Ernest Parke on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ernest Parke (26 February 1860–21 June 1944) was a political writer, editor, newspaper proprietor and local politician. In 1890, as the editor of ''The North London Press'', he was imprisoned for

Ernest Parke (26 February 1860–21 June 1944) was a political writer, editor, newspaper proprietor and local politician. In 1890, as the editor of ''The North London Press'', he was imprisoned for

British Newspaper Archive, 1 August 2023

In 1889 Parke was involved in the notorious

In 1889 Parke was involved in the notorious

Euston had not fled to Peru but was actually still in England when the article was brought to his attention and at once he filed a case against Parke for

Euston had not fled to Peru but was actually still in England when the article was brought to his attention and at once he filed a case against Parke for

ERNEST PARKE: AN ATTEMPT AND FAIL TO BRING DOWN THE VICTORIAN ARISTOCRACY

History thesis, 2016 At the subsequent trial before judge Sir Henry Hawkins, for which Parke was remanded in custody despite having offered four sureties of £500 each, In court Euston admitted that as he had been passing along

Following representations by other journalists on his behalf to the

Following representations by other journalists on his behalf to the

Ernest Parke (26 February 1860–21 June 1944) was a political writer, editor, newspaper proprietor and local politician. In 1890, as the editor of ''The North London Press'', he was imprisoned for

Ernest Parke (26 February 1860–21 June 1944) was a political writer, editor, newspaper proprietor and local politician. In 1890, as the editor of ''The North London Press'', he was imprisoned for libel

Defamation is a communication that injures a third party's reputation and causes a legally redressable injury. The precise legal definition of defamation varies from country to country. It is not necessarily restricted to making assertions ...

for his reporting of the Cleveland Street scandal

The Cleveland Street scandal occurred in 1889, when a homosexual male brothel and Love hotel, house of assignation on Cleveland Street, London, was discovered by police. The government was accused of covering up the scandal to protect the names ...

.Unlock the Story of the Cleveland Street ScandalBritish Newspaper Archive, 1 August 2023

Early life and career

He was born inStratford-upon-Avon

Stratford-upon-Avon ( ), commonly known as Stratford, is a market town and civil parish in the Stratford-on-Avon (district), Stratford-on-Avon district, in the county of Warwickshire, in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands region of Engl ...

in 1860, the youngest of four sons of Anne ''née'' Hall (1824–1902) and Fenning Plowman Parke (1826–1902), an Excise Officer. Morris, A. J. A.br>Ernest Parke (1860-1944)Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from History of the British Isles, British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') ...

(ODNB), Published in print: 23 September 2004. Published online: 23 September 2004. This version: 04 October 2008 On leaving King Edward VI School he worked in a bank in Stratford-upon-Avon until 1882. Having started to contribute pieces on local topics to the local newspapers, he took up a position as a journalist on the ''Birmingham Gazette

The ''Birmingham Gazette'', known for much of its existence as ''Aris's Birmingham Gazette'', was a newspaper that was published and circulated in Birmingham, England, from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries. Founded as a weekly publicatio ...

'', followed soon after by ''The Midland Echo'' in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the Lis ...

, later becoming an assistant sub-editor on that paper. He was editor of the financial newspaper ''Stock Exchange'' on Fleet Street

Fleet Street is a street in Central London, England. It runs west to east from Temple Bar, London, Temple Bar at the boundary of the City of London, Cities of London and City of Westminster, Westminster to Ludgate Circus at the site of the Lo ...

, but not liking the work in 1884 he joined the staff of the Fleet Street evening paper '' The Echo''. In the same year he married Sarah Elizabeth Blain (1863-1937). Herself a journalist, she after wrote under the pen name 'Mrs. Ernest Parke'. On the marriage certificate his occupation was recorded as 'Journalist'. Their sons were: Fenning Matthew Parke (1885-1928) and Hall Parke (1905-1985).

In 1888, on the recommendation of John Richard Robinson, editor manager of '' The Daily News'', he accepted from T. P. O'Connor

Thomas Power O'Connor, PC (5 October 1848 – 18 November 1929), known as T. P. O'Connor and occasionally as Tay Pay (mimicking the Irish pronunciation of the initials ''T. P.''), was an Irish nationalist politician and journalist who served ...

the position of sub-editor of the newly formed '' The Star''.JOURNALS AND JOURNALISTS OF TO-DAY: ERNEST PARKE AND THE "STAR" AND "MORNING LEADER", ''The Sketch'', 25 April 1894, p. 685 He soon impressed O'Connor with his 'keenness, tremendous flair for news, and the capacity to work twenty four hours a day if necessary'. Later in 1888 he was appointed deputy editor of ''The Star''. In the 31 August 1888 edition he suggested that Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer who was active in and around the impoverished Whitechapel district of London, England, in 1888. In both criminal case files and the contemporaneous journalistic accounts, the killer was also ...

, who had just murdered Mary Ann Nichols

Mary Ann Nichols, known as Polly Nichols (née Walker; 26 August 184531 August 1888), was the first Jack the Ripper#Canonical five, canonical victim of the unidentified serial killer known as Jack the Ripper, who is believed to have murdered an ...

, was a single killer. He was editor from 1891 to 1918. At the same time edited ''The Morning Leader

''The Morning Leader'' was a Sri Lankan English-language newspaper. It is published by Leader Publications (Pvt) Ltd. Its sister publications are The Sunday Leader and Iruresa

''Iruresa'' is a Sinhala language Sri Lankan weekly newspaper publis ...

'', running both newspapers at the same time and working 'harder than any editor had done before or has done since'.

Parke was one of the first editors to use stop press news, when he had racing results printed with a rubber stamp. He gained a reputation for supporting 'anti' movements: anti-vaccination

Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine to help the immune system develop immunity from a disease. Vaccines contain a microorganism or virus in a weakened, live or killed state, or proteins or toxins from the organism. In stimulating ...

, anti-vivisection

Vivisection () is surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure. The word is, more broadly, used as a pejorative catch-all term for Animal test ...

, anti-protection, and anti the South African War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

. This last gained him the greatest radical recognition of having his newspaper burned on the London Stock Exchange

The London Stock Exchange (LSE) is a stock exchange based in London, England. the total market value of all companies trading on the LSE stood at US$3.42 trillion. Its current premises are situated in Paternoster Square close to St Paul's Cath ...

. Despite his radical views, Parke was a foremost trusted adviser to the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

in its dealings with the press.

Cleveland Street scandal

In 1889 Parke was involved in the notorious

In 1889 Parke was involved in the notorious Cleveland Street scandal

The Cleveland Street scandal occurred in 1889, when a homosexual male brothel and Love hotel, house of assignation on Cleveland Street, London, was discovered by police. The government was accused of covering up the scandal to protect the names ...

when a homosexual male brothel

A brothel, strumpet house, bordello, bawdy house, ranch, house of ill repute, house of ill fame, or whorehouse is a place where people engage in Human sexual activity, sexual activity with prostitutes. For legal or cultural reasons, establis ...

and house of assignation on Cleveland Street, London

Cleveland Street in central London runs north to south from Euston Road (A501 road, A501) to the junction of Mortimer Street and Goodge Street. It lies within Fitzrovia, in the W postcode area, W1 post code area. Cleveland Street also runs al ...

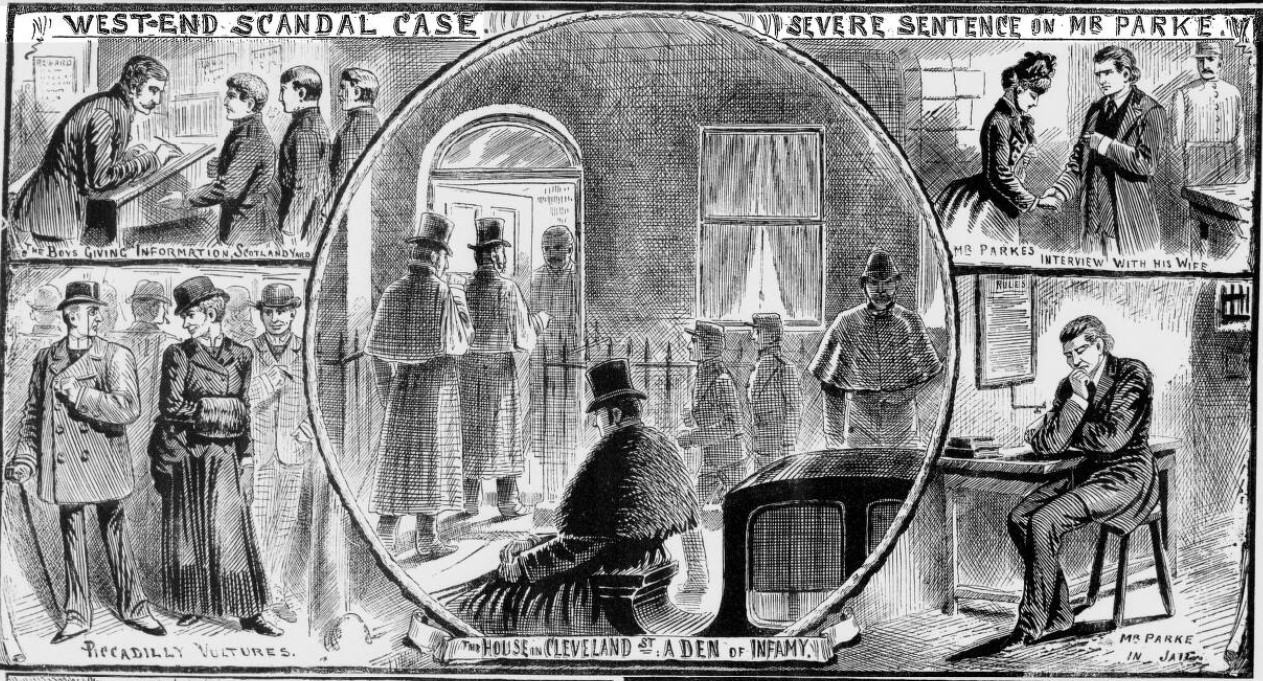

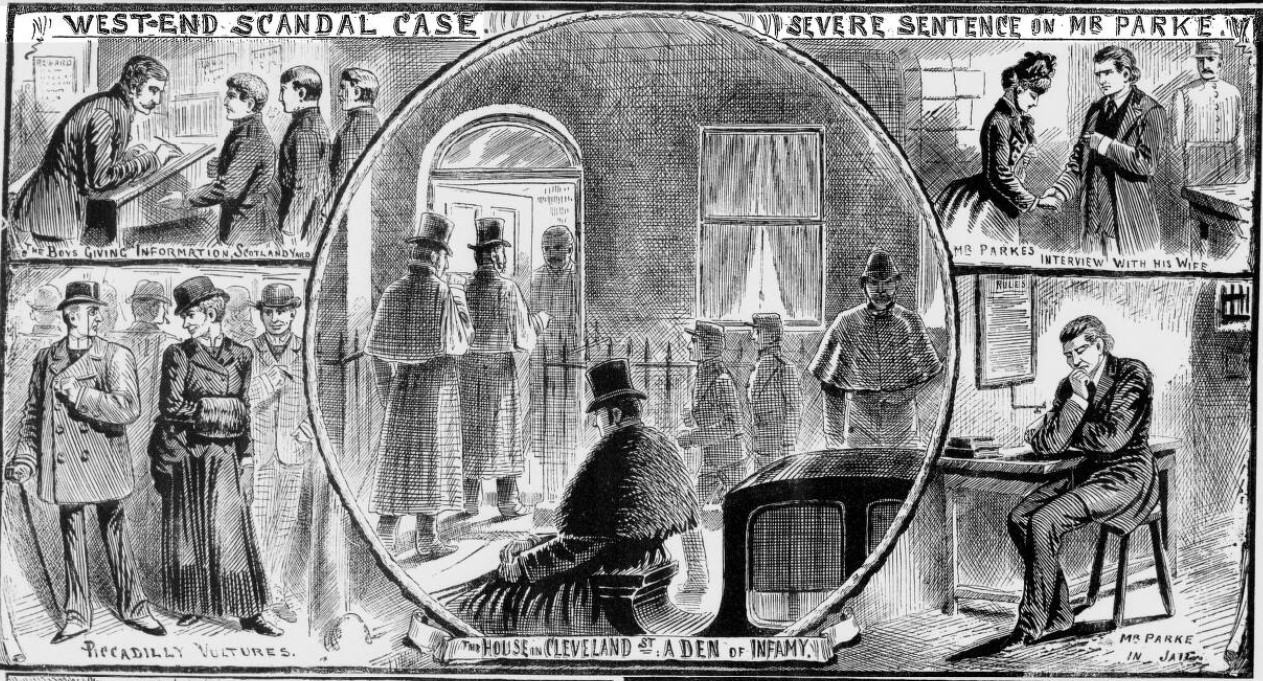

, was uncovered by the police. At first the newspapers showed little interest in the story, which would have been quickly forgotten if not for Parke. As editor of the politically radical weekly ''The North London Press'', Parke was first informed of police involvement in Cleveland Street when a reporter informed him of the conviction of the 18 year-old Post Office clerk and male prostitute, Henry Newlove. Parke began to ask why the male prostitutes involved had received light sentences with regard to their offence. His journalistic curiosity aroused, Parke discovered that the young male prostitutes had named leading members of the aristocracy as their patrons. Parke ran the story on 28 September 1889 hinting at their involvement but refrained from naming names. On 16 November 1889 he published a further piece which named Henry James FitzRoy, Earl of Euston

Henry James FitzRoy, Earl of Euston (28 November 1848 – 10 May 1912) was the eldest son and heir apparent of Augustus FitzRoy, 7th Duke of Grafton. His mother was the daughter of MP James Balfour.

Personal life

Euston married a music hall a ...

, in "an indescribably loathsome scandal in Cleveland Street". Parke also alleged that Euston may have fled to Peru to avoid prosecution and that he had been permitted to escape by the authorities to conceal the involvement of a more highly placed personage; although this person was not named some believe that it was Prince Albert Victor

Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale (Albert Victor Christian Edward; 8 January 1864 – 14 January 1892) was the eldest child of the Prince and Princess of Wales (later King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra). From the time of his ...

, son of the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales (, ; ) is a title traditionally given to the male heir apparent to the History of the English monarchy, English, and later, the British throne. The title originated with the Welsh rulers of Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd who, from ...

and grandson of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

.

Trial for libel

Euston had not fled to Peru but was actually still in England when the article was brought to his attention and at once he filed a case against Parke for

Euston had not fled to Peru but was actually still in England when the article was brought to his attention and at once he filed a case against Parke for libel

Defamation is a communication that injures a third party's reputation and causes a legally redressable injury. The precise legal definition of defamation varies from country to country. It is not necessarily restricted to making assertions ...

. Magistrate Sir James Vaughan issued a warrant for Parke's arrest on November 23, 1889 after Bow Street Magistrates' Court

Bow Street Magistrates' Court (formerly Bow Street Magistrates' court (England and Wales), Police Court) and Police Station each became one of the most famous magistrates' court (England and Wales), magistrates' courts and police stations in Eng ...

successfully proved the report against Euston to be libellous. Parke promptly turned himself into police custody. He had known for a week that he was likely be arrested and argued in his defence that he intentionally stayed in the country to accept the possibility of being charged with libel. Parke spent the entire weekend in jail and awaited trial for Monday morning. He meanwhile formed his defense team, consisting of Frank Lockwood, QC, and H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928) was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. He was the last ...

, who would later become Prime Minister during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. The hearing at Bow Street Magistrates' Court began on the morning of 25 November 1889. Vaughan set the bail at two securities of £50 each, which Parke posted.

Parke was widely regarded by his fellow journalists as the hero of the hour, victimised for telling the truth. With his 'pale, earnest, and intellectual face', ''The Illustrated Police News

''The Illustrated Police News'' was a weekly illustrated newspaper which was one of the earliest British tabloids. It featured sensational and melodramatic reports and illustrations of murders and hangings and was a direct descendant of the ex ...

'' described him as looking 'more like a hard-working student than the defendant in a newspaper libel case', whilst also noting his popularity with the 'newspaper men, among whom he seems to enjoy warm popularity and substantial esteem'. At the preliminary hearing at the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

Parke pleaded not guilty to the charge of libel. Asquith argued that 'the alleged libel was true in substance and in fact, and that its publication was for the public benefit'. Lionel Hart, for the prosecution, did not counter, but 'applied for the postponement of the trial', because Parke's plea had only just been submitted. The judge in the case agreed, despite Parke being 'ready and anxious to meet the charge', and the case was set to 'stand over until the next sessions'. Parke was released on bail.Coon, JeffreERNEST PARKE: AN ATTEMPT AND FAIL TO BRING DOWN THE VICTORIAN ARISTOCRACY

History thesis, 2016 At the subsequent trial before judge Sir Henry Hawkins, for which Parke was remanded in custody despite having offered four sureties of £500 each, In court Euston admitted that as he had been passing along

Piccadilly

Piccadilly () is a road in the City of Westminster, London, England, to the south of Mayfair, between Hyde Park Corner in the west and Piccadilly Circus in the east. It is part of the A4 road (England), A4 road that connects central London to ...

a ticket tout

Ticket or tickets may refer to:

Slips of paper

* Lottery, Lottery ticket

* Parking violation, Parking ticket, a ticket confirming that the parking fee was paid (and the time of the parking start)

* Ticket system, Toll ticket, a slip of paper use ...

had passed him a card on which was written "''Poses plastiques''. C. Hammond, 19 Cleveland Street". Euston stated that he went to that address in the belief that ''Poses plastiques'' was actually a tableau of nude female. He paid an admission charge of a sovereign

''Sovereign'' is a title that can be applied to the highest leader in various categories. The word is borrowed from Old French , which is ultimately derived from the Latin">-4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to ...

but upon entering he said he was appalled to discover the "improper" nature of the place and promptly left. The witnesses for the defence contradicted one another, and they could not accurately describe Euston. The last witness for the defence was John Saul

John Saul (born February 25, 1942) is an American author of suspense and horror novels. Most of his books have appeared on the ''New York Times'' Best Seller list. .

Biography

Born in Pasadena, Saul grew up in Whittier, California, and grad ...

, a male prostitute

Male prostitution is a form of sex work consisting of the act or practice of men providing sexual services in return for payment. Although clients can be of any gender, the vast majority are older males looking to fulfill their sexual needs. M ...

who previously had been involved in another homosexual scandal, this time at Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle () is a major Government of Ireland, Irish government complex, conference centre, and tourist attraction. It is located off Dame Street in central Dublin.

It is a former motte-and-bailey castle and was chosen for its position at ...

. He also featured in a clandestinely published erotic novel ''The Sins of the Cities of the Plain

''The Sins of the Cities of the Plain; or, The Recollections of a Mary-Ann, with Short Essays on Sodomy and Tribadism'', by the pseudonymous " Jack Saul", is one of the first exclusively homosexual works of pornographic literature published in E ...

'', which claimed to be his autobiography

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life, providing a personal narrative that reflects on the author's experiences, memories, and insights. This genre allows individuals to share thei ...

. Delivering his testimony in a manner described as "brazen effrontery", Saul admitted to earning his living by leading an "immoral life" and "practising criminality", and detailed his alleged sexual encounters with Euston at the house. On 16 January 1890, the jury found Parke guilty of 'Maliciously publishing a false and defamatory libel'Ernest Parke in UK, Calendar of Prisoners, 1868-1929 (1890) and the judge sentenced him to twelve months without hard labour in Millbank Prison

Millbank Prison or Millbank Penitentiary was a prison in Millbank, Westminster, London, originally constructed as the National Penitentiary, and which for part of its history served as a holding facility for convicted prisoners before they were p ...

.

Later years

Following representations by other journalists on his behalf to the

Following representations by other journalists on his behalf to the Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, more commonly known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom and the head of the Home Office. The position is a Great Office of State, maki ...

Henry Matthews Parke was released from prison on 7 July 1890, having served half his sentence. He returned to '' The Star''; he was editor from 1891 to 1918, when he resigned. Having retired from his editorial roles Parke increased his numerous business commitments. He sat on the boards of national and local newspaper companies, including '' The Daily News'' and '' The Star'', the Northern Newspaper Company, and the Sheffield Independent Press. In 1904 he was a founding member of the Newspaper Proprietors' Association.

Parke was a Justice of the Peace (JP), an Alderman and for six years Vice-Chairman of Warwickshire County Council

Warwickshire County Council is the county council that governs the non-metropolitan county of Warwickshire in England. Its headquarters are at Shire Hall in the centre of Warwick, the county town. The council's principal functions are county ro ...

, which he first joined as a County Councillor in 1917. He successfully worked his farm Moorlands at Kineton

Kineton is a village and civil parishes in England, civil parish on the River Dene in south-east Warwickshire, England. The village is part of Stratford-on-Avon (district), Stratford-on-Avon district, and in the United Kingdom Census 2001, 20 ...

in Warwickshire

Warwickshire (; abbreviated Warks) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England. It is bordered by Staffordshire and Leicestershire to the north, Northamptonshire to the east, Ox ...

, which led to his becoming a member of the agricultural small holdings and the land cultivation committees of Warwickshire County Council.

Until his 83rd year he was physically robust and mentally alert, but during his last year his health began to fail and he gradually faded from the public life of Warwickshire.Obituary: Alderman Ernest Parke, Birmingham Daily Post

The ''Birmingham Post'' is a weekly printed newspaper based in Birmingham, England, with distribution throughout the West Midlands. First published under the name the ''Birmingham Daily Post'' in 1857, it has had a succession of distinguished ...

, 23 June 1944, p. 4 He died on 21 June 1944 at Warneford Hospital

The Warneford Hospital is a hospital providing mental health services at Headington in east Oxford, England. It is managed by the Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust.

History

The hospital opened as the Oxford Lunatic Asylum in July 1826. It was ...

in Leamington Spa

Royal Leamington Spa, commonly known as Leamington Spa or simply LeamingtonEven more colloquially, also referred to as Lem or Leam (). (), is a spa town and civil parish in Warwickshire, England. Originally a small village called Leamington Pri ...

as the result of a fall at his home. He was cremated and his ashes were buried in the grave of his wife at the parish church of St Peter and St Paul in Butlers Marston. He left an estate valued at £34625 8s. 1d.Ernest Parke in England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills (1944)

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Parke, Ernest 1860 births 1944 deaths People from Stratford-upon-Avon People educated at King Edward VI School, Stratford-upon-Avon English male journalists English newspaper editors 19th-century English journalists 20th-century English journalists Members of Warwickshire County Council