Ellesmere Island on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ellesmere Island (; ) is Canada's northernmost and third largest island, and the tenth largest in the world. It comprises an area of , slightly smaller than

Ellesmere Island is the northernmost island of the

Ellesmere Island is the northernmost island of the

The Arctic willow is the only woody species to grow on Ellesmere Island.

In July 2007, a study noted the disappearance of habitat for

The Arctic willow is the only woody species to grow on Ellesmere Island.

In July 2007, a study noted the disappearance of habitat for

Large portions of Ellesmere Island are covered with glaciers and ice, with Manson Icefield () and Sydkap () in the south; Prince of Wales Icefield () and Agassiz Ice Cap () along the central-east side of the island, and the Northern Ellesmere icefields ().

The northwest coast of Ellesmere Island was covered by a massive, long ice shelf until the 20th century. The Ellesmere Ice Shelf shrank by 90 per cent in the 20th century due to warming trends in the Arctic, particularly in the 1930s and 1940s, a period when the largest ice islands (the T1 and the T2 ice islands) were formed leaving the separate Alfred Ernest, Ayles, Milne, Ward Hunt, and Markham Ice Shelves. The Ward Hunt Ice Shelf, the largest remaining section of thick (>10 m, >30 ft) landfast sea ice along the northern coastline of Ellesmere Island, lost almost of ice in a massive calving in 1961–1962. Five large ice islands which resulted account for 79% of the calved material. It further decreased by 27% in thickness () between 1967 and 1999. A 1986 survey of Canadian ice shelves found that or of ice calved from the Milne and Ayles ice shelves between 1959 and 1974.

The breakup of the Ellesmere Ice Shelves has continued in the 21st century: the Ward Ice Shelf experienced a major breakup during the summer of 2002; the Ayles Ice Shelf calved entirely on 13 August 2005; the largest breakoff of the ice shelf in 25 years, it may pose a threat to the oil industry in the

Large portions of Ellesmere Island are covered with glaciers and ice, with Manson Icefield () and Sydkap () in the south; Prince of Wales Icefield () and Agassiz Ice Cap () along the central-east side of the island, and the Northern Ellesmere icefields ().

The northwest coast of Ellesmere Island was covered by a massive, long ice shelf until the 20th century. The Ellesmere Ice Shelf shrank by 90 per cent in the 20th century due to warming trends in the Arctic, particularly in the 1930s and 1940s, a period when the largest ice islands (the T1 and the T2 ice islands) were formed leaving the separate Alfred Ernest, Ayles, Milne, Ward Hunt, and Markham Ice Shelves. The Ward Hunt Ice Shelf, the largest remaining section of thick (>10 m, >30 ft) landfast sea ice along the northern coastline of Ellesmere Island, lost almost of ice in a massive calving in 1961–1962. Five large ice islands which resulted account for 79% of the calved material. It further decreased by 27% in thickness () between 1967 and 1999. A 1986 survey of Canadian ice shelves found that or of ice calved from the Milne and Ayles ice shelves between 1959 and 1974.

The breakup of the Ellesmere Ice Shelves has continued in the 21st century: the Ward Ice Shelf experienced a major breakup during the summer of 2002; the Ayles Ice Shelf calved entirely on 13 August 2005; the largest breakoff of the ice shelf in 25 years, it may pose a threat to the oil industry in the

Schei and later Alfred Gabriel Nathorst described the

Schei and later Alfred Gabriel Nathorst described the

All groups occupying the island settled on the coast, particularly those relying on maritime resources, while modern-era government-funded settlements were initially supplied by sea.

In 2021, the population of Ellesmere Island was recorded as 144. There are three settlements on Ellesmere Island: Alert (permanent pop. 0, but home to a small temporary population), Eureka (permanent pop. 0), and Grise Fiord (pop. 144). Politically, it is part of the

All groups occupying the island settled on the coast, particularly those relying on maritime resources, while modern-era government-funded settlements were initially supplied by sea.

In 2021, the population of Ellesmere Island was recorded as 144. There are three settlements on Ellesmere Island: Alert (permanent pop. 0, but home to a small temporary population), Eureka (permanent pop. 0), and Grise Fiord (pop. 144). Politically, it is part of the

Grise Fiord (

Grise Fiord (

Ellesmere Island in the Atlas of Canada - Toporama; Natural Resources Canada

Mountains on Ellesmere Island

Detailed map, northern Ellesmere Island, including named capes, points, bays, and offshore islands

by Geoffrey Hattersley-Smith

Norman E. Brice Report on Ellesmere Island

at Dartmouth College Library {{Authority control Islands of Baffin Bay Islands of the Queen Elizabeth Islands Inhabited islands of Qikiqtaaluk Region

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

, and the total length of the island is .

Lying within the Arctic Archipelago

The Arctic Archipelago, also known as the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, is an archipelago lying to the north of the Canadian continental mainland, excluding Greenland (an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, which is, by itself, much larger ...

, Ellesmere Island is considered part of the Queen Elizabeth Islands

The Queen Elizabeth Islands () are the northernmost cluster of islands in Canada's Arctic Archipelago, split between Nunavut and the Northwest Territories in Northern Canada. The Queen Elizabeth Islands contain approximately 14% of the global gl ...

. Cape Columbia

Cape Columbia is the northernmost point of land of Canada, located on Ellesmere Island in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut. It marks the westernmost coastal point of Lincoln Sea in the Arctic Ocean. It is the world's northernmost point of l ...

at is the most northerly point of land in Canada and one of the most northern points of land on the planet (the most northerly point of land on Earth is the nearby Kaffeklubben Island of Greenland).

The Arctic Cordillera mountain system covers much of Ellesmere Island, making it the most mountainous in the Arctic Archipelago. More than one-fifth of the island is protected as Quttinirpaaq National Park

Quttinirpaaq National Park is located on the northeastern corner of Ellesmere Island in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada. It is the second most northerly park on Earth after Northeast Greenland National Park. In Inuktitut, Quttinirpaaq m ...

.

In 2021, the population of Ellesmere Island was recorded at 144. There are three settlements: Alert, Eureka, and Grise Fiord. Ellesmere Island is administered as part of the Qikiqtaaluk Region

The Qikiqtaaluk Region, Qikiqtani Region (Inuktitut syllabics: ᕿᑭᖅᑖᓗᒃ ) or the Baffin Region is the easternmost, northernmost, and southernmost administrative region of Nunavut, Canada. Qikiqtaaluk is the traditional Inuktitut nam ...

in the Canadian territory of Nunavut

Nunavut is the largest and northernmost Provinces and territories of Canada#Territories, territory of Canada. It was separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999, via the ''Nunavut Act'' and the Nunavut Land Claims Agr ...

.

Geology

Ellesmere Island has three major geological regions. The Grant Land Highlands is a large belt of fold mountains which dominate the northern face of the island. It is part of the Franklinian mobile belt, a zone of Cretaceous volcanic and intrusive rock. South of this is the Greely-Hazen Plateau, a large tableland composed of sedimentary and volcanic rocks. Covering most of the island, the coastal sedimentary plateau is a succession of highly eroded sedimentary peaks which are part of the Franklinian Shield with an extension of theCanadian Shield

The Canadian Shield ( ), also called the Laurentian Shield or the Laurentian Plateau, is a geologic shield, a large area of exposed Precambrian igneous and high-grade metamorphic rocks. It forms the North American Craton (or Laurentia), th ...

(Precambrian igneous and metamorphic rocks) in the island's southeastern corner. In addition, there are syntectonic clastics which comprise the Ellesmere Island Volcanics of the Sverdrup Basin Magmatic Province.

A period of uplift and faulting prior to the Pleistocene epoch (>2.6 Ma) established the overall features of the island. Additional uplift occurred due to isostatic rebound

Post-glacial rebound (also called isostatic rebound or crustal rebound) is the rise of land masses after the removal of the huge weight of ice sheets during the last glacial period, which had caused isostatic depression. Post-glacial rebound ...

following the last glacial period. Land features were then shaped by erosion from glacial ice, meltwaters, and scouring by sea ice.

History

It is believed that each of the pre-contact peoples who migrated through the High Arctic approached Ellesmere Island from the south and west. They were able to travel along Ellesmere's coasts or overland to Nares Strait, and some of them crossed the strait to populate Greenland. The archaeological record of past Arctic cultures is quite complete, as artefacts deteriorate very slowly. Items exposed to the cold, dry winds become naturally freeze-dried while items that become buried are preserved in the permafrost. Artefacts are in a similar condition to when they were left or lost, and settlements abandoned thousands of years ago can be seen much as they were the day their inhabitants left. From these sites and artefacts, archaeologists have been able to construct a history of these cultures. However, the research is incomplete and only a small proportion of the details of excavations have been published.Small tool cultures

The Arctic small tool tradition peoples ( Paleo-Eskimos) in the High Arctic had small populations organized as hunting bands, spread from Axel Heiberg Island to the northern extremity of Greenland, where theIndependence I culture

Independence I was a culture of Paleo-Eskimos who lived in northern Greenland and the Canadian Arctic between 2400 and 1900 BC. There has been much debate among scholars on when Independence I culture disappeared, and, therefore, there is a margi ...

was active from 2700 BCE. On Ellesmere, they chiefly hunted in the Eureka Upland and the Hazen Plateau. Six different small-tool cultures have been identified at the Smith Sound

Smith Sound (; ) is an Arctic sea passage between Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are ...

region: Independence I, Independence I / Saqqaq, Pre-Dorset

The Pre-Dorset is a loosely defined term for a Paleo-Eskimo culture or group of cultures that existed in the Eastern Canadian Arctic from c. 3200 to 850 cal BC, and preceded the Dorset culture.

Due to its vast geographical expanse and to histor ...

, Saqqaq, early Dorset, and late Dorset. They chiefly hunted muskoxen: more than three-quarters of their known archeological sites on Ellesmere are located in the island's interior and their winter dwellings were skin tents, suggesting a need for mobility to follow the herds. There is evidence at Lake Hazen of a trade network , including soapstone lamps from Greenland and incised lance heads from cultures to the south.

Thule culture

The Thule moved into the High Arctic at the time of a warming trend, c. 1000 CE. Their major population centre was the Smith Sound area (on both the Ellesmere and Greenland sides) due to its proximity to polynyas and its position on transportation routes. From settlements at Smith Sound, the Thule sent summer hunting parties to harvestmarine mammal

Marine mammals are mammals that rely on marine ecosystems for their existence. They include animals such as cetaceans, pinnipeds, sirenians, sea otters and polar bears. They are an informal group, unified only by their reliance on marine enviro ...

s in Nansen Strait. Their summer camps are evidenced by tent rings as far north as Archer Fiord, with clusters of stone dwellings around Lady Franklin Bay and at Lake Hazen which suggest semi-permanent occupations.

The Thule genetically and culturally completely replaced the Dorset people

The Dorset was a Paleo-Eskimo culture, lasting from to between and , that followed the Pre-Dorset and preceded the Thule people (proto-Inuit) in the North American Arctic. The culture and people are named after Cape Dorset (now Kinngait) ...

some time after 1300 CE. The Thule displaced the small-tool cultures, having a number of technological advantages which notably included effective weapons, kayaks and umiaks for hunting marine mammals, and sled dog

A sled dog is a dog trained and used to pull a land vehicle in Dog harness, harness, most commonly a Dog sled, sled over snow.

Sled dogs have been used in the Arctic for at least 8,000 years and, along with watercraft, were the only transpor ...

s for surface transport and pursuit. The Thule also had an extensive trade network, evidenced by meteoritic iron from Greenland which was exported through Ellesmere Island to the rest of the archipelago and to the North American mainland.

More than fifty Norse artefacts have been found in Thule archeological sites on the Bache Peninsula, including pieces of chain mail. It is uncertain if Ellesmere Island was directly visited by Norse Greenlanders who sailed from the south or if the items were traded through a network of middlemen. It is also possible the items may have been taken from a shipwreck. A bronze set of scales discovered in western Ellesmere Island has been interpreted as indicating the presence of a Norse trader in the region. The Norse artefacts date from c. 1250 to 1400 CE.

Between 1400 and 1600 CE, the Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of regional cooling, particularly pronounced in the North Atlantic region. It was not a true ice age of global extent. The term was introduced into scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939. Mat ...

developed and conditions for hunting became increasingly difficult, forcing the Thule to withdraw from Ellesmere and the other northern islands of the archipelago. The Thule who remained in northern Greenland became isolated, specialized at hunting a diminishing number of game animals, and lost the ability to make boats. Thus, the waters around Ellesmere were not navigated again until the arrival of large European vessels after 1800.

Early European exploration

Much of the initial phase of European exploration of the North American Arctic was centred on a search for theNorthwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea lane between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, near the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Arctic Archipelago of Canada. The eastern route along the Arctic ...

and undertaken by Britain. The 1616 expedition of William Baffin were the first Europeans to record sighting the then-unnamed Ellesmere Island (Baffin named Jones and Smith Sounds on the island's south and southeast coasts). However, the onset of the Little Ice Age interrupted the progress of explorations for two centuries.

In 1818, an ice jam in Baffin Bay

Baffin Bay (Inuktitut: ''Saknirutiak Imanga''; ; ; ), located between Baffin Island and the west coast of Greenland, is defined by the International Hydrographic Organization as a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is sometimes considered a s ...

broke, allowing European vessels access to the High Arctic (whaler

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Jap ...

s had been active in Davis Strait

The Davis Strait (Danish language, Danish: ''Davisstrædet'') is a southern arm of the Arctic Ocean that lies north of the Labrador Sea. It lies between mid-western Greenland and Baffin Island in Nunavut, Canada. To the north is Baffin Bay. The ...

, about southeast of Ellesmere, since 1719). Baffin Bay was then navigable in the summers due to the presence of an ice dam in Smith Sound, which prevented Arctic drift ice from flowing south. The other channels of the archipelago remained congested with ice.

That year, John Ross led the first recorded European expedition to Cape York, at which time there were reportedly only 140 Inughuit

The Inughuit (singular: Inughuaq), Inuhuit, or Smith Sound Inuit, historically called Arctic Highlanders or Polar Eskimos, are an ethnic subgroup of the Greenlandic Inuit. They are the northernmost group of Inuit and the northernmost people in No ...

. (The Inughuit of North Greenland, the Kalaallit

Kalaallit are a Greenlandic Inuit ethnic group, being the largest group in Greenland, concentrated in the west. It is also a contemporary term in the Greenlandic language for the Indigenous of Greenland ().Hessel, 8 The Kalaallit (singular: ) a ...

of West Greenland, and Inuit

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwe ...

of the archipelago are descendants of the Thule culture, which had diverged during the isolation imposed by the Little Ice Age.) Knowledge of Ellesmere persisted in the oral histories of the Inuit of Baffin Island and the Inughuit of northern Greenland, who each called it .

Euro-American exploration and contact

The search for Franklin's lost expedition – also searching for the Northwest Passage and to establish claims to the Far North – involved more than forty expeditions to the High Arctic over two decades, and represented the peak period of Euro-American Arctic exploration. Edward Augustus Inglefield led an 1852 expedition which surveyed the coastlines of Baffin Bay and Smith Sound, being stopped by ice in Nares Strait. He named Ellesmere Island for the president of theRoyal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

(1849–1852), Francis Egerton, 1st Earl of Ellesmere. The Second Grinnell expedition (1853–1855) made slightly further progress before becoming trapped in the ice. Over two winters the expedition charted both sides of Kane Basin to about 80°N, from where Elisha Kent Kane claimed to have sighted the conjectured Open Polar Sea.

During this period, as the Little Ice Age abated and the hunting of marine mammals became more feasible again, Aboriginal peoples began to return to Ellesmere Island. The most well-known of these migrations in both Inuit and European accounts is the journey of Qitlaq, who led a group of Inuit families from Baffin Island to northwestern Greenland, via Ellesmere Island, in the 1850s. This journey reestablished contact between Inuit who had been separated for two centuries and reintroduced vital technologies to the Inughuit. Other groups followed and by the 1870s Inuit were living on Ellesmere Island and had regular contact with those on the neighbouring islands.

Contact between Inuit and Europeans or Americans was often indirect, as the Inuit happened upon shipwrecks or abandoned base camps which provided wood and metal resources. European goods were also obtained through inter-group trade. Long-term contact began in the 1800s through whaling stations and trading posts, which frequently relocated. Euro-American expeditions employed Inughuit, Inuit and west Greenlander guides, hunters and labourers, gradually blending their knowledge with European technology to conduct effective exploration.

British and United States Arctic expeditions had been interrupted for some years due to the priorities of the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

and the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, respectively. By about 1860, the focus of Arctic exploration had shifted to the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distingu ...

. As earlier attempts at the pole via Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), previously known as Spitsbergen or Spitzbergen, is a Norway, Norwegian archipelago that lies at the convergence of the Arctic Ocean with the Atlantic Ocean. North of continental Europe, mainland Europe, it lies about midway be ...

or eastern Greenland had reached impasses, numerous expeditions came to Ellesmere Island to pursue the route through Nares Straight.

The United States expedition led by Adolphus Greely in 1881 crossed the island from east to west, establishing Fort Conger in the northern part of the island. The Greely expedition found fossil forests on Ellesmere Island in the late 1880s. Stenkul Fiord was first explored in 1902 by Per Schei, a member of Otto Sverdrup's 2nd Norwegian Polar Expedition.

The Ellesmere Ice Shelf was documented by the British Arctic Expedition

The British Arctic Expedition of 1875–1876, led by Sir George Nares, was sent by the Admiralty (United Kingdom), British Admiralty to attempt to reach the North Pole via Smith Sound on the west coast of Greenland.

Although the expedition fail ...

of 1875–76, in which Lieutenant Pelham Aldrich's party went from Cape Sheridan () west to Cape Alert (), including the Ward Hunt Ice Shelf. In 1906 Robert Peary led an expedition in northern Ellesmere Island, from Cape Sheridan along the coast to the western side of Nansen Sound (93°W). During Peary's expedition, the ice shelf was continuous; it has since been estimated to have covered . The ice shelf broke apart in the 20th century, presumably due to climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

.

Establishment of Canadian sovereignty

In 1880, the British Arctic Territories were transferred to Canada. Canada did little to solidify its legal possession of the islands until prompted by foreign action in 1902–03: Otto Sverdrup claimed three islands west of Ellesmere for Norway, the Alaska boundary dispute was settled against Canada's interests, andRoald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegians, Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Am ...

set out to sail the Northwest Passage. To establish an official government presence in the Far North, the North-West Mounted Police

The North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) was a Canadian paramilitary police force, established in 1873, to maintain order in the new Canadian North-West Territories (NWT) following the 1870 transfer of Rupert's Land and North-Western Territory to ...

(NWMP) were sent on sovereignty patrols. A NWMP detachment sailed to the Arctic whaling stations in 1903, where they forbade whalers from killing muskox or trading skins, in order to prevent overhunting and protect the Inuit's ability to sustain themselves. In 1904 a NWMP detachment sailed to Cape Herschel at the east end of Sverdrup Pass, where they could intercept hunters accessing the interior of Ellesmere.

While the fur trade was brought under control, American exploration parties to the Far North had acted with autonomy and intensively hunted terrestrial mammals to sustain their expeditions. Peary's parties had heavily hunted muskoxen on Ellesmere and had nearly brought the extinction of caribou in northern Greenland; the Crocker Land Expedition (1913–1916) also extensively hunted muskoxen. In response to these and other trespasses, the government amended the ''Northwest Game Act'' to prohibit the killing of muskoxen except for Native inhabitants who otherwise faced starvation.

In 1920, the government learned that Inughuit

The Inughuit (singular: Inughuaq), Inuhuit, or Smith Sound Inuit, historically called Arctic Highlanders or Polar Eskimos, are an ethnic subgroup of the Greenlandic Inuit. They are the northernmost group of Inuit and the northernmost people in No ...

from Greenland had been annually visiting Ellesmere Island for polar bear and muskox hunting – in violation of Canadian law – and selling the skins at Knud Rasmussen

Knud Johan Victor Rasmussen (; 7 June 1879 – 21 December 1933) was a Greenlandic-Danish polar explorer and anthropologist. He has been called the "father of Eskimology" (now often known as Inuit Studies or Greenlandic and Arctic Studies) ...

's trading post at North Star Bay (known as Thule). The Danish government stated that North Greenland was a "no man's land" outside their administration and Rasmussen, as the ''de facto'' sole authority, refused to stop the trade, which the Inughuit needed to support themselves. In response, Royal Canadian Mounted Police

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP; , GRC) is the Law enforcement in Canada, national police service of Canada. The RCMP is an agency of the Government of Canada; it also provides police services under contract to 11 Provinces and terri ...

(RCMP) detachments were established on Ellesmere Island at Craig Harbour in 1922 and at Bache Post in 1926, positioned to guard the coastal and overland routes to the hunting grounds on the western side of Ellesmere. In addition to intercepting illegal hunting and fur-trading, the RCMP conducted patrols and encouraged the Inuit to maintain their traditional lifestyle. The posts were closed in the mid-1930s, after the sovereignty issues had been settled.

Geography

Ellesmere Island is the northernmost island of the

Ellesmere Island is the northernmost island of the Arctic Archipelago

The Arctic Archipelago, also known as the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, is an archipelago lying to the north of the Canadian continental mainland, excluding Greenland (an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, which is, by itself, much larger ...

in Canada's Far North and one of the world's northernmost land masses. It is exceeded in this regard only by neighbouring Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

, which extends about closer to the north pole. Ellesmere's northernmost point, Cape Columbia

Cape Columbia is the northernmost point of land of Canada, located on Ellesmere Island in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut. It marks the westernmost coastal point of Lincoln Sea in the Arctic Ocean. It is the world's northernmost point of l ...

(at ), is less than from the north pole, while its southern coasts at 77°N are well within the Arctic Circle.

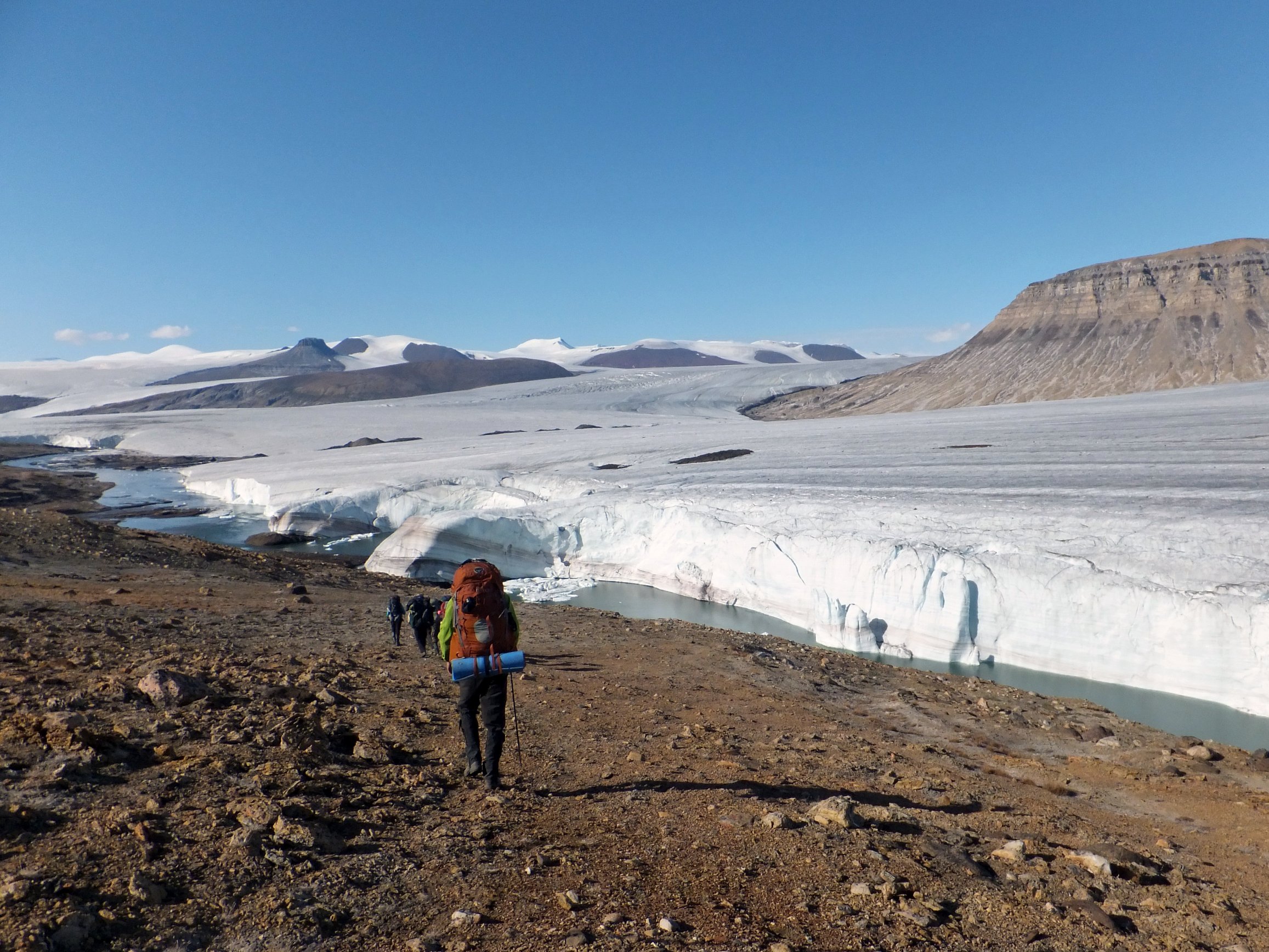

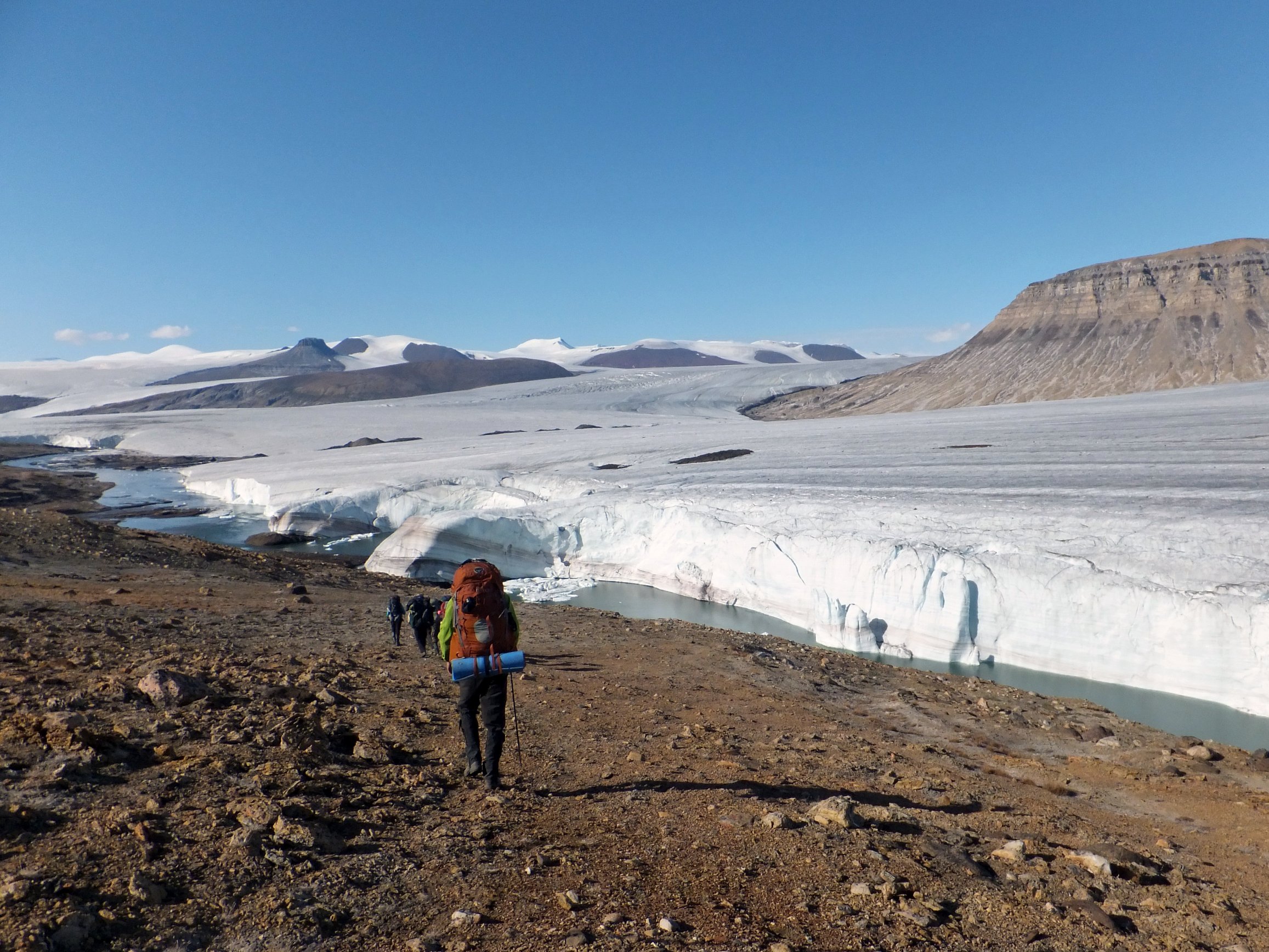

Ellesmere has the highest and longest mountain ranges in eastern North America and is the most mountainous island in the Arctic Archipelago. It has over half of the archipelago's ice cover, with ice caps and glaciers across 40% of its surface. Its extensive coastline includes some of the world's longest fiords.

To the west, Ellesmere is separated from Axel Heiberg Island by Nansen and Eureka Sounds, the latter of which narrows to . Devon Island

Devon Island (, ) is an island in Canada and the largest desert island, uninhabited island (no permanent residents) in the world. It is located in Baffin Bay, Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada. It is one of the largest members of the Arctic Ar ...

is to the south across Jones Sound; at the west end of the sound, they are separated by North Kent Island and two channels which narrow to . Greenland is to the east across Nares Strait

Nares Strait (; ) is a waterway between Ellesmere Island and Greenland that connects the northern part of Baffin Bay in the Atlantic Ocean with the Lincoln Sea in the Arctic Ocean. From south to north, the strait includes Smith Sound, Kane Basi ...

; the strait narrows to at Cape Isabella on Smith Sound

Smith Sound (; ) is an Arctic sea passage between Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are ...

and further north narrows to at Robeson Channel. These channels and straits typically freeze over in winter, though winds and currents leave pockets of open water (temporary leads

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

and persistent polynya

A polynya () is an area of open water surrounded by sea ice. It is now used as a geographical term for an area of unfrozen seawater within otherwise contiguous pack ice or fast ice. It is a loanword from the Russian language, Russian (), whic ...

s) in Nares Strait. To the north of Ellesmere is the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five oceanic divisions. It spans an area of approximately and is the coldest of the world's oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, ...

, with Lincoln Sea to the northeast.

Protected areas

More than one-fifth of the island is protected asQuttinirpaaq National Park

Quttinirpaaq National Park is located on the northeastern corner of Ellesmere Island in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada. It is the second most northerly park on Earth after Northeast Greenland National Park. In Inuktitut, Quttinirpaaq m ...

(formerly Ellesmere Island National Park Reserve), which includes seven fjord

In physical geography, a fjord (also spelled fiord in New Zealand English; ) is a long, narrow sea inlet with steep sides or cliffs, created by a glacier. Fjords exist on the coasts of Antarctica, the Arctic, and surrounding landmasses of the n ...

s and a variety of glacier

A glacier (; or ) is a persistent body of dense ice, a form of rock, that is constantly moving downhill under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires ...

s, as well as Lake Hazen, North America's largest lake north of the Arctic Circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the two polar circles, and the northernmost of the five major circle of latitude, circles of latitude as shown on maps of Earth at about 66° 34' N. Its southern counterpart is the Antarctic Circle.

The Arctic Circl ...

. Barbeau Peak, the highest mountain in Nunavut () is located in the British Empire Range on Ellesmere Island. The most northern mountain range

A mountain range or hill range is a series of mountains or hills arranged in a line and connected by high ground. A mountain system or mountain belt is a group of mountain ranges with similarity in form, structure, and alignment that have aris ...

in the world, the Challenger Mountains, is located in the northeast region of the island. The northern lobe of the island is called Grant Land.

The Arctic willow is the only woody species to grow on Ellesmere Island.

In July 2007, a study noted the disappearance of habitat for

The Arctic willow is the only woody species to grow on Ellesmere Island.

In July 2007, a study noted the disappearance of habitat for waterfowl

Anseriformes is an order of birds also known as waterfowl that comprises about 180 living species of birds in three families: Anhimidae (three species of screamers), Anseranatidae (the magpie goose), and Anatidae, the largest family, which i ...

, invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s, and algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

on Ellesmere Island. According to John Smol of Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario

Kingston is a city in Ontario, Canada, on the northeastern end of Lake Ontario. It is at the beginning of the St. Lawrence River and at the mouth of the Cataraqui River, the south end of the Rideau Canal. Kingston is near the Thousand Islands, ...

, and Marianne S. V. Douglas of the University of Alberta

The University of Alberta (also known as U of A or UAlberta, ) is a public research university located in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. It was founded in 1908 by Alexander Cameron Rutherford, the first premier of Alberta, and Henry Marshall Tory, t ...

in Edmonton

Edmonton is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Alberta. It is situated on the North Saskatchewan River and is the centre of the Edmonton Metropolitan Region, which is surrounded by Central Alberta ...

, warming conditions and evaporation have caused low water levels and changes in the chemistry of ponds and wetlands in the area. The researchers noted that "In the 1980s they often needed to wear hip waders to make their way to the ponds...while by 2006 the same areas were dry enough to burn."

Climate

Ellesmere Island has atundra climate

The tundra climate is a polar climate sub-type located in high latitudes and high mountains. It is classified as ET according to the Köppen climate classification. It is a climate which at least one month has an average temperature high enough ...

(Köppen Köppen is a German surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Bernd Köppen (1951–2014), German pianist and composer

* Carl Köppen (1833-1907), German military advisor in Meiji era Japan

* Edlef Köppen (1893–1939), German author ...

''ET'') and an ice cap climate

An ice cap climate is a polar climate where no mean monthly temperature exceeds . The climate generally covers areas at high altitudes and Polar regions of Earth, polar regions (60–90° north and south latitude), such as Antarctica and some of ...

(Köppen Köppen is a German surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Bernd Köppen (1951–2014), German pianist and composer

* Carl Köppen (1833-1907), German military advisor in Meiji era Japan

* Edlef Köppen (1893–1939), German author ...

''EF'') with the temperature being cold year-round. Two semi-permanent air systems dominate the weather: the high-pressure northern polar vortex and a low-pressure area which forms in different sites between Baffin Bay and the Labrador Sea. Prevailing winds on Ellesmere are northwesterly, cold, and of low humidity due to ice cover over the Arctic Ocean. Seasonal shifts on Ellesmere are sudden and striking: winters are long and harsh, summers short and relatively abundant, with spring and autumn being brief intervals of transition.

Fog regularly occurs near open water in September. While the major air systems strengthen towards their annual peak in winter, the Arctic and Atlantic air masses collide in autumn to produce severe storms at Ellesmere. The storm season peaks in October and persists until the sea freezes. The polar vortex strengthens during the polar night and gives rise to easterly winds which are major hazards for populations, especially given the very low temperatures. January winds have been recorded at with gusts to at Fort Conger and at Lake Hazen. Very cold temperatures continue until April and no month passes without experiencing freezing temperatures.

Snowfall begins in late August and does not melt until the June thaw. The seasonal shift in daylight is also extreme. The polar night lasts from four-and-a-half months in the north to about three months in the south.

Regional variation

Ellesmere's Arctic marine climate is strongly affected in the north by Arctic Ocean currents and the polar vortex, while the climate of the southeastern coast is influenced by the warm Atlantic water of the West Greenland Current. Interior regions shielded by the island's high mountain ranges experience distinctive quasi-continental microclimates. The highest precipitation is on the northern coast, averaging . On the south side of the Grant Land mountains, only reaches the Hazen Plateau. The average number of snow-free days varies from 45 days on the north coast to 77 days in the Eureka–Tanquary corridor. Winters are considerably colder in the interior. At Lake Hazen, Peary's expedition recorded daytime temperatures of in February 1900, and a Defence Research Board party recorded temperatures as low as in the winter of 1957–58. Nonetheless, there are archaeological remains of winter dwellings of both Independence and Thule cultures in the interior.Climate change

A paleolimnological study of algae in the sediments of shallow ponds on Cape Herschel (which faces Smith Sound on Ellesmere's eastern coast) found that the ponds had been permanent and relatively stable for several millennia until experiencing ecological changes associated with warming, beginning around 1850 and accelerating in the early 2000s. During the 23-year study period, an ecological threshold was crossed as several of the study ponds had completely desiccated while others had very reduced water levels. In addition, the wetlands surrounding the ponds were severely affected and dried vegetation could be easily burned.Glaciers, ice caps and ice shelves

Large portions of Ellesmere Island are covered with glaciers and ice, with Manson Icefield () and Sydkap () in the south; Prince of Wales Icefield () and Agassiz Ice Cap () along the central-east side of the island, and the Northern Ellesmere icefields ().

The northwest coast of Ellesmere Island was covered by a massive, long ice shelf until the 20th century. The Ellesmere Ice Shelf shrank by 90 per cent in the 20th century due to warming trends in the Arctic, particularly in the 1930s and 1940s, a period when the largest ice islands (the T1 and the T2 ice islands) were formed leaving the separate Alfred Ernest, Ayles, Milne, Ward Hunt, and Markham Ice Shelves. The Ward Hunt Ice Shelf, the largest remaining section of thick (>10 m, >30 ft) landfast sea ice along the northern coastline of Ellesmere Island, lost almost of ice in a massive calving in 1961–1962. Five large ice islands which resulted account for 79% of the calved material. It further decreased by 27% in thickness () between 1967 and 1999. A 1986 survey of Canadian ice shelves found that or of ice calved from the Milne and Ayles ice shelves between 1959 and 1974.

The breakup of the Ellesmere Ice Shelves has continued in the 21st century: the Ward Ice Shelf experienced a major breakup during the summer of 2002; the Ayles Ice Shelf calved entirely on 13 August 2005; the largest breakoff of the ice shelf in 25 years, it may pose a threat to the oil industry in the

Large portions of Ellesmere Island are covered with glaciers and ice, with Manson Icefield () and Sydkap () in the south; Prince of Wales Icefield () and Agassiz Ice Cap () along the central-east side of the island, and the Northern Ellesmere icefields ().

The northwest coast of Ellesmere Island was covered by a massive, long ice shelf until the 20th century. The Ellesmere Ice Shelf shrank by 90 per cent in the 20th century due to warming trends in the Arctic, particularly in the 1930s and 1940s, a period when the largest ice islands (the T1 and the T2 ice islands) were formed leaving the separate Alfred Ernest, Ayles, Milne, Ward Hunt, and Markham Ice Shelves. The Ward Hunt Ice Shelf, the largest remaining section of thick (>10 m, >30 ft) landfast sea ice along the northern coastline of Ellesmere Island, lost almost of ice in a massive calving in 1961–1962. Five large ice islands which resulted account for 79% of the calved material. It further decreased by 27% in thickness () between 1967 and 1999. A 1986 survey of Canadian ice shelves found that or of ice calved from the Milne and Ayles ice shelves between 1959 and 1974.

The breakup of the Ellesmere Ice Shelves has continued in the 21st century: the Ward Ice Shelf experienced a major breakup during the summer of 2002; the Ayles Ice Shelf calved entirely on 13 August 2005; the largest breakoff of the ice shelf in 25 years, it may pose a threat to the oil industry in the Beaufort Sea

The Beaufort Sea ( ; ) is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean, located north of the Northwest Territories, Yukon, and Alaska, and west of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The sea is named after Sir Francis Beaufort, a Hydrography, hydrographer. T ...

. The piece is . In April 2008, it was discovered that the Ward Hunt shelf was fractured, with dozens of deep, multi-faceted cracks and in September 2008 the Markham shelf () completely broke off to become floating sea ice

Sea ice arises as seawater freezes. Because ice is less density, dense than water, it floats on the ocean's surface (as does fresh water ice). Sea ice covers about 7% of the Earth's surface and about 12% of the world's oceans. Much of the world' ...

.

A 2018 study measured a 5.9% reduction in area amongst 1,773 glaciers in Northern Ellesmere island in the 16-year period 1999–2015 based on satellite data. In the same period, 19 out of 27 ice tongues disintegrated to their grounding lines and ice shelves suffered a 42% loss in surface area.

Paleontology

Paleocene

The Paleocene ( ), or Palaeocene, is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 66 to 56 mya (unit), million years ago (mya). It is the first epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), ...

-Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

(ca. 55 Ma) fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

forest in the Stenkul Fiord sediments. The Stenkul Fiord site represents a series of deltaic swamp and floodplain

A floodplain or flood plain or bottomlands is an area of land adjacent to a river. Floodplains stretch from the banks of a river channel to the base of the enclosing valley, and experience flooding during periods of high Discharge (hydrolog ...

forests. The trees stood for at least 400 years. Individual stumps and stems of >1 m (>3 ft) diameter were abundant, and are identified as '' Metasequoia'' and possibly '' Glyptostrobus''. Well preserved Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch (geology), epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.33 to 2.58peat

Peat is an accumulation of partially Decomposition, decayed vegetation or organic matter. It is unique to natural areas called peatlands, bogs, mires, Moorland, moors, or muskegs. ''Sphagnum'' moss, also called peat moss, is one of the most ...

s containing abundant vertebrate and plant macrofossils characteristic of a boreal forest

Taiga or tayga ( ; , ), also known as boreal forest or snow forest, is a biome characterized by pinophyta, coniferous forests consisting mostly of pines, spruces, and larches. The taiga, or boreal forest, is the world's largest land biome. I ...

have been reported from Strathcona Fiord.

In 2006, University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, or UChi) is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Its main campus is in the Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, Chic ...

paleontologist

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geolo ...

Neil Shubin and Academy of Natural Sciences paleontologist Ted Daeschler reported the discovery of the fossil of a Paleozoic

The Paleozoic ( , , ; or Palaeozoic) Era is the first of three Era (geology), geological eras of the Phanerozoic Eon. Beginning 538.8 million years ago (Ma), it succeeds the Neoproterozoic (the last era of the Proterozoic Eon) and ends 251.9 Ma a ...

(ca. 375 Ma) fish, named '' Tiktaalik roseae'', in the former stream bed

A streambed or stream bed is the bottom of a stream or river and is confined within a Stream channel, channel or the Bank (geography), banks of the waterway. Usually, the bed does not contain terrestrial (land) vegetation and instead supports d ...

s of Ellesmere Island. The fossil exhibits many characteristics of fish, but also indicates a transitional creature that may be a predecessor of amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

s, reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

s, birds, and mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s, including humans.

In 2011, Jason P. Downs and co-authors described the sarcopterygian

Sarcopterygii (; )—sometimes considered synonymous with Crossopterygii ()—is a clade (traditionally a class or subclass) of vertebrate animals which includes a group of bony fish commonly referred to as lobe-finned fish. These vertebrates ar ...

'' Laccognathus embryi'' from specimens collected from the same locality that ''Tiktaalik'' was found.

Ecology

The ecosystems of the High Arctic are considered to be young and underdeveloped, having only emerged since the glacial retreat of 8,000 to 6,000 BCE. There is a lack of species diversity, with a small number of animal species and short food chains. These species have adapted to take advantage of the productive summer while surviving through winter scarcity. Zooplankton, for example, grow to a larger body size and produce larger eggs in greater numbers than in other regions. Aside from the polar desert conditions of much of the island, there are remarkably productive ecological zones in the arctic oasis of the Lake Hazen area and the polynyas of the island's coastal waters.Insect ecology

Ellesmere Island is noted as being the northernmost occurrence ofeusocial

Eusociality ( Greek 'good' and social) is the highest level of organization of sociality. It is defined by the following characteristics: cooperative brood care (including care of offspring from other individuals), overlapping generations wit ...

insects; specifically, the bumblebee

A bumblebee (or bumble bee, bumble-bee, or humble-bee) is any of over 250 species in the genus ''Bombus'', part of Apidae, one of the bee families. This genus is the only Extant taxon, extant group in the tribe Bombini, though a few extinct r ...

'' Bombus polaris''. There is a second species of bumblebee occurring there, '' Bombus hyperboreus'', which is a parasite in the nests of ''B. polaris''.

While non-eusocial, the Arctic woolly bear moth ('' Gynaephora groenlandica'') can also be found at Ellesmere Island. While this species generally has a 10-year life cycle, its life is known to extend to up to 14 years at both the Alexandra Fiord lowland and Ellesmere Island.

Earth's magnetism

In 2015, the Earth's geomagnetic north pole was located at approximately , on Ellesmere Island. It is forecast to remain on Ellesmere Island in 2020, shifting to .Population

All groups occupying the island settled on the coast, particularly those relying on maritime resources, while modern-era government-funded settlements were initially supplied by sea.

In 2021, the population of Ellesmere Island was recorded as 144. There are three settlements on Ellesmere Island: Alert (permanent pop. 0, but home to a small temporary population), Eureka (permanent pop. 0), and Grise Fiord (pop. 144). Politically, it is part of the

All groups occupying the island settled on the coast, particularly those relying on maritime resources, while modern-era government-funded settlements were initially supplied by sea.

In 2021, the population of Ellesmere Island was recorded as 144. There are three settlements on Ellesmere Island: Alert (permanent pop. 0, but home to a small temporary population), Eureka (permanent pop. 0), and Grise Fiord (pop. 144). Politically, it is part of the Qikiqtaaluk Region

The Qikiqtaaluk Region, Qikiqtani Region (Inuktitut syllabics: ᕿᑭᖅᑖᓗᒃ ) or the Baffin Region is the easternmost, northernmost, and southernmost administrative region of Nunavut, Canada. Qikiqtaaluk is the traditional Inuktitut nam ...

. Part of the year there are also Parks Canada

Parks Canada ()Parks Canada is the applied title under the Federal Identity Program; the legal title is Parks Canada Agency (). is the agency of the Government of Canada which manages the country's 37 National Parks, three National Marine Co ...

staff stationed at Camp Hazen

Hazen Camp is a shelter maintained and operated by Parks Canada. It contains many all-weather shelters for the park staff. The visiting researchers set up tents in the camp area.

History

Hazen Camp was originally established in 19571958 for Opera ...

and Tanquary Fiord Airport.

Alert

Canadian Forces Station (CFS) Alert is the northernmost continuously inhabited settlement in the world. With the end of theCold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

and the advent of new technologies allowing for remote interpretation of data, the overwintering population has been reduced to 62 civilians and military personnel as of 2016.

Eureka

Eureka (the third northernmost settlement in the world) consists of three areas:Eureka Aerodrome

Eureka Aerodrome is located at Eureka, Nunavut

Nunavut is the largest and northernmost Provinces and territories of Canada#Territories, territory of Canada. It was separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999, via ...

, which includes Fort Eureka (the quarters for military personnel maintaining the island's communications equipment); the Environment Canada

Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC; )Environment and Climate Change Canada is the applied title under the Federal Identity Program; the legal title is Department of the Environment (). is the Ministry (government department), department ...

Weather Station; and the Polar Environment Atmospheric Research Laboratory (PEARL), formerly the Arctic Stratospheric Ozone (AStrO) Observatory. Eureka has the lowest average annual temperature and least precipitation of any weather station in Canada.

Grise Fiord

Grise Fiord (

Grise Fiord (Inuktitut

Inuktitut ( ; , Inuktitut syllabics, syllabics ), also known as Eastern Canadian Inuktitut, is one of the principal Inuit languages of Canada. It is spoken in all areas north of the North American tree line, including parts of the provinces of ...

: , Romanized

In linguistics, romanization is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, and transcription, ...

: , lit. "place that never thaws") is an Inuit

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwe ...

hamlet that, despite a population of only 144, is the largest community on Ellesmere Island.

Located at the southern tip of Ellesmere Island, Grise Fiord lies north of the Arctic Circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the two polar circles, and the northernmost of the five major circle of latitude, circles of latitude as shown on maps of Earth at about 66° 34' N. Its southern counterpart is the Antarctic Circle.

The Arctic Circl ...

. Grise Fiord is the northernmost civilian settlement in Canada. It is also one of the coldest inhabited places in the world, with an average yearly temperature of .

Grise Fiord is cradled by the Arctic Cordillera mountain range.

Transportation

Transportation along coastal waters has been historically important for hunting and trade, whether on the sea ice or in small boats. The ice foot, a belt of level and secure ice around the shoreline between the high and low water marks, can be used from mid-September to July. In contrast, the pack ice does not stabilize and freeze fast until February, and presents a much rougher surface for travel. The navigation season for seagoing vessels is from late July to September, but is often considered treacherous due to currents, persistent shore ice, sea ice, and massive icebergs calved off of the many glaciers. September also marks a change in the weather with regular fog and the beginning of the autumn storm season.In popular culture

Ellesmere Island is the setting of much of Melanie McGrath's ''The Long Exile: A True Story of Deception and Survival Amongst the Inuit of the Canadian Arctic'' about the High Arctic relocation, and also of her Edie Kiglatuk mystery series. In the2013

2013 was the first year since 1987 to contain four unique digits (a span of 26 years).

2013 was designated as:

*International Year of Water Cooperation

*International Year of Quinoa

Events

January

* January 5 – 2013 Craig, Alask ...

American superhero film

Superhero film/movie is a film genre categorized by the presence of superhero characters, individuals with extraordinary abilities who are dedicated to fighting crime, saving the world, or helping the innocent. It is sometimes considered a sub ...

'' Man of Steel'', Ellesmere Island is the site of a combined United States-Canadian scientific expedition to recover an ancient Kryptonian spaceship buried in the glacial ice pack.

The island is the location for the 2014 BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

programme ''Snow Wolf Family and Me''.

The 2008 documentary ''Exile'' by Zacharias Kunuk documents the experiences of Inuit families who were forcibly relocated to Ellesmere island in the 1950s to settle it for the Canadian government. The families discuss being deceived by the government about the conditions and terms of where they were going and having to endure years of surviving in inhospitable conditions with little food or water.

In 2022, the US National Museum of Wildlife Art debuted the travelling exhibit ''Wolves: Photography by Ronan Donovan.'' The exhibit was developed in collaboration with the National Geographic Society

The National Geographic Society, headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, is one of the largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations in the world.

Founded in 1888, its interests include geography, archaeology, natural sc ...

and features images and videos of the Arctic wolves living on Ellesmere Island.

See also

* Lomonosov Ridge * Ledoyom * Serson Ice Shelf * Borup Fiord PassNotes

References

Further reading

* * * *External links

Ellesmere Island in the Atlas of Canada - Toporama; Natural Resources Canada

Mountains on Ellesmere Island

Detailed map, northern Ellesmere Island, including named capes, points, bays, and offshore islands

by Geoffrey Hattersley-Smith

Norman E. Brice Report on Ellesmere Island

at Dartmouth College Library {{Authority control Islands of Baffin Bay Islands of the Queen Elizabeth Islands Inhabited islands of Qikiqtaaluk Region