drafted by Fletcher until 2005, when both the budget and the reforms were passed.

Later in 2005, Attorney General Greg Stumbo

Gregory D. Stumbo (born August 14, 1951) is an American lawyer and former speaker of the Kentucky House of Representatives. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as Kentucky attorney general from 2004 to 2008. He was the Democratic candidat ...

, the state's highest-ranking Democrat, launched an investigation into whether the Fletcher administration's hiring practices violated the state's merit system

The merit system is the process of promoting and hiring government employees based on their ability to perform a job, rather than on their political connections. It is the opposite of the spoils system.

History

The earliest known example of a ...

. A grand jury

A grand jury is a jury empowered by law to conduct legal proceedings, investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. A grand jury may subpoena physical evidence or a person to testify. A grand ju ...

returned several indictment

An indictment ( ) is a formal accusation that a person has committed a crime. In jurisdictions that use the concept of felonies, the most serious criminal offense is a felony; jurisdictions that do not use that concept often use that of an ind ...

s against members of Fletcher's staff, and eventually against Fletcher himself. Fletcher issued pardons

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the j ...

for anyone on his staff implicated in the investigation, but did not pardon himself. Though the investigation was ended by an agreement between Fletcher and Stumbo in late 2006, it continued to overshadow Fletcher's re-election bid in 2007

2007 was designated as the International Heliophysical Year and the International Polar Year.

Events

January

* January 1

**Bulgaria and Romania 2007 enlargement of the European Union, join the European Union, while Slovenia joins the Eur ...

. After turning back a challenge in the Republican primary

Primary or primaries may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Primary (band), from Australia

* Primary (musician), hip hop musician and record producer from South Korea

* Primary Music, Israeli record label

Work ...

by former Congresswoman Anne Northup

Anne Meagher Northup (born January 22, 1948) is an American Republican politician and educator from the Commonwealth of Kentucky. From 1997 to 2007, she represented the Louisville-centered 3rd congressional district of Kentucky in the Unite ...

, Fletcher lost the general election to Democrat Steve Beshear

Steven Lynn Beshear ( ; born September 21, 1944) is an American attorney and politician. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as the 61st governor of Kentucky from 2007 to 2015. He served in the Kentucky House of Representatives from 1974 ...

. After his term as governor, he returned to the medical field as founder and CEO of Alton Healthcare. He is married and has two adult children.

Early life

Ernest Lee Fletcher was born inMount Sterling, Kentucky

Mount Sterling, often written as Mt. Sterling, is a home rule-class city in Montgomery County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 7,558 as of the 2020 census, up from 6,895 in 2010. It is the county seat of Montgomery County and the pr ...

, on November 12, 1952."Fletcher, Ernest L.". ''Biographical Directory of the United States Congress'' He was the third of four children born to Harold Fletcher Sr. and his wife, Marie.Mead, "Fletcher's Vision is Reaganesque", p. B1Estep, "Ernie Fletcher", p. 5 The family owned a farm and operated a general store

A general merchant store (also known as general merchandise store, general dealer, village shop, or country store) is a rural or small-town store that carries a general line of merchandise. It carries a broad selection of merchandise, someti ...

near the community of Means

Means may refer to:

* Means LLC, an anti-capitalist media worker cooperative

* Means (band), a Christian hardcore band from Regina, Saskatchewan

* Means, Kentucky, a town in the US

* Means (surname)

* Means Johnston Jr. (1916–1989), US Navy ...

. Harold Fletcher also worked for Columbia Gas.Kinney, "Dr., Preacher, Pilot...Gov?", p. K1 When Ernie was three weeks old, Harold was transferred to Huntington, West Virginia

Huntington is a city in Cabell County, West Virginia, Cabell and Wayne County, West Virginia, Wayne counties in the U.S. state of West Virginia. The County seat, seat of Cabell County, the city is located at the confluence of the Ohio River, O ...

. Two years later, the Fletchers returned to Robertson County, Kentucky

Robertson County is a county located in the U.S. Commonwealth of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 2,193. Its county seat is Mount Olivet. The county is named for George Robertson, a Kentucky Congressman from 1817 to 1821. ...

, where they lived until Ernie Fletcher began the first grade

First grade (also 1st Grade or Grade 1) is the first year of formal or compulsory education. It is the first year of elementary school, and the first school year after kindergarten. Children in first grade are usually 6–7 years old.

Examples ...

. The family moved once more and finally settled in Lexington.

Fletcher attended Lafayette High School in Lexington, where he was a member of the National Beta Club

The National Beta Club (often called "Beta Club" or simply "Beta") is an International honor society for 4th through 12th-grade students. Its purpose is to promote academic achievement, character, leadership, and service among elementary and secon ...

. During his senior year, he was an all-state saxophone

The saxophone (often referred to colloquially as the sax) is a type of single-reed woodwind instrument with a conical body, usually made of brass. As with all single-reed instruments, sound is produced when a reed on a mouthpiece vibrates to p ...

player and was elected prom

A promenade dance or prom is a formal dance party for graduating high school students at the end of the school year.

Students participating in the prom will typically vote for a ''prom king'' and ''prom queen''. Other students may be honored ...

king.Cross, p. 264 After graduating in 1970, he enrolled at the University of Kentucky

The University of Kentucky (UK, UKY, or U of K) is a Public University, public Land-grant University, land-grant research university in Lexington, Kentucky, United States. Founded in 1865 by John Bryan Bowman as the Agricultural and Mechanical ...

. He pledged and became a member of the Delta Tau Delta

Delta Tau Delta () is a United States–based international Greek letter college fraternity. Delta Tau Delta was founded at Bethany College, Bethany, Virginia, (now West Virginia) in 1858. The fraternity currently has around 130 collegiate chapt ...

fraternity. After his freshman year, he married his high school sweetheart, Glenna Foster. The couple had two children, Rachel and Ben, and four grandchildren.

Fletcher aspired to become an astronaut

An astronaut (from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'star', and (), meaning 'sailor') is a person trained, equipped, and deployed by a List of human spaceflight programs, human spaceflight program to serve as a commander or crew member of a spa ...

, and joined the Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps

The Air Force Reserve Officers' Training Corps (AFROTC) is one of the three primary commissioning sources for officers in the United States Air Force and United States Space Force, the other two being the United States Air Force Academy (USAFA ...

.Cross, p. 265 In 1974, he earned a Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, B.S., B.Sc., SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree that is awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Scienc ...

degree in mechanical engineering, graduating with top honors. After graduation, he joined the U.S. Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is one of the six United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Tracing its origins to 1 ...

. After flight training in Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

, he was stationed in Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

where he served as a F-4E Aircraft commander and NORAD

North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD ; , CDAAN), known until March 1981 as the North American Air Defense Command, is a combined organization of the United States and Canada that provides aerospace warning, air sovereignty, and pr ...

Alert Force commander."Kentucky Governor Ernie Fletcher". National Governors Association During the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, his duties included commanding squadrons to intercept Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

military aircraft. In 1980, as budget cutbacks were reducing his squadron's flying time, Fletcher turned down a regular commission in the Air Force. He left the Air Force with the rank of captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

, having received the Air Force Commendation Medal

The Commendation Medal is a mid-level United States military decoration presented for sustained acts of heroism or meritorious service. Each branch of the United States Armed Forces issues its own version of the Commendation Medal, with a fift ...

and the Outstanding Unit Award

The Air and Space Outstanding Unit Award (ASOUA) is one of the unit awards of the United States Air Force and United States Space Force. It was established in 1954 as the Air Force Outstanding Unit Award and was the first independent Air Force ...

.Trowbridge, "Kentucky's Military Governors"

Fletcher enrolled in the University of Kentucky College of Medicine

The University of Kentucky College of Medicine is a medical school based in Lexington, KY at the University of Kentucky's Chandler Medical Center.

The College operates four campuses; in addition to the main hub in Lexington, there are two full c ...

, hoping that a medical degree, along with a military background, would earn him a civilian spot on a space mission. In 1984, he graduated medical school with a Doctor of Medicine

A Doctor of Medicine (abbreviated MD, from the Latin language, Latin ) is a medical degree, the meaning of which varies between different jurisdictions. In the United States, and some other countries, the ''MD'' denotes a professional degree of ph ...

degree, but his deteriorating eyesight forced him to abandon his dreams of becoming an astronaut.

In 1983, the Lexington Primitive Baptist

Primitive Baptists – also known as Regular Baptists, Old School Baptists, Foot Washing Baptists, or, derisively, Hard Shell Baptists – are conservative Baptists adhering to a degree of Calvinist beliefs who coalesced out of the contr ...

church that Fletcher attended ordained him as a lay minister. In 1984, he opened a family medical practice in Lexington. Along with former classmate Dr. James D. B. George, he co-founded the South Lexington Family Physicians in 1987. For two years, he concurrently held the title of chief executive officer

A chief executive officer (CEO), also known as a chief executive or managing director, is the top-ranking corporate officer charged with the management of an organization, usually a company or a nonprofit organization.

CEOs find roles in variou ...

of the Saint Joseph Medical Foundation, an organization that solicits private gifts to Saint Joseph Regional Medical Center in Lexington. In 1989, Fletcher's church called him to become its unpaid pastor, but over the years, he grew to question some of the church's doctrines, desiring it to become more evangelistic. Consequently, he left the Primitive Baptist denomination in 1994 and joined the Porter Memorial Baptist Church, a Southern Baptist

The Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), alternatively the Great Commission Baptists (GCB), is a Christian denomination based in the United States. It is the world's largest Baptist organization, the largest Protestantism in the United States, Pr ...

congregation.

Legislative career

Through his church ministry, Fletcher became acquainted with a group ofsocial conservatives

Social conservatism is a political philosophy and a variety of conservatism which places emphasis on traditional social structures over social pluralism. Social conservatives organize in favor of duty, traditional values and social instit ...

that gained control of the Fayette County Republican Party in 1990. (Fayette County and the city of Lexington operate under the merged Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government). Fletcher accepted an invitation to become a member of the county Republican committee. In 1994, he was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives

The Kentucky House of Representatives is the lower house of the Kentucky General Assembly. It is composed of 100 Representatives elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. Not more than two counties can be joined to form a ...

, defeating incumbent Democrat Leslie Trapp

Leslie Combs Trapp (born September 18, 1954) is an American politician from Kentucky who was a member of the Kentucky House of Representatives from 1993 to 1995. Trapp was elected in 1992 after incumbent Republican representative Pat Freibert re ...

. He represented Kentucky's 78th District and served on the Kentucky Commission on Poverty and the Task Force on Higher Education. He was also chosen by Governor Paul E. Patton

Paul Edward Patton (born May 26, 1937) is an American politician who served as the 59th governor of Kentucky from 1995 to 2003. Because of a 1992 amendment to the Kentucky Constitution, he was the first governor eligible to run for a second te ...

to assist with reforming the state's health-care system.

As a result of legislative redistricting in 1996, Fletcher's district was consolidated with the one represented by fellow Republican Stan Cave. Rather than challenge a member of his own party, Fletcher decided to run for a seat representing Kentucky's 6th District in the

As a result of legislative redistricting in 1996, Fletcher's district was consolidated with the one represented by fellow Republican Stan Cave. Rather than challenge a member of his own party, Fletcher decided to run for a seat representing Kentucky's 6th District in the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Article One of th ...

later that year. After winning a three-way Republican primary

Primary or primaries may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Primary (band), from Australia

* Primary (musician), hip hop musician and record producer from South Korea

* Primary Music, Israeli record label

Work ...

by 4 votes over his closest opponent, he was defeated by incumbent Democrat Scotty Baesler

Henry Scott Baesler (born July 9, 1941) is an American Democratic politician and former Representative for the 6th district in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, including Lexington, Richmond, and Georgetown. He served as the Mayor of Lexington fr ...

by just over 25,000 votes. In 1998, Baesler resigned his seat to run for the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and House have the authority under Article One of the ...

seat vacated due to the retirement of Senator Wendell H. Ford

Wendell Hampton Ford (September 8, 1924 – January 22, 2015) was an American politician from Kentucky. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as Governor of Kentucky from 1971 to 1974, and as a member of the United States Senate for 24 ye ...

. Fletcher won the Republican primary for Baesler's seat by a wide margin. In the general election, Fletcher faced Democrat Ernesto Scorsone

Ernesto M. Scorsone (born February 15, 1952) is an LGBT advocate, American lawyer, politician and retired judge from Kentucky.

Early life and career

Ernesto Scorsone was born in Palermo, Italy, on February 15, 1952. His family immigrated to th ...

. The ''Lexington Herald-Leader

The ''Lexington Herald-Leader'' is a newspaper owned by the McClatchy Company and based in Lexington, Kentucky. According to the ''1999 Editor & Publisher International Yearbook'', the paid circulation of the ''Herald-Leader'' is the second larg ...

'' billed the race as "a classic joust between the left

Left may refer to:

Music

* ''Left'' (Hope of the States album), 2006

* ''Left'' (Monkey House album), 2016

* ''Left'' (Helmet album), 2023

* "Left", a song by Nickelback from the album ''Curb'', 1996

Direction

* Left (direction), the relativ ...

and the right

Rights are law, legal, social, or ethics, ethical principles of freedom or Entitlement (fair division), entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal sy ...

".Baniak, "6th District Race a Classic Contest Between Left, Right", p. D3 Fletcher was strongly opposed to abortion

Anti-abortion movements, also self-styled as pro-life movements, are involved in the abortion debate advocating against the practice of abortion and its legality. Many anti-abortion movements began as countermovements in response to the legal ...

, advocated a " flatter, fairer, simpler" tax system, and called for returning most federal education funding to local communities. Scorsone supported abortion rights

Abortion-rights movements, also self-styled as pro-choice movements, are movements that advocate for legal access to induced abortion services, including elective abortion. They seek to represent and support women who wish to terminate their p ...

, called a flat tax "too regressive", and favored national educational testing and standards. Fletcher defeated Scorsone by a vote of 104,046 to 90,033, with third-party candidate W. S. Krogdahl garnering 1,839 votes.

Within months of arriving in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, Fletcher was selected as the leadership liaison for the 17-member freshman class of Republican legislators.Gibson, "Ernie Fletcher", p. A1 He was appointed to the Committee on Education and Workforce, and John Boehner

John Andrew Boehner ( ; born , 1949) is an American politician who served as the 53rd speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 2011 to 2015. A member of the Republican Party, he served 13 terms as the U.S. representative ...

, chair of the committee's employer/employee relations subcommittee, chose Fletcher as his vice-chair. The committee's purpose is to oversee the rules for employer-paid health plans, among other issues, and although it is rare for a freshman legislator to attain a committee leadership post, Boehner cited Fletcher's experience in the medical field and work on reforming the Kentucky health care system as reasons for the appointment. Fletcher also served as a member of the House Committees on the Budget and Agriculture

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created ...

. In June 1999, he sponsored an amendment to a youth violence bill that allowed school districts to use federal funds to develop curricula which included elements designed to promote and enhance students' moral character

Moral character or character (derived from ) is an analysis of an individual's steady Morality, moral qualities. The concept of ''character'' can express a variety of attributes, including the presence or lack of virtues such as empathy, courag ...

; the amendment passed 422–1. Later, Fletcher was assigned to the Committee on Energy and Commerce

A committee or commission is a body of one or more persons subordinate to a deliberative assembly or other form of organization. A committee may not itself be considered to be a form of assembly or a decision-making body. Usually, an assembly o ...

and was selected as chairman of the Policy Subcommittee on Health.

During the debate over the proposed Patients' Bill of Rights

Patient rights consist of enforceable duties that healthcare professionals and healthcare business persons owe to Patient, patients to provide them with certain services or benefits. When such services or benefits become rights instead of simply ...

legislation, Fletcher opposed a Democratic proposal that would have allowed individuals to sue their health maintenance organization

In the United States, a health maintenance organization (HMO) is a medical insurance group that provides health services for a fixed annual fee. It is an organization that provides or arranges managed care for health insurance, self-funded hea ...

s (HMOs), favoring instead a more limited bill drafted by Republican leadership that expanded the patient's ability to appeal HMO decisions.Grunwald, "GOP Doctors in the House Put Patients Before Party", p. A1 Many doctors in the Republican legislative caucus felt their party's bill did not go far enough; Fletcher and Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

Senator Bill Frist

William Harrison Frist (born February 22, 1952) is an American physician, businessman, conservationist and policymaker who served as a United States Senator from Tennessee from 1995 to 2007. A member of the Republican Party, he also served as ...

were notable exceptions. Fletcher's position cost him the support of the Kentucky Medical Association (KMA)."Fletcher loses doctors' backing". ''The Kentucky Post'', p. 16A After contributing to his campaign against Scorsone in 1998, KMA backed Scotty Baesler's bid to regain his old seat from Fletcher in 2000. However, Baesler only captured 35 percent of the vote to Fletcher's 53 percent. The remaining 12 percent went to third-party candidate Gatewood Galbraith

Louis Gatewood Galbraith (January 23, 1947 – January 4, 2012) was an American author and attorney from the U.S. Commonwealth of Kentucky. He was a five-time political candidate for governor of Kentucky and a vocal advocate for legalization of ...

.

After the 2000 election, Fletcher crafted a compromise bill that allowed patients to sue their HMOs in federal court, capped pain and suffering

Pain and suffering is the legal term for the physical and emotional stress caused from an injury (see also pain and suffering).

Some damages that might come under this category would be: aches, temporary and permanent limitations on activity, ...

awards at $500,000, and eliminated punitive damage awards.Lockwood, "Fletcher's Patients' Rights Bill in Trouble" Despite an eventual compromise allowing patient lawsuits to go to state courts under certain circumstances and heavy lobbying in favor of Fletcher's bill by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

, the House refused to pass it, favoring an alternative proposal by Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

's Charlie Norwood

Charles Whitlow Norwood Jr. (July 27, 1941 – February 13, 2007) was an American politician who served as a Republican Party (United States), Republican member of the United States House of Representatives from 1995 until his death in 2007. At th ...

that was less restrictive on patient lawsuits.

Fletcher faced no major-party opposition in his re-election bid in 2002 after the only Democrat in the race, 24-year-old Roy Miller Cornett Jr., withdrew his candidacy.Lockwood, "Fletcher's Opponent Drops Out of Race", p. C3 Independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in Pennsylvania, United States

* Independentes (English: Independents), a Portuguese artist ...

Gatewood Galbraith again made the race; Libertarian

Libertarianism (from ; or from ) is a political philosophy that holds freedom, personal sovereignty, and liberty as primary values. Many libertarians believe that the concept of freedom is in accord with the Non-Aggression Principle, according ...

Mark Gailey also mounted a challenge.Wolfe, "Bates Can't Run in May Primary", pp. K1, K10 In the final vote tally, Fletcher received 115,522 votes to Galbraith's 41,853 and Gailey's 3,313.

2003 gubernatorial election

In 2002, Fletcher was encouraged by Senator

In 2002, Fletcher was encouraged by Senator Mitch McConnell

Addison Mitchell McConnell III (; born February 20, 1942) is an American politician and attorney serving as the senior United States senator from Kentucky, a seat he has held since 1985. McConnell is in his seventh Senate term and is the long ...

, the leader of Kentucky's Republican Party, to run for governor and formed an exploratory committee the same year.Cross, p. 266 On December 2, 2002, he announced that he would run on a ticket with McConnell aide Hunter Bates. Early in 2003, a Republican college student named Curtis Shain challenged Bates' candidacy on grounds that he did not meet the residency requirements set forth for the lieutenant governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

in the state constitution. Under the constitution, candidates for both governor and lieutenant governor must be citizens of the state for at least six years prior to the election. From August 1995 to February 2002, Bates and his wife rented an apartment in Alexandria, Virginia

Alexandria is an independent city (United States), independent city in Northern Virginia, United States. It lies on the western bank of the Potomac River approximately south of Washington, D.C., D.C. The city's population of 159,467 at the 2020 ...

while Bates was working for a law firm in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, and later, as McConnell's chief of staff.Brammer and Alessi, "Judge: Bates Can't be on Ballot", p. A1 Bob Heleringer, a former state representative from suburban Louisville and the running mate of Republican gubernatorial candidate Steve Nunn

Stephen Roberts Nunn (born November 4, 1952) is an American convicted murderer and former politician who served as the Deputy Secretary of Health and Family Services for the Commonwealth of Kentucky.

From 1991 to 2007, he was a Republican memb ...

, joined the suit as a plaintiff. In March 2003, an Oldham County judge ruled that Bates had not established residency in Kentucky. He cited the fact that from 1995 to 2002, Bates held a Virginia driver's license

A driver's license, driving licence, or driving permit is a legal authorization, or the official document confirming such an authorization, for a specific individual to operate one or more types of motorized vehicles—such as motorcycles, ca ...

, paid Virginia income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Tax ...

es, and "regularly" slept in his apartment in Virginia. Bates did not appeal the ruling because by allowing the judge to declare a vacancy on the ballot, Fletcher was able to name a replacement running mate, an option that would not have been afforded him had Bates withdrawn.Kinney, "Bates Won't Contest Ruling", K1

Fletcher chose Steve Pence

Stephen B. Pence (born December 22, 1953) is an American attorney who was the 53rd lieutenant governor of the Commonwealth of Kentucky from 2003 to 2007. He took office with fellow Republican Ernie Fletcher in December 2003.

Education

Pence r ...

, United States Attorney

United States attorneys are officials of the U.S. Department of Justice who serve as the chief federal law enforcement officers in each of the 94 U.S. federal judicial districts. Each U.S. attorney serves as the United States' chief federal ...

for the Western District of Kentucky

The United States District Court for the Western District of Kentucky (in case citations, W.D. Ky.) is the federal district court for the western part of the state of Kentucky.

Appeals from the Western District of Kentucky are taken to the Unite ...

, as his new running mate. Heleringer continued his legal challenge, first claiming that Bates' ineligibility should have invalidated the entire Fletcher/Bates ticket and then that Fletcher should not have been allowed to name a replacement for an unqualified candidate.Alessi and Brammer, "Fletcher Stays on the Ballot", p. A1 The Kentucky Supreme Court

The Kentucky Supreme Court is the state supreme court of the U.S. state of Kentucky. Prior to its creation by constitutional amendment in 1975, the Kentucky Court of Appeals was the only appellate court in Kentucky. The Kentucky Court of Ap ...

rejected that argument on May 7, 2003, though the justices' reasons for doing so varied and the final opinion conceded that " is is a close case

In the law, a close case is generally defined as a ruling that could conceivably be decided in more than one way. Various scholars have attempted to articulate criteria for identifying close cases, and commentators have observed that reliance upon ...

on the law, and Heleringer has presented legal issues worthy of this court's time and attention". The state Board of Elections instructed all county clerks to count absentee ballots cast for Fletcher and Bates as votes for Fletcher and Pence.

In the Republican primary, Fletcher received 53 percent of the vote, besting Nunn, Jefferson County judge/executive Rebecca Jackson, and state senator Virgil Moore. In the Democratic primary, Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general (: attorneys general) or attorney-general (AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enf ...

Ben Chandler

Albert Benjamin Chandler III (born September 12, 1959) is an American lawyer and politician who served as the United States House of Representatives, United States representative for from 2004 to 2013. A United States Democratic Party, Democrat, ...

defeated Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hung ...

Jody Richards

Walter Demaree "Jody" Richards Jr. (born February 20, 1938) is an American politician who served as a Democratic member of the Kentucky House of Representatives from 1976 until 2019. He is the longest serving Speaker of the House in the history ...

. Chandler, the grandson of former governor A. B. "Happy" Chandler, was hurt in the closing days of the campaign when a third challenger, businessman Bruce Lunsford

William Bruce Lunsford (born November 11, 1947) is an American attorney, businessman, and politician from Kentucky. He has served various roles in the Kentucky Democratic Party, including party treasurer, Deputy Development Secretary, and Head ...

dropped out of the race and endorsed Richards. Chandler won the Democratic primary by just 3.7 percentage points and was forced to reorganize his campaign. Consequently, Fletcher entered the general election

A general election is an electoral process to choose most or all members of a governing body at the same time. They are distinct from By-election, by-elections, which fill individual seats that have become vacant between general elections. Gener ...

as the favorite.

Due to the funding from the Republican Governors Association

The Republican Governors Association (RGA) is a Washington, D.C.–based 527 organization founded in 1961, consisting of U.S. state and territorial Republican governors. Its primary objective is to help elect and support Republican governors.

Th ...

, Fletcher held a two-to-one fundraising advantage over Chandler. A sex-for-favors scandal that ensnared sitting Democratic governor Paul Patton, as well as a predicted $710 million shortfall in the upcoming budget, damaged the entire Democratic slate of candidates' chances for election.Cross, p. 267 Fletcher capitalized on these issues, promising to "clean up the mess" in Frankfort, and won the election by a vote of 596,284 (55%) to 487,159 (45%). In all, Republicans captured four of the seven statewide constitutional offices in 2003; Trey Grayson

Charles Merwin "Trey" Grayson III (born April 18, 1972) is an American politician and attorney who is a member at Frost Brown Todd and a principal at CivicPoint. A former Secretary of State of Kentucky, Grayson was a candidate in the 2010 Republi ...

was elected Secretary of State and Richie Farmer

Richard Dwight Farmer Jr. (born August 25, 1969) is an American former collegiate basketball player and Republican Party politician from the U.S. state of Kentucky. He served as the Kentucky Commissioner of Agriculture from 2004 to 2012 and ...

was elected Commissioner of Agriculture. Fletcher resigned his seat in the House on December 8, 2003, and assumed the governorship the following day. Fletcher's victory made him the first Republican elected governor of Kentucky since 1971, and his margin of victory was the largest ever for a Republican in a Kentucky gubernatorial election.

Governor of Kentucky

Fletcher made economic development a priority, and Kentucky ranked fourth among all U.S. states in number of jobs created during his administration. One of his first actions as governor was to reorganize the executive branch, condensing the number of cabinet positions from fourteen to nine. He dissolved the formerKentucky Horse Racing Commission

The Kentucky Horse Racing Commission is the state agency responsible for regulating horse racing in the U.S. commonwealth of Kentucky. The agency was established in 1906, making it the oldest state racing commission in the United States.

Agency ...

and instead created the Kentucky Horse Racing Authority to promote and regulate the state's horse racing industry. To improve the state's management of Medicaid

Medicaid is a government program in the United States that provides health insurance for adults and children with limited income and resources. The program is partially funded and primarily managed by U.S. state, state governments, which also h ...

, he rolled back some of the program's requirements and unveiled a plan to focus on improvements in care, benefit management, and technology. Fletcher also launched "Get Healthy Kentucky!," an initiative to promote healthier lifestyles for Kentuckians.

2004 state budget dispute

Throughout Fletcher's term, the Kentucky Senate was controlled by Republicans, while Democrats held a majority in the state House of Representatives. Consequently, Fletcher had difficulty getting legislation enacted in the General Assembly. Early in the 2004 legislative session, he presented a plan for tax reform that he claimed was "revenue neutral" and would "modernize" the state tax code.Brammer and Alessi, "Legislators Fail to Pass a Budget", p. A1 The plan was drafted with input from seven Democratic legislators in the House, none of them in leadership roles, leading to claims that Fletcher was trying to circumvent House leadership.York and Kinney, "His First 100 Days", p. K1 As the session wore on, Republicans insisted on tying the tax reform package to the proposed state budget, while Democrats wanted to vote on the measures separately. Despite last minute attempts at a compromise as the session drew to a close, the Assembly passed neither the tax reform package nor a state budget. The contentious session ended with only a few accomplishments, including passage of a fetal homicide law, an anti-price gouging

Price gouging is the practice of increasing the prices of goods, services, or commodities to a level much higher than is considered reasonable or fair by some. This commonly applies to price increases of basic necessities after natural disaste ...

measure, and a law barring the state public service commission from regulating broadband

In telecommunications, broadband or high speed is the wide-bandwidth (signal processing), bandwidth data transmission that exploits signals at a wide spread of frequencies or several different simultaneous frequencies, and is used in fast Inter ...

Internet providers beyond what restrictions were put in place by the Federal Communications Commission

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is an independent agency of the United States government that regulates communications by radio, television, wire, internet, wi-fi, satellite, and cable across the United States. The FCC maintains j ...

.Alessi, et al., "Who Won, Who Lost in Fractious Session", p. A1

The 2004 session marked the second consecutive session in which the General Assembly had failed to pass a biennial budget; the first occurred in 2002 under Governor Patton. When the fiscal year ended without a budget in place, responsibility for state expenditures fell to Fletcher.York, "Ruling Allows Fletcher Plan to Proceed", p. K1 As it had been in 2002, spending was governed by an executive spending plan created by the governor. Democratic Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general (: attorneys general) or attorney-general (AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enf ...

Greg Stumbo

Gregory D. Stumbo (born August 14, 1951) is an American lawyer and former speaker of the Kentucky House of Representatives. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as Kentucky attorney general from 2004 to 2008. He was the Democratic candidat ...

filed suit asking for a determination on the extent of Fletcher's ability to spend without legislative approval. A similar suit, filed after the 2002 session ended in deadlock, was rendered moot when the legislature passed a budget in a special session prior to the conclusion of the lawsuit. A judicial review by a Franklin County circuit court judge approved Fletcher's spending plan but forbade spending on new capital projects and programs. In late December 2004, a judge ruled that Fletcher's plan could continue to govern spending until the end of the fiscal year on June 30, 2005, but "thereafter" executive spending was to be limited to "funds demonstrated to be for limited and specific essential services."Biesk, "Judge Sets Budget Deadline", p. K1

On May 19, 2005, the Kentucky Supreme Court

The Kentucky Supreme Court is the state supreme court of the U.S. state of Kentucky. Prior to its creation by constitutional amendment in 1975, the Kentucky Court of Appeals was the only appellate court in Kentucky. The Kentucky Court of Ap ...

issued a 4–3 decision stating that the General Assembly had acted unconstitutionally by not passing a budget and that Fletcher had acted outside his constitutional authority by spending money not specifically appropriated by the legislature. The majority opinion rejected the lower court's exception for "specific essential services", saying "If the legislative department fails to appropriate funds deemed sufficient to operate the executive department at a desired level of services, the executive department must serve the citizenry as best it can with what it is given. If the citizenry deems those services insufficient, it will exercise its own constitutional power – the ballot." Chief Justice Joseph Lambert dissented, claiming the executive spending plan was necessary. Two other justices, in a separate opinion, disagreed with the majority that federal and state constitutional mandates should still be funded in the absence of a budget. In their dissent, they argued that the threat of a government shutdown would act as an impetus for the General Assembly to engage in timely budget-making. The decision took no retroactive steps to change the actions it ruled unconstitutional, but it served as a precedent for any future cases of budgetary gridlock.York, "High Court Rules Budgetary Actions Violate Constitution", p. A12

Legislative interim and 2005 legislative session

In June 2004, Fletcher's aircraft caused a security scare that triggered a brief evacuation of the U.S. Capitol and Supreme Court building.Alessi, "Fletcher's Plane Stirs a Panic", p. A1 Shortly after takeoff en route to memorial services for former president Ronald Reagan, thetransponder

In telecommunications, a transponder is a device that, upon receiving a signal, emits a different signal in response. The term is a blend of ''transmitter'' and ''responder''.

In air navigation or radio frequency identification, a flight trans ...

on Fletcher's plane malfunctioned, leading officials at Reagan National Airport

Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport is a public airport in Arlington County, Virginia, United States, from Washington, D.C. The closest airport to the nation's capital, it is one of two airports owned by the federal government and ope ...

to report an unauthorized aircraft entering restricted airspace. Two F-15 fighters were dispatched to investigate, and Fletcher's plane was escorted to its destination by two Blackhawk helicopters

The Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk is a four-blade, twin-engine, medium-lift military utility helicopter manufactured by Sikorsky Aircraft. Sikorsky submitted a design for the United States Army's Utility Tactical Transport Aircraft System (UTTAS) ...

. The plane, a 33-year-old Beechcraft King Air

The Beechcraft King Air is a line of American utility aircraft produced by Beechcraft. The King Air line comprises a number of twin-turboprop models that have been divided into two families. The Model 90 and 100 series developed in the 1960s ...

, was the oldest of its model still in operation. An investigation by the Federal Aviation Administration

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is a Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government agency within the United States Department of Transportation, U.S. Department of Transportation that regulates civil aviation in t ...

(FAA) found that the crew of Fletcher's plane maintained radio contact with air traffic officials and received clearance to enter the restricted air space.Alessi, "Air Controller Error Blamed For D.C. Panic", p. B1 The investigation determined that miscommunication by air traffic controllers sparked the panic, and in the aftermath of the incident, the FAA adopted policies to prevent future errors of a similar nature.

In July 2004, Fletcher announced a plan to unify the state's branding to improve its public perception.Biesk, "Leno Spot to Boost Image", p. K1 Shortly after the announcement, late-night comedians

In July 2004, Fletcher announced a plan to unify the state's branding to improve its public perception.Biesk, "Leno Spot to Boost Image", p. K1 Shortly after the announcement, late-night comedians Craig Kilborn

Craig Lawrence Kilborn (born August 24, 1962) is an American television host, actor, comedian, and sports commentator. Kilborn began a career in sports broadcasting in the late 1980s, leading to an anchoring position at ESPN's '' SportsCenter'' f ...

and Jay Leno

James Douglas Muir Leno ( ; born April 28, 1950) is an American television host, comedian, and writer. After doing stand-up comedy for years, he became the host of NBC's ''The Tonight Show with Jay Leno, The Tonight Show'' from 1992 until 200 ...

made some tongue-in-cheek suggestions for the new slogan on '' The Late Late Show'' and ''The Tonight Show

''The Tonight Show'' is an American late-night talk show that has been broadcast on NBC since 1954. The program has been hosted by six comedians: Steve Allen (1954–1957), Jack Paar (1957–1962), Johnny Carson (1962–1992), Jay Leno (1992–2 ...

'', respectively. In response, Fletcher wrote a letter to both comedians taking exception to the jokes and was invited to appear on both programs. Citing Leno's larger audience and earlier time slot, Fletcher agreed to appear on ''The Tonight Show'', where he presented Leno with a Louisville Slugger

Louisville is the most populous city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, sixth-most populous city in the Southeast, and the 27th-most-populous city in the United States. By land area, it is the country's 24th-largest city; however, by populatio ...

baseball bat and traded jocular barbs about the relative advantages of Kentucky and Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

where ''The Tonight Show'' is taped."Fletcher, Leno Spar". ''The Kentucky Post'', p. K1 Eventually, four slogans were chosen to be voted on online as well as at interstate travel centers.Alessi, "State's New Brand Hits Road", p. A1 In December 2004, "Kentucky: Unbridled Spirit" was chosen as the winning slogan and was printed on road signs, state documents, and souvenirs. A 2007 study determined that 88.9% of Kentuckians could correctly identify the slogan and its logo."Kentucky Unbridled Spirit". Commonwealth of Kentucky Further, 64% of those surveyed across a ten-state region recognized the slogan and logo, higher than any other brand tested in the study.

In the second half of 2004, Fletcher proposed changes to the health benefits of state workers and retirees. Fletcher's plan provided discounts for members who engaged in healthier behavior, which he called a transition from a sickness initiative to a wellness initiative.York, "Fletcher Calls a Special Session", p. K1 Acknowledging that out-of-pocket expenses would rise, Fletcher proposed a 1% salary increase to offset the additional costs. State employees, particularly public school teachers, broadly opposed Fletcher's plan, and the Kentucky Educators Association called for an indefinite strike

Strike may refer to:

People

*Strike (surname)

* Hobart Huson, author of several drug related books

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

* Airstrike, ...

, to begin October 27, 2004. To address the opposition, Fletcher called a special session of the legislature to begin October 5, 2004. Although the state was still operating under an executive spending plan, Fletcher did not include the budget or his tax reform proposal in the session's agenda, a move praised by both parties, allowing them to focus only on concerns over the health plan. In a fifteen-day session, the General Assembly passed a plan that allocated $190 million more to health insurance for state workers and restored many of the most popular benefits in the previous insurance plan.Brammer and Alessi, "Health Plan Passes", p. A1 Immediately after the session adjourned, the Kentucky Educators Association voted to cancel their proposed strike.

On November 8, 2004, Fletcher signed a death warrant

An execution warrant (also called a death warrant or a black warrant) is a writ that authorizes the execution of a condemned person.

United States

In the United States, either a judicial or executive official designated by law issues an ...

for Thomas Clyde Bowling, who was convicted of a double murder in 1990 and sentenced to death by lethal injection

Lethal injection is the practice of injecting one or more drugs into a person (typically a barbiturate, paralytic, and potassium) for the express purpose of causing death. The main application for this procedure is capital punishment, but t ...

.Barrouquere, "Did Fletcher Risk License By Signing Death Warrant?", p. A12 A group of doctors requested an investigation by the Kentucky Board of Medical Licensure to determine whether Fletcher's medical license should be revoked for that action. Kentucky requires doctors to follow the guidelines of the American Medical Association

The American Medical Association (AMA) is an American professional association and lobbying group of physicians and medical students. This medical association was founded in 1847 and is headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. Membership was 271,660 ...

, which forbid doctors from participating in an execution. On January 13, 2005, the Board of Medical Licensure found that Fletcher was acting in his capacity as governor, not as a doctor, when he signed the warrant and ruled that his license was not subject to forfeiture by that action.Musgrave, "Medical Board Sides With Governor", p. C1

During the General Assembly's 2005 session, Fletcher again proposed his tax reform plan, and late in the session, both houses passed it.Mayse, "Legislators pass flurry of bills on session's last day", p. B5 The plan raised sin tax

A sin tax (also known as a sumptuary tax, or vice tax) is an excise tax specifically levied on certain goods deemed harmful to society and individuals, such as Alcohol tax, alcohol, tobacco tax, tobacco, drugs, candy, soft drinks, fast foods, c ...

es on cigarette

A cigarette is a narrow cylinder containing a combustible material, typically tobacco, that is rolled into Rolling paper, thin paper for smoking. The cigarette is ignited at one end, causing it to smolder; the resulting smoke is orally inhale ...

s and alcohol, as well as upping taxes on satellite television service and motel rooms.Brammer, "Tax Overhaul Passed 96–4 By House", p. A1 Businesses were also subjected to a gross receipts tax

A gross receipts tax or gross excise tax is a tax on the total gross revenues of a company, regardless of their source. A gross receipts tax is often compared to a sales tax; the difference is that a gross receipts tax is levied upon the seller o ...

. In exchange, corporate taxes were lowered, as were income taxes for individuals who earned less than $75,000 annually; 300,000 low-wage earners were dropped from the income tax rolls altogether. The Assembly also passed a budget for the remainder of the biennium, abolished the state's public campaign finance

Campaign financealso called election finance, political donations, or political financerefers to the funds raised to promote candidates, political parties, or policy initiatives and referendums. Donors and recipients include individuals, corpor ...

laws, and passed new school nutrition guidelines.

Merit system investigation

In May 2005, Attorney General Stumbo began an investigation of allegations that the Fletcher administration circumvented the statemerit system

The merit system is the process of promoting and hiring government employees based on their ability to perform a job, rather than on their political connections. It is the opposite of the spoils system.

History

The earliest known example of a ...

for hiring, promoting, demoting and firing state employees by basing decisions on employees' political loyalties.Alessi and Brammer, "Cabinet Hirings Are Under Investigation", p. A1 The investigation was prompted by a 276-page complaint filed by Douglas W. Doerting, the assistant personnel director for the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet

The Kentucky Transportation Cabinet (KYTC) is Kentucky's state-funded government agency, agency charged with building and maintaining U.S. Highway System, federal highways and List of primary state highways in Kentucky, Kentucky state highways, ...

. Fletcher, who was on a trade mission

Trade mission is a tool for governments to promote and market exports. It is smaller in scale compared to trade fairs and can be useful when firms are trying to enter a foreign market.

Considerations

Several factors are needed to be considered ...

in Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

when news of the investigation broke, conceded via telephone news conference that his office may have made "mistakes" with regard to hiring that stemmed from not having a formal process for handling employment recommendations.Brammer and Alessi, "Defiant Fletcher Blames Politics", p. A1 Upon his return from Japan, Fletcher denied that the "mistakes" by his administration were illegal and called the investigation by Stumbo "the beginning of the 2007 governor's race", an allusion to Stumbo's potential candidacy in 2007. Stumbo denied any plans to run for governor in 2007, although he eventually became gubernatorial candidate Bruce Lunsford

William Bruce Lunsford (born November 11, 1947) is an American attorney, businessman, and politician from Kentucky. He has served various roles in the Kentucky Democratic Party, including party treasurer, Deputy Development Secretary, and Head ...

's running mate in the election, losing in the Democratic primary.

A grand jury

A grand jury is a jury empowered by law to conduct legal proceedings, investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. A grand jury may subpoena physical evidence or a person to testify. A grand ju ...

was empaneled in June 2005 to investigate the charges against Fletcher's administration. By August, the jury had returned indictment

An indictment ( ) is a formal accusation that a person has committed a crime. In jurisdictions that use the concept of felonies, the most serious criminal offense is a felony; jurisdictions that do not use that concept often use that of an ind ...

s against nine administration officials, including state Republican Party chairman Darrell Brock Jr. and acting Transportation Secretary Bill Nighbert.Brammer and Alessi, "Druen Accused of 21 New Felonies", p. A1 All of the indictments were for misdemeanor

A misdemeanor (American English, spelled misdemeanour elsewhere) is any "lesser" criminal act in some common law legal systems. Misdemeanors are generally punished less severely than more serious felonies, but theoretically more so than admi ...

s such as conspiracy

A conspiracy, also known as a plot, ploy, or scheme, is a secret plan or agreement between people (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder, treason, or corruption, especially with a political motivat ...

except those against Administrative Services Commissioner Dan Druen, who was charged with 22 felonies

A felony is traditionally considered a crime of high seriousness, whereas a misdemeanor is regarded as less serious. The term "felony" originated from English common law (from the French medieval word "''félonie''") to describe an offense that ...

(20 counts of physical evidence tampering and 2 counts of witness tampering

Witness tampering is the act of attempting to improperly influence, alter or prevent the testimony of witnesses within criminal or civil proceedings.

Witness tampering and reprisals against witnesses in organized crime cases have been a difficulty ...

) in addition to 13 misdemeanors. On August 29, Fletcher granted pardons

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the j ...

to the nine indicted administration officials and issued a blanket pardon for "any and all persons who have committed, or may be accused of committing, any offense" with regard to the investigation.Chellgren, "Fletcher Signs Blanket Pardons", p. K1 Fletcher exempted himself from the blanket pardon. The next day, Fletcher was called to testify before the grand jury, but refused to answer any questions, invoking his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination.Chellgren, "Fletcher Pleads the 5th", p. K1

In mid-September, after Fletcher issued the pardons, a ''Courier-Journal

The ''Courier Journal'', also known as the ''Louisville Courier Journal'' (and informally ''The C-J'' or ''The Courier''), and called ''The Courier-Journal'' between November 8, 1868, and October 29, 2017, is a daily newspaper published in ...

'' poll found Fletcher's approval rating at 38 percent, tying the lowest rating reached by his predecessor, Paul E. Patton, during the sex scandal that tarnished his administration.Loftus, "Fletcher's approval rating sinks to 38%", p. B1 On September 14, 2005, Fletcher fired nine employees, including four of the nine he pardoned two weeks earlier.Alessi, "Fletcher Fires 9 for 'Mistakes'", p. A1 The firings were praised by Fletcher critic Charles Wells of the Kentucky Association of State Employees, who said: "When all else fails, the governor did the right thing." However, Democratic state senator and former governor Julian Carroll

Julian Morton Carroll (April 16, 1931 – December 10, 2023) was an American lawyer and politician from the state of Kentucky. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as the 54th governor of Kentucky from 1974 to 1979, succeeding Wendell F ...

criticized Fletcher for not firing the indicted officials when he issued the pardons. Fletcher also called for the firing of state Republican Party chair Darrell Brock Jr. due to Brock's role in the merit scandal. The state Republican executive committee met on September 17, but did not act on Fletcher's call to fire Brock.Biesk, "Fletcher Calls for GOP Chairman to Resign"

The grand jury continued its investigation, issuing five more indictments after Fletcher issued his blanket pardon.Alessi, "Grand Jury Can Continue to Indict", p. A1 Two were returned against members of Fletcher's staff, and two were against unpaid advisors to Fletcher. The fifth was issued against Acting Secretary Nighbert for retaliation against a whistleblower

Whistleblowing (also whistle-blowing or whistle blowing) is the activity of a person, often an employee, revealing information about activity within a private or public organization that is deemed illegal, immoral, illicit, unsafe, unethical or ...

. Only the additional charge against Nighbert was alleged to have occurred after Fletcher issued the pardon. On October 24, 2005, Fletcher filed a motion asking Franklin Circuit Court Judge William Graham to order the grand jury to stop issuing indictments for offenses that occurred prior to the blanket pardon; only the names of indicted officials could be included in the jury's final report. On November 16, Graham ruled that the grand jury could continue issuing indictments, but in a separate ruling, dismissed the indictments against Fletcher's staff and volunteer advisors on grounds that they were covered by the pardon. Graham did not rule on the latest indictment against Nighbert. The Kentucky Court of Appeals

The Kentucky Court of Appeals is the lower of Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illino ...

affirmed Graham's ruling on December 16.Alessi, "Pardons Do Not Preclude Inquiry", p. A1 Immediately after the Court of Appeals' ruling, Fletcher announced his intent to appeal the ruling to the Kentucky Supreme Court

The Kentucky Supreme Court is the state supreme court of the U.S. state of Kentucky. Prior to its creation by constitutional amendment in 1975, the Kentucky Court of Appeals was the only appellate court in Kentucky. The Kentucky Court of Ap ...

.

2006 legislative session

On February 12, 2006, shortly after the beginning of the General Assembly's legislative session, Fletcher was hospitalized with abdominal pain.Warren, "Fletcher Leaves Hospital for Home", p. A1 Doctors at St. Joseph East hospital in Lexington found agallstone

A gallstone is a stone formed within the gallbladder from precipitated bile components. The term cholelithiasis may refer to the presence of gallstones or to any disease caused by gallstones, and choledocholithiasis refers to the presence of ...

in his common bile duct

The common bile duct (also bile duct) is a part of the biliary tract. It is formed by the union of the common hepatic duct and cystic duct. It ends by uniting with the pancreatic duct to form the ampulla of Vater (hepatopancreatic ampulla). ...

and also diagnosed him with an inflamed pancreas

The pancreas (plural pancreases, or pancreata) is an Organ (anatomy), organ of the Digestion, digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. In humans, it is located in the abdominal cavity, abdomen behind the stomach and functions as a ...

and gallbladder disease. After surgery to remove the gallbladder, Fletcher developed a blood infection that slowed his recovery, but was discharged from the hospital on March 1. Days later, he returned to St. Joseph's with a blood clot which had to be dissolved, resulting in another five-day stay in the hospital.Warren, "Fletcher Leaves Hospital", p. C1 Fletcher staffers insisted that his absence did not have a negative impact on his ability to get legislation passed during the session.Steitzer, "Fletcher Illness Has Little Impact on Political Work", p. A1 A right-to-work law

In the context of labor law in the United States, the term right-to-work laws refers to state laws that prohibit union security agreements between employers and labor unions. Such agreements can be incorporated into union contracts to requir ...

and a repeal of the state's prevailing wage

In United States government contracting, a prevailing wage is defined as the hourly wage, usual benefits and overtime, paid to the majority of workers, laborers, and mechanics within a particular area. This is usually the union wage.

Prevailing ...

law – both advocated by Fletcher – failed early in the session, but both had been considered unlikely to pass before the session started. Among the bills that did pass the session were a mandatory seat belt law

A seat is a place to sit. The term may encompass additional features, such as back, armrest, head restraint but may also refer to concentrations of power in a wider sense (i.e "seat (legal entity)"). See disambiguation.

Types of seat

The foll ...

, a law requiring children under 16 years old to wear a helmet when operating an all-terrain vehicle

An all-terrain vehicle (ATV), also known as a light utility vehicle (LUV), a quad bike or quad (if it has four wheels), as defined by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI), is a vehicle that travels on low-pressure tires, has a seat ...

, and legislation allowing the Ten Commandments

The Ten Commandments (), or the Decalogue (from Latin , from Ancient Greek , ), are religious and ethical directives, structured as a covenant document, that, according to the Hebrew Bible, were given by YHWH to Moses. The text of the Ten ...

to be posted on Capitol grounds in a historical context.Brammer and Alessi, "Several Bills Dead on Arrival This Year", p. B1

The Assembly passed a biennial budget, but did not allow enough time in the session to reconvene and potentially override any of Fletcher's veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president (government title), president or monarch vetoes a bill (law), bill to stop it from becoming statutory law, law. In many countries, veto powe ...

es.Alessi, et al., "Money For Baptist College Stays In", p. A1 In an attempt to avoid "excessive debt", Fletcher used his line-item veto

The line-item veto, also called the partial veto, is a special form of veto power that authorizes a chief executive to reject particular provisions of a bill enacted by a legislature without vetoing the entire bill. Many countries have differen ...

to trim $370 million in projects from the budget passed by the Assembly. Although falling far short of his initial prediction of vetoing $938 million, Fletcher used the line-item veto more than any other governor in state history. One project not vetoed by Fletcher was $11 million for the University of the Cumberlands

The University of the Cumberlands is a private Christian university in Williamsburg, Kentucky, United States. Over 20,000 students are enrolled at the university.

History

University of the Cumberlands, first called Williamsburg Institute, was f ...

to build a pharmacy school

The basic requirement for pharmacists to be considered for registration is often an undergraduate or postgraduate pharmacy degree from a recognized university. In many countries, this involves a four- or five-year course to attain a bachelor of ...

. LGBT

LGBTQ people are individuals who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or questioning. Many variants of the initialism are used; LGBTQIA+ people incorporates intersex, asexual, aromantic, agender, and other individuals. The gro ...

rights groups had asked Fletcher to veto the funds because the university, a private Baptist school, had expelled a student for being openly gay.Beisk, "$11M For College Triggers Lawsuit", p. A1

One of Fletcher's priorities that was not resolved during the session was the correction of unintended tax increases on businesses that resulted from the tax reform plan passed in 2005. Fletcher called a special legislative session for mid-June so that the legislature could amend the plan and also authorize tax breaks designed to lure a proposed FutureGen